1. Introduction

Canola is one of the major Australian broadacre crops, producing 7.5 million tonnes in 2023-24 [

1]. Canola meal constitutes up to half of the total canola seed biomass (

w/w) and is the major waste product of oil production [

2]. Although it is the second most used animal feedstock after soybean meal [

2], its use as a feedstock is limited due to glucosinolates, thiocyanates, isothiocyanates and sinapins [

2]. Generally, the pre-conditioning of seeds at 80 - 90°C [

3], or in some case 135°C [

2] minimises the myrosinase activity. The enzyme catalyses the otherwise non-reactive glucosinolates to more toxic intermediates such as thiocyanates, isothiocyanates and nitriles, among others [

2]. This combination of sinapins (1%), low-level thio/isothio-cyanates and low energy density of non-dehulled canola meal, compared to soybean meal have been shown to compromise growth by up to 5.7% in non-ruminant animals such as poultry [

4] and digestibility in swine [

5].

Thermal treatments have shown to be impactful for canola meal valorisation [

2,

3,

6]. However, these treatments cause severe degradation of amino acids, bioactives and thermolabile metabolites in the canola meal [

7].

Microbial bioprocessing is a good method to address these deficiencies and achieve a biotransformation rather than degradation [

8]. Recent studies conducted with black soldier fly (BSF) and other potential candidates, have indicated the role of insects and their gut microbiome for biomass conversion [

9,

10,

11]. It is known that insects such as aphids [

12] and various lepidopteran pests such as Helicoverpa are resistant to the toxicity of glucosinolates, cyanates and sinapins [

13,

14,

15]. However, due to their mode of feeding, aphids tend to avoid ingesting significant amounts of the toxins [

16,

17] compared to chewing herbivores such as lepidopterans. Therefore, the gut microbiome of the latter may play an important role in countering the brassica glucosinolate and sinapins toxicity. While this property has been shown by multiple studies when considering these herbivores as pests on the brassica plants [

15,

17,

18,

19,

20], its application in commercial biomass transformation is limited.

In this context, we conducted a comparative study of cabbage looper, Heliothis moth and Cabbage White larvae gut microbiome towards canola meal biomass transformation. While most studies above relied on transcriptomic prediction in their studies, we utilized liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) assisted metabolomics to assess the functional aspects of these bioconversions. These included the glucosinolate depletion, coupled by an increase in short-chain fatty acids (SCFA). The metabolomics assessment also provided the insights of the mechanism of isothiocyanate, thiocyanate and sinapin metabolism, and key pathways involved in this bioconversion.

2. Results

2.1. Quality Control Analysis

The metabolomics analysis indicated a presence of ca. 4,301 metabolic features across both negative and positive polarities of mass spectral scans. Post-filtration data indicated the presence of 1,112 metabolites, of which one-way ANOVA analysis identified 658 as statistically significant (False Discovery Rate (FDR) adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05) metabolites. The relative standard deviation for internal standards 13C4-Succinic acid and 13C-Phenylalanine was observed at 12.73 and 11.19%, respectively. The percent-RSD for QC metabolites is presented in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Quality control metabolites variation.

Table 1.

Quality control metabolites variation.

| Metabolite name |

RSD (%) |

| Pyruvic acid |

15.19 |

| Serine |

31.80 |

| Maleic acid |

16.79 |

| Succinic acid |

10.75 |

| Asparagine |

13.74 |

| Salicylic acid |

34.92 |

| L-Citrulline |

17.17 |

| D-Glucose |

15.69 |

| Citric acid |

15.11 |

| Tryptophan |

17.19 |

2.2. Microbial Activity: SCFA Production and Glucosinolate Depletion

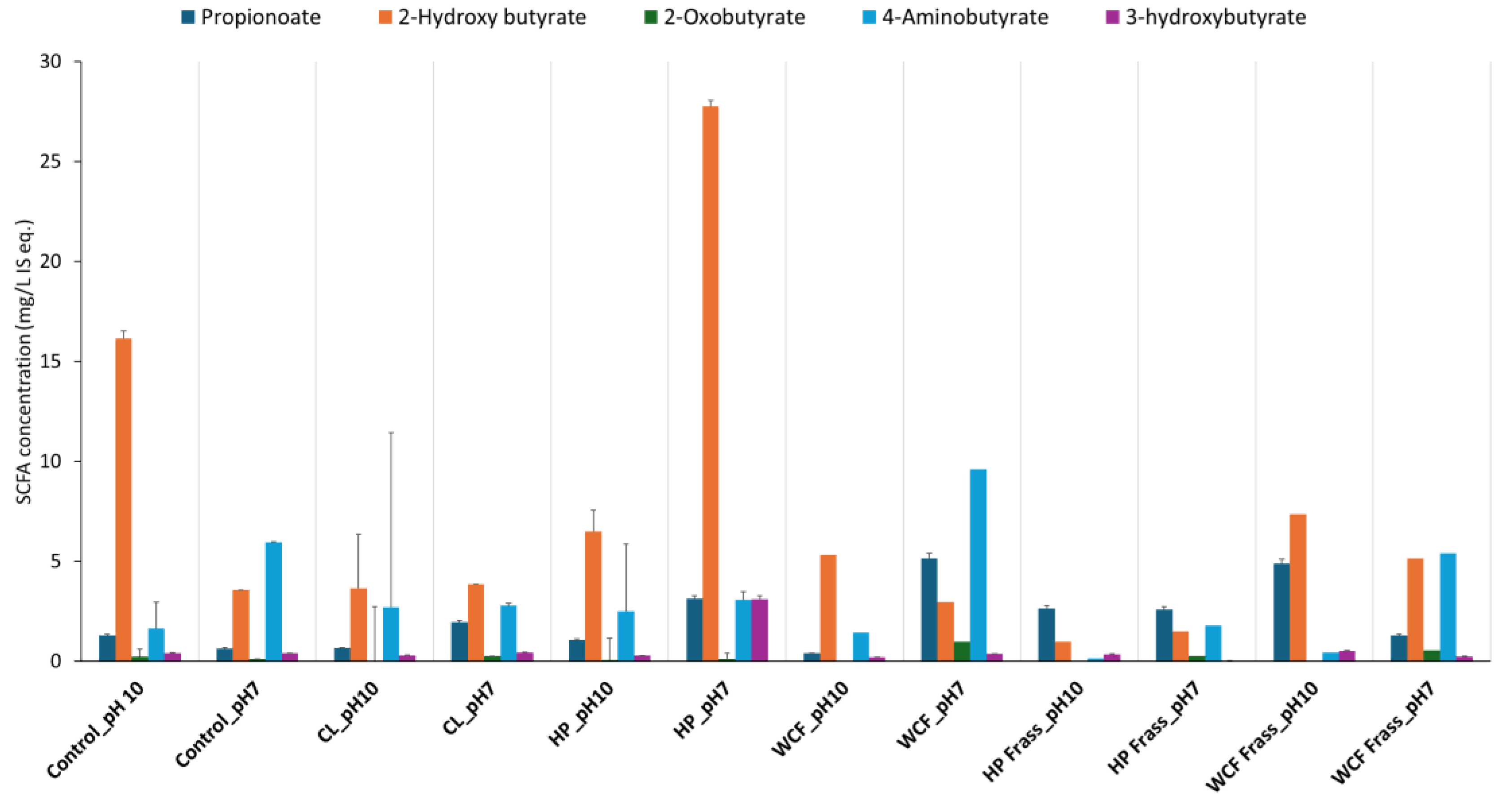

Besides the broader metabolic activity, the efficiency of canola meal biotransformation by insect microbiome was assessed via short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, and the depletion of antinutrients such as glucosinolates and sinapic acid derivatives.

