1. Introduction

The Lockyer proton model [

1,

6] achieves a remarkable precision in predicting the proton-to-electron mass ratio (within seven significant figures) by modeling the proton as a positron that forms the fundamental layer (level 0) and incorporates 18 nested energy layers of progressively higher frequency. Nevertheless the number of layers (18) remained empirically determined. Previous work linked this number to the thermodynamic conditions during hadronization, where the photon spectrum available at temperatures of

–

K favored the wavelength of the 18th layer (

m). See Appendix A. However, this cosmological argument did not fully address the

intrinsic stability of the 18-layer structure.

Furthermore, the Standard Model of particle physics, while spectacularly successful, harbors deep mysteries for which it offers no fundamental explanation. Chief among them is the replication of fermions into three generations (e.g., electron-muon-tauon, up-charm-top quarks) with identical quantum numbers but vastly different masses. The origin of this hierarchical structure and the specific values of the mass ratios remain completely unexplained.

In this paper, we extend the anisotropic multiverse framework [

7] to demonstrate that these two puzzles—the proton’s architecture and the fermion generation puzzle—share a common solution. We propose that anisotropy, induced by interactions with adjacent universes in a hyper-universe, creates three distinct stiffness axes (

). These axes govern both the maximum sustainable excitation energy within composite particles and the fundamental mass hierarchy of elementary fermions. We show that the 18th layer energy of the Lockyer’s proton (

) already surpasses the muon pair production threshold (

), implying that any additional energy would trigger a phase transition into second-generation particles rather than increasing the number of energy layers in the proton. This phase transition mechanism is directly observed in high-energy colliders through the production of heavy quarks and leptons. Thus, we provide a unified explanation for the internal structure of the proton, the origin and mass spectrum of the three fermion generations, neutrino oscillations, and offer new insights into cosmological anomalies.

Rather than being mutually exclusive, we propose that these two approaches are profoundly complementary. The Lockyer model may describe the proton’s fundamental mass structure—its ground-state energy configuration organized into nested layers. Conversely, the quark model of QCD describes the proton’s rich internal dynamics and response to excitations. In this synthesis, the quark content revealed in high-energy collisions could be interpreted as the resonant excitations of the Lockyer 3D layers’ internal geometry. This work aims to build a bridge between these perspectives by showing that the 18-layer limit, a key parameter in Lockyer’s mass calculation, arises from a fundamental phase transition boundary linked to the fermion mass hierarchy, thus offering a potential pathway to unifying the geometric and dynamical descriptions of the nucleon.

2. Theoretical Framework of Anisotropic Space

2.1. Origin of Anisotropy: Multiverse Boundary Conditions

We posit that the hyper-universe comprises multiple universe-domains, each undergoing cyclical expansions and contractions. The boundary of our universe-domain interacts with adjacent domains through energy-momentum exchange, breaking isotropic symmetry and defining three principal orthogonal eigenvectors with distinct stiffness parameters .

The resulting anisotropy is modeled as:

where

is the effective energy density and

S represents sources from adjacent universes.

2.2. Fermion Generations as Fundamental Vibrational Modes

The mass hierarchy of all three fermion generations arises from excitations along the fundamental eigenmodes of the anisotropic spacetime lattice. The mass of a particle is interpreted as the energy of its localized, resonant vibration along a specific stiffness axis:

First Generation (e.g., electron e, up quark u, down quark d): Fundamental excitations of the mode with the lowest eigenfrequency (). These represent the ground-state vibrations of the spacetime lattice, corresponding to the least stiff axis.

Second Generation (e.g., muon , charm quark c, strange quark s): Fundamental excitations of the mode with the intermediate eigenfrequency (). These represent excitations of the intermediate stiffness axis, requiring a higher energy threshold.

Third Generation (e.g., tauon , top quark t, bottom quark b): Fundamental excitations of the mode with the highest eigenfrequency (). These represent excitations of the stiffest axis, requiring the highest energy input.

