Submitted:

23 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

To investigate the potential role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) in the resistance of Lycium barbarum to disease stress, two types of AMF, Funneliformis mosseae and Rhizophagus intraradices, were selected as materials. Lycium barbarum was inoculated with AMF and pathogenic bacteria in potting soil under controlled conditions, and we analyzed the antioxidant capacity of the fungi against root rot and changes in disease-process-related protein activities. In addition, we performed transcriptome analysis to explore the physiological and molecular changes in AMF in the prevention and control of root rot in L. barbarum ‘Ningqi No.1’ cultivar. The results show that AMF can promote the growth and development of L. barbarum plants while also increasing antioxidant enzyme and disease-resistant protease activity. The ‘Ningqi No.1’–AMF symbiont triggered several key biological pathways, including the peroxisomal signaling pathway, after F. oxysporum infestation. In conclusion, AMF can prevent root rot in L. barbarum, providing valuable evidence that AMF symbiotically improves the ability of L. barbarum to resist root rot through its molecular mechanism.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Materials

2.2. Disease Treatment

2.3. Plant Harvest and Measurement of Samples

2.5. Differential Expression Analysis and Functional Enrichment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Transcriptome Analysis of Plant Leaves

3. Results

3.1. AMF Colonization in the Root System of L. Barbarum

3.2. Effect of AMF on the Growth Characteristics of L. Barbarum Seedlings

3.2.1. Effect of Inoculation with AMF on Growth Indexes of L. Barbarum

3.2.2. Effect of AMF Inoculation on the Growth of L. Barbarum

3.2.3. Trends in root system changes in ‘Ningqi No.1’–AMF symbiosis

3.3.1. Effect of AMF inoculation on the incidence and disease index of L. barbarum root rot.

3.3.2. Effect of L. Barbarum root rot on Antioxidant Enzyme Activities in Seedlings

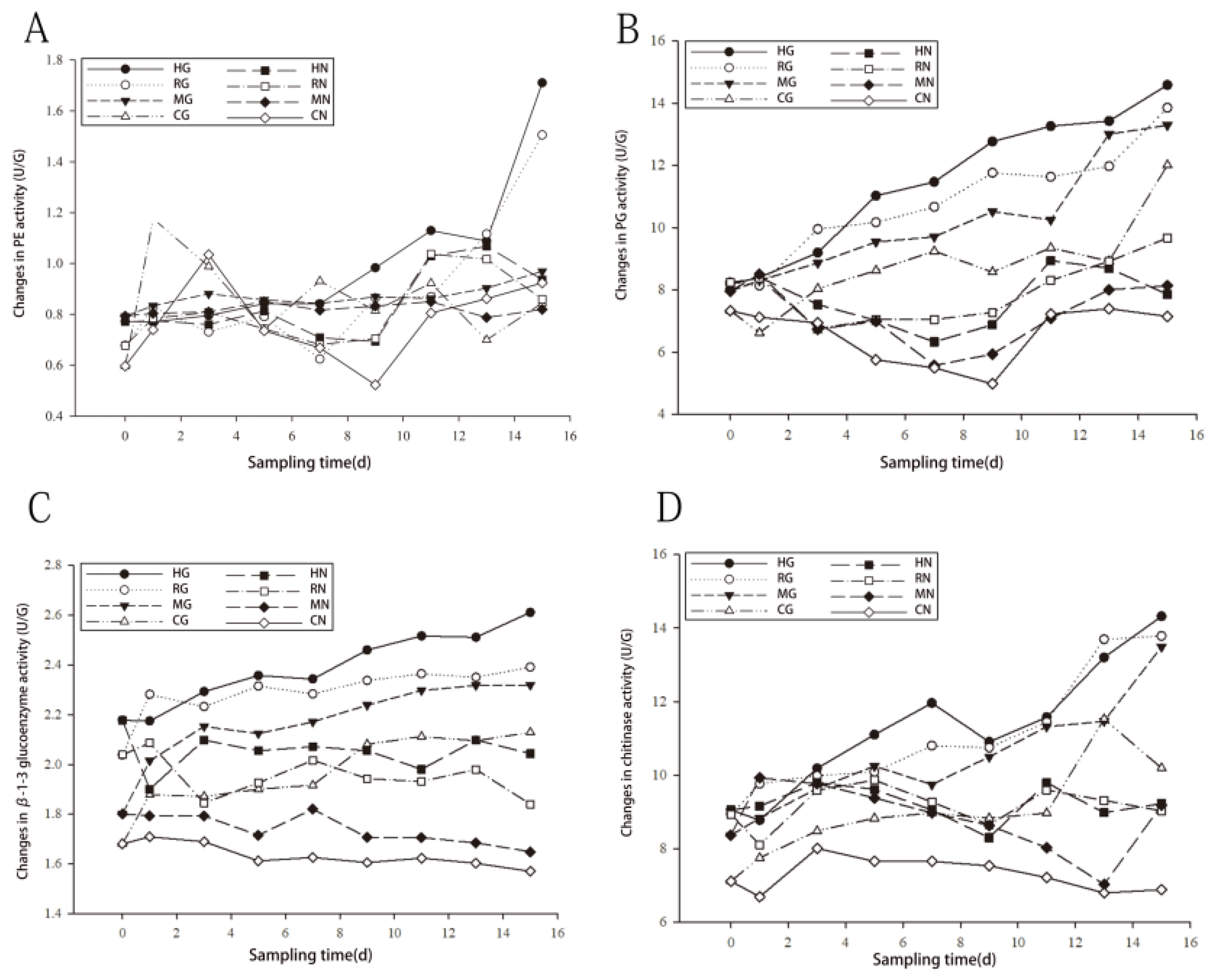

3.3.3. Effect of L. Barbarum Root rot on Disease-Resistant Protease Activity in Seedlings

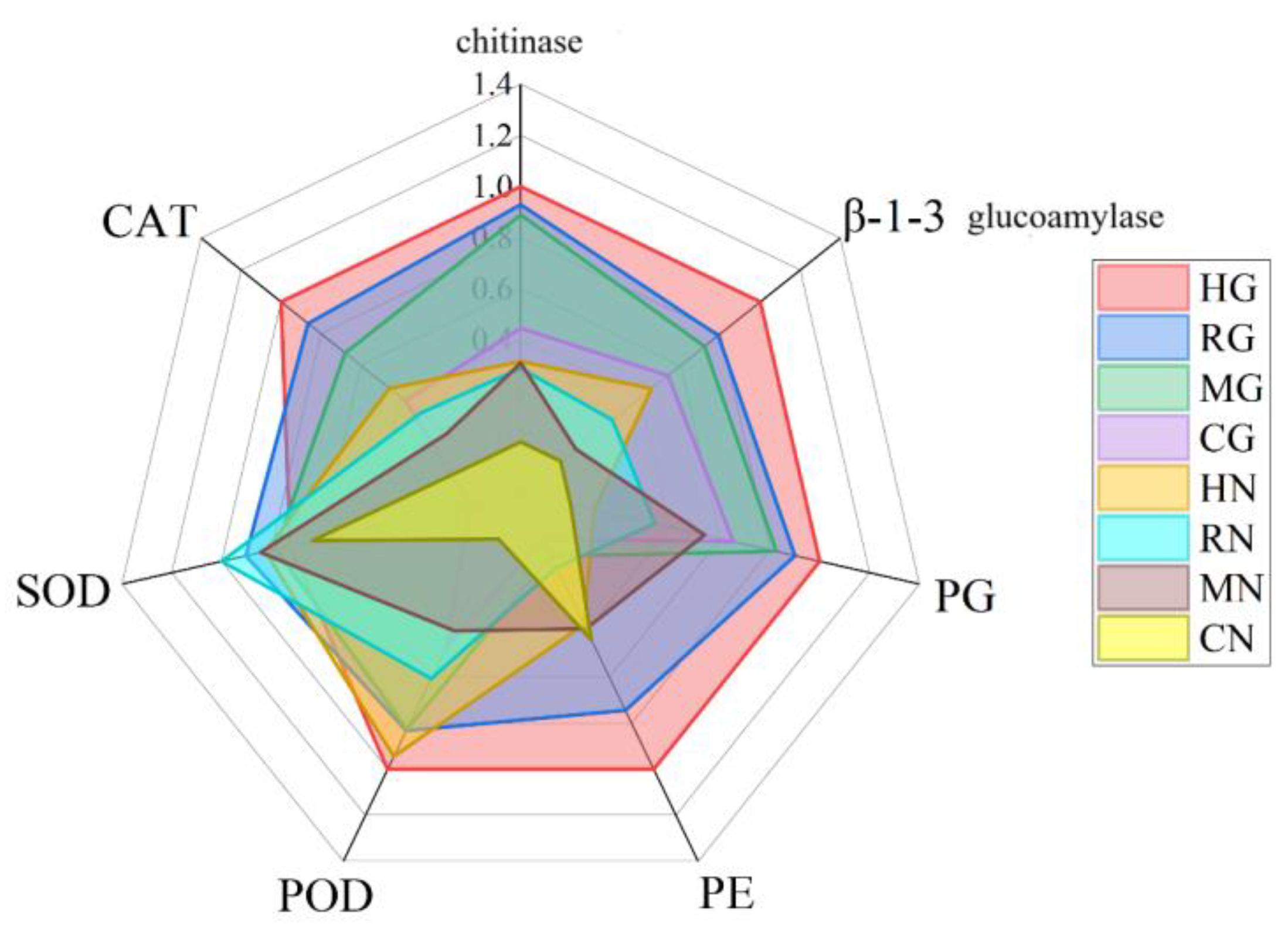

3.3.4. Analysis of the Combined Effect of l. Barbarum Root rot Disease on the Activities of Antioxidant Enzymes and Disease-Resistant Proteins in the Symbiont

