1. Introduction

Hybridogenesis is a reproductive strategy that consistently ensures the emergence of F1 hybrid individuals across successive generations. In the early germline cells (gonocytes) of these hybrids, one of the parental chromosome sets (subgenomes) is eliminated while the other is endoreplicated. This leads to the production of clonal (not recombined; asexual) gametes from one species and requires the contribution of recombined (sexual) gametes from the other species to renew the F1 hybrid progeny. Thus, hybridogenesis is a rare hemiclonal mode of reproduction, normally reliant on populations where both the hybrid taxa and at least one of its parental species coexist. It is observed in stick insects of the genus

Bacillus [

1], fish and amphibians [

2,

3,

4]. Eight examples are documented among fishes,

Poeciliopsis lucida-monacha, Cobitis hankugensis (siniensis)-Iksookimia longicorpa, Misgurnus anguillicaudatus,

Squalius alburnoides, Hexagrammos octogrammus-otakii (-agrammus), Hypseleotris spp., and amphibians,

Bufotes pseudoraddei baturae, P. esculentus, P. hispanicus and

P. grafi [

1,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. However, the western Palearctic water frog group is a notable exception, containing two confirmed hybridogenetic hybrids,

P. esculentus (

lessonae-ridibundus, LR genome) and

P. grafi (perezi-ridibundus, PR genome) sharing the

P. ridibundus (R) genome. Among them,

P. esculentus, possibly originally formed from crosses between (mostly male)

P. lessonae (LL) and (mostly female)

P. ridibundus (RR), is the most widespread taxon.

Pelophylax grafi appeared in southwestern France and northeastern Spain, where the R genome immigrated not with the species

P. ridibundus, but with the hybrid

P. esculentus, which was expanding its range [

16,

17,

18,

19].

Genome elimination occurs early in gametogenesis during gonad formation in developing tadpoles [

20,

21]. The earliest stage of gametogenesis in both sexes, known as pregametogenesis, is marked by the presence of specific precursor cells called gonocytes. In hybridogenesis, elimination of one subgenome and replication of the other occur exclusively within these cells. Genome elimination occurs during gonocyte interphase [

20,

21,

22,

23]. The expelled chromosomes or their fragments are enclosed in micronuclei formed by budding off from the main nucleus. After detachment to the gonocyte cytoplasm, they undergo heterochromatinization and are degraded by nucleophagy, ensuring that only the non-eliminated parental genome remains to be duplicated and passed on through clonal gametes [

20,

23,

24]. The gonocytes give rise to primary oocytes in females and spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) in males [

21]. Genome elimination has been extensively studied in

P. esculentus, first described in juvenile hybrid females during oogenesis [

25,

26]. Cytogenetic studies on gametogenesis in adult

P. esculentus females and males clearly showed which of the parental genomes was eliminated in early gonocytes and which genome is transmitted to the progeny [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

Cytogenetic studies on other hybridogenetic systems within the genus

Pelophylax, namely

P. grafi hybrid and its parental species

P. perezi, were recently published [

12]. Diploid somatic karyotypes of

P. perezi and

P. grafi have five pairs of large chromosomes and eight pairs of small chromosomes, similar to those of other

Pelophylax taxa [

12,

35,

36]. Karyotype analyses using genomic

in situ hybridization (GISH) and comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) revealed that the

P. grafi hybrid retains both parental chromosomal sets (subgenomes), confirming the F1 hybrid genome constitution [

12]. The absence of visible homologous recombination blocks between the parental subgenomes in

P. grafi confirmed hybridogenesis in this taxon, consistent with findings from previous studies on

P. esculentus [

35]. Similar results were obtained in a clonal fish, the Australian carp gudgeons

Hypseleotris spp. [

11,

37]. FISH with

P. ridibundus-specific pericentromeric RrS1 repeat showed similar distribution of this repeat among

P. ridibundus and

P. perezi chromosomes, which prevents their differentiation [

12,

33]. Nevertheless,

P. ridibundus chromosome no. 10 has larger interstitial telomeric repeat sites flanking the nucleolus organizing region than the corresponding chromosome of

P. perezi, enabling their recognition [

12]. The analysis of lampbrush chromosomes from

P. perezi revealed 13 fully paired bivalents [

12], similar to those of

P. ridibundus and

P. lessonae [

28,

38]. A comparison of lampbrush chromosome morphology showed four distinct homology groups among

P. perezi, P. ridibundus, and

P. lessonae. Thus, the unique marker structure pattern observed in lampbrush chromosomes of

P. perezi offers a useful tool for recognizing the genome transmitted by

P. grafi.

To examine possible mechanisms of genome elimination in

P. grafi, we investigated gametogenesis across multiple ontogenetic stages. Based on the composition of P-G populations and the karyotype of

P. grafi [

12], we hypothesized that the

P. perezi (P) subgenome might be selectively eliminated in gonocytes, resulting in clonal transmission of

P. ridibundus (R) chromosomes. This hypothesis had not been empirically tested, and we addressed it using CGH on chromosomal spreads from gonadal tissues of

