Submitted:

14 May 2025

Posted:

14 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

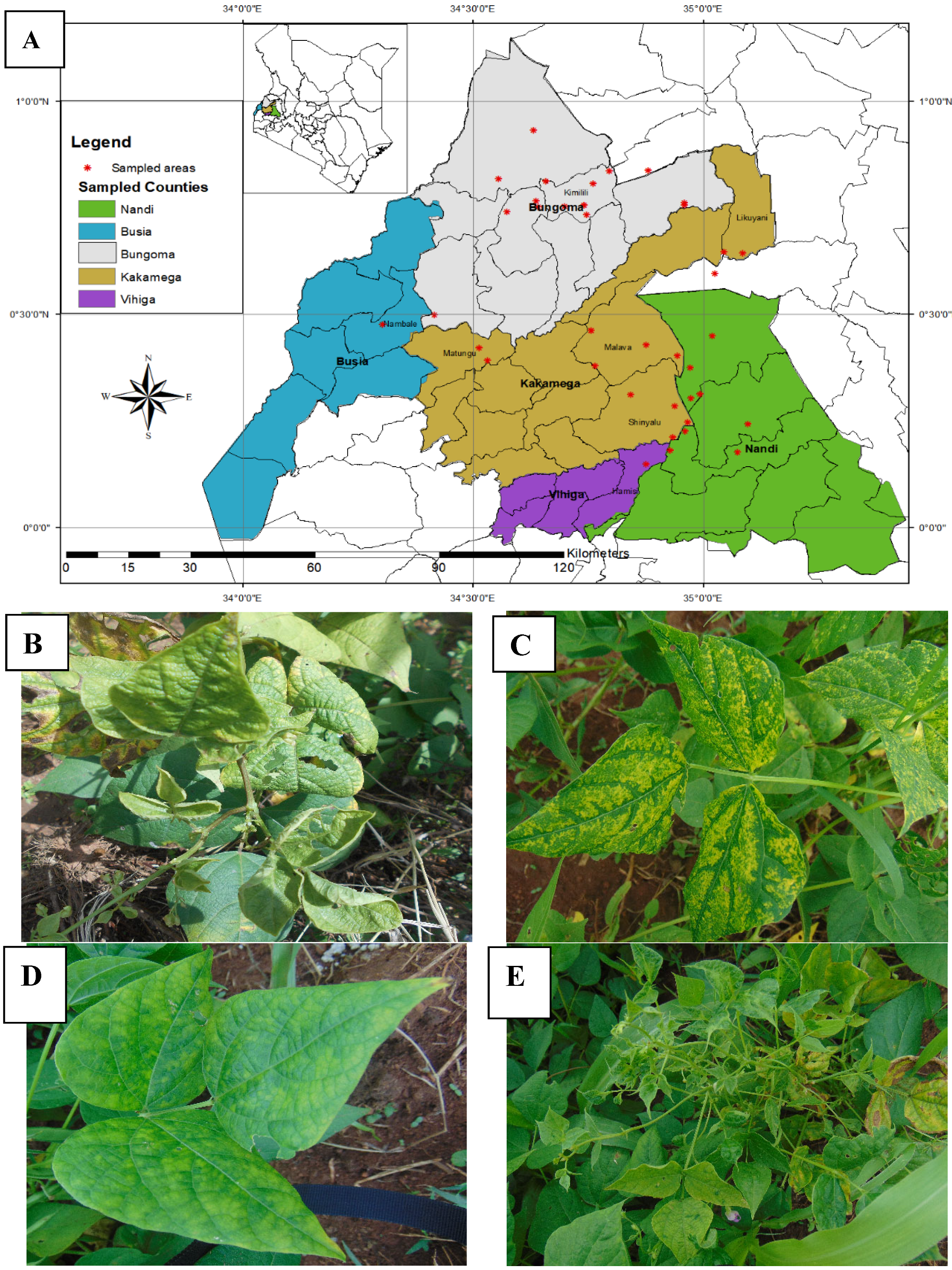

2. Research Methods

3. RNA Extraction

4. Library Construction, Quality Control & Sequencing

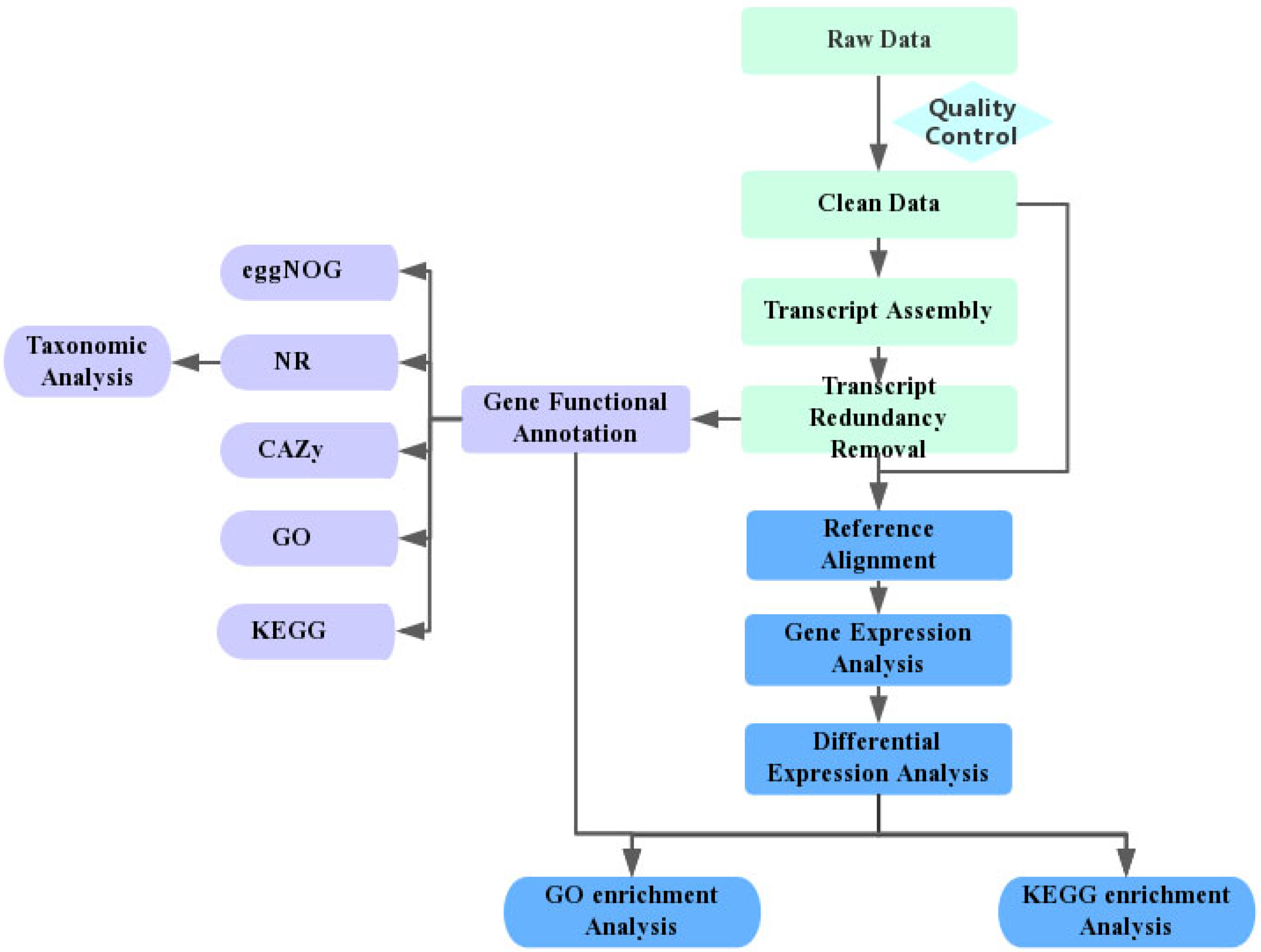

