Submitted:

08 September 2025

Posted:

10 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

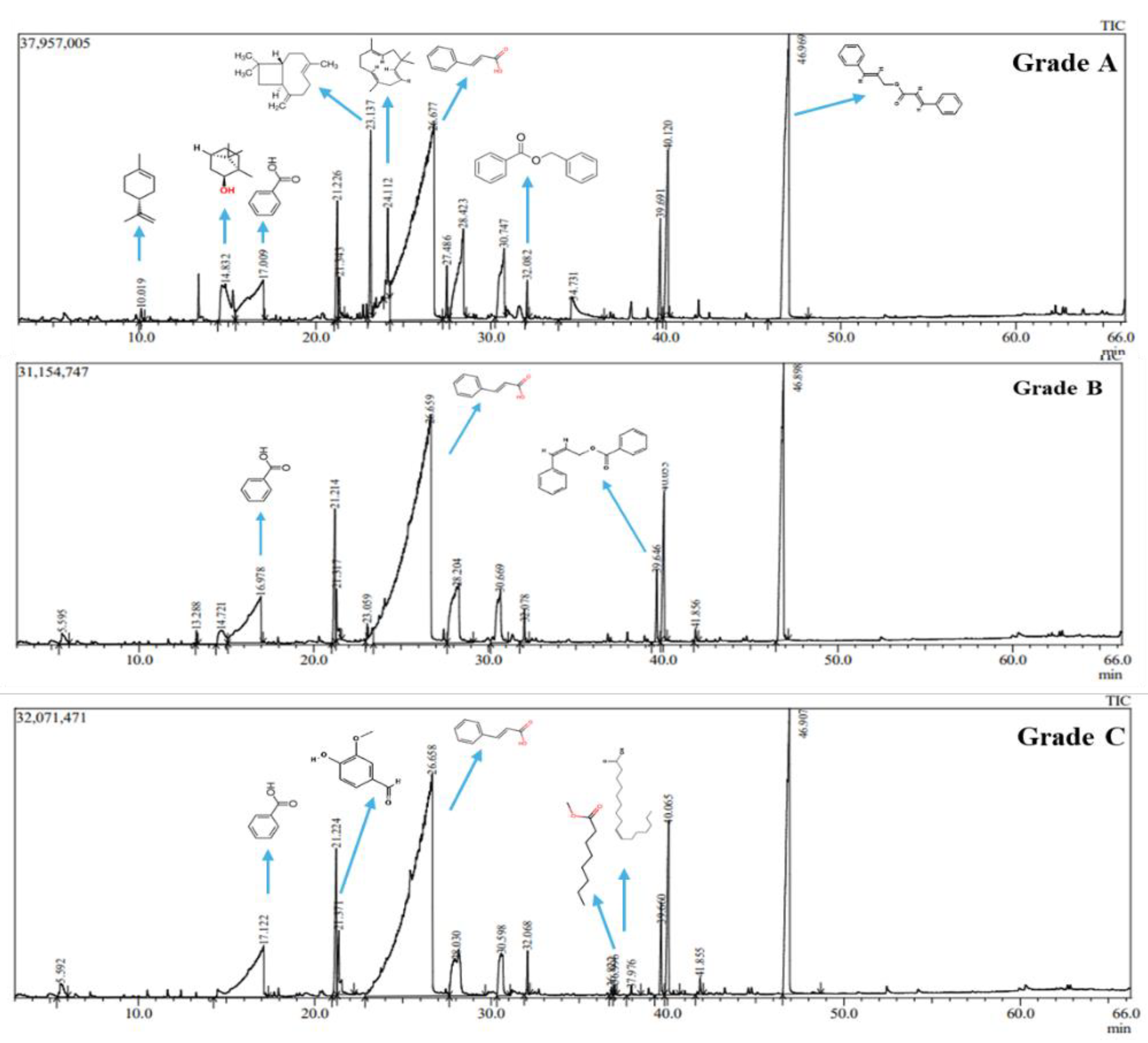

Sumatra benzoin (Styrax paralleloneurum) is a significant non-timber forest product originating from North Sumatra. Benzoin resin is widely used in perfumes, medicines, and cosmetics. However, scientific studies on phytochemical composition based on resin grades are limited. This study aimed to analyze the phytochemical compounds of benzoin oil extracted from three different resin grades. The resin was collected directly from benzoin trees in Humbang Hasundutan Regency. It was then extracted using 96% ethanol and analyzed by GC-MS method. The results showed that the highest quality resin produced higher oil yield (73.08%) with a longer extraction time. This indicates that resin quality influences extraction efficiency and composition. Chemical analysis identified key active compounds, such as cinnamic acid, benzoic acid, eugenol, vanillin, and various esters and aromatic hydrocarbons. High grade resin contains higher levels of volatile compounds such as D-limonene, endo-borneol, and β-caryophyllene. These are essential for aromatic and therapeutic activities. In contrast, lower quality resins are dominated by carboxylic acids. Cinnamic acid is prominent in all grades, reinforcing its potential as an active agent in natural-based cosmetic and pharmaceutical formulations. This research provides a scientific foundation for standardizing benzoin resin quality. It also supports its strategic utilization in natural bioactive-based industries.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Resin Hasvesting and Grading

2.2. Benzoin Oil Extraction

2.3. Analysis of Phytochemical Component

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Methods