P. grafi tadpoles.

Our objectives were: (1) to confirm that the perezi subgenome is preferentially eliminated during pregametogenesis, (2) to confirm the micronuclei-mediated way of genome elimination from gonocytes, (3) to check whether the elimination and endoreplication are accurate by examining the genetic diversity of gonocytes and micronuclei in gonocytes of tadpoles, and (4) to confirm that the ridibundus genome is the one transmitted to functional gametes in adults. To address objectives 1 to 3, we examined qualitatively and quantitatively both the chromosomal composition of gonocytes and the type of genome eliminated by micronuclei in hybrid P. grafi tadpoles obtained by P. grafi × P. perezi and P. perezi x P. ridibundus in vitro crosses. To reach goal 4, we examined the genome composition of diplotene oocytes from hybrid females, as well as SSCs and spermatocytes from hybrid males. Assuming that adult hybrid males and females transmit only the P. ridibundus subgenome, we performed artificial crosses between two P. grafi parents and genetically analyzed the genotypes of the resulting offspring.

4. Discussion

Genome elimination in P. grafi gonocytes. The F1 tadpoles from crosses between

P. perezi and

P. grafi carried a diploid RP genome, providing the first evidence that hybrids transmit the

ridibundus (R) genome in their gametes and eliminate the

perezi (P) genome. The P genome elimination was stage-specific: it started in gonocytes only at pro-metamorphosis and intensified during metamorphic climax, but was not fully completed before the end of metamorphosis. Even at late tadpole developmental stages, some gonocytes retained uneliminated P chromosomes, suggesting that genome elimination and stabilization are extended processes and may remain unfinished in some individuals. Our former investigations on female

P. esculentus showed that pregametogenesis is prolonged by about a year in comparison to the parental species [

44,

45]. However, the preliminary study on

P. grafi gonad development showed that – contrary to

P. esculentus – genome elimination does not cause such significant effects (Rozenblut-Kościsty et al. unpublished).

The rate and efficiency of

perezi chromosomes elimination varied across parental combinations, suggesting the influence of genetic and population-specific factors. We noticed that the most efficient P genome elimination occurred in crosses where hybrid mothers were donors of the R genome. In the primary cross between female

P. perezi and male

P. ridibundus (cross 12), gonocytes largely retained P chromosomes, with no clear evidence of systematic elimination. Such an effect has not been previously observed in hybrid offspring from primary

P. lessonae × P. ridibundus crosses, where

P. esculentus gonocytes preferentially eliminated one of the parental subgenomes, usually the

P. lessonae genome [

23,

33,

40,

46]. We also observed differences in the elimination rates between large and small P chromosomes. In crosses with maternal transmission of the R genome (crosses 18, 19, 24), gonocytes more frequently eliminated large P chromosomes, whereas this pattern was absent in tadpoles with paternal R genome origin (crosses 6 and 30). To account for this, we hypothesize that maternally inherited factors, such as mitochondrial DNA or germplasm components deposited in the oocyte, may influence the elimination of the paternal

perezi genome. These factors could be transmitted through zygotic and embryonic divisions into the germ cell lineage in yolk platelets, where primordial germ cells subsequently develop into gonocytes. It also appears likely that factors including genomic compatibility or population-specific genomic interactions modulate the efficiency of the elimination process [

47].

Micronuclei as carriers of the eliminated genome. Genomic composition of interphase gonocytes. Micronucleus formation in

P. grafi gonocytes represents a cytological mechanism of genome elimination in this hybrid, consistent with previous observations in

P. esculentus [

20,

22,

23,

40,

46]. A histological study of gonadal development in the parental species

P. perezi revealed that male and female gonocytes lack micronuclei in their cytoplasm (Rozenblut-Kościsty et al. unpublished). Most micronuclei in

P. grafi were round-shaped, with chromatin condensation resembling that of the main nucleus, suggesting relatively intact chromatin packaging. Highly heterochromatic or very dispersed chromatin was found in a minority of micronuclei, possibly representing advanced stages of chromatin degradation followed by autophagy, corroborating findings in

P. esculentus [

20]. Micronuclei were frequently observed in tadpoles from all crosses involving a hybrid parent, but were rare in tadpoles from

P. perezi × P. ridibundus cross. Across all crosses, gonocytes in

P. grafi tadpoles selectively eliminated the P subgenome, with micronuclei predominantly containing P chromosomes. However, the proportion of micronuclei with P chromatin varied among crosses. These results are consistent with the established model of hybridogenesis and gamete production in diploid adult individuals [

2,

4,

48].

