Submitted:

31 May 2025

Posted:

02 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

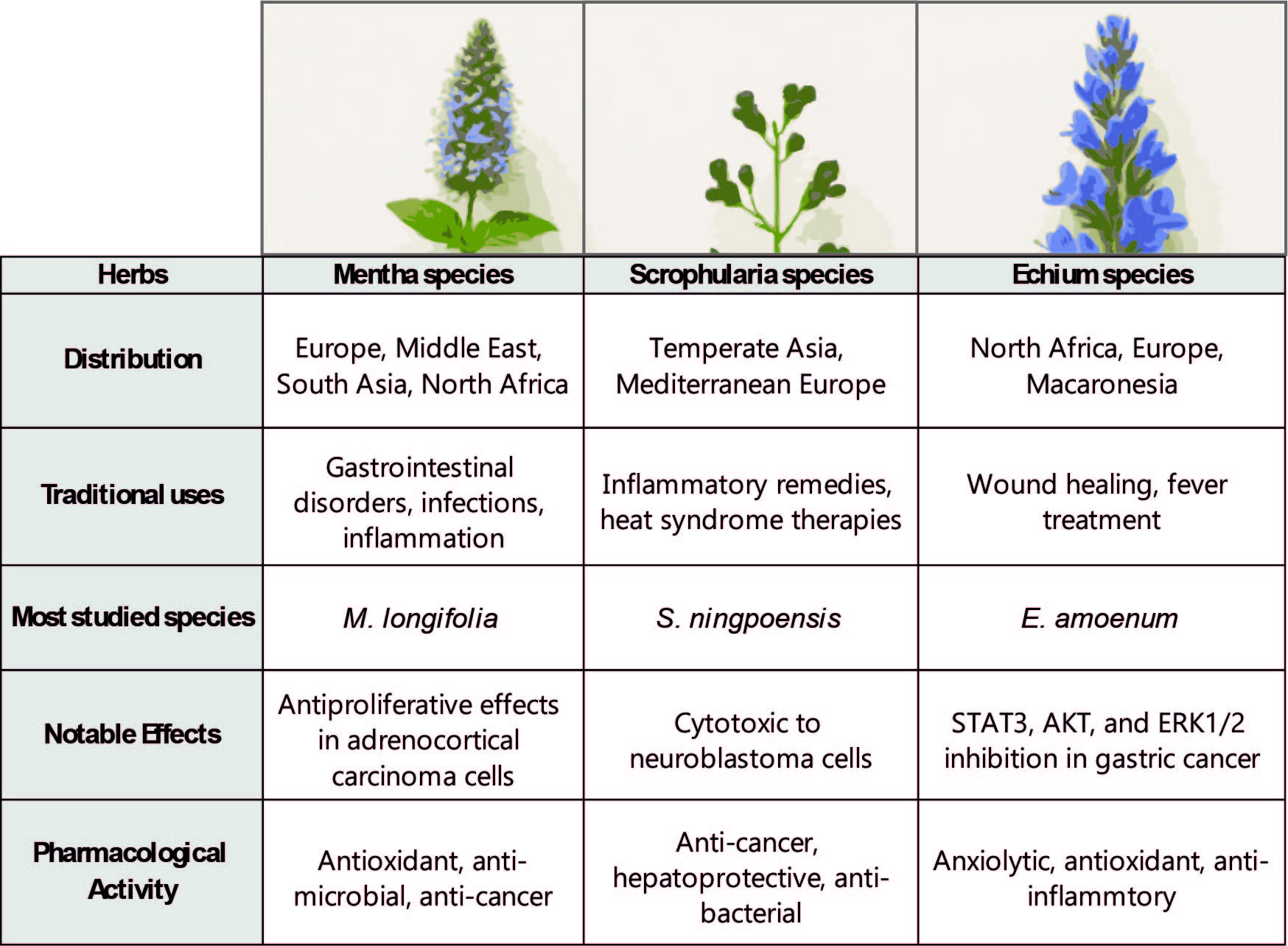

1. Scrophularia Orientalis

General Overview

Medicinal Properties and Uses

2. Echium Biebersteinii

General Overview

Medicinal Properties and Uses

3. Mentha Longifolia

General Overview

Medicinal Properties and Uses

Materials and Methods

Strains and Alleles

Herb Extraction

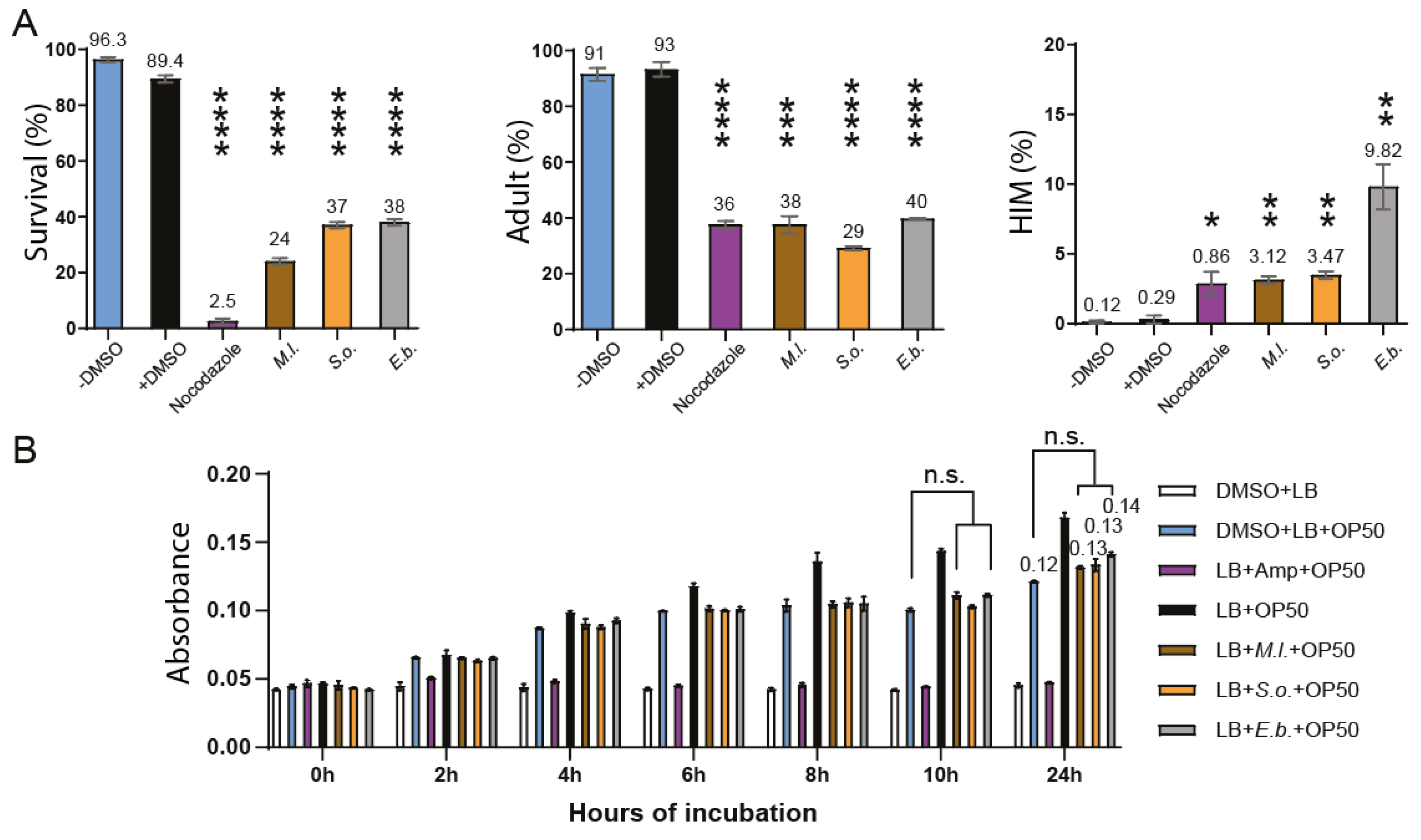

Survival, Larval Arrest/Lethality, and High Incidence of Males (HIM) Assay

