KeywordsStreptomyces; Plant-growth promotion; Secondary metabolites; Whole-genome sequencing; Pan-genome; Biosynthetic Gene Clusters

1. Introduction

The increasing costs and negative effects of synthetic chemicals used in crop production necessitate the adoption of biological options of crop production and protection, such as crop residues, farmyard manures, composts, and plant growth-promoting (PGP) bacteria. The use of PGP bacteria has been one of the alternative strategies for improving agricultural production, as well as soil and plant health (Subramaniam 2016). Moreover, such strategies are among the sustainable agriculture practices as they are environment-friendly and have the potential to reduce the need for synthetic chemicals (Subramaniam 2016).

PGP bacteria are found mostly in soil, compost, fresh and marine water, and play an important role in the PGP, plant protection, decomposition of organic materials, and produce secondary metabolites of commercial interest. These secondary metabolites are diverse kinds of biomolecules, such as growth hormones, antibiotics, and peptides, which are degradable and less toxic, and often specific against plant pathogens (Gopalakrishnan et al. 2020).

PGP actinomycetes such as Streptomyces and their secondary metabolites were reported widely as an excellent alternative for improving nutrient availability, enhancing root and shoot growth, nitrogen fixation, grain and stover yields, solubilisation of inorganic minerals, and protecting against plant pathogens of agriculturally important crops (Aggarwal et al. 2016; Bhattacharyya et al. 2017; Vijayabharathi et al. 2018a; Vijayabharathi et al. 2018b). The attributes may be due to the production of antibiotics, chitinase, cellulase, lipase, hydrocyanic acid, siderophore, phytohormones, β-1, 3-glucanase production, and ACC-deaminase (Gopalakrishnan et al. 2021). The PGP potential of Streptomyces strains was well documented in tomato, wheat, rice, bean, chickpea, pigeonpea, sorghum, and pea (Subramaniam Gopalakrishnan 2011; Gopalakrishnan et al. 2012; Gopalakrishnan et al. 2013; Gopalakrishnan et al. 2014; Gopalakrishnan et al. 2015a; Gopalakrishnan et al. 2015b; Subramaniam 2016; Sathya et al. 2016; Subramaniam et al. 2020; Gopalakrishnan et al. 2020; Gopalakrishnan et al. 2021; Srinivas et al. 2022; Gopalakrishnan et al. 2022; Sambangi and Gopalakrishnan 2023).

While screening selected rhizospheric isolates for entomopathogenic/insecticidal activities in vitro and under greenhouse conditions, (Vijayabharathi et al. 2014) reported one of them, namely SAI-25, as a promising candidate, given its strongest activity against lepidopteran insects such as Helicoverpa armigera, Spodoptera litura, and Chilo partellus. Based on the similarity to the 16s rRNA sequence database, this strain was assigned to Streptomyces griseoplanus (Vijayabharathi et al. 2014). On further investigation, a cyclodipeptide was identified from SAI-25, namely cyclo(Trp-Phe), which showed insecticidal properties, such as antifeedant, insecticidal, and pupicidal activity, against H. armigera (Sathya et al. 2016). Furthermore, spectral analysis of the cell-free extracellular extract of SAI-25 by FTIR confirmed the presence of alcohols, amines, phenols, and protein, which not only played the role of stabilizing agent while synthesis of silver nanoparticles, but also proved as a base for the development of Streptomyces mediated nanoparticle biopesticide due to its antifungal activity against charcoal rot pathogen, Macrophomina phaseolina (Vijayabharathi et al. 2018c).

Several such strains or isolates, which were characterized for having a few plant growth-promoting features, have been further examined for the underlying genes or pathways, which include a couple of studies by the authors on multiple isolates from Streptomyces and Amycolatopsis genera (Subramaniam et al. 2020; Gandham et al. 2024). Although the entomopathogenic, antifungal properties and identification of an insecticidal metabolite (a diketopiperazine class compound) make SAI-25 a very promising PGP bacteria, the genetic and genomic basis of the known features, as well as its potential to synthesize other secondary metabolites, remain unexplored.

The current study aimed to identify the genes and pathways underlying the PGP/biocontrol traits and to predict the secondary metabolite biosynthetic potential of SAI-25 by genome mining. To answer this question, deep sequencing of the genome sequence of this isolate was done to obtain a genome assembly of SAI-25. The genome sequence was compared with existing Streptomyces genomes to confirm its taxonomic classification. The pan-genome analysis of complete genomes of the Streptomyces genus helped in identifying the core and unique genes, as well as their functional importance. Further, the annotation of the genome assembly was mined for genes or gene clusters involved in the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, with more emphasis on the ones that have already been reported in SAI-25.

2. Materials and Methods

The workflow followed in the current study is illustrated in Fig. 1. The details are elaborated in the subsequent sections.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram showing the workflow followed in the current study. This figure was created using the BioRender tool (

https://BioRender.com).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram showing the workflow followed in the current study. This figure was created using the BioRender tool (

https://BioRender.com).

2.1. Microbial Strain Used in This Study

The previously identified S. griseoplanus strain, namely, SAI-25 (GenBank accession number: KF770901), isolated from a rice rhizospheric field at Karnataka, India, demonstrated previously for its plant growth promotion (PGP) and entomopathogenic traits against Helicoverpa armigera, Spodoptera litura, and Chilo partellus (Vijayabharathi et al. 2014; Sathya et al. 2016; Vijayabharathi et al. 2018c), was used in this study.

2.2. Culture of PGP Strain and Genomic DNA Isolation

Genomic DNA of SAI-25 was isolated as per the protocols mentioned in Subramaniam et al. (2020). In brief, SAI-25 was incubated for 120 h at 28° C followed by centrifugation at 10,000g for 10 minutes at 4 °C. The pellet was washed twice with STE buffer, and re-suspended in 8.55 ml STE buffer and 950 µl lysozyme (20 mg/ml STE buffer). It was first incubated for 30 min at 30 °C, followed by adding 500 µl of SDS (10%; w/v) and 50 µl of protease (20 mg/ml), and the same was kept at 37 °C for one hour. Once the incubation was over, 1.8 ml of NaCl (5 M) was gently added, along with 1.5 ml of CTAB/NaCl solution (10% w/v CTAB in 0.7 M NaCl), followed by incubation for 20 min at 65 °C. The lysate was subsequently subjected to two sequential extractions using PCI mixture (an equal volume of phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol; 25:24:1 by volume), followed by centrifugation at 13,000g for 10 minutes. The aqueous phase was extracted using chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (24:1, by volume), followed by the addition of 600 µl of propan-2-ol. The DNA was either scooped up after 10 minutes or was recovered by centrifugation at 12,000g for 10 min. The pellet was washed twice using ethanol (70%; v/v), vacuum dried, and then dissolved in 2 mL of TE buffer (10 mM Tris/HCl and 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0). Finally, RNase A (50 mg/ml) was added, and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for two hours. It was extracted again with phenol by following the steps mentioned above. DNA was then re-precipitated from the aqueous phase by adding 100 µl of sodium acetate (3M, pH 5.3) and 600 µl of propan-2-ol. The DNA pellet was then washed with ethanol (70%; v/v), dried, and resuspended in the TE buffer. The quality of the SAI-25 DNA was checked by agarose gel electrophoresis, followed by its quantification using NanoDrop.

2.3. Library Preparation and Sequencing

The genomic DNA thus extracted was processed to prepare libraries for whole-genome shotgun sequencing as described in our previous work (Gandham et al. 2024). Briefly, high-quality genomic DNA of ~5 μg (devoid of any contamination and exhibiting an A260/280 ratio between ~ 1.8 - 2.0, with DNA concentration ≥ 100 ng/μl) was sent to AgriGenome Labs (Kochi, India) for library preparation and next-generation sequencing using the Illumina platform. The genomic DNA was fragmented to obtain two types of libraries: i) a paired-end library with an insert size of 300 bp; and ii) a mate-pair library with an insert size of 5 Kbp. The quality of DNA fragment libraries was validated by tapestation and subsequently sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq2500, generating ~ 9.905 million paired-end reads (100 bp × 2) and ~ 6.242 million mate pair (250 bp × 2) reads.

2.4. Genome Assembly and Annotation

The whole genome sequenced paired- and mate-pair reads (Encoding: Illumina 1.9) of the bacterial genome were cleaned (by removing adapter and primer sequences, etc.) using Trimmomatic (Bolger et al. 2014). The pre-processed paired and mate-pair reads were

de novo assembled using SOAPdenovo V2.04 and SPADES V3.10.1 assemblers (Bankevich et al. 2012). Two assemblies were assessed and compared by using QUAST, followed by discarding the contigs having a length of <500bp and coverage <5 (Gurevich et al. 2013). The GapCloser was used to close the gaps that emerged during the scaffolding process by the

de novo assembler, using the abundant pair relationships of short reads (Luo et al. 2012). To check the contamination, resulting scaffolds were subjected to an NCBI BLAST database search, and scaffolds aligning to anything other than the

Streptomyces genus were discarded. The scaffold sequences were subjected to Pathosystems Resource Integration Center (PATRIC V3.6.9) (Snyder et al. 2007) and KmerFinder-3.2 (Larsen et al. 2014) searches to find the closely related genomes. To perform reference genome-based reordering, genome sequences of

Streptomyces cavourensis strain TJ430,

Streptomyces sp. CFMR 7,

Streptomyces cavourensis strain 1AS2a, and

Streptomyces atratus SCSIO-ZH16 were obtained from the NCBI microbial genomes database, followed by scaffolding using Multidraft-Based Scaffolder (MEDUSA) (Bosi et al. 2015). The completeness of gene space was estimated using BUSCO v5.2.2 (Simão et al. 2015), where the lineage dataset selection was streptomycetales_odb10. The annotation of the assembled genome of the SAI-25 strain was performed using the RAST (Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology) server (

https://rast.nmpdr.org/rast.cgi) via the RASTtk pipeline (accessed in December 2024)(Brettin et al. 2015).

