1. Introduction

The cerebellum is a suprasegmental integrative center of the brain responsible for the coordination of movements and the implementation of fine motor programs. Despite the existence of fundamental study of the structural organization and connections of the mammalian cerebellum, the essential aspects of its involvement in behavioral activity and cognitive functions are still being studied. The cerebellum of salmon consists of three parts: the

corpus cerebelli (CC), the

valvula cerebelli (VC), extending under the lobes of the optic tectum, and the vestibulo-lateral (caudal) lobe [

1,

2]. The cerebellar cortex occupies the largest part and forms an unpaired dorsal protrusion of the rhombencephalon. The VC is a new structural formation in the evolutionary context of the cerebellum of ray-finned fishes and represents a rostral continuation of the cerebellar cortex into the tectal ventricle [

3]. The vestibulo-lateral lobes of the cerebellum have connections with octavolateral neurons and include the caudal lobe and the paired

eminencia granularis (GrEm) [

4,

5,

6].

The neuronal organization of the cerebellum in teleosts has been previously studied by silver impregnation methods [

3,

8,

9,

10] and by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) methods [

8,

9,

11]. Ultrastructural analysis of neuronal organization and differentiation allows us to formulate recently identified features and developmental trends of the neuronal structures of the fish cerebellum. These data are of particular interest in the context of adult neurogenesis, since the cerebellum of juvenile masu salmon

Oncorhynchus masou [

12] and trout

O. mykiss [

13], like other parts of the salmon brain, is capable of forming new cells during the growth. New cells also form after traumatic injury to the cerebellum in masu salmon

O. masou [

14,

15] and chum salmon

Oncorhynchus keta [

16].

Cerebellar cells originate from various sources, in particular from the neural stem cells (NSCs) located in the dorsal parts of the molecular layer (ML), parenchyma, GrEm, and granular layer (GrL) [

12,

13,

15]. However, to date, there is no consensus on the origin and morphogenesis of most cerebellar cells and the degree of their homology to mammalian cells; for example, basket cells have not been found in teleosts.

It has been reported that the cerebellum of salmon fish has an outer ML containing cells of stellate morphology (SC), dendrites of Purkinje cells (PCs), and parallel fibers (pf) originating from granular cells (GrCs) [

2]. The cells of the ganglion layer (GL) are represented by large projection Purkinje cells, which form a single layer in salmon fish. In the GrL, the main cell type is small granular cells (GrCs), among which there are large Golgi cells (GCs) [

8,

9,

17]. In the opisthocentrid fish

Pholidapus dibowskii, large cells in the GrL of the cerebellum, with bipolar morphology resembling Lugaro cells of higher vertebrates, have been described [

18]. PCs in ray-finned fish form connections only within the cerebellum [

2], whereas external extracerebellar projections are formed by eurydendroid cells (EDCs) located between PCs [

19,

20,

21]. Because of the presence of the EDCs instead of the deep cerebellar nuclei, Purkinje cells do not project beyond the cerebellar cortex but function as interneurons with short axons terminating within the GL [

22,

23].

The details of the neurochemical and ultrastructural architecture of the various interneuron types in the fish cerebellum have not been adequately addressed to date. Information on the features of the synaptic structure and the pattern of the intercellular contacts formed in the cerebellum of salmonids is also scarce, despite the fact that the connections between the cerebellum with various areas of the brain in juvenile trout

O. mykiss [

2] and masu salmon

O. masou [

24] have been studied using diffusion transport methods. Studies conducted on different species of salmonids have proven to be important for understanding the cellular organization and morphogenesis of the cerebellum in teleosts [

25]. In particular, the connections of the cerebellum in masu salmon and trout have been studied experimentally, including in the context of the organization of cholinergic systems [

24,

26]. A comprehensive analysis of the cerebellar connections in salmon using a lipophilic dye (DiI), capable of diffusing along cell membranes in a fixed brain, made it possible to tracke the similarity in the organization of the main extracerebellar projections to various parts of the brain [

2,

24].

Morphological portraits of neurons and glial cells of the cerebellum illustrate in detail both general and specific features for each type. These features are determined by clear structural parameters, including the size of the cell body, layer-by-layer and spatial localization of perikarya, size, density, and distribution pattern of the dendritic spine apparatus, comparative geometry of dendritic fields, polymorphism of axon arborizations, and the type of synaptic terminals [

27]. The aim of this work was to study the ultrastructural organization of the cerebellum of juvenile chum salmon

O. keta in the context of interneuron composition, neuro-glial relationships, homeostatic neurogenesis, and synaptic plasticity.

3. Discussion

The conducted studies allowed us, for the first time, to identify the features of the ultrastructural cerebellum organization in juvenile chum salmon,

O. keta, within the framework of the traditional structural plan of the bony fish cerebellum. Three anatomical zones were identified in the juvenile chum salmon cerebellum: the CC (

corpus cerebellum), the VC (

valvula cerebelli) and the GrEm (

eminentia granularis), which included the ML, GrL, and GL [

34]. The conducted studies showed that juvenile chum salmon have a general structural plan of the cerebellum characteristic of other bony fishes [

34,

35]. An ultrastructural analysis of all cerebellar layers revealed the features of the neuronal, synaptic and glial cytoarchitecture, which determine the high mobility, neurogenic activity and behavioral characteristics of juvenile chum salmon. One of the noteworthy observations was the detection of a variety of macro- and microglia in the cerebellum, which distinguishes juvenile chum salmon from other bony fishes and supports previous findings on the mesencephalic tegmentum [

36]. As a result of the ultrastructural study, differences and similarities in the organization of heterogeneous interneuron groups of the cerebellum were found; details of the microcytosculpture of liana-like afferents and glial and non-glial precursors of adult types (aNSPCs) were determined; and astrocytic endocytosis in the area of synaptic contacts of parallel fibers and dendrites of the PC were described in detail.

Studies on fish have shown that, histologically, the cerebellar cortex of teleosts exhibits a much less orderly layered structure compared to the more clearly organized trilayered cortex of tetrapods [

30]. The cerebellar cortex of mammals consists of three layers, including an outer ML with a small number of somatic neurons, a monolayer of Purkinje cells, and a deep GrL consisting mainly of small GrCs [

27]. This distinct layering has been found to be generally characteristic of non-mammalian vertebrates, with the exception of fish and cyclostomes [

3]. These characteristic zones of the cerebellar cortex and their corresponding cell types are significantly more diverse in juvenile chum salmon, which is consistent with data for other fish species [

4,

5]. In particular, in juvenile chum salmon, PCs can be found in the GrL, and GrCs are located laterally to the GL.

Previous studies have shown that teleost fishes lack basket cells [

37]. In our studies on chum salmon, we did not find these cells as well. Therefore, negative feedback loops in the cerebellum are created only by GCs and SCs. The EDCs, found in juvenile chum salmon, apparently replace the deep cerebellar nuclei in terrestrial vertebrates, which is consistent with data on other fishes [

38,

39].

3.1. Features of the Histological Structure and Immunohistochemical Labeling of the DMZ in the Cerebellum of Juvenile Chum Salmon O. keta

It is known that in adult fish, as in mammals and birds, the cerebellum is the largest compared to that in other vertebrates [

30]. Another feature of the fish cerebellum is its high structural diversity, being one of the forms of plasticity [

35,

40]. The histological organization of the DMZ in juvenile chum salmon is characterized by heterogeneity of the cellular composition and includes a few elongated, light-colored cells of the neuroepithelial type, located along the periphery of the DMZ, and numerous dark-colored stellate-like cells, which are aNSPCs and occupy the central part of the DMZ.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) studies of the DMZ features in juvenile masu salmon,

O. masou, showed the presence of PCNA+ and BrdU+ cells, which indicates the proliferative activity of the cells in the intact cerebellum and a significant increase in the number of such cells after injury [

14]. Small, densely stained, stellate-shaped cells were found in the dorsal and ventrolateral regions of the DMZ of juvenile chum salmon,

O. keta (Table). The ultrastructural organization of the DMZ, the main neurogenic region of the juvenile chum salmon cerebellum, was dominated by cells with dense cytoplasm, stellate morphology, and a large, irregularly shaped nucleus, which determines the glial phenotype of the aNSPCs according to [

41]. In contrast to the

Apteronorus leptorhynchus, characterized by the dominance of embryonic-type precursors (NECs) in the cerebellum, the majority of cells in the DMZ in juvenile chum salmon were represented by aNSPCs, which is consistent with data on

Danio rerio [

42]. IHC labeling of glutamine synthetase in the juvenile chum salmon cerebellum showed the presence of immunopositive cells in the DMZ [

16], which supporting the current TEM data on the presence of glial aNSPCs. The results of studies on masu salmon showed the presence of vimentin+ [

15], GFAP+ cells [

14] in the DMZ, which are glial markers and identify adult-type precursors in this region.

The discovery of non-glial precursors in the DMZ of juvenile chum salmon, characterized by rounded shapes, a large, light, round nucleus, and light cytoplasm, was a remarkable finding of this work. Previous studies on masu salmon demonstrated the presence of nestin+ and PCNA+ cells in the cerebellum [

15]. Similar immunolabeling results were obtained for the trout cerebellum [

13]. Although the functions of nestin in the central nervous system are not yet fully understood, it is clear that nestin is an effective marker for studying aNSPCs behavior and nervous system development [

43]. The presence of nestin+ cells in the DMZ and neurogenic zones of the granular eminences (GrEm) in closely related salmonid species, as well as the localization of superficial neurogenic clusters identified in juvenile chum salmon, indicates the persistence of a neotenic structure in the juvenile salmon cerebellum. The phenomenon of embryonization of the salmon brain is confirmed by the detection of non-glial aNSPCs in the juvenile chum salmon cerebellum using TEM and SEM. The results of ultrastructural (TEM) and stereoscopic (SEM) analyses on juvenile chum salmon, along with previously identified nestin+ and PCNA+ cells [

13,

15], suggest that the identified adult-type progenitors represent a population of non-glial progenitors that retain neurogenic activity and contribute to homeostatic growth of the cerebellum in juvenile chum salmon.

3.2. Molecular Layer

3.2.1. Features of the Synaptic Structure of the SCs

Several types of structures, including parallel fibers (pfs), PCs and EDC dendrites, and SCs were found in the ML of the juvenile chum salmon cerebellum. SCs are a relatively small population of cells with multipolar morphology, a small stellate soma, and a large nucleus. According to previous investigations, fish SCs are cells with GABAergic neurotransmission, along with other cerebellar interneurons such as PCs and CGs [

44]. Imaging studies in mice have shown that pfs provide input to SCs which extend axons parallel to pfs and form inhibitory synapses with PC dendrites to modulate pf input [

28]. This suggests that the projections of pfs and SCs play a central role in the integration and processing of incoming information in the mammalian cerebellum [

45]. In studies on juvenile chum salmon, synaptic contacts between SCs and pfs were not detected.

According to ultrastructural data, numerous synaptic structures are formed in the ML of juvenile chum salmon, including one of the largest and most significant synapses in the cerebellum, between pfs and PC dendrites, providing excitatory input to the PCs. For the first time, we identified morphologically heterogeneous synaptic terminals in this region of the ML in juvenile chum salmon (

Figure 4B,C). It is known that PC dendrites extend to the ML, while their somata are located in the GL. Most of the excitatory-type pf synaptic terminals of juvenile chum salmon converge on the dendritic bushes of the PCs, which largely resemble the analogous structure in higher vertebrates and zebrafish,

D. rerio [

28].

The excitatory terminals of the cfs were identified on the PCs bodies of juvenile chum salmon (

Figure 9E); synapses between cf and PC are the second most important synaptic structures in the cerebellum. SEM studies of cfs of juvenile chum salmon showed the presence of numerous terminal thickenings and varicose microcytosculpture (

Figure 7A,B), which most likely correspond to areas of synaptic contacts.

The neural activity of climbing fibers suppresses synaptic transmission from GrC axons through a mechanism known as long-term depression, which is required for motor learning [

46,

47,

48]. In fish, cfs send their axons either to neighboring PCs or to EDCs [

49,

50], while EDCs send efferent axons to other brain areas [

21], forming synapses between PCs [

28,

52]. Some fish PCs also form connections with other PCs. It should be noted that PCs in the lateral CC send direct efferent signals to the vestibular nuclei (cerebello-vestibular tract), which may play a role in early vestibular processing [

53]. Thus, as in the case of GCs, there is a small proportion of PCs that are not involved in intracerebellar connections but represent an efferent cell population.

We observed similar patterns of PCs and EDCs localization, but found no direct synaptic connections between these cells in the juvenile chum salmon cerebellum.