Particle decay processes (e.g., , ) are recast as natural relaxation processes: a high-energy, meta-stable excitation of a high-frequency mode interacts with the lattice background and cascades down to lower-energy, more stable modes, radiating away excess energy (photons, gluons, other particles). The entire fermion mass hierarchy is therefore a direct manifestation of the discrete spectrum of eigenfrequencies of the spatial medium. The specific mass values within each generation are determined by the detailed structure of their respective vibrations and their coupling to the Higgs field, which itself may be influenced by the anisotropic background.

2.3. Neutrino Oscillations as Geometric Interference

Neutrinos propagate as superpositions of the three fundamental eigenmodes. Each component evolves with phase factor

, creating interference patterns that manifest as flavor oscillations [

4,

5]. The probability amplitudes are governed by eigenfrequency differences

, providing a natural explanation for both solar and atmospheric oscillation regimes.

3. The Lockyer Proton Model and the 18-Layer Puzzle

Lockyer’s model [

1] constructs the proton from a positron (mass

) at its core, which itself contains 18 nested energy layers of progressively higher frequency and smaller wavelength, forming a hierarchical structure akin to a set of Russian dolls. Each layer

i contributes an energy:

where the factor

is not an ad hoc parameter. It is rigorously derived from the proton’s magnetic moment using fundamental geometric considerations and CODATA constants, accounting for the specific spacing between energy layers [

1,

6].

The 18th layer reaches

. The total proton mass is:

matching the CODATA value to seven significant figures. The neutron adds an electron and doubles the first two layers, yielding

.

The model’s success hinges on two parameters: the geometric factor and the number of layers (18). While arises from internal geometry, the number 18 lacked a first-principles derivation. A cosmological thermodynamic argument, based on the photon energy spectrum available during the hadronization epoch ( K), suggests that building beyond the 18th layer was highly improbable (see Appendix A for a detailed analysis).

However, this thermodynamic constraint alone does not explain the intrinsic stability of the 18-layer structure or why additional layers could not be added later in different energetic environments.

4. Anisotropic Space from Multiverse Boundary Conditions

The fundamental mechanism for anisotropic space originates from multiverse boundary conditions as detailed in

Section 2. This framework creates three distinct stiffness axes (

) that govern both the fermion mass hierarchy and neutrino oscillations. The electron, muon, and tauon masses scale as

for their respective axes, while neutrino oscillations arise from quantum interference effects between these anisotropic propagation modes, as the phase of each mass eigenstate evolves at a different rate (

), leading to a time-varying mixture of flavor eigenstates.

5. Energetic Limit and the Muon Production Threshold

The key insight is that the 18th layer’s energy (

) significantly surpasses the threshold for muon pair production:

This indicates a fundamental boundary:

Phase Transition: Adding energy beyond the 18th layer () would far exceed the muon production threshold. Instead of expanding the proton, this energy would create muon-antimuon pairs, representing excitations along the stiffer axis.

Geometric Constraint: The growth factor implies a large energy jump between layers. Adding even one more layer requires a discrete energy increment of , making the process inefficient and unstable.

Dimensional Symmetry: The number 18 is a multiple of 3, respecting the three-dimensional anisotropy of space. A symmetric closure of the structure is achieved at 18 layers, whereas 19 or 20 would break this symmetry.

Thus, the 18-layer proton represents the highest sustainable excitation along the "electron axis" () before the system transitions to the "muon axis" ().

The phase transition mechanism we describe is not merely theoretical but is experimentally observed in high-energy particle colliders. The production of second- and third-generation quarks (such as the charm, strange, top, and bottom quarks) and leptons (muons and tauons) in facilities like the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) occurs precisely when the collision energy exceeds specific thresholds. This phenomenon is the direct experimental signature of the transition we postulate: instead of adding energy to the internal structure of first-generation particles (e.g., protons), sufficient kinetic energy is converted to mass, creating fundamentally new, heavier excitations of the anisotropic spacetime field—i.e., particles of higher generations. This corroborates our model’s core principle: that exceeding energy thresholds specific to each anisotropic axis results in a phase transition to a higher-generation state, rather than the continuous growth of a foundational one.

