Submitted:

13 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

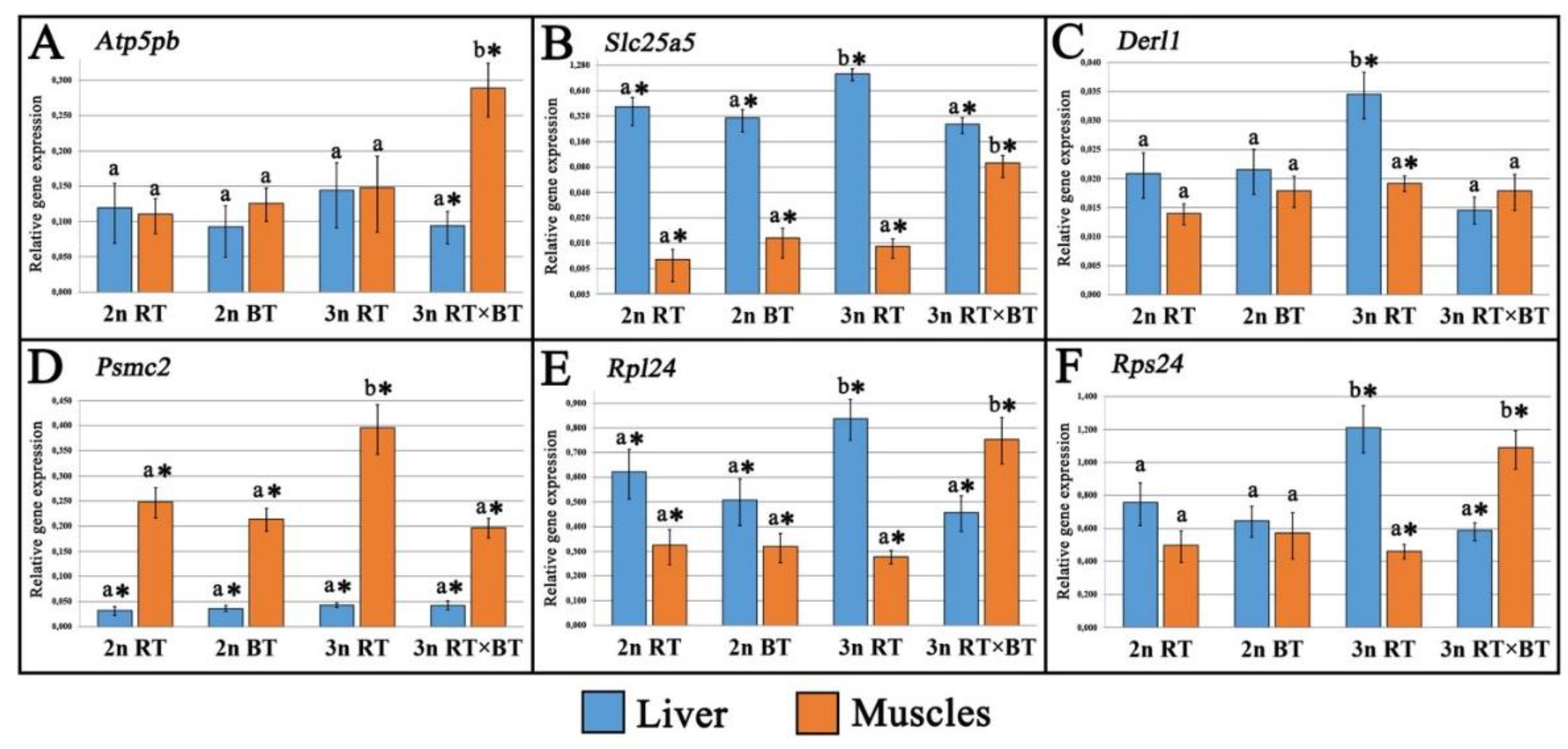

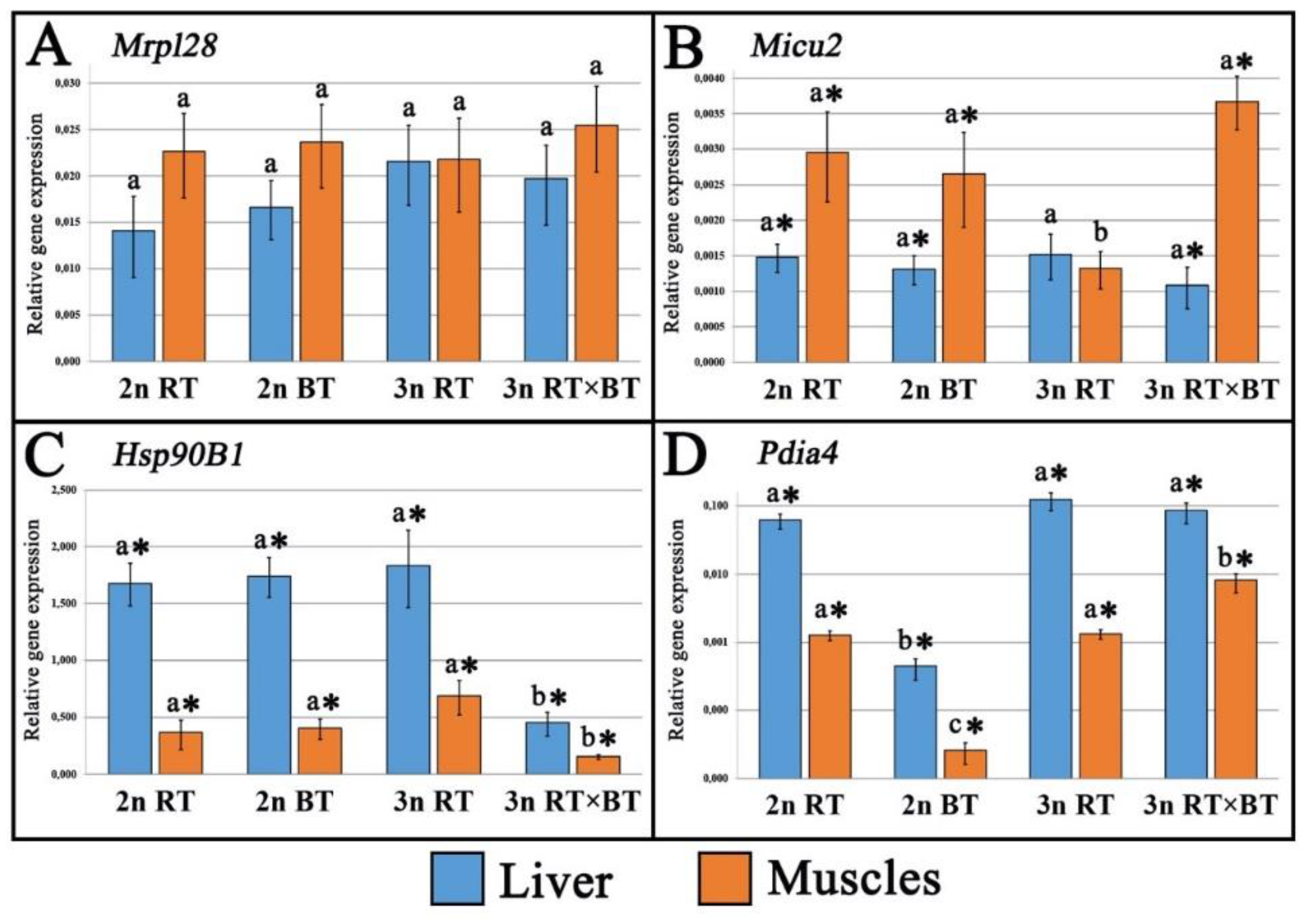

The transcriptomic effects of hybridization and triploidization were investigated in the diploid and triploid rainbow trout, diploid brook trout and in the triploid hybrids of rainbow trout and brook trout. The examined fish were reared under identical conditions for about two and a half years after hatching. Expression of ten genes involved in cellular respiration (Atp5bp, Slc25a5), mitochondrial functioning (Mrpl28, Micu2), ribosome biogenesis (Rpl24, Rps24), proteasome-mediated protein turnover (Derl1, Psmc2) and protein chaperoning (Hsp90B1, Pdia4) were studied in liver and muscle tissues. Most of the analyzed genes displayed comparable expression levels across all the fish groups, with triploid hybrids showing expression patterns more similar to the purebred diploid trout. Compared to all other fish groups, purebred triploid rainbow trout exhibited significant upregulation of Slc25a5, Derl1, Rps24 and Rpl24 genes in liver and downregulation of Micu2 gene muscles. In turn, triploid hybrids showed marked upregulation of Atp5pb, Slc25a5, Rpl24, Rps24 and Pdia4 genes in muscle and downregulation of Hsp90B1 gene in both liver and muscle when compared to all the fish groups examined. Although protein synthesis- and energy-related genes were upregulated in the muscles of triploid hybrids, the recoded growth performance data did not indicate clear evidence of growth heterosis, suggesting that the potential benefits of increased heterozygosity in this cross may be counterbalanced by metabolic inefficiencies. Three- to fourfold downregulation of heat-shock protein genes was observed in both tissues of triploid hybrids compared with purebred diploid and triploid trout, indicating possible maladaptive genomic incompatibilities usually observed in salmonid fish hybrids that may reduce their heat tolerance under aquaculture conditions. The obtained results also revealed significant upregulation of genes linked to liver protein synthesis and energy production, along with muscle protein turnover in the triploid rainbow trout, supporting the hypothesis that the higher energy demands for maintaining proper protein concentrations in the larger cytoplasmic cell volume of triploid fishes may be met through enhanced protein metabolism.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