3.2.2. Adult-TYPE NEURAL STEM PROGENITOR CELLS (aNSPCs) in the MOLECULAR (ML) and GRANULAR LAYERS (GrL) of the CEREBELLUM

Compelling evidence for ongoing adult cerebellar neurogenesis has been shown in cypriniformes: zebrafish [

54], the goldfish

Carassius auratus [

55], cichlids

Astatotilapia burtoni [

56], the killifish

Nothobranhius furzeri [

57], the

Oryzias latipes [

58], the electric brown ghost fish

Apteronotus leptorhynchus [

59], and salmonids: the trout

O. mykiss [

13], the chum salmon

O. keta [

16], and the masu salmon

O. masou [

14,

15]. In mammals, evidence of spontaneous adult neurogenesis has been documented for the rabbit cerebellum [

60].

As regards the homeostatic neurogenesis in salmonids, evolutionarily ancient representatives of teleosts, the question as to why neurogenesis continues after embryonic or juvenile stages of development, allowing Pacific salmon to attain substantial body sizes, still remains unanswered [

13,

61,

62]. In the ML of the juvenile chum salmon cerebellum, a type of small cells was identified that represented the population of adult-type glial progenitors (aNSPCs) with a large, irregularly shaped nucleus and a narrow rim of cytoplasm. Among the aNSPCs in the ML of the cerebellum, both polarized cells with a large, irregularly shaped dark nucleus (type III) and cells with a light, irregularly shaped nucleus containing heterochromatin (type IV) were identified. Such cells were found in the parenchyma of the ML, approximately in the upper third, and were also identified by SEM on the dorsal and lateral surfaces of the cerebellar body (

Figure 7A–C). These cells were also involved in homeostatic neurogenesis, since they were prone to proliferative activity and the formation of surface clusters (

Figure 7D). In many fish species, structure-specific neurogenesis can be associated with the growth mode [

35].

Many teleosts exhibit the phenomenon of indefinite cerebellar growth, in which cells continue to be added throughout the body, including the CNS, as the fish grows [

63]. This has been demonstrated, e.g., in goldfish, which continue to grow for many years. In the brown ghost fish, considered as a model of mild aging, which also exhibits indefinite growth, up to 75% of all mitotically active cells are localized in the cerebellum [

59]. In

A. leptorhynchus, proliferative activity is observed in the DMZ along the CC midline, as well as in the VC and in the GrEm. Similarly, in zebrafish, the cerebellum grows proportionally more than other brain regions at the juvenile stage (30–90 days post-fertilization), and the CC containing GrCs exhibits significant growth throughout life [

41]. However, studies on zebrafish have shown that this species exhibits determinate growth [

64], consistent with the growth limitations observed in amniotes. Nevertheless, evidence from various fish species, including juvenile chum salmon, raises the question of why constitutive NSPCs proliferation is required in the cerebellum throughout life.

The results of ultrastructural analysis confirm previous IHC studies on juvenile masu salmon,

O. masou, with vimentin labeling [

15] and on juvenile chum salmon,

O. keta, with glutamine synthetase immunolabeling [

16]. According to the results of these studies, Vim+ and GS+ populations of superficial small cells are present in juvenile salmonids, and their number increases dramatically after exposure to acute traumatic injury [

15,

16]. We suggest that type III aNSPCs in intact juvenile chum salmon may be in a quiescent state and are not involved in homeostatic proliferation. In contrast, type IV aNSPCs may function as homeostatic precursors involved in constitutive growth of the cerebellum. Our data are consistent with the results of a study in zebrafish, in which resident neural stem cells in the postnatal cerebellum, known as “stem cell niches”, continue to generate newborn neurons [

65].

However, even in basic teleost fish models such as zebrafish, the extent of structural brain growth and neural stem cell activity is dramatically reduced in older individuals [

35,

65], suggesting that continuous brain growth is not unlimited. In zebrafish studies, more than 16 major neurogenic domains have been shown to exhibit constitutive neural stem cell proliferation [

66,

67]. However, as Zupanc reported, more than 100 neurogenic regions can be detected [

68]. In contrast, adult mammals have two main neural stem cell niches, which are limited to the subventricular zone of the forebrain and the subgranular zone of the hippocampus [

69].

Studies by Kaslin and Brand have shown that the proliferative activity of stem and progenitor populations of the zebrafish cerebellum decreases after the juvenile period (up to 3 months). However, in adulthood, progenitors originating from the superior rhombic lip continue to produce granular cells [

41]. In zebrafish, no new PCs or EDCs are formed after the juvenile stage. This reduced degree of postembryonic neurogenesis in the cerebellum coincides with the onset of a plateau in the growth of zebrafish compared to its close relative, the giant zebrafish [

64].

The results of studies on 1.5-year-old juvenile chum salmon showed that in the region of the neurogenic zones of

torus semicircularis, as well as

valvula cerebelli, a large number of aNSPCs in a state of constitutive proliferation are retained, with this number significantly increasing after injury [

36]. The detection of apoptotic bodies and heterogeneous groups of astrocytes and microgliocytes in the cerebellum (in the present study) and in the tegmentum of juvenile chum salmon [

36] indicates homeostatic apoptosis processes. These findings strongly suggest, that newly formed cells contribute to maintaining the brain homeostasis by replacing the population of cells that have died. Comparative studies on models of both determinate (zebrafish,

D. rerio) and indeterminate growth (chum salmon,

O. keta) are of certain interest to elucidate whether aNSPC populations of the cerebellum are capable of characteristic responses to environmental influences. In particular, further studies on juvenile chum salmon may address responses to sensory or motor stimuli that have been found in other stem cell niches of the adult zebrafish brain [

67,

70].

3.2.3. Non-Glial Progenitors in the DMZ and GrL and Neoteny

Understanding the cellular processes occuring at later stages of ontogenetic development is important for addressing age-related changes. The identification of a large population of non-glial aNSPCs in the DMZ and GrL of juvenile chum salmon, along with stromal cell clusters on the surface of the cerebellar ML, suggests the presence of a neurogenic and hematopoietic program in its brain, which is active primarily at embryonic stages in other vertebrate species [

68,

69]. The cerebellum is only one of the regions of the salmon brain where similar cell types were identified by SEM and TEM in the present study. Previously, using IHC methods, we identified similar neurogenic niches in various parts of the brain of adult trout

O. mykiss [

13,

62], masu salmon

O. masou [

14,

15], and chum salmon

O. keta [

16]. The presence of constitutive neurogenic clusters with proliferating cells in juvenile and adult Pacific salmon is a neotenic characteristic of the brain. It is known that in all vertebrate species, the embryonic period is characterized by a higher rate of cell proliferation compared to the adult phase [

71]. Furthermore, in some species such as salamanders and frogs, an extended larval period results in increased body size [

72,

73,

74]. This supports the hypothesis that the observed neotenic status in the juvenile chum salmon cerebellum may be a necessary adaptation for maintaining very high levels of metabolism and cell proliferation during homeostatic growth.

Our data confirm the results of studies on the killifish

Nothobranchius furzeri, which is one of the recognized shortest-lived vertebrates capable of breeding in captivity, with a lifespan of 3 to 8 months [

57,

75]. This species undergoes a rapid natural aging process as an adaptive response to the environment. Despite its short lifespan compared to other vertebrates,

N. furzeri displays many physiological features of aging found in other vertebrates [

75]. Recent studies in

N. furzeri have shown that non-glial progenitor cells are among the aNSPC populations that change most significantly between young and old animals [

57,

75]. It was found that embryonic gene expression in the adult brain is a common feature in

N. furzeri and that several cell populations in the adult

N. furzeri brain exhibit high levels of similarity to zebrafish embryonic populations. These data indicate that adult

N. furzeri maintain a neotenic gene expression state in the brain, which may support their characteristic high rates of proliferation and metabolism.

The results of ultrastructural studies of the juvenile chum salmon cerebellum show the persistence of neotenic structure at the level of organization of neurogenic and hematogenous cell clusters located in different regions of the cerebellum. Such cell types were identified as components of superficial neurogenic clusters in the ML, often containing erythrocytes, as well as in the GrL. A noteworthy feature of these structures is their potential similarity to embryonal clusters of zebrafish, as well as their involvement in neotenic growth of juvenile chum salmon, contributing to a significant increase in body size. Our findings are consistent with the results of studies on N. furzeri, which demonstrated neotenic features at the level of gene expression over a longer period and even persisted for some programs throughout life (unpublished data). This hypothesis was supported by direct comparison of individual cell clusters of N. furzeri with zebrafish embryo samples which revealed a high degree of correlation.

Ultrastructural analysis of non-glial progenitors in the juvenile chum salmon cerebellum provides insight into the evolutionary mechanisms that cells must acquire to adapt to the species' environment. Juvenile chum salmon is a good model for studying homeostatic growth and responses to traumatic injury however, extrapolation of these findings to other vertebrate species, such as mammals, should be approached with caution. Nevertheless, the neotenic status observed in juvenile chum salmon may be part of the species’ adaptation to its demanding ecological niche and may help identify promising cellular and molecular targets for regenerative or anti-aging therapies in the future.

3.3. Ganglion Layer

In terms of branching, the dendritic tree of PCs in fish is more complex than in amphibians and reptiles but is never as extensive as in mammals [

4]. In teleosts, the proximal, smooth part of the dendritic tree, which contains the receptive surface for ascending fibers, does not penetrate the molecular layer as it does in mammals. This has been best demonstrated for mormyrids, but is suggested to be common among many teleost species [

44].

There are several differences between the cerebellum of teleosts and the cerebellum of mammals. The mammalian cerebellum lacks EDCs and contains deep cerebellar nuclei that play a functionally homologous role as they receive axons from PCs and send efferent axons outside the cerebellum [

28]. In mammals, these intrinsic cerebellar nuclei are located ventrally, far from the PCs, whereas in teleosts, EDCs are located in close proximity to the PCs. Although both the mammalian cerebellar intrinsic nuclei and the teleost EDCs are projection neurons that send axons outside the cerebellum, it remains unclear whether they use the same molecular mechanisms for their function and development. They likely correspond to a modified version that arose through evolutionary divergence from the original or ancestral cerebellar nucleus.

The evolutionarily most ancient cartilaginous fishes have a well-defined cerebellar nucleus with subdivisions [

76,

77]. In the cerebellum of sturgeon, which belongs to the most ancient group of bony fishes, EDCs are grouped in three regions of the cerebellum and are less branched than in zebrafish [

78]. In addition, the EDCs of the basal actinopterygian fish

Polypterus senegalus are similar to those of teleosts, as well as to the deep nuclei of the mammalian cerebellum [

79]. Thus, the EDCs in the most ancient bony fishes are assumed to correspond to an intermediate stage before the emergence of true EDCs in bony fishes [

79].

As a result of our studies on juvenile chum salmon, we found that part of the PC population also contains a receptive surface for ascending fibers without penetrating the ML, which is consistent with data on

D. rerio [

28]. However, the PC population in juvenile chum salmon is quite heterogeneous: in particular, we found four types of morphologically distinct PCs, which is consistent with data from studies on zebrafish [

44]. PCs in juvenile chum salmon, as in all groups of gnathostomes, are considered the main neurons of the cerebellum and represent its main information processing center. IHC studies on juvenile masu salmon showed that the PCs are parvalbumin-ip, GABA-ip, and CBS-ip [

80]. Immunolocalization of GABA and the calcium-binding protein parvalbumin was detected in bodies and dendrites of the PCs, while the hydrogen sulfide synthesis enzyme was found to be localized in the fibers of the molecular layer [

80].

In zebrafish, the PCs express Zebrin-II. However, in this neuronal population, instead of a zebra-like compartmentalization as in mammals, all PCs are Zebrin-II (or aldolase-C) immunoreactive [

81], as in cartilaginous fish [

82,

83]. There are exceptions in some fish, in which some PCs have been reported to be Zebrin-II negative, but the PC population still does not exhibit layered segregation [

1]. Regardless of Zebrin-II expression, there is evidence that zebrafish PCs represent a heterogeneous population of cells. Recent studies of the mature zebrafish cerebellum have shown that PCs are involved in both locomotor and non-locomotor behaviors [

84,

85].

The results of the present study showed that the GL in juvenile chum salmon is not strictly organized, and part of the PCs appears ectopic in the GrL. The GL cells are surrounded by extra- and infraganglionic plexuses, within which apoptotic bodies were identified. Previously, apoptotic patterns were identified in the tegmentum of juvenile chum salmon [

36]. As known, apoptosis, which is a

programmed type of cell death, does not provoke an inflammatory reaction in the fish CNS [

86]. The outer membrane of the cell remains intact, and adjacent cells and tissues are not damaged [

87]. We believe that the death of undifferentiated cells formed during homeostatic neurogenesis is a consequence of natural differentiation and elimination of cell forms containing defects.

As shown by studies on

Apteronotus leptorhynchus [

88], if undifferentiated cells do not have time to establish connections with fibers and/or other types of cells, caspases are activated in them and cells undergo apoptosis. A study of aneuploid cells lacking genes that support vital activity in the brain of

A. leptorhynchus provided evidence that such cells are destroyed by apoptosis not only in the early stages of development, but also in the later stages of ontogenesis, when the consequences of inadequate gene expression appear [

89].