The production of SCFAs and branched-SCFAs (Containing 6 or less carbons) are considered a good marker for the gut microbiome activity [

21,

22]. They are produced by the gut bacteria during the anaerobic fermentation of non-digestible carbohydrates and resistant starch. Furthermore, they modulate the gut microbiome against numerous stresses that gut environment is exposed to [

23].

The data analysis indicated a presence of 6 SCFAs/ branched-SCFAs across all the samples. Overall observations indicated that the fermented samples at pH 7 generated higher levels of SCFAs compared to pH 10

(Figure 1).

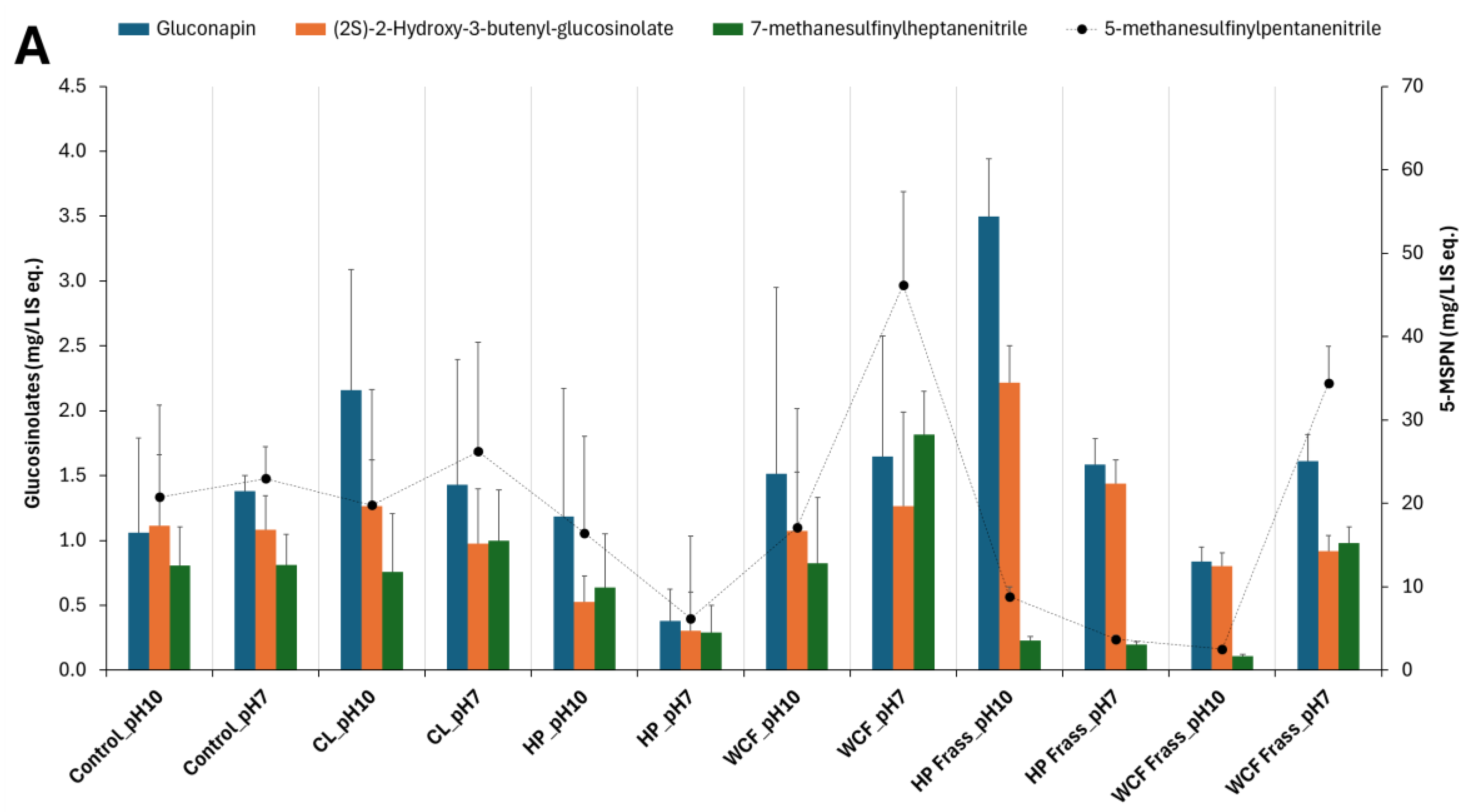

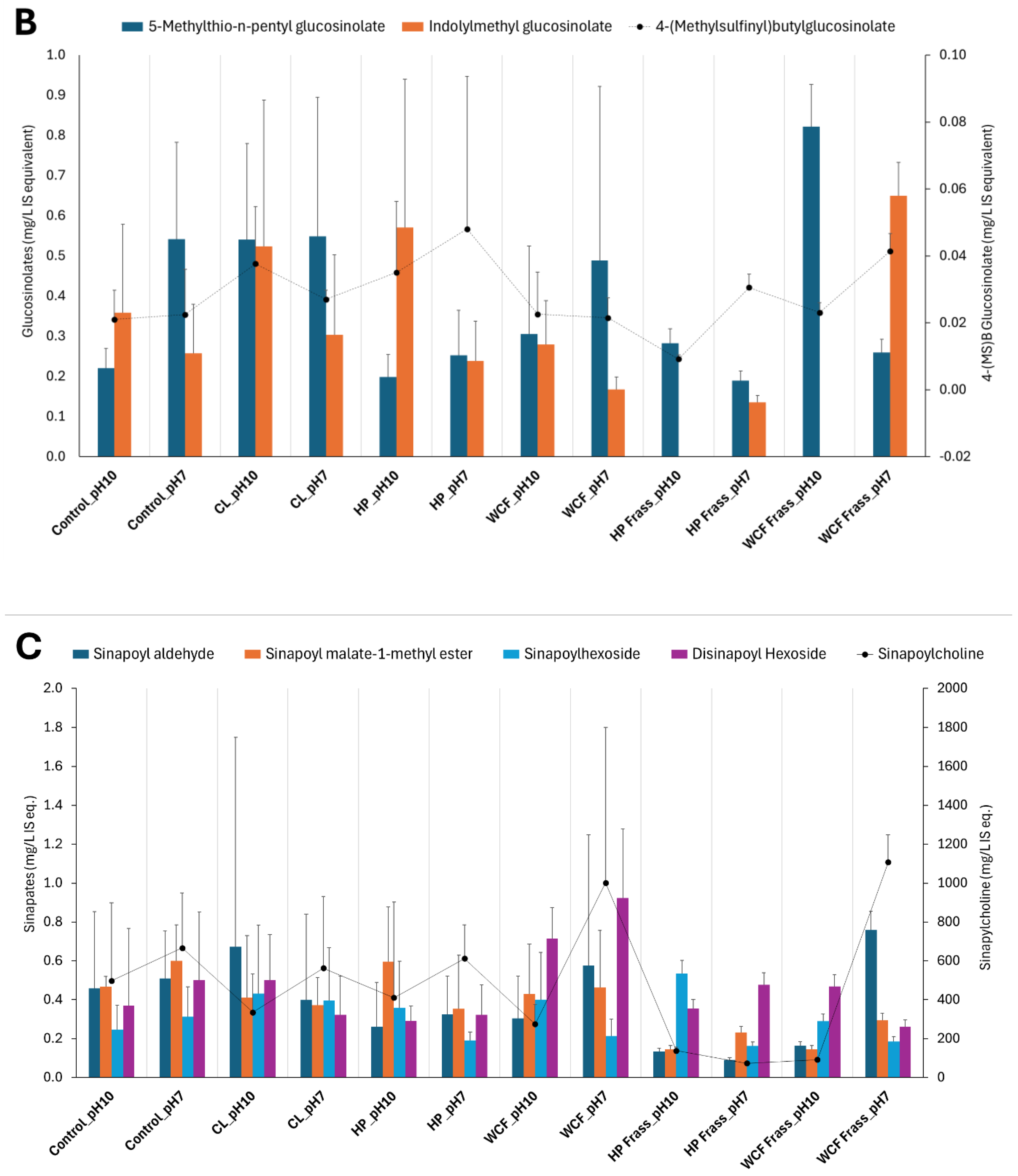

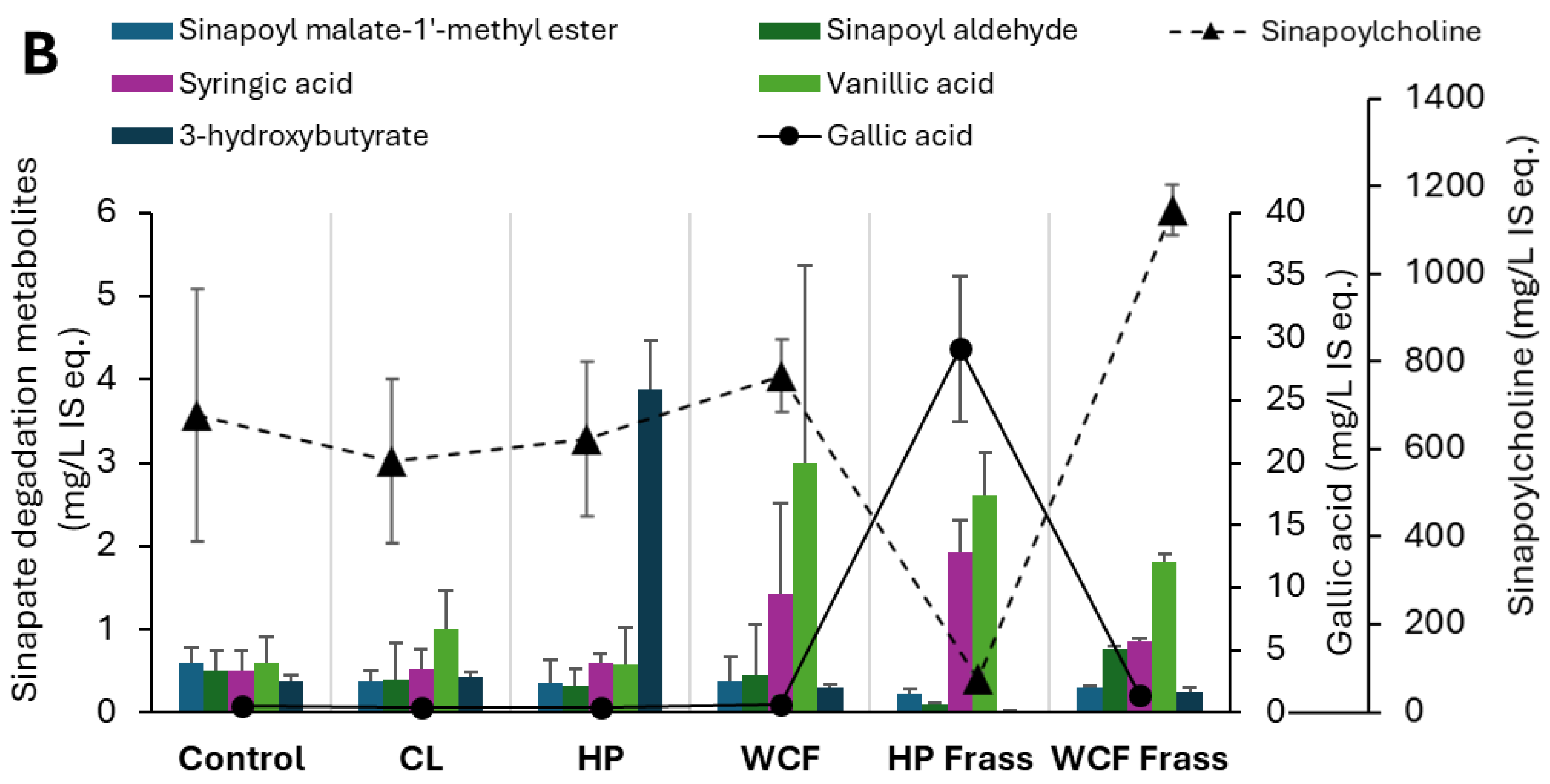

Similar to the SCFA production, pH7 was observed to be create a greater depletion of glucosinolates, sinapins and their derivatives. Particularly, the frass fermentation resulted in higher degradation compared to the gut content fermentation (

Figure 2).

It was also noted that the Helicoverpa microbiome fermentation of canola meal by both gut and frass, not only showed relatively more elevated SCFAs and branched-SCFAs, but also resulted in a greater depletion of glucosinolates, sinapins and their derivatives. Particularly, glucosinolates such as gluconapin (3.6-fold,

Figure 2A) and nitriles (2.7 – 3.7-fold) showed a considerable depletion in HP gut ferment at pH 7. Similarly, HP Frass ferment at pH 7 showed almost 2-fold depletion of glucobracissin (Indolylmethyl glucosinolate,

Figure 2B), and sinapates such as sinapylcholine (9-fold,

Figure 2C) and sinapoyl aldehyde (>5-fold), with respect to the control. The only exception was sinapoyl choline, which showed a greater depletion during the WCF frass fermentation (

Figure 2C).

2.3. pH Differences Showed No Statistically Significant Metabolism Difference

The samples were fermented at pH7 and pH 10 to assess if there was a differential expression of metabolic pathways at those values. Particularly, pH 10 was selected to mimic the natural conditions of sections of the larval gut, as it has been shown previously that the gut region of lepidopteran larvae can get very alkaline (pH 8 – 12), although the frass tends to be slightly acidic (pH 4 – 7) [

