Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

29 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Regulatory Framework and Legitimacy

2.1. Regulatory Landscape and Approvals

2.2. Safety, Toxicology, and Allergenicity

3. Cost and Environmental Impact

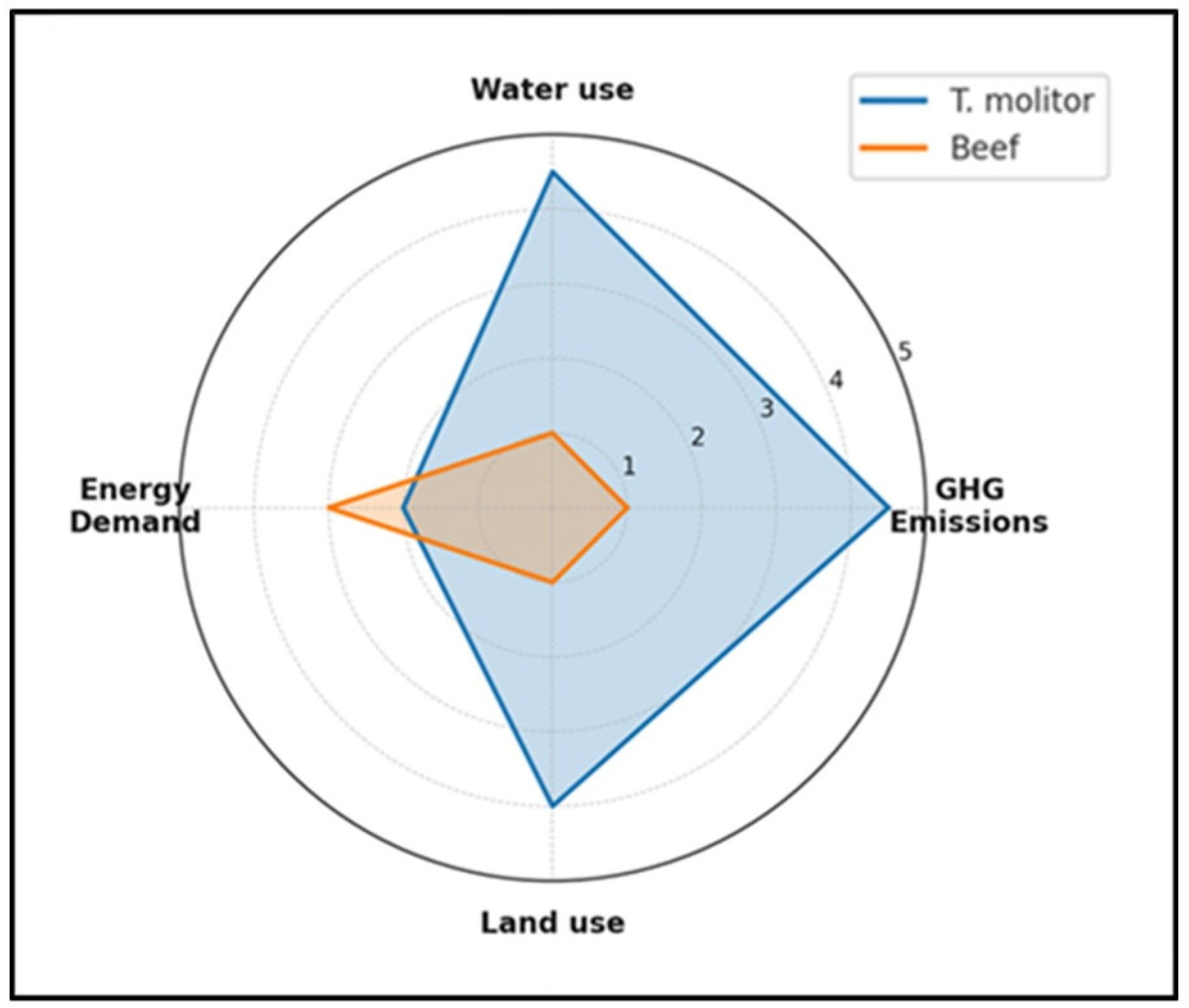

3.1. Environmental Performance and Circularity

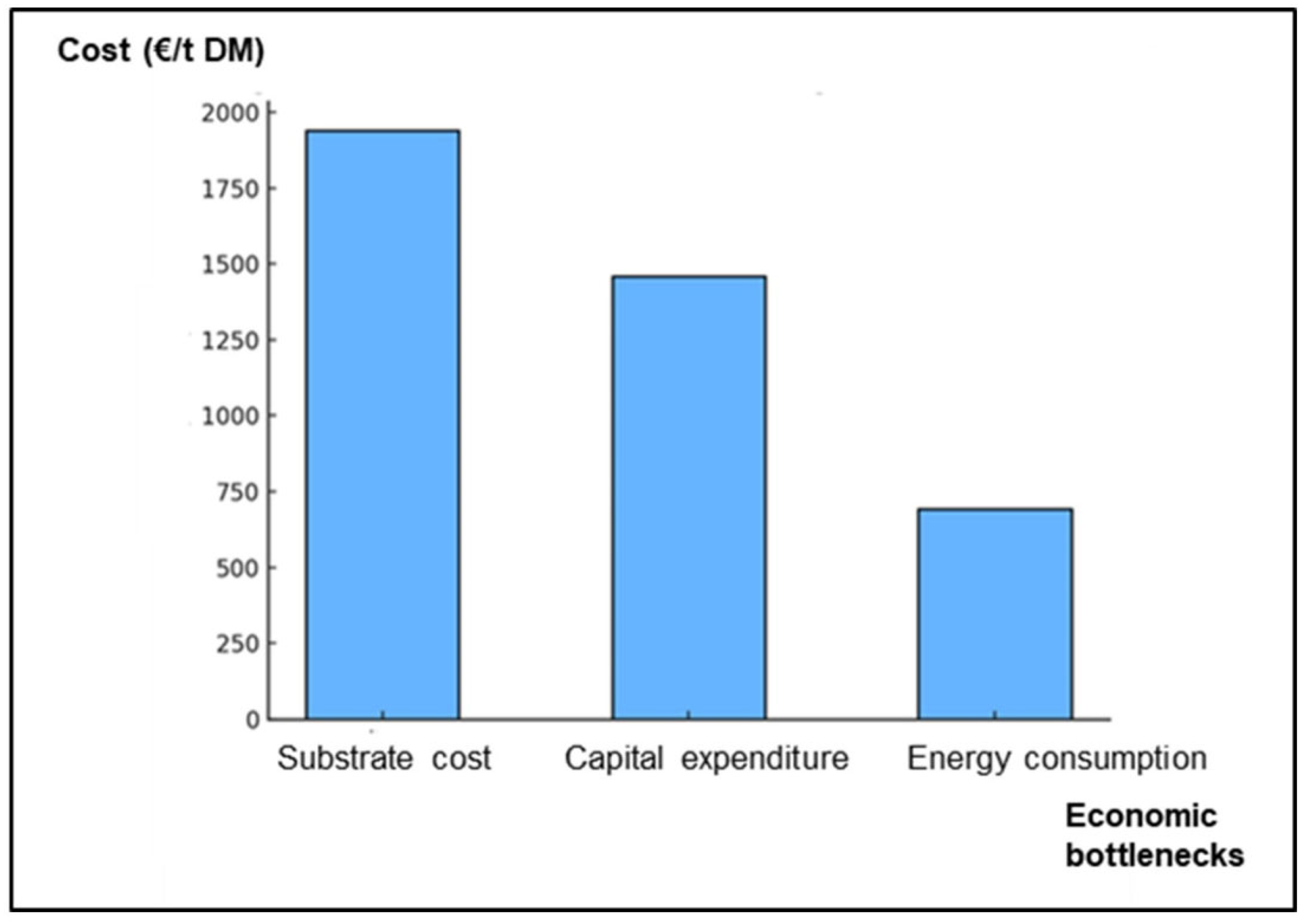

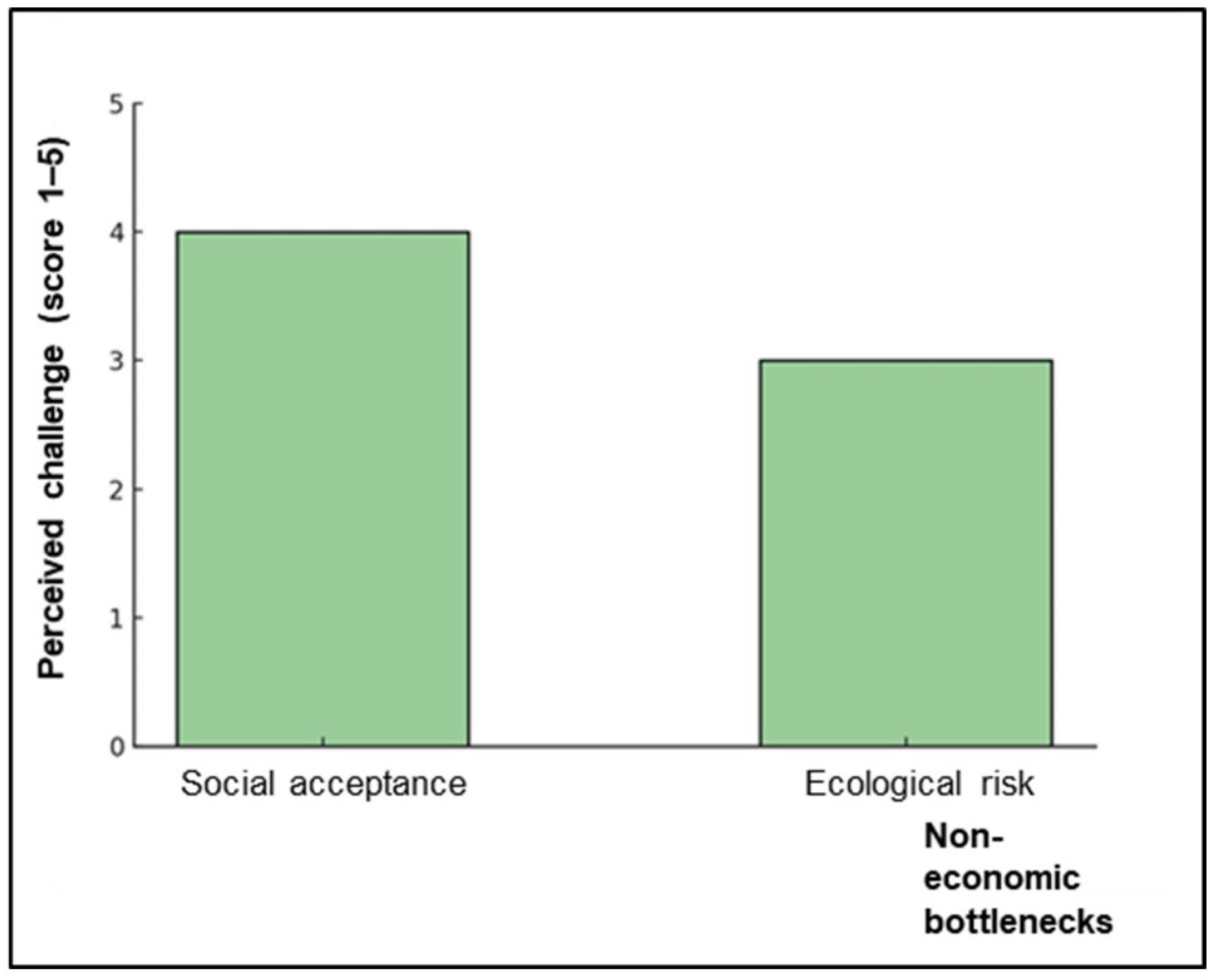

3.2. Economic Feasibility and Production Models

4. Nutritional Quality and Food Innovation Potential

5. Applications in Animal Nutrition

5.2. Other Monogastrics (Pigs, Fish)

6. Bioactive Compounds and Human Health Applications

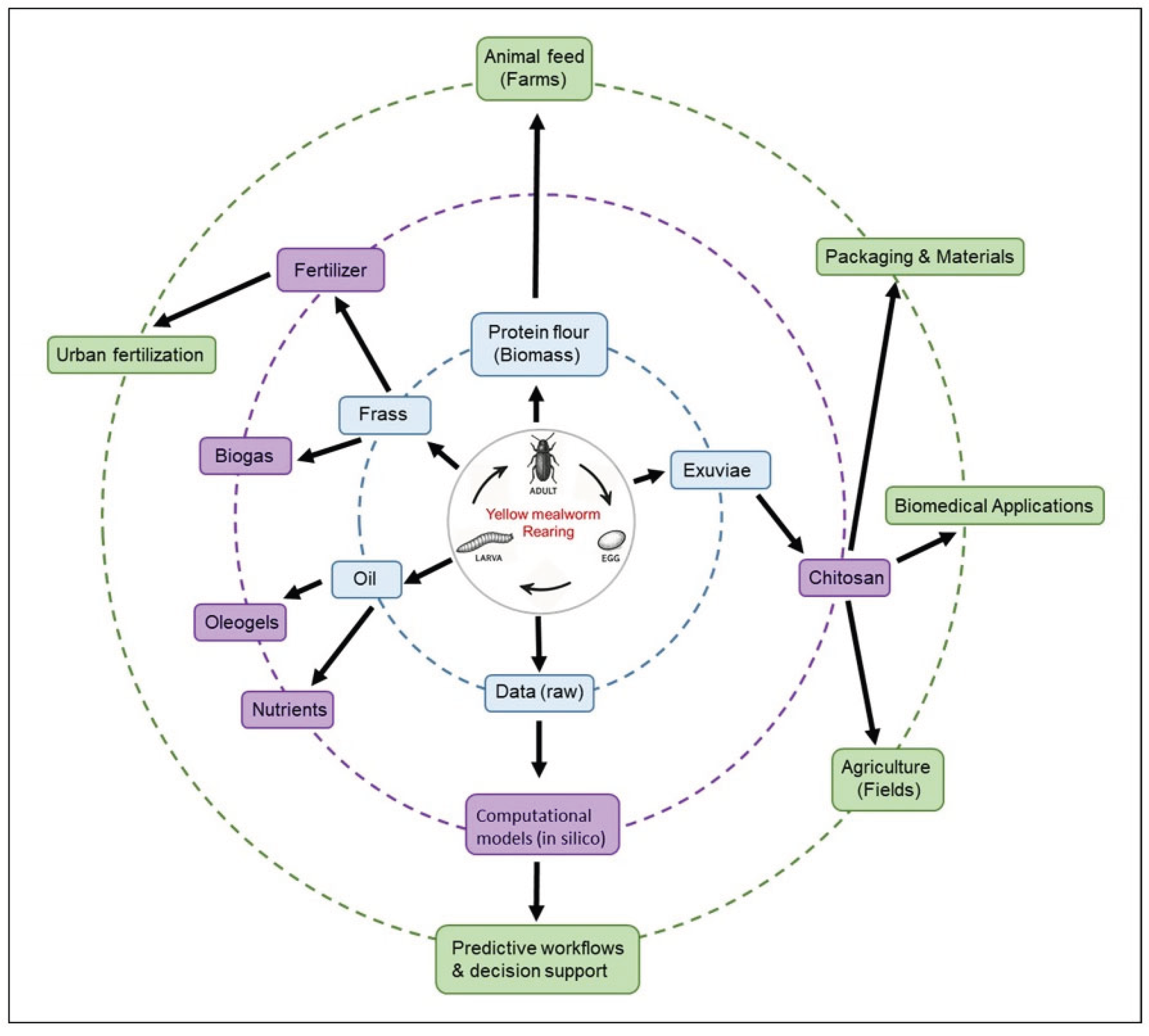

7. Low-Tech Scalability & Biorefineries

7.1. Substrate Flexibility and Local Waste Streams

7.2. Frass and Co-Product Valorisation

7.3. Systemic Integration and Biorefinery Models

8. Agroecological and Biotechnological Synergies (2020-2025): Towards a Circular Bioeconomy

8.1. Cross-Sector Innovations and Integrated Applications

8.2. Biotechnologies and Innovative Materials

8.3. Modular Biorefineries and Territorial Modeling

8.4. Challenges and Prospects for Sustainable Industrialization

8.5. Perspectives for Innovative Applications

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D. Despommier, ‘Vertical farming: a holistic approach towards food security’, Front. Sci., vol. 2, Sept. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Dreyer et al., ‘Environmental life cycle assessment of yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) production for human consumption in Austria – a comparison of mealworm and broiler as protein source’, Int. J. Life Cycle Assess., vol. 26, no. 11, pp. 2232–2247, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Khanal et al., ‘Yellow mealworms (Tenebrio molitor) as an alternative animal feed source: A comprehensive characterization of nutritional values and the larval gut microbiome’, J. Clean. Prod., vol. 389, p. 136104, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Marín-Morales, C. C. Ibarra-Herrera, and M. J. Rivas-Arreola, ‘Obtention and Characterization of Chitosan from Exuviae of Tenebrio molitor and Sphenarium purpurascens’, ACS Omega, vol. 10, no. 16, pp. 17015–17023, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Maciejewska, A. Dąbrowska, and M. Cano-Lamadrid, ‘Sustainable Protein Sources: Functional Analysis of Tenebrio molitor Hydrolysates and Attitudes of Consumers in Poland and Spain Toward Insect-Based Foods’, Foods, vol. 14, no. 2, p. 333, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Khan et al., ‘Mealworms (Tenebrio molitor L.) as a Substituent of Protein Source for Fisheries and Aquaculture: A Mini Review: Mealworms as a Substituent of Protein Source’, MARKHOR J. Zool., pp. 19–25, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Tlak Gajger and S. A. Dar, ‘Plant Allelochemicals as Sources of Insecticides’, Insects, vol. 12, no. 3, p. 189, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. S. Chewaka, C. S. Park, Y.-S. Cha, K. T. Desta, and B.