The main morphological signs of apoptosis recorded from the cells of the infraganglionic plexus of juvenile chum salmon were the cell shrinkage, cytoplasmic condensation, membrane swelling, nuclear fragmentation, and formation of apoptotic bodies (

Figure 9A). We suggest that in juvenile chum salmon, the latter are promptly and orderly eliminated by macrophages and resident microglia and are also found in the infraganglionic plexus region of the ganglion layer (

Figure 9F and

Figure 14A–C). Studies on the cerebellum of

A. leptorhynchus confirm that one of the main functions of microglia and macrophages may be removal of remnants of cells that have undergone apoptosis at the site of injury [

88]. It has been hypothesized that this

programmed type of cell death is a major factor in the rapid and, sometimes, complete regeneration of nervous tissue [

86]. Similar conclusions were made in a study of traumatic eye injury in adult trout,

O. mykiss [

90], and in a study of Wallerian degeneration of the optic tract in

Carassius auratus [

91]. In a study conducted at two days after spinal cord transection in zebrafish, along with myelin phagocytosis, a macrophage/microglia response was also observed caudally of the transection site using IHC and electron microscopy [

92].

In the area of the infraganglionic plexus, we found patterns of small, sprouting, weakly myelinated or unmyelinated fibers, indicating homeostatic axonogenesis in the juvenile chum salmon cerebellum.

3.3.1. Neuro-Glial Relationships in the Ganglion Layer of the Juvenile Chum Salmon Cerebellum

Microglia and astrocytes play important roles in the fish CNS, contributing to homeostasis, immune response, and maintenance of the blood–brain barrier and synaptic support [

61,

88]. Studies of various experimental models of glial communication have provided evidence that microglia and astrocytes influence and coordinate each other and their impact on the brain environment [

93,

94]. The detection of macroglia and microglia populations adjacent to the projection PCs in juvenile chum salmon using TEM was an important finding. The detection of astrocytes is very important for identifying neuro-glial relationships in the juvenile chum salmon cerebellum. These data are consistent with the results of studies of the chum salmon mesencephalic tegmentum where astrocytes and microgliocytes were also found [

36]. The protoplasmic astrocytes we detected in the cerebellum formed contacts with the PCs.

Our observations contrast with the data on zebrafish, in which astrocytic glia have not been detected [

44]. Along with astrocytes, we observed single ramified microgliocytes adjacent to astrocytes in the GL (

Figure 14A–C). The detection of a population of astroglia and microglia in the GL of the juvenile chum salmon cerebellum significantly expands current understanding of the cellular heterogeneity and functionality of homeostasis in the juvenile cerebellum of this species.

3.3.2. Astrocytes

Astrocytes are a subgroup of glial cells that help maintain and regulate neuronal function, including neurotransmitter cycling, metabolic support for neurons, and maintenance of the blood–brain barrier [

95]. In humans, the proportion of astrocytes in the brain ranges from 17 to 61%, depending on the region [

95]. According to our observations, in the of juvenile chum salmon cerebellum, the PCs to astrocytes ratio is 2 : 3.

Previous IHC studies on juvenile masu salmon,

O. masou, showed the presence of GFAP+ cells and fibers in the DMZ [

14]. Subsequent studies of vimentin and glutamine synthetase immunolocalization in the cerebellum of juvenile masu salmon

O. masou [

15], chum salmon

O. keta [

16], and trout

O. mykiss [

13] also confirmed the presence of an astrocytic population and radial glia, which contrasts with data on zebrafish [

44]. Thus, the juvenile chum salmon cerebellum has a population of astrocytes expressing glial markers, largely resembling the human brain model [

94,

96]. Thus the question as to whether the morphological heterogeneity of astrocytes in the juvenile chum salmon cerebellum is combined with the existence of astrocytic phenotypes known for the mammalian brain—the neurotoxic phenotype (A1) and the neuroprotective phenotype (A2) is becoming increasingly relevant.

According to the results of transcriptome analysis, intermediate or divergent transcriptome states can exist and even coexist in the same brain [

97]. In mammals, during neuroinflammation, astrocytes acquire a neurotoxic phenotype (A1) and additionally express GFAP [

98], which loses its neuroprotective abilities, leading to neuronal death. This A1 phenotype has been identified in Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease, motor neuron disease, and Parkinson’s disease [

99].

The finding of astrocytes in the juvenile chum salmon cerebellum is important in terms of neuroinflammatory processes. As a result of acute injury, the number of GFAP+, vimentin+, and GS+ cells in the juvenile salmon cerebellum increases [

14,

15,

16]. However, the increased production of glutamine synthetase during injury in juvenile salmon leads to a decrease in the excitotoxic effects of glutamate by neutralizing it to glutamine [

15,

16,

61]. The heterogeneous populations of protoplasmic astrocytes in the juvenile chum salmon cerebellum

, identified using TEM, are consistent with the assumption of probable coexistence of different phenotypes under homeostatic growth conditions in juveniles.

It is known that changes in the morphology, function, and number of astrocytes, referred to as “astrogliosis”, are observed as a result of traumatic brain injury and in human neurodegenerative diseases [

100]. However, many studies used GFAP to monitor astrocyte proliferation, suggesting that increased expression may be due to rather upregulation in individual cells than astrocyte proliferation [

101], as observed in a study using the proliferating cell marker PCNA [

102]. Furthermore, studies using astrocyte counting, via Nissl assays [

103] or constitutive astrocyte markers in combination with GFAP [

104], showed no difference in the number of cells between the brain affected by Alzheimer’s disease and the intact brain. In contrast, following cerebellar injury in juvenile masu and chum salmon, a significant increase in the number of PCNA, GFAP, Vim positive cells was observed [

14,

15]. Nevertheless, the different regenerative pathways involved in cerebellar repair in fish and mammals actualize new areas of interest in studying the biology and functional properties of cerebellar astrocytes in chum salmon.

The study of astrocyte properties in the juvenile salmon model is relevant for several reasons. First, unlike that in higher vertebrates, regeneration in the cerebellum of juvenile salmon is successful and is obviously associated with the existence of special phenotypes with increased expression of glutamine synthetase and other neuroprotective factors such as hydrogen sulfide and aromatase B [

16]. Second, the unique properties of astrocytes in the juvenile salmon brain can clarify which combinations of molecular markers are associated with successful reparation. Thus, in humans, there are two different subtypes of astrocytes, which are located either in layer I or in layer VI and project to other cortical layers [

105]. These interlaminar astrocytes have high expression of CD44, GFAP, and S100B (calcium-binding protein B S100), but low expression of glutamate processing markers, excitatory amino acid transporters EAAT1 and EAAT2, and glutamate synthetase [

106]. Similar transcriptional properties have also been found in the “fibrous astrocytes” of the white matter. Since the majority of astrocytic glial cells in the fish brain are represented by radial glia and often retain their radial identity throughout life [

107,

108], the protoplasmic-type astrocytes found in the juvenile chum salmon cerebellum are the final stage of astrogliogenesis. Such cells, as we suggest, are involved in maintaining the metabolism of projection interneurons of the ganglion and granular layers, and also directly influence neural connections, since they form tight contacts with the PCs (

Figure 5C,D). We also assume that the cells with dense, dark-stained cytoplasm and several processes found in the cerebellum, as those previously found in the tegmentum [

36] of juvenile chum salmon, are astrocytes that have separated from the ventricle and have a typical astrocytic phenotype. The differences consist in the structural features of the nuclei of these cells. While the tegmental astrocytes clearly visualized end-feet and a single nucleus of irregular shape [

36], in the astrocytes identified in the cerebellum, end-feet were rarely detected, and binucleation was also observed.

Another property of cerebellar astrocytes in juvenile chum salmon is their phagocytic ability. In the area of synaptic contacts, vesicles with secretory granules, possibly neurotransmitters, were found that undergoing astrocytic endocytosis by forming elongated processes resembling villi and capturing single vesicles (

Figure 13A,B). Such astrocytes were relatively large in size and had a large nucleus of irregular shape. Fish astrocytes contain the enzyme glutamine synthetase that converts toxic glutamate to neutral glutamine [

61,

109]. We assume that the capture of vesicles with glutamate by astrocytes promotes the metabolism of glutamate and its conversion to a neutral form to eliminate excitotoxicity. It is known that astrocytes are involved in synaptic transmission through the regulated release of glutamate, GABA, and D-serine [

95]. It was previously reported that GABAergic neurons are localized in the juvenile cerebellum of a closely related species, masu salmon [

80]. The release of gliotransmitters, accompanied by an increase in the Ca

2+ current in astrocytes, occurs in response to changes in the synaptic activity of neurons [

110] and can modulate the activity of large GABAergic interneurons in the juvenile chum salmon cerebellum.

In addition to directly influencing synaptic activity through the release of gliotransmitters, astrocytes have the potential to exert potent and long-lasting effects on synaptic function through the release of growth factors and cytokines [

111]. Astrocytes are also sources of neuroactive steroids (neurosteroids), including estradiol, progesterone, and aromatase, which can exert synaptic effects on GABA receptors [

16,

112,

113]. Studies on the juvenile chum salmon tegmentum have shown increased aromatase B expression in response to traumatic injury [

36]. The different types of astrocyte-neuron contacts identified in the cerebellum of juvenile chum salmon (

Figure 12B–D) allow the activation of astrocytes through neurotransmission, since astrocytes are known to express a variety of glutamate receptors [

113]. Upon activation of astrocytes, signaling pathways involving extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) are triggered [

114].

3.3.3. Microglia

Microglia is an important cell population involved in homeostatic maintenance of the fish brain. These cells exhibit variable proliferative activity and, under normal conditions, maintain a ramified morphological identity consistent with the resting state, similarly to the mammalian brain. Studies in zebrafish have shown that microglia is capable of transforming into an amoeboid, activated form under pathological conditions [

115]. When involved in CNS defense reactions, microglia in fish play an important role in synaptic degeneration [

116], regulation of neuronal components [

117,

118], clearance of apoptotic cells [

119], and in CNS angiogenesis and vascular maintenance [

120].

The results of ultrastructural studies on juvenile chum salmon showed the presence of ramified (resting) microglia (

Figure 14A–C). This type of cells was not found in the juvenile chum salmon tegmentum [

36]. Microgliocytes are resident macrophages of the brain and primary immune cells of the CNS, rapidly responding to injury, infection, and inflammation [

121]. Resident mammalian microgliocytes are believed to continuously interact with their environment throughout adult life, facilitating synaptic communication and maintaining cerebral homeostasis by constantly surveying the surrounding parenchyma with their finger-like processes [

122]. They have recently been identified as a multifunctional type of “housekeeping” cell [

123]. However, the exact function of microglia is still unclear.

Microglia are a heterogeneous population of CNS cells that play an active role in maintaining normal physiological conditions by scanning the cellular environment with branched processes and undergoing rapid morphological changes in response to mediators such as ATP [

92]. When activated, the ramified processes of microgliocytes retract and thicken, causing the cell to adopt an activated phenotype. Among fish, the best studied, including at the ultrastructural level, are the microglial cells of the optic nerve of

C. auratus [

124]. Activated microglial cells (macrophages) in the juvenile chum salmon cerebellum, identified as part of microvessels, are similar to those in the tegmentum [

36] and also resemble mammalian microglia, with a heterochromatic nucleus and a high content of extended RER [

121].

Various methods have been used to identify microglial cells in teleost fish [

92,

125,

126], among which lectin histochemistry has proven to be an effective tool for detecting microglia. Lectins from

Lycopersicon esculentum have an affinity for poly-N-acetyllactosamine sugar residues and have been shown to identify amoeboid and branched microglial cells in the neonatal and adult rat brain [

127], microglial cells in normal and injured fish retina and optic nerve [

128], and a microglial cluster in the pufferfish

Diodon holacanthus in supramedullary neurons [

129].

Studies on the juvenile chum salmon cerebellum showed that microglia is able to dynamically interact with synapses of the infraganglionic plexus and ganglion layer, changing their structure and function, being involved in the maintenance of cerebellar homeostasis. Ultrastructural data showed that microglia of juvenile chum salmon interact with astrocytes (

Figure 14B,C). We speculate that such macro- and microglia interactions may be involved in the production of soluble factors found in extracellular vesicles in the GL and GrL, which contribute to the integrity of the local neuronal environment. On the other hand, soluble factors contained in microglia appear to regulate neurogenic differentiation of aNSPCs, which is consistent with previous findings [

120,

130]. In particular, IL-6 and LIF molecules released by activated microgliocytes have been shown to promote glial differentiation of aNSPCs, highlighting the importance of cell–cell interactions between glial cells and NSPCs [

131].

Wnt signaling in adult zebrafish directly influences macrophage proliferation and cytokine release, modulating inflammation and regeneration, and regulating proliferation after injury in other structures such as the optic tectum [

132].

