Submitted:

02 May 2025

Posted:

08 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. NuSTAR Observations and Data Processing

3. Analysis and Results

3.1. Timing Analysis

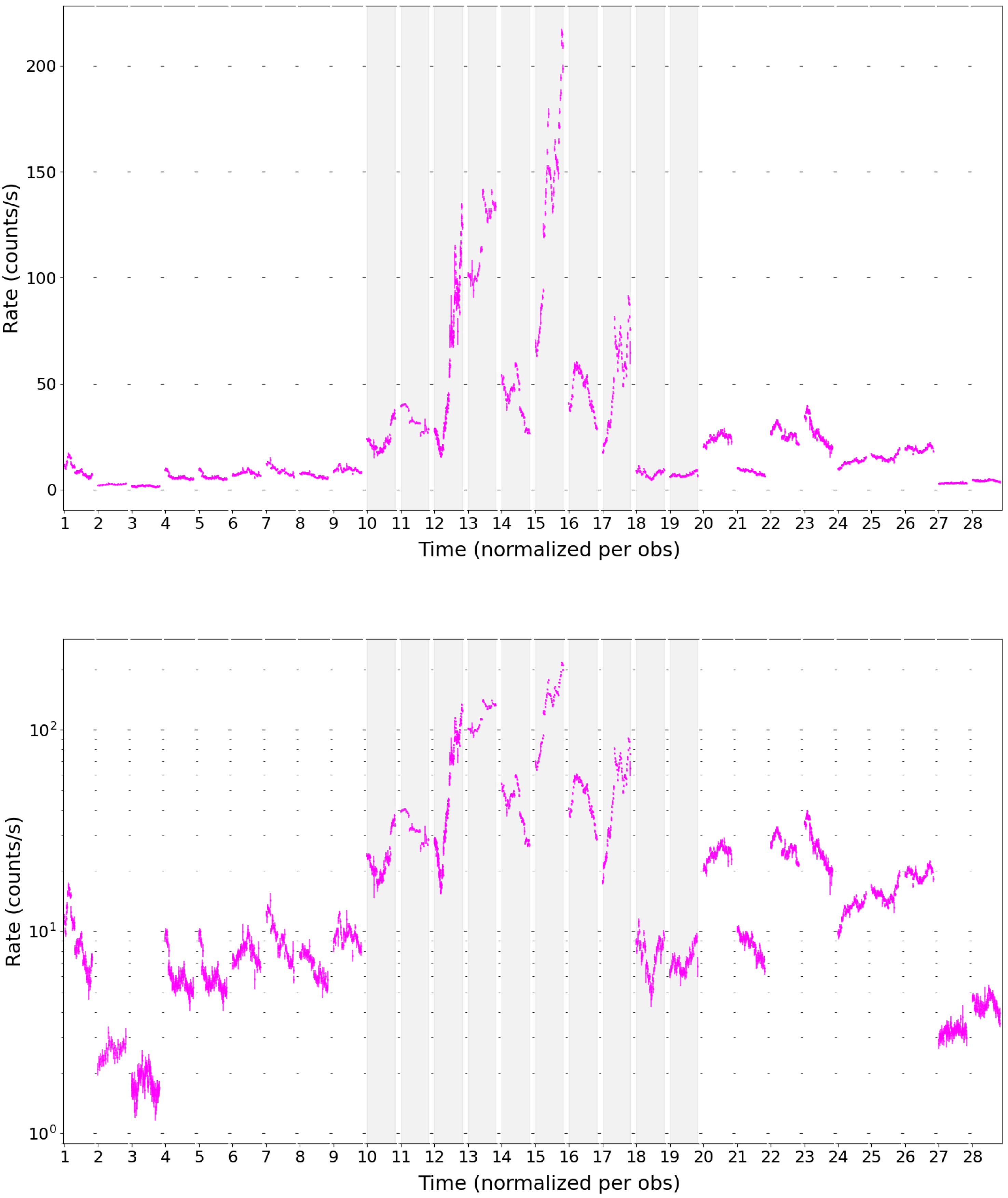

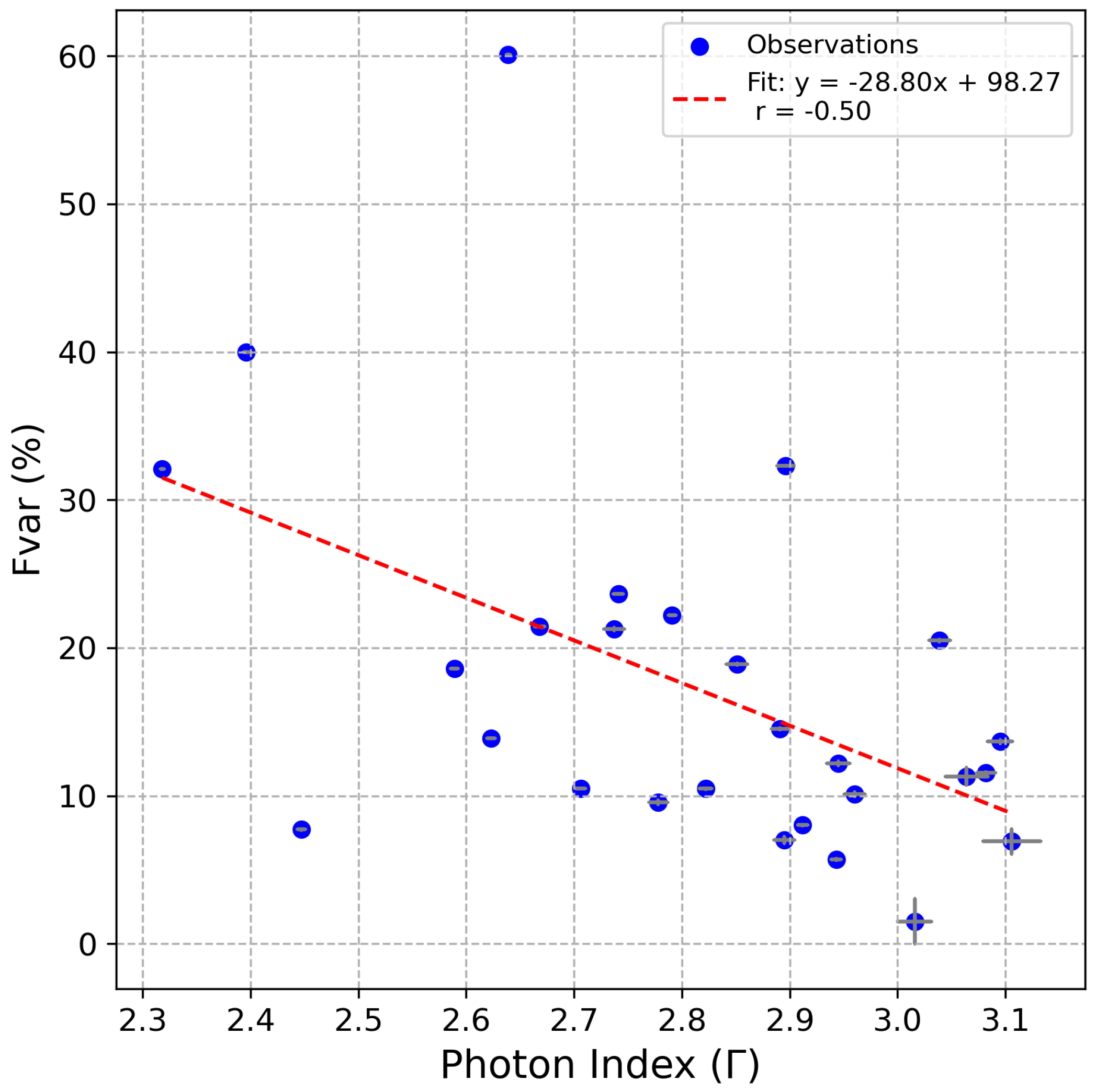