-R. Park, ‘Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Tenebrio molitor (Mealworm) Using Nuruk Extract Concentrate and an Evaluation of Its Nutritional, Functional, and Sensory Properties’, Foods, vol. 12, no. 11, p. 2188, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- Montalbán, S. Martínez-Miró, A. Schiavone, J. Madrid, and F. Hernández, ‘Growth Performance, Diet Digestibility, and Chemical Composition of Mealworm (Tenebrio molitor L.) Fed Agricultural By-Products’, Insects, vol. 14, no. 10, p. 824, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Urbański et al., ‘Tachykinin-related peptides modulate immune-gene expression in the mealworm beetle Tenebrio molitor L.’, Sci. Rep., vol. 12, no. 1, p. 17277, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Majewski, P. Zapotoczny, P. Lampa, R. Burduk, and J. Reiner, ‘Multipurpose monitoring system for edible insect breeding based on machine learning’, Sci. Rep., vol. 12, no. 1, p. 7892, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Kotsou, T. Chatzimitakos, V. Athanasiadis, E. Bozinou, C. G. Athanassiou, and S. I. Lalas, ‘Innovative Applications of Tenebrio molitor Larvae in Food Product Development: A Comprehensive Review’, Foods, vol. 12, no. 23, p. 4223, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization Of United Nations, ‘FAO Korea Partnership Newsletter – 1st Quarter 2022, Issue #2’. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 2022. [Online]. Available: https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/66121641-98fb-4877-9e68-2b53b65ffa33.

- AGRINFO, ‘Latest novel food authorisations – January 2025’. COLEAD, Feb. 05, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://agrinfo.eu/book-of-reports/latest-novel-food-authorisations-january-2025/.