Studies of microglial behavior in fish are becoming increasingly common, in particular those focusing on the microglial response to injury through phagocytosis [

133,

134]. In ultrastructural studies on the juvenile chum salmon cerebellum, we found patterns of phagocytosis, as well as apoptotic bodies, indicating the presence of these processes during the homeostatic growth mode of juvenile

O. keta. The phagocytic behavior of immune cells and astrocytes is potentially important for establishing new connections in the brain during homeostatic growth, and also plays a significant role afte injury, since degenerating connections must be removed first before new connections can be formed [

135].

Of great interest are studies that have found that the brain can be repopulated by myeloid cells despite the presence of surviving microglia in the brain following depletion [

136], although the brain appears to favor only a single repopulation event. The ability of microglia to repopulate the brain at specific time points has potential for therapeutic applications. In mammals, chronic microglial activation has been shown to impede functional recovery following traumatic brain injury [

137]; therefore, the ablation of reactive microglia followed by repopulation with new microglial cells offers a potential strategy to reverse neuroinflammation and promote recovery [

138].

Data from zebrafish trauma studies show the development of a microglial inflammatory response characterized by morphological modification and accumulation of leukocytes at the injury site [

139,

140]. During the development of the inflammatory response in the zebrafish telencephalon, microglial cells migrate away from the injury site following the inactivation of sigma-1 receptors [

141]. The latter are intracellular proteins in neurons and glia known to play a role in neurodegeneration. Studies have examined the recruitment of both resident microglia and peripheral macrophages to brain injury and their distinct roles during the neuronal cell death response [

142,

143]. Further studies on juvenile chum salmon will help clarify the involvement of microglia in anti-inflammatory processes in traumatic brain injury.

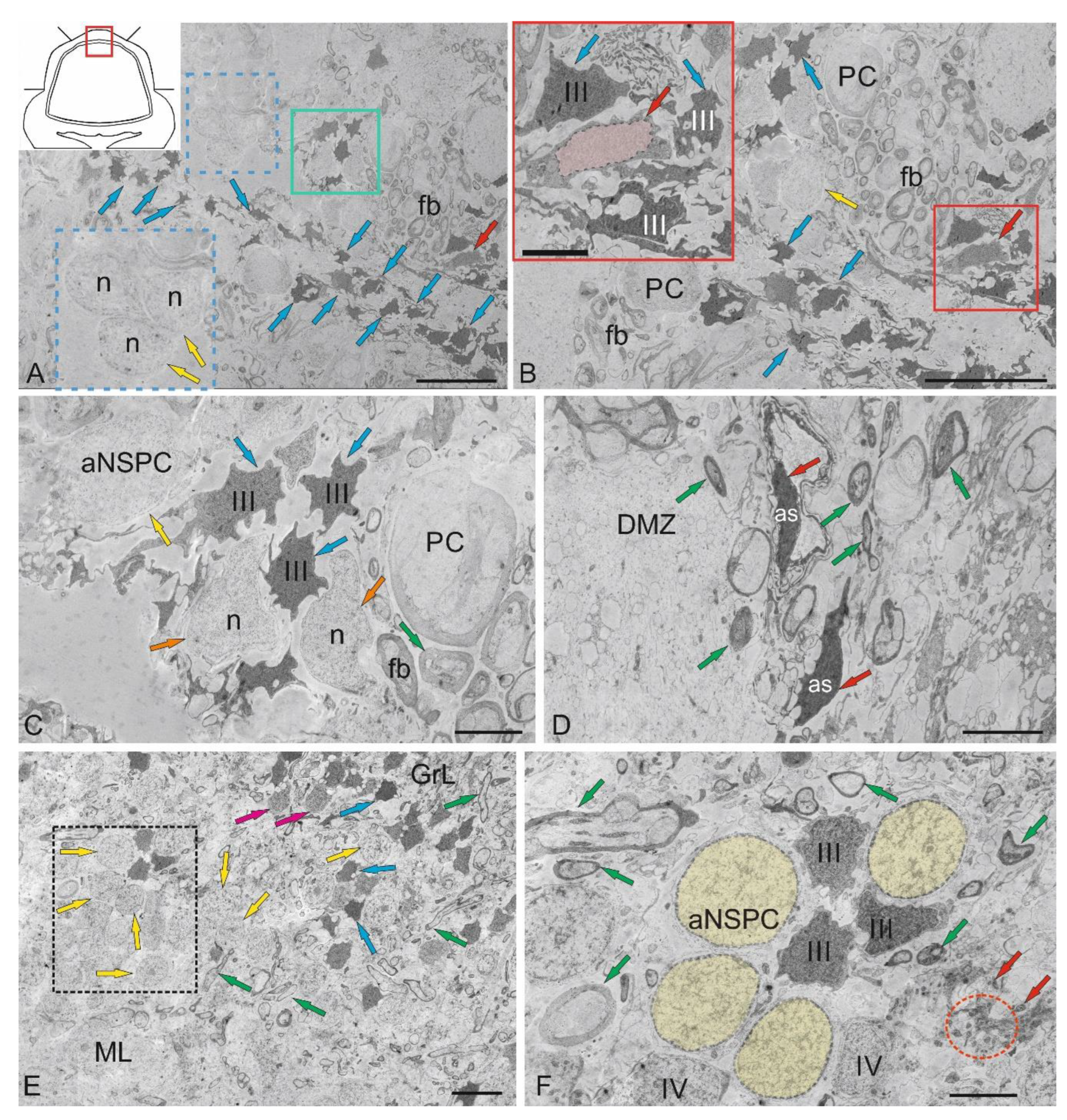

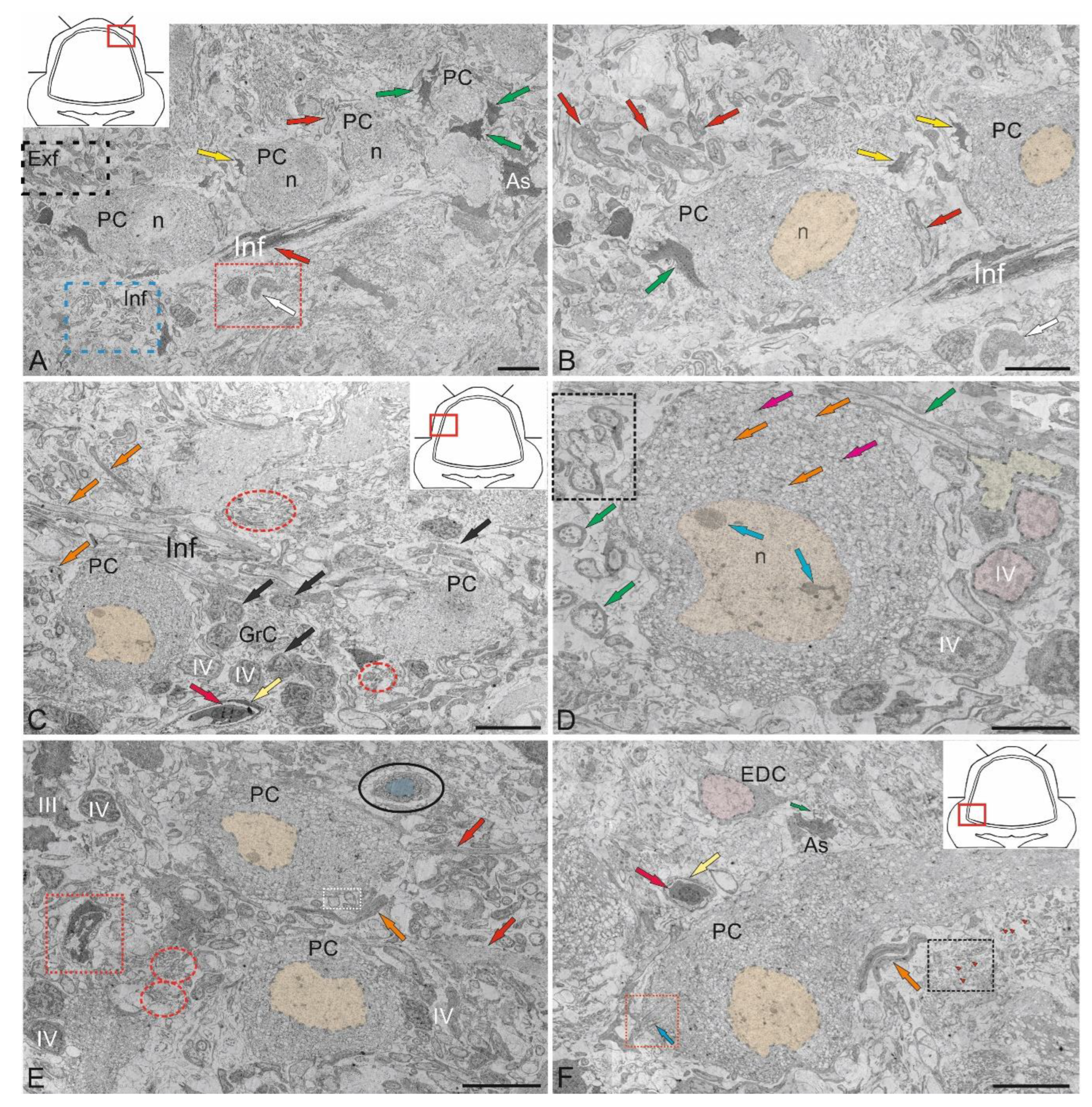

Figure 1.

Semi-thin sections (stained with methylene blue) demonstrating the structural organization of the cerebellar body in juvenile chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta. A – Dorsolateral region of the CC containing the molecular (ML), ganglion (GL) and granular (GrL) layers; Purkinje cells (PCs) are indicated by orange arrows; stellate cells (SCs), by blue arrow; vessels, by yellow arrows. B – Morphological structure of the dorsal matrix zone (DMZ): neuroepithelial cells are indicated by red arrows; small adult-type precursors, by yellow arrows; larger adult-type precursors, by green arrows; Purkinje cells (PCs), by orange arrows; astrocytes by white arrows; stellate cells in the ML, by blue arrows; patterns of sprouting fibers are outlined by red dotted square. C – Basolateral part of the CC region: Golgi cell (GC) is indicated by pink arrow; ectopic eurydendroid cell (EDC, magenta arrow) is shown in the thickened ML in the black dotted rectangle; PC is indicated by yellow asterisk in the red rectangle; ganglion cell cluster is outlined by black rectangle: piriform Purkinje cell (yellow arrow), bipolar eurydendroid cell (red arrow), and astrocyte (green arrow). D – Enlarged fragment in the black rectangle in C: Bergmann glia are indicated by blue arrow; granule cell clusters (GrCs) are outlined by red dotted ovals; other designations are as in Fig. C. E – Basolateral part of GrL: heterogeneous GrL cell clusters are outlined by red squares; adult-type progenitors (aNSPCs) are indicated by green arrows; GrCs, by red arrows; non-glial progenitors, by yellow arrows. F – Basal region of ML: patterns of sprouting unmyelinated fibers are outlined by red rectangle; microvessels are indicated by white arrows; Bergmann glia, by blue arrows; PC, by orange arrows; astrocytes, by green arrows; EDC, by crimson arrow. Scale bars: A, C, D – 50 µm; B, E, F – 20 µm.

Figure 1.

Semi-thin sections (stained with methylene blue) demonstrating the structural organization of the cerebellar body in juvenile chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta. A – Dorsolateral region of the CC containing the molecular (ML), ganglion (GL) and granular (GrL) layers; Purkinje cells (PCs) are indicated by orange arrows; stellate cells (SCs), by blue arrow; vessels, by yellow arrows. B – Morphological structure of the dorsal matrix zone (DMZ): neuroepithelial cells are indicated by red arrows; small adult-type precursors, by yellow arrows; larger adult-type precursors, by green arrows; Purkinje cells (PCs), by orange arrows; astrocytes by white arrows; stellate cells in the ML, by blue arrows; patterns of sprouting fibers are outlined by red dotted square. C – Basolateral part of the CC region: Golgi cell (GC) is indicated by pink arrow; ectopic eurydendroid cell (EDC, magenta arrow) is shown in the thickened ML in the black dotted rectangle; PC is indicated by yellow asterisk in the red rectangle; ganglion cell cluster is outlined by black rectangle: piriform Purkinje cell (yellow arrow), bipolar eurydendroid cell (red arrow), and astrocyte (green arrow). D – Enlarged fragment in the black rectangle in C: Bergmann glia are indicated by blue arrow; granule cell clusters (GrCs) are outlined by red dotted ovals; other designations are as in Fig. C. E – Basolateral part of GrL: heterogeneous GrL cell clusters are outlined by red squares; adult-type progenitors (aNSPCs) are indicated by green arrows; GrCs, by red arrows; non-glial progenitors, by yellow arrows. F – Basal region of ML: patterns of sprouting unmyelinated fibers are outlined by red rectangle; microvessels are indicated by white arrows; Bergmann glia, by blue arrows; PC, by orange arrows; astrocytes, by green arrows; EDC, by crimson arrow. Scale bars: A, C, D – 50 µm; B, E, F – 20 µm.