3.4.1. Data Quality Control Analysis

3.4.2. Transcript Matching Evaluation

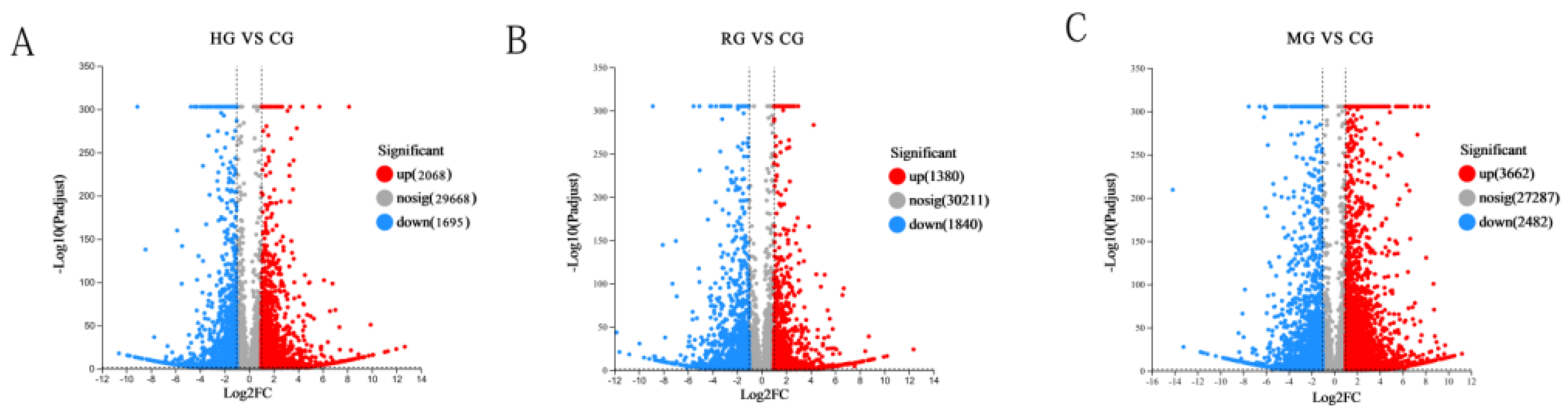

3.4.3. Differentially Expressed Gene Analysis

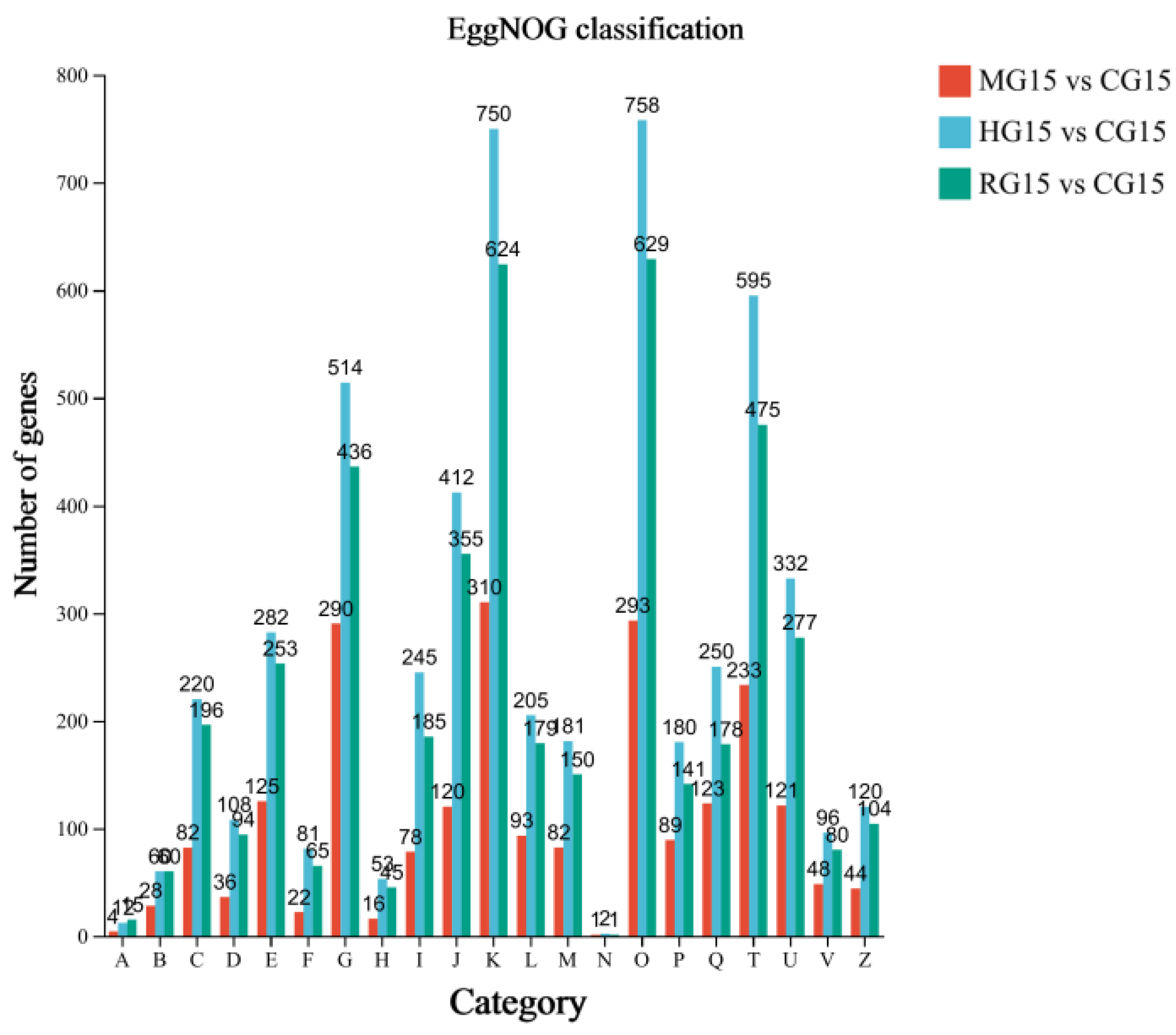

3.4.4. EggNOG Annotation Analysis of Differential Genes

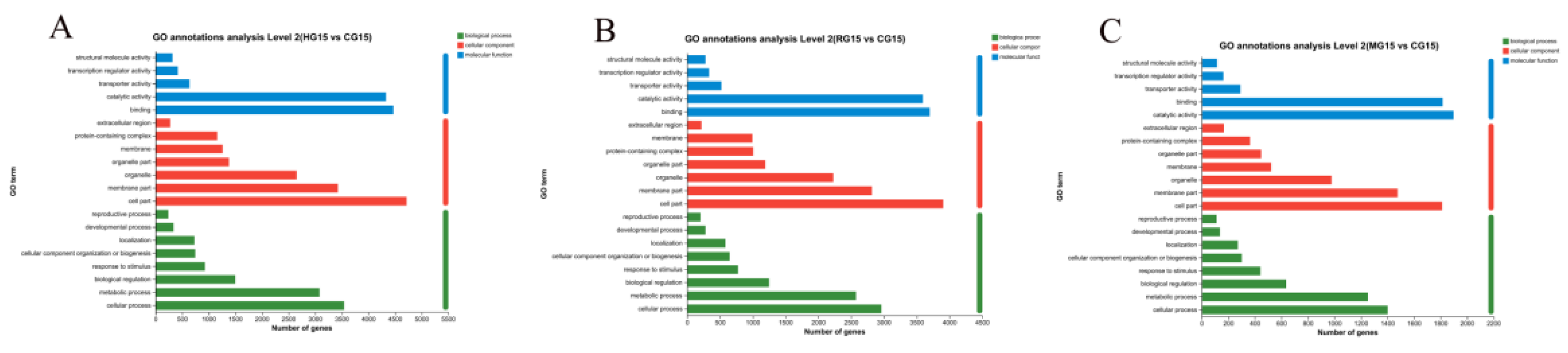

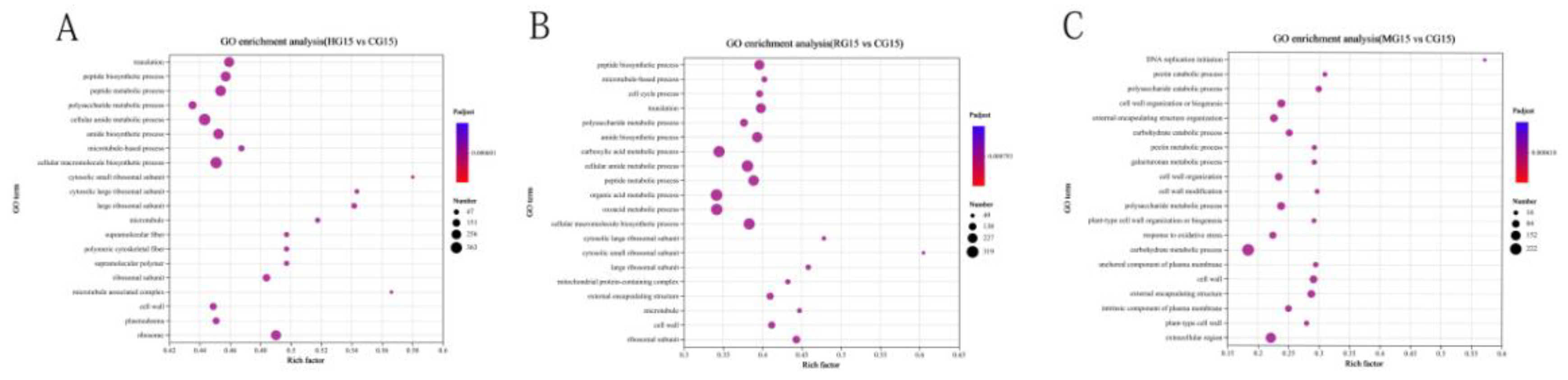

3.4.5. Go Function Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

3.4.6. KEGG Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

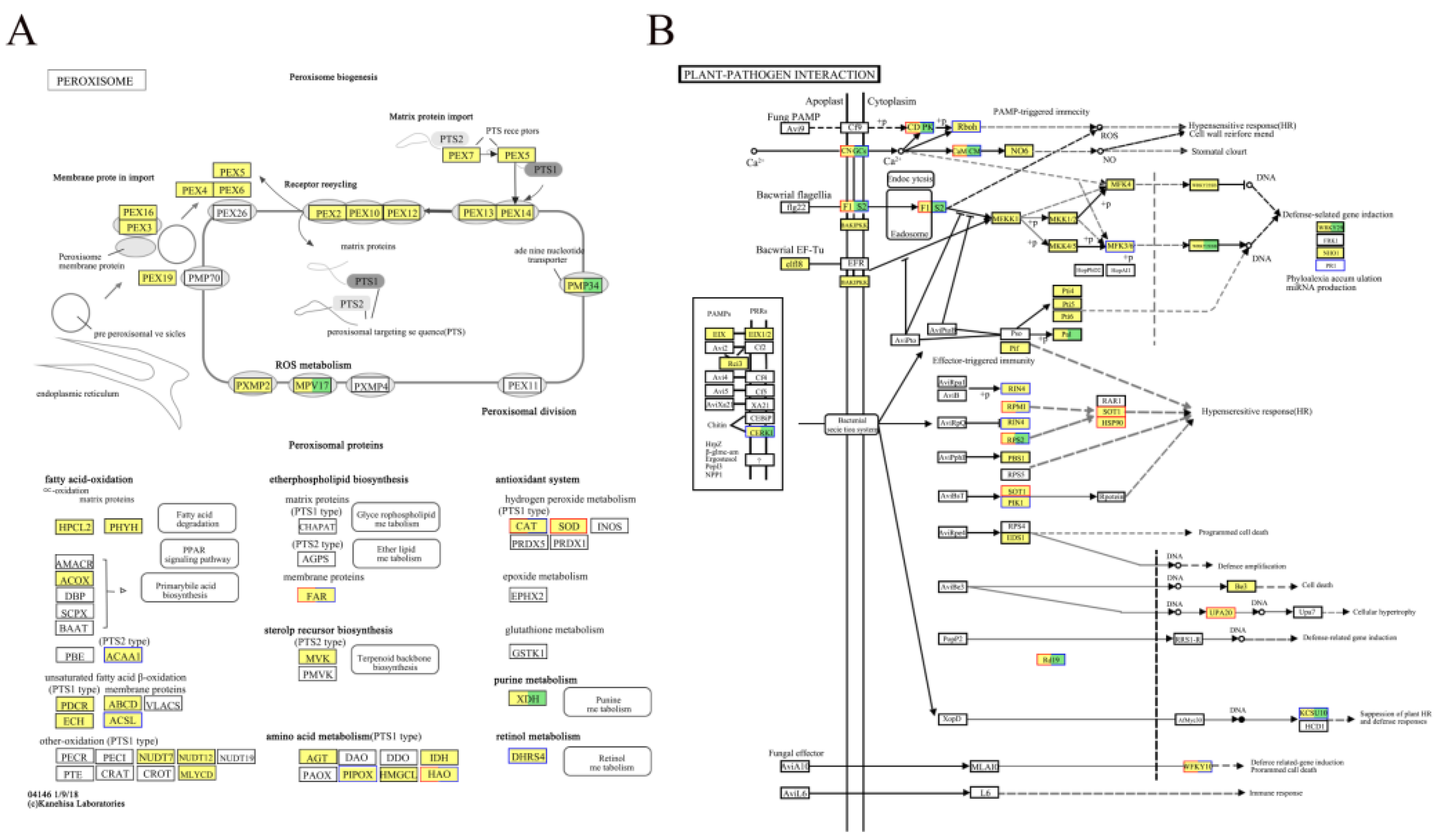

3.4.7. Analysis of DEGs in Defense-Related Pathways in L. Barbarum

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Martin,F. ;Van,D..The mycorrhizal symbiosis: Research frontiers in genomics, ecology, and agricultural application. New Phytologist. 