Submitted:

05 December 2024

Posted:

06 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

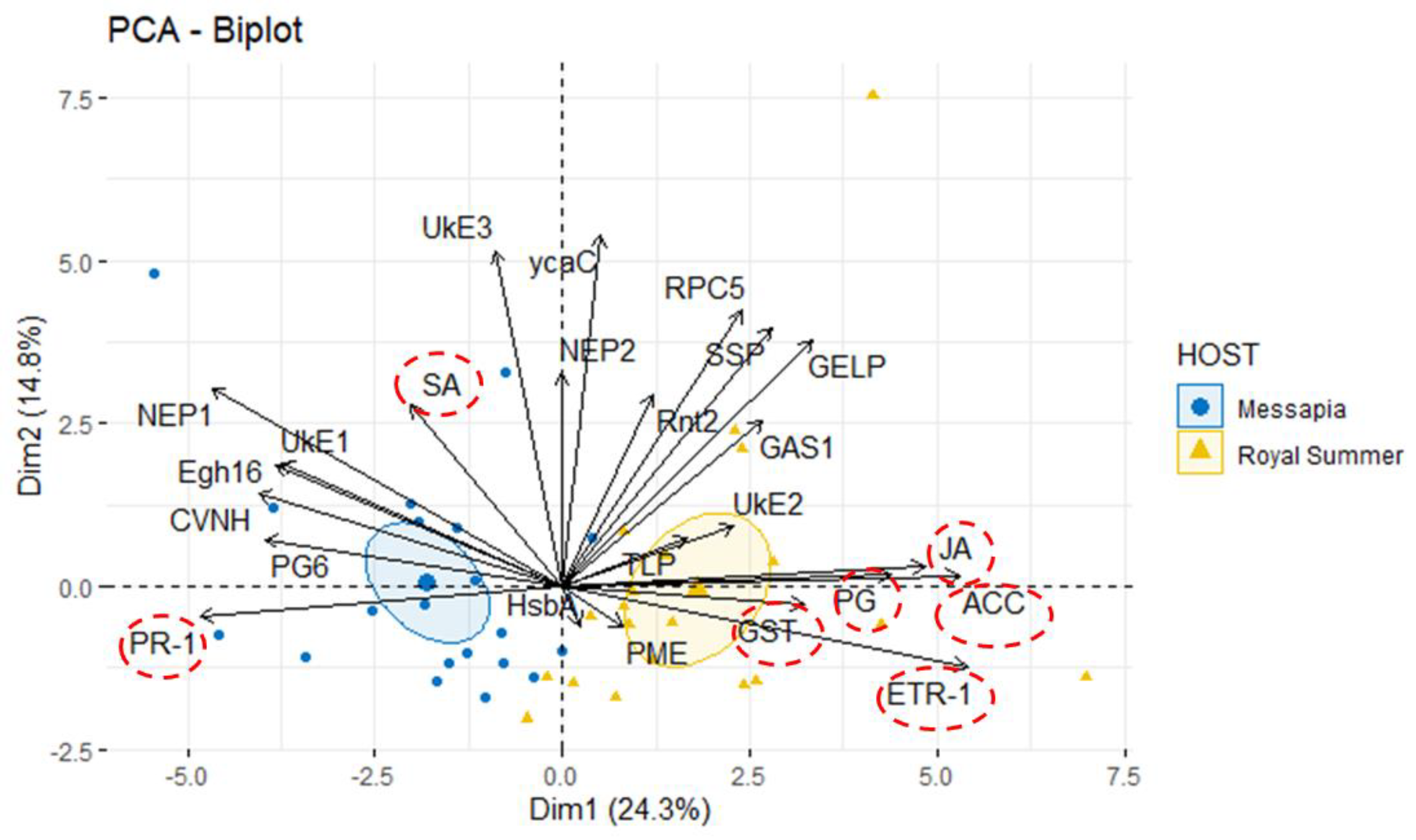

Monilinia fructicola is the most common and destructive brown rot agent on peaches. Knowledge of gene expression mediating host–pathogen interaction is essential to manage fungal plant diseases. M. fructicola putative virulence factors have been predicted by genome investigations. The pathogen interaction with the host was validated. Five M. fructicola isolates were inoculated on two cultivars (cv.s) of peach [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch] ‘Royal Summer’ and ‘Messapia’ with intermediate and late ripening periods, respectively. The expression pattern of 17 candidate effector genes of M. fructicola with functions linked to host invasion and fungal life, and seven peach genes involved in the immune defense system were monitored at 0, 2, 6, 10, and 24 h-post inoculation (hpi). All fungal isolates induced similar brown rot lesions on both cv.s whereas the modulation of effector genes was regulated mainly at 2, 6, and 10 hpi, when disease symptoms appeared on the fruit surface, confirming the involvement of effector genes in the early infection stage. Although differences were observed among the fungal isolates, the principal component investigation identified the main differences linked to the host genotype. The salicylic acid and jasmonate/ethylene signaling pathways were differently modulated in the host independent from the fungal isolate used for inoculation. On plants susceptible to brown rot, the pathogen may have adapted to the host’s physiology by modulating its effectors as weapons.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tested Fungal Isolates

2.2. Virulence In Vivo Assay

2.3. Gene Expression Investigation

2.3.1. RNA Extraction

2.3.2. Reverse Transcription

2.3.3. Primers and Reference Gene Selection

2.3.4. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. In Vivo Test: Virulence Assay

