1. Introduction

Apples are important and favored fruits because of their sweetness and tartness and because they are nutrient rich [

1]. Apple gray mold, caused by

Botrytis cinerea, is an important postharvest disease in apple that significantly reduces fruit shelf-life and accelerates quality deterioration, resulting in severe economic losses [

2,

3]. The fungus is a widespread host necrotroph and uses a large variety of infection strategies to infect more than 1,400 different plant species [

4]. Currently, based on numerous studies, the main methods used to control gray mold in apple are chemical and biological methods. Among chemical agents, the mustard variety Dilong-1 has been used to inhibit mycelial growth, spore formation and spore germination of

B.

cinerea in vitro [

5]. Among biological agents,

Bacillus subtilis and

Streptomyces terminalis have both been used as safe and environmentally friendly alternatives to chemical fungicides for controlling apple gray mold [

2]. The genetic acquisition of resistance is an ideal method for controlling this disease and is the goal of breeders involved in apple germplasm research. The identification of resistance mechanisms against pathogen infection is essential for identifying resistance genes that can be used in the breeding of resistant apple cultivars.

B. cinerea is a necrotrophic fungus that secretes cell wall-degrading enzymes in the early stages of infestation to regulate apoptotic mechanisms and induce local cell death [

6]. MeJA and ethylene are two hormones conferring strong resistance to

B. cinerea [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Salicylic acid (SA) generated through the PAL pathway confers local resistance against

B. cinerea, but systemic and strong SA accumulation by mutation of the cytoplasmic receptor-like kinase BIK1 in Arabidopsis and treatment with the signaling peptide Zip1 in maize dampens resistance to

B.

cinerea [

13,

14,

15]. The receptor-like proteins RLP30 and RLP23 positively while RLP42 negatively and the receptor-like kinases BAK1, SoBIR1 and PORK1 positively confer resistance to

B.

cinerea [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. To date, the mechanisms involved in pathogen perception and immunity generation, especially in the highly developed rosaceous perennial woody plants, are not fully understood.

Cell wall-associated kinases (WAKs) or WAK-like proteins (WAKLs) are receptor-like kinases (RLKs) tethered to the cell wall and participate in the sensing of pathogens or wound-associated molecular patterns by promoting the formation of immunity generation complexes [

21,

22,

23,

24]. WAKs confer strong resistance against pathogen infection in crops. In maize, ZmWAKL interacts with a leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase, ZmWIK1, to initiate immune signaling which is relayed to ZmBLK1 to initiate reactive oxygen species biosynthesis to confer resistance against the causative pathogen for gray leaf spot [

23]. In cotton, GhWAK7A directly interacts with GhLYK5 and GhCERK1 and promotes chitin-induced GhLYK5-GhCERK1 dimerization, contributing to cotton defense against wilt-causing pathogens [

24].

WAK1 overexpression resulted in increased resistance to

B.

cinerea; however, the null functions of the 5 WAKs did not affect resistance, indicating the intricate involvement of the genes in disease resistance regulation [

25,

26]. The silencing of RcWAK8 and RcWAK4rendered rose petals more susceptible to

B. cinerea. It can be hypothesized that certain genes with the GUB-WAK domain may confer resistance to

B.

cinerea [

27]. Forty-four WAK genes were annotated in the apple genome [

28]. However, WAKs conferring resistance against

B. cinerea in apple have not been identified.

Zymoseptoria tritici is a fungal pathogen of wheat that causes leaf blight, which causes severe yield losses worldwide [

29]. Stb6 encodes a WAKL and is the first cloned important disease resistance gene shown to specifically confer resistance to

Z.

tritici [

30]. Owing to the similarity between this fungus and

B.

cinerea in terms of leaf infection characteristics and the existence of a conserved domain encoded by resistance genes in different plant species, we were interested in the role of Stb6 orthologs in apple that has not been revealed previously.

In our research, we identified 15 orthologs of Stb6, which contains the WAK domain or GUB-WAK domain, conducted bioinformatic analysis, function prediction and expression analysis for different organs and identified MdStb6-13 as the gene conferring resistance to B. cinerea.

2. Results

2.1. Identification of the MdStb6 Gene Family and Analysis of the Physicochemical Properties of Encoded Proteins

The Stb6 gene in wheat has been sequenced, and its conserved domains have been revealed [

30]. Therefore, we used this sequence to perform BLASTp searches to identify Stb6 genes in the

Malus domestica genome, and then three domains, PF13947: GUB-WAK, PF14380:WAK, and PS50011:Protein kinase, were used to verify the members. Through validation, 15 candidate genes harboring both the GUB-WAK or WAK and kinase domains were identified, and these were named MdStb6-1 to MdStb6-15. These genes encoded proteins of 526 (MdStb6-15) to 723 (MdStb6-4) amino acids, with an average length of 620 amino acids (

Table 1). The amino acid identities of the encoded proteins with Stb6 ranged from 23.12% (MdStb6-11) to 35.01% (MdStb6-1) (

Table 1).

In addition, the isoelectric points (pIs) of the encoded proteins ranged from 5.21 (MdStb6-2) to 8.65 (MdStb6-6), and their molecular weights (MWs) ranged from 58.5 kD (MdStb6-15) to 82.0 kD (MdStb6-4). Other information about these genes, such as predictions of subcellular locations and the start and end points of the key domains GUB-WAK and WAK, is provided in

Table 1.

The homologous genes shared significant homology, with the highest identity of 92.92% shown between MdStb6-5 and MdStb6-6 in amino acid sequence (

Table S1).

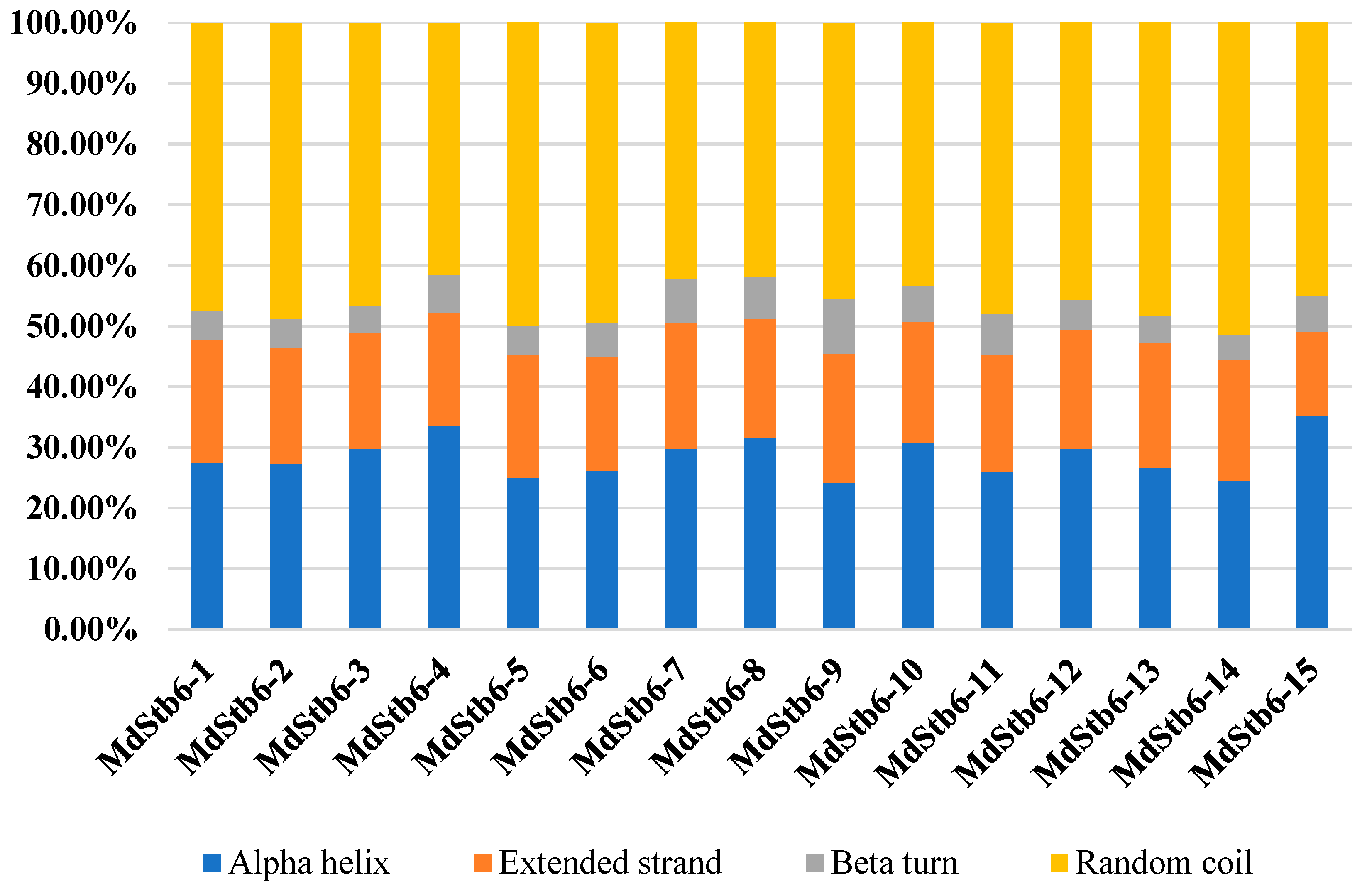

As shown in

Figure 1,the secondary structures of the MdStb6 family proteins were dominated by irregular coils, α-helices, and extended chains, which accounted for 41.49% (MdStb6-4)~51.49% (MdStb6-14), 24.18% (MdStb6-9)~35.17% (MdStb6-15), and 13.88% (MdStb6-15)~21.24% (MdStb6-9) of the secondary structures, respectively. β-Turns accounted for 4.03% (MdStb6-14)~7.25% (MdStb6-7) of the secondary structures, representing a relatively small proportion. These predictions suggest that these genes are located in the membrane and nucleus.

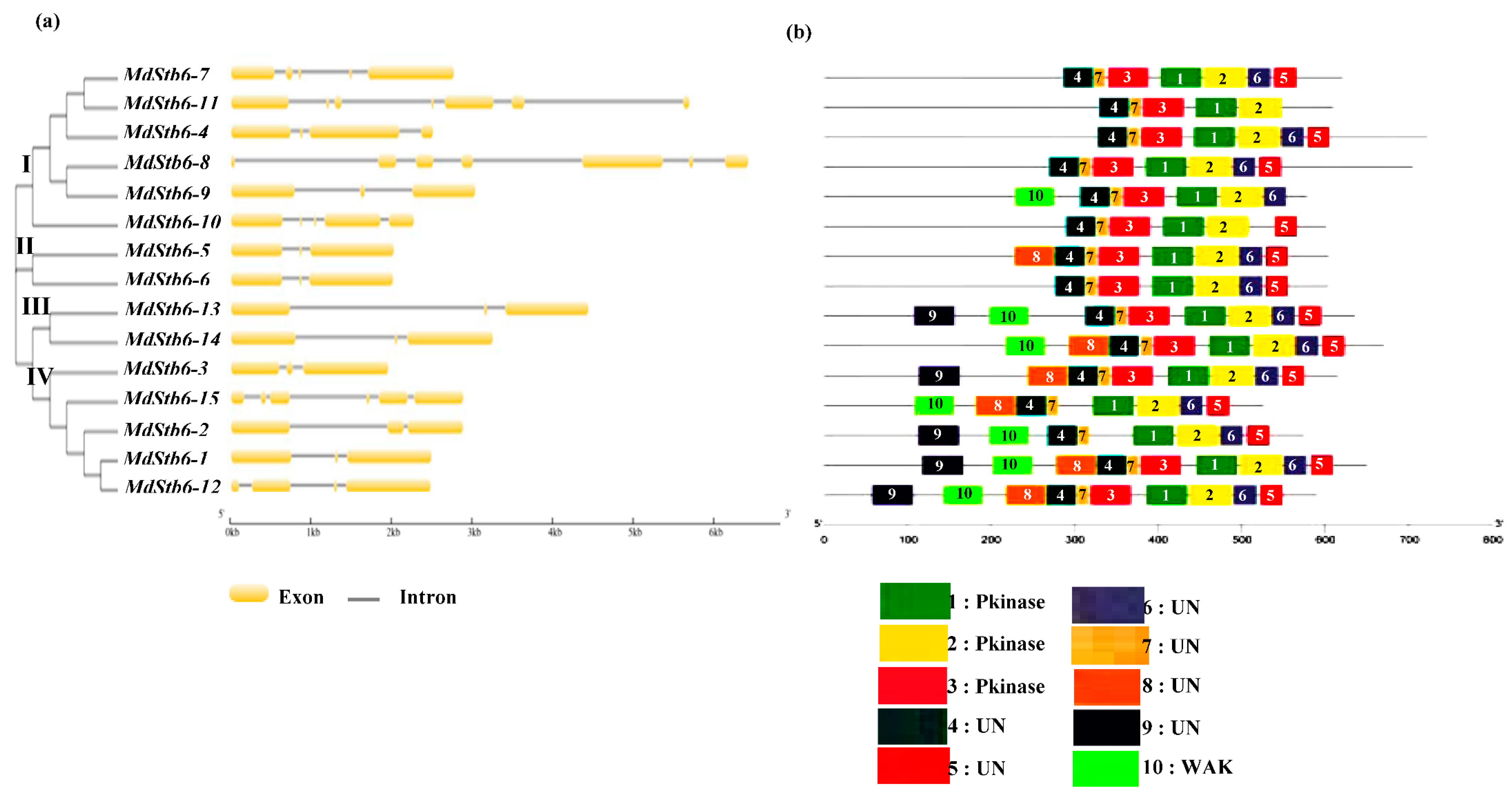

2.2. Gene Structure, Motif Composition and Phylogenetic Analysis of MdStb6 Genes

The exon‒intron organizations of all the identified MdStb6 genes were examined to gain more insight into the evolution of the MdStb6 family in apple. As shown in

Figure 2a, all the MdStb6 genes possessed three to seven exons; genes with only one or two exons were not observed. Genes within the same group generally exhibited a similar structure; for example, MdStb6-5 and MdStb6-6, belonging to the same group, both contained three exons and two introns, and the locations of the exons and introns were also similar (

Figure 2a). The similarity in the lengths of the MdStb6-5/MdStb6-6 introns and exons suggests that this pair of genes may have originated from homologous gene duplications.

