1. Introduction

Dalbergia latifolia Roxb., commonly known as Indian rosewood, is a highly valued timber species from the Fabaceae family. Despite its commercial significance, it is sparsely distributed across tropical and subtropical habitats [

1]. In addition to its demand for timber,

D. latifolia is known for its medicinal properties, particularly its tannin content, which is used in the treatment of leprosy and parasitic infections [

2]. Classified as ‘Vulnerable’ by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and listed under Appendix II of CITES, the species faces a decline in population due to factors such as overharvesting, illegal trade, habitat destruction, and environmental degradation [

1,

3]. To ensure its survival, conservation efforts and artificial regeneration within its native habitats are essential. Large-scale cultivation and afforestation initiatives will also play a key role in sustaining

D. latifolia [

4].

Arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi, beneficial soil microbes that form symbiotic relationships with plants, have shown potential in enhancing nutrient uptake, particularly phosphorus (P), zinc (Zn), and copper (Cu). These fungi also improve plant resilience to biotic and abiotic stresses [

5]. In addition to their role in nutrient uptake, AM fungi contribute to soil structure, nutrient cycling, and ecosystem sustainability [

6]. By optimizing water and phosphorus absorption, AM fungi promote plant growth [

7], and their use as biofertilizers is becoming increasingly relevant for enhancing plant health and productivity.

This study investigates the impact of AM fungi on the growth performance of

Dalbergia latifolia and assesses their potential in supporting sustainable cultivation practices. Previous research has documented the positive effects of AM fungi on plant growth, with studies highlighting their role in micropropagation [

8] and focusing on medicinal plants [

9]. Moreover, the beneficial impact of AM fungi on nutrient uptake and root development has been reported in various species [

10]. The present study extends these findings to

Dalbergia latifolia, exploring the broader potential of AM fungi for improving the cultivation of this important timber species.

Additionally,

Dalbergia latifolia has gained attention for its potential role in agroforestry systems. A comprehensive tree database supports the selection of suitable species for agroforestry, further emphasizing the relevance of AM fungi in promoting the sustainable cultivation and ecological benefits of this species [

11].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Experimental Conditions

The nursery trials were conducted at the forest nursery of the Institute of Wood Science and Technology (IWST), Bengaluru, Karnataka, India (latitude 12°51′30.7″ N; longitude 76°84′83.9″ E). The study area, located in the Eastern Dry Zone, receives an average annual rainfall of approximately 900 mm, with temperatures ranging from 35°C in the summer to 8°C in the winter.

2.2. Planting Material Collection and Seed Treatment

Mature seeds of

Dalbergia latifolia were collected during the January seed-bearing season from a candidate plus tree in the Bhadra Tiger Reserve, Chikkamagaluru Forest Division, Karnataka, India. The seeds were assessed for health and viability according to the guidelines of the International Seed Testing Association [

12]. Prior to sowing, the seeds were surface-sterilized with a 2% Bavistin solution, thoroughly rinsed, and soaked in cold water for 24 hours to enhance germination.

2.3. Nursery Experiment and Experimental Design

Seeds of Dalbergia latifolia were germinated in a sand bed containing heat-sterilized sand (121°C for 1 hour). At 30 days post-germination, uniform, healthy seedlings, free from diseases and pests, were selected and transplanted into 15 × 12-inch plastic pots filled with an autoclaved mixture of red soil and sand (1:1, v/v). Arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungal inoculation was performed by applying 10 g of inoculum (containing spores and hyphal fragments) 2 inches away from the stem and 5 inches below the root zone during transplantation. Each treatment was replicated three times, resulting in a total of 30 plants for the study. The plants were maintained under nursery conditions with regular irrigation and proper care throughout the experimental period. Control plants were kept without AM fungal inoculation.

The experiment followed a randomized block design (RBD) with four treatments and three replications:

T1 (Control): D. latifolia without AM fungal inoculation.

T2: D. latifolia inoculated with Glomus mosseae.

T3: D. latifolia inoculated with Glomus fasciculatum.

T4: D. latifolia inoculated with Glomus leptotichum.

Growth parameters were recorded at 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month intervals post-inoculation.

2.4. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal (AM) Fungal Inoculum

The AM fungal species used in this study were Glomus mosseae, Glomus fasciculatum, and Glomus leptotichum. The inoculum was obtained from Dr. D. J. Bagyaraj, NASI Honorary Scientist & Chairman of the Centre for Natural Biological Resources and Community Development (CNBRCD), Bengaluru, Karnataka, India. The inoculum consisted of a sand-soil mixture containing AM fungal spores, mycelia, and colonized root fragments.