5. Data Quality Control

6. Transcriptome Assembly and Analysis

7. Data Availability and Accession

8. Results

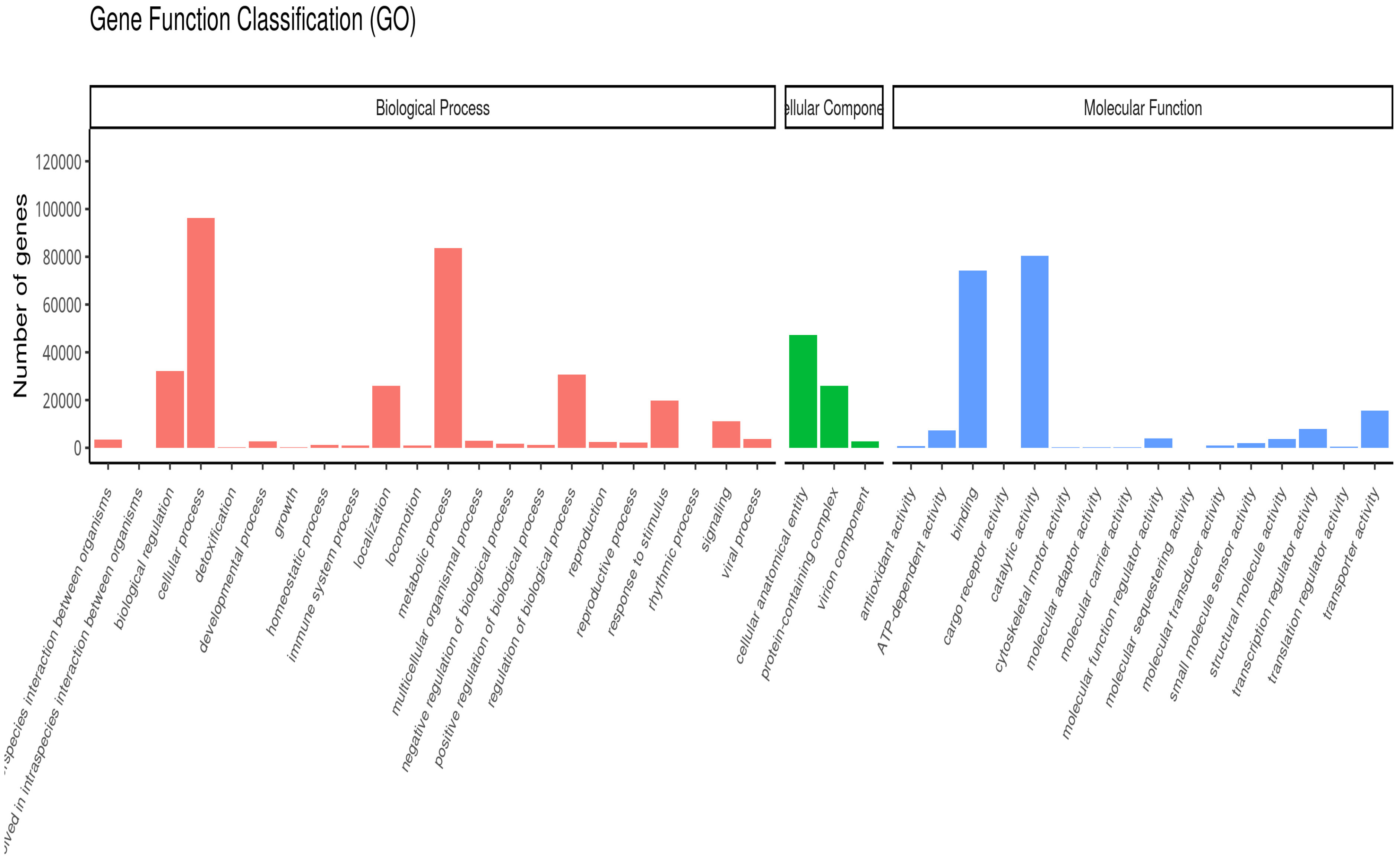

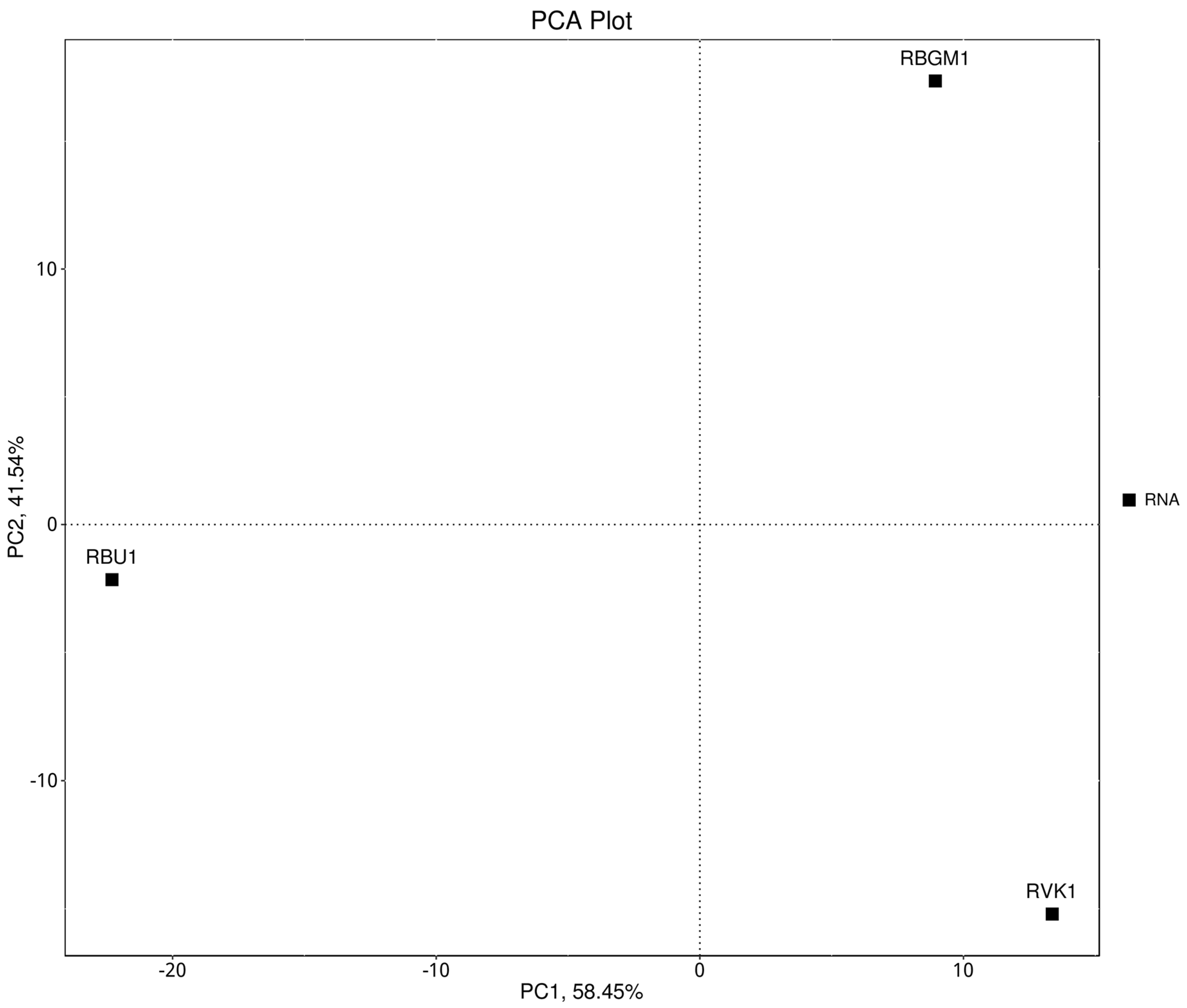

8.1. Quality Check (QC) of the Transcriptome

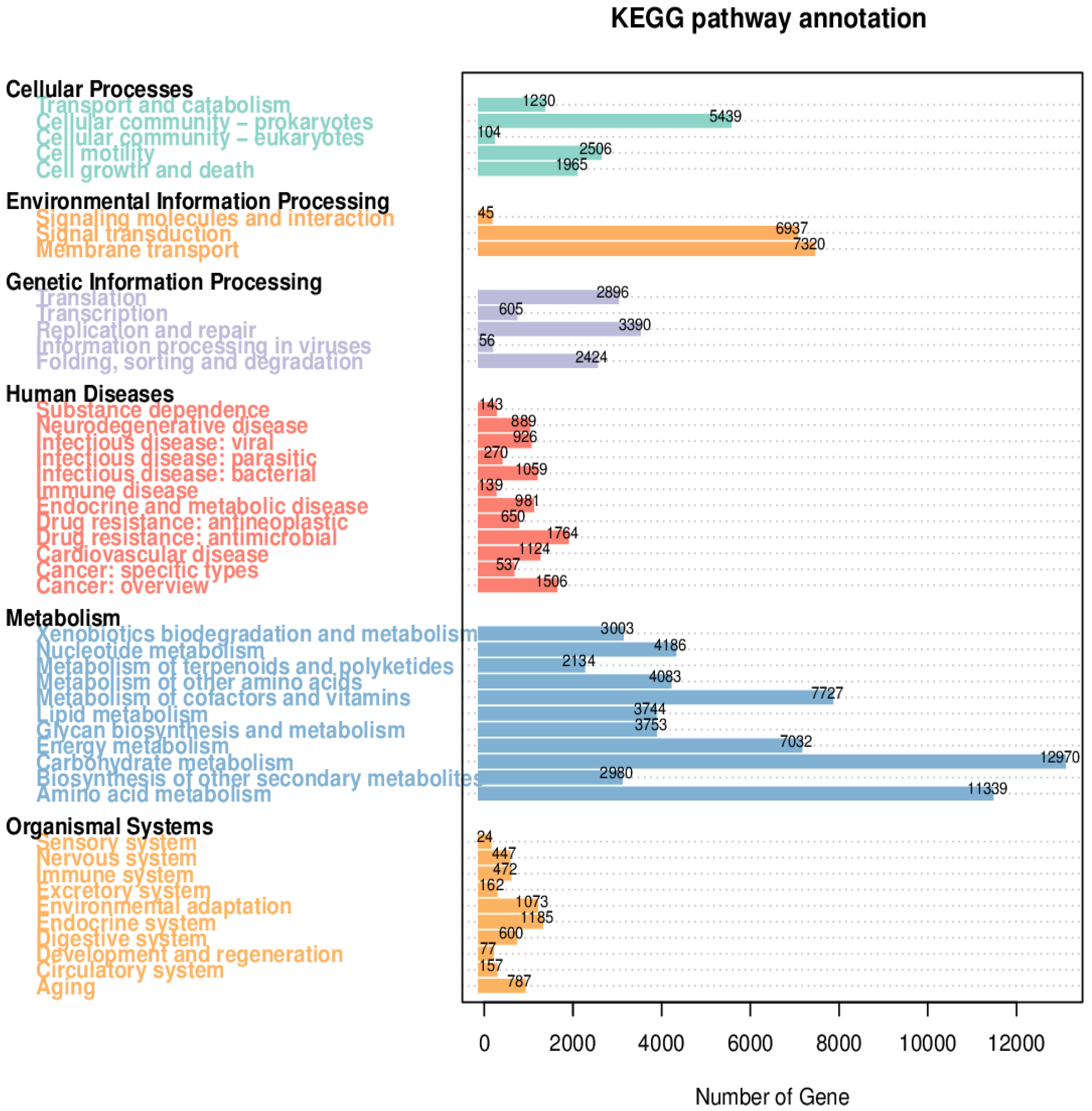