Nonetheless, in over half of the tadpoles, we detected micronuclei inconsistent with the expected pattern of hybridogenesis. Despite the substantial occurrence of R micronuclei in some crosses, tadpoles continued to efficiently eliminate the P subgenome, as reflected in the chromosomal composition of their gonocytes. This suggests the existence of distinct cellular clones within the gonads that follow divergent pathways of genome elimination. We propose that cells undergoing such non-selective elimination of the R genome are likely removed via apoptosis, since gonocytes with a predominance of P-subgenome chromatin in their nuclei were only rarely observed. A similar phenomenon of both selective and non-selective genome elimination has been described in

P. esculentus, where non-selective elimination led to cell death. At both early and late developmental stages, apoptosis was observed in gonocytes, spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs), and meiotic cysts in both ovaries and testes, frequently associated with partial or complete gonadal sterility [

40,

46,

49]. In

P. grafi, we also recorded a small fraction of micronuclei containing mixed R/P subgenomes. Based on studies in

P. esculentus, which demonstrated that micronuclei typically enclose a single chromosome [

23,

40], we hypothesize that a similar pattern occurs in

P. grafi. However, the co-occurrence of both genome types within a single micronucleus may indicate either the presence of two distinct chromosomes or randomly trapped chromosome fragments. It remains unclear whether the presence of both subgenomes within individual micronuclei is a phenomenon exclusive to

P. grafi or if it also occurs in

P. esculentus. Our previous studies of micronuclear genome elimination in

P. esculentus employed FISH with a

P. ridibundus-specific probe, therefore could not detect the simultaneous presence of

P. ridibundus and

P. lessonae chromosomes [

23,

40,

46]. Typical

P. grafi gonocyte nuclei were accompanied by one or two micronuclei, while cases with 3–7 micronuclei were relatively rare. This indicates that the intensity of chromosome elimination in individual cells of

P. grafi is comparable to that observed in hybrid

P. esculentus, which also eliminates 13 chromosomes [

23,

40,

46]. In contrast, in hybridogenetic fishes of the genus

Hypseleotris, gonocytes contained on average four micronuclei, with numbers ranging from 1 to 7, while these hybrids typically eliminate 22–24 chromosomes [

11,

50]. The observation that gonocytes lack a number of micronuclei consistent with the haploid chromosome set may indicate rapid micronuclear degradation through autophagy [

20].

An intriguing finding in

P. grafi was the spatial separation of the P and R subgenomes in numerous interphase gonocyte nuclei containing micronuclei. To date, such subgenomic compartmentalization has not been demonstrated in the germline of hybrid frogs [

40], although it has been observed in gonocytes of hybrid

Hypseleotris fish or and in somatic cells during embryonic development of plant hybrids [

50,

51,

52]. The spatial segregation of R and P chromatin in gonocytes may represent a preparatory mechanism for selective subgenome elimination, with the genome designated for removal positioned peripherally within the nucleus, adjacent to the nuclear envelope [

51,

52]; however, this hypothesis requires further validation.

Genomic compositions of oocytes, spermatogenic stem cells (SSCs), and spermatocytes confirm accurate gametogenesis in adult P. grafi. In hybrid tadpoles, most early meiotic prophase I oocytes contained mixed R/P genomes, with only a minority showing a pure R subgenome. Complete P subgenome elimination with subsequent R subgenome endoreplication occurred only in crosses 18 and 24. Some oocytes displayed dispersed chromatin threads of both subgenomes, likely reflecting asynapsis or synaptonemal complex defects. Research on mouse oocytes has demonstrated that synapsis failures trigger the DNA damage checkpoint, leading to the removal of affected oocytes during prophase I [

53]. No direct data proves the same outcome for amphibians, and Dedukh et al. [

30,

46,

54] showed instances of both parental genomes in diplotene oocytes in P. esculentus. Moreover, P. esculentus individuals frequently exhibit polyploidy, which introduces additional complexities in genome elimination, leading to oocytes with variable chromosomal compositions and the formation of triploid offspring [

30,

55,

56]. Oocytes with mixed R/P genomes likely degenerated because in adult P. grafi females, lampbrush chromosomes in diplotene oocytes contained almost exclusively 13 R bivalents, supporting stable chromosomal compositions. SSCs of hybrid males predominantly exhibited diploid R mitoses, although occasional aneuploid chromosomal sets or the simultaneous presence of R and P chromosomes indicated sporadic errors. Ultimately, it turns out that adult hybrids of both sexes produce gametes carrying the R genome. All tadpoles from P. grafi × P. grafi crosses (crosses 16, 17, 26-29) were genetically identified as P. ridibundus neoforms, confirming exclusive R genome transmission. SSCs with haploid 13 R chromosomes and oocytes with 13 univalents confirm separation between genome elimination and endoreplication processes. The uniformity observed in P. grafi contrasts with the heterogeneous spermatogenesis seen in diploid P. esculentus adult males, in which most SSCs carried both R and L parental genomes or displayed aneuploidy, leading to the subsequent cellular degeneration [

40]. Highlighting the complexity of gametogenesis in these hybrids, the elimination of both parental subgenomes produced spermatozoa containing either haploid or diploid R sets, or alternatively, L chromosomes [

30,

32,

40,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61].

Chromosome morphology in the germline cells. Our CGH analysis of tadpole gonocytes and adult male SSCs revealed intact parental subgenomes, consistent with

P. grafi somatic karyotypes [

12]. However, some tadpole gonocytes and nearly all adult SSC metaphases displayed a small R chromosome with a

perezi probe signal in the pericentromeric region of the long arm, mirroring the signal on the small P chromosome from pair 12. This germline-specific signal, absent from somatic cells [

12], likely reflects chromatin remodeling rather than stable introgression, and its strong DAPI staining suggests AT-rich heterochromatin, possibly satellite DNA unmasked during germline epigenetic reprogramming [

21,

62,

63,

64,

65].