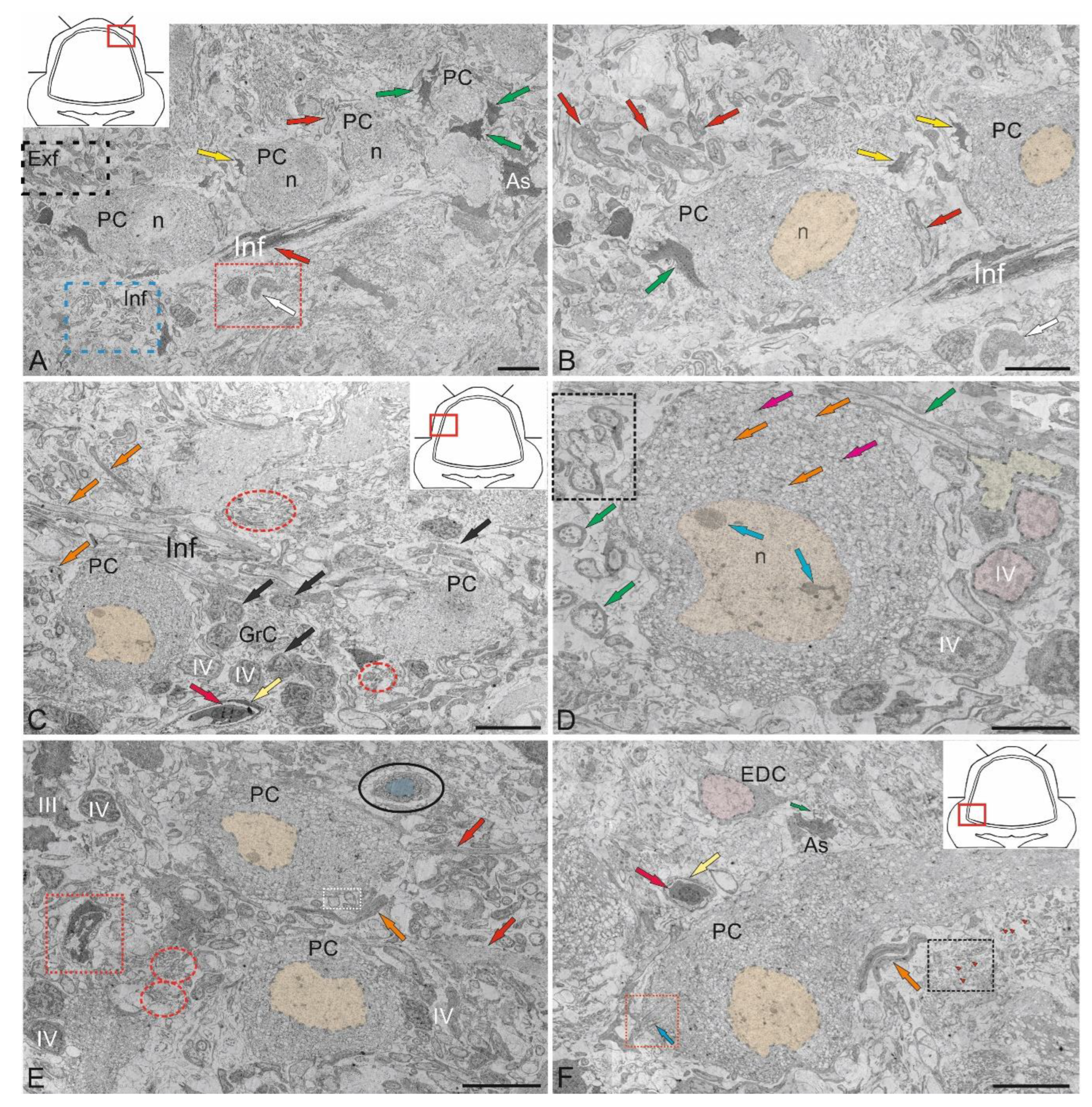

Figure 2.

Semi-thin sections (stained with methylene blue) demonstrating the structural organization of the valvula cerebelli in juvenile chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta. A – Rostro-lateral part of the VC: PCs are indicated by orange arrows; EDCs, by light green arrows; neurons with bipolar morphology, by black arrows. B – Medial part of the VC: clusters of heterogeneous cell types are outlined by red dotted ovals; neurons of the dorso-medial VC, by yellow arrows; microvessels, by white arrows; other designations as in A. C – Dorso-medial part of the VC: PCs are indicated by orange arrows; large protoplasmic astrocytes, by green arrows; Bergmann glia, by blue arrow; astrocytes, by crimson arrows; cells of the supraganglionic region, by pink arrow. Scale bar: 50 µm.

Figure 2.

Semi-thin sections (stained with methylene blue) demonstrating the structural organization of the valvula cerebelli in juvenile chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta. A – Rostro-lateral part of the VC: PCs are indicated by orange arrows; EDCs, by light green arrows; neurons with bipolar morphology, by black arrows. B – Medial part of the VC: clusters of heterogeneous cell types are outlined by red dotted ovals; neurons of the dorso-medial VC, by yellow arrows; microvessels, by white arrows; other designations as in A. C – Dorso-medial part of the VC: PCs are indicated by orange arrows; large protoplasmic astrocytes, by green arrows; Bergmann glia, by blue arrow; astrocytes, by crimson arrows; cells of the supraganglionic region, by pink arrow. Scale bar: 50 µm.

Figure 3.

Semi-thin sections (stained with methylene blue) showing the structural organization of granular eminences (GrEm) in the cerebellum of juvenile chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta. A – Morphological structure of GrEm containing molecular (ML) and granular (GrL) layers: fibers are indicated by green arrows; astrocytes, by crimson arrows; neurons, by pink arrows. B – A at higher magnification: clusters of aNSPCs in GrL are outlined by red dotted ovals; neuron is indicated by pink arrow. C – Ventrolateral zone of GrEm: fibers of lateral cerebellar peduncles are indicated by green arrows; GC, by pink arrow. D – At the border of the ML and GrL: clusters with aNSPCs are outlined by red dotted rectangles; non glial aNSPCs are indicated by yellow arrows. E – Ventrolateral part of the VC: parenchymatous clusters of aNSPCs are outlined by red dotted rectangles; superficial clusters of aNSPCs, by red dotted oval; single aNSPCs are indicated by yellow arrows. F – Ventromedial part of the VC: clusters of unmyelinated fibers are indicated by red arrows. Scale bars: A, C – 50 µm; B, D–F – 20 µm.

Figure 3.

Semi-thin sections (stained with methylene blue) showing the structural organization of granular eminences (GrEm) in the cerebellum of juvenile chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta. A – Morphological structure of GrEm containing molecular (ML) and granular (GrL) layers: fibers are indicated by green arrows; astrocytes, by crimson arrows; neurons, by pink arrows. B – A at higher magnification: clusters of aNSPCs in GrL are outlined by red dotted ovals; neuron is indicated by pink arrow. C – Ventrolateral zone of GrEm: fibers of lateral cerebellar peduncles are indicated by green arrows; GC, by pink arrow. D – At the border of the ML and GrL: clusters with aNSPCs are outlined by red dotted rectangles; non glial aNSPCs are indicated by yellow arrows. E – Ventrolateral part of the VC: parenchymatous clusters of aNSPCs are outlined by red dotted rectangles; superficial clusters of aNSPCs, by red dotted oval; single aNSPCs are indicated by yellow arrows. F – Ventromedial part of the VC: clusters of unmyelinated fibers are indicated by red arrows. Scale bars: A, C – 50 µm; B, D–F – 20 µm.

Figure 4.

Ultrastructural organization of cells of the molecular layer (ML) of the cerebellum in juvenile chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta. A – A stellate cell (SC) from the upper third of the ML: the nucleus is highlighted in blue; mitochondria are indicated by pink arrows; vacuoles, by blue arrow; secretory granules, by yellow arrows. B – A cross section at the level of the Purkinje cell dendrite (DPC) forming synaptic contacts: the presynaptic region is indicated by a red arrowhead; the postsynaptic region, by a blue arrowhead; nodular synaptic terminals, by pink arrows; mitochondria, by crimson arrows; parallel fibers (pfs), by white arrows. C – An enlarged fragment in B demonstrating the area of the primary synapse in the SCs (designations as in B). D – Fragment of the PC, receiving numerous synaptic terminals (shown in pink) of the electrotonic type (es) converge: primary dendrites of the PC are indicated by green arrows. E – Oligodendrogliocyte involved in the process of formation of myelin fibers (frs): invaginated area of the oligodendrocyte is indicated by black dotted line; large mitochondrion, by crimson arrow; oligodendrocyte process, by red arrow; rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER), by orange arrow; secretory granules with myelin are outlined by red dotted ovals; mature form of vesicles, by blue arrows. F – Structure of chemical synapse on the body of the PC (in the red dotted square): presynaptic area is indicated by red arrowhead; postsynaptic area, by blue arrowhead; synaptic endings are highlighted in pink; mitochondria, by crimson arrows; vacuoles, by orange arrows. TEM. Scale bars: A – 1 µm; B, D–F – 400 nm; C – 200 nm.

Figure 4.

Ultrastructural organization of cells of the molecular layer (ML) of the cerebellum in juvenile chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta. A – A stellate cell (SC) from the upper third of the ML: the nucleus is highlighted in blue; mitochondria are indicated by pink arrows; vacuoles, by blue arrow; secretory granules, by yellow arrows. B – A cross section at the level of the Purkinje cell dendrite (DPC) forming synaptic contacts: the presynaptic region is indicated by a red arrowhead; the postsynaptic region, by a blue arrowhead; nodular synaptic terminals, by pink arrows; mitochondria, by crimson arrows; parallel fibers (pfs), by white arrows. C – An enlarged fragment in B demonstrating the area of the primary synapse in the SCs (designations as in B). D – Fragment of the PC, receiving numerous synaptic terminals (shown in pink) of the electrotonic type (es) converge: primary dendrites of the PC are indicated by green arrows. E – Oligodendrogliocyte involved in the process of formation of myelin fibers (frs): invaginated area of the oligodendrocyte is indicated by black dotted line; large mitochondrion, by crimson arrow; oligodendrocyte process, by red arrow; rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER), by orange arrow; secretory granules with myelin are outlined by red dotted ovals; mature form of vesicles, by blue arrows. F – Structure of chemical synapse on the body of the PC (in the red dotted square): presynaptic area is indicated by red arrowhead; postsynaptic area, by blue arrowhead; synaptic endings are highlighted in pink; mitochondria, by crimson arrows; vacuoles, by orange arrows. TEM. Scale bars: A – 1 µm; B, D–F – 400 nm; C – 200 nm.

Figure 5.

Ultrastructural organization of synaptic terminals in the molecular layer of the CC in juvenile chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta. A – Primary axo-somatic synapses (430–630 μm) in the molecular layer (ML) converging on the PC, large mitochondria in the cytoplasm of the dendritic bouquet are indicated by crimson arrows; secondary dendrites of the PC are indicated by green arrows; synaptic terminals of the electrotonic type (es) are highlighted in pink; the presynaptic component in the synaptic terminal of the chemical type (1.2 μm long), by a red arrowhead; the postsynaptic component, by blue arrowheads. B – Enlarged image of a double synaptic terminal of the chemical type, converging on the primary dendrite of the PC; designations as in A. C – Synaptic structures of T-shaped morphology (in the blue dotted rectangle), connected by fibrous strands (green arrows) with club-shaped endings (in the red rectangle): synaptic vesicles are indicated by yellow arrows; other designations as in A. D – Enlarged fragment of a single elongated synaptic terminal (1.3 μm long); designations as in A. E – On the right, patterns of synaptic terminals (shown by pink), converging on climbing fibers (cfs); on the left, a fragment of the dendritic bouquet of the PC; designations as in A. F – Axo-somatic synaptic terminals of the electrotonic type, converging on the PC and adjacent areas of the ML; designations as in A. TEM. Scale bars: A – 1 μm; B–E – 400 nm; F – 200 nm.

Figure 5.

Ultrastructural organization of synaptic terminals in the molecular layer of the CC in juvenile chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta. A – Primary axo-somatic synapses (430–630 μm) in the molecular layer (ML) converging on the PC, large mitochondria in the cytoplasm of the dendritic bouquet are indicated by crimson arrows; secondary dendrites of the PC are indicated by green arrows; synaptic terminals of the electrotonic type (es) are highlighted in pink; the presynaptic component in the synaptic terminal of the chemical type (1.2 μm long), by a red arrowhead; the postsynaptic component, by blue arrowheads. B – Enlarged image of a double synaptic terminal of the chemical type, converging on the primary dendrite of the PC; designations as in A. C – Synaptic structures of T-shaped morphology (in the blue dotted rectangle), connected by fibrous strands (green arrows) with club-shaped endings (in the red rectangle): synaptic vesicles are indicated by yellow arrows; other designations as in A. D – Enlarged fragment of a single elongated synaptic terminal (1.3 μm long); designations as in A. E – On the right, patterns of synaptic terminals (shown by pink), converging on climbing fibers (cfs); on the left, a fragment of the dendritic bouquet of the PC; designations as in A. F – Axo-somatic synaptic terminals of the electrotonic type, converging on the PC and adjacent areas of the ML; designations as in A. TEM. Scale bars: A – 1 μm; B–E – 400 nm; F – 200 nm.

