1. Introduction

The edible insect sector is experiencing rapid growth due to its scalability, sustainability, and the increasing recognition of its potential to transform the global feed chain. Edible insects are rich in protein, fats, and micronutrients, and they are a viable alternative to conventional meat sources. Insect production requires significantly fewer resources, such as land and water, and has a lower environmental impact in terms of greenhouse gas emissions [

1,

2]. The European Union’s (EU) Novel Food Regulation (EU 2015/2283) has established a legal framework for supporting the commercial development of the edible insect industry. This regulation ensures that insects introduced onto the EU feed market meet stringent safety standards [

3]. Several insect species have already been approved for human consumption, including crickets (

Acheta domesticus), mealworms (

Tenebrio molitor), and grasshoppers (

Locusta migratoria) [

4]. This legal endorsement has enabled the expansion of insect farming across Europe, leading to increased research and development projects to scale up production [

5]. Despite regulatory progress, challenges remain, particularly with regard to consumer acceptance and the establishment of robust supply chains [

6]. Nevertheless, the edible insect sector continues to flourish, and it could play a pivotal role in addressing global food and feed security issues in the coming decades [

7].

Edible insects also hold promise in animal nutrition, particularly in the production of feed for companion animals such as dogs and cats. Insects such as black soldier fly larvae (

Hermetia illucens), crickets, and mealworms have been found to provide a high-protein, nutrient-dense alternative to conventional animal feeds [

8,

9]. Insects contain essential amino acids, fatty acids, and minerals that are critical for the health of companion animals [

10]. Studies indicate that the nutritional value of insect-based pet food could be comparable to that of traditional protein sources such as chicken or beef, while being more sustainable due to lower resource use and lower emissions in the production process [

11]. The use of insects in pet food is still in its infancy, particularly on Western markets, where consumers may be hesitant to accept these novel protein sources [

12]. However, the environmental benefits and the nutritional adequacy of insect-based pet food have prompted companies to explore this market, leading to the development of dog and cat foods incorporating insect meal [

13]. As awareness grows and regulatory frameworks adapt, the use of edible insects in companion animal nutrition is expected to increase, potentially transforming the pet feed industry [

14].

Tenebrio molitor is increasingly explored as a sustainable alternative protein source of pet food with an optimal nutritional profile. Mealworms are rich in high-quality protein, fat, and essential amino acids, which are crucial for the healthy growth of companion animals such as dogs and cats [

15]. In terms of macronutrient levels, mealworms typically contain around 50% protein and 30% fat on a dry matter basis, and they are a rich source of fiber, which makes them an attractive feed ingredient [

16].

Tenebrio molitor also contains essential vitamins (including vitamin B12) and minerals such as calcium, zinc, and iron, which contribute to its overall nutritional value [

17]. However, as a feed component, insect meal does not fully meet the amino acid requirements of pets. Insect meal offers a more environmentally-friendly alternative to traditional protein sources such as beef or chicken, and research indicates that mealworms have a much smaller environmental footprint and require less water, land, and feed than conventional livestock [

18]. Pet food producers could start to incorporate

T. molitor meal into their current formulations as a key ingredient, thus providing nutritional balance and supporting sustainability in the pet food industry [

19].

The use of

T. molitor meal in animal feed is gaining traction, but its full potential has not been fully explored, especially as regards the final nutritional outcomes for animals and the scalability of its integration. Mealworm meal is abundant in protein, essential fatty acids, and micronutrients, and it is a viable alternative to traditional protein sources such as fish meal and soy [

20]. In addition, the use of soy in large-scale production can be problematic due to its high content of antinutritional factors. However, meal processing methods can affect the bioavailability of nutrients, potentially impacting the digestibility and nutritional efficacy of the final feed product [

21]. For example, drying and defatting may lead to nutrient loss or alter meal structure, thus affecting its performance in animal diets [

22]. Moreover,

T. molitor meal provides essential proteins and lipids, but it may be deficient in certain nutrients such as specific amino acids or vitamins, which implies that it has to be combined with other feed ingredients to fully meet the dietary needs of animals [

23].

The impact of

T. molitor meal on the final product also depends on its interactions with other feed ingredients. Research has shown that

T. molitor meal can be combined with plant-based and animal-based protein sources, such as soy and fish meal, respectively, to enhance the nutritional value of feed and create feeds that better meet the dietary needs of companion animals [

24]. However, these combinations must be carefully formulated, as excessive reliance on a single ingredient can lead to nutrient imbalances or impact the feed’s palatability [

19]. Attempts are being made to determine the optimal inclusion rates of mealworm meal in feeds to maximize its benefits without compromising the overall quality of the diet [

18]. The scalability of

T. molitor farming and processing technologies also pose a challenge. Factors such as the availability of feedstock for mealworm rearing, cost-effective processing methods, and the environmental impact of large-scale production are being examined [

25].

To address these knowledge gaps, further research is needed to investigate the long-term effects of mealworm-based diets on various animal species and their implications for animal growth, health, and productivity. In addition, there is evidence to indicate that agricultural by-products such as broccoli stems or distillers’ grains can be used in mealworm rearing to promote sustainability and reduce production costs. However, the impact of these substrates on the nutritional quality of mealworm meal and the final feed product remains an area of exploration [

26]. As the industry moves toward more sustainable feed solutions, the role of mealworm meal will likely increase, provided that technological and nutritional challenges are addressed through continued research and innovation [

23,

27].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the nutritional value of five dog food formulas with different inclusion levels of T. molitor meal (25%, 30%, 35%, 40%, and 45%). In addition, attempts were also made to assess the effect of varying dietary levels of mealworm meal on selected physical parameters of the formulas that influence their functionality in dogs’ diets.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Feed Production

Five feed formulas were developed and validated in the study. Their applicability for the production of hypoallergenic feed for dogs with food-responsive enteropathies was assessed. The formulas were characterized by varying inclusion levels of

T. molitor meal at 25%, 30%, 35%, 40%, and 45% on a dry matter basis. Live mealworm larvae were sourced from a Polish insect farm observing HACCP feed safety requirements and national veterinary regulations concerning feed safety, animal health, disease control, animal welfare, and feed hygiene. To ensure the nutritional consistency of the purchased insects, larvae were sourced from the same supplier during the entire project. Insects were transported and stored in line with ethical standards and IPIFF guidelines on insect welfare [

28]. Before processing, insects were fasted for 72 hours to clear the digestive tract. Mechanical cleaning methods were applied to remove feed residues, exuviae (molted skins), dead larvae, and pupating individuals. Insects were euthanized by thermal methods according to the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) guidelines for the euthanasia of animals [

29]. Standardized insect meal was produced using a comprehensive industrial line for killing and processing insects.

The nutritional composition of feed was designed to meet the following target parameters: crude protein content – approximately 28% (±2.5%), crude fat content – approximately 15% (±1.5%), crude ash content – approximately 5% (±2.5%), and crude fiber content – approximately 5% (±2.5%). Depending on the formula, T. molitor meal was partially substituted with thermally processed potato by-products and fish oil to achieve these targets. The proportions of the remaining feed ingredients were identical in all feeds and consistent with those used in commercial hypoallergenic feeds. A 50 kg batch of each feed formula was produced and tested. The details of some technological processes constitute the subcontractor’s intellectual property. According to the provided information, the production process involved feed extrusion methods that are commonly applied in the pet food industry. The feed production system relied on EN ISO 9001 and HACCP quality management standards. The feed was produced in a dry form as oval granules with a diameter of 15 mm.

2.2. Nutritional Value Assessment

A primary sample of 0.5 kg was collected from each batch of feed using a sampling probe for nutritional analysis. Each primary sample was then divided into five laboratory samples (n = 25 for each formula). Before analysis, laboratory samples were ground and homogenized using a laboratory mill. To determine dry matter content, samples were dried at 105 °C to constant weight. The proximate chemical composition (total protein, crude fat, crude fiber, total ash, and total carbohydrates) of each laboratory sample was determined according to the standard methods recommended by AOAC [

29]. Specifically, crude fat content was determined by the Soxhlet extraction method with diethyl ether as the solvent (PN-ISO 6492:2005). Total ash content was determined by incineration in a muffle furnace at 580 °C for 8 hours (PN-ISO 2171:1994). Total protein (N × 6.25) was determined by the Kjeldahl method (PN-EN ISO 5983-1:2005). Crude fiber content was determined according to PN-EN ISO 6865:2002. Total carbohydrate content was calculated using the following formula: total carbohydrates (%) = 100% – [moisture% + total protein% + crude fat% + crude fiber% + total ash%].