LC–MS/MS Analysis

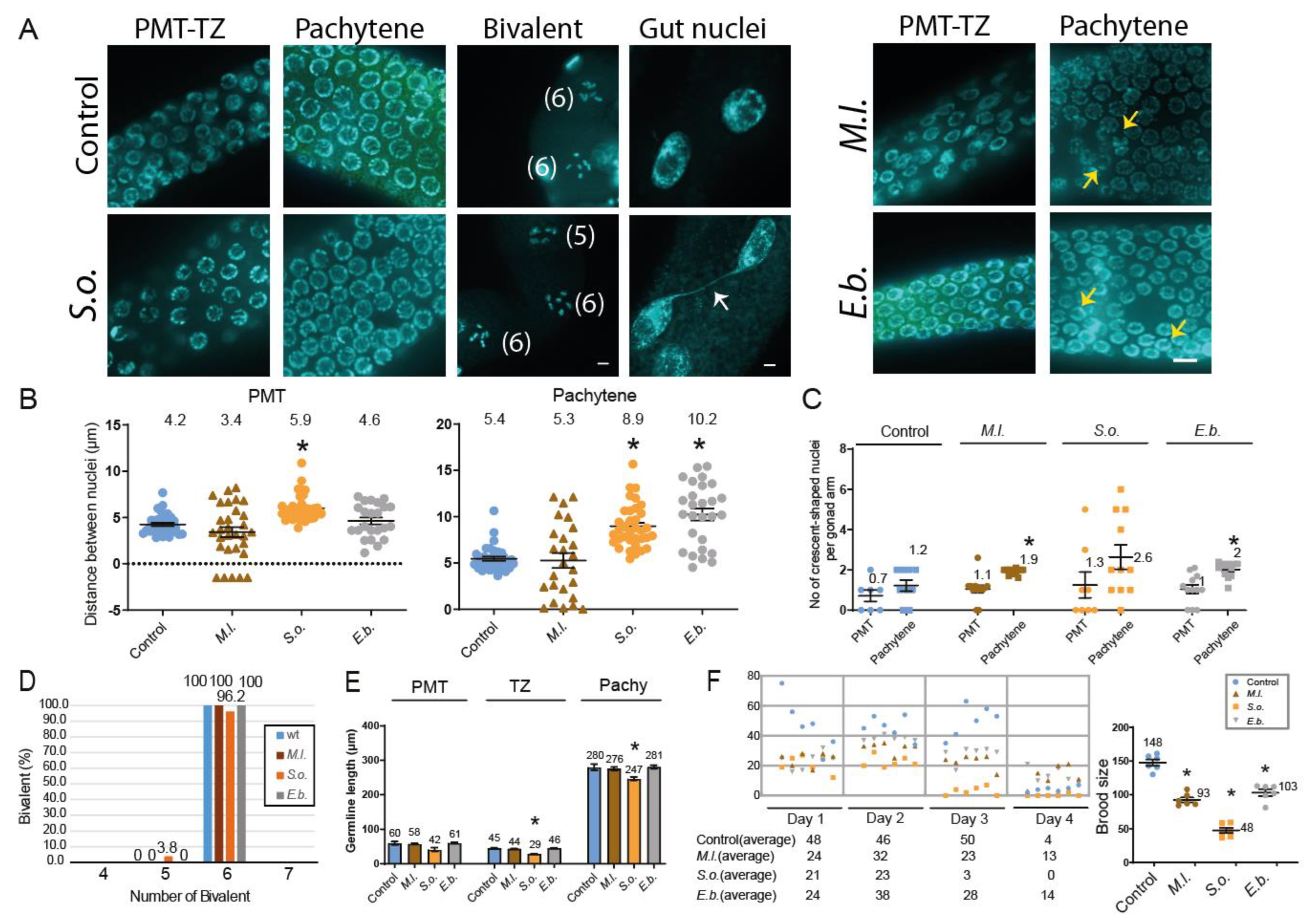

Immunofluorescence Assay

pCHK-1 Foci Quantification

Assessment of Germline Apoptosis

qRT-PCR

Results

Discussion

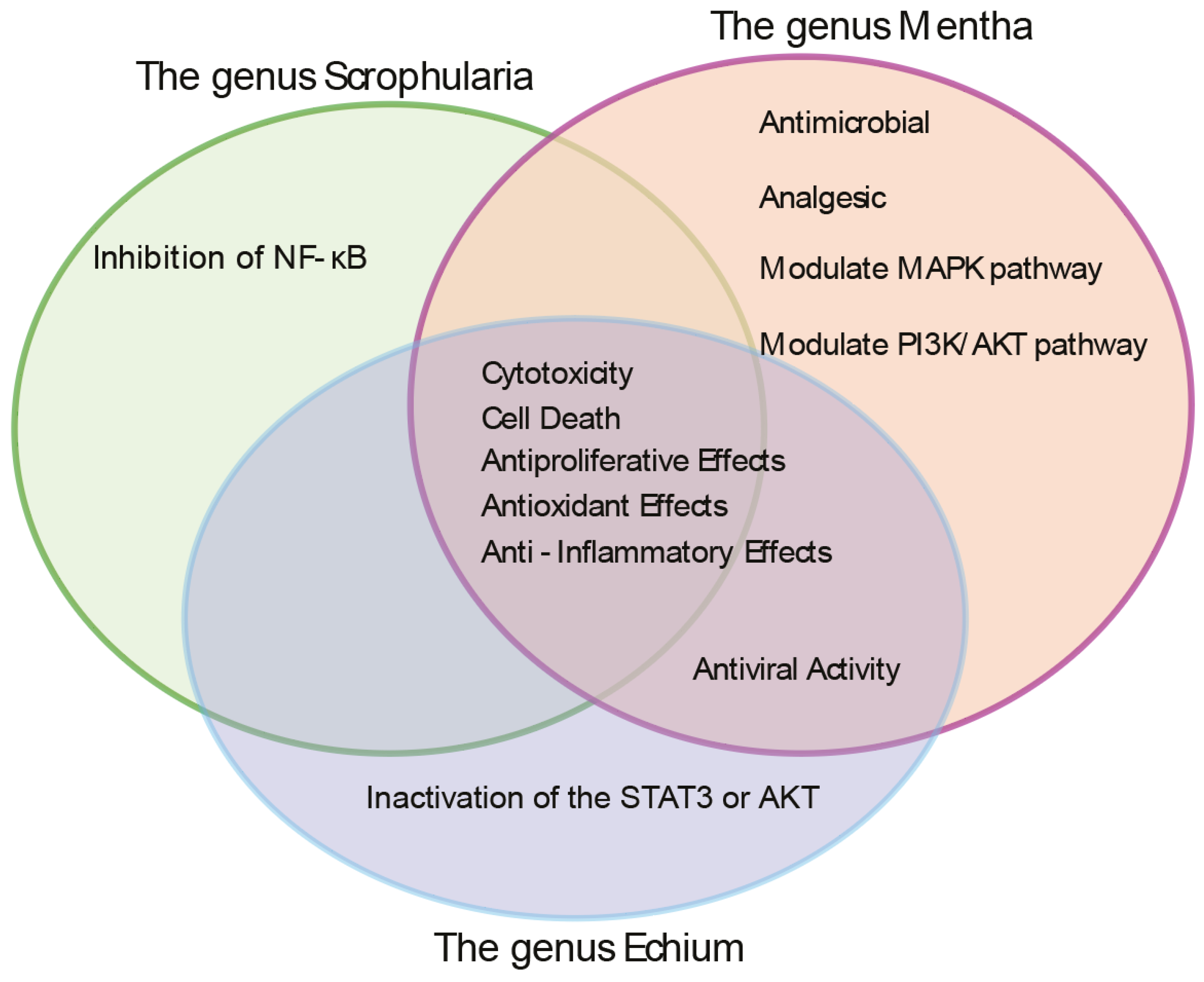

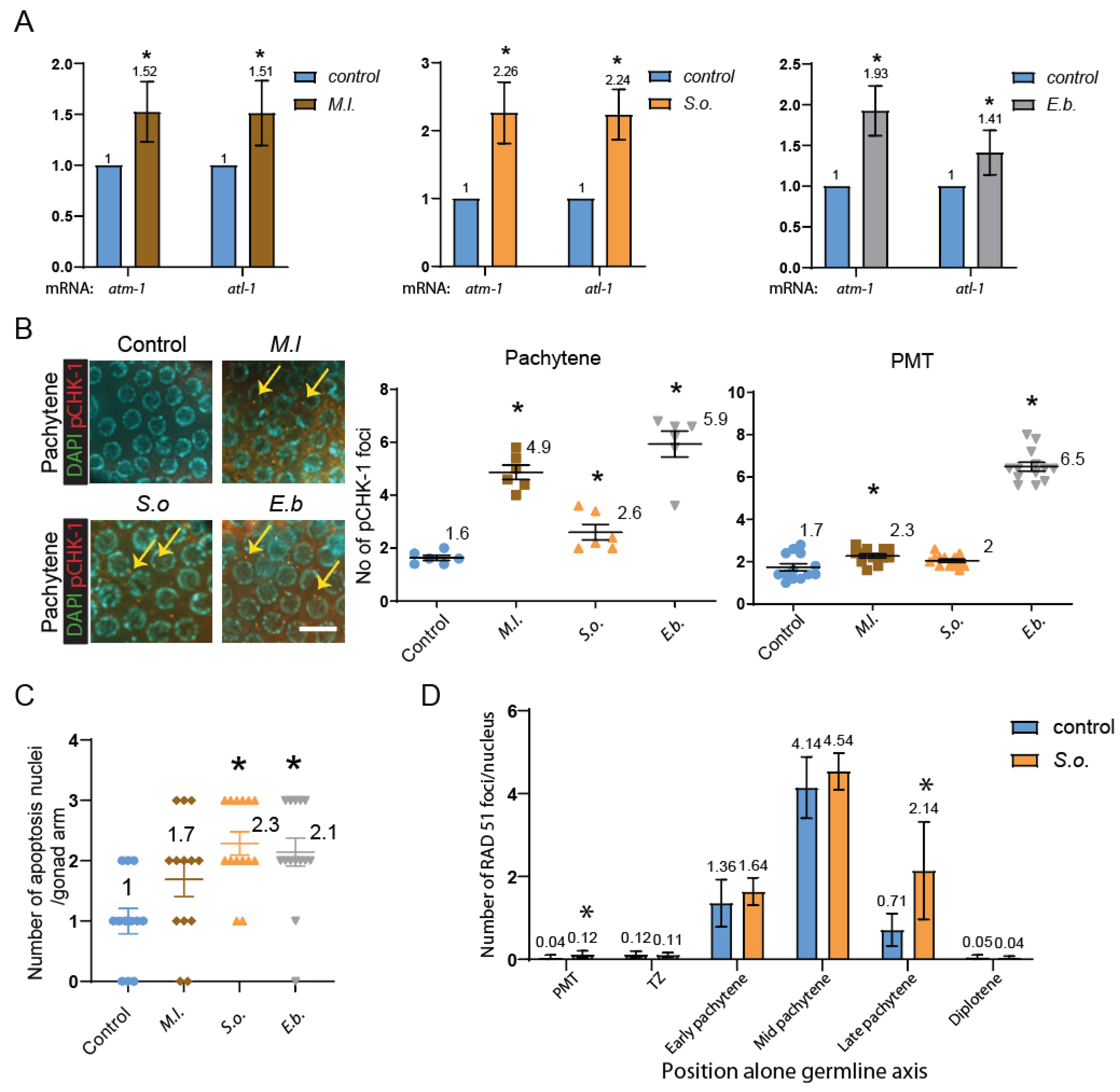

Herbal Extracts Induce Germline-Specific DNA Damage Checkpoint Activation and Meiotic Defects in C. elegans

Herbal Extracts Lead to Defective Mitotic and Meiotic Progression, Impaired DNA Repair, and DNA Damage Checkpoint Activation, Resulting in Germline Apoptosis