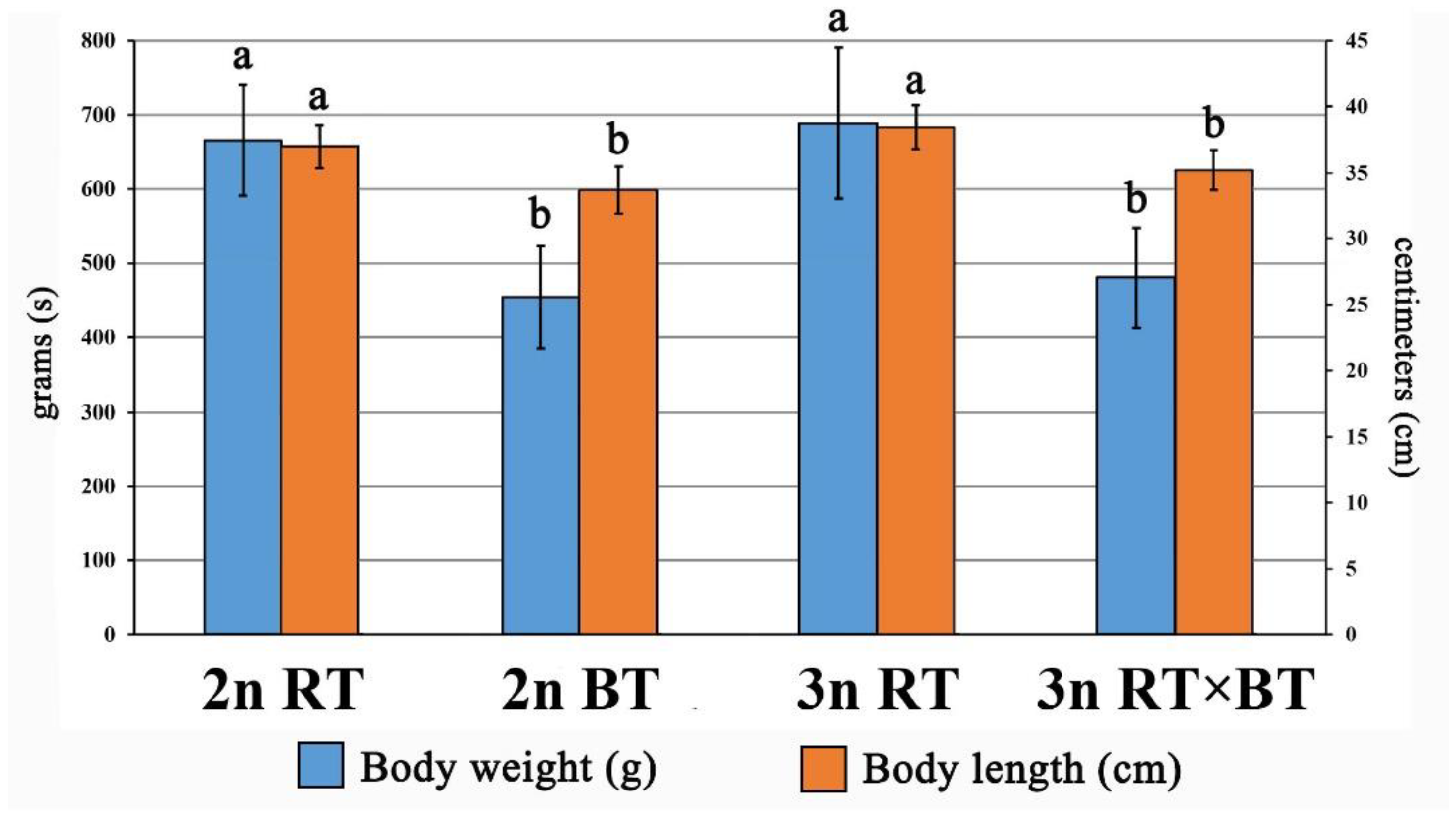

2.1. Growth Performance of Examined Fish

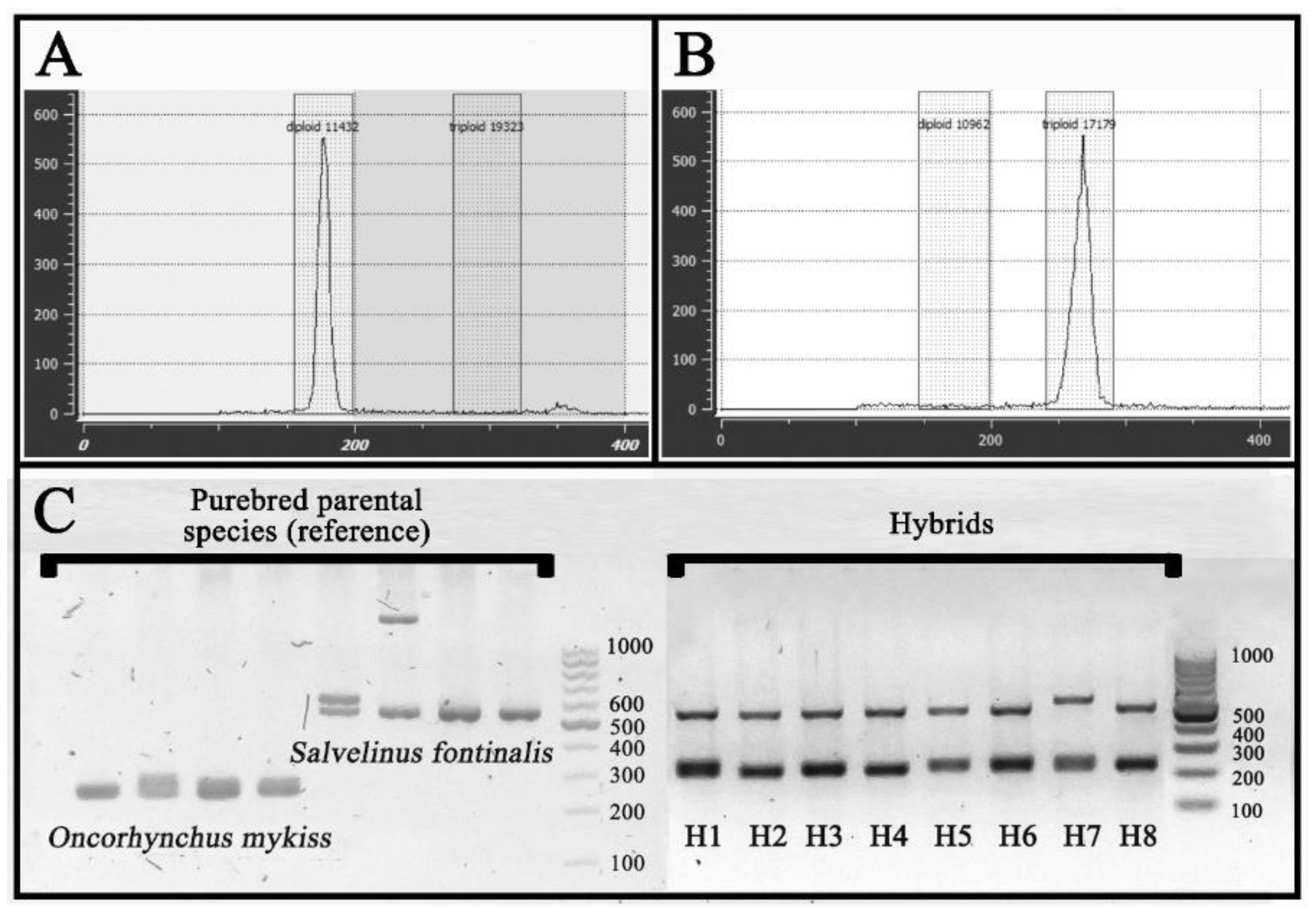

2.2. Ploidy and Hybridization Confirmation

2.2. Gene Expression Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethics

4.2. Fish Origin and Maintenance

4.3. Ploidy, Genetic Sex and Hybridization Verification

4.4. RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis, and Real-Time PCR Analysis

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bartley, D.M.; Rana, K.; Immink, A.J. The use of inter-specific hybrids in aquaculture and fisheries. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2000, 10, 325–337. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Lee, S.G.; Yusoff, F.M.; Rafiquzzaman, S.M. Hybridization and its application in aquaculture. In: Sex control in aquaculture; pp. 163–178, 2018.

- Wang, S.; Tang, C.; Tao, M.; Qin, Q.; Zhang, C.; Luo, K.; …; Liu, S. Establishment and application of distant hybridization technology in fish. Sci. China Life Sci. 2018, 62, 22–45.

- Houston, R.D.; Bean, T.P.; Macqueen, D.J.; Gundappa, M.K.; Jin, Y.H.; Jenkins, T.L.; …; Robledo, D. Harnessing genomics to fast-track genetic improvement in aquaculture. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2020, 21(7), 389–409.

- Liu, S. (Ed.). Fish distant hybridization. Singapore: Springer, 2022.

- Ren, L.; Gao, X.; Cui, J.; Zhang, C.; Dai, H.; Luo, M.; …; Liu, S. Symmetric subgenomes and balanced homoeolog expression stabilize the establishment of allopolyploidy in cyprinid fish. BMC Biol. 2022a, 20(1), 200.

- Şahin, Ş.A.; Başçınar, N.; Kocabaş, M.; Tufan, B.; Köse, S.; Okumuş, İ. Evaluation of meat yield, proximate composition and fatty acid profile of cultured brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis Mitchill, 1814) and Black Sea Trout (Salmo trutta labrax Pallas, 1811) in comparison with their hybrid. Tur. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2011, 11(2), 261–271.