2.3. Fatty Acid Profile

To determine the fatty acid profile of the formulas, lipids were extracted from the samples using the Folch procedure. Approximately 5 g of each sample was combined with 40 mL of a chloroform:methanol (2:1, v/v) mixture. The extract was filtered into a 100 mL flask, transferred to a glass tube, and evaporated at 60 °C under a nitrogen stream. The extracted lipids were stored overnight in a refrigerator. Next, the lipid residue was dissolved in 10 mL of a methylation mixture (chloroform:methanol:sulfuric acid, 100:100:1 v/v). A 1 mL aliquot of the obtained solution was transferred to a sealable glass ampoule. Fatty acid methylation was carried out in the ampoule at 100 °C for 2 hours. The resulting fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) were analyzed by capillary gas chromatography with flame-ionization detection (FID) (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Individual fatty acids were identified by comparing their retention times to those of known standards (Supelco 37-component FAME Mix, Sigma-Aldrich). Separation was performed on a ZB-FAME capillary column (30 m length). Each formula was analyzed in five replicates (n = 25).

2.4. Amino Acid Profile

To determine the content of amino acids, the samples were subjected to acid hydrolysis prior to chromatographic analysis. Approximately 10 mg of each homogenized sample was weighed into a glass ampoule, and 0.5 mL of a hydrolysis solution (6 M HCl containing 1% 2-mercaptoethanol and 3% phenol) was added. The ampoules were flame-sealed and heated in an oven at 110 °C for 24 hours. After hydrolysis, the ampoules were cooled and then opened. The hydrolysates were placed in a vacuum dryer and dried at 60 °C under reduced pressure for 24 hours to remove residual HCl. Dry residue was reconstituted in 1 mL of the buffer (10 mM ammonium formate in water, pH 3.2) and sonicated in an ultrasonic bath for around 15 seconds. The solution was then diluted 1:10 with acetonitrile, stirred, and centrifuged (14,000 rpm, 10 min). The supernatant was transferred to chromatography vials for analysis. The chromatographic analysis was performed using a Vanquish Core UHPLC system (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) coupled with a TSQ Fortis triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). Separation was achieved on a Kinetex HILIC column (150 × 2.1 mm, 2.6 µm; Phenomenex) with mobile phase A (water:buffer 9:1) and mobile phase B (acetonitrile:buffer 9:1). Amino acids were identified by positive electrospray ionization (ESI) in selected reaction monitoring (SRM) mode. The parameters of parent and fragment ions of each amino acid are given in

Table 1. Amino acids were quantified by preparing calibration curves for each amino acid standard. Each formula was analyzed in five replicates (n = 25).

2.5. Mechanical Analyses

Compressive strength tests were conducted using a TA.HD.Plus Texture Analyzer (Stable Microsystems, Surrey, UK). The textural parameters of feed granules were determined with a 35 mm cylindrical probe. The probe compresses the sample at a strain rate of 5 mm·min⁻¹. The results were used to determine the following parameters: hardness, defined as the force required to crush the sample; fracturability, defined as the tendency to deform and represented by strain behavior under the applied load until the formation of the first noticeable crack; and stiffness, defined as resistance to deformation. Thirty granules of each formula were used in compressive strength tests (n=150).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The assumption of linearity and normality was checked before statistical analysis. Two-dimensional scatter plots of the analyzed variables were generated for the linearity analysis. The assumption of normality was validated using histograms and residual normality plots. Mean (M) values and standard deviation (±; SD) were calculated for all data. Significant differences between the results of nutrient analyses, fatty acid profiles, amino acid profiles, and mechanical parameters (dependent variables) of the developed formulas (qualitative variables) were determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Before ANOVA, the homogeneity of variance was determined using Levene's test. Tukey’s HSD test was applied to determine significant differences between groups at p < 0.05. Data were processed statistically in the Statistica 13.3 program (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Nutritional Value

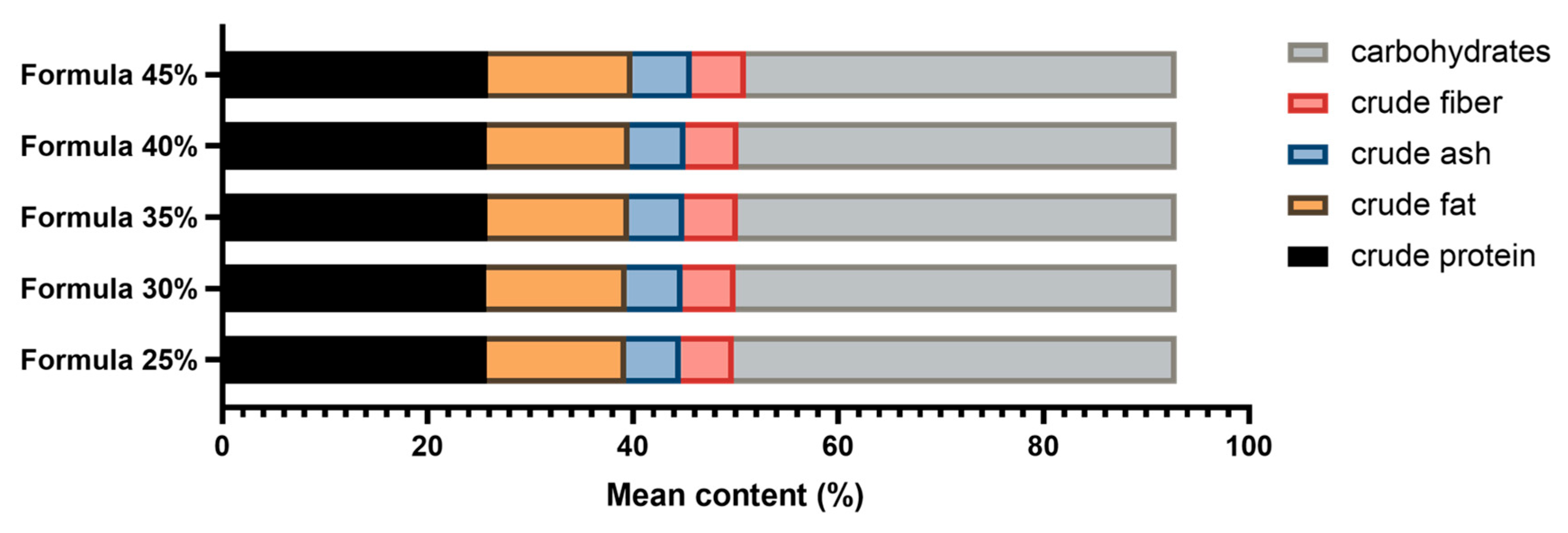

The crude protein content of all five formulas remained relatively consistent at around 25.7–25.9% on a dry matter basis. In Formula 25%, the mean crude protein content was determined at 25.77% (SD = 0.92%), crude fat content – 13.56% (SD = 0.78%), crude ash content – at 5.36% (SD = 0.55%), crude fiber content – at 5.16% (SD = 0.59%), and carbohydrate content – at 43.15% (SD = 1.46%). This formula was characterized by a balanced macronutrient profile, moderate protein content, and the highest carbohydrate content. In Formula 30%, the protein content reached 25.73% (SD = 0.87%) and was practically identical to that of Formula 25%. Crude fat content was slightly higher at 13.68% (SD = 0.68%); crude ash content was 5.41% (SD = 0.59%); crude fiber content was nearly identical to that noted in Formula 25% at 5.17% (SD = 0.65%), and carbohydrate content was slightly lower at 43.01% (SD = 1.36%).

In Formula 35%, crude protein content was determined at 25.83% (SD = 0.78%); crude fat content was higher at 13.79% (SD = 0.65%); crude ash content was similar at 5.37% (SD = 0.43%), and crude fiber content was slightly higher at 5.22% (SD = 0.49%). Carbohydrate content was lower at 42.79% (SD = 1.04%), which suggests that this parameter decreased with increasing inclusion levels of

T. molitor meal. The analysis of Formula 40% revealed similar trends. This formula had a crude protein content of 25.75% (SD = 0.95%) and the highest crude fat content of 13.92% (SD = 0.68%). Crude ash content was 5.42% (SD = 0.67%); crude fiber content was 5.20% (SD = 0.57%), and the content of carbohydrates decreased to 42.61% (SD = 1.12%). In Formula 45%, crude protein content reached 25.90% (SD = 0.84%) and was similar to that observed in other formulas. Crude fat content was 14.07% (SD = 0.74%); crude ash content was 5.40% (SD = 0.49%); crude fiber content was 5.24% (SD = 0.53%), and the content of carbohydrates was lowest at 42.39% (SD = 1.33%). These results indicate that partial replacement of conventional feed ingredients with

T. molitor meal did not significantly affect protein levels, but influenced other macronutrients. In particular, fat content increased and carbohydrate content decreased with a rise in the dietary inclusion levels of mealworm meal. Detailed data are presented in

Table 2 and

Figure 1.