6. Cosmological Consistency and Multiverse Implications

This mechanism is consistent with the cosmological hadronization scenario ([app:thermodynamic]Appendix A). The accepted temperature range for baryogenesis ( K) aligns perfectly with the energy required to build up to the 18th layer in the Lockyer model, harmonizing the proton’s structure with standard cosmological timelines.

As established, at energies exceeding the 18th-layer threshold, photon interactions preferentially create muons rather than adding internal energy to nascent protons. However, a critical question remains: why did ’exotic proton’ formation not occur at even higher temperatures, had they been available?

Let us hypothesize the existence of such higher-energy conditions. In this scenario, ’exotic’ Lockyer protons with 19 or more layers could potentially form. Following the subsequent universal expansion and cooling, these exotic protons would become unstable, triggering a phase transition. This transition would dissolve the exotic matter back into a primordial plasma. Upon further cooling, this plasma would once again undergo hadronization, but now at the lower energy density, exclusively forming the standard 18-layer proton—the configuration stable under these new conditions.

This reprocessing event would occur within a finite universal volume, simultaneously resetting all matter to the standard 18-layer configuration and distributing it uniformly throughout space. This offers a powerful dual explanation: it eradicates non-standard proton configurations while naturally accounting for the large-scale homogeneity observed in the CMB and Eliminating the Need for Primordial Inflation.

6.1. Eliminating the Need for Primordial Inflation

A major theoretical advancement of this framework is its potential to eliminate the need for a separate primordial inflation epoch. The standard inflationary paradigm, while successful in explaining homogeneity and flatness, remains an ad hoc addition without a clear causal mechanism or direct experimental verification. In our model, the phase transition that reprocesses exotic matter also naturally homogenizes the universe within a finite volume. The subsequent distribution of standard 18-layer protons occurs in a pre-homogenized state. This provides a causal mechanism for large-scale uniformity directly from the matter creation process itself, offering a compelling alternative to inflation that is inherently linked to the fundamental structure of matter and the anisotropic nature of spacetime.

7. Discussion

Our findings suggest that the anisotropic structure of space, dictated by multiverse boundary conditions, is not a minor perturbation but a fundamental organizing principle of physical reality. The 18-level limit of the Lockyer proton and the three fermion generations are two manifestations of the same underlying constraint: the existence of three discrete, hierarchical stiffness axes () in the fabric of spacetime.

The phase transition we describe—where energy input beyond a critical threshold creates particles of a higher generation rather than exciting a lower one—provides a mechanistic explanation for a well-known empirical fact in particle physics: the production thresholds for strange, charm, bottom, and top quarks in colliders. This shifts the view of fermion generations from an arbitrary replication in the Standard Model to a necessary consequence of anisotropic spacetime vibrations. The electron, muon, and tauon are not simply heavier copies; they are the same fundamental excitations of increasingly stiff vibrational modes.

Critically, the geometric interference mechanism for neutrino oscillations provides independent empirical support for the existence of three distinct anisotropic axes. The observed values in solar and atmospheric neutrino experiments correspond directly to the squared eigenfrequency differences of the spacetime lattice, offering a quantitative testable prediction of our model.

Cosmologically, this framework offers a paradigm shift. A direct signature of the larger multiverse geometry would be the observation by JWST of systematic variations in the apparent size, mass, or evolutionary state of galaxies at similar redshifts, correlated with their direction on the sky. Such an anisotropic pattern would suggest that these galaxies belong to adjacent universe-domains with slightly different fundamental parameters (e.g., stiffness axes ), leading to different physical laws and evolutionary histories. Furthermore, the matter-instability phase transition, triggered by the evolving stiffness axes, provides a novel bounce mechanism that can naturally homogenize the universe, challenging the necessity of primordial inflation.

