1. Introduction

The isolation of Streptomyces avermitilis and the biotechnological development of its main bioactive compounds in Mexico and the rest of the world represents an important advance in the treatment of health problems in human medicine, veterinary medicine, and agriculture, where the strain’s bioactive potential will be fully exploited.

Streptomyces avermitilis it is a Gram positive soil actinobacteria that grows in long, branched, filamentous hyphae [

1]; it shows two types of mycelium, the first is an aerial mycelium with a cottony appearance of whitish to gray tones [

2,

3], the first usually appears during the exponential phase of bacterial growth, while the second mycelium is underground, which acts as support for the substrate and as a feeding conduit by taking the necessary nutrients provided by the culture medium. The distribution of

Streptomyces avermitilis in terrestrial soils is usually variable due to geographical conditions such as altitude, length; type, shape and use of land, ecosystem where it develops, pH, humidity and temperature [

4,

5].

Due to the complex and changing metabolism of

Streptomyces avermitilis, different morphotypes are presented, in which colonies of different sizes, variations in the amount of mycelium, and different diffusible pigments usually appear; this occurs mainly because the same strain of

Streptomyces avermitilis usually behaves differently due to the interaction of factors controlled in the laboratory such as temperature, humidity, and pH of the culture medium where the isolation is carried out [

6].

A key point in determining the morphological characteristics of the bacteria is the type of culture medium required to achieve correct isolation. Generally,

Streptomyces avermitilis is a strict microorganism to grow under laboratory conditions, since it needs to have a good source of carbon and nitrogen, a temperature between 25 °C and 32 °C [

7], in complete darkness and with an antifungal agent to avoid competition between fungi and other bacteria [

8].

Since

Streptomyces avermitilis is a microorganism that requires extreme care during its growth and isolation [

9], it is necessary to use appropriate seeding techniques that allow a correct expression of the strain. It is recommended to use techniques such as rod drag to observe the production of diffusible pigments [

10], while cross-streaking is applicable when purifying the culture [

11] or presenting a strain plate.

Based on the above, the isolation and purification of the Streptomyces avermitilis strain was sought during the four seasons of the year in four types of soils used for agricultural purposes (crops, dormant soil, silvopastoral system, and soil with high organic matter load). The variable of stress in complete darkness throughout the strain isolation process determined the key point for the production of secondary metabolites naturally, among which the diffusible pigments, different morphotypes of the same bacteria, and the production of ivermectin stand out. In addition, the growth behavior of Streptomyces avermitilis was monitored during the four seasons of the year, in order to analyze the possible adaptations and morphological characteristics that the bacteria presents to the different climatic conditions of each season.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Geographical Conditions

Four areas with different land uses were evaluated during the four seasons of the year (2024-2025) at the facilities of the Colegio de Postgraduados, Montecillo Campus, Texcoco de Mora, State of Mexico, Mexico; at the coordinates 19° 27’ 38 N and 98° 54’ 11” W at an altitude of 2250 m.a.s.l., with an average annual precipitation for the period 2024-2025 of 924.7 mm. Likewise, to monitor climatological conditions such as temperature, humidity and precipitation during the four seasons corresponding to the period 2024-2025, it was carried out based on the Merra-2 model on the weatherSpark.com platform with a 95% confidence level.

2.2. Collection and Processing of Soil Samples

The four soils selected for the isolation of Streptomyces avermitilis at the Colegio de Postgraduados, Montecillo Campus, were identified as: M1 (soil with oat and corn crops), M2 (restless soil), M3 (soil from a silvopastoral system), and M4 (dairy barn soil). From each area, five 1-kg soil samples were collected by zigzag sampling. Therefore, it was necessary to remove the first 15 cm of each soil with a sterile shovel. The samples were then placed inside previously identified polyethylene bags with a hermetic seal, Ziploc® type. The samples were stored in a cooler at 4 °C for transport to the Animal Nutrition Laboratory at the same institution. Each soil sample was mixed homogeneously on a stable, smooth surface to obtain a composite soil sample.

Subsequently, 2 g of soil were dissolved in 10 mL of sterile peptone water at 0.1%: 1.0 g/L of peptone (MCD Lab, Cat. 9072) and 8.5 g/L of NaCl (Merk, Cat. 21578) [

5,

12]. The samples were vortexed at maximum speed for 20 sec. Then, serial dilutions were made from 10

-1 to 10

-10; of these, the 10

-4, 10

-5 and 10

-6 dilutions were used for plate inoculation by dragging a rod [

13].

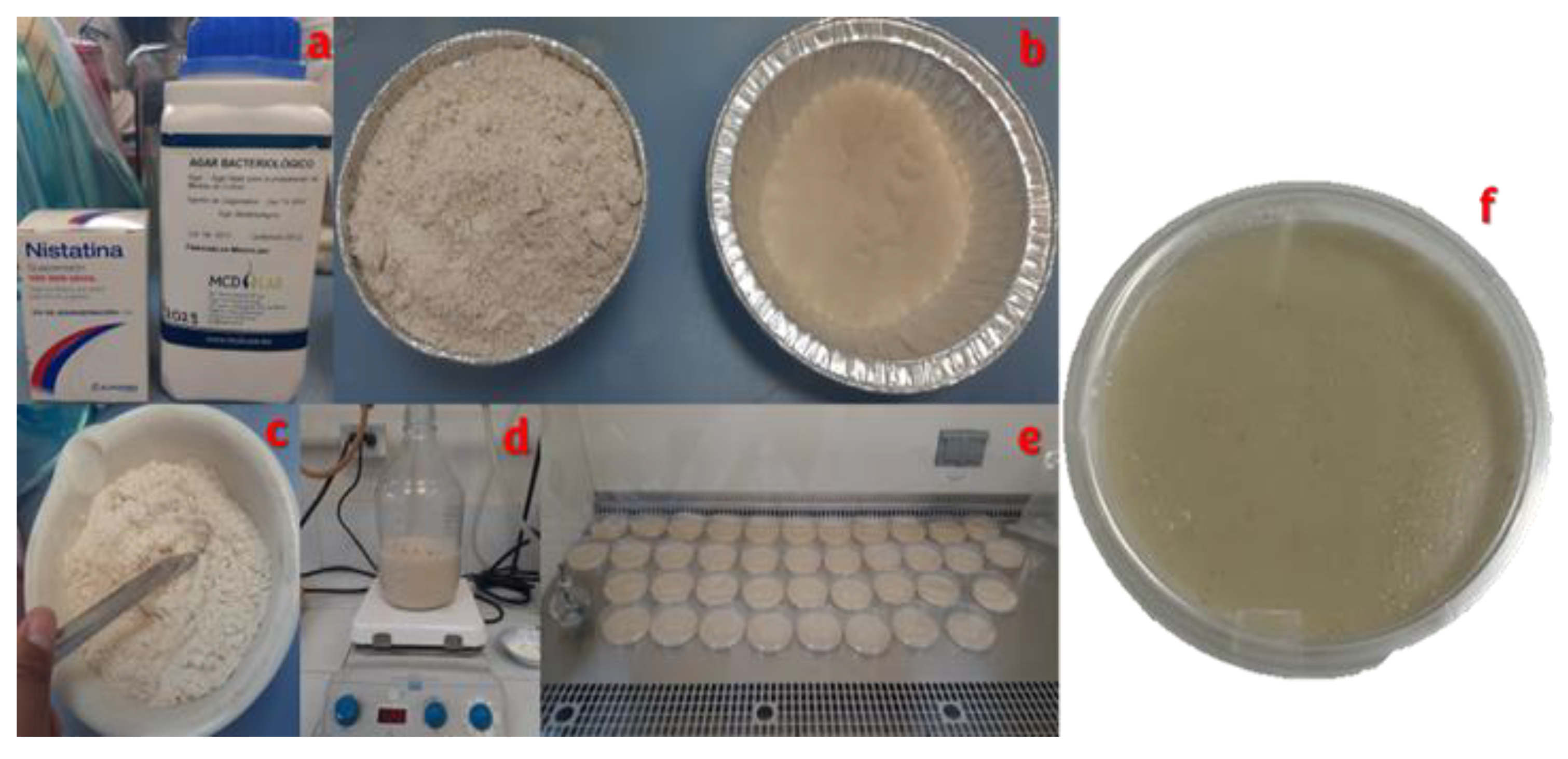

2.3. Preparation of the Specific Culture Medium: ISP-3 Oat Agar + Nystatin

The specific culture medium used in the isolation, purification and characterization of

Streptomyces avermitilis was ISP-3 oatmeal agar medium [

14,

15]: 60.0 g/L of previously sieved oatmeal and 12.5 g/L of bacteriological agar (MCD Lab, Cat. 9012) supplemented with 1% nystatin (100,000 IU/mL, Alpharma®) [

5,

10,

13,

16,

17]. The initial components were mixed homogeneously and added into a glass bottle with a screw cap with approximately 700 mL of distilled water at a temperature of 305 °C for 30 min on an electromagnetic grill (Velp scientifica ®, Arec. T) with a stirring speed at 1500 rpm. After 30 minutes, the nystatin was added and the flask was filled to 1 L with distilled water, waiting for complete dissolution. The mixture was then boiled for 1 min with all the components mixed, covered, and autoclaved at 121°C for 15 min.

Finally, the ISP-3 oatmeal agar culture medium supplemented with nystatin was poured into sterile 90 x 15 mm polystyrene Petri dishes (Klinicus®, Lot. 240903) inside a bacteriological hood type A2 (Thermo Scientific®, Model 1385 Rel 2,) previously sterilized with 96° ethyl alcohol (AZ®) and concentrated red antibenzyl (Farmacéuticos Altamirano®, Lot 24-333L).

