1. Introduction

Meat consumption is increasing and is expected to continue growing. To meet this demand, industrial livestock production is multiplying, raising debates about the environmental, ethical and for health consequences of large-scale meat production. The environmental impact is reflected in increased greenhouse gas emissions, water pollution and deforestation. For this reason, protein alternatives, like those coming from plants, are being sought, trying to simulate the texture and taste of meat [

1]. The term meat analogues distinguish food products that are not made from meat Since 2015, the supply of meat substitute products has increased. That is why, new strategies are being considered to cause a change in consumer expectations, including the development of new products such as burgers, nuggets and other meat products [

2].

Meat substitutes could be a vehicle for increasing the consumption of cereals and legumes as most of the meat analogues that are successfully marketed are derived from plant proteins [

3]. These foods are perceived as healthy and sustainable, in contrast to meat. The most recognised by consumers are tofu, seitan and textured soya. They are fibrous vegetable proteins that are cholesterol-free, low in fat, high in protein and fibre, and rich in other nutrients (vitamins, minerals…). Proteins are usually extracted from plants such as soya, peas or beans, and can be used in different forms: isolated, concentrated or as flour. They can be mixed with ingredients to provide different textures and mouthfeel [

1]. soya has a high nutritional value and is a rich source of protein and bioactive phytochemicals, such as gamma-tocopherols and isoflavones [

4]. Textured soya protein is obtained from defatted soya flour, from which soluble carbohydrates have been removed. The filtrate obtained is textured using extrusion technologies. This methodology provides a specific texture, expanded, moulded, or textured, like meat. In addition, it possesses functional properties such as water retention capacity, gelling power, fat absorption and emulsifying capacity. Soya is also a gluten-free cereal, suitable for the coeliac diet [

5]. Another alternative is seitan, a meat alternative produced from wheat flour gluten, a protein with excellent chewiness and taste properties. It is a product with popular tradition in China [

6]. It is produced by removing starch from wheat flour dough by washing, resulting in a chewy gluten dough [

7]. Furthermore, it is responsible for the formation of meat-like structures, water retention and stabilization during formulation [

6]. Food products containing wheat gluten work as meat extenders and meat analogues. Meat substitutes incorporating seitan are more economical because wheat cultivation is widely distributed throughout the world. On the other hand, oat is a popular cereal because it is affecting glycaemic index and gut microbiota control. It has a high content of quality protein determined by amino acids (lysine, asparagine, aspartic acid and alanine). The main properties of oat include fat-binding capacity, moisturizing, emulsifying, foaming and gelling properties, which can be a positive point for innovation in new foods. Oat protein is being studied as a possible functional ingredient in the incorporation of new foods [

8]. In addition, oat has antioxidant compounds that can keep oils and fats stable against rancidity.

Meat substitutes have advantages due to the fact that many plant foods can be combined or used, the most important of which is that foods can be made for people with dietary diseases, such as those intolerant to gluten. This is because nowadays there is a growing health concern that goes hand in hand with food. One per cent of the world's population has coeliac disease. Coeliac disease is a chronic disease that affects people, causing them to be unable to consume foods containing gluten. These people often suffer from disorders such as difficulty absorbing nutrients from food, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, vomiting and weight loss. In this sense, the food industry is increasing the development of foods for coeliacs, due to the limited variability of foods, so the use of gluten-free cereals such as those mentioned above could be an interesting option [

9].

However, meat analogues have several drawbacks. The main difficulty is the low people’s inclination to switch from animal-based to plant-based foods in their diet [

10], in addition to the difficult technological and sensory development involved in producing these foods. Given that meat is an essential food in the diet, an analogue with the organoleptic characteristics of meat is difficult to reproduce. This makes their success limited. However, the new generation of meat analogues is becoming increasingly palatable due to the modification of their textural characteristics, colour and flavour enhancement, using natural colours and flavourings [

11]. But the main drawback of the meat analogues is the low biological quality of plant-based protein [

12].

At the same time, the consumption of protein sources from unconventional raw materials, such as insects is becoming an option to improve the nutritional value of novel foods as it is an easy and convenient way to enrich foods by means of alternative protein sources [

13]. Alternative animal protein sources symbolise a new milestone in people's diets, but food neophobia, unfamiliarity and poor sensory attributes have been identified as the main barriers preventing people from choosing alternatives to meat [

12]. The consumption of insects is supported by the term entomophagy, an ancient custom practised in many countries around the world, but especially in Southeast Asia, Africa, and Central & South America. In contrast, in Western countries, insect consumption is lower due to the cited neophobia [

14]. Insects are an alternative source of animal protein that currently is being studied due to their economic, environmental, and sustainable benefits. Among the most consumed insects is the yellow mealworm (

Tenebrio molitor), as they become pests in stored foodstuffs such as flour and cereals. This is because their main habitat is characterised by dark and damp places [

15]. The production of these insects is intended to be incorporated into human food, as the larvae are more acceptable to European consumers. They can be marketed whole or in flour form to facilitate their incorporation into food products. Insects are included in the definition of "novel food" [

16]. Larvae are a good source of nutrients, rich in essential amino acid-based, high-value protein, vitamins (vitamin E, vitamin B12, niacin, riboflavin, pantothenic acid and biotin) and minerals (P, Mg, Zn & Mn) [

15]. FAO classifies insect consumption within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (

Figure 1).

The stimulus of the development of these novel foods is expected to continue increasing. Therefore, this research aimed to study the feasibility of using non-traditional raw materials of plant origin to develop burger analogues considering the coeliac population. Furthermore, to achieve a product with high nutritional value T. molitor flour was added. For this, a heuristic and iterative process was carried out to obtain the formulations and study their shelf-life through physicochemical, microbiological, and sensory analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw material

The main raw material of vegetable origin in the developed burger analogues consisted of seitan, textured soya (suitable for coeliacs) and oat. They were purchased from a Spanish supermarket (Mercadona). Seitan was manufactured by Midsona Iberia S.L.U; textured soya was from Laboratorios Almond, S.L and the oat was purchased in flakes (Brüggen®) and ground in the laboratory with a mincer (Mod. A320R1, Moulinex®).