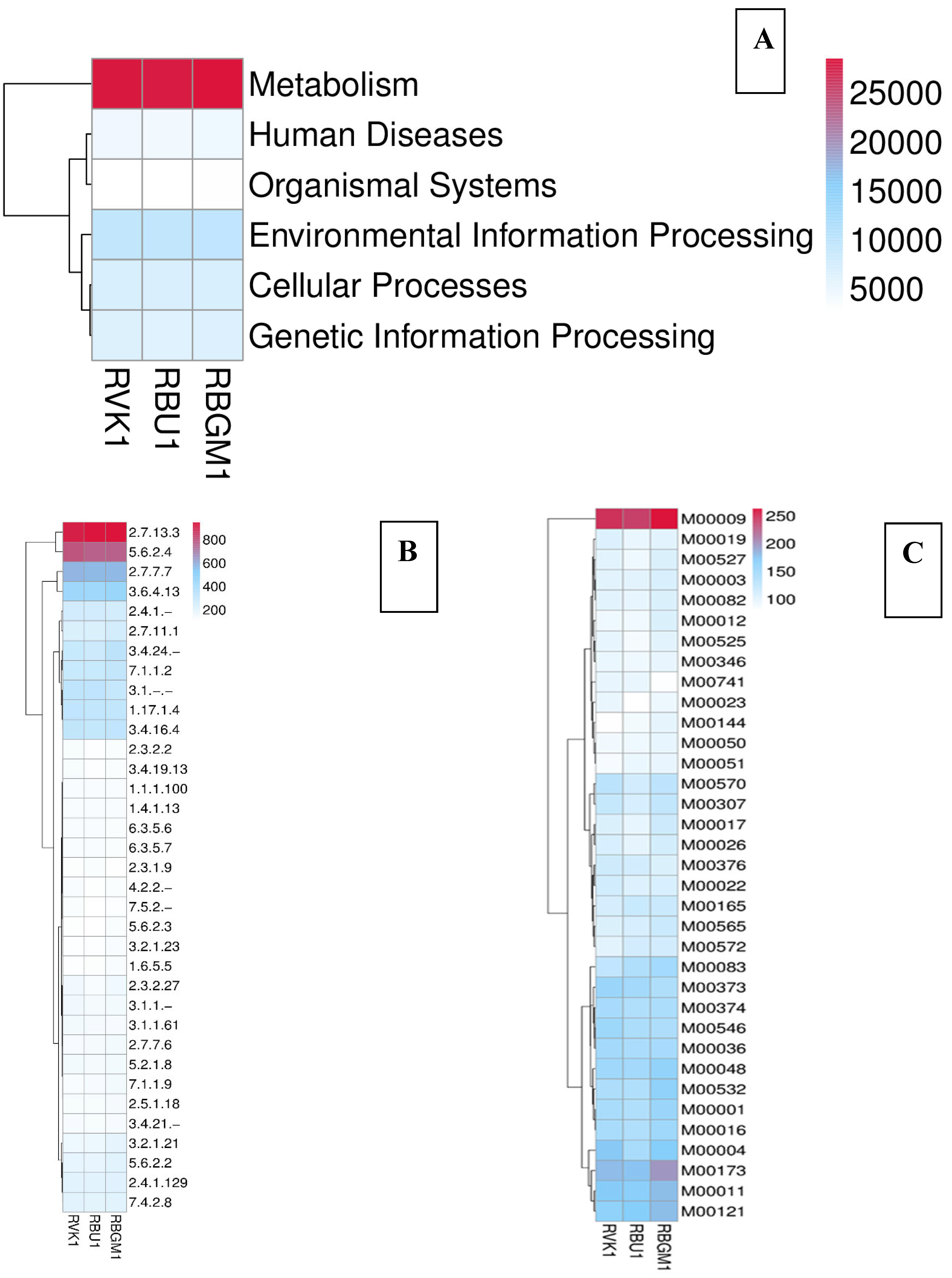

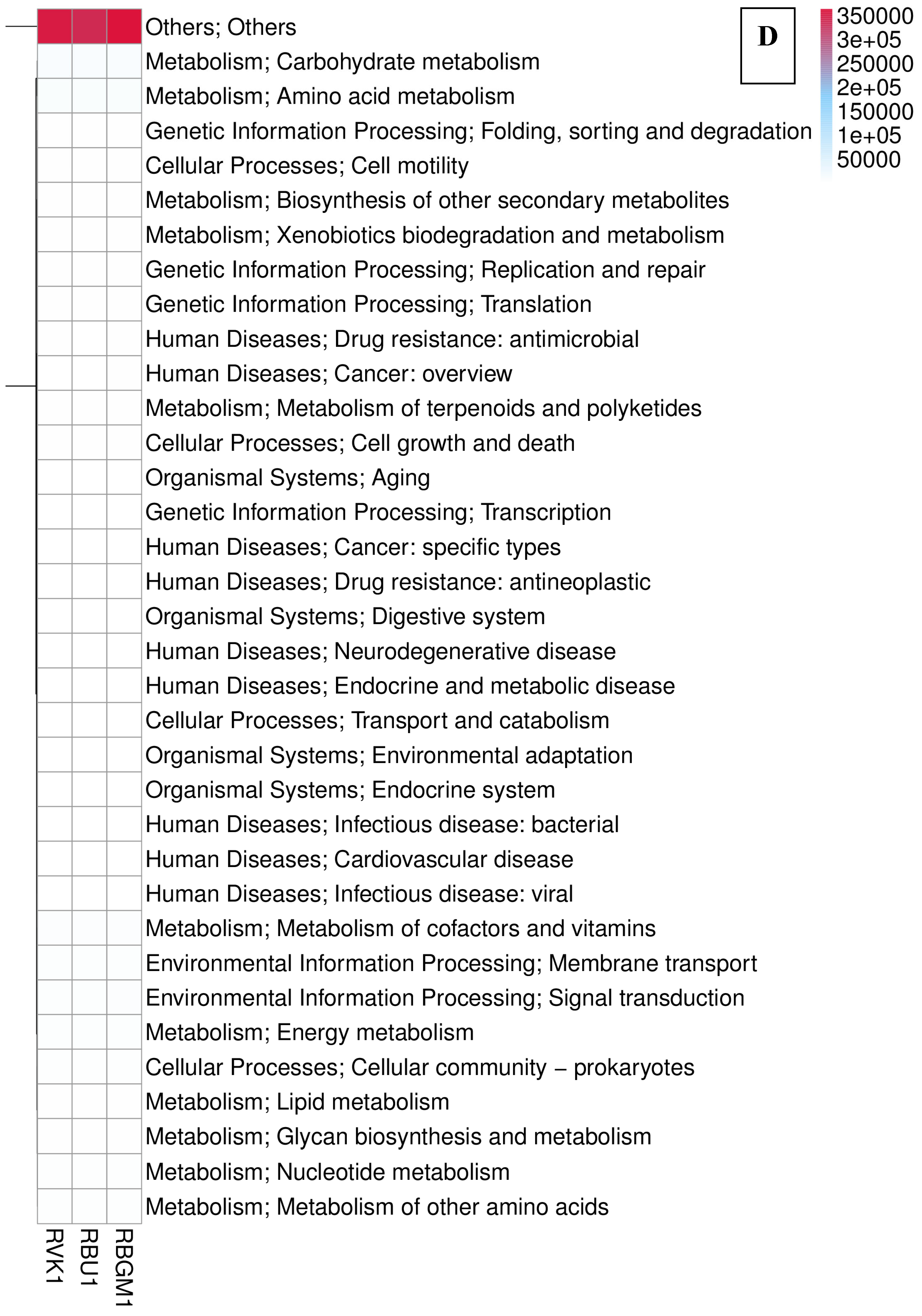

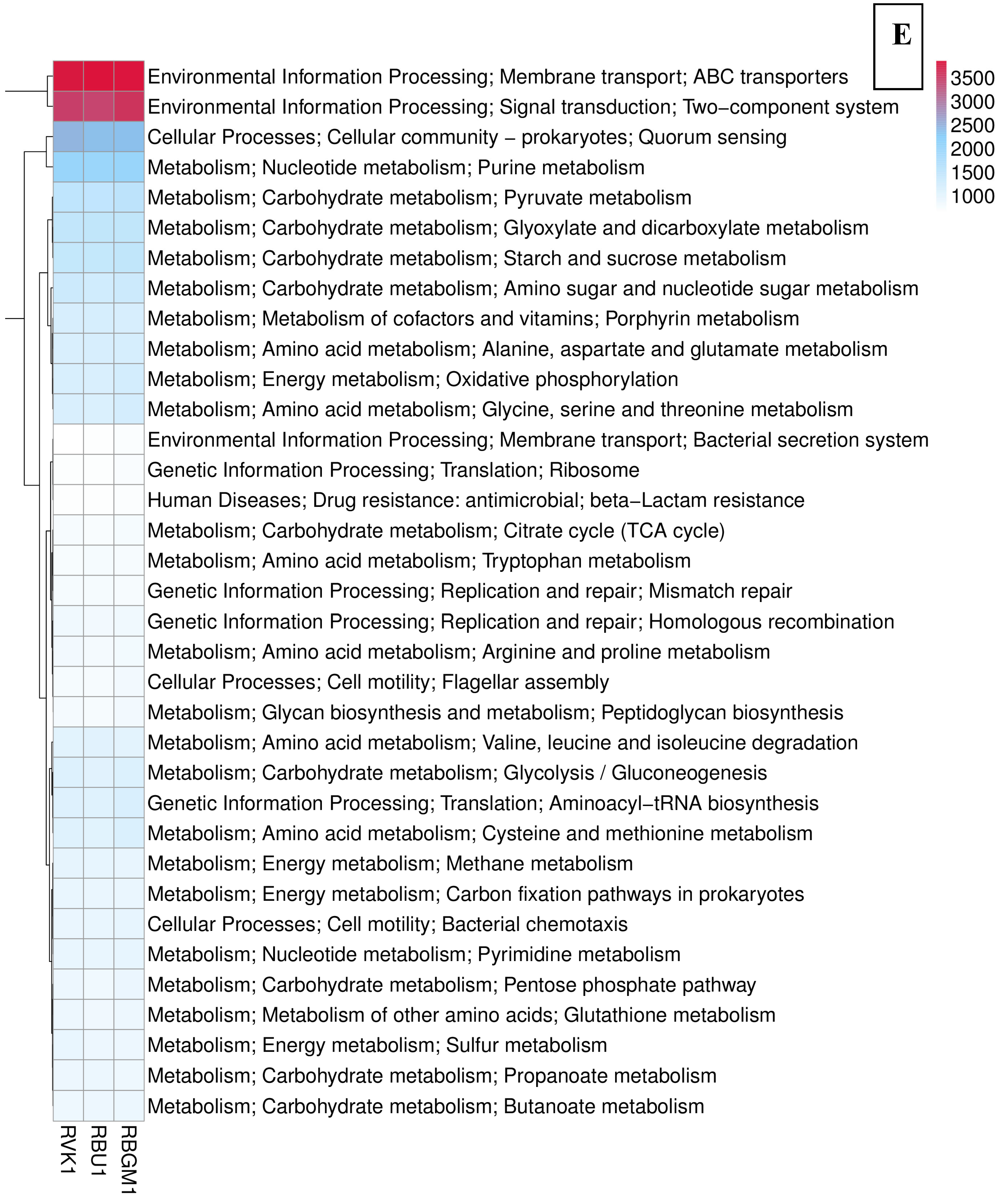

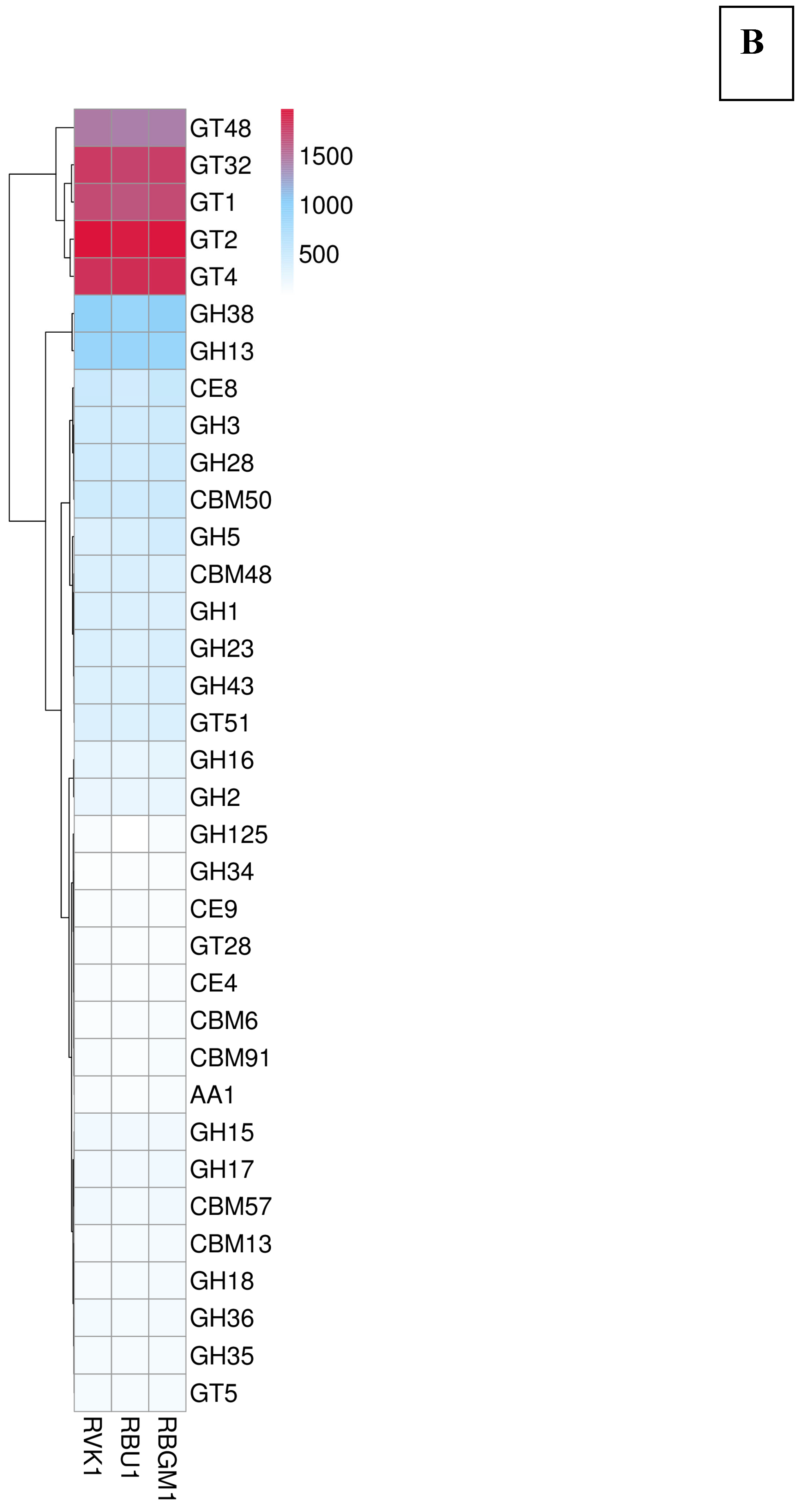

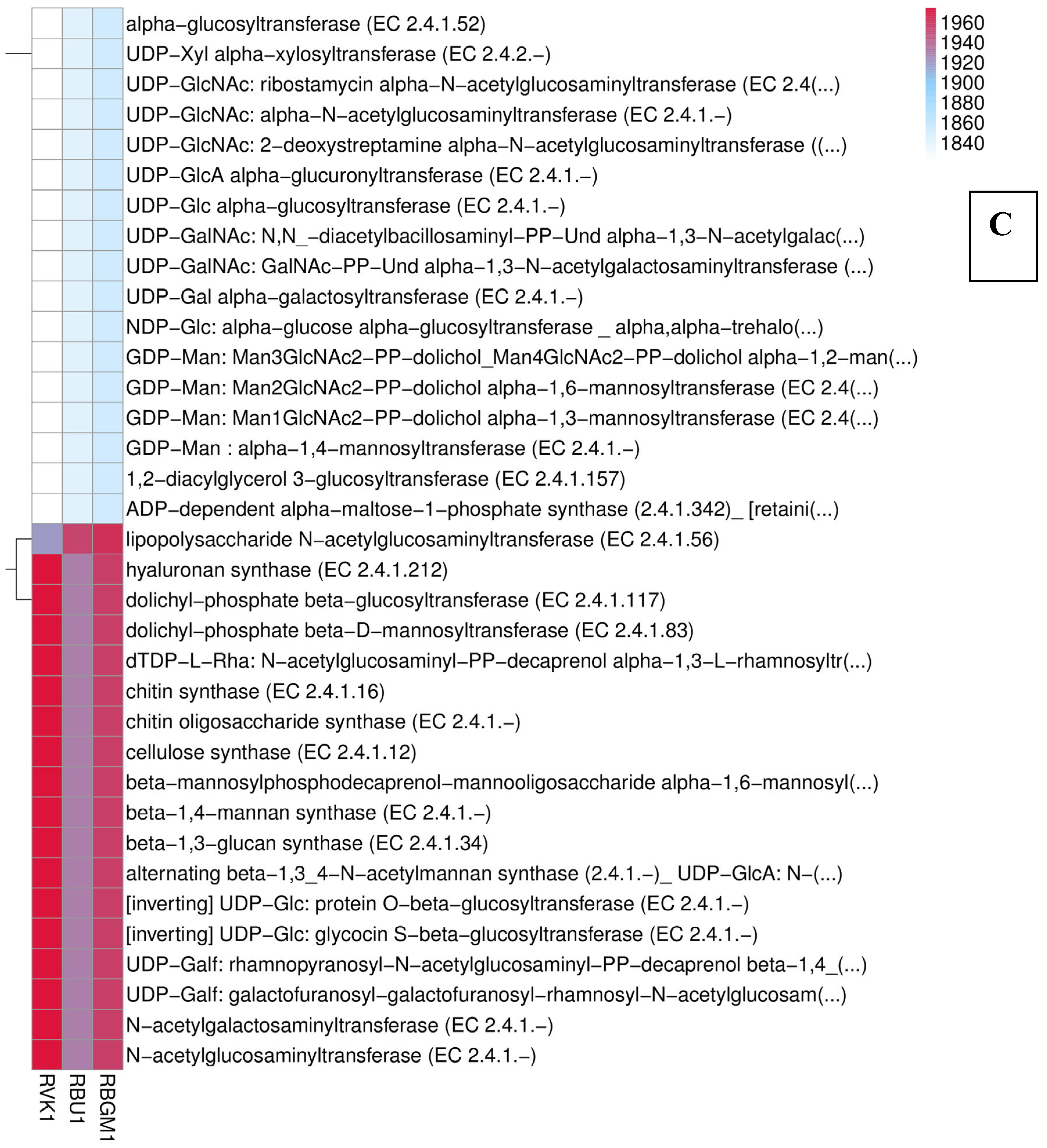

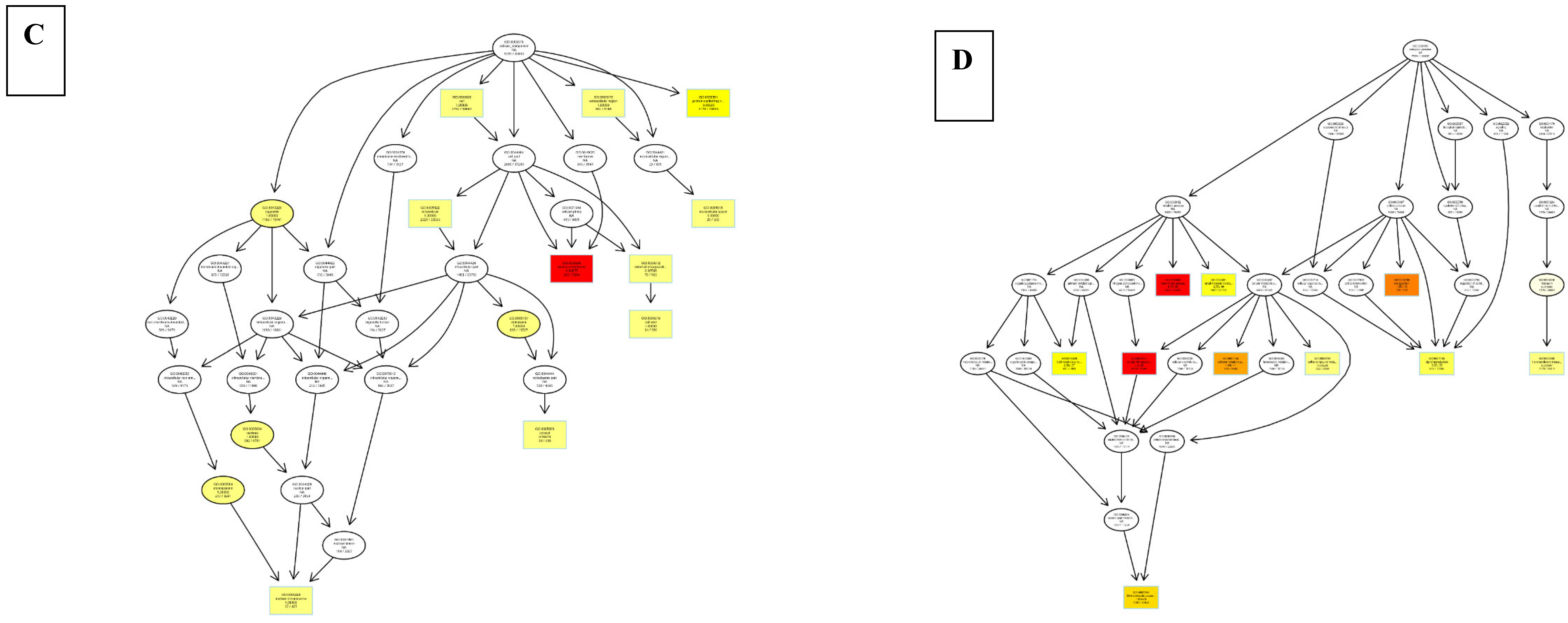

