1. Introduction

IC 10 is a young starburst galaxy in the constellation Cassiopeia. This irregular galaxy is a part of the Local Group [

1,

2] at a distance of 660 kpc from our Galaxy (the measurements range from 660 [

3] to 817 [

4] kpc). It is an excellent laboratory to study the high-mass X-ray binaries (HMXBs) containing the most massive young stars. This galaxy is also a subject of multiple observations due to its highly dense Wolf-Rayet stellar population. The high number of Wolf-Rayet (WR) stars discovered by Massey et al. [

5] and Massey and Armandroff [

6] was the primary indicator of IC 10’s starburst nature. These investigations were spurred on by the discovery of 144 H

ii regions by Hodge and Lee [

7], the brightest of which was known to be on par with the brightest H

ii region observed in the SMC [

8]. The surface density of WR stars throughout IC 10 is similar to that of the most active OB associations in M33 [

9]. According to Wilcots and Miller [

10], IC 10 is experiencing a star formation burst that is most likely being caused by gas infalling from an extended cloud that is counterrotating with respect to the galaxy’s proper motion.

The Local Group, which includes about 55 galaxies in a volume of diameter 3 Mpc, is the term used to identify our own neighborhood in the universe. IC 10 is one of the irregular dwarf galaxies that reside in the Local Group, although it is relatively far from the two most massive galaxies, our Galaxy and M31. The galaxy has been described as a blue compact dwarf (BCD) because of its surface brightness after taking into account the foreground reddening [

11]. However, it is situated at a very low Galactic latitude (

), and its line of sight is heavily affected by foreground reddening which hampers the optical observations. IC 10 consists of the main body and several distinct star-forming regions. Several H

i holes are found throughout the galaxy, which are most probably the cumulative effect of powerful stellar winds [

12]. The overall structure indicates recent widespread star-formation activity.

IC 10 presents a suitable environment to study multiple physical properties due to its similarities with the LMC and the SMC. The SMC and IC 10 have a lot in common: they are both gas-rich irregular dwarfs believed to have experienced tidal disruption recently, which sparked intense star formation. Two significant characteristics, however, set IC 10 apart and make it a new type of laboratory for stellar astrophysics: (a) The duration of its starburst is only 6 Myr, whereas the ages of the populations discovered in the SMC range between 40-200 Myr, where the HMXBs are found in the 40–70 Myr subpopulation [

13]. (b) The metallicity of IC 10 (Z = Z

⊙) is midway between those of the SMC and the Milky Way.

Comprehensive censuses of X-ray binary populations in local-group galaxies offer an effective approach for identifying fundamental properties of star formation and evolution, such as starburst age/duration and the impact of the host’s metallicity. The Magellanic Clouds have historically played this role, but new independent testbeds (like IC 10 and NGC 300) must be utilized in order to properly understand secular variances between galaxies. For instance, a detailed analysis of the dataset reported here has shown that a recent (3-8 Myr) star-forming event with a rate of

is needed to explain the current XRB population of IC 10 [

14].

The Local Group’s maximum surface density of WR stars is found in IC 10; yet, the ratio of WC/WN spectral classes differs from that predicted by stellar evolution models for a galaxy with such low metallicity. Thus, the WC/WN ratio in IC 10 is certainly peculiar, notwithstanding the recent discovery of three new WN stars, which reduces the ratio from 1.3 to 1. So, IC 10 is still regarded as an anomaly given the WC/WN ratio of ∼0.2 for the LMC and ∼0.1 for the SMC. However, this marked difference also suggests that the starburst observed in IC 10 is quite recent.

IC 10 is also a functional testbed for studying HMXB populations. In young starburst galaxies ( Myr), the X-ray populations are expected to consist of massive stars and neutron star or black hole (NS or BH) binaries. IC 10 is the nearest among such galaxies. For these reasons, we have used archival and new Chandra X-ray data from multiple epochs to monitor the transient X-ray population of IC 10.

This article is arranged in the following way: The observations and data reductions are described in

Section 2. The main results are presented and analyzed in

Section 3,

Section 4,

Section 5 and

Section 6. A discussion of the underlying populations and a summary along with conclusions are included in

Section 7 and

Section 8, respectively.

2. Observations: New and Archival

IC 10 has been the target of multiple X-ray observations (11

Chandra, 2

XMM-Newton, 1

NuSTAR, and many

Swift snapshots), starting in 2003 and until the most recent snapshot taken in 2021. The

Chandra, XMM-Newton, NuSTAR, and Swift telescopes have observed the galaxy repeatedly to monitor the plethora of X-ray sources, as well as the very interesting WR+BH system IC 10 X-1, the brightest source in the galaxy. Wang et al. [

15] first analyzed the combined spectra from single pointings of

XMM and

Chandra. They discovered a population of point sources (28 from

Chandra and 73 from

XMM-Newton) above the background. The sources were mostly concentrated within the optical outline of IC 10. The combined X-ray spectrum also showed physical properties and derived parameters characteristic of HMXBs.

Laycock et al. [

16] performed a complete census of all X-ray sources in the central region of IC 10 using

Chandra ACIS S3 data from 10 observations spanning 2003-2010 and found 110 X-ray point sources. Our work is a follow-up on the Laycock et al. [

16] effort and extends the existing catalog of XRBs using all available

Chandra observations and all CCDs that were turned on during observations. Since the full field of view of

Chandra was used, our catalog includes all sources detected in the IC 10 field. As a result, not all detected X-ray sources may be physically associated with the galaxy. Some sources are bound to be foreground stars or background AGN.

IC 10 has been observed many times by the

Chandra telescope in the period 2003-2021. The observations include a monitoring series of seven 15-ks exposures that were key to identifying 21 sources that were variable to a 3

level. There also exists a pair of deep

Chandra observations in 2006 that served as a reference data set. The first-ever 2003 data set [

15] (OBSID: 03953, ACIS-S in subarray mode) and the latest 2021 observation (OBSID: 26188) were also included in our data set, as they provided an expanded temporal baseline for X-ray source monitoring. The complete list of

Chandra observations used to create the final X-ray source catalog is summarized in

Table 1.

2.1. Data Reductions

The reduction and analysis of

Chandra data was conducted using exclusively CIAO (version 4.16), the dedicated software suite developed by the Chandra X-ray Center. CIAO can be installed via the Anaconda-based Python environment or the

ciao-install script, available at

https://cxc.cfa.harvard.edu/ciao/download/. Data were downloaded directly from the

Chandra archives using the command-line tool

download_chandra_obsid, which supports queries using source names or coordinates with a specified search radius. Once the raw data were obtained, they were reprocessed using the

chandra_repro command, which generates a new `repro’ directory containing cleaned event files. These event files were further corrected to the solar system barycenter using the

axbary tool.

Prior to source detection, exposure-corrected images in different energy bands were generated using the fluximage script, which also creates exposure and PSF maps. The main source detection for the current project relies on wavedetect, which was applied to images in broad (0.3-8 keV), soft (0.3-1.5 keV), medium (1.5-3 keV), and hard (3-8 keV) bands using wavelet scales of 1, 2, 4, 8, and 16 pixels, and a significance threshold of .

2.2. X-Ray Images and Source Detections

The main focus of this work was to create a comprehensive catalog of X-ray sources using all available observations (Obsid’s in

Table 1). Merged images for visual inspection were also created with Gaussian smoothing in all energy bands.