3.2. Gene Expression Analysis

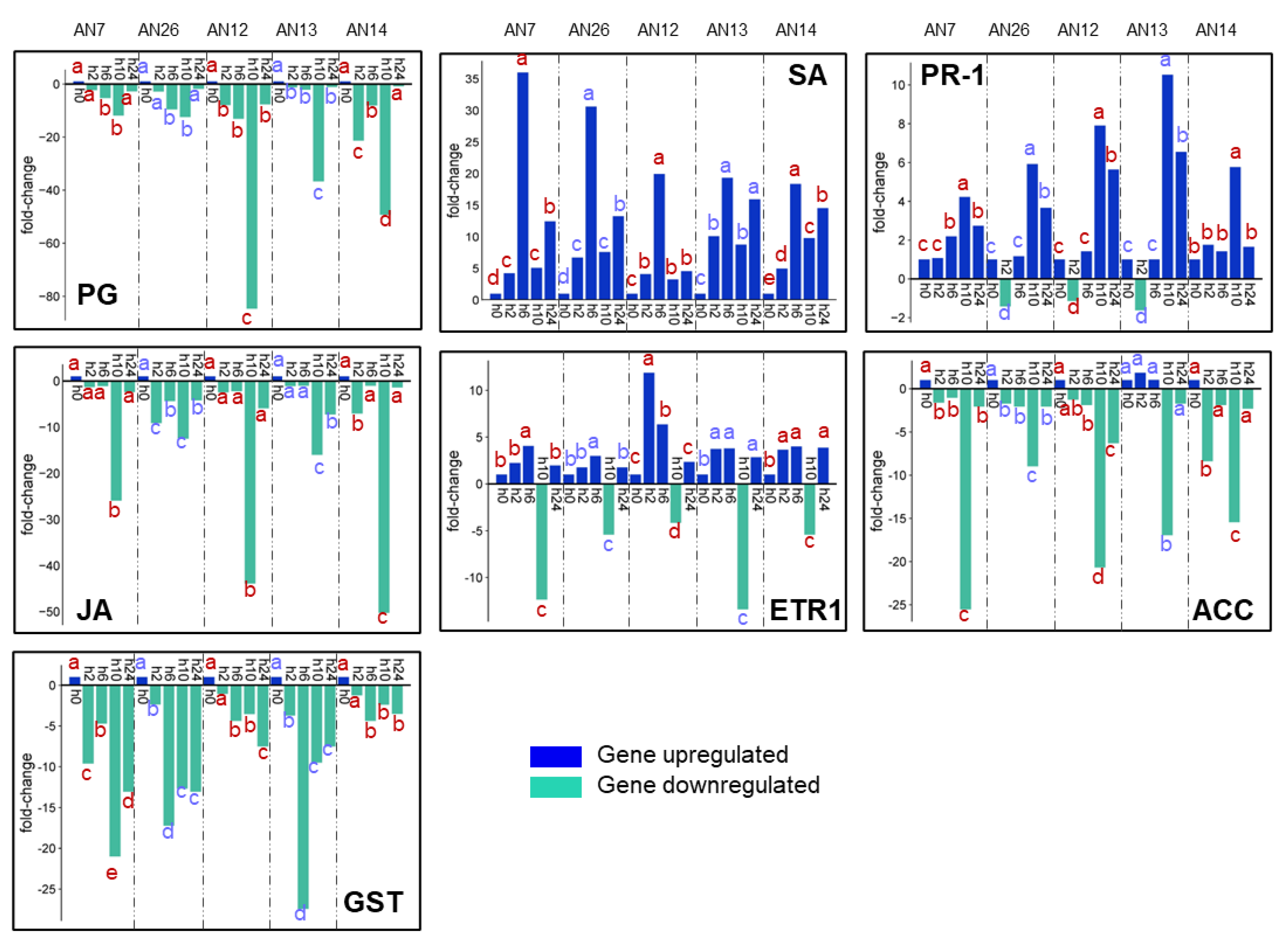

3.2.1. Expression of M. fructicola Putative Effectors Genes

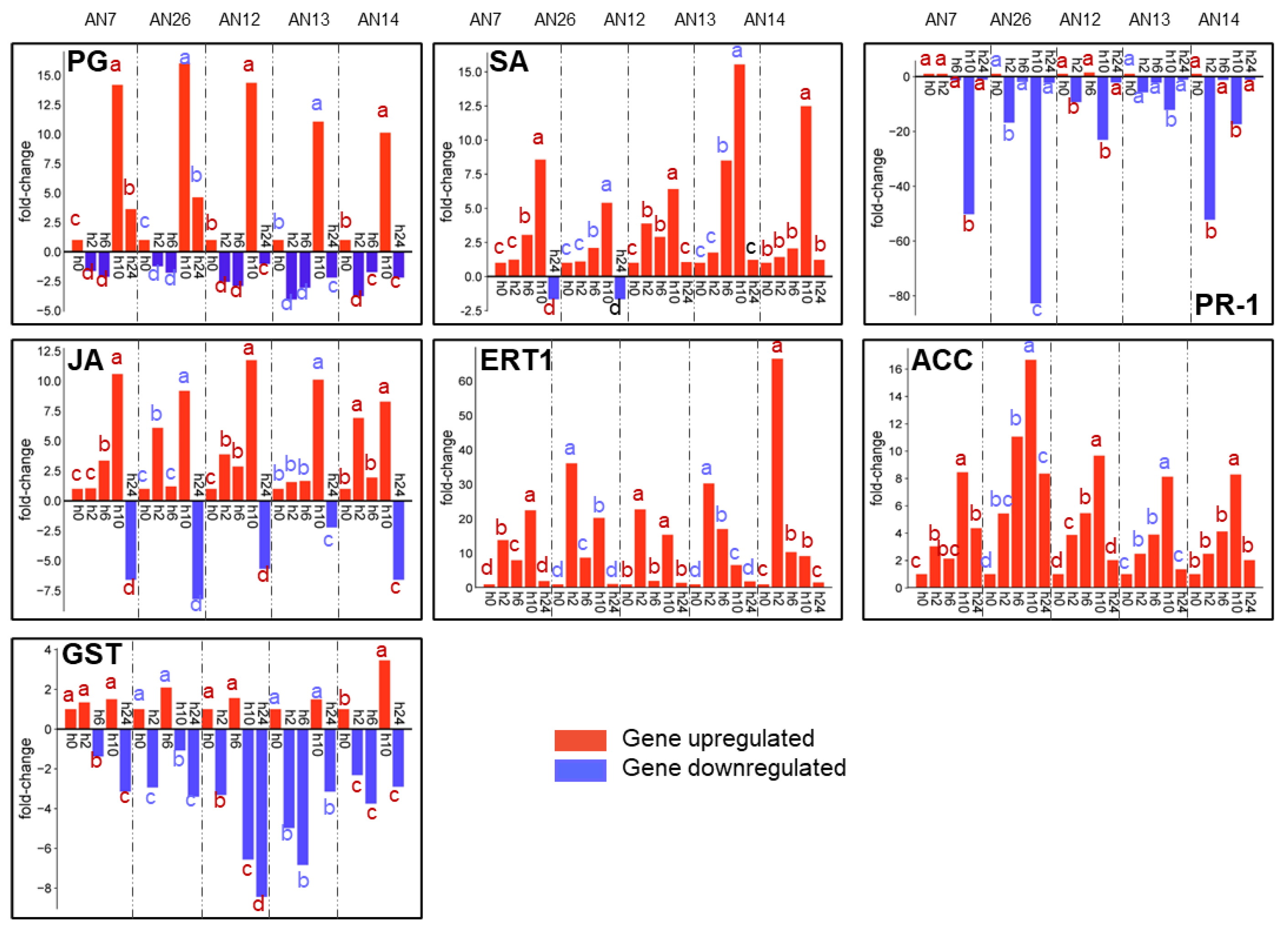

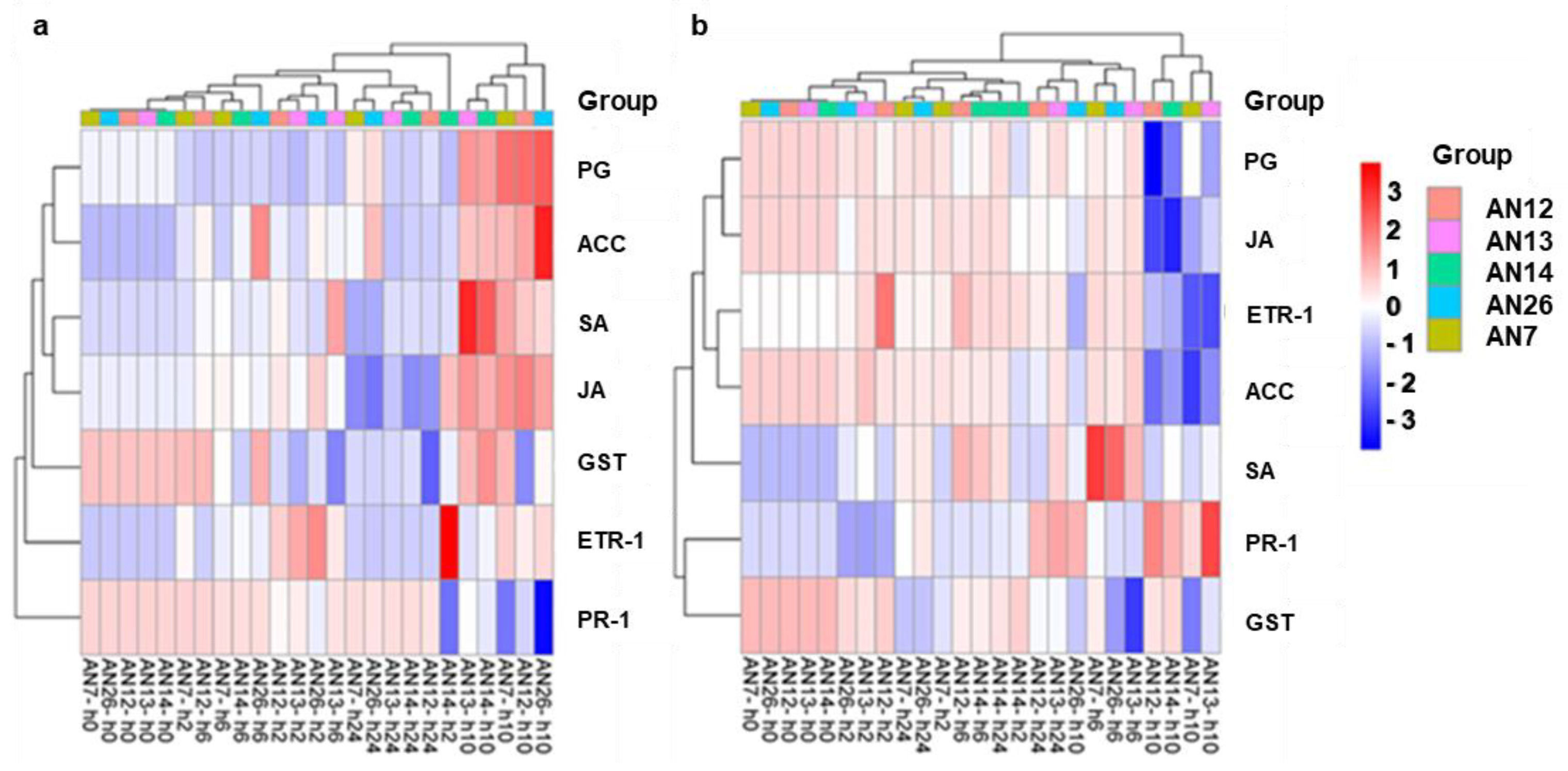

3.2.2. Expression of Peach Defense Genes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Byrde, R.J.W.; Willetts, H.J. The Brown Rot Fungi of Fruit - Their Biology and Control. Pergamon Press: New York, NY. 1977.

- Casals, C.; Torres, R.; Teixidó, N.; De Cal, A.; Segarra, J.; Usall, J. Brown rot on stone fruit: From epidemiology studies to the development of effective control strategies. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 301, 111096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, G.C.M.; Baayen, R.P.; Jeger, M.J. Pest risk assessment for the countries of the European Union (as PRA area) on Monilinia fructicola. EPPO Bull. 2001, 31, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usall, J.; Casals, C.; Sisquella, M.; Palou, L.; De Cal, A. Alternative