3.1.1. Flux Variability

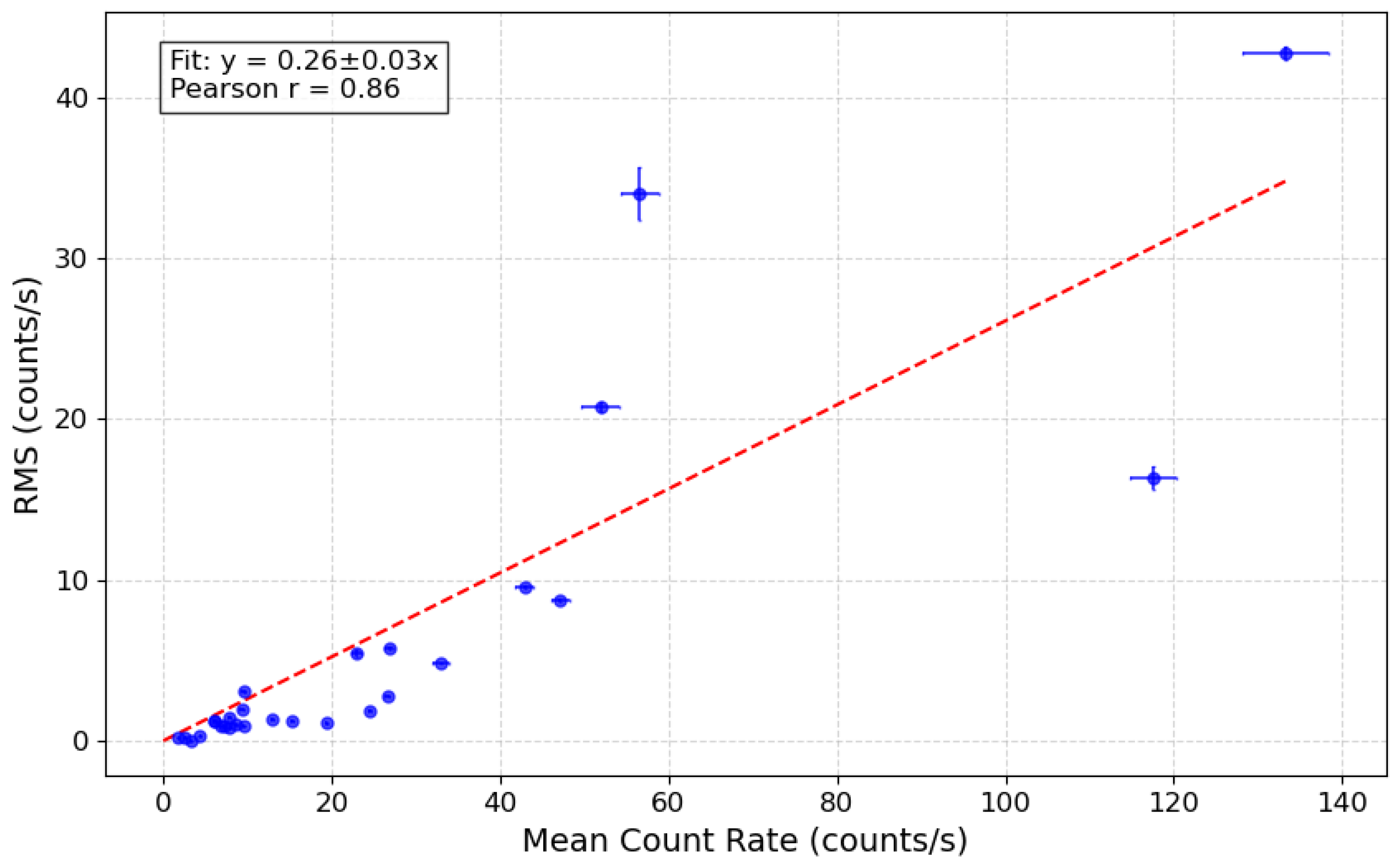

3.2. RMS–Flux Correlation

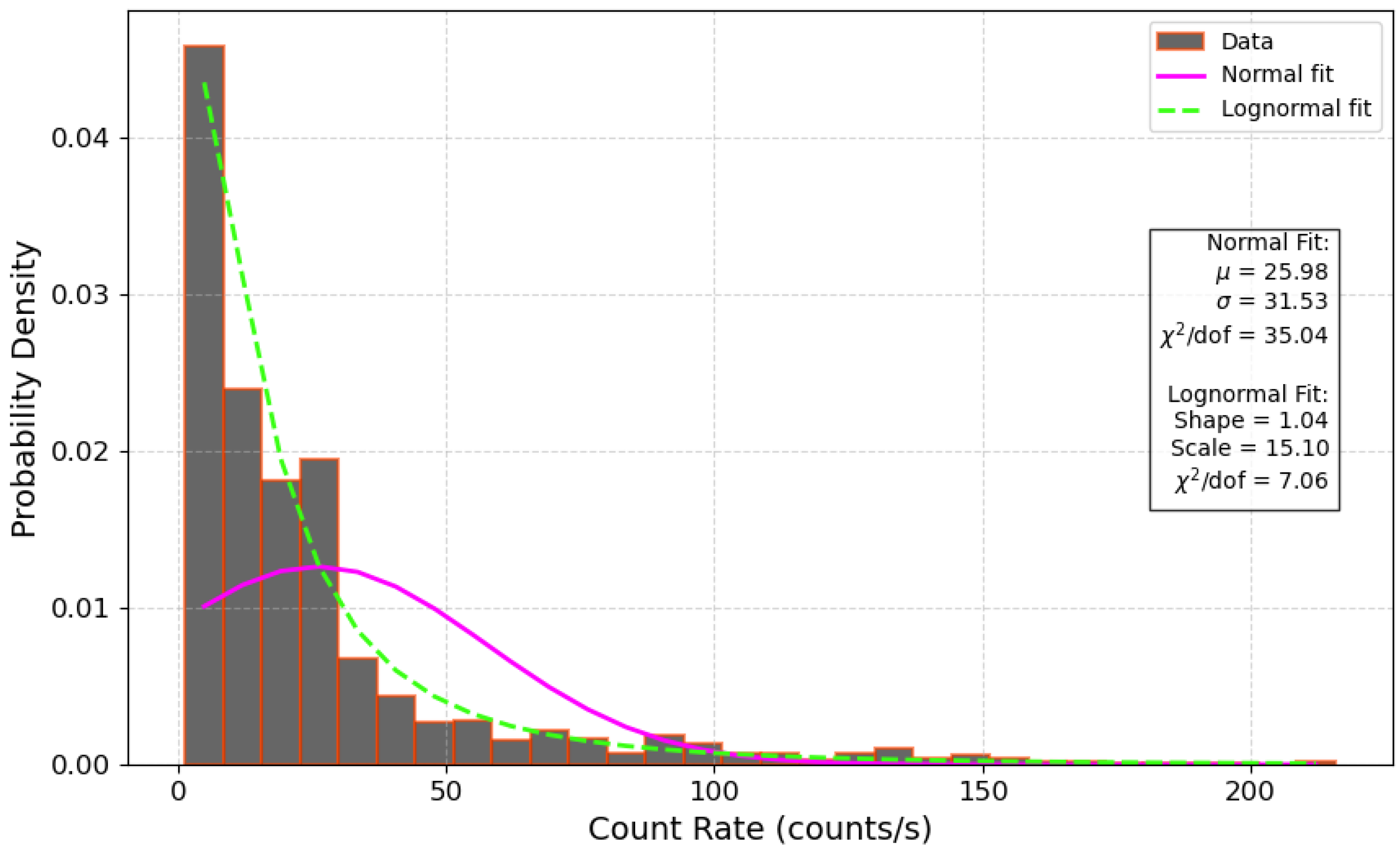

3.2.1. Flux Distribution and PDF

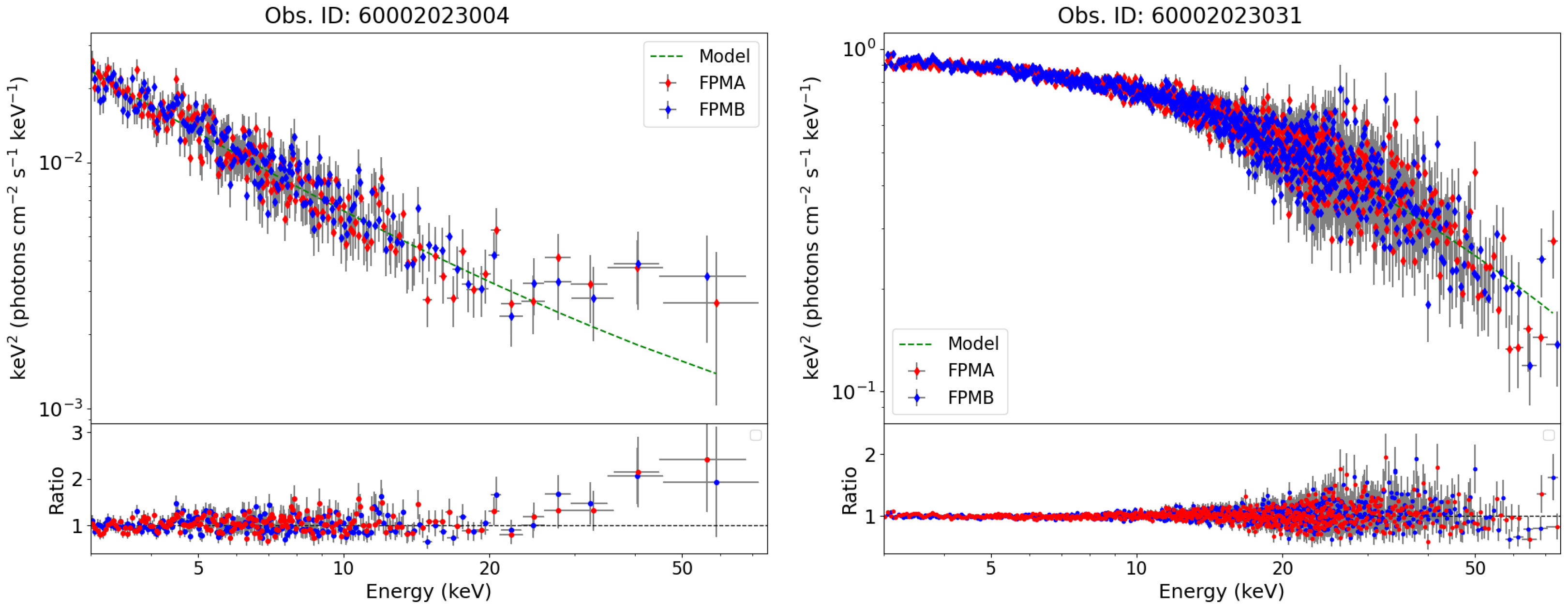

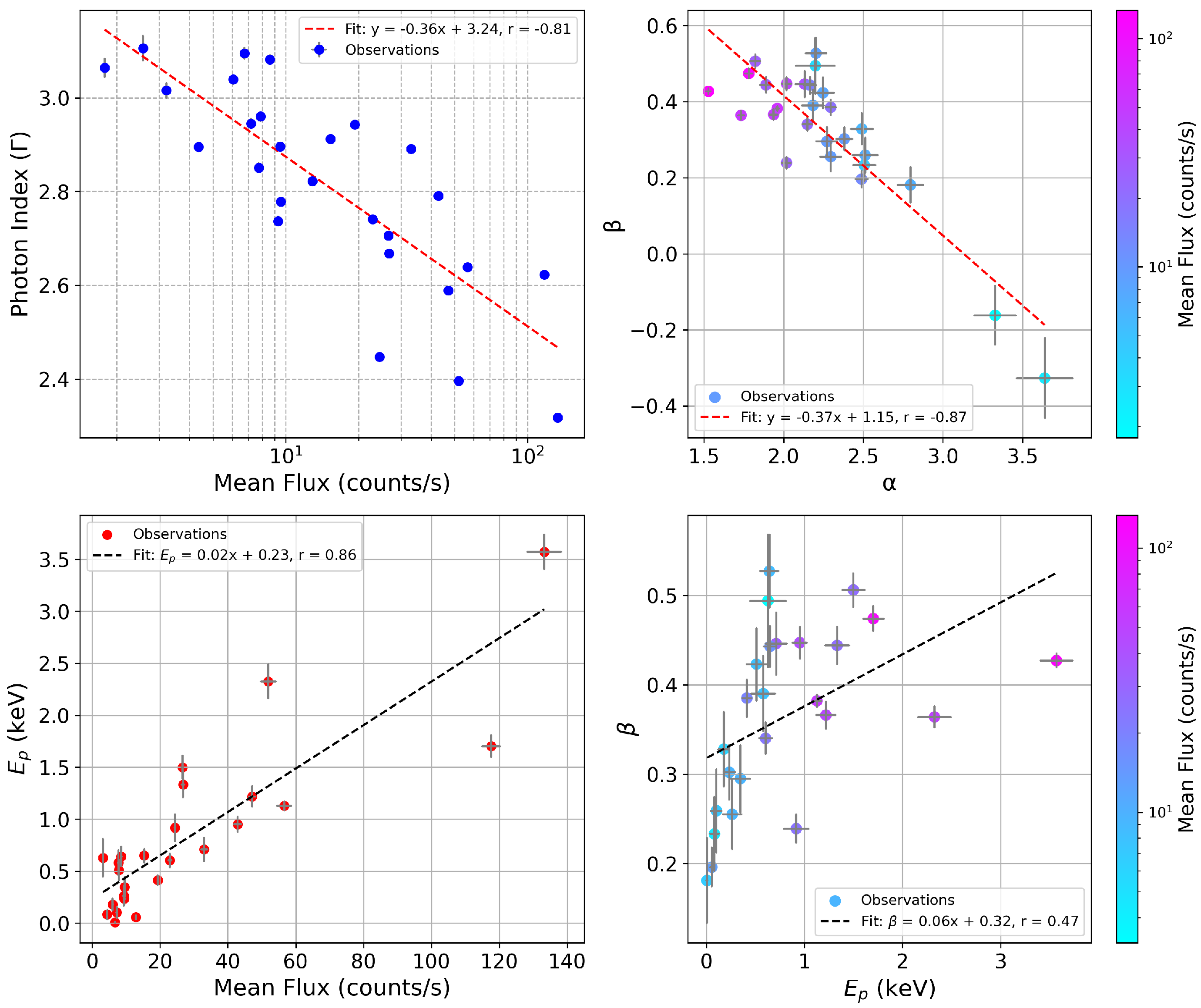

3.3. Spectral Analysis