3.2. Fatty Acid Profile

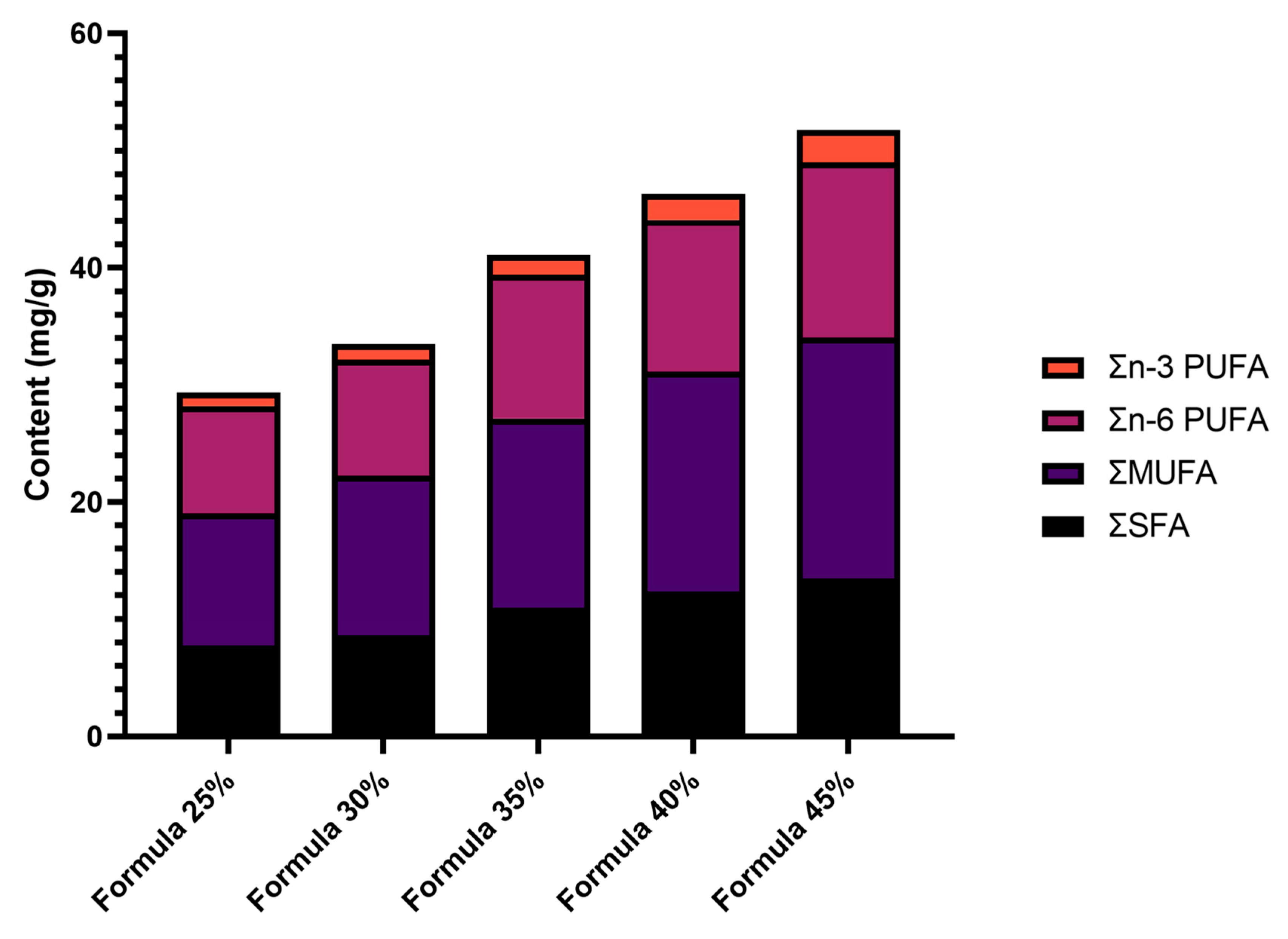

The examined formulas differed in the content of saturated fatty acids (SFAs), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-6 PUFAs), and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs).

The content of total SFAs (ΣSFAs) increased gradually in all formulas, from 7.77 mg/g in Formula 25% to 13.45 mg/g in Formula 45%. The content of total MUFAs (ΣMUFAs) also increased from 11.26 mg/g in Formula 25% to 20.58 mg/g in Formula 45%, which indicates that MUFA levels increase with a rise in the proportions of mealworm meal.

The content of n-6 PUFA also increased with a rise in the inclusion levels of

T. molitor meal, from 9.16 mg/g in Formula 25% to 14.97 mg/g in Formula 45%. The content of n-3 PUFA followed a similar upward trend, increasing from 1.15 mg/g in Formula 25% to 2.76 mg/g in Formula 45%. Detailed data are presented in

Table 3 and

Figure 2.