technologies to control postharvest diseases of stone fruits. Stewart Postharvest Rev. 2015, 11, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M.H.; Bassi, D.; Corre, M.N.; Lino, L.O.; Signoret, V.; Quilot-Turion, B.; Cirilli, M. Phenotyping brown rot susceptibility in stone fruit: A literature review with emphasis on peach. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, I.M.; McNamara, D.G.; Scott, P.R.; Holderness, M. “Monilinia fructicola,” in Quarantine Pests for Europe, 2nd Edn, Wallingford, GB: CAB International, 1997.

- Lichou, J.; Mandrin, J.-F.; Breniaux, D.; Mercier, V.; Giauque, P.; Desbrus, D.; et al. (2002). Une nouvelle moniliose: Monilia fructicola s’attaque aux arbres fruitiers à noyaux. Phytoma 547, 22–25.

- Abate, D.; Pastore, C.; Gerin, D.; De Miccolis Angelini, R.M.; Rotolo, C.; Pollastro, S.; Faretra, F. Characterization of Monilinia spp. populations on stone fruit in South Italy. Plant Dis. 2018, 102, 1708–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, L.; Feliziani, E.; Romanazzi, G. Surveys for Monilinia spp. on stone fruit in central-eastern Italy. Acta Hortic. [CrossRef]

- Villarino, M.; Melgarejo, P.; De Cal, A. Growth and aggressiveness factors affecting Monilinia spp. survival peaches. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 227, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holb, I.J. Disease warning models for brown rot fungi of fruit crops. Int. J. Hortic. Sci. 2013, 9, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makau, S.M.; Moumni, M.; Landi, L.; Pirozzi, D.; Sannino, F.; Romanazzi, G. In vitro evaluation of chitosan hydrochloride and COS (Chito-Oligosaccharides)-OGA (Oligo-Galacturonides) on Phytopathogenic Fungi and Escherichia coli. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remolif, G.; Buonsenso, F.; Schiavon, G.; Garello, M.; Spadaro, D. Efficacy of Essential Oil Vapours in Reducing Postharvest Rots and Effect on the Fruit Mycobiome of Nectarines. J. Fungi, /: 341. https, 3390. [Google Scholar]