Figure 6.

Stereoscopic organization of cf in the cerebellum of juvenile chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta. A – The structure of cf afferents with varicose dilatations (red arrows) and terminal thickenings. B – A magnified fragment showing the terminal thickenings (white arrows) and the cf branching node (in the blue dotted rectangle). C – The surface over which cf extends in the cerebellum has a complex and heterogeneous relief, including numerous synaptic structures (yellow arrows). D – A magnified fragment showing synaptic areas that look like a multidimensional network with numerous spherical thickenings (in the red rectangle). SEM. Scale bars: A, C, D – 2 µm; B – 1 µm.

Figure 6.

Stereoscopic organization of cf in the cerebellum of juvenile chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta. A – The structure of cf afferents with varicose dilatations (red arrows) and terminal thickenings. B – A magnified fragment showing the terminal thickenings (white arrows) and the cf branching node (in the blue dotted rectangle). C – The surface over which cf extends in the cerebellum has a complex and heterogeneous relief, including numerous synaptic structures (yellow arrows). D – A magnified fragment showing synaptic areas that look like a multidimensional network with numerous spherical thickenings (in the red rectangle). SEM. Scale bars: A, C, D – 2 µm; B – 1 µm.

Figure 7.

Stereoscopic organization of adult non-glial neural stem cells (aNSPCs) in the cerebellum of juvenile chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta. A – aNSPCs are anchored by microfibrils (red arrows) to the surface of the ML, erythrocyte (Er). B – The surface microcytosculpture of aNSPCs is heterogeneous and has a bumpy relief. C – aNSPCs surrounded by the extracellular matrix of the pial membrane, aNSPCs (crimson arrow) were often adjacent to biconcave erythrocytes (Er) with a smooth surface. D – aNSPCs often formed paired clusters (in the red rectangle). E – Superficial stromal cluster of aNSPCs (in the red oval). F – Diffuse patterns of single aNSPC distribution (white arrow). SEM. Scale bars: A, B, D – 1 µm; C – 3 µm; E, F – 2 µm.

Figure 7.

Stereoscopic organization of adult non-glial neural stem cells (aNSPCs) in the cerebellum of juvenile chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta. A – aNSPCs are anchored by microfibrils (red arrows) to the surface of the ML, erythrocyte (Er). B – The surface microcytosculpture of aNSPCs is heterogeneous and has a bumpy relief. C – aNSPCs surrounded by the extracellular matrix of the pial membrane, aNSPCs (crimson arrow) were often adjacent to biconcave erythrocytes (Er) with a smooth surface. D – aNSPCs often formed paired clusters (in the red rectangle). E – Superficial stromal cluster of aNSPCs (in the red oval). F – Diffuse patterns of single aNSPC distribution (white arrow). SEM. Scale bars: A, B, D – 1 µm; C – 3 µm; E, F – 2 µm.

Figure 8.

Ultrastructural organization of the dorsal matrix zone (DMZ) of the cerebellum in juvenile chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta. A – General view of the dorsal matrix zone (DMZ, shown in the red square in the pictogram), including (in the dorsomedial region) an accumulation of non-glial type aNSPCs (blue dotted inset), more ventrally, a cluster of aNSPCs (in the green square): individual aNSPCs are indicated by blue arrows; patterns of sprouting myelinated fibers (fbs) and a neuroepithelial cell (NEC), by red arrow. B – Enlarged fragment showing details of the NEC ultrastructure (red inset) surrounded by type III aNSPCs (blue arrows) and Purkinje cells (PCs). C – Enlarged fragment showing ultrastructural details of the heterogeneous cluster in the green square in A: type III aNSPCs are indicated by blue arrows; non-glial aNSPCs, by yellow arrow; non-glial type intermediate progenitors, by orange arrows; myelinated fibers (fbs), by green arrows; Purkinje cells (PCs). D – Organization patterns of perivascular astroglia (as) are indicated by red arrows; fibers, by green arrows. E – Non-glial aNSPCs (yellow arrows) form clusters in the ML (in the black dotted rectangle) and at the border of the GrL GrEm: type III aNSPCs are indicated by blue arrows; type IV aNSPCs, by crimson arrows; cf, by green arrows. F – Enlarged fragment in the black dotted rectangle in E: non-glial aNSPCs are highlighted in yellow; aNSPCs type III (III), aNSPCs type IV (IV), secretory granules (indicated by red arrows); red dotted oval outlines the accumulation of secretory granules. TEM. Scale bars: A, B – 20 µm; inset, E – 10 µm; C, D, F – 5 µm.

Figure 8.

Ultrastructural organization of the dorsal matrix zone (DMZ) of the cerebellum in juvenile chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta. A – General view of the dorsal matrix zone (DMZ, shown in the red square in the pictogram), including (in the dorsomedial region) an accumulation of non-glial type aNSPCs (blue dotted inset), more ventrally, a cluster of aNSPCs (in the green square): individual aNSPCs are indicated by blue arrows; patterns of sprouting myelinated fibers (fbs) and a neuroepithelial cell (NEC), by red arrow. B – Enlarged fragment showing details of the NEC ultrastructure (red inset) surrounded by type III aNSPCs (blue arrows) and Purkinje cells (PCs). C – Enlarged fragment showing ultrastructural details of the heterogeneous cluster in the green square in A: type III aNSPCs are indicated by blue arrows; non-glial aNSPCs, by yellow arrow; non-glial type intermediate progenitors, by orange arrows; myelinated fibers (fbs), by green arrows; Purkinje cells (PCs). D – Organization patterns of perivascular astroglia (as) are indicated by red arrows; fibers, by green arrows. E – Non-glial aNSPCs (yellow arrows) form clusters in the ML (in the black dotted rectangle) and at the border of the GrL GrEm: type III aNSPCs are indicated by blue arrows; type IV aNSPCs, by crimson arrows; cf, by green arrows. F – Enlarged fragment in the black dotted rectangle in E: non-glial aNSPCs are highlighted in yellow; aNSPCs type III (III), aNSPCs type IV (IV), secretory granules (indicated by red arrows); red dotted oval outlines the accumulation of secretory granules. TEM. Scale bars: A, B – 20 µm; inset, E – 10 µm; C, D, F – 5 µm.