The key strength of this model is its ability to render ad hoc parameters of other theories—the number of proton layers, the three generations, the initial conditions for inflation—into calculable and testable consequences of a single foundational principle: spacetime anisotropy.

8. Conclusion

We have demonstrated that a framework based on anisotropic spacetime, induced by multiverse boundary conditions, provides a unified and causal explanation for some major puzzles in physics:

The Proton’s Stability: The 18-energy-level limit in Lockyer’s model is explained as a fundamental stability point where the energy required to create an additional layer is sufficient to generate second-generation particles rather than expanding the proton. This model achieves remarkable precision without rejecting the quark model of QCD, which may instead describe the proton’s response to external high-energy excitations.

The Fermion Generation Puzzle: The three generations of leptons and quarks are explained as fundamental vibrational modes along three distinct stiffness axes () of spacetime. The production thresholds for second and third-generation particles in colliders are direct experimental signatures of the phase transitions between these anisotropic modes.

Neutrino Oscillations: The framework provides a natural geometric explanation for neutrino flavor oscillations through interference between anisotropic propagation modes, directly linking the values to the stiffness parameters of spacetime.

Cosmological Homogeneity: The phase transition that reprocesses exotic matter also distributes the standard 18-layer protons uniformly throughout space, providing a natural mechanism for large-scale homogeneity.

Eliminating Primordial Inflation: This homogenization mechanism occurs within a finite volume during the bounce phase, potentially eliminating the need for a separate primordial inflation epoch to explain the isotropy of the CMB radiation.

JWST Anomalies: The framework provides an interpretive lens for anomalous high-redshift galaxies observed by JWST, suggesting they could belong to adjacent universe-domains with different fundamental parameters.

This framework offers a suite of testable predictions that span particle physics and cosmology. These include searching for directional variations in fundamental parameters, such as particle decay rates or high-energy gamma-ray event distributions, that could correlate with the proposed cosmic anisotropic axes. Furthermore, if the observed anomalies of mature, high-redshift galaxies by JWST [

8,

9] are confirmed and exhibit a statistically significant directional anisotropy—such as a correlation between their apparent mass, size, or evolution state and their position on the sky—this would constitute a profound corroboration of our hypothesis. Such a finding would suggest that these galaxies belong to adjacent universe-domains within the hyper-universe, where the fundamental stiffness parameters

(and thus the laws of physics) may differ slightly from our own. Future work will focus on quantifying the stiffness parameters

from fermion mass data, modeling anisotropic gamma-ray propagation, and exploring implications for cosmological bounce dynamics and large-scale structure formation.

By positing that the architecture of particles and the structure of the cosmos are deeply intertwined through the geometry of spacetime, this work aims to open a new path toward a more complete theory of fundamental physics.