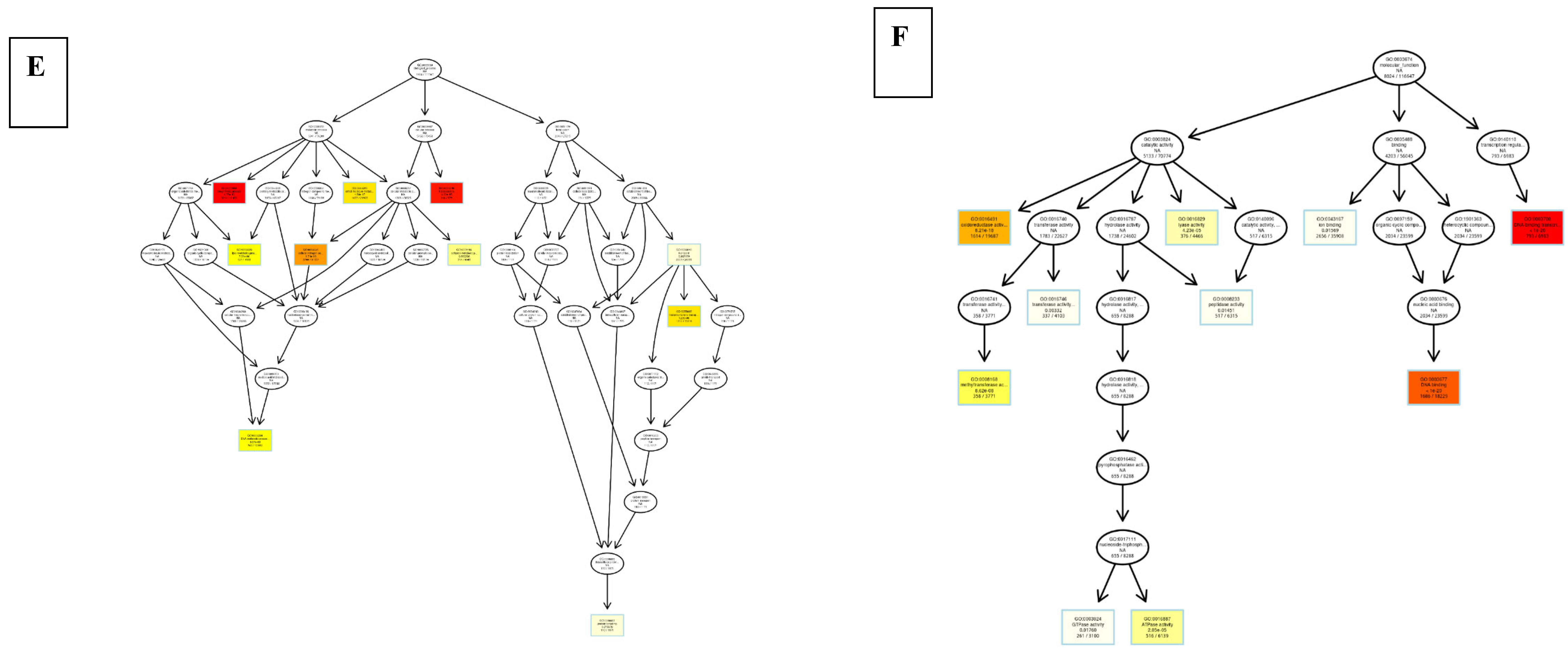

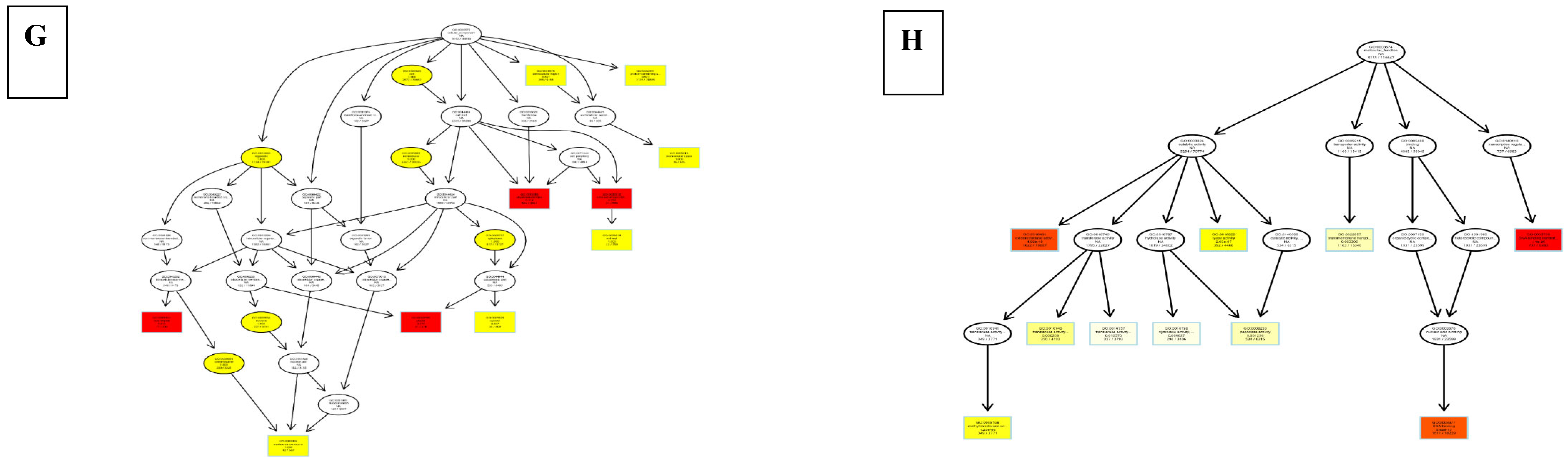

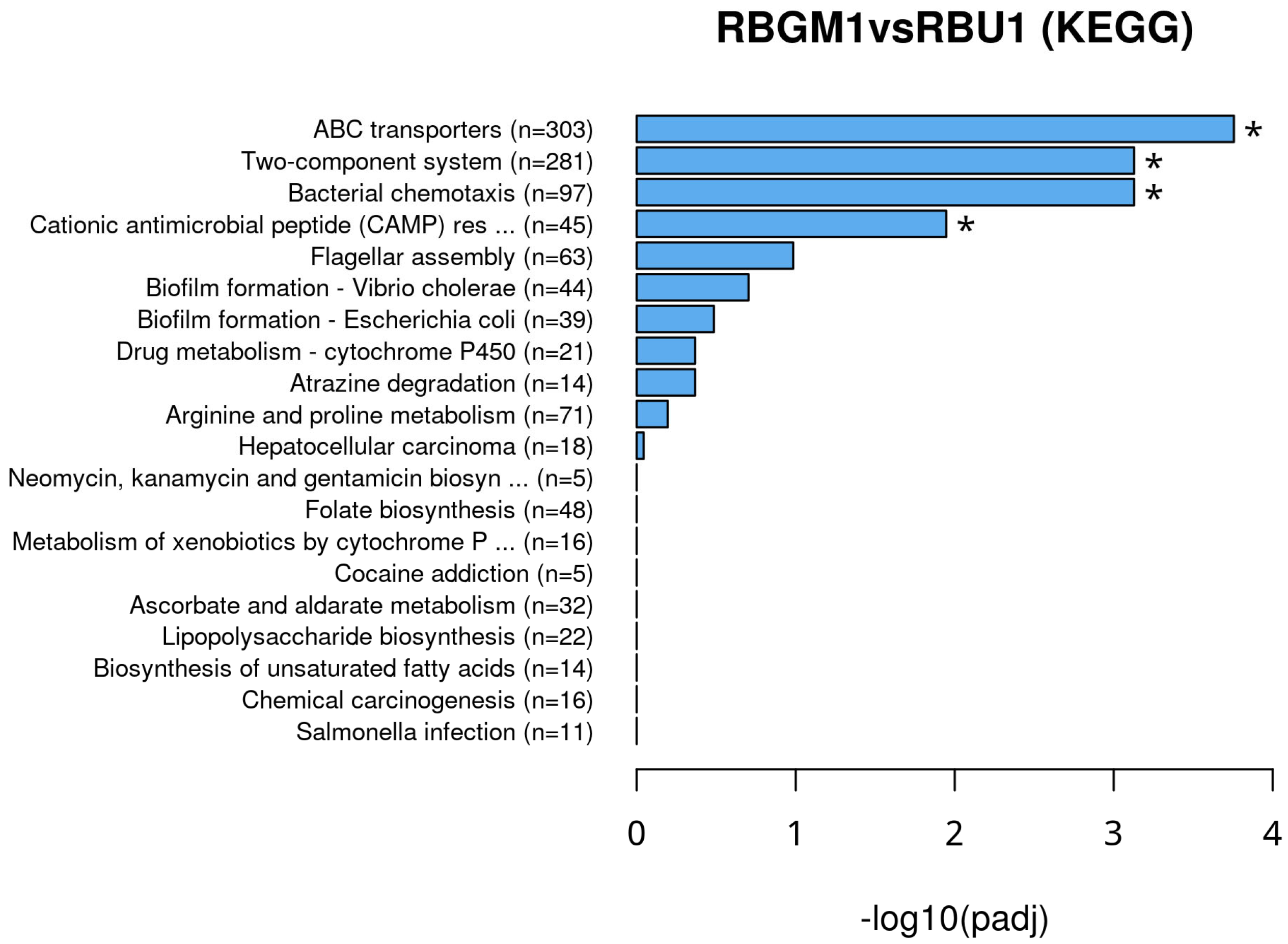

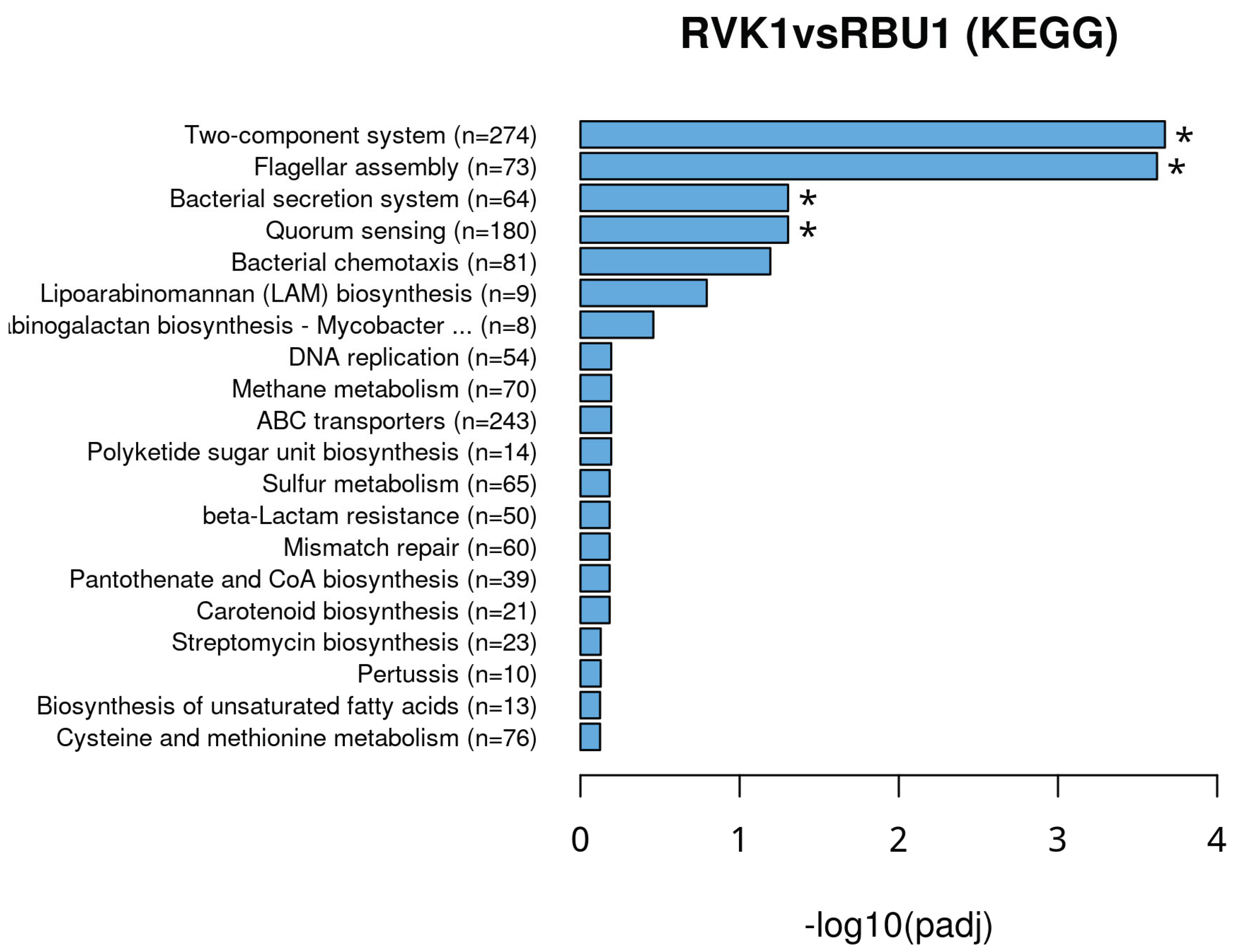

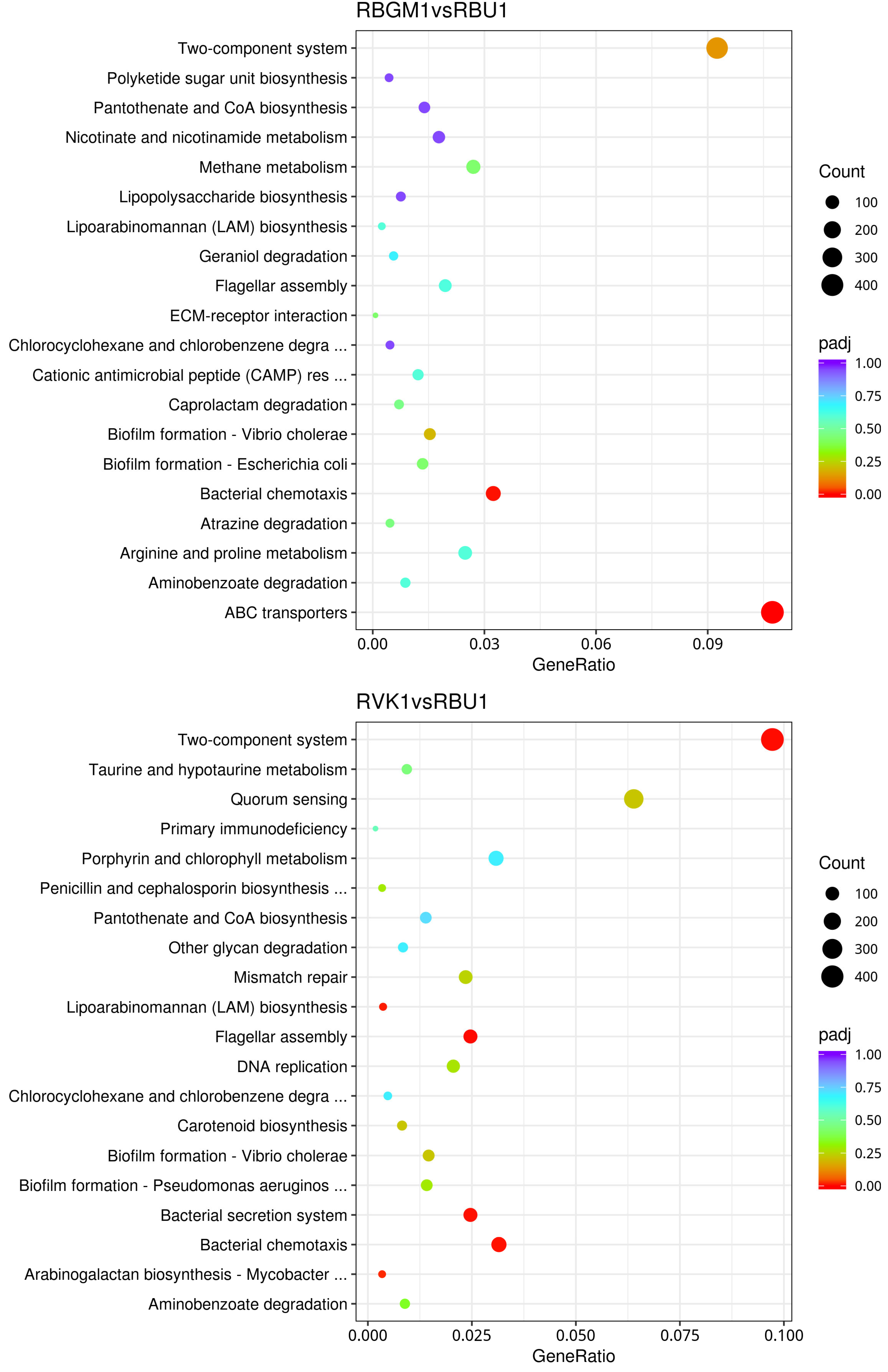

8.2. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)