24]. It has also been suggested that the high alkaline pH promotes the degradation of complex compounds such as tannins in larval midgut [

13]. Interestingly, it has been shown in the study conducted on waste activated sludge, that a pre-treatment of the sludge by maintaining it at pH 10 for some time before fermentation, increases the biodegradation and methane production [

25].

The assessment of control samples in the current study indicated that almost none of the central carbon metabolites were altered in a statistically significant manner between neutral and alkaline pH values. Of the 49 significant metabolites (FDR adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05) that were observed to be statistically different between pH 7 and pH 10, most consisted of secondary metabolites such as polyphenols

(Supplementary

Figure 1, Supplementary Table 1), which were released due to a possible minor degradation caused by NH

4OH at pasteurisation temperature of 72°C. The impact of alkaline treatment at elevated temperatures towards polyphenol release from grape pomace on biomass has been shown previously [

26]. However, in the current study, the initial alkalinity was not observed to create significantly different metabolic profile, compared to pH 7 (

Figure 3). Also, it was seen that at the end of the fermentation, all the test samples had pH range of 4.9 – 7.3, indicating considerable acidification. This could be the key reason that the differences were not statistically significant between pH 7 and pH 10 ferments.

2.4. Metabolic Transformation During the Canola Meal Fermentation

The behaviour of 658 statistically significant metabolites was assessed with the PCA and PLS-DA for a better discrimination (Components = 8, Cross validation = 5-fold CV, 95% confidence interval) (Supplementary

Figure 2). The prediction accuracy measured with 100 permutations for separation distance indicated the model to be statistically significant (PLS-DA empirical p-value < 0.01; PermANOVA F-value = 0.5919, p-value = 0.001).