Appendix A. Cosmological Thermodynamic Constraint

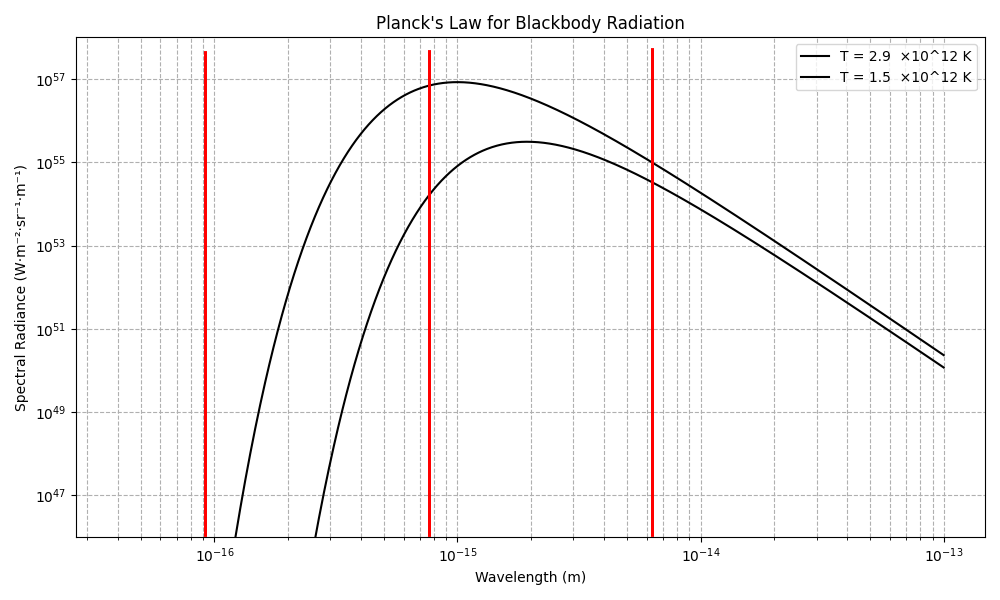

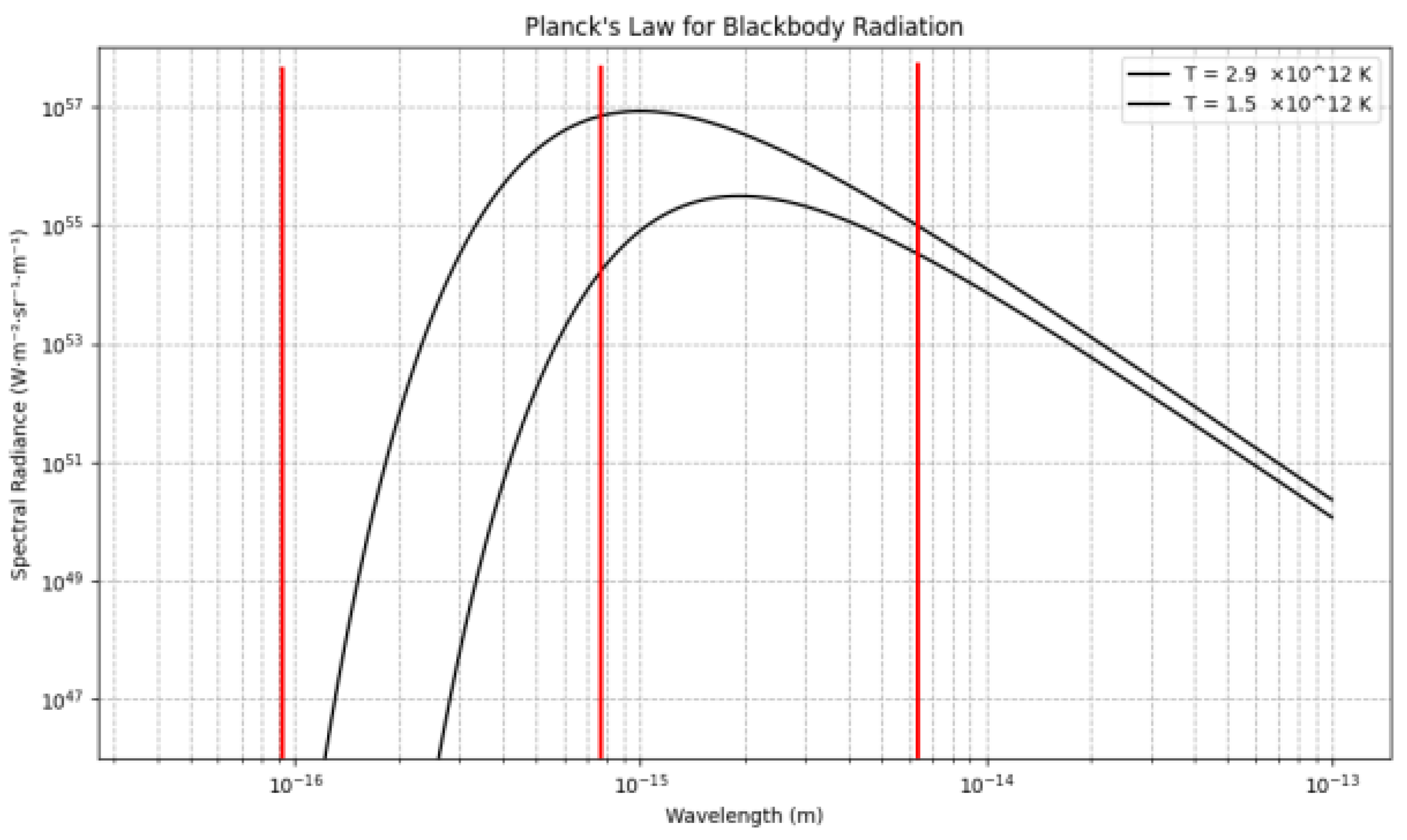

We reproduce here the core of a previous analysis exploring a thermodynamic justification for the 18-layer limit based on the conditions during the hadronization epoch. Lattice QCD and heavy-ion collision data place the temperature of the quark-gluon plasma (QGP) at this critical transition between

and

K [

2,

3].

The shortest wavelength required to build the

energy level in the Lockyer model is derived from the rationalized Compton wavelength of the electron (

m), scaled by the geometric factor

and a correction factor

:

This yields m for the 18th layer.

Figure A1 illustrates the spectral radiance of a blackbody at the estimated bounds of the hadronization temperature range. The wavelength lies within the high-energy tail of these spectra. This indicates that building the proton to its 18th layer required harnessing the scarce, highest-energy photons available in the primordial plasma. This photon scarcity naturally limited the proton’s growth, making the 18-layer configuration the most probable outcome during hadronization. In contrast, the wavelength required for a 24th layer ( m) falls entirely outside the available spectrum at these temperatures.

While this argument aligns the Lockyer model with standard cosmology, it does not constitute a fundamental physical limit, as it relies on a specific historical condition. The main text of this paper addresses this by proposing a fundamental limit arising from the anisotropic structure of space itself.

Figure A1.