- N. Meijer, R. A. Safitri, W. Tao, and E. F. Hoek-Van Den Hil, ‘Review: European Union legislation and regulatory framework for edible insect production – Safety issues’, animal, p. 101468, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. Żuk-Gołaszewska, R. Gałęcki, K. Obremski, S. Smetana, S. Figiel, and J. Gołaszewski, ‘Edible Insect Farming in the Context of the EU Regulations and Marketing—An Overview’, Insects, vol. 13, no. 5, p. 446, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Malematja, T. G. Manyelo, N. A. Sebola, S. D. Kolobe, and M. Mabelebele, ‘The accumulation of heavy metals in feeder insects and their impact on animal production’, Sci. Total Environ., vol. 885, p. 163716, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Machona, M. Mutanga, F. Chidzwondo, and R. Mangoyi, ‘Sub-chronic toxicity determination of powdered Tenebrio molitor larvae as a novel food source’, Toxicol. Rep., vol. 12, pp. 111–116, June 2024. [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and Food Allergens (NDA) et al., ‘Safety of frozen and dried formulations from whole yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor larva) as a novel food pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 (EFSA 2021)’, EFSA J., vol. 19, no. 8, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Emilia et al., ‘IgE-based analysis of sensitization and cross-reactivity to yellow mealworm and edible insect allergens before their widespread dietary introduction’, Sci. Rep., vol. 15, no. 1, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. Debache, ‘Growth performance of novel food based on mixture of boiled-dried granulated Tenebrio molitor larvae and date-fruit waste in broiler chicken farming’, Asian J. Agric., vol. 5, no. 1, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Shah et al., ‘Mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) rearing and growth optimization as a sustainable food source using various larval diets under laboratory conditions’, Entomol. Exp. Appl., vol. 172, no. 9, pp. 827–836, Sept. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zunzunegui, J. Martín-García, Ó. Santamaría, and J. Poveda, ‘Analysis of yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) frass as a resource for a sustainable agriculture in the current context of insect farming industry growth’, J. Clean. Prod., vol. 460, p. 142608, July 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Oh and C. Lu, ‘Vertical farming - smart urban agriculture for enhancing resilience and sustainability in food security’, J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol., vol. 98, no. 2, pp. 133–140, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lienhard, R. Rehorska, B. Pöllinger-Zierler, C. Mayer, M. Grasser, and S. Berner, ‘Future Proteins: Sustainable Diets for Tenebrio molitor Rearing Composed of Food By-Products’, Foods, vol. 12, no. 22, p. 4092, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Mahmoud, A. O. Abotaleb, and R. A. Zinhoum, ‘Evaluation of various diets for improved growth, reproductive and nutritional value of the yellow mealworm, Tenebrio molitor L.’, Sci. Rep., vol. 15, no. 1, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sowmya, M. Anand, C. Indu Rani, G. Amuthaselvi, and P. Janaki, ‘Recent developments and inventive approaches in vertical farming’, Front. Sustain. Food Syst., vol. 8, Sept. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. H. Niyonsaba, I. L. Groeneveld, I. Vermeij, J. Höhler, H. J. Van Der Fels-Klerx, and M. P. M. Meuwissen, ‘Profitability of insect production for T. molitor farms in The Netherlands’, J. Insects Food Feed, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 895–902, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. H. Niyonsaba, J. Höhler, J. Kooistra, H. J. Van Der Fels-Klerx, and M. P. M. Meuwissen, ‘Profitability of insect farms’, J. Insects Food Feed, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 923–934, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Truzzi et al., ‘Influence of Feeding Substrates on the Presence of Toxic Metals (Cd, Pb, Ni, As, Hg) in Larvae of Tenebrio molitor: Risk Assessment for Human Consumption’, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health, vol. 16, no. 23, p. 4815, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Noyens, F. Schoeters, M. Van Peer, S. Berrens, S. Goossens, and S. Van Miert, ‘The nutritional profile, mineral content and heavy metal uptake of yellow mealworm reared with supplementation of agricultural sidestreams’, Sci. Rep., vol. 13, no. 1, p. 11604, July 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Aguilar-Toalá, A. M. Vidal-Limón, and