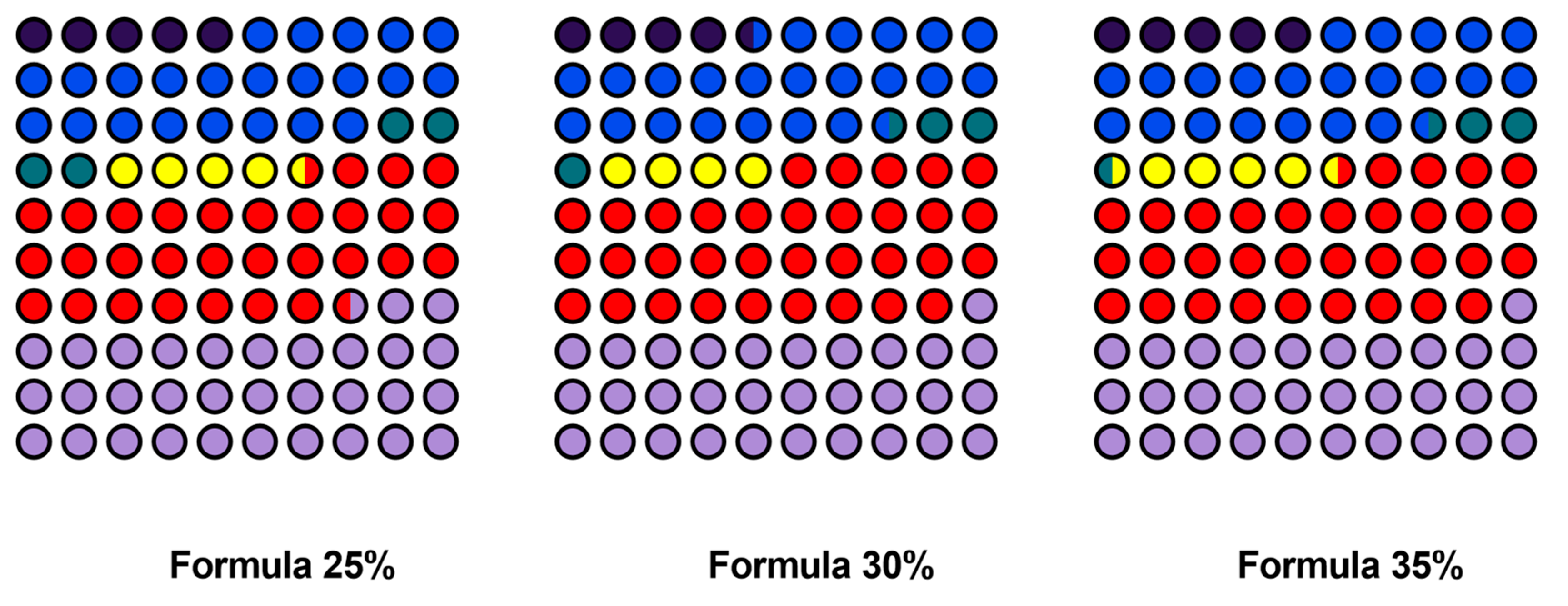

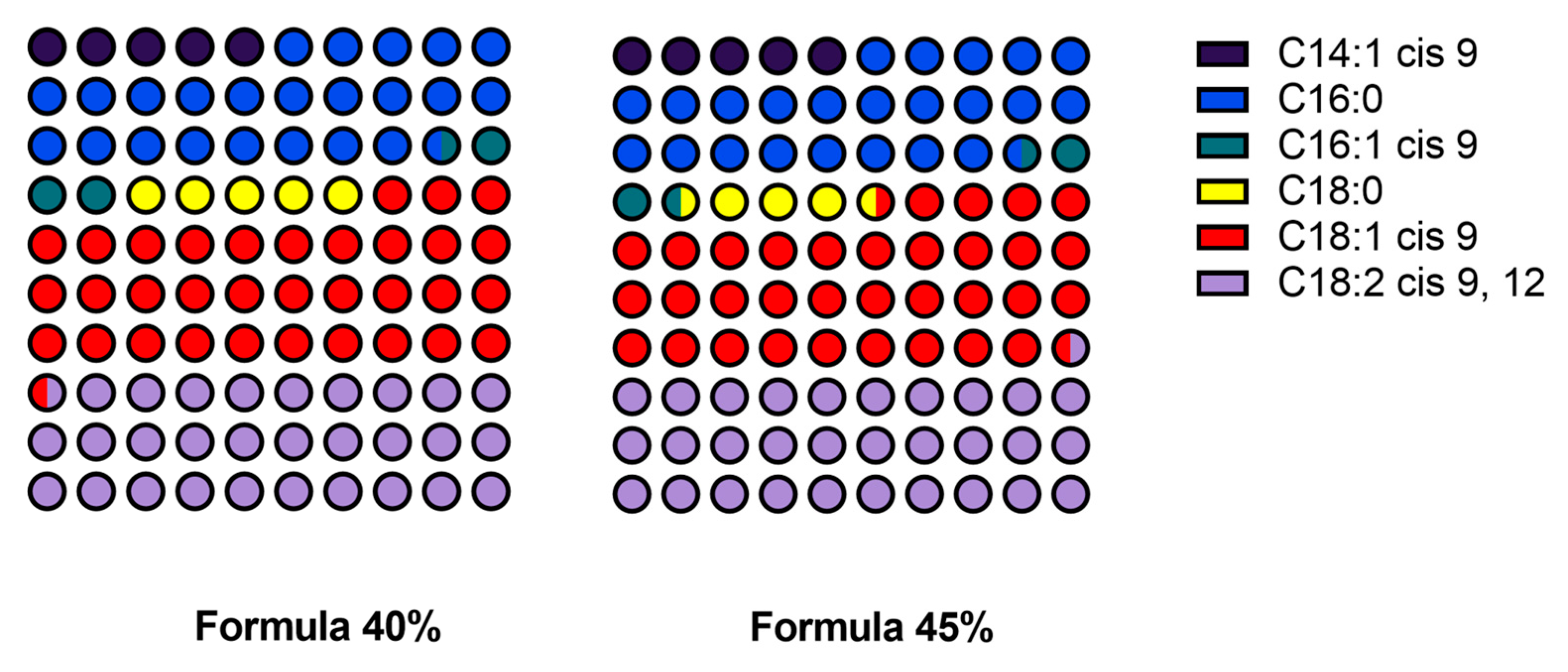

The fatty acid profile of the developed formulas shows clear differences in the concentrations of the examined fatty acids. The mean content of myristoleic acid (C14:1 cis 9) increased from 1.39 mg/g in Formula 25% (SD = 0.32 mg/g) to 2.38 mg/g in Formula 45% (SD = 0.38 mg/g). The content of palmitic acid (C16:0) also increased steadily from 6.45 mg/g (SD = 0.79 mg/g) in Formula 25% to 11.48 mg/g (SD = 0.13 mg/g) in Formula 45%. The content of palmitoleic acid (C16:1 cis 9) was relatively similar in all formulas, ranging from 1.08 mg/g in Formula 35% (SD = 0.39 mg/g) to 1.68 mg/g in Formula 45% (SD = 0.21 mg/g). The mean content of stearic acid (C18:0) was lowest at 1.30 mg/g (SD = 0.32 mg/g) in Formula 30%, and highest at 2.09 mg/g (SD = 0.63 mg/g) in Formula 40%, and somewhat lower at 1.96 mg/g (SD = 0.04 mg/g) in Formula 45%. The content of oleic acid (C18:1 cis 9) increased steadily from 8.69 mg/g (SD = 0.90 mg/g) in Formula 25% to 16.53 mg/g (SD = 0.20 mg/g) in Formula 45%. The content of linoleic acid (C18:2 cis 9, 12) also increased from 9.16 mg/g (SD = 0.98 mg/g) in Formula 25% to 14.97 mg/g (SD = 0.11 mg/g) in Formula 45%. A moderate increase was observed in the content of alpha-linolenic acid (C18:3 cis 9, 12, 15), from 1.01 mg/g (SD = 0.10 mg/g) in Formula 25% to 2.76 mg/g (SD = 0.48 mg/g) in Formula 45%. However, the content of many fatty acids, including caproic acid (C6:0), caprylic acid (C8:0), capric acid (C10:0), undecanoic acid (C11:0), lauric acid (C12:0), tridecanoic acid (C13:0), pentadecanoic acid (C15:0), heptadecanoic acid (C17:0), and eicosanoic acid (C20:0), was below the limit of detection (< 0.04 mg/g) in all formulas. Detailed data are presented in

Table 4 and

Figure 3.

The ANOVA revealed significant differences in the content of the major fatty acids in the examined formulas. The content of myristoleic acid (C14:1 cis 9) differed significantly (p < 0.05) across the analyzed formulas. Tukey’s post-hoc test revealed significant differences in this parameter between Formula 25% and Formula 45%, and between Formula 25% and Formula 40%. The mean content of myristoleic acid increased from 1.39 mg/g (SD = 0.32) in Formula 25% to 2.38 mg/g (SD = 0.38) in Formula 45%. Palmitic acid (C16:0) levels also differed significantly across formulas, and Tukey's HSD test revealed the greatest differences (p < 0.05) between Formula 25% (6.45 mg/g, SD = 0.79) and Formula 45% (11.48 mg/g, SD = 0.13). Highly significant differences (p < 0.01) in the content of oleic acid (C18:1 cis 9) were also noted between Formula 25% (8.69 mg/g, SD = 0.90) and Formula 45% (16.53 mg/g, SD = 0.20), with intermediate values in the remaining formulas. The ANOVA also revealed significant differences (p < 0.01) in the content of linoleic acid (C18:2 cis 9, 12) across formulas, and Tukey's test demonstrated that the differences between Formula 25% (9.16 mg/g, SD = 0.98) and Formula 45% (14.97 mg/g, SD = 0.11) were statistically significant. In contrast, no significant differences (p>0.05) were noted in the content of alpha-linolenic acid (C18:3 cis 9, 12, 15), which suggests that the concentration of this fatty acid was not substantially influenced by the inclusion level of mealworm meal.