- Dangl, J.L.; Horvath, D.M.; Staskawicz, B.J. Pivoting the plant immune system from dissection to deployment. Science 2013, 341, 746–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascale, A.; Proietti, S.; Pantelides, I.S.; Stringlis, I.A. Modulation of the Root Microbiome by Plant Molecules: The Basis for Targeted Disease Suppression and Plant Growth Promotion. Front. Plant. Sci. 2020, 10, 1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saijo, Y.; Loo, E.P.; Yasuda, S. Pattern recognition receptors and signaling in plant-microbe interactions. Plant J. 2018, 93, 592–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Wang,Y. ; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Biosynthesis and Regulation of Salicylic Acid and N-Hydroxypipecolic Acid in Plant Immunity. Mol. Plant. 2020, 13, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarad, M.; Mariappan, K.; Almeida-Trapp, M.; Mette, M.F.; Mithofer, A.; Rayapuram, N.; Hirt, H. The Lamin-Like LITTLE NUCLEI 1 (LINC1) Regulates Pattern-Triggered Immunity and Jasmonic Acid Signaling. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocafort, M.; Fudal, I.; Mesarich, C.H. Apoplastic effector proteins of plant-associated fungi and oomycetes. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2020, 56, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toruño, T.Y.; Stergiopoulos, I.; Coaker, G. Plant-Pathogen Effectors: Cellular Probes Interfering with Plant Defenses in Spatial and Temporal Manners. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2016, 54, 419–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vleeshouwers, V.G.A.A.; Oliver, R.P. Effectors as Tools in Disease Resistance Breeding Against Biotrophic, Hemibiotrophic, and Necrotrophic Plant Pathogens. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2014, 27, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, L.; De Miccolis Angelini, R.M.; Pollastro, S.; Abate, D.; Faretra, F.; Romanazzi, G. Genome sequence of the brown rot fungal pathogen Monilinia fructigena. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo-Ortiz, M.A.; Rodriguez-Pires, S.; Torres, R.; De Cal, A.; Usall, J.; Gabaldon, T. Genome sequence of the brown rot fungal pathogen Monilinia laxa. Genome Announc. 2018, 6, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, Y.; Zeller, K.; Srivastava, S.; Sutherland, J.; Galvez, M.; Nakhla, M.; Poniatowska, A.; Schnabel, G.; Sundin, G.; Gloria, Z.A. Draft genome resources for the phytopathogenic fungi Monilinia fructicola, M. fructigena, M. polystroma, and M. laxa, the causal agents of Brown rot. Phytopathology, 2018; 108, 1141–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Miccolis Angelini, R.M.; Romanazzi, G.; Pollastro, S.; Rotolo, C.; Faretra, F.; Landi, L. New high-quality draft genome of the brown rot fungal pathogen Monilinia fructicola. Genome Biol. Evol. 2019, 11, 2850–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, L.; Pollastro, S.; Rotolo, C.; Romanazzi, G.; Faretra, F.; De Miccolis Angelini, R.M. Draft genomic resources for the brown rot fungal pathogen Monilinia laxa. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2020, 33, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilanova, L.; Valero-Jiménez, C.A.; Van Kan, J.A.L. Deciphering the Monilinia fructicola Genome to Discover Effector Genes Possibly Involved in Virulence. Genes 2021, 12, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcet-Houben, M.; Villarino, M.; Vilanova, L.; De Cal, A.; Van Kan, J.A.L.; Usall, J.; Gabaldon, T.; Torres, R. Comparative genomics used to predict virulence factors and metabolic genes among Monilinia species. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, A.; van Kan, J.A.L.; Beenen, H.G.; Dolcet-Sanjuan, R.; Teixidó, N.; Torres, R.; Vilanova, L. Evaluation of cell death-inducing activity of Monilinia spp. effectors in several plants using a modified TRV expression system. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1428613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Miccolis Angelini, R.M.; Landi, L.; Raguseo, C.; Pollastro, S.; Faretra, F.; Romanazzi, G. Tracking of Diversity and Evolution in the Brown Rot Fungi Monilinia fructicola, Monilinia fructigena, and Monilinia laxa. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 854852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Côté, M.J.; Tardif, M.C.; Meldrum, A.J.; Identification of Monilinia fructigena, M. fructicola, M. laxa, and Monilia polystroma on Inoculated and Naturally Infected Fruit Using Multiplex PCR. Plant Dis. 2004; 88, 1219–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarino, M.; Melgarejo, P.; De Cal, A. Growth and aggressiveness factors affecting Monilinia spp. survival peaches. Int J Food Microbiol. 2016; 224, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustin, S.A.; Benes, V.; Garson, J.A.; Hellemans, J.; Huggett, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L.; Vandesompele, S.J.; Wittwer, C.T. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 2009, 55, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina-Hernandez, J.B.; Landi, L.; Laika De Fraviis, R.; Romanazzi, G.; Chaves-López, C. Understanding the mechanisms of action of atmospheric cold plasma towards the mitigation of the stress induced in molds: The case of Aspergillus chevalieri. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 90, 103492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, L.; Peralta-Ruiz, Y.; Chaves-López, C.; Romanazzi, G. Chitosan Coating Enriched With Ruta graveolens L. Essential Oil Reduces Postharvest Anthracnose of Papaya (Carica papaya L.) and Modulates Defense-Related Gene Expression. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 765806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandesompele, J.; De Preter, K.; Pattyn, F.; Poppe, B.; Van Roy, N.; De Paepe, A.; Speleman, F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Cheng, J.; Wei, L.; Li, M.; Wu, J. Functional analysis of the Nep1-like proteins from Plasmopara viticola. Plant Signal Behav. 