2.5. Phylogenetic Relationship of SAI-25

To identify its taxonomic position in the Streptomyces genus, the genome sequence of the SAI-25 strain was uploaded to the Type (Strain) Genome Server (TYGS) (accessed in February 2025)(Meier-Kolthoff and Göker 2019). TYGS identified the closest type strains by constructing two phylogenetic trees based on (i) 16S rDNA gene sequences and (ii) whole genome sequences.

To obtain the taxonomic position of SAI-25 at a higher resolution, the species closest to SAI-25 in the TYGS phylogenetic tree, along with appropriate outgroups, were selected for further examination. The proteomes of i) all the strains belonging to the closest species, with completeness ≥99%, and having scaffold or higher-level assembly, ii) the three next closest type-strains in the TYGS phylogenetic tree, and iii) Peterkaempfera griseoplana, formerly Streptomyces griseoplanus (Madhaiyan et al. 2022), were retrieved from the NCBI database (accessed in March 2025). A phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the number of overlapping orthogroups among the above strains using the OrthoFinder tool (Version 3.0.1b1)(Emms and Kelly 2019).

2.6. Pan-Genome Analysis

The proteome (.faa) of all the species belonging to the Streptomyces genus with at least chromosome-level assembly and completeness of ≥98.5% were retrieved from the NCBI database (accessed in February 2025). Additionally, two more filtering criteria were applied: (i) inclusion of only reference genomes, RefSeq-annotated genomes, and those derived from type material, and (ii) exclusion of atypical genomes and metagenomically assembled genomes (MAGs). The proteome (.faa) of 98 species, including the SAI-25 strain and 97 other Streptomyces species retrieved from the NCBI database, were used as input for OrthoFinder (Version 3.0.1b1) to identify the unique genes of each species of the pangenome and the core orthogroups (orthogroups consisting of orthologs coming from all the pangenome species).

Genes not assigned to any orthogroups, and those belonging to SAI-25-specific orthogroups, were labelled as unique genes in this study. The unique genes of the SAI-25 strain were further analyzed to get functional insights using multiple strategies: the KEGG PATHWAY database (

https://www.genome.jp/kegg/) via ‘Automatic KO assignment and KEGG mapping service’ (BlastKOALA Version 3.1)(Kanehisa et al. 2016) and ‘KEGG Mapper – Reconstruct’ (Kanehisa and Sato 2020; Kanehisa et al. 2022), InterPro search (Blum et al. 2025), and NCBI BLAST followed by Reciprocal Best BLAST (Camacho et al. 2009) if no subsystem information was available in RAST annotation.

2.7. Identification of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) in SAI-25 Strain and Three Phylogenetically Closest S. cavourensis Strains

Genome-wide identification of secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters (BGCs) of SAI-25 and three phylogenetically closest S. cavourensis strains (A54, 1AS2a, and 2BA6PG) was performed using antiSMASH 7.1.0 (Blin et al. 2023). The regions in the SAI-25 genome that showed very little or no similarity to any known clusters were further analyzed using the KEGG PATHWAY database discussed in the previous section.

2.8. Identification of Potential Genes/Enzymes Responsible for Biosynthesis of an Insecticidal Diketopiperazine Derivative, Cyclo(Trp-Phe)

The SAI-25 strain was reported to have activity of one of the Cyclodipeptides (CDPs), Cyclo(Trp-Phe). The Cyclodipeptides are typically synthesised by two unrelated biosynthetic enzyme families: by non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) or by cyclodipeptide synthases (CDPSs). To identify NRPS and CDPSs members in SAI-25, the Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) profiles of NRPS’ three domains, namely, i) Adenylation(A)-domain (responsible for binding and activation of amino acids; Pfam-ID: PF00501), ii) peptidyl carrier protein(PCP)-domain or the Thiolation(T)-domain (for loading the activated amino acid onto this by A-domain; Pfam-ID: PF00550), and iii) Condensation(C)-domain (for catalysing the peptide bond formation between two T-domain bounded amino acids; Pfam-ID: PF00668); and CDPSs enzyme family (Pfam-ID: PF16715), were downloaded from the Pfam database (Mishra et al. 2017; Mistry et al. 2021; Widodo and Billerbeck 2023). The

hmmsearch (HMMER 3.3.2) (

http://hmmer.org) for all the above HMM profiles were carried out against the SAI-25 strain proteome, constraining the e-value to ≤0.01.

To predict the amino acid substrate(s) that the NRPSs would bind to, the SAI-25 proteins, showing significant hits to all three domains mentioned above, were selected. The A-domain sequences of such proteins were extracted and examined for two amino-acid substrates (tryptophan and phenylalanine) using substrate-binding specific HMM profiles from the “Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetase Substrate Predictor” database (

https://nrpssp.usal.es/download.php) (Prieto et al. 2012).

Alternatively, the BGCs prediction tool not only identified NRPSs but also their amino acid substrates and products. Thus, the results of antiSMASH were analyzed to look for any NRPSs whose predicted substrates were tryptophan and/or phenylalanine.

2.9. Genes/Pathways Underlying PGP Features

Seven plant growth-promoting (PGP) and biocontrol traits (Siderophore+, chitinase+, cellulase+, lipase+, protease+, indole-3-acetic acid+, and hydrocyanic acid+) were observed in SAI-25 strain through biochemical assays (

Table 1). Potential genes and pathways associated with the above-mentioned PGP and biocontrol traits were identified as described in our previous work (Gandham et al. 2024). Briefly, using the KEGG PATHWAY database, keyword searches in the RAST annotation, BLAST searches against the SAI-25 strain proteome, and pan-genome-wide BLAST searches to detect possible orthologs that the KEGG PATHWAY database may have missed.

The signal peptides and the sub-cellular localization of the identified cellulases, chitinases, lipases, and proteases were predicted using a machine learning model, namely SignalP 6.0 (Teufel et al. 2022), and a multiclass subcellular location prediction tool for prokaryotic proteins, namely DeepLocPro 1.0 (Moreno et al. 2024). Additionally, the identified cellulases and chitinases were classified into their respective protein families using the dbCAN3 server (automated Carbohydrate-active enzyme ANnotation)(accessed in July 2025)(Zheng et al. 2023). Similarly, the protein families/domains of the identified proteases and lipases were detected using InterPro (accessed in July 2025).

3. Results

3.1. Features of Genome Assembly of Streptomyces sp. SAI-25

An isolate from the rice rhizospheric soil was earlier characterized for having several plant-growth-promoting and biocontrol features (

Table 1)(Vijayabharathi et al. 2014). To examine the genetic or genomic basis of PGP features and to explore its biosynthetic potential, its whole genome was deeply sequenced. A total of ~5.1 million paired-end and ~13.5 million mate-pair raw reads were generated after sequencing, which were reduced to ~4.9 million and ~10.4 million reads, respectively, after their quality check (

Table 2).

After

de novo assembly of clean reads followed by scaffolding, a single scaffold of ~7.7 million bp in length was obtained. Standard assembly statistics showed a high GC content of 72.1%, a characteristic of Actinomycetes, and a very minimal number of anonymous nucleotides (0.25%) (

Table 3).

To assess the quality of genome assembly, out of 1579 reference Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCOs) derived from 145 genomes belonging to order streptomycetales, 1567 (99.2%) were complete (C), two were completely duplicated (D), four were fragmented (F) and eight were missing (M) in the SAI-25 strain assembly (Fig. S1). The complete BUSCOs over 99% indicated a very high degree of completeness of the generated assembly.

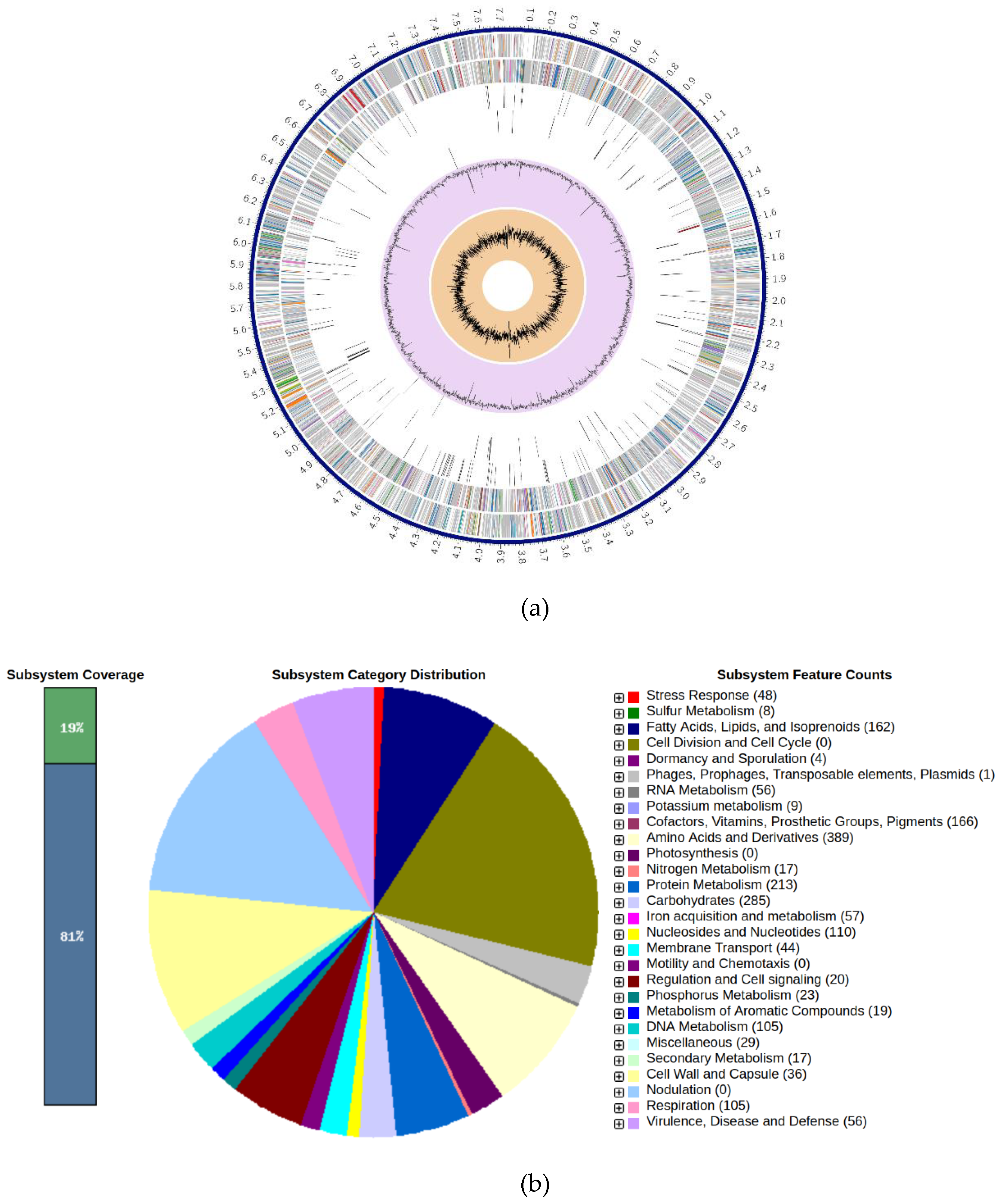

The annotation of the SAI-25 genome showed that it has 6,923 coding sequence regions (88.91%) with a mean length of 990 bp. It also consisted of 74 tRNA genes with a mean length of 76 bp, three rRNA genes with a mean length of 1,595 bp, 152 repeats with a mean length of 127 bp, and 81 CRISPR spacers with a mean length of 32 bp. A total of 4,560 (65.86%) proteins were assigned functional annotation, while 2,363 (34.13%) proteins were assigned as hypothetical (Tables 3, S1; a).