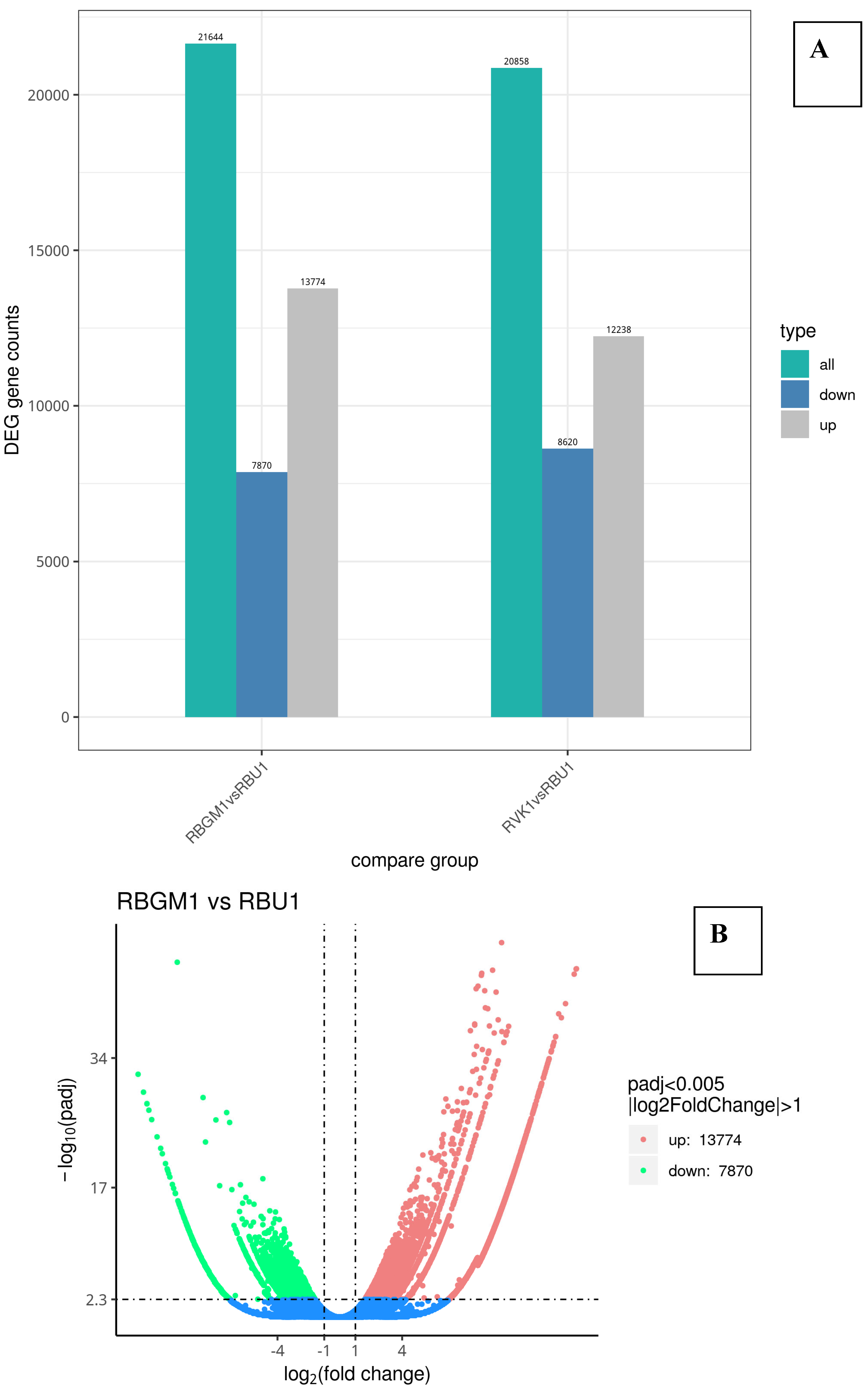

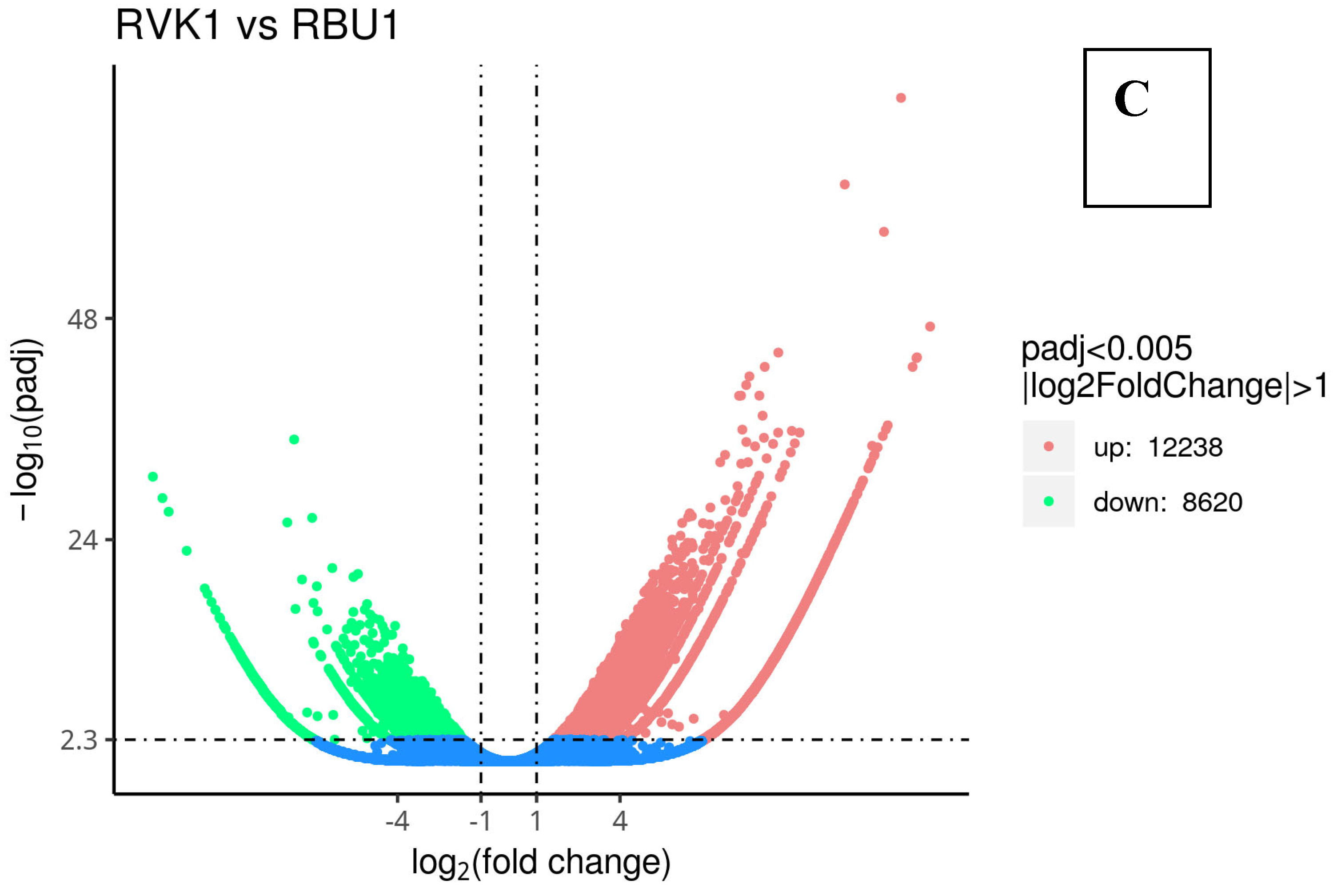

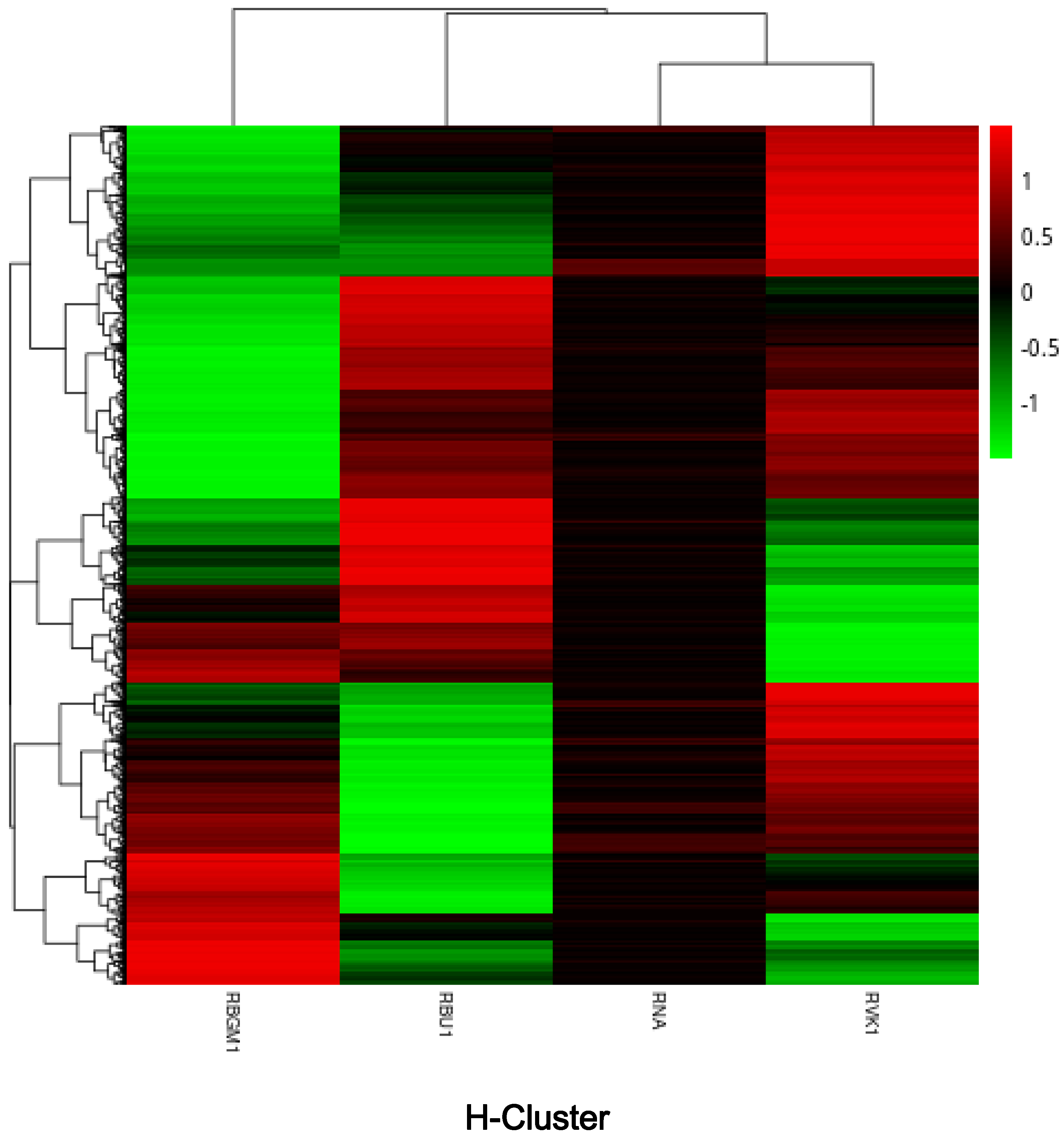

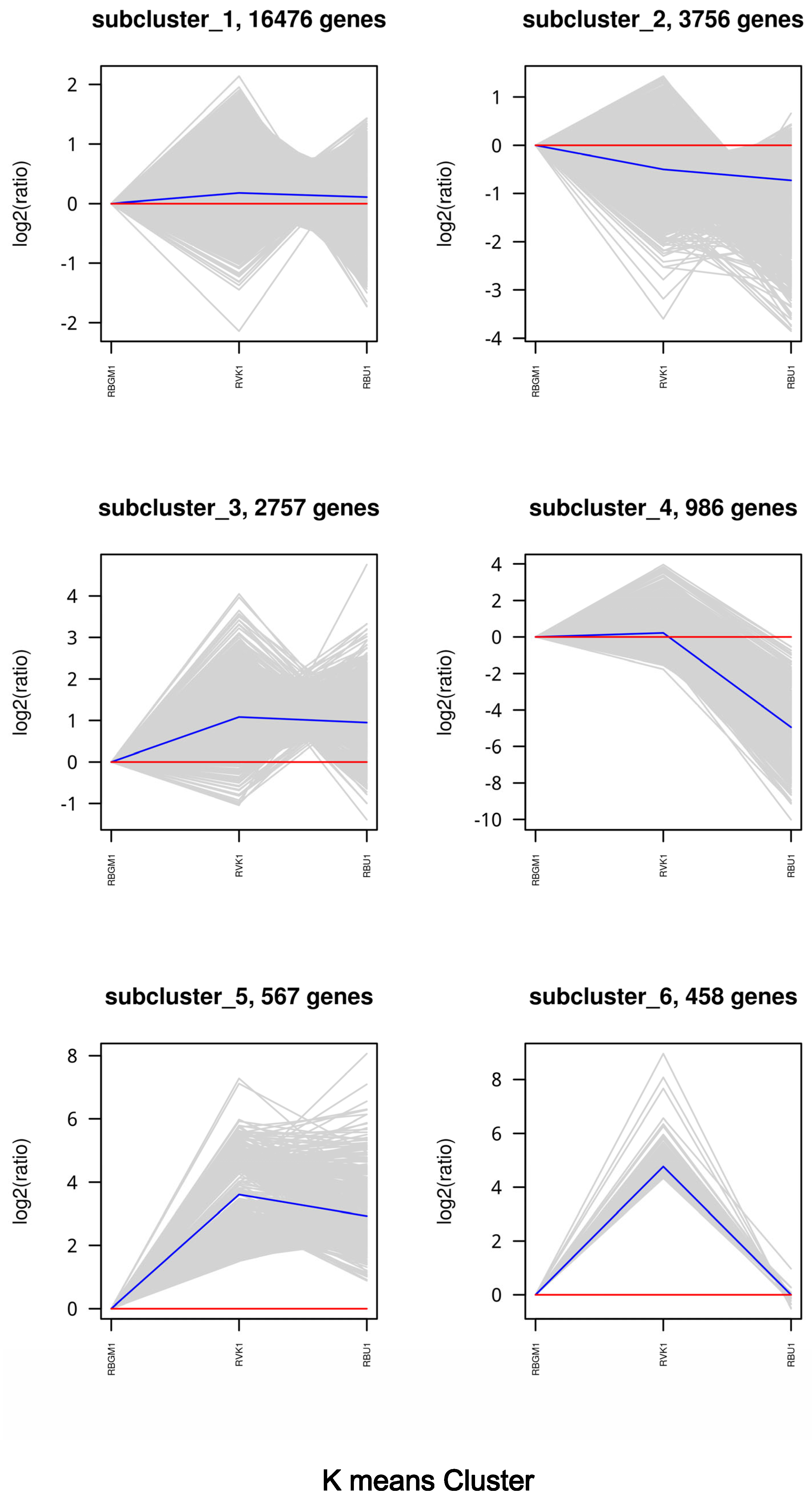

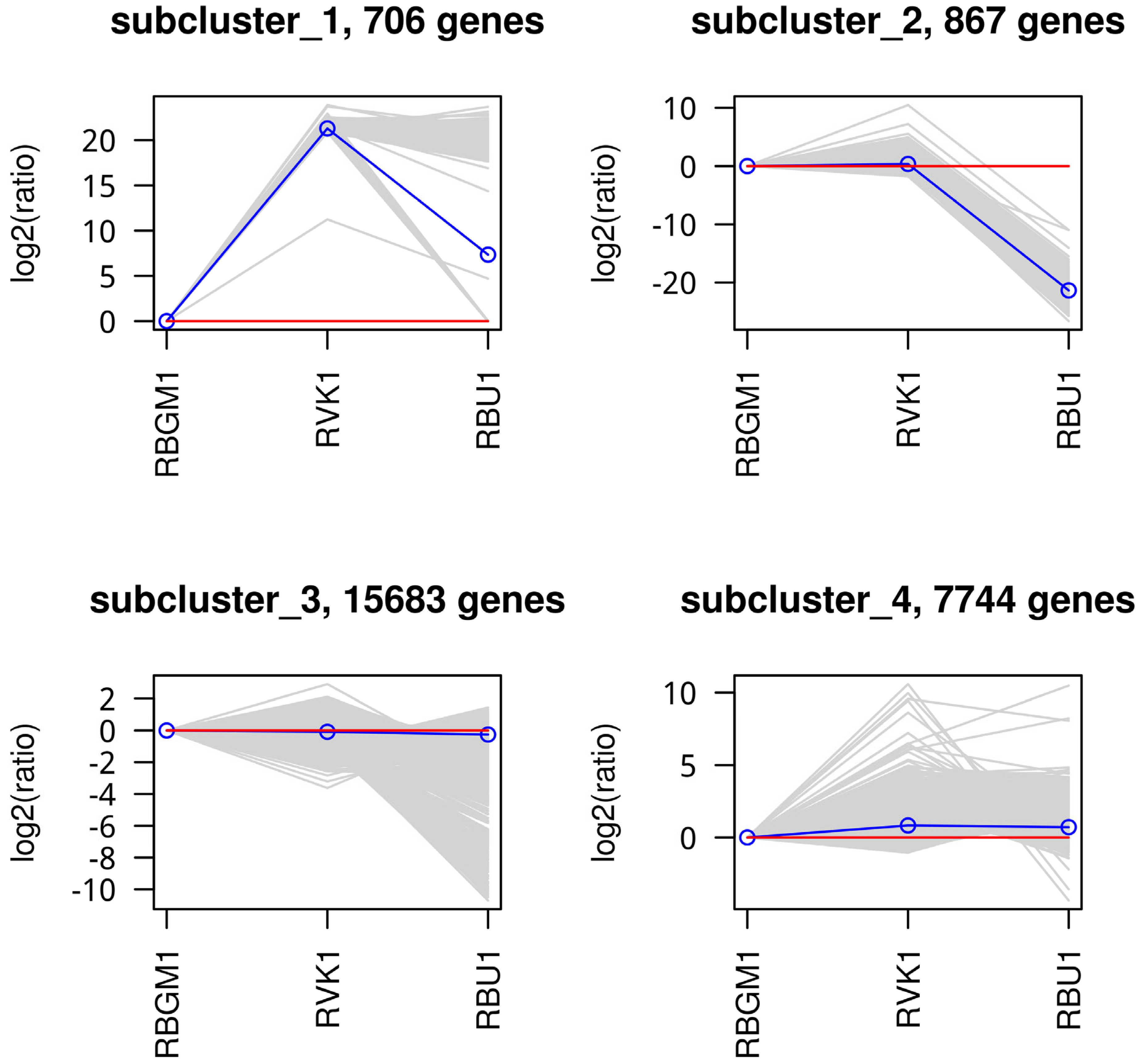

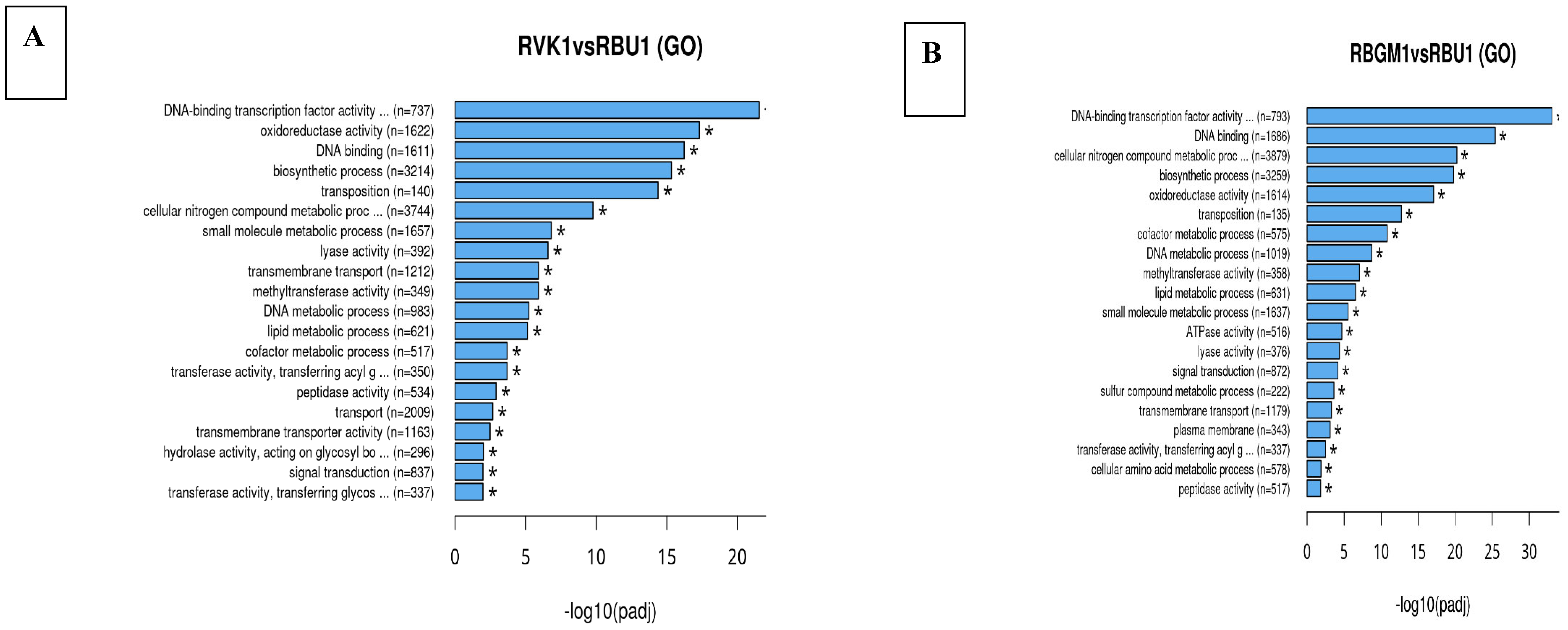

8.3. Differentially Expressed Genes

9. Discussion

10. Conclusions

11. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdel-Hameed, A. A. , Liao, W., Prasad, K. V., & Reddy, A. S. CAMTAs, a family of calmodulin-binding transcription factors, are versatile regulators of biotic and abiotic stress responses in plants. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 2024, 43, 171–210. [Google Scholar]

- Abulfaraj, A. A. Abulfaraj, A. A., Shami, A. Y., Alotaibi, N. M., Alomran, M. M., Aloufi, A. S., Al-Andal, A., AlHamdan, N. R., Alshehrei, F. M., Sefrji, F. O., & Alsaadi, K. H. (2024). Exploration of genes encoding KEGG pathway enzymes in rhizospheric microbiome of the wild plant Abutilon fruticosum. AMB Express, 14(1), 27.

- Ahmad, N. , Hussain, H., Naeem, M., Rahman, S. U., Khan, K. A., Iqbal, B., & Umar, A. W. (2024). Metabolites-induced co-evolutionary warfare between plants, viruses, and their associated vectors: So close yet so far away. Plant Science 2024, 112165. [Google Scholar]

- Akbar, M. U. , Aqeel, M., Shah, M. S., Jeelani, G., Iqbal, N., Latif, A., Elnour, R. O., Hashem, M., Alzoubi, O. M., & Habeeb, T. (2023). Molecular regulation of antioxidants and secondary metabolites act in conjunction to defend plants against pathogenic infection. South African Journal of Botany 2023, 161, 247–257. [Google Scholar]

- Alghsham, R. , Rasheed, Z., Shariq, A., Alkhamiss, A. S., Alhumaydhi, F. A., Aljohani, A. S., Althwab, S. A., Alshomar, A., Alhomaidan, H. T., & Hamad, E. M. (2022). Recognition of pathogens and their inflammatory signaling events. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences 2022, 10, 462–467. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khayri, J. M., Rashmi, R., Toppo, V., Chole, P. B., Banadka, A., Sudheer, W. N., Nagella, P., Shehata, W. F., Al-Mssallem, M. Q., & Alessa, F. M. (2023). Plant secondary metabolites: The weapons for biotic stress management. Metabolites, 13(6), 716.

- Aller, E. S., Kanstrup, C., Hunziker, P., Kliebenstein, D. J., & Burow, M. (2023). Altered defense patterns upon retrotransposition highlights the potential for rapid adaptation by transposable elements. bioRxiv, 2023.12. 20.572632.

- Alshareef, S. A. (2024). Metabolic analysis of the CAZy class glycosyltransferases in rhizospheric soil fungiome of the plant species Moringa oleifera. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, 31(4), 103956.

- Alves, F., Lane, D., Nguyen, T. P. M., Bush, A. I., & Ayton, S. (2025). In defence of ferroptosis. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 10(1), 2.

- Appu, M., Ramalingam, P., Sathiyanarayanan, A., & Huang, J. (2021). An overview of plant defense-related enzymes responses to biotic stresses. Plant Gene, 27, 100302.

- Aranda, P. S., LaJoie, D. M., & Jorcyk, C. L. (2012). Bleach gel: A simple agarose gel for analyzing RNA quality. ELECTROPHORESIS, 33(2), 366–369. [CrossRef]

- Asif, M., Xie, X., & Zhao, Z. (2024). Virulence regulation in plant-pathogenic bacteria by host-secreted signals. Microbiological Research, 127883.

- Backhed, F., Roswall, J., Peng, Y., Feng, Q., Jia, H., Kovatcheva-Datchary, P., Li, Y., Xia, Y., Xie, H., Zhong, H., Khan, M. T., Zhang, J., Li, J., Xiao, L., Al-Aama, J., Zhang, D., Lee, Y. S., Kotowska, D., Colding, C., … Wang, J. (2015). Dynamics and Stabilization of the Human Gut Microbiome during the First Year of Life. Cell Host Microbe, 17(6), 852. [CrossRef]

- Baduel, P., & Quadrana, L. (2021). Jumpstarting evolution: How transposition can facilitate adaptation to rapid environmental changes. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 61, 102043.

- Balducci, E., Papi, F., Capialbi, D. E., & Del Bino, L. (2023). Polysaccharides’ structures and functions in biofilm architecture of antimicrobial-resistant (AMR) pathogens. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(4), 4030.

- Basak, S., & Annapure, U. S. (2022). Trends in “green” and novel methods of pectin modification-A review. Carbohydrate Polymers, 278, 118967.

- Belay, W. Y., Getachew, M., Tegegne, B. A., Teffera, Z. H., Dagne, A., Zeleke, T. K., Abebe, R. B., Gedif, A. A., Fenta, A., & Yirdaw, G. (2024). Mechanism of antibacterial resistance, strategies and next-generation antimicrobials to contain antimicrobial resistance: A review. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 15, 1444781.

- Bharti, M. K., Chandra, D., Siddique, R. A., Ranjan, K., & Kumar, P. (2024). Recent advancement in high-throughput “omics” technologies. In Current omics advancement in plant abiotic stress biology (pp. 343–355). Elsevier.

- Blair, M. W., Li, H., Nekkalapudi, L., Becerra, V., & Paredes, M. (2023). Nutritional Traits of Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris): Nutraceutical Characterization and Genomics. In C. Kole (Ed.), Compendium of Crop Genome Designing for Nutraceuticals (pp. 611–638). Springer Nature Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Buckeridge, M. S. (2023). The diversity of plant carbohydrate hydrolysis in nature and technology. Polysaccharide-Degrading Biocatalysts, 55–74.