2.5. Estimation of AM Fungal Root Colonization

AM fungal colonization was assessed at 3-, 6-, and 12-month intervals following the method described by Phillips and Hayman [

13]. Root samples were randomly collected, cut into 1 cm segments, and cleared by autoclaving with 10% KOH at 108 kPa for 15 minutes. After neutralizing the alkalinity with 10% HCl, the roots were stained with 0.03% trypan blue in lactoglycerol. The stained root fragments were examined under a microscope for AM fungal structures, and the percentage of root colonization was calculated using the following formula:

2.6. Enumeration of AM Fungal Spores

Extrametrical chlamydospores were quantified using the wet sieving and decanting method described by Gerdemann and Nicolson [

14] (1963). A 100 g representative soil sample from each treatment was suspended in water, stirred thoroughly, and passed through a series of sieves (1000, 300, 205, 105, and 45 µm). The material retained on the bottom two sieves was transferred to a nylon mesh with an equivalent pore size. Spores retained on the mesh were then transferred to Petri dishes and counted under a microscope.

2.7. Morphological and Physiological Evaluations

The following growth and physiological parameters were assessed: plant height (cm), average leaf length (cm), average leaf width (mm), shoot length (cm), shoot width (mm), root length (cm), root width (cm), number of nodules, and total chlorophyll content in fresh leaves, measured using the method described by Arnon [

15] (1949).

2.8. Data Analysis

Experimental data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) in Microsoft Excel software. Treatment means were compared and ranked using Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT) at a 5% level of significance [

16].

3. Results

3.1. AM Fungal Colonization

The effects of AM fungal inoculation on the growth and physiological parameters of

Dalbergia latifolia were assessed over a 12-month period. Statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) were observed in various growth parameters between AM fungal-inoculated plants and the control group (T1), as shown in

Table 1. The percentage of AM fungal colonization, the number of vesicles, arbuscules, and sporulation in the rhizosphere increased progressively over time. The micropropagated plants inoculated with

Glomus fasciculatum (T3) showed 40% colonization, while the normal plants inoculated with the same species exhibited 35% colonization. The micropropagated plants demonstrated more prominent sporulation, which positively correlated with the number of vesicles and arbuscules, indicating higher mycorrhizal activity in the micropropagated plants.