Insect (T. molitor) larvae flour, an alternative protein source, was used to achieve the enrichment of the developed products. It was supplied by the company Insekt Label Biotech S.L. (Bizkaia, Spain). In addition to these products, sodium alginate (Solegraells®), calcium chloride (Carlo Erba®), aromas and species varieties (Carinsa S.L), oat flour (Brüggen®), 100% vegetable spreadable fat (Mercadona), beetroot powder colouring (Sosa Ingredients S.L), sweet paprika powder (Mercadona) and salt (Auchan) were used as ingredients for the burger analogues.

2.2. Experimental design

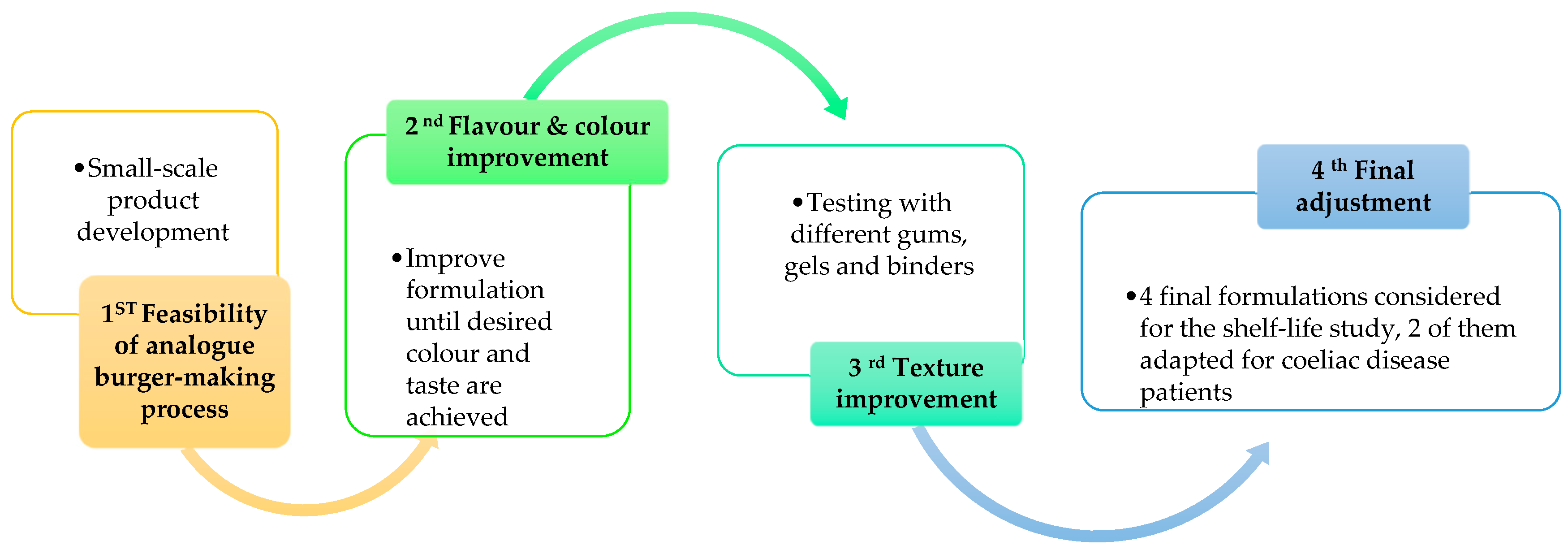

The procedure carried out to develop the burgers was a heuristic methodology based on an iterative process [

17]. The results of the process were the starting point for the following tests until a product that meets the predefined requirements was managed. Therefore, a test was previously carried out to see the feasibility of the development of these new products. Once these expectations were met, work was done to improve the formulation until an acceptable taste was found. When the flavour was achieved, the texture was worked on. Texture implies a challenge in the production of a meat product from vegetable proteins.

Figure 2. shows how the iterative process was developed until 4 final formulations were reached [

18].

2.3. Burger analogues production

Twenty-five different formulations were elaborated in the iterative process until the four final formulations were reached. A mixer grinder was used to make the burger (Robot Coupe, Mod. Blixer 6 V.V) and Petri dishes were used to give their characteristic shape, with an exact weight of 80 g per unit. The final formulations are shown in

Table 1. The samples were packed in air-filled trays using a thermosetting machine (Tecnotrip, Mod. EV-13). Once packaged, the samples were stored at 4°C until analysis.

2.4. Physicochemical quality of developed products

2.4.1. pH

The pH was measured with a digital puncture pH meter (Mod. PH25, XS instruments), previously calibrated at pH 7 and pH 4 following device instructions.

2.4.2. Colour

The colour parameters were evaluated using a colourimeter (Mod. CM-2002, Minolta CO) to determine C.I.E Lab using the coordinates L* (lightness), a* (red/green coordinates) and b* (yellow/blue coordinates). The colour of these products was measured in raw.

2.4.3. Moisture (H%)

The moisture was measured for each sample, for the analysis, according to the gravimetric method employing a thermobalance (Mod. DBS 60-3, KERN & Sohn GmbH ®).

2.4.4. Water activity (aw)

This parameter was evaluated for each burger analogue sample using automatic measuring equipment (Mod.CX-1, Decagon Devices, Inc., Pullman, WA, USA) using the protocol described in the user’s manual.

2.4.5. Acidity Index

The acidity index was determined according to COPANT, 1969 [

19]. To a 5 g of sample, 25 mL of neutralized ethanol were added and then homogenized with an Ultra-Turrax (IKA, Staufen, Germany). Afterwards, samples were centrifuged, filtrated and titrated with a solution of NaOH 0.1 N. The acidity index is expressed in % oleic acid/100 g.

2.4.6. Peroxide Index

The peroxide value was determined according to ISO 3960:2017 (Modified) [

20]. 10 g of the sample were weighed, and 25 mL of n-hexane were added. The sample was homogenized, centrifuged and filtrated. Into a 100 mL Erlenmeyer flask (Duran, Sabadell, Barcelona), pipette 5 mL of the supernatant, 7.5 mL glacial acetic acid (Carlo Ebra, Sabadell, Spain), 0.2 mL saturated KI (PanReac, Ottoweg, Germany). To improve the mixing of the reagents, it was stirred for 2 minutes. After this time, 25 mL distilled water was added and 1% starch (PanReac, Ottoweg, Germany) was used as an indicator. The sample was stained greyish and titrated with sodium thiosulphate (Na

2 S

2 O

3) with a concentration of 0,002 N. Peroxides values were expressed as meq O

2/Kg.

