Submitted:

27 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

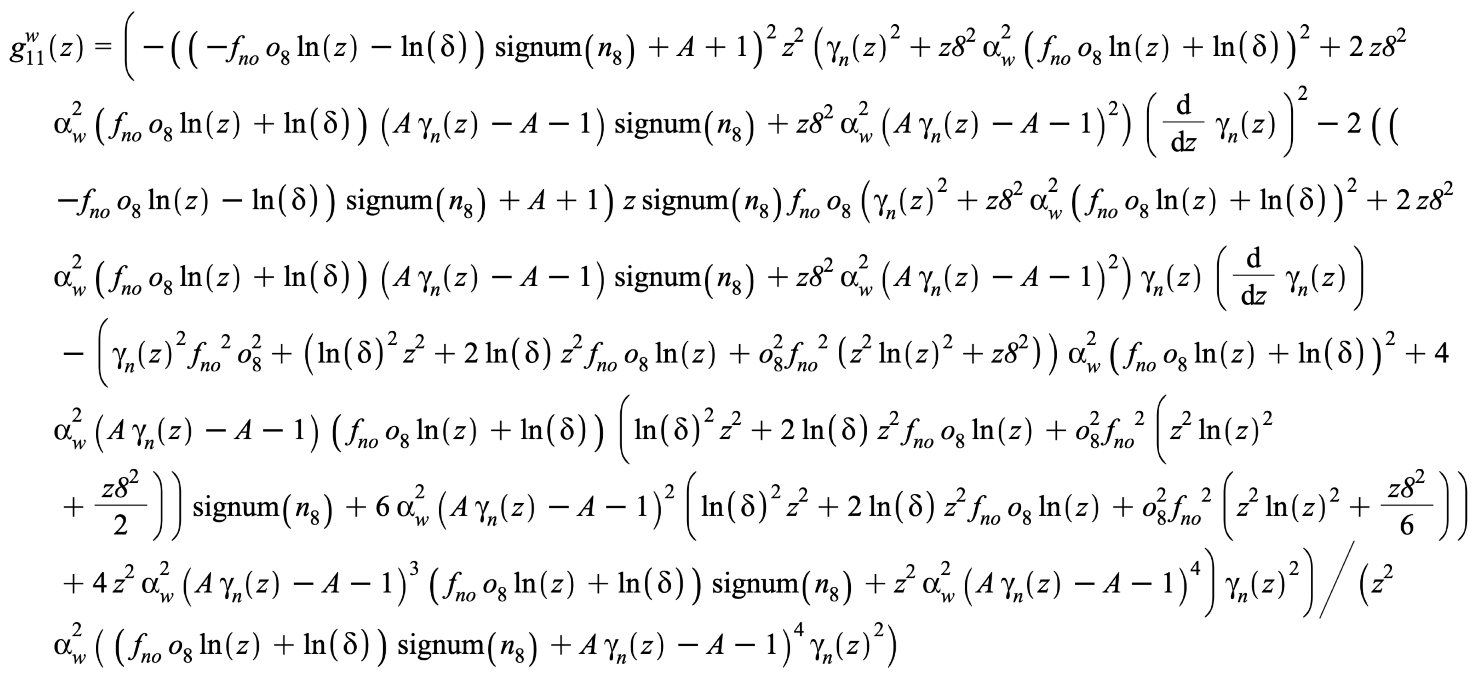

2. Methods/Model

2.1. Embedding and Container Space

2.2. Angular Momentum of a Stable Excitation in a Compactified Dimension

2.3. The Electric Interaction – Dimension 7

2.4. The Strong Interaction – Dimensions 4, 5, and 6

2.5. The Weak Interaction – Dimensions 8 and 9

2.6. The Undisturbed Cylinder Radii

2.7. The Particle Mass from Strong, Electric, and Weak Interactions

2.8. Masses Solely Dependent on the Weak Sector

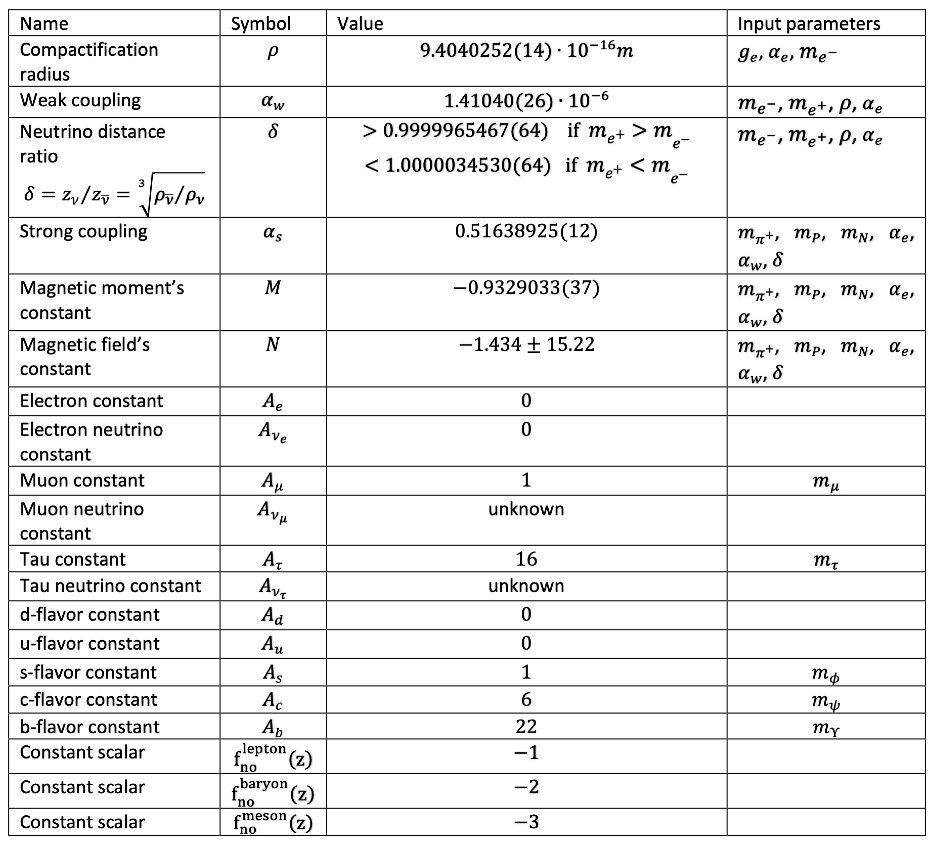

3. Results - Model’s Calculated Values

3.1. Calculation of the Model’s Constants

3.1.1. The Compactification Radius

3.1.2. The Weak Coupling and the Neutrino Distribution Ratio

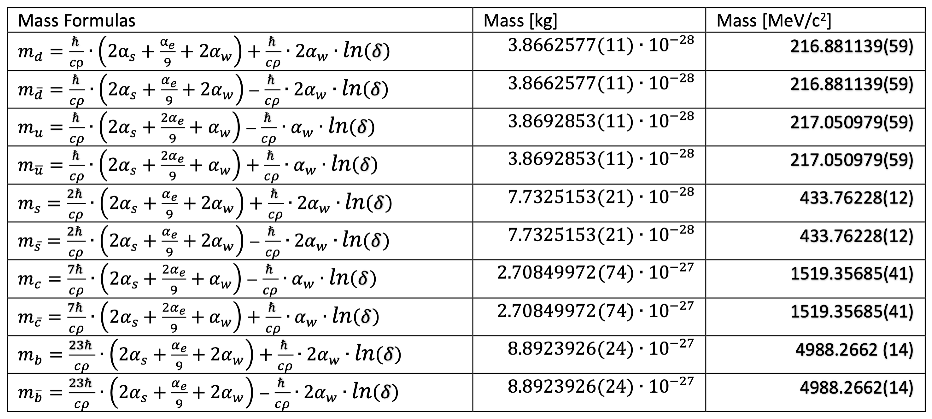

3.1.3. Hadron Mass Formulas

- For baryons consisting of a mixture of u-like (u, c, t) and d-like (d, s, b) quarks, the non-flipped quarks always represent a u-d-like combination.

- In case of a baryon consisting of a u-d-mixture built of three different quark species, there always exist two combinations with a different quark flipped. These are baryons with identical excitation numbers but a dissimilar mass.

- For those baryons consisting of purely u- or d-like quarks the non-flipped quark pair consists of different flavors.