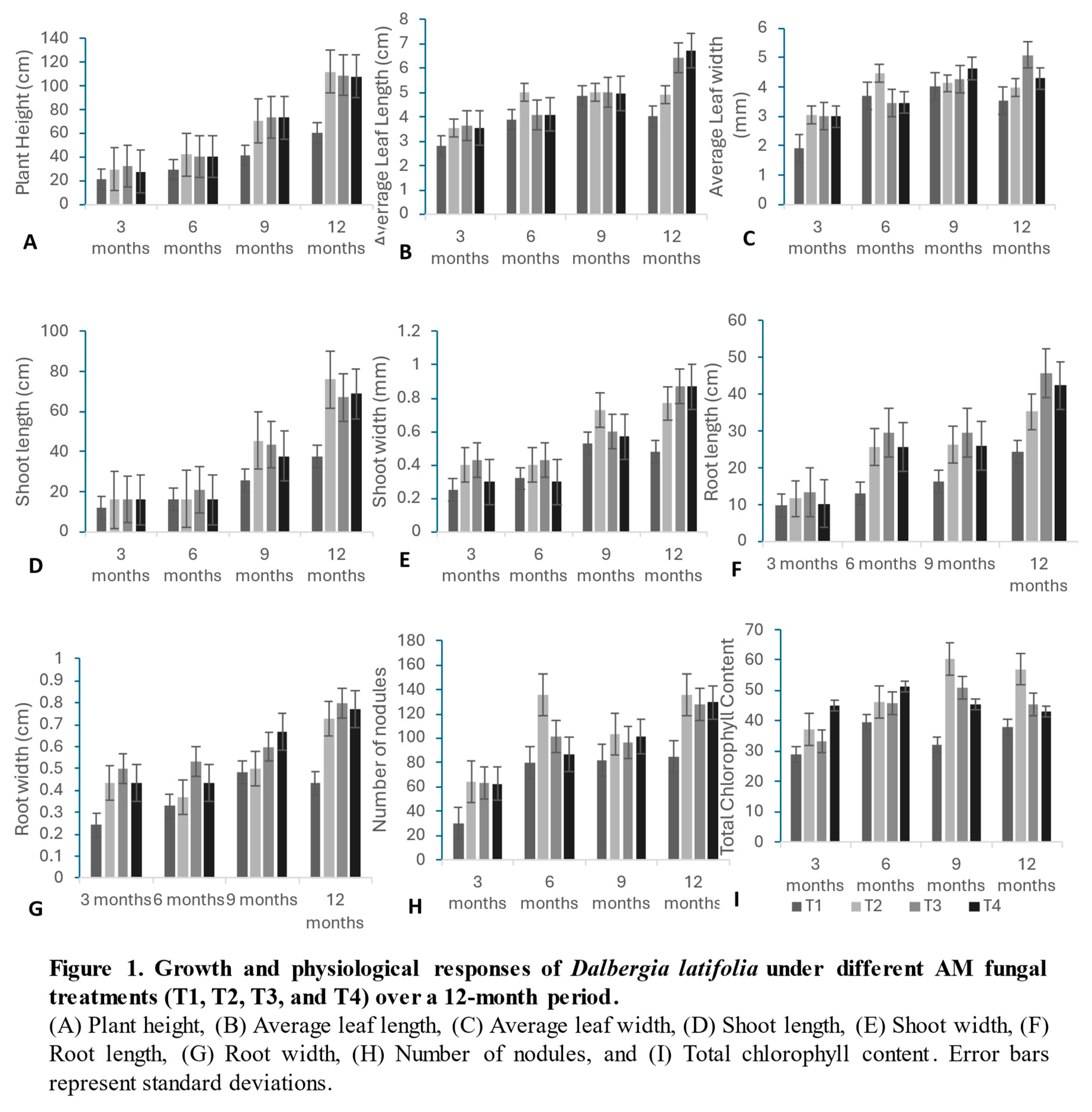

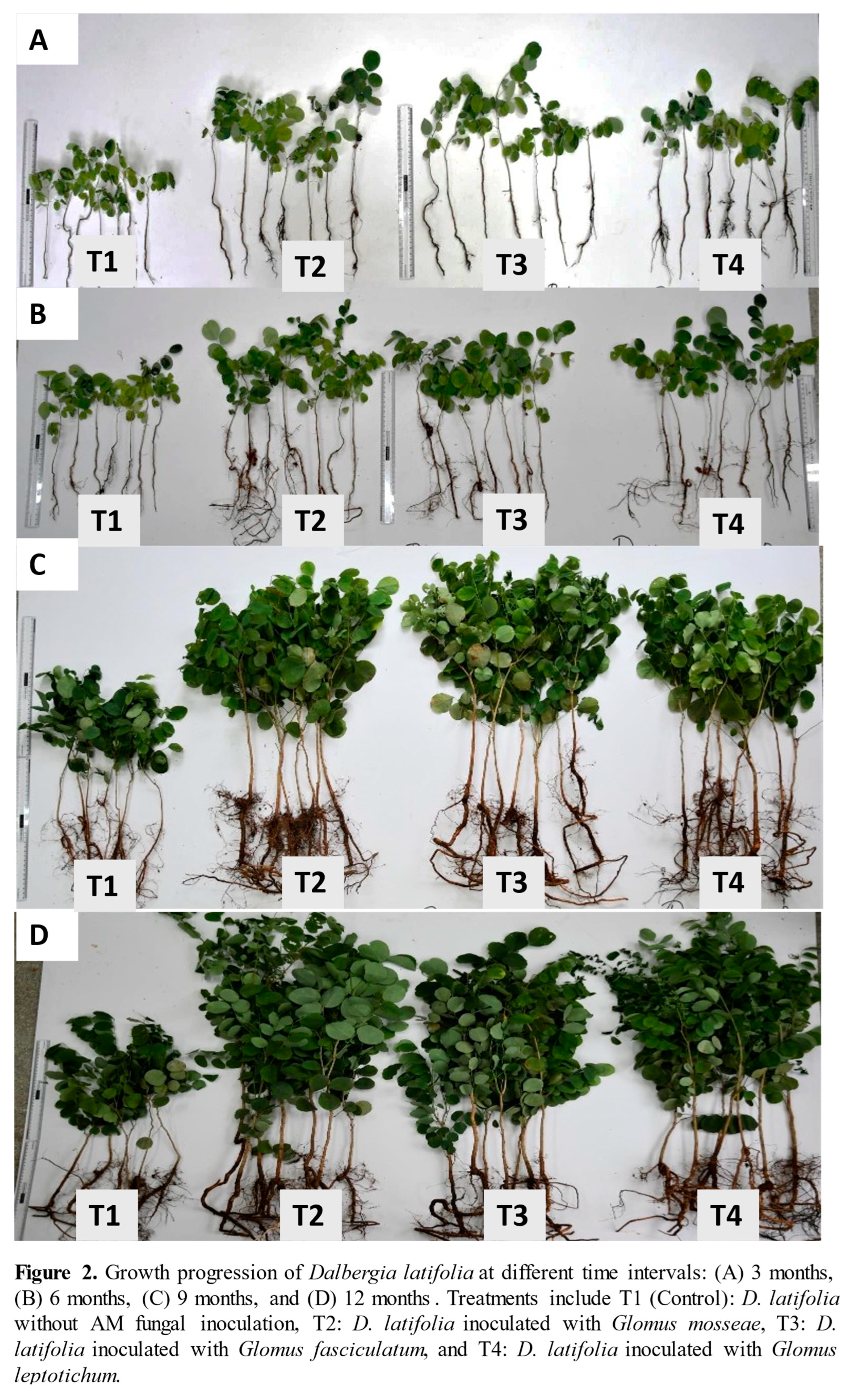

3.2. Growth Parameters

Growth improvements were evident in all AM fungal-inoculated plants compared to the control group. The plants inoculated with Glomus mosseae (T2) showed the highest plant height throughout the study, reaching a maximum height of 112 cm at 12 months. Both Glomus fasciculatum (T3) and Glomus leptotichum (T4) exhibited substantial height increases, significantly outperforming the control group. This growth pattern was statistically validated through ANOVA and F-tests, which showed significant differences at the 1% and 5% levels.

3.3. Leaf Parameters

Leaf length and leaf width improved significantly under AM fungal inoculation. At the end of the study, G. leptotichum (T4) recorded the longest leaves (6.733 cm), followed by G. fasciculatum (T3) at 6.433 cm. G. mosseae (T2) showed the widest leaves at earlier stages (3 and 6 months), but G. fasciculatum (T3) achieved the largest leaf width (5.1 mm) at 12 months.

3.4. Shoot Growth

Shoot length followed a similar upward trend. At 3 months, plants inoculated with G. fasciculatum (T3) had the longest shoots (16.33 cm). However, by 9 and 12 months, G. mosseae (T2) exhibited the highest shoot length, reaching 76 cm by 12 months, followed by G. fasciculatum (T3) and G. leptotichum (T4). Shoot width also increased, with G. fasciculatum (T3) and G. leptotichum (T4) achieving the largest shoot width (0.87 mm) by the study's conclusion.

3.5. Root Growth

Root length and root width were significantly greater in AM-inoculated plants compared to the control group. G. fasciculatum (T3) plants exhibited the longest roots, followed by G. leptotichum (T4) and G. mosseae (T2), while the control plants consistently displayed the shortest roots. The improvement in root development was mirrored in root width, with G. fasciculatum (T3) and G. leptotichum (T4) showing significant increases in root diameter.

3.6. Root Nodulation

Root nodulation was significantly influenced by AM fungal inoculation. G. mosseae (T2) consistently produced the highest number of nodules, followed by G. fasciculatum (T3) and G. leptotichum (T4), while the control group showed the fewest nodules, indicating enhanced nitrogen fixation in AM-inoculated plants.

3.7. Chlorophyll Content

Chlorophyll content, an indicator of photosynthetic efficiency, was significantly higher in AM fungal-inoculated plants at all time intervals. G. mosseae (T2) exhibited the highest chlorophyll content, reaching a peak of 60.33 at 9 months and maintaining a value of 57 at 12 months. Both G. fasciculatum (T3) and G. leptotichum (T4) showed significant increases in chlorophyll content compared to the control group, which displayed the lowest chlorophyll content throughout the study.