The source detection algorithm wavedetect was first run on each Obsid and energy band. This created a source list with many parameters, including position and position uncertainties, counts, PSF shape, detection significance, etc. Each source list was then boresight corrected using the coordinates of the brightest source (IC 10 X-1). These lists were then used for further cross-matching and the creation of the final catalog, as described below.

The wavedetect source lists were cross-matched within the energy bands first to create a single source list for each observation. Then, the source lists of all the observations were combined to create the final X-ray source catalog. The cross-matching was done using the classifytable tool in the command-line-based relational database software package Starbase.

The tool

classifytable groups together sources that lie within a distance of

which are then further filtered by the

error radius of each source. While matching the lists, the

wavedetect-provided error radius was not used to look for proximity, rather the 95% uncertainty radius was calculated using the Hong et al. [

17] prescription. Also, when considering which instance of a source (detected in multiple observations) to include in the final catalog, the one with the minimum value of

was chosen.

In the last step, our latest catalog, the previous version from Laycock et al. [

16], the Chandra source catalog (CSC 2.3), and the XMM source catalog (4XMM DR13) were all combined to generate the final unique source catalog that contains one entry for each X-ray source with its position and position uncertainty radius

(provided as supplementary material in Ref. [

18]).

3. Long-Term Lightcurves and Variability

Understanding the variability of these X-ray sources was a major motivation for this campaign. We used CIAO’s

srcflux tool to extract the count rates

R for each source in the X-ray catalog. This enabled us to create a long-term lightcurve for all 375 sources (provided as supplementary material in Ref. [

18]).

The variability of a source can be quantified by the flux variability ratio () and the variability range (). The rates in broad band are converted to relative variabilities () using .

These quantities were calculated for each individual source, and the strongly variable sources with

are listed in

Table 2. Some of these sources are discussed further in

Section 7.

4. Catalog of X-Ray Binaries

A young starburst galaxy like IC 10 is expected to have a stellar population dominated by HMXBs. Motivated by earlier works, we proceeded to match the final XRB catalog with the Massey et al. [

19] optical catalog of IC 10 stars. This photometric catalog has a limiting magnitude of

. Using their catalog of ACIS S3 observations, Laycock et al. [

16] found 42 optical counterparts to 110 X-ray sources.

We have increased the number of X-ray sources to 375 (compared to Laycock et al. [

16]), and we matched them again with the same optical catalog.

Starbase was used to look for optical counterparts within the total radius of

plus

added in quadrature (viz.

) to account for systematic uncertainties. We found 146 X-ray sources with optical counterparts, whereas the remaining 229 do not have counterparts down to

magnitude. The X-ray source IDs along with the properties of their optical counterparts are listed in

Table A1–

Table A4 of the Appendix.

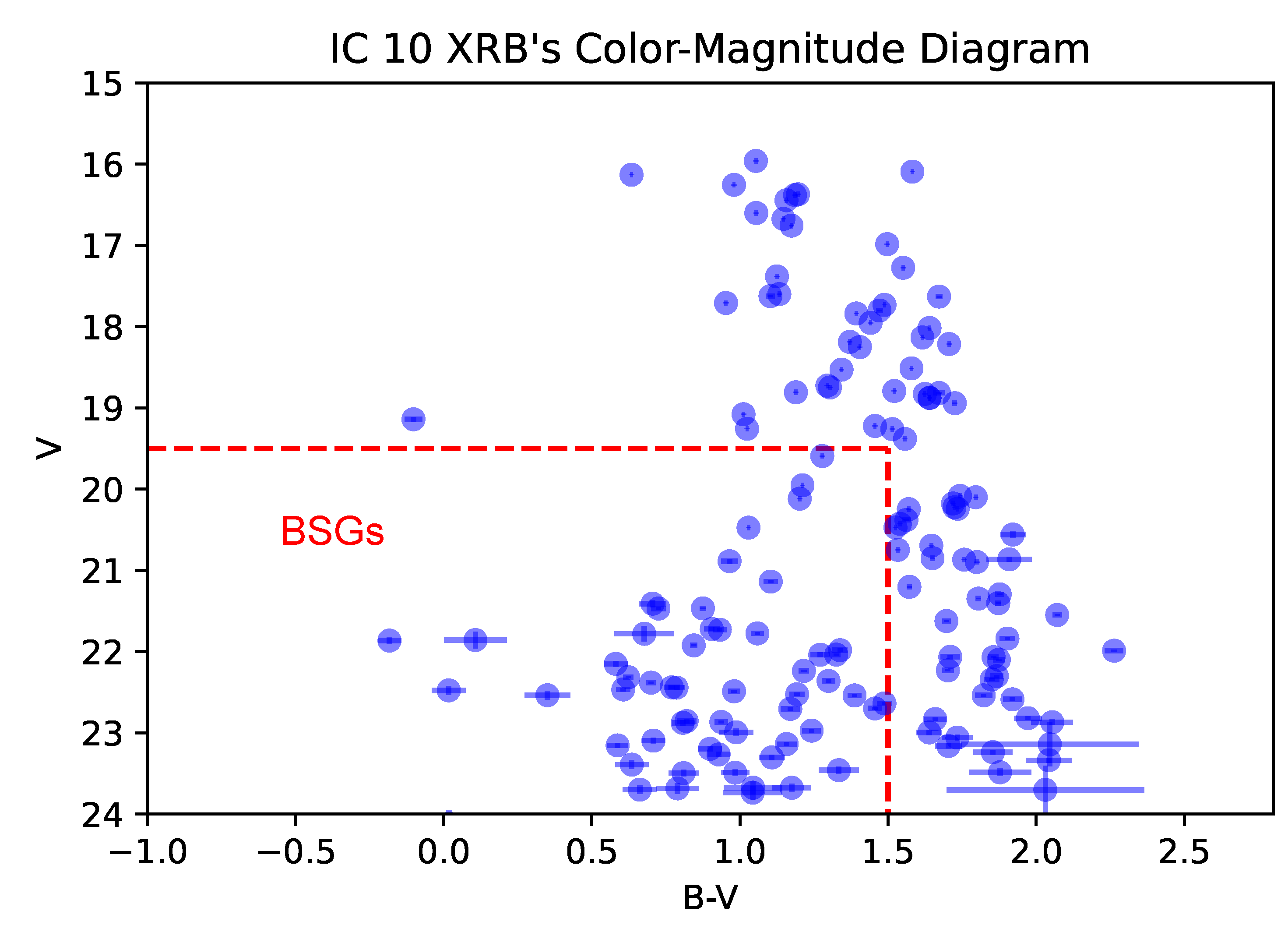

5. Blue Supergiant X-Ray Binaries

IC 10 is known to host many blue supergiants, Wolf-Rayet, and massive stars in general. Hence, in the next step, we investigated further these 146 binary systems using the characteristics of their optical counterparts. An important physical parameter in this endeavor is the optical source colors and the resulting color-magnitude diagram (

Figure 1). At the distance (660 kpc) and reddening (

,

, and

= 0.85) of IC 10 [

20], the main sequence beyond spectral type B0V is not visible in ground-based telescope images; but blue SGs (BSGs), the most luminous stars, are certainly visible. Foreground stars are also located in the field of IC 10 because the line of sight passes through the outermost region of the Galactic Plane. Fortunately, the main sequence (defined by the Galactic stars) is well separated from the BSG branch in color–magnitude space after correction due to reddening.