A. M. Liceaga, ‘Advancing Food Security with Farmed Edible Insects: Economic, Social, and Environmental Aspects’, Insects, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 67, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kotsou, T. Chatzimitakos, V. Athanasiadis, E. Bozinou, and S. I. Lalas, ‘Exploiting Agri-Food Waste as Feed for Tenebrio molitor Larvae Rearing: A Review’, Foods, vol. 13, no. 7, p. 1027, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. K. Dalmoro, C. H. Franceschi, and C. Stefanello, ‘A Systematic Review and Metanalysis on the Use of Hermetia illucens and Tenebrio molitor in Diets for Poultry’, Vet. Sci., vol. 10, no. 12, p. 702, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Pöllinger-Zierler et al., ‘Tenebrio molitor (Linnaeus, 1758): Microbiological Screening of Feed for a Safe Food Choice’, Foods, vol. 12, no. 11, p. 2139, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- Verni et al., ‘Optimizing Tenebrio molitor powder as ingredient in breadmaking: Impact of enzymatic hydrolysis on dough techno-functional properties and bread quality’, Future Foods, vol. 11, p. 100665, June 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kröncke, S. Wittke, N. Steinmann, and R. Benning, ‘Analysis of the Composition of Different Instars of Tenebrio molitor Larvae using Near-Infrared Reflectance Spectroscopy for Prediction of Amino and Fatty Acid Content’, Insects, vol. 14, no. 4, p. 310, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Yoon and C. Kong, ‘Determination of ileal digestibility of tryptophan in tryptophan biomass for broilers using the direct and regression methods’, Anim. Feed Sci. Technol., vol. 304, p. 115732, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Moutinho, A. Oliva-Teles, S. Martínez-Llorens, Ó. Monroig, and H. Peres, ‘Total fishmeal replacement by defattedHermetia illucens larvae meal in diets for gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) juveniles’, J. Insects Food Feed, vol. 8, no. 12, pp. 1455–1468, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Jiang et al., ‘Effects of yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) larvae meal on the growth performance, serum biochemical parameters and caecal metabolome in broiler chickens’, Ital. J. Anim. Sci., vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 813–823, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Vasilopoulos et al., ‘Growth performance, welfare traits and meat characteristics of broilers fed diets partly replaced with whole Tenebrio molitor larvae’, Anim. Nutr., vol. 13, pp. 90–100, June 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. López-Gámez, R. Del Pino-García, M. A. López-Bascón, and V. Verardo, ‘Improving Tenebrio molitor Growth and Nutritional Value through Vegetable Waste Supplementation’, Foods, vol. 13, no. 4, p. 594, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Petkov et al., ‘Low-Fat Tenebrio molitor Meal as a Component in the Broiler Diet: Growth Performance and Carcass Composition’, Insects, vol. 15, no. 12, p. 979, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Nieto, J. Plaza, J. Lara, J.-A. Abecia, I. Revilla, and C. Palacios, ‘Performance of Slow-Growing Chickens Fed with Tenebrio molitor Larval Meal as a Full Replacement for Soybean Meal’, Vet. Sci., vol. 9, no. 3, p. 131, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Biasato et al., ‘Can a mixture of Hermetia illucens and Tenebrio molitor meals be feasible to feed broiler chickens? A focus on bird productive performance, nutrient digestibility, and meat quality’, Poult. Sci., vol. 104, no. 7, p. 105150, July 2025. [CrossRef]

- L. Hammer et al., ‘Mealworm larvae (Tenebrio molitor) and crickets (Acheta domesticus) show high total protein in vitro digestibility and can provide good-to-excellent protein quality as determined by in vitro DIAAS’, Front. Nutr., vol. 10, p. 1150581, July 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Gonzalez-de La Rosa, S. Montserrat-de La Paz, and F. Rivero-Pino, ‘Production, characterisation, and biological properties of Tenebrio molitor-derived oligopeptides’, Food Chem., vol. 450, p. 139400, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Ma, J. Yang, H. Suo, and J. Song, ‘Tenebrio molitor proteins and peptides: Cutting-edge insights into bioactivity and expanded food applications’, Food Biosci., vol. 68, p. 106369, June 2025. [CrossRef]

- P. Stephan, J. E. D. S. Sarkis, J. S. D. Rosa, and M. L. Cocato, ‘Tenebrio Molitor: Investigating the Scientific Foundations and Proteomic and Peptidomic Potential’, Food Nutr. Sci., vol. 16, no. 04, pp. 427–435, 2025. [CrossRef]