These results collectively indicate that AM fungal inoculation significantly enhances growth, root development, chlorophyll content, and nitrogen fixation in Dalbergia latifolia, underscoring the beneficial effects of mycorrhizal symbiosis on plant health and productivity.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study demonstrate that the inoculation of

Dalbergia latifolia with arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi significantly boosts growth parameters, aligning with similar observations in other medicinal plants. For instance, improved growth in Kalmegh was reported by Arpana and Bagyaraj [

17] as a result of treatment with AM fungi under phosphorus fertilization. The positive effects of AM fungi on nutrient uptake and chlorophyll content observed in this study are consistent with the findings of Zuccarini [

18], who reported that mycorrhizal infection enhances nutrient uptake and chlorophyll content in lettuce under saline irrigation. Furthermore, the positive influence of AM fungi on root development in

Dalbergia latifolia mirrors the results from Chiramel et al. [

19], who documented similar improvements in root growth in Andrographis paniculata when inoculated with AM fungi. Furthermore, this study highlights the contribution of AM fungi in improving nutrient uptake in

Dalbergia latifolia, as shown by Rajeshkannan et al. [

20], who reported increased growth and nutrient absorption in this species under tropical nursery conditions with the use of bioinoculants. The influence of AM fungi on soil properties is also well-supported in literature. Research by Syam Prasad et al. [

21] highlighted the ability of these fungi to positively influence soil physio-chemical properties, which, in turn, fosters plant growth. This view is also supported by Wahab et al. [

5], who showed that AM fungi help regulate plant growth and productivity, especially under biotic and abiotic stress conditions. These findings align with the conclusions of Martin and Heijden [

6], who emphasized the broader ecological and agricultural benefits of mycorrhizal symbiosis, particularly in promoting nutrient cycling and improving soil structure. The potential of AM fungi to enhance plant health and improve soil properties emphasizes their role in sustainable agriculture. Furthermore, the work of Gerdemann and Nicolson [

14] on spore extraction techniques underscores the importance of understanding the AM fungal life cycle for efficient inoculation, a critical aspect for future studies. Beyond the ecological and economic value of

Dalbergia latifolia as discussed by Arunkumar et al. [

1], the integration of AM fungi could play a key role in supporting the conservation of this species by promoting its growth and regeneration, as noted by Sasidharan et al. [

3].

The positive outcomes observed in this study further highlight the necessity of sustainable management practices for supporting the growth and conservation of

Dalbergia latifolia. Moreover,

Dalbergia latifolia holds significant promise for agroforestry systems, as indicated by Orwa et al. [

11], reinforcing the value of integrating AM fungi into these systems to boost productivity and maintain ecological balance. Overall, the results from this study stress the vital role of AM fungi in enhancing the growth and health of

Dalbergia latifolia and similar species, as demonstrated in several other studies by Smith and Read [

22] and Janos [

23]. The application of AM fungi in cultivating medicinal and forest species has considerable potential for improving productivity and fostering ecological sustainability.

Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrate the significant role of arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi in promoting the growth and development of Dalbergia latifolia seedlings. Inoculation with AM fungi, particularly Glomus mosseae, Glomus fasciculatum, and Glomus leptotichum, resulted in enhanced plant height, leaf size, shoot length, and root development compared to the control. Among the AM fungi, G. mosseae showed the best performance in terms of plant height and chlorophyll content, indicating its potential for improving the overall health and productivity of D. latifolia. Furthermore, the highest root colonization was observed in G. fasciculatum, highlighting its effectiveness in establishing a strong mycorrhizal symbiosis.

These findings underscore the importance of AM fungi in improving nutrient uptake, promoting better root and shoot growth, and enhancing photosynthetic efficiency. The study also emphasizes the potential of AM fungi as a sustainable method for improving the growth of D. latifolia, which holds significant ecological and economic value. Future studies should focus on optimizing AM fungal inoculation techniques for large-scale plantation management, which could support sustainable forestry practices and contribute to the conservation of this valuable species.

Author Contributions

Conception and design of the research: TNM and BSM; acquisition of data: BSM; analysis and interpretation of data: TNM and BSM; statistical analysis: BSM; drafting the manuscript: TNM and BSM; all authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the CAMPA, MoEF&CC, Government of India, Research grant for AICRP 28 Dalbergia latifolia Roxb.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their appreciation to the Director, Group Coordinator (Research), and Head of the Silviculture and Forest Management Division at IWST, Bengaluru, for their continued support. We also acknowledge the financial assistance from CAMPA, Government of India, for AICRP-28 on Dalbergia latifolia Roxb. Our sincere thanks go to Prof. D.H. Tejavathi (retired, Bangalore University) for her valuable guidance and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arunkumar, A. N.; Warrier, R. R.; Kher, M. M.; Teixeira da Silva, J. A. (2021). Indian rosewood (Dalbergia latifolia Roxb.): biology, utilisation, and conservation practices. Trees - Structure and Function, 36(3), 883–898. [CrossRef]

- Kirtikar, K. R.; Basu, B. D. Indian medicinal plants; International Book Distributor: Dehradun, India, 2005.