The data was subjected to Pathway analysis toolbox of Metaboanalyst 5.0, against Bombyx mori species metabolomic reference. The analysis indicated that 45 metabolic pathways were statistically significant (FDR adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05) (Supplementary Table 2), with top 15 (Impact ≥ 0.4) showed in Table 1. As glucosinolate degradation and SCFA production was primarily observed in pH 7 ferments, the behavioural pattern of the statistically significant metabolites from the key pathways (Table 2) were assessed against pH 7 ferments. Primarily two types of metabolisms, i.e., sulphur and amine metabolisms were predominantly seen.

Table 1.

Key pathways amongst the observed impactful pathways (FDR adj. p-value ≤ 0.05) during the canola meal fermentation as analysed by the Pathway analysis toolbox of Metaboanalyst 6.0.

Table 1.

Key pathways amongst the observed impactful pathways (FDR adj. p-value ≤ 0.05) during the canola meal fermentation as analysed by the Pathway analysis toolbox of Metaboanalyst 6.0.

| Metabolic pathway |

Hits/Total Compounds |

FDR |

Impact |

| Tyrosine metabolism |

10/ 29 |

2.77e-10

|

0.67 |

| Pentose phosphate pathway |

10/ 24 |

1.09e-08

|

0.40 |

| Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism |

14/ 21 |

3.33e-08

|

0.98 |

| Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism |

9/ 30 |

9.77e-08

|

0.73 |

| Glutathione metabolism |

8/ 26 |

2.21e-07

|

0.49 |

| Ascorbate and aldarate metabolism |

2/ 9 |

1.47e-06

|

0.52 |

| Citrate cycle (TCA cycle) |

8/ 20 |

2.72e-06

|

0.47 |

| Tryptophan metabolism |

8/ 29 |

4.34e-06

|

0.53 |

| Arginine biosynthesis |

9/ 13 |

0.0003 |

0.80 |

| Phenylalanine metabolism |

6/ 8 |

0.0004 |

0.74 |

| Histidine metabolism |

4/ 9 |

0.0028 |

0.4 |

| One carbon pool by folate |

9/ 23 |

0.0028 |

0.44 |

| Vitamin B6 metabolism |

3/ 8 |

0.0045 |

0.50 |

| Cysteine and methionine metabolism |

11/ 34 |

0.0048 |

0.48 |

| Riboflavin metabolism |

1/ 4 |

0.0129 |

0.5 |

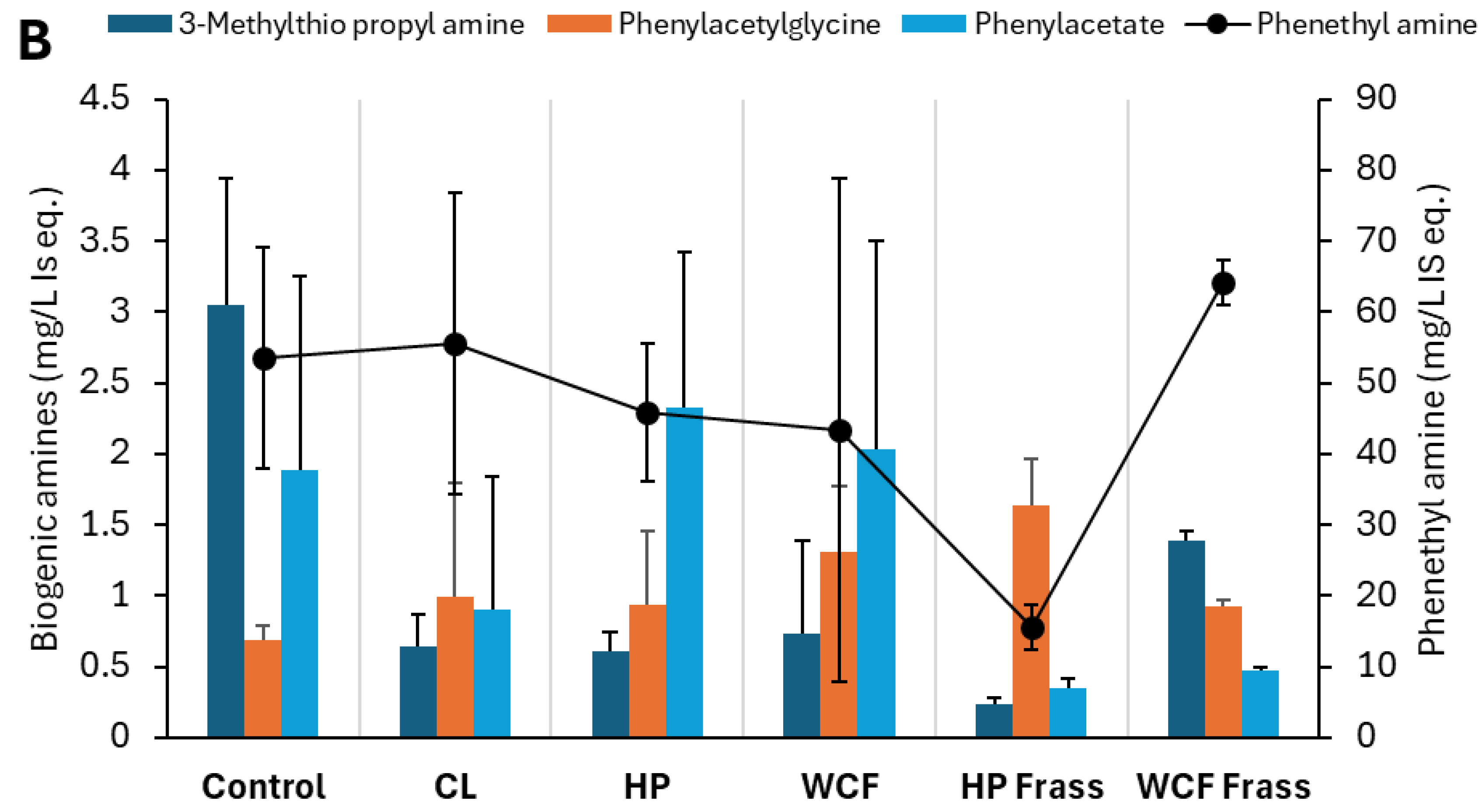

2.5. Aromatic Glucosinolate Degradation Results in Nicotinate, SCFA Biosynthesis, and Mercapturic Acid Pathway Led Biogenic Amines Synthesis