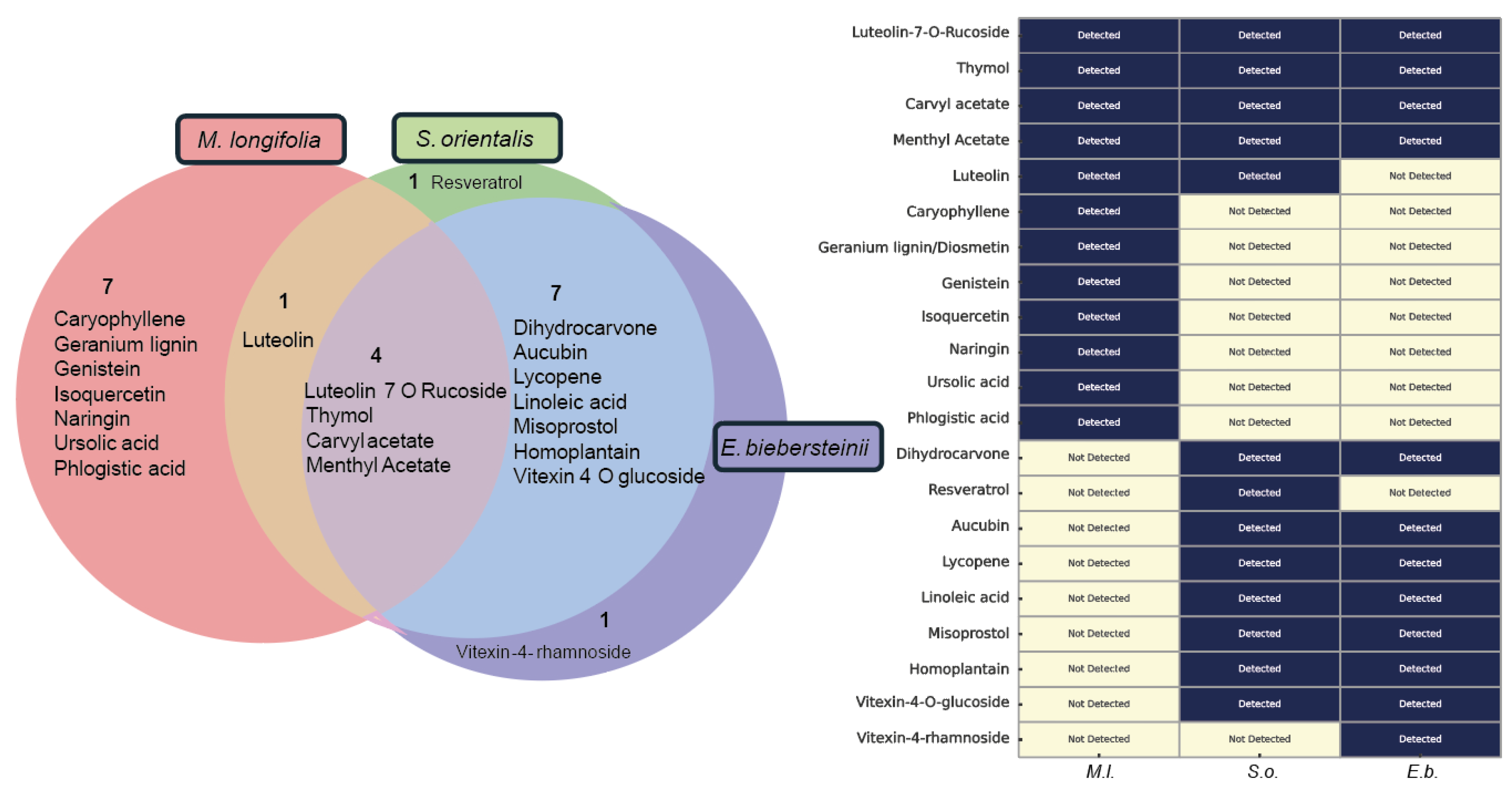

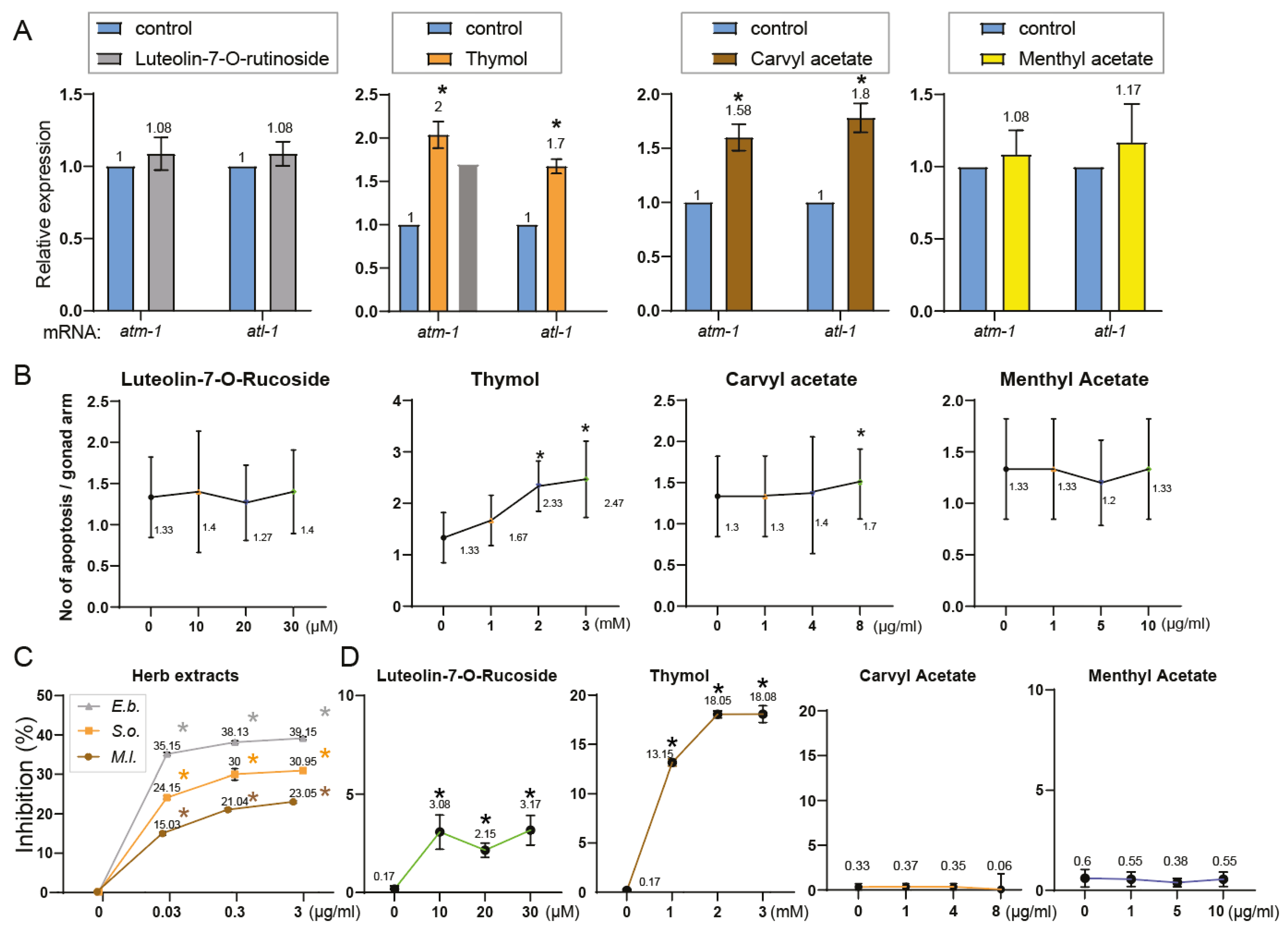

Phytochemical Composition Underlies the Biological Activities of Herbal Extracts: Four Common Compounds Identified—Thymol, Carvyl Acetate, Luteolin-7-O-Rutinoside, and Menthyl Acetate.

Phytochemical Overlap Explains Parallel DNA Damage Responses Induced by S. orientalis and E. biebersteinii Extracts

Uncoupling Antioxidant Activity from Germline Toxicity in Herbal Extracts

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ren, D.; et al. Pharmacology, phytochemistry, and traditional uses of Scrophularia ningpoensis Hemsl. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2021, 269, 113688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Santos Galíndez, J.; Díaz Lanza, A.M.a.; Fernández Matellano, L. Biologically Active Substances from the Genus Scrophularia. Pharmaceutical Biology 2002, 40, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheunert, A.; Heubl, G. Against all odds: reconstructing the evolutionary history of Scrophularia (Scrophulariaceae) despite high levels of incongruence and reticulate evolution. Organisms Diversity & Evolution 2017, 17, 323–349. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dalahmeh, Y.; et al. Scrophularia peyronii Post. from Jordan: Chemical Composition of Essential Oil and Phytochemical Profiling of Crude Extracts and Their In Vitro Antioxidant Activity. Life 2023, 13, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasdaran, A.; Hamedi, A. The genus Scrophularia: a source of iridoids and terpenoids with a diverse biological activity. Pharmaceutical Biology 2017, 55, 2211–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, I.; et al. Scrophularia orientalis extract induces calcium signaling and apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells. International Journal of Oncology 2016, 48, 1608–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardeshiry lajimi, A.; et al. Study of Anti Cancer Property of Scrophularia striata Extract on the Human Astrocytoma Cell Line (1321). Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research : IJPR 2010, 9, 403–410. [Google Scholar]

- Giessrigl, B.; et al. Effects of Scrophularia extracts on tumor cell proliferation, death and intravasation through lymphoendothelial cell barriers. International Journal of Oncology 2012, 40, 2063–2074. [Google Scholar]

- Baltisberger, M.; Widmer, A. Chromosome numbers of plant species from the Canary Islands. Botanica Helvetica 2006, 116, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; et al. Antioxidant Properties and Reported Ethnomedicinal Use of the Genus Echium (Boraginaceae). Antioxidants 2020, 9, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefi, S.; et al. Phytochemical investigation and biological activities of Echium arenarium (Guss) extracts. Microbial Pathogenesis 2018, 118, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retief, E.; Van Wyk, A.E. The genus Echium (Boraginaceae) in southern Africa. Bothalia 1998, 28, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, N.; Abolhassani, M. Immunomodulatory properties of borage (Echium amoenum) on BALB/c mice infected with Leishmania major. Journal of clinical immunology 2011, 31, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekhradnia, S.; Ebrahimzadeh, M.A. Antioxidant activity of Echium amoenum. Rev Chim J 2016, 67, 223–226. [Google Scholar]

- Rabbani, M.; et al. Anxiolytic effects of Echium amoenum on the elevated plus-maze model of anxiety in mice. Fitoterapia 2004, 75, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potdar, V.H.; Kibile, S.J. Evaluation of antidepressant-like effect of Citrus maxima leaves in animal models of depression. Iranian journal of basic medical sciences 2011, 14, 478. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shafaghi, B.; et al. Anxiolytic effect of Echium amoenum L. in mice. in mice. 2002.

- Yeşilada, E.; et al. Traditional medicine in Turkey. V. Folk medicine in the inner Taurus Mountains. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 1995, 46, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.; et al. Echium amoenum and Rosmarinic Acid Suppress the Growth and Metastasis of Gastric Cancer AGS Cells by Promoting Apoptosis and Inhibiting EMT. 2024(1422-0067 (Electronic)).