- Sasidharan, K. R.; Prakash, S.; Muraleekrishnan, K.; Kunhikannan, C. Population structure and regeneration of Dalbergia latifolia Roxb. and D. sissoides Wight & Arn. in Kerala and Tamil Nadu, India. International Journal of Advanced Research and Review 2020, 5(9), 51–66.

- Sujatha, M. P.; Thomas, P.; Thomas, M. F. E. J. Growth enhancement of Dalbergia latifolia through soil management techniques. KFRI Research Report No. 303; Kerala Forest Research Institute: Kerala, India, 2008; pp. 1–110.

- Wahab, A.; Muhammad, M.; Munir, A.; Abdi, G.; Zaman, W.; Ayaz, A.; Khizar, C.; Reddy, S. P. P. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in regulating growth, enhancing productivity, and potentially influencing ecosystems under abiotic and biotic stresses. Plants 2023, 12(17), 3102. [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.; Heijden, M. G. A. v. d. The mycorrhizal symbiosis: Research frontiers in genomics, ecology, and agricultural application. New Phytologist 2024, 242(4), 1486–1506. [CrossRef]

- Brundrett, M. C. (2009). Mycorrhizal fungi: Diversity and functional significance. Plant and Soil, 321(1–2), 417–431.

- Kapoor, R.; Sharma, D.; Bhatnagar, A. K. Arbuscular mycorrhizae in micropropagation systems and their potential applications. Scientia Horticulturae 2008, 116, 227–239. [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, B.; Joe, M. M.; Jaleel, C. A. Response of some medicinal plants to vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizal inoculations. Journal of Scientific Research 2009, 1, 381–386. [CrossRef]

- Mridha, M. A. U.; Dhar, P. P. Biodiversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization and spore population in different agroforestry trees and crop species growing in Dinajpur, Bangladesh. Journal of Forestry Research 2007, 18, 91–96. [CrossRef]

- Orwa, C.; Mutua, A.; Kindt, R.; Jamnadass, R.; Simons, A. Agroforest tree database: A tree reference and selection guide (Version 4.0). 2009.

- International Seed Testing Association (ISTA). (1996). International rules for seed testing. Seed Science and Technology, 24(1), 1-335.

- Phillips, J. M.; Hayman, D. S. Improved procedures for clearing roots and staining parasitic and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi for rapid assessment of infection. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 1970, 55, 158–161.

- Gerdemann, J. W.; Nicolson, T. H. Spores of mycorrhizal Endogone extracted from soil by wet sieving and decanting. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 1963, 46, 235–244.

- Arnon, D. I. (1949). Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiology, 24(1), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Little, T. M.; Hills, F. J. Agricultural experimentation; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1978.

- Arpana, J.; Bagyaraj, D. J. Response of Kalmegh to an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus and a plant growth-promoting rhizo microorganism at two levels of phosphorus fertilizer. American-Eurasian Journal of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences 2007, 2, 33–38.

- Zuccarini, P. Mycorrhizal infection ameliorates chlorophyll content and nutrient uptake of lettuce exposed to saline irrigation. Plant Soil and Environment 2007, 53, 283–289. [CrossRef]

- Chiramel, T.; Bagyaraj, D. J.; Patil, C. S. P. Response of Andrographis paniculata to different arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Journal of Agricultural Technology 2006, 2, 221–228.

- Rajeshkannan, V.; Dhanapal, V.; Thangavelu, M. Influence of bioinoculants on growth and nutrient uptake in Dalbergia latifolia under tropical nursery conditions. In Microbiological research in agrosystem management; Rajesh Kannan, V., Ed.; Springer India Private Limited: New Delhi, India, 2013; pp. 207–234.

- Syam Prasad, S.; Ashok Kumar, K.; Sushma, P. R.; Ramadevi, B. Role of the AM fungi in physio-chemical properties of soil, study in Sathupally forest area, Khammam (District) Telangana State with reference to Anogeissus latifolia and Bambusa arundinacea. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences 2020, 9(09), 2754–2769.

- Smith, S. E., & Read, D. J. (2008). Mycorrhizal Symbiosis (3rd ed.). Academic Press.

- Janos, D. P. (2007). Mycorrhizas and tropical soils. In Ecology of Arbuscular Mycorrhizas in Forests (pp. 173-185). Springer, Dordrecht.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).