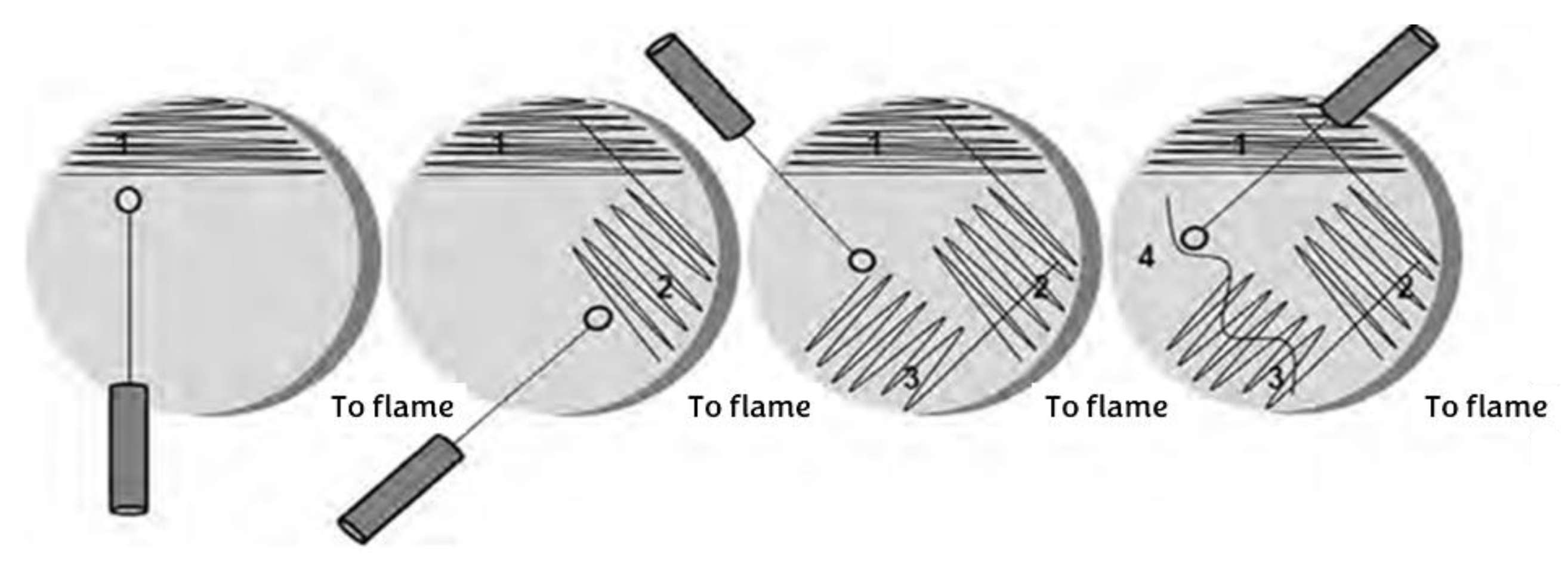

2.4. Initial Sowing and Strain Purification Streptomyces avermitilis on Plate

The initial seeding technique was by dipstick drag 100 µL of each of the working dilutions (10-4, 10-5 and 10-6) were placed in triplicate on the ISP-3 oatmeal agar plate. The Petri dishes were sealed with Parafilm and stacked so that the initial inoculum was absorbed by the culture medium (approximately 15 min). When the surface of the medium in the Petri dish was no longer moist, they were placed upside down in a 30 °C incubator in complete darkness for 10 days.

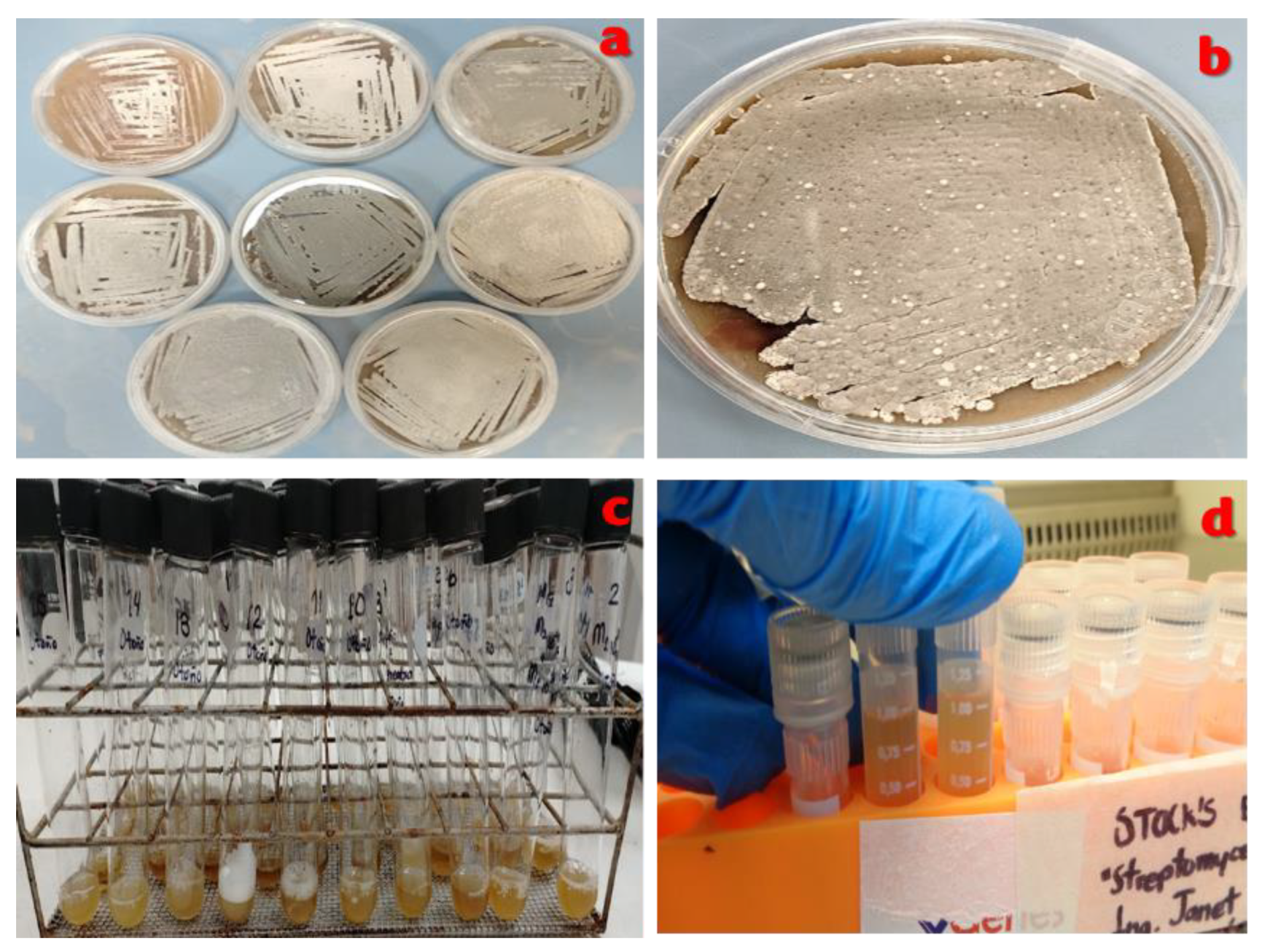

For pure culture in solid medium of

Streptomyces avermitilis, it was subcultured in the medium previously described (ISP-3 oatmeal agar + 1% nystatin) + 500 µL of α-amylase enzyme, with cross-streak seeding [

18] (

Figure 1).

The technique consists of taking a hoe from the microorganism you are working with, dividing the plate with the already gelled culture medium into four quadrants, and beginning to draw horizontal lines from left to right without lifting your hand. Rotate the plate 45° and repeat the previous procedure until all four quadrants are covered.

Pure culture (stock) in liquid medium was used Trypticasein Broth medium (CTS, DIBICO Mexico, Cat. 1186-E) supplemented with glucose: 17.0 g/L casein peptone, 3.0 g/L soy peptone, 5.0 g/L NaCl, 2.5 g K₂HPO₄ and 2.5 g/L glucose (Meyer, Cat. 1440). Stocks of Streptomyces avermitilis in liquid medium were incubated for 10 days in complete darkness at 30 °C.

Once the incubation process was completed, 850 µL of the liquid culture of Streptomyces avermitilis + 150 µL of sterile glycerol were taken, this mixture was stored in 2 mL tubes with screw caps (SSIBO, Cat. 50236), subsequently mixed in vortex for 30 sec, they were identified by soil type and by season of the year. Finally, they were placed in the freezer at -20 °C for preservation of the strain and future analysis.

During the 10 days of incubation, bacterial counts were performed daily. These data were useful for analyzing bacterial growth curves, the presence of aerial mycelium, and the production of diffusible pigments.

2.5. Catalase Test

A sample of the aerial mycelium of

Streptomyces avermitilis was taken on day 7 of incubation and placed on a slide, 250 µL of 3.5% surgical grade hydrogen peroxide (Alcomeh®) was added and spread over 80% of the surface of the slide. A positive reaction was considered when bubbling was observed on the sample [

19].

2.6. Gram Stain

A sample of a pure colony of Streptomyces avermitilis was mounted on a coverslip and diluted with sterile distilled water to form a smear. The smear was fixed by exposing it to a non-luminous burner flame for 30 sec. The smear was then stained with 200 µL of Gentian Violet (Hycel®, Cat. 6269) and left to act for 1 min. The stain was then rinsed with tap water and drained (drying with a cloth is not required) 200 µL of Gram-Iodine stain (Hycel®, Cat. 724) was then added, the stain was left to stand for 1 min, and the stain was then rinsed again under running tap water. Likewise, 200 µL of alcohol-acetone (Hycel®, Cat. 901) were added for 5 sec, washed directly under running water and allowed to drain. Finally, 200 µL of Safranina dye (Hycel®, Cat. 826) were added and left to stand for 1 min, washed under running tap water, dabbed dry with sterile sanita and observed under a microscope (Lobemed, CxL, USA) at 100X with immersion oil.

If the sample was stained pink/purple, the bacteria was Gram -, if the sample was stained blue/purple, the bacteria is Gram + [

20].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Each variable was analyzed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) using a completely randomized block design (four blocks: seasons, four treatments: M1, M2, M3, and M4, and three replicates). An analysis of variance (ANOVA), normality test, and slope homogeneity test were performed on the data; the means by treatment and block were compared using the Tukey test (α=0.05).