2024, 242, 1486–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang,M.;Ji,S.;Duan,G.;Fan,G.;Li,J..Wang,Z..Staining Methods on Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Lycium barbarum Roots and the Relationship between Colonization Rate and Soil Factors.Journal of Shandong University (Science Edition).1-11[2024-10-17].

- Zhang,D; Xia,T; Dang,S; Fan,G; Wang,Z. Investigation of Chinese wolfberry (lycium spp.) germplasm by restriction site-associated DNA sequencing (RAD-seq). Biochemical Genetics. 2018, 56, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OĞUZ,İ;OĞUZ,H.;KAFKAS,N..Evaluation of fruit characteristics of various organically-grown goji berry (Lycium barbarum L., Lycium chinense Miller) species during ripening stages.Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 2021, 101,103846. [CrossRef]

- Jia,C; An,Y; Du,Z; Gao,H; Su,J; Xu,C. Differences in soil microbial communities between healthy and diseased lycium barbarum cv. Ningqi-5 plants with root rot. Microorganisms. 2023, 11, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; He, K.; Zhang, T.; Tang, D.; Li, R.; Jia, S. Physiological responses of Goji berry (Lycium barbarum L.) to saline-alkaline soil from Qinghai region, China. Scientific Reports. 2019, 9, 12057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwaremwe,C.;Yue,L.;Liu,Y.;Liu,Y.;Tian,Y.;Zhao,X.;Wang,Y.;Xie,Z.;Zhang,Y.;Cui,Zeng,W.;Ruo,Y..Molecular identification and pathogenicity of Fusarium and Alternaria species associated with root rot disease of wolfberry in Gansu and Ningxia provinces, China. Plant Pathol. 2020, 70, 397–406. [CrossRef]

- He,J.;Zhang,X.;Wang,Q.;Li,N.;Ding,D.;Wang,B.Optimization of the Fermentation Conditions of Metarhizium robertsii and Its Biological Control of Wolfberry Root Rot Disease. Microorganisms. 2023, 11, 2380. [CrossRef]