2.5. Microbiological quality of burger analogues

The study of microbial growth allowed the development of a spoilage model for the development of the new products, in addition to establishing their shelf-life. Total viable counts at 37 °C (TVC) were conducted according to ISO 4833-1:2013 [

21]. Furthermore, a count of moulds and yeasts (MY) was made following ISO 21527-1:2008 [

22]. For the enumeration of the

Enterobacteriaceae family bacteria (ET), the standard ISO 21528-2:2017 [

23] was followed. 10 g of each fresh burger was taken and placed in a sterile plastic bag with 90 ml of peptone water (0.1%). After 2 min in a stomacher blender (Mod. 1986/470, IUL Instruments, Spain), appropriate decimal dilutions were poured plated (1 ml) on the following media: Plate Count Agar (PCA) for the total viable count (37 °C for 48 h and 10 °C for 5 days respectively) and Violet Red Bile Glucose Agar (VRBG) for

Enterobacteriaceae (37 °C for 24 h). All microbial counts were converted to logarithms of colony-forming units per gram (log CFU/g).

2.6. Sensory study of burger analogues

The different sensory analyses carried out had two main purposes: first, to establish the general sensory profiles of the new products. Second, evaluate their acceptance by consumers. Samples for sensory analysis were cooked in a frying pan with olive oil for two minutes on each side. A core temperature of 75°C was reached. Samples were served to the participants at 45°C in equal parts (20 g) for the respective tests.

Quantitative descriptive analysis (QDA)

A trained panel of 10 assessors [

24,

25] was used according to the Quantitative Descriptive Analysis (QDA) method. The analytical sensory evaluation was developed according to the procedure of Gacula (1997) for the sensory characterization of burger analogues [

26]. Structured scales anchored at the extremes (0, attribute not present -10, attribute very present) were used for each of the specific sensory attributes highlighted in the penalty analyses (ISO 13299:2016) [

27]. The analyses were carried out using SENSESBIT® software using QR code access, which was generated for each test. For the selection of the sensory attributes to evaluate the hamburger analogues, the Flash profiling technique based on the free choice of attributes was used. [

28]. The selected descriptors were: homogeneity and colour intensity (similar to the beef burger) for visual assessment; vegetable aroma, cooked meat aroma, smoked aroma, spices aroma and rancid odour for olfative assessment; elasticity, firmness, fracturability and crunchiness (at first bite) hardness, succulence, cohesiveness, graininess, pastiness and gumminess (while chewing) for texture assessment; umami taste, salty taste, bitter taste, cooked meat taste, vegetable taste and aftertaste persistence for taste assessment [

28]. The sessions were held in the tasting room of the Pilot Plant of the Faculty of Veterinary. In these tastings, the burger analogues were characterized from the starting point of the experiment, according to UNE-EN-ISO 8586:2014 [

24].

2.7. Shelf-life Study for burger analogues developed

2.7.1. Shelf-life Design

A shelf-life study was developed considering the recommendations established in ISO 16779: 2015 [

29]. An experimental design was performed following a basic overall design with a statistical approach [

30]. A Drawn Simple Design (DSD) model was used to describe the evolution of the prototypes over time, under the same storage conditions (4°C). A total of 4 sampling points were performed on day 1, 3, 8 and 12. The study was carried out until typical sensory defects were detected in the product. A database was compiled with the results obtained for the physicochemical and microbiological parameters studied. On each sampling day, the same parameters used for characterisation were analysed: physicochemical, microbiological, and sensory analyses.

2.7.2. Shelf-life Model (Multivariate Method)

According to several authors [

17,

31] the shelf-life according to a multivariate criterion considers the totality of the physicochemical and microbiological analyses performed on the sample developed to estimate the shelf-life of the burger [

30]. These results were statistically analysed by Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to estimate the shelf-life according to multivariate criteria. Using the factor scores obtained in the first component (F1) on each of the sampling days, a scatter plot was later constructed where the cut-off points with the abscissae represented the ideal shelf-life of the product.

2.7.3. Spoilage descriptive model

This model was carried out with the results of the parameters analysed in order to understand how they acted during it is storage. For this purpose, a least squares regression statistical analysis (PLS) was supported. This allowed us to understand the relationships among variables (physicochemical, microbiological and sensory parameters) for the developed products.

2.8. Statistical analysis

The measurements of the analyses were carried out in triplicate. The results obtained from the different physicochemical, microbiological and sensory analyses accomplished for this work were analysed by descriptive and inferential statistics using Microsoft Excel with XLSTAT software (Addinsof ®, version 16). A univariate analysis was previously performed on the data set, with the calculation of maxima, minima, quartiles, means, modes and variances, represented graphically by box plots, scattergrams and histograms, to check the normality of the data and to detect non-parametric values. Bivariate comparisons were held by proving Pearson's correlation coefficients. An Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was then carried out to establish the differences between the different variables studied. For this purpose, a 95% confidence interval was considered, and significant differences were considered when p < 0.05. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used as an exploratory and graphical method for the shelf-life study. In the sensory characterisation of the developed products, an ANOVA was previously tested. A panel analysis was then performed to ensure the consistency of the judges' evaluations. Subsequently, product characterisation was analysed using the cosine squared method (Cos2) and corrected means were estimated.

3. Results

3.1. Iterative development process

The procedure followed to obtain the final formulations began with a study of the basic formulations used on the market to make burgers. From there, the feasibility of using raw materials such as seitan was studied. On the other hand, a gluten-free raw ingredient, in this case, soya, was chosen for the coeliac population. Product development was feasible and a burger was developed. In the first phase, small-scale experiments were conducted, demonstrating that it was feasible to produce a burger with alternative protein sources. Several authors confirmed that it was possible to develop a burger prototype not exclusively made of meat [

32]. The next point to work on was to correct the taste. The taste was modified and improved by using flavourings and spices, masking agents reminiscent of a traditional beef burger. The taste was satisfactorily achieved, and the use of insect flour added umami and cereal flavours. On the other hand, among the main challenges encountered when designing the formulation was the search for a meat-like texture. As some authors claim, it is a challenge to find a texture equal to that of a beef burger [

33]. Information about binders was found in the literature [

34]. Some binders were used to provide a consistent texture. Gellan gum, xanthan gum, guar gum and a mixture of sodium alginate with calcium chloride were tried but they provided an undesirable mouthfeel, which masked the specific flavours of the burgers. Finally, the only gel that did not mask the typical flavours was sodium alginate with calcium chloride, which provided a texture very similar to that of a beef burger. Though, in order to achieve a clean label, more appealing to the consumer, the use of natural ingredients was pursued in this case through the use of wheat flour, rice, oat, white corn and maize starch. Depending on the type of flour used, these provided a strong vegetable flavour, as in the case of chickpea flour, evocative of falafel. However, tests with oat flour were able to provide a very pleasant toasted taste. After 25 proofs, 4 final formulations for burger analogues were achieved: seitan + alginate (SEAL), seitan + oat (SEOA), soya + alginate (SOAL) and soya + oat (SOOA) (

Table 1).