The conserved motifs of the MdStb6 proteins were examined via the InterPro database, and ten were identified (

Figure 2b). Motifs 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6 and 4 and 7 were the conserved basic motifs in the MdStb6 homologs. Among them, motifs 1, 2 and 3 were related to kinases and were all present in all the genes except motif 3, which was absent in MdStb6-2 and MdStb6-15.Motifs 4 and 7 could be considered conserved structural domains of unknown function common to all members of MdStb6 family (

Figure 2b). Motifs 5 and 6, the two motifs in the C-terminal regions of the proteins, were also generally present in the homologs, except motif 5, which was absent in MdStb6-9 andMdStb6-11, and motif 6, which was absent in MdStb6-10 and MdStb6-11(

Figure 2b).

MdStb6-1 and MdStb6-12 harbored all ten motifs, and Mdtb6-11 contained the fewest, with only five of the motifs (1, 2, 3, 4 and 7).

Motif 10, which is cysteine-rich and usually located at the C-terminus of the galacturonic acid-binding domain, functions as a WAK structural domain. The genes with WAK structural domains in

Table 1 all harbored motif 10, as shown in

Figure 2b.

The logos are shown in

Figure 2c, with no functions assigned to motifs 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9.

To better understand the evolutionary relationships among MdStb6 family members, a phylogenetic tree was constructed via the NJ method in the MEGA11 program using 98 amino acid sequences from six species, namely, apple (15), wheat (2), tomato (5), rice (1),

Arabidopsis thaliana (6), peach (47), and grape (22). These sequences were roughly divided into four groups: groups I, II, III and IV (

Figure 2d). All the MdStb6 gene family members belonged to groups I and II and were in the same branch as the WAK gene family members of strawberry and peach. These genes could be divided into two clades. Clade I included MdStb6-1, MdStb6-2, MdStb6-3, MdStb6-5, MdStb6-6, MdStb6-12, MdStb6-13, MdStb6-14 and MdStb6-15. Clade II included MdStb6-4, MdStb6-7, MdStb6-8, MdStb6-9, MdStb6-10 and MdStb6-11. ZmWALK, which confers resistance to gray leaf spot in maize [

23], exhibited a close relationship with clade II. Stb6 in wheat exhibited a close relationship with the genes in Clade I (

Figure 2d).

The genes exhibited a more distant genetic relationship with AtWAK1-5 and GhWAK7A. However, they shared homology with Xa4, the gene conferring resistance through increased cell wall biosynthesis and jasmonic acid (JA) accumulation [

31].

This finding suggests the divergence of the MdStb6 homologous genes.

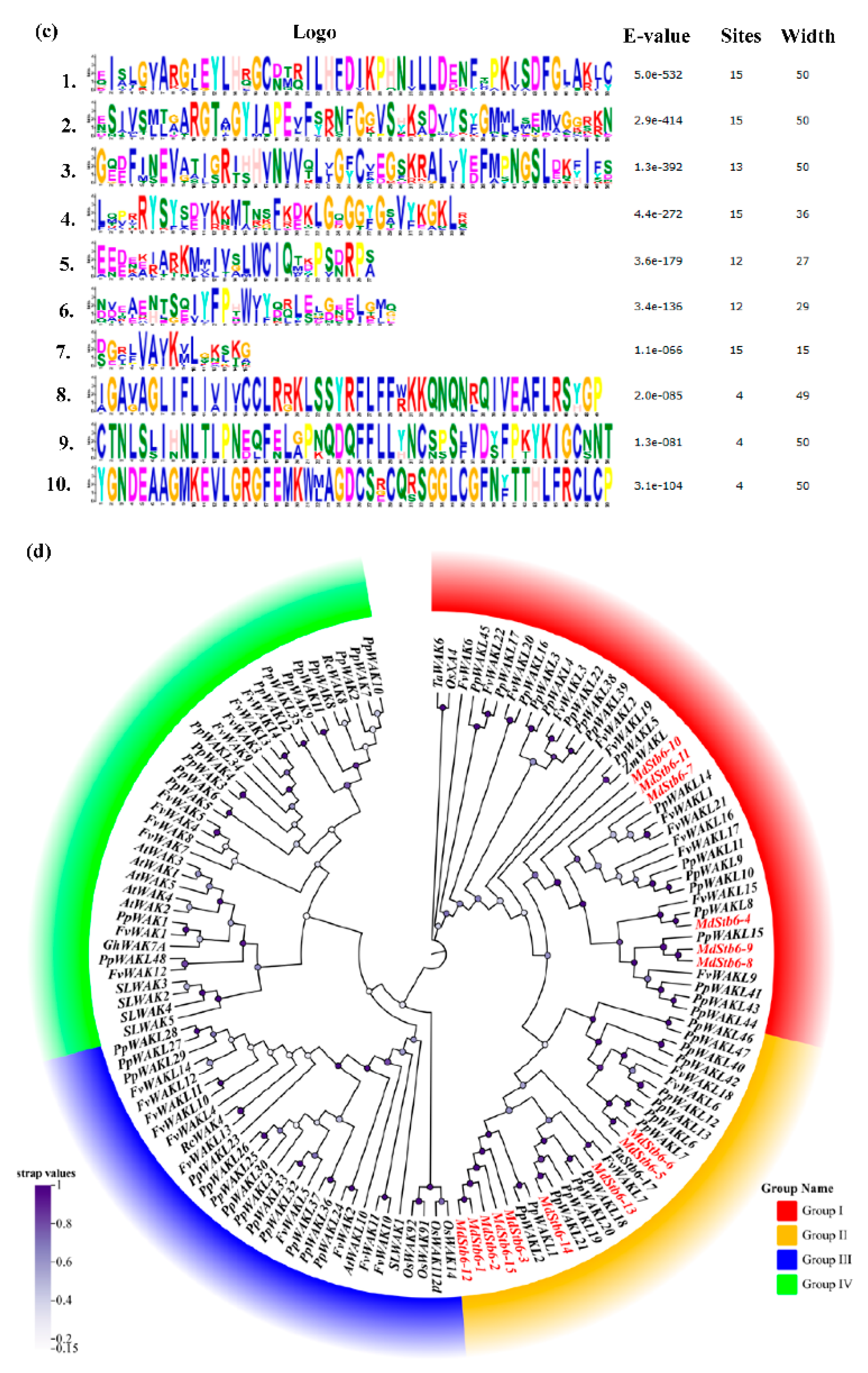

3.3. Chromosomal Locations and Synteny Analysis of MdStb6 Homolog Genes

On the basis of the gene location information obtained from the GDR database, we attempted to map the 15 MdStb6 genes onto the 17 apple chromosomes. We found that 14 genes were unevenly distributed on six of the 17 chromosomes (

Figure 3a), whereas the location of MdStb6-11 could not be identified, probably because this gene was located in the genomic scaffold, which was not assembled. As shown in

Figure 3a, chromosome 2 contained the greatest number of MdStb6 family genes, including MdStb6-4, MdStb6-7, MdStb6-8, MdStb6-9 and MdStb6-6, followed by chromosome 13, which included MdStb6-1, MdStb6-2, MdStb6-12 and MdStb6-15. MdStb6-13 and MdStb6-14 were located on chromosome 6, and chromosomes 8, 12 and 16 each harbored only one gene, i.e., MdStb6-5, MdStb6-10 and MdStb6-3, respectively. No MdStb6 genes were present on the nine remaining apple chromosomes.

As shown in

Figure 3b, fragment duplication and tandem duplication are important modes of gene duplication. One pair of genes exhibited collinearity, MdStb6-3/MdStb6-13, which may be related to large fragment duplication. The appearance of two genes within an interval of 200 kb is deemed the result of a tandem duplication event. The presence of four pairs of tandemly duplicated genes, MdStb6-1/MdStb6-12, MdStb6-2/MdStb6-15, MdStb6-4/MdStb6-6 and MdStb6-8/MdStb6-9, suggests that tandem duplication played a major role in the expansion of the MdStb6 family in apple. MdStb6-13 and MdStb6-14 were located on the same chromosome but were more distantly related.

These findings suggest that both fragment duplication and tandem replication played important roles in the occurrence of MdStb6 homologs and in the evolutionary conservation of the homologous genes.

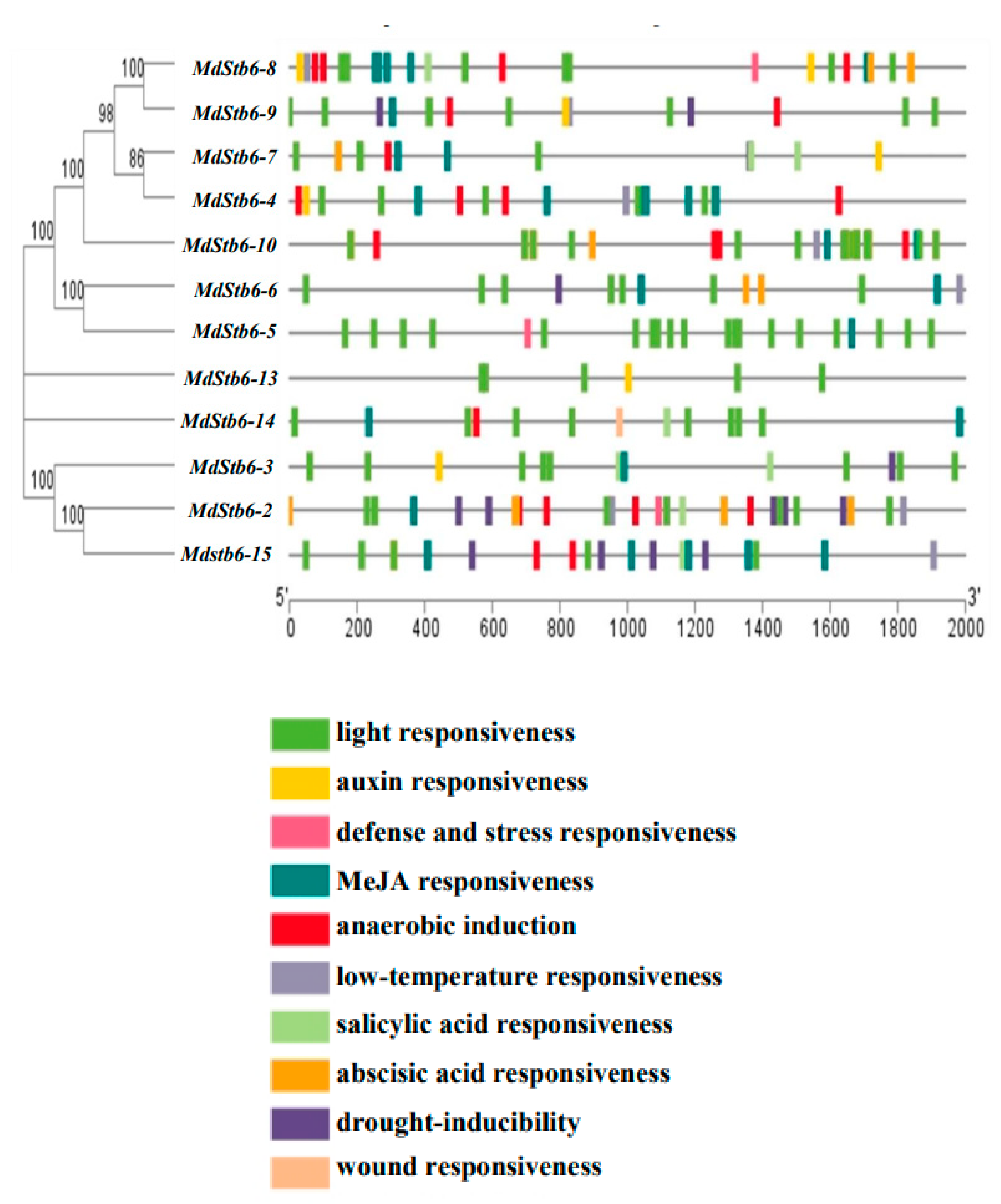

3.4. Cis-Elements in the Promoters of MdStb6 Homologs

Cis-acting elements in the promoters of genes regulate their transactivation by binding to transactivating factors, which in turn affect gene expression. The promoters of 12 genes, with the exceptions of MdStb6-1, MdStb6-11 and MdStb6-12, were analyzed. Light- and MeJA-responsive elements were extensively present in the promoter regions of the 12 genes (

Figure 4). Cis-elements respond to biotic and abiotic stresses such as low temperatures, anaerobic oxygen, drought- and plant defense-related hormones (

Figure 4).