- T. Perez, F. Casanova, L. S. Queiroz, H. O. Petersen, P. J. García-Moreno, and A. H. Feyissa, ‘Protein extraction from yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) assisted by pulsed electric fields: Effect on foaming properties’, LWT, vol. 213, p. 117041, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. V. Villanova et al., ‘Bioactive peptides from Tenebrio molitor: physicochemical and antioxidant properties and antimicrobial capacity’, An. Acad. Bras. Cienc., vol. 96, no. suppl 1, p. e20231375, 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. F. Ferrazzano, F. D’Ambrosio, S. Caruso, R. Gatto, and S. Caruso, ‘Bioactive Peptides Derived from Edible Insects: Effects on Human Health and Possible Applications in Dentistry’, Nutrients, vol. 15, no. 21, p. 4611, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Tan et al., ‘Tenebrio molitor Proteins-Derived DPP-4 Inhibitory Peptides: Preparation, Identification, and Molecular Binding Mechanism’, Foods, vol. 11, no. 22, p. 3626, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Dávalos Terán, K. Imai, I. M. E. Lacroix, V. Fogliano, and C. C. Udenigwe, ‘Bioinformatics of edible yellow mealworm ( Tenebrio molitor ) proteome reveal the cuticular proteins as promising precursors of dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitors’, J. Food Biochem., vol. 44, no. 2, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Gonzalez-de La Rosa, E. Marquez-Paradas, M. J. Leon, S. Montserrat-de La Paz, and F. Rivero-Pino, ‘Exploring Tenebrio molitor as a source of low-molecular-weight antimicrobial peptides using a n in silico approach: correlation of molecular features and molecular docking’, J. Sci. Food Agric., vol. 105, no. 3, pp. 1711–1736, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. Yin et al., ‘Isolation, identification and in silico analysis of two novel cytoprotective peptides from tilapia skin against oxidative stress-induced ovarian granulosa cell damage’, J. Funct. Foods, vol. 107, p. 105629, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Morena, C. Cencini, E. Calzoni, S. Martino, and C. Emiliani, ‘A Novel Workflow for In Silico Prediction of Bioactive Peptides: An Exploration of Solanum lycopersicum By-Products’, Biomolecules, vol. 14, no. 8, p. 930, July 2024. [CrossRef]

- Brai et al., ‘Proteins from Tenebrio molitor: An interesting functional ingredient and a source of ACE inhibitory peptides’, Food Chem., vol. 393, p. 133409, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Pessina et al., ‘Antihypertensive, cardio- and neuro-protective effects of Tenebrio molitor (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) defatted larvae in spontaneously hypertensive rats’, PLOS ONE, vol. 15, no. 5, p. e0233788, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- Berraquero-García, L. Martínez-Sánchez, E. M. Guadix, and P. J. García-Moreno, ‘Encapsulation of Tenebrio molitor Hydrolysate with DPP-IV Inhibitory Activity by Electrospraying and Spray-Drying’, Nanomaterials, vol. 14, no. 10, p. 840, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- H.-S. Jo, D.-B. Song, S.-H. Lee, K.-S. Lee, J. Yang, and S.-M. Hong, ‘Concurrent Hydrolysis–Fermentation of Tenebrio molitor Protein by Lactobacillus plantarum KCCM13068P Attenuates Inflammation in RAW 264.7 Macrophages and Constipation in Loperamide-Induced Mice’, Foods, vol. 14, no. 11, p. 1886, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Tran, H. Lee, M.-G. Ji, L. Ngo Hoang, and S.-J. Lee, ‘The synergistic extract of Zophobas atratus and Tenebrio molitor regulates neuroplasticity and oxidative stress in a scopolamine-induced cognitive impairment model’, Front. Aging Neurosci., vol. 17, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. I. Torres-Acosta et al., ‘Insects with Phenolics and Antioxidant Activities to Supplement Mezcal: Tenebrio molitor L.1 and Schistocerca piceifrons Walker2’, Southwest. Entomol., vol. 46, no. 3, Sept. 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. N. Ngoc, J.-Y. Moon, and Y.-C. Lee, ‘Insights into Bioactive Peptides in Cosmetics’, Cosmetics, vol. 10, no. 4, p. 111, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Fan, N. E. Wedamulla, Y.-J. Choi, Q. Zhang, S. M. Bae, and E.-K. Kim, ‘Tenebrio molitor Larva Trypsin Hydrolysate Ameliorates Atopic Dermatitis in C57BL/6 Mice by Targeting the TLR-Mediated MyD88-Dependent MAPK Signaling Pathway’, Nutrients, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 93, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Verheyen, F. Meersman, I. Noyens, S. Goossens, and S. Van Miert, ‘The Application of Mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) Oil in Cosmetic Formulations’, Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol., vol. 125, no. 3, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Vrontaki, C. Adamaki-Sotiraki, C. I. Rumbos, A. Anastasiadis, and C. G. Athanassiou, ‘Valorization of local agricultural by-products as nutritional substrates for Tenebrio molitor larvae: A sustainable approach to alternative protein production’, Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., vol. 31, no. 24, pp. 35760–35768, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Fondevila, A. Remiro, and M. Fondevila, ‘Growth performance and chemical composition of tenebrio molitor larvae grown on substrates with different starch to fibre ratios’, Ital. J. Anim. Sci., vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 887–894, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Yakti et al., ‘Utilising common bean and strawberry vegetative wastes in yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) substrates: effects of pre-treatment on growth and composition’, Sci. Rep., vol. 15, no. 1, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Verardi et al., ‘Tenebrio molitor Frass: A Cutting-Edge Biofertilizer for Sustainable Agriculture and Advanced Adsorbent Precursor for Environmental Remediation’, Agronomy, vol. 15, no. 3, p. 758, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- G. Lopes et al., ‘BugBook: Critical considerations for evaluating and applying insect frass’, J. Insects Food Feed, pp. 1–28, June 2025. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Seijas, H. Fernandes, D. Outeiriño, M. G. Morán-Aguilar, J. M. Domínguez, and J. M. Salgado, ‘Potential use of frass from edible insect Tenebrio molitor for proteases production by solid-state fermentation’, Food Bioprod. Process., vol. 144, pp. 146–155, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Magro, D. Lovarelli, J. Bacenetti, and M. Guarino, ‘The potential of insect frass for sustainable biogas and biomethane production: A review’, Bioresour. Technol., vol. 412, p. 131384, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. He et al., ‘Fabrication and environmental assessment of photo-assisted Fenton-like Fe/FBC catalyst utilizing mealworm frass waste’, J. Clean. Prod., vol. 256, p. 120259, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Muñoz-Seijas, H. Fernandes, J. M. Domínguez, and J. M. Salgado, ‘Recent Advances in Biorefinery of Tenebrio molitor Adopting Green Technologies’, Food Bioprocess Technol., vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 1061–1078, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Moruzzo, F. Riccioli, S. Espinosa Diaz, C. Secci, G. Poli, and S. Mancini, ‘Mealworm (Tenebrio molitor): Potential and Challenges to Promote Circular Economy’, Animals, vol. 11, no. 9, p. 2568, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Maria Vodenicharova, ‘Supply Chain Challenges of Insect Protein’, Nanotechnol. Percept., vol. 20, no. S11 (Special Issue), pp. 1570–1582, 2024.