3.1.4. Mass Formulas for the Proton and Neutron

3.1.5. Evaluation of Field Multipliers and Strong Coupling Constant

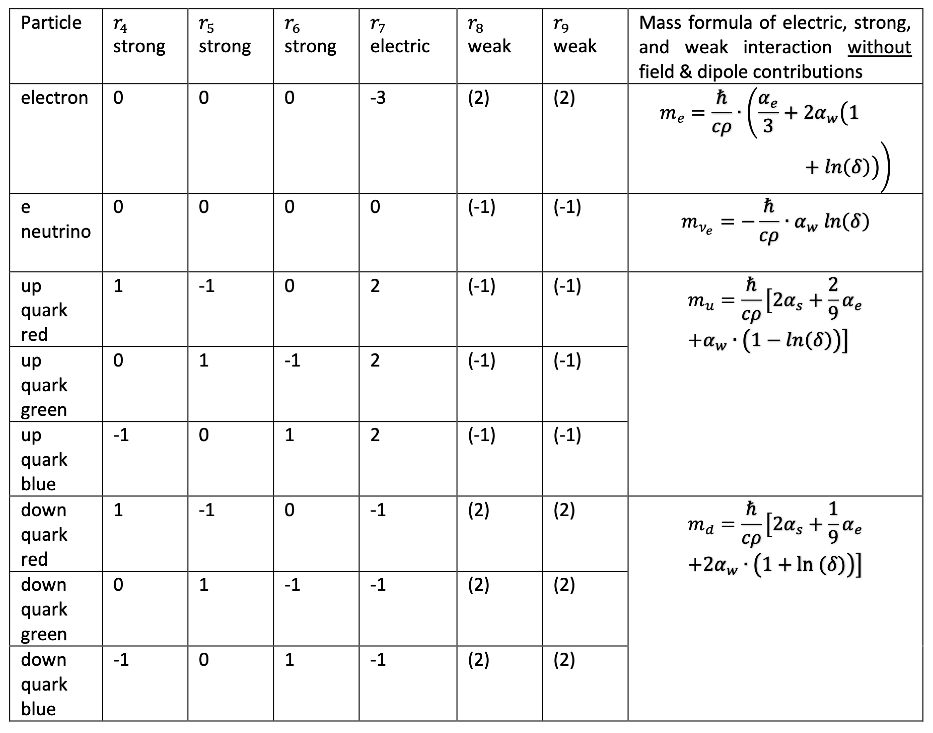

3.2. Particle Identification

- A quark carries one of the three colors: red, green, or blue, along with its respective excitation numbers.

-

The electric excitation number is:

- -

- for a down quark

- -

- for an up quark

- -

- for an electron

- Each excitation number contributes a spin of times the excitation number. To ensure an overall spin of , the weak excitations are adjusted accordingly.

- A neutrino consists exclusively of weak excitations and is described as a superposition of weak excitation states. Its excitation number, formally written as , is the same as the weak excitation contribution of a u-quark (see Table 3).