- Osman,N.;Awal,A..Plant tissue culture-mediated biotechnological approaches in Lycium barbarum L. (Red goji or wolfberry). Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2023, 64, 521–532. [CrossRef]

- Semchenko,M.;Barry,KE;De,V.;Mommer,L;Moora,M;Maciá-Vicente,JG.Deciphering the role of specialist and generalist plant–microbial interactions as drivers of plant–soil feedback. New Phytologist. 2023, 234, 1929–1944. [CrossRef]

- Neal,JC. Biological control of weeds in turfgrass:Opportunities and misconceptions. Pest Management Science. 2024, 80, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das,R.;Bharadwaj,P.;Thakur,D..Insights into the functional role of Actinomycetia in promoting plant growth and biocontrol in tea (Camellia sinensis) plants. Arch Microbiol. 2024, 206, 65. [CrossRef]

- ALHadidi,N.;Pap,Z.;Ladányi,M.;Szentpéteri,V.;Kappel,N..Mycorrhizal Inoculation Effect on Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam) Seedlings. Agronomy. 2021, 11, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Berdeni,D.;Cotton,T.;Daniell,T.;Bidartondo,M.;Cameron,D.;Evans,K..The Effects of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungal Colonisation on Nutrient Status, Growth, Productivity, and Canker Resistance of Apple (Malus pumila). Frontiers in microbiology, 2018, 9, 1461. [CrossRef]

- Li,J; Cai,B; Chang,S; Yang,Y; Zi,S; Liu,T. Mechanisms associated with the synergistic induction of resistance to tobacco black shank in tobacco by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and β-aminobutyric acid. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma,X;Geng,Q;Zhang,H;Bian,C;Chen,H.;Jiang,D;Xu,X.Global negative effects of nutrient enrichment on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, plant diversity and ecosystem multifunctionality. New Phytologist . 2021, 229, 2957–2969. [CrossRef]

- Branco,S; Schauster,A; Liao,H; Ruytinx,J. Mechanisms of stress tolerance and their effects on the ecology and evolution of mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytologist. 2022, 235, 2158–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma,J; Li,Y; Zhou,H; Qi,L; Zhang,Z; Zheng,Y; Yu,Z; Muhammad,Z; Yang,X; Xie,Y. Chitooligosaccharides and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi alleviate the damage by phytophthora nicotianae to tobacco seedlings by inducing changes in rhizosphere microecology. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2024, 215, 108986–10.1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng,M.;Tang,M.;Zhang,F.;Huang,Y.;Yang,B..Effect of soil factors on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in northwest saline alkaline soil. Acta Pedologica Sinica, 2008, 45, 758–763.

- Guo,H.;Lu,L.;Su,C.;Duan,G.;Fan,G.. Effects of Microbial Agents on Growth and Soil Properties of Lycium barbarum L. Journal of Shenyang Agricultural University. 2022, 53, 476–482. [CrossRef]

- Liu,Z; Fan,C; Xiao,J; Sun,S; Gao,T; Zhu,B; Zhang,D. Metabolomic and transcriptome analysis of the inhibitory effects of bacillus subtilis strain Z-14 against fusarium oxysporum causing vascular wilt diseases in cucumber. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2023, 71, 2644–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo,I;Kume,T;Kho,L.;Katayama,A;Makita,N;Ikeno,H;Ide,J;Ohashi,M.Spatial and temporal patterns of root dynamics in a bornean tropical rainforest monitored using the root scanner method. Plant and Soil. 2019, 443, 323–335. [CrossRef]

- Schaarschmidt,S; Fischerm,A; Zuther,E; Hincha,D. Evaluation of seven different RNA-seq alignment tools based on experimental data from the model plant arabidopsis thaliana. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021, 21, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu,X.;Wang,M.;Fan,Z.;Li,J.;Yin,H.Molecular Mechanisms of Seasonal Gene Expression in Trees. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1666. [CrossRef]

- Casamassimi,A.;Ciccodicola,A.Transcriptional Regulation: Molecules, Involved Mechanisms, and Misregulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1281. [CrossRef]

- Tian,W.;Hou,C.;Re,Z.;Wang,C.;Zhao,F.;Dahlbeck,D.Hu,S.;Zhang,L.;Niu,Q.;Li,L.Staskawicz,B.;Luan,S.;A calmodulin-gated calcium channel links pathogen patterns to plant immunity. Nature. 2019, 572, 131–135. [CrossRef]

- Zeng,J.;Ma,S.;Liu,J.;Qin,S.;Liu,X.;Li,T.;Liao,Y.;Shi,Y.;Zhang,J..Organic Materials and AMF Addition Promote Growth of Taxodium ‘zhongshanshan’ by Improving Soil Structure. Forests 2023, 14, 731. [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri,R.;Pandey,A.;Sharma,M.,Anil,P.;Aketi,R.;Hemant,S.;Rakesh,K.;Raghvendra,N.;Sunil,D..Enhanced soil carbon storage and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal biomass in a long-term nutrient management under soybean-based cropping system. Environ Sci Pollut Res. [CrossRef]

