1. Introduction

Since the 1950s, agriculture has primarily aimed at intensifying production by increasing crop yields. This goal has largely been pursued through heavy use of mineral fertilizers and pesticides (Boincean, 2024), whose global consumption continues to rise (IFA, 2025; FAO, 2024, 2025). However, the overuse of these agrochemicals contributes to soil degradation, water contamination and greenhouse gas emissions (Silva et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2022; Bebber & Richards, 2022; Uddin & Kurosawa, 2011; Zhou et al., 2022; Lee & Jones-Lee, 2005; Menegat et al., 2022). For example, global consumption of mineral fertilizers (N, P, K) increased from 93.1 to 119.9 kg/ha of arable land between 2001 and 2022, while global pesticide use rose from 1.5 to 2.4 kg/ha over the same period (IFA, 2025; FAO, 2024, 2025).

Therefore, there is an urgent need to seek and apply natural-based alternatives that will not further burden arable soils environmentally, while supporting the development of beneficial microorganisms and maintaining or even increasing the yield and nutritional parameters of cultivated crops. This definition includes a group of substances collectively referred to as plant biostimulants. According to Regulation (EU) 2019/1009 of the European Parliament, the group of plant biostimulants is divided into microbial and non-microbial categories. Microbial products contain beneficial fungi, bacteria, or their combination. Non-microbial products include those based on 1) humic and fulvic acids, 2) protein hydrolysates and other N-containing compounds, 3) chitosan and other biopolymers, 4) inorganic substances (beneficial elements), and 5) seaweed and plant extracts, or combinations of these (du Jardin, 2015; European Parliament and Council (EU), 2019).

Rossini, Ruggeri, and Rossini (2025) found that a mixture of seaweed extracts and microorganisms applied with a reduced nitrogen fertilizer dose (100 kg/ha) achieved a wheat yield comparable to the standard dose (150 kg/ha), thus saving 33% of nitrogen. A similar trend was observed by Fall et al. (2023), who found that the combination of mycorrhizal inoculum with 50% doses of N, P, and K outperformed the 100% dose of N, P, and K in terms of growth and nutrient content in maize grown both in the greenhouse and in the field.

The group of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) consists of an obligate symbiotic class of fungi, the Glomeromycetes, which currently includes five orders: Archeosporales, Diversisporales, Entrophosphorales, Glomerales, and Paraglomerales (Spatafora et al., 2016; Schoch et al., 2020). These fungi encompass hundreds of species that colonize a diverse range of plants — from liverworts, ferns, and gymnosperms to angiosperms, with the exception of certain families such as Brassicaceae and Araceae (Gryndler, 2004; Smith & Read, 2008). In economically important crops, the presence of AMF is associated with increased nutrient and water uptake, often leading to higher yields, as well as positive changes in the plants’ primary and secondary metabolomes, which enhance their resistance to stress factors and improve the nutritional value of the crops (Rasouli et al., 2022; Keller-Pearson et al., 2020; Nedorost & Pokluda, 2012).

Landoltia punctata belongs to the family Araceae, subfamily Lemnoideae, and is an aquatic plant freely floating on or just below the water surface. Its body consists of a frond measuring 1–3 mm and 2–5 roots (Lee, Choi & Shiga, 2020; UF IFAS, 2025). Most studies on representatives of Lemnoideae focus on their ecological significance, especially wastewater bioremediation, where they effectively remove heavy metals, dyes, nanomaterials, microplastics, organic pollutants, pesticides, and pharmaceuticals (Xu et al., 2018; Neag, Malschi & Măicăneanu, 2018; Yue et al., 2018; Pop et al., 2021; Sikorski et al., 2019; Drobniewska et al., 2024). Some studies also examine the use of duckweed biomass as an alternative fertilizer for cereals (Ahmad et al., 1990; Hong et al., 2024; Pulido et al., 2021), tomatoes (Mahofa, Kapenzi & Masaka, 2013), and leafy vegetables (Baldi et al., 2025; Pratiwi, Aji & Sumbudi, 2022; Chikuvire, Muchaonyerwa & Zengeni, 2019). However, few studies have so far focused on the biostimulant effects of these plants, and all have concerned only Lemna minor. The aqueous extract of L. minor has been tested on maize under optimal (Del Buono et al., 2022) and stress conditions of increased NaCl (Priolo et al., 2024) and Cu (Miras-Moreno et al., 2022), on olive trees under optimal (Regni et al., 2021) and stress conditions of increased NaCl (Regni et al., 2024), and also on tomatoes (Priolo et al., 2024).

This study examined the effects of a well-established and commonly used group of biostimulants—arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi—alongside a newly emerging biostimulant derived from an aqueous extract of the aquatic plant L. punctata (clone no. 5562). According to available information, no previous study has tested the biostimulant effects of an extract from this plant. The main aims of this research were (i) to evaluate the effects of individual and combined applications of a mycorrhizal inoculum and an aqueous extract of L. punctata on lettuce biometric parameters, physiological status and biochemical composition, (ii) to assess mycorrhizal root colonization, and (iii) to conduct a metabolomic analysis of amino acids in the aqueous extract of L. punctata.

2. Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Growing Conditions

The experiment was conducted under indoor conditions at the Faculty of Agronomy, Mendel University, located at Zemědělská 1, 61300 Brno, Czech Republic. Seeds of leaf lettuce cultivar ‘Dubáček’ (MORAVOSEED CZ S.A., Mikulov, Czech Republic) were sown into a universal peat substrate (BAHAG AG, Mannheim, Germany) in plastic trays on March 3, 2025. Two of the four prepared variants were treated with mycorrhizal inoculum before sowing (see the chapter Biostimulant Preparation and Application).

The prepared trays were placed inside an indoor tent, type BudBox PRO Titan I+ HL 200 (BudBox™ Ltd., Harrogate, United Kingdom) and were cultivated under constant conditions until harvest. Throughout the entire experiment, a temperature regime of 23/20 °C day/night was maintained, the relative humidity was maintained in the range of 60–80 % using exhaust fans and humidifiers. Just above the edge of the trays, the photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) was measured, averaging 218.6 ± 27.27 µmol/m²/s with a red to blue light ratio of 20:1. The photoperiod was set to 18 hours of light and 6 hours of darkness. Irrigation was carried out daily—1.5 litres of settled tap water per tray. During the short-term cultivation of lettuce, no additional fertilization was required.

Experimental Design

The experiment included 4 variants, each represented by one plastic tray (87×124×43 cm). The trays were distributed among the variants according to a completely randomised design. Each variant contained 12 plants. The experiment included the following variants:

- (1)

C – control variant without any treatment;

- (2)

M – variant treated with mycorrhizal inoculum;

- (3)

M+L – variant treated with a combination of mycorrhizal inoculum and Landoltia punctata (clone no. 5562) extract;

- (4)

L – variant treated with L. punctata (clone no. 5562) extract.

Biostimulant Preparation and Application

Two types of biostimulant products were used in this experiment. The first was an AMF inoculum containing Claroideoglomus claroideum BEG96, Claroideoglomus etunicatum BEG92, Funneliformis geosporum BEG199, Funneliformis mosseae BEG95, and Rhizophagus irregularis BEG140. This mix contained 145 spores per g, and was obtained from the company Symbiom, Ltd., Sázava, Czech Republic. The other composition of this product, as declared by the manufacturer, is as follows: natural clay carriers, natural humates, seaweed extracts, ground minerals, and hydrogel particles. The mycorrhizal inoculum was applied in two variants (M and M+L) by adding 1 gram of the mycorrhizal inoculum into each sowing hole prior to seed sowing.

The second biostimulant product used in this experiment was an extract from duckweed, L. punctata clone no. 5562 (a pure clone purchased from the Friedrich Schiller Institute, Jena, Germany). The L. punctata clone was cultivated in an indoor growing system at the Faculty of Horticulture, Mendel University, located at Valtická 337, 69144 Lednice, Czech Republic. L. punctata was grown in a hydroponic nutrient solution Solinure GT 7 (ICL Group Ltd., Tel Aviv, Israel) at a concentration of 0.855 g of fertilizer per litre of tap water. The solution was acidified using 15 % HNO₃ to reach a pH close to neutral. Nutrient solution parameters at the time of Landoltia harvest were: temperature 20.1 °C, pH 7.36, EC 1590 µS, TDS 1.11 ppt, salinity 0.5 g/L, NH₄⁺-N 180.0 mg/L, NO₃⁻-N 86.5 mg/L, PO₄³⁻ 65.3 mg/L, K⁺ 43.1 mg/L. Ambient air temperature at harvest was 21.6 °C, with a relative humidity of 51.1 %. L. punctata was cultivated under a PPFD of 119.5 µmol/m²/s with a 16/8 light/dark photoperiod and a daily light integral (DLI) of 6.9. The extract was obtained following the methodology of Priolo et al. (2024). For the purpose of extract preparation, 50 g of fresh biomass was harvested, thoroughly washed with tap water, and drained for 5 minutes in a sieve. The biomass was then dried at 40 °C for 72 hours, and 2 g of the dry biomass was mixed with 400 mL of deionized water (pH = 7.0). The mixture was ground together in a mortar for 5 minutes and transferred into a vial placed on a shaker for 12 hours at room temperature and 150 rpm. The suspension was then filtered and brought up to a volume of 400 mL with deionized water, resulting in a 0.5 % duckweed aqueous extract (dry weight/water volume – wt/v). Lettuce leaves in variants M+L and L were treated with an extract from L. punctata at two time points – at the 5–7 true leaf stage (on March 21, 2025) and at the >10 true leaf stage (on March 28, 2025). In the first application, a dose of 2.5 mL per plant was used, and in the second, 5 mL per plant. The extract was freshly prepared for each treatment and applied using the FarmBot, version V1.7 (FarmBot, Inc., San Luis Obispo, United States), a robotic system with a standard spray watering nozzle. The dose per plant was adjusted by modifying the movement speed of the robotic arm. The remaining portion of the extract was used for metabolomic analyses.