3.2.1. Higher-Generation Particles and Antiparticles

3.2.2. Excitation Numbers of Photons and Gluons

3.2.3. Summary of Gauge Bosons

3.2.4. Mass Generation via Compactified Dimensions

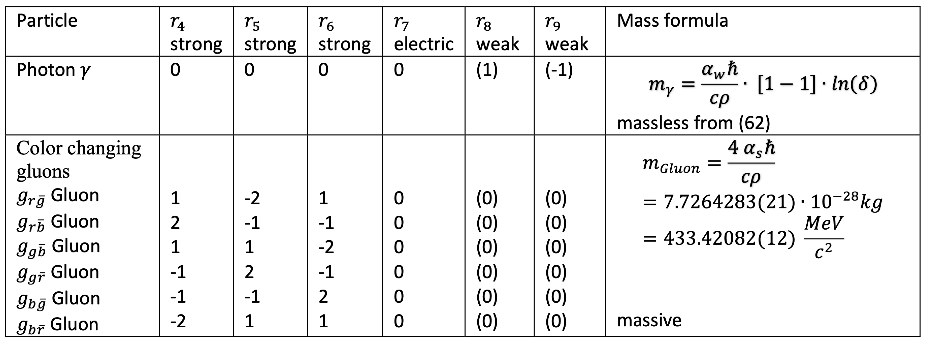

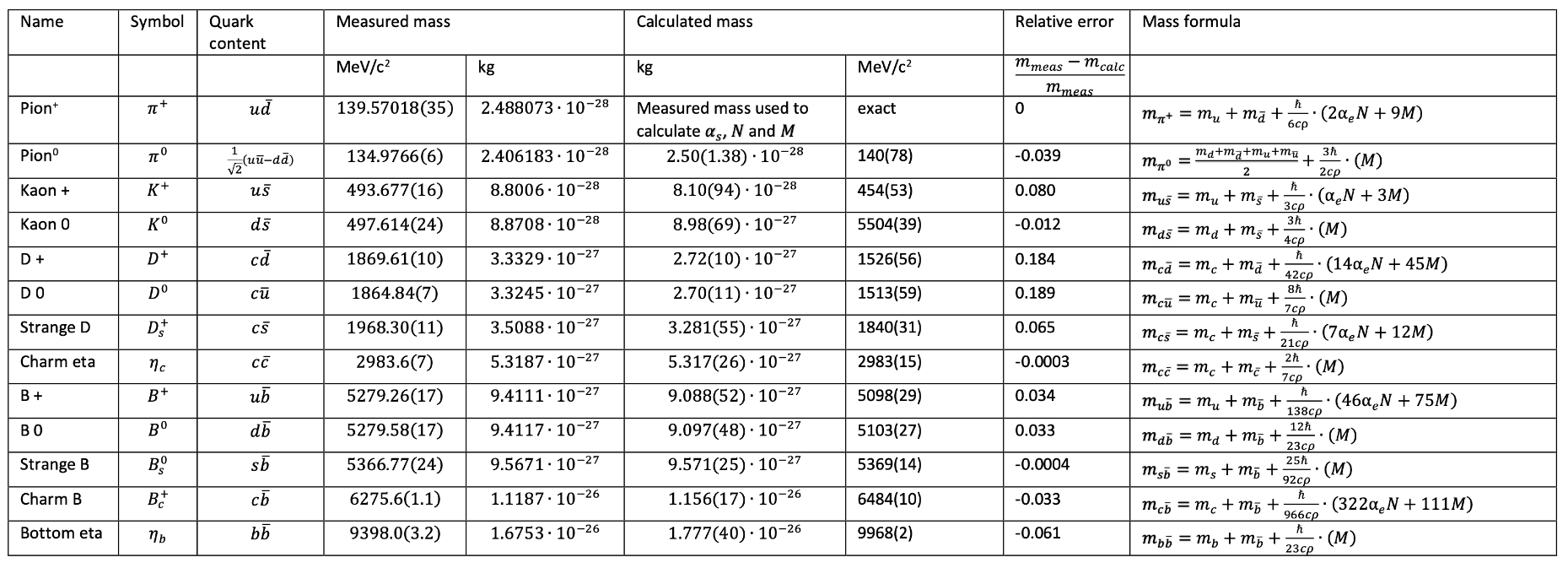

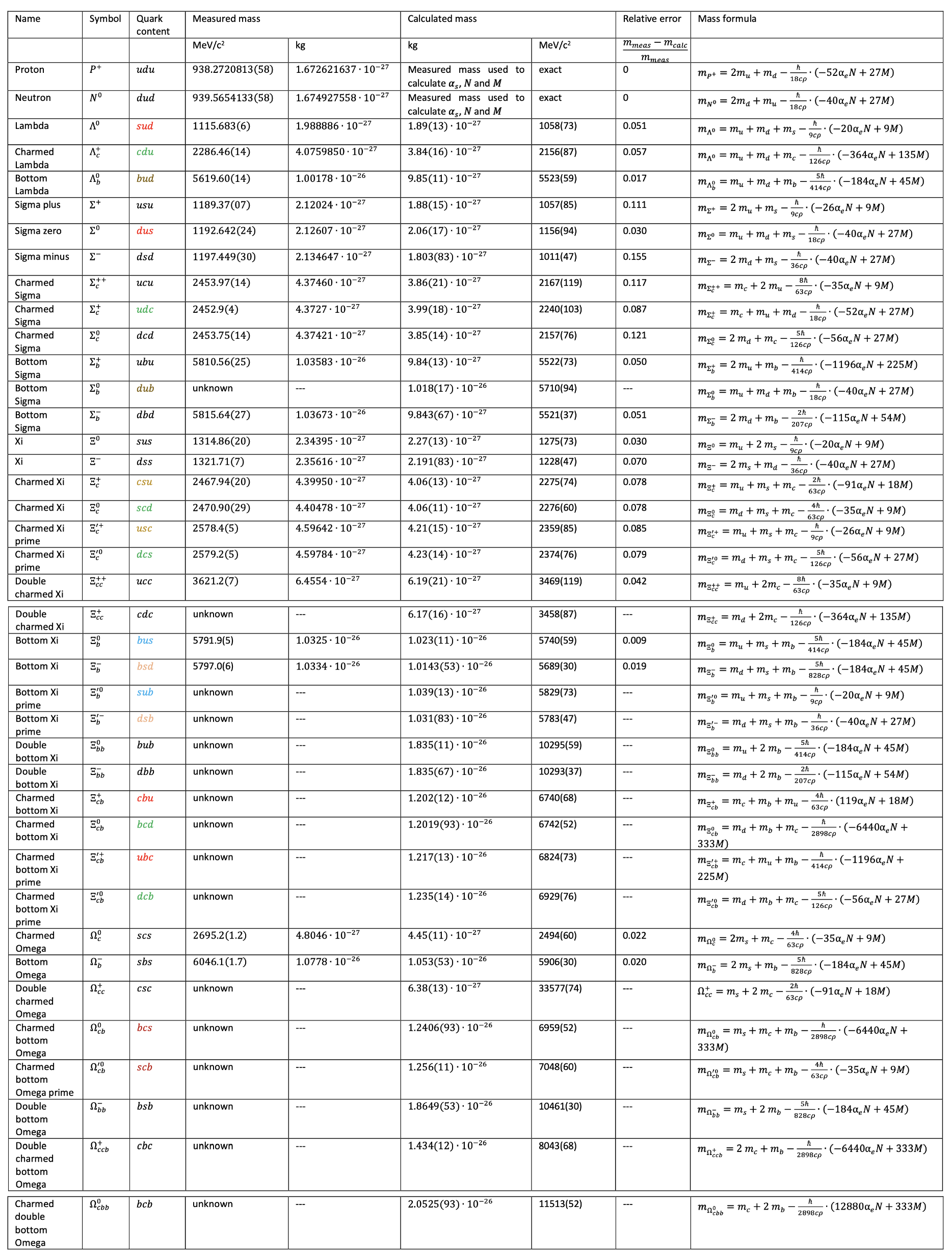

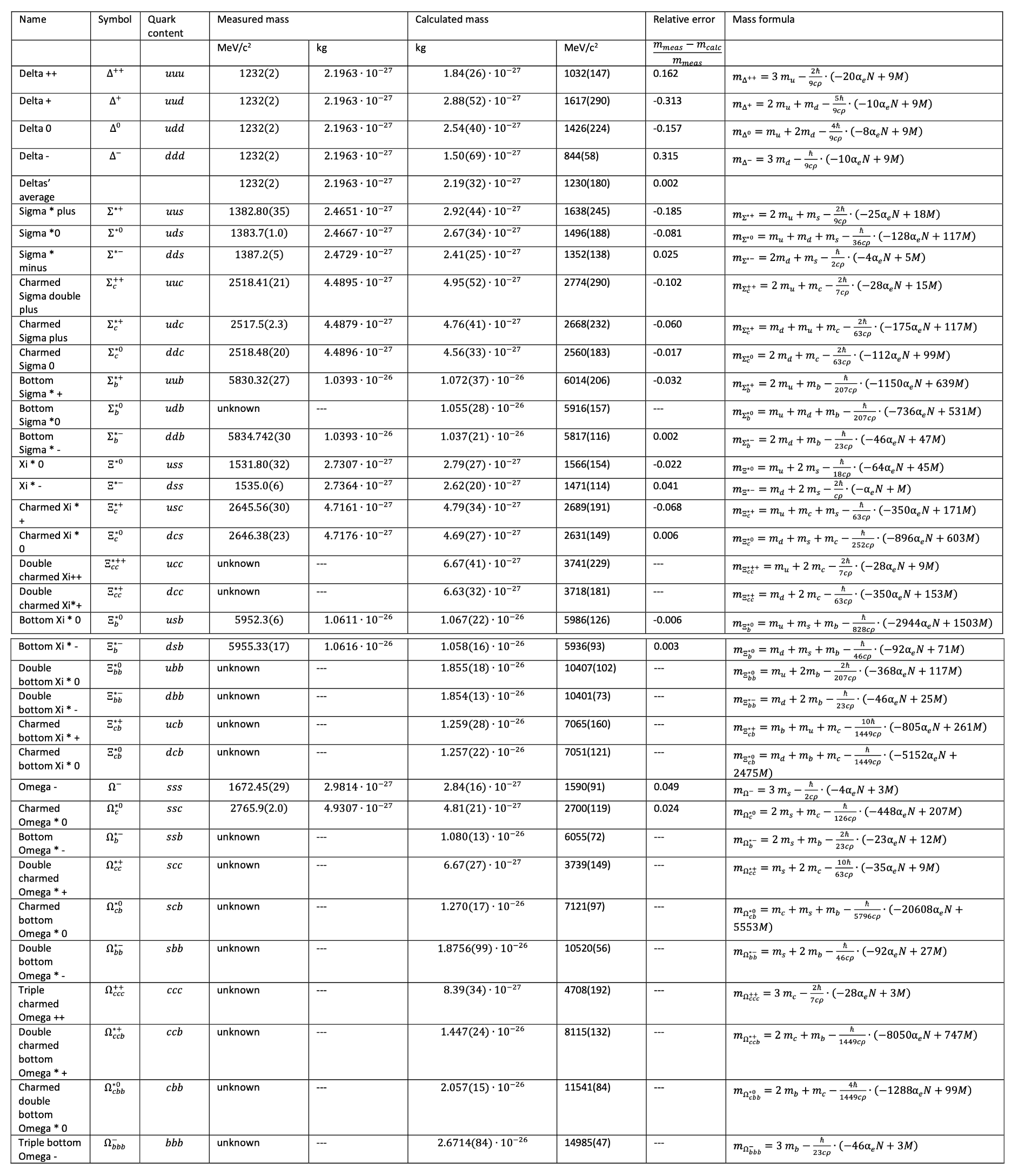

3.3. Hadron Masses

- Particle name and symbol

- Quark content

- Measured and calculated masses (in and )

