Submitted:

07 August 2023

Posted:

09 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

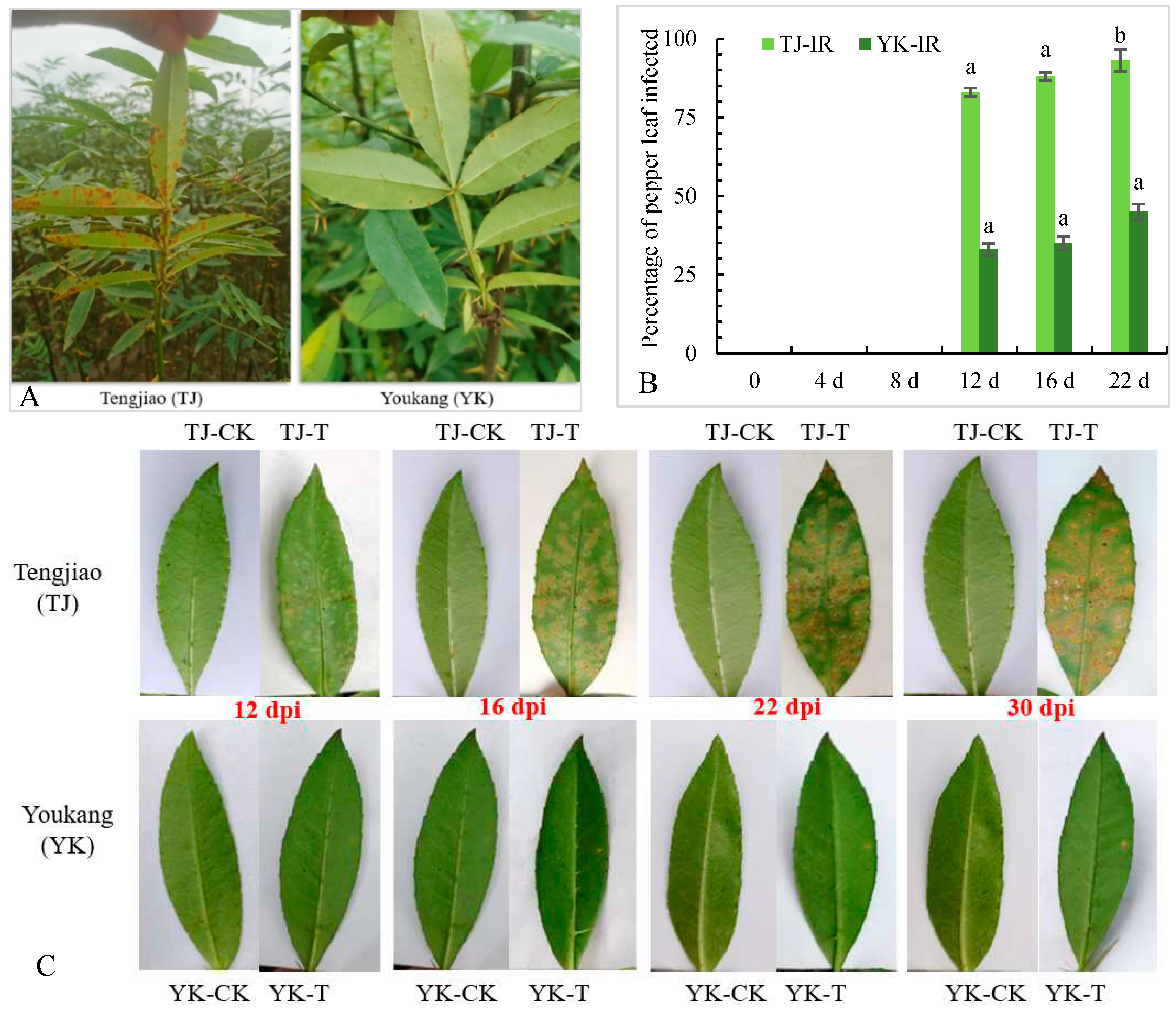

2.1. Analysis of rust resistance of ‘Tengjiao’ and ‘Youkang’ Chinese pepper leaves

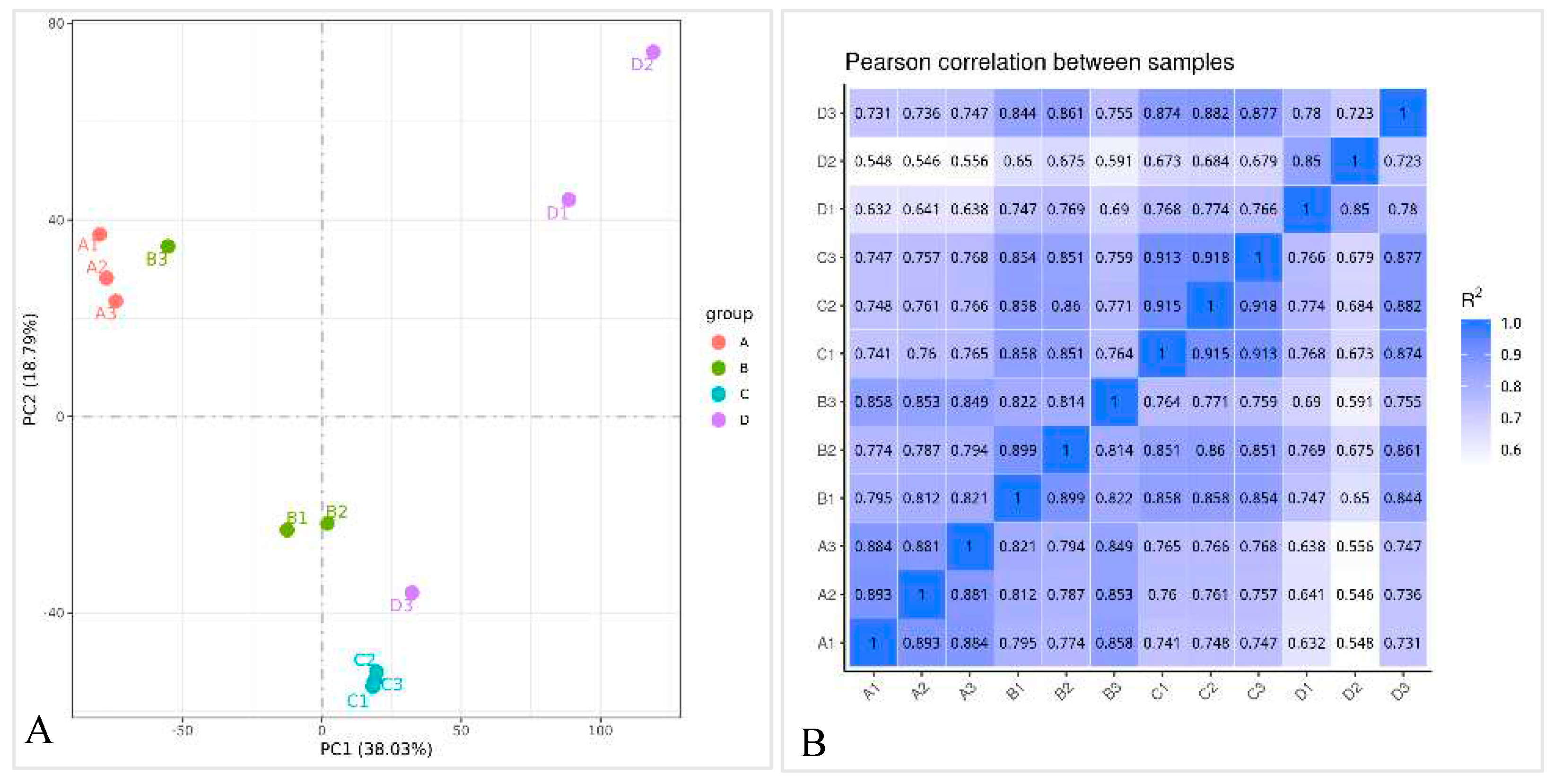

2.2.1. RNA quality determination and sequencing results

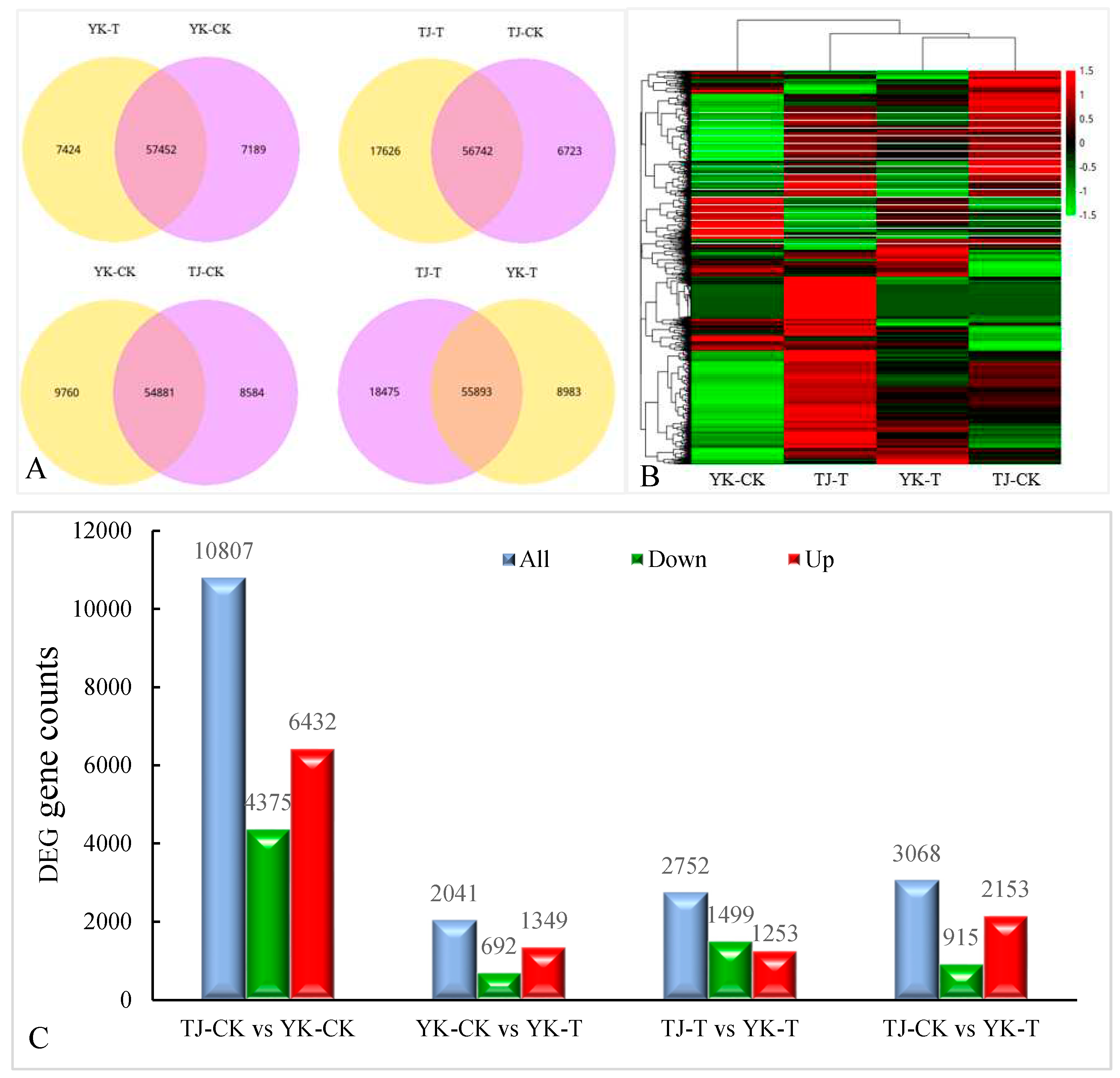

2.2.2. Transcriptome-wide identification of DEGs and functional analysis

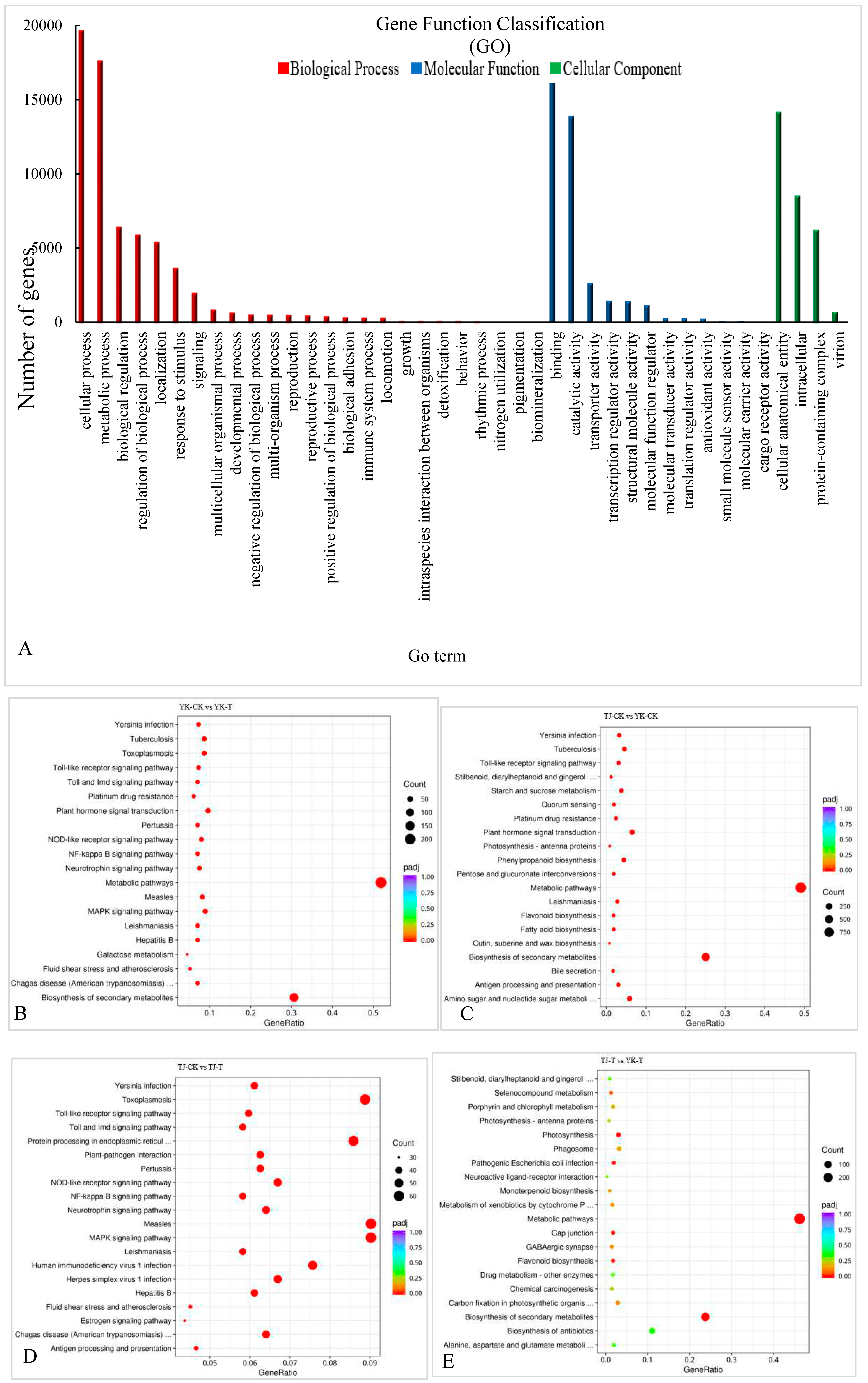