3.3. Analysis Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anandakumar, P. , Kamaraj, S., & Vanitha, M. Journal of Food Biochemistry 2021, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, Y. , Pasaribu, G., & Nazari, M. Review on Bioactive Potential of Indonesian Forest Essential Oils. Pharmacognosy Journal 2022, 14, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparna, V. , Dileep, K. V., Mandal, P. K., Karthe, P., Sadasivan, C., & Haridas, M. Anti-Inflammatory Property of n -Hexadecanoic Acid: Structural Evidence and Kinetic Assessment. Chemical Biology & Drug Design. [CrossRef]

- Ariani, S. R. D. , Mulyani, S., Susilowati, E., Susanti VH, E., Prakoso, S. D. B., & Wijaya, F. N. A. Chemical composition, antibacterial, and antioxidant activities of turmeric, javanese ginger, and pale turmeric essential oils that growing in Indonesia. Journal of Essential Oil-Bearing Plants, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariani, S. R. D. , Purniasari, L., Basyiroh, U., & Evangelista, E. Chemical Composition, Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities of Essential Oils from Peels of Four Citrus Species Growing in Indonesia. Journal of Essential Oil-Bearing Plants. [CrossRef]

- Aryani, F. , Kusuma, I. W., Meliana, Y., Sari, N. M., & Kuspradini, H. Potential antibacterial and antioxidant activities of ten essential oils from East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Biodiversitas. [CrossRef]

- Aswandi, A. , & Kholibrina, C. R. The grading classification for Styrax sumatrana resins based on physico chemical characteristics using two-step cluster analysis. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 0120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aswandi, A. , Kholibrina, C. R., & Kuspradini, H. (2024). Essential Oils for Cosmetics Application. In Biomass-Based Cosmetics: Research Trends and Future Outlook (pp. 151–173). [CrossRef]