MdStb6-2, MdStb6-5, and MdStb6-8 all contained defense and stress-responsive elements; MdStb6-1, MdStb6-2, MdStb6-4, MdStb6-6, MdStb6-7, MdStb6-8, MdStb6-10, and MdStb6-15 contained low-temperature response elements; and MdStb6-9, MdStb6-6, MdStb6-3, MdStb6-2 and MdStb6-15 contained drought-inducible response elements.

MdStb6-4, MdStb6-7, MdStb6-8, MdStb6-9, MdStb6-10, MdStb6-14, MdStb6-15 and MdStb6-2 contained low oxygen-induced elements (

Figure 4).

MdStb6-8, MdStb6-7, MdStb6-14, MdStb6-3, MdStb6-2, and MdStb6-15 contained SA-responsive elements; MdStb6-8, MdStb6-7, MdStb6-10, MdStb6-6, and MdStb6-2 contained abscisic acid-responsive elements; and MdStb6-14 contained wound-responsive elements (

Figure 4).

Auxin-responsive elements were present in MdStb6-4, MdStb6-7, MdStb6-8, MdStb6-9, MdStb6-3 and MdStb6-13, and wound-responsive elements were identified in MdStb6-14 (

Figure 4).

These results suggest the close involvement of homologous genes in counteracting biotic and abiotic stresses and could be involved in regulating growth and development because of the existence of the cis-elements responding to light and auxin, the two necessary growth regulators.

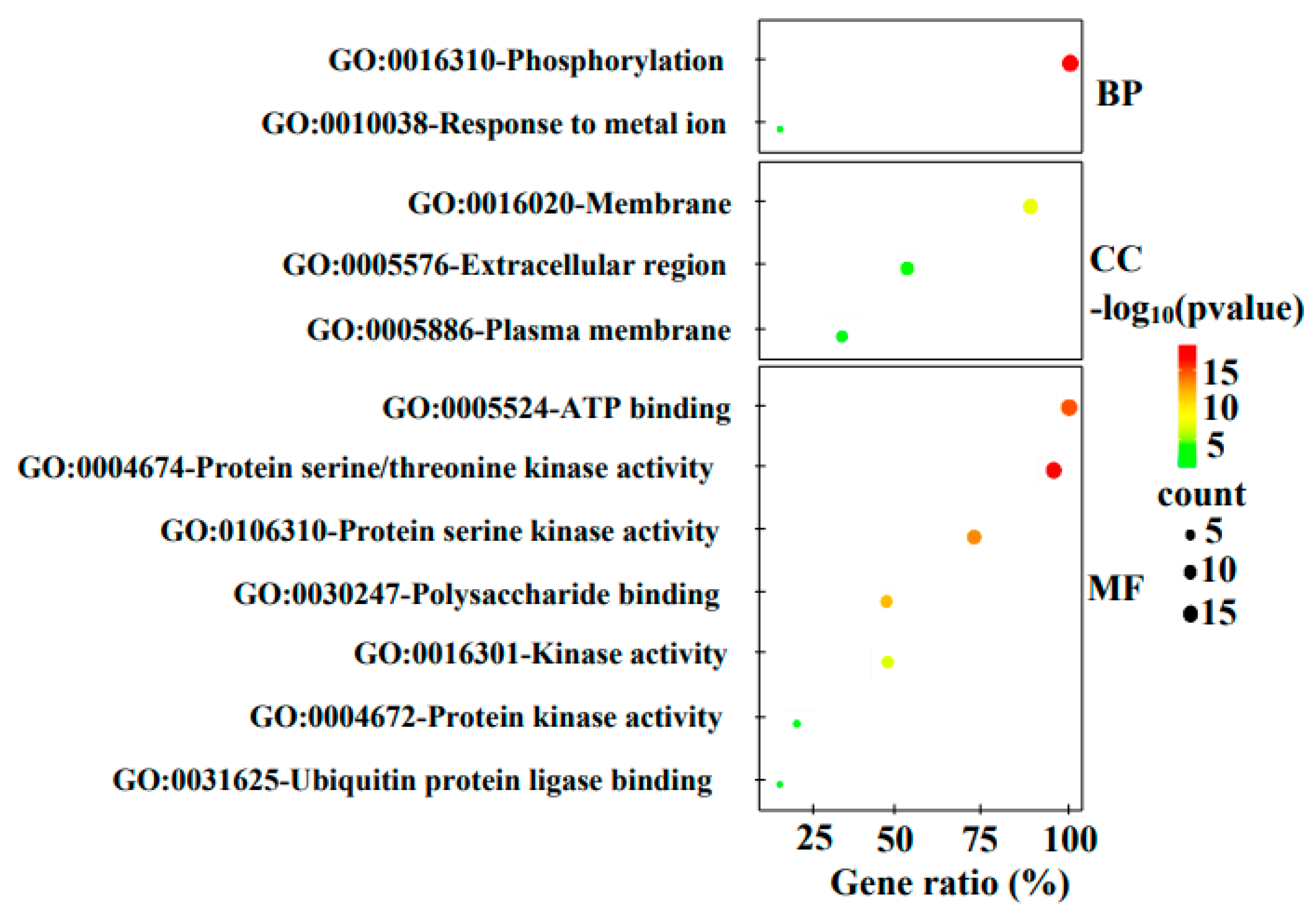

3.5. Gene Ontology (GO) Annotation

GO analysis revealed that all the homologous genes were involved in the physiological process of phosphorylation or were predicted to be capable of binding with ATP. This finding suggests that the encoded proteins have phosphorylation activity and are kinases (

Figure 5). All fifteen members were involved in the biological process of phosphorylation and were predicted to have ATP binding activity, and the encoded proteins, except MdStb6-6, were suggested have protein serine/threonine kinase activity, whereas MdStb6-6 was predicted to have serine kinase activity (

Figure 5,

Table 2). Seven genes, MdStb6-1, MdStb6-2, MdStb6-3, MdStb6-4, MdStb6-5, MdStb6-9 and MdStb6-10, were suggested to have polysaccharide-binding activity (

Table 2). All the genes except MdStb6-14 were suggested to encode membrane proteins. The extracellular regions encoded by 8 genes were predicted, and 7 genes were suggested to contain polysaccharide-binding sites (

Figure 5,

Table 2). MdStb6-13 and MdStb6-11 were suggested to be bound by E3 ubiquitin ligase, which is generally involved in modulating immune signaling (

Figure 5,

Table 2).

Therefore, the findings suggested the involvement of homologous genes in ligand perception and immune signaling regulation.

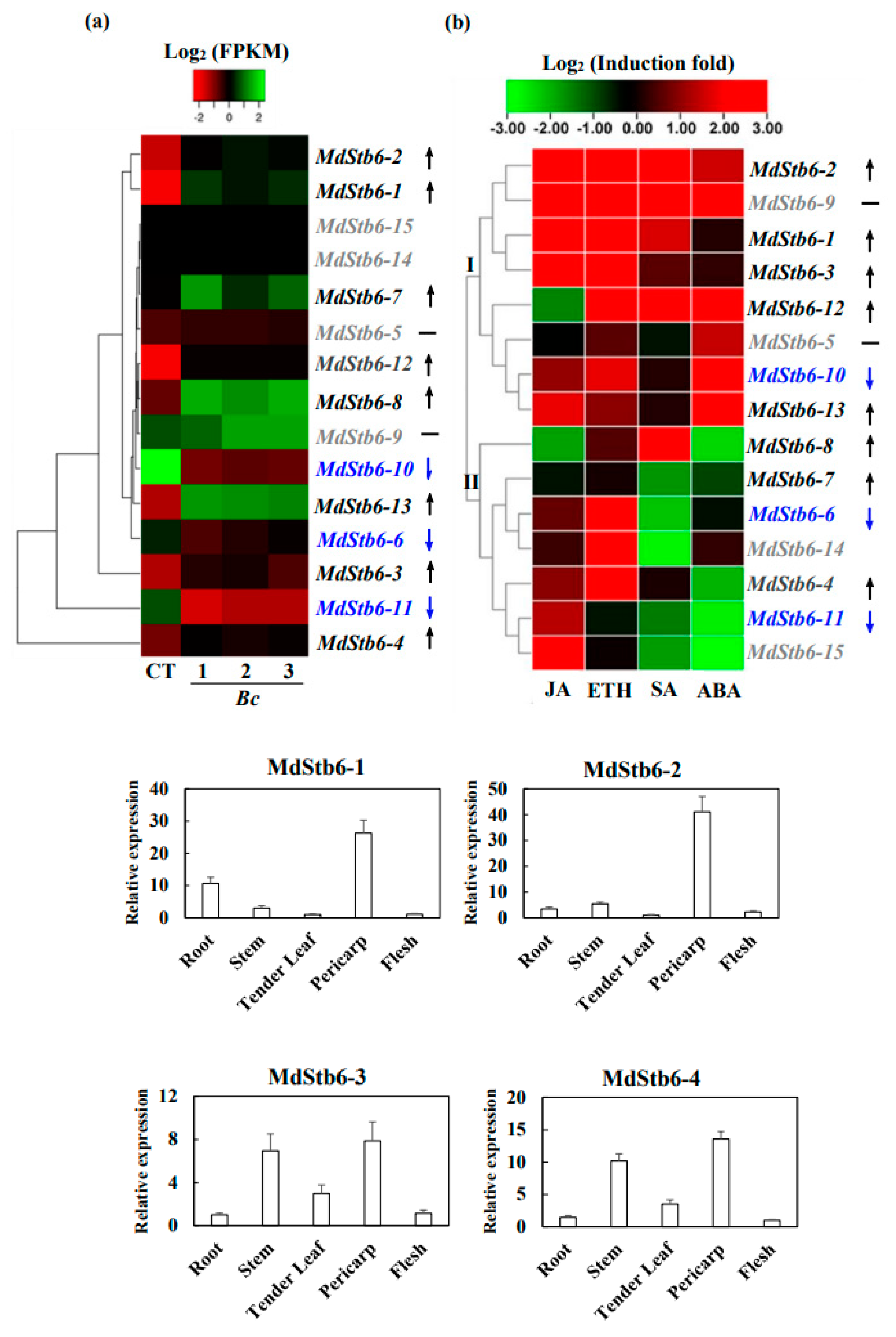

3.6. Response of MdStb6 Homologs to B. cinerea Infection and Defense-Related Plant Hormones and Their Expression Patterns in Different Tissues

SA, ABA, MeJA and ETH are basal defense regulators in plants. All the genes were responsive to defense-related plant hormones. They were divided into two clades. One is transcriptionally induced by all or nearly all the plant hormones, including MdStb6-1, MdStb6-2, MdStb6-3, MdStb6-9, MdStb6-12, MdStb6-5, MdStb6-10 and MdStb6-13and another one is specifically triggered by certain plant hormones, which were MdStb6-4, MdStb6-6, MdStb6-7, MdStb6-8, MdStb6-11, MdStb6-14 and MdStb6-15 (

Figure 6b). This finding highlights the different functions of the genes involved in immunity generation.

Significant transcriptional induction was shown for MdStb6-1, MdStb6-2, MdStb6-3, MdStb6-4, MdStb6-7, MdStb6-8, MdStb6-12 and MdStb6-13 in apple calli cells under

B. cinerea infection (

Figure 6a). Among them, MdStb6-1, MdStb6-2, MdStb6-3 and MdStb6-12 belong to the same cluster in phylogeny analysis and MdStb6-4, MdStb6-7, MdStb6-8, belong to another clade in phylogenetic analysis (

Figure 2d), indicating the involvement of the homolog genes in regulating the resistance to

B. cinerea infection.

MdStb6-7 expression was induced weakly by ethylene and MdStb6-4 was strongly induced by ETH and the comparatively weaker induction by MeJA. MdStb6-6 was in the same pattern with MdStb6-4 in responses to plant hormones, however, it was suppressed by

B. cinerea infection (

Figure 6a, b). Furthermore, no transcriptional response to

B. cinerea was shown for MdStb6-5, the gene in the same branch with MdStb6-6 and having the identity of 92.23% (

Figure 2d,

Table S1). It strongly indicates the functional divergence of the homologous genes in regulating the immune signaling. MdStb6-13 and MdStb6-10 demonstrate similar patterns in responding to plant defense-related hormones, however, the dramatic induction was shown for MdStb6-13 while MdStb6-10 was dramatically inhibited under

B. cinerea infection. MdStb6-11, MdStb6-14, and MdStb6-15 could be strongly triggered by MeJA, ETH or both. MdStb6-11 was suppressed by

B. cinerea infection and MdStb6-14 and MdStb6-15 show no responses to the pathogen infection. MdStb6-9, responding to all the plant hormones, shows no response to the pathogen infection, while MdStb6-8, which was in the same branch and has relatively lower identity of 43.12% with MdStb6-9, was dramatically induced under

B. cinerea infection.

The result suggests the different functionality of the homologous genes in regulating the immune signaling. The divergence of the homolog genes could be related to the immunity acquisition in plant.