2.2.3. GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs in ‘Tengjiao’ and ‘Youkang’ infected with C. zanthoxyli

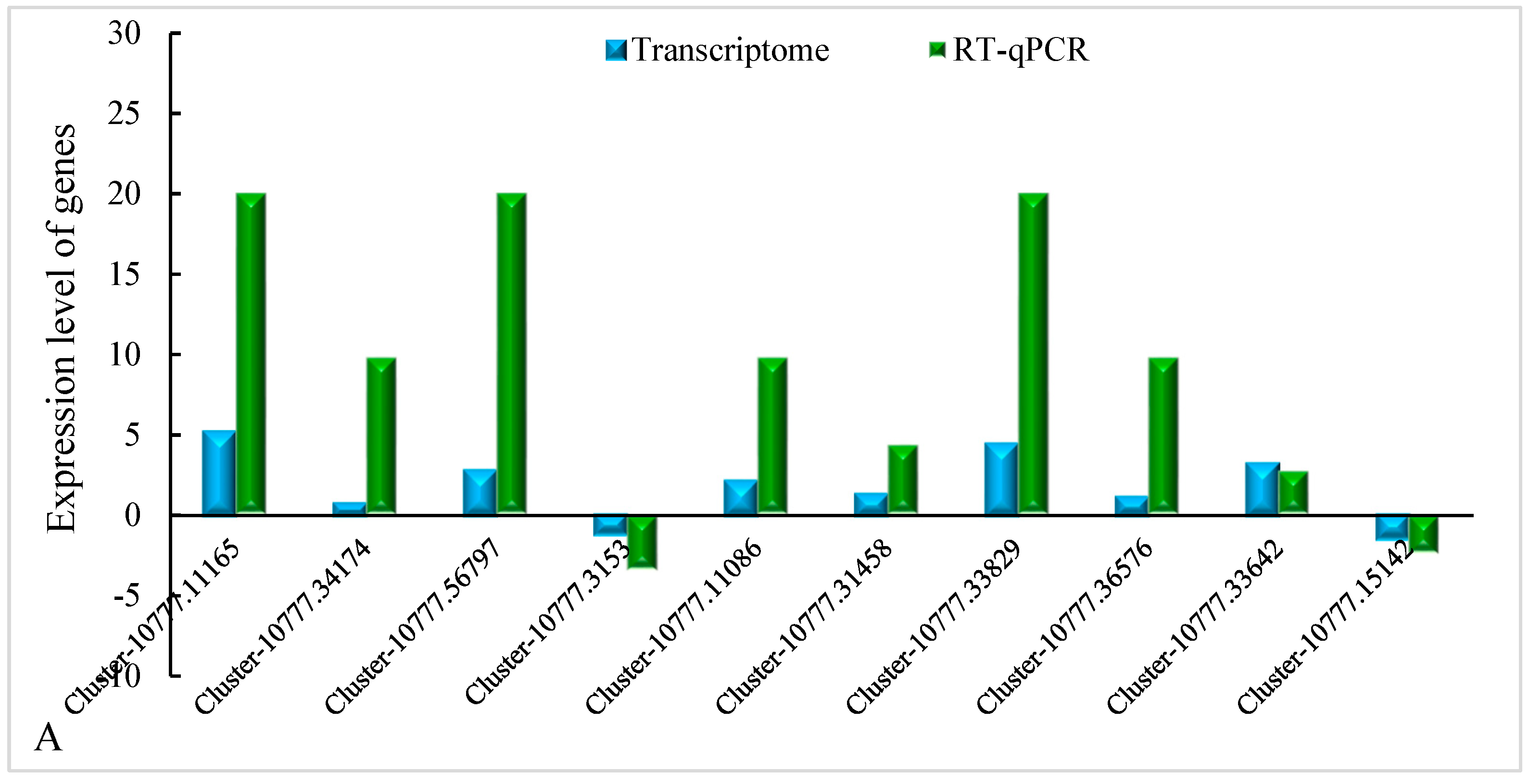

2.2.4. Verification by qRT-PCR

2.3. Metabolome data analysis

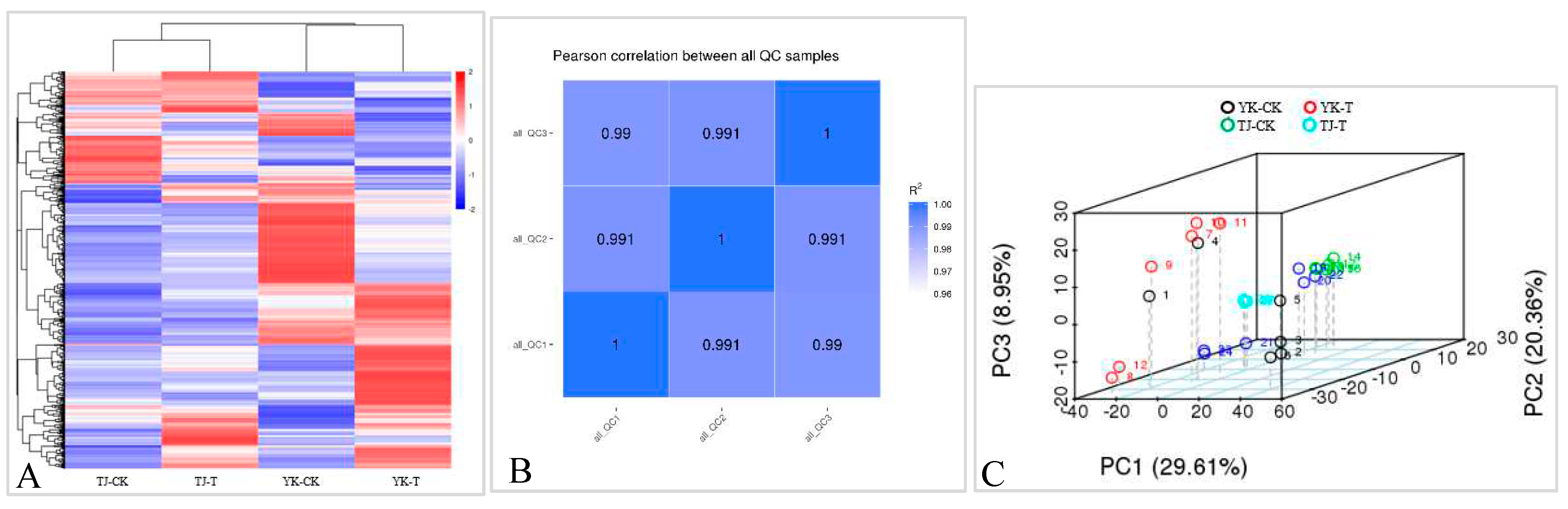

2.3.1. Data quality control

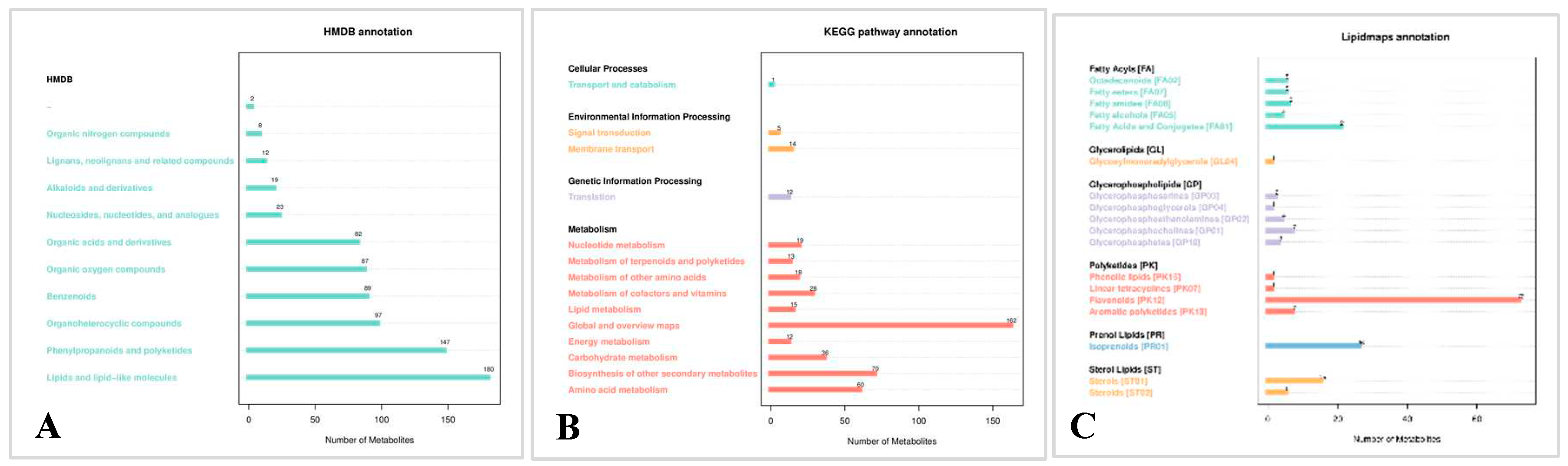

2.3.2. Metabolite pathways and classification notes

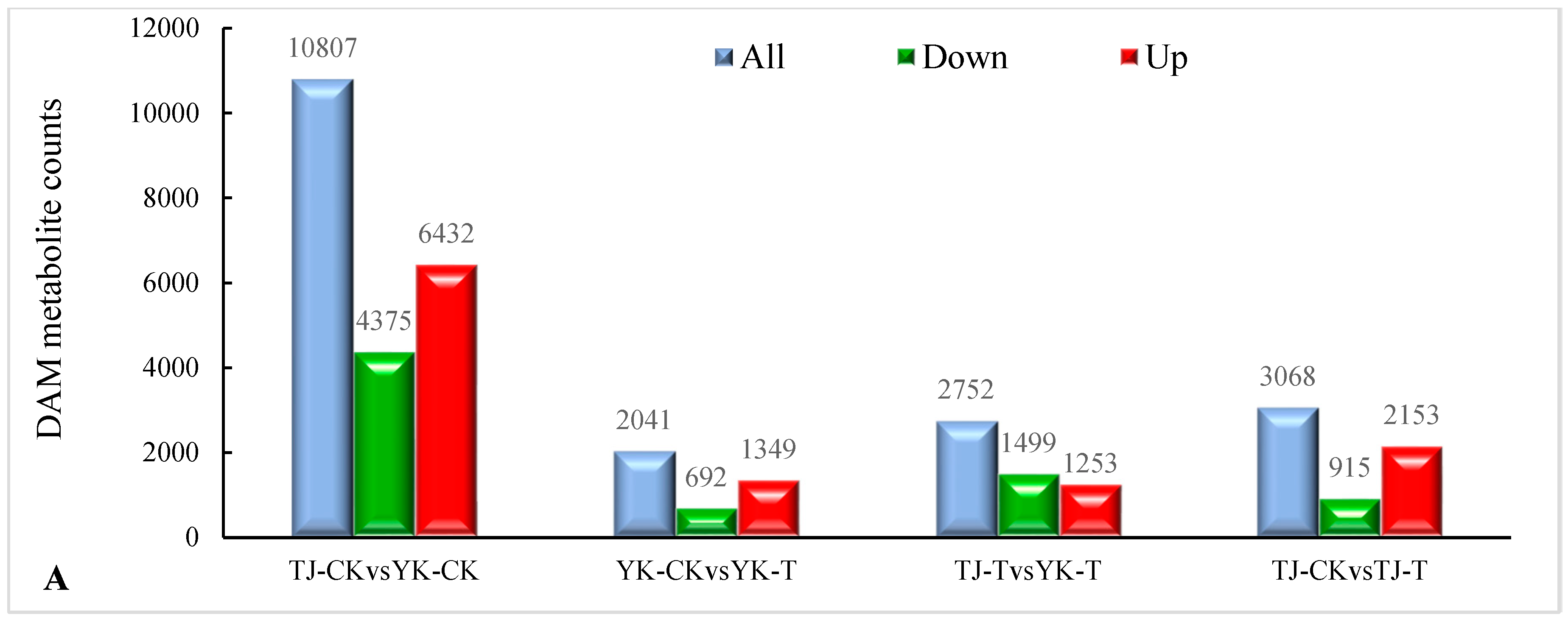

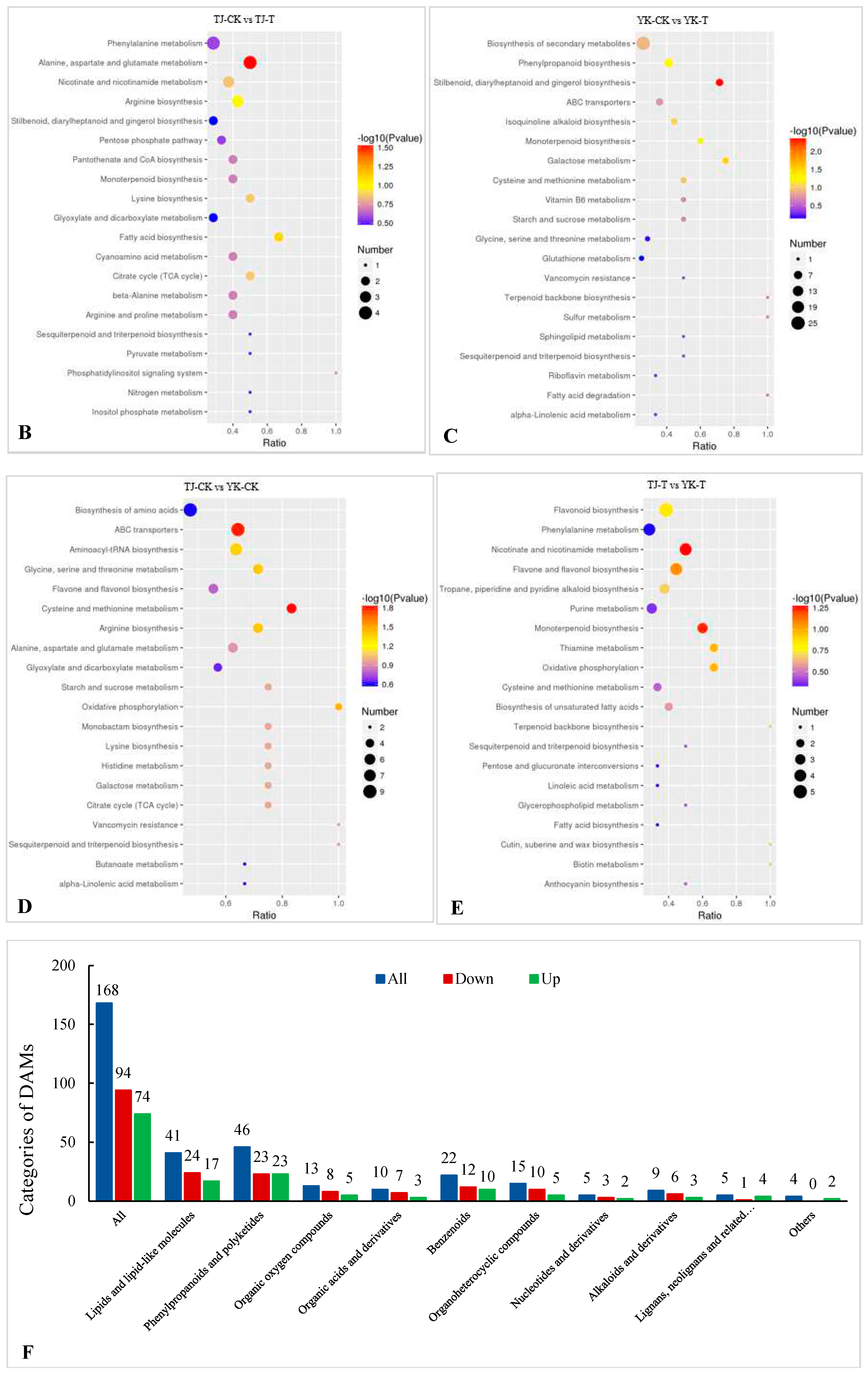