The limiting magnitude of the optical catalog also limits our search for HMXBs. Antoniou et al. [

13] predict that the HMXB counterparts are hotter than B3 and that the peak of the distribution is around B0. Hence, we are missing ∼50% of the population. Accounting for the reddening vector, we used a filter of

and

among the 146 optical counterparts, and we found 60 BSGs. These are listed in

Table A5–

Table A6 along with their X-ray source ID, coordinates,

V magnitude, and color information.

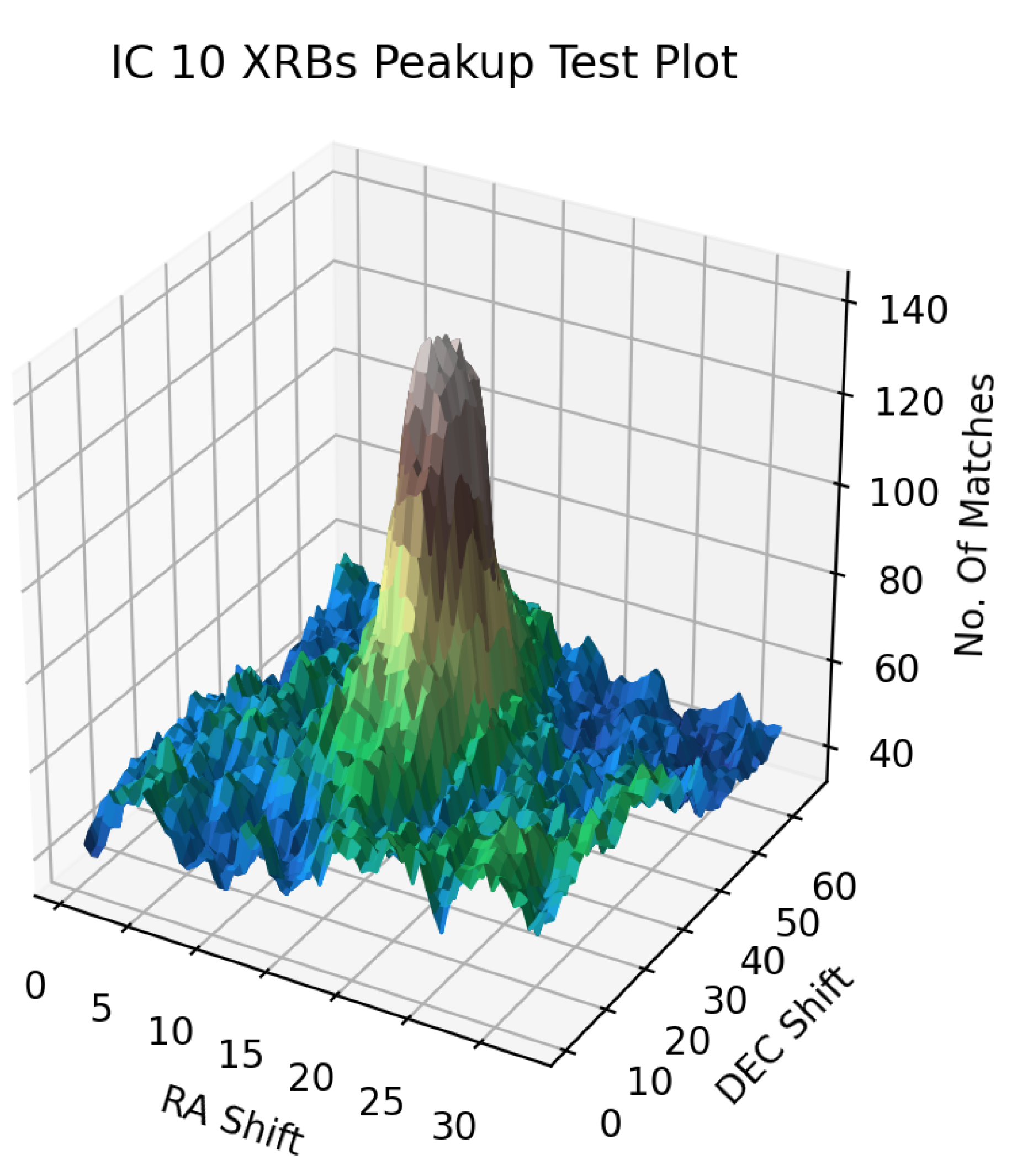

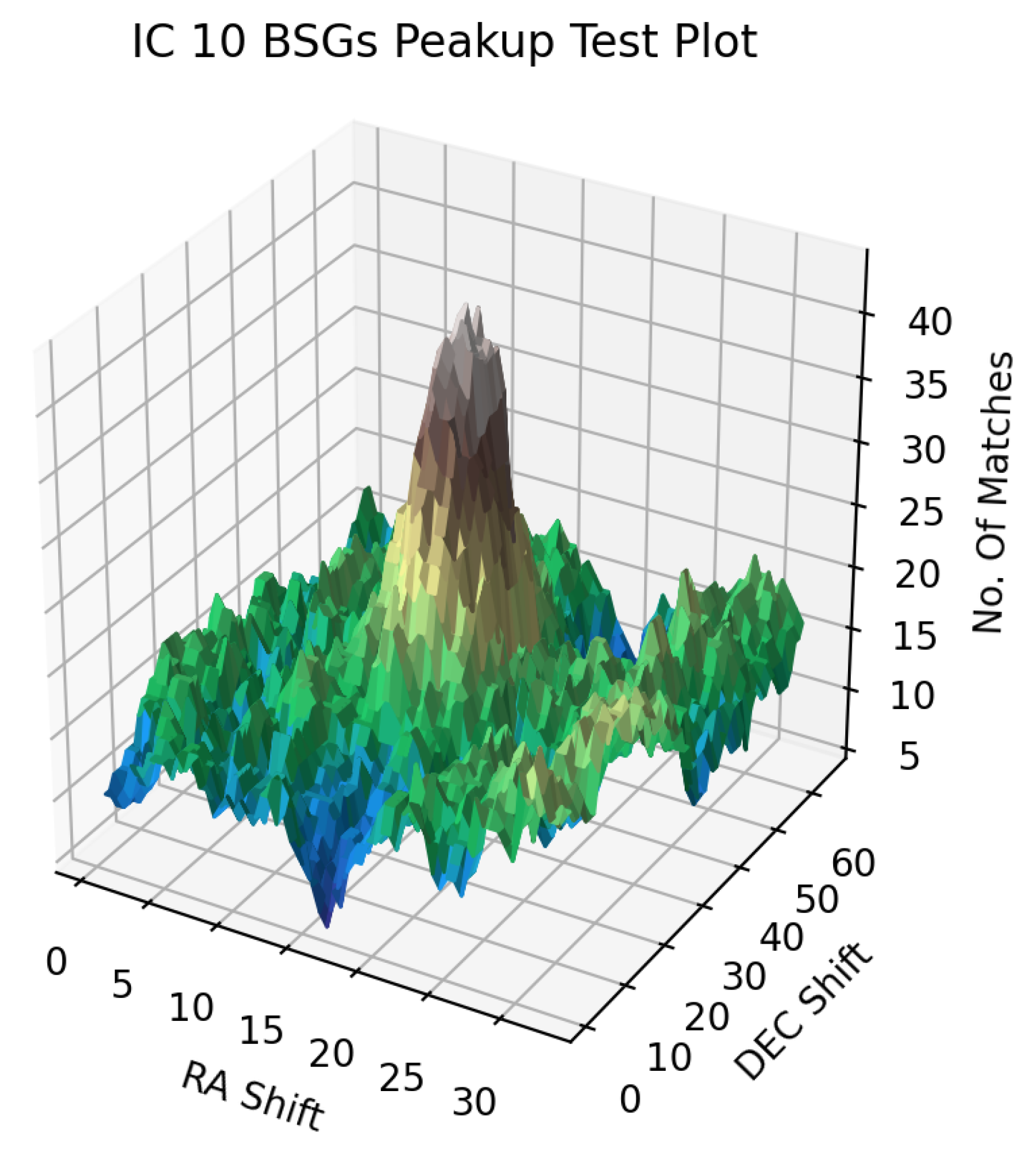

6. Peak-Up Test for Positional Accuracy

Studying X-ray binaries enables the identification and characterization of both the X-ray compact object and the optical stellar companion, as well as confirmation of their association. The identification of optical counterparts is a problem often encountered in astronomy. In general, when the objects under investigation are rare and both catalogs have good positional accuracy, astronomers consider that positional alignment implies physical association. This is a risky and unnecessary assumption given that there exists a quantitative approach, the so-called `peak-up test’ [

20]. This test can be applied to

Chandra observations of crowded fields, where there is a non-negligible chance of accidental alignment and a positional uncertainty for each X-ray source.

In the peak-up test, two catalogs are repeatedly matched with each other. In each iteration, a small offset in the coordinate system is applied, and the list of matching objects is recorded. The offsets are arranged in a regular grid spacing. The spacing is kept finer than the positional accuracy of the input catalogs, and the total offset extends to several times the radius of the largest error circles. The peak-up test code used in this project utilizes Starbase for catalog matching purposes, whereas Python is used for data analysis and visualization.

Figure 2.

Peak-up test result for XRB candidate counterparts in IC 10. The plot shows the number of matches between X-ray and optical sources as a function of small coordinate offsets applied across a regular grid. A clear peak is observed at central point (zero offset), indicating a statistically significant positional correlation between the optical sources and the X-ray detections. This provides strong evidence that a subset of the X-ray sources is physically associated with optical counterparts in IC 10. A detailed interpretation is given in

Section 6.

Figure 2.

Peak-up test result for XRB candidate counterparts in IC 10. The plot shows the number of matches between X-ray and optical sources as a function of small coordinate offsets applied across a regular grid. A clear peak is observed at central point (zero offset), indicating a statistically significant positional correlation between the optical sources and the X-ray detections. This provides strong evidence that a subset of the X-ray sources is physically associated with optical counterparts in IC 10. A detailed interpretation is given in

Section 6.

Figure 3.

Peak-up test result for BSG candidate counterparts in IC 10. The plot shows the number of matches between X-ray and optical sources as a function of small coordinate offsets applied across a regular grid. A clear peak is observed at the central location (zero offset), indicating a statistically significant positional correlation between the BSG optical sources and the X-ray detections. This provides strong evidence that a subset of the X-ray sources is physically associated with BSG counterparts in IC 10. A detailed interpretation is given in

Section 6.

Figure 3.

Peak-up test result for BSG candidate counterparts in IC 10. The plot shows the number of matches between X-ray and optical sources as a function of small coordinate offsets applied across a regular grid. A clear peak is observed at the central location (zero offset), indicating a statistically significant positional correlation between the BSG optical sources and the X-ray detections. This provides strong evidence that a subset of the X-ray sources is physically associated with BSG counterparts in IC 10. A detailed interpretation is given in

Section 6.

In this test, if real matches () exceed the median () number expected by chance, then a peak is observed in the 2D mapping of the two catalogs. Hence, the name peak-up test. The significance of the peak is then calculated using the standard deviation () of the distribution of chance alignments after removing the area within the maximum matching radius of the zero-offset position. The significance of the positional correlation peak is then expressed as .