- Pu,C.;Ge,Y.;Yang,G.;Zheng,H.;Guan,W.;Chao,Z.;Shen,Y.;Liu,S.;Chen,M.;Huang,L.. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance disease resistance of Salvia miltiorrhiza to Fusarium wilt. Frontiers in plant science. 2022, 13, 975558. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han,S.;Na,L.;Rongchao,Z.;Hu,X.;Zhang,W.;Zhang,B.;Li,X.;Wang,Z..Study on signal transmission mechanism of arbuscular mycorrhizal hyphal network against root rot of Salvia miltiorrhiza. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 16936. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xie, W.; Chen, B. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Induced Plant Resistance against Fusarium Wilt in Jasmonate Biosynthesis Defective Mutant and Wild Type of Tomato. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 422. [CrossRef]

- Rueda-Puente,E.;Murillo-Amador,B.;Castellanos-Cervantes,T.;García-Hernández,J.;Tarazòn-Herrera,M.;Moreno M.;Gerlach B..Effects of plant growth promoting bacteria and mycorrhizal on Capsicum annuum L. var. aviculare ([Dierbach] D'Arcy and Eshbaugh) germination under stressing abiotic conditions. Plant physiology and biochemistry:PPB, 2010, 48, 724–730. [CrossRef]

- Yuan,J.;Shi,K.;Zhou,X.;Wang,L.;Xu,C.;Zhang,H.;Zhu,G.;Si,C.;Wang,J.;Zhang,Y.. Interactive impact of potassium and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on the root morphology and nutrient uptake of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.). Frontiers in microbiology. 2023, 13, 1075957. [CrossRef]

- El-Mesbahi,M.;Azcón,R.;Ruiz-Lozano,J.;R-Lozano,J.;Aroca,R..Plant potassium content modifies the effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis on root hydraulic properties in maize plants. Mycorrhiza. 2012, 22, 555–564. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta-González,U.;Leyva-Mir,S.;Silva-Rojas,H.;Rebollar-Alviter,A..Preventive and Curative Effects of Treatments to Manage Strawberry Root and Crown Rot Caused by Neopestalotiopsis rosae. Plant disease, 2024, 108, 1278–1288. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ku,Y.;Xu,G.;Su,S.;Cao,C..Effects of biological agents on soil microbiology, enzyme activity and fruit quality of kiwifruit with root rot. Soil Research, 2022, 60, 279–293. [CrossRef]

- Burns,R.;DeForest,J.;Marxsen,J.;Sinsabaugh,R.;Stromberger,M.;Wallenstein,M.;Weintraub, M.;Zoppini,A..Soil enzymes in a changing environment: Current knowledge and future directions. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 2013, 58, 216–234. [CrossRef]

- Cariddi,C.;Mincuzzi,A.;Schena,L.;Ippolito,A.;Sanzani,S.First report of collar and root rot caused by Phytophthora nicotianae on Lycium barbarum. J Plant Pathol. 2018, 100, 361. [CrossRef]

- Huang,L.;Chen,D.;Zhang,H;Song,Y.;Chen,H.;Tang,M..Funneliformis mosseae Enhances Root Development and Pb Phytostabilization in Robinia pseudoacacia in Pb-Contaminated Soil. Front. Microbiol 2019, 10, 2591. [CrossRef]

- Wang,F.;Sun,Y.;Shi,Z.Arbuscular Mycorrhiza Enhances Biomass Production and Salt Tolerance of Sweet Sorghum. Microorganisms, 2019, 7, 289. [CrossRef]

- Gao,X.;Zhao,S.;Xu,Q.;Xiao,J..Transcriptome responses of grafted Citrus sinensis plants to inoculation with the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Glomus versiforme. Trees, 2016, 30, 1073–1082. [CrossRef]

- Yang,M.;Guo,H.;Duan,G.;Wang,Z.;Fan,G.;Li,J..Role and Mechanism of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Enhancing Plant Stress Resistance and Soil Improvement:areview. China Powder Science and Technology. 2024, 30, 164–172.

| Treatment | Height | Aboveground fresh weight | Belowground fresh weight | Stem diameter | Aboveground dry weight | Belowground dry weight | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HN | 57.00±15.43a | 15.18±7.35a | 7.89±6.40a | 4.30±0.72a | 3.90±1.95ab | 5.20±3.65ab | |

| RN | 54.60±21.40a | 11.93±5.24a | 6.26±4.48a | 4.01±0.65a | 2.38±1.34ab | 1.81±1.23b | |

| MN | 43.71±11.99a | 8.46±3.94a | 4.12±2.66ab | 3.33±0.45b | 2.41±0.32ab | 2.36±1.18b | |

| CN | 27.09±17.43b | 2.88±1.52b | 0.76±0.65b | 2.23±0.44c | 0.93±0.48b | 0.39±0.30b |

| Treatment | Total number of roots | Number of root tips | Total root length | Root total projected area | Total root surface area | Total root volume | Average root diameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN | 2746 ± 529 b | 1734 ± 300 b | 836.23 ± 91.19 b | 4768.74 ± 701.41 b | 14981.43 ± 2203.55 b | 4350.30 ± 748.87b | 0.43 ± 0.01a |