Among the 6,923 coding sequence regions, only 1,269 (19%) were classified into subsystems, comprising 1,212 non-hypothetical proteins and 57 hypothetical proteins. Amino acids and derivatives (389) were the most predominant subsystem feature, followed by carbohydrates (285), protein metabolism (213), cofactors, vitamins, prosthetic groups, pigments (166), fatty acids, lipids, and isoprenoids (162), nucleosides and nucleotides (110), DNA metabolism (105), respiration (105), iron acquisition and metabolism (57), virulence, disease, and defense (56), RNA metabolism (56), stress response (48), membrane transport (44), cell wall and capsule (36) and others (Fig. 2b). Several genes associated with antibiotic resistance, drug targets, transporters, and virulence factors were identified (

Table 4). Antibiotic resistance genes, along with their associated antimicrobial resistance (AMR) mechanisms, were also identified (

Table 5).

Figure 2.

(a) Visualization of genome assembly and key features. The distribution of different genome features was provided as a circular graphical display. This includes, from outer to inner rings, the scaffolds, CDS on the forward strand, CDS on the reverse strand, RNA genes, CDS with homology to known antimicrobial resistance genes, CDS with homology to known virulence factors, GC content, and GC skew. (b) Summary of subsystems annotated by the RAST online server.

Figure 2.

(a) Visualization of genome assembly and key features. The distribution of different genome features was provided as a circular graphical display. This includes, from outer to inner rings, the scaffolds, CDS on the forward strand, CDS on the reverse strand, RNA genes, CDS with homology to known antimicrobial resistance genes, CDS with homology to known virulence factors, GC content, and GC skew. (b) Summary of subsystems annotated by the RAST online server.

3.2. Phylogenetic Relationship and Taxonomic Positioning of SAI-25:

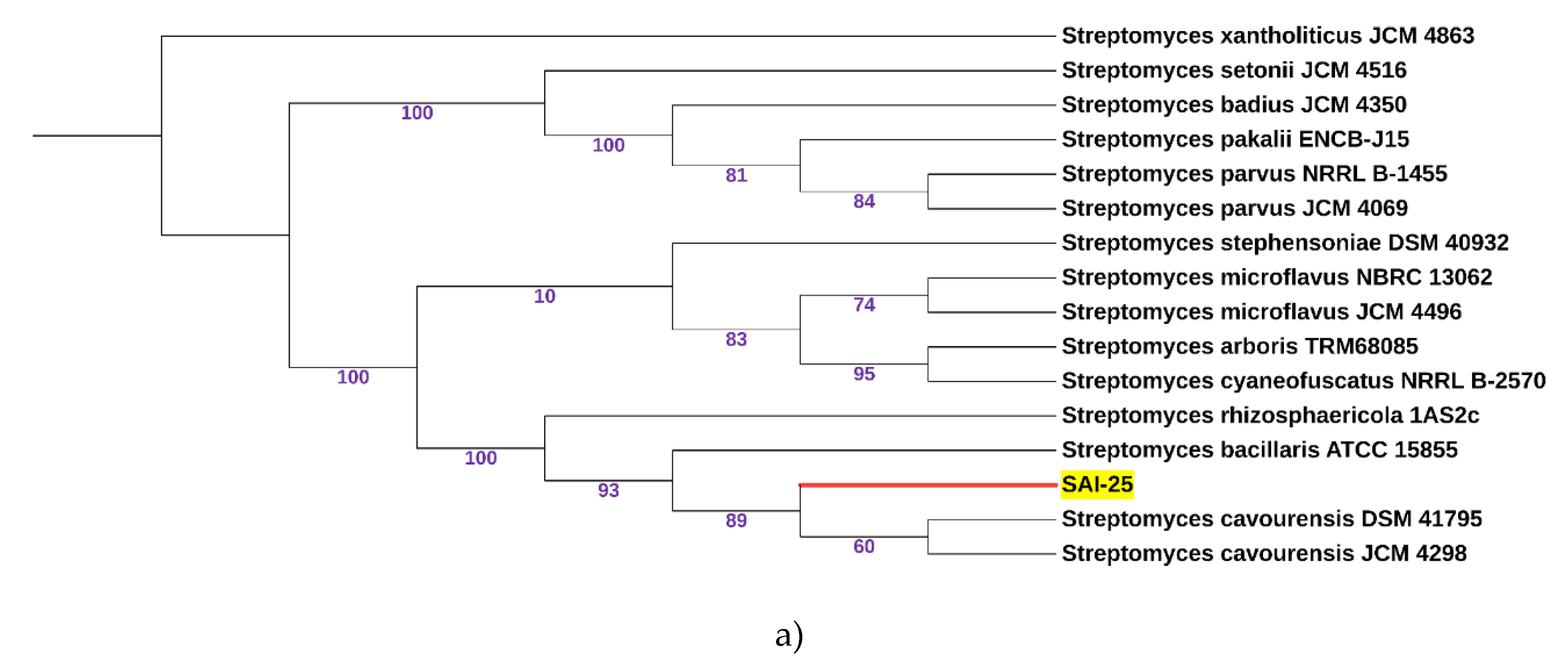

The SAI-25 strain, on its isolation, was initially assigned to Streptomyces griseoplanus based on the similarity of its amplified 16s rRNA sequence to database sequences (GenBank ID: KF770901) (Vijayabharathi et al. 2014). However, a recent study has reclassified this species to a novel genus in the family Streptomycetaceae, namely Peterkaempfera (Madhaiyan et al. 2022). This necessitated a re-examination of the phylogenetic relationship of SAI-25. Comparison of the complete gene sequence of 16S rRNA extracted from the SAI-25 genome against the database of type strains indicated that it is closest to two type strains belonging to Streptomyces cavourensis (Fig. S2). The high bootstrap value of the branch leading to the clade containing SAI-25 was high (83 out of 100), but a few other branches had lower bootstrap values (Fig. S2).

A whole-genome comparison with the genomes of type strains gave a similar relationship where the SAI-25 strain was still closely related to Streptomyces cavourensis, with an even higher bootstrap value (89 out of 100) (Fig. 3a). Thus, the phylogenetic tree obtained from TYGS (Fig. 3a) confirms that SAI-25, instead of genus Peterkaempfera, belongs to the genus Streptomyces.

To resolve the taxonomic positioning, the phylogenetic tree involving strains of Streptomyces cavourensis along with appropriate outgroups (three next closest type-strains in the TYGS phylogenetic tree, and Peterkaempfera griseoplana (formerly Streptomyces griseoplanus)) showed that SAI-25 was relatively more closer to a few strains of S. cavourensis than its remaining strains, indicating that SAI-25 belongs to cavourensis species (Fig. 3b). It is possibly a novel strain as evident by its phylogenetic position, being surrounded by the strains of Streptomyces cavourensis with a high bootstrap value (1 out of 1)(Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

(a) Phylogenetic tree based on whole genome sequences of the SAI-25 strain and the closest type strains in the TYGS server. (b) The phylogenetic tree based on the number of overlapping orthogroups among the strains of the species that was closest to SAI-25 in the TYGS phylogenetic tree, with completeness ≥99%, and having scaffold or higher level assembly along with appropriate outgroups (the three closest type-strains in the TYGS phylogenetic tree and Peterkaempfera griseoplana, formerly Streptomyces griseoplanus)(as per Fig. 3a) by OrthoFinder. The phylogenetic trees were visualised by the iTOL server (Interactive Tree Of Life) (Letunic and Bork 2024).

Figure 3.

(a) Phylogenetic tree based on whole genome sequences of the SAI-25 strain and the closest type strains in the TYGS server. (b) The phylogenetic tree based on the number of overlapping orthogroups among the strains of the species that was closest to SAI-25 in the TYGS phylogenetic tree, with completeness ≥99%, and having scaffold or higher level assembly along with appropriate outgroups (the three closest type-strains in the TYGS phylogenetic tree and Peterkaempfera griseoplana, formerly Streptomyces griseoplanus)(as per Fig. 3a) by OrthoFinder. The phylogenetic trees were visualised by the iTOL server (Interactive Tree Of Life) (Letunic and Bork 2024).