- Campos, M. D., Felix, M. do R., Patanita, M., Materatski, P., Albuquerque, A., Ribeiro, J. A., & Varanda, C. (2022). Defense strategies: The role of transcription factors in tomato–pathogen interaction. Biology, 11(2), 235.

- Cantarel, B. L., Coutinho, P. M., Rancurel, C., Bernard, T., Lombard, V., & Henrissat, B. (2009). The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): An expert resource for Glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Research, 37(Database), D233–D238. [CrossRef]

- Cerutti, G., Gugole, E., Montemiglio, L. C., Turbé-Doan, A., Chena, D., Navarro, D., Lomascolo, A., Piumi, F., Exertier, C., & Freda, I. (2021). Crystal structure and functional characterization of an oligosaccharide dehydrogenase from Pycnoporus cinnabarinus provides insights into fungal breakdown of lignocellulose. Biotechnology for Biofuels, 14, 1–18.

- Chang, H., Ma, M., Gu, M., Li, S., Li, M., Guo, G., & Xing, G. (2024). Acyl-CoA-binding protein (ACBP) genes involvement in response to abiotic stress and exogenous hormone application in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). BMC Plant Biology, 24(1), 236.

- Deng, S., Chen, C., Wang, Y., Liu, S., Zhao, J., Cao, B., Jiang, D., Jiang, Z., & Zhang, Y. (2024). Advances in understanding and mitigating Atrazine’s environmental and health impact: A comprehensive review. Journal of Environmental Management, 365, 121530.

- Dos Santos, C., & Franco, O. L. (2023). Pathogenesis-related proteins (PRs) with enzyme activity activating plant defense responses. Plants, 12(11), 2226.

- EL Sabagh, A., Islam, M. S., Hossain, A., Iqbal, M. A., Mubeen, M., Waleed, M., Reginato, M., Battaglia, M., Ahmed, S., & Rehman, A. (2022). Phytohormones as growth regulators during abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Frontiers in Agronomy, 4, 765068.

- Feng, Q., Liang, S., Jia, H., Stadlmayr, A., Tang, L., Lan, Z., Zhang, D., Xia, H., Xu, X., & Jie, Z. (2015). Gut microbiome development along the colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Nature Communications, 6(1), 6528.

- Forsberg, Z., & Courtade, G. (2023). On the impact of carbohydrate-binding modules (CBMs) in lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases (LPMOs). Essays in Biochemistry, 67(3), 561–574.

- Gharechahi, J., Vahidi, M. F., Sharifi, G., Ariaeenejad, S., Ding, X.-Z., Han, J.-L., & Salekdeh, G. H. (2023). Lignocellulose degradation by rumen bacterial communities: New insights from metagenome analyses. Environmental Research, 229, 115925.

- Huerta-Cepas, J., Szklarczyk, D., Forslund, K., Cook, H., Heller, D., Walter, M. C., Rattei, T., Mende, D. R., Sunagawa, S., & Kuhn, M. (2016). eggNOG 4.5: A hierarchical orthology framework with improved functional annotations for eukaryotic, prokaryotic and viral sequences. Nucleic Acids Research, 44(D1), D286–D293.

- Islam, S. S., Adhikary, S., Mostafa, M., & Hossain, M. M. (2024). Vegetable beans: Comprehensive insights into diversity, production, nutritional benefits, sustainable cultivation and future prospects. OnLine J. Biol. Sci, 24, 477–494.

- Jha, Y., & Mohamed, H. I. (2022). Plant secondary metabolites as a tool to investigate biotic stress tolerance in plants: A review. Gesunde Pflanzen, 74(4), 771–790.

- Kadirvelraj, R., Yang, J.-Y., Kim, H. W., Sanders, J. H., Moremen, K. W., & Wood, Z. A. (2021). Comparison of human poly-N-acetyl-lactosamine synthase structure with GT-A fold glycosyltransferases supports a modular assembly of catalytic subsites. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 296.

- Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Tanabe, M., Sato, Y., & Morishima, K. (2017). KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Research, 45(D1), D353–D361.

- Kanehisa, M., Goto, S., Hattori, M., Aoki-Kinoshita, K. F., Itoh, M., Kawashima, S., Katayama, T., Araki, M., & Hirakawa, M. (2006). From genomics to chemical genomics: New developments in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Research, 34(suppl_1), D354–D357.

- Karlsson, F. H., Fåk, F., Nookaew, I., Tremaroli, V., Fagerberg, B., Petranovic, D., Bäckhed, F., & Nielsen, J. (2012). Symptomatic atherosclerosis is associated with an altered gut metagenome. Nature Communications, 3(1), 1245.

- Karlsson, F. H., Tremaroli, V., Nookaew, I., Bergström, G., Behre, C. J., Fagerberg, B., Nielsen, J., & Bäckhed, F. (2013). Gut metagenome in European women with normal, impaired and diabetic glucose control. Nature, 498(7452), 99–103.

- Kaur, S., Samota, M. K., Choudhary, M., Choudhary, M., Pandey, A. K., Sharma, A., & Thakur, J. (2022). How do plants defend themselves against pathogens-Biochemical mechanisms and genetic interventions. Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants, 28(2), 485–504.

- Khan, K. A., Saleem, M. H., Afzal, S., Hussain, I., Ameen, F., & Fahad, S. (2024). Ferulic acid: Therapeutic potential due to its antioxidant properties, role in plant growth, and stress tolerance. Plant Growth Regulation, 1–25.