We matched the final source catalog with the Massey et al. [

19] optical catalog, adopting a matching radius of

arcsec for each source. The result was

, and

.

Following the assessment of Massey et al. [

19] who divided the color-magnitude space into foreground main sequence stars and IC 10 BSG stars, we also filtered the XRB catalog to match only BSG candidates obeying the criteria that

and

. We obtained

, and

. The high significance values in both cases confirm that the positional correlation is not due to chance, but rather due to physical association, reinforcing thus the expectation that many of the X-ray sources in IC 10 have massive stellar counterparts.

7. Discussion

IC 10 has been found to harbor a dense population of X-ray sources. The identification of individual X-ray sources in IC 10 is not an easy task due to its low galactic latitude position (

). Not only does the Galactic H

i column density interfere, but there is also interference from molecular gas in the Galaxy and the gas inside IC 10 itself [

15]. The presence of many more point sources, even though some of them are scattered around the edge of the galaxy, is one of the noteworthy additions made in this latest version of the IC 10 source catalog. Their spatial distribution offers important hints about the underlying stellar populations and the areas with higher star formation activity, although certain unrelated objects (AGN, SNRs, Galactic sources) are bound to be superposed on to the IC 10 field.

The new catalog strives to present only XRB and BSG-XRB candidates, and filtering the list by color-magnitude may offer some assurance at least for BSGs. On the other hand, by utilizing the entire ACIS field of view for source detection, we have covered a region larger than the optical extent of IC 10. While this wide coverage enhances the completeness of the X-ray catalog, it also introduces certain X-ray sources not physically associated with IC 10. The actual IC 10 members will need to be confirmed by follow-up spectroscopic measurements of the Doppler shifts in nebular lines.

One of the main motivations was to look for variability in transient X-ray sources. IC 10 X-2 (Source 46) is a well-known transient (SFXT), whereas IC 10 X-1 (Source 20) is the brightest known persistent source in the galaxy. Laycock et al. [

16] calculated the variability of the first 110 X-ray sources and discussed some of them in detail. Here, we turn our attention to the new variable sources 246, 268, and 314 that have optical counterparts (although only 314 can be unambiguously classified as a BSG-HMXB):

Source 246 (RA: 5.11538

∘, DEC: 59.1045

∘) is a persistent source (4/4 detections) with relative variability

. It has an optical counterpart in the Massey et al. [

19] catalog with

and

. Its brightness and color information suggest that it is most likely a Galactic source.

Source 268 (RA: 5.19171

∘, DEC: 59.0732

∘) is a persistent source (3/3 detections) with relative variability

. It has an optical counterpart in the Massey et al. [

19] catalog with

and

. Its brightness and color information suggest that it may be either a Galactic source or an IC 10 yellow SG.

Source 314 (RA: 5.30692

∘, DEC: 59.3676

∘) is a persistent source (5/5 detections) with relative variability

. It has an optical counterpart in the Massey et al. [

19] catalog with

and

. Its brightness and color information suggest a strong contender for an IC 10 BSG-HMXB source.

7.1. Characteristics of BSG-HMXB Systems

The BSG X-ray sources that we have detected in our survey are accreting compact object binaries. BSGs can emit X-rays in isolation [

21], as well as in compact object binaries; but, at the distance of IC 10 (660 kpc), the observed X-ray fluxes can only be explained by accretion onto a compact object. The X-ray/optical (distance-independent) luminosity relation was calculated for all sources with counterparts, viz.

using the

V magnitudes from the Massey et al. [

19] catalog and the measured X-ray fluxes (

) in the broad band (0.3-8 keV). Laycock et al. [

20] have shown that the BSGs have systematically higher

values, and the Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test showed a statistically significant offset between the BSGs and other types of counterparts.