- Jedrzejczyk, I.; Rewers, M. Genome size and ISSR markers for Mentha L. (Lamiaceae) genetic diversity assessment and species identification. Industrial Crops and Products 2018, 120, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahar, B.; Chongtham, N. Traditional uses and advances in recent research on wild aromatic plant Mentha longifolia and its pharmacological importance. Phytochemistry Reviews 2024, 23, 529–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.S. , Herbs and Spices: New Processing Technologies. 2021: BoD–Books on Demand.

- Brahmi, F.; et al. Chemical composition and biological activities of Mentha species, in Aromatic and medicinal plants-Back to nature. 2017, IntechOpen.

- Al-Bayati, F.A. Isolation and identification of antimicrobial compound from Mentha longifolia L. leaves grown wild in Iraq. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials 2009, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amzazi, S.; et al. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Inhibitory Activity of Mentha longifolia. Therapies 2003, 58, 531–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulluce, M.; et al. Antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of the essential oils and methanol extract from Mentha longifolia L. ssp. longifolia. Food Chemistry 2007, 103, 1449–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patti, F.; et al. Anticancer Effects of Wild Mountain Mentha longifolia Extract in Adrenocortical Tumor Cell Models. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 1974, 77, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Borris, R.P.; Kim, H.M. Torenia sp. Extracts Contain Multiple Potent Antitumor Compounds with Nematocidal Activity, Triggering an Activated DNA Damage Checkpoint and Defective Meiotic Progression. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2024, 17, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; et al. Exploring the Impact of Onobrychis cornuta and Veratrum lobelianum Extracts on C. elegans: Implications for MAPK Modulation, Germline Development, and Antitumor Properties. Nutrients 2023, 16, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M.; Colaiacovo, M.P. DNA Damage Sensitivity Assays in Caenorhabditis elegans. Bio-Protocol 2015, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M.; Colaiacovo, M.P. ZTF-8 Interacts with the 9-1-1 Complex and Is Required for DNA Damage Response and Double-Strand Break Repair in the C. elegans Germline. PLoS Genet 2014, 10, e1004723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colaiacovo, M.P.; et al. Synaptonemal complex assembly in C. elegans is dispensable for loading strand-exchange proteins but critical for proper completion of recombination. Dev Cell 2003, 5, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M.; Colaiacovo, M.P. New Insights into the Post-Translational Regulation of DNA Damage Response and Double-Strand Break Repair in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 2015, 200, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, K.O.; et al. Caenorhabditis elegans msh-5 is required for both normal and radiation-induced meiotic crossing over but not for completion of meiosis. Genetics 2000, 156, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, D.Y.; Colaiacovo, M.P. Meiotic development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 2013, 757, 133–170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Girard, C.; et al. Interdependent and separable functions of Caenorhabditis elegans MRN-C complex members couple formation and repair of meiotic DSBs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, E4443–E4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Q.; et al. Therapeutic Potential of Lappula patula Extracts on Germline Development and DNA Damage Responses in C. elegans. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2025, 18, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Buul, P.P.; et al. Differential radioprotective effects of misoprostol in DNA repair-proficient and -deficient or radiosensitive cell systems. Int J Radiat Biol 1997, 71, 259–264. [Google Scholar]