3. Results

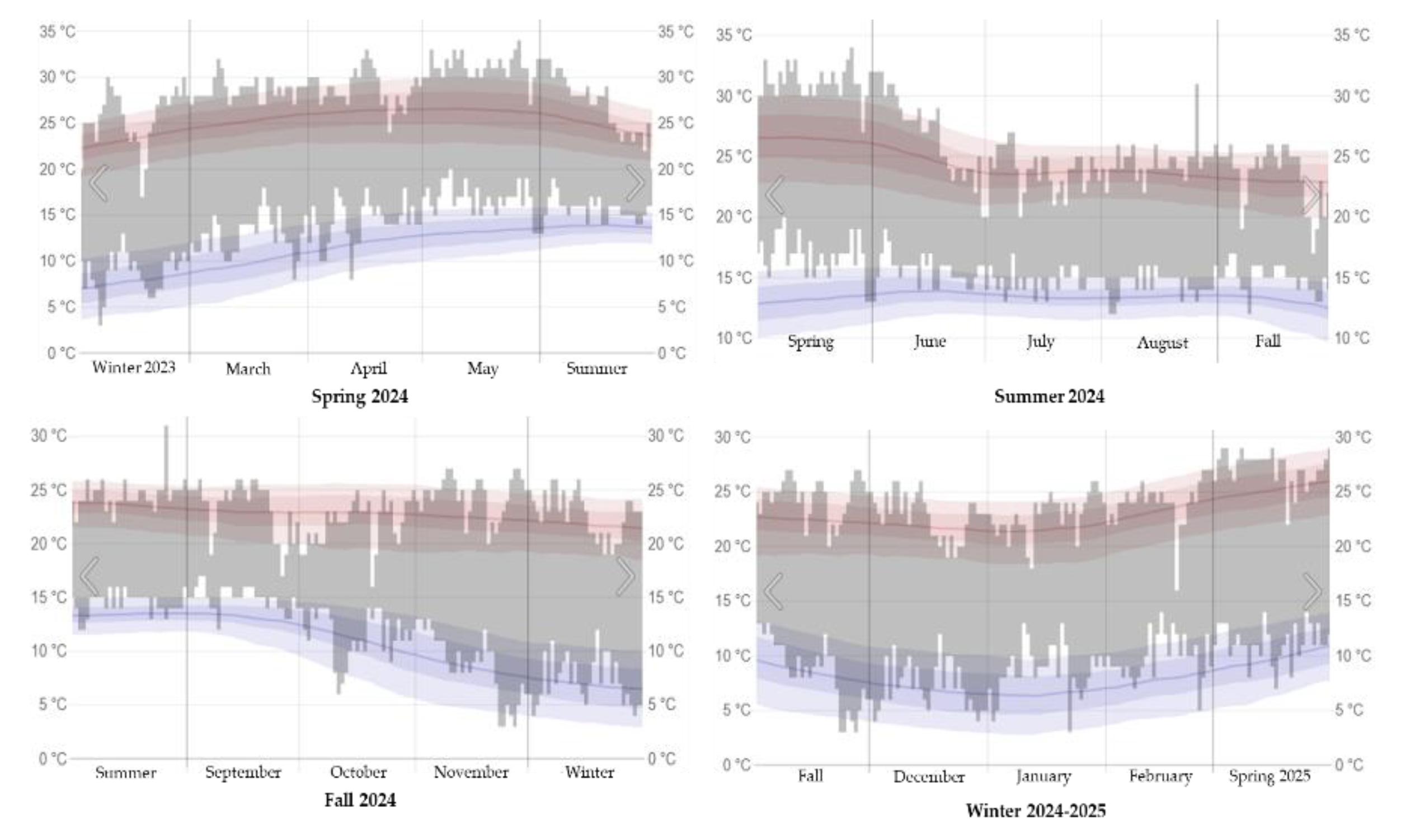

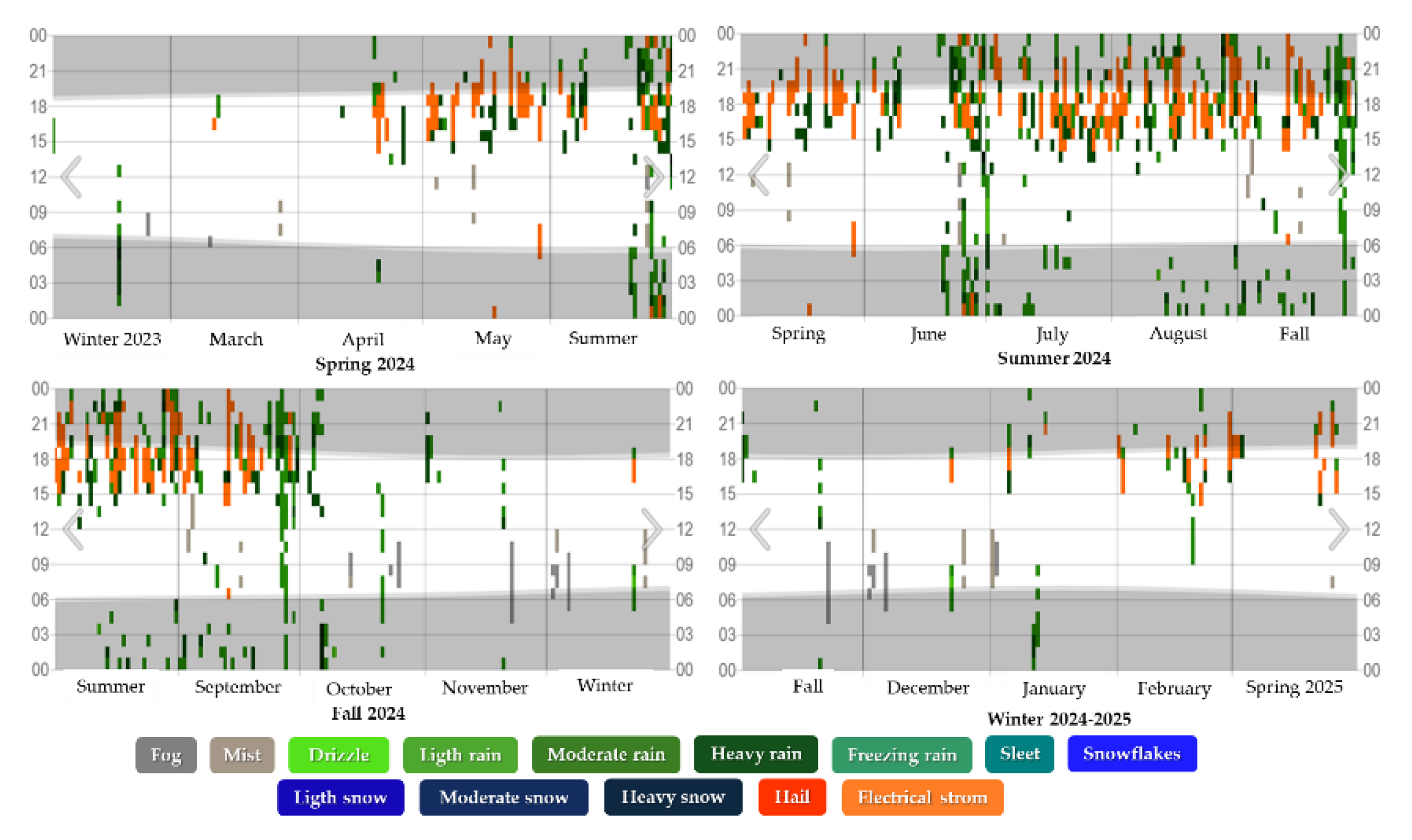

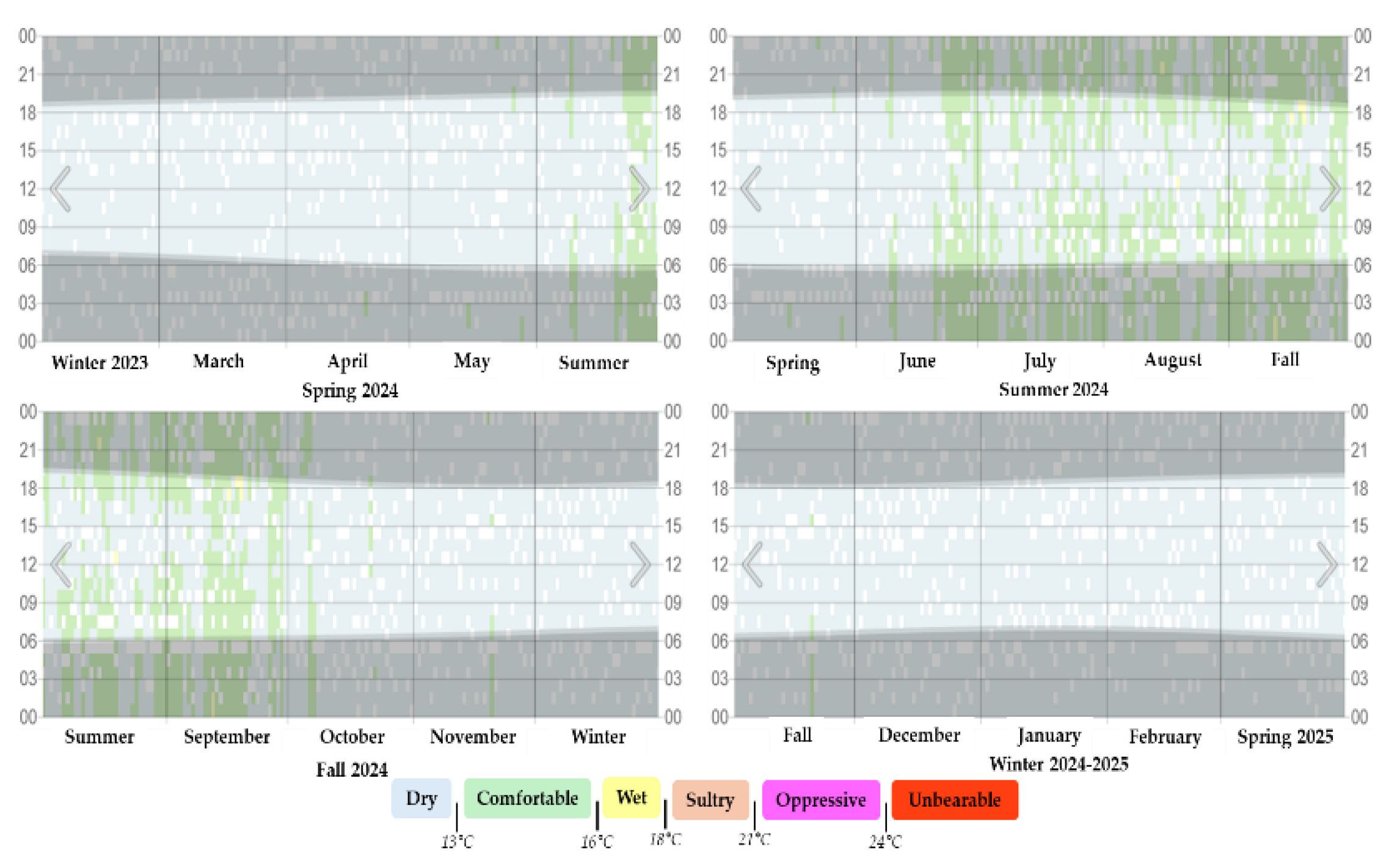

3.1. Behavior Under Climatic Conditions for the Period 2024-2025

The presentation of climatological variables (temperature, precipitation, and humidity) for the four seasons corresponding to the 2024-2025 period was based on the Merra-2 model on the weatherSpark.com platform with a 95% confidence level.