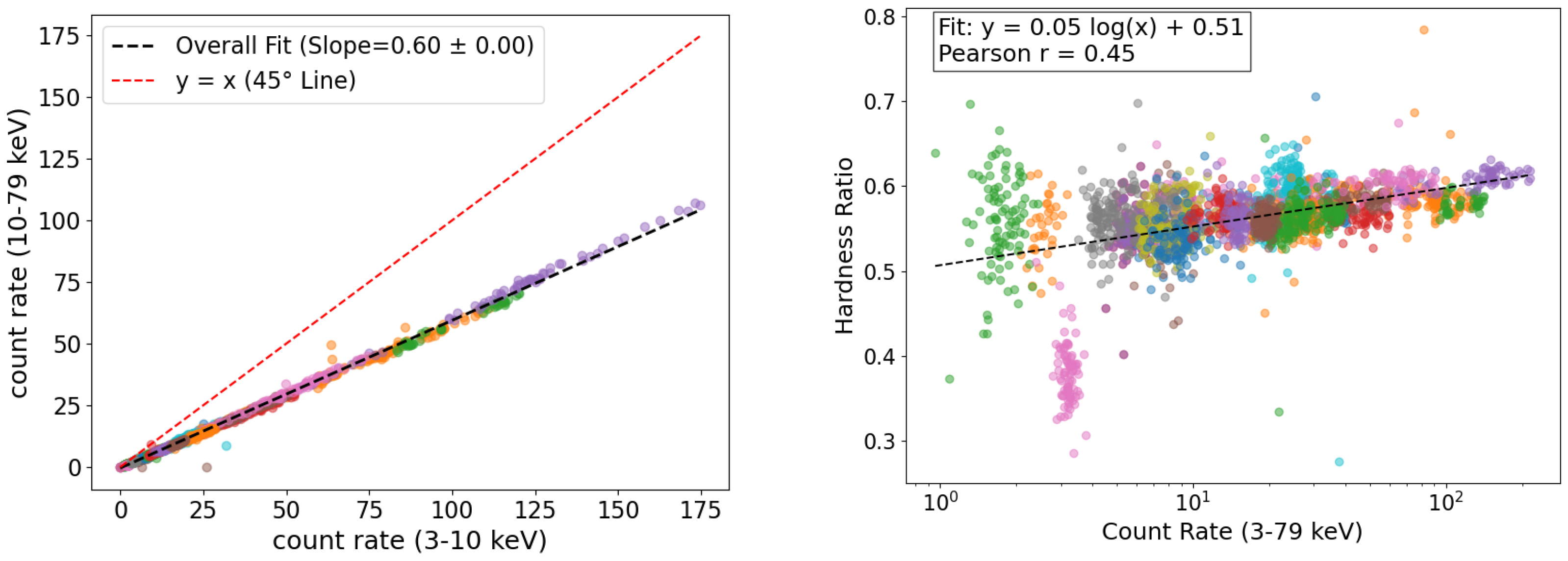

3.3.1. Hardness Ratio

3.4. Spectral Modeling

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Mrk 421 exhibited extreme variability, with flux changes of up to a factor of 200 over a 12-year period, including a 15-day flaring event during which the source brightened by more than a factor of 10. This dramatic variability is likely driven by an increase in the maximum Lorentz factor during shock acceleration, highlighting the dynamic nature of the particle acceleration processes in the jet.