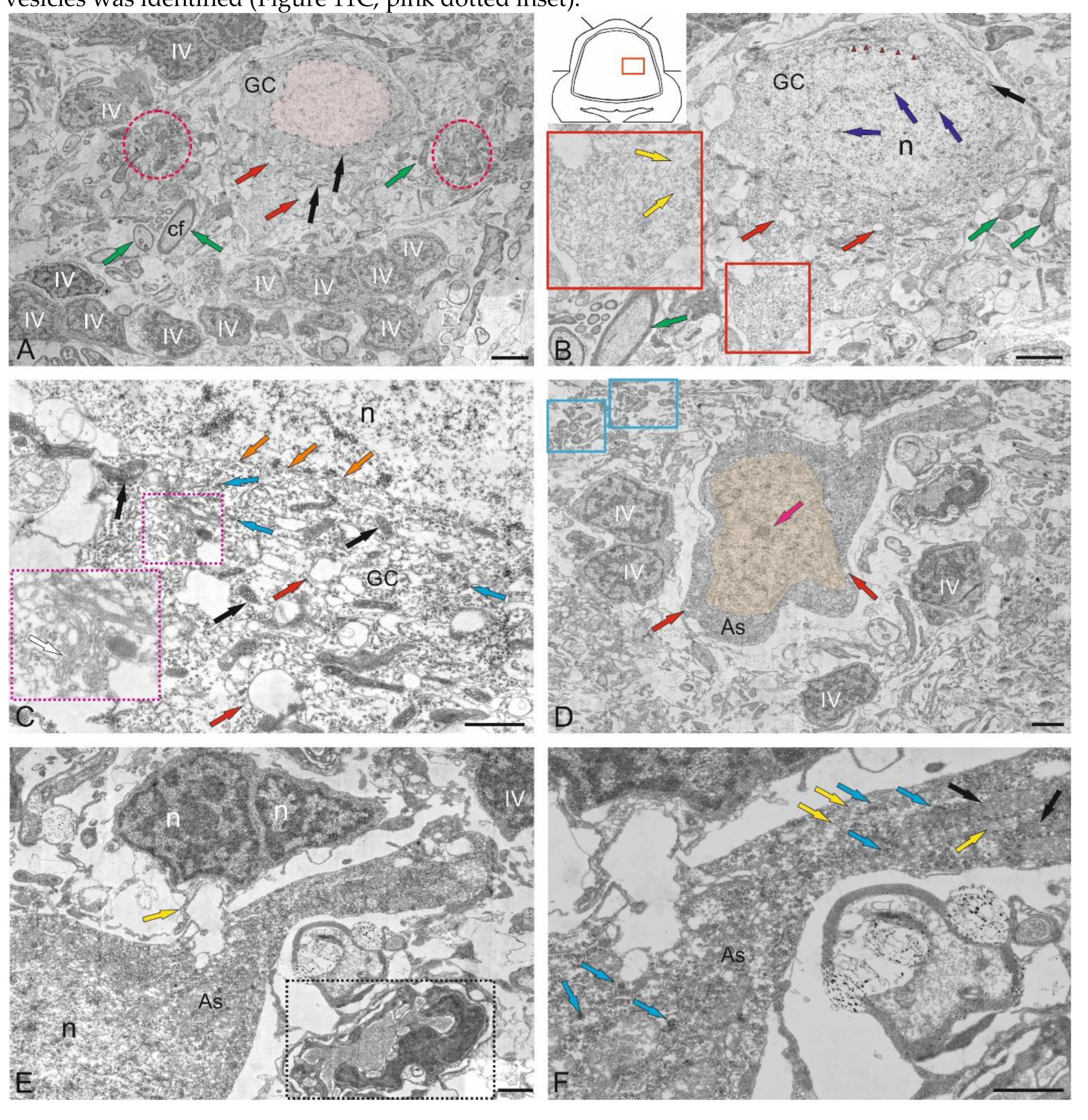

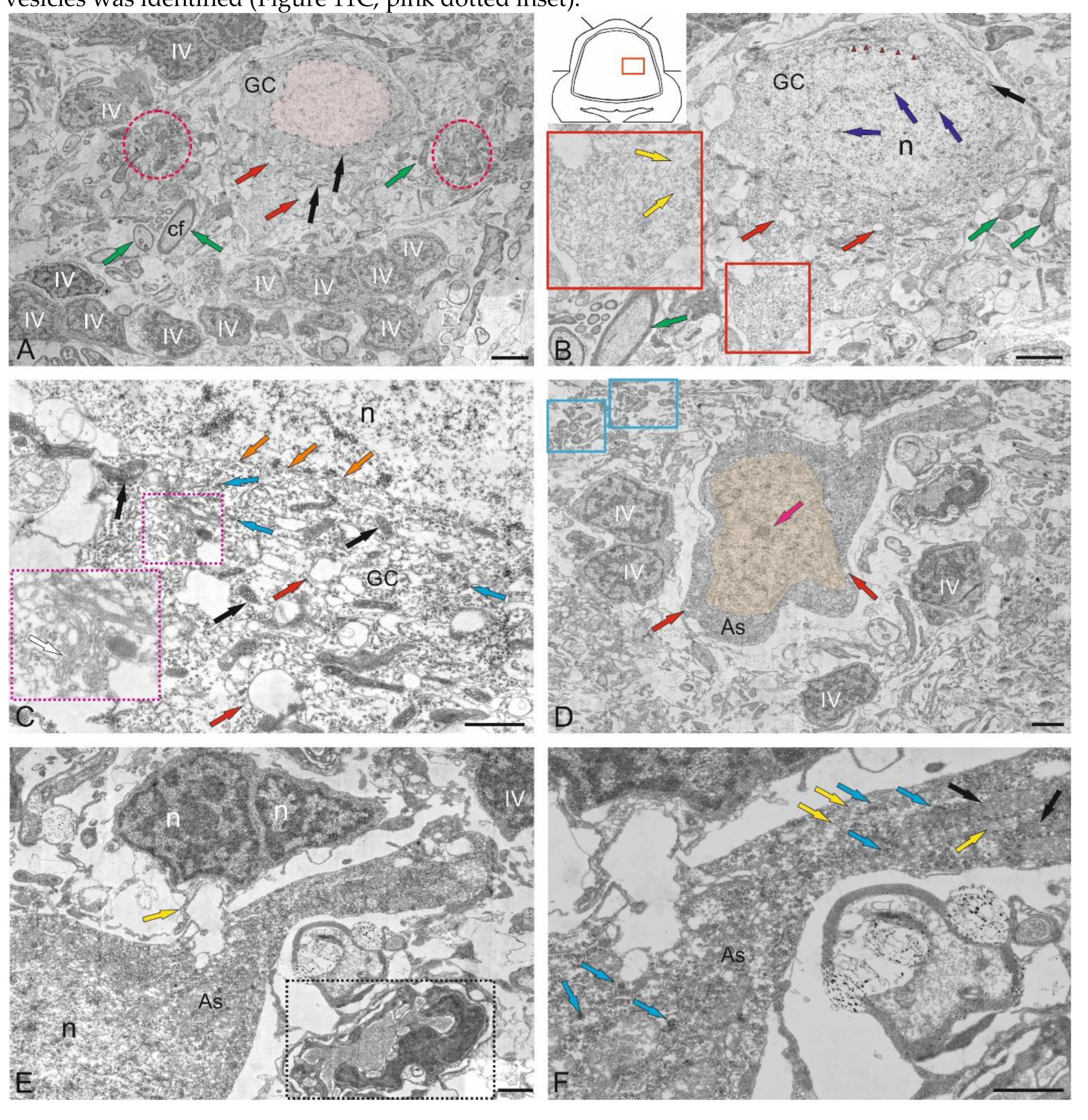

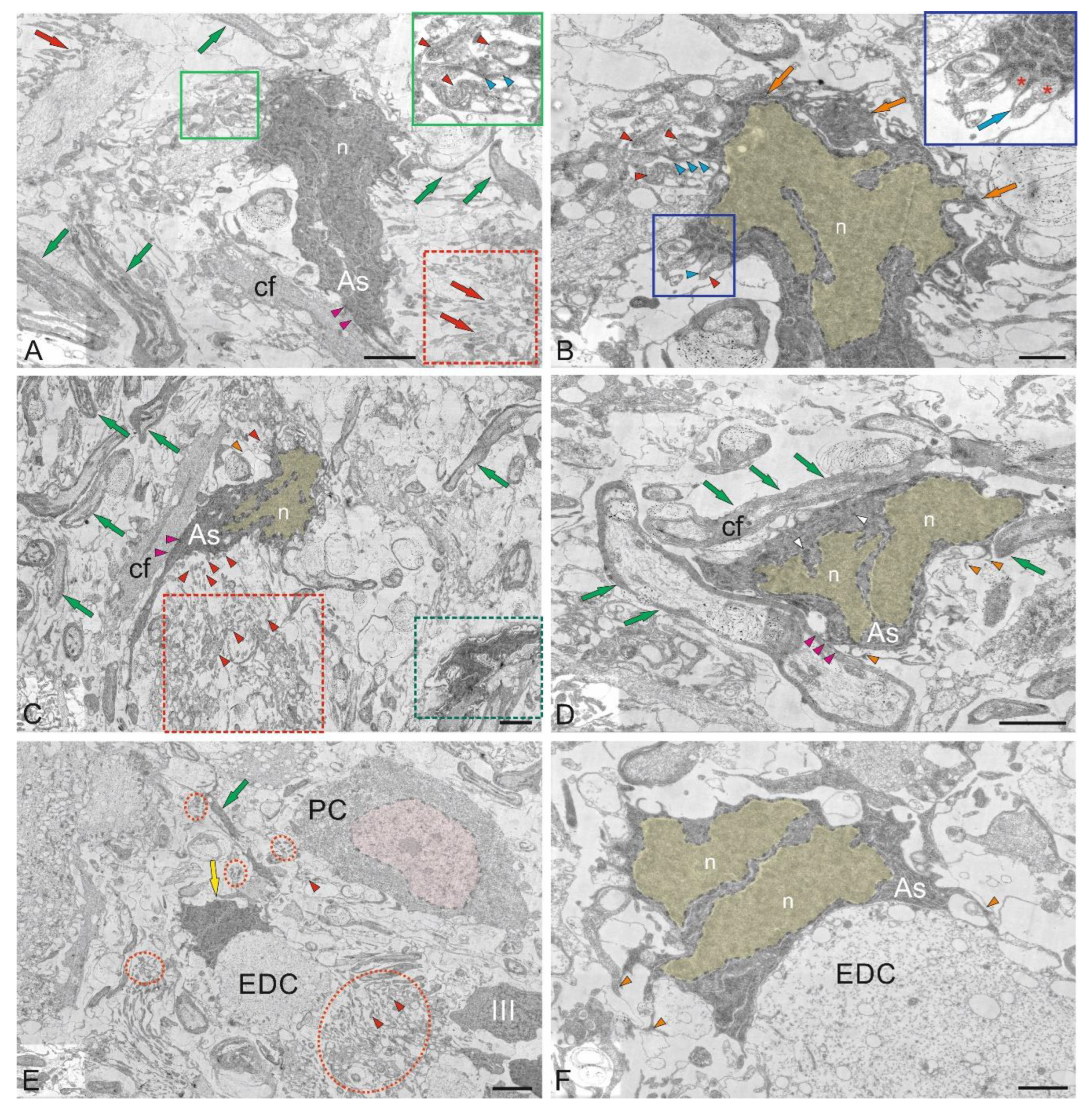

Figure 9.

Ultrastructural organization of the ganglionic layer of the cerebellum in juvenile chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta. A – General view of the ganglionic layer (GL) formed by Purkinje cells (PCs); PCs nuclei (n); fibers above the GL form the extraganglionic plexus (Exf, in the black dotted rectangle); fibers below the GL form the infraganglionic plexus (Inf, in the blue dotted rectangle); fragments of apoptotic bodies (white arrow) are outlined by the red dotted rectangle; astrocytes (As) of the protoplasmic type are indicated by green arrows; microgliocyte, by yellow arrow; infraganglionic fibers, by red arrows. B – Enlarged fragment of the GL; PCs nuclei (n) are highlighted in yellow; other designations are as in A. C – GL neurons from the lateral area are ectopic in the GrL and are surrounded by type IV granular cells (black arrows); Inf fibers are indicated by orange arrows; areas with secretory granules and fibers are outlined by red dotted ovals; a vessel (yellow arrow) with an agranular macrophage is indicated by a red arrow. D – An enlarged fragment of GL in the lateral zone; nucleoli in the nucleus (n) of the PC are indicated by blue arrows; vacuoles, by orange arrows; mitochondria, by crimson arrows; fibers, by green arrows; aNSPCs type IV nuclei are highlighted in pink; a mitotically dividing nucleus IV, in yellow; a fragment containing fibers with mitochondria is outlined with a black dotted rectangle. E - Contacts of the PC with electrotonic-type fibers on the PC bodies (outlined by a white dotted rectangle), endings of cfs (orange arrows), a granulocyte (in a black oval) with large vacuoles in dense cytoplasm and a homogeneous nucleus (highlighted in blue); fragments of unbranched PC dendrites are indicated by red arrows; patterns of sprouting fibers, by red dotted ovals; patterns of apoptosis are outlined by a red dotted rectangle; type III aNSPCs – III; type IV aNSPCs – IV. F - GL neurons from the ventrolateral region: the nucleus of the ML is highlighted in yellow; the axonal hillock containing actin filaments is outlined by red dotted square (blue arrow); cf endings on the PC body are indicated by orange arrows; secretory granules are outlined by black dotted rectangle (red arrowheads); a eurydendroid cell (EDC) with an irregularly shaped nucleus (highlighted in pink); the vessel with an agranular macrophage is indicated by the yellow arrow (red arrow); an astrocyte (As) phagocytic vesicle with glutamate, by green arrow. TEM. Scale bars: A–C, E, F – 10 µm; D – 5 µm.

Figure 9.

Ultrastructural organization of the ganglionic layer of the cerebellum in juvenile chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta. A – General view of the ganglionic layer (GL) formed by Purkinje cells (PCs); PCs nuclei (n); fibers above the GL form the extraganglionic plexus (Exf, in the black dotted rectangle); fibers below the GL form the infraganglionic plexus (Inf, in the blue dotted rectangle); fragments of apoptotic bodies (white arrow) are outlined by the red dotted rectangle; astrocytes (As) of the protoplasmic type are indicated by green arrows; microgliocyte, by yellow arrow; infraganglionic fibers, by red arrows. B – Enlarged fragment of the GL; PCs nuclei (n) are highlighted in yellow; other designations are as in A. C – GL neurons from the lateral area are ectopic in the GrL and are surrounded by type IV granular cells (black arrows); Inf fibers are indicated by orange arrows; areas with secretory granules and fibers are outlined by red dotted ovals; a vessel (yellow arrow) with an agranular macrophage is indicated by a red arrow. D – An enlarged fragment of GL in the lateral zone; nucleoli in the nucleus (n) of the PC are indicated by blue arrows; vacuoles, by orange arrows; mitochondria, by crimson arrows; fibers, by green arrows; aNSPCs type IV nuclei are highlighted in pink; a mitotically dividing nucleus IV, in yellow; a fragment containing fibers with mitochondria is outlined with a black dotted rectangle. E - Contacts of the PC with electrotonic-type fibers on the PC bodies (outlined by a white dotted rectangle), endings of cfs (orange arrows), a granulocyte (in a black oval) with large vacuoles in dense cytoplasm and a homogeneous nucleus (highlighted in blue); fragments of unbranched PC dendrites are indicated by red arrows; patterns of sprouting fibers, by red dotted ovals; patterns of apoptosis are outlined by a red dotted rectangle; type III aNSPCs – III; type IV aNSPCs – IV. F - GL neurons from the ventrolateral region: the nucleus of the ML is highlighted in yellow; the axonal hillock containing actin filaments is outlined by red dotted square (blue arrow); cf endings on the PC body are indicated by orange arrows; secretory granules are outlined by black dotted rectangle (red arrowheads); a eurydendroid cell (EDC) with an irregularly shaped nucleus (highlighted in pink); the vessel with an agranular macrophage is indicated by the yellow arrow (red arrow); an astrocyte (As) phagocytic vesicle with glutamate, by green arrow. TEM. Scale bars: A–C, E, F – 10 µm; D – 5 µm.