Harvest of Plants and Sampling

Lettuces were harvested on April 7, 2025, for the purpose of evaluating biometric parameters. Each of these parameters (see below) was measured on all 12 plants per variant (n = 12). For subsequent analyses of biochemical compounds, composite samples were prepared from three plants per variant, resulting in four replicates for analytical measurements (n = 4).

Assessment of Photosynthetic, Biometric, and Biochemical Parameters of Lettuce

Prior to harvest, Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and Quantum Yield (Qy) values were measured at two time points during the experiment – on March 28, 2025 (before the second application of the Landoltia extract), and on April 4, 2025 – on all 12 plants per variant (n = 12). After harvest, various biometric parameters were evaluated. Above-ground biomass was measured as the weight of the edible part using a scale with 0.1 g accuracy. Leaf area was measured using the mobile application LeafScan (developed by Carlos Anderson), with a white reference square of 30 cm edge length as a background. Plant height and leaf rosette diameter were measured with a ruler accurate to millimeters. Additionally, the total number of leaves per plant was recorded. Root parameters were not evaluated because the complete root system could not be extracted from the peat substrate without damage. However, fragments of roots from all of the variants were used for subsequent microscopic observation.

Among the biochemical parameters, the following were determined: the percentage of dry matter in the edible aboveground part, content of vitamin C, chlorophyll a and b, carotenoids, total phenolic compounds, flavonoids, DPPH antioxidant capacity, and nitrates.

The dry matter content of the aboveground plant biomass was determined gravimetrically at 105 °C until a constant weight of the weighing dishes was reached (Zbíral, 2005).

Vitamin C was analysed using high-performance liquid chromatography (ECOM Ltd., Prague, Czech Republic) with an ARION® Polar C18 column (5 µm, 150 mm × 4.6 mm) and a mobile phase consisting of tetrabutylammonium hydroxide, oxalic acid, and water in a ratio of 10:20:70.

The determination of plant pigments (chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotenoids) was carried out according to the method of Holm (1954). According to this method, the pigments are extracted in acetone and subsequently measured spectrophotometrically at wavelengths of 662, 644, and 440 nm, in that order.

For the determination of total phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and DPPH antioxidant capacity, a methanolic extract of the samples was first prepared. Homogenized samples were extracted in 75% methanol for 24 hours, filtered, and then adjusted to a final volume of 50 mL with 75% methanol. Total phenolic content was determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent and a 7% sodium carbonate solution, with spectrophotometric measurement at 765 nm, according to Zloch, Čelakovský & Aujezdská (2004). The total content of flavonoids was determined using a 5% sodium nitrite solution, a 10% aluminium chloride solution, a 1 M sodium hydroxide solution, and a 1 mM catechin standard solution, with spectrophotometric measurement at 510 nm (Zloch, Čelakovský & Aujezdská, 2004). The total antioxidant capacity was determined using the DPPH spectrophotometric method, which is based on the scavenging of the DPPH⁺ radical cation (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl). Under standard conditions, this cation exhibits a purple colour, which turns yellowish upon reduction. For the reaction, a 100 μM solution of DPPH and a 0.5 mM solution of Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid) were used. The resulting absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 515 nm (Zloch, Čelakovský & Aujezdská, 2004).

Nitrate content in the samples was determined according to Zbíral (2005), using an ion-selective electrode (type 07–35) and a mercury sulphate reference electrode (type RME 121), both by Monokrystaly Ltd., Přepeře, Czech Republic.

Statistical Analyses

The data were processed and statistically analysed using Statistica 14 software package (DataBon Ltd., Prague, Czechia). Initially, extreme and outlying values were identified and removed using box plot analysis with a coefficient of 1.5. Subsequently, all monitored variables were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test at a significance level of α = 0.05. Simultaneously, the homogeneity of variances was assessed using Levene’s test at the same significance level (α = 0.05). For the data sets that met the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed. Statistically significant differences between groups were further evaluated using Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) post-hoc test (α = 0.05). In cases where the data did not meet the assumptions of normality or homogeneity, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA was applied. Statistically significant differences were subsequently identified through multiple comparisons of mean ranks across all groups (α = 0.05).

To investigate the relationships between measured traits, a correlation analysis was performed. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was calculated to determine the strength and direction of the linear relationship between pairs of variables, conducted separately for the biometric and the analytical datasets. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Plant Physiological Status

NDVI

Early in the plant’s development (March 28th), no significant differences in the NDVI were observed among the treatments. The Landoltia extract-only (L) treatment resulted in the highest mean NDVI of 0.604. The control group (C) and the combined treatment (M+L) showed similar mean values of 0.600 and 0.601, respectively. Interestingly, the mycorrhiza-only (M) treatment resulted in the lowest mean NDVI of 0.576.

On the second measurement date (April 4th), the differences in NDVI between the treatments were also statistically insignificant. The mean NDVI values slightly decreased, with the control measuring 0.464, the M 0.507, the M+L 0.527, and the L treatment 0.509. The overall decrease in NDVI values across all groups could reflect a change in leaf physiology as the plants entered a new growth phase. Between March 28 and April 4, the NDVI value in the control variant decreased by 0.136, while in the treated variants the decrease was noticeably lower, ranging from 0.095 to 0.069. This suggests that the application of biostimulants contributed to maintaining higher physiological activity and overall plant vitality compared to the untreated control.

Quantum Yield of Photosystem II

The quantum yield of photosystem II (Qy), which reflects the efficiency of the light-harvesting process, remained high and stable throughout the entire experiment. Mean Qy values consistently ranged from 0.81 to 0.83 across all treatment groups at both measurement dates. Critically, no statistically significant differences were found between the variants in the first date. In spite of significantly higher (0.82) result at M+L treatment in the second term, plants did not fundamentally alter or impair the core efficiency of the photosynthetic machinery. All plants, regardless of treatment, were photosynthetically healthy.

3.2. Biometric Parameters at Harvest

Above-ground Biomass

The above-ground fresh biomass was not significantly affected by the biostimulant applications. The control plants (C) produced a mean biomass of 214.3 g. The application of mycorrhiza alone (M) resulted in a modest insignificant increase to 223.4 g. Both Landoltia treatments (L and M+L) showed a slight but not-significant decrease in mean biomass compared to the other variants, with mean values of 199.3 g and 199.2 g, respectively.

Leaf Area, Plant Height and Diameter, Number of Leaves

According to statistical evaluation, the applied treatments had no significant effect on leaf area, which ranged from 956.6 cm² (in variant C) to 916.5 cm² (in variant L). Lettuce height was also not affected by the treatment variant. It ranged from 166.8 mm (in variant M+L) to 161.8 mm (in variant M). The largest average rosette diameter was recorded in the control variant at 270.9 mm, which was significantly higher than the mean diameter in variant L (248.3 mm). All variants had an average of 28.9 leaves, with no statistically significant differences between treatments.

3.3. Qualitative and Compositional Analysis

Dry Matter Content

The mean percentage of leaf dry matter was highest in the Landoltia variant (4.89 ± 0.32 %) and the mycorrhiza + Landoltia (M+L) variant (4.39 ± 0.81 %). The control and mycorrhiza variants showed lower mean values of 3.93 ± 0.26 % and 3.83 ± 0.11 %, respectively. The assumption of homogeneity of variance was violated for this parameter (p < 0.05); therefore, the Kruskal-Wallis test was employed. Multiple comparison of p-values test revealed no statistically significant differences in the dry matter of leaves among the four treatment groups.

Vitamin C Content

The concentration of vitamin C (ascorbic acid), a key nutritional quality indicator, was not significantly altered by the biostimulant treatments. The highest mean concentration of vitamin C was recorded in the M+L variant (55.7 ± 4.00 mg/kg), followed by the Landoltia (49.5 ± 10.51 mg/kg) and control (49.1 ± 2.41 mg/kg) variants. The mycorrhiza variant exhibited the lowest mean value (44.1 ± 7.30 mg/kg).