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 were obtained, showing the maximum, minimum, and average levels for each month within each season.

Figure 2.

Maximum and minimum temperatures in Texcoco de Mora, Mexico during the seasons of the 2024-2025 period.

Figure 2.

Maximum and minimum temperatures in Texcoco de Mora, Mexico during the seasons of the 2024-2025 period.

Where: The gray bars correspond to the daily temperature intervals, the red lines represent the maximum temperatures and the blue lines mark the minimum temperatures recorded.

Figure 3.

Precipitation levels in Texcoco de Mora, Mexico during the four seasons for the period 2024-2025.

Figure 3.

Precipitation levels in Texcoco de Mora, Mexico during the four seasons for the period 2024-2025.

Where: The observed time per hour is color-coded according to the category in order of intensity.

Figure 4.

Humidity levels in Texcoco de Mora, Mexico during the four seasons for the period 2024-2025.

Figure 4.

Humidity levels in Texcoco de Mora, Mexico during the four seasons for the period 2024-2025.

Where: Humidity level is categorized by the recorded daily dew point, the gray bands indicate nighttime and civil twilight.

Based on the previously analyzed weather conditions, the area where the samples were taken was determined to have optimal conditions for the development of Streptomyces avermitilis. It should be noted that isolating Streptomyces avermitilis can be complex due to the direct effect of weather conditions on each soil sample. This occurs due to seasonal climate anomalies (increases or decreases in temperature, humidity, and precipitation).

All of this has a negative impact on the frequency with which Streptomyces avermitilis bacterial cells form their characteristic filamentous hyphae and colonies on the specific culture medium at the laboratory level.

The above results in a slow or accelerated bacterial metabolism, which means that important bacterial characteristics cannot be clearly appreciated.

3.2. Performance of the Culture Medium: ISP-3 Oatmeal Agar

In the minutes of the International

Streptomyces Project (ISP) [

15,

16] six specific culture media are described for the isolation, characterization and purification of strains of the genus

Streptomyces, among which the ISP-3 medium: oatmeal agar allows the correct morphological characterization specific for

Streptomyces avermitilis.

In this study, the culture medium was homemade using oat flakes (

Figure 5).

Table 1 contains the technical information for the ISP-3 oat agar culture medium supplemented with nystatin as an antifungal agent, which was tested in the laboratory for use in strain isolation and purification.

This specific culture medium is useful in the isolation and purification of Streptomyces avermitilis, as it allows the formation of spores and filamentous hyphae, the production of diffusible pigments, and functions as an ideal substrate for storing bacteriological strain collection both on plates and in liquid media, where it maintains a shelf life of 12 weeks.

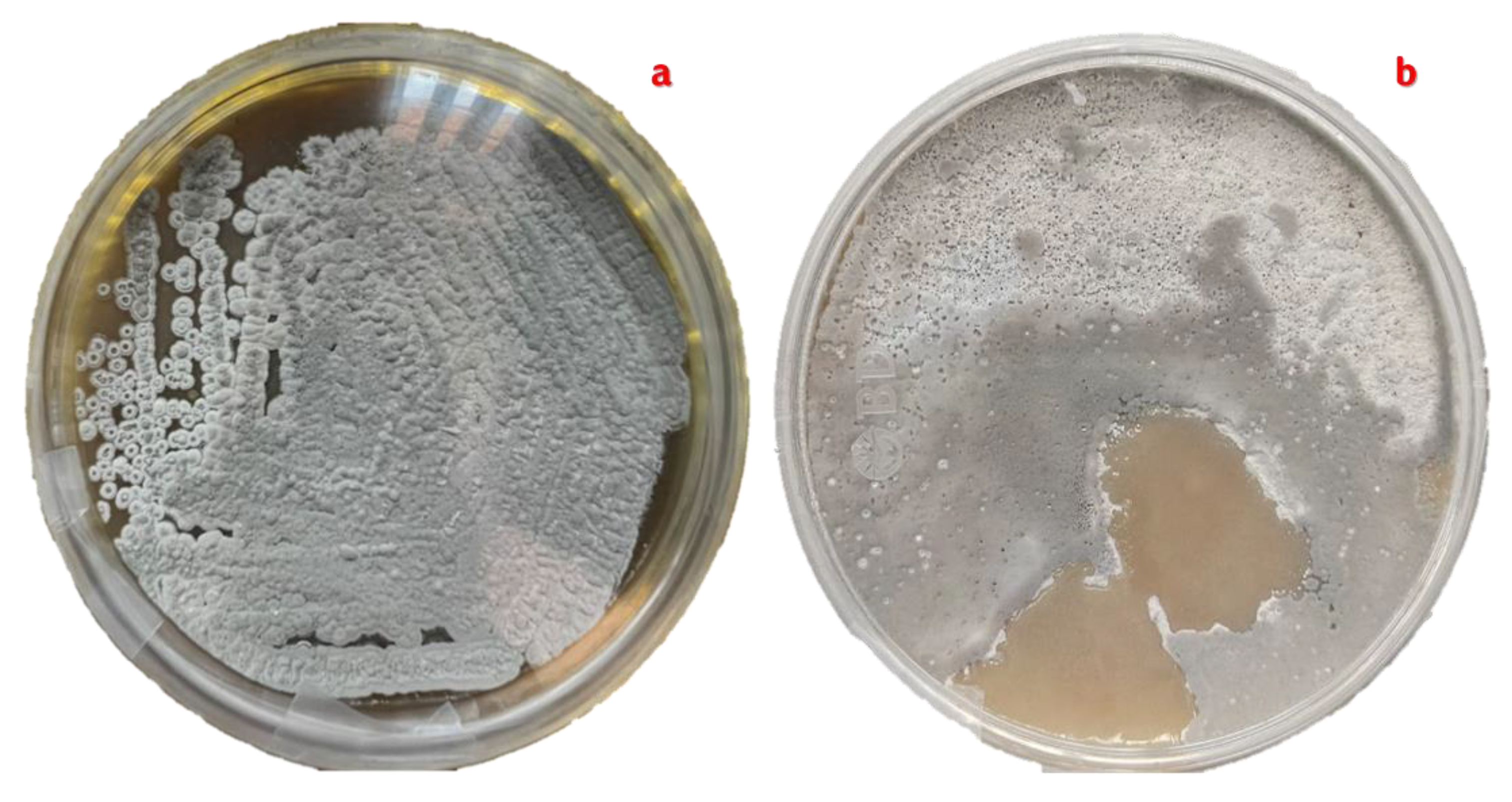

3.3. Morphological Characterization of Streptomyces avermitilis

The morphological characteristics of the pure strain isolated by the two types of culture during the four seasons of the year were used in detail for the taxonomic classification of

Streptomyces avermitilis (

Figure 6). This analysis was performed using the taxonomic keys proposed in

Bergey’s Manual, Volume 5: “The Actinobacteria” [

21,

22].

3.3.1. Specific Taxonomic Key for the Species Streptomyces avermitilis

Group 3. Spiral formation in the aerial mycelium (

Figure 7); long, open spirals.

I. Saprophytes; facultative psychrophiles to mesophiles

B. Presence of soluble brown pigments in organic culture media

1. Dark brown pigments (chromogenic type)

a7. Creamy to dark brown growth; gray aerial mycelium; sporophores in clusters.

48.

Streptomyces avermitilis [

2,

21,

23,

24,

25].

Synonyms: Streptomyces antibioticus [

26],

Streptomyces avermectinius [

27],

Actinomyces antibioticus [

2].

3.3.2. Characteristics of Mature Hyphae

Sporulation of the bacterium

Streptomyces avermitilis occurred in ISP-3 oatmeal agar culture medium supplemented with 1% nystatin. On day 7 of incubation in complete darkness at a temperature of 30 ± 2 °C, the pure culture reached its peak of maturity, with 95% of the plate cultures showing cottony aerial mycelium in shades of grey and white (

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8).

The effects of the total incubation time (10 days), added to the abiotic stress (incubation in complete darkness) and the use of ISP-3 oatmeal agar + 1% nystatin medium as a specific medium for the identification of Streptomyces avermitilis, allowed the bacteria to activate the sporulation phase between day 5 and 7.

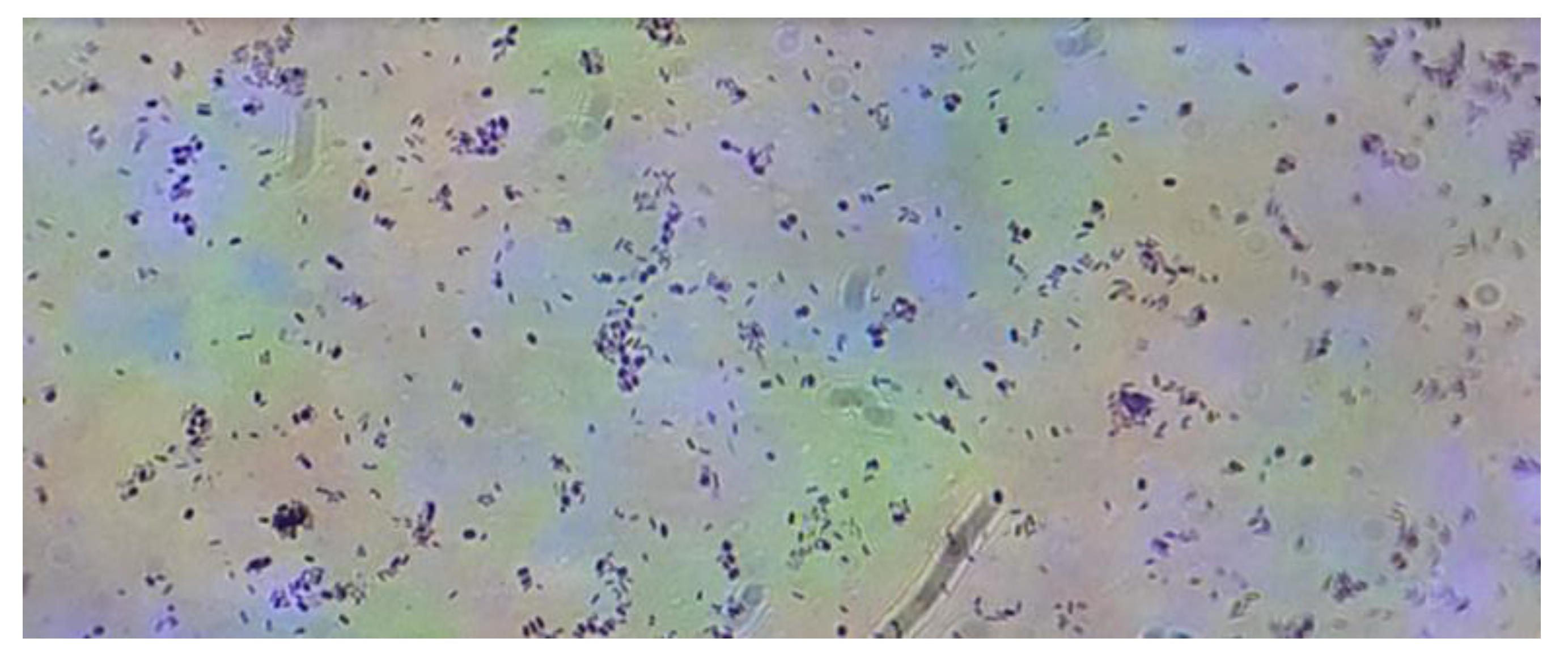

The filamentous hyphae of the bacterium

Streptomyces avermitilis were observed using Gram staining. Microscopic examination was also performed at 40X and 100X magnifications (

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11).