- Standard deviations

- Relative error

- Mass formula used for the calculation

3.3.1. Meson Masses

3.3.2. Baryon Masses

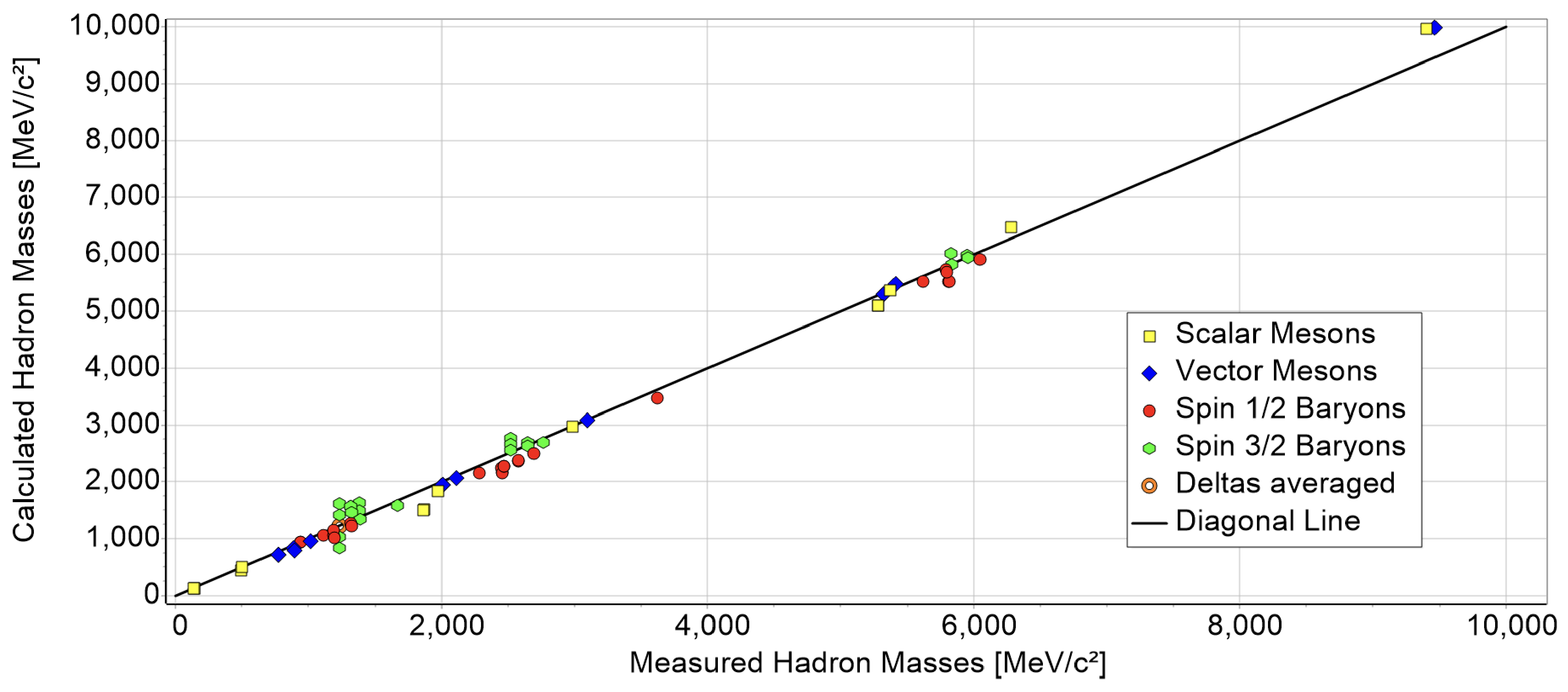

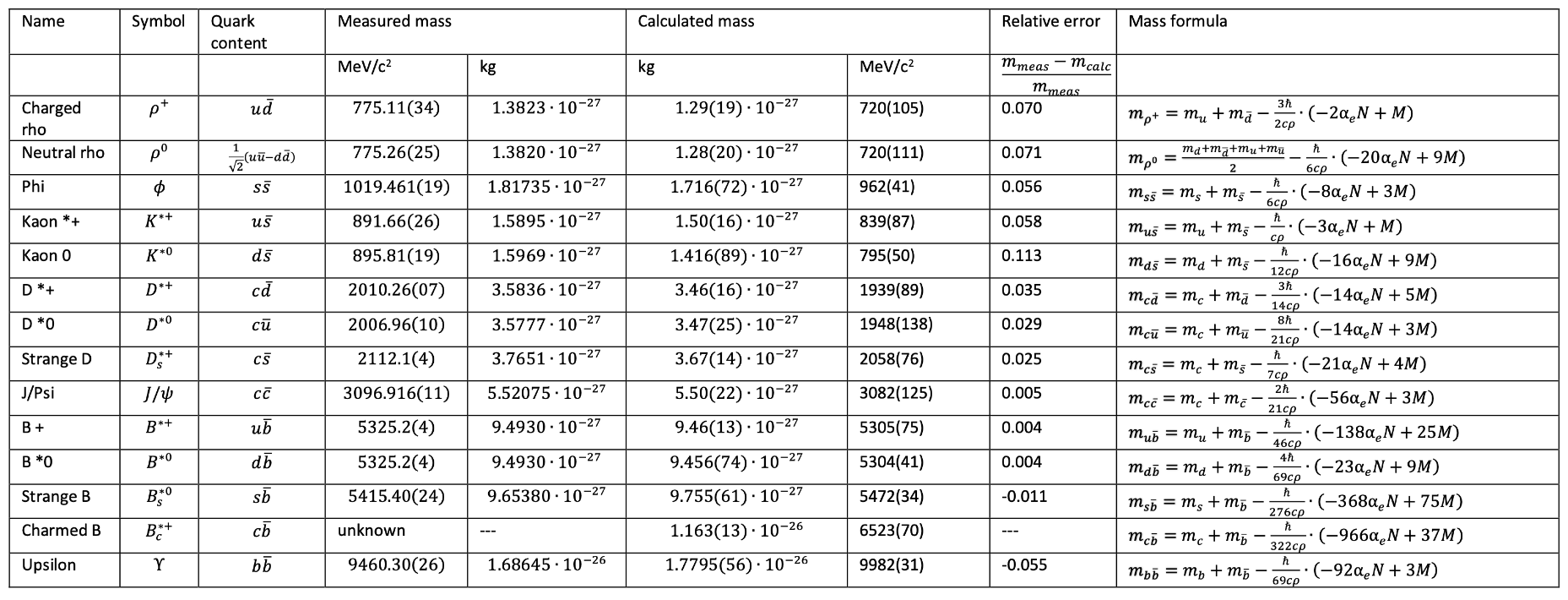

3.4. Correlation Between Measured and Calculated Hadron Masses

3.5. Sterile Dirac Particles

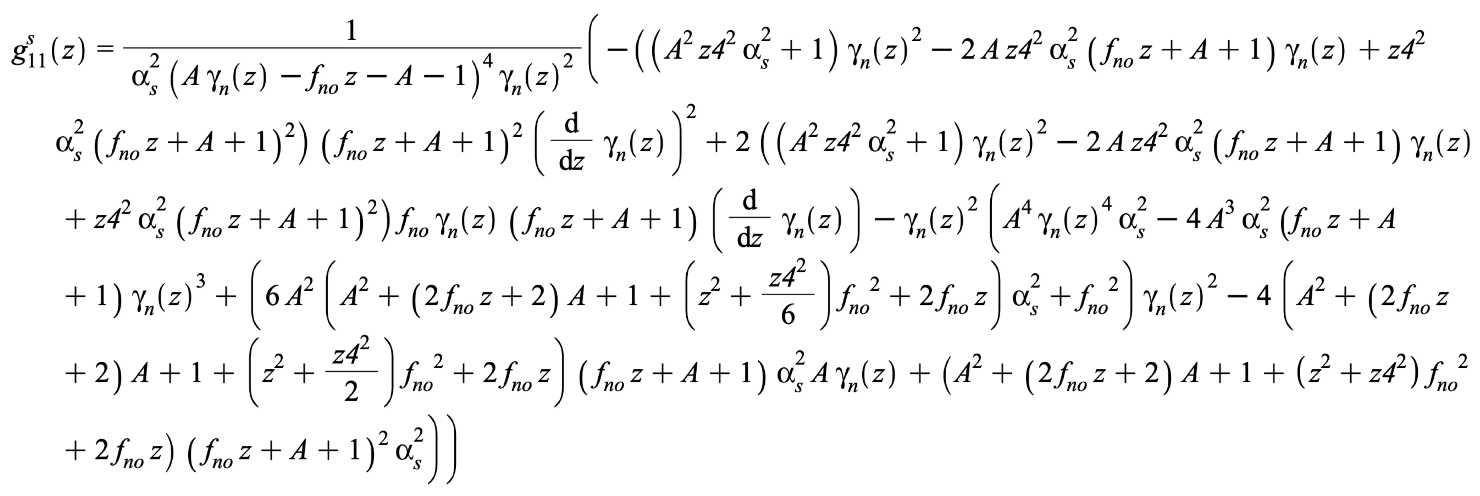

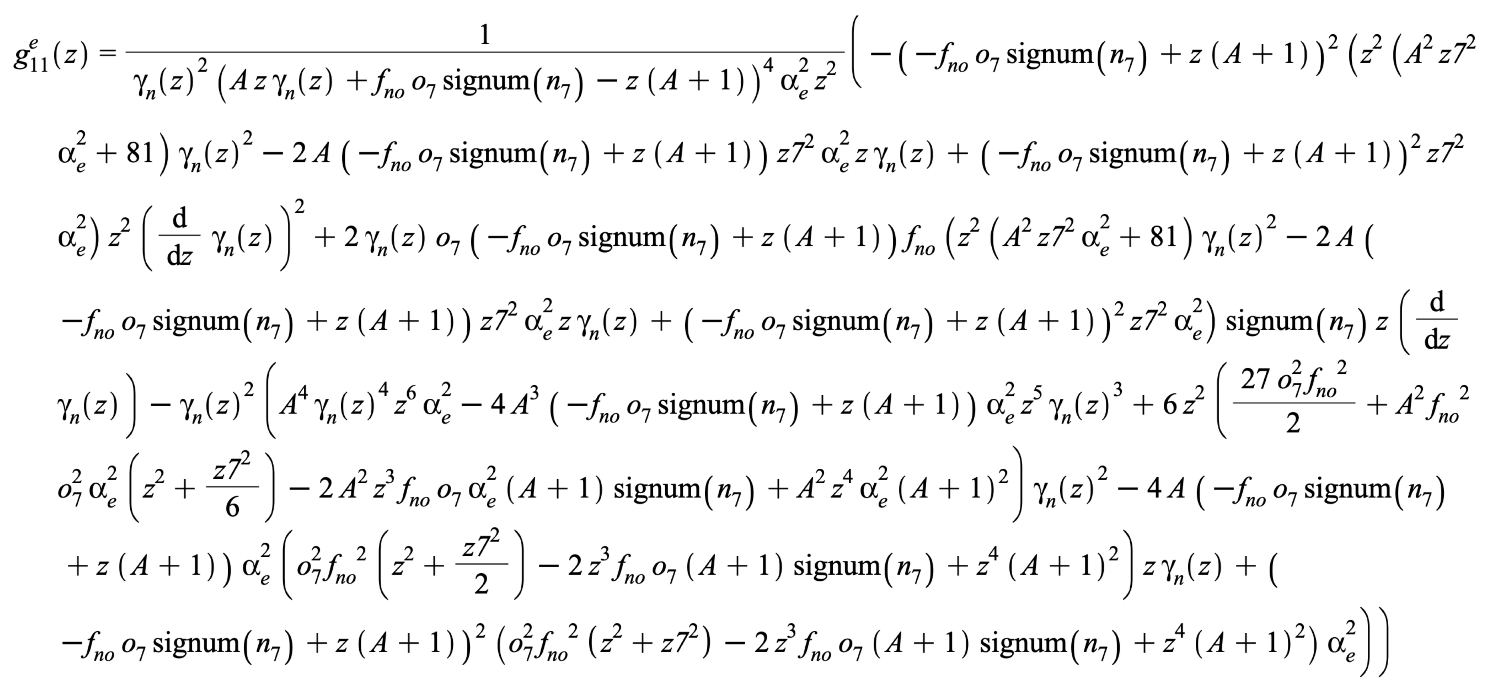