- Bakhshabadi, H. , Ganje, M., Gharekhani, M., Mohammadi-Moghaddam, T., Aulestia, C., & Morshedi, A. A Review of New Methods for Extracting Oil from Plants to Enhance the Efficiency and Physicochemical Properties of the Extracted Oils. Processes. [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, U. , Kumar, A., Lohani, H., & Chauhan, N. Chemical Composition of Essential Oil of Camphor Tree ( Cinnamomum camphora ) Leaves Grown in Doon Valley of Uttarakhand. Journal of Essential Oil Bearing Plants. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S. P. , Letizia, C. S., & Api, A. M. Fragrance material review on β-caryophyllene alcohol. Food and Chemical Toxicology. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S. P. , Wellington, G. A., Cocchiara, J., Lalko, J., Letizia, C. S., & Api, A. M. Fragrance material review on cinnamyl benzoate. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2007, 45, S58–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S. P. , Wellington, G. A., Cocchiara, J., Lalko, J., Letizia, C. S., & Api, A. M. Fragrance material review on cinnamyl cinnamate. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2007, 45, S66–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, P. , Casale, A., Kerdudo, A., Michel, T., Laville, R., Chagnaud, F., & Fernandez, X. New insights in the chemical composition of benzoin balsams. Food Chemistry 2016, 210, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccoli, R. D. , Bianchi, D. A., Zocchi, S. B., & Rial, D. V. Mapping the field of aroma ester biosynthesis: A review and bibliometric analysis. Process Biochemistry. [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.-S. , Hong, J. Y., Lee, J.-H., Lee, H.-J., Park, J. Y., Choi, J.-H., Park, H.-J., Hong, J., & Lee, K.-T. β-Caryophyllene in the Essential Oil from Chrysanthemum Boreale Induces G1 Phase Cell Cycle Arrest in Human Lung Cancer Cells. Molecules 2019, 24, 3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claire Fuller, L. , & Sunderkötter, C. Scabies therapy update: Should 25% benzyl benzoate emulsion be reconsidered as a first-line agent in classical scabies? British Journal of Dermatology 2024, 190, 459–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalavaye, N. , Nicholas, M., Pillai, M., Erridge, S., & Sodergren, M. H. The Clinical Translation of α-humulene – A Scoping Review. Planta Medica. [CrossRef]

- Daniel, A. N. , Sartoretto, S. M., Schmidt, G., Caparroz-Assef, S. M., Bersani-Amado, C. A., & Cuman, R. K. N. Anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activities of eugenol essential oil in experimental animal models. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia. [CrossRef]

- del Olmo, A. , Calzada, J., & Nuñez, M. Benzoic acid and its derivatives as naturally occurring compounds in foods and as additives: Uses, exposure, and controversy. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwekeel, A. , Hassan, M., Almutairi, E., AlHammad, M., Alwhbi, F., Abdel-Bakky, M., Amin, E., & Mohamed, E. Anti-Inflammatory, Anti-Oxidant, GC-MS Profiling and Molecular Docking Analyses of Non-Polar Extracts from Five Salsola Species. Separations 2023, 10, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazmiya, M. J. A. , Sultana, A., Rahman, K., Heyat, M. B. Bin, Sumbul, Akhtar, F., Khan, S., & Appiah, S. C. Y. Current Insights on Bioactive Molecules, Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Other Pharmacological Activities of Cinnamomum camphora Linn. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, X. , Lizzani-Cuvelier, L., Loiseau, A.-M., Périchet, C., & Delbecque, C. Volatile constituents of benzoin gums: Siam and Sumatra. Part 1. Flavour and Fragrance Journal. [CrossRef]

- Fidyt, K. , Fiedorowicz, A., Strządała, L., & Szumny, A. β -caryophyllene and β -caryophyllene oxide—natural compounds of anticancer and analgesic properties. Cancer Medicine 2016, 5, 3007–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francomano, F. , Caruso, A., Barbarossa, A., Fazio, A., La Torre, C., Ceramella, J., Mallamaci, R., Saturnino, C., Iacopetta, D., & Sinicropi, M. S. β-Caryophyllene: A Sesquiterpene with Countless Biological Properties. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, M. , Ribeiro, D., Janela, J. S., Varela, C. L., Costa, S. C., da Silva, E. T., Fernandes, E., & Roleira, F. M. F. Plant-derived and dietary phenolic cinnamic acid derivatives: Anti-inflammatory properties. Food Chemistry, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Bofill, M. , Sutton, P. W., Guillén, M., & Álvaro, G. Enzymatic synthesis of vanillin catalysed by an eugenol oxidase. Applied Catalysis A: General, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groza, N. V. , Yarkova, T. A., Gessler, N. N., & Rozumiy, A. V. Synthesis of Benzoic Acid Esters and Their Antimicrobial Activity. Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal 2024, 58, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunia-Krzyżak, A. , Słoczyńska, K., Popiół, J., Koczurkiewicz, P., Marona, H., & Pękala, E. Cinnamic acid derivatives in cosmetics: current use and future prospects. International Journal of Cosmetic Science. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V. , Tyagi, S., & Tripathi, R. Hexadecanoic acid methyl ester, a potent hepatoprotective compound in leaves of Pistia stratiotes L. The Applied Biology & Chemistry Journal. [CrossRef]