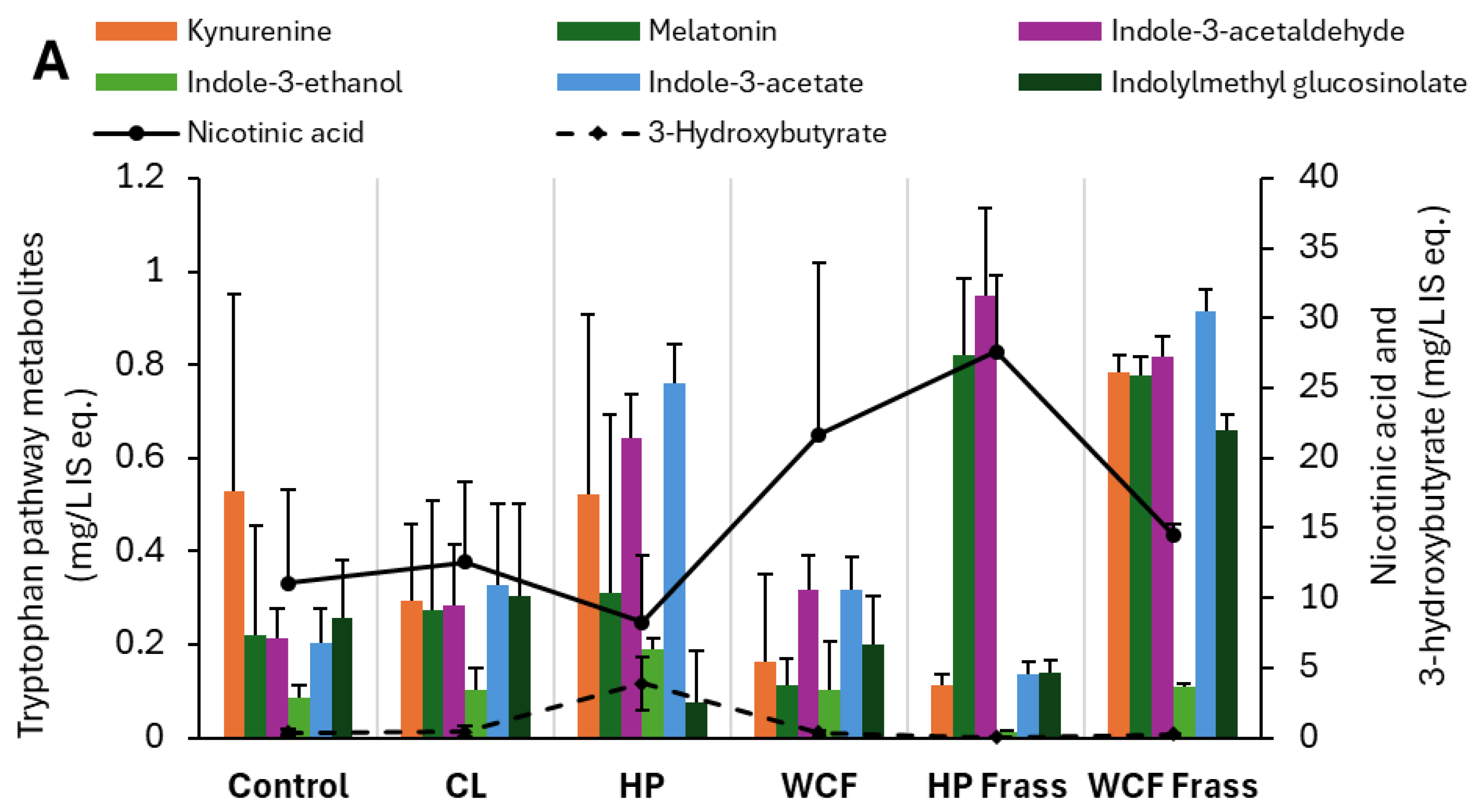

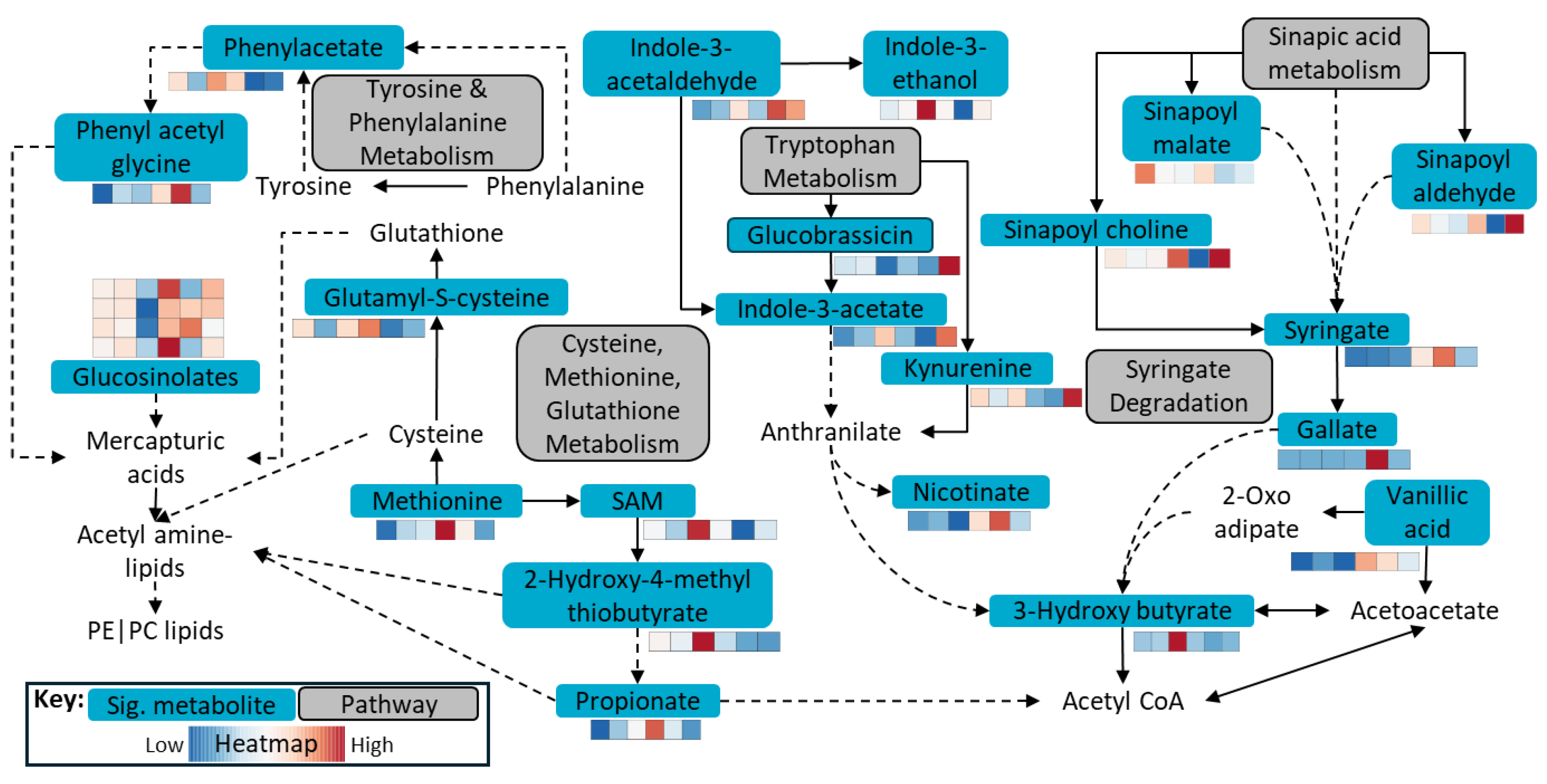

In the tryptophan metabolism, glucobracissin (indolylmethyl glucosinolate) degradation was observed to happen through indole intermediates. In Helicoverpa gut ferment, indole-3-acetaldehyde, indole-3-ethanol and indole-3-acetate were elevated. On the other hand, melatonin and indole-3-acetaldehyde showed elevation in Helicoverpa frass ferment. However, in the gut ferment, an increased 3-hydroxy butyrate indicated a likely metabolism of indoles to pyruvate metabolism via an acetyl-CoA intermediate. While, in the frass ferment, these intermediates appeared to be diverted to nicotinic acid metabolism, as evidenced from a considerable increase of nicotinic acid

(Figure 3A).

Biogenic amines such as methylthio propyl amine play an important role in the glucosinolate catabolism [

29]. However, the fate of these amines is not widely discussed. The mercapturic acid pathway has been discussed within human and animal models in relation to xenobiotic metabolism [

29,

30], but to a limited degree from a glucosinolate degradation perspective. In the current study, microbial metabolism likely drove the mercapturic acid pathway to deaminate the biogenic amines through methionine, and cysteine and glutathione metabolism pathways (Refer

Section 2.6, Figure 4A).