3.6. Calculation of Particle Acceleration and Force

3.7. The Constant Scalar

3.8. Coulomb Force Between Two Slowly Moving Charges

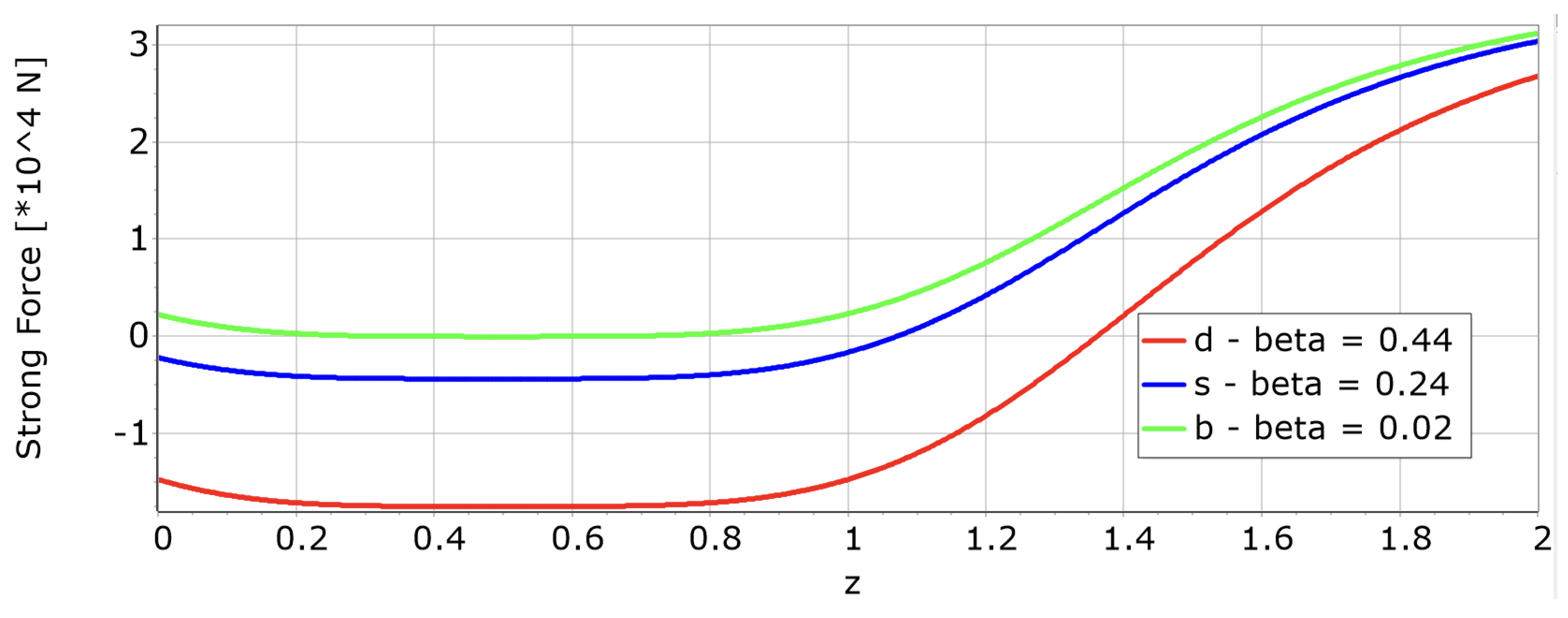

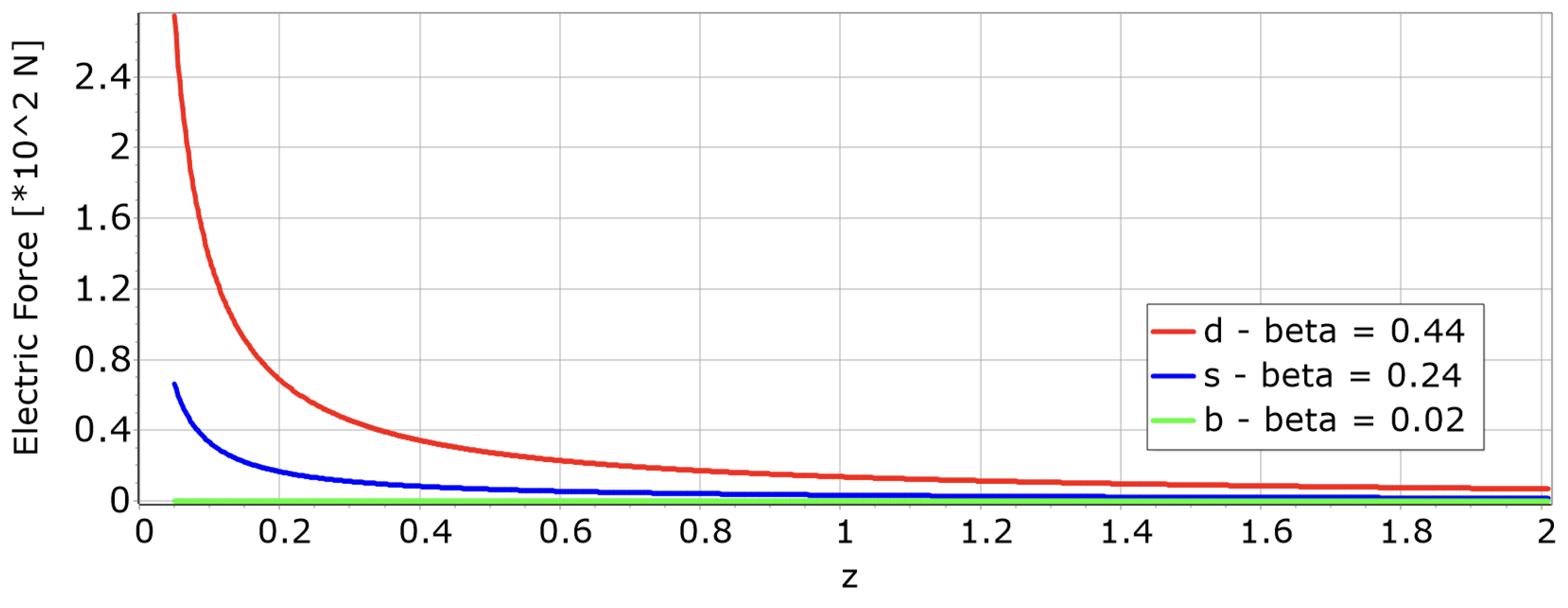

3.9. Force Calculations and Asymptotic Behavior

3.9.1. Key Results on Force Strengths

-

Strong Force:

- -

- Predominant within hadrons.