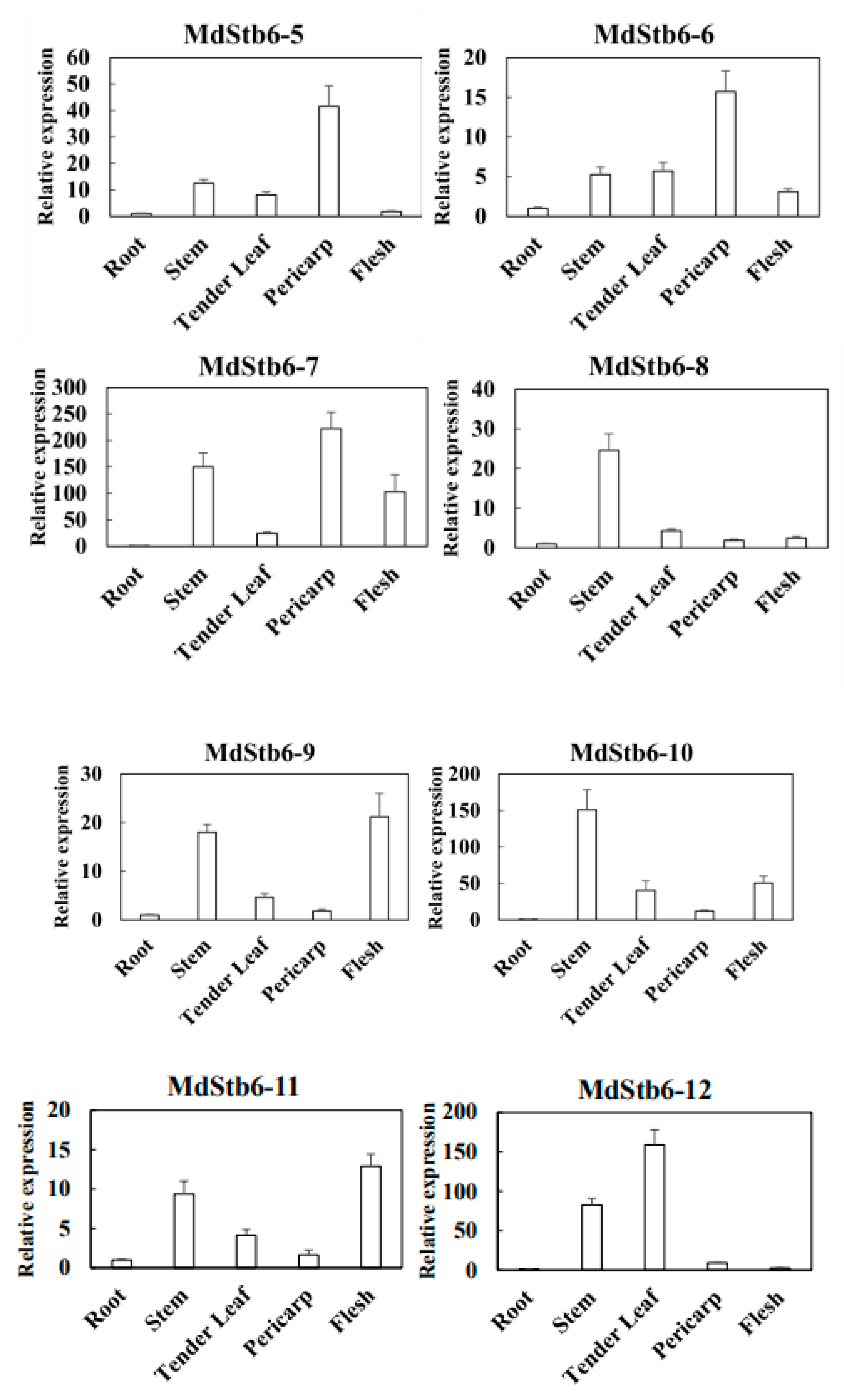

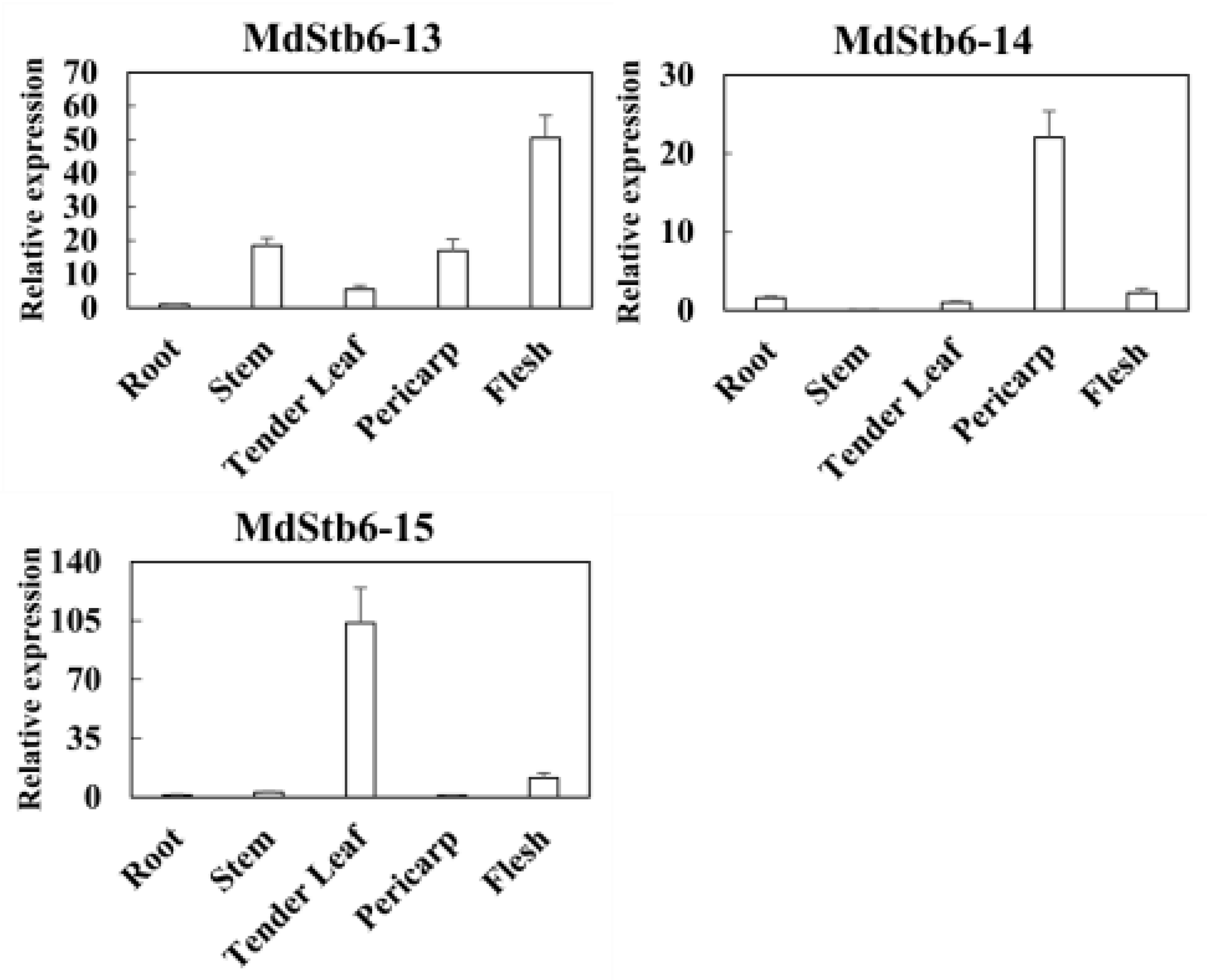

The pericarp, flesh, tender leaf and stems exhibited the highest transcription levels of the 15

MdStb6 homologs (

Figure 6c).

B. cinerea mainly infects the aerial parts of plants. The relatively high expression at potential pathogen infection sites suggests the close involvement of the homologous genes in conferring resistance against pathogen infection in different organs and in different types of cells.

3.7. MdStb6-13confers Resistance to B. cinerea Infection

MdStb6-13 exhibited the closest relationship with Stb6 according to phylogenetic analysis; it contained both GUB-WAK and WAK structural domains and could be strongly induced by MeJA, the plant hormone that contributes to resistance to necrotrophs [

7,

11,

12], and the expression of MdStb6-13 was elevated in response to

B. cinerea infection. On the basis of the results of both the bioinformatics analysis and the above experiments, we inferred that MdStb6-13 may confer resistance to

B. cinerea. The functional characterization of MdStb6-13 was subsequently carried out.

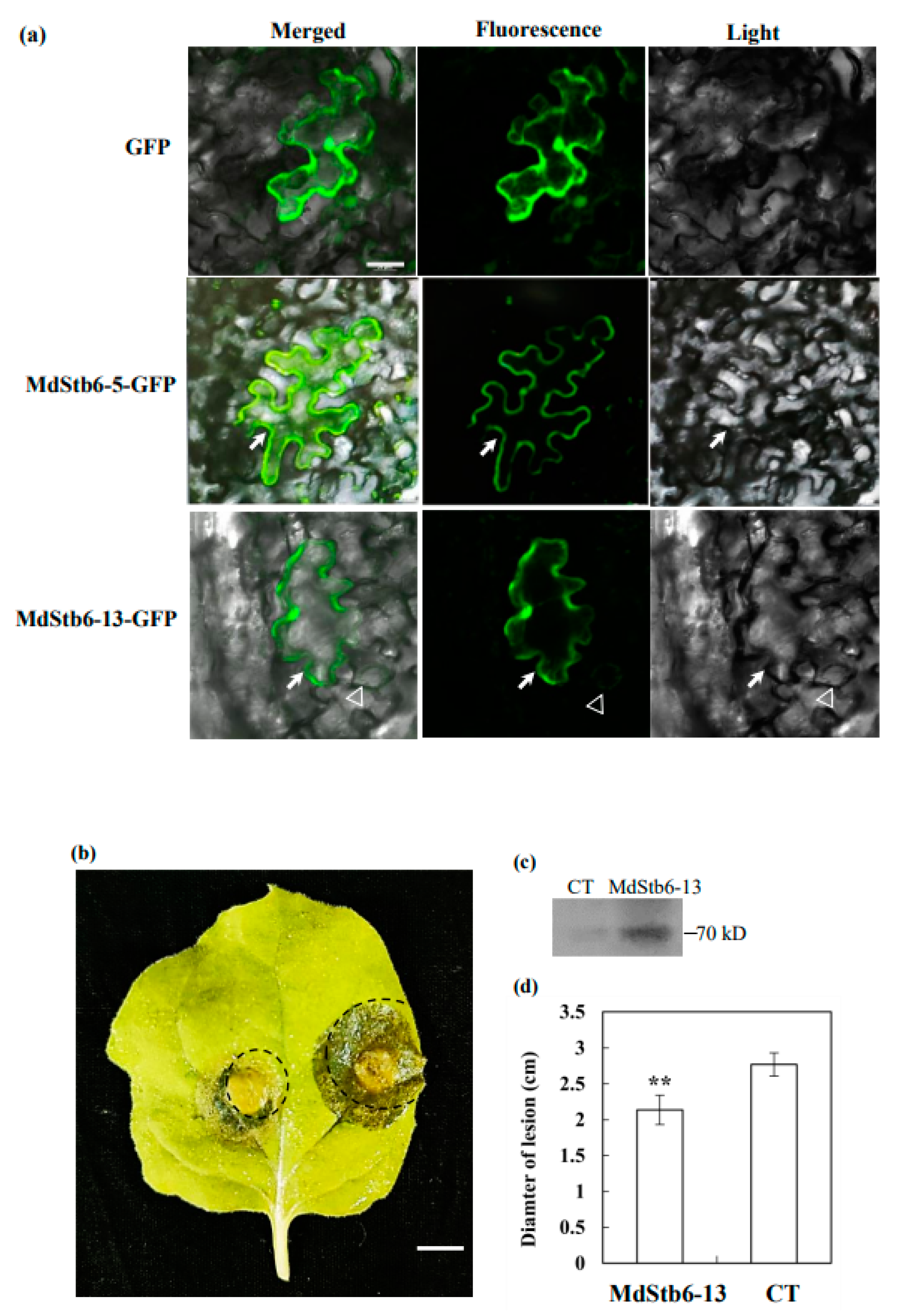

First, subcellular localization analysis demonstrated that MdStb6-13 and another gene in this clade, MdStb6-5, were located at the membrane or cell wall (

Figure 7a). Interestingly, MdStb6-13 was also identified in the periphery of guard cells (

Figure 7a).MdStb6-13 overexpression significantly enhanced resistance to

B.

cinerea infection. Transient overexpression of MdStb6-13 in tobacco leaves for three days significantly alleviated pathogen infection. In tobacco leaves, more severe leaf rot occurred on the control side when the empty vector was infiltrated during the experiment, and MdStb6-13 expression was detected. MdStb6-13 overexpression resulted in a 30% smaller area of pathogen infection than that in the control group. For visualization purposes, leaves that were thoroughly degraded and rotten were not selected herein, but severe deterioration and disease development was indeed deterred on the MdStb6-13 overexpression side (

Figure 7b-d).