- The hard X-ray variability displays a linear RMS-flux relation and a lognormal flux distribution. These characteristics suggest that the variability arises from multiplicative processes, rather than additive ones, pointing to a cascading or interconnected mechanism governing the emission.

- A strong correlation is observed between the count rates in the low-energy (3–10 keV) and high-energy (10–79 keV) bands, indicating that synchrotron emission dominates the X-ray output across these energy ranges.

- Spectral analysis reveals a weak but consistent harder-when-brighter trend, with spectra best described by log-parabolic models exhibiting curvature and occasional breaks. The photon index and curvature parameters of the log-parabola model are anti-correlated, and the spectral peak shifts to higher energies with increasing flux. These features collectively support a scenario of energy-dependent stochastic particle acceleration shaping the emission.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGN | Active Galactic Nucleus |

| BL Lacertae | BL Lac |

| BPL | Broken Power Law |

| FV | Fractional Variability |

| MWL | Multi-Wavelength |

| RMS | Root Mean Square |

| LP | Log-Parabola |

| PL | Power Law |

| TeV | Teraelectronvolt |

| VLBI | Very Long Baseline Interferometry |

| VHE | Very High Energy |

References

- Meier, D. L. Black Hole Astrophysics: The Engine Paradigm, Springer, Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2012.

- Urry, C.M.; Padovani, P. Unified Schemes for Radio-Loud Active Galactic Nuclei. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 1995, 107, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandford, R.; Meier, D.; Readhead, A. Relativistic Jets from Active Galactic Nuclei. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2019, 57, 467–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraschi, L., Ghisellini, G., & Celotti, A. A jet model for the gamma-ray emitting blazar 3C 279. ApJL 1992, 397, L5.

- Bloom, S. D., & Marscher, A. P. An Analysis of the Synchrotron Self-Compton Model for the Multi–Wave Band Spectra of Blazars. ApJ 1996, 461, 657.

- Dermer, C. D., & Schlickeiser, R. Thermal Comptonization Model for the High Energy Emission of Seyfert Active Galactic Nuclei. ApJ 1993, 416, 458.

- Sikora, M. High-energy radiation from active galactic nuclei. ApJS 1994, 90, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błażejowski, M., Sikora, M., Moderski, R., & Madejski, G.M. Comptonization of Infrared Radiation from Hot Dust by Relativistic Jets in Quasars. ApJ 2000, 545, 107. [CrossRef]

- Mannheim, K.; Biermann, P.L. Gamma-ray flaring of 3C 279 - A proton-initiated cascade in the jet? A&A 1992, 253, L21. [Google Scholar]

- Aharonian, F. A. TeV gamma rays from BL Lac objects due to synchrotron radiation of extremely high energy protons. New Astron. 2000, 5, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mücke, A., Protheroe, R. J., Engel, R., Rachen, J. P., & Stanev, T. BL Lac objects in the synchrotron proton blazar model. Astroparticle Physics 2003, 18, 593.

- Bhatta, G.,Mohorian,M., & Bilinsky,I. Hard X-ray properties of NuSTAR blazars. A&A 2018, 619, A93.

- Abdo, A.A.; Ackermann, M.; Ajello, M.; Antolini, E.; Baldini, L.; Ballet, J.; Barbiellini, G.; Bastieri, D.; Bechtol, K.; Bellazzini, R.; et al. Gamma-ray Light Curves and Variability of Bright Fermi-detected Blazars. Astrophys. J. 2010, 722, 520–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, G., Zola, S., Drozdz, M., et al. Catching profound optical flares in blazars. MNRAS 2023, 520, 2633–2643. [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, G. Blazar Mrk 501 shows rhythmic oscillations in its γ-ray emission. MNRAS 2019, 487, 3990–3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, G. Radio and γ-Ray Variability in the BL Lac PKS 0219–164: Detection of Quasi-periodic Oscillations in the Radio Light Curve. ApJ 2017, 847, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A. Multi-Wavelength Intra-Day Variability and Quasi-Periodic Oscillation in Blazars. Galaxies 2018, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, G., Zola, S., Stawarz, Ł., et al. Detection of Possible Quasi-periodic Oscillations in the Long-term Optical Light Curve of the BL Lac Object OJ 287. ApJ 2016, 832, 47. [CrossRef]

- MAGIC Collaboration, Abe, K., Abe, S., et al. Insights from the first flaring activity of a high synchrotron peaked blazar with X-ray polarization and VHE gamma rays. A&A 2025, 695, A217.

- Abe, K., Abe, S., Abhir, J., et al. Characterization of Markarian 421 during its most violent year: Multiwavelength variability and correlations. A&A 2025, 694, A195.

- Markowitz, A.G., Nalewajko, K., Bhatta, G., et al. Rapid X-ray variability in Mkn 421 during a multiwavelength campaign. MNRAS 2022, 513, 1662–1679. [CrossRef]

- Baloković, M., Paneque, D., Madejski, G., et al. Multiwavelength Study of Quiescent States of Mrk 421 with Unprecedented Hard X-Ray Coverage Provided by NuSTAR in 2013. ApJ 2016, 819, 156. [CrossRef]

- Abdo, A.A.; Ackermann, M.; Ajello, M.; et al. Fermi Large Area Telescope Observations of Markarian 421: The Missing Piece of its Spectral Energy Distribution. ApJ 2011, 736, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błażejowski, M.; Blaylock, G.; Bond, I.H.; et al. A Multiwavelength View of the TeV Blazar Markarian 421: Correlated Variability, Flaring, and Spectral Evolution. ApJ 2005, 630, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossati, G.; Buckley, J.H.; Bond, I.H.; et al. Multiwavelength Observations of Markarian 421 in 2001 March: An Unprecedented View on the X-Ray/TeV Correlated Variability. ApJ 2008, 677, 906–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; et al. Correlated Variability of the X-Ray and TeV Gamma-Ray Emission from Markarian 421. ApJ 1996, 470, L89–L92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraschi, L.; Fossati, G.; Tavecchio, F.; et al. Simultaneous X-Ray and TEV Observations of a Rapid Flare from Markarian 421. ApJL 1999, 526, L81–L84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkmann, W., Papadakis, I.E., den Herder, J.W.A., & Haberl, F. Temporal variability of Mrk 421 from XMM-Newton observations. A&A 2003, 402, 929–947.

- Brinkmann, W., Papadakis, I.E., Raeth,C., Mimica,P., & Haberl, F. XMM-Newton timing mode observations of MrkLET mode observations of Mrk 421. A&A 2005, 443, 397–411.