- Arias, C.R.; Cai, W.; Peatman, E.; Bullard, S.A. Catfish hybrid Ictalurus punctatus × I. furcatus exhibits higher resistance to columnaris disease than the parental species. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2012, 100(1), 77–81. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, T.W.; Lerøy, H.; Hansen, T.J.; Skjæraasen, J.E.; Tronci, V.; Pedrosa, C.P.; …; Nilsen, T.O. Triploid Atlantic salmon and triploid Atlantic salmon × brown trout hybrids have better freshwater and early seawater growth than diploid counterparts. Aquaculture 2021, 540, 736698.

- Adams, M.B.; Maynard, B.T.; Rigby, M.; Wynne, J.W.; Taylor, R.S. Reciprocal hybrids of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) x brown trout (S. trutta) confirm a heterotic response to experimentally induced amoebic gill disease (AGD). Aquaculture 2023, 572, 739535. [CrossRef]

- Pourkhazaei, F.; Keivany, Y.; Dorafshan, S.; Heyrati, F.P.; Holtz, W.; Brenig, B.; Komrakova, M. Expression of growth and immunity genes during early developmental stages of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and brown trout (Salmo trutta) hybrids. Aquaculture 2025, 606, 742595. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N. Hybrid incompatibility genes: remnants of a genomic battlefield? Trends Genet. 2010, 26(7), 317–325. [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, S.; Barbash, D.A. The genetics of hybrid incompatibilities. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2011, 45(1), 331–355.

- Burton, R.S.; Pereira, R.J.; Barreto, F.S. Cytonuclear genomic interactions and hybrid breakdown. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2013, 44(1), 281–302. [CrossRef]

- Piferrer, F.; Beaumont, A.; Falguière, J.C.; Flajšhans, M.; Haffray, P.; Colombo, L. Polyploid fish and shellfish: production, biology and applications to aquaculture for performance improvement and genetic containment. Aquaculture 2009, 293(3–4), 125–156. [CrossRef]

- Blanc, J.M.; Vallée, F.; Maunas, P.; Fouriot, J.P. Maternal variation in juvenile survival and growth of triploid hybrids between female rainbow trout and male brown trout and brook charr. Aquac. Res. 2005a, 36(2), 120–129. [CrossRef]

- Pandian, T.A.; Koteeswaran, R. Ploidy induction and sex control in fish. Hydrobiologia 1998, 384, 167–243. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Gui, J. Natural and artificial polyploids in aquaculture. Aquac. Fish. 2017, 2(3), 103–111. [CrossRef]

- Arai, K. Fujimoto, T. Genomic constitution and atypical reproduction in polyploid and unisexual lineages of the Misgurnus loach, a teleost fish. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2013, 140(2-4), 226–240. [CrossRef]

- Blanc, J.M., Poisson, H., Vallée, F. Covariation between diploid and triploid progenies from common breeders in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum). Aquac. Res. 2001, 32(7), 507–516. [CrossRef]

- Maxime, V. The physiology of triploid fish: cur2t knowledge and comparisons with diploid fish. Fish Fish. 2008, 9(1), 67–78.

- Cotter, D.; O'Donovan, V.; O'Maoiléidigh, N.; Rogan, G.; Roche, N.; Wilkins, N.P. An evaluation of the use of triploid Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) in minimising the impact of escaped farmed salmon on wild populations. Aquaculture 2000, 186(1–2), 61–75. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, T.W.; Fjelldal, P.G.; Hansen, T.; Mayer, I. Welfare considerations of triploid fish. Rev. Fish. Sci. 2012, 20(4), 192–211. [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Li, W.; Tao, M.; Qin, Q.; Luo, J.; Chai, J.; …; Liu, S. Homoeologue expression insights into the basis of growth heterosis at the intersection of ploidy and hybridity in Cyprinidae. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6(1), 27040.

- Ren, L.; Tang, C.; Li, W.; Cui, J.; Tan, X.; Xiong, Y.; …; Liu, S. Determination of dosage compensation and comparison of gene expression in a triploid hybrid fish. BMC Genomics 2017, 18, 1–14.

- Ren, L.; Li, W.; Qin, Q.; Dai, H.; Han, F.; Xiao, J.; …; Liu, S. The subgenomes show asymmetric expression of alleles in hybrid lineages of Megalobrama amblycephala × Culter alburnus. Genome Res. 2019a, 29(11), 1805–1815.

- Li, W.; Liu, J.; Tan, H.; Luo, L.; Cui, J.; Hu, J.; …; Liu, S. Asymmetric expression patterns reveal a strong maternal effect and dosage compensation in polyploid hybrid fish. BMC Genomics 2018, 19, 1–14.

- Renaut, S.; Nolte, A.W.; Bernatchez, L. Gene expression divergence and hybrid misexpression between lake whitefish species pairs (Coregonus spp., Salmonidae). Mol. Biol. Evol. 2009, 26(4), 925–936. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Wang, D.; Guo, Y.; Tang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Li, S.; …; Lin, H. Comparative transcriptome analysis of diploid and triploid hybrid groupers (Epinephelus coioides♀× E. lanceolatus♂) reveals the mechanism of abnormal gonadal development in triploid hybrids. Genomics 2019a, 111(3), 251–259.

- Huang, J.; Yang, M.; Liu, J.; Tang, H.; Fan, X.; Zhang, W.; …; Luo, J. Transcriptome analysis of high mortality phenomena in polyploid fish embryos: an allotriploid embryo case study in hybrid grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus ♀ × Epinephelus lanceolatus ♂). Aquaculture 2023, 571, 739446.

- Mavarez, J.; Audet, C.; Bernatchez, L. Major disruption of gene expression in hybrids between young sympatric anadromous and resident populations of brook charr (Salvelinus fontinalis Mitchill). J. Evol. Biol. 2009, 22(8), 1708–1720. [CrossRef]

- Renaut, S.; Bernatchez, L. Transcriptome-wide signature of hybrid breakdown associated with intrinsic reproductive isolation in lake whitefish species pairs (Coregonus spp., Salmonidae). Heredity 2011, 106(6), 1003–1011. [CrossRef]

- Dion-Côté, A.M.; Renaut, S.; Normandeau, E.; Bernatchez, L. RNA-seq reveals transcriptomic shock involving transposable elements reactivation in hybrids of young lake whitefish species. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014, 31(5), 1188–1199. [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, J.L.; Araújo, H.A.; Smith, J.L.; Schluter, D.; Devlin, R.H. Incomplete reproductive isolation and strong transcriptomic response to hybridization between sympatric sister species of salmon. Proc. R. Soc. B 2021, 288(1950), 20203020. [CrossRef]