3.2. Quality and safety of burger analogues

The burger analogues formulated with alginate obtained higher AI values (p < 0.001), compared to those made with oat. The above could be by the hydrolysis of acyl glycerides, mainly due to lipase enzyme activity. In the scientific literature, oat is studied for their antioxidant activity. Furthermore, in these samples with alginate, the peroxide index was significant (p < 0.001), corroborating the AI results. Alginate-based formulations for meat analogues making had been reported as highly vulnerable to oxidative lipids reactions [

34]. The pH, in general, was around 6.4 for most of the samples. The pH is at these values due to the slightly alkaline character of the ingredients used in the formulations. The values obtained agree with that obtained by De Marchi et al. (2021), which obtained a pH of 5.58 -7.9 for a burger of vegetable origin [

35]. According to Botella-Martínez et al. (2022), pH has a relevant effect on the final colour, as vegetable ingredients can change colour depending on the pH of the food [

36]. Water activity (a

w) did not show relevant differences between samples and characteristics of meat preparations, which makes it a product in which microorganisms could grow and proliferate, leading to alterations in the product. In terms of moisture, values between 49 and 60% were obtained, characteristic of the meat prepared. The colour was determined by the coordinates L*, a* and b*. The colour was characteristic of the burger analogues, mainly due to the difference in raw material. Seitan has a brownish colour, while soya tends to have a pale-yellow colour. Nevertheless, colouring agents were used to simulate the red colour of the meat. The measurements were carried out raw because after cooking, the colour changed to brownish due to Maillard reactions. The different values were obtained for the different coordinates. The luminosity (*L) in the treatments showed significant differences (

p < 0.001).

The SEAL sample had a lower luminosity compared to the other products. This may be because seitan in this case has a darker colouring than soya. The a* coordinate could differentiate the products according to the main raw material

(p > 0.01). Formulations with soya have a higher reddish colour compared to those formulated with seitan, which may be because the dye was more potent when introduced into a light colour matrix. For the b* coordinate, the SOOA formulation was the least yellow-coloured (

p > 0.05). The other samples obtained very similar results, as can be seen in

Table 2, indicating a yellower colour than the other burger analogues. In the study by De Marchi et al. (2021), the colour analysis for meat and vegetable burgers yielded very similar values to those found in this study; obtaining a value of L* between 42.36 - 48.61 and 39.87 - 48.90, for meat and vegetable-based burgers, respectively. It was also observed that the b* values were closer to the meat-based burger analogue of 13.57-15.88, while the* values were different. This could be because the samples analysed in the study by De Marchi et al. (2021) had a higher number of ingredients that could better simulate the real colour of meat preparation [

35].

One of the objectives of this study was to fortify burger analogues by using

T. molitor flour. In this sense, the developed products had on average a weight of 80g and were fortified with 5.8 g of insect flour which provided approximately 3,5% of high biological value protein, promoting an increase in both its quantity and quality. Because as seen in the literature the content of burgers would be in the range of 18.6-19.4, with this nutritional strategy it is expected to outperform commercial plant-based burgers [

35,

36].