- -

-

Attractive Forces:

- *

- Baryons: Exerts at for d- and u-quarks, much lower for other quarks.

- *

- Mesons: Displays at per compactified dimension for d- and u-quarks, considerably weaker for other quarks.

- -

-

Repulsive Force characteristics occur for:

- *

- (baryons).

- *

- (mesons).

-

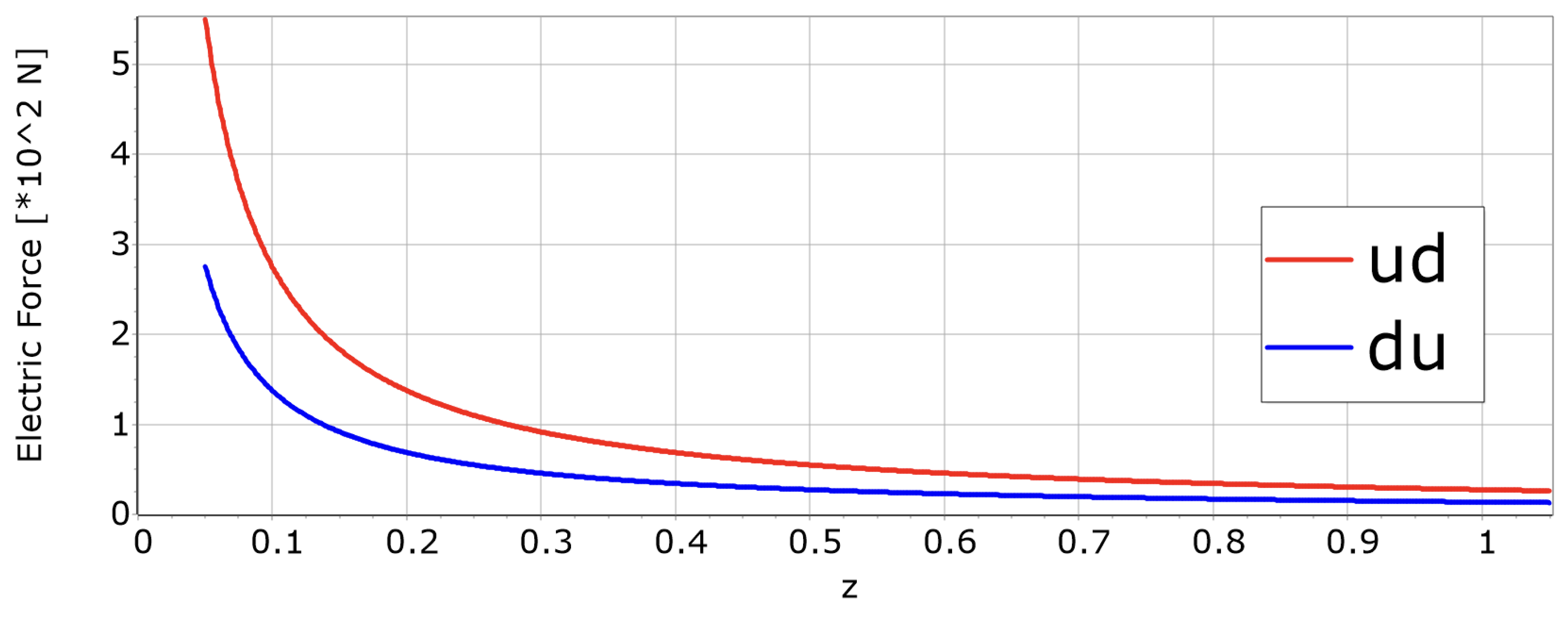

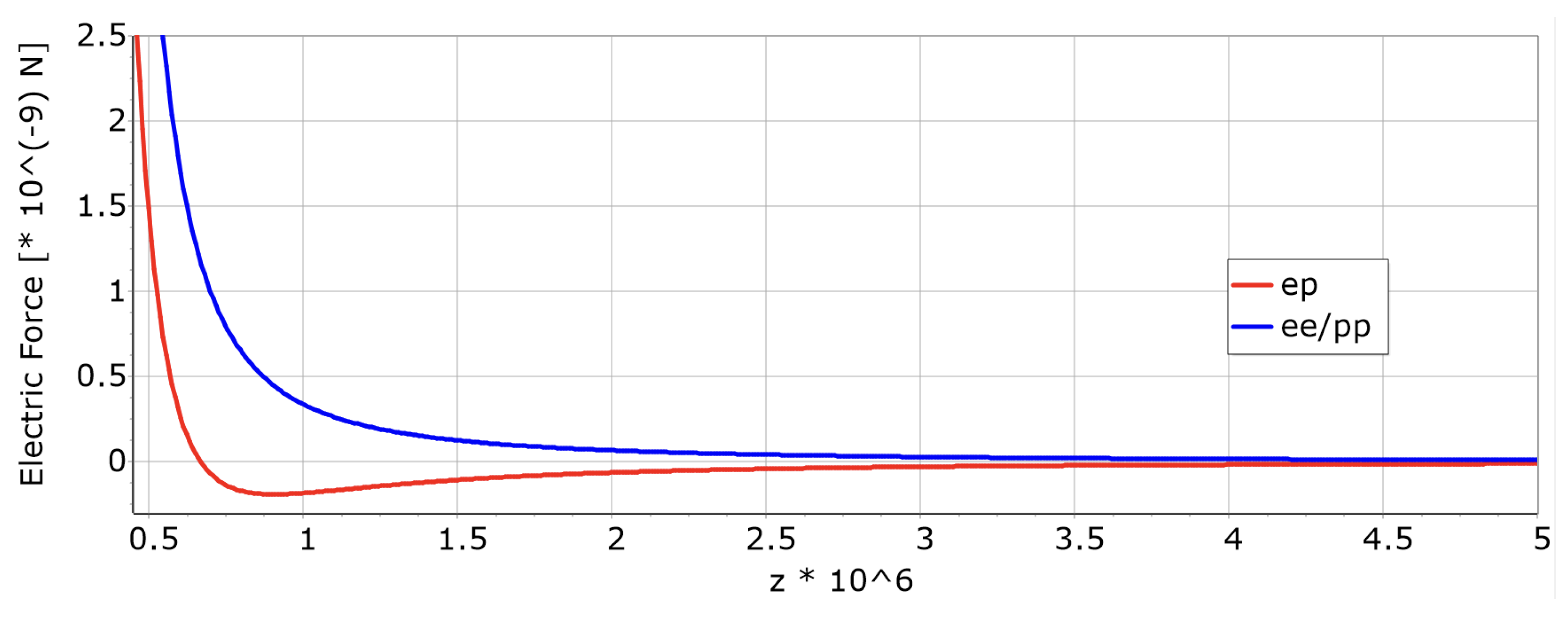

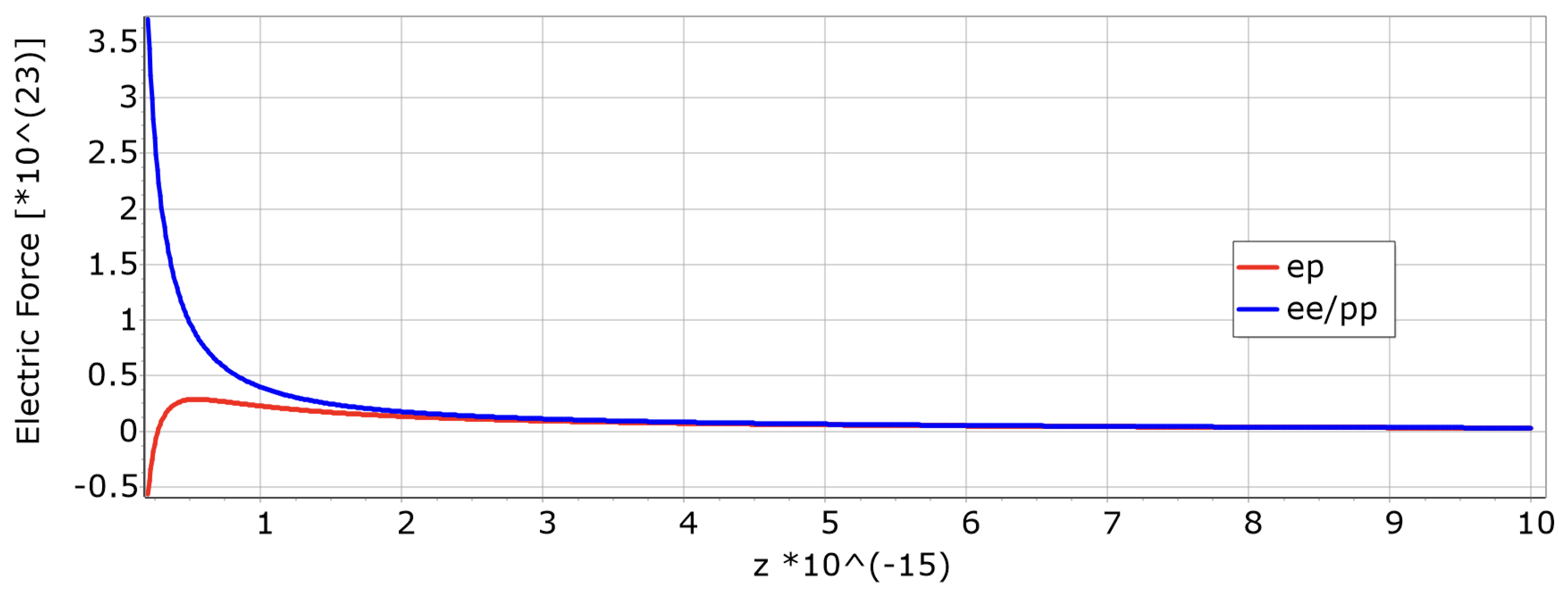

Electric force:

- -

- Inside hadrons: when .

- -

- At the value , the force surpasses .

- -

- No matter the charge configuration, the force is consistently repulsive over the range , which significantly relies on the particles’ speed. For instance, in the case illustrated by Figure 6 and Figure 7, involving a collision with an invariant mass of leading to a velocity of , the range is . However, deceleration was not taken into account, hence, attraction will commence sooner.

-

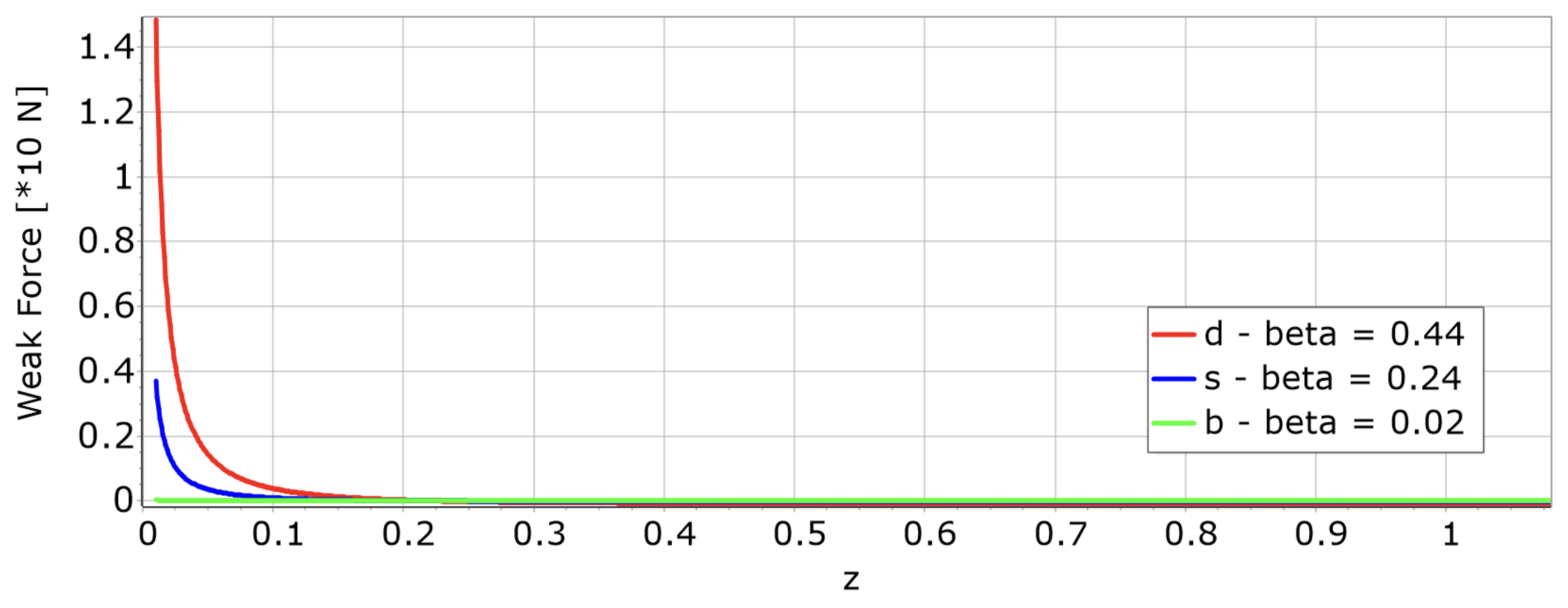

Weak force:

- -

- when .

- -

- when .

- -

- The force is repulsive if the charge signs differ, and otherwise attractive.

3.9.2. Asymmetric Forces in Electric and Weak Interactions of -Hadrons

3.9.3. Particle Transformation in Collision Processes

4. Discussion

- One dimension for time

- Three standard spatial dimensions

- Six compactified dimensions, each shaped like perpendicular cylinders.

- Excitation energies

- Potential energies

- Contributions from magnetic fields and dipoles

4.1. Hadron Masses

- Proton (): 31%

- Neutron (): 31%

- Lambda (): 18%

- Bottom Xi (): 2%

- Charged rho (): 40%

- Upsilon (): 0.06%

4.2. Summarizing the Fundamental Constants

- The compactification radius:

- The weak coupling constant:

- The strong coupling constant:

- The neutrino distribution ratio:

- The constant scalar:

- The flavor constants:

- Electron mass

- Magnetic moment