- Gyrdymova, Y. V. , & Rubtsova, S. A. Caryophyllene and caryophyllene oxide: a variety of chemical transformations and biological activities. Chemical Papers. [CrossRef]

- Hamad, A. , Mahardika, M. G. P., Yuliani, I., & Hartanti, D. Chemical constituents and antimicrobial activities of essential oils of Syzygium polyanthum and Syzygium aromaticum. Rasayan Journal of Chemistry. [CrossRef]

- Harada, K. , Wiyono, & Munthe, L. Production and commercialization of benzoin resin: Exploring the value of benzoin resin for local livelihoods in North Sumatra, Indonesia. Trees, Forests and People, 0017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q. , Sun, Y., Chen, X., Feng, J., & Liu, Y. Benzoin Resin: An Overview on Its Production Process, Phytochemistry, Traditional Use and Quality Control. Plants. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X. , Yan, Y., Liu, W., Liu, J., Fan, T., Deng, H., & Cai, Y. Advances and perspectives on pharmacological activities and mechanisms of the monoterpene borneol. Phytomedicine 2024, 132, 155848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.-S. , Zhu, Y.-J., Li, H.-L., Zhuang, J.-X., Zhang, C.-L., Zhou, J.-J., Li, W.-G., & Chen, Q.-X. Inhibitory Effects of Methyl trans -Cinnamate on Mushroom Tyrosinase and Its Antimicrobial Activities. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H. , Wang, J., Song, L., Cao, X., Yao, X., Tang, F., & Yue, Y. GC×GC-TOFMS Analysis of Essential Oils Composition from Leaves, Twigs and Seeds of Cinnamomum camphora L. Presl and Their Insecticidal and Repellent Activities. Molecules 2016, 21, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafali, M. , Finos, M. A., & Tsoupras, A. Vanillin and Its Derivatives: A Critical Review of Their Anti-Inflammatory, Anti-Infective, Wound-Healing, Neuroprotective, and Anti-Cancer Health-Promoting Benefits. Nutraceuticals. [CrossRef]

- Kholibrina, C. R. , & Aswandi, A. Increasing added-value of styrax resin through post-harvesting techniques improvement and essential oil based product innovation. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. [CrossRef]

- Kholibrina, C. R. , & Aswandi, A. The Consumer Preferences for New Sumatran Camphor Essential Oil-based Products using a Conjoint Analysis Approach. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. [CrossRef]

- Kisiriko, M. , Anastasiadi, M., Terry, L. A., Yasri, A., Beale, M. H., & Ward, J. L. Phenolics from Medicinal and Aromatic Plants: Characterisation and Potential as Biostimulants and Bioprotectants. Molecules. [CrossRef]

- Kılıç Süloğlu, A. , Koçkaya, E. A., & Selmanoğlu, G. Toxicity of benzyl benzoate as a food additive and pharmaceutical agent. Toxicology and Industrial Health 2022, 38, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuspradini, H. , Putri, A. S., & Egra, S. Short communication: In vitro antibacterial activity of essential oils from twelve aromatic plants from East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Biodiversitas, 2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajarin-Reinares, M. , Martinez-Esteve, E., Pena-Rodríguez, E., Cañellas-Santos, M., Bulut, S., Karabelas, K., Clauss, A., Nieto, C., Mallandrich, M., & Fernandez-Campos, F. The Efficacy and Biopharmaceutical Properties of a Fixed-Dose Combination of Disulfiram and Benzyl Benzoate. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 0969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H. , Kim, D.-S., Park, S.-H., & Park, H. Phytochemistry and Applications of Cinnamomum camphora Essential Oils. Molecules 2022, 27, 2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H. , Li, Z., Sun, Y., Zhang, Y., Wang, S., Zhang, Q., Cai, T., Xiang, W., Zeng, C., & Tang, J. D-Limonene: Promising and Sustainable Natural Bioactive Compound. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 4605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Álvarez, Ó. , Zas, R., & Marey-Perez, M. Resin tapping: A review of the main factors modulating pine resin yield. Industrial Crops and Products, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes de Lacerda Leite, G. , de Oliveira Barbosa, M., Pereira Lopes, M. J., de Araújo Delmondes, G., Bezerra, D. S., Araújo, I. M., Carvalho de Alencar, C. D., Melo Coutinho, H. D., Peixoto, L. R., Barbosa-Filho, J. M., Bezerra Felipe, C. F., Barbosa, R., Alencar de Menezes, I. R., & Kerntof, M. R. Pharmacological and toxicological activities of α-humulene and its isomers: A systematic review. Trends in Food Science & Technology. [CrossRef]