3.3. Amino Acid Profile

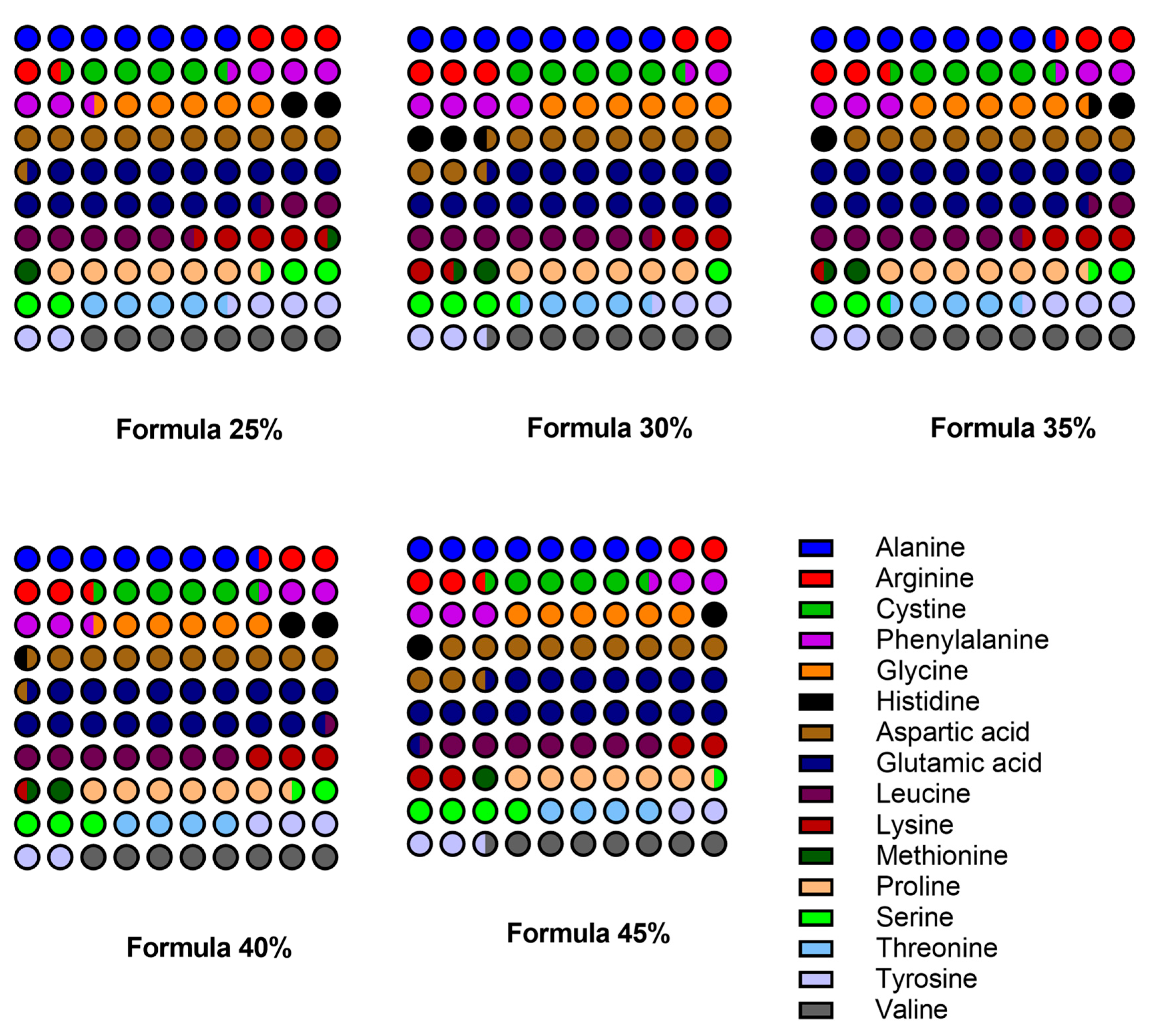

The amino acid composition of the feeds was relatively similar at different T. molitor inclusion levels. The developed formulas were most abundant in alanine, aspartic acid, and glutamic acid, and each of these amino acids made a significant contribution to total protein content. The formulas with the highest inclusion levels of mealworm meal (40% and 45%) were most abundant in several amino acids, but the overall differences were not significant. For instance, alanine content ranged from 7.22% (of protein, w/w) in Formula 25% to 8.16% in Formula 45%. The content of lysine, an essential amino acid, decreased from 4.35% in Formula 25% to 3.88% in Formula 45%. Methionine content was relatively low in all formulas and also decreased slightly from 1.53% to 1.34% with increasing inclusion levels of T. molitor meal.

The statistical analysis revealed no significant differences (

p > 0.05) in the content of individual amino acids across the compared formulas. This observation indicates that the inclusion level of

T. molitor meal (25% to 45%) did not induce significant changes in the amino acid profile of the feeds. The differences in the content of selected amino acids (lysine and methionine) were too small to be deemed significant. The amino acid profile of the formulas is presented in

Table 5, and the trends for selected amino acids are shown in

Figure 4.