4.3. Force Calculations and Metric Tensors

4.4. Two Possible Laboratory Experiments and One Astronomical Measurement to Assess the Model

4.4.1. Creation of Dark Matter

4.4.2. Nucleon’s Random Walk

4.4.3. Decreasing Strength of Dark Energy

4.5. Open Questions

4.6. Future Applications

5. Conclusion

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Statistical Error Analysis

Appendix A.2. Parameters Calculated Within the Model

Appendix A.3. Parameters from Literature Used in the Calculations

| Particle | Symbol | Mass (kg) | Mass (MeV/) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electron/Positron | e | ||

| Muon | |||

| Tau | |||

| Pion+ | |||

| Proton | P | ||

| Neutron | N | ||

| Phi Meson | |||

| J/Psi Meson | |||

| Upsilon Meson |

| Constant | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Speed of light | c | 299792458 m/s |

| Reduced Planck constant | Js | |

| Electron’s spin g-factor | ||

| Electric coupling constant |

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Coordinates and Velocities Within the Ten Dimensions

Appendix B.2. Lorentz Factors of Strong, Electric, and Weak Interactions at Their Fixed Points

Appendix B.3. The Metric Tensor

Appendix C. Magnetism

References

- Goldberg, D. The standard model in a nutshell; Princeton University Press, 2017.

- Langacker, P. The standard model and beyond; Taylor & Francis, 2017.

- Thomson, M. Modern particle physics; Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Vergados, J.D. The standard model and beyond; World Scientific, 2017.

- Bettini, A. Introduction to elementary particle physics; Cambridge University Press, 2024.

- Griffiths, D.J. Introduction to elementary particles. Physics textbook, 2010.

- Cottingham, W.N.; Greenwood, D.A. An introduction to the standard model of particle physics; Cambridge university press, 2007.