Photosynthetic Pigments

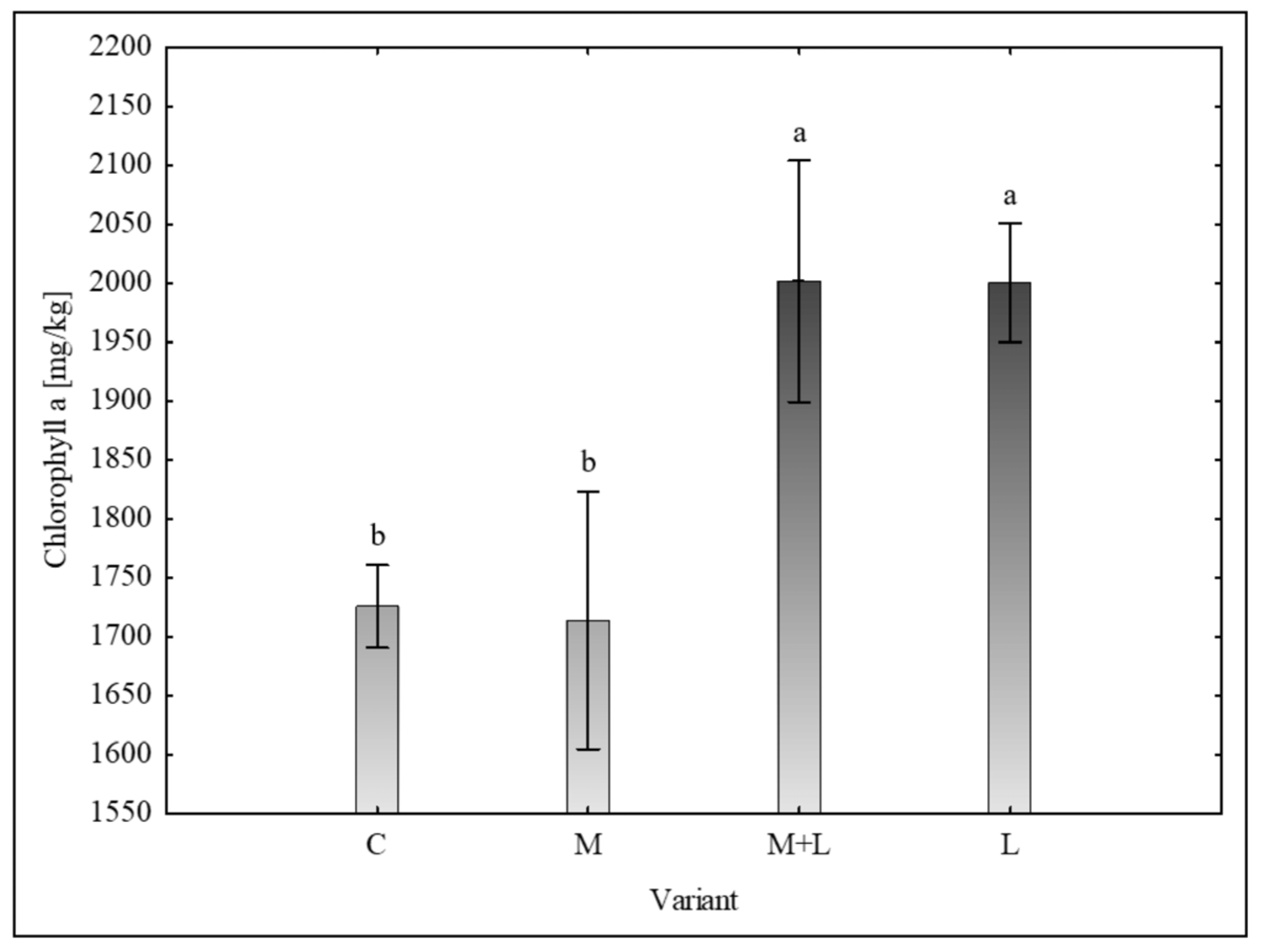

The concentrations of photosynthetic pigments were significantly influenced by the treatments. For chlorophyll a, the post-hoc test identified two distinct groups (

Figure 1). The M+L (2001.69 ± 204.54 mg/kg) and L (2000.48 ± 101.57 mg/kg) variants showed significantly higher concentrations compared to both the control (1725.66 ± 70.15 mg/kg) and mycorrhiza (1713.91 ± 218.33 mg/kg) variants.

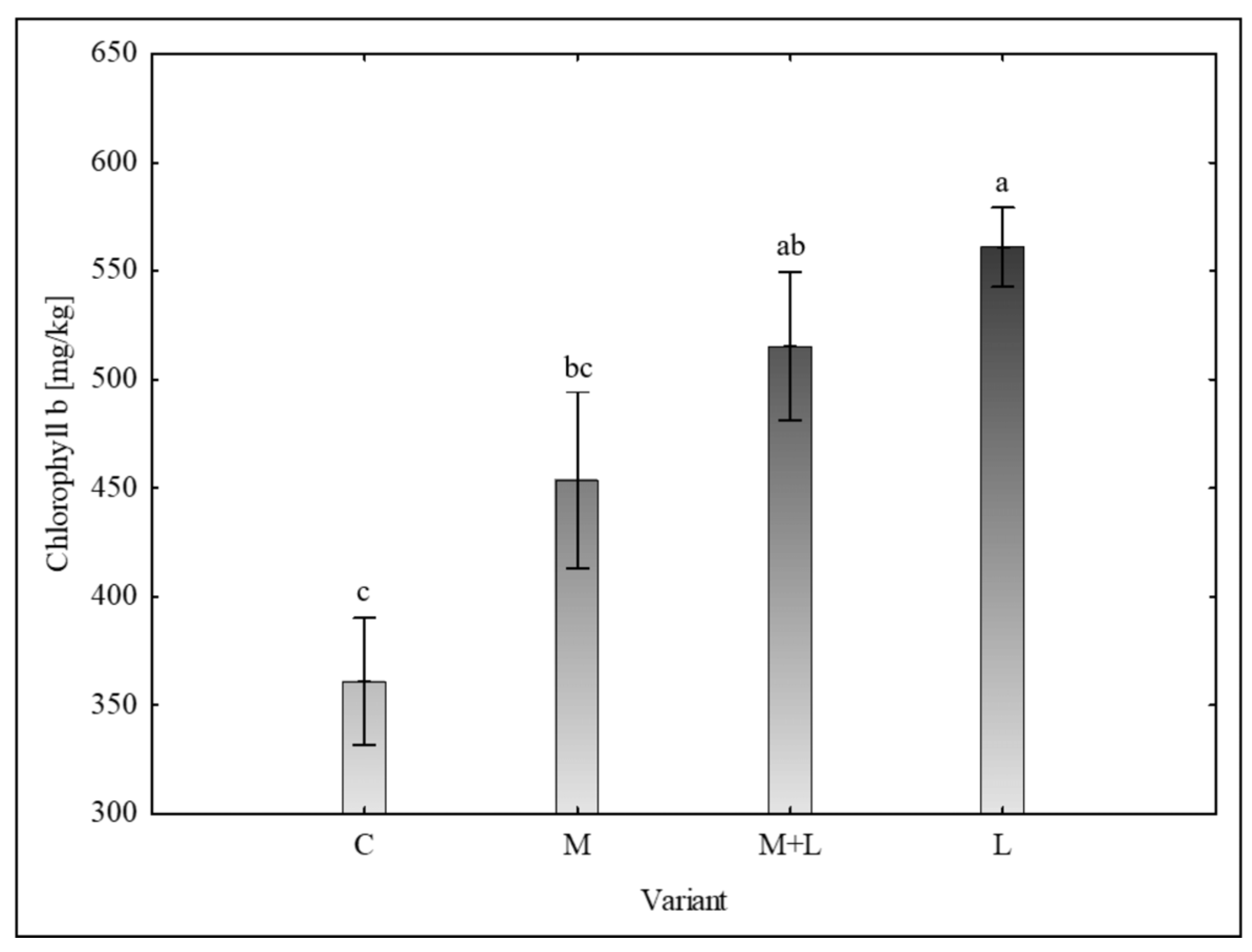

For chlorophyll b, the analysis revealed a gradient of effects across three overlapping homogenous groups (

Figure 2). The L variant (561.05 ± 36.24 mg/kg) and the M+L variant (515.51 ± 68.41 mg/kg) had significantly higher concentrations than the control variant (360.92 ± 58.39 mg/kg). The mycorrhiza variant (453.70 ± 81.20 mg/kg) did not differ significantly from either the control or the M+L and

Landoltia variants, holding an intermediate position.

Carotenoids

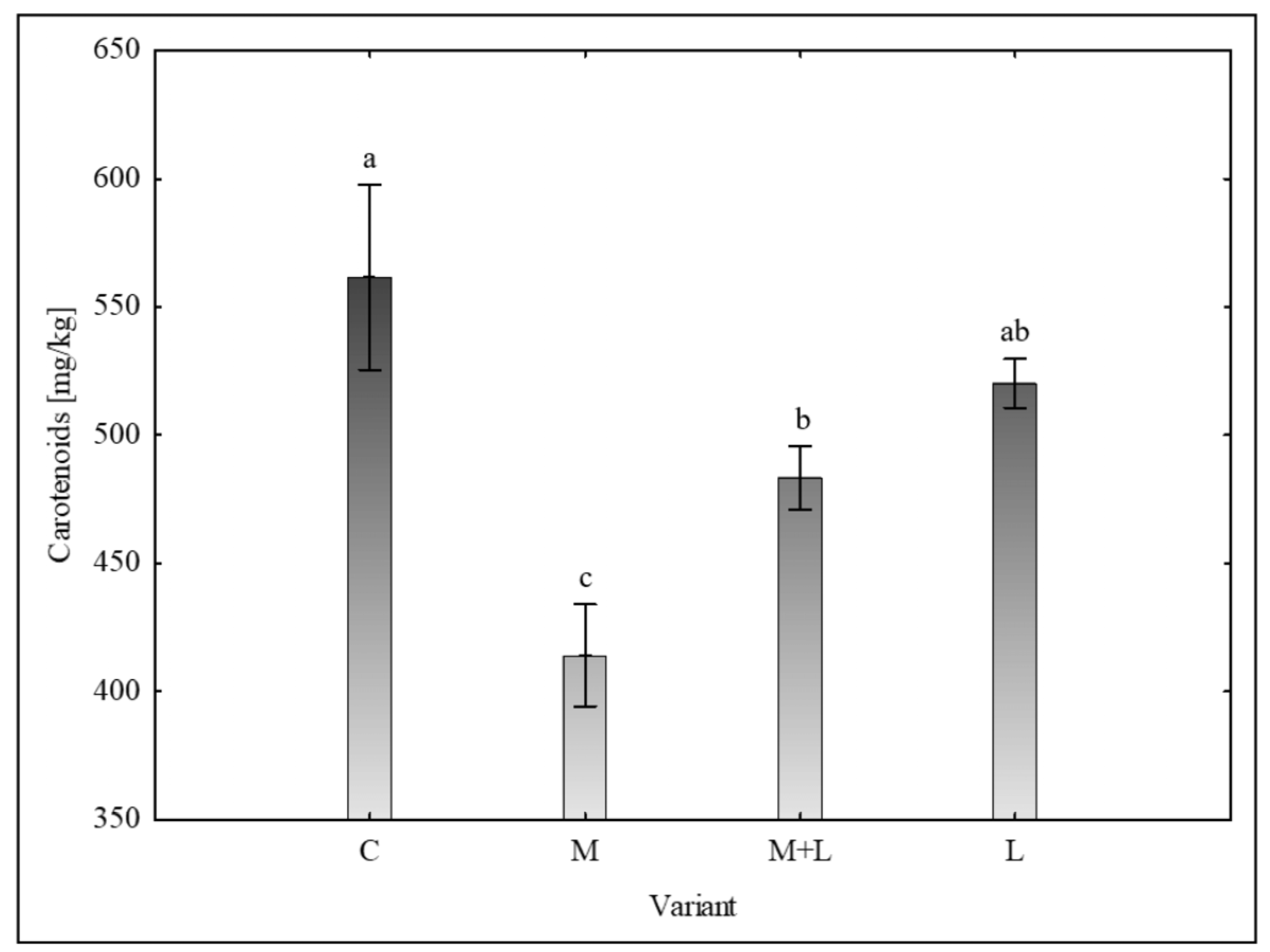

Analysis of carotenoid content (

Figure 3) revealed that the control group (561.67 ± 72.13 mg/kg) had a significantly higher concentration than the mycorrhiza variant (414.02 ± 39.63 mg/kg) and M+L variant (483.30 ± 24.40 mg/kg). The

Landoltia variant (520.27 ± 19.30 mg/kg) was not significantly different from the control or from M+L variant.