- Ching, B.; Jamieson, S.; Heath, J.W.; Heath, D.D.; Hubberstey, A. Transcriptional differences between triploid and diploid Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) during live Vibrio anguillarum challenge. Heredity 2010, 104(2), 224–234. [CrossRef]

- Chatchaiphan, S.; Srisapoome, P.; Kim, J.H.; Devlin, R.H.; Na-Nakorn, U. De novo transcriptome characterization and growth-related gene expression profiling of diploid and triploid bighead catfish (Clarias macrocephalus Günther, 1864). Mar. Biotechnol. 2017, 19, 36–48. [CrossRef]

- Christensen, K.A.; Sakhrani, D.; Rondeau, E.B.; Richards, J.; Koop, B.F.; Devlin, R.H. Effect of triploidy on liver gene expression in coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) under different metabolic states. BMC Genomics 2019, 20, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Odei, D.K.; Hagen, Ø.; Peruzzi, S.; Falk-Petersen, I.B.; Fernandes, J.M. Transcriptome sequencing and histology reveal dosage compensation in the liver of triploid pre-smolt Atlantic salmon. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10(1), 16836. [CrossRef]

- Meiler, K.A.; Cleveland, B.; Radler, L.; Kumar, V. Oxidative stress-related gene expression in diploid and triploid rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) fed diets with organic and inorganic zinc. Aquaculture 2021, 533, 736149. [CrossRef]

- Panasiak, L.; Kuciński, M.; Hliwa, P.; Pomianowski, K.; Ocalewicz, K. Telomerase activity in somatic tissues and ovaries of diploid and triploid rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) females. Cells 2023, 12(13), 1772. [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024 – Blue Transformation in action. Rome. 2024.

- Crane, M.; Hyatt, A. Viruses of fish: an overview of significant pathogens. Viruses 2011, 3(11), 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ødegård, J.; Baranski, M.; Gjerde, B.; Gjedrem, T. Methodology for genetic evaluation of disease resistance in aquaculture species: challenges and future prospects. Aquaculture Res. 2011, 42, 103–114. [CrossRef]

- Yáñez, J.M.; Houston, R.D.; Newman, S. Genetics and genomics of disease resistance in salmonid species. Front. Genet. 2014, 5, 415. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, S.C.; Woolliams, J.A. Genomics and disease resistance studies in livestock. Livest. Sci. 2014, 166, 190–198. [CrossRef]

- Dorson, M.; Chevassus, B.; Torhy, C. Comparative susceptibility of three species of char and of rainbow trout × char triploid hybrids to several pathogenic salmonid viruses. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 1991, 11(3), 217–224. [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, E.M. Manipulation of reproduction in farmed fish. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 1996, 42(1–4), 381–392. [CrossRef]

- Kuciński, M.; Trzeciak, P.; Pirtań, Z.; Jóźwiak, W.; Ocalewicz, K. The phenotype, sex ratio and gonadal development in triploid hybrids of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss ♀) and brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis ♂). Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2025, 272, 107659. [CrossRef]

- Salmocross. An innovative research and implementation project in the aquaculture. https://salmocross.pl/en Accessed 21 June 2025.

- Piferrer, F.; Beaumont, A.; Falguière, J.C.; Flajšhans, M.; Haffray, P.; Colombo, L. Polyploid fish and shellfish: production, biology and applications to aquaculture for performance improvement and genetic containment. Aquaculture 2009, 293(3–4), 125–156. [CrossRef]

- Scheerer, P.D.; Thorgaard, G.H. Increased survival in salmonid hybrids by induced triploidy. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1983, 40(11), 2040–2044. [CrossRef]

- Thorgaard, G.H. Ploidy manipulation and performance. Aquaculture 1986, 57(1–4), 57–64.

- Gray, A.K.; Evans, M.A.; Thorgaard, G.H. Viability and development of diploid and triploid salmonid hybrids. Aquaculture 1993, 112(2–3), 125–142. [CrossRef]

- Mallet, J. Hybrid speciation. Nature 2007, 446(7133), 279–283.

- Van de Peer, Y.; Maere, S.; Meyer, A. The evolutionary significance of ancient genome duplications. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10(10), 725–732. [CrossRef]

- Larsen, P.A.; Marchán-Rivadeneira, M.R.; Baker, R.J. Natural hybridization generates mammalian lineage with species characteristics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010, 107(25), 11447–11452. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Luo, M.; Li, S.; Tao, M.; Ye, X.; Duan, W.; …; Liu, S. A comparative study of distant hybridization in plants and animals. Sci. China Life Sci. 2018, 61, 285–309.

- Ren, L.; Yan, X.; Cao, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Gao, X.; …; Liu, S. Combined effects of dosage compensation and incomplete dominance on gene expression in triploid cyprinids. DNA Res. 2019b, 26(6), 485–494.

- Galitski, T.; Saldanha, A.J.; Styles, C.A.; Lander, E.S.; Fink, G.R. Ploidy regulation of gene expression. Science 1999, 285(5425), 251–254.

- Birchler, J.A.; Bhadra, U.; Bhadra, M.P.; Auger, D.L. Dosage-dependent gene regulation in multicellular eukaryotes: implications for dosage compensation, aneuploid syndromes, and quantitative traits. Dev. Biol. 2001, 234(2), 275–288. [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.; Levy, A.A.; Fahima, T.; Korol, A. Genomic asymmetry in allopolyploid plants: wheat as a model. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63(14), 5045–5059. [CrossRef]

- Leggatt, R.A.; Iwama, G.K. Occurrence of polyploidy in the fishes. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2003, 13, 237–246. [CrossRef]

- Matos, I.; Machado, M.P.; Schartl, M.; Coelho, M.M. Gene expression dosage regulation in an allopolyploid fish. PLoS One 2015, 10(3), e0116309. [CrossRef]

- Pala, I.; Coelho, M.M.; Schartl, M. Dosage compensation by gene-copy silencing in a triploid hybrid fish. Curr. Biol. 2008, 18(17), 1344–1348. [CrossRef]

- Benfey, T.J. The physiology and behavior of triploid fishes. Rev. Fish. Sci. 1999, 7(1), 39–67. [CrossRef]

- van de Pol, I.L.; Flik, G.; Verberk, W.C. Triploidy in zebrafish larvae: Effects on gene expression, cell size and cell number, growth, development and swimming performance. PLOS One 2020, 15(3), e0229468. [CrossRef]

- Lucchesi, J.C.; Kelly, W.G.; Panning, B. Chromatin remodeling in dosage compensation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2005, 39(1), 615–651. [CrossRef]

- Kelley, R.L.; Kuroda, M.I. Noncoding RNA genes in dosage compensation and imprinting. Cell 2000, 103(1), 9–12. [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.W.; Huang, K.; Yang, C.; Kang, C.S. Non-coding RNAs as regulators in epigenetics. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 37(1), 3–9.