2022, 17, 2000791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Steentjes, M.B.F.; Herrera Valderrama, A.L.; Fouillen, L.; Bahammou, D.; Leisen. T.; Albert, I.; Nürnberger, T.; Hahn, M.; Mongrand, S.; Scholten, O.E.; Van Kan, J.A.L. Cytotoxic activity of Nep1-like proteins on monocots. New Phytol. 2022, 235, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maurus, I.; Harting, R.; Herrfurth, C.; Starke, J.; Nagel, A.; Mohnike, L.; Chen, Y.Y.; Schmitt, K.; Bastakis, E.; Süß, M.T.; Leonard, M.; Heimel, K.; Valerius, O.; Feussner, I.; Kronstad, J.W.; Braus, G.H. Verticillium dahliae Vta3 promotes ELV1 virulence factor gene expression in xylem sap, but tame,s Mtf1-mediated late stages of fungus-plant interactions and microsclerotia formation. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhu, W.; Wei, W.; Fu, Y.; Cheng, J.; Xie, J.; Li, G.; et al. A secretory protein of necrotrophic fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum that suppresses host resistance. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Lin, H.; Lu, W.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y. ; Lin, Yifen.; Fan, Z. The role of cell wall polysaccharides disassembly in Lasiodiplodia theobromae-induced disease occurrence and softening of fresh longan fruit. Food Chem. 2021; 351, 129294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Meghwanshi, GK.; Marcianò, D.; Ullah, S.F.; Bulone, V.; Toffolatti, S.L.; Srivastava, V. Sequence, structure and functionality of pectin methylesterases and their use in sustainable carbohydrate bioproducts: A review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafiei, V.; Vélëz, H.; Tzelepis, G. The Role of Glycoside Hydrolases in Phytopathogenic Fungi and Oomycetes Virulence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.A.; España, J.D.A.; Hea-Reung, P.; Schwartze, V.U.; Schäuble, S.; Krüger, T.; Kniemeyer, O.; Brakhage, A.A.; Voigt, K. P343 Novel hydrophobic binding surface proteins are instrumental for phagocytosis of Lichtheimia corymbifera by macrophages. Med. Mycol. J. 2022, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D.; Yarden, O.; Hadar, Y. Seeking the roles for fungal small-secreted proteins in affecting saprophytic lifestyles. Front Microbiol. /: 11:455. https. [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Sun, W.; Chen, Z.; Shi, L.; Hong, J.; Shi, J. Plant GDSL Esterases/Lipases: Evolutionary, Physiological and Molecular Functions in Plant Development. Plants 2022, 11, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xu, Z.; Yin, W.; Xu, K.; Wang, S.; Shang, Q.; Sa, W.; Liang, J.; Wang, L. Genome-wide analysis of the Thaumatin-like gene family in Qingke (Hordeum vulgare L. var. nudum) uncovers candidates involved in plant defense against biotic and abiotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 912296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu J, Feng S, Liu T, Mao Y, Shen S, Liu Y, Hao Z and Li Z (2024) Molecular characterization revealed the role of thaumatin-like proteins of Rhizoctonia solani AG4-JY in inducing maize disease resistance. Front. Microbiol. 15:1377726. [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, B.; Liang, W. The secreted ribonuclease T2 protein FoRnt2 contributes to Fusarium oxysporum virulence. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 3, 1346–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu T, Song T, Zhang X, Yuan H, Su L, Li W, Xu J, Liu S, Chen L, Chen T, Zhang M, Gu L, Zhang B, Dou D. Unconventionally secreted effectors of two filamentous pathogens target plant salicylate biosynthesis. Nat Commun. 2014 Aug 26;5:4686. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vorlander, M.K.; Khatter, H.; Wetzel, R.; Hagen, W.J.H.; Muller, C.W. Molecular mechanism of promoter opening by RNA polymerase III. Nature, 2018; 553, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadfield, K.A.; Rose, J.K.; Yaver, D.S.; Berka, R.M.; Bennett, A.B. Polygalacturonase gene expression in ripe melon fruit supports a role for polygalacturonase in ripening-associated pectin disassembly. Plant Physiol. 1998, 117, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schott-Verdugo, S.; Müller, L.; Classen, E.; Gohlke, H.; Groth, G. Structural Model of the ETR1 Ethylene Receptor Transmembrane Sensor Domain. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forouhar, F.; Yang, Y.; Kumar, D.; Chen, Y.; Fridman, E.; Park, S.W.; Chiang, Y.; Acton, T.B.; Montelione, G.T.; Pichersky, E.; Klessig, D.F.; Tong, L. Structural and biochemical studies identify tobacco SABP2 as a methyl salicylate esterase and implicate it in plant innate immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005, 102, 1773–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Luo, X.; Tian, T.; Feng, L.; Yang, X.; Li, L.; Tan, X.; Wu, W.; Li, Z.; Treves, H.; Serneels, F.; Ng, IS.; Tanaka, K.; Ren, M. Pathogenesis-related protein 1 suppresses oomycete pathogen by targeting against AMPK kinase complex. J. Adv. Res. 2023, 43, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stroud, E.A.; Jayaraman, J.; Templeton, M.D.; Rikkerink, E.H.A. Comparison of the pathway structures influencing the temporal response of salicylate and jasmonate defence hormones in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 952301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houben, M.; Van de Poel, B. 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-Carboxylic Acid Oxidase (ACO): The Enzyme That Makes the Plant Hormone Ethylene. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaish, S.; Gupta, D.; Mehrotra, R.; Mehrotra, S.; Basantani, M.K. Glutathione S-transferase: a versatile protein family. 3 Biotech. 2020, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. (2009). ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Verlag New York:Springer. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Soliman, A.; Islam, M.R.; Adam, L.R.; Daayf, F. Verticillium dahliae's Isochorismatase Hydrolase Is a Virulence Factor That Contributes to Interference With Potato's Salicylate and Jasmonate Defense Signaling. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mihaylova, D.; Popova, A.; Desseva, I.; Petkova, N.; Stoyanova, M.; Vrancheva, R.; Slavov, A.; Slavchev, A.; Lante, A. Comparative Study of Early- and Mid-Ripening Peach (Prunus persica L.) Varieties: Biological Activity, Macro-, and Micro- Nutrient Profile. Foods, 2021; 10, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladysheva-Azgari, M.V. .; Slobodova, N.V.; Boulygina, E.S.; Sharko, F.S.; Rastorguev, S.M.; Smykov, A.V.; Mitrofanova, I.V.; Tsygankova, S.V. Trascriptomic Profiles of Three Peach (Prunus Persica (L.) Batsch) Cultivars with Different Ripening Periods at the Initial Fruiting Stages. Nanotechnol. Russia 2023, 18, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, T.; Chen, Y.; Li, B.; Tian, S. Characterization of two SGNH family cell death-inducing proteins from the horticulturally important fungal pathogen Botrytis cinerea based on the optimized prokaryotic expression system. Mol. Hortic. 2024, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cheng, A.P.; Lederer, B.; Oberkofler, L. ; Huang L, Johnson NR, Platten F, Dunker F, Tisserant C, Weiberg A. A fungal RNA-dependent RNA polymerase is a novel player in plant infection and cross-kingdom RNA interference. PLoS Pathog. 2023 Dec 20;19:e1011885. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derbyshire, M.; Denton-Giles, M.; Hegedus, D.; Seifbarghy, S.; Rollins, J.; Van-Kan, J.; Seidl, M.F.; Faino, L.; Mbengue, M.; Navaud, O.; Raffaele, S.; Hammond-Kosack, K.; Heard, S.; Oliver, R. The complete genome sequence of the phytopathogenic fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum reveals insights into the genome architecture of broad host range pathogens. Genome Biol. Evol. 2017, 9, 593–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kirsten, S.; Navarro-Quezada, A.; Penselin, D.; Wenzel, C. ; Matern. A.; Leitner, A.; Baum, T.; Seiffert, U.; Knogge, W. Necrosis-inducing proteins of Rhynchosporium commune, effectors in quantitative disease resistance. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact, 2012; 25, 1314–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staats, M.; Van Baarlen, P.; Schouten, A.; Van Kan, J.A.L.; Bakker, F.T. Positive selection in phytotoxic protein-encoding genes of Botrytis species. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2007, 44, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plesken, C.; Pattar, P.; Reiss, B.; Noor, Z.N.; Zhang, L.; Klug, K.; Huettel, B.; Hahn, M. Genetic Diversity of Botrytis cinerea Revealed by Multilocus Sequencing, and Identification of B. cinerea Populations Showing Genetic Isolation and Distinct Host Adaptation. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 663027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guyon, K, Balagué, C. ; Roby, D.; Raffaele, S. Secretome analysis reveals effector candidates associated with broad host range necrotrophy in the fungal plant pathogen Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lenarčič, T.; Albert, I.; Böhm, H.; Hodnik, V.; Pirc, K.; Zavec, A.B.; Podobnik, M.; Pahovnik, D.; Žagar, E.; Pruitt, R.; et al. Eudicot plant-specific sphingolipids determine host selectivity of microbial NLP cytolysins. Science 2017, 358, 1431–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoal-Ferreira, P.; Chahed, A.; Costa, R.; Branco, I.; Choupina, A. Use of iRNA in the post-transcriptional gene silencing of necrosis-inducing Phytophthora protein 1(NPP1) in Phytophthora cinnamomi. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 6493–6504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schürch, S.; Linde, C.C.; Knogge, W.; Jackson, L.F.; McDonald, BA. Molecular Population Genetic Analysis Differentiates Two Virulence Mechanisms of the Fungal Avirulence Gene NIP1. Mol. plant-microb. interact. 2004, 17(10), 1114-1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellbrich, G.; Romanski, A.; Varet, A.; Blume, B.; Brunner, F.; Engelhardt, S.; Felix, G.; Kemmerling, B.; Krzymowska, M.; Nürnberger, T. NPP1, a Phytophthora-associated trigger of plant defense in parsley and Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2002, 32, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arenas, Y.C.; Kalkman, E.R.; Schouten, A.; Dieho, M.; Vredenbregt, P.; Uwumukiza, B.; Ruiz, M.O.; Van Kan, J.A. Functional analysis and mode of action of phytotoxic Nep1-like proteins of Botrytis cinerea. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2010, 74, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalgatidou, P.C.; Boutsika, A.; Papageorgiou, A.G.; Dalianis, A.; Michaliou, M.; Chatzidimopoulos, M.; Delis, C.; Tsitsigiannis, D.I.; Paplomatas, E.; Zambounis, A. Global Transcriptome Analysis of the Peach (Prunus persica) in the Interaction System of Fruit-Chitosan-Monilinia fructicola. Plants 2024, 13, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Han, Z.; Xiong, D.; Schneiter, R.; Tian, C. The function of plant PR1 and other members of the CAP protein superfamily in plant–pathogen interactions. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2023, 24, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Kwok, S.F.; Bleecker, A.B.; Meyerowitz, E.M. Arabidopsis ethylene-response gene ETR1: similarity of product to two-component regulators. Science 1993, 262, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlot, A.C.; Dempsey, D.A.; Klessig, D.F. Salicylic acid, a multifaceted hormone to combat disease. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2009, 47, 177–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Chang, C.; Tucker, M.L. To grow old: regulatory role of ethylene and jasmonic acid in senescence. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baró-Montel, N.; Vall-Llaura, N.; Giné-Bordonaba, J.; Usall, J.; Serrano-Prieto, S.; Teixidó, N.; Torres, R. Double-sided battle: The role of ethylene during Monilinia spp. infection in peach at different phenological stages. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 144, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Locus tag | Code | Name | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| aEYC84_006718* | NEP1 | necrosis- and ethylene-inducing protein 1 | This family consists of several NePs, including necrosis and ethylene-inducing proteins from oomycetes, fungi, and bacteria [37,38]. |