- M. Azzi, S. Elkadaoui, J. Zim, J. Desbrieres, Y. El Hachimi, and A. Tolaimate, ‘Tenebrio Molitor breeding rejects as a high source of pure chitin and chitosan: Role of the processes, influence of the life cycle stages and comparison with Hermetia illucens’, Int. J. Biol. Macromol., vol. 277, p. 134475, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Terkula Iber, N. Azman Kasan, D. Torsabo, and J. Wese Omuwa, ‘A Review of Various Sources of Chitin and Chitosan in Nature’, J. Renew. Mater., vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 1097–1123, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Izadi, H. Asadi, and M. Bemani, ‘Chitin: a comparison between its main sources’, Front. Mater., vol. 12, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Nafary, S. A. Mousavi Nezhad, and S. Jalili, ‘Extraction and Characterization of Chitin and Chitosan from Tenebrio Molitor Beetles and Investigation of Its Antibacterial Effect Against Pseudomonas aeruginosa’, Adv. Biomed. Res., vol. 12, no. 1, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Martínez-Pineda et al., ‘Exploring the Potential of Yellow Mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) Oil as a Nutraceutical Ingredient’, Foods, vol. 13, no. 23, p. 3867, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kim and I. Oh, ‘The Characteristic of Insect Oil for a Potential Component of Oleogel and Its Application as a Solid Fat Replacer in Cookies’, Gels, vol. 8, no. 6, p. 355, June 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Jeong and I. Oh, ‘Characterization of mixed-component oleogels: Beeswax and glycerol monostearate interactions towards Tenebrio Molitor larvae oil’, Curr. Res. Food Sci., vol. 8, p. 100689, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Brai et al., ‘Upcycling Milk Industry Byproducts into Tenebrio molitor Larvae: Investigation on Fat, Protein, and Sugar Composition’, Foods, vol. 13, no. 21, p. 3450, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Mamtimin et al., ‘Gut microbiome of mealworms (Tenebrio molitor Larvae) show similar responses to polystyrene and corn straw diets’, Microbiome, vol. 11, no. 1, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang et al., ‘Enhancing Plastic Decomposition in Mealworms (Tenebrio molitor): The Role of Nutritional Amino Acids and Water’, Adv. Energy Sustain. Res., vol. 6, no. 6, June 2025. [CrossRef]

- T. Mamtimin et al., ‘Novel Feruloyl Esterase for the Degradation of Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Screened from the Gut Microbiome of Plastic-Degrading Mealworms (Tenebrio Molitor Larvae)’, Environ. Sci. Technol., vol. 58, no. 40, pp. 17717–17731, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Janković-Tomanić, B. Petković, J. S. Vranković, and V. Perić-Mataruga, ‘Effects of high doses of zearalenone on some antioxidant enzymes and locomotion of Tenebrio molitor larvae (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae)’, J. Insect Sci., vol. 24, no. 3, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Chamani et al., ‘From Digestion to Detoxification: Exploring Plant Metabolite Impacts on Insect Enzyme Systems for Enhanced Pest Control’, Insects, vol. 16, no. 4, p. 392, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Winkiel, S. Chowański, K. Walkowiak-Nowicka, M. Gołębiowski, and M. Słocińska, ‘A tomato a day keeps the beetle away – the impact of Solanaceae glycoalkaloids on energy management in the mealworm Tenebrio molitor’, Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., vol. 31, no. 48, pp. 58581–58598, Sept. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Winkiel, S. Chowański, M. Gołębiowski, S. A. Bufo, and M. Słocińska, ‘Solanaceae Glycoalkaloids Disturb Lipid Metabolism in the Tenebrio molitor Beetle’, Metabolites, vol. 13, no. 12, p. 1179, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Walkowiak-Nowicka, J. Mirek, S. Chowański, R. Sobkowiak, and M. Słocińska, ‘Plant secondary metabolites as potential bioinsecticides? Study of the effects of plant-derived volatile organic compounds on the reproduction and behaviour of the pest beetle Tenebrio molitor’, Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf., vol. 257, p. 114951, June 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Mwita et al., ‘Chitosan Extracted from the Biomass of Tenebrio molitor Larvae as a Sustainable Packaging Film’, Materials, vol. 17, no. 15, p. 3670, July 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Liu et al., ‘Preparation of chitosan/Tenebrio molitor larvae protein/curcumin active packaging film and its application in blueberry preservation’, Int. J. Biol. Macromol., vol. 275, p. 133675, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Benashvili et al., ‘Effect of mealworm (Tenebrio molitor L.) chitosan coating on the postharvest qualities of strawberries’, Postharvest Biol. Technol., vol. 228, p. 113657, Oct. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ilijin et al., ‘The impact of co-fed plastic diet on Tenebrio molitor gut bacterial community structure’, Sci. Rep., vol. 15, no. 1, July 2025. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang and T. Tang, ‘Effects of Polystyrene Diet on the Growth and Development of Tenebrio molitor’, Toxics, vol. 10, no. 10, p. 608, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Morganti, G. Morganti, and M.-B. Coltelli, ‘Natural Polymers and Cosmeceuticals for a Healthy and Circular Life: The Examples of Chitin, Chitosan, and Lignin’, Cosmetics, vol. 10, no. 2, p. 42, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mersmann, V. G. L. Souza, and A. L. Fernando, ‘Green Processes for Chitin and Chitosan Production from Insects: Current State, Challenges, and Opportunities’, Polymers, vol. 17, no. 9, p. 1185, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Leipertz, H. Hogeveen, and H. W. Saatkamp, ‘Economic supply chain modelling of industrial insect production in the Netherlands’, J. Insects Food Feed, vol. 10, no. 8, pp. 1361–1385, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Vinci, S. A. Prencipe, L. Masiello, and M. G. Zaki, ‘The Application of Life Cycle Assessment to Evaluate the Environmental Impacts of Edible Insects as a Protein Source’, Earth, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 925–938, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Modahl and A. Brekke, ‘Environmental performance of insect protein: a case of LCA results for fish feed produced in Norway’, SN Appl. Sci., vol. 4, no. 6, June 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Villaró-Cos, J. L. Guzmán Sánchez, G. Acién, and T. Lafarga, ‘Research trends and current requirements and challenges in the industrial production of spirulina as a food source’, Trends Food Sci. Technol., vol. 143, p. 104280, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and Food Allergens (NDA) et al., ‘Safety of frozen and dried forms of whole yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor larva) as a novel food pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 (EFSA 2025)’, EFSA J., vol. 23, no. 1, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Malila et al., ‘Current challenges of alternative proteins as future foods’, Npj Sci. Food, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 53, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Foughar, M. Arrobas, and M. Â. Rodrigues, ‘Mealworm Larvae Frass Exhibits a Plant Biostimulant Effect on Lettuce, Boosting Productivity beyond Just Nutrient Release or Improved Soil Properties’, Horticulturae, vol. 10, no. 7, p. 711, July 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Ninkuu et al., ‘Phenylpropanoids metabolism: recent insight into stress tolerance and plant development cues’, Front. Plant Sci., vol. 16, June 2025. [CrossRef]