BSG sources have also shown X-ray variability in the 2010

Chandra monitoring data. Variability ranges from a factor of ∼150 (for IC 10 X-2) to a few. Massey et al. [

19] performed a narrowband photometric survey, particularly to identify luminous blue variable (LBV) candidates, but only IC 10 X-2 was found to be in that catalog. This might be because of the selection criteria that were based on M31. The authors showed that this filtering excluded 17 known WR stars in the field. A new relaxed emission line catalog can identify more of the X-ray counterparts in IC 10.

7.2. Population Estimates from the Census of BSG-XRBs

The IC 10 BSGs can be used as a tracer to identify the underlying population of double-degenerate systems. If we assume that the

(from the peak-up test) BSG-XRB sources in IC 10 are all HMXBs, then their production rate and the number of precursor double-degenerate binaries can be estimated along the lines of Laycock et al. [

20].

The duty cycle during which the LBVs are donating mass to their compact companions is

, where

Myr is the duration of the starburst and

is the mean lifetime of the LBVs, taken to be

= 0.4 Myr for a typical LBV mass of

[

22,

23,

24]. For this duty cycle, IC 10 must have produced

precursor double-degenerate binaries during the course of the starburst.

From the above estimates, we determine a typical value of

and an upper limit of

progenitors. This new upper limit is nearly

larger than the value previously determined by Laycock et al. [

20] for IC 10.

8. Summary and Conclusions

8.1. Summary

From the very first study by Wang et al. [

15], it was evident that IC 10 hosts quite a few X-ray sources. Laycock et al. [

16] followed up with an extensive study of the core region of IC 10 using

Chandra monitoring data. In this work, we have expanded both the field of view and the temporal baseline of the search by adding a new 2021 observation and by analyzing data from all CCDs turned on during each observation.

We have used

wavedetect on soft, medium, hard, and broad band images for source detection. A total of 375 X-ray point sources were detected in this search. The variability of these sources has been classified using the individual observation source list. In the final comprehensive catalog, the

Chandra and

XMM source catalogs have also been incorporated, and the first 110 sources from Laycock et al. [

16] have been kept intact to ensure a smooth extension of the original source catalog.

The new point source catalog was matched with the Massey et al. [

19] optical catalog to look for the X-ray binary population. We found 146 XRB sources with an optical counterpart down to the limiting

V magnitude of 23.8. These XRB sources were subsequently filtered using the optical criteria

and

[

19], resulting in 60 BSG optical companions.

8.2. Conclusions

We can already see that the new HMXBs reported here are not of the same population as those found in the Magellanic Clouds. The projected X-ray binary population is affected by the very young age of the underlying stellar population and the enhanced formation of massive stars and stellar remnants reported by other authors [

19,

25]. The main differences concern the presence or absence of Be-HMXBs:

SMC Be-HMXBs: At least 100 known or candidate HMXBs, the bulk of which are Be+NS systems and all of which have counterparts earlier than B3, are found in the SMC with its episodic starburst history [

26]. Negueruela [

27] originally suggested that the Be-HMXB restricted spectral type range is an evolutionary hallmark. The work of Antoniou et al. [

13], which demonstrated that the SMC Be-HMXBs are connected with separate populations of ages 40–70 Myr, lends weight to this theory. (In NGC 300 and NGC 2403, Williams et al. [

28] discovered a comparable age association for HMXBs.)

IC 10 BSG-XRBs and WR stars: Thus, we expected to see entirely different HMXB species in IC 10 because of the young age of its starburst. With the Be phenomenon not yet prevalent in IC 10, there should be other mass donors with stronger winds and/or lower orbital separations that provide the necessary mass-transfer rates and accretion-powered X-ray emissions. The most obvious candidates are BSGs and WR stars; although only one X-ray source (IC 10 X-1) matches the WR catalog of Crowther et al. [

29]. On the other hand, weak-lined WR stars may actually exist in IC 10, but they are not recognized yet.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, Investigation, and Methodology, S.B., S.L., B.B. and D.C.; Conceptualization and Project administration, S.L. and D.C.; Resources and Supervision, S.L. and B.B.; Writing – original draft, S.B.; Writing – review & editing, S.L., B.B and D.C.

Funding

This research project was facilitated in part by the following funding agencies and programs: NSF-AAG, grant 2109004; NASA Astrophysics Data Analysis Program (ADAP), grants NNX14AF77G and 80NSSC18K0430; and the Lowell Center for Space Science and Technology (LoCSST) of the University of Massachusetts Lowell.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACIS |

Advanced CCD Imaging Spectrometer |

| AGN |

Active Galactic Nuclei |

| BCD |

Blue Compact Dwarf |

| BH |

Black Hole |

| BSG |

Blue SuperGiant |

| CCD |

Charge-Coupled Device |

| CIAO |

Chandra Interactive Analysis of Observations |

| CSC |

Chandra Source Catalog |

| DEC |

DEClination |

| FOV |

Field Of View |

| HMXB |

High-Mass X-ray Binary |

| LBV |

Luminous Blue Variable |

| LMC |

Large Magellanic Cloud |

| NS |

Neutron Star |

| PSF |

Point Spread Function |

| RA |

Right Ascension |

| SFXT |

Supergiant Fast X-ray Transient |

| SG |

SuperGiant |

| SMC |

Small Magellanic Cloud |

| SNR |

SuperNova Remnant |

| WR |

Wolf-Rayet |

| XRB |

X-Ray Binary |

Appendix A

Additionally, the full point source catalog and the long-term lightcurves of all detected X-ray sources can be downloaded from the link

https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/Y3PUOO (see also Ref. [

18]).

Table A1.

IC 10 X-ray Binary Candidates

Table A1.