3.4. Sensory study of new products

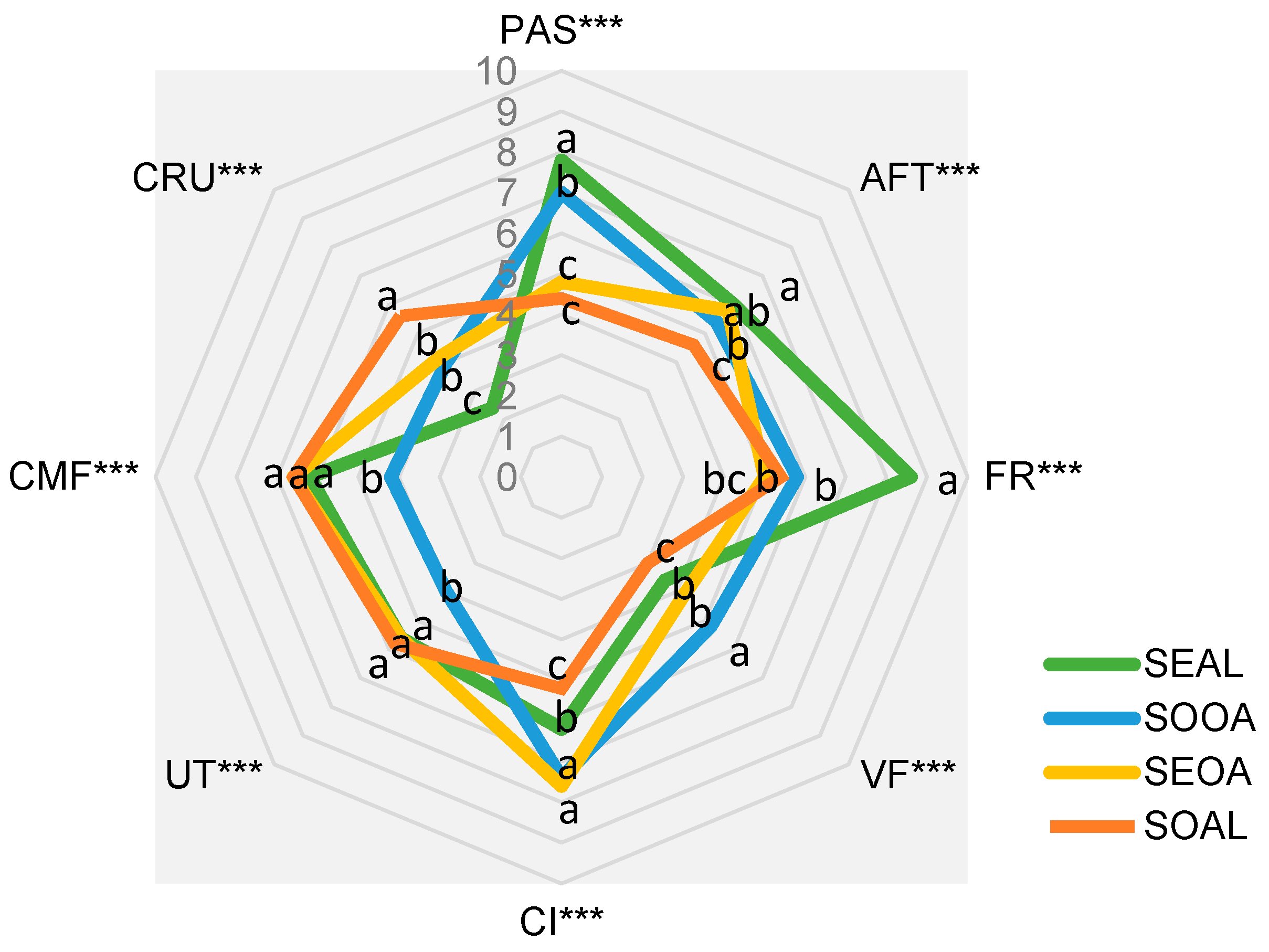

Sensory characterisation of the burger analogues

Sensory characterisation of the burger analogues was performed. This sensory analysis demonstrated the discriminatory power of each attribute, as can be seen in

Figure 3.

The following attributes stood out as highly significant (p < 0.001) and therefore with the highest discriminatory power: crunchiness, rancid odour, cooked meat aroma, colour intensity, fracturability, pastiness, vegetable flavour, aftertaste persistence and umami taste. This spider graph shows the initial time formulations with the eight most significant attributes for the formulations studied. The rancid odour was removed from the graph because it is considered a negative attribute in this case to characterise these products. The SEAL burger was characterised by the most pastiness and fracturability texture, the crunchiness in this formulation was less noticeable. This may be because the alginate together with the seitan resulted in a softer texture, not forming a good cohesion of the ingredients. In the taste dimension, the umami taste was like the other burgers. In relation to appearance, it was different from the others. This formulation had the longest persistence of aftertaste. The SOOA formulation remained near to the SEAL formulation in texture, as it was perceived as pasty and fracturable to a lesser extent, but these traits characterised it. On the other hand, it was the one with the most vegetable flavour. As the cooked meat flavour decreased, this may be because soya and oat have a prominent vegetal aroma, which covered the added flavours. It presented itself as the burger with the highest colour intensity. The umami taste was absent, which is reflected in the lack of persistence in the aftertaste. The crunchiness was perceived to be intermediate between the designed formulations. The SEOA burger maintained a texture closer to that of a burger, as it was not perceived as too pasty and was not so fracturable. In appearance, it stood out as the one with the highest colour intensity as well as its oat counterpart, this may be because the oat-based formulations were more toasted during cooking. In the flavour and aroma dimension, it was perceived with a pronounced umami flavour, cooked meat flavour and a minor level of vegetable flavour. In addition, it retained an aftertaste. The crunchy character was perceived the same as in the oat burger. Oat, therefore, characterised the crispiness and colour equally in the formulations. Finally, the SOAL was the least pasty and fracturable burger of all the formulations and stood out as the crunchiest of all. As far as flavour is concerned, it raised out for it is cooked meat flavour, while the vegetable flavour was not so noticeable. The colour was the least intense, which may be because the soya is not roasted as much during cooking. The umami flavour was prominent, but the aftertaste was not as persistent.