- Jaeger, G. Exchange forces in particle physics. Foundations of Physics 2021, 51, 13. [CrossRef]

- Schwinger, J. On quantum-electrodynamics and the magnetic moment of the electron. Physical Review 1948, 73, 416. [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, T.; Hayakawa, M.; Kinoshita, T.; Nio, M. Tenth-order electron anomalous magnetic moment: Contribution of diagrams without closed lepton loops. Physical Review D 2015, 91, 033006. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Abdalla, E.; Atrio-Barandela, F.; Pavon, D. Dark matter and dark energy interactions: theoretical challenges, cosmological implications and observational signatures. Reports on Progress in Physics 2016, 79, 096901. [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Quantum gravity; Cambridge university press, 2004.

- Einstein, A. Die Grundlagen der allgemeinen Relativitatstheorie. Annalen der Physik 1916, 49, 769.

- Weinberg, S. Cosmology; OUP Oxford, 2008.

- Kaluza, T. Zum unitätsproblem der physik. Sitzungsber. Preuss. Akad. Wiss. Berlin (Math. Phys.) 1921, 1921, 966–972.

- Kaluza, T. On the problem of unity in physics. Unified Field Theories of> 4 Dimensions 1983, p. 427.

- Klein, O. Quantentheorie und fünfdimensionale Relativitätstheorie. Zeitschrift für Physik 1926, 37, 895–906.

- Klein, O. The atomicity of electricity as a quantum theory law. Nature 1926, 118, 516–516. [CrossRef]

- Appelquist, T.; Chodos, A.; Freund, P.G.O. Modern Kaluza-Klein Theories; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc., 1987.

- Wesson, P. Space-time-matter: modern Kaluza-Klein theory 1999.

- Wesson, P.S.; Overduin, J.M. Principles of Space-Time-Matter: Cosmology, Particles and Waves in Five Dimensions; World Scientific, 2018.

- Witten, E. String theory dynamics in various dimensions. Nuclear Physics B 1995, 443, 85–126. [CrossRef]

- Zwiebach, B. A first course in string theory; Cambridge university press, 2004.

- Polchinski, J. String Theory: Volume 1: An Introduction to the Bosonic String; Vol. 1, Cambridge Monographs on Mathematical Physics, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1998. [CrossRef]

- Urbanowski, K. Decay law of relativistic particles: quantum theory meets special relativity. Physics Letters B 2014, 737, 346–351. [CrossRef]

- DeGrand, T.; Jaffe, R.; Johnson, K.; Kiskis, J. Masses and other parameters of the light hadrons. Physical Review D 1975, 12, 2060. [CrossRef]

- Palazzi, P. Particles and shells. arXiv preprint physics/0301074 2003.

- Carnal, O.; Mlynek, J. Young’s double-slit experiment with atoms: A simple atom interferometer. Physical review letters 1991, 66, 2689. [CrossRef]

- Wiechert, E. Elektrodynamische elementargesetze. Annalen der Physik 1901, 309, 667–689. [CrossRef]

- Ishii, N.; Aoki, S.; Hatsuda, T. Nuclear force from lattice QCD. Physical review letters 2007, 99, 022001. [CrossRef]

- Aoki, S.; Hatsuda, T.; Ishii, N. Theoretical foundation of the nuclear force in QCD and its applications to central and tensor forces in quenched lattice QCD simulations. Progress of theoretical physics 2010, 123, 89–128. [CrossRef]

- Schröder, Y. The static potential in QCD to two loops. Physics Letters B 1999, 447, 321–326. [CrossRef]

- Anzai, C.; Kiyo, Y.; Sumino, Y. Static QCD potential at three-loop order. Physical review letters 2010, 104, 112003. [CrossRef]

- A Zyla, P.; M Barnett, R.; Beringer, J.; Dahl, O.; D Dwyer, A.; D Groom, E.; Lin, C.J.; S Lugovsky, K.; Pianori, E.; D Robinson, J. Review of particle physics (RPP 2020). PROGRESS OF THEORETICAL AND EXPERIMENTAL PHYSICS 2020, 2020, 1–2093.

- Tiesinga, E.; Mohr, P.J.; Newell, D.B.; Taylor, B.N. CODATA recommended values of the fundamental physical constants: 2018. Journal of physical and chemical reference data 2021, 50. [CrossRef]

- R., N. Coupling Constants for the Fundamental Forces, 2025.

- Berends, F.A.; Kleiss, R. Distributions for electron-positron annihilation into two and three photons. Nuclear Physics B 1981, 186, 22–34. [CrossRef]

- Besson, D.; Henderson, S.; Pedlar, T.; Cronin-Hennessy, D.; Gao, K.; Gong, D.; Hietala, J.; Kubota, Y.; Klein, T.; Lang, B. Measurement of the direct photon momentum spectrum in Υ (1 S), Υ (2 S), and Υ (3 S) decays. Physical Review D—Particles, Fields, Gravitation, and Cosmology 2006, 74, 012003.

- Wikipedia, t.f.e. List of mesons. Wikipedia 2025.

- Wikipedia, t.f.e. List of baryons. Wikipedia 2025.

- Hestenes, D. The zitterbewegung interpretation of quantum mechanics. Foundations of Physics 1990, 20, 1213–1232. [CrossRef]

- Yau, S.T.; Nadis, S.J. The shape of inner space: String theory and the geometry of the universe’s hidden dimensions; Il Saggiatore, 2010.

- Misner, C.W.; Thorne, K.S.; Wheeler, J.A. Gravitation; W. H. Freeman and company: San Francisco, 1973; p. 1088.

- De Broglie, L. The reinterpretation of wave mechanics. Foundations of physics 1970, 1, 5–15.

- Aker, M.; Altenmüller, K.; Arenz, M.; Babutzka, M.; Barrett, J.; Bauer, S.; Beck, M.; Beglarian, A.; Behrens, J.; Bergmann, T. Improved upper limit on the neutrino mass from a direct kinematic method by KATRIN. Physical review letters 2019, 123, 221802. [CrossRef]

- Vikhlinin, A.; Kravtsov, A.; Burenin, R.; Ebeling, H.; Forman, W.; Hornstrup, A.; Jones, C.; Murray, S.; Nagai, D.; Quintana, H. Chandra cluster cosmology project III: cosmological parameter constraints. The Astrophysical Journal 2009, 692, 1060.

- Xia, F.; Liu, J.; Nie, H.; Fu, Y.; Wan, L.; Kong, X. Random Walks: A Review of Algorithms and Applications. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computational Intelligence 2020, 4, 95–107. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. Über die von der molekularkinetischen Theorie der Wärme geforderte Bewegung von in ruhenden Flüssigkeiten suspendierten Teilchen. Annalen der physik 1905, 4. [CrossRef]

- Alpher, R.A.; Bethe, H.; Gamow, G. The origin of chemical elements. Physical Review 1948, 73, 803.

- Fields, B.D., Big Bang Nucleosynthesis: Nuclear Physics in the Early Universe. In Handbook of Nuclear Physics; Springer, 2023; pp. 3379–3405.

- Planck, P.C. results. VI. Cosmological parameters. arXiv preprint arXiv:1807.06209 2018, 34.

- Collaboration, D.; Adame, A.G.; Aguilar, J.; Ahlen, S.; Alam, S.; Alexander, D.M.; Alvarez, M.; Alves, O.; Anand, A.; Andrade, U.; et al. DESI 2024 VI: Cosmological Constraints from the Measurements of Baryon Acoustic Oscillations, 2024, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/2404.03002]. [CrossRef]

- Gamow, G. Physics and Feynman’s Diagrams. Scientific American 1956.

| unknown | unknown |

| Number of Hadrons | Particle Group | Pearson’s r | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | Scalar Mesons | 0.998 | |

| 13 | Vector Mesons | 0.999 | |

| 24 | Spin- Baryons | 0.999 | |

| 20 | Spin- Baryons | 0.998 |

| Quark | Mass | Flavor Constant A | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| d | 216.9 | 0.44 | 1.112 | 0 |

| u | 217.1 | 0.44 | 1.112 | 0 |

| s | 433.8 | 0.24 | 1.029 | 1 |

| c | 1519.4 | 0.07 | 1.002 | 6 |

| b | 4988.3 | 0.02 | 1.000 | 22 |

| n | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||

| 2 | ||

| 3 | ||

| 4 | ||

| 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).