- Galvez, M.; Martin-Cordero, C.; Ayuso, M.J. Iridoids as DNA topoisomerase I poisons. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2005, 20, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, E.; et al. Resveratrol affects DNA damage induced by ionizing radiation in human lymphocytes in vitro. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen 2016, 806, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C.L.; et al. Resveratrol-induced apoptosis and increased radiosensitivity in CD133-positive cells derived from atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009, 74, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; et al. Luteolin prevents THP-1 macrophage pyroptosis by suppressing ROS production via Nrf2 activation. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2021, 345, 109573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; et al. Luteoloside Inhibits Proliferation and Promotes Intrinsic and Extrinsic Pathway-Mediated Apoptosis Involving MAPK and mTOR Signaling Pathways in Human Cervical Cancer Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19, 1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; et al. Luteoloside induces G0/G1 arrest and pro-death autophagy through the ROS-mediated AKT/mTOR/p70S6K signalling pathway in human non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2017, 494, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; et al. Luteoloside Inhibits IL-1β-Induced Apoptosis and Catabolism in Nucleus Pulposus Cells and Ameliorates Intervertebral Disk Degeneration. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, B.; et al. Thymol, thyme, and other plant sources: Health and potential uses. Phytotherapy research: PTR 2018, 32, 1688–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slamenová, D.; et al. DNA-protective effects of two components of essential plant oils carvacrol and thymol on mammalian cells cultured in vitro. Neoplasma 2007, 54, 108–112. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; et al. Thymol inhibits bladder cancer cell proliferation via inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2017, 491, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; et al. Thymol Inhibits LPS-Stimulated Inflammatory Response via Down-Regulation of NF-κB and MAPK Signaling Pathways in Mouse Mammary Epithelial Cells. Inflammation 2014, 37, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; et al. Chemical Composition and Anti-Inflammatory, Cytotoxic and Antioxidant Activities of Essential Oil from Leaves of Mentha piperita Grown in China. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e114767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.M.; et al. Structure-Antioxidant Activity Relationships of Luteolin and Catechin. Journal of Food Science 2020, 85, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; et al. Nonhomologous end joining and homologous recombination involved in luteolin-induced DNA damage in DT40 cells. Toxicology in Vitro 2020, 65, 104825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.-C.; et al. Luteolin attenuates TGF-β1-induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition of lung cancer cells by interfering in the PI3K/Akt–NF-κB–Snail pathway. Life Sciences 2013, 93, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabavi, S.F.; et al. Luteolin as an anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective agent: A brief review. Brain Research Bulletin 2015, 119 Pt A, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calleja, M.A.; et al. The antioxidant effect of β-caryophyllene protects rat liver from carbon tetrachloride-induced fibrosis by inhibiting hepatic stellate cell activation. British Journal of Nutrition 2013, 109, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, H.-W.; et al. Beta-Caryophyllene Augments Radiotherapy Efficacy in GBM by Modulating Cell Apoptosis and DNA Damage Repair via PPARγ and NF-κB Pathways. Phytotherapy research: PTR 2025, 39, 776–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahham, S.S.; et al. The Anticancer, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of the Sesquiterpene β-Caryophyllene from the Essential Oil of Aquilaria crassna. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2015, 20, 11808–11829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakır, B.; et al. Investigation of the anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities of-caryophyllene. International Journal of Essential Oil Therapeutics 2008, 2, 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wójciak, M.; et al. Antioxidant Potential of Diosmin and Diosmetin against Oxidative Stress in Endothelial Cells. Molecules 2022, 27, 8232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; et al. Diosmetin protects against retinal injury via reduction of DNA damage and oxidative stress. Toxicology Reports 2016, 3, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; et al. Diosmetin inhibits tumor development and block tumor angiogenesis in skin cancer. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2019, 117, 109091. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.-h.; et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of natural flavonoid diosmetin in IL-4 and LPS-induced macrophage activation and atopic dermatitis model. International Immunopharmacology 2020, 89, 107046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-J.; Chan, W.-H. Genistein protects methylglyoxal-induced oxidative DNA damage and cell injury in human mononuclear cells. Toxicology in vitro: an international journal published in association with BIBRA 2007, 21, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; et al. Genistein-induced DNA damage is repaired by nonhomologous end joining and homologous recombination in TK6 cells. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2019, 234, 2683–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tominaga, Y.; et al. Genistein inhibits Brca1 mutant tumor growth through activation of DNA damage checkpoints, cell cycle arrest, and mitotic catastrophe. Cell Death & Differentiation 2007, 14, 472–479. [Google Scholar]

- Hämäläinen, M.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Flavonoids: Genistein, Kaempferol, Quercetin, and Daidzein Inhibit STAT-1 and NF-κB Activations, Whereas Flavone, Isorhamnetin, Naringenin, and Pelargonidin Inhibit only NF-κB Activation along with Their Inhibitory Effect on iNOS Expression and NO Production in Activated Macrophages. Mediators of Inflammation 2007, 2007, 45673. [Google Scholar]

- Jayachandran, M.; et al. Isoquercetin upregulates antioxidant genes, suppresses inflammatory cytokines and regulates AMPK pathway in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2019, 303, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, D.d.C.; et al. Antitumor effect of isoquercetin on tissue vasohibin expression and colon cancer vasculature. Oncotarget 2022, 13, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; et al. Isoquercetin ameliorates myocardial infarction through anti-inflammation and anti-apoptosis factor and regulating TLR4-NF-κB signal pathway. Molecular Medicine Reports 2018, 17, 6675–6680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-desoky, A.H.; et al. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of naringin isolated from Carissa carandas L.: In vitro and in vivo evidence. Phytomedicine 2018, 42, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, K.; et al. Naringin inhibits gamma radiation-induced oxidative DNA damage and inflammation, by modulating p53 and NF-κB signaling pathways in murine splenocytes. Free Radical Research 2015, 49, 422–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; et al. Naringin inhibits growth and induces apoptosis by a mechanism dependent on reduced activation of NF-κB/COX-2-caspase-1 pathway in HeLa cervical cancer cells. International Journal of Oncology 2014, 45, 1929–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento, P.G.G.; et al. Antibacterial and antioxidant activities of ursolic acid and derivatives. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2014, 19, 1317–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, A.A.; Pereira-Wilson, C.; Collins, A.R. Protective effects of Ursolic acid and Luteolin against oxidative DNA damage include enhancement of DNA repair in Caco-2 cells. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 2010, 692, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassi, E.; et al. Ursolic acid, a naturally occurring triterpenoid, demonstrates anticancer activity on human prostate cancer cells. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology 2007, 133, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Checker, R.; et al. Potent Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Ursolic Acid, a Triterpenoid Antioxidant, Is Mediated through Suppression of NF-κB, AP-1 and NF-AT. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e31318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrizzo, A.; et al. Antioxidant effects of resveratrol in cardiovascular, cerebral and metabolic diseases. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2013, 61, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgambato, A.; et al. Resveratrol, a natural phenolic compound, inhibits cell proliferation and prevents oxidative DNA damage. Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis 2001, 496, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, S.J.; et al. Resveratrol, Acetyl-Resveratrol, and Polydatin Exhibit Antigrowth Activity against 3D Cell Aggregates of the SKOV-3 and OVCAR-8 Ovarian Cancer Cell Lines. Obstetrics and Gynecology International 2015, 2015, 279591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Das, D.K. Anti-Inflammatory Responses of Resveratrol. Inflammation & Allergy - Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets - Inflammation & Allergy) 2007, 6, 168–173. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.-W.; et al. Aucubin Protects Chondrocytes Against IL-1β-Induced Apoptosis In Vitro And Inhibits Osteoarthritis In Mice Model. Drug Design, Development and Therapy 2019, 13, 3529–3538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; et al. Aucubin Exerts Anticancer Activity in Breast Cancer and Regulates Intestinal Microbiota. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2022, 2022, 4534411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.S.; Chang, I.-M. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Aucubin by Inhibition of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Production in RAW 264.7 Cells. Planta Medica 2004, 70, 778–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breinholt, V.; et al. Dose-response effects of lycopene on selected drug-metabolizing and antioxidant enzymes in the rat. Cancer Letters 2000, 154, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.H.; et al. Lycopene inhibits Helicobacter pylori-induced ATM/ATR-dependent DNA damage response in gastric epithelial AGS cells. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2012, 52, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Lim, J.W.; Kim, H. Lycopene Inhibits Reactive Oxygen Species-Mediated NF-κB Signaling and Induces Apoptosis in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Nutrients 2019, 11, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadad, N.; Levy, R. The synergistic anti-inflammatory effects of lycopene, lutein, β-carotene, and carnosic acid combinations via redox-based inhibition of NF-κB signaling. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2012, 53, 1381–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beeharry N, L.J.; Hernandez, A.R.; Chambers, J.A.; Fucassi, F.; Cragg, P.J.; Green, M.H.; Green, I.C. Linoleic acid and antioxidants protect against DNA damage and apoptosis induced by palmitic acid. Mutat Res 2003, 530, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauson, C.B.N.; et al. Linoleic acid potentiates CD8+ T cell metabolic fitness and antitumor immunity. Cell Metabolism 2023, 35, 633–650.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon-Gil, J.; et al. Neuroprotective and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Linoleic Acid in Models of Parkinson’s Disease: The Implication of Lipid Droplets and Lipophagy. Cells 2022, 11, 2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgic, S.; Ozgocmen, M. The protective effect of misoprostol against doxorubicin induced liver injury. Biotechnic & Histochemistry 2019, 94, 583–591. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; et al. Homoplantaginin alleviates intervertebral disc degeneration by blocking the NF-κB/MAPK pathways via binding to TAK1. Biochemical Pharmacology 2024, 226, 116389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, X.-x.; et al. HPLC determination of malondialdehyde in ECV304 cell culture medium for measuring the antioxidant effect of vitexin-4″-O-glucoside. Archives of Pharmacal Research 2008, 31, 878–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, W.; et al. Effects of vitexin-2″-O-rhamnoside and vitexin-4″-O-glucoside on growth and oxidative stress-induced cell apoptosis of human adipose-derived stem cells. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2014, 66, 988–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, B.; et al. Plants of Genus Mentha: From Farm to Food Factory. Plants 2018, 7, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefian, S., F. Esmaeili, and T. Lohrasebi, A Comprehensive Review of the Key Characteristics of the Genus Mentha, Natural Compounds and Biotechnological Approaches for the Production of Secondary Metabolites. Iranian Journal of Biotechnology 2023, 21, e3605. [Google Scholar]