| HN | 5246 ± 869 a | 2205 ±532 ab | 1528.67 ± 363.85 a | 8666.90 ± 2353.95 a | 27227.88 ± 7395.16 a | 7753.69 ± 1275.35a | 0.46 ± 0.02a |

| MN | 5077 ± 1050 a | 2455 ± 546 ab | 1634.84 ± 265.16 a | 8482.65 ± 1427.42 ab | 26649.04 ± 4484.36 ab | 5633.69 ± 1059.65a | 0.43 ± 0.01a |

| RN | 6338 ± 1150 a | 3142 ± 498 a | 1877.55 ± 361.88 a | 10141.97 ± 2225.95 a | 31861.93 ± 6993.01 a | 7467.66 ± 2734.90ab | 0.44 ± 0.01a |

| Treatment | Incidence rate | Disease index | Control effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| HG | 13.75 | 8.75 | 80.97 |

| RG | 14.76 | 8.57 | 81.35 |

| MG | 30 | 18.67 | 59.37 |

| CG | 67.56 | 45.95 | - |

| HN | - | - | - |

| RN | - | - | - |

| MN | - | - | - |

| CN | MN | RN | HN | CG | MG | RG | HG | GROUP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 49951456 | 46475274 | 51554401.3 | 55658190 | 49071956 | 51113339.3 | 46280264 | 42515694 | Raw data |

| 7542669856 | 7017766374 | 7784714601 | 8404386690 | 7409865356 | 7718114239 | 6988319864 | 6419869794 | Primitive base |

| 48944720.7 | 45582256.67 | 50424263.3 | 53647578.67 | 47311750.67 | 49951282.67 | 44910294 | 41067138 | Clean reads |

| 7266931233 | 6825129239 | 7520928583 | 8009319978 | 7066515915 | 7455341015 | 6694249619 | 6121374903 | Clean bases |

| 96.8533333 | 97.1266667 | 96.8166667 | 97.2166667 | 97.21 | 96.9533333 | 96.7866667 | 96.8066667 | Q20 (%) |

| 94.5166667 | 94.89 | 94.4366667 | 95.0433333 | 95.0133333 | 94.6266667 | 94.3766667 | 94.4133333 | Q30 (%) |

| 42.7233333 | 42.45666667 | 42.4033333 | 42.31666667 | 42.45333333 | 42.32333333 | 42.61333333 | 42.52333333 | GC content (%) |

| Sample | Total reads | Total mapped | Multiply mapped | Uniquely mapped |

| HG-1 | 40552074 | 38609423(95.21%) | 1483136(3.66%) | 37126287(91.55%) |

| HG-2 | 40436220 | 38470676(95.14%) | 1412317(3.49%) | 37058359(91.65%) |

| HG-3 | 42213120 | 40173019(95.17%) | 1484422(3.52%) | 38688597(91.65%) |

| RG-1 | 47432464 | 45038106(94.95%) | 1828490(3.85%) | 43209616(91.1%) |

| RG-2 | 46208982 | 43933057(95.07%) | 1747784(3.78%) | 42185273(91.29%) |

| RG-3 | 41089436 | 39073561(95.09%) | 1574836(3.83%) | 37498725(91.26%) |

| MG-1 | 48905964 | 46283124(94.64%) | 1695796(3.47%) | 44587328(91.17%) |

| MG-2 | 53053692 | 50118148(94.47%) | 1849052(3.49%) | 48269096(90.98%) |

| MG-3 | 47894192 | 45167590(94.31%) | 1666538(3.48%) | 43501052(90.83%) |

| CG-1 | 45863360 | 42098606(91.79%) | 1558693(3.4%) | 40539913(88.39%) |

| CG-2 | 50489018 | 46260846(91.63%) | 1720050(3.41%) | 44540796(88.22%) |

| CG-3 | 45582874 | 41720056(91.53%) | 1553915(3.41%) | 40166141(88.12%) |

| HN-1 | 51497724 | 48389092(93.96%) | 1720144(3.34%) | 46668948(90.62%) |

| HN-2 | 56842560 | 53333300(93.83%) | 1914805(3.37%) | 51418495(90.46%) |

| HN-3 | 52602452 | 49294176(93.71%) | 1773999(3.37%) | 47520177(90.34%) |

| RN-1 | 51755466 | 49113072(94.89%) | 2142014(4.14%) | 46971058(90.76%) |

| RN-2 | 48393240 | 45826708(94.7%) | 1972168(4.08%) | 43854540(90.62%) |

| RN-3 | 51124084 | 48350244(94.57%) | 2066359(4.04%) | 46283885(90.53%) |

| MN-1 | 44065952 | 41845056(94.96%) | 1599851(3.63%) | 40245205(91.33%) |

| MN-2 | 49442120 | 46871985(94.8%) | 1791651(3.62%) | 45080334(91.18%) |

| MN-3 | 43238698 | 40929798(94.66%) | 1565924(3.62%) | 39363874(91.04%) |

| CN-1 | 52580114 | 50462974(95.97%) | 1903266(3.62%) | 48559708(92.35%) |

| CN-2 | 48787804 | 46576392(95.47%) | 1826575(3.74%) | 44749817(91.72%) |

| CN-3 | 45466244 | 43419217(95.5%) | 1679233(3.69%) | 41739984(91.8%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).