| bEYC84_009186* | NEP2 | necrosis- and ethylene-inducing protein 2 | |

| bEYC84_007944* | Egh16 | Egh16-like virulence factor | Egh16-like virulence factors are found in many pathogenic filamentous fungi and are thought to play a role in host interaction [39]. |

| bEYC84_002620* | CVNH | CVNH - CyanoVirin-N homology | CyanoVirin-N Homology domains are found in the sugar-binding antiviral protein cyanovirin-N (CVN) and filamentous ascomycetes. In S. sclerotiorum, CVNH was associated with plant infection and was proposed to suppress plant resistance hypersensitive response [40]. |

| bEYC84_008853* | PG6 | polygalacturonase 6 | Polygalacturonase (PG) is one of the main enzymes in fungal pathogens to degrade plant cell walls, facilitating penetration and colonization of the host [41]. |

| bEYC84_010609* | PME | pectin methylesterase and related acyl-CoA thioesterases | Pectin methylesterase is the first enzyme acting to modify pectins in plant cell walls [42]. |

| EYC84_008964* | GAS1 | probable GAS1 Glycophospholipid-anchored surface glycoprotein | GAS1 elongates the β-1,3-glucan chains and plays an important role in the biosynthesis of the fungal cell walls. GAS1 induces typical hypersensitive response and systemic acquired resistance (SAR) defense responses [43] |

| dEYC84_001420* | HsbA | hydrophobic surface binding protein A | HsbA is a specific fungal spore-secreted protein that can bind to hydrophobic surfaces. These proteins can recruit lytic enzymes to the surface and promote their degradation [44]. |

| bEYC84_008014* | SSP | small secreted protein | Comprising 40–60% of the total fungal secretome, SSPs are defined as proteins that contain a signal peptide and a sequence of less than 300 amino acids [45]. |

| aEYC84_003936* | GELP | GDSL-type esterase/lipase proteins (GELPs) | GELPs represent a variety of lipolytic enzymes that hydrolyze diverse lipidic substrates, including thioesters, aryl esters, and phospholipids [46] |

| cEYC84_000899* | TLP | osmotin/thaumatin-like superfamily | TLPs belong to the pathogenesis-related 5 protein family in plants, playing a significant role in host defense [47]. In fungi, the secretion activity and endo-β-1,3-glucanase activity of the TLP family members were detected [48]. |

| cEYC84_005201* | Rnt2 | ribonuclease T2-like | The Rnt2 family was identified during the plant infection and contributes to the virulence of the pathogen through the degradation of plant RNA [49]. |

| bEYC84_002145* | ycaC | isochorismatase | Isochorismatases involved in the cellular amino acid catabolic process have been found in the secretome of phytopathogens. They are a precursor of salicylic acid and many other distinct derivatives in plants, fungi, and bacteria [50]. |

| aEYC84_004547* | RPC5 | RPC5 protein | This family represents the RPC5 protein, which is part of the RNA polymerase III complex. It acts as a nuclear and cytosolic DNA sensor involved in innate immune response and can sense non-self dsDNA that serves as a template for transcription into dsRNA [51]. |

| aEYC84_003395* | UkE1 | hypothetical protein | Unknown |

| bEYC84_005228* | UkE2 | hypothetical protein | |

| eEYC84_011230* | UkE3 | hypothetical protein | |

| NM_001405051.1** | PG | polygalacturonase | PGs are an important pectolytic glycanase, primarily implicated in the softening of fruit during ripening [52]. |

| AF124527.1** | ETR-1 | ethylene receptor, transcript ETR1 | ETR-1 is included in the ethylene receptor family [53]. |

| XM_007203058.2** | SA | salicylic acid-binding protein 2 | This protein is required to convert methyl salicylate to salicylic acid as part of the signal transduction pathways that activate SAR in systemic tissue [54]. |

| JF694923.1** | PR-1 | pathogenesis-related protein 1 | PR-1 constitutes a secretory peptide family. This protein plays important roles in plant metabolism in response to biotic and abiotic stresses, and its role in plant defense has been widely demonstrated [55]. |

| XM_020560994.1** | JA | jasmonic acid-amido synthetase | JA is involved in jasmonic acid defense biosynthesis [56]. |

| XM_007215636.2** | ACC | 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase | ACC catalyzes the final step in ethylene biosynthesis [57]. |

| XM_007215891.2** | GST | glutathione S-transferase F12 | GST has been implemented in diverse plant functions, such as detoxification of xenobiotic, secondary metabolism, growth and development, and especially against biotic and abiotic stresses [58]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).