Potential threats to the stability of the P–G population. The P–G (

P. perezi –

P. grafi) system closely parallels the western European L–E system (

P. lessonae –

P. esculentus diploid hybrids) [[

64], this study]. A prevailing hypothesis proposes that, in

P. esculentus, the clonally inherited R genome may gradually accumulate deleterious mutations, which become lethal when homozygous [

67,

68,

69,

70]. This significantly contributes to the stability of the L-E system [

71]. The P-G system may be disrupted by the rapid spread of the invasive

P. ridibundus, resulting in mixed P–G–R populations and ultimately replacing native

P. perezi and

P. grafi populations at a high rate [

72]. A computational model proposed for L–E populations by Bove et al. (2014) [

71], where

P. esculentus hybrids produce clonal R gametes, predicts a collapse of such systems when

P. ridibundus individuals are introduced. Moreover, the geographical origin of

P. ridibundus influences the type of F1 hybrid offspring: Southern European lineages produce sterile

P. esculentus, while Central European ones yield fertile

P. esculentus [

73,

74]. Pustovalova et al. (2024) [

61] reported that

P. ridibundus hybridizes with local

P. lessonae, producing hybrids with reduced fertility and lacking genome elimination and endoreplication. Similarly, we found that hybrid tadpoles derived from primary crosses between native

P. perezi and

P. ridibundus were less efficient at eliminating the

perezi genome. As studies underscore that the invasive

P. ridibundus populations in France likely originate from multiple regions, including Eastern and Central Europe [

18], this can be catastrophic for the P–G complexes' existence. Although Hotz et al. (1994) [

66] and our findings revealed female-bias sex ratio, we cannot overlook the dangers of such invasion.

Mechanisms of genome elimination in Pelophylax hybrids. The determinants of selective genome elimination remain unclear, though maternal inheritance appears central. Most hybrid tadpoles in our study were female, supporting maternal origin of the R subgenome. Gametogenesis in

Pelophylax grafi is generally similar to that of the edible frog

P. esculentus [

20,

23,

30,

32,

40,

55,

59,

75]. This parallel indicates that programmed genome elimination follows the same general pattern in different

Pelophylax hybrid taxa, despite their independent hybrid origins. In this sense, the process can be considered evolutionarily conserved, as the non-

ridibundus genome (in

P. grafi the P genome) is systematically susceptible to elimination, whereas the R genome is preferentially retained and transmitted to gametes. While it remains uncertain whether elimination is a single-step or gradual process, evidence suggests that gonocytes undergo extended G0/G1 arrest, with eliminated genomes expelled as micronuclei, later degraded by autophagy [

21].

Figure 1.

Comparative genomic hybridization on mitotic (A-I) and meiotic (J-O) gonadal spreads of tadpoles obtained from in vitro crosses. A-D, F-O - female tadpole ovaries, E - tadpole male testes. P. ridibundus (R) chromosomes – red, P. perezi (P) chromosomes – green. Chromosomal compositions of gonocytes: (A) 13 R and 13 P chromosomes; (B) 13 R and 8 P chromosomes (4 big, 4 small); (C) 13 R and 7 P chromosomes (2 big and 5 small), among which small 12th P chromosome (pointed by large arrow) has bright-green pericentromeric region (indicated by small white arrow in inset); (D) 13 R and 4 P chromosomes (1 large, 3 small); (E) 12 R and 1 small P chromosome (no 6 or 7), male tadpole’s gonad; (F) 13 R and 1 P chromosomes (from pair 6, 7 or 11); (G) 13 R chromosomes, among which small R chromosome (large arrow) bears green pericentromeric signal of perezi probe (small white arrow in the inset); (H) a diploid set of 26 R chromosomes with an additional two small P chromosomes pointed by white arrows (pair 6 or 7); (I) diploid 26 R metaphase plate with three big chromosomes (first two from the 2nd pair, third from the 3rd pair) excluded in the inset with possible double chromosomal breakage on their p-arms (pointed by arrows). Meiotic figures obtained from female gonads: (J) leptotene/zygotene stage oocyte with mixed genomes; (K) leptotene/zygotene mixed genome oocyte with highly dispersed chromatin of meiotic prophase I chromosomes; (L) nearly purely R zygotene/pachytene oocyte with two green spots of P whole-genomic probe; (M) pure R leptotene/zygotene oocyte; (N) 26 R and 2 small P meiotic chromosomes forming bivalents; (O) 13 R diplotene bivalents, one small with two green spots located in the pericentromeric region (pointed by white arrows, in the inset). Figures A, B, D, J – cross 6 and 30, E, H, I, K, L, M, N, O – cross 18 and 24, C, G – cross 19, F – cross 12. Scale bars 10 µm.

Figure 1.