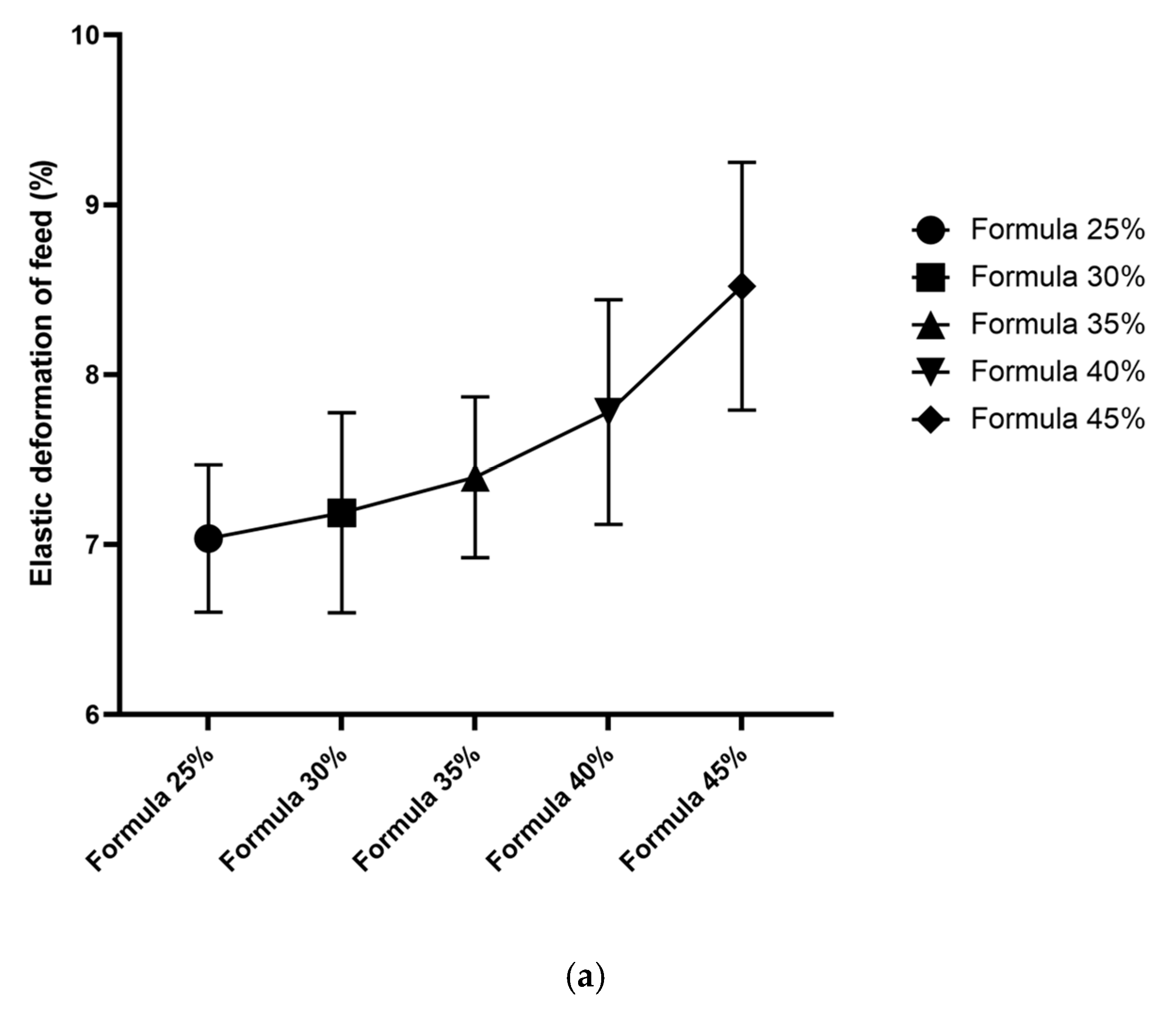

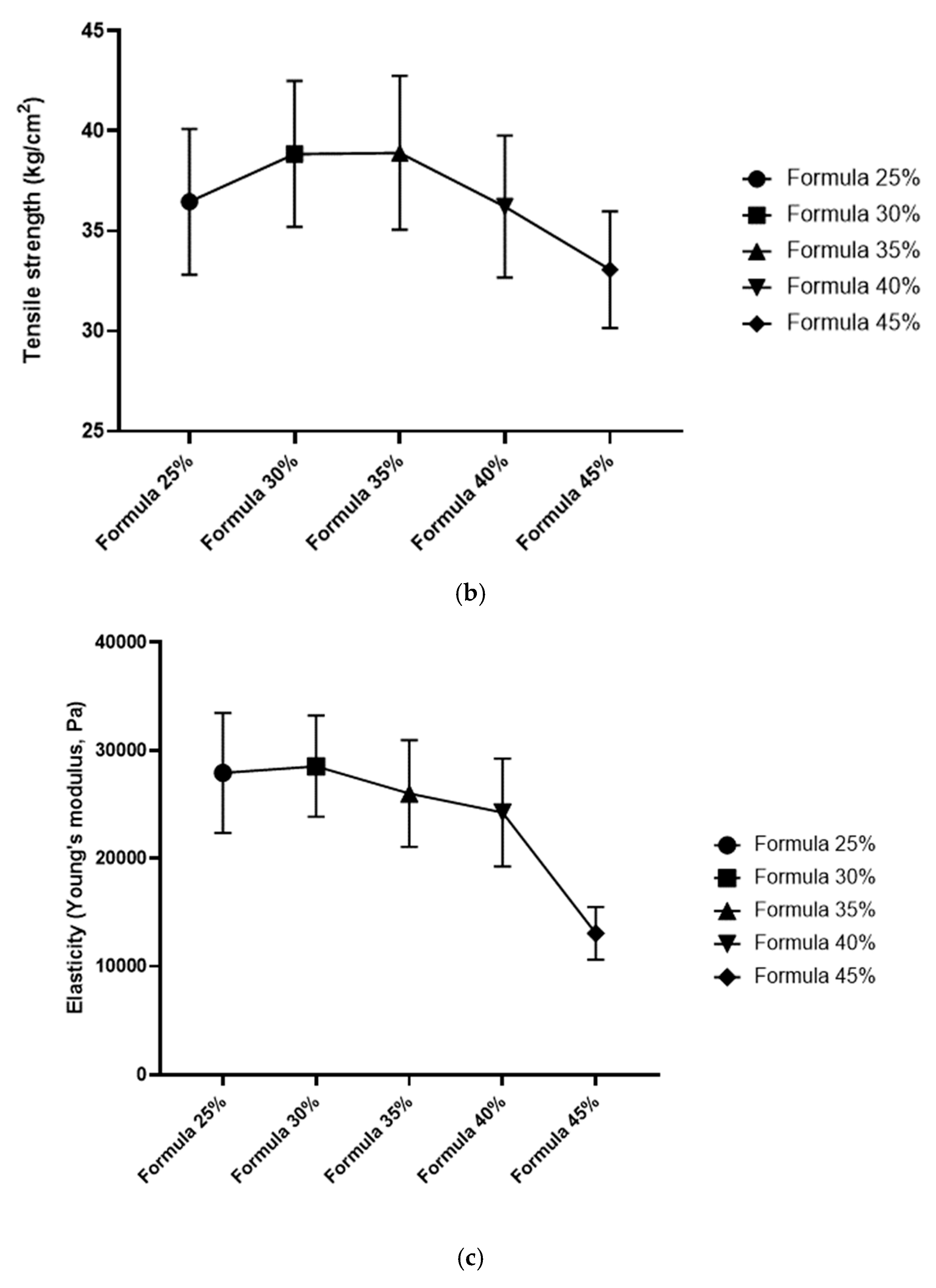

3.4. Mechanical Properties

In Formula 25%, mean fracturability was determined at 7.04% (SD = 0.55); mean hardness (crushing force) was 330.56 N (SD = 3.33), and stiffness (elastic modulus-like behavior) reached 46.2 N/mm (SD = 2.1). In Formula 30%, fracturability increased to 7.58% (SD = 0.49), which indicates that these pellets were more susceptible to deformation before cracking. Hardness was slightly lower than in Formula 25% at 324.10 N (SD = 4.01), and stiffness was determined at 44.8 N/mm (SD = 1.9). In Formula 35%, fracturability increased to 8.12% (SD = 0.50); hardness was determined at 315.44 N (SD = 5.12), and stiffness decreased to 43.5 N/mm (SD = 2.3). A further decline in mechanical properties was noted in Formula 40%, where fracturability reached 8.65% (SD = 0.60) and hardness – 309.30 N (SD = 4.77). Formula 45% was characterized by the highest deformability, fracturability of 9.20% (SD = 0.58), and the lowest hardness at 300.22 N (SD = 5.50). Formula 45% was also characterized by the lowest stiffness at around 41.0 N/mm (SD = 2.5).

Feeds with higher inclusion levels of T. molitor meal were composed of granules that were generally softer (required less force to break) and more deformable (higher ability to tolerate strain before fracture). Stiffness tended to decline, which suggests that the granules of formulas with higher insect meal content were more elastic or less rigid. All differences in the mechanical parameters of the compared formulas were statistically significant (p < 0.05) in ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test. The post-hoc test revealed that formulas with higher insect meal content (40%, 45%) were characterized by significantly higher elastic deformation and lower hardness than those with lower insect meal content (25%, 30%).

4. Discussion

4.1. Nutritional Value

The study demonstrated that crude protein content was fairly similar in all formulas, whereas the content of crude fat, crude ash, and crude fiber increased gradually with a rise in the inclusion levels mealworm meal. In contrast, carbohydrate concentration decreased as the levels of

T. molitor meal increased, suggesting a shift in the macronutrient composition of the formulas. The detailed analyses of the nutritional profiles of each formula revealed minor variations in nutrient content, and the results may inform dietary formulations based on specific nutritional goals. The protein content of the studied formulas remained relatively stable, ranging from 25.73% to 25.9%. This observation suggests that the replacement of insect meal with other ingredients (potato by-products or fish oil) did not significantly affect crude protein content. However, a slight increase in fat content was noted with a rise in the inclusion levels of insect meal, from 13.56% in Formula 25% to 14.07% in Formula 45%. These results corroborate the findings of other authors. Rumpold and Schlüter [

31] conducted a comprehensive review of the nutritional value of edible insects, highlighting that

T. molitor contains approximately 47–60% crude protein and 30–35% fat on a dry matter basis. Although the above values are higher than those observed in the current study, it should be noted that the analyzed formulas were designed to meet a specific crude protein target (28% ± 2.5%), which implies that insect meal was likely diluted with other ingredients to achieve this target. Broekman et al. [

32] also examined insect-based pet food, in particular formulations containing

H. illucens. The protein content of these formulations was estimated at 22-25%, which is similar to that noted in the current study. The above supports the argument that insect-based meals pose a viable alternative to traditional sources of protein and have comparable macronutrient profiles in terms of protein and fat content. In addition, the crude fat content reported by Broekman et al. [

32] (12-16%) also aligns closely with the current findings (13.56% - 14.07%), indicating that insect-based meals can provide a balanced fat profile in dog food formulations. Moreover, Bosch et al. [

33] analyzed various insect species, including

T. molitor, and confirmed that insects offer a macronutrient profile that can be suitable for dog food, particularly in terms of protein and fat content. The cited authors also concluded that insects can be a rich source of selected essential amino acids, which is a crucial consideration in the process of formulating complete diets for dogs.

4.2. Fatty Acid Profile

The content of SFAs, MUFAs, and PUFAs (n-6 and n-3) increased with a rise in the inclusion levels of T. molitor meal. This indicates that insect meal can be a valuable source of fatty acids for dog food formulas. This observation may have important implications for the nutritional value and health benefits of these formulas. Mealworm meal was abundant in several saturated and unsaturated fatty acids, including palmitic, stearic, oleic, linoleic, and alpha-linolenic acids, whereas many other fatty acids were below the limit of detection.

The designed formulas differed significantly in fatty acid composition, and the concentrations of both SFAs and MUFAs increased with a rise in the inclusion levels of insect meal. Notably, oleic acid (C18:1) content doubled from 8.69 mg/g in Formula 25% to 16.53 mg/g in Formula 45%, while the content of linoleic acid (C18:2), an essential n-6 PUFA, also increased significantly from 9.16 mg/g to 14.97 mg/g.

Similar observations were made by Oonincx et al. [

34] who studied the lipid composition of various edible insects, including

T. molitor. Their research highlighted that

T. molitor is a rich source of oleic and linoleic acids that are essential for maintaining healthy skin and coat in dogs. Borrelli et al. [

35] also found that the content of n-6 and n-3 PUFAs increased with a rise in the inclusion levels of insect meal, and concluded that insect meal can be an excellent source of unsaturated fatty acids, especially in comparison with conventional meat-based ingredients.

These findings are important because dogs require specific ratios of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids to maintain optimal health. Omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs provide health benefits by modulating the immune response and exerting anti-inflammatory effects, and they can be particularly helpful in managing conditions such as osteoarthritis [

36] and atopic dermatitis [

37]. Diets rich in n-3 fatty acids can improve renal function by promoting balanced inflammatory responses and supporting cardiovascular health, which is especially important for older or at-risk dogs [

38,

39]. In the current study, the concentrations of n-3 and n-6 PUFAs increased steadily with a rise in the inclusion levels of mealworm meal (from 1.15 mg/g to 2.76 mg/g and from 9.16 mg/g to 14.97 mg/g, respectively), which aligns with the growing body of evidence that the synergistic effects of these fatty acids enhance overall canine health. Furthermore, the proportion of MUFAs such as C18:1 cis 9 is also significantly higher in formulations with higher fat content, which may improve energy metabolism and further benefit active or aging dogs [

40]. The present results indicate that feeds with a higher content of insect meal may have a more balanced fatty acid profile, which may be particularly beneficial for dogs with inflammatory conditions or skin sensitivities. Some of the detected fatty acids also have antibacterial properties [

41].

4.3. Amino Acid Profile

The study revealed slight variations in the amino acid content of the analyzed formulas. The concentration of some amino acids was fairly stable, whereas greater fluctuations were noted in the levels of other amino acids. Formulas with the highest inclusion levels of T. molitor meal were most abundant in several amino acids (including alanine, aspartic acid, and glutamic acid), which implies that insect meal could enhance their nutritional value.

The amino acid profile remained relatively stable in all formulas, and no significant differences in the content of most amino acids were observed between the formulas. The studied formulas were most abundant in alanine, aspartic acid, and glutamic acid, while a slight decrease in lysine content was noted as the proportion of T. molitor meal increased.