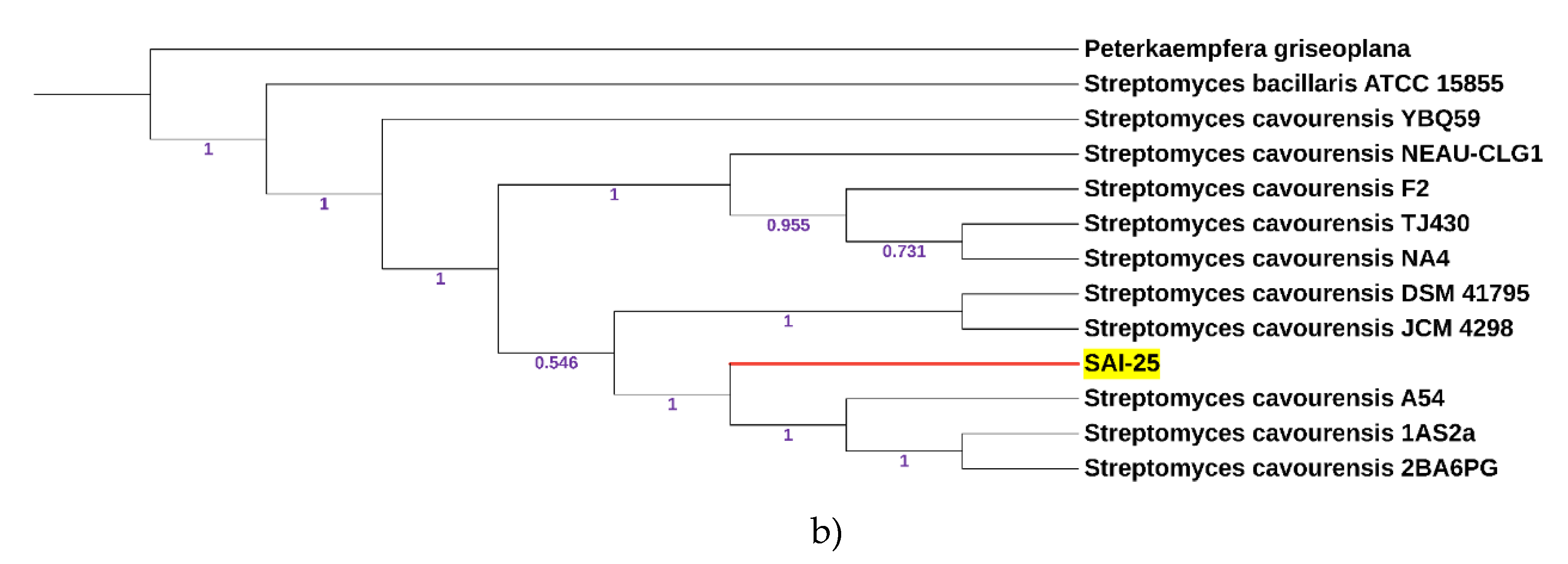

3.3. Core Ortho-Groups and Unique Genes of SAI-25

In addition to the establishment of phylogenetic relationships, a pan-genome analysis was conducted to examine the core and unique gene sets. Comparison of proteomes of 97 representative Streptomyces species along with SAI-25 gave a total of 15,225 orthogroups and 11,686 unassigned genes (see methods)(Table S2). Among the 15,225 orthogroups, 1,695 orthogroups (11.13%) were present in all the 98 species (core set), and 248 orthogroups comprising of orthologs belonging to a single species (species-specific orthogroups) (1.63%) were obtained (Table S3). A total of 418 unique genes (second highest in the pangenome) were observed in the SAI-25 strain (Fig. 4).

When these 418 unique genes were further analysed for functional characterisation by BLAST search in ‘Non-Redundant’ database, followed by ‘Reciprocal Best BLAST’; 147 out of 418 unique genes still showed partial but significant homology with genes/proteins belonging to

Streptomyces genus, with query and subject coverage ≥50% and e-value ≤0.01. Only 4 of the remaining 271 unique genes were functionally annotated (

Table 6).

Figure 4.

The phylogenetic tree based on the pan-genome analysis involving 97 good quality genome assemblies of Streptomyces and SAI-25 (highlighted in yellow)(see methods). Red bars indicate the number of unique genes. The phylogenetic tree was visualised by the iTOL server.

Figure 4.

The phylogenetic tree based on the pan-genome analysis involving 97 good quality genome assemblies of Streptomyces and SAI-25 (highlighted in yellow)(see methods). Red bars indicate the number of unique genes. The phylogenetic tree was visualised by the iTOL server.

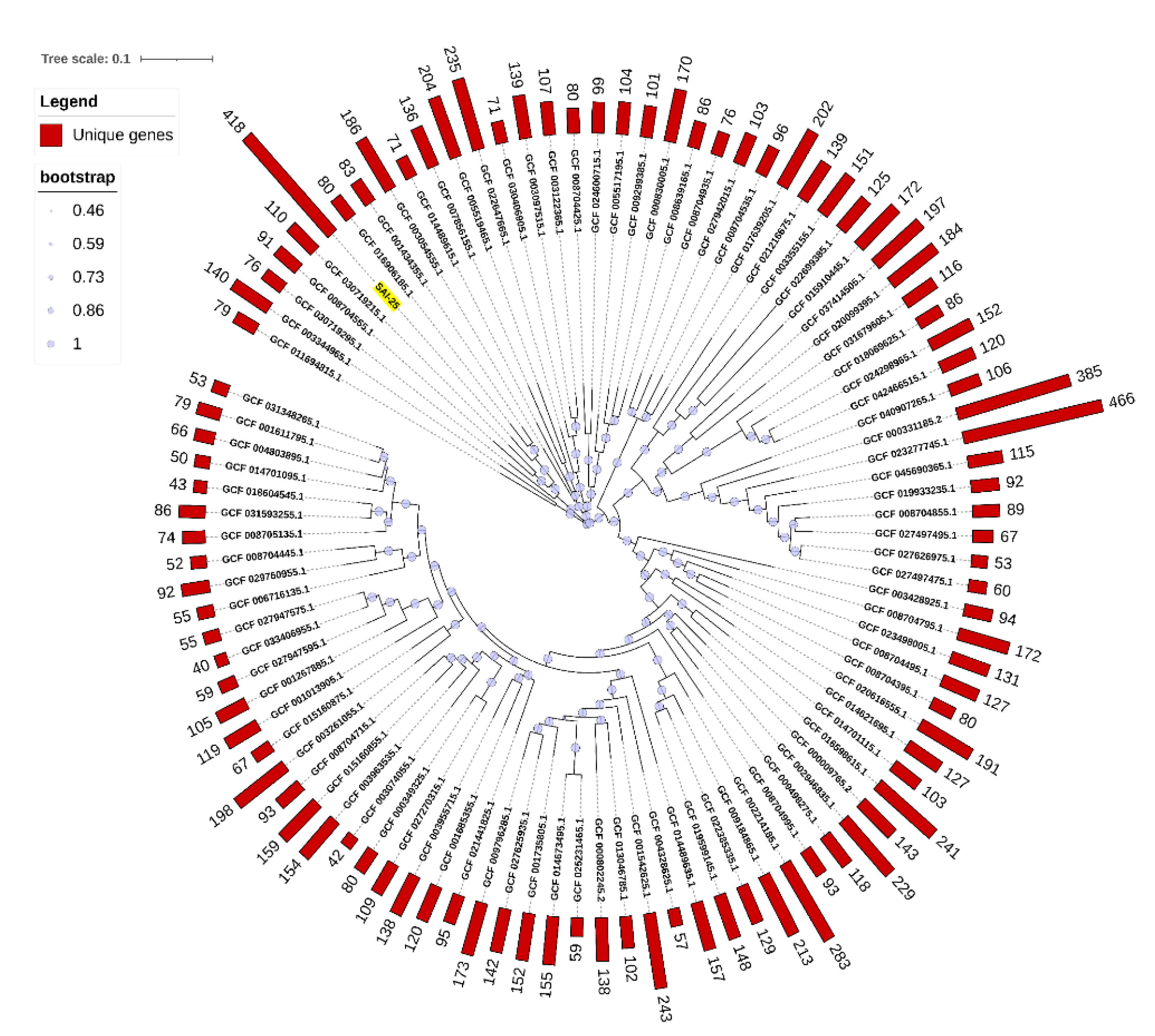

3.4. Secondary Metabolite Potential of SAI-25, and Its Comparison with the Closest Strains

A total of 32 biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) regions were predicted using antiSMASH (Fig. 5). Of these, 13 regions exhibited ≥81% similarity to known clusters. These 13 regions were responsible for biosynthesis of three siderophores (griseobactin, coelichelin and desferrioxamine B) (Lautru et al. 2005; Patzer and Braun 2010; Bellotti and Remelli 2021); geosmin, which not only tends to give earthy smell to soil but also regulates seed germination and acts as a chemical repellent/attractant to predators (nematodes and protists) and insects (Garbeva et al. 2023); naringenin, a flavonoid which alleviates abiotic stress (osmotic and salinity stress) and also contributes to pathogen resistance in plants (Yildiztugay et al. 2020; Ozfidan-Konakci et al. 2020; An et al. 2021; Sun et al. 2022); ectoine, an osmoprotectant which alleviates cadmium-induced stress in plants (Nazarov et al. 2022; Orhan et al. 2023); AmfS, whose derivative acts as extracellular morphogen for onset of aerial-mycelium (Ueda et al. 2002); keywimysin, a lasso peptide whose biological function remains unknown (Tietz et al. 2017); bafilomycin B1, a macrolide antibiotic which inhibits vacuolar-type ATPase (V-ATPase) (Bowman et al. 1988; Papini et al. 1993); 10-epi-HSAF (along with its analogues) which shows antifungal activities against plant pathogens (Hou et al. 2020); valinomycin, a potassium ionophore which demonstrates a diverse spectrum of biological activities (antibacterial, antifungal, insecticidal, etc.) (Huang et al. 2021); montanastatin, a cancer cell growth inhibitory cyclooctadepsipeptide (Pettit et al. 1999); alkylresorcinol, a polyketide which exhibits a wide range of bioactivities (antimicrobial, anti-cancer, antilipidemic, antioxidant, etc.) (Zabolotneva et al. 2022); and isorenieratene, a natural antioxidant and photo/UV damage inhibitor (Chen et al. 2019) (

Table 7)(Table S4).