- Tramacere, A., Giommi, P., Perri, M., Verrecchia, F., & Tosti, G. Swift observations of the very intense flaring activity of Mrk 421 during 2006. I. Phenomenological picture of electron acceleration and predictions for MeV/GeV emission. A&A 2009, 501, 879–898.

- Isobe, N., Sugimori, K., Kawai, N., et al. Bright X-Ray Flares from the BL Lac Object Markarian 421, Detected with MAXI in 2010 January and February. PASJ 2010, 62, L55. [CrossRef]

- Pian, E., Türler, M., Fiocchi, M., et al. An active state of the BL Lacertae object Markarian 421 detected by INTEGRAL in April 2013. A&A 2014, 570, A77.

- Kataoka, J., & Stawarz, Ł. Inverse Compton X-Ray Emission from TeV Blazar Mrk 421 During a Historical Low-flux State Observed with NuSTAR. ApJ 2016, 827, 55.

- Akbar, S., Shah, Z., Misra, R., Iqbal, N., & Tantry, J. Probing spectral evolution and intrinsic variability of Mkn 421: A multi-epoch AstroSat study of X-ray spectra. JHEAp 2025, 45, 438–455. [CrossRef]

- Kapanadze, B., Dorner, D., Vercellone, S., et al. X-Ray Flaring Activity of MRK 421 in the First Half of 2013. ApJ 2016, 831, 102. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A., Gupta, A.C., & Wiita, P.J. X-Ray Intraday Variability of Five TeV Blazars with NuSTAR. ApJ 2017, 841, 123. [CrossRef]

- Noel, A. P., Gaur, H., Gupta, A. C., et al. X-Ray Intraday Variability of the TeV Blazar Markarian 421 with XMM-Newton. ApJS 2022, 262, 4. [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, W., Sembay, S., Griffiths, R.G., et al. XMM-Newton observations of Markarian 421. A&A 2001, 365, L162–L167.

- Nicastro, F., Mathur, S., Elvis, M., et al. Chandra Detection of the First X-Ray Forest along the Line of Sight To Markarian 421. ApJ 2005, 629, 700–718. [CrossRef]

- Kaastra, J. S., Werner, N., Herder, J. W. A. den, et al. The O VII X-Ray Forest toward Markarian 421: Consistency between XMM-Newton and Chandra. ApJ 2006, 652, 189–197. [CrossRef]

- Ravasio, M., Tagliaferri, G., Ghisellini, G., & Tavecchio,F. Observing Mkn 421 with XMM-Newton: The EPIC-PN point of view. A&A 2004, 424, 841–855.

- Khatoon, R., et al. Correlations between X-ray spectral parameters of Mkn 421 using long-term Swift-XRT data. MNRAS 2022, 515, 3749–3759. [CrossRef]

- Di Gesu, L., Donnarumma, I., Tavecchio, F., et al. The X-Ray Polarization View of Mrk 421 in an Average Flux State as Observed by the Imaging X-Ray Polarimetry Explorer. ApJL 2022, 938, L7. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, F. A., Craig, W. W., Christensen, F. E., et al. The Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR) High-energy X-Ray Mission. ApJ 2013, 770, 103. [CrossRef]

- Paliya, V. S., Böttcher, M., Diltz, C., et al. The Violent Hard X-Ray Variability of Mrk 421 Observed by NuSTAR in 2013 April. ApJ 2015, 811, 143. [CrossRef]

- Edelson, R., Turner, T. J., Pounds, K., et al. X-Ray Spectral Variability and Rapid Variability of the Soft X-Ray Spectrum Seyfert 1 Galaxies Arakelian 564 and Ton S180. ApJ 2002, 568, 610–626. [CrossRef]

- Nandra, K., George, I.M., Mushotzky, R.F., Turner, T.J., & Yaqoob, T. ASCA Observations of Seyfert 1 Galaxies. I. Data Analysis, Imaging, and Timing. ApJ 1997, 476, 70–82. [CrossRef]

- Edelson, R.A., Krolik, J.H., & Pike, G.F. Broad-Band Properties of the CfA Seyfert Galaxies. III. Ultraviolet Variability. ApJ 1990, 359, 86. [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, S., Edelson, R., Warwick, R.S., & Uttley, P. On characterizing the variability properties of X-ray light curves from active galaxies. MNRAS 2003, 345, 1271–1284. [CrossRef]

- Aleksić, J., Ansoldi, S., Antonelli, L.A., et al. The 2009 multiwavelength campaign on Mrk 421: Variability and correlation studies. A&A 2015, 576, A126.

- Bhatta, G.; Webb, J. Microvariability in BL Lacertae: “Zooming” into the Innermost Blazar Regions. Galaxies 2018, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, H.R., Carini, M.T., & Goodrich, B.D. Rapid variability in the optical polarization of the BL Lacertae object OJ 287. Natur 1989, 337, 627–629. [CrossRef]

- Pininti, V.R., Bhatta,G., Paul,S., et al. Exploring short-term optical variability of blazars using TESS. MNRAS 2023, 518, 1459–1471. [CrossRef]

- Dinesh, A., Bhatta, G., Adhikari, T. P., et al. Constraining X-Ray Variability of the Blazar 3C 273 Using XMM-Newton Observations over Two Decades. ApJ 2023, 955, 121. [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, G., Chaudhary, S.C., Dhital,N., et al. Probing X-Ray Timing and Spectral Variability in the Blazar PKS 2155–304 over a Decade of XMM-Newton Observations. ApJ 2025, 981, 118. [CrossRef]

- Uttley, P., McHardy, I.M., & Vaughan, S. Non-linear X-ray variability in X-ray binaries and active galaxies. MNRAS 2005, 359, 345–362. [CrossRef]

- Gleissner, T., Wilms, J., Pottschmidt, K., et al. Long term variability of Cyg X-1. II. The rms-flux relation. A&A 2004, 414, 1091–1104.