IC 10 X-ray Binary Candidates

| Source # |

RA |

DEC |

|

|

| 1 |

5.03621 |

59.2279 |

22.384 |

0.7 |

| 3 |

5.06636 |

59.2399 |

20.247 |

1.57 |

| 4 |

5.02508 |

59.2402 |

22.588 |

1.92 |

| 7 |

5.11086 |

59.2487 |

16.985 |

1.497 |

| 8 |

5.05286 |

59.2504 |

22.974 |

1.242 |

| 13 |

4.99465 |

59.2576 |

20.473 |

1.525 |

| 15 |

5.03663 |

59.2624 |

16.758 |

1.174 |

| 17 |

5.14415 |

59.2659 |

16.381 |

1.186 |

| 17 |

5.14415 |

59.2659 |

16.372 |

1.196 |

| 20 |

5.12132 |

59.281 |

22.478 |

0.017 |

| 20 |

5.12132 |

59.281 |

21.722 |

0.905 |

| 21 |

5.03429 |

59.2818 |

23.486 |

1.878 |

| 25 |

5.10117 |

59.2892 |

22.856 |

0.82 |

| 25 |

5.10117 |

59.2892 |

22.441 |

0.77 |

| 26 |

4.97811 |

59.2894 |

21.983 |

1.338 |

| 26 |

4.97811 |

59.2894 |

22.04 |

1.271 |

| 27 |

5.04657 |

59.2908 |

21.924 |

0.844 |

| 28 |

5.19383 |

59.292 |

18.793 |

1.521 |

| 29 |

5.0382 |

59.2939 |

21.777 |

1.059 |

| 29 |

5.0382 |

59.2939 |

21.732 |

0.932 |

| 32 |

5.04812 |

59.304 |

20.428 |

1.54 |

| 38 |

5.03305 |

59.3124 |

22.344 |

1.85 |

| 39 |

5.10836 |

59.3125 |

18.878 |

1.64 |

| 46 |

5.08723 |

59.2997 |

19.954 |

1.211 |

| 48 |

5.17812 |

59.3144 |

17.954 |

1.441 |

| 50 |

5.19656 |

59.3267 |

22.539 |

1.823 |

| 52 |

5.1391 |

59.3596 |

17.277 |

1.551 |

| 53 |

5.05732 |

59.3766 |

21.404 |

1.872 |

| 61 |

5.13621 |

59.2626 |

21.296 |

1.877 |

| 65 |

5.08036 |

59.3043 |

23.685 |

0.789 |

| 65 |

5.08036 |

59.3043 |

23.737 |

1.043 |

| 66 |

4.92791 |

59.3347 |

17.625 |

1.103 |

| 66 |

4.92791 |

59.3347 |

17.6 |

1.133 |

| 76 |

5.1187 |

59.3358 |

17.382 |

1.125 |

| 77 |

5.0722 |

59.2972 |

23.059 |

1.734 |

| 78 |

5.09598 |

59.2982 |

21.411 |

0.705 |

| 78 |

5.09598 |

59.2982 |

22.152 |

0.581 |

| 78 |

5.09598 |

59.2982 |

22.445 |

0.786 |

| 86 |

5.15428 |

59.3134 |

18.727 |

1.295 |

| 87 |

5.03887 |

59.3919 |

18.75 |

1.304 |

| 90 |

5.11847 |

59.3399 |

21.348 |

1.805 |

Table A2.

IC 10 X-ray Binary Candidates (continued)

Table A2.

IC 10 X-ray Binary Candidates (continued)

| Source # |

RA |

DEC |

|

|

| 91 |

4.9653 |

59.2619 |

20.749 |

1.533 |

| 92 |

4.99881 |

59.3009 |

21.471 |

0.725 |

| 96 |

5.05331 |

59.2723 |

22.038 |

1.325 |

| 98 |

5.0508 |

59.2844 |

23.142 |

2.046 |

| 98 |

5.0508 |

59.2844 |

22.101 |

1.874 |

| 98 |

5.0508 |

59.2844 |

22.315 |

0.623 |

| 98 |

5.0508 |

59.2844 |

23.155 |

0.587 |

| 100 |

5.01024 |

59.3015 |

23.097 |

0.708 |

| 101 |

5.11942 |

59.3493 |

20.697 |

1.646 |

| 106 |

5.04294 |

59.317 |

21.99 |

2.263 |

| 107 |

5.20919 |

59.2572 |

20.083 |

1.743 |

| 133 |

4.79151 |

59.2074 |

20.865 |

1.909 |

| 139 |

4.82537 |

59.2088 |

16.256 |

0.98 |

| 140 |

4.82668 |

59.2352 |

22.87 |

2.054 |

| 143 |

4.83621 |

59.211 |

18.809 |

1.189 |

| 144 |

4.84389 |

59.2613 |

21.624 |

1.697 |

| 145 |

4.85256 |

59.3573 |

19.141 |

−0.102 |

| 145 |

4.85256 |

59.3573 |

17.631 |

1.672 |

| 145 |

4.85256 |

59.3573 |

17.802 |

1.471 |

| 147 |

4.85651 |

59.2385 |

18.134 |

1.616 |

| 148 |

4.85799 |

59.1303 |

21.139 |

1.104 |

| 148 |

4.85799 |

59.1303 |

23.675 |

1.044 |

| 150 |

4.86137 |

59.1846 |

16.674 |

1.147 |

| 151 |

4.86395 |

59.2373 |

18.829 |

1.624 |

| 153 |

4.86454 |

59.408 |

23.702 |

2.031 |

| 157 |

4.88205 |

59.2357 |

23.677 |

1.175 |

| 167 |

4.91239 |

59.3839 |

16.602 |

1.055 |

| 168 |

4.91505 |

59.1706 |

23.198 |

0.899 |

| 169 |

4.91716 |

59.462 |

18.189 |

1.371 |

| 173 |

4.92518 |

59.0735 |

21.55 |

2.071 |

| 176 |

4.93644 |

59.2304 |

16.131 |

0.634 |

| 176 |

4.93644 |

59.2304 |

20.183 |

−4.129 |

| 179 |

4.94619 |

59.2133 |

15.961 |

1.054 |

| 180 |

4.95156 |

59.332 |

22.701 |

1.456 |

| 181 |

4.95463 |

59.106 |

22.867 |

0.937 |

| 182 |

4.95562 |

59.2261 |

18.252 |

1.405 |

| 183 |

4.96093 |

59.3249 |

21.865 |

−0.183 |

| 183 |

4.96093 |

59.3249 |

20.888 |

0.965 |

| 183 |

4.96093 |

59.3249 |

20.38 |

1.562 |

| 184 |

4.96149 |

59.0785 |

23.496 |

0.81 |

| 186 |

4.96547 |

59.1423 |

20.475 |

1.029 |

| 188 |

4.96792 |

59.1179 |

22.302 |

1.867 |

Table A3.

IC 10 X-ray Binary Candidates (continued)

Table A3.

IC 10 X-ray Binary Candidates (continued)