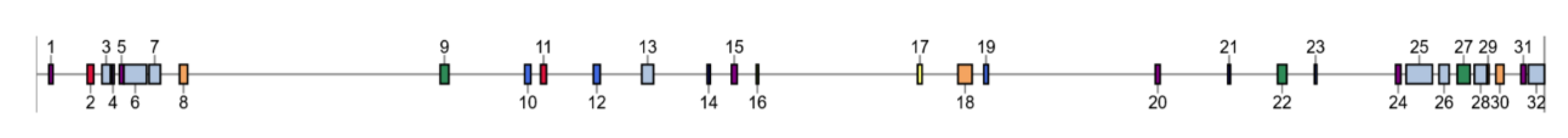

Figure 5.

Distribution of BGC regions within the genome of SAI-25 as predicted by antiSMASH. The color of the boxes has no relevance to their function.

Figure 5.

Distribution of BGC regions within the genome of SAI-25 as predicted by antiSMASH. The color of the boxes has no relevance to their function.

The regions that had very little or no similarity to any known cluster were subjected to KEGG PATHWAY analysis (see methods). Out of 19 such regions, only three regions (Region 18, 20, and 21) were found to be part of the existing biosynthetic pathways for secondary metabolites. Region 18 was responsible for biosynthesis of type II polyketide backbone (Fig. S3), region 20 for terpenoid backbone biosynthesis (Fig. S4), and region 21 for D-amino acid metabolism (Fig. S5).

Complete pathways for the biosynthesis of two more metabolites were discovered while examining the SAI-25 genome/proteome for genes and pathways associated with the seven PGP and biocontrol traits (discussed in section 3.6,

Table 1): (-)-Germacrene D, an aphid repellent sesquiterpenoids (Bruce et al. 2005), and (+)-Caryolan-1-ol, an antifungal volatile (Cho et al. 2017) (Fig. S6).

Comparison of the BGCs, that were annotated by antiSMASH in SAI-25, with the three closest strains of S. cavourensis namely, A54, 2BA6PG and 1AS2a (Fig. 3b), showed full conservation except for one (Table S5). The BGC namely, AmfS, was absent only in the strain 2BA6PG. In contrast, the BGC associated with melanin biosynthesis was predicted in all three strains but was absent in SAI-25. Another BGC involved in biosynthesis of a compound, SAL-2242, was detected only in the S. cavourensis strain 2BA6PG but not in others (Table S5).

3.5. Potential Genes/Enzymes Responsible for Biosynthesis of an Insecticidal Diketopiperazine Derivative, Cyclo(Trp-Phe)

Since the SAI-25 strain was earlier reported to have activity of one of the Cyclodipeptides (CDPs), Cyclo(Trp-Phe), so the SAI-25 genome was searched for the two biosynthetic enzyme families: Non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) and cyclodipeptide synthases (CDPSs). While no hits were observed for the CDPS enzyme family, a total of 15 proteins showed hits to all three domains of NRPSs. Out of these 15 proteins, 1 had three A-domains, 6 had two A-domains, and 8 had a single A-domain. Based on the RAST annotation, 8 of the above-mentioned proteins were recognised as polyketide synthase modules and related proteins; 3 were identified as hypothetical proteins; 3 were noted as siderophore biosynthesis non-ribosomal peptide synthetase modules; and 1 was annotated as capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis fatty acid synthase, WcbR. All 15 proteins identified above were part of one or the other BGCs as per the results of the antiSMASH (

Table 8). The A-domains of all 15 proteins were predicted to have affinity for multiple amino acids (including tryptophan and phenylalanine)(Table S6). Only one protein (ID: fig|1472664.5.peg.5776) was predicted by the antiSMASH tool to utilize phenylalanine and tryptophan, along with 3 more substrates (Ph-Gly, Tyr, and bOH-Tyr).

3.6. Genes/Pathway Underlying PGP Features

The SAI-25 strain genome was analysed to identify the pathways/genes responsible for the seven experimentally validated PGP and biocontrol traits (

Table 1). For the siderophores, the majority of the enzymes of a KEGG pathway named “siderophore group nonribosomal peptides” biosynthesis pathway were observed in the SAI-25 strain (

Table 9; Table S7; Fig. S7). Two key enzymes missing in the above pathways were later identified using the orthology-based approach, indicating their potential to synthesize almost all of the derivatives of chorismate, a key intermediate in the siderophore biosynthesis (Fig. S7; Table S7). Three additional BGCs responsible for the production of griseobactin, coelichelin, and desferrioxamine B were also observed in the SAI-25 strain (

Table 7).

Enzymes having a role in chitin metabolism, such as Chitinase (eleven copies), Chitodextrinase (one copy), beta-glycosyl hydrolase (four copies), beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase (one copy), and endochitinase (one copy), were identified in the SAI-25 strain genome (

Table 9; Table S8; Fig. S8). Out of the eighteen identified enzymes, fifteen were predicted to have extracellular localization. Among these fifteen enzymes, eleven were predicted to have standard secretory signal peptides transported by the

Sec translocon and cleaved by Signal Peptidase I (Sec/SPI), one predicted to have a

Tat signal peptides transported by the

Tat translocon and cleaved by Signal Peptidase I (Tat/SPI), and the remaining three were predicted to contain signal peptides but couldn’t be confidently classified into any of the known signal peptide categories. The majority of these fifteen enzymes belonged to the glycoside hydrolase (GH) family 18 (N=9), followed by GH family 3 (N=2), GH family 19 (N=2), and GH family 20 (N=3). The remaining 2 could not be confidently assigned to any known protein family of the database (Fig. S8; Table S8).

Cellulolytic enzymes, such as endoglucanase, glycoside hydrolase, cellulose 1,4-beta-cellobiosidase, and beta-glucosidase, were also present in the SAI-25 strain genome (

Table 9; Table S9; Fig. S9). Out of the fourteen identified enzymes, eight were predicted to have extracellular localization. Among these eight enzymes, two were predicted to have standard secretory signal peptides transported by the

Sec translocon and cleaved by Signal Peptidase I (Sec/SPI), one predicted to have a

Tat signal peptides transported by the

Tat translocon and cleaved by Signal Peptidase I (Tat/SPI), two predicted to have a lipoprotein signal peptides transported by the

Sec translocon and cleaved by Signal Peptidase II (Sec/SPII) and the remaining three were predicted to contain signal peptides but could not be confidently classified into any of the known signal peptide categories. Of these eight enzymes, three belonged to GH family 6, two to GH family 1, and one each to GH family 3 and 5. The remaining one could not be confidently assigned to any known protein family of the database (Fig. S9; Table S9).

Several kinds of lipases and proteases, which play a major role in plant growth and protection, were also identified in the SAI-25 genome (

Table 9; Tables S10, S11). Out of the twelve identified lipases, five were predicted to have extracellular localization. Among these five lipases, two were predicted to have standard secretory signal peptides transported by the

Sec translocon and cleaved by Signal Peptidase I (Sec/SPI), and the remaining three were predicted to have

Tat signal peptides transported by the

Tat translocon and cleaved by Signal Peptidase I (Tat/SPI). These lipases were predicted to have distinct protein families/domains (Table S10).

Out of the 69 identified proteases, 26 were predicted to have extracellular localization (

Table 9; Table S11). Among these 26 proteases, 21 were predicted to have standard secretory signal peptides transported by the

Sec translocon and cleaved by Signal Peptidase I (Sec/SPI), 4 were predicted to have a

Tat signal peptides transported by the

Tat translocon and cleaved by Signal Peptidase I (Tat/SPI), 2 were predicted to have a lipoprotein signal peptides transported by the

Sec translocon and cleaved by Signal Peptidase II (Sec/SPII) and the remaining 1 was predicted to contain signal peptides but could not be confidently classified into any of the known signal peptide categories. These 26 proteases were predicted to belong to distinct protein families/domains (Table S11).

The Indole-3-acetamide (IAM) pathway is one of the extensively studied pathways for the biosynthesis of Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA). In this pathway, tryptophan is converted to IAM, which is then hydrolysed to IAA. Two major enzymes are required for this pathway: tryptophan monooxygenase, which converts tryptophan to IAM, and indole-3-acetamide hydrolase for hydrolysis of IAM into IAA (Tang et al. 2023). BLAST search of tryptophan monooxygenase protein sequence against the SAI-25 strain proteome showed the presence of its ortholog. KEGG PATHWAY analysis identified two proteins that can convert IAM into IAA (

Table 9; Table S12; Fig. S10).

Three enzymes, hydrogen cyanide synthase subunit

HcnA, hydrogen cyanide synthase subunit

HcnB, and hydrogen cyanide synthase subunit

HcnC are required for biosynthesis of hydrocyanic acid (Laville et al. 1998). Through pan-genome-wide BLAST, one ortholog of

HcnA, one ortholog of

HcnB, and three orthologs of

HcnC were identified (

Table 9; Table S13).

4. Discussion

4.1. SAI-25’s Chromosome-Level Assembly with High Completeness Will Be a Valuable Resource for Streptomyces Genome Mining

The NCBI genome database currently has 11,237

Streptomyces genomes, out of which only 1,357 (~12%) are at chromosome level or higher assembly level (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/; accessed on April 2025). The single linear genome of SAI-25, with completeness >99% and total gap size of <20 Kb, makes it among the good quality assemblies. For a meaningful and accurate pan-genome analysis or genome mining for BGCs, the quality of assembly plays a key role, in particular, the completeness and extent of fragmentation (Lee et al. 2020).

Even for the high-quality assembly, concerns regarding the relatively higher number of hypothetical genes were raised earlier (Lee et al. 2020), and even in this genome assembly, a slightly higher fraction of hypothetical genes were observed (34%). Among the set of unique genes, surprisingly, the majority of them were hypothetical genes, indicating the limitations of annotation pipelines when it comes to species-specific genes.

4.2. Phylogenetic Analysis Corrected the Species Name from S. griseoplanus to S. cavourensis

When the SAI-25 strain was first reported for its biocontrol and PGP features, it was initially assigned to S. griseoplanus species based on the 16S rRNA sequencing (Vijayabharathi et al. 2014); the taxon has recently been re-assigned to a separate genus, namely, Peterkaempfera griseoplanus, as per the NCBI taxonomy database (Madhaiyan et al. 2022). However, the availability of whole genome sequences led to the re-examination of the taxonomic assignment, and S. cavourensis emerged as the species based on comparison with whole genomes of type strains as well as those of strains of the species that were closest to the SAI-25.