- Heil, L.M., Vaughan, S., & Uttley, P. The ubiquity of the rms-flux relation in black hole X-ray binaries. MNRAS 2012, 422, 2620–2631. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N., Yi, T.-F., Wang, L., et al. Comprehensive Study of the Blazars from Fermi-LAT LCR: The Log-Normal Flux Distribution and Linear rms-Flux Relation. RAA 2023, 23, 115011. [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, G.; Dhital, N. The Nature of γ-Ray Variability in Blazars. Astrophys. J. 2020, 891, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, P., Sinha, A., Misra, R., Singh, K.P., & de Gouveia Dal Pino, E.M. Gamma-Ray Flux Distribution and Nonlinear Behavior of Four LAT Bright AGNs. ApJ 2017, 849, 138. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, J., Ghosh, R., Chatterjee, R., & Das, N. Blazar Variability: A Study of Nonstationarity and the Flux-Rms Relation. ApJ 2020, 897, 25. [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, G. Characterizing Long-term Optical Variability Properties of γ-Ray-bright Blazars. ApJ 2021, 910, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapanadze, B., Gurchumelia, A., Dorner, D., et al. Swift Observations of Mrk 421 in Selected Epochs. III. Extreme X-Ray Timing/Spectral Properties and Multiwavelength Lognormality during 2015 December–2018 April. ApJS 2020, 247, 27. [CrossRef]

- Wani, K.; Gaur, H. Study of Intra-Day Flux Distributions of Blazars Using XMM-Newton Satellite. Univ 2022, 8, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Z., Mankuzhiyil, N., Sinha, A., et al. Log-normal flux distribution of bright Fermi blazars. RAA 2018, 18, 141. [CrossRef]

- Gokus, A., Wilms, J., Kadler, M., et al. Rapid variability of Markarian 421 during extreme flaring as seen through the eyes of XMM-Newton. MNRAS 2024, 529, 1450–1462. [CrossRef]

- Kapanadze, B., Vercellone, S., Romano, P., et al. Swift Observations of Mrk 421 in Selected Epochs. I. The Spectral and Flux Variability in 2005–2008. ApJ 2018, 854, 66. [CrossRef]

- Aggrawal, V., Pandey, A., Gupta, A.C., et al. X-ray intraday variability of the TeV blazar Mrk 421 with Chandra. MNRAS 2018, 480, 4873–4883. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A., Gupta, A.C., & Wiita, P.J. Multi-wavelength variability of the blazar PKS 0208–512: synchrotron peak shift and harmonic variability. MNRAS 2018, 481, 3563–3574.

- Gupta, A. C. X-ray Flux and Spectral Variability of the TeV Blazars Mrk 421 and PKS 2155–304. Galax 2020, 8, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaud, K. A. XSPEC: The First Ten Years. ASP Conf. Ser. 1996, 101, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Wilms, J., Allen, A., & McCray, R. On the Absorption of X-Rays in the Interstellar Medium. ApJ 2000, 542, 914–924. [CrossRef]

- Kalberla, P.M.W., Burton, W.B., Hartmann, D., et al. The Leiden/Argentine/Bonn (LAB) Survey of Galactic HI. A&A 2005, 440, 775–782.

- HI4PI Collaboration, Ben Bekhti, N., Flöer, L., et al. HI4PI: A full-sky H I survey based on EBHIS and GASS. A&A 2016, 594, A116.

- Massaro, E., Perri, M., Giommi,P., & Nesci, R. Log-parabolic spectra and the 3C 273 jet. A&A 2004, 413, 489–495.

- Tanihata, C., Kataoka, J., Takahashi, T., & Madejski, G.M. Evolution of the Synchrotron Spectrum in Markarian 421 during the 1998 Campaign. ApJ 2004, 601, 759–770. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Zhu, S., Xue, Y., et al. X-Ray Spectral Variations of Synchrotron Peak in BL Lacs. ApJ 2019, 885, 8. [CrossRef]

- Massaro, E., Perri, M., Giommi, P., Nesci, R., & Verrecchia, F. Log-parabolic spectra and particle acceleration in blazars. II. The BeppoSAX wide band X-ray spectra of Mkn 501. A&A 2004, 422, 103–111.

- Katarzyński, K., Ghisellini, G., Tavecchio, F., et al. Correlation between the TeV and X-ray emission in high-energy peaked BL Lac objects. A&A 2005, 433, 479–496.

- Cerruti, M., Zech, A., Boisson, C., et al. Leptohadronic single-zone models for the electromagnetic and neutrino emission of TXS 0506+056. MNRAS 2019, 483, L12–L16. [CrossRef]

- Petropoulou, M.; Mastichiadis, A. Bethe-Heitler emission in BL Lacs: filling the gap between X-rays and γ-rays. MNRAS 2015, 447, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskell, C. M. Lognormal X-Ray Flux Variations in an Extreme Narrow-Line Seyfert 1 Galaxy. ApJL 2004, 612, L21–L24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, A., Chatterjee, R., Mitra, K., & Mondal, S. rms-flux relation and disc-jet connection in blazars in the context of the internal shocks model. MNRAS 2022, 510, 3688–3700. [CrossRef]

- Giebels, B.; Degrange, B. Lognormal variability in BL Lacertae. A&A 2009, 503, 797–799. [Google Scholar]

| 1 |

| Serial | Date | ID | Exposure(s) | Mean ± Std (counts/s) | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2012-07-08 | 10002016001 | 24884 | 9.49 ± 3.09 | 32.31 ± 0.05 |