You can see the large network of filamentous hyphae characteristic of the strain, which will always be arranged in long whorls where the spores are found.

The final coloration was blue/purple, indicating that Streptomyces avermitilis is a Gram + microorganism.

After one minute of observation, the structure of the spores was analyzed and observed with 100X magnification and immersion oil in an optical microscope.

3.3.3. Morphological Differences in Isolates of Streptomyces avermitilis Evaluated During the Four Seasons of the Year

Throughout the isolations made during the four seasons, some important changes were observed, such as the presence of growth morphotypes of

Streptomyces avermitilis on plates containing ISP-3 oatmeal agar medium and the production of various diffusible pigments. These differences are clearly visible in

Figure 12.

These differences present in

Streptomyces avermitilis are usually linked to drastic increases in the pH of the soil (natural conditions) or the culture medium (

In vitro). This change can be caused by the bacteria itself when it self-induces an increase in the extracellular pH as a defense against its predators, or simply a change in the pH of the medium occurred due to exogenous alkaline compounds (water rich in carbonates, fertilizers, pesticides, contaminated water) [

28].

3.4. Maintenance of the Bacteriological Strain Collection of Streptomyces avermitilis

The species’ own bacteriological strain collection is under the protection of the Animal Nutrition Laboratory of the Colegio de Postgraduados, Montecillo Campus.

Streptomyces avermitilis isolates from four different soil types collected during the four seasons were purified in two different formats. The first format is a plate-based bacteriological strain collection with two different methods: cross-streak and dipstick (

Figure 13a,b). The second is stored in a liquid medium containing CTS supplemented with glucose and is stored in glass culture tubes with screw caps and in microbiological strain tubes in 15% glycerol. The latter are frozen at -20°C (

Figure 13d).

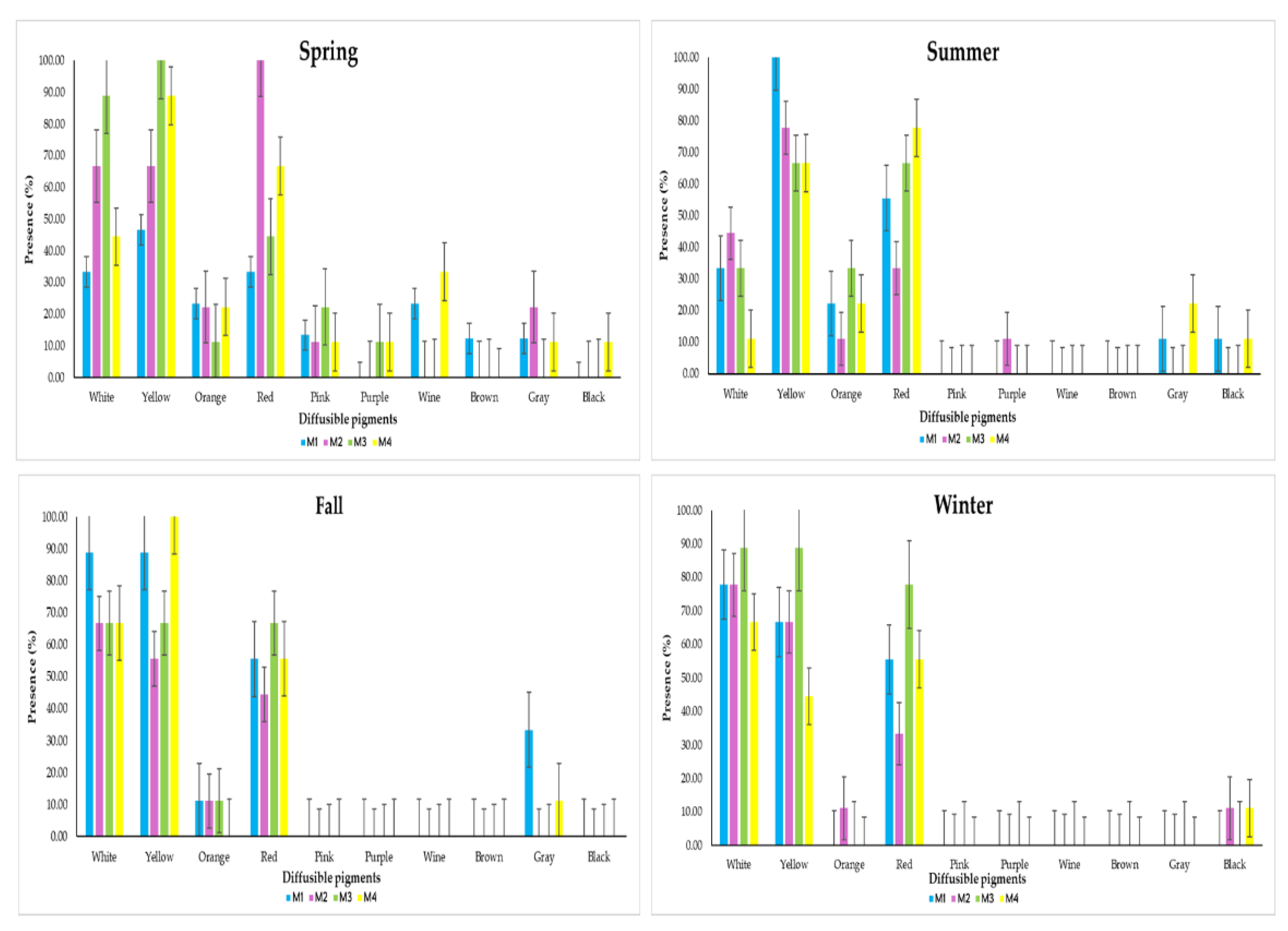

3.5. Production of Diffusible Pigments

According to the Montreal Microbiology Workshop, Canada [

29],

Streptomyces species have the ability to produce a series of 10 colors on the specific substrate in vitro. These colors are white, yellow, orange, red, pink, purple, brown, wine, gray and black.

In this analysis, the presence of these 10 colors was measured daily over 10 days in each isolate during the four seasons (

Figure 14). The behavior of the diffusible pigments presents in

Streptomyces avermitilis isolated from soils with different agricultural uses was primarily due to weather conditions, not to the soil type where the bacteria were isolated.

The biotic stress used in this analysis were the climatic conditions of each season of the year [

12,

30] with a direct relationship in each soil sample, so that, when slight changes in the climate variables occur,

Streptomyces avermitilis is able to activate its biosynthetic route of the polyketides PNKs responsible for secreting these diverse colors as a defense and survival mechanism [

31,

32].

The production of diffusible pigments of Streptomyces avermitilis in the four types of soil (M1, M2, M3 and M4) in spring resulted in greater presence with the following colors: white (33.33%, 66.67%, 88.89% and 44.44%), yellow (46.67%, 66.67%, 100% and 88.89%), orange (23.33%, 22.22%, 11.11% and 22.22%), red (33.33%, 100%, 44.44% and 66.67%) and pink (13.33%, 11.11%, 22.22% and 11.11%); The colors that had the least presence were purple (presence only in M3 with 11.11% and in M4 with 11.11%), wine (presence only in M1 with 23.33% and in M4 with 33.33%), brown (only in M1 with 12.22%), gray (presence only in M1 with 12.22%, M2 with 22.22% and M4 with 11.11%) and black (presence only in M4 with 11.11%).

In summer the most prevalent colours were white (33.33%, 44.44%, 33.33% and 11.11%), yellow (100%, 77.78%, 66.67% and 66.67%), orange (22.22%, 11.11%, 33.33% and 22.22%) and red (55.56%, 33.33%, 66.67% and 77.78%), with lesser presence were purple (present only in M2 with 11.11%), grey (11.11% in M1 and 22.22% in M4) and black (11.11% in M1 and 11.11% in M4); while the absent colours were pink, wine and brown.

In Fall the greatest presence was concentrated in white (88.89%, 66.67%, 66.67% and 66.67%), yellow (88.89%, 55.56%, 66.67% and 100%), orange (11.11% in M1, M2 and M3) and red (55.56%, 44.44%, 66.67% and 55.56%); with less presence was only gray (33.33% in M1 and 11.11% in M4), those that did not manifest were pink, purple, wine, brown and black.

Finally in Winter, the highest presence of pigments was white (77.78%, 77.78%, 88.89% and 66.67%), yellow (66.67%, 66.67%, 88.89% and 44.44%), orange (only 11.11% in M2) and red (55.56%, 33.33%, 77.78% and 55.56%), with lower presence only black (11.11% in M2 and M4), the absent pigments were pink, purple, wine, brown and gray.