Phenolic and Flavonoid Content, Total Antioxidant Capacity

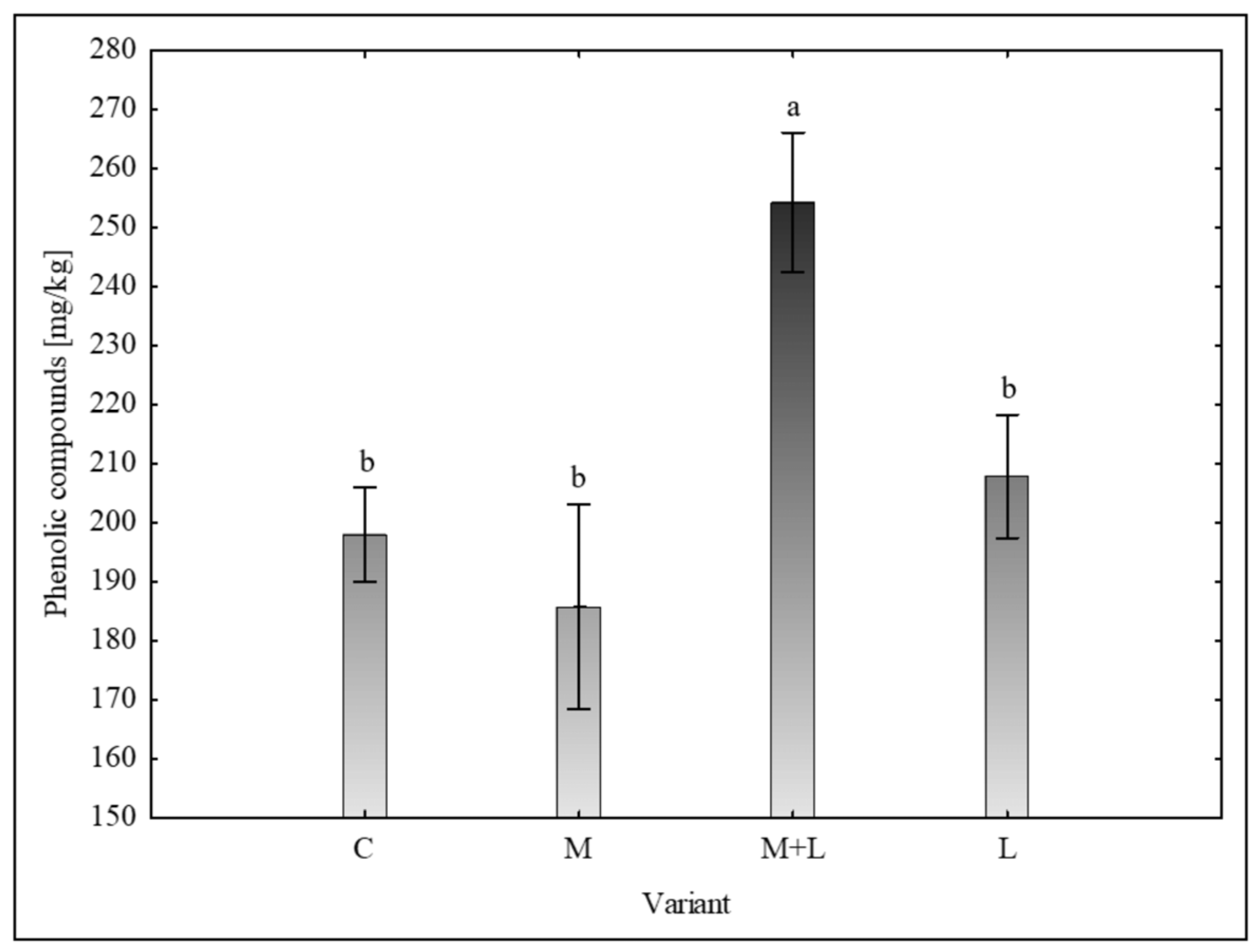

A statistically significant effect was observed on the accumulation of antioxidant compounds. The total amount of phenolic compounds (

Figure 4) in control plants was 198.00 ± 16.14 mg /kg. This was significantly elevated in M+L treatment (254.28 ± 23.63 mg /kg). The rest of treatments showed similar level to the control – M (185.77 ± 34.61 mg /kg), L (207.84 ± 20.84 mg /kg).

The highest mean flavonoid content was recorded in variant M (110.22 ± 24.00 mg/kg), followed by variant M+L (105.83 ± 4.73 mg/kg), while variants C and L reached only 97.67 ± 8.79 mg/kg and 90.21 ± 20.87 mg/kg, respectively. However, no statistically significant differences were observed among the data.

The total antioxidant capacity was not significantly different among the four treatment groups. Although there were slight variations in the mean values, the post-hoc tests confirmed that all variants belonged to a single homogenous group. The control group exhibited the highest mean antioxidant capacity, with a value of 126.68 ± 23.04 mg/kg, in contrast, variant M showed the lowest value of 113.14 ± 40.64 mg/kg.

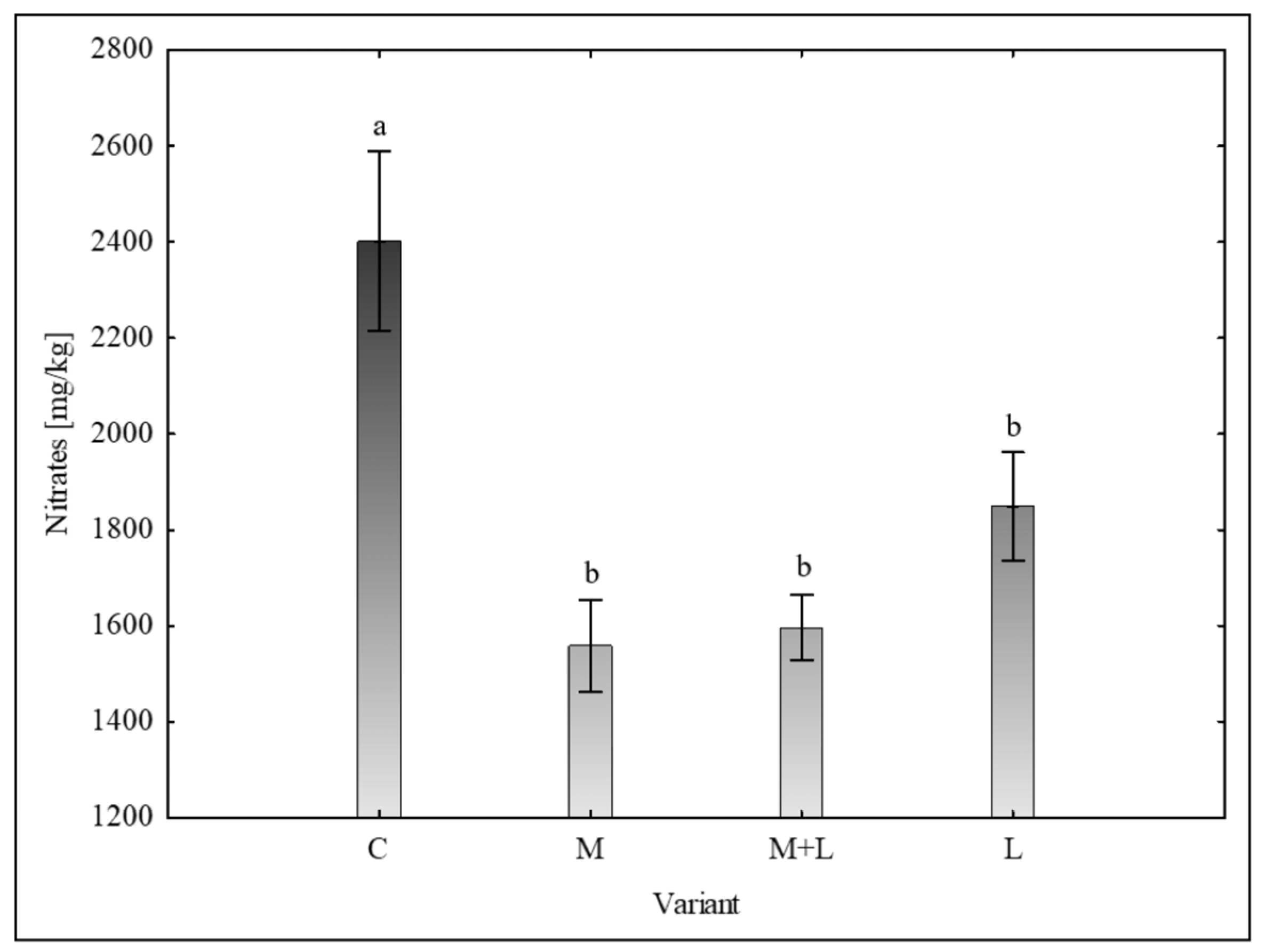

Nitrate Content

The concentration of nitrates in the leaves (

Figure 5), a critical parameter for food safety, was significantly affected by the treatments. The control group showed the highest mean nitrate level at 2402 ± 377 mg/kg. All biostimulant treatments significantly reduced this value, with the most effective being the M and M+L variant, which lowered the nitrate content to 1559 ± 192 and 1596 ± 137 mg/kg, respectively. Significant decrease was confirmed at L treatment alone, too.