- Johnson, R.M.; Shrimpton, J.M.; Cho, G.K.; Heath, D.D. Dosage effects on heritability and maternal effects in diploid and triploid Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha). Heredity 2007, 98(5), 303–310. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.C.; Fjelldal, P.G.; Solberg, M.F.; Hansen, T.; Glover, K.A. Ploidy elicits a whole-genome dosage effect: growth of triploid Atlantic salmon is linked to the genetic origin of the second maternal chromosome set. BMC Genet. 2017, 18, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.R.X.; Liao, Z.Y.; Brock, J.R.; Du, K.; Li, G.Y.; Chen, Z.Q.; …; Zhang, H.H. Maternal dominance contributes to sub-genome differentiation in allopolyploid fishes. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14(1), 8357.

- Yang, C.; Dai, C.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, X.; Xu, X.; …; Liu, S. Different ploidy-level hybrids derived from female common carp × male topmouth culter. Aquaculture 2025, 594, 741366.

- Shrimpton, J.M.; Sentlinger, A.M.; Heath, J.W.; Devlin, R.H.; Heath, D.D. Biochemical and molecular differences in diploid and triploid ocean-type Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) smolts. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2007, 33, 259–268. [CrossRef]

- Hegarty, M.J.; Barker, G.L.; Wilson, I.D.; Abbott, R.J.; Edwards, K.J.; Hiscock, S.J. Transcriptome shock after interspecific hybridization in Senecio is ameliorated by genome duplication. Curr. Biol. 2006, 16(16), 1652–1659. [CrossRef]

- Van de Peer, Y.; Mizrachi, E.; Marchal, K. The evolutionary significance of polyploidy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2017, 18(7), 411–424. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Paterson, A.H. Genome and gene duplications and gene expression divergence: a view from plants. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1256(1), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, Y. Fine-tuning the expression of duplicate genes by translational regulation in Arabidopsis and maize. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 534. [CrossRef]

- Meeus, S.; Šemberová, K.; De Storme, N.; Geelen, D.; Vallejo-Marín, M. Effect of whole-genome duplication on the evolutionary rescue of sterile hybrid monkeyflowers. Plant Commun. 2020, 1(6). [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Zhang, H.; Luo, M.; Gao, X.; Cui, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S. Heterosis of growth trait regulated by DNA methylation and miRNA in allotriploid fish. Epigenet. Chromatin 2022a, 15(1), 19. [CrossRef]

- Schnable, J.C.; Springer, N.M.; Freeling, M. Differentiation of the maize subgenomes by genome dominance and both ancient and ongoing gene loss. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, 108(10), 4069–4074. [CrossRef]

- Bird, K.A.; VanBuren, R.; Puzey, J.R.; Edger, P.P. The causes and consequences of subgenome dominance in hybrids and recent polyploids. New Phytol. 2018, 220(1), 87–93. [CrossRef]

- Emery, M.; Willis, M.M.S.; Hao, Y.; Barry, K.; Oakgrove, K.; Peng, Y.; …; Conant, G.C. Preferential retention of genes from one parental genome after polyploidy illustrates the nature and scope of the genomic conflicts induced by hybridization. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14(3), e1007267.

- Sloan, D.B.; Warren, J.M.; Williams, A.M.; Wu, Z.; Abdel-Ghany, S.E.; Chicco, A.J.; Havird, J.C. Cytonuclear integration and co-evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19(10), 635–648.

- Alger, E.I.; Edger, P.P. One subgenome to rule them all: underlying mechanisms of subgenome dominance. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2020, 54, 108–113. [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Xie, L.; Li, T.; Liu, S.; Xiao, J.; Hu, J.; …; Liu, Y. The formation of diploid and triploid hybrids of female grass carp × male blunt snout bream and their 5S rDNA analysis. BMC Genet. 2013, 14, 1–10.

- Yu, F.; Xiao, J.; Liang, X.; Liu, S.; Zhou, G.; Luo, K.; …; Zhu, Z. Rapid growth and sterility of growth hormone gene transgenic triploid carp. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2011, 56, 1679–1684.

- Hu, J.; Liu, S.; Xiao, J.; Zhou, Y.; You, C.; He, W.; …; Liu, Y. Characteristics of diploid and triploid hybrids derived from female Megalobrama amblycephala Yih × male Xenocypris davidi Bleeker. Aquaculture 2012, 364, 157–164.

- Xiao, J.; Fu, Y.; Wu, H.; Chen, X.; Liu, S.; Feng, H. MAVS of triploid hybrid of red crucian carp and allotetraploid possesses the improved antiviral activity compared with the counterparts of its parents. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019b, 89, 18–26. [CrossRef]

- Ignatz, E.H.; Braden, L.M.; Benfey, T.J.; Caballero-Solares, A.; Hori, T.S.; Runighan, C.D.; …; Rise, M.L. Impact of rearing temperature on the innate antiviral immune response of growth hormone transgenic female triploid Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 97, 656–668.

- Groszmann, M.; Gonzalez-Bayon, R.; Lyons, R.L.; Greaves, I.K.; Kazan, K.; Peacock, W.J.; Dennis, E.S. Hormone-regulated defense and stress response networks contribute to heterosis in Arabidopsis F1 hybrids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015, 112(46), E6397–E6406. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zeng, R.; Li, Y.; Zhao, M.; Chao, J.; Li, Y.; …; Liang, C. Gene expression analysis and SNP/InDel discovery to investigate yield heterosis of two rubber tree F1 hybrids. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6(1), 24984.

- Liu, X.; Liang, H.; Li, Z.; Liang, Y.; Lu, C.; Li, C.; …; Hu, G. Performances of the hybrid between CyCa nucleocytoplasmic hybrid fish and scattered mirror carp in different culture environments. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7(1), 46329.

- Birchler, J.A. Heterosis: the genetic basis of hybrid vigour. Nat. Plants 2015, 1(3), 1–2. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; Tao, M.; Long, Y.; Liu, Z.; …; Liu, Y. Elevated expressions of GH/IGF axis genes in triploid crucian carp. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2012, 178(2), 291–300.