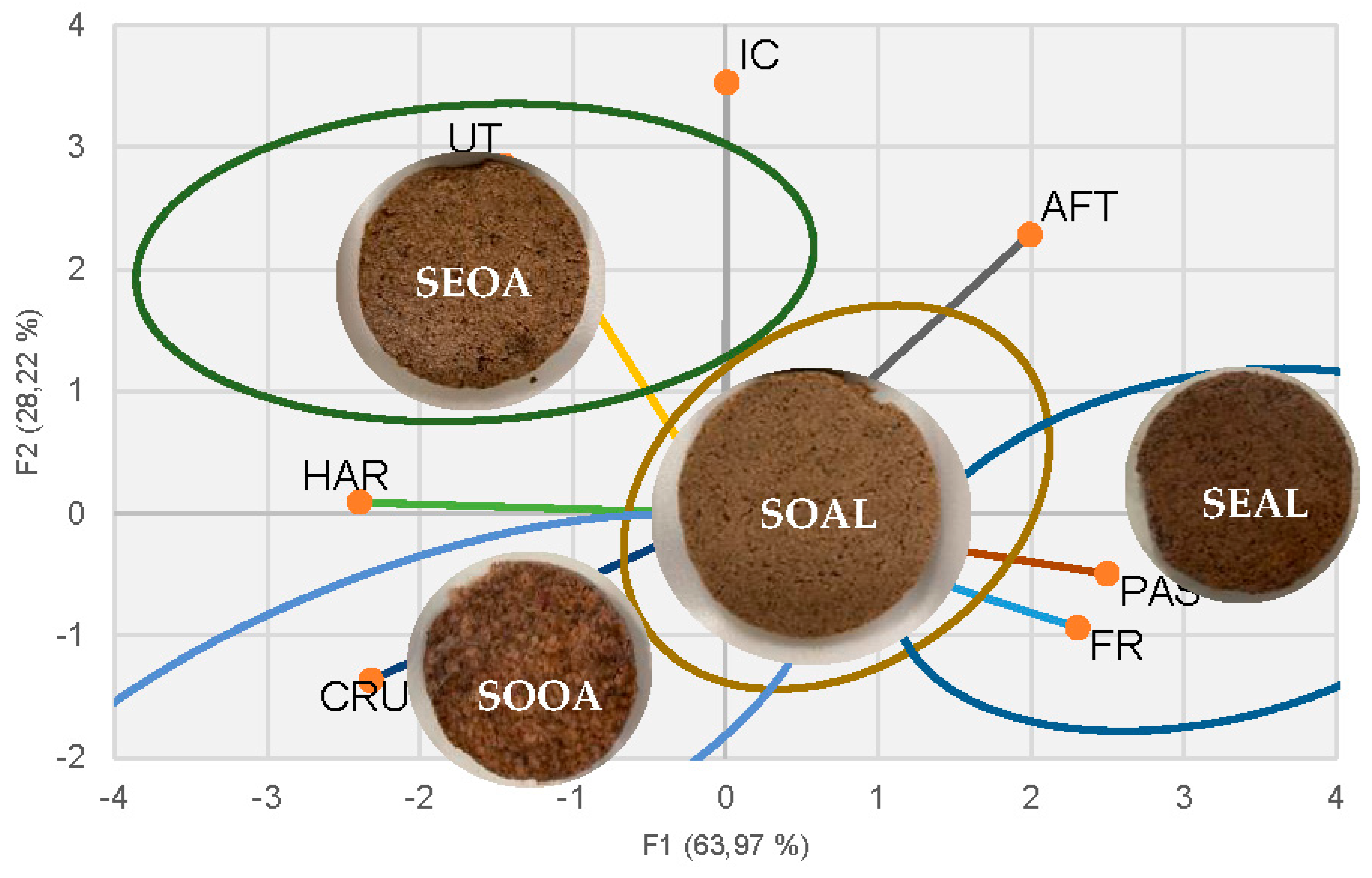

Ultimately,

Figure 4 shows which highlight of each formulation. The SEOA burger showed out for it is umami taste, toughness and colour intensity, and was near to the SOOA burger in terms of crunchiness and toughness. The SEAL burger was perceived to be more pasty and fracturable. And as a more neutral evaluation without being characterised by any attribute in general, the SOAL burger was found to be more neutral. Burgers with oat were found to be nearer to each other than those formulated with alginate, nevertheless of the raw material used. Oat is an ingredient that is providing more hardness and gives a more intense colour to the food.

The burgers with alginate showed differences between the burgers formulated with oat. In the study of Caparrós et al. (2016), where a sensory analysis was carried out for four different types of burgers, including a hybrid of meat with insect flour and another of insect flours with lentils [

37] it was observed that consumers, in both products, were able to identify the remains of the insect exoskeleton, which in most cases was reported as undesirable (defect) [

38]. Similarly, in the present investigation, this ingredient (insect flour) was responsible for the crunchiness perceived by the trained sensory evaluators. It should be noted, however, that the granulometry of the insect flour used was very fine, making it visually very difficult to detect in the final products, although, as mentioned, for example, with SOOA, it was able to produce a considerable sensory stimulus. In the end, the sensory profile of the developed analogues showed that they could represent a feasible alternative to increase the market offer of these kinds of products.

3.3. Shelf-life study

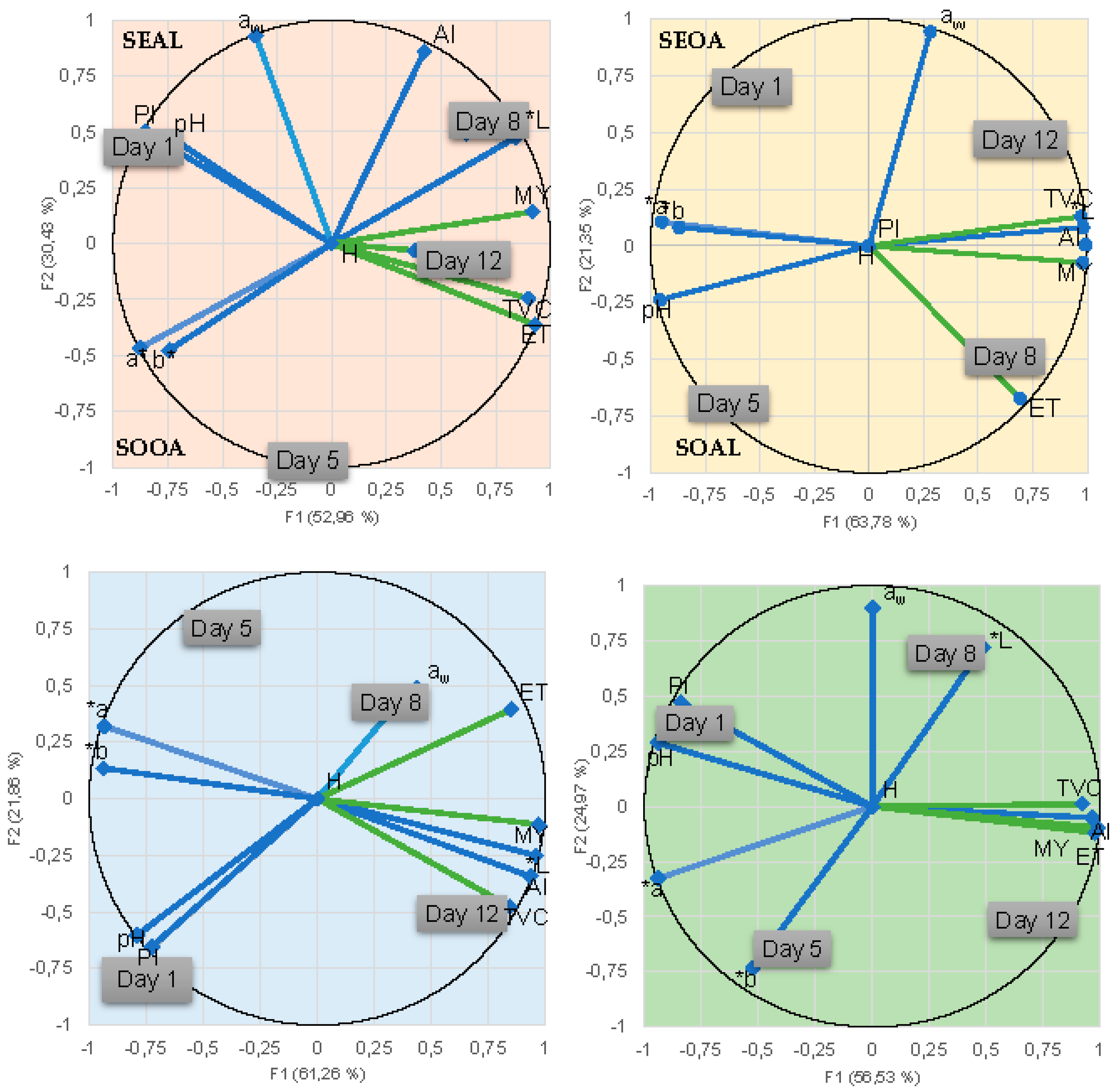

The shelf-life was studied through the following PCA graphics, where the physicochemical and microbiological parameters are plotted over time (

Figure 5).