- Z. Abro et al., ‘Global review of consumer preferences and willingness to pay for edible insects and derived products’, Glob. Food Secur., vol. 44, p. 100834, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- C. Biteau, T. Bry-Chevalier, D. Crummett, R. Ryba, and M. St. Jules, ‘Beyond the buzz: insect-based foods are unlikely to significantly reduce meat consumption’, Npj Sustain. Agric., vol. 3, no. 1, p. 35, June 2025. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Small-Scale/Low-Tech | Industrial/Large-Scale | Key Implications |

| Substrate | Local by-products (high variability) [30,31] | Standardized diets (consistent nutrients) [31] | Small farms adapt to waste but face contamination risks. |

| Energy Use | 15–20 kWh/kg (passive systems)[25] | 25–30 kWh/kg (HVAC + automation)[26] | Industrial cuts labor costs but increases energy demand. |

| Labor | 8–12 hrs/kg (manual processes)[26] | 1–2 hrs/kg (automated)[26] | Critical for ROI in high-wage regions [26]. |

| Frass Quality | Variable NPK; occasional As exceedance [30] | Uniform NPK; EFSA-compliant [30] | Small-scale requires blending (e.g., rice hulls [31]). |

| Circularity | High (local waste recycling)[25] | Moderate (logistics constraints) [28] | Policy incentives (e.g., EU tax breaks) could boost industrial circularity. |

| Bioactive Compound | Health Effect | Reference |

| Cryptides (2–20 AA) | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory | [47] |

| YAN | Antihypertensive | [52,58] |

| Hydrophobic fractions | Cardiovascular protection | [12] |

| LPDQWDWR, APPDGGFWEWGD | Type 2 diabetes | [53] |

| VVYPWTQ, AWYGANK, LWDHKV | Antihypertensive | (32) |

| Defatted extract | Cardioprotective, anti-inflammatory | [59] |

| DPP-IV inhibitors | Type 2 diabetes | [60] |

| Glycosides & heterocycles | Neuroprotective | [62] |

| Alcalase hydrolysates (standardized process) | Antioxidant; antimicrobial vs. S. aureus, E. coli | [51] |

| Protein hydrolysates (time-resolved) | Increasing antioxidant capacity during hydrolysis | [5] |

| Fermented hydrolysates (L. plantarum) | Anti-inflammatory; improved GI motility (mouse) | [61] |

| Phenolic compounds (methanolic extracts) | Antioxidant (DPPH, FRAP) | [63] |

| Dermocosmetic peptides (review) | Anti-ageing, moisturizing, soothing (skin) | [64] |

| Trypsin hydrolysates (in vivo, dermatitis) | Atopic dermatitis amelioration (TLR-MyD88-MAPK) | [65] |

| T. molitor oil (keratinocytes) | Moisturizing; cytoprotective for skin repair | [66] |

| Application Domain | Valorized Form of T. molitor | Function / Benefit | References |

| Medical / Biomaterials | Chitin nanofibrils | Skin regeneration, tissue engineering | [4,99,100,102] |

| Agriculture | Frass, chitosan | Organic fertilizer, soil enhancer, crop protection | [5,12,23,24,25,34,42,67,107,108] |

| Animal Nutrition | Meal, peptides | Alternative protein source, gut health, immune modulation | [9,19,39,40,42,43,45] |

| Green Biotechnologies | Chitosan | Biodegradable antimicrobial films | [34,94,95,96] |

| Food Technology | Oil, oleogels | Fat replacement, nutrient-rich oil | [37,82,83,84] |

| Industrial Processes | Whole larvae, oils, meal | Sensor-based monitoring, scalability, optimization | [28,37,75,101,103,104] |

| Bioinformatics & Predictive Workflows (Transversal) | Proteome mining, in silico modeling | Bioactive-peptide prediction; by-product upcycling; computational workflows | [54,56,57] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).