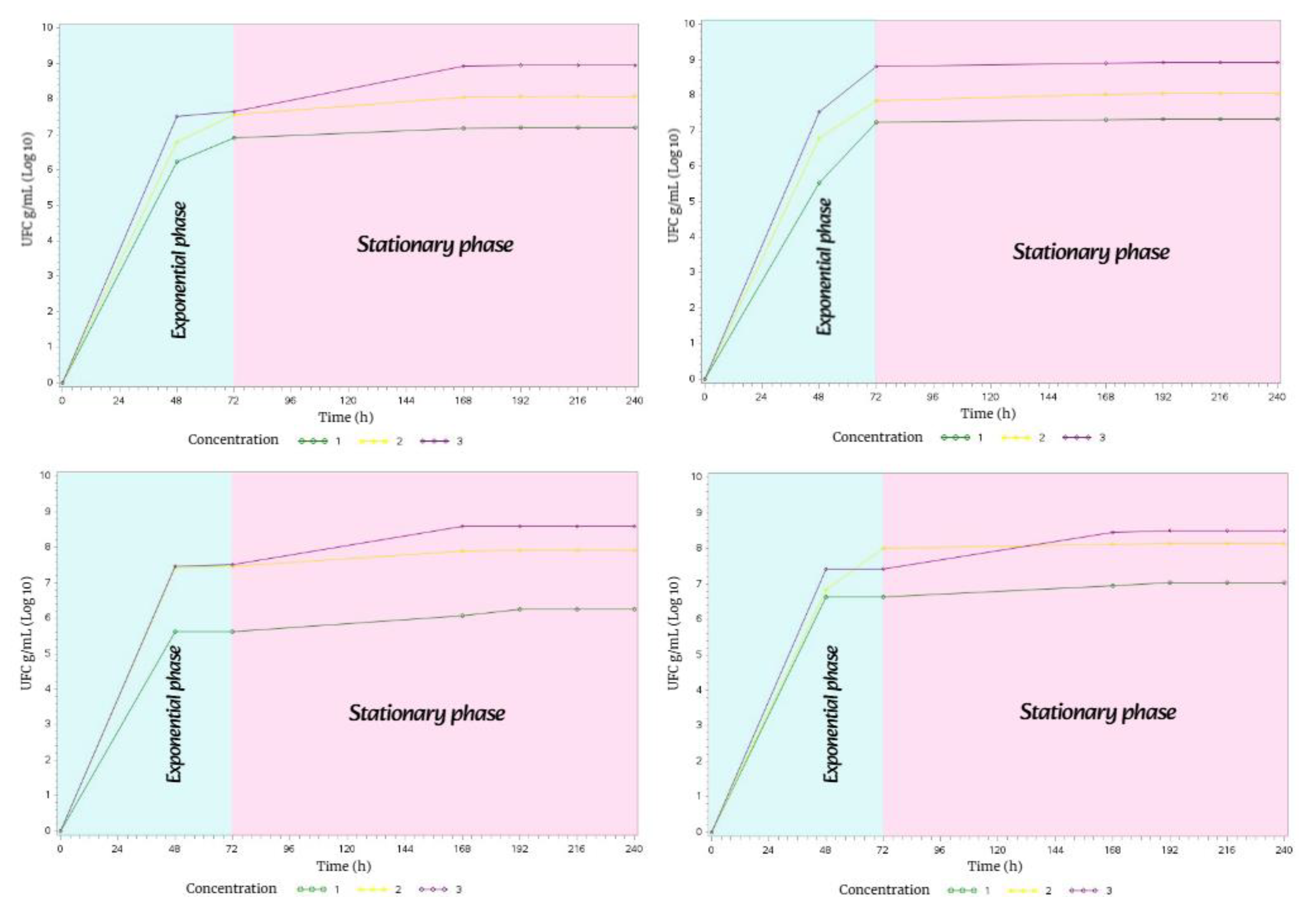

3.6. Bacterial Growth of Streptomyces avermitilis During the Four Seasons of the Year

To understand the metabolic behavior of

Streptomyces avermitilis, it was necessary to construct bacterial growth curves in order to analyze its duration in the four soil types evaluated during the four seasons of the year. These graphs are a basic tool in the manipulation of bacterial metabolism, as they help improve the development of secondary metabolites of

Streptomyces avermitilis [

33,

34].

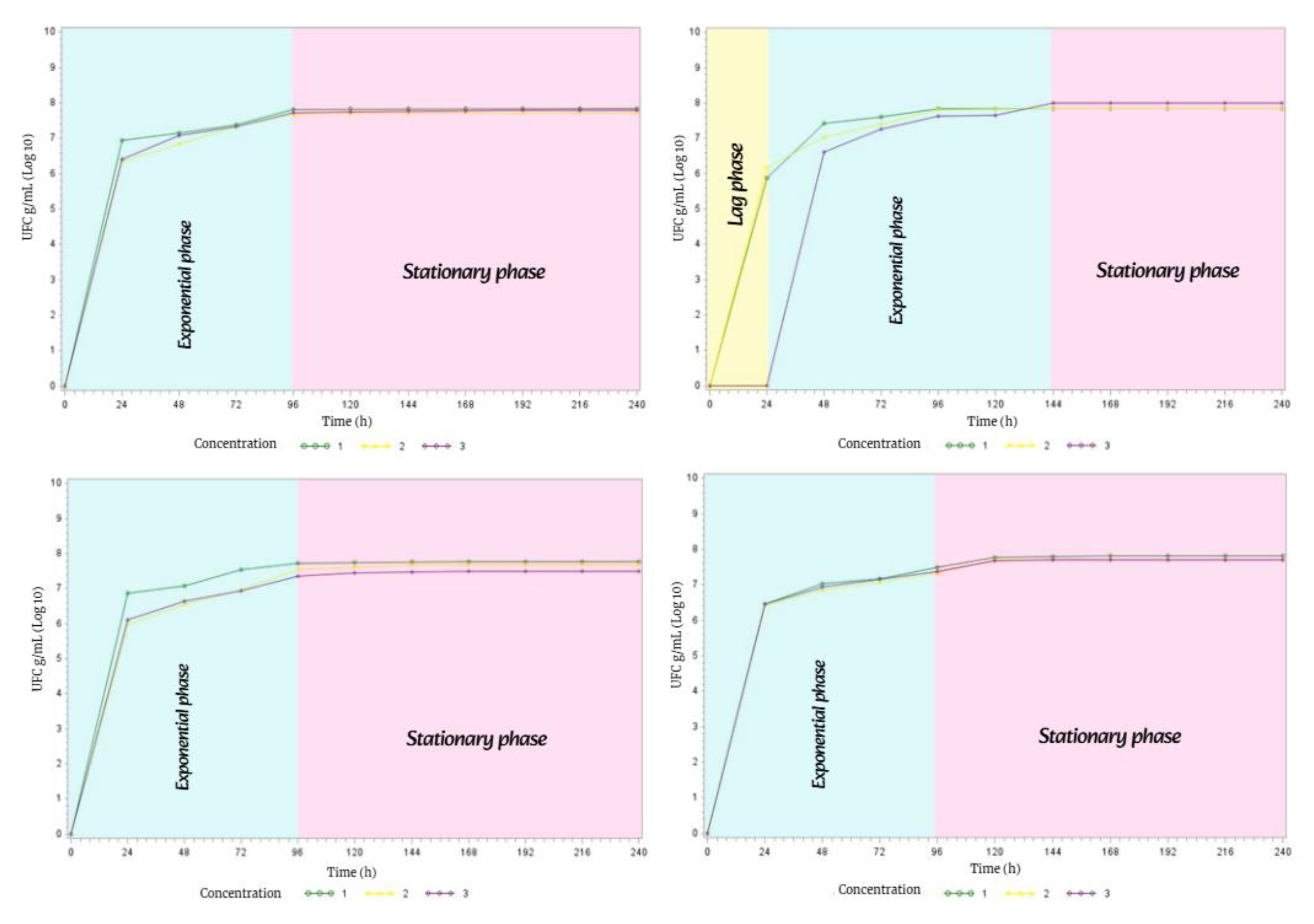

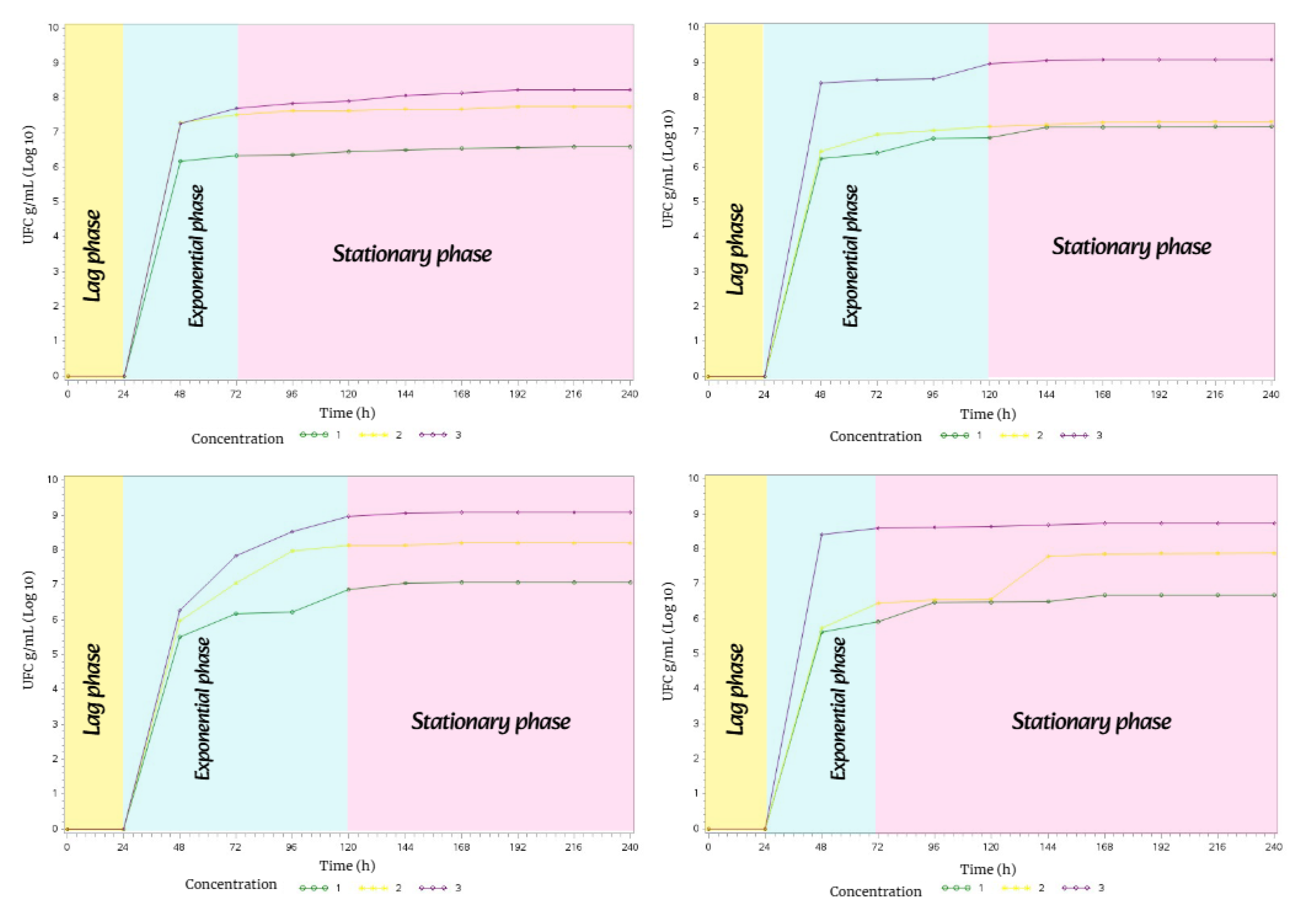

In spring, the bacterial growth of

Streptomyces avermitilis presented the

exponential phase lasting 72 h and the

stationary phase lasting 168 h. This behavior was the same in the four types of soil during the 10 days of incubation in complete darkness (

Figure 15).