As can be seen in a general view, nothing of the PCA showed a trend of linearity over time, and all of them were different from each other. This means that the days follow one after the other in chronological order. In the SEAL sample, the variability of the experiment was found to be 83.39% for the two components. Day 1 was characterised by the physicochemical parameters of PI and pH. Over time, day 5 was distinguished by the colour coordinates (a* and b*), experiencing a higher microbial load. Day 8 was described by AI and L* approached the final day (day 12) with the growth of microorganisms (TVC, MY and especially ET, with a high ET contribution in the component). However, the sample formulated with seitan and oat (SEOA) behaved differently. The variability of the experiment was found to be 85.13% in the two components. The initial days were mainly characterised by colour coordinates and pH. Over time, on day 8, microbial growth was again experienced until the end of it is shelf-life, which was related to water activity. The physicochemical parameters such as acid value and lightness were described with the microbial growth, which is related to the higher content of free acids that determine the rancidity reactions. In this formulation, the peroxide value and moisture content were found to be neutral. The PI values were very low, which may be because some of the ingredients have antioxidant capacity. In the SOOA sample, the variability of the two components was 83.13% and again there was a relationship between the initial day with pH and PI. The colour parameters (a* & b*) characterized Day 5, while Day 8 was defined by water activity, microbial growth and AI until the end of shelf-life. For the SOAL sample, the variability of the experiment was described as 81.5% in the two components. Day 1 was again described by PI and pH, as is the case for the other alginate formulation, which, as shown in

Table 2. Day 5 is described by the coordinates of more weight, a* & b*, in this case, due to a more yellowish colouration. Day 8 was defined by water activity and luminescence. At life end, AI-related microbial growth began to be experienced.

Shelf-life studyModel (Multivariate Method)

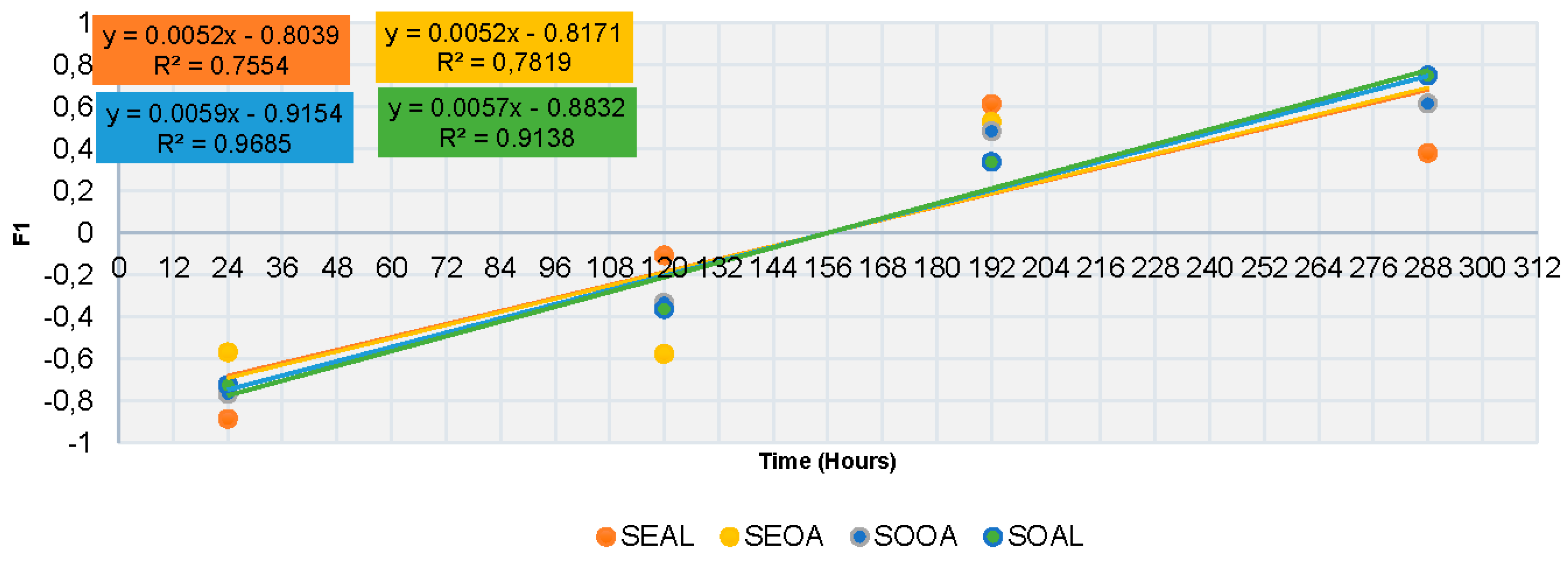

Figure 6 shows the shelf-life using the multivariate approach. It was estimated by plotting the scatter plots from the factorial scores of the first component (F1). These were obtained from the PCA graphics shown in

Figure 5 based on the physicochemical and microbiological parameters evaluated. The intersection of the curve with the abscissa should be understood as the time that the product is kept in suitable conditions for consumption. These results estimated that the expiry date of all developed products was set at 156 hours, i.e., 7 days. The samples showed no difference. This could be due to the similarities among formulations.