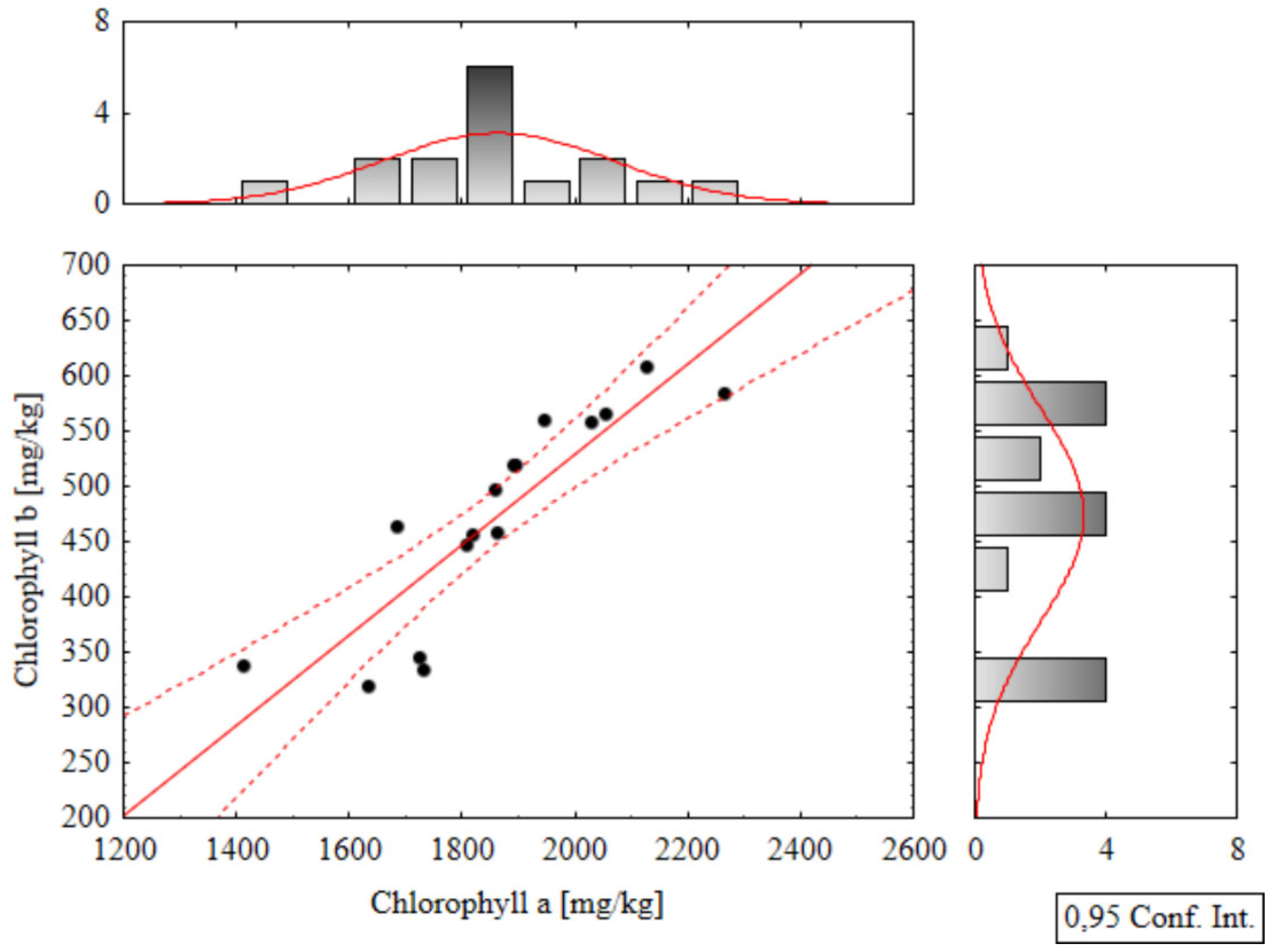

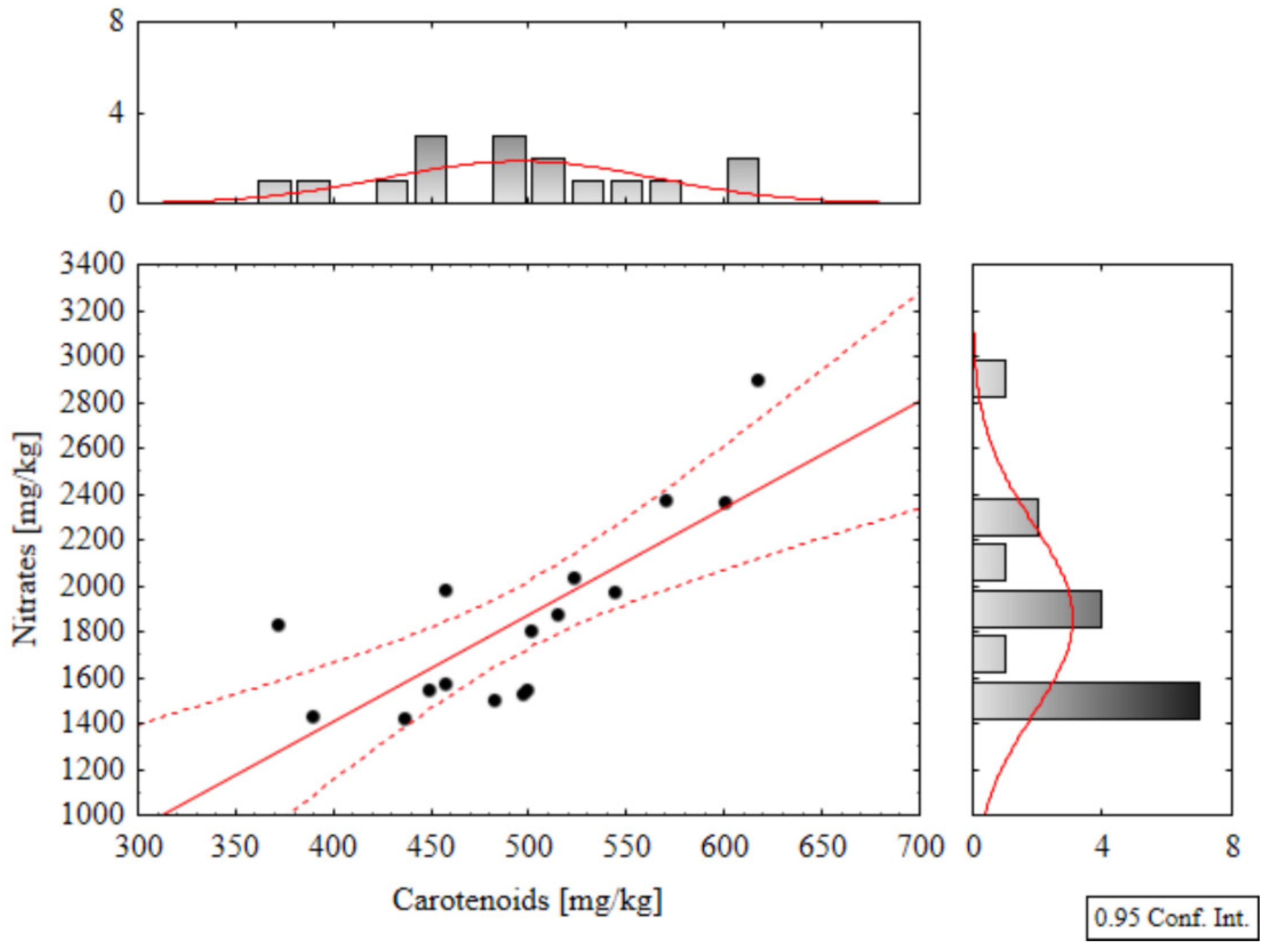

Correlation Analysis

Correlation analyses were performed within the groups of biometric and analytical parameters, and Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for all pairs of variables. Among the more significant relationships, a strong positive correlation was found between chlorophyll a and b parameters (

Figure 6), with a Pearson correlation coefficient of r = 0.875. Furthermore, a strong positive correlation was also observed between carotenoid and nitrate content parameters (

Figure 7), with r = 0.772.

3.4. Identified Amino Acids in the Aqueous Extract of Landoltia punctata

After performing a metabolomic analysis of a 0.5 % aqueous extract of

L. punctata (clone no. 5562), all proteinogenic amino acids (AAs) were detected, as well as two non-proteinogenic ones: gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and hydroxyproline. The concentrations of individual amino acids are summarized in

Table 2. The most abundant AAs were GABA and valine, with concentrations of 1548 and 1527 µg/mL, respectively, followed by phenylalanine (751 µg/mL) and tryptophan (551 µg/mL). Other highly represented AAs included alanine, leucine, arginine, aspartic acid, isoleucine, asparagine, glutamic acid, tyrosine, proline, and histidine, with concentrations ranging from 500 to 100 µg/mL. Glycine, threonine, glutamine and lysine were present only in the tens of micrograms per mL. Minor amounts of methionine, hydroxyproline, serine, and cysteine (in units or less than one µg/mL) were also detected in the duckweed extract.