2.3.3. DAM screening and KEGG pathway annotation

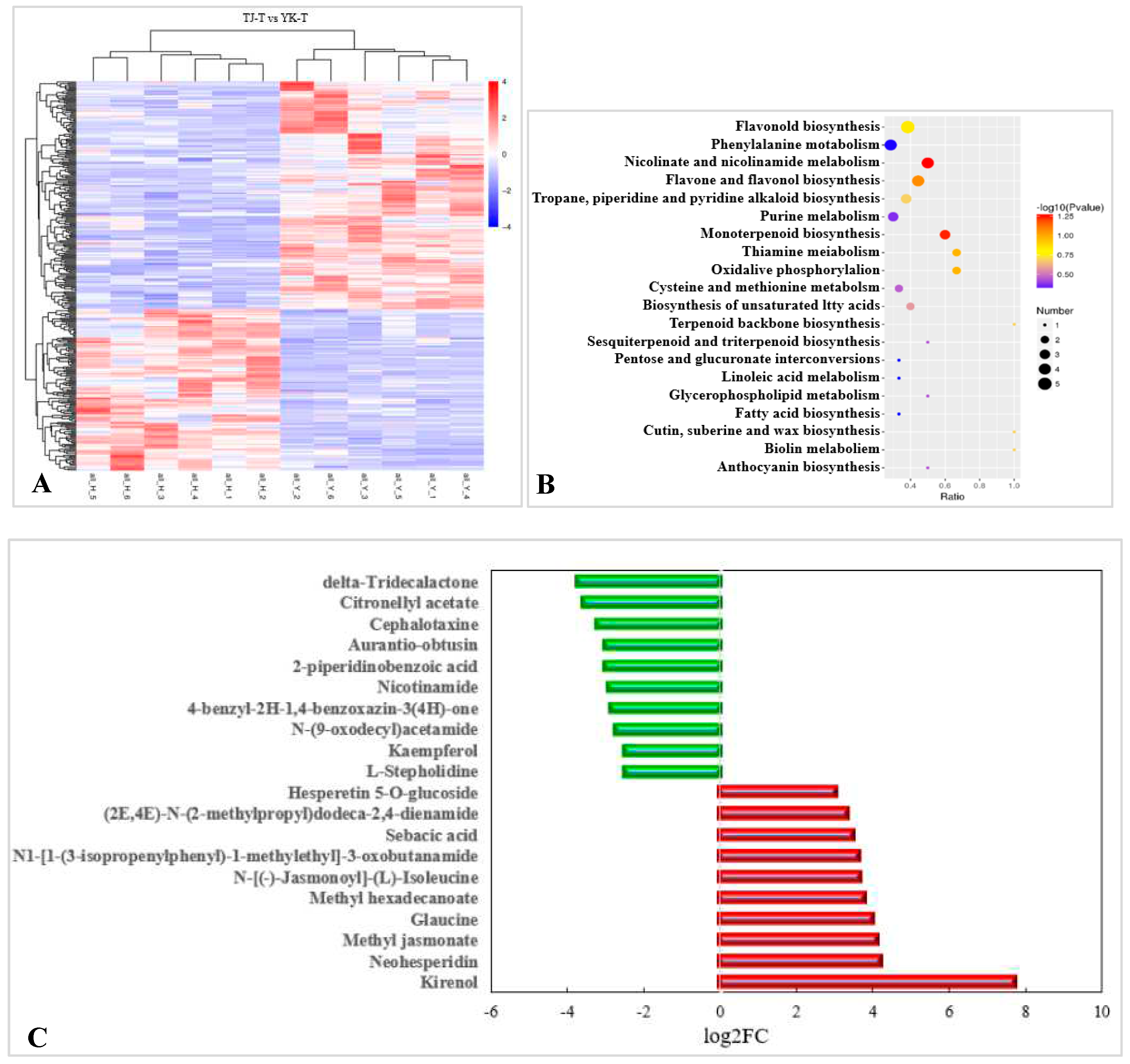

2.3.4. Metabolomic analysis of TJ and YK infected by C. zanthoxyli

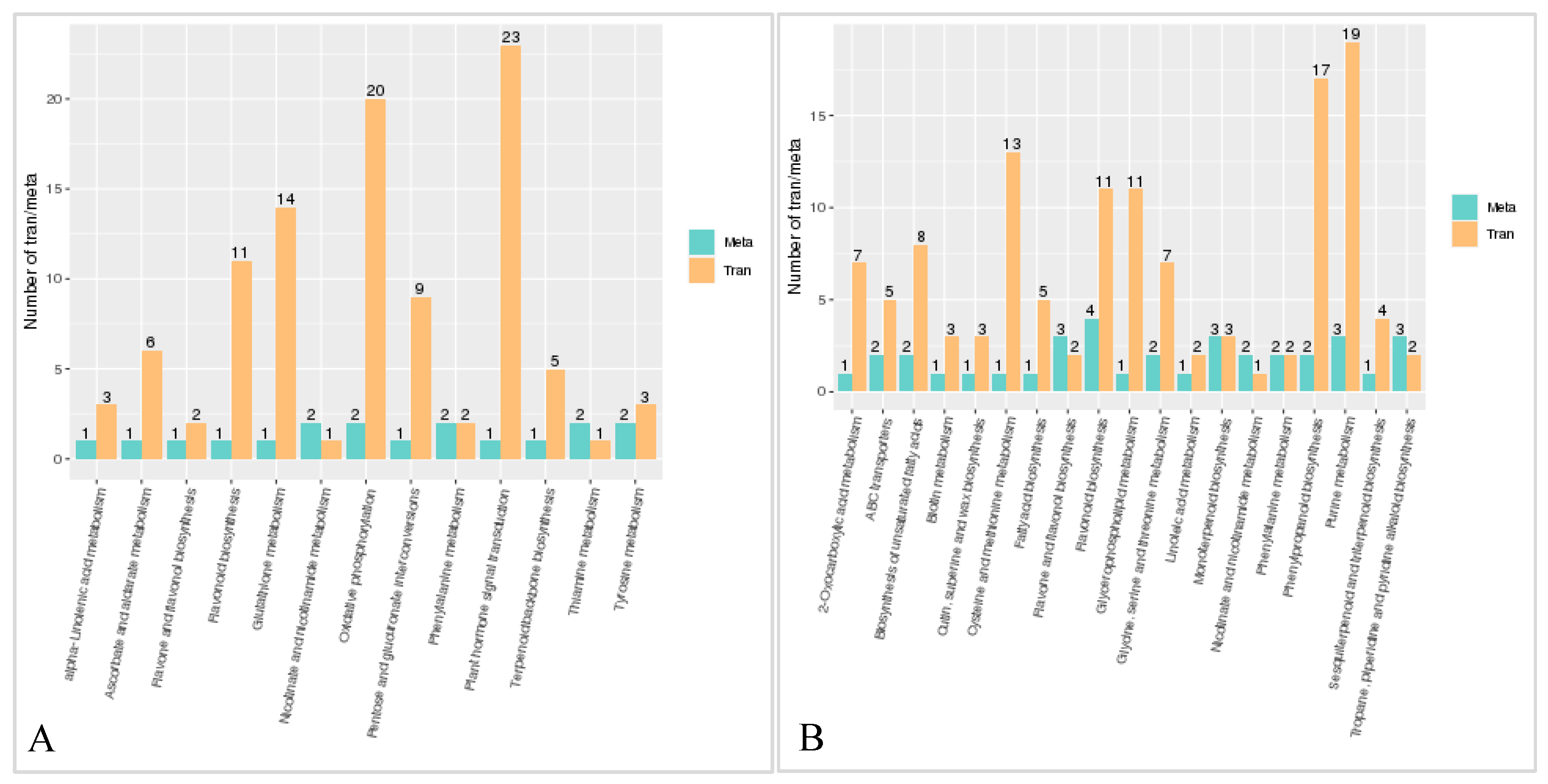

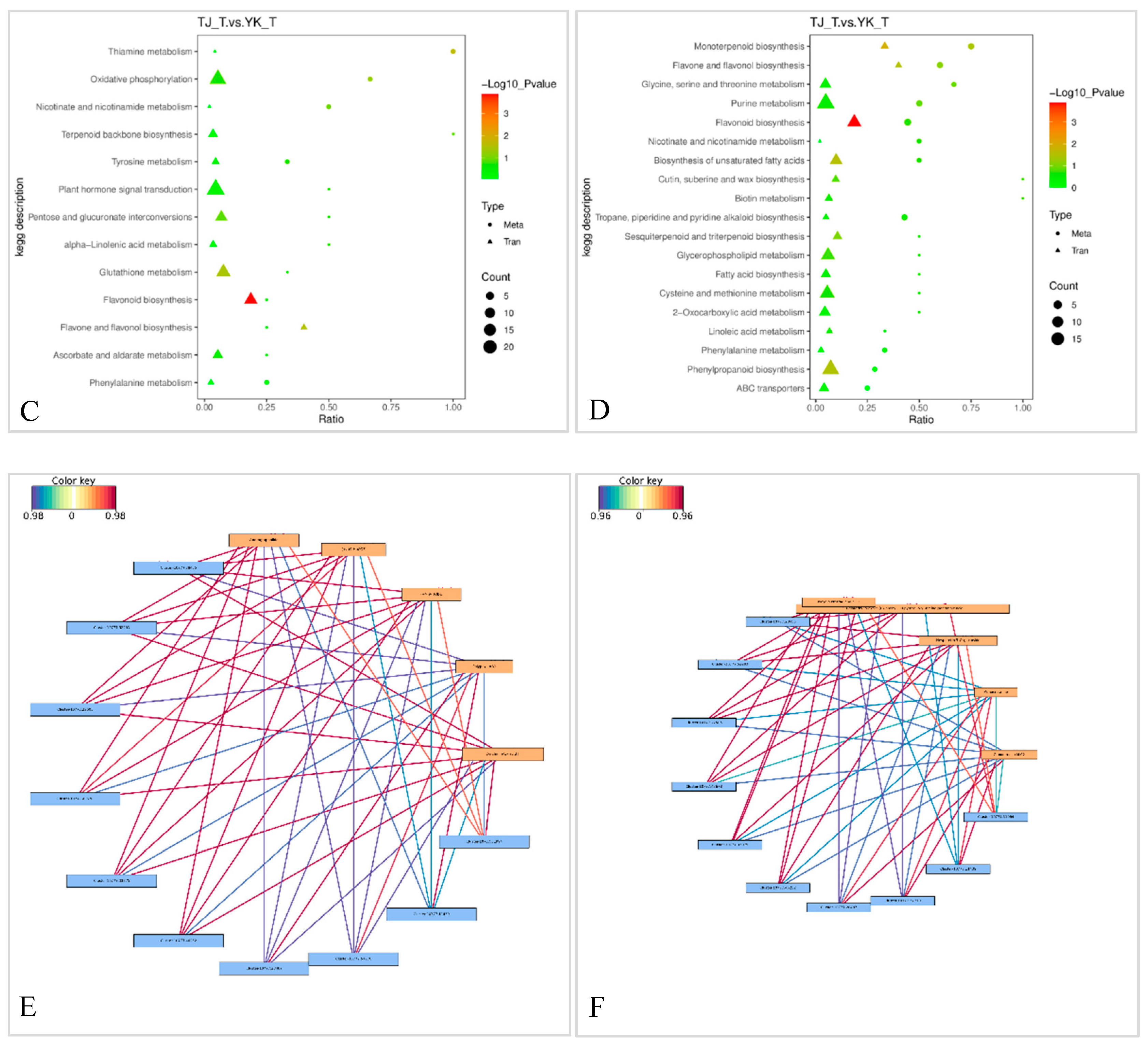

2.3.4. Transcriptome and metabolome association analysis

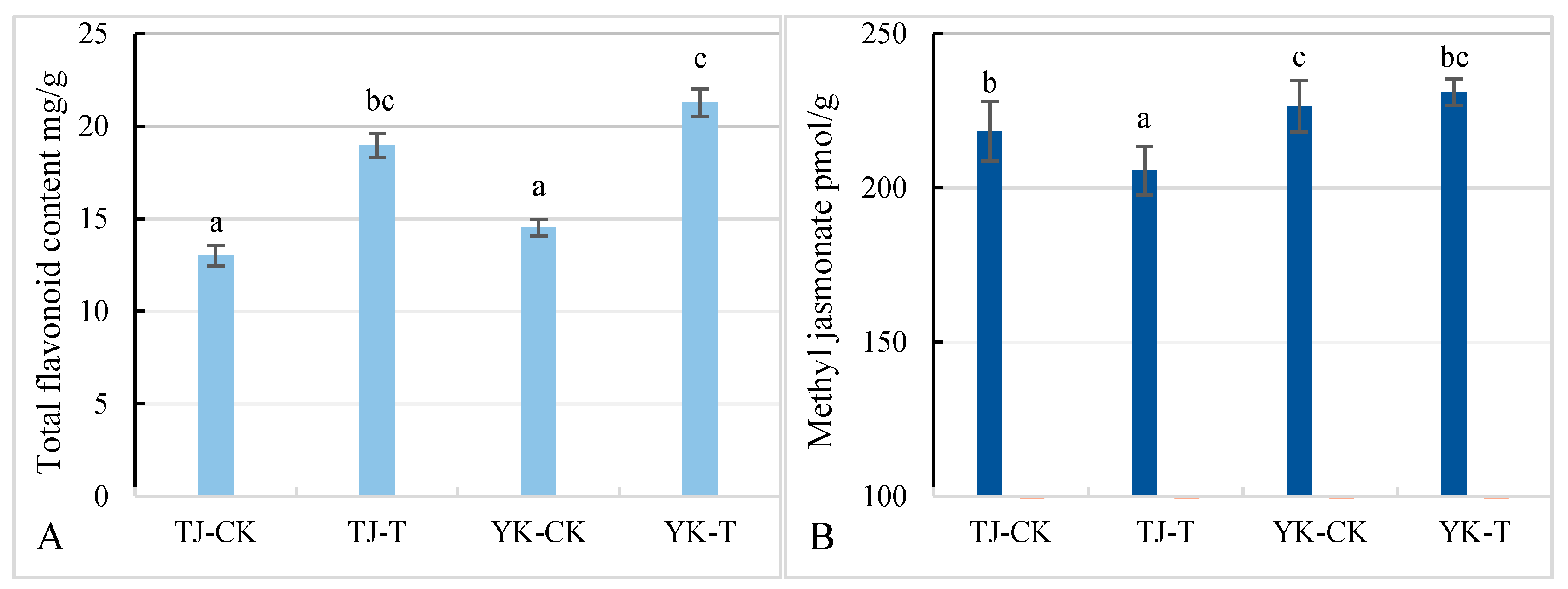

2.5. Differences in flavonoid and methyl jasmonate content in Z. armatum leaves

3. Discussion

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Plant material and growth conditions

4.2. Inoculation of Chinese pepper leaves with C. zanthoxyli

4.3. Transcriptome sequencing and data analysis

4.4. Metabolite extraction and detection

4.5. Data analysis/widely targeted metabolome analysis

4.6. Correlation analysis of transcriptomic and metabolomic data

4.8. Quantitation of total flavonoid content (TFC) and Methyl jasmonate (MeJA) in Z. armatum leaves

4.9. Statistical analysis

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, M.; Tong, S.; Ma, T.; Xi, Z.; Liu, J. Chromosome-level genome assembly of Sichuan pepper provides insights into apomixis, drought tolerance, and alkaloid biosynthesis. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2021, 21, 2533–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, S.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, J.; Li, Z.; Tian, L.; Liu, M.; Yang, T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Dai, H.; et al. Zanthoxylum-specific whole genome duplication and recent activity of transposable elements in the highly repetitive paleotetraploid Z. bungeanum genome. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.M.; Tian, C.M.; Liang, Y.M. Etc Investigation on the Diseases of Zanthoxylum bungeanum in Shaanxi and Gansu Provinces. Journal of Northwest Forestry University, 1994, 9, 39–43. Available online: https://wwwcnkicomcn/Article/CJFDTotal.