Comparative genomic hybridization on mitotic (A-I) and meiotic (J-O) gonadal spreads of tadpoles obtained from in vitro crosses. A-D, F-O - female tadpole ovaries, E - tadpole male testes. P. ridibundus (R) chromosomes – red, P. perezi (P) chromosomes – green. Chromosomal compositions of gonocytes: (A) 13 R and 13 P chromosomes; (B) 13 R and 8 P chromosomes (4 big, 4 small); (C) 13 R and 7 P chromosomes (2 big and 5 small), among which small 12th P chromosome (pointed by large arrow) has bright-green pericentromeric region (indicated by small white arrow in inset); (D) 13 R and 4 P chromosomes (1 large, 3 small); (E) 12 R and 1 small P chromosome (no 6 or 7), male tadpole’s gonad; (F) 13 R and 1 P chromosomes (from pair 6, 7 or 11); (G) 13 R chromosomes, among which small R chromosome (large arrow) bears green pericentromeric signal of perezi probe (small white arrow in the inset); (H) a diploid set of 26 R chromosomes with an additional two small P chromosomes pointed by white arrows (pair 6 or 7); (I) diploid 26 R metaphase plate with three big chromosomes (first two from the 2nd pair, third from the 3rd pair) excluded in the inset with possible double chromosomal breakage on their p-arms (pointed by arrows). Meiotic figures obtained from female gonads: (J) leptotene/zygotene stage oocyte with mixed genomes; (K) leptotene/zygotene mixed genome oocyte with highly dispersed chromatin of meiotic prophase I chromosomes; (L) nearly purely R zygotene/pachytene oocyte with two green spots of P whole-genomic probe; (M) pure R leptotene/zygotene oocyte; (N) 26 R and 2 small P meiotic chromosomes forming bivalents; (O) 13 R diplotene bivalents, one small with two green spots located in the pericentromeric region (pointed by white arrows, in the inset). Figures A, B, D, J – cross 6 and 30, E, H, I, K, L, M, N, O – cross 18 and 24, C, G – cross 19, F – cross 12. Scale bars 10 µm.

Figure 2.

Chromosomal distribution in gonadal spreads of tadpoles from in vitro crosses. A, C, E, G – percentage distribution of perezi (P, green) and ridibundus (R, red) chromosomes across different Gosner stages (28–45). Below each bar chart, lollipop plots show the raw counts of micronuclei with P, R, and mixed (P/R) genotypes. B, D, F, H – violin plot comparisons of P and R chromosome counts across Gosner stages. Dashed red lines indicate haploid (n = 13) and diploid (n = 26) chromosome numbers. Panel B contains the legend for all plots. (A) Crosses 6 and 30: the proportion of P chromosomes gradually decreases with advancing Gosner stages, while micronuclei counts increase in the middle stages and decline in the final category. (B) Violin plots for crosses 6 and 30: R chromosomes remain stable around 13 with low variability, while P chromosomes decrease and show broader distributions, indicating higher variability across mitoses. (C) Crosses 18 and 24: after stage 28, the percentage of P chromosomes drops sharply, then slightly rises in later stages without a clear trend. (D) Violin plots for crosses 18 and 24: R chromosomes remain stable near 13 except at stages 34–36, where a single value reaches 35, exceeding the plot’s window. P chromosome counts are markedly lower, with greater variability at stages 40–42. (E) Cross 19: only two stage categories were distinguished; in both, P chromosome percentages are lower than R. (F) Violin plots for cross 19: R chromosomes remain near 13; P chromosomes are consistently lower, with broader distributions in both categories. (G) Cross 12: no clear trend in P chromosome percentages is observed across stages. (H) Violin plots for cross 12: R chromosome counts are stable at 13, with slightly greater variability at stages 31–33. P chromosome counts are lower, with visibly reduced medians compared to R chromosomes.

Figure 2.

Chromosomal distribution in gonadal spreads of tadpoles from in vitro crosses. A, C, E, G – percentage distribution of perezi (P, green) and ridibundus (R, red) chromosomes across different Gosner stages (28–45). Below each bar chart, lollipop plots show the raw counts of micronuclei with P, R, and mixed (P/R) genotypes. B, D, F, H – violin plot comparisons of P and R chromosome counts across Gosner stages. Dashed red lines indicate haploid (n = 13) and diploid (n = 26) chromosome numbers. Panel B contains the legend for all plots. (A) Crosses 6 and 30: the proportion of P chromosomes gradually decreases with advancing Gosner stages, while micronuclei counts increase in the middle stages and decline in the final category. (B) Violin plots for crosses 6 and 30: R chromosomes remain stable around 13 with low variability, while P chromosomes decrease and show broader distributions, indicating higher variability across mitoses. (C) Crosses 18 and 24: after stage 28, the percentage of P chromosomes drops sharply, then slightly rises in later stages without a clear trend. (D) Violin plots for crosses 18 and 24: R chromosomes remain stable near 13 except at stages 34–36, where a single value reaches 35, exceeding the plot’s window. P chromosome counts are markedly lower, with greater variability at stages 40–42. (E) Cross 19: only two stage categories were distinguished; in both, P chromosome percentages are lower than R. (F) Violin plots for cross 19: R chromosomes remain near 13; P chromosomes are consistently lower, with broader distributions in both categories. (G) Cross 12: no clear trend in P chromosome percentages is observed across stages. (H) Violin plots for cross 12: R chromosome counts are stable at 13, with slightly greater variability at stages 31–33. P chromosome counts are lower, with visibly reduced medians compared to R chromosomes.