Similar results were reported by Gasco et al. [

42] who evaluated the amino acid content of insect-based dog food and found that

T. molitor meal can provide adequate levels of essential amino acids for dogs. However, the fact that higher inclusion levels of mealworm meal induced a slight decrease in lysine content could be of concern because lysine is an essential amino acid for dogs that promotes muscle development and overall health. Ravzanaadii et al. [

17] found that while insect-based proteins are generally rich in essential amino acids, lysine content is sometimes lower compared to conventional meat proteins, which implies that commercial formulations may require supplementation to meet dietary requirements. Despite these concerns, the present study demonstrated that the amino acid profile of insect-based meals, in particular

T. molitor meal, is comparable to that of traditional meat proteins. The presence of other essential amino acids, such as methionine and cystine, in adequate quantities supports the nutritional viability of these formulas. While edible insects are rich in many nutrients, they tend to be relatively low in methionine compared to traditional sources of animal protein. Methionine is an essential amino acid for dogs because it plays a key role in keratin production and overall protein metabolism, and diets deficient in this amino acid may lead to poor coat quality, hair loss, dullness, and skin problems. Therefore, diets based heavily on insect protein may require methionine supplementation to ensure optimal health and coat condition in dogs.

4.4. Mechanical Properties

Mechanical tests revealed that higher inclusion levels of T. molitor meal increased the softness and flexibility of feed granules. Specifically, formulas containing higher proportions of insect meal were characterized by higher elastic deformation (granules could be compressed further before breaking) and lower breaking strength. In practical terms, formulas with higher inclusion levels of T. molitor meal consisted of granules that were easier to chew (softer) and less brittle (more flexible). The above could affect the palatability and chewiness of dog food. For instance, very hard granules might provide dental benefits by removing plaque, but they could be difficult to chew for puppies or older dogs with dental issues. These groups of animals require dry food with slightly softer granules.

The present results align with the findings of Purschke et al. [

43] who observed that the inclusion of insect-derived ingredients and certain processing methods can significantly affect the textural properties of food products. They observed changes in the elasticity and plasticity of insect-based extrudates, which were similar to the trends noted in pellet elasticity and deformation [

43]. In this study, significant differences in mechanical behavior were observed between formulas with the highest (40% and 45%) and the lowest (25% and 30%) inclusion levels of

T. molitor meal. This observation suggests that the texture of feed granules may change considerably when the inclusion level exceeds a certain threshold. The likely explanation is that

T. molitor meal has different binding and structural characteristics than plant-based components. Insect meals may contain chitin and have high protein content, but unlike cereals, they do not contain starch, which affects granule formation during extrusion and pelletization.

Meléndez-Rodríguez [

44] emphasized that mechanical resilience plays an important role in feed matrices by preserving their shape and integrity during handling and storage. Formulas with higher inclusion levels of insect meal were softer, but their structural integrity was preserved. Crumbling was not observed during normal handling, but these formulas were more likely to break under lower stress in mechanical tests. According to Recupido et al. [

45], changes in the composition of bio-based composite materials could lead to increased softness at higher inclusion levels of certain components. By analogy, the present findings suggest a similar effect: the flexibility of granules increased with a rise in the inclusion levels of

T. molitor meal. This could affect product durability as softer granules might be more prone to breakage in transport. However, the hardness of all studied formulas was within the range of values typical of dry dog food.

In practical feeding scenarios, flexible granules could be more desirable for dogs with certain health issues (such as weaker jaws or dental concerns) and could potentially increase palatability due to ease of chewing. In the future, dog food manufacturers might consider combining insect meals with texturizing agents or adjusting processing conditions to fine-tune the hardness and brittleness of granules.

4.5. Compliance With FEDIAF Guidelines

The developed formulas were examined for fatty acid and amino acid content to assess their compatibility with the European Pet Food Industry Federation (FEDIAF) Nutritional Guidelines for Dogs [

46] and ensure that they meet standard requirements for canine diets. According to FEDIAF, canine diets should have a balanced ratio of fatty acids (with sufficient levels of linoleic acid, an omega-6 fatty acid, and alpha-linolenic acid, an omega-3 fatty acid) and provide all essential amino acids above the minimum recommended amounts. The dietary fats for canine nutrition should include a balance of SFAs, MUFAs, and PUFAs, particularly omega-6 and omega-3 PUFAs, which are essential for skin health, coat quality, and inflammatory modulation. The SFA content of the tested formulas increased progressively with a rise in the inclusion levels of

T. molitor meal, from 7.77 mg/g in Formula 25% to 13.45 mg/g in Formula 45%, which indicates that these feeds provide adequate amounts of energy and support cell membrane integrity. The content of MUFAs also increased from 11.26 to 20.58 mg/g, which is a desirable outcome because these fatty acids are a source of readily metabolizable energy, and their beneficial impact on cardiovascular health has been demonstrated in other species. Notably, the content of omega-6 PUFAs increased from 9.16 to 14.97 mg/g in the studied formulas, which is consistent with FEDIAF’s recommendations concerning skin health and immune function. In turn, the content of omega-3 PUFAs increased from 1.15 to 2.76 mg/g, indicating that the anti-inflammatory effects of the tested formulas are slightly below the ideal ratios and that additional supplementation may be required to achieve the optimal balance.

Based on FEDIAF’s guidelines, the formulated feeds were also analyzed for the content of essential amino acids that are crucial for muscle health, immune function, and enzyme activity in dogs [

46]. The content of alanine, an important glucogenic amino acid, ranged from 7.22% to 8.16%, indicating that alanine levels were high enough to trigger gluconeogenic pathways that are necessary during endurance or stress. Arginine, which plays a key role in immune function and ammonia removal, was within the recommended levels in all formulas (4.49-4.79%). The formulas were also sufficiently abundant in histidine (2.00-2.29%) which is necessary for histamine synthesis and hemoglobin structure. However, lysine levels (4.35-3.88%) tended to decline in formulas with the highest inclusion levels of insect meal, which implies that they should be monitored to ensure adequate supply of lysine that plays a role in calcium absorption and bone health. Methionine levels also decreased from 1.53% to 1.34% and approximated the minimum recommended intake levels, which suggests that the designed formulations may need to be adjusted to enhance protein synthesis and antioxidant protection.

6. Patents

The present study gave rise to patent application P.443579 – Hypoallergenic dog food. The patent covers a hypoallergenic feed formulation for dogs suffering from food-responsive enteropathies. Hypoallergenic dog food contains T. molitor meal (inclusion level: 10% to 60%, preferably 35%), potato and/or sweet potato by-products (10% to 65%, preferably 48%), plant substrates of the plantain family (0.01% to 15%, preferably 7.3%), animal or vegetable fat (0.1% - 15%), herbs and minerals (0.01% to 5%, preferably 1.8%), berries (0.01% to 8%, preferably 0.6%), functional additives such as water- and fat-soluble vitamins (0.01% to 15%, preferably 6.3%), and plants of the flax family (0.01% to 5%, preferably 1%). The patented formulation has the following nutritional composition: crude protein – 11% to 41%, (preferably 25%), crude fat – 3% to 27%, (preferably 15%), crude ash – 1% to 9%, (preferably 5%), crude fiber –1% to 9%, (preferably 5%).

Figure 1.

Macronutrient content of five dog food formulas with increasing inclusion levels of Tenebrio molitor meal. Annotation: insect meal was replaced with potato by-products or fish oil in the same proportions to maintain the original parameters.

Figure 1.

Macronutrient content of five dog food formulas with increasing inclusion levels of Tenebrio molitor meal. Annotation: insect meal was replaced with potato by-products or fish oil in the same proportions to maintain the original parameters.

Figure 2.

Changes in the content of saturated fatty acids (SFAs), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-6 PUFAs), and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs) with increasing inclusion levels of Tenebrio molitor meal in five dog food formulas.

Figure 2.

Changes in the content of saturated fatty acids (SFAs), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-6 PUFAs), and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs) with increasing inclusion levels of Tenebrio molitor meal in five dog food formulas.

Figure 3.

The content of the major fatty acids in five dog food formulas with increasing inclusion levels of Tenebrio molitor meal.

Figure 3.

The content of the major fatty acids in five dog food formulas with increasing inclusion levels of Tenebrio molitor meal.

Figure 4.

The content of the major amino acids in five dog food formulas with increasing inclusion levels of Tenebrio molitor meal.

Figure 4.

The content of the major amino acids in five dog food formulas with increasing inclusion levels of Tenebrio molitor meal.

Figure 5.

Mechanical properties of granules in five dog food formulas with increasing levels of Tenebrio molitor meal: (a) fracturability (% strain at first crack), (b) hardness (crushing force, N), and (c) stiffness (resistance to deformation). Key: Error bars represent SD (n = 30 per formula).

Figure 5.

Mechanical properties of granules in five dog food formulas with increasing levels of Tenebrio molitor meal: (a) fracturability (% strain at first crack), (b) hardness (crushing force, N), and (c) stiffness (resistance to deformation). Key: Error bars represent SD (n = 30 per formula).

Table 1.

Parameters of parent and fragment ions in the chromatographic analysis of amino acids.