- Kajimoto, T.; et al. Iridoids from Scrophularia ningpoensis. Phytochemistry 1989, 28, 2701–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazawa, M.; et al. Suppression of SOS-inducing activity of chemical mutagens by cinnamic acid derivatives from Scrophulia ningpoensis in the Salmonella typhimurium TA1535/pSK1002 umu test. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 1998, 46, 904–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Hunkler, D.; Rimpler, H. Iridoid-related aglycone and its glycosides from Scrophularia ningpoensis. Phytochemistry 1992, 31, 905–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, T.; et al. Traditional medicine in Turkey VII. Folk medicine in middle and west Black Sea regions. Economic botany, 1995: p. 406-422.

- Amabeoku, G.J.; et al. Antipyretic and antinociceptive properties of mentha longifoliaHuds. (Lamiaceae) leaf aqueous extract in rats and mice. Methods and Findings in Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology 2009, 31, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimian, P.; Gholamreza, K.; Amirghofran, Z. Anti-inflammatory effect of Mentha longifolia in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages: Reduction of nitric oxide production through inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Journal of Immunotoxicology 2013, 10, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afkar, S.; Somaghian, S.A. Determining of chemical composition, anti-pathogenic and anticancer activity of Mentha longifolia essential oil collected from Iran. Natural Product Research 2024, 0, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, I.; Dilshad, E. A comparative study of Mentha longifolia var. asiatica and Zygophyllum arabicum ZnO nanoparticles against breast cancer targeting Rab22A gene. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0308982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beheshtian, N.; et al. Mentha longifolia L. Inhibits Colorectal Cancer Cell Proliferation and Induces Apoptosis via Caspase Regulation. International Journal of Translational Medicine 2023, 3, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elansary, H.O.; et al. Polyphenol Profile and Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Activities of Natural Mentha × piperita and Mentha longifolia Populations in Northern Saudi Arabia. Processes 2020, 8, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, F.; et al. Appraisals on the anticancer properties of Mentha species using bioassays and docking studies. Industrial Crops and Products 2023, 203, 117128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelidari, H.R.; et al. Anticancer Effect of Solid-Lipid Nanoparticles Containing Mentha longifolia and Mentha pulegium Essential Oils: In Vitro Study on Human Melanoma and Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Biointerface Research in Applied Chemistry 2021, 12, 2128–2137. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; et al. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Mentha Longifolia leaf and investigation of its anti-human breast carcinoma properties in the in vitro condition. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2021, 14, 102931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, M.T.; Mostafa, A.A.; Al-Askar, A.A. Anticandidal and anti-carcinogenic activities of Mentha longifolia (Wild Mint) extracts in vitro. Journal of King Saud University - Science 2020, 32, 2046–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanagh, F.M.; et al. Anti-inflammatory and collagenation effects of zinc oxide-based nanocomposites biosynthesised with Mentha longifolia leaf extract. Journal of Wound Care 2023, 32, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asemani, Y.; et al. Modulation of in vitro proliferation and cytokine secretion of human lymphocytes by Mentha longifolia extracts. Avicenna Journal of Phytomedicine 2019, 9, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; et al. Chemical constituents and biological activities of essential oil from Mentha longifolia: effects of different extraction methods. International Journal of Food Properties 2020, 23, 1951–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadkhah, A.; et al. Assessing the effect of Mentha longifolia essential oils on COX-2 expression in animal model of sepsis induced by caecal ligation and puncture. Pharmaceutical Biology 2018, 56, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haikal, A.; et al. Anti-asthmatic and antioxidant activity of flavonoids isolated from Mentha longifolia subspecies typhoides (Briq. ) Harley. and Mentha longifolia subspecies schimperi (Briq.) Briq. on ovalbumin-induced allergic asthma in mice: In-vivo and in-silico study. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2025, 339, 119133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, A. anti-acetylcholinesterase, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of Mentha longifolia for treating Alzheimer disease. Der Pharmacia Lettre 2016, 8, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, M.; et al. Exploring the bioactive potential of Mentha longifolia from Northeast India: an inclusive study on phytochemical composition and biological activities. Journal of Essential Oil Bearing Plants 2024, 27, 1102–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.V.; et al. Anti-inflammatory activities of some Mentha essential oils in lipopolysaccharide-activated macrophages. Tạp chí Nghiên cứu Dược và Thông tin Thuốc, 2025.

- Raeisi, H.; et al. Pleiotropic effects of Mentha longifolia L. extract on the regulation of genes involved in inflammation and apoptosis induced by Clostridioides difficile ribotype 001. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourabi, M.; et al. Efficacy of various extracting solvents on phytochemical composition, and biological properties of Mentha longifolia L. leaf extracts. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 18028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janifer, R.X.; et al. Determination of Total Phenols, Free Radical Scavenging and Antibacterial Activities of Mentha longifolia Linn. Hudson from the Cold Desert, Ladakh, India. Pharmacognosy Journal 2010, 2, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanisavljević, D.M.; et al. Antioxidant activity, the content of total phenols and flavonoids in the ethanol extracts of Mentha longifolia (L.) Hudson dried by the use of different techniques. Chemical Industry and Chemical Engineering Quarterly 2012, 18, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; et al. Green synthesis of Ag/Fe3O4 nanoparticles using Mentha longifolia flower extract: evaluation of its antioxidant and anti-lung cancer effects. Heliyon 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z, G., K. Asres, and A. Mazumder, Comparison of the Essential Oil Composition, Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities of Four Mentha Species Growing in Ethiopia. Ethiop. Pharm. J. 2007, 25, 91–102.

- Al-janabi, A.A.; Sahib, A.A.; Ali, F.J. Studying The Effect of Mentha Longifolia Plant Extract In Inhibition Growth of Some Bacteria and Inhibiting the Emergence Fourth Stage Larvae of Mosquitoes Aedes Aegypti. Indian Journal of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mijalli, S.H.; et al. Phytochemical Variability, In Vitro and In Vivo Biological Investigations, and In Silico Antibacterial Mechanisms of Mentha piperita Essential Oils Collected from Two Different Regions in Morocco. Foods 2022, 11, 3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, S.; et al. Exploring the antibacterial, antidiabetic, and anticancer potential of Mentha arvensis extract through in-silico and in-vitro analysis. BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies 2023, 23, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazyzadeh, M.; et al. Evaluation of the Antibacterial Activity of Mentha Longifolia Essential Oil against Enterococcus faecalis and its Chemical Composition. Journal of Dentistry 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Jahani, E.; Babaeekhou, L.; Ghane, M. Chemical composition and antibacterial properties of Zataria multiflora Bioss and Mentha longifolia essential oils in combination with nisin and acid acetic. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2021, 45, e15742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, M. The antibacterial activity of Mentha, in Herbs and spices. 2020, IntechOpen.