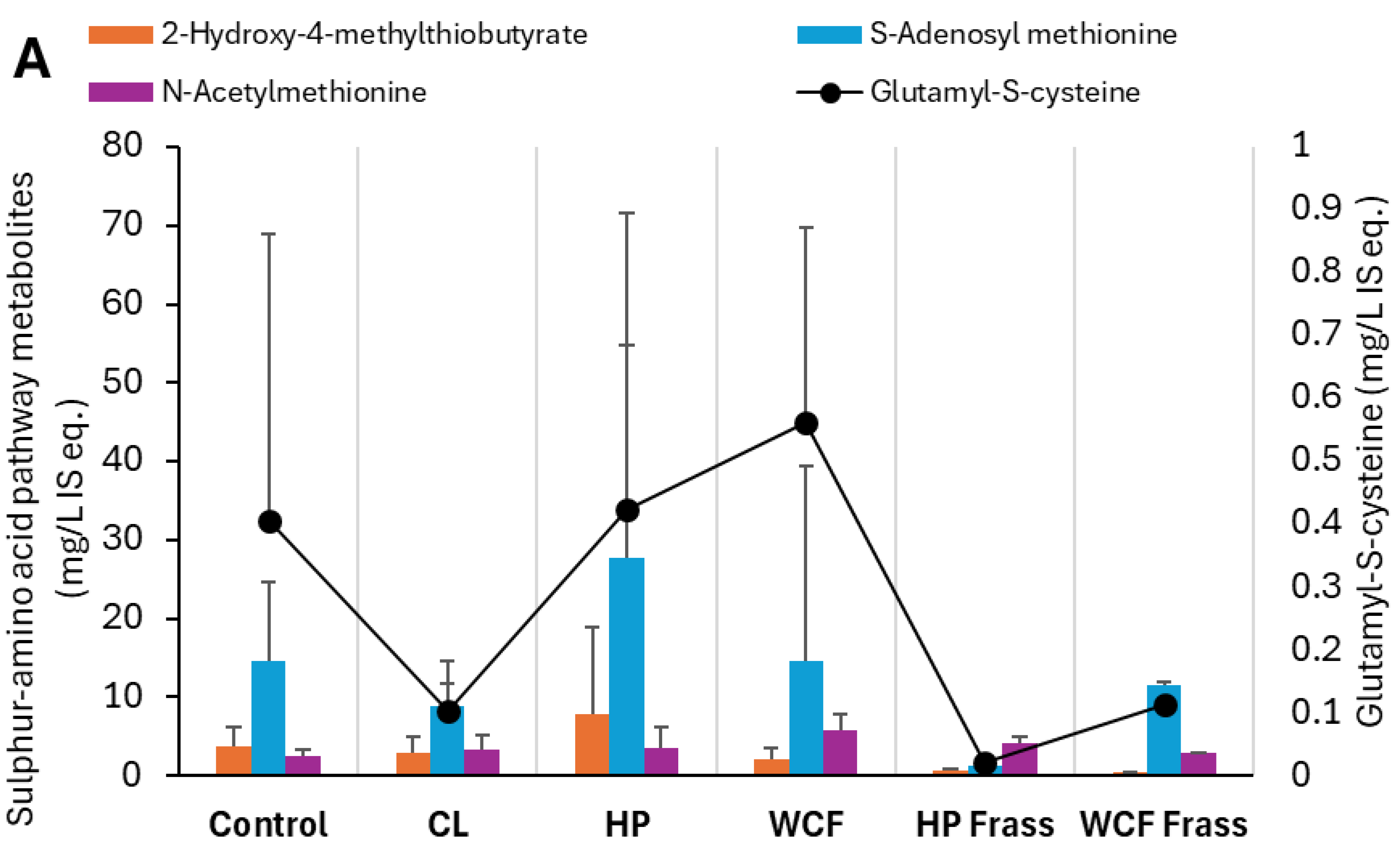

2.6. Gut Microbe-Driven Metabolism Plays a Key Role in Oxidative Stress Handling During Glucosinolate and Sinapate Degradation

Besides myrosinase, the enzymes such as isothicyanate hydrolases directly produce amines, while glutathione S-transferase activities first produce ITC-γ-glutamylcysteine and other intermediates (

Figure 4A), and biogenic amines (

Figure 4B) [

31]. Elevated S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) and γ-glutamyl-S-cysteine indicated amine salvaging through methionine metabolism, leading to glutathione synthesis via intermediate (

Figure 4A). This was particularly observed in the HP gut where both SAM and 2-hydroxy-4-methylthiobutyrate (HMTB) elevations indicated methionine recovery, tight regulation of sulphur and methyl balance under oxidative stress by the gut microbes.

3. Discussion

We used high-throughput metabolomics to assess the biochemical activities of gut and frass microbiomes during canola meal fermentation.

Helicoverpa zea and Cabbage white (WCF) larvae feeding on BT-cotton and cabbage, respectively have shown the enriched gut microbiota for modulation of their environment to counter biological and environmental stresses [

14,

32,

33]. The recent 16S rRNA-based amplicon study of the rapeseed pest, cabbage stem flea beetle [

15] indicated the importance of microbiome members such as

Pantoea spp. towards enabling the isothiocyanate degradation. The current study showed that the gut microbiome of brassica herbivore insects play an important role in the biomass degradation of canola meal. Particularly, it played a key role in acidification of all tested ferments, as reported previously [

32] during the glucosinolate and sinapate transformation. Myrosinase induced metabolism of glucosinolates in the plant cell is well known, resulting into production of indoles, isothiocyanates (ITC), epithinitriles and nitriles [

34,

35,

36]. However, the fate of these products especially in herbivore larval gut, is relatively less known.

Xenobiotic degradation and metabolism was one of the key microbially driven pathways in WCF larvae [

33]. On the other hand, metabolism of carbohydrates, lipids and 5-hydroxytryptamine were key metabolic pathways in

Helicoverapa larval gut [

37] with non-glucosinolate feed. However, the current study indicated that when the microbiome was applied to fermentation, metabolism of aromatic amino acids and sulfur-containing amino acids played a much significant role during glucosinolate, isothiocyanante and sinapate degradation

(Figure 5). This was in line with the observation that sinigrin induced oxidative stress significantly upregulated the glutathione metabolism and oxidative phosphorylation in Helicoverpa larvae [

19].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Canola Feedstock Treatment

Canola feedstock was procured internally within CSIRO. Larvae feeding on podding canola (canola growth stage 7) were collected from CSIRO Boorowa Agricultural Research Station (Week 1, November 2023). The larvae (n = 5) were rinsed with 0.9% saline, followed by 2 rinses of sterile distilled water in a sterile 2 mL centrifuge tube (round bottom, Eppendorf Pty Ltd., Sydney, NSW, Australia). Sterile Luria Bertini (LB) broth, 1 mL, was added to the tubes containing larvae. Two sterile stainless-steel beads (3 mm diameter) were added to each tube, and larvae were homogenised through vortexing at 1000 rpm (Fastprep-96, MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA, USA).

Canola feedstock, 1g, was added to sterile LB broth, and resterilised through pasteurisation (72°C/ 30 minutes). The growth medium was cooled to room temperature, and 0.2 mL larval homogenate was added to the medium. To compare the fermentation and to mimic the conditions of the larval gut [

24], one set each was fermented at pH 7 and pH 10 medium (pH 10 adjusted by addition of NH

4OH), respectively. Both the sets were incubated 25°C for 1 week, followed by immediate cooling to 4°C. Slurry (1 mL) was pipetted from the culture, and immediately stored at -80°C to cease metabolism. Metabolomics analysis of the frozen samples was performed to identify the mechanism of canola feedstock bioconversion and quantify the biological transformation of glucosinolates and their degradation products.