S. cavourensis strains have earlier been isolated, largely from soil, and almost all were found, either experimentally or computationally, to have potential for biosynthesis of several active compounds or secondary metabolites (Wang et al. 2018; Vargas Hoyos et al. 2019; Kaaniche et al. 2020; Creencia et al. 2021). For instance, S. cavourensis strain 1AS2a, isolated from the wheat rhizosphere in the Brazilian Neotropical savanna, has a genome size similar to SAI-25 (~7.6 Mb), with a similar number of BGCs (n=30), and also exhibited strong antimicrobial activities (Vargas Hoyos et al. 2019). Although two additional BGCs were observed through our analysis in this strain, compared to the original report (Vargas Hoyos et al. 2019), however, both were also conserved in SAI-25 (Table S5).

As far as the biosynthetic potential of different strains of S. cavourensis is concerned, the TJ430 strain isolated from mountain soil from China had proteins related to antibiotic synthesis, and tolerance or detoxification of metals (Wang et al. 2018). Another strain, TN638, isolated from an industrial waste soil, was detected having three cyclodipeptides or diketopiperazine (DKP) derivatives, and four macrotetrolides (Kaaniche et al. 2020); both groups of compounds showed strong antibacterial activity against A. tumefaciens ATCC 23308 and S. typhimurium ATCC 14028.

4.3. Presence of Sixteen Annotated and the Same Unannotated BGCs Highlights its PGP and Industrial Potential

Large-scale genome mining of Streptomyces genomes (n=1,110) has shown that Streptomyces bacteria carry BGCs in the range of 8–83 per genome, which weakly correlated with the genome size (Belknap et al. 2020). The SAI-25 genome was predicted to have 32 BGCs, which was close to the mean for this genus.

The S. griseoplanus SAI-25 used in this study exhibited insecticidal properties such as antifeedant, insecticidal, and pupicidal activity against H. armigera. The SAI-25 was also reported to have antifungal activity against the charcoal rot of sorghum pathogen Macrophomina phaseolina (Vijayabharathi et al. 2018c). The BGC prediction in the SAI-25 genome showed the presence of several metabolites with biocontrol properties. For example, Valinomycin, a potassium ionophore, reportedly has a diverse spectrum of biological activities, such as antibacterial, antifungal, and insecticidal (Huang et al. 2021). The BGC was observed for another broad-spectrum biocontrol agent, Bafilomycin B1, a macrolide antibiotic. The Bafilomycin B1 and C1 from S. cavourensis NA4 showed significant inhibitory activities against a variety of Fusarium spp. and R. solani, while being inactive against Setosphaeria turcica (Pan et al. 2015); thus, they could be used as potential biocontrol agents for soil-borne fungal diseases of plants. Yet another antifungal metabolite, a polycyclic tetramate macrolactams (PTMs) type 10-epi-HSAF, showed modest antifungal properties (Hou et al. 2020).

Besides the BGCs for biocontrol, several others were annotated for plant-growth promotion. The SAI-25 genome has BGCs for biosynthesis of several siderophores, such as Griseobactin, Coelichelin, and Desferrioxamine B, indicating their role in mineral mobilisation. In addition to siderophore, a few metabolites having a role in abiotic stress were also found (Naringenin, Ectoine, etc.). Beyond the agriculturally important secondary metabolites, SAI-25 was predicted to have BGCs with even chemotherapeutic potential, such as Alkylresorcinol and Montanastatin. However, these two metabolites didn’t overlap with the list of 38 BGCs with known chemotherapeutic potential found in Streptomyces species (Belknap et al. 2020). Notably, the BGCs for these two metabolites were also conserved in the three phylogenetically closest cavourensis strains to SAI-25, namely A54, 2BA6PG, and 1AS2a (Fig. 3b; Table S5), highlighting the diversity and richness prevalent in the Streptomyces genus. Surprisingly, the most common chemotherapeutic gene cluster in Streptomyces, namely, the macrolide FD-891, was missing in SAI-25 and its three phylogenetically closest cavourensis species.

The very high conservation of annotated BGCs observed among the SAI-25 strain and its three closest S. cavourensis strains (A54, 2BA6PG, and 1AS2a)(Fig. 3b), despite geographically distant locations of their isolation, suggests they either shared a common ancestor or action of selective pressures have maintained the composition of the BGCs across different locations/environments.

In addition to BGCs with PGP and biocontrol traits, several secretory hydrolytic enzymes, namely lipases, proteases, cellulases, and chitinases, were also identified (

Table 9). While these hydrolytic enzymes are likely to play a major role in biocontrol of phytopathogens (Jadhav et al., 2017; Saberi Riseh et al., 2024), however reasons for the presence of a relatively large number and their individual activity in response to internal or external stimuli remain unknown. Similarly, the presence of a complete pathway for biosynthesis of IAA and HCN in the SAI-25 strain highlights both its potential and conservation of genetic components for plant growth and biocontrol (Sehrawat et al. 2022; Orozco-Mosqueda et al. 2023).

4.4. Limited Success in Prediction of Genes/BGCs for cyclo(Trp-Phe) Biosynthesis Opens the Scope for Further Characterization

SAI-25 strain was earlier reported to produce an insecticidal cyclodipeptide, cyclo(Trp-Phe) (Sathya et al. 2016), and the BGC prediction in the SAI-25 genome also showed the presence of a few distinct classes of cyclopeptides, such as Montanastatin, a cyclooctadepsipeptide (CODP). The computational prediction of genes/BGCs for the cyclo(Trp-Phe) could only narrow down to a few candidate genes, thus remaining incomplete. Although cyclodipeptides have been reported in other strains of this species, such as S. cavourensis TN638 (Kaaniche et al. 2020), and strains of other species, such as S. leeuwenhoekii NRRL B-24963 (Zhang et al. 2021), eight different strains of Streptomyces (Liu et al. 2018); however, the substrate diversity among the cyclodipeptides could be one of the main challenges for their characterization.

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

Only 4 out of the 271 unique genes identified in the SAI-25 strain could be annotated, indicating the need for a more effective annotation pipeline or software. Moreover, a huge number of hypothetical genes were also found in the genome annotation. Although the SAI-25 strain has the potential to biosynthesize various secondary metabolites with a broad range of biological functions, the extent of their production and the specific conditions that stimulate their biosynthesis require further investigation. In addition, a few of the BGCs remain unannotated including the partially annotated BGC for Cyclo(Trp-Phe). The anti-pesticidal and anti-fungal activity of SAI-25 should be further explored as an alternative pest management tool that can help in exploring its utility in sustainable agriculture.

Clinical Trial Number

Not applicable.

Permission to publish

Each author made a contribution to the collection and analysis of the data. The final version of the text has been reviewed and approved by all authors, who have given their agreement for publication.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, RS, AR, VT and SG; Formal analysis, SN, PG and VT; Methodology, SN, PG, SV, PR, VT and SG; Supervision, AR, VT and SG; Visualization, SN and PG; Writing – original draft, SN, PG and VT; Writing – review & editing, SN, SG and VT. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no formal external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw reads of whole genome sequencing of microbial strain and its annotation can be accessed from NCBI using Bioproject ID- PRJNA1248749.

Acknowledgments

SN gratefully acknowledges the partial financial support (stipend) provided by the University of Hyderabad–Institution of Eminence (UoH-IoE) grant. VT acknowledges the partial financial support for sequencing work received through the DBT-Ramalingaswami Re-Entry Fellowship. We also acknowledge the Department of Biotechnology–BUILDER program for financial support in the procurement of consumables, and the CMSD High-Performance Computing facility, UoH, for assistance with data analysis. We extend our sincere thanks to Angeo Saji for his valuable suggestions on data analysis. .

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Aggarwal N, Thind SK, Sharma S (2016) Role of Secondary Metabolites of Actinomycetes in Crop Protection. In: Subramaniam G, Arumugam S, Rajendran V (eds) Plant Growth Promoting Actinobacteria.

- An J, Kim SH, Bahk S, Vuong UT, Nguyen NT, Do HL, Kim SH, Chung WS (2021) Naringenin Induces Pathogen Resistance Against Pseudomonas syringae Through the Activation of NPR1 in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci 12:672552. [CrossRef]

- Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, Lesin VM, Nikolenko SI, Pham S, Prjibelski AD, Pyshkin AV, Sirotkin AV, Vyahhi N, Tesler G, Alekseyev MA, Pevzner PA (2012) SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. Journal of Computational Biology 19(5):455–477. [CrossRef]

- Belknap KC, Park CJ, Barth BM, Andam CP (2020) Genome mining of biosynthetic and chemotherapeutic gene clusters in Streptomyces bacteria. Sci Rep 10(1):2003. [CrossRef]

- Bellotti D, Remelli M (2021) Deferoxamine B: A Natural, Excellent and Versatile Metal Chelator. Molecules 26(11):3255. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya C, Bakshi U, Mallick I, Mukherji S, Bera B, Ghosh A (2017) Genome-Guided Insights into the Plant Growth Promotion Capabilities of the Physiologically Versatile Bacillus aryabhattai Strain AB211. Front Microbiol 8. [CrossRef]

- Blin K, Shaw S, Augustijn HE, Reitz ZL, Biermann F, Alanjary M, Fetter A, Terlouw BR, Metcalf WW, Helfrich EJN, van Wezel GP, Medema MH, Weber T (2023) antiSMASH 7.0: new and improved predictions for detection, regulation, chemical structures and visualisation. Nucleic Acids Research 51(W1):W46–W50. [CrossRef]

- Blum M, Andreeva A, Florentino LC, Chuguransky SR, Grego T, Hobbs E, Pinto BL, Orr A, Paysan-Lafosse T, Ponamareva I, Salazar GA, Bordin N, Bork P, Bridge A, Colwell L, Gough J, Haft DH, Letunic I, Llinares-López F, Marchler-Bauer A, Meng-Papaxanthos L, Mi H, Natale DA, Orengo CA, Pandurangan AP, Piovesan D, Rivoire C, Sigrist CJA, Thanki N, Thibaud-Nissen F, Thomas PD, Tosatto SCE, Wu CH, Bateman A (2025) InterPro: the protein sequence classification resource in 2025. Nucleic Acids Research 53(D1):D444–D456. [CrossRef]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B (2014) Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30(15):2114–2120. [CrossRef]