- Meredith, W. , Kelland, S.-J., & Jones, D. M. Influence of biodegradation on crude oil acidity and carboxylic acid composition. Organic Geochemistry 2000, 31, 1059–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, M. F. , Khadim, M., Rafiq, M., Chen, J., Yang, Y., & Wan, C. C. Pharmacological Properties and Health Benefits of Eugenol: A Comprehensive Review. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. [CrossRef]

- Purushothaman, R. , Vishnuram, G., & Ramanathan, T. Antiinflammatory efficacy of n-Hexadecanoic acid from a mangrove plant Excoecaria agallocha L. through in silico, in vitro and in vivo. Pharmacological Research - Natural Products, 0203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruwizhi, N. , & Aderibigbe, B. A. Cinnamic Acid Derivatives and Their Biological Efficacy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruwizhi, N. , & Aderibigbe, B. A. Cinnamic Acid Derivatives and Their Biological Efficacy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SÁ, A. G. A. , Meneses, A. C. de, Araújo, P. H. H. de, & Oliveira, D. de. A review on enzymatic synthesis of aromatic esters used as flavor ingredients for food, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals industries. Trends in Food Science & Technology. [CrossRef]

- Sadgrove, N. , Padilla-González, G., & Phumthum, M. Fundamental Chemistry of Essential Oils and Volatile Organic Compounds, Methods of Analysis and Authentication. Plants. [CrossRef]

- Samanta, A. , Ojha, K., & Mandal, A. Interactions between Acidic Crude Oil and Alkali and Their Effects on Enhanced Oil Recovery. Energy & Fuels, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandiffio, R. , Geddo, F., Cottone, E., Querio, G., Antoniotti, S., Gallo, M. P., Maffei, M. E., & Bovolin, P. Protective Effects of (E)-β-Caryophyllene (BCP) in Chronic Inflammation. Nutrients. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R. , & Jawaid, T. Cinnamomum camphora (Kapur): Review. Pharmacognosy Journal. [CrossRef]

- Tang, M. , Zhong, W., Guo, L., Zeng, H., & Pang, Y. Role of borneol as enhancer in drug formulation: A review. Chinese Herbal Medicines. [CrossRef]

- Ulanowska, M. , & Olas, B. Biological Properties and Prospects for the Application of Eugenol—A Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Velika, B. , & Kron, I. Antioxidant properties of benzoic acid derivatives against Superoxide radical. Free Radicals and Antioxidants 2012, 2, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. , An, W., Wang, Z., Zhao, Y., Han, B., Tao, H., Wang, J., & Wang, X. Vanillin Has Potent Antibacterial, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Activities In Vitro and in Mouse Colitis Induced by Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli. Antioxidants. [CrossRef]

- Zari, A. T. , Zari, T. A., & Hakeem, K. R. Anticancer properties of eugenol: A review. Molecules. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. , Huang, T., Liao, X., Zhou, Y., Chen, S., Chen, J., & Xiong, W. Extraction of Camphor Tree Essential Oil by Steam Distillation and Supercritical CO2 Extraction. Molecules 2022, 27, 5385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. , Cai, P., Cheng, G., & Zhang, Y. A Brief Review of Phenolic Compounds Identified from Plants: Their Extraction, Analysis, and Biological Activity. Natural Product Communications. [CrossRef]

| Material | Benzoin resin (g) | Benzoin oil (g) | Time (minutes) | Extraction Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade A | 514.0 ± 21.73 | 375.4 ± 20.95 | 58.2 ± 7.11 | 73.08 ± 4.44 |