- Khoshru, B., Mitra, D., Joshi, K., Adhikari, P., Rion, M. S. I., Fadiji, A. E., Alizadeh, M., Priyadarshini, A., Senapati, A., & Sarikhani, M. R. (2023). RETRACTED: Decrypting the multi-functional biological activators and inducers of defense responses against biotic stresses in plants. Heliyon, 9(3).

- King, D. G. (2024). Mutation protocols share with sexual reproduction the physiological role of producing genetic variation within ‘constraints that deconstrain’. The Journal of Physiology, 602(11), 2615–2626.

- Koner, S., De Sarkar, N., & Laha, N. (2024). False discovery rate control: Moving beyond the Benjamini–Hochberg method. bioRxiv, 2024.01. 13.575531.

- Krasavina, M. S., Burmistrova, N. A., & Raldugina, G. N. (2014). The role of carbohydrates in plant resistance to abiotic stresses. In Emerging technologies and management of crop stress tolerance (pp. 229–270). Elsevier.

- Kumar, S., Jeevaraj, T., Yunus, M. H., Chakraborty, S., & Chakraborty, N. (2023). The plant cytoskeleton takes center stage in abiotic stress responses and resilience. Plant, Cell & Environment, 46(1), 5–22.

- Kumar, S., Korra, T., Thakur, R., Arutselvan, R., Kashyap, A. S., Nehela, Y., Chaplygin, V., Minkina, T., & Keswani, C. (2023). Role of plant secondary metabolites in defence and transcriptional regulation in response to biotic stress. Plant Stress, 8, 100154.

- Li, J., Jia, H., Cai, X., Zhong, H., Feng, Q., Sunagawa, S., Arumugam, M., Kultima, J. R., Prifti, E., & Nielsen, T. (2014). An integrated catalog of reference genes in the human gut microbiome. Nature Biotechnology, 32(8), 834–841.

- Lian, N., Wang, X., Jing, Y., & Lin, J. (2021). Regulation of cytoskeleton-associated protein activities: Linking cellular signals to plant cytoskeletal function. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology, 63(1), 241–250.

- Lika, J., & Fan, J. (2024). Carbohydrate metabolism in supporting and regulating neutrophil effector functions. Current Opinion in Immunology, 91, 102497.

- Liu, B., Liu, L., & Liu, Y. (2024). Targeting cell death mechanisms: The potential of autophagy and ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma therapy. Frontiers in Immunology, 15, 1450487.

- Lu, D., Ren, Y., Yan, T., Jia, X., Xu, H., Yang, B., Zhang, X., & He, J. (2024). Melatonin improves the postharvest anthracnose resistance of mango fruit by regulating antioxidant activity, the phenylpropane pathway and cell wall metabolism. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 1–20.

- Majeed, H. N., Shaheen, S., & Kashif, M. (2024). Glycosyltransferases: Unraveling Molecular Insights and Biotechnological Implications. Science Reviews. Biology, 3(1), 16.

- Marcianò, D., Kappel, L., Ullah, S. F., & Srivastava, V. (2024). From glycans to green biotechnology: Exploring cell wall dynamics and phytobiota impact in plant glycopathology. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology, 1–19.

- Marmion, M., Macori, G., Ferone, M., Whyte, P., & Scannell, A. G. M. (2022). Survive and thrive: Control mechanisms that facilitate bacterial adaptation to survive manufacturing-related stress. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 368, 109612.

- McCartney, N., Kondakath, G., Tai, A., & Trimmer, B. A. (2024). Functional annotation of insecta transcriptomes: A cautionary tale from Lepidoptera. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 165, 104038.

- Molina, A., Sánchez-Vallet, A., Jordá, L., Carrasco-López, C., Rodríguez-Herva, J. J., & López-Solanilla, E. (2024). Plant cell walls: Source of carbohydrate-based signals in plant-pathogen interactions. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 82, 102630.

- Mtonga, A., & Maruthi, M. N. (2024). Diseases of common bean. In Handbook of Vegetable and Herb Diseases (pp. 1–52). Springer.

- Munzert, K. S., & Engelsdorf, T. (2025). Plant cell wall structure and dynamics in plant–pathogen interactions and pathogen defence. Journal of Experimental Botany, 76(2), 228–242.

- Nadarajah, K. K. (2024). Defensive Strategies of ROS in Plant–Pathogen Interactions. In Plant Pathogen Interaction (pp. 163–183). Springer.

- Olmo-Uceda, M. J., Ambrós, S., Corrêa, R. L., & Elena, S. F. (2024). Transcriptomic insights into the epigenetic modulation of turnip mosaic virus evolution in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Genomics, 25(1), 897.

- Qin, J., Li, Y., Cai, Z., Li, S., Zhu, J., Zhang, F., Liang, S., Zhang, W., Guan, Y., & Shen, D. (2012). A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature, 490(7418), 55–60.

- Qin, N., Yang, F., Li, A., Prifti, E., Chen, Y., Shao, L., Guo, J., Le Chatelier, E., Yao, J., & Wu, L. (2014). Alterations of the human gut microbiome in liver cirrhosis. Nature, 513(7516), 59–64.

- Sahakyan, G., & Sahakyan, N. (n.d.). ABC Proteins as Regulators of Plant Tolerance to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. Plant Stress Tolerance, 203–222.

- Sahu, P. K. , Jayalakshmi, K., Tilgam, J., Gupta, A., Nagaraju, Y., Kumar, A., Hamid, S., Singh, H. V., Minkina, T., & Rajput, V. D. (2022). ROS generated from biotic stress: Effects on plants and alleviation by endophytic microbes. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 1042936. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saif, R. , Mahmood, T., Ejaz, A., & Zia, S. (2022). Pathway enrichment and network analysis of differentially expressed genes in pashmina goat. Gene Reports 2022, 27, 101606. [Google Scholar]

- Saini, N., Anmol, A., Kumar, S., Bakshi, M., & Dhiman, Z. (2024). Exploring phenolic compounds as natural stress alleviators in plants-a comprehensive review. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology, 102383.

- Samsami, H., & Maali-Amiri, R. (2024). Global insights into intermediate metabolites: Signaling, metabolic divergence and stress response modulation in plants. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 108862.

- Savary, S. , Ficke, A., Aubertot, J.-N., & Hollier, C. (2012). Crop losses due to diseases and their implications for global food production losses and food security. Food Security 2012, 4, 519–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scher, J. U. , Sczesnak, A., Longman, R. S., Segata, N., Ubeda, C., Bielski, C., Rostron, T., Cerundolo, V., Pamer, E. G., & Abramson, S. B. (2013). Expansion of intestinal Prevotella copri correlates with enhanced susceptibility to arthritis. Elife 2013, 2, e01202. [Google Scholar]

- Shetty, N. P. , Jørgensen, H. J. L., Jensen, J. D., Collinge, D. B., & Shetty, H. S. (2008). Roles of reactive oxygen species in interactions between plants and pathogens. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2008, 121(3), 267–280. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R., Choudhary, P., Kumar, S., & Daima, H. K. (2024). Mechanistic approaches for crosstalk between nanomaterials and plants: Plant immunomodulation, defense mechanisms, stress resilience, toxicity, and perspectives. Environmental Science: Nano.

- Solanki, S., & Das, H. K. (2024). Antimicrobial resistance: Molecular drivers and underlying mechanisms. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health, 3, 100122.

- Songire, V. M., & Patil, R. H. (2025). Microbial Antioxidative Enzymes: Biotechnological Production and Environmental and Biomedical Applications. Applied Biochemistry and Microbiology, 1–26.

- Spitzer, J. (2024). Physicochemical origins of prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms. The Journal of Physiology, 602(11), 2383–2394.

- Su, J., Song, Y., Zhu, Z., Huang, X., Fan, J., Qiao, J., & Mao, F. (2024). Cell–cell communication: New insights and clinical implications. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 9(1), 196.

- Sun, Y., Wang, M., Mur, L. A. J., Shen, Q., & Guo, S. (2020). Unravelling the roles of nitrogen nutrition in plant disease defences. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(2), 572.

- Swaminathan, S. , Lionetti, V., & Zabotina, O. A. (2022). Plant cell wall integrity perturbations and priming for defense. Plants 2022, 11(24), 3539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tamchek, N., & Lee, P.-C. (2024). Comparative Metatranscriptomics of Rhizosphere Microbiomes in Survived and Dead Cocoa Plants Under Drought Condition. Agricultural Research. [CrossRef]

- Thiruvengadam, R., Venkidasamy, B., Easwaran, M., Chi, H. Y., Thiruvengadam, M., & Kim, S.-H. (2024). Dynamic interplay of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS) in plant resilience: Unveiling the signaling pathways and metabolic responses to biotic and abiotic stresses. Plant Cell Reports, 43(8), 198.

- Tiku, A. R. (2020). Antimicrobial compounds (phytoanticipins and phytoalexins) and their role in plant defense. Co-Evolution of Secondary Metabolites, 845–868.

- Uebersax, M. A., Cichy, K. A., Gomez, F. E., Porch, T. G., Heitholt, J., Osorno, J. M., Kamfwa, K., Snapp, S. S., & Bales, S. (2023). Dry beans ( L.) as a vital component of sustainable agriculture and food security—A review. Legume Science, 5(1), e155. [CrossRef]

- ul Qamar, M. T., Noor, F., Guo, Y.-X., Zhu, X.-T., & Chen, L.-L. (2024). Deep-HPI-pred: An R-Shiny applet for network-based classification and prediction of Host-Pathogen protein-protein interactions. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal, 23, 316–329.

- Upadhyay, R., Saini, R., Shukla, P. K., & Tiwari, K. N. (2024). Role of secondary metabolites in plant defense mechanisms: A molecular and biotechnological insights. Phytochemistry Reviews, 1–31.

- Wang, Y. , Pruitt, R. N., Nuernberger, T., & Wang, Y. (2022). Evasion of plant immunity by microbial pathogens. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2022, 20(8), 449–464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wani, S. H., Anand, S., Singh, B., Bohra, A., & Joshi, R. (2021). WRKY transcription factors and plant defense responses: Latest discoveries and future prospects. Plant Cell Reports, 40, 1071–1085.

- Wani, S. , Nisa, Q., Fayaz, T., Naziya Nabi, Aasiya Nabi, Lateef, I., Bashir, A., Rashid, R. J., Rashid, Z., Gulzar, G., Shafi, U., Dar, Z. A., Lone, A. A., Jha, U. C., & Padder, B. A. (2023). An Overview of Major Bean Diseases and Current Scenario of Common Bean Resistance. In U. C. Jha, H. Nayyar, K. D. Sharma, E. J. B. Von Wettberg, P. Singh, & K. H. M. Siddique (Eds.), Diseases in Legume Crops (pp. 99–123). Springer Nature Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Weng, J.-K. , Lynch, J. H., Matos, J. O., & Dudareva, N. (2021). Adaptive mechanisms of plant specialized metabolism connecting chemistry to function. Nature Chemical Biology 2021, 17(10), 1037–1045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, S. , Hu, E., Cai, Y., Xie, Z., Luo, X., Zhan, L., Tang, W., Wang, Q., Liu, B., & Wang, R. (2024). Using clusterProfiler to characterize multiomics data. Nature Protocols 2024, 19(11), 3292–3320. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, A., Yadav, K., Ahmad, R., & Abd-Elsalam, K. A. (2023). Emerging frontiers in nanotechnology for precision agriculture: Advancements, hurdles and prospects. Agrochemicals, 2(2), 220–256.

- Yanamadala, V. (2024). Carbohydrate Metabolism. In Essential Medical Biochemistry and Metabolic Disease: A Pocket Guide for Medical Students and Residents (pp. 1–34). Springer.

- Yang, W., Feng, H., Zhang, X., Zhang, J., Doonan, J. H., Batchelor, W. D., Xiong, L., & Yan, J. (2020). Crop phenomics and high-throughput phenotyping: Past decades, current challenges, and future perspectives. Molecular Plant, 13(2), 187–214.

- Zhao, S. , & Li, Y. (2021). Current understanding of the interplays between host hormones and plant viral infections. PLoS Pathogens 2021, 17(2), e1009242. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X., Tian, H., Li, X., Yan, H., Yang, S., & He, G. (2024). Transcriptome analysis of cadmium accumulation characteristics and fruit response to cadmium stress in Zunla 1 chili pepper. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 10(1), 2437136.

| County | Bean Phenotype | Sub-County | Number of leaf samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bungoma | Rosecoco | Bungoma town | 2 |

| Rosecoco | Bungoma Central | 2 | |

| Rosecoco | Bungoma N/S | 2 | |

| Rosecoco | Bungoma West | 2 | |

| Rosecoco | Kanduyi -kibuke | 3 | |

| Subtotal | 11 | ||

| Busia | Rosecoco | Butula | 5 |

| Rosecoco | Matayos | 5 | |

| Subtotal | 10 | ||

| Kakamega | Rosecoco | Kakamega East | 3 |

| Rosecoco | Kakamega South | 3 | |

| Rosecoco | Kakamega West | 2 | |

| Rosecoco | Lugari | 2 | |

| Subtotal | 10 | ||

| Nandi | Rosecoco | Nandi South (Aldai) | 10 |

| Rosecoco | Subtotal | 10 | |

| Vihiga | Rosecoco | Hamisi | 5 |

| Rosecoco | Sabatia | 5 | |

| Subtotal | 10 | ||

| Total | 51 |

| sample | raw_reads | clean_reads | clean_bases | error_rate | Q20 | Q30 | GC_pct |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RVK1 | 37064327 | 35716390 | 10.71G | 0.03 | 97.95 | 94.09 | 48.51 |

| RBU1 | 35629275 | 34974467 | 10.49G | 0.02 | 98.01 | 94.22 | 47.59 |

| RBGM1 | 44496998 | 44004580 | 13.2G | 0.02 | 98.05 | 94.43 | 47.32 |

| Length interval | 200bp-500bp | 500bp-1kbp | 1kb-2kbp | >2kbp | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of transcripts | 737712 | 253527 | 94250 | 50538 | 1136027 |

| Number of Unigenes | 290828 | 157122 | 55200 | 29752 | 532902 |

| Min_length | Mean_length | Median_length | Max_length | N50 | N90 | Total_nucleotides | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcript | 251 | 636 | 396 | 37763 | 762 | 293 | 722372701 |