- Mohammadi-Aloucheh, R.; et al. Green synthesis of ZnO and ZnO/CuO nanocomposites in Mentha longifolia leaf extract: characterization and their application as anti-bacterial agents. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics 2018, 29, 13596–13605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shnawa, B.H.; et al. Scolicidal activity of biosynthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles by Mentha longifolia L. leaves against Echinococcus granulosus protoscolices. Emergent Materials 2022, 5, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; et al. Effects of Scrophularia ningpoensis Hemsl. on Inhibition of Proliferation, Apoptosis Induction and NF-?B Signaling of Immortalized and Cancer Cell Lines. Pharmaceuticals 2012, 5, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudarzvand, M.; et al. Immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects of Scrophularia megalantha ethanol extract on an experimental model of multiple sclerosis. Research Journal of Pharmacognosy 2019, 6, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.M.; et al. Fast repairing of oxidized OH radical adducts of dAMP and dGMP by phenylpropanoid glycosides from Scrophularia ningpoensis Hemsl. Acta pharmacologica Sinica 2000, 21, 1125–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Bahmani, M.; et al. A comparative study on the effect of ethanol extract of wild Scrophularia deserti and streptomycin on Brucellla melitensis. Journal of Herbmed Pharmacology 2013, 2, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, M.A., M. D. García, and M.T. Sáenz, Antibacterial activity of the phenolic acids fractions of Scrophularia frutescens and Scrophularia sambucifolia. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 1996, 53, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayobi, H.; et al. Antibacterial Effects of Scrophularia striata Extract on Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Journal of Medicinal Plants 2014, 13, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Lewenhofer, V.; et al. Chemical Composition of Scrophularia lucida and the Effects on Tumor Invasiveness in Vitro. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musa, A.; et al. Prominent antidiabetic and anticancer investigation of Scrophularia deserti extract: Integration of experimental and computational approaches. Journal of Molecular Structure 2024, 1315, 138769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namvaran, A.; et al. Effects of Scrophularia oxysepala Methanolic Extract on Early Stages of Dimethylhydrazine-Induced Colon Carcinoma in Rats: Apoptosis Pathway Approach. Advanced Pharmaceutical Bulletin 2022, 12, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, B.; et al. Scropolioside-D2 and Harpagoside-B: Two New Iridoid Glycosides from Scrophularia deserti and Their Antidiabetic and Antiinflammatory Activity. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin 2003, 26, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadmehr, A.; et al. Antioxidant and Neuroprotective Effects of Scrophularia striata Extract Against Oxidative Stress-Induced Neurotoxicity. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology 2013, 33, 1135–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, S.-H.; Yang, C.-H.; Kim, S.-C. Inhibitory effect of Scrophulariae Radix extract on TNF-alpha,IL-1beta, IL-6 and Nitric Oxide production in lipopolysaccharide - activated Raw 264.7 cells. The Korea Journal of Herbology 2005, 20, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dı́az, A.M.a.; et al. Phenylpropanoid glycosides from Scrophularia scorodonia: In vitro anti-inflammatory activity. Life Sciences 2004, 74, 2515–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, A.; et al. Investigation of anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects of hydroalcoholic extract of Scrophularia striata seeds in male mice. Iranian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology 2019, 3, 40–34. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, M.A.; Sáenz, M.T.; García, M.D. Anti-inflammatory Activity in Rats and Mice of Phenolic Acids Isolated from Scrophularia frutescens. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 1998, 50, 1183–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giner, R.-M.a.; et al. Anti-inflammatory glycoterpenoids from Scrophularia auriculata. European Journal of Pharmacology 2000, 389, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi Pour Sabet, S.; Bahramikia, S.; Baghaifar, Z. Evaluation of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of hydroalcoholic and methanolic extracts of Scrophularia striata: Inhibition of albumin protein denaturation and stabilization of erythrocyte membrane. Applied Biology 2023, 35, 150–162. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, Y.-F.; et al. Two new compounds from the roots of Scrophularia ningpoensis and their anti-inflammatory activities. Journal of Asian Natural Products Research 2019, 21, 1083–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, G.; et al. Scrodentoids H and I, a Pair of Natural Epimerides from Scrophularia dentata, Inhibit Inflammation through JNK-STAT3 Axis in THP-1 Cells. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2020, 2020, 1842347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.N.A.; et al. Anti-inflammatory Effects of Scrophularia buergeriana Extract Mixture Fermented with Lactic Acid Bacteria. Biotechnology and Bioprocess Engineering 2022, 27, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, N.-R.; et al. Scrophularia buergeriana attenuates allergic inflammation by reducing NF-κB activation. Phytomedicine 2020, 67, 153159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.a.; et al. Polysaccharides of Scrophularia ningpoensis Hemsl.: Extraction, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Evaluation. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2020, 2020, 8899762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, G.; et al. Scrophularia lucida L. as a valuable source of bioactive compounds for pharmaceutical applications: In vitro antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, enzyme inhibitory properties, in silico studies, and HPLC profiles. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2019, 162, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokhani, N.; et al. Determination and evaluating the antioxidant properties of ziziphus nummularia (burm. F.) wight & arn., crataegus pontica K. Koch and scrophularia striata boiss. Egyptian Journal of Veterinary Sciences 2022, 53, 423–429. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, E.J.; et al. Cognitive-enhancing and antioxidant activities of iridoid glycosides from Scrophularia buergeriana in scopolamine-treated mice. European Journal of Pharmacology 2008, 588, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, E.J.; et al. KD-501, a standardized extract of Scrophularia buergeriana has both cognitive-enhancing and antioxidant activities in mice given scopolamine. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2009, 121, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; et al. Neuroprotective effects of Scrophularia buergeriana extract against glutamate-induced toxicity in SH-SY5Y cells. International Journal of Molecular Medicine 2019, 43, 2144–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboubi, M.; Kazempour, N.; Boland Nazar, A.R. Total Phenolic, Total Flavonoids, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Scrophularia Striata Boiss Extracts. Jundishapur Journal of Natural Pharmaceutical Products 2013, 8, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roya Alizadeh, S.; et al. Scrophularia striata extract mediated synthesis of gold nanoparticles; their antibacterial, antileishmanial, antioxidant, and photocatalytic activities. Inorganic Chemistry Communications 2023, 156, 111138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri, H.; et al. Evaluation of Antioxidant Potential and Free Radical Scavenging Activity of Methanol Extract from Scrophularia striata. Acta Biochimica Iranica 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargoosh, Z.; et al. Effects of ecological factors on the antioxidant potential and total phenol content of Scrophularia striata Boiss. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 16021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akşit, Z. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of Scrophularia catariifolia Boiss. & Heldr essential oil. Journal of Essential Oil Bearing Plants 2025, 28, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimzadeh, M.A.; et al. In vitro cytotoxicity against human cancer cell lines (MCF-7 and AGS), antileishmanial and antibacterial activities of green synthesized silver nanoparticles using Scrophularia striata extract. Surfaces and Interfaces 2021, 23, 100963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, A.A.; et al. Chemical composition and biological activities of Scrophularia striata extracts. Minerva Biotecnologica 2014, 26, 183–189. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; et al. Study of chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of leaves and roots of Scrophularia ningpoensis. Natural Product Research 2009, 23, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; et al. The in vitro and in vivo antibacterial activities of uniflorous honey from a medicinal plant, Scrophularia ningpoensis Hemsl. , and characterization of its chemical profile with UPLC-MS/MS. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2022, 296, 115499. [Google Scholar]

- Mameneh, R.; et al. Characterization and antibacterial activity of plant mediated silver nanoparticles biosynthesized using Scrophularia striata flower extract. Russian Journal of Applied Chemistry 2015, 88, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasdaran, A.; et al. Chemical Composition, and Antibacterial (Against Staphylococcus aureus) and Free-Radical-Scavenging Activities of the Essential Oil of Scrophularia amplexicaulis Benth. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Renda, G.; et al. Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of the Essential Oils of Five Scrophularia L. Species from Turkey. Records of Natural Products 2017, 11, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafati-chaleshtori, R.; Rafieian-kopaei, M. Screening of antibacterial effect of the Scrophularia Striata against E. coli in vitro. Journal of Herbmed Pharmacology 2014, 3, 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Stavri, M.; Mathew, K.T.; Gibbons, S. Antimicrobial constituents of Scrophularia deserti. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 1530–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavarideh, F.; Pourahmad, F.; Nemati, M. Diversity and antibacterial activity of endophytic bacteria associated with medicinal plant, Scrophularia striata. Veterinary Research Forum 2022, 13, 409–415. [Google Scholar]

- Yook, K.-D. Antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity test of Scrophularia ningpoensis hemsl extracts against Klebsiella pneumoniae. Journal of the Korea Society of Computer and Information 2016, 21, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangeneh, M.M.; et al. Assessment of In Vitro Antibacterial Properties of the Hydroalcoholic Extract of Scrophularia striata Against Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC No. 25923). International Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemical Research 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, N.; Kalantar, K.; Amirghofran, Z. Anti-inflammatory activity of Echium amoenum extract on macrophages mediated by inhibition of inflammatory mediators and cytokines expression. Research in Pharmaceutical Sciences 2018, 13, 73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Asghari, B.; et al. Therapeutic target enzymes inhibitory potential, antioxidant activity, and rosmarinic acid content of Echium amoenum. South African Journal of Botany 2019, 120, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, M. Farahani, M., Q. Branch, and I. Azad, Antiviral effect assay of aqueous extract of Echium amoenum-L against HSV-1. Zahedan J Res Med Sci 2013, 15, 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Abolhassani, M. Clinical research Antiviral activity of borage (Echium amoenum). Archives of Medical Science 2010, 6, 366–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamholo, M. Antiradical and antibacterial activity of Echium altissimum extracts on human infective bacteria and chemical composition analysis. Microbiology, Metabolites and Biotechnology 2020, 3, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- El-Tantawy, H.M., A.R. Hassan, and H.E. Taha, Antioxidant potential and LC/MS metabolic profile of anticancer fractions from Echium angustifolium Mill. aerial parts. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science 2021, 11, 200–208.