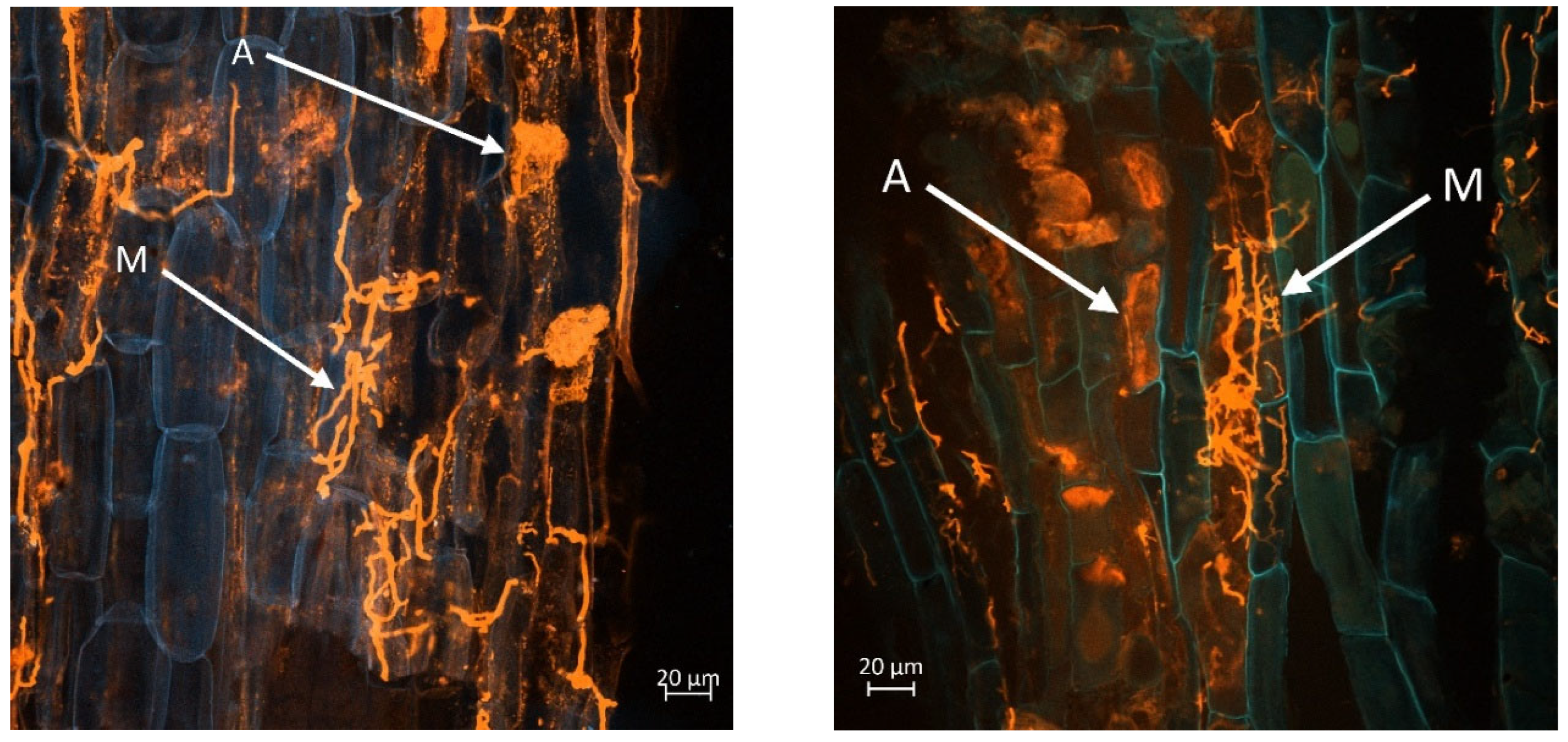

3.5. Mycorrhizal Colonisation

The inoculation with AMF was confirmed as successful and treatment-specific. Microscopic analysis of the root systems revealed a complete absence of mycorrhizal structures in both the control (C) and Landoltia extract-only (L) variants, confirming a zero-colonisation rate. In contrast, plants from the combined treatment group (M+L) treatment exhibited an evident mean colonisation of 42 %. An even higher colonisation intensity was noted in the mycorrhiza-only (M), which achieved a mean rate of 58 %. This successful establishment of the symbiosis is fundamental for interpreting the subsequent results.

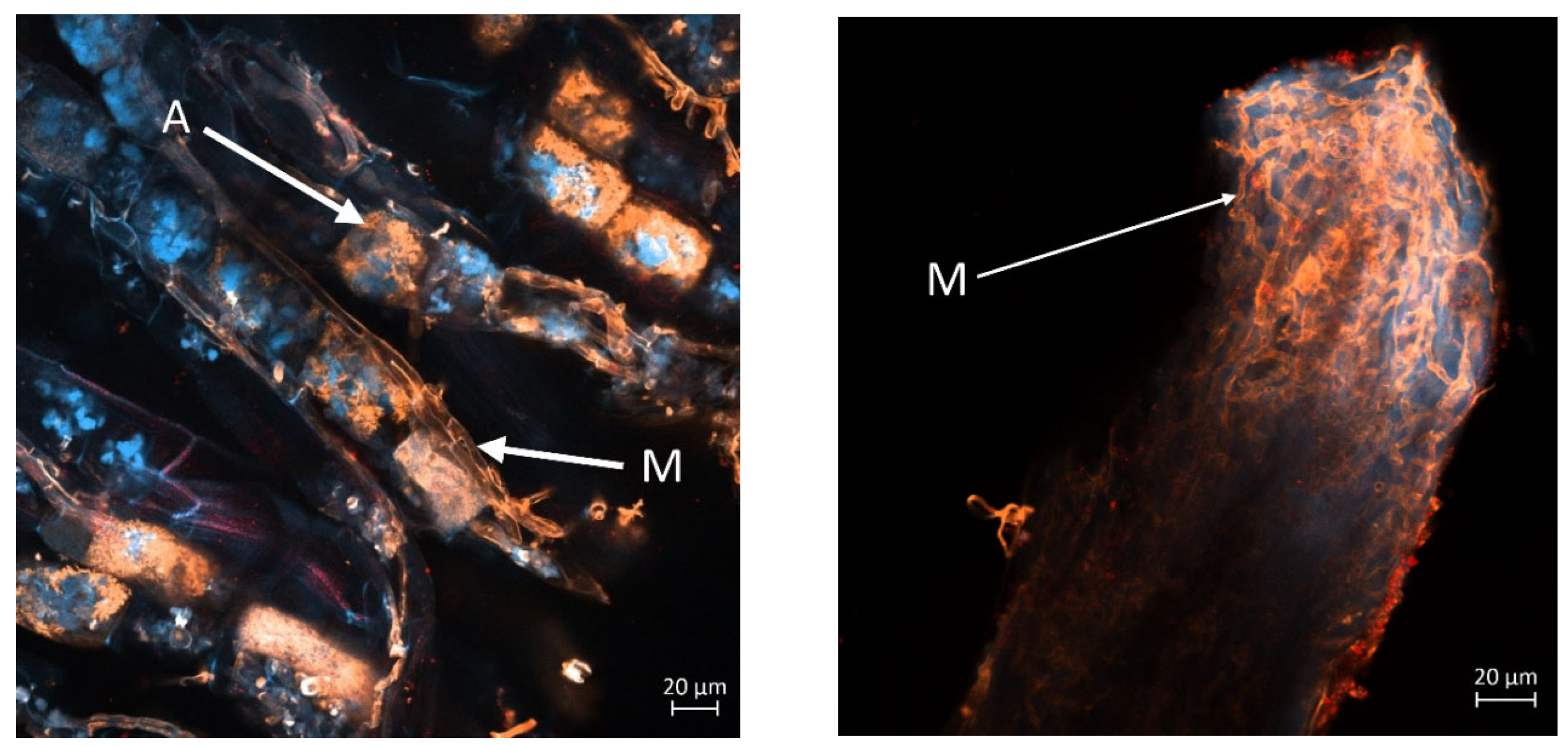

The

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 display a longitudinal section of a lettuce root cortex colonised by an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus. The plant cell walls are distinguished by their blue autofluorescence, whereas the fungal structures are visualized in orange. The arrow labelled A indicates a mature, finely branched arbuscule occupying a cortical cell. Arrow M points to a developing arbuscule or a hyphal coil. The thread-like orange structures are the intercellular hyphae that proliferate within the root apoplast before penetrating host cells to form the arbuscules.

Figure 8 (left and right) show mycorrhization in the M variant, while

Figure 9 (left and right) in M+L variant.

4. Discussion

The experiment tested four treatment variants (1. control, 2. treatment with a mixed mycorrhizal inoculum, 3. treatment with a 0.5 % aqueous extract of L. punctata, and 4. a combination of the two previous) in a growth trial with lettuce (Lactuca sativa L. cv. ‘Dubáček’). During plant growth and after harvest, photosynthetic, biometric, and qualitative parameters were evaluated.

Since this is a previously untested preparation, a metabolomic analysis of AAs in the aqueous extract of L. punctata was also conducted in order to link compositional information with potential stimulatory effects on lettuce plants. The results revealed particularly high levels of GABA, valine, phenylalanine, and tryptophan, including a complete set of proteinogenic amino acids. These data complement the findings of Regni et al. (2021) and Buono et al. (2022), who reported a metabolomic profile of Lemna minor extract containing, in addition to AAs, phytohormones, low-molecular-weight phenolic compounds (phenylpropanoids and their glycosides, flavonoids, and simple phenolic acids), glucosinolates, alkaloids, isoprenoids, tetraterpenes, and chlorophylls.

Furthermore, mycorrhizal symbiosis establishment was microscopically examined to confirm its potential influence on lettuce culture. Both mycorrhizal treatments showed average standard colonization rates of 58 % (M) and 42 % (M+L). AMF are known to be host-specific, meaning that different AMF species interact with different host plants at varying colonization levels, ranging from just a few percent to nearly 100 % (Carrenho et al., 2007). Microscopic assessment of AMF colonization confirmed that the inoculum was well suited for this plant species and can therefore be associated with the observed effects.