Table 1.

Parameters of parent and fragment ions in the chromatographic analysis of amino acids.

| Amino acid |

Parent ion (m/z) |

Fragment ion (m/z) |

| Alanine |

90.014 |

43.970 |

| Arginine |

175.100 |

70.054 |

| Cystine |

241.024 |

151.970 |

| Phenylalanine |

166.062 |

120.000 |

| Glycine |

75.988 |

30.196 |

| Histidine |

156.074 |

110.054 |

| Hydroxyproline |

132.075 |

68.042 |

| Aspartic acid |

134.052 |

74.042 |

| Glutamic acid |

148.062 |

84.125 |

| Leucine/Isoleucine |

132.112 |

86.196 |

| Lysine |

147.112 |

84.125 |

| Methionine |

150.062 |

133.071 |

| Proline |

116.112 |

70.071 |

| Serine |

106.062 |

60.071 |

| Threonine |

120.088 |

103.125 |

| Tyrosine |

188.114 |

147.125 |

| Valine |

118.112 |

72.071 |

Table 2.

Mean content of crude protein, fat, ash, fiber, and carbohydrates in five dog food formulas with increasing inclusion levels of Tenebrio molitor meal.

Table 2.

Mean content of crude protein, fat, ash, fiber, and carbohydrates in five dog food formulas with increasing inclusion levels of Tenebrio molitor meal.

| Formula |

Crude protein |

Crude fat |

Crude ash |

Crude fiber |

Carbohydrates |

| 25% |

25.77 ± 0.92 |

13.56 ± 0.78 |

5.36 ± 0.55 |

5.16 ± 0.59 |

43.15 ± 1.46 |

| 30% |

25.73 ± 0.87 |

13.68 ± 0.68 |

5.41 ± 0.59 |

5.17 ± 0.65 |

43.01 ± 1.36 |

| 35% |

25.83 ± 0.78 |

13.79 ± 0.65 |

5.37 ± 0.43 |

5.22 ± 0.49 |

42.79 ± 1.04 |

| 40% |

25.75 ± 0.95 |

13.92 ± 0.68 |

5.42 ± 0.67 |

5.20 ± 0.57 |

42.71 ± 1.65 |

| 45% |

25.90 ± 1.34 |

14.07 ± 0.86 |

5.73 ± 0.83 |

5.29 ± 0.69 |

42.01 ± 2.04 |

Table 3.

Fatty acid profile of five dog food formulas with increasing inclusion levels of Tenebrio molitor meal. The table presents the concentrations (in mg/g feed, dry matter basis) of the major fatty acid classes: saturated fatty acids (SFAs), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-6 PUFAs), and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs).

Table 3.

Fatty acid profile of five dog food formulas with increasing inclusion levels of Tenebrio molitor meal. The table presents the concentrations (in mg/g feed, dry matter basis) of the major fatty acid classes: saturated fatty acids (SFAs), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-6 PUFAs), and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs).

| Formula (% T. molitor meal) |

SFAs (mg/g) |

MUFAs (mg/g) |

n-6 PUFAs (mg/g) |

n-3 PUFAs (mg/g) |

| 25% |

7.77 ± 0.30 |

11.26 ± 0.50 |

9.16 ± 0.51 |

1.15 ± 0.10 |

| 30% |

8.90 ± 0.35 |

13.58 ± 0.62 |

10.74 ± 0.48 |

1.60 ± 0.12 |

| 35% |

10.12 ± 0.41 |

16.02 ± 0.70 |

12.83 ± 0.53 |

2.10 ± 0.15 |

| 40% |

11.30 ± 0.37 |

18.43 ± 0.55 |

13.64 ± 0.50 |

2.45 ± 0.14 |

| 45% |

13.45 ± 0.44 |

20.58 ± 0.60 |

14.97 ± 0.45 |

2.76 ± 0.16 |

Table 4.

Fatty acid profile of five dog food formulas with increasing inclusion levels of Tenebrio molitor meal. The table presents the concentrations (in mg/g feed, dry matter basis) of the major fatty acid classes: saturated fatty acids (SFAs), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-6 PUFAs), and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs).

Table 4.

Fatty acid profile of five dog food formulas with increasing inclusion levels of Tenebrio molitor meal. The table presents the concentrations (in mg/g feed, dry matter basis) of the major fatty acid classes: saturated fatty acids (SFAs), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-6 PUFAs), and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs).

| Fatty acid |

25% |

30% |

35% |

40% |

45% |

| C14:1 cis-9 |

1.39 ± 0.32 |

1.52 ± 0.28 |

1.95 ± 0.53 |

2.18 ± 0.33 |

2.38 ± 0.38 |

| C16:0 |

6.45 ± 0.79 |

7.31 ± 0.18 |

8.92 ± 0.97 |

10.28 ± 0.22 |

11.48 ± 0.13 |

| C16:1 cis-9 |

1.18 ± 0.13 |

1.17 ± 0.17 |

1.08 ± 0.39 |

1.65 ± 0.10 |

1.68 ± 0.21 |

| C18:0 |

1.32 ± 0.22 |

1.30 ± 0.32 |

2.03 ± 0.52 |

2.09 ± 0.63 |

1.96 ± 0.04 |

| C18:1 cis-9 |

8.69 ± 0.90 |

10.95 ± 0.44 |

13.15 ± 1.68 |

14.95 ± 1.42 |

16.53 ± 0.20 |

| C18:2 cis-9,12 |

9.16 ± 0.98 |

9.91 ± 0.69 |

12.27 ± 0.54 |

12.92 ± 0.90 |

14.97 ± 0.11 |

Table 5.

Amino acid concentrations (% of total protein) in five dog food formulas with increasing inclusion levels of Tenebrio molitor meal.

Table 5.

Amino acid concentrations (% of total protein) in five dog food formulas with increasing inclusion levels of Tenebrio molitor meal.

| Amino acid |

25% |

30% |

35% |

40% |

45% |

| Alanine |

7.22 ± 0.16 |

8.04 ± 0.24 |

7.71 ± 0.07 |

7.56 ± 0.27 |

8.16 ± 0.03 |

| Arginine |

4.52 ± 0.36 |

4.79 ± 0.28 |

4.73 ± 0.33 |

4.71 ± 0.35 |

4.49 ± 0.18 |

| Cystine |

4.67 ± 0.14 |

5.61 ± 0.20 |

4.91 ± 0.33 |

5.12 ± 0.07 |

5.02 ± 0.18 |

| Phenylalanine |

6.07 ± 0.38 |

5.33 ± 0.17 |

5.51 ± 0.16 |

5.25 ± 0.43 |

5.41 ± 0.07 |

| Glycine |

5.71 ± 0.07 |

6.41 ± 0.58 |

5.84 ± 0.23 |

5.57 ± 0.39 |

5.94 ± 0.46 |

| Histidine |

2.00 ± 0.16 |

2.29 ± 0.14 |

2.11 ± 0.10 |

2.20 ± 0.17 |

2.16 ± 0.25 |

| Aspartic acid |

10.25 ± 0.58 |

9.92 ± 0.35 |

9.41 ± 0.92 |

10.01 ± 0.89 |

11.52 ± 0.02 |

| Glutamic acid |

16.88 ± 2.28 |

17.82 ± 0.65 |

18.52 ± 1.16 |

19.05 ± 0.78 |

17.97 ± 0.61 |

| Leucine |

8.03 ± 0.23 |

7.27 ± 0.41 |

7.63 ± 0.18 |

7.28 ± 0.54 |

7.34 ± 0.51 |

| Lysine |

4.35 ± 0.33 |

4.00 ± 0.06 |

4.05 ± 0.35 |

3.98 ± 0.15 |

3.88 ± 0.23 |

| Methionine |

1.53 ± 0.06 |

1.57 ± 0.10 |

1.46 ± 0.11 |

1.44 ± 0.11 |

1.34 ± 0.03 |

| Proline |

6.07 ± 0.50 |

5.89 ± 0.42 |

6.48 ± 0.13 |

6.35 ± 0.16 |

6.19 ± 0.42 |

| Serine |

4.55 ± 0.45 |

4.61 ± 0.06 |

4.30 ± 0.22 |

4.50 ± 0.21 |

4.50 ± 0.37 |

| Threonine |

4.41 ± 0.49 |

3.82 ± 0.05 |

3.94 ± 0.21 |

3.93 ± 0.11 |

3.89 ± 0.18 |

| Tyrosine |

5.87 ± 0.30 |

5.29 ± 0.28 |

5.48 ± 0.18 |

5.20 ± 0.24 |

4.50 ± 0.23 |

| Valine |

7.87 ± 0.54 |

7.36 ± 0.70 |

7.93 ± 0.01 |

7.84 ± 0.14 |

7.69 ± 0.47 |