In summer, the bacterial growth of

Streptomyces avermitilis in the four soil types exhibited the same behavior, with all three phases of bacterial growth (

lag, exponential, and

stationary phases, Figure 16).

The lag phase lasted 24 h in all four soil types; the exponential phase lasted 48 h in M1 and M4, while it lasted 96 h in M2 and M3; and the stationary phase lasted 168 h in M1 and M4, and 120 h in M2 and M3.

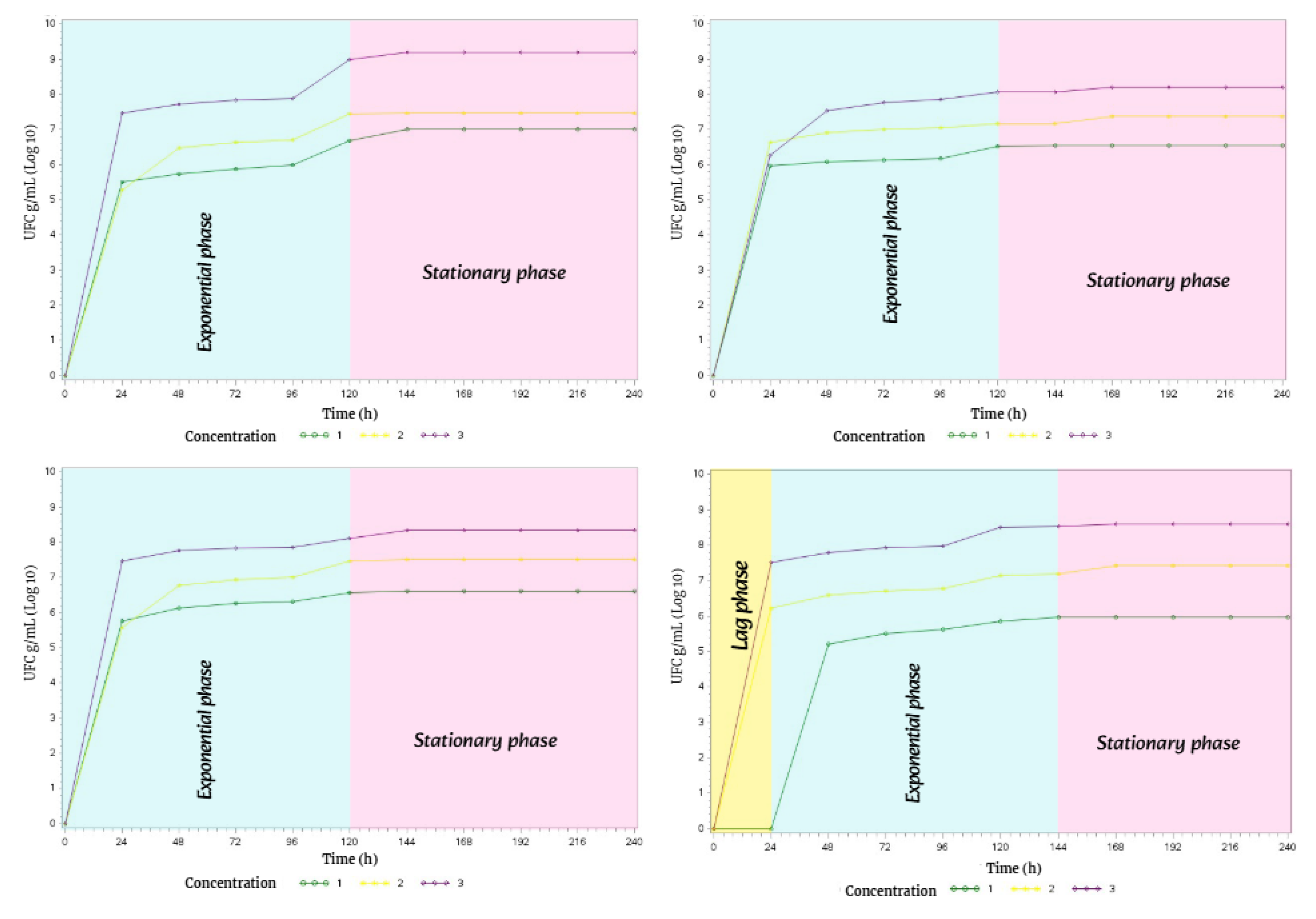

Due to a slight decrease in temperature, precipitation, and humidity in fall, the bacterial growth phases of Streptomyces avermitilis showed notable changes in three of the four soil types.

Therefore, soil types M1, M3, and M4 only exhibited two phases of bacterial growth: the exponential phase lasted 96 h, while the stationary phase lasted 144 h.

However, in soil type M2, all three phases of bacterial growth were present. The lag phase lasted 24 h, the exponential phase lasted 120 h, and the stationary phase lasted 96 h.

Figure 17.

Bacterial growth behavior of Streptomyces avermitilis over 10 days in Fall.

Figure 17.

Bacterial growth behavior of Streptomyces avermitilis over 10 days in Fall.

In winter, the metabolism of

Streptomyces avermitilis exhibited unusual behavior, with the

exponential and

stationary phases lasting 120 h each in M1, M2, and M3. In M4, all three phases of bacterial growth were present: the

lag phase lasted 24 h, the

exponential phase 120 h, and the

stationary phase 96 h (

Figure 18).

3.7. Bacterial Doubling Time

The bacterial doubling time results for

Streptomyces avermitilis growing on ISP-3 oatmeal agar plates + 1% nystatin were calculated based on daily plate counts at the same time. The counts were transformed to natural logarithms (

Ln) and then graphed using linear regression to obtain mu (slope of the line representing the linear model and expressing the number of cells/hour in the exponential phase,

Table 2).

4. Discussion

This research evaluated four different types of soils in the four seasons of the year during the period 2024-2025 where the bacterial metabolism of

Streptomyces avermitilis was analyzed. Where exact values were obtained on the proportion of diffusible pigments by season and land use, the duration of the bacterial growth phases, morphological differences of the strain and the different morphotypes that were presented in the three concentrations used in each sowing (10

-4, 10

-5 and 10

-6) that had not been described in other research carried out with the same strain [

13,

25,

38].

Soil samples from four soil types evaluated during the four seasons of the period 2024-2025 at the Colegio de Postgraduados, Montecillo Campus, Texcoco de Mora, State of Mexico, Mexico; which served as the main object to obtain the isolates of

Streptomyces avermitilis presented valuable characteristics that turned out to be optimal for the existence of the strain. Because in the 70’s it was declared that this strain was only endemic to Japan and that it was possibly the result of the multiple mutations found in soil microorganisms after the atomic bombing in the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki [

13,

22,

23,

24,

25,

27,

37,

38,

40,

42,

48].

According to the findings presented here, it is demonstrated that Streptomyces avermitilis is a microorganism present in any type of soil and that it can be found in Mexico, so it is not endemic to Japan.

In order to correctly manipulate the metabolism of

Streptomyces avermitilis, it is necessary to analyze the climatic conditions of the environment where the bacteria has been located. The main climatic variables that influence the silencing or activation of bacterial metabolism are temperature, precipitation and humidity, since they are responsible for the soil providing the necessary nutrients and generating an ecological niche conducive to the growth and development of

Streptomyces avermitilis [

1,

3,

4,

17], which is reflected in the production of bioactive secondary metabolites [

36].

An excellent accumulation of nutrients available in the environment surrounding the bacteria determines the type, form and concentration of different secondary metabolites [

32], if there is a balance between the substrate: nutrients: bacteria, it can lead to the activation of the main BGC [

25,

37].

The design of this study allowed for the analysis of temperature, precipitation, and humidity during the four seasons from 2024 to 2025 at the same sites where the soil samples were collected. This approach was the first time that

Streptomyces avermitilis metabolism was analyzed over a longer period of time compared to other studies where the maximum duration recorded was 15 days [

1,

3,

4,

5,

7,

13,

17,

41].

The climatological variables analyzed are related to the presence and phases of bacterial growth of Streptomyces avermitilis in each season. This is consistent with the conditions observed during the summer, when the temperature was 28 °C, precipitation was 133 mm, and humidity was 75%.

Due to the above levels, the three most important phases of bacterial growth (lag, exponential, and stationary phases) were correctly expressed.

According to previous research [

1,

5,

7,

13] it was declared that

Streptomyces avermitilis developed in climates that present a temperature range of 12 °C to 30 °C and with a minimum of 10% humidity, since what was reported in this research agrees with these conditions.

The purified isolates of

Streptomyces avermitilis used in this research come from terrestrial soils, specifically from different land uses, among which stand out: soil with forage crops (oats and corn), dormant soil (> 5 years), soil from a silvopastoral system (

Cajanus cajan) and soil from a dairy farm (high degree of organic matter). This proves that different types of soil and regardless of their use, present strains of

Streptomyces avermitilis with great biosynthetic potential [

35], the same effect was found with

Streptomyces avermitilis isolated in Japanese soils [

5,

7,

25,

35].

For

In vitro analysis, improvements in techniques and strategies were proposed in order to ensure the correct expression of secondary metabolites (diffusible pigments, production of the amber drop containing Ivermectin, filamentous hyphae, spores, volatile organic compounds), therefore, in this research oat flour was used to obtain the ISP-3 oat agar culture medium. This was produced by grinding previously sieved oat flakes, being equivalent to the rich, abundant and balanced source of carbon : nitrogen (3:1) [

15,

38].