Planck spectrum at high and low temperature estimates corresponding to the hadronization epoch. Vertical lines indicate the shortest wavelength required for a proton with 12, 18, and 24 levels, respectively.

Figure A1.

Planck spectrum at high and low temperature estimates corresponding to the hadronization epoch. Vertical lines indicate the shortest wavelength required for a proton with 12, 18, and 24 levels, respectively.

References

- T. N. Lockyer, Vector Particle Physics, TNL Press, 1992 ISBN: 0963154605.

- Aoki, Y. , et al. (2006). The order of the quantum chromodynamics transition predicted by the standard model of particle physics. ( 443, 675–678. [PubMed]

- Adams, J. , et al. (2005). Experimental and theoretical challenges in the search for the quark-gluon plasma: The STAR Collaboration’s critical assessment of the evidence from RHIC collisions. Nuclear Physics A.

- Fukuda, Y. (Super-Kamiokande Collaboration). Evidence for oscillation of atmospheric neutrinos. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1562; 81. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, Q. R. (SNO Collaboration). Direct evidence for neutrino flavor transformation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 0113; 89. [Google Scholar]

- Furne Gouveia, G. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Furne Gouveia, G. E: The Multiverse as the Source of Anisotropy, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sabti, N. , Muñoz, J. B., & Kamionkowski, M. (2024). Cosmic Inconsistencies: JWST Anomalies and HST Perspectives. Physical Review Letters.

- Glazebrook, K. , Nanayakkara, T., Kawinwanichakij, L., et al. (2025). ‘Beyond what’s possible’: new JWST observations unearth mysterious ancient galaxies. Nature.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).