- El-Tantawy, H.M.; Hassan, A.R.; Taha, H.E. Anticancer mechanism of the non-polar extract from Echium angustifolium Mill. aerial parts in relation to its chemical content. Egyptian Journal of Chemistry 2022, 65, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazeli, M. The effect of Echium amoenum hydro-methanolic extract on MCF-7 and MDA-MB468 breast cancer cell lines and increasing the cytotoxicity of doxorubicin. Iranian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology 2023, 7, 84–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; et al. Comparative analysis of the main medicinal substances and applications of Echium vulgare L. and Echium plantagineum L.: A review. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2022, 285, 114894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, A.; et al. Effect of Echium amoenum Fisch. et Mey a Traditional Iranian Herbal Remedy in an Experimental Model of Acute Pancreatitis. International Scholarly Research Notices 2012, 2012, 141548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benlakhdar, H.; et al. Chemical Composition and Anti-inflammatory Activity of the Essential Oil of Echium humile (Boraginaceae) in vivo from South-West of Algeria. Jordan Journal of Biological Sciences 2021, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Eruygur, N.; Yilmaz, G.; Üstün, O. Analgesic and antioxidant activity of some Echium species wild growing in Turkey. FABAD Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2012, 37, 151. [Google Scholar]

- Heidari, M.R.; Azad, E.M.; Mehrabani, M. Evaluation of the analgesic effect of Echium amoenum Fisch & C.A. Mey. extract in mice: Possible mechanism involved. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2006, 103, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kitessa, S.M., P.D. Nichols, and M. Abeywardena, Purple Viper's Bugloss (Echium plantagineum) Seed Oil in Human Health, in Nuts and Seeds in Health and Disease Prevention, V.R. Preedy, R.R. Watson, and V.B. Patel, Editors. 2011, Academic Press: San Diego. p. 951-958.

- Mir, M. Echium oil: A valuable source of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids. Oléagineux, Corps gras, Lipides 2008, 15, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moita, E.; et al. Integrated Analysis of COX-2 and iNOS Derived Inflammatory Mediators in LPS-Stimulated RAW Macrophages Pre-Exposed to Echium plantagineum L. Bee Pollen Extract. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e59131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, R.; et al. Echium plantagineum L. honey: Search of pyrrolizidine alkaloids and polyphenols, anti-inflammatory potential and cytotoxicity. Food Chemistry 2020, 328, 127169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi Larki, R.; et al. Protective Effects of Echium amoenum on Oxidative Stress and Gene Expression Induced by Permethrin in Wistar Rats. Hepatitis Monthly 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaszadeh, S.; Rajabian, T.; Taghizadeh, M. Antioxidant Activity, Phenolic and Flavonoid Contents of Echium Species from Different Geographical Locations of Iran. Journal of Medicinal plants and By-Products 2013, 2, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Abdol, N.; Setorki, M. Evaluation of Antidepressant, Antianxiolytic, and Antioxidant Effects of Echium amoenum L. Extract on Social Isolation Stress of Male Mice. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel Pilerood, S.; Prakash, J. Evaluation of nutritional composition and antioxidant activity of Borage (Echium amoenum) and Valerian (Valerian officinalis). Journal of Food Science and Technology 2014, 51, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Rimawi, F.; et al. Free radicals and enzymes inhibitory potentials of the traditional medicinal plant Echium angustifolium. European Journal of Integrative Medicine 2020, 38, 101196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsanie, W.; et al. Viper's Bugloss (Echium Vulgare L) Extract as A Natural Antioxidant and Its Effect on Hyperlipidemia. 2018. Volume 8: p. 81-89.

- Aouadi, K.; et al. HPLC/MS Phytochemical Profiling with Antioxidant Activities of Echium humile Desf. Extracts: ADMET Prediction and Computational Study Targeting Human Peroxiredoxin 5 Receptor. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbrinis, S. In vitro and In vivo anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotector effects of Algerian Echium plantagineum and Brassica rapa extracts. 2024.

- Mehran, M., S. Masoum, and M. Memarzadeh, Improvement of thermal stability and antioxidant activity of anthocyanins of Echium amoenum petal using maltodextrin/modified starch combination as wall material. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 148, 768–776. [CrossRef]

- Safaeian, L.; et al. Cytoprotective and antioxidant effects of Echium amoenum anthocyanin-rich extract in human endothelial cells (HUVECs). Avicenna Journal of Phytomedicine 2015, 5, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Uysal, İ.; et al. Antioxidant and Oxidant status of medicinal plant Echium italicum collected from different regions. Turkish Journal of Agriculture - Food Science and Technology 2021, 9, 1902–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolhassani, M. Antibacterial effect of borage (Echium amoenum) on Staphylococcus aureus. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases 2004, 8, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atessahin, D.A.; et al. Evaluation of cytotoxic, antimicrobial, and antioxidant activities of Echium italicum L. in MCF-7 and HepG2 cell lines. International Journal of Plant Based Pharmaceuticals 2025, 5, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaïss, A.; et al. Phytochemical Profiling, Antimicrobial and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Potential of Phenolic-Enriched Extracts of the Aerial Parts from Echium humile Desf.: In Vitro Combined with In Silico Approach. Plants 2022, 11, 1131. [Google Scholar]

- Kavehei, M.; Sefidroo, S.H. Investigating the Antimicrobial Activity of Different Extracts of Echium on Selected Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria. Tabari Biomedical Student Research Journal 2023, 5, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morteza-Semnani, K.; Saeedi, M.; Akbarzadeh, M. Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oil of Echium italicum L. Journal of Essential Oil Bearing Plants, 2009. Journal of Essential Oil Bearing Plants 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nabipour*, F.; et al. Evaluation of the Antifungal effects of various Extracts of the Aerial part and Root of Echium italicum on Candida albicans compared with two common antibiotics. Yafteh 2019, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Sabour, M.; et al. Evaluation of the antibacterial effect of Echium amoenum Fisch. et Mey. against multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strains isolated from burn wound infection. Novelty in Biomedicine 2015, 3, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Shariatifar, N.; Fathabad, A.E.; Madihi, S. Antibacterial activity of aqueous and ethanolic extracts of Echium amoenum on food-borne pathogens. Journal of Food Safety and Hygiene 2016, 2, 63–63. [Google Scholar]

- Tabata, M.; Tsukada, M.; Fukui, H. Antimicrobial Activity of Quinone Derivatives from Echium lycopsis Callus Cultures. Planta Medica 1982, 44, 234–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeharry, N.; et al. Linoleic acid and antioxidants protect against DNA damage and apoptosis induced by palmitic acid. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 2003, 530, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genus | Taxonomy | Characteristics | Distribution | Sample Used in this study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mentha | Defined as 18–30 species across five sections: Mentha, Preslia, Audibertia, Eriodontes, Pulegium. Includes M. spicata, M. aquatica, M. arvensis, M. longifolia [20,21,96,97] | Aromatic, herbaceous perennials with extensive stolons [97] | Widely distributed: Northern Pakistan, Europe, Nepal, India, Western China, Germany, UK, Egypt, Nigeria, Turkey [21] | Mentha longifolia |

| Scrophularia | Genus Scrophularia (Scrophulariaceae); ~300 species [2] | Mostly herbaceous perennials; also subshrubs, biennials, or annuals [3] | Temperate Asia, Mediterranean Europe, North America [1] | Scrophularia orientalis |

| Echium | Genus Echium (Boraginaceae); ~60 species, 30 in Canary Islands, 24 endemic [9] | Annual, biennial, or perennial flowering plants [9,10] | Native to North Africa, Europe, Macaronesia (Azores, Madeira, Canaries, Cape Verde) [9,10] | Echium biebersteinii |

| No | Compounds | Antioxidant | DNA damage response/repair | Anti-tumor | Anti-inflammatory |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Luteolin-7-O-Rucoside | [43] | [44] | [45] | [46] |

| 2 | Thymol | [47] | [48] | [49] | [50] |

| 3 | Carvyl acetate | ||||

| 4 | Menthyl Acetate | [51] | |||

| 5 | Luteolin | [52] | [53] | [54] | [55] |

| 6 | Caryophyllene | [56] | [57] | [58] | [59] |

| 7 | Geranium lignin/Diosmetin | [60] | [61] | [62] | [63] |

| 8 | Genistein | [64] | [65] | [66] | [67] |

| 9 | Isoquercetin | [68] | [69] | [70] | |

| 10 | Naringin | [71] | [72] | [73] | |

| 11 | Ursolic acid | [74] | [75] | [76] | [77] |

| 12 | Phlogistic acid | ||||

| 13 | Dihydrocarvone | ||||

| 14 | Resveratrol | [78] | [79] | [80] | [81] |

| 15 | Aucubin | [82] | [83] | [84] | |

| 16 | Lycopene | [85] | [86] | [87] | [88] |

| 17 | Linoleic acid | [215] | [90] | [91] | |

| 18 | Misoprostol | [92] | |||

| 19 | Homoplantain | [93] | |||

| 20 | Vitexin-4-O-glucoside | [94] | |||

| 21 | Vitexin-4-rhamnoside | [95] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).