| Source # |

RA |

DEC |

|

|

| 197 |

4.98966 |

59.2978 |

22.832 |

1.659 |

| 198 |

4.99304 |

59.141 |

16.445 |

1.157 |

| 199 |

4.99389 |

59.12 |

22.638 |

1.488 |

| 201 |

4.99573 |

59.1517 |

22.065 |

1.71 |

| 201 |

4.99573 |

59.1517 |

19.079 |

1.012 |

| 205 |

5.0055 |

59.373 |

22.526 |

1.193 |

| 213 |

5.0181 |

59.3976 |

23.163 |

1.704 |

| 214 |

5.01921 |

59.3124 |

21.204 |

1.572 |

| 216 |

5.03054 |

59.3257 |

22.878 |

0.807 |

| 217 |

5.03137 |

59.2137 |

22.361 |

1.299 |

| 222 |

5.05005 |

59.3885 |

19.262 |

1.514 |

| 223 |

5.05384 |

59.4846 |

22.489 |

0.98 |

| 227 |

5.06583 |

59.3197 |

19.593 |

1.278 |

| 228 |

5.06588 |

59.5057 |

23.303 |

1.108 |

| 230 |

5.07889 |

59.1956 |

20.225 |

1.724 |

| 232 |

5.07959 |

59.0874 |

22.996 |

1.639 |

| 233 |

5.0877 |

59.1783 |

17.71 |

0.953 |

| 234 |

5.0927 |

59.3465 |

19.382 |

1.557 |

| 237 |

5.09626 |

59.1371 |

22.238 |

1.216 |

| 238 |

5.0978 |

59.3075 |

22.467 |

0.606 |

| 238 |

5.0978 |

59.3075 |

24.119 |

0.018 |

| 238 |

5.0978 |

59.3075 |

23.392 |

0.635 |

| 241 |

5.10252 |

59.2938 |

21.782 |

0.677 |

| 241 |

5.10252 |

59.2938 |

21.859 |

0.107 |

| 241 |

5.10252 |

59.2938 |

23.46 |

1.334 |

| 241 |

5.10252 |

59.2938 |

22.538 |

0.35 |

| 242 |

5.10649 |

59.2974 |

24.59 |

0.662 |

| 244 |

5.10888 |

59.3125 |

18.878 |

1.64 |

| 246 |

5.11538 |

59.1045 |

18.215 |

1.706 |

| 250 |

5.12773 |

59.3248 |

20.869 |

1.757 |

| 252 |

5.1407 |

59.1761 |

16.093 |

1.582 |

| 254 |

5.14407 |

59.1872 |

20.1 |

1.796 |

| 261 |

5.16485 |

59.2477 |

21.84 |

1.903 |

| 262 |

5.16504 |

59.2369 |

20.243 |

1.735 |

| 265 |

5.18 |

59.1264 |

23.491 |

0.984 |

| 267 |

5.19123 |

59.2721 |

20.178 |

1.719 |

| 268 |

5.19171 |

59.0732 |

20.56 |

1.921 |

| 272 |

5.19677 |

59.2228 |

17.733 |

1.488 |

| 275 |

5.20739 |

59.2083 |

20.898 |

1.8 |

| 281 |

5.22531 |

59.427 |

18.018 |

1.64 |

Table A4.

IC 10 X-ray Binary Candidates (continued)

Table A4.

IC 10 X-ray Binary Candidates (continued)

| Source # |

RA |

DEC |

|

|

| 293 |

5.24541 |

59.3558 |

17.839 |

1.393 |

| 295 |

5.24921 |

59.2232 |

23.7 |

0.662 |

| 296 |

5.25044 |

59.1017 |

23.339 |

2.043 |

| 300 |

5.26496 |

59.3152 |

19.258 |

1.024 |

| 300 |

5.26496 |

59.3152 |

23.238 |

1.854 |

| 301 |

5.26571 |

59.3451 |

22.54 |

1.387 |

| 303 |

5.26806 |

59.107 |

18.514 |

1.579 |

| 307 |

5.28589 |

59.141 |

18.531 |

1.343 |

| 308 |

5.28685 |

59.1925 |

23.139 |

1.158 |

| 314 |

5.30692 |

59.3676 |

22.706 |

1.17 |

| 316 |

5.31863 |

59.3442 |

22.232 |

1.702 |

| 318 |

5.32064 |

59.373 |

19.224 |

1.456 |

| 323 |

5.3277 |

59.4037 |

22.069 |

1.856 |

| 324 |

5.33041 |

59.4016 |

20.119 |

1.202 |

| 326 |

5.33145 |

59.0841 |

20.851 |

1.65 |

| 331 |

5.3445 |

59.3494 |

23.267 |

0.928 |

| 333 |

5.35647 |

59.3179 |

18.943 |

1.725 |

| 335 |

5.36187 |

59.4023 |

22.821 |

1.972 |

| 343 |

5.38665 |

59.2442 |

21.469 |

0.875 |

| 346 |

5.40615 |

59.3394 |

22.994 |

0.987 |

| 348 |

5.41238 |

59.3784 |

18.817 |

1.672 |

Table A5.

IC 10 Blue Supergiant X-ray Binary Candidates

Table A5.

IC 10 Blue Supergiant X-ray Binary Candidates

| Source # |

RA |

DEC |

|

|

| 1 |

5.03621 |

59.2279 |

22.384 |

0.7 |

| 8 |

5.05286 |

59.2504 |

22.974 |

1.242 |

| 20 |

5.12132 |

59.281 |

22.478 |

0.017 |

| 20 |

5.12132 |

59.281 |

21.722 |

0.905 |

| 25 |

5.10117 |

59.2892 |

22.441 |

0.77 |

| 25 |

5.10117 |

59.2892 |

22.856 |

0.82 |

| 26 |

4.97811 |

59.2894 |

21.983 |

1.338 |

| 26 |

4.97811 |

59.2894 |

22.04 |

1.271 |

| 27 |

5.04657 |

59.2908 |

21.924 |

0.844 |

| 29 |

5.0382 |

59.2939 |

21.777 |

1.059 |

| 29 |

5.0382 |

59.2939 |

21.732 |

0.932 |

| 46 |

5.08723 |

59.2997 |

19.954 |

1.211 |

| 65 |

5.08036 |

59.3043 |

23.737 |

1.043 |

| 65 |

5.08036 |

59.3043 |

23.685 |

0.789 |

| 78 |

5.09598 |

59.2982 |

21.411 |

0.705 |

| 78 |

5.09598 |

59.2982 |

22.152 |

0.581 |

| 78 |

5.09598 |

59.2982 |

22.445 |

0.786 |

| 92 |

4.99881 |

59.3009 |

21.471 |

0.725 |

| 96 |

5.05331 |

59.2723 |

22.038 |

1.325 |

| 98 |

5.0508 |

59.2844 |

22.315 |

0.623 |

| 98 |

5.0508 |

59.2844 |

23.155 |

0.587 |

| 100 |

5.01024 |

59.3015 |

23.097 |

0.708 |

| 145 |

4.85256 |

59.3573 |

19.141 |

−0.102 |

| 148 |

4.85799 |

59.1303 |

21.139 |

1.104 |

| 148 |

4.85799 |

59.1303 |

23.675 |

1.044 |

| 157 |

4.88205 |

59.2357 |

23.677 |

1.175 |

| 168 |

4.91505 |

59.1706 |

23.198 |

0.899 |

| 176 |

4.93644 |

59.2304 |

20.183 |

−4.129 |

| 180 |

4.95156 |

59.332 |

22.701 |

1.456 |

| 181 |

4.95463 |

59.106 |

22.867 |

0.937 |

| 183 |

4.96093 |

59.3249 |

21.865 |

−0.183 |

| 183 |

4.96093 |

59.3249 |

20.888 |

0.965 |

| 184 |

4.96149 |

59.0785 |

23.496 |

0.81 |

| 186 |

4.96547 |

59.1423 |

20.475 |

1.029 |

| 199 |

4.99389 |

59.12 |

22.638 |

1.488 |

| 201 |

4.99573 |

59.1517 |

19.079 |

1.012 |

| 205 |

5.0055 |

59.373 |

22.526 |

1.193 |

| 216 |

5.03054 |

59.3257 |

22.878 |

0.807 |

| 217 |

5.03137 |

59.2137 |

22.361 |

1.299 |

| 223 |

5.05384 |

59.4846 |

22.489 |

0.98 |

| 227 |

5.06583 |

59.3197 |

19.593 |

1.278 |

| 228 |

5.06588 |

59.5057 |

23.303 |

1.108 |

| 237 |

5.09626 |

59.1371 |

22.238 |

1.216 |

| 238 |

5.0978 |

59.3075 |

23.392 |

0.635 |

| 238 |

5.0978 |

59.3075 |

24.119 |

0.018 |

| 238 |

5.0978 |

59.3075 |

22.467 |

0.606 |

Table A6.

IC 10 Blue Supergiant X-ray Binary Candidates (continued)

Table A6.