| Genes | 251 | 727 | 470 | 37763 | 873 | 344 | 387683453 |

| Database Name | Level | Description Of Level |

|---|---|---|

| KEGG | level1 | KEGG pathway level1 include 6 pathway database; |

| KEGG | level2 | KEGG pathway level2 43 sub-pathway database; |

| KEGG | level3 | KEGG pathway id(e.g. map00010); |

| KEGG | KO | KEGG ortholog group (e.g. K00010); |

| KEGG | EC | KEGG EC Number(e.g. EC 3.4.1.1); |

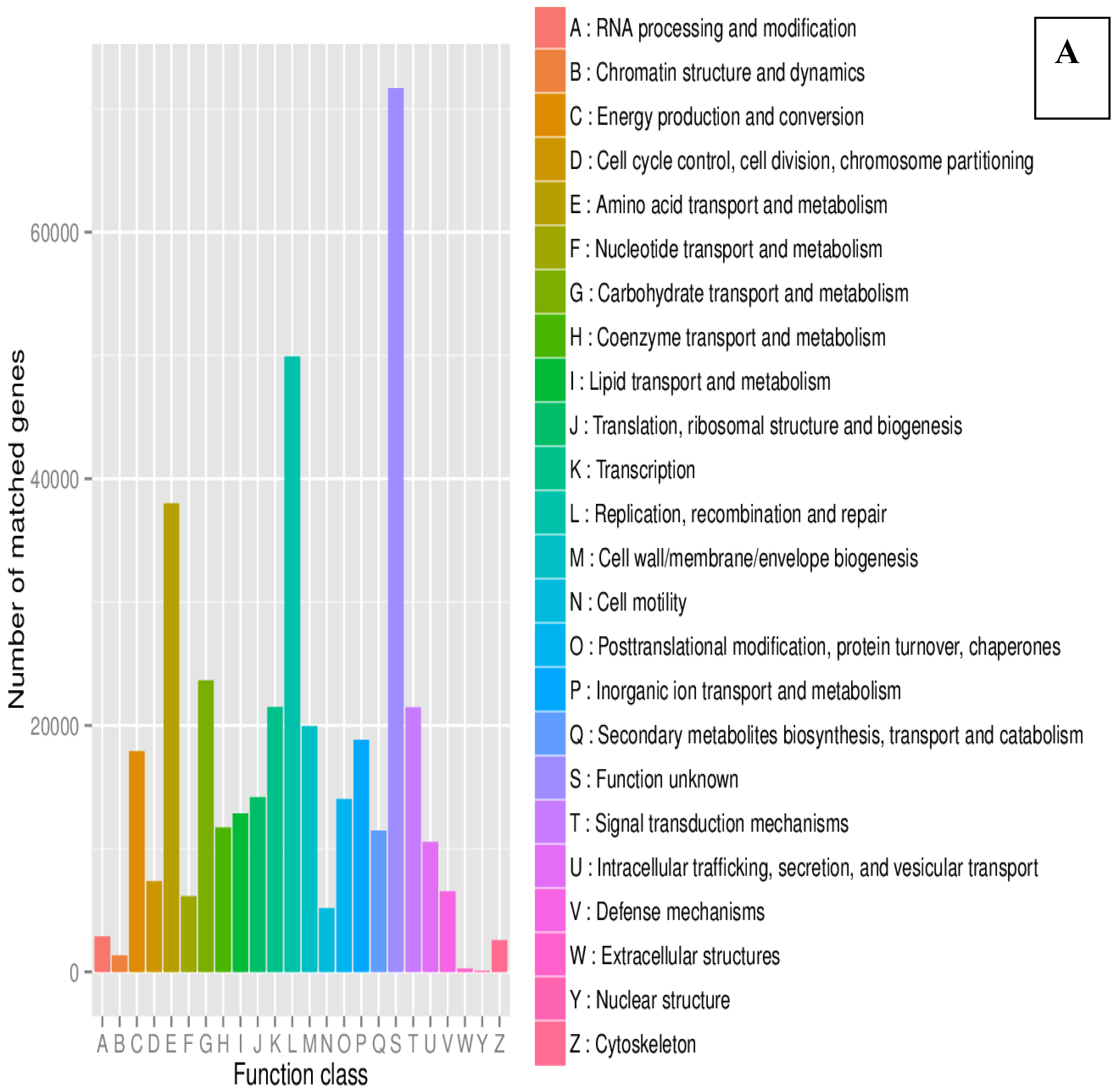

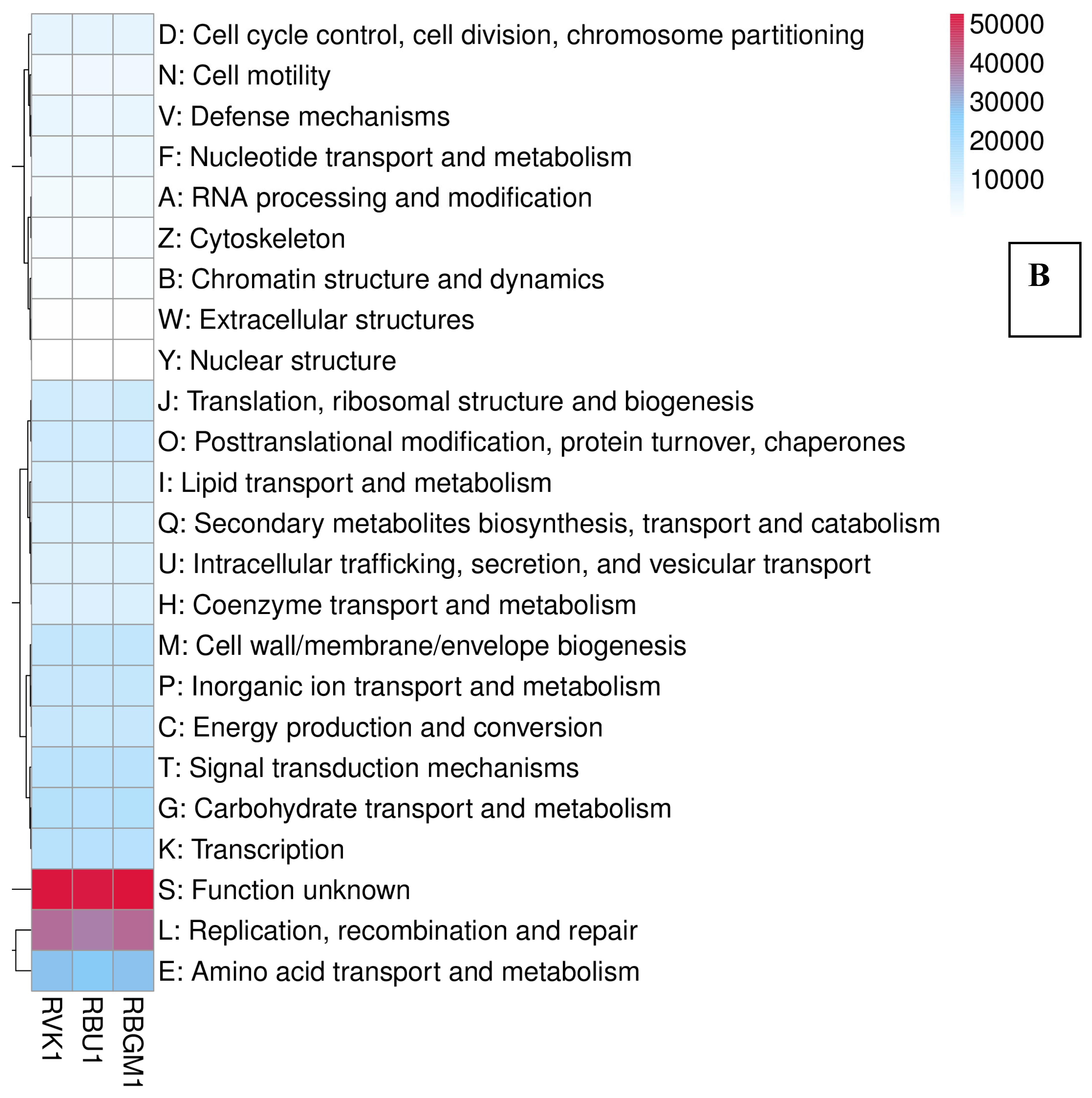

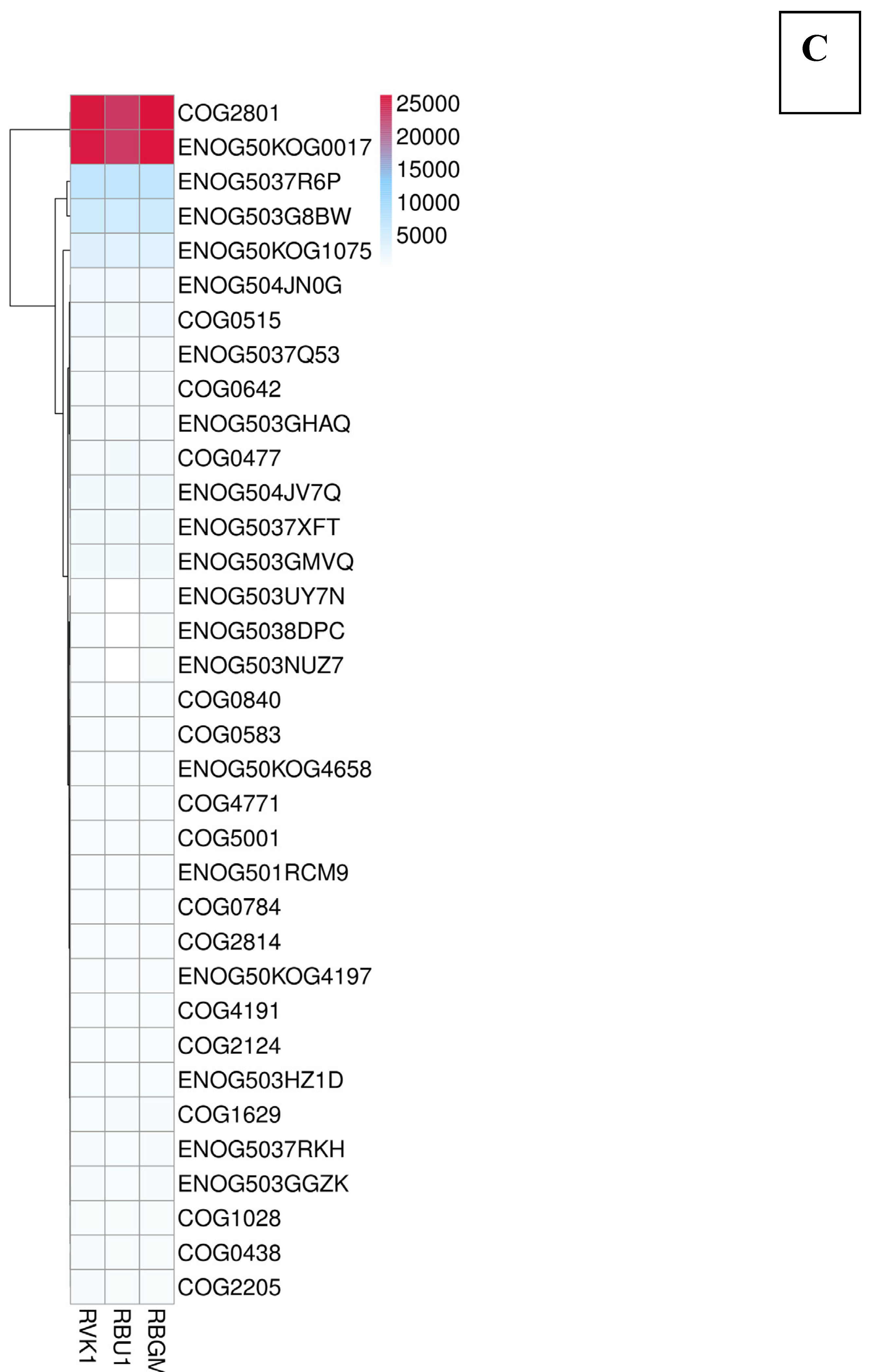

| eggNOG | level1 | 24 function taxa; |

| eggNOG | level2 | ortholog group description; |

| eggNOG | og | ortholog group ID(e.g. ENOG410YU5S); |

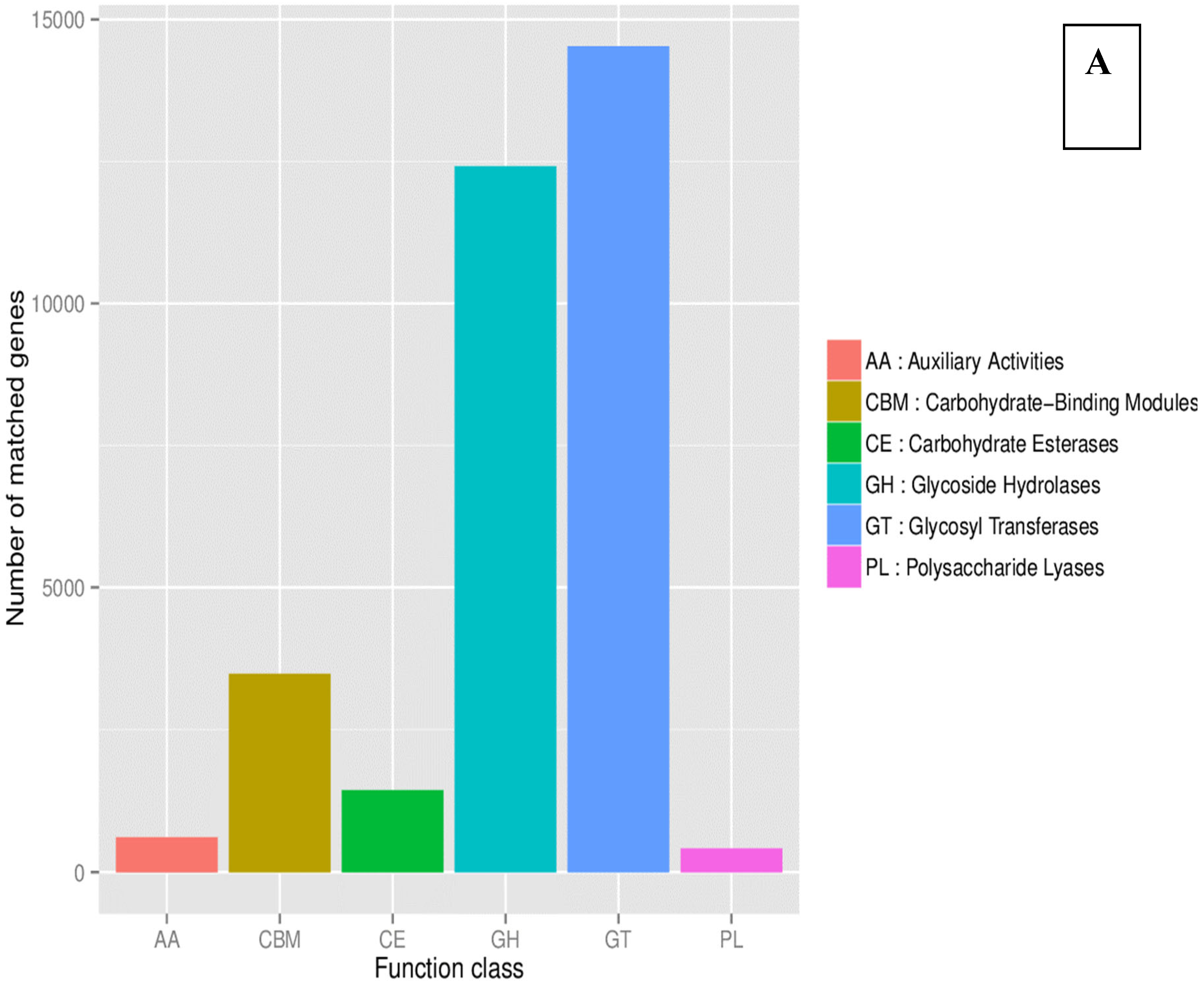

| CAZy | level1 | 6 major function classes; |

| CAZy | level2 | CAZy family(e.g. GT51); |

| CAZy | EC | EC number(e.g. murein polymerase (EC 2.4.1.129) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).