Photosynthetic Parameters

Present study did not demonstrate significant effects of individual treatments on photosynthetic parameters. However, the substantially lower decline in NDVI values between the monitored dates across all treated variants suggests prolonged vegetation vitality and delayed chlorophyll degradation. A statistically significant increase in the quantum yield of photosystem II was observed only in the combined treatment with mycorrhiza and L. punctata extract (M+L) at the second measurement, whereas the extract alone did not show this effect.

Priolo et al. (2024) reported a stronger response in tomato, where the effective quantum yield of photosystem II (ΦII, Phi2) was highest with 0.5 % and 1 % aqueous extracts of L. minor, although no differences were observed in the maximum quantum yield (Fv/Fm). Our results therefore suggest that the effect of L. punctata extract may be more evident in combination with mycorrhizal inoculation, though it cannot be excluded that a significant effect on ΦII could also appear under single extract application, similar to the findings of Priolo et al. (2024) with L. minor.

Regni et al. (2021) studied the effects of L. minor aqueous extract on olive trees, where 0.5 % and 1 % concentrations significantly increased net photosynthesis (Pn), stomatal conductance (gs), and substomatal CO₂ concentration compared to the untreated control. A positive influence on photosystem II efficiency was also reported by Asadi et al. (2022) after combined application of AMF (specifically Funneliformis mosseae, also included in our inoculum) with foliar application of 3 g/L seaweed extract. Moreover, Regni et al. (2024) observed improved photosynthetic activity in olive trees treated with L. minor extract under increased salinity, similar to the findings of Miras-Moreno et al. (2022) in maize exposed to excessive Cu concentrations.

Although current evidence supports the positive impact of duckweed extracts on the photosynthetic apparatus of plants, the specific effects of L. punctata extract alone and of mycorrhizal inoculation still require further clarification. Our results indicate that the observed increase in the quantum yield of photosystem II may result from their synergistic action as well as from the potential individual contributions of both treatments.

Biometric Parameters

A number of studies have confirmed the positive effects of mycorrhizal inoculation on the growth and yield parameters of lettuce. For example, Zrig et al. (2025) reported a 38.8 % increase in lettuce yield following inoculation with F. mosseae compared to the control. Similarly, Han et al. (2023) observed a 30 % increase in lettuce plant height in variants inoculated with AMF (F. mosseae) compared to the control. In another experiment led by Rasouli et al. (2022), co-application of AMF (F. mosseae) with foliar application of seaweed extract (3 g/L) increased the number of leaves by 44 %, the average head diameter 3.6-fold, and head yield 3.4-fold compared to the control.

Although present study did not confirm statistically significant differences in biometric parameters, a similar trend was observed for above-ground biomass. The mean value in the M variant was slightly higher (223.4 g) compared to the untreated control (214.3 g). Previous studies with aqueous extracts of L. minor have also reported positive effects on biometric parameters such as fresh shoot weight, shoot dry matter, plant height, leaf area, and number of leaves, with the optimal concentration being 0.5 % (the same concentration was used in this study) (Buono et al., 2022; Regni et al., 2021; Priolo et al., 2024).

Regni et al. (2024) further showed that salt stress induced by NaCl reduced several growth parameters in olive trees (number of leaves, lateral shoots, and plant height). However, after treatment with L. minor extract, these parameters recovered to levels comparable with unstressed controls. A similar trend was observed by Miras-Moreno et al. (2022), where excess Cu caused a decline in growth parameters, but treatment with L. minor extract restored or even exceeded control values for plant height, root length, and fresh shoot weight.

The positive influence of duckweed extract on vegetative growth reported by these authors is likely related to a combination of factors: increased chlorophyll content (see below), enhanced photosynthesis, uptake of organic N in the form of AAs via foliar nutrition (see amino acid profile results), and thus accelerated protein biosynthesis.

Photosynthetic Pigments and Carotenoids

The study showed that variants treated with the Landoltia extract (L and M+L) had significantly higher concentrations of chlorophyll a than both the control and the mycorrhizal variant, while chlorophyll b was significantly higher only compared to the control. This suggests that compounds present in the extract may either promote chlorophyll synthesis or slow down its degradation. These findings are consistent with those of Priolo et al. (2024) and Regni et al. (2021).

In contrast, mycorrhizal application alone (M) in our study did not increase chlorophyll levels compared to the control, which contradicts the results of Cela et al. (2022), who reported a 35 % increase in chlorophyll in lettuce treated with F. mosseae at 35 days after treatment and a 50 % increase at 53 days compared to the untreated control.

In our study, the sum of chlorophyll a + b was highest in the L variant (2561.53 mg/kg), followed by M+L (2517.2 mg/kg), M (2167.61 mg/kg), and the lowest in the control C (2086.58 mg/kg). An opposite trend was observed for carotenoids, which may indicate more intensive photosynthetic processes accompanied by reduced stress and thus a lower need for protective carotenoid pigments. In contrast, Priolo et al. (2024) found that treatment of NaCl-stressed maize plants with L. minor extract had no effect on carotenoid content.

Qualitative Parameters

Vitamin C content was not significantly affected by the treatments. Although a slight trend towards higher values was observed in the combined M+L treatment and in the L variant alone, the data did not follow a normal (Gaussian) distribution, and the variability within groups was too high to establish a statistically significant effect.

The treatments had different impacts on the antioxidant profile of lettuce. A clear synergistic effect was observed in the combined M+L variant, which resulted in a significantly higher content of total phenolic compounds compared to all other treatments. A similar synergistic effect was also reported by Rasouli et al. (2022) with AMF application in combination with 3 g/L of seaweed extract. In contrast, no statistically significant differences were found in flavonoid content or in total antioxidant capacity as measured by the DPPH assay.

From a food safety perspective, one of the most valuable outcomes of this study is the significant reduction of nitrate concentrations in all biostimulant-treated variants. The M and M+L treatments were the most effective, reducing nitrate levels by 35 % and 34 %, respectively, compared to the control. This result is consistent with the known ability of AMF to improve nitrogen use efficiency in host plants (Aini, Yamika & Ulum, 2019). Nitrate reduction can generally be interpreted as their more efficient assimilation into ammonia and subsequently into organic nitrogen. This theory is supported by the findings of Priolo et al. (2024), who reported a significant increase in protein content in NaCl-stressed maize treated with L. minor extract, reaching levels comparable to unstressed control plants. Thus, future testing of this potentially biostimulant preparation from duckweed should also focus on total protein content.

Importantly, all measured values were well below the maximum permissible limits set by the European Commission (Regulation 2023/915), confirming the high quality and safety of the produce.

5. Conclusions

The application of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and an aqueous extract of Landoltia punctata did not significantly change the fresh biomass of lettuce under the experimental conditions. However, the treatments induced significant and beneficial changes in the plant’s biochemical profile. Notably, the Landoltia extract, applied both individually and in combination with mycorrhiza, led to a substantial increase in chlorophyll a and b concentrations. A clear synergistic effect was observed in the combined treatment (M+L), which was the only variant to significantly elevate the content of total phenolic compounds. Crucially, all biostimulant applications resulted in a significant reduction of nitrate levels in the leaves, a key parameter for food safety. These findings demonstrate that whilst these biostimulants may not serve as primary growth promoters in non-stressed, short-term cultivation, they are highly effective in modulating plant metabolism to enhance nutritional quality. The use of L. punctata extract, therefore, represents a promising strategy for producing lettuce with improved phytochemical content and greater consumer value.

References

- Ahmad, Z., Hossain, N., Hussain, S., & Khan, A. H. (1990). Effect of duckweed (Lemna minor) as complement to fertilizer nitrogen on the growth and yield of rice. International Journal of Tropical Agriculture, 8, pp. 72-79.

- Aini, N., Yamika, W. S., & Ulum, B. (2019). Effect of nutrient concentration, PGPR and AMF on plant growth, yield and nutrient uptake of hydroponic lettuce. International Journal of Agriculture and Biology. [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, C., & Cuenca, G. (12. 2005). Arbuscular mycorrhizas in coastal sand dunes of the Paraguaná Peninsula, Venezuela. Mycorrhiza. [CrossRef]

- Asadi, M., Rasouli, F., Amini, T., Hassanpouraghdam, M. B., Souri, S., Skrovankova, S., . . . Ercisli, S. (2022). Improvement of Photosynthetic Pigment Characteristics, Mineral Content, and Antioxidant Activity of Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) by Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus and Seaweed Extract Foliar Application. Agronomy. [CrossRef]

- Baldi, A., Verdi, L., Piacenti, L., & Lenzi, A. (2025). From Waste to Resource: Use of Lemna minor L. as Unconventional Fertilizer for Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Horticulturae. [CrossRef]

- Bebber, D. P., & Richards, V. (2022). A meta-analysis of the effect of organic and mineral fertilizers on soil microbial diversity. Applied Soil Ecology. [CrossRef]

- Boincean, B. (2024, 3. 13.). From green revolution to green agriculture: horizons to rethinking and transforming agrifood systems for people and the planet. Retrieved from FAO: Regional Technical Platform on Green Agriculture : https://www.fao.org/platforms/green-agriculture/news/news-detail/from-green-revolution-to-green-agriculture--horizons-to-rethinking-and-transforming-agrifood-systems-for-people-and-the-planet/en.

- Buono, D. D., Bartucca, M. L., Ballerini, E., Senizza, B., Lucini, L., & Trevisan, M. (2022). Physiological and Biochemical Effects of an Aqueous Extract of Lemna minor L. as a Potential Biostimulant for Maize. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation. [CrossRef]

- Carrenho, R., Trufem, S. F., Bononi, V. L., & Silva, E. S. (2007). The effect of different soil properties on arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization of peanuts, sorghum and maize. Acta Botanica Brasilica. [CrossRef]

- Cela, F., Avio, L., Giordani, T., Vangelisti, A., Cavallini, A., Turrini, A., . . . Incrocci, L. (2022). Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Increase Nutritional Quality of Soilless Grown Lettuce while Overcoming Low Phosphorus Supply. Foods. [CrossRef]

- Drobniewska, A., Giebułtowicz, J., Wawryniuk, M., Kierczak, P., & Nałęcz-Jawecki, G. (2024). Toxicity and bioaccumulation of selected antidepressants in Lemna minor (L.). Ecohydrology & Hydrobiology. [CrossRef]

- Evropský parlament a Rada (EU). (2019). Regulation (EU) 2019/1009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 laying down rules on the making available on the market of EU fertilising products. Retrieved from EUR-Lex: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/1009/oj/eng.