IC 10 Blue Supergiant X-ray Binary Candidates (continued)

| Source # |

RA |

DEC |

|

|

| 241 |

5.10252 |

59.2938 |

21.782 |

0.677 |

| 241 |

5.10252 |

59.2938 |

21.859 |

0.107 |

| 241 |

5.10252 |

59.2938 |

23.46 |

1.334 |

| 241 |

5.10252 |

59.2938 |

22.538 |

0.35 |

| 242 |

5.10649 |

59.2974 |

24.59 |

0.662 |

| 265 |

5.18 |

59.1264 |

23.491 |

0.984 |

| 295 |

5.24921 |

59.2232 |

23.7 |

0.662 |

| 300 |

5.26496 |

59.3152 |

19.258 |

1.024 |

| 301 |

5.26571 |

59.3451 |

22.54 |

1.387 |

| 308 |

5.28685 |

59.1925 |

23.139 |

1.158 |

| 314 |

5.30692 |

59.3676 |

22.706 |

1.17 |

| 318 |

5.32064 |

59.373 |

19.224 |

1.456 |

| 324 |

5.33041 |

59.4016 |

20.119 |

1.202 |

| 331 |

5.3445 |

59.3494 |

23.267 |

0.928 |

| 343 |

5.38665 |

59.2442 |

21.469 |

0.875 |

| 346 |

5.40615 |

59.3394 |

22.994 |

0.987 |

References

- Mayall, N. An extra-galactic object 3 from the plane of the galaxy. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 1935, 47, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubble, E. The luminosity function of nebulae. I. The luminosity function of resolved nebulae as indicated by their brightest stars. Astrophysical Journal, vol. 84, p. 158 1936, 84, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, D.R.; Teodorescu, A.M.; Alves-Brito, A.; Méndez, R.H.; Magrini, L. A kinematic study of planetary nebulae in the dwarf irregular galaxy IC10. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2012, 425, 2557–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanna, N.; Bono, G.; Stetson, P.; Monelli, M.; Pietrinferni, A.; Drozdovsky, I.; Caputo, F.; Cassisi, S.; Gennaro, M.; Moroni, P.P.; et al. On the distance and reddening of the starburst galaxy IC 10. The Astrophysical Journal 2008, 688, L69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, P.; Armandroff, T.E.; Conti, P.S. IC 10-A "poor cousin" rich in Wolf-Rayet stars. Astronomical Journal 1992, 103, 1159–1165 and 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, P.; Armandroff, T.E. The Massive Star Content, Reddening, and Distance of the Nearby Irregular Galaxy IC 10. Astronomical Journal v. 109, p. 2470 1995, 109, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, P.; Lee, M.G. The H II regions of IC 10. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 1990, 102, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, D.A.; Gallagher, J.S. Star-forming properties and histories of dwarf irregular galaxies-Down but not out. Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series (ISSN 0067-0049), vol. 58, Aug. 1985, p. 533-560. 1985, 58, 533–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, P.; Armandroff, T.E.; Pyke, R.; Patel, K.; Wilson, C.D. Hot, luminous stars in selected regions of NGC 6822, M31, and M33. Astronomical Journal v. 110, p. 2715 1995, 110, 2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcots, E.M.; Miller, B.W. The kinematics and distribution of HI in IC 10. The Astronomical Journal 1998, 116, 2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richer, M.; Bullejos, A.; Borissova, J.; McCall, M.L.; Lee, H.; Kurtev, R.; Georgiev, L.; Kingsburgh, R.; Ross, R.; Rosado, M. IC 10: More evidence that it is a blue compact dwarf. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2001, 370, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidever, D.L.; Ashley, T.; Slater, C.T.; Ott, J.; Johnson, M.; Bell, E.F.; Stanimirović, S.; Putman, M.; Majewski, S.R.; Simpson, C.E.; et al. Evidence for an interaction in the nearest starbursting dwarf irregular galaxy IC 10. The Astrophysical Journal Letters 2013, 779, L15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, V.; Zezas, A.; Hatzidimitriou, D.; Kalogera, V. Star formation history and X-ray binary populations: the case of the Small Magellanic Cloud. The Astrophysical Journal Letters 2010, 716, L140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, B.A.; Lazarus, R.; Thoresen, M.; Laycock, S.; Bhattacharya, S. The X-ray Variability and Luminosity Function of High Mass X-ray Binaries in the Dwarf Starburst Galaxy IC 10. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.02876 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.D.; Whitaker, K.E.; Williams, R. An XMM-Newton and Chandra study of the starburst galaxy IC 10. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2005, 362, 1065–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laycock, S.; Cappallo, R.; Williams, B.F.; Prestwich, A.; Binder, B.; Christodoulou, D.M. The X-Ray Binary Population of the Nearby Dwarf Starburst Galaxy IC 10: Variable and Transient X-Ray Sources. The Astrophysical Journal 2017, 836, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; van den Berg, M.; Schlegel, E.M.; Grindlay, J.E.; Koenig, X.; Laycock, S.; Zhao, P. X-ray processing of champlane fields: Methods and initial results for selected anti-galactic center fields. The Astrophysical Journal 2005, 635, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S. Replication Data for: Chandra Observations of the X-ray binary population in IC 10 2025. [CrossRef]

- Massey, P.; McNeill, R.T.; Olsen, K.; Hodge, P.W.; Blaha, C.; Jacoby, G.H.; Smith, R.; Strong, S.B. A survey of local group galaxies currently forming stars. III. A search for luminous blue variables and other Hα emission-line stars. The Astronomical Journal 2007, 134, 2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laycock, S.G.; Christodoulou, D.M.; Williams, B.F.; Binder, B.; Prestwich, A. Blue Supergiant X-Ray Binaries in the Nearby Dwarf Galaxy IC 10. The Astrophysical Journal 2017, 836, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghöfer, T.; Schmitt, J.; Danner, R.; Cassinelli, J. X-ray properties of bright OB-type stars detected in the ROSAT all-sky survey. Astronomy and Astrophysics, v. 322, p. 167-174 1997, 322, 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Maeder, A.; Meynet, G. Stellar evolution with rotation. VII.-Low metallicity models and the blue to red supergiant ratio in the SMC. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2001, 373, 555–571. [Google Scholar]

- Fragos, T.; Linden, T.; Kalogera, V.; Sklias, P. On the formation of ultraluminous x-ray sources with neutron star accretors: The case of m82 x-2. The Astrophysical Journal Letters 2015, 802, L5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, P.; Neugent, K.F.; Smart, B.M. A spectroscopic survey of massive stars in M31 and M33. The Astronomical Journal 2016, 152, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, F.E.; Brandt, W.N. Chandra and Hubble space telescope confirmation of the luminous and variable X-ray source ic 10 X-1 as a possible Wolf-Rayet, black hole binary. ApJ 2004, 601, L67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, V.; Coe, M.; Negueruela, I.; Schurch, M.; McGowan, K. Spectral distribution of Be/X-ray binaries in the Small Magellanic Cloud. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2008, 388, 1198–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negueruela, I. On the nature of Be/X-ray binaries. Astronomy and Astrophysics 1998, 338, 505. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, B.F.; Dalcanton, J.J.; Stilp, A.; Dolphin, A.; Skillman, E.D.; Radburn-Smith, D. The ACS nearby galaxy survey treasury. XI. The remarkably undisturbed NGC 2403 disk. The Astrophysical Journal 2013, 765, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, P.A.; Drissen, L.; Abbott, J.B.; Royer, P.; Smartt, S.J. Gemini observations of Wolf-Rayet stars in the Local Group starburst galaxy IC 10. A&A 2003, 404, 483–493. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).