| 2 | 2013-01-02 | 60002023002 | 9152 | 2.57 ± 0.24 | 6.92 ± 0.87 |

| 3 | 2013-01-10 | 60002023004 | 22631 | 1.76 ± 0.27 | 11.32 ± 0.63 |

| 4 | 2013-01-15 | 60002023006 | 24181 | 6.07 ± 1.28 | 20.50 ± 0.11 |

| 5 | 2013-01-20 | 60002023008 | 24966 | 6.07 ± 1.28 | 20.50 ± 0.11 |

| 6 | 2013-02-06 | 60002023010 | 19302 | 7.88 ± 0.87 | 10.12 ± 0.18 |

| 7 | 2013-02-12 | 60002023012 | 14775 | 9.30 ± 2.02 | 21.27 ± 0.11 |

| 8 | 2013-03-11 | 60002023018 | 17472 | 6.76 ± 0.97 | 13.66 ± 0.15 |

| 9 | 2013-03-17 | 60002023020 | 16554 | 9.54 ± 1.07 | 9.57 ± 0.17 |

| 10 | 2013-04-02 | 60002023022 | 24767 | 23.07 ± 5.63 | 23.66 ± 0.03 |

| 11 | 2013-04-10 | 60002023024 | 5757 | 33.00 ± 4.89 | 14.52 ± 0.08 |

| 12 | 2013-04-11 | 60002023025 | 57507 | 56.32 ± 34.02 | 60.09 ± 0.01 |

| 13 | 2013-04-12 | 60002023027 | 7629 | 117.60 ± 16.43 | 13.90 ± 0.02 |

| 14 | 2013-04-13 | 60002023029 | 16508 | 42.26 ± 10.76 | 22.19 ± 0.01 |

| 15 | 2013-04-14 | 60002023031 | 15605 | 133.25 ± 42.79 | 32.09 ± 0.00 |

| 16 | 2013-04-15 | 60002023033 | 17276 | 46.86 ± 9.09 | 18.58 ± 0.02 |

| 17 | 2013-04-16 | 60002023035 | 20278 | 51.90 ± 20.79 | 40.00 ± 0.01 |

| 18 | 2013-04-18 | 60002023037 | 17795 | 7.74 ± 1.50 | 18.89 ± 0.10 |

| 19 | 2013-04-19 | 60002023039 | 15958 | 7.19 ± 0.93 | 12.20 ± 0.16 |

| 20 | 2017-01-03 | 60202048002 | 23691 | 24.41 ± 1.99 | 7.72 ± 0.06 |

| 21 | 2022-06-04 | 60702061002 | 21277 | 8.49 ± 1.40 | 11.54 ± 0.11 |

| 22 | 2022-06-07 | 60702061004 | 23280 | 26.65 ± 2.87 | 10.51 ± 0.04 |

| 23 | 2023-05-13 | 80801643002 | 44571 | 26.75 ± 5.78 | 21.45 ± 0.02 |

| 24 | 2023-12-06 | 60902024002 | 21293 | 12.95 ± 1.43 | 10.48 ± 0.05 |

| 25 | 2023-12-11 | 60902024004 | 21235 | 15.23 ± 1.37 | 8.03 ± 0.06 |

| 26 | 2023-12-18 | 60902024006 | 19990 | 19.18 ± 1.83 | 5.70 ± 0.07 |

| 27 | 2024-04-29 | 60902024010 | 20967 | 3.20 ± 0.20 | 1.52 ± 1.56 |

| 28 | 2024-05-03 | 60902024012 | 21025 | 4.38 ± 0.37 | 7.02 ± 0.24 |

| Observation ID | Model | Fit Statistic | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 1.21 (806.27/665) | ||

| 10002016001 | BPL | 1.19 (790.46/663) | |||

| LP | ... | 1.05 (699.01/664) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 1.16 (303.86/260) | ||

| 60002023002 | BPL | 1.17 (303.86/258) | |||

| LP | ... | 1.13 (295.19/259) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 0.92 (333.29/359) | ||

| 60002023004 | BPL | 0.92 (331.32/357) | |||

| LP | ... | 0.93 (329.69/358) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 1.09 (612.44/558) | ||

| 60002023006 | BPL | (4:BreakE/556)* | |||

| LP | ... | 0.98 (547.05/557) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | (192.12/) | ||

| 60002023008* | BPL | (188.21/) | |||

| LP | ... | (190.91/) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 1.16 (663.62/569) | ||

| 60002023010 | BPL | 0.95 (542.05/567) | |||

| LP | ... | 0.95 (543.52/568) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 1.00 (587.58/586) | ||

| 60002023012 | BPL | 0.91 (533.84/584) | |||

| LP | ... | 0.92 (541.22/585) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 0.91 (463.67/506) | ||

| 60002023018 | BPL | 0.90 (458.56/504) | |||

| LP | ... | 0.88 (448.56/505) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 1.01 (600.08/591) | ||

| 60002023020 | BPL | 0.90 (534.76/589) | |||

| LP | ... | 0.90 (531.65/590) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 1.47 (1320.83/895) | ||

| 60002023022 | BPL | 1.07 (958.93/893) | |||

| LP | ... | 1.04 (930.27/894) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 1.34 (835.71/621) | ||

| 60002023024 | BPL | 1.07 (667.26/619) | |||

| LP | ... | 1.05 (652.12/620) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 3.30 (4713.86/1426) | ||

| 60002023025 | BPL | 1.18 (1681.61/1424) | |||

| LP | ... | 1.01 (1451.51/1425) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 2.29 (2352.14/1025) | ||

| 60002023027 | BPL | 1.06 (1088.72/1023) | |||

| LP | ... | 0.98 (1012.73/1024) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 1.75 (1612.25/917) | ||

| 60002023029 | BPL | 0.97 (891.22/915) | |||

| LP | ... | 0.92 (850.97/916) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 3.42 (4931.28/1440) | ||

| 60002023031 | BPL | 1.14 (1648.47/1438) | |||

| LP | ... | 1.06 (1531.32/1439) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 1.71 (1750.38/1020) | ||

| 60002023033 | BPL | 1.02 (1038.80/1018) | |||

| LP | ... | 0.99 (1014.38/1019) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 1.93 (2309.15/1191) | ||

| 60002023035 | BPL | 1.04 (1242.80/1189) | |||

| LP | ... | 0.98 (1168.20/1190) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 1.09 (619.21/566) | ||

| 60002023037 | BPL | 0.93 (524.59/564) | |||

| LP | ... | 0.91 (516.76/565) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 1.02 (535.31/524) | ||

| 60002023039 | BPL | 0.94 (494.59/522) | |||

| LP | ... | 0.96 (503.61/523) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 1.29 (1298.79/1006) | ||

| 60202048002 | BPL | 1.06 (1067.30/1004) | |||

| LP | ... | 1.04 (1054.17/1005) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 1.40 (800.31/570) | ||

| 60702061002 | BPL | 1.07 (610.69/568) | |||

| LP | ... | 1.05 (597.93/569) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 2.08 (1845.52/887) | ||

| 60702061004 | BPL | 1.16 (1030.93/885) | |||

| LP | ... | 1.11 (984.94/886) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 0.63 (811.57/1282) | ||

| 80801643002 | BPL | 0.24 (312.75/1280) | |||

| LP | ... | 0.20 (265.83/1281) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 1.07 (880.85/820) | ||

| 60902024002 | BPL | 1.06 (873.67/818) | |||

| LP | ... | 0.97 (799.67/819) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 1.56 (1254.12/799) | ||

| 60902024004 | BPL | 1.08 (865.23/797) | |||

| LP | ... | 1.03 (829.40/798) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 1.43 (1219.41/847) | ||

| 60902024006 | BPL | 1.02 (869.68/845) | |||

| LP | ... | 0.98 (829.82/846) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 4.92 (2554.74/519) | ||

| 60902024010 | BPL | 4.83 (2501.70/517) | |||

| LP | ... | 4.83 (2504.25/518) | |||

| PL | ... | ... | 1.22 (700.40/574) | ||

| 60902024012 | BPL | 1.22 (698.96/572) | |||

| LP | ... | 1.16 (669.90/573) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).