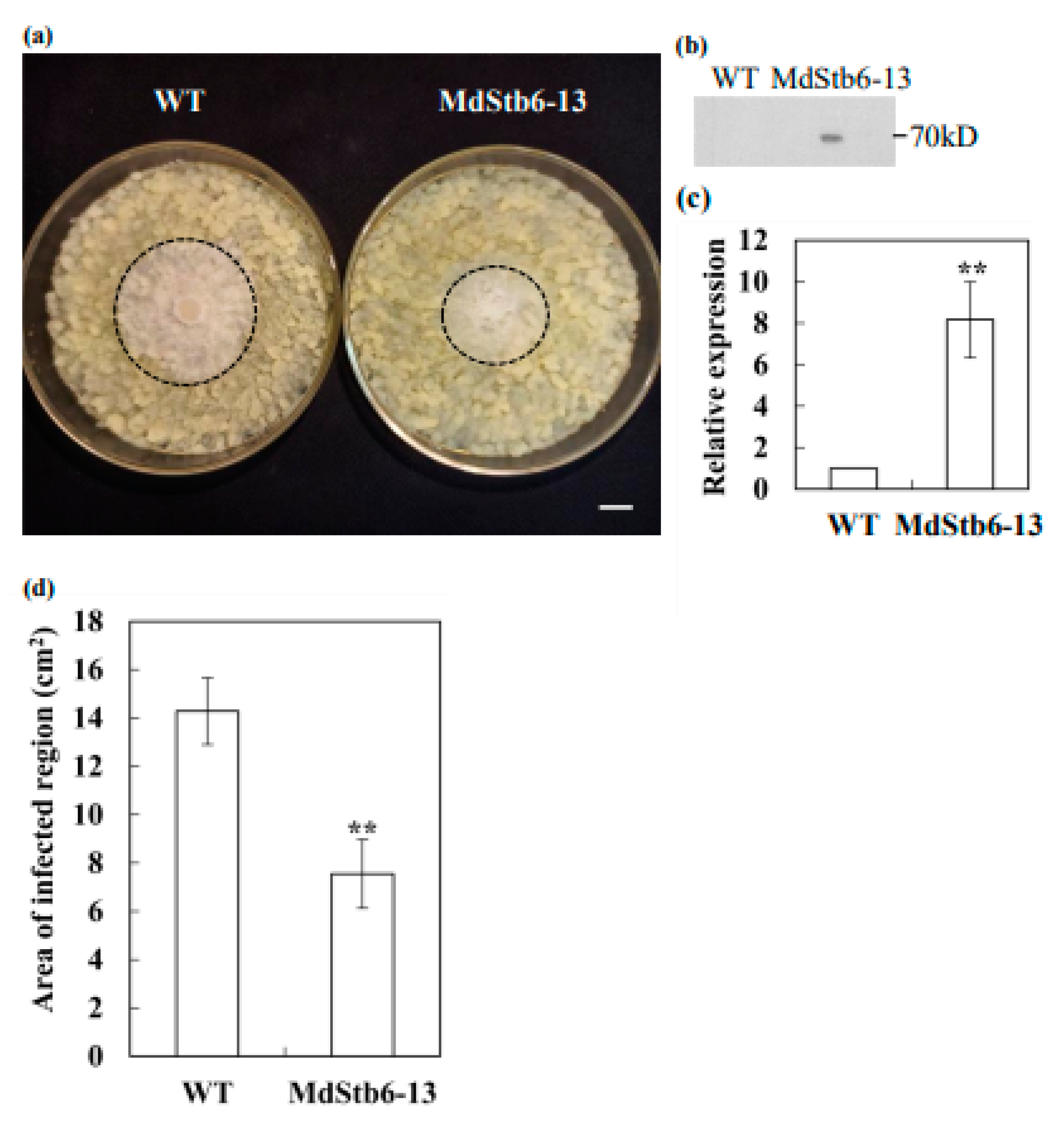

MdStb6-13-overexpressing apple calli were generated. MdStb6-13 expression in apple callus cells was detected using western blotting(

Figure 8b). MdStb6-13 transcription in transgenic apple callus cells was 8.17 times greater than that in the control (

Figure 8c). MdStb6-13 overexpression significantly enhanced resistance to

B. cinerea in apple callus cells, with the pathogen-infected area being only 52.9% of that in wild-type apple callus cells and

B. cinerea growth pronouncedly inhibited in MdStb6-13-overexpressing apple callus cells (

Figure 8a, d). These results strongly indicate that MdStb6-13 confers resistance to

B. cinerea.

3. Discussion

In our research, we identified 15 orthologs of Stb6, containing GUB-WAK, WAK and kinase domains, in the apple genome. A previous study identified 44 members of the WAK family in the apple genome [

28]. However, only two, MdStb6-7 (MDP0000198624) and MdStb6-13 (MDP0000152330), were shared. The two genes were in the same branch in the previous study but were divided into two clades in our investigation, suggesting that the genes identified in our investigation could be used to more finely differentiate the homologs (

Figure 2D). These genes were divided into two clades, and their transcription was induced by defensive plant hormones and pathogen infection. MdStb6-13 overexpression significantly contributed to resistance against

B. cinerea, indicating that the different functionalities of the homologous genes contribute to disease resistance in apple.

Recent reports have shown that the perception of AvrStb6 by Stb6 stimulates stomatal closure and blocks invasion via penetration into host cells[

32,

33]. In our investigation, MdStb6-13 was consistently located at the cell membrane or cell wall, and its transcription was strongly induced by ABA. This potent hormone has been shown to stimulate stomatal closure[

34]. MdStb6-13 was expressed at membrane or cell wall in guard cells (

Figure 7a), which strongly indicates the possible involvement of homologous genes in the perception of the pathogen. MdStb6-13 expression was strongly activated by MeJA, which confers resistance against

B. cinerea infection [

7,

8,

12]. MdStb6-13 may function downstream of MeJA signaling to confer resistance against

B. cinerea. On the other hand, MdStb6-13 may also potentiate MeJA signaling. JA signaling is mediated by the MKK7-MAPK signaling cascade in Arabidopsis [

35]. MdStb6-13 may potentiate MeJA signaling through the potentiation of MAPK activation to induce MeJA signaling. The strengthened MeJA signaling then further enhances the level of MdStb6-13 to further strengthen the immune signaling and it forms a positive regulatory route to amplify the immune signaling. Kinase or receptor-like kinases activated by plant defensive hormones are involved in initiating plant hormone signaling [

15,

36]. MdStb6-13 may function upstream of signal perception to initiate MeJA-mediated immune signaling to confer resistance against pathogen infection.

BIK1 functions downstream of pathogen perception and mediates signal perception at the membrane to initiate downstream activation of immune signaling by stimulating ROS, MeJA and SA via the phosphorylation of different substrates [

37,

38]. Our previous investigation revealed that overexpression of MdBIK1-2 (MDP0000260352), the ortholog of BIK1 in Arabidopsis, significantly enhances resistance to

B. cinerea [

39], suggesting the conservation of the inductive immune signaling pathway in rosaceous plants. Therefore, MdStb6-13 may function upstream to initiate immune signaling in apple in response to pathogen infection.

Interestingly, auxin-responsive elements were identified in the regulatory regions of MdStb6-4, MdStb6-7, MdStb6-8, MdStb6-9, MdStb6-3 and MdStb6-13 (

Figure 4). The homologous genes may also function downstream of auxin signaling to confer resistance against pathogen infection. This finding is consistent with the finding that auxin generation and signaling contribute to resistance against necrotrophic pathogens [

40,

41]. Auxin can stimulate cell wall lignification and wound healing [

42,

43,

44]. Cell wall disassembly represents an important virulence strategy for quenching immune responses in host cells invaded by necrotrophic pathogens [

6,

45,

46,

47]. Auxin may confer resistance by strengthening cell wall strength via modification or promoting changes in the damaged cell wall to counteract the primary virulence strategy of the pathogen. It has been shown that ethylene confers resistance to

B. cinerea by promoting hydroxycinnamate and monolignol accumulation at the cell wall [

9]. ABA is also essential for wound healing [

44]. MdStb6-13 could be strongly activated by ABA. MdStb6-13 could also be involved in wound healing and promote auxin signaling to confer resistance to pathogen infection. A synergistic effect between auxin and JA in promoting resistance signaling has been suggested [

48].

Therefore, dual functions of the homologous genes in initiating immune signaling and their involvement in regulating plant growth, cell wall development and disease resistance are suggested. This finding is consistent with their homology with Xa4, which confers resistance against pathogen infection through reinforcement of the cell wall via stimulation of JA-isoleucine (JA-Ile) accumulation [

31]. PORK1, an ortholog of AtPEPR1 and AtPEPR2, which confer resistance to

B. cinerea, was recently shown to be involved in regeneration, a type of wound healing process, suggesting the importance of wound healing in resistance against pathogen infection [

20,

49]. MdStb6-1, MdStb6-2, and MdStb6-3 exhibited higher expression levels in pericarp cells with thicker cell walls, and MdStb6-12 and MdStb6-15 were expressed mainly in leaves and stems, while MdStb6-13 was expressed in flesh cells with relatively thin cell walls (

Figure 6c; [

50]). These findings suggest specific functions of the homologous genes in regulating cell growth and initiating immune signaling. The divergence of the homologous genes could also be related to their different functions in regulating plant growth and initiating immune responses.

The strong integrity of the cell wall, which physically blocks pathogen entry into the cell interior, prevents the full activation of immune signaling, and loss of cell wall integrity confers immunity against pathogen infection [

51,

52,

53,

54]. Therefore, how these two facets are balanced and coordinately regulated to achieve robust immune responses should be investigated further. The homologous genes may act cooperatively with different factors to regulate the two facets or with one factor to regulate the two facets in generating immunity against pathogen infection. Furthermore, because a relatively high content of lignin and other cell wall materials would negatively regulates fruit quality [

55,

56], investigating the functions of the homologous genes will not only provide novel information on the resistance mechanisms involved in apple but also be useful for the breeding of resistant apple cultivars with relatively high fruit quality, wherein the genes can be modified to improve cytoplasmic immune responses while reducing the resistance mediated by the physical barrier. Moreover, relatively high levels of auxin signaling promote vigorous vegetative apple plant growth [

57], the investigating of those genes could also be deployed to create resistant apple cultivars with ideal structures, as it has been shown in rice that overexpression of Xa4 results in a shortened height of rice culms [

31] and the possible involvement of the homologous genes in regulating plant growth and auxin signaling.

Summarily, our research identified 15 MdStb6 homolog genes in apple genome. The dual involvement of the homologous genes in initiating immune signaling and in regulating growth and development were suggested. MdStb6-13 was identified confer resistance to B. cinerea with the functions of other orthologs investigated further.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Identification of the MdStb6 Gene Family and Analysis of Its Physicochemical Properties

To identify the

Malus domestica Stb6 (MdStb6)genes, the wheat Stb6 (KY485204) sequence was used as a query to perform local BLASTp searches against the local BLAST databases of

Malus domestica via the BLAST tool BioEdit (

https://www.bioedit.com/login). All BLAST hits with E values >1.0 were removed, and using E-value cutoff of <1.0, all previously known MdStb6 genes were captured. After the acquisition of all the sequences below the cutoff value, the wheat Stb6 protein sequence was used as a query to search the domains by the hidden Markov model (HMM) in the InterPro databases (

http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/), a resource that allows functional analysis of protein sequences by classifying them into families and predicting the presence of domains and important sites [

58]. This analysis revealed the Stb6Pfam domains PF13947: GUB-WAK, PF14380:WAK, and PS50011:Protein kinase, and the genes obtained from the BLAST results were further checked using these three Pfam domains. A total of 15 members of the MdStb6 gene family were ultimately identified.

Gene characteristics, including chromosome location, length of the encoded protein sequence (length), protein molecular weight (MW), isoelectric point (pI), positive and negative chains (chain), prediction of subcellular localization, and location of the GUB-WAK or WAK domain and signal peptide, were analyzed (

Table 1). The chromosome location and chain were recorded from the GDR Database (

https://www.rosaceae.org/), the physical and chemical parameters (e.g., length, MW, and pI) were calculated using ExPASy (

https://web.expasy.org/protparam/), the subcellular localization was predicted via Plant-mPLoc (Plant-mPLoc server (sjtu.edu.cn) [

59], and the start and end locations of the key domains GUB-WAK and WAK were determined via InterPro (

http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/).

4.2. Analysis of MdStb6 Promoter Cis-Acting Elements

The 2000 bp sequences upstream of the ATG start codon of the cluster of genes encoding the MdStb6 family were extracted from the apple genome file using TBtools software as the promoter sequences and analyzed online by using PlantCARE (

http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/). MdStb6 promoter cis-acting elements were filtered, and the results of the analysis were collated and visualized by TBtools [

60]. The promoters of all the MdStb6 homologs, with the exceptions of MdStb6-1, MdStb6-11 and MdStb6-12, were identified in the apple genome.

4.3. Gene Structure, Motif Composition and Phylogenetic Analysis of MdStb6 Genes

The exon‒intron organization of the MdStb6 genes was determined by comparing the predicted coding sequences with their corresponding full-length sequences using the online program Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS,

http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn) [

61].

The MdStb6 family protein sequences were submitted to MEME (

https://meme-suite.org/meme/tools/meme).We generated 10 motifs, and each motif had a pvalue less than E-50. The generated related files were submitted to TBtools to generate the resulting images.