- Fall, A. F., Nakabonge, G., Ssekandi, J., Founoune-Mboup, H., Badji, A., Ndiaye, A., . . . Ekwangu, J. (2023). Combined Effects of Indigenous Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMF) and NPK Fertilizer on Growth and Yields of Maize and Soil Nutrient Availability. Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- FAO. (2024). Land statistics 2001–2022 Global, regional and country trends. Rome: FAO. [CrossRef]

- FAO. (2025). Pesticides Use. Načteno z Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/RP/visualize.

- Gryndler, M. (2004). Mykorhizní symbióza. Praha: Academia. ISBN: 80-200-1240-0.

- Han, Z., Zhang, Z., Li, Y., Wang, B., Xiao, Q., Li, Z., . . . Chen, J. (2023). Effect of Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) inoculation on endophytic bacteria of lettuce. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology. [CrossRef]

- Holm, G. (1954). Chlorophyll mutations in barley. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, stránky 457-471.

- Hong, C., Wang, Z., Wang, Y., Zong, X., Qiang, X., Li, Q., . . . Guo, X. (2024). Response of duckweed to different irrigation modes under different fertilizer types and rice varieties: Unlocking the potential of duckweed (Lemna minor L.) in rice cultivation as “fertilizer capacitors”. Agricultural Water Management. [CrossRef]

- Chikuvire, T. J., Muchaonyerwa, P., & Zengeni, R. (2019). Improvement of nitrogen uptake and dry matter content of Swiss chard by pre-incubation of duckweeds in soil. International Journal of Recycling of Organic Waste in Agriculture. [CrossRef]

- IFA. (2025). Fertilizer Consumption - Historical Trends by Country or Region. Retrieved from International Fertilizer Association: https://www.ifastat.org/databases/graph/1_1.

- Jardin, P. d. (2015). Plant biostimulants: Definition, concept, main categories and regulation. Scientia Horticulturae. [CrossRef]

- Keller-Pearson, M., Liu, Y., Peterson, A., Pederson, K., Willems, L., Ané, J.-M., & Silva, E. M. (2020). Inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi has a more significant positive impact on the growth of open-pollinated heirloom varieties of carrots than on hybrid cultivars under organic management conditions. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. [CrossRef]

- Lee, G. F., & Jones-Lee, A. (2005). Eutrophication (Excessive Fertilization). In J. H. Lehr, & J. Keeley, Water Encyclopedia. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y., Choi, H. J., & Shiga, T. (2020). Taxonomic identity of Landoltia punctata (Araceae, Lemnoideae) in Korea. Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity. [CrossRef]

- Mahofa, R., Kapenzi, A., & Masaka, J. (2013). The effects of different types of duckweed manure on height and yield of floridade tomatoes. Midlands State University Journal of Science, Agriculture and Technology.

- Menegat, S., Ledo, A., & Tirado, R. (2022). Greenhouse gas emissions from global production and use of nitrogen synthetic fertilisers in agriculture. Scientific Reports. [CrossRef]

- Miras-Moreno, B., Senizza, B., Regni, L., Tolisano, C., Proietti, P., Trevisan, M., . . . Buono, D. D. (2022). Biochemical Insights into the Ability of Lemna minor L. Extract to Counteract Copper Toxicity in Maize. Plants. [CrossRef]

- Neag, E., Malschi, D., & Măicăneanu, A. (2018). Isotherm and kinetic modelling of Toluidine Blue (TB) removal from aqueous solution using Lemna minor. International Journal of Phytoremediation. [CrossRef]

- Nedorost, L., & Pokluda, R. (2012). Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on tomato yield and nutrient uptake under different fertilization levels. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis. [CrossRef]

- Pop, C.-E., Draga, S., Măciucă, R., Niță, R., Crăciun, N., & Wolff, R. (2021). Bisphenol A Effects in Aqueous Environment on Lemna minor. Processes. [CrossRef]

- Pratiwi, A., Aji, O. R., & Sumbudi, M. (2022). Growth Response and Biochemistry of Red Spinach (Amaranthus tricolor L.) with the Application of Liquid Organic Fertilizer Lemna sp. Journal of Biotechnology and Natural Science. [CrossRef]

- Priolo, D., Tolisano, C., Ballerini, E., Brienza, M., & Buono, D. D. (2024). Stimulatory Effect of an Extract of Lemna minor L. in Protecting Maize from Salinity: A Multifaceted Biostimulant for Modulating Physiology, Red. Balance, and Nutrient Uptake. Agriculture. [CrossRef]

- Priolo, D., Tolisano, C., Brienza, M., & Buono, D. D. (23.. 5. 2024). Insight into the Biostimulant Effect of an Aqueous Duckweed Extract on Tomato Plants. Agriculture. [CrossRef]

- Pulido, C. R., Caballero, J., Bruns, M. A., & Brennan, R. A. (2021). Recovery of waste nutrients by duckweed for reuse in sustainable agriculture: Second-year results of a field pilot study with sorghum. Ecological Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, F., Amini, T., Asadi, M., Hassanpouraghdam, M. B., Aazami, M. A., Ercisli, S., . . . Mlcek, J. (2022). Growth and Antioxidant Responses of Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) to Arbuscular Mycorrhiza Inoculation and Seaweed Extract Foliar Application. Agronomy. [CrossRef]

- Regni, L., Buono, D. D., Miras-Moreno, B., Senizza, B., Lucini, L., Trevisan, M., . . . Proietti, P. (2021). Biostimulant Effects of an Aqueous Extract of Duckweed (Lemna minor L.) on Physiological and Biochemical Traits in the Olive Tree. Agriculture. [CrossRef]

- Regni, L., Tolisano, C., Buono, D. D., Priolo, D., & Proietti, P. (2024). Role of an Aqueous Extract of Duckweed (Lemna minor L.) in Increasing Salt Tolerance in Olea europaea L. Agriculture. [CrossRef]

- Rossini, A., Ruggeri, R., & Rossini, F. (2025). Combining nitrogen fertilization and biostimulant application in durum wheat: Effects on morphophysiological traits, grain production, and quality. Italian Journal of Agronomy. [CrossRef]

- Schoch, C. L. (2020). Glomeromycetes. Retrieved from NCBI Taxonomy: a comprehensive update on curation, resources and tools: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?mode=Tree&id=214506&lvl=3&lin=f&keep=1&srchmode=1&unlock.

- Sikorski, Ł., Baciak, M., Bęś, A., & Adomas, B. (2019). The effects of glyphosate-based herbicide formulations on Lemna minor, a non-target species. Aquatic Toxicology. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J., Duarte, S. N., Silva, D. D., & Miranda, N. O. (2019). Reclamation of salinized soils due to excess of fertilizers: evaluation of leaching systems and equations. Dyna. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S. E., & Read, D. (2008). Mycorrhizal Symbiosis (Vol. 3.). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Spatafora, J. W., Chang, Y., Benny, G. L., Lazarus, K., Smith, M. E., Berbee, M. L., . . . Stajich, J. E. (2016). A phylum-level phylogenetic classification of zygomycete fungi based on genome-scale data. Mycologia. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M. S., & Kurosawa, K. (2011). Effect of chemical nitrogen fertilizer application on the release of arsenic from sediment to groundwater in Bangladesh. Procedia Environmental Sciences. [CrossRef]

- UF IFAS. (2025). Landoltia punctata, dotted duckweed. Retrieved from University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants: https://plant-directory.ifas.ufl.edu/plant-directory/landoltia-punctata/.

- Vierheilig, H., Schweiger, P., & Brundrett, M. C. (12. 2005). An overview of methods for the detection and observation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in roots+. Physiologia Plantarum. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H., Yu, C., Xia, X., Li, M., Li, H., Wang, Y., . . . Zhou, G. (2018). Comparative transcriptome analysis of duckweed (Landoltia punctata) in response to cadmium provides insights into molecular mechanisms underlying hyperaccumulation. Chemosphere. [CrossRef]

- Yue, L., Zhao, J., Yu, X., Lv, K., Wang, Z., & Xing, B. (2018). Interaction of CuO nanoparticles with duckweed (Lemna minor. L): Uptake, distribution and ROS production sites. Environmental Pollution. [CrossRef]

- Zbíral, J. (2005). Analýza rostlinného materiálu: Jednotné pracovní postupy. Ústřední kontrolní a zkušební ústav zemědělský.

- Zhang, Y., Ye, C., Su, Y., Peng, W., Lu, R., Liu, Y., . . . Zhu, S. (2022). Soil Acidification caused by excessive application of nitrogen fertilizer aggravates soil-borne diseases: Evidence from literature review and field trials. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W., Lv, H., Chen, F., Wang, Q., Li, J., Chen, Q., & Liang, B. (2022). Optimizing nitrogen management reduces mineral nitrogen leaching loss mainly by decreasing water leakage in vegetable fields under plastic-shed greenhouse. Environmental Pollution. [CrossRef]

- Zloch, Z., Čelakovský, J., & Aujezdská, A. (2004). Stanovení obsahu polyfenolů a celkové antioxidační kapacity v potravinách rostlinného původu.

- Zrig, A., Alsherif, E. A., Aloufi, A. S., Korany, S. M., Selim, S., Almuhayawi, M. S., . . . Bouqellah, N. A. (2025). The biomass and health-enhancing qualities of lettuce are amplified through the inoculation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. BMC Plant Biol. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).