Figure 3.

Ploidy types and genomic compositions of gonocytes, their micronuclei in tadpoles, and SSCs in adult males. (A) Heatmap of ploidy levels and genomic compositions of metaphase plates across different hybrid crosses. (B) Heatmap of ploidy types and genomic compositions of SSCs in individual males. (C) Heatmap showing the percentage composition of micronuclei types (P – perezi genome, R – ridibundus genome, R/P – genomes from both species), grouped by in vitro crosses and Gosner stage categories. The color scale (see legend) represents the percentage of metaphase plates and micronuclei. The Y-axis represents the percentages, while the X-axis indicates the number of in vitro crosses or adult males. Colors correspond to ploidy and micronuclei percentages, as indicated in the legend.

Figure 3.

Ploidy types and genomic compositions of gonocytes, their micronuclei in tadpoles, and SSCs in adult males. (A) Heatmap of ploidy levels and genomic compositions of metaphase plates across different hybrid crosses. (B) Heatmap of ploidy types and genomic compositions of SSCs in individual males. (C) Heatmap showing the percentage composition of micronuclei types (P – perezi genome, R – ridibundus genome, R/P – genomes from both species), grouped by in vitro crosses and Gosner stage categories. The color scale (see legend) represents the percentage of metaphase plates and micronuclei. The Y-axis represents the percentages, while the X-axis indicates the number of in vitro crosses or adult males. Colors correspond to ploidy and micronuclei percentages, as indicated in the legend.

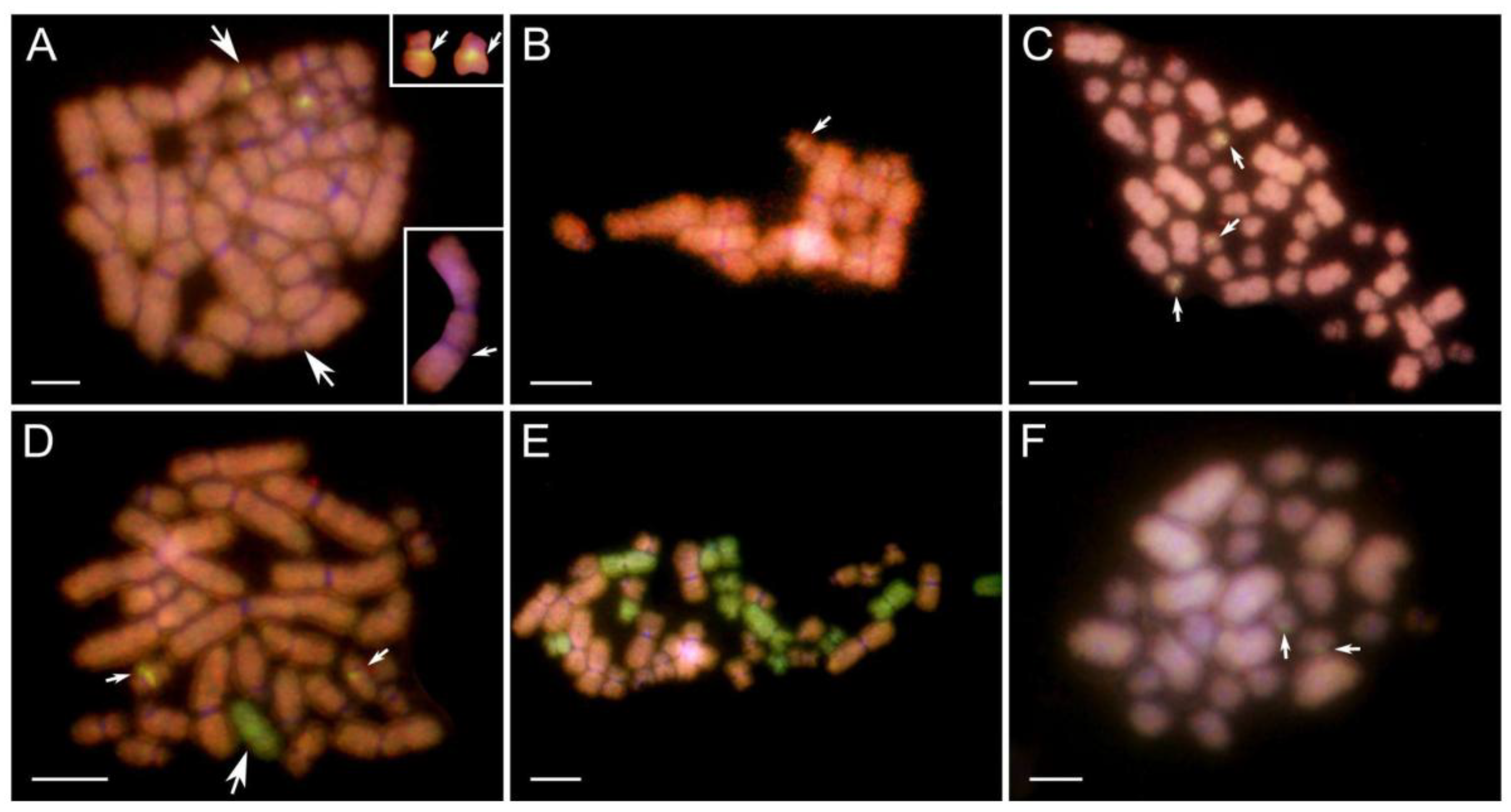

Figure 4.