This ingredient was used due to its ease of acquisition, and also because it has a high protein content and natural nutrients that are required for bacterial growth of

Streptomyces avermitilis [

5,

7,

13,

39]. Oatmeal agar supplemented with 1% nystatin as a finished product is usually an easy culture medium to prepare and handle, which represents an economic and time advantage in the laboratory [

36].

Bacterial growth is a physiological variable of bacteria; in the case of

Streptomyces avermitilis, it will depend on the climatic conditions of the season in which the soil sample is taken for isolation [

9].

This is due to the way it responds to the amount of nutrients available in the soil, bacterial competition, plant roots that capture more moisture, temperature, pH and the availability of carbon : nitrogen in the substrate [

1,

4,

5,

7,

9,

13,

38].

Some studies mention that the maximum point of sporulation and formation of filamentous hyphae of

Streptomyces avermitilis occurred on day 15 [

5,

13,

40], while the strain used in this study showed its sporulation between day 5 to 7 of the exponential phase of its bacterial growth. This occurred in response to the induced abiotic stimulus (growth in complete darkness) and the correct assimilation of nutrients provided in the ISP-3 oatmeal agar medium, since

Streptomyces avermitilis activated its metabolism for survival under laboratory conditions [

41].

This behavior is so characteristic of

Streptomyces avermitilis, therefore, by presenting a genome with at least 38 BGC for the production of secondary metabolites [

33,

36,

37] these can be activated or deactivated in those seasons of the year where the amount of nutrients in the soil or in the culture medium are depleted or shoot up.

In a study where the knock-out technique was used in the development of native antibiotic pathways for growth manipulation in

Streptomyces sp. strains, a rapid replication rate of 3.6 h was obtained [

42]; another study revealed that the doubling rate in species of the genus

Streptomyces can vary from 6.5 h to 5.6 days [

43].

It has been previously shown that the growth and development of

Streptomyces cells and the synthesis of secondary metabolites require a balanced ratio of carbon : nitrogen : phosphorus (3:1:2), with the duplication time being associated with the speed at which its primary metabolism takes advantage of the available nutrients [

9,

44] to be transformed into energy for the bacteria, achieving the activation of secondary metabolism and thus obtaining biologically active products (secondary metabolites) [

11,

33,

36,

37,

46].

The production of secondary metabolites in

Streptomyces avermitilis is abundant, but the full extent of its bioactive potential and the conditions under which they may occur are still unknown. When nutrient resources are limited [

45], they produce their characteristic aerial hyphae where the spores are found, these withstand adverse conditions (climate changes or aspects induced in the laboratory) and through some stimulus or stress they will be released at the right time to initiate the activation of the BGC [

11,

46].

The production of diffusible pigments by Streptomyces avermitilis serves as a means of identifying the bacteria, as a test of the quality and specificity of the culture medium for isolation, and as a response mechanism for forming biologically active compounds (drugs).

It should be noted that these depend on two factors: 1) season of the year (various climatic conditions) and 2) type of sample where the isolate was obtained [

5,

7,

25,

31,

37,

41].

In more advanced disciplines such as Molecular Biology, it has been found that the production of first-order secondary metabolites such as diffusible pigments, Ivermectin B1b, filamentous hyphae, spores, volatile compounds are a consequence of five biosynthetic pathways: glucose pathway, polyketide pathway, amino acid pathway, shikimate pathway and mevalonate (MVA) or methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway [

31,

37,

47,

48].

The results presented here confirm that inducing bacterial growth of Streptomyces avermitilis in complete darkness and in the ISP-3 oatmeal agar + 1% nystatin culture medium as an antifungal effect carried out by hand with sieved oat flakes, presents optimal growth and presents an excellent production of bioactive secondary metabolites.

The specific culture medium developed for the identification, isolation, and purification of Streptomyces avermitilis offers a practical and sustainable solution that can compete with commercially available culture media, making it an accessible raw material for performing microbiology laboratory techniques.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, JLM; methodology, JLM, MMCG, EMCG; formal analysis, MMCG, LHVH, MTSTE, CCR, and RDAM; investigation, JLM, MMCG, EMCG, LHVH, MTSTE, CCR, and RDAM; writing and preparation of the original draft, JLM; writing, review, and editing, MMCG, EMCG, LHVH, MTSTE, CCR, and RDAM; supervision, MMCG and EMCG; project administration, JLM, MMCG, and EMCG. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript”.

Figure 1.

Cross-streak sowing technique.

Figure 1.

Cross-streak sowing technique.

Figure 5.

Procedure for preparing the ISP-3 oatmeal agar culture medium. a). Base materials for preparing the specific medium. b). Weighing oat flour and nystatin. c). Mixing all components. d). Stirring on an electromagnetic grid. e). Emptying the oat agar into a Petri dish. f). Gelled ISP-3 oat agar culture medium.

Figure 5.

Procedure for preparing the ISP-3 oatmeal agar culture medium. a). Base materials for preparing the specific medium. b). Weighing oat flour and nystatin. c). Mixing all components. d). Stirring on an electromagnetic grid. e). Emptying the oat agar into a Petri dish. f). Gelled ISP-3 oat agar culture medium.

Figure 6.

Pure culture of Streptomyces avermitilis with cottony aerial mycelium in grey tones. a). Pure culture produced by the four-quadrant cross-stretch technique. b). Pure culture obtained by the rod-drawing technique. Both cultures are planted on ISP-3 oatmeal agar supplemented with nystatin.

Figure 6.

Pure culture of Streptomyces avermitilis with cottony aerial mycelium in grey tones. a). Pure culture produced by the four-quadrant cross-stretch technique. b). Pure culture obtained by the rod-drawing technique. Both cultures are planted on ISP-3 oatmeal agar supplemented with nystatin.

Figure 7.

Aerial mycelium of the culture and pure colony of Streptomyces avermitilis isolated on oatmeal agar (ISP-3).

Figure 7.

Aerial mycelium of the culture and pure colony of Streptomyces avermitilis isolated on oatmeal agar (ISP-3).

Figure 8.

Presence of cottony aerial mycelium in whitish tones.a). Diffuse mycelium throughout the culture plate. b). Central mycelium.

Figure 8.

Presence of cottony aerial mycelium in whitish tones.a). Diffuse mycelium throughout the culture plate. b). Central mycelium.

Figure 9.

Observation of the Streptomyces avermitilis smear with 40X magnification in an optical microscope.

Figure 9.

Observation of the Streptomyces avermitilis smear with 40X magnification in an optical microscope.

Figure 10.

Gram stain on the Streptomyces avermitilis smear seen at 40X magnification under a light microscope.

Figure 10.

Gram stain on the Streptomyces avermitilis smear seen at 40X magnification under a light microscope.

Figure 11.

Smooth, oval structure of Streptomyces avermitilis spores stained blue/purple using the Gram staining technique.

Figure 11.

Smooth, oval structure of Streptomyces avermitilis spores stained blue/purple using the Gram staining technique.

Figure 12.

Morphological and color differences of Streptomyces avermitilis evaluated during the four seasons of the year.

Figure 12.

Morphological and color differences of Streptomyces avermitilis evaluated during the four seasons of the year.

Figure 13.

Strain collection of the species Streptomyces avermitilis. a). Cross-streak inoculation in ISP-3 oatmeal agar medium, b). Rod-drawing inoculation in ISP-3 oatmeal agar medium, c). CTS inoculation in glass tubes at 4 °C, d). CTS inoculation in 15% glycerol at -20 °C.

Figure 13.

Strain collection of the species Streptomyces avermitilis. a). Cross-streak inoculation in ISP-3 oatmeal agar medium, b). Rod-drawing inoculation in ISP-3 oatmeal agar medium, c). CTS inoculation in glass tubes at 4 °C, d). CTS inoculation in 15% glycerol at -20 °C.

Figure 14.

Pigments produced by Streptomyces avermitilis by type of land use during the four seasons of the year.

Figure 14.

Pigments produced by Streptomyces avermitilis by type of land use during the four seasons of the year.

Figure 15.

Bacterial growth behavior of Streptomyces avermitilis over 10 days in Spring.

Figure 15.

Bacterial growth behavior of Streptomyces avermitilis over 10 days in Spring.

Figure 16.

Bacterial growth behavior of Streptomyces avermitilis over 10 days in Summer.

Figure 16.

Bacterial growth behavior of Streptomyces avermitilis over 10 days in Summer.

Figure 18.

Bacterial growth behavior of Streptomyces avermitilis over 10 days in Winter.

Figure 18.

Bacterial growth behavior of Streptomyces avermitilis over 10 days in Winter.

Table 1.

Conditions for quality control and microbiological tests on ISP-3 oatmeal agar.

Table 1.

Conditions for quality control and microbiological tests on ISP-3 oatmeal agar.

| Solubility |

Appearance |

Medium color |

Incubation Conditions |

pH |

Gelation temperature |

Yield/L |

| Suspended particles |

Fine powder |

Beige |

30 ± 2 °C 18 to 240 h |

6.6 |

85 °C |

38 Petri dishes of 20 mL |

Table 2.

Doubling time of Streptomyces avermitilis by soil type expressed in days and hours.

Table 2.

Doubling time of Streptomyces avermitilis by soil type expressed in days and hours.

| M1 |

| Variable |

Mean ± σ |

EE |

CV |

| Td (hours) |

38.1933 ± 10.1557 a |

4.146 |

26.5902 |

| Td (days) |

1.5916 ± 0.4228 b |

0.1726 |

26.5675 |

| M2 |

| Variable |

Mean ± σ |

EE |

CV |

| Td (hours) |

35.3050 ± 7.9012 a |

3.2256 |

22.3799 |

| Td (days) |

1.4700 ± 0.329 b |

0.1343 |

22.3849 |

| M3 |

| Variable |

Mean ± σ |

EE |

CV |

| Td (hours) |

62.9266 ± 22.4806 a |

9.1776 |

35.7251 |

| Td (days) |

2.6216 ± 0.3832 b |

0.3832 |

35.8115 |

| M4 |

| Variable |

Mean ± σ |

EE |

CV |

| Td (hours) |

61.5200 ± 35.8343 a |

14.6293 |

58.2483 |

| Td (days) |

2.5650 ± 1.4951 b |

0.6103 |

58.2904 |