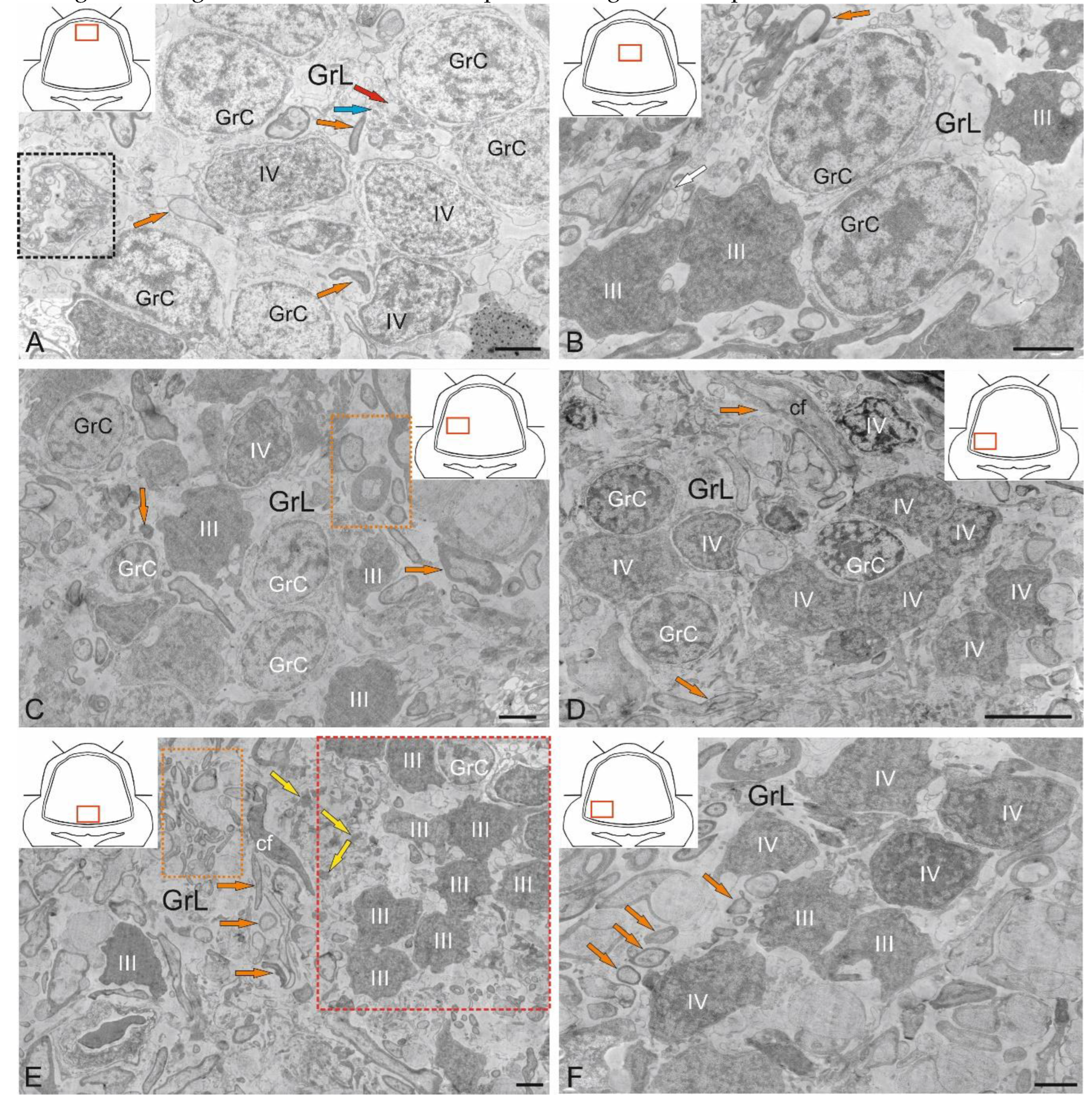

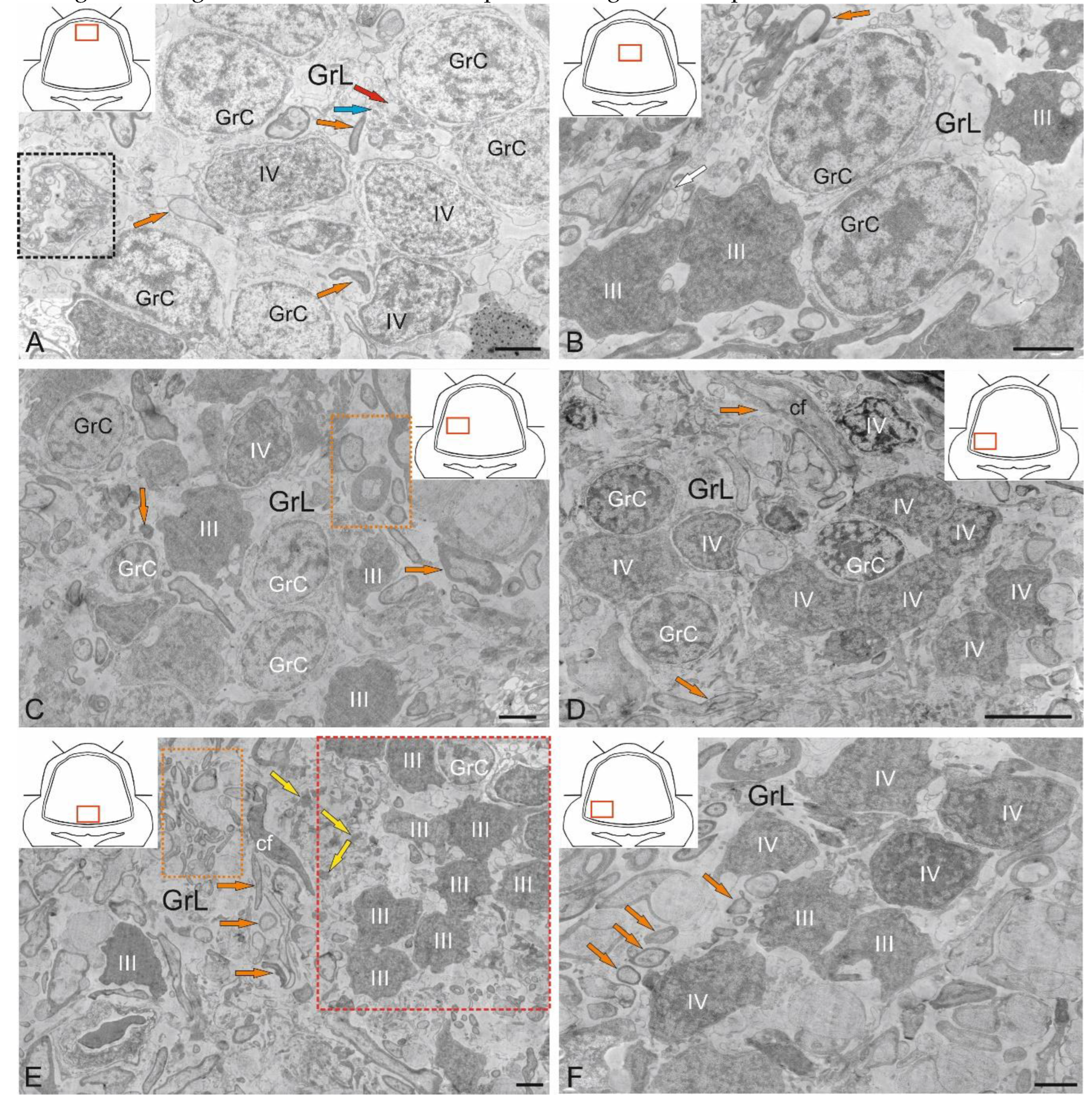

Figure 10.

Ultrastructural organization of the granular layer of the cerebellum in juvenile chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta. A – Cells of the granular layer (GrL) of the dorsomedial part of the CC: granular cells (GrC); type IV aNSPCs – IV; cfs are indicated by orange arrows; mitochondria, by blue arrows; vacuoles, by red arrows; a fragment of a lysed cell is outlined by the black dotted rectangle. B – in deeper region of GrL; type III aNSPCs – III; unmyelinated fiber is indicated by a white arrow; designations as in A; C – Diffuse distribution patterns of GrL and aNSPCs types III and IV in the lateral part of the CC: myelinated fibers are indicated by orange arrows; mixed fibers are outlined by the orange dotted rectangle. D – Clustering patterns of GrL and type IV aNSPCs distribution in the ventrolateral CC and climbing fibers (cf); myelinated cf are indicated by orange arrows. E – Adult-type constitutive neurogenic niches (in the red dotted rectangle) containing type III aNSPCs (III) in the mediobasal zone of the CC; clusters of climbing fibers (cf, in the orange dotted rectangle); myelinated cf are indicated by orange arrows. F – Mixed adult-type neurogenic niche formed by type III and IV aNSPCs from the ventrolateral CC; designations as in D and E. TEM. Scale bars: A–C; E, F 2 µm; D 5 µm.

Figure 10.

Ultrastructural organization of the granular layer of the cerebellum in juvenile chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta. A – Cells of the granular layer (GrL) of the dorsomedial part of the CC: granular cells (GrC); type IV aNSPCs – IV; cfs are indicated by orange arrows; mitochondria, by blue arrows; vacuoles, by red arrows; a fragment of a lysed cell is outlined by the black dotted rectangle. B – in deeper region of GrL; type III aNSPCs – III; unmyelinated fiber is indicated by a white arrow; designations as in A; C – Diffuse distribution patterns of GrL and aNSPCs types III and IV in the lateral part of the CC: myelinated fibers are indicated by orange arrows; mixed fibers are outlined by the orange dotted rectangle. D – Clustering patterns of GrL and type IV aNSPCs distribution in the ventrolateral CC and climbing fibers (cf); myelinated cf are indicated by orange arrows. E – Adult-type constitutive neurogenic niches (in the red dotted rectangle) containing type III aNSPCs (III) in the mediobasal zone of the CC; clusters of climbing fibers (cf, in the orange dotted rectangle); myelinated cf are indicated by orange arrows. F – Mixed adult-type neurogenic niche formed by type III and IV aNSPCs from the ventrolateral CC; designations as in D and E. TEM. Scale bars: A–C; E, F 2 µm; D 5 µm.

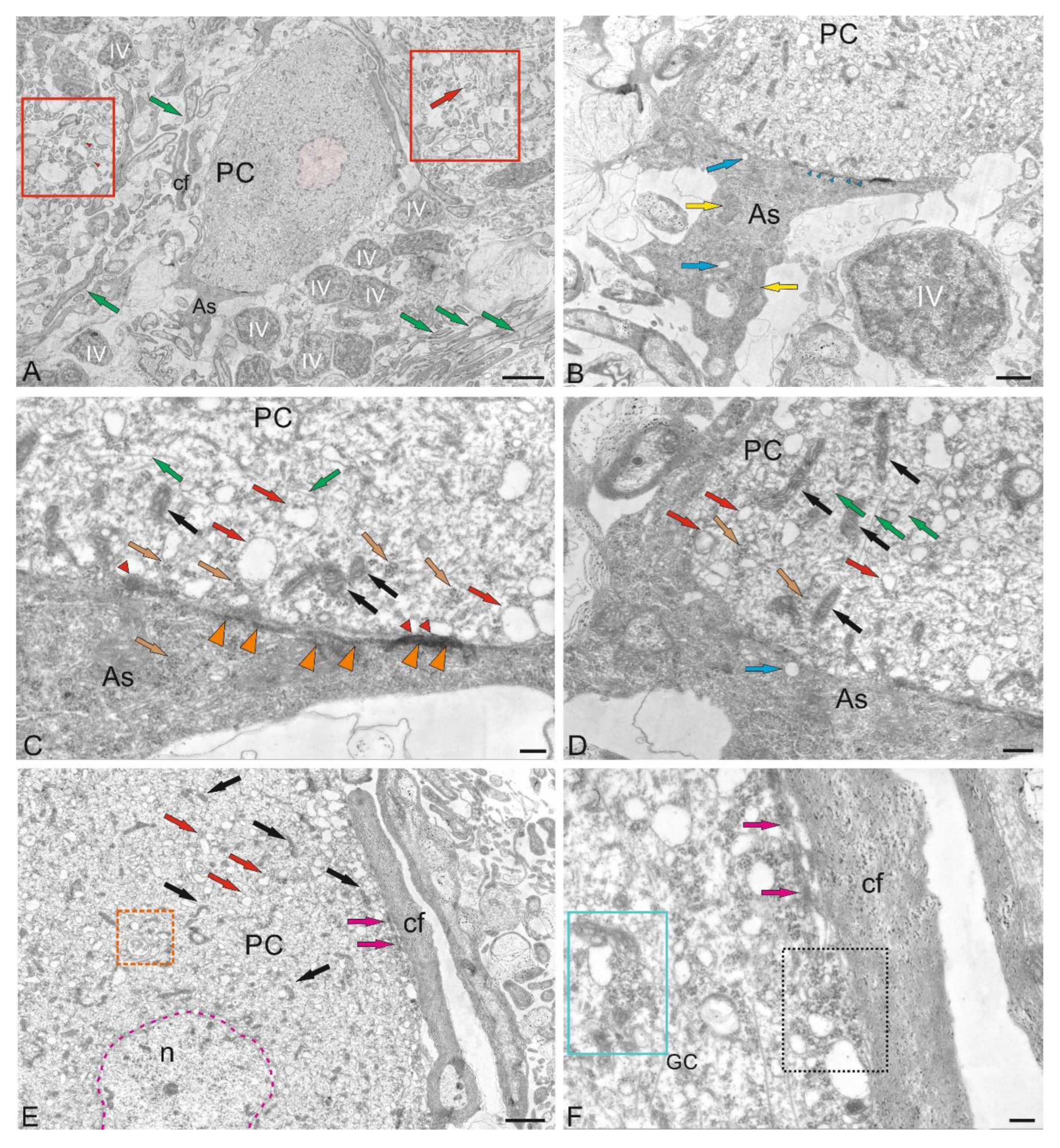

Figure 11.

Ultrastructural organization of granular layer cells in the cerebellum of juvenile chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta. A - Cells of the granular layer (GrL) of the dorsolateral part of the CC; the Golgi cell (GC) nucleus is highlighted in pink; mitochondria are indicated by black arrows; vacuoles, by red arrows; type IV aNSPCs are IV; cfs, by green arrows; nodular type cf termination patterns are outlined by the green rectangle and red dotted ovals; B – Enlarged GC fragment: nuclear membrane boundaries are indicated by red arrowheads; heterochromatin clusters, by blue arrows; the apical cell fragment is outlined by the inset in the red rectangle; actin filaments are indicated by yellow arrows; other designations are as in A. C – GC fragment at higher magnification; the boundaries of the nuclear membrane are indicated by orange arrows; ribosome clusters, by blue arrows; the inset (outlined by a magenta dotted square) shows the cisternae of the Golgi apparatus (white arrow): other designations are as in A. D – Astrocyte (As); the nucleus is highlighted in yellow; the nucleolus is indicated by the magenta arrow; vacuoles, by red arrows; type IV aNSPCs – IV; the patterns of sprouting fibers are outlined by blue rectangles. E – Enlarged fragment of As contacting type IV aNSPCs (the contact area is indicated by a yellow arrow); binuclear type IV aNSPCs (nuclei are marked n); patterns of granular cell apoptosis are outlined by the black dotted rectangle; F – As fragment at higher magnification; ribosome complexes are indicated by blue arrows; actin filaments, by yellow arrows; mitochondria, by black arrows. TEM. Scale bars: A – 3 µm; B, D – 2 µm; C, E, F – 1 µm.

Figure 11.