Micronuclei formation and their genome composition in hybrid gonocytes differentiated with comparative genomic hybridization. P. ridibundus (R) chromatin – red, P. perezi (P) chromatin – green. (A) whole-mount DAPI-stained gonadal tissue fragment of P. grafi tadpole ovary with multiple micronuclei (pointed by arrows). (B) mixed genome interphase nucleus with two budding micronuclei with P subgenome. (C) mixed genome interphase nucleus showing one budding P micronucleus with bright green fluorescence indicating heterochromatinization and one P micronucleus with a faint signal. (D) mixed genome interphase nucleus with three budding P micronuclei, two of which exhibit bright green fluorescence, indicating heterochromatinization. (E) interphase nucleus predominantly with ridibundus genome (red) with 6 distinct P micronuclei. (F) nearly pure R interphase nucleus, with P signal on the edge (white arrow) and one irregularly shaped P micronucleus. (G) two pure R interphase nuclei with one P micronucleus present. (H) mitosis at prophase with segregated genomes of both species with one P micronucleus. (I) mitosis at prometaphase with decondensed P chromatin and P micronucleus. (J) mixed genome interphase nucleus with two micronuclei: one R and one only stained with DAPI. (K) P interphase nucleus with one R micronucleus. (L) P interphase nucleus with 6 R and one P micronuclei, all interconnected either to each other or to the main nucleus and with irregular shapes. (M) mixed R/P interphase gonocyte with a budding micronucleus with a mixed genome composition. Scale bars 10 µm.

Figure 4.

Micronuclei formation and their genome composition in hybrid gonocytes differentiated with comparative genomic hybridization. P. ridibundus (R) chromatin – red, P. perezi (P) chromatin – green. (A) whole-mount DAPI-stained gonadal tissue fragment of P. grafi tadpole ovary with multiple micronuclei (pointed by arrows). (B) mixed genome interphase nucleus with two budding micronuclei with P subgenome. (C) mixed genome interphase nucleus showing one budding P micronucleus with bright green fluorescence indicating heterochromatinization and one P micronucleus with a faint signal. (D) mixed genome interphase nucleus with three budding P micronuclei, two of which exhibit bright green fluorescence, indicating heterochromatinization. (E) interphase nucleus predominantly with ridibundus genome (red) with 6 distinct P micronuclei. (F) nearly pure R interphase nucleus, with P signal on the edge (white arrow) and one irregularly shaped P micronucleus. (G) two pure R interphase nuclei with one P micronucleus present. (H) mitosis at prophase with segregated genomes of both species with one P micronucleus. (I) mitosis at prometaphase with decondensed P chromatin and P micronucleus. (J) mixed genome interphase nucleus with two micronuclei: one R and one only stained with DAPI. (K) P interphase nucleus with one R micronucleus. (L) P interphase nucleus with 6 R and one P micronuclei, all interconnected either to each other or to the main nucleus and with irregular shapes. (M) mixed R/P interphase gonocyte with a budding micronucleus with a mixed genome composition. Scale bars 10 µm.

Figure 5.

Chromosomal distribution and comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) analysis in SSC of adult hybrid males. (A) full diploid R metaphase plate (26 chromosomes) obtained from male no. 515. Big white arrows point to chromosomes cut into two insets: the upper inset includes two small R chromosomes with the pericentromeric signal of the perezi pointed by a small white arrow; the lower inset includes one big R chromosome with apparent double chromosomal breakage pointed by a small white arrow. (B) haploid R metaphase plate from male no. 509 with one small R chromosome displaying the pericentromeric signal of the perezi (shown by small arrow). (C) metaphase plate with 44 R chromosomes (18 big, 26 small) from male no. 546 with three small R chromosomes displaying pericentromeric signals of the perezi (indicated by small arrows). (D) metaphase plate from male no. 515 with a diploid set of R chromosomes and an additional small P chromosome, two small R chromosomes have pericentromeric perezi signals (small white arrow). (E) metaphase plate from male no. 515 with 24 R chromosomes (10 big, 14 small) and 12 P chromosomes (3 big, 9 small). (F) metaphase plate from male no. 545 with 26 R chromosomes, among which two R chromosomes have a perezi signal. Scale bars 10 µm.

Figure 5.