- Blanc, J.M.; Maunas, P.; Vallée, F. Effect of triploidy on paternal and maternal variance components in brown trout, Salmo trutta L. Aquac. Res. 2005b, 36(10), 1026–1033. [CrossRef]

- Friars, G.W.; McMillan, I.; Quinton, V.M.; O'Flynn, F.M.; McGeachy, S.A.; Benfey, T.J. Family differences in relative growth of diploid and triploid Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). Aquaculture 2001, 192(1), 23–29. [CrossRef]

- Weber, G.M.; Wiens, G.D.; Welch, T.J.; Hostuttler, M.A.; Leeds, T.D. Comparison of disease resistance between diploid, induced-triploid, and intercross-triploid rainbow trout including trout selected for resistance to Flavobacterium psychrophilum. Aquaculture 2013, 410, 66–71. [CrossRef]

- Polonis, M.; Fujimoto, T.; Dobosz, S.; Zalewski, T.; Ocalewicz, K. Genome incompatibility between rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and sea trout (Salmo trutta) and induction of the interspecies gynogenesis. J. Appl. Genet. 2018, 59, 91–97. [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhang, H.; Gao, X.; Zhang, X.; Luo, M.; Ren, L.; Liu, S. Correlations of expression of nuclear and mitochondrial genes in triploid fish. G3 2022, 12(9), jkac197. [CrossRef]

- Shrimpton, J.M.; Heath, J.W.; Devlin, R.H.; Heath, D.D. Effect of triploidy on growth and ionoregulatory performance in ocean-type Chinook salmon: A quantitative genetics approach. Aquaculture 2012, 362, 248–254. [CrossRef]

- Kozłowski, J.; Konarzewski, M.; Gawelczyk, A.T. Cell size as a link between noncoding DNA and metabolic rate scaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003, 100(24), 14080–14085. [CrossRef]

- Fink, A.L. Chaperone-mediated protein folding. Physiol. Rev. 1999, 79(2), 425–449. [CrossRef]

- Wali, A.; Balkhi, M.H. Heat shock proteins, importance and expression in fishes. Eur. J. Biotechnol. Biosci. 2016, 4, 29–35.

- Mohanty, B.P.; Mahanty, A.; Mitra, T.; Parija, S.C.; Mohanty, S. Heat shock proteins in stress in teleosts. In: Asea, A.; Kaur, P. (eds) Regulation of Heat Shock Protein Responses. Heat Shock Proteins, 2018, vol. 13. Springer, Cham.

- Zheng, L.; Tanaka, H.; Abe, S. Proteomic analysis of inviable salmonid hybrids between female masu salmon Oncorhynchus masou masou and male rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss during early embryogenesis. J. Fish Biol. 2011, 78(5), 1508–1528. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Senda, Y.; Abe, S. Perturbation in protein expression of the sterile salmonid hybrids between female brook trout Salvelinus fontinalis and male masu salmon Oncorhynchus masou during early spermatogenesis. Anim. Rep. Sci. 2013, 138(3–4), 292–304. [CrossRef]

- Bonzi, L.C.; Monroe, A.A.; Lehmann, R.; Berumen, M.L.; Ravasi, T.; Schunter, C. The time course of molecular acclimation to seawater in a euryhaline fish. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11(1), 18127. [CrossRef]

- Jeyachandran, S.; Chellapandian, H.; Park, K.; Kwak, I.S. A review on the involvement of heat shock proteins (extrinsic chaperones) in response to stress conditions in aquatic organisms. Antioxidants 2023, 12(7), 1444. [CrossRef]

- Hulbert, A.J.; Else, P.L. Mechanisms underlying the cost of living in animals. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2000, 62(1), 207–235. [CrossRef]

- Czarnoleski, M.; Ejsmont-Karabin, J.; Angilletta, M.J. Jr; Kozlowski, J. Colder rotifers grow larger but only in oxygenated waters. Ecosphere 2015, 6(9), 1–5.

- O'Donnell, K.M.; MacRae, K.L.; Verhille, C.E.; Sacobie, C.F.; Benfey, T.J. Standard metabolic rate of juvenile triploid brook charr, Salvelinus fontinalis. Aquaculture 2017, 479, 85–90. [CrossRef]

- Daigle, N.J.; Sacobie, C.F.; Verhille, C.E.; Benfey, T.J. Triploidy affects postprandial ammonia excretion but not specific dynamic action in 1+ brook charr, Salvelinus fontinalis. Aquaculture 2021, 536, 736503. [CrossRef]

- Dill, K.A.; Ghosh, K.; Schmit, J.D. Physical limits of cells and proteomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011, 108(44), 17876–17882. [CrossRef]

- Marguerat, S.; Bähler, J. Coordinating genome expression with cell size. Trends Genet. 2012, 28 (11), 560–565. [CrossRef]

- Marguerat, S.; Schmidt, A.; Codlin, S.; Chen, W.; Aebersold, R.; Bähler, J. Quantitative analysis of fission yeast transcriptomes and proteomes in proliferating and quiescent cells. Cell 2012, 151(3), 671–683. [CrossRef]

- Dolfi, S.C.; Chan, L.L.Y.; Qiu, J.; Tedeschi, P.M.; Bertino, J.R.; Hirshfield, K.M.; …; Vazquez, A. The metabolic demands of cancer cells are coupled to their size and protein synthesis rates. Cancer Metab. 2013, 1, 1–13.

- Doyle, J.J.; Coate, J.E. Polyploidy, the nucleotype, and novelty: the impact of genome doubling on the biology of the cell. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2019, 180(1), 1–52. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K. The proteasome: overview of structure and functions. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B 2009, 85(1), 12–36. [CrossRef]

- Christianson, J.C.; Ye, Y. Cleaning up in the endoplasmic reticulum: ubiquitin in charge. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014, 21(4), 325–335. [CrossRef]

- Baßler, J.; Hurt, E. Eukaryotic ribosome assembly. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2019, 88(1), 281–306. [CrossRef]

- Perocchi, F.; Gohil, V.M.; Girgis, H.S.; Bao, X.R.; McCombs, J.E.; Palmer, A.E.; Mootha, V.K. MICU1 encodes a mitochondrial EF hand protein required for Ca²⁺ uptake. Nature 2010, 467(7313), 291–296. [CrossRef]

- Patron, M.; Checchetto, V.; Raffaello, A.; Teardo, E.; Reane, D.V.; Mantoan, M.; …; Rizzuto, R. MICU1 and MICU2 finely tune the mitochondrial Ca²⁺ uniporter by exerting opposite effects on MCU activity. Mol. Cell 2014, 53(5), 726–737.