4.2. Metabolomics Sample Preparation and Analysis

100 µL of slurry was taken into fresh 2 mL centrifuge tube and prepared for analysis as previously reported [

22]. Briefly, 450 µL of ice-cold ethanol: methanol (1:1), containing 1 µg/mL of internal standards (

13C

4-succinic acid,

13C-phenylalanine, both Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Tewkesbury, MA, USA), was added to 100 µL slurry, followed by 100 µL ice cold MilliQ water. The mixture was then vortexed for 10 minutes at 1,400 rpm/ 4°C (Thermomixer, Eppendorf) and centrifuged at 14000g/ 2 minutes. The supernatant was transferred to an EMR lipid extraction cartridge on a vacuum manifold (Agilent Technologies, Mulgrave, VIC, Australia). The aqueous phase was collected in a fresh tube through applying constant vacuum (2 inHg). The cartridge was rinsed with 200 µL ethanol: methanol: water (1:1:2) to elute any aqueous metabolites. The aqueous eluate was then dried under nitrogen and resuspended in 200µL ice cold acetonitrile: water (8:2). The mixture was vortexed at 1,400 rpm/4°C for 1 hour on a thermomixer, followed by centrifugation at 14,000g/ 2 min., and the supernatants were transferred to LC-MS vials for analysis.

For LC-MS analysis, 2µL of the abovementioned supernatant was injected through ACQUITY UPLC® BEH Amide column, 150×2.1 mm, 1.7µm ID (Part 186004802, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Melbourne, VIC, Australia) on Vanquish Liquid Chromatograph (LC), coupled with QExactive Plus mass spectrometer (MS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Melbourne, VIC, Australia). The LC flowrate was maintained at 0.25 ml/min. Solvents A and B were acetonitrile: 10mM ammonium formate (10:90), and acetonitrile: 10mM ammonium formate (90:10), both pH 9, and contained 5 µL medronic acid. The gradient for Solvent B was 95% (0 – 3 min.), 78% (8 min.), 30% (15 min.), and 95% (20 min.). The column was conditioned with 95% Solvent B for further 2 min. The MS analysis was performed in both negative and positive modes. The parameters (negative/positive) were, spray voltage (2.5 kV/ 3.5kV), capillary temperature (262°C/262°C), sheath gas (50/50), auxiliary gas (12.5/12.5), spray current (100/100), probe heater (425°C/425°C) and S-Lens RF level (50/50). A full scan was performed within 60-750 m/z range, with the resolutions of 70,000 and 17,500 at MS1 and MS2 levels, respectively.

4.3. Statistical Analysis

The quality control (QC) metabolite mix was processed on the LC-MS system between every 10 samples. The QC mix contained 1µg/mL each of pyruvic acid, serine, maleic acid, succinic acid, asparagine, salicylic acid, citrulline, glucose, citric acid, and tryptophan (all Sigma Aldrich, Alexandria, NSW, Australia).

Metabolite features with signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio ≥ 10, and match factor ≥ 70% with respect to the mass spectral database were used as data filtration thresholds. The filtered data were normalised against 13C-phenylalanine on Microsoft® Excel.

This normalised data was then imported to MetaboAnalyst 6.0 for processing. Missing values for metabolite features were replaced by 1/5 of positive value, followed by sample normalisation through pooled sample group, and auto scaling of the data. The normalised dataset was further subjected to univariate (one-way ANOVA, biomarker analysis), advanced significance (Significance of Microarray), and multivariate (principal component (PCA), partial least square-discriminant (PLS-DA)) analyses. Furthermore, the data were also applied to metabolic enrichment and pathway analysis toolboxes.

5. Limitations

The current study provided a considerable insight into the application of insect gut microbiome in the biomass processing. However, as it was a proof-of-concept, we acknowledge the limitations of the study. Firstly, the stage of larvae was not considered in this study, which may play a considerable role in gut microbial spread within the herbivore gut [

37], and the resultant metabolism. Furthermore, the genomics, metaproteomics and lipidomic works will be needed to confirm the metabolomics outputs we presented in this study.

6. Conclusions

In this proof-of-concept study, the ability of gut microbiome from the brassica pest herbivores to bio-transform canola meal was assessed. We used LC-MS-based metabolomics to assess the biochemical changes occurred during the fermentation. Among all studies samples, highest glucosinolate and sinapate depletion, and SCFA increase, occurred in HP gut and frass at pH7 ferments. Of the 45 statistically significant metabolic pathways, aromatic amino acid and sulphur-containing amino acid metabolism was most prominent, countering toxicity stress. Metabolomic assessment indicated that the gut microbes of brassica pest herbivores drove considerable glucosinolate recycling and SCFA and biogenic amine production, thus decreasing the isothiocyanate toxicity for the host. The output of this study, post-scale up, the microbial fermentation has a potential to increase the value-addition of agro-wastes such as canola meal towards veterinary feedstock.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, A.V.K. and T.K.W; methodology, A.V.K..; software, A.V.K. and A.J.C; formal analysis, A.V.K.; investigation, A.V.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.V.K., T.K.W, X-R. Z; writing—review and editing, A.V.K., T.K.W, X-R. Z; visualization, A.V.K., T.K.W, X-R. Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by CSIRO Future Protein Mission through the Dorothy Hill Impossible Without You Fellowship provided to A.V.K.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HP |

Heliotis moth |

| WCF |

Cabbage white |

| CL |

Cabbage lopper |

| SCFA |

Short-chain fatty acid |

| SAM |

S-adenosyl methionine |

| LC-MS |

liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| CSIRO |

Commonwelth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation |

| QC |

Quality control |

| S/N |

Signal-to-noise |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of variance |

| PCA |

Principal component analysis |

| PLS-DA |

Partial least square-discriminant analysis |

| FDR |

False Discovery Rate |

| RSD |

Relative standard deviation |

| 5-MSPN |

5-methylsulfinyl pentanitrile |

| ITC |

Isothicyanate |

| HMTB |

2-hydroxy-4-methylthiobutyrate |

| FAA |

fatty acid amides |

| GLP-1 |

Glucagon-like peptide 1 |

References

- Australian-Bureau-of-Statistics. Australian agriculture: Broadacre crops: 2023-24 financial year. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.

- Ayton, J. Variability of quality traits in canola seed, oil and meal - a review 2014, 1-25.