Chromosomal distribution and comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) analysis in SSC of adult hybrid males. (A) full diploid R metaphase plate (26 chromosomes) obtained from male no. 515. Big white arrows point to chromosomes cut into two insets: the upper inset includes two small R chromosomes with the pericentromeric signal of the perezi pointed by a small white arrow; the lower inset includes one big R chromosome with apparent double chromosomal breakage pointed by a small white arrow. (B) haploid R metaphase plate from male no. 509 with one small R chromosome displaying the pericentromeric signal of the perezi (shown by small arrow). (C) metaphase plate with 44 R chromosomes (18 big, 26 small) from male no. 546 with three small R chromosomes displaying pericentromeric signals of the perezi (indicated by small arrows). (D) metaphase plate from male no. 515 with a diploid set of R chromosomes and an additional small P chromosome, two small R chromosomes have pericentromeric perezi signals (small white arrow). (E) metaphase plate from male no. 515 with 24 R chromosomes (10 big, 14 small) and 12 P chromosomes (3 big, 9 small). (F) metaphase plate from male no. 545 with 26 R chromosomes, among which two R chromosomes have a perezi signal. Scale bars 10 µm.

Table 1.

In vitro crosses were conducted between P. grafi and P. perezi frogs to produce progeny for cytogenetic analysis of genome elimination and genotype assessment in backcrosses. Cross numbers are highlighted in bold; the values in the brackets describe the number of tadpoles sacrificed from each cross for this study. Numbers in italic represent P. grafi x P. grafi backcrosses.

Table 1.

In vitro crosses were conducted between P. grafi and P. perezi frogs to produce progeny for cytogenetic analysis of genome elimination and genotype assessment in backcrosses. Cross numbers are highlighted in bold; the values in the brackets describe the number of tadpoles sacrificed from each cross for this study. Numbers in italic represent P. grafi x P. grafi backcrosses.

| |

Male |

| Female |

ID |

546 |

510 |

513 |

509 |

548 |

515 |

545 |

| Genotype |

RP |

PP |

RR |

RP |

PP |

RP |

RP |

| ID |

Genotype |

Population |

Salagou |

Montpellier |

Montpellier |

Montpellier |

Salagou |

Montpellier |

Salagou |

| 521 |

PP |

Salagou |

|

|

12(9) |

|

|

|

|

| 532 |

PP |

Salagou |

6 (34) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 524 |

RP |

Salagou |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 503 |

RP |

Montpellier |

|

18(14)

|

|

16(5)

|

|

|

|

| 520 |

RP |

Salagou |

|

19(3) |

|

17(20)

|

|

|

|

| 525 |

RP |

Salagou |

|

|

|

|

|

27(4)

|

|

| 528 |

RP |

Salagou |

|

|

|

|

|

28(20)

|

|

| 531 |

RP |

Salagou |

|

|

|

|

24(9) |

29(20)

|

|

| 501 |

RP |

Montpellier |

|

|

|

|

|

26(20)

|

|

| 537 |

PP |

Salagou |

|

|

|

|

|

|

30(10)

|

Table 2.

Frequencies of micronuclei in interphase gonocytes were analyzed in chromosomal preparations across different crosses and Gosner stage categories. The genome type of each micronucleus was determined based on genomic probe signals following the CGH procedure. The numerical values in the table represent the number of micronuclei in the given range. Micronuclei were categorised into three groups: P – perezi genome, R – ridibundus genome, R/P mixed – genomes of both species.

Table 2.

Frequencies of micronuclei in interphase gonocytes were analyzed in chromosomal preparations across different crosses and Gosner stage categories. The genome type of each micronucleus was determined based on genomic probe signals following the CGH procedure. The numerical values in the table represent the number of micronuclei in the given range. Micronuclei were categorised into three groups: P – perezi genome, R – ridibundus genome, R/P mixed – genomes of both species.

| Cross no |

Genome type in micronuclei |

Gosner stage category |

Percentage of micronuclei [%] |

| 31 – 33 |

34 – 36 |

37 – 39 |

40 – 42 |

43 – 45 |

| Micronuclei count |

|

| 6 |

P |

15 |

30 |

17 |

33 |

37 |

81.2 |

| R |

1 |

10 |

6 |

8 |

4 |

16.5 |

| R/P mixed |

|

3 |

|

3 |

4 |

2.3 |

| 12 |

P |

6 |

|

11 |

|

|

62.5 |

| R |

4 |

|

4 |

|

|

25 |

| R/P mixed |

1 |

|

2 |

|

|

12.5 |

| 18 |

P |

|

1 |

2 |

8 |

8 |

62.5 |

| R |

|

1 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

25 |

| R/P mixed |

|

|

|

1 |

1 |

12.5 |

| 19 |

P |

|

|

|

15 |

|

73.3 |

| R |

|

|

|

6 |

1 |

26.7 |

| 24 |

P |

|

|

6 |

28 |

4 |

54.5 |

| R |

|

|

5 |

17 |

1 |

40.9 |

| R/P mixed |

|

|

|

1 |

|

4.5 |

| 30 |

P |

|

|

7 |

18 |

1 |

76.5 |

| R |

|

|

4 |

2 |

|

23.5 |