- Cao, Z.M.; Tian, C.M.; Liang, Y.M. A preliminary study on pepper rust disease. Shanxi Forestry Technology, 1989, 4, 63–65. Available online: https://xueshubaiducom/usercenter/paper/show.

- Dean, R.; Van Kan, J.A.L.; Pretorius, Z.A.; Hammond-Kosack, K.E.; Di Pietro, A.; Spanu, P.D.; Rudd, J.J.; Dickman, M.; Kahmann, R.; Ellis, J.; et al. The Top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, P.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, F.; Liang, J.; Zhou, X.; Cai, L. Applying early divergent characters in higher rank taxonomy of Melampsorineae (Basidiomycota, Pucciniales). Mycology 2022, 14, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Tang, C.; Fan, X.; He, M.; Gan, P.; Zhang, S.; Hu, Z.; Wang, X.; Yan, T.; Shu, W.; et al. Inactivation of a wheat protein kinase gene confers broad-spectrum resistance to rust fungi. Cell 2022, 185, 2961–2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Zhang, B.; Ding, J.; Wang, H.; Deng, C.; Wang, J.; Yang, Q.; Pi, Q.; Zhang, R.; Zhai, H.; et al. Cloning southern corn rust resistant gene RppK and its cognate gene AvrRppK from Puccinia polysora. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Liang, Y.; Ma, X. A study on stem rot of prickly ash. J. Northwest For. Coll. 1992, 7, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.; Ming, Y.; Cheng, D.; Zhang, H. Resistance of prickly ash to stem rot and pathogenicity differentiation of Fusarium sambucinum. J. Northwest For. Uni. 2010, 25, 115–118. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfeld, B.N.; Colle, M.; Kang, Y.; Jones, A.D.; Grumet, R. Transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses of cucumber fruit peels reveal a developmental increase in terpenoid glycosides associated with age-related resistance to Phytophthora capsici. Hortic. Res. 2017, 4, 17022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sade, D.; Shriki, O.; Cuadros-Inostroza, A.; Tohge, T.; Semel, Y.; Haviv, Y.; Willmitzer, L.; Fernie, A.R.; Czosnek, H.; Brotman, Y. Comparative metabolomics and transcriptomics of plant response to Tomato yellow leaf curl virus infection in resistant and susceptible tomato cultivars. Metabolomics 2014, 11, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Yu, D.; Wu, Z.; Wang, C.; Yu, L.; Wei, A.; Wang, D. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis and Expression of Genes Reveal the Biosynthesis and Accumulation Patterns of Key Flavonoids in Different Varieties of Zanthoxylum bungeanum Leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 13258–13268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Tang, Y.; Xia, X.; Sun, J.; Meng, J.; Shang, J.; Tao, J. Correction: Zhao et al. Integration of Transcriptome, Proteome, and Metabolome Provides Insights into How Calcium Enhances the Mechanical Strength of Herbaceous Peony Inflorescence Stems. Cells 2019, 8, 102. Cells 2022, 11, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.E.; Kim, J.-G.; Fischer, C.R.; Mehta, N.; Dufour-Schroif, C.; Wemmer, K.; Mudgett, M.B.; Sattely, E. A Pathogen-Responsive Gene Cluster for Highly Modified Fatty Acids in Tomato. Cell 2020, 180, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymański, J.; Bocobza, S.; Panda, S.; Sonawane, P.; Cárdenas, P.D.; Lashbrooke, J.; Kamble, A.; Shahaf, N.; Meir, S.; Bovy, A.; et al. Analysis of wild tomato introgression lines elucidates the genetic basis of transcriptome and metabolome variation underlying fruit traits and pathogen response. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 1111–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Ruan, Z.; Fei, Z.; Yan, J.; Tang, G. Integrated Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis Revealed That Flavonoid Biosynthesis May Dominate the Resistance of Zanthoxylum bungeanum against Stem Canker. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 6360–6378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lin, D.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, M.; Chen, Y.; Lv, B.; Li, B.; Lei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, L.; et al. Genome-edited powdery mildew resistance in wheat without growth penalties. Nature 2022, 602, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, J.L.; Horvath, D.M.; Staskawicz, B. J. Pivoting the plant immune system from dissection to deployment. Science, 2013, 341, 746–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stotz, H.U.; Mitrousia, G.K.; de Wit, P.J.; Fitt, B.D. Effector-triggered defence against apoplastic fungal pathogens. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wellings, C.; Chen, X.; Kang, Z.; Liu, T. Wheat stripe (yellow) rust caused byPuccinia striiformisf. sp. tritici. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2014, 15, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Tang, C.L.; Fan, X.; He, M.Y.; Gan, P.F.; Zhang, S.; Hu, Z.Y.; Wang, X.D.; Yan, T.; Shu, W.X.; Yu, L.G.; Zhao, J.R.; He, J.N.; Li, L.L.; Wang, J.F.; Huang, X.L.; Huang, L.L.; Zhou, J.M.; Kang, Z.S.; Wang, X.J. ; lnactivation of a wheat protein kinase gene confersbroad spectrum resistance to rust fungi. Cell, 2022, 185, 2961–2974e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, L.; Shi, H.; Chern, M.; Yu, H.; Yi, H.; He, M.; Yin, J.; Zhu, X.; Li, Y.; et al. A single transcription factor promotes both yield and immunity in rice. Science 2018, 361, 1026–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Bradeen, J.M.; Naess, S.K.; Raasch, J.A.; Haberlach, G.T.; Wielgus, S.M.; Liu, J.; Kuang, H.; Austin-Phillips, S.; Buell, C.B.; Helgeson, J.P.; Jiang, J. Gene RB from Solanum bulbocastanum confers broad spectrum resistance against potato late blight pathogen Phytophthora infestans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003, 100, 9128–9133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, B.; Zheng, W.; Wang, L.; Cai, X.; Yang, J.; Song, R.; Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, J.; et al. Recognition of glycoside hydrolase 12 proteins by the immune receptor RXEG1 confers Fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 769–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Mu, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Yu, H.; Huang, T.; He, Y.; Dai, S.; Meng, X. Multilayered synergistic regulation of phytoalexin biosynthesis by ethylene, jasmonate, and MAPK signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 3066–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.Q.; Lin, H.X. Contribution of phenylpropanoid metabolism to plant development and plant–environment interactions. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 180–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobiecki, M.; Kachlicki, P. Isolation and Identification of flavonoids. In the Science of Flavonoid; E. Grotewold, ed. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2006, 47-70. [CrossRef]