- Slominski, B.; Evans, E.; Pierce, A.; Broderick, G.; Zijlstra, R.; Beltranna, E.; Drew, M. Canola meal feeding guide; Canola Council of Canada: Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, 2015; pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel, M.; Macelline, S.P.; Toghyani, M.; Chrystal, P.V.; Choct, M.; Cowieson, A.J.; Liu, S.Y.; Selle, P.H. The potential of canola to decrease soybean meal inclusions in diets for broiler chickens. Animal Nutrition 2025, 20, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejicanos, G.A.; Kim, J.W.; Nyachoti, C.M. Tail-end dehulling of canola meal improves apparent and standardized total tract digestibility of phosphorus when fed to growing pigs. J Anim Sci 2018, 96, 1430–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongsirichot, P.; Gonzalez-Miquel, M.; Winterburn, J. Rapeseed meal biorefining: Fractionation, valorization and integration approaches. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2024, 62, 103460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandasiri, R.; Imran, A.; Thiyam-Holländer, U.; Eskin, N.A.M. Rapidoxy® 100: A Solvent-Free Pre-treatment for Production of Canolol. Frontiers in Nutrition, 2021; 8, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongsirichot, P.; Gonzalez-Miquel, M.; Winterburn, J. Holistic valorization of rapeseed meal utilizing green solvents extraction and biopolymer production with Pseudomonas putida. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 230, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beale, D.J.; Shah, R.M.; Marcora, A.; Hulthen, A.; Karpe, A.V.; Pham, K.; Wijffels, G.; Paull, C. Is there any biological insight (or respite) for insects exposed to plastics? Measuring the impact on an insects central carbon metabolism when exposed to a plastic feed substrate. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 831, 154840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, F.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z. Black soldier fly larvae recruit functional microbiota into the intestines and residues to promote lignocellulosic degradation in domestic biodegradable waste. Environmental Pollution 2024, 340, 122676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeswari, G.; Jacob, S.; Chandel, A.K.; Kumar, V. Unlocking the potential of insect and ruminant host symbionts for recycling of lignocellulosic carbon with a biorefinery approach: a review. Microbial Cell Factories 2021, 20, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cibils-Stewart, X.; Kliebenstein, D.J.; Li, B.; Giles, K.; McCornack, B.P.; Nechols, J. Aphid Species and Feeding Location on Canola Influences the Impact of Glucosinolates on a Native Lady Beetle Predator. Environmental Entomology 2021, 51, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, P.; Buer, B.; Ilias, A.; Kaforou, S.; Aivaliotis, M.; Orfanoudaki, G.; Douris, V.; Geibel, S.; Vontas, J.; Denecke, S. A spatiotemporal atlas of the lepidopteran pest Helicoverpa armigera midgut provides insights into nutrient processing and pH regulation. BMC Genomics 2022, 23, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Shikano, I.; Liu, T.-X.; Felton, G.W. Helicoverpa zea–Associated Gut Bacteria as Drivers in Shaping Plant Anti-herbivore Defense in Tomato. Microbial Ecology 2023, 86, 2173–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.P.; Beran, F. Gut microbiota degrades toxic isothiocyanates in a flea beetle pest. Molecular Ecology 2020, 29, 4692–4705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Jiang, X.; Reichelt, M.; Gershenzon, J.; Vassão, D.G. The selective sequestration of glucosinolates by the cabbage aphid severely impacts a predatory lacewing. Journal of Pest Science 2021, 94, 1147–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeschke, V.; Gershenzon, J.; Vassão, D.G. Metabolism of Glucosinolates and Their Hydrolysis Products in Insect Herbivores. In The Formation, Structure and Activity of Phytochemicals, Jetter, R., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; pp. 163–194. [Google Scholar]

- Funke, M.; Büchler, R.; Mahobia, V.; Schneeberg, A.; Ramm, M.; Boland, W. Rapid Hydrolysis of Quorum-Sensing Molecules in the Gut of Lepidopteran Larvae. ChemBioChem 2008, 9, 1953–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagdale, S.; Tellis, M.; Barvkar, V.T.; Joshi, R.S. Glucosinolate induces transcriptomic and metabolic reprogramming in Helicoverpa armigera. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeschke, V.; Gershenzon, J.; Vassão, D.G. A mode of action of glucosinolate-derived isothiocyanates: Detoxification depletes glutathione and cysteine levels with ramifications on protein metabolism in Spodoptera littoralis. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2016, 71, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpe, A.V.; Hutton, M.L.; Mileto, S.J.; James, M.L.; Evans, C.; Ghodke, A.B.; Shah, R.M.; Metcalfe, S.S.; Liu, J.-W.; Walsh, T.; et al. Gut microbial perturbation and host response induce redox pathway upregulation along the Gut-Liver axis during giardiasis in C57BL/6J mouse model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpe, A.V.; Hutton, M.L.; Mileto, S.J.; James, M.L.; Evans, C.; Shah, R.M.; Ghodke, A.B.; Hillyer, K.E.; Metcalfe, S.S.; Liu, J.W.; et al. Cryptosporidiosis Modulates the Gut Microbiome and Metabolism in a Murine Infection Model. Metabolites 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashaolu, T.J.; Ashaolu, J.O.; Adeyeye, S.A.O. Fermentation of prebiotics by human colonic microbiota in vitro and short-chain fatty acids production: a critical review. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2021, 130, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dow, J.A.T. pH gradients in lepidopteran midgut. Journal of Experimental Biology 1992, 172, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.T.; Zhang, D.; Li, J.; Hui, R.K.H.; Tun, H.M.; Brar, M.S.; Park, T.-J.; Chen, Y.; Leung, F.C. Towards a metagenomic understanding on enhanced biomethane production from waste activated sludge after pH 10 pretreatment. Biotechnology for Biofuels 2013, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpe, A.V.; Dhamale, V.V.; Morrison, P.D.; Beale, D.J.; Harding, I.H.; Palombo, E.A. Winery biomass waste degradation by sequential sonication and mixed fungal enzyme treatments. Fungal Genetics and Biology 2017, 102, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, J.; Wishart, D.S. MetPA: a web-based metabolomics tool for pathway analysis and visualization. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2342–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieder, C.; Bundy, J.G.; Frainay, C.; Poupin, N.; Rodríguez-Mier, P.; Vinson, F.; Cooke, J.; Lai, R.P.J.; Jourdan, F.; Ebbels, T.M.D. Avoiding the Misuse of Pathway Analysis Tools in Environmental Metabolomics. Environ Sci Technol 2022, 56, 14219–14222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalgaard, L.; Nawaz, R.; So̵rensen, H. 3-Methylthiopropylamine and (R)-3-methylsulphinylpropylamine in Iberis amara. Phytochemistry 1977, 16, 931–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, P.E.; Anders, M.W. The mercapturic acid pathway. Critical Reviews in Toxicology 2019, 49, 819–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andernach, L.; Witzel, K.; Hanschen, F.S. Glucosinolate-derived amine formation in Brassica oleracea vegetables. Food Chemistry 2023, 405, 134907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deguenon, J.M.; Dhammi, A.; Ponnusamy, L.; Travanty, N.V.; Cave, G.; Lawrie, R.; Mott, D.; Reisig, D.; Kurtz, R.; Roe, R.M. Bacterial Microbiota of Field-Collected Helicoverpa zea (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) from Transgenic Bt and Non-Bt Cotton. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Fang, J.; Shen, L.; Ma, S.; Zhao, Z.; Yu, W.; Jiang, W. Diversity, Composition and Functional Inference of Gut Microbiota in Indian Cabbage white Pieris canidia (Lepidoptera: Pieridae). Life 2020, 10, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanschen, F.S. Acidification and tissue disruption affect glucosinolate and S-methyl-l-cysteine sulfoxide hydrolysis and formation of amines, isothiocyanates and other organosulfur compounds in red cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata f. rubra). Food Research International 2024, 178, 114004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Xin, X.; Wu, Q. Dynamics of the glucosinolate–myrosinase system in tuber mustard (Brassica juncea var. tumida) during pickling and its relationship with bacterial communities and fermentation characteristics. Food Research International 2022, 161, 111879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Chen, S. Regulation of plant glucosinolate metabolism. Planta 2007, 226, 1343–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhang, J.; Qin, Q.; Wu, P.; Zhang, H.; Meng, Q. Metabolic changes during larval–pupal metamorphosis of Helicoverpa armigera. Insect Science 2023, 30, 1663–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsugawa, H.; Cajka, T.; Kind, T.; Ma, Y.; Higgins, B.; Ikeda, K.; Kanazawa, M.; VanderGheynst, J.; Fiehn, O.; Arita, M. MS-DIAL: data-independent MS/MS deconvolution for comprehensive metabolome analysis. Nat Methods 2015, 12, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsugawa, H.; Ikeda, K.; Takahashi, M.; Satoh, A.; Mori, Y.; Uchino, H.; Okahashi, N.; Yamada, Y.; Tada, I.; Bonini, P.; et al. A lipidome atlas in MS-DIAL 4. Nature Biotechnology 2020, 38, 1159–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).