- Bosi E, Donati B, Galardini M, Brunetti S, Sagot M-F, Lió P, Crescenzi P, Fani R, Fondi M (2015) M E D U S A : a multi-draft based scaffolder. Bioinformatics 31(15):2443–2451. [CrossRef]

- Bowman EJ, Siebers A, Altendorf K (1988) Bafilomycins: a class of inhibitors of membrane ATPases from microorganisms, animal cells, and plant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85(21):7972–7976. [CrossRef]

- Brettin T, Davis JJ, Disz T, Edwards RA, Gerdes S, Olsen GJ, Olson R, Overbeek R, Parrello B, Pusch GD, Shukla M, Thomason JA, Stevens R, Vonstein V, Wattam AR, Xia F (2015) RASTtk: A modular and extensible implementation of the RAST algorithm for building custom annotation pipelines and annotating batches of genomes. Sci Rep 5(1):8365. [CrossRef]

- Bruce TJ, Birkett MA, Blande J, Hooper AM, Martin JL, Khambay B, Prosser I, Smart LE, Wadhams LJ (2005) Response of economically important aphids to components of Hemizygia petiolata essential oil. Pest Management Science 61(11):1115–1121. [CrossRef]

- Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL (2009) BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10(1):421. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Guo M, Yang J, Chen J, Xie B, Sun Z (2019) Potential TSPO Ligand and Photooxidation Quencher Isorenieratene from Arctic Ocean Rhodococcus sp. B7740. Marine Drugs 17(6):316. [CrossRef]

- Cho G, Kim J, Park CG, Nislow C, Weller DM, Kwak Y-S (2017) Caryolan-1-ol, an antifungal volatile produced by Streptomyces spp., inhibits the endomembrane system of fungi. Open Biol 7(7):170075. [CrossRef]

- Creencia AR, Alcantara EP, Diaz MGQ, Monsalud RG (2021) Draft genome sequence of a Philippine mangrove soil actinomycete with insecticidal activity reveals potential as a source of other valuable secondary metabolites.

- Emms DM, Kelly S (2019) OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol 20(1):238. [CrossRef]

- Gandham P, Vadla N, Saji A, Srinivas V, Ruperao P, Selvanayagam S, Saxena RK, Rathore A, Gopalakrishnan S, Thakur V (2024) Genome assembly, comparative genomics, and identification of genes/pathways underlying plant growth-promoting traits of an actinobacterial strain, Amycolatopsis sp. (BCA-696). Sci Rep 14(1):15934. [CrossRef]

- Garbeva P, Avalos M, Ulanova D, Van Wezel GP, Dickschat JS (2023) Volatile sensation: The chemical ecology of the earthy odorant geosmin. Environmental Microbiology 25(9):1565–1574. [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan S, Sharma R, Srinivas V, Naresh N, Mishra SP, Ankati S, Pratyusha S, Govindaraj M, Gonzalez SV, Nervik S, Simic N (2020) Identification and Characterization of a Streptomyces albus Strain and Its Secondary Metabolite Organophosphate against Charcoal Rot of Sorghum. Plants 9(12):1727. [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan S, Srinivas V, Alekhya G, Prakash B (2015a) Effect of plant growth-promoting Streptomyces sp. on growth promotion and grain yield in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L). 3 Biotech 5(5):799–806. [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan S, Srinivas V, Alekhya G, Prakash B, Kudapa H, Rathore A, Varshney RK (2015b) The extent of grain yield and plant growth enhancement by plant growth-promoting broad-spectrum Streptomyces sp. in chickpea. SpringerPlus 4(1):31. [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan S, Srinivas V, Chand U, Pratyusha S, Samineni S (2022) Streptomyces consortia-mediated plant growth-promotion and yield performance in chickpea. 3 Biotech 12(11):318. [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan S, Srinivas V, Naresh N, Pratyusha S, Ankati S, Madhuprakash J, Govindaraj M, Sharma R (2021) Deciphering the antagonistic effect of Streptomyces spp. and host-plant resistance induction against charcoal rot of sorghum. Planta 253(2):57. [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan S, Upadhyaya H, Vadlamudi S, Humayun P, Vidya MS, Alekhya G, Singh A, Vijayabharathi R, Bhimineni RK, Seema M, Rathore A, Rupela O (2012) Plant growth-promoting traits of biocontrol potential bacteria isolated from rice rhizosphere. SpringerPlus 1(1):71. [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan S, Vadlamudi S, Apparla S, Bandikinda P, Vijayabharathi R, Bhimineni RK, Rupela O (2013) Evaluation of Streptomyces spp. for their plant-growth-promotion traits in rice. Can J Microbiol 59(8):534–539. [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan S, Vadlamudi S, Bandikinda P, Sathya A, Vijayabharathi R, Rupela O, Kudapa H, Katta K, Varshney RK (2014) Evaluation of Streptomyces strains isolated from herbal vermicompost for their plant growth-promotion traits in rice. Microbiological Research 169(1):40–48. [CrossRef]

- Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G (2013) QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 29(8):1072–1075. [CrossRef]

- Hou L, Liu Z, Yu D, Li H, Ju J, Li W (2020) Targeted isolation of new polycyclic tetramate macrolactams from the deepsea-derived Streptomyces somaliensis SCSIO ZH66. Bioorganic Chemistry 101:103954. [CrossRef]

- Huang S, Liu Y, Liu W-Q, Neubauer P, Li J (2021) The Nonribosomal Peptide Valinomycin: From Discovery to Bioactivity and Biosynthesis. Microorganisms 9(4):780. [CrossRef]

- Jayasekara S, Ratnayake R (2019) Microbial Cellulases: An Overview and Applications. In: Rodríguez Pascual A, E. Eugenio Martín M (eds) Cellulose.

- Kaaniche F, Hamed A, Elleuch L, Chakchouk-Mtibaa A, Smaoui S, Karray-Rebai I, Koubaa I, Arcile G, Allouche N, Mellouli L (2020) Purification and characterization of seven bioactive compounds from the newly isolated Streptomyces cavourensis TN638 strain via solid-state fermentation. Microbial Pathogenesis 142:104106. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa M, Sato Y (2020) KEGG Mapper for inferring cellular functions from protein sequences. Protein Science 29(1):28–35. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Kawashima M (2022) KEGG mapping tools for uncovering hidden features in biological data. Protein Science 31(1):47–53. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Morishima K (2016) BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG Tools for Functional Characterization of Genome and Metagenome Sequences. Journal of Molecular Biology 428(4):726–731. [CrossRef]

- Klosterman HJ, Lamoureux GL, Parsons JL (1967) Isolation, Characterization, and Synthesis of Linatine. A Vitamin B6 Antagonist from Flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum)*. Biochemistry 6(1):170–177. [CrossRef]

- Larsen MV, Cosentino S, Lukjancenko O, Saputra D, Rasmussen S, Hasman H, Sicheritz-Pontén T, Aarestrup FM, Ussery DW, Lund O (2014) Benchmarking of Methods for Genomic Taxonomy. J Clin Microbiol 52(5):1529–1539. [CrossRef]

- Lautru S, Deeth RJ, Bailey LM, Challis GL (2005) Discovery of a new peptide natural product by Streptomyces coelicolor genome mining. Nat Chem Biol 1(5):265–269. [CrossRef]

- Laville J, Blumer C, Von Schroetter C, Gaia V, Défago G, Keel C, Haas D (1998) Characterization of the hcnABC Gene Cluster Encoding Hydrogen Cyanide Synthase and Anaerobic Regulation by ANR in the Strictly Aerobic Biocontrol Agent Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0. J Bacteriol 180(12):3187–3196. [CrossRef]

- Lee N, Hwang S, Kim J, Cho S, Palsson B, Cho B-K (2020) Mini review: Genome mining approaches for the identification of secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters in Streptomyces. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 18:1548–1556. [CrossRef]

- Letunic I, Bork P (2024) Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Research 52(W1):W78–W82. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Yu H, Li S-M (2018) Expanding tryptophan-containing cyclodipeptide synthase spectrum by identification of nine members from Streptomyces strains. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 102(10):4435–4444. [CrossRef]

- Luo R, Liu B, Xie Y, Li Z, Huang W, Yuan J, He G, Chen Y, Pan Q, Liu Y, Tang J, Wu G, Zhang H, Shi Y, Liu Y, Yu C, Wang B, Lu Y, Han C, Cheung DW, Yiu S-M, Peng S, Xiaoqian Z, Liu G, Liao X, Li Y, Yang H, Wang J, Lam T-W, Wang J (2012) SOAPdenovo2: an empirically improved memory-efficient short-read de novo assembler. Gigascience 1(1):2047-217X-1–18. [CrossRef]

- Madhaiyan M, Saravanan VS, See-Too W-S, Volpiano CG, Sant’Anna FH, Faria Da Mota F, Sutcliffe I, Sangal V, Passaglia LMP, Rosado AS (2022) Genomic and phylogenomic insights into the family Streptomycetaceae lead to the proposal of six novel genera. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 72(10). [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff JP, Göker M (2019) TYGS is an automated high-throughput platform for state-of-the-art genome-based taxonomy. Nat Commun 10(1):2182. [CrossRef]

- Mishra A, Choi J, Choi S-J, Baek K-H (2017) Cyclodipeptides: An Overview of Their Biosynthesis and Biological Activity. Molecules 22(10):1796. [CrossRef]

- Mistry J, Chuguransky S, Williams L, Qureshi M, Salazar GA, Sonnhammer ELL, Tosatto SCE, Paladin L, Raj S, Richardson LJ, Finn RD, Bateman A (2021) Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Research 49(D1):D412–D419. [CrossRef]

- Moreno J, Nielsen H, Winther O, Teufel F (2024) Predicting the subcellular location of prokaryotic proteins with DeepLocPro. Bioinformatics 40(12). [CrossRef]