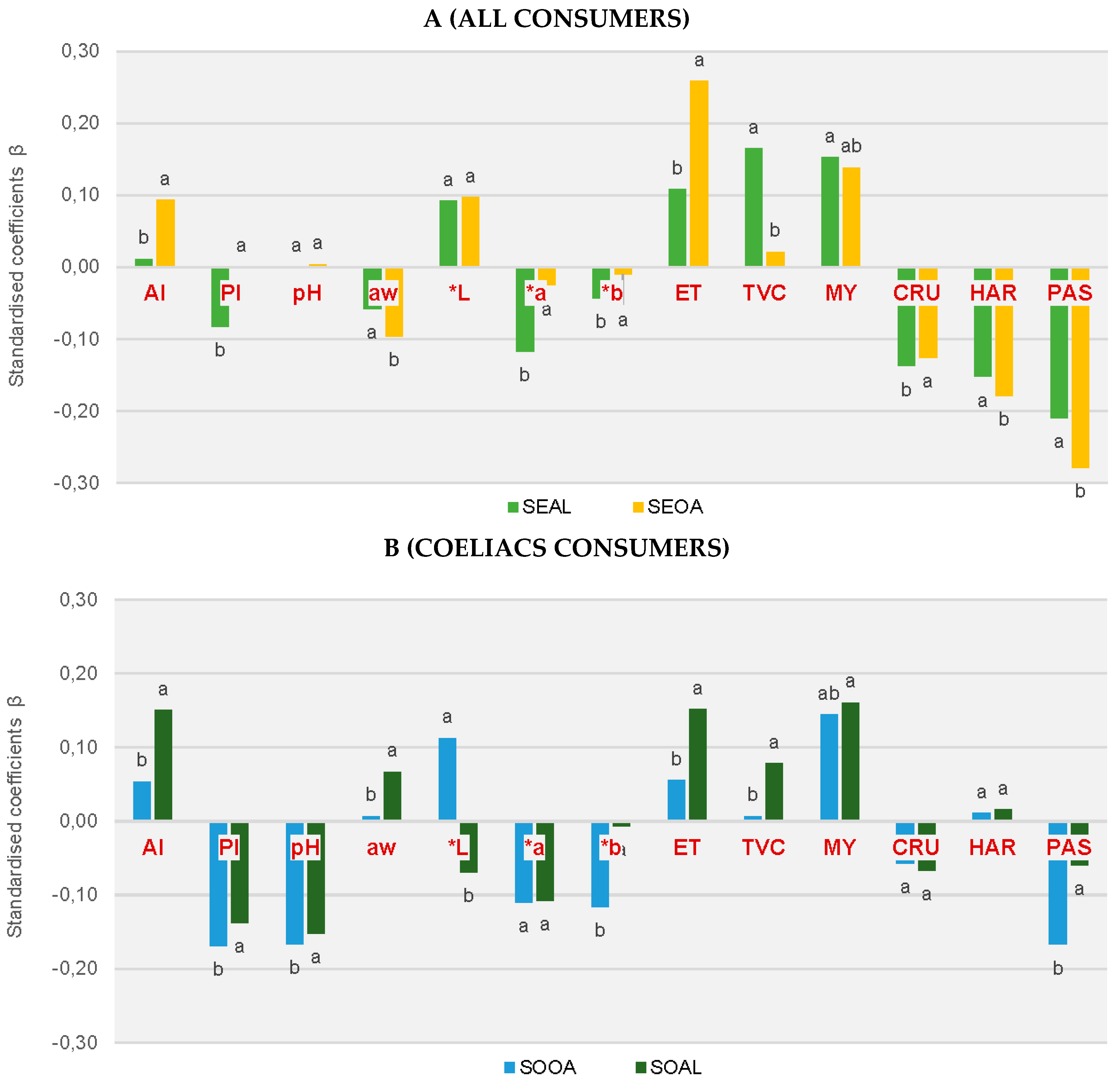

3.5. Spoilage descriptive model

Partial least squares (PLS) regression was performed to model the multivariate data collected for the study to establish relationships between the parameters evaluated for the burger analogues. All studied variables (physicochemical, microbiological, and sensory freshness index) were considered to carry out a specific methodology indicated by Calanche et al. (2020) [

39]. The PLS provided a time-dependent spoilage model as shown in

Figure 7. In the initial time, a higher crunchiness was observed in the oat-based products. Over time, a change in attributes was experienced, with defects prevailing and loss of hardness being maximised. This may be due to the loss of water-holding capacity of the protein, due to degradation causing bacterial proliferation.

A comparison of burger formulations could be made according to consumption, for all consumers and for the coeliac population. The treatments containing seitan in their formulation (for all consumers) showed a time-dependent relationship with microbial growth, in this case, influenced to a greater extent by the growth of enterobacteria. Physic-chemical parameters such as acid index and brightness were the key aspects of this. Sensory texture attributes (crunchiness, hardness and pastiness) were not directly related to spoilage. Significant differences were found between the binders chosen for the formulation, indicating that brightness was the only parameter constant over time in food spoilage. Degrading of the SEAL treatment was described by lightness (L*) and to a greater extent by the growth of aerobic mesophiles and moulds and yeasts. In treatments incorporating oat, spoilage was conditioned by the acidity index, brightness and the growth of enterobacteria. In the case of formulations designed with soya (for those intolerants to gluten), they showed high values of β coefficients that demonstrated a relevant impact on the deterioration model obtained. In this case microbial growth was linked to the Enterobacteriaceae family and moulds and yeasts. To a lesser extent, the sensory attribute of hardness was affected by storage time, indicative of spoilage in both formulations. Acid index values and water activity were the main factors indicating deterioration in the soybean formulations. pH and PI were not related to deterioration in these samples. The binders used showed differences between them. In the case of alginate, there was a very high AI value related to aw and growth of enterobacteria and moulds and yeasts. While those incorporating oats in their formulation stood out for brightness as a spoilage factor and the growth of moulds and yeast.

Finally, the spoilage of the burger was mainly conditioned by the proliferation of microorganisms and was characterised by AI and luminosity (L*) on the surface of the samples. In terms of sensory attributes, most of the treatments developed did not show considerable changes, however, it could be seen that textural properties were a key aspect of this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.A., and J.C.; Data curation, P.A., and J.C.; Formal analysis, P.A., A.H., P.M. and J.C.; Funding acquisition, J.A.B. and J.C.; Investigation, P.A., A.H., P.M. and J.C.; Methodology, P.A., A.H., and J.C.; Project administration, J.A.B. and J.C.; Resources, J.A.B.; Software, P.A., and J.C.; Supervision, J.A.B. and J.C.; Validation, J.C.; Visualization, J.C.; Writing—original draft, P.A., and A.H.; Writing—review and editing, P.A., A.H., J.A.B. and J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.