- Shah, S.I.; Ullah, G. The function of mitochondrial calcium uniporter at the whole-cell and single mitochondrion levels in WT, MICU1 KO, and MICU2 KO cells. Cells 2020, 9(6), 1520. [CrossRef]

- Olsvik, P.A.; Vikeså, V.; Lie, K.K.; Hevrøy, E.M. Transcriptional responses to temperature and low oxygen stress in Atlantic salmon studied with next-generation sequencing technology. BMC Genomics 2013, 14, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Hardy, R.W. Rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. In: Nutrient Requirements and Feeding of Finfish for Aquaculture; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2002; pp. 184–202.

- Billard, R. Utilisation d'un système tris-glycocolle pour tamponner le dilueur d'insémination pour truite. Bull. Fr. Piscic. 1977, (264), 102–112. [CrossRef]

- Jagiełło, K.; Dobosz, S.; Zalewski, T.; Polonis, M.; Ocalewicz, K. Developmental competence of eggs produced by rainbow trout doubled haploids (DHs) and generation of the clonal lines. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2018, 53(5), 1176–1183. [CrossRef]

- From, J.; Rasmussen, G. A growth model, gastric evacuation, and body composition in rainbow trout, Salmo gairdneri Richardson, 1836. Dana 1984, 3(6), 11.

- Walsh, P.S.; Metzger, D.A.; Higuchi, R. Chelex 100 as a medium for simple extraction of DNA for PCR-based typing from forensic material. Biotechniques 2013, 54(3), 134–139. [CrossRef]

- Yano, A.; Nicol, B.; Jouanno, E.; Quillet, E.; Fostier, A.; Guyomard, R.; Guiguen, Y. The sexually dimorphic on the Y-chromosome gene (sdY) is a conserved male-specific Y-chromosome sequence in many salmonids. Evol. Appl. 2013, 6(3), 486–496.

- Rexroad III, C.E.; Palti, Y. Development of ninety-seven polymorphic microsatellite markers for rainbow trout. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2003, 132(6), 1214–1221. [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, E.; Fostier, A.; Bobe, J. Microarray-based analysis of fish egg quality after natural or controlled ovulation. BMC Genomics 2007, 8, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Men, X.; Yu, Y.; Li, B.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, C. Effects of transportation stress on antioxidation, immunity capacity and hypoxia tolerance of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquac. Rep. 2022b, 22, 100940. [CrossRef]

- Manor, M.L.; Weber, G.M.; Cleveland, B.M.; Yao, J.; Kenney, P.B. Expression of genes associated with fatty acid metabolism during maturation in diploid and triploid female rainbow trout. Aquaculture 2015, 435, 178–186. [CrossRef]

- Carrizo, V.; Valenzuela, C.A.; Zuloaga, R.; Aros, C.; Altamirano, C.; Valdés, J.A.; Molina, A. Effect of cortisol on the immune-like response of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) myotubes challenged with Piscirickettsia salmonis. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2021, 237, 110240. [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Meng, Y.; Tian, H.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Gongbao, C.; …; Ma, R. Effects of acute hypoxic stress on physiological and hepatic metabolic responses of triploid rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 921709.

- Zhou, Y.; Zhong, H.; Liu, S.; Yu, F.; Hu, J.; Zhang, C.; …; Liu, Y. Elevated expression of Piwi and piRNAs in ovaries of triploid crucian carp. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2014, 38(1–2), 1–9.

- Xu, K.; Wen, M.; Duan, W.; Ren, L.; Hu, F.; Xiao, J.; …; Liu, S. Comparative analysis of testis transcriptomes from triploid and fertile diploid cyprinid fish. Biol. Reprod. 2015, 92(4), 1–12.

- Ostberg, C. O.; Chase, D. M.; Hauser, L. Hybridization between yellowstone cutthroat trout and rainbow trout alters the expression of muscle growth-related genes and their relationships with growth patterns. PLoS One 2015, 10(10), e0141373. [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25(4), 402–408. [CrossRef]

- Vandesompele, J.; De Preter, K.; Pattyn, F.; Poppe, B.; Van Roy, N.; De Paepe, A.; Speleman, F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002, 3, 1–12.

| Gene | Primer Sequences | Amplicon size (bp) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATP synthase peripheral stalk-membrane subunit b (Atp5pb) | F: AAGAAGGAGCAGTGGAGGGC R: CACCATGTGGACCCTCTCCC |

108 | ENSOMYG00000009141, XM_021616957.2 |

| ADP/ATP translocase 2 (Slc25a5) | F: GGATTCTCCGTGTCGGTCCA R: GGACGGTATCGAAGGGGTAGG |

178 | ENSOMYG00000025595, XM_021561140.2 |

| Derlin1 (Derl1) | F: AACTGATTGGGAACCTGGTGGG R: GTGGCGCTCCAAACCCAGAC |

153 | ENSOMYG00000057377, XM_036935651.1 |

| 26S proteasome regulatory subunit 7 (Psmc2) | F: ATCAGGGTCATCGGCTCAGA R: GCCCCTCCAATAGCGTCAAT |

137 | [124] |

| 60S Ribosomal Protein L24 (Rpl24) | F: CAAGAAGGGCCAGTCTGAAG R: CAGGCTTCTGGTTCCTCTTG |

119 | [133] |

| 40S ribosomal protein S24 (Rps24) | F: AAACCGGCTGCTTCAGAGGAA R: GCCACCACCAAACTGTGTCC |

160 | ENSOMYG00000047442, XM_036986845.1 |

| Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L28 (Mrpl28) | F: CCAGGATGGCCTATGGGGAG R: GTCTAGTGCGCGAGCCGTTA |

175 | ENSOMYG00000021960, XM_021587405.2 |

| Mitochondrial calcium uptake protein 2 (Micu2) | F: GACAGTGCCTAAGGAAGGTATCA R: ACCATTCCTGCCAAAGAAGAAGG |

97 | ENSOMYG00000009310, XM_021617766.2 |

| Heat shock protein 90 β family member 1 (Hsp90B1) | F: TTGCGTGGAACTAAGGTGA R: CCAATGAACTGAGAGTGCT |

104 | [134] |

| Protein disulfide-isomerase A4 (Pdia4) | F: ATGAGAAAGCTTCACACACGCT R: CACCAGTGGCAGGATGTGTTTC |

92 | ENSOMYG00000007216, XM_021620393.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).