- Nazarov AV, Anan’ina LN, Gorbunov AA, Pyankova AA (2022) Bacteria Producing Ectoine in the Rhizosphere of Plants Growing on Technogenic Saline Soil. Eurasian Soil Sc 55(8):1074–1081. [CrossRef]

- Orhan F, Parlak KU, Tabay D, Bozarı S (2023) Alleviation of the Cadmium Toxicity by Application of a Microbial Derived Compound, Ectoine. Water Air Soil Pollut 234(8):534. [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Mosqueda MaDC, Santoyo G, Glick BR (2023) Recent Advances in the Bacterial Phytohormone Modulation of Plant Growth. Plants 12(3):606. [CrossRef]

- Ozfidan-Konakci C, Yildiztugay E, Alp FN, Kucukoduk M, Turkan I (2020) Naringenin induces tolerance to salt/osmotic stress through the regulation of nitrogen metabolism, cellular redox and ROS scavenging capacity in bean plants. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 157:264–275. [CrossRef]

- Pan H-Q, Yu S-Y, Song C-F, Wang N, Hua H-M, Hu J-C, Wang S-J (2015) Identification and Characterization of the Antifungal Substances of a Novel Streptomyces cavourensis NA4. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 25(3):353–357. [CrossRef]

- Papini E, Bernard M, Bugnoli M, Milia E, Rappuoli R, Montecucco C (1993) Cell vacuolization induced by Helicobacter pylori : Inhibition by bafilomycins A1, B1, C1 and D. FEMS Microbiology Letters 113(2):155–159. [CrossRef]

- Patzer SI, Braun V (2010) Gene Cluster Involved in the Biosynthesis of Griseobactin, a Catechol-Peptide Siderophore of Streptomyces sp. ATCC 700974. J Bacteriol 192(2):426–435. [CrossRef]

- Pettit GR, Tan R, Melody N, Kielty JM, Pettit RK, Herald DL, Tucker BE, Mallavia LP, Doubek DL, Schmidt JM (1999) Antineoplastic agents. Part 409: Isolation and structure of montanastatin from a terrestrial actinomycete [1]1Dedicated to the memory of Professor Sir Derek H. R. Barton (1918–1998), a great chemist and friend.1. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 7(5):895–899. [CrossRef]

- Prieto C, García-Estrada C, Lorenzana D, Martín JF (2012) NRPSsp: non-ribosomal peptide synthase substrate predictor. Bioinformatics 28(3):426–427. [CrossRef]

- Saberi Riseh R, Vatankhah M, Hassanisaadi M, Barka EA (2024) Unveiling the Role of Hydrolytic Enzymes from Soil Biocontrol Bacteria in Sustainable Phytopathogen Management. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 29(3). [CrossRef]

- Sambangi P, Gopalakrishnan S (2023) Streptomyces-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles for enhanced growth, yield, and grain nutrients in chickpea. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 47:102567. [CrossRef]

- Sathya A, Vijayabharathi R, Kumari BR, Srinivas V, Sharma HC, Sathyadevi P, Gopalakrishnan S (2016) Assessment of a diketopiperazine, cyclo(Trp-Phe) from Streptomyces griseoplanus SAI-25 against cotton bollworm, Helicoverpa armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Appl Entomol Zool 51(1):11–20. [CrossRef]

- Sehrawat A, Sindhu SS, Glick BR (2022) Hydrogen cyanide production by soil bacteria: Biological control of pests and promotion of plant growth in sustainable agriculture. Pedosphere 32(1):15–38. [CrossRef]

- Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM (2015) BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31(19):3210–3212. [CrossRef]

- Snyder EE, Kampanya N, Lu J, Nordberg EK, Karur HR, Shukla M, Soneja J, Tian Y, Xue T, Yoo H, Zhang F, Dharmanolla C, Dongre NV, Gillespie JJ, Hamelius J, Hance M, Huntington KI, Jukneliene D, Koziski J, Mackasmiel L, Mane SP, Nguyen V, Purkayastha A, Shallom J, Yu G, Guo Y, Gabbard J, Hix D, Azad AF, Baker SC, Boyle SM, Khudyakov Y, Meng XJ, Rupprecht C, Vinje J, Crasta OR, Czar MJ, Dickerman A, Eckart JD, Kenyon R, Will R, Setubal JC, Sobral BWS (2007) PATRIC: The VBI PathoSystems Resource Integration Center. Nucleic Acids Research 35(Database):D401–D406. [CrossRef]

- Srinivas V, Naresh N, Pratyusha S, Ankati S, Govindaraj M, Gopalakrishnan S (2022) Exploring plant growth-promoting. Crop & Pasture Science 73(5):484–493. [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam G (2016) Plant growth promoting actinobacteria: a new avenue for enhancing the productivity and soil fertility of grain legumes.

- Subramaniam G, Thakur V, Saxena RK, Vadlamudi S, Purohit S, Kumar V, Rathore A, Chitikineni A, Varshney RK (2020) Complete genome sequence of sixteen plant growth promoting Streptomyces strains. Sci Rep 10(1):10294. [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam Gopalakrishnan (2011) Biocontrol of charcoal-rot of sorghum by actinomycetes isolated from herbal vermicompost. Afr J Biotechnol 10(79). [CrossRef]

- Sun M, Li L, Wang C, Wang L, Lu D, Shen D, Wang J, Jiang C, Cheng L, Pan X, Yang A, Wang Y, Zhu X, Li B, Li Y, Zhang F (2022) Naringenin confers defence against Phytophthora nicotianae through antimicrobial activity and induction of pathogen resistance in tobacco. Molecular Plant Pathology 23(12):1737–1750. [CrossRef]

- Tang J, Li Y, Zhang L, Mu J, Jiang Y, Fu H, Zhang Y, Cui H, Yu X, Ye Z (2023) Biosynthetic Pathways and Functions of Indole-3-Acetic Acid in Microorganisms. Microorganisms 11(8):2077. [CrossRef]

- Teufel F, Almagro Armenteros JJ, Johansen AR, Gíslason MH, Pihl SI, Tsirigos KD, Winther O, Brunak S, Von Heijne G, Nielsen H (2022) SignalP 6.0 predicts all five types of signal peptides using protein language models. Nat Biotechnol 40(7):1023–1025. [CrossRef]

- Tietz JI, Schwalen CJ, Patel PS, Maxson T, Blair PM, Tai H-C, Zakai UI, Mitchell DA (2017) A new genome-mining tool redefines the lasso peptide biosynthetic landscape. Nat Chem Biol 13(5):470–478. [CrossRef]

- Ueda K, Oinuma K-I, Ikeda G, Hosono K, Ohnishi Y, Horinouchi S, Beppu T (2002) AmfS, an Extracellular Peptidic Morphogen in Streptomyces griseus. J Bacteriol 184(5):1488–1492. [CrossRef]

- Vargas Hoyos HA, Santos SN, Padilla G, Melo IS (2019) Genome Sequence of Streptomyces cavourensis 1AS2a, a Rhizobacterium Isolated from the Brazilian Cerrado Biome. Microbiol Resour Announc 8(18):e00065-19. [CrossRef]

- Vijayabharathi R, Gopalakrishnan S, Sathya A, Srinivas V, Sharma M (2018a) Deciphering the tri-dimensional effect of endophytic Streptomyces sp. on chickpea for plant growth promotion, helper effect with Mesorhizobium ciceri and host-plant resistance induction against Botrytis cinerea. Microbial Pathogenesis 122:98–107. [CrossRef]

- Vijayabharathi R, Gopalakrishnan S, Sathya A, Vasanth Kumar M, Srinivas V, Mamta S (2018b) Streptomyces sp. as plant growth-promoters and host-plant resistance inducers against Botrytis cinerea in chickpea. Biocontrol Science and Technology 28(12):1140–1163. [CrossRef]

- Vijayabharathi R, Kumari BR, Sathya A, Srinivas V, Abhishek R, Sharma HC, Gopalakrishnan S (2014) Biological activity of entomopathogenic actinomycetes against lepidopteran insects (Noctuidae: Lepidoptera). Can J Plant Sci 94(4):759–769. [CrossRef]

- Vijayabharathi R, Sathya A, Gopalakrishnan S (2018c) Extracellular biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Streptomyces griseoplanus SAI-25 and its antifungal activity against Macrophomina phaseolina, the charcoal rot pathogen of sorghum. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 14:166–171. [CrossRef]

- Wang P, Liu Z, Huang Y (2018) Complete genome sequence of soil actinobacteria Streptomyces cavourensis TJ430. J Basic Microbiol 58(12):1083–1090. [CrossRef]

- Widodo WS, Billerbeck S (2023) Natural and engineered cyclodipeptides: Biosynthesis, chemical diversity, and engineering strategies for diversification and high-yield bioproduction. Engineering Microbiology 3(1):100067. [CrossRef]

- Yildiztugay E, Ozfidan-Konakci C, Kucukoduk M, Turkan I (2020) Flavonoid Naringenin Alleviates Short-Term Osmotic and Salinity Stresses Through Regulating Photosynthetic Machinery and Chloroplastic Antioxidant Metabolism in Phaseolus vulgaris. Front Plant Sci 11:682. [CrossRef]

- Zabolotneva AA, Shatova OP, Sadova AA, Shestopalov AV, Roumiantsev SA (2022) An Overview of Alkylresorcinols Biological Properties and Effects. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism 2022:1–12. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Yao T, Jiang Y, Li H, Yuan W, Li W (2021) Deciphering a Cyclodipeptide Synthase Pathway Encoding Prenylated Indole Alkaloids in Streptomyces leeuwenhoekii. Appl Environ Microbiol 87(11):e02525-20. [CrossRef]

- Zheng J, Ge Q, Yan Y, Zhang X, Huang L, Yin Y (2023) dbCAN3: automated carbohydrate-active enzyme and substrate annotation. Nucleic Acids Research 51(W1):W115–W121. [CrossRef]

- (2017) Role of Hydrolytic Enzymes of Rhizoflora in Biocontrol of Fungal Phytopathogens: An Overview. In: Rhizotrophs: Plant Growth Promotion to Bioremediation. Springer Singapore, Singapore, pp 183–203.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).