- Hichri, I.; Barrieu, F.; Bogs, J.; Kappel, C.; Delrot, S.; Lauvergeat, V. Recent advances in the transcriptional regulation of the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 2465–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohge, T.; Watanabe, M.; Hoefgen, R.; Fernie, A.R. The evolution of phenylpropanoid metabolism in the green lineage. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2012, 48, 123–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkel-Shirley, B. Flavonoid Biosynthesis. A Colorful Model for Genetics, Biochemistry, Cell Biology, and Biotechnology. Plant Physiol. 2001, 126, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Doseff, A.I.; Grotewold, E. Flavones: From Biosynthesis to Health Benefits. Plants 2016, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, T.; Takahashi, S.; Waki, T. Formation of Flavonoid Metabolons: Functional Significance of Protein-Protein Interactions and Impact on Flavonoid Chemodiversity. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Deng, Y.; Xi, P.; Yu, G.; Wang, Q.; Zeng, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Gao, L. Fulvic acid-induced disease resistance to Botrytis cinerea in table grapes may be mediated by regulating phenylpropanoid metabolism. Food Chem. 2019, 286, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shadle, G.L.; Wesley, S.; Korth, K.L.; Chen, F.; Lamb, C.; Dixon, R.A. Phenylpropanoid compounds and disease resistance in transgenic tobacco with altered expression of l -phenylalanine ammonia-lyase. Phytochemistry 2003, 64, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zhou, D.; Peng, J.; Pan, L.; Tu, K. Hot Air Treatment Induces Disease Resistance through Activating the Phenylpropanoid Metabolism in Cherry Tomato Fruit. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 8003–8010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; He, Q.; Zhang, F.; Yu, J.; Li, C.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Q.; Su, B.; Mei, L.; et al. Melatonin enhances cotton immunity to Verticillium wilt via manipulating lignin and gossypol biosynthesis. Plant J. 2019, 100, 784–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, S. Comparative analysis of powdery mildew resistant and susceptible cultivated cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) varieties to reveal the metabolic responses to Sphaerotheca fuliginea infection. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, U.S.; Uppalapati, S.R.; Gallego-Giraldo, L.; Ishiga, Y.; Dixon, R.A.; Mysore, K.S. Metabolic flux towards the (iso)flavonoid pathway in lignin modified alfalfa lines induces resistance againstFusarium oxysporumf. sp. medicaginis. Plant, Cell Environ. 2017, 41, 1997–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wu, P.; Cao, Y.; Yang, B.; Liu, L.; Chen, J.; Zhuo, R.; Yao, X. Overexpression of dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (CoDFR) boosts flavonoid production involved in the anthracnose resistance. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1038467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenc-Kukuła, K.; Zuk, M.; Kulma, A.; Czemplik, M.; Kostyn, K.; Skala, J.; Starzycki, M.; Szopa, J. Engineering flax with increased flavonoid content and thus Fusarium resistance. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2007, 70, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treutter, D. Significance of flavonoids in plant resistance: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2006, 4, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J. Lipids, Lipases, and Lipid-Modifying Enzymes in Plant Disease Resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2005, 43, 229–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reina-Pinto, J.J.; Yephremov, A. Surface lipids and plant defenses. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2009, 47, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossmo, K.; Harries, K. Fatty acid-derived signals in plant defense. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2009, 47, 153–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Farmer, E.; Alméras, E.; Krishnamurthy, V. Jasmonates and related oxylipins in plant responses to pathogenesis and herbivory. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2003, 6, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.Q.; Dong, X. Systemic acquired resistance: turming local infection into global defense. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 839–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.-M.; Zhu, S.; Kachroo, P.; Kachroo, A. Signal regulators of systemic acquired resistance. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 228–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Na; Liu, X. X.; Chen, X.S.; Wu, S.J. Identifying Genes Responsive to Jasmonates in Apple Based on Transcriptome Analysis. Chinese Bulletin of Botany, 2019, 54, 733–743. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, C.; Lei, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, S.; Yang, C.; Zhu, X.; Guo, H.; Zhang, F.; Peng, M.; Zhang, M.; et al. Author Correction: Selection of a subspecies-specific diterpene gene cluster implicated in rice disease resistance. Nat. Plants 2020, 7, 100–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Zou, G.; Wang, L.; Li, X. Two responses to MeJA induction of R2R3-MYB transcription factors regulate flavonoid accumulation in Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0236565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.-H.; Liao, Y.-C.; Lv, F.-F.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, P.-W.; Gao, Z.-H.; Hu, K.-P.; Sui, C.; Jin, Y.; Wei, J.-H. Transcription Factor AsMYC2 Controls the Jasmonate-Responsive Expression of ASS1 Regulating Sesquiterpene Biosynthesis in Aquilaria sinensis (Lour.) Gilg. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017, 58, 1924–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Li, Y.; Gao, F.; Jin, W.; Li, S.; Kimani, S.; Yang, S.; Bao, T.; Gao, X.; Wang, L. MYB21 interacts with MYC2 to control the expression of terpene synthase genes in flowers of Freesia hybrida and Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 4140–4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patra, B.; Pattanaik, S.; Schluttenhofer, C.; Yuan, L. A network of jasmonate-responsive bHLH factors modulate monoterpenoid indole alkaloid biosynthesis inCatharanthus roseus. New Phytol. 2017, 217, 1566–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, J.; Wang, B.; He, G.; Wang, Y.; Tang, X.; Wang, S.; Ma, Y.; Fu, C.; Chai, G.; Zhou, G. Metabolomics Integrated with Transcriptomics Reveals Redirection of the Phenylpropanoids Metabolic Flux in Ginkgo biloba. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 3284–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, S.; Yuan, Y. Lignin Involvement in Programmed Changes in Peach-Fruit Texture Indicated by Metabolite and Transcriptome Analyses. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 12627–12640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Wang, B.; He, G.; Wang, Y.; Tang, X.; Wang, S.; Ma, Y.; Fu, C.; Chai, G.; Zhou, G. Metabolomics Integrated with Transcriptomics Reveals Redirection of the Phenylpropanoids Metabolic Flux in Ginkgo biloba. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 3284–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhu, T.; Han, S.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Lin, T.; Qiao, T. Changes in the Histology of Walnut (Juglans regia L.) Infected with Phomopsis capsici and Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Yu, D.; Wu, Z.; Wang, C.; Yu, L.; Wei, A.; Wang, D. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis and Expression of Genes Reveal the Biosynthesis and Accumulation Patterns of Key Flavonoids in Different Varieties of Zanthoxylum bungeanum Leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 13258–13268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhou, P.; Gui, C.; Da, G.; Gong, L.; Zhang, X. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Ampelopsis megalophylla for Identifying Genes Involved in Flavonoid Biosynthesis and Accumulation during Different Seasons. Molecules 2019, 24, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Xiang, D.-B.; Yan, L.; Song, Y.; Zhao, G.; Wang, Y.-H.; Zhang, B.-L. Changes in seed growth, levels and distribution of flavonoids during tartary buckwheat seed development. Plant Prod. Sci. 2016, 19, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Raw reads | Clean reads | Error rate | Q20 (%) | Q30 (%) | GC content (%) | Total map |

| YK-CK1 | 21,440,315 | 20,913,184 | 0.03 | 97.27 | 92.57 | 44.83 | 31,488,252 (75.28%) |

| YK-CK2 | 23,545,476 | 22,713,650 | 0.03 | 97.54 | 93.12 | 44.24 | 33,838,906 (74.49%) |

| YK-CK3 | 22,641,971 | 22,074,057 | 0.03 | 97.32 | 92.62 | 44.5 | 32,675,810 (74.01%) |

| YK-T1 | 21,707,455 | 21,218,135 | 0.03 | 97.42 | 92.88 | 43.8 | 31,019,402 (73.10%) |

| YK-T2 | 21,024,152 | 20,494,901 | 0.03 | 97.26 | 92.52 | 44.2 | 30,387,514 (74.13%) |

| YK-T3 | 20,843,912 | 20,316,601 | 0.03 | 96.82 | 91.61 | 45.42 | 30,567,864 (75.23%) |

| TJ-CK1 | 20,666,347 | 20,205,862 | 0.03 | 96.88 | 91.72 | 43.78 | 29,411,490 (72.78%) |

| TJ-CK2 | 21,206,648 | 20,714,680 | 0.03 | 97.23 | 92.43 | 44.7 | 30,755,186 (74.24%) |

| TJ-CK3 | 22,574,829 | 22,034,849 | 0.03 | 97.1 | 92.2 | 45.06 | 32,950,058 (74.77%) |

| TJ-T1 | 22,062,869 | 21,543,733 | 0.03 | 97.09 | 92.19 | 43.99 | 31,528,218 (73.17%) |

| TJ-T2 | 22,507,430 | 21,693,488 | 0.03 | 97.21 | 92.43 | 43.74 | 32,443,130 (74.78%) |

| TJ-T3 | 22,944,166 | 22,082,650 | 0.03 | 97.47 | 92.96 | 43.84 | 33,163,596 (75.09%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).