The deduced amino acid sequences of wheat, apple, rice and

Arabidopsis thaliana that were homologous to the wheat Stb6 gene sequence we used were obtained from UniProt (

https://www.uniprot.org/), GDR(

https://www.rosaceae.org/)andTAIR(https://www.arabidopsis.org/). 35 strawberrygenes, 60 peach genes, 2

Rosa chinensis genes, 1

Zea mays gene, 4 rice genes, 1 cotton gene, 5 Arabidopsis genes, 2 wheat genes and 5 tomato genes were identified. The phylogenetic tree was constructed via the neighbor‒joining (NJ) method by MEGA-X, and 1,000 repetitions of bootstrap tests were performed. The figure was prepared using Chiplot [

62]. The accession numbers of the genes used in the phylogenetic analysis are shown in the supplementary file in

Table S1.

4.4. Chromosomal Locations and Synteny Analysis of MdStb6 Genes

All the MdStb6 genes were mapped to apple chromosomes on the basis of physical location information from the apple genome database via the online program Map Gene2chromosome V2 (

http://mg2c.iask.in/mg2c_v2.0/). The multiple collinearity scan toolkit (MCScanX) was adopted to analyze the gene duplication events with the default parameters [

63].

TBtools was used to complete the covariance analysis.

4.5. Gene Ontology (GO) Annotation

The MdStb6 protein sequences were annotated using the Blast2GO program to assign GO terms (

http://amigo.geneontology.org/amigo/term). The GO analysis E value was 1.0E-0.6. GO terms were classified under three main categories: biological process, cellular component, and molecular function [

64].

4.6. Subcellular Localization

The expression vectors pCB0302-35S:MdStb6-5-GFP and pCB302-35S:MdStb6-13 were constructed by cloning MdStb6-13 and MdStb6-5 into the pC302 binary vector using BamHI and StuI. The expression vectors were subsequently transfected into Agrobacterium GV3101. Agrobacterium strains containing MdStb6-13-GFP or MdStb6-5-GFP, with GFP as the control, were infiltrated into the abaxial side of the leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana plants grown under a photoperiod of 16 h light/8 h dark at 28°C for 3 days. The fluorescence localization of epidermal cells was observed by a confocal laser scanning microscope (ZEISS, LSM880 Airyscan) after expression for 3 days.

4.7. RNA-seq Analysis of Stb6 Genes in Apple Calli Cells Under B. cinerea Infection

The tissue-cultured calli of the apple cultivar ‘Orin’ was used for B. cinerea infection. The apple calli were cultured in Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (0.4mg L-1 6-BA,1.5mg L-12,4-D,30 mg L-1 sucrose and 7.5mg L-1agar; pH 5.8-6.0; autoclaved at 121°Cfor 20 min) contained in a petri-dish (9 cm in diameter) for 2 weeks under the growth conditions of 24±0.5°C and 24 h of darkness (at a relative humidity of 60–75%).

B. cinerea B05.10 was cultured in potato dextrose agar medium and grown in darkness for 7 days. We infected the ‘Orin’ calli with the B. cinerea by placing a 0.5-cm-diameter agar disc containing B. cinerea mycelia at the center of the callus containing B. dothidea was placed at center of the callus cell-composed carpet to ensure the direct contact of the fungi with apple calli cells. After infection for 3 days, the apple calli cells surrounding the lesions region were collected, and the untreated calli served as the blank control.

Illumina RNA-seq data were used to study the expression patterns of the MdStb6 genes. Using the RNA-seq data, a heatmap of 15 MdStb6 genes, represented by FPKM values associated with the response to pathogen infection, was generated via Heatmapper. To render the data suitable for cluster display, absolute FPKM values were divided by the means of all of the values, and the ratios were log2 transformed. A heatmap was generated by loading the expression data into the website Heatmapper (

http://www.heatmapper.ca/).

4.8. Plant Hormone Responses Assay and Organ Specific Expression Detection

Isolated leaves were treated with 2.5 mM salicylic acid (SA), 0.05 mM methyl jasmonate (MeJA), 2.5 mM ethylene tetrachloride (ETH), or 50 μmol/L abscisic acid (ABA) and were sampled at 6 h.Isolated leaves treated with sterile water were used as controls, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C. Three biological replicates were performed for each treatment.

New roots (roots), stems of new shoots (stems), tender leaves, mature fruit pericarp (pericarp) and flesh were harvested from 10-year-old ‘Fuji’ apple trees that were grown in the orchard of Manzhuang town, Tai’an, Shangdong, China, for tissue-specific gene expression analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from the plant tissues via an OminiPlant RNA Kit (DNase I) (CWBIO, China), and the RNA concentration was determined via a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). One microgram of RNA was transcribed to first-strand complementary DNA via a First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT‒PCR) was used to measure the expression levels of the target genes. The 20 μL PCR mixture comprised 10 μL of Fast Start Universal SYBR® Green Master Mix (Roche, USA), 0.6 μL of each primer (10 mM), 2 μL of diluted cDNA, and 6.8 μL of PCR-grade H

2O and performed using a CFX96TM Real-time Detection System (Bio-Rad, USA). The following PCR program was used: predenaturation at 95°C for 10 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60 °C for 30 s; and a final melt cycle from 60 °C to 98°C. The PCR process was completed with a melting curve analysis program. The

Malus domestica actin gene was used as a standard control to quantify cDNA abundance. The primers used in the qRT‒PCR analyses are shown in

Table S2.

4.9. Gene Functions Characterization

Gene function characterization was first carried out via the tobacco leaf transient expression method, which was previously described by Popescu et al. (2009) [

65]. The PBI-Flag empty vector and PBI-35S-MdStb6-13-Flag gene expression vector were transformed into

Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 via cold shock transformation as described by Xin et al. [

50]. The colonies were confirmed by PCR. The correct transformants were inoculated in LB culture medium supplemented with kanamycin (50 mg/L), rifampicin (50 mg/L), MES (10 mM) or AS (0.5 mM) and incubated at 28°C and 220 rpm for 12 h. After centrifugation, the cells were resuspended and kept in darkness for 3 h. The suspension was infiltrated into tobacco leaves using a needleless 1 ml syringe. The right side of the tobacco leaf was injected with resuspended cells carrying the empty vector as a control, and the left side was injected with resuspended cells carrying the PBI-MdStb6-13-Flag gene expression vector. After 1 day of dark treatment and then incubation under normal light for 2 days,

B. cinerea B05.10 that had been cultured for 7 days in PDA plate were collected and inoculated into the left and right sides of the tobacco leaves using a 0.5-cm-diameter perforator. The symptoms of the tobacco leaves were observed after 3 days. The experiment was repeated three times.

The PBI121-MdStb6-13-Flag gene expression vector was transformed into

Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV4404. Apple calli cells ‘Orin’ that had been grown for 7 days were transformed [

50]. The agrobacteria-infected apple calli were grown in MS medium supplemented with carbenicillin and kanamycin for transgenic calli cells screening. Successfully transformed apple calli, as verified by western blot analysis, were used in the pathogen inoculation experiment. In the pathogen infection,

B. cinerea mycelia was inoculated into the apple calli cells grown in an antibiotic-free MS plate contained in a diameter of 9 cm petri-dish, followed by observation of disease symptom for 5 days [

50]. The experiment was repeated three times.

4.10. Statistic Analysis

A t test was used to identify significant differences between the control and experimental groups after the inoculation of tobacco leaves, as well as differences in the relative expression level of MdStb6-13and pathogen resistance in wild-type and transgenic apple calli.

5. Conclusions

In our research, 15 orthologs of Stb6 in the apple genome were identified, which were named MdStb6-1 to MdStb6-15. In the phylogenetic analysis, the genes were divided into two clades. All these genes were differentially regulated by plant defense-related hormones, including MeJA, SA, ethylene and ABA, and B. cinerea infection. Overexpression of MdStb6-13, which was induced by JA and ABA, significantly conferred resistance to B. cinerea, with the mechanisms of their involvement in modulating immune signaling discussed.

Our research suggests MdStb6 orthologs were important functional genes that could be involved in modulating immune signaling in apple, which provides novel information for understanding resistance mechanisms in the rosaceous evolutionarily highly developed perennial woody plant and the molecular basis for breeding apple resistance cultivars with higher fruit quality and ideal plant stature.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: The identity between the genes in MdStb6 homologs in apple genome; Table S2: Accession numbers of the genes used in the phylogenetic analysis; Table S3: Primers used in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W. and P.Q.; methodology, P.Q., X.L., S.Y., M.Z., M.L., F.L., W.Z., X.Z.; software, P.Q., X.L., X.W., S.W.; validation, P.Q., X.L., and S.W.; formal analysis, P.Q., S.W.; investigation, P.Q.; resources, S.W.; data curation, P.Q., S.W.; writing—original draft preparation, P.Q.; writing—review and editing, S.W.; visualization, P.Q.; supervision, X.C., S.W.; project administration, S.W.; funding acquisition, S.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation in China (Nos. 32372649, 31672136) and the National Key Research and Development Project (No. 2018YFD1000307). The APC was funded by No. 32372649.

Data Availability Statement

All the data from this study are presented in the manuscript and the supplementary materials.

Acknowledgments

We thank American Journal Experts (AJE) for editing the English language in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WAK |

Wall-associated receptor-kinase |

| WAKL |

WAK-like |

| GUB |

galacturonan-binding |

| JA |

Jasmonic acid |

| MeJA |

Methyl jasmonate |

| ETH |

Ethylene |

| SA |

Salicylic acid |

| ABA |

Abscisic acid |

References

- 7 Reasons Why Apples Are Good. Available online: https://health.clevelandclinic.org/benefits-of-apples (accessed on 7 August 2023).

- Abdelhalim, A.; Mazrou, Y.S.A.; Shahin, N.; El-kot, G.A.; Elzaawely, A.A.; Maswada, H.F.; Makhlouf, A.H.; Nehela, Y. Enhancing the storage longevity of apples: The potential of Bacillus subtilis and Streptomyces endus as preventative bioagents against post-harvest gray mold disease, caused by Botrytis cinerea. Plants 2024, 13, 1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Huang, Y.; Lian, S.; Saleem, M.; Li, B.; Wang, C. Improving the biocontrol efficacy of Meyerozyma guilliermondii Y-1 with melatonin against postharvest gray mold in apple fruit. Postharvest Biol Tec. 2021, 171, 11351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Cao, S.; Sun, J.; Hou, J.; Zhang, M.; Qin, Q.; Li, G. Sterol regulatory element-binding protein Sre1 mediates the development and pathogenicity of the grey mould fungus Botrytis cinerea. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Yang, Z.; Song, W.; Zhao, H.; Ye, Q.; Xu, H.; Hu, B.; Shen, D.; Dou, D. Biofumigation by mustard plants as an application for controlling postharvest gray mold in apple fruits. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Caseys, C.; Kliebenstein, D.J. Genetic and molecular landscapes of the generalist phytopathogen Botrytis cinerea. Mol Plant Pathol 2024, 25, e13404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomma, B.P.H.J.; Eggermont, K.; Penninckx, I.A.M.A.; Mauch-Mani, B.; Vogelsang, R.; Cammue, P.A.; Broekaert, W.F. Separate jasmonate-dependent and salicylate-dependent defense-response pathways in Arabidopsis are essential for resistance to distinct microbial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998, 95, 15107–15111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomma, B.P.H.J.; Eggermont, K.; Tierens, K.F.M.J.; Broekaert, W.F. Requirement of functional ethylene-insensitive 2 gene for efficient resistance of Arabidopsis to infection by Botrytis cinerea. Plant Physiol 1999, 121, 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, A.J.; Allwood, J.W.; Winder, C.L.; Dunn, W.B.; Heald, J.K.; Cristescu, S.M.; Sivakumaran, A.; Harren, F.J.M.; Mulema, J.; Denby, K.; et al. Metabolomic approaches reveal that cell wall modifications play a major role in ethylene-mediated resistance against Botrytis cinerea. Plant J 2011, 67, 852–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wei, T.; Yin, K.Q.; Chen, Z.; Gu, H.; Qu, L.J.; Qin, G. Arabidopsis RAP2.2 plays an important role in plant resistance to Botrytis cinerea and ethylene responses. New Phytol 2012, 195, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Mu, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Yu, H.; Huang, T.; He, Y.; Dai, S.; Meng, X. Multilayered synergistic regulation of phytoalexin biosynthesis by ethylene, jasmonate, and MAPK signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 3066–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, W.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L. Botrytis cinerea-induced F-box protein 1 enhances disease resistance by inhibiting JAO/JOX-mediated jasmonic acid catabolism in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant 2024, 17, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, S.; Plotnikova, J.M.; Lorenzo, G.D.; Ausubel, F.M. Arabidopsis local resistance to Botrytis cinerea involves salicylic acid and camalexin and requires EDS4 and PAD2,but not SID2, EDS5 or PAD4. Plant J 2003, 35, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veronese, P.; Nakagami, H.; Bluhm, B.; Abuqamar, S.; Chen, X.; Salmeron, J.; Dietrich, R.A.; Hirt, H.; Mengiste, T. The membrane-anchored BOTRYTIS-INDUCED KINASE1 plays distinct roles in Arabidopsis resistance to necrotrophic and biotrophic pathogens. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemann, S.; van der Linde, K.; Lahrmann, U.; Acar, B.; Kaschani, F.; Colby, T.; Kaiser, M.; Ding, Y.; Schmelz, E.; Huffaker, A.; et al. An apoplastic peptide activates salicylic acid signalling in maize. Nat Plants 2018, 4, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Fraiture, M.; Kolb, D.; Löffelhardt, B.; Desaki, Y.; Boutrot, F.F.G.; Tör, M.; Zipfel, C.; Gust, A.A.; Brunner, F. Arabidopsis RECEPTOR-LIKE PROTEIN30 and receptor-like kinase SUPPRESSOR OF BIR1-1/EVERSHED mediate innate immunity to necrotrophic fungi. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 4227–4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Kars, I.; Essenstam, B.; Liebrand, T.W.H.; Wagemakers, L.; Elberse, J.; Tagkalaki, P.; Tjoitang, D.; van den Ackerveken, G.; van Kan, J.A.L. Fungal endopolygalacturonases are recognized as microbe-associated molecular patterns by the Arabidopsis receptor-like protein RESPONSIVENESSTO BOTRYTIS POLYGALACTURONASES1. Plant Physiol 2014, 164, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, E.; Mise, K.; Takano, Y. RLP23 is required for Arabidopsis immunity against the grey mould pathogen Botrytis cinerea. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 13798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmerling, B.; Schwedt, A.; Rodriguez, P.; Mazzotta, S.; Frank, M.; Qamar, S.A.; Mengiste, T.; Betsuyaku, S.; Parker, J.E.; Müssig, C.; et al. The BRI1-associated kinase 1, BAK1, has a brassinolide-independent role in plant cell-death control. Curr Biol 2007, 17, 1116–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Liao, C.J.; Jaiswal, N.; Lee, S.; Yun, D.J.; Lee, S.Y.; Garvey, M.; Kaplan, I.; Mengistea, T. Tomato PEPR1 ORTHOLOG RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASE1 regulates responses to systemin, necrotrophic fungi, and insect herbivory. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 2214–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yu, H.; Voxeur, A.; Rao, X.; Rixon, R.A. FERONIA and wall-associated kinases coordinate defense induced by lignin modification in plant cell walls. Sci Adv 2023, 9, eadf7714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, J.B.; Rowles, T.; Schulz, W.; McNellis, T.M. Arabidopsis Wall-Associated Kinase 3 is required for harpin-activated immune responses. New Phytol 2024, 242, 853–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, T.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, S.; Guo, C.; Xu, L.; Liu, T.; Li, Y.; Fan, X.; et al. The ZmWAKL-ZmWIK-ZmBLK1-ZmRBH4 module provides quantitative resistance to gray leaf spot in maize. Nat Genet 2024, 56, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhou, L.; Jamieson, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Babilonia, K.; Shao, W.; Wu, L.; Mustafa, R.; Amin, I.; et al. The cotton wall-associated kinase GhWAK7A mediates responses to fungal wilt pathogens by complexing with the chitin sensory receptors. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 3978–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, S.; Savatin, D.V.; Sicilia, F.; Gramegna, G.; Cervone, F.; De Lorenzo, G. Oligogalacturonides: Plant damage-associated molecular patterns and regulators of growth and development. Front Plant Sci 2013, 4, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herold, L.; Ordon, J.; Hua, C.; Kohorn, B.D.; Nürnberger, T.; De Falco, T.A.; Zipfel, C. Arabidopsis WALL-ASSOCIATED KINASES are not required for oligogalacturonide-induced signaling and immunity. Plant Cell 2024, 37, koae317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Chen, M.; Da, L.; Su, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X. Comparative genomics analysis of WAK/WAKL family in Rosaceae identify candidate WAKs involved in the resistance to Botrytis cinerea. BMC Genomics 2023, 24, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, C.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Mao, J.; Chu, M.; Chen, B. Genome-wide annotation and expression responses to biotic stresses of the WALL-ASSOCIATED KINASE -RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASE (WAK-RLK) gene family in apple (Malus domestica). Eur J Plant Pathol 2019, 153, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Marcel, T.C.; Hartmann, F.E.; Ma, X.; Plissonneau, C.; Zala, M.; Ducasse, A.; Confais, J.; Compain, J.; Lapalu, N.; et al. A small secreted protein in Zymoseptoria tritici is responsible for avirulence on wheat cultivars carrying the Stb6 resistance gene. New Phytol 2017, 214, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saintenac, C.; Lee, W.S.; Cambon, F.; Rudd, J.J.; King, R.C.; Marande, W.; Powers, S.J.; Bergès, H.; Phillips, A.L.; Uauy, C.; et al. Wheat receptor-kinase-like protein Stb6 controls gene-for-gene resistance to fungal pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici. Nat Genet 2018, 50, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Cao, J.; Zhang, J.; Xia, F.; Ke, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xie, W.; Liu, H.; Cui, Y.; Cao, Y.; et al. Improvement of multiple agronomic traits by a disease resistance gene via cell wall reinforcement. Nat Plants 2014, 3, 17009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiasi Noei, F.; Imami, M.; Didaran, F.; Ghanbari, M.A.; Zamani, E.; Ebrahimi, A.; Aliniaeifard, S.; Farzaneh, M.; Javan-Nikkhah, M.; Feechan, A.; et al. Stb6 mediates stomatal immunity, photosynthetic functionality, and the antioxidant system during the Zymoseptoria tritici-wheat interaction. Front. Plant Sci 2022, 13, 1004691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alassimone, J.; Praz, C.; Lorrain, C.; De Francesco, A.; Carrasco-López, C.; Faino, L.; Shen, Z.; Meile, L.; Sánchez-Vallet, A. The Zymoseptoria tritici avirulence factor AvrStb6 accumulates in hyphae close to stomata and triggers a wheat defense response hindering fungal penetration. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 2024, 37, 432–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, P.K.; Dubeaux, G.; Takahashi, Y.; Schroeder, J.I. Signaling mechanisms in abscisic acid-mediated stomatal closure. Plant J 2021, 105, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, F.; Yoshida, R.; Ichimura, K.; Mizoguchi, T.; Seo, S.; Yonezawa, M.; Maruyama, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. The mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade MKK3-MPK6 is an important part of the jasmonate signal transduction pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 805–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Yang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Xie, Q.; Tian, X.; Zhou, J.M. BIK1 interacts with PEPRs to mediate ethylene-induced immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013, 110, 6205–6210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, N.K.; Nagalakshmi, U.; Hurlburt, N.K.; Flores, R.; Bak, A.; Sone, P.; Ma, X.; Song, G.; Walley, J.; Shan, L.; et al. The receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase BIK1localizes to the nucleus and regulates defense hormone expression during plant innate immunity. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; He, F.; Ning, Y.; Wang, G.L. Fine-tuning of RBOH-mediated ROS signaling in plant immunity. Trends Plant Sci 2020, 25, 1060–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. The regulation of receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase MdBIK1 in resistance to Botrytis cinerea and Botryosphaeria dothidea on apple. Master Thesis, Shandong Agricultural University, Tai’an, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Llorente, F.; Muskett, P.; Sánchez-Vallet, A.; López, G.; Ramos, B.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, C.; Jordá, L.; Parker, J.; Molina, A. Repression of the auxin responses pathway increases Arabidopsis susceptibility to necrotrophic fungi. Mol Plant 2008, 1, 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hu, Z.; Lei, C.; Zheng, C.; Wang, J.; Shao, S.; Li, X.; Xia, X.; Cai, X.; Zhou, J.; et al. A plant phytosulfokine peptide initiates auxin-dependent immunity through cytosolic Ca2+ signaling in tomato. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 652–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghelli, R.; Brunetti, P.; Napoli, N.; De Paolis, A.; Cecchetti, V.; Tsuge, T.; Serino, G.; Matsui, M.; Mele, G.; Rinaldi, G.; et al. A newly identified flower-specific splice variant of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR8 regulates stamen elongation and endothecium lignification in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 620–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Cai, C.; Zhu, Q. Auxin response factors fine-tune lignin biosynthesis in response to mechanical bending in bamboo. New Phytol 2024, 241, 1161–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Dong, C.; Wu, Y.; Fu, S.; Tauqeer, A.; Gu, X.; Li, Q.; Niu, X.; Liu, P.; Zhang, X.; et al. The JA-to-ABA signaling relay promotes lignin deposition for wound healing in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant 2024, 17, 1594–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantu, D.; Vicente, A.R.; Greve, L.C.; Dewey, F.M.; Bennett, A.B.; Labavitch, J.M.; Powell, A.L.T. The intersection between cell wall disassembly, ripening, and fruit susceptibility to Botrytis cinerea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008, 105, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, C.J.; Van Den Abeele, C.; Ortega-Salazar, I.; Papin, V.; Adaskaveg, J.A.; Wang, D.; Casteel, C.L.; Seymour, G.B.; Blanco-Ulate, B. Host susceptibility factors render ripe tomato fruit vulnerable to fungal disease despite active immune responses. J Exp Bot 2021, 72, 2696–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, C.J.; Adaskaveg, J.A.; Mesquida-Pesci, S.D.; Ortega-Salazar, I.B.; Pattathil, S.; Zhang, L.; Hahn, M.G.; van Kan, J.A.L.; Cantu, D.; Powell, A.L.T.; et al. Botrytis cinerea infection accelerates ripening and cell wall disassembly to promote disease in tomato fruit. Plant Physiol 2023, 191, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Yan, J.; Li, Y.; Jiang, H.; Sun, J.; Chen, Q.; Li, H.; Chu, J.; Yan, C.; Sun, X.; et al. Arabidosis thaliana plants differentially modulate auxin biosynthesis and transport during defense responses to the necrotrophic pathogen Alternaria brassicicola. New Phytol 2012, 195, 872–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhai, H.; Wu, F.; Deng, L.; Chao, Y.; Meng, X.; Chen, Q.; Liu, H.; Bie, X.; Sun, C.; et al. Peptide REF1 is a local wound signal promoting plant regeneration. Cell 2024, 187, 3024–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Zhang, R.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Qi, P.; Wang, L.; Wu, S.; Chen, X. Extracellular and intracellular infection of Botryosphaeria dothidea and resistance mechanism in apple cells. Hortic Plant J 2023, 28, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Feechan, A.; Pedersen, C.; Newman, M.A.; Qiu, J.L.; Olesen, K.L.; Thordal-Christensen, H. A SNARE-protein has opposing functions in penetration resistance and defence signalling pathways. Plant J 2007, 49, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Blanco, C.; Feng, D.X.; Hu, J.; Sánchez-Vallet, A.; Deslandes, L.; Llorente, F.; Berrocal-Lobo, M.; Keller, H.; Barlet, X.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, C.; et al. Impairment of cellulose synthases required for Arabidopsis secondary cell wall formation enhances disease resistance. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 890–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassot, C.; Nawrath, C.; Métraux, J.P. Cuticular defects lead to full immunity to a major plant pathogen. Plant J 2007, 49, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipka, V.; Dittgen, J.; Bednarek, P.; Bhat, R.; Wiermer, M.; Stein, M.; Landtag, J.; Brandt, W.; Rosahl, S.; Scheel, D.; et al. Pre- and postinvasion defenses both contribute to nonhost resistance in Arabidopsis. Science 2005, 310, 1180–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Eom, S.H. Regulation of anthocyanin and lignin contents in postharvest ‘Fuji’ apple irradiated with UV-B. Sci Hortic 2023, 322, 112428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Sun, M.; Yao, J.L.; Liu, X.; Xue, Y.; Yang, G.; Zhu, R.; Jiang, W.; Wang, R.; Xue, C.; et al. Auxin inhibits lignin and cellulose biosynthesis in stone cells of pear fruit via the PbrARF13-PbrNSC-PbrMYB132 transcriptional regulatory cascade. Plant Biotechnol J 2023, 21, 1408–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Wan, S.; Huang, Y.; Li, X.; Jiao, T.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, B.; Zhu, L.; Ma, F.; Li, M. The transcription factor MdBPC2 alters apple growth and promotes dwarfing by regulating auxin biosynthesis. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 585–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.L.; Attwood, T.K.; Babbitt, P.C.; Blum, M.; Bork, P.; Bridge, A.; Brown, S.D.; Chang, H.Y.; El-Gebali, S.; Fraser, M.I.; et al. InterPro in 2019: Improving coverage, classification and access to protein sequence annotations. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, D351–D360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, K.C.; Shen, H.B. Plant-mPLoc: A top-down strategy to augment the power for predicting plant protein subcellular localization. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Jin, J.; Guo, A.Y.; Zhang, H.; Luo, J.; Gao, G. GSDS 2.0: An upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 2014, 31, 1296–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Chen, Y.; Cai, G.; Cai, R.; Hu, Z.; Wang, H. Tree visualization by one table (tvBOT): A web application for visualizing, modifying and annotating phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, W587–W592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Bowers, J.E.; Wang, X.; Ming, R.; Alam, M.; Paterson, A.H. Synteny and collinearity in plant genomes. Science 2008, 320, 486–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conesa, A.; Götz, S. Blast2GO: A comprehensive suite for functional analysis in plant genomics. Int J Plant Genomics 2008, 2008, 619832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, S.C.; Popescu, G.V.; Bachan, S.; Zhang, Z.; Gerstein, M.; Snyder, M.; Dinesh-Kumar, S. MAPK target networks in Arabidopsis thaliana revealed using functional protein microarrays. Genes Dev 2009, 23, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Secondary structure of MdStb6 family proteins.

Figure 1.

Secondary structure of MdStb6 family proteins.

Figure 2.

Gene structure, architecture of conserved protein motifs and phylogenetic analysis of MdStb6 homologous genes. (a) MdStb6 gene structure. The yellow boxes indicate exons, and the black lines indicate introns; (b) Conserved motifs inMdStb6 proteins. Pkinase indicates kinase domain; WAK indicates the WAK domain; and UN indicates an unknown function motif; (c) Sequence logos of each motif shown in (b); (c) Phylogenetic analysis of 15 MdStb6 genes with homologs in wheat (2), tomato (5), rice (5), peach (60), Arabidopsis (5), cotton (1), rose (2), strawberry (35), and maize (4). The tree was constructed via the neighbor‒joining (NJ) method with MEGA11.0. Bootstrap support values from 1,000 repetitions are represented by a color gradient. Md, Malus domestica; Ta, Triticum aestivum; Sl, Solanum lycopersicum; Os, Oryza sativa; Pp, Prunus persica; At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Gh, Gossypium hirsutum; Rc, Rosa chinensis; Fv, Fragaria vesca; Zm, Zea mays.

Figure 2.

Gene structure, architecture of conserved protein motifs and phylogenetic analysis of MdStb6 homologous genes. (a) MdStb6 gene structure. The yellow boxes indicate exons, and the black lines indicate introns; (b) Conserved motifs inMdStb6 proteins. Pkinase indicates kinase domain; WAK indicates the WAK domain; and UN indicates an unknown function motif; (c) Sequence logos of each motif shown in (b); (c) Phylogenetic analysis of 15 MdStb6 genes with homologs in wheat (2), tomato (5), rice (5), peach (60), Arabidopsis (5), cotton (1), rose (2), strawberry (35), and maize (4). The tree was constructed via the neighbor‒joining (NJ) method with MEGA11.0. Bootstrap support values from 1,000 repetitions are represented by a color gradient. Md, Malus domestica; Ta, Triticum aestivum; Sl, Solanum lycopersicum; Os, Oryza sativa; Pp, Prunus persica; At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Gh, Gossypium hirsutum; Rc, Rosa chinensis; Fv, Fragaria vesca; Zm, Zea mays.

Figure 3.

Chromosomal location and syntenic covariance of the MdStb6 genes. (a) Chromosomal locations of the MdStb6 genes. The scale on the left is in megabases (Mb); (b) Covariance analysis. Schematic representation of the chromosomal distribution and interchromosomal relationships of the MdStb6 genes. The gray lines indicate all synteny blocks in the apple genome, and the red lines indicate duplicated MdStb6 gene pairs. The chromosome number is indicated in the middle of each chromosome.

Figure 3.

Chromosomal location and syntenic covariance of the MdStb6 genes. (a) Chromosomal locations of the MdStb6 genes. The scale on the left is in megabases (Mb); (b) Covariance analysis. Schematic representation of the chromosomal distribution and interchromosomal relationships of the MdStb6 genes. The gray lines indicate all synteny blocks in the apple genome, and the red lines indicate duplicated MdStb6 gene pairs. The chromosome number is indicated in the middle of each chromosome.

Figure 4.

Cis-elements in the promoters of MdStb6homologs.

Figure 4.

Cis-elements in the promoters of MdStb6homologs.

Figure 5.

Gene ontology (GO) analysis of MdStb6 homologs genes. Bubble colors are indicative of statistical significance, with redder shades representing a smaller P value, and greener shades representing a larger P value. The larger the bubble is, the more genes it contains. BP: biological process, CC: cellular compartment, MF: molecular function.

Figure 5.

Gene ontology (GO) analysis of MdStb6 homologs genes. Bubble colors are indicative of statistical significance, with redder shades representing a smaller P value, and greener shades representing a larger P value. The larger the bubble is, the more genes it contains. BP: biological process, CC: cellular compartment, MF: molecular function.

Figure 6.

Response of MdStb6 homolog genes to defense-related plant hormones and B. cinerea infection and their expression levels in different organs. (a) Expression of MdStb6 homolog genes in control and B. cinerea infected apple calli cells. FPKM values of the MdStb6 genes were log2 transformed, and a heatmap was constructed via the online program Heatmapper. Three repeats are shown for Bc-infected apple calli, and the average value is shown for the control without pathogen infection. The numbers below the heatmap indicate the three repeats. Bc: Botrytis cinerea. CT: control; (b) Expression of the cluster of genes in response to defense-related plant hormones. The fold induction of transcriptional regulation was measured by real-time quantitative PCR. In (a) and (b), the upper- and down-pointing arrows indicate the transcriptional increased and reduced genes under B. cinerea infection. The genes inhibited by the pathogen infection were shown in blue characters. The horizontal line indicates the genes without significant changes under the pathogen infection with the genes name shown in gray color. The gene with only name show gray indicates the genes not detected in apple calli; (c) Expression of MdStb6 homolog genes in the pericarp, flesh, leaf and stem. The samples were collected and analyzed via qRT‒PCR. The Y-axis indicates the relative expression level of the gene.

Figure 6.

Response of MdStb6 homolog genes to defense-related plant hormones and B. cinerea infection and their expression levels in different organs. (a) Expression of MdStb6 homolog genes in control and B. cinerea infected apple calli cells. FPKM values of the MdStb6 genes were log2 transformed, and a heatmap was constructed via the online program Heatmapper. Three repeats are shown for Bc-infected apple calli, and the average value is shown for the control without pathogen infection. The numbers below the heatmap indicate the three repeats. Bc: Botrytis cinerea. CT: control; (b) Expression of the cluster of genes in response to defense-related plant hormones. The fold induction of transcriptional regulation was measured by real-time quantitative PCR. In (a) and (b), the upper- and down-pointing arrows indicate the transcriptional increased and reduced genes under B. cinerea infection. The genes inhibited by the pathogen infection were shown in blue characters. The horizontal line indicates the genes without significant changes under the pathogen infection with the genes name shown in gray color. The gene with only name show gray indicates the genes not detected in apple calli; (c) Expression of MdStb6 homolog genes in the pericarp, flesh, leaf and stem. The samples were collected and analyzed via qRT‒PCR. The Y-axis indicates the relative expression level of the gene.

Figure 7.

MdStb6-13 confers resistance to B. cinerea in Nicotiana benthamiana. (a) Subcellular localization of MdStb6-13 and MdStb6-5. The arrows and triangles indicate membrane or cell wall localization in the pavement cells and guard cells of the stomata, respectively. Scale bar=50 µm; (b) Phenotypes of a B. cinerea-infected tobacco leaf expressing MdStb6-13 (left) and in the control (right); Scale bar=1 cm; (c) MdStb6-13 expression detected by an anti-FLAG antibody in western blotting; (d) Statistical analysis of the diameter of the lesion. The results are shown as the average± SD. n=8. CT: control. MdStb6-13: MdStb6-13 overexpression.

Figure 7.

MdStb6-13 confers resistance to B. cinerea in Nicotiana benthamiana. (a) Subcellular localization of MdStb6-13 and MdStb6-5. The arrows and triangles indicate membrane or cell wall localization in the pavement cells and guard cells of the stomata, respectively. Scale bar=50 µm; (b) Phenotypes of a B. cinerea-infected tobacco leaf expressing MdStb6-13 (left) and in the control (right); Scale bar=1 cm; (c) MdStb6-13 expression detected by an anti-FLAG antibody in western blotting; (d) Statistical analysis of the diameter of the lesion. The results are shown as the average± SD. n=8. CT: control. MdStb6-13: MdStb6-13 overexpression.

Figure 8.

MdStb6-13 confers resistance to B. cinerea in apple. MdStb6-13 was transgenically overexpressed in apple calli, which were then infected with B. cinerea. (a) B. cinerea infection in wild type and MdStb6-13 overexpression apple calli cells; The circled area indicates the pathogen-infected region. Scale bar= 1 cm; (b) MdStb6-13 overexpression detected by western blotting; (c) The transcription level of MdStb6-13 in wild type and MdStb6-13 overexpression apple calli cells; (d) Statistical analysis of the lesion area in wild-type and MdStb6-13-overexpressing apple callus cells, respectively. The results are shown as the means ± SDs (n=6). The experiment was repeated three times. Scale bar: 1 cm. WT: wild-type ‘Orin’ apple callus cells; MdStb6-13: MdStb6-13-overexpressing apple callus cells.

Figure 8.

MdStb6-13 confers resistance to B. cinerea in apple. MdStb6-13 was transgenically overexpressed in apple calli, which were then infected with B. cinerea. (a) B. cinerea infection in wild type and MdStb6-13 overexpression apple calli cells; The circled area indicates the pathogen-infected region. Scale bar= 1 cm; (b) MdStb6-13 overexpression detected by western blotting; (c) The transcription level of MdStb6-13 in wild type and MdStb6-13 overexpression apple calli cells; (d) Statistical analysis of the lesion area in wild-type and MdStb6-13-overexpressing apple callus cells, respectively. The results are shown as the means ± SDs (n=6). The experiment was repeated three times. Scale bar: 1 cm. WT: wild-type ‘Orin’ apple callus cells; MdStb6-13: MdStb6-13-overexpressing apple callus cells.

Table 1.

Stb6 orthologs in the apple genome.

Table 1.

Stb6 orthologs in the apple genome.

| Gene name |

Locus name |

Identity with Stb6 |

Amino acids |

Molecular weight

(kD) |

pI |

Instability index |

GUB-WAK domain (start-end) |

WAK domain (start-end) |

Subcellular localization |

| MdStb6-1 |

MDP0000304127 |

35.01% |

650 |

72.7 |

6.06 |

36.00 |

34-105 |

203-252 |

Cytoplasm, Nucleus |

| MdStb6-2 |

MDP0000635134 |

33.23% |

574 |

63.9 |

5.21 |

39.42 |

36-100 |

180-247 |

Cytoplasm, Nucleus |

| MdStb6-3 |

MDP0000198217 |

35.88% |

616 |

67.9 |

6.41 |

38.56 |

32-101 |

- |

Cytoplasm, Nucleus |

| MdStb6-4 |

MDP0000319460 |

26.50% |

723 |

82.0 |

6.76 |

43.04 |

37-100 |

- |

Nucleus |

| MdStb6-5 |

MDP0000148991 |

31.48% |

604 |

68.8 |

8.51 |

39.56 |

24-90 |

- |

Cell membrane, Cytoplasm |

| MdStb6-6 |

MDP0000258582 |

31.54% |

604 |

68.5 |

8.65 |

37.97 |

25-91 |

- |

Cell membrane, Cytoplasm |

| MdStb6-7 |

MDP0000198624 |

30.35% |

621 |

69.7 |

8.35 |

44.2 |

51-114 |

- |

Cell membrane, Cytoplasm |

| MdStb6-8 |

MDP0000277334 |

24.90% |

705 |

80.4 |

6.90 |

55.91 |

102-163 |

- |

Nucleus |

| MdStb6-9 |

MDP0000282292 |

26.53% |

579 |

64.8 |

6.88 |

41.86 |

36-97 |

- |

Cell membrane, Cytoplasm, Nucleus |

| MdStb6-10 |

MDP0000272246 |

27.42% |

602 |

67.8 |

6.08 |

41.7 |

29-94 |

- |

Cytoplasm, Nucleus |

| MdStb6-11 |

MDP0000169760 |

23.12% |

610 |

68.9 |

8.44 |

39.39 |

39-102 |

- |

Cell membrane, Chloroplast, Cytoplasm, Nucleus |

| MdStb6-12 |

MDP0000193657 |

35.47% |

590 |

65.8 |

6.88 |

34.13 |

- |

143-192 |

Cell membrane, Cytoplasm, Nucleus |

| MdStb6-13 |

MDP0000152330 |

34.89% |

636 |

71.6 |

6.09 |

38.26 |

36-102 |

169-248 |

Nucleus |

| MdStb6-14 |

MDP0000147988 |

34.93% |

670 |

74.2 |

5.91 |

38.95 |

37-103 |

196-268 |

Nucleus |

| MdStb6-15 |

MDP0000190181 |

34.26% |

526 |

58.5 |

8.01 |

36.45 |

- |

92-158 |

Nucleus |

Table 2.

Genes in each category according to the GO analysis.

Table 2.

Genes in each category according to the GO analysis.

| Gene ontology analysis |

Numbers of MdStb6 homolog genes |

| Biological process |

|

| Phosphorylation |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 |

| Response to metal ion |

8, 12 |

| Cellular compartment |

|

| Membrane |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 |

| Extracellular region |

1, 3, 4, 6, 9, 10, 11, 13 |

| Plasma membrane |

4, 11, 13, 15 |

| Molecular function |

|

| ATP binding |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 |

| Protein serine/threonine kinase activity |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 |

| Protein serine kinase activity |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 10, 11, 13, 15 |

| Polysaccharide binding |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 9, 10 |

| Kinase activity |

2,3, 6, 7,9, 12, 15 |

| Protein kinase activity |

6, 9, 11 |

| Ubiquitin protein ligase binding |

11, 13 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).