| Grade B | 571.2 ± 10.15 | 265.4 ± 24.14 | 40.4 ± 5.16 | 46.44 ± 3.77 |

| Grade C | 400.4 ± 13.06 | 112.8 ± 16.83 | 29.2 ± 5.08 | 28.18 ± 4.39 |

| No | Formula | Categories | Compound | CAS | Area of Content % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade A | Grade B | Grade C | |||||

| 1 | C₁₀H₁₆ | Hydrocarbon | D-Limonene | 5989-27-5 | 0.23 | - | - |

| 2 | C₁₀H₁₈O | Alcohol | Endo-Borneol | 507-70-0 | 4.02 | 1.18 | - |

| 3 | C₁₀H₁₆O | Ketone | (+)-2-Bornanone (camphor) | 464-49-3 | - | 0.12 | - |

| 4 | C₇H₆O₂ | Carboxylic acid | Benzoic acid | 65-85-0 | 6.78 | 8.02 | 9.96 |

| 5 | C₁₀H₁₂O₂ | Phenol | Eugenol | 97-53-0 | 6.10 | 5.91 | 4.40 |

| 6 | C₈H₈O₃ | Aldehyde | Vanillin | 121-33-5 | 4.18 | 3.79 | 3.81 |

| 7 | C₁₅H₂₄ | Hydrocarbon | β-Caryophyllene | 87-44-5 | 2.53 | 0.14 | - |

| 8 | C₁₅H₂₄ | Hydrocarbon | Humulene | 6753-98-6 | 1.51 | - | - |

| 9 | C₉H₈O₂ | Carboxylic acid | Cinnamic acid | 140-10-3 | 48.80 | 62.98 | 60.88 |

| 10 | C₁₅H₂₆O | Alcohol | Caryophyllenyl alcohol | 56747-96-7 | 0.64 | - | - |

| 11 | C₁₄H₁₂O₂ | Ester | Benzyl benzoate | 120-51-4 | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| 12 | C₁₅H₂₄O | Oxide | Caryophyllene oxide | 1139-30-6 | 2.40 | - | |

| 13 | C₁₅H₂₂O₂ | Carboxylic acid | 3,5-Bis(1,1-dimethylethyl) benzoic acid | 16225-26-6 | - | - | 0.10 |

| 14 | C₁₈H₃₆O₂ | Ester | Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | 158274-92-1 | - | - | 0.10 |

| 15 | C₁₆H₃₂O₂ | Carboxylic acid | n-Hexadecanoic acid | 57-10-3 | - | - | 0.16 |

| 16 | C₁₆H₁₄O₂ | Ester | (Z)-Cinnamyl benzoate | 117204-78-1 | 1.59 | 1.02 | 1.31 |

| 17 | C₁₀H₁₀O₂ | Ester | Methyl cinnamate | 103-26-4 | 5.91 | 5.30 | 6.24 |

| 18 | C₁₈H₁₆O₂ | Ester | Cinnamyl cinnamate | 122-69-0 | 14.89 | 10.55 | 11.86 |

| Composition | Compound | Area of Content % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade A | Grade B | Grade C | ||

| Hydrocarbon | D-Limonene, β-Caryophyllene, Humulene | 4.27 | - | 0.14 |

| Alcohol | Endo-Borneol, Caryophyllenyl alcohol | 4.66 | - | 1.18 |

| Ketone | (+)-2-Bornanone (camphor) | - | - | 0.12 |

| Phenol | Eugenol | 6.10 | 4.40 | 5.91 |

| Aldehyde | Vanillin | 4.18 | 3.81 | 3.79 |

| Carboxylic acid | Benzoic acid, Cinnamic acid, 3,5-Bis(1,1-dimethylethyl) benzoic acid, n-Hexadecanoic acid | 55.58 | 71.10 | 71.00 |

| Oxide | Caryophyllene oxide, | 2.40 | - | - |

| Ester | Benzyl benzoate, Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester, (Z)-Cinnamyl benzoate, Methyl cinnamate, Cinnamyl cinnamate | 22.8 | 20.01 | 17.37 |

| Compound | Aroma Profile | Bioactivity | Application | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavour | Fragrance | Cosmetic | Medicine | |||

| D-Limonene | citrusy, sweet | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antibacterial, and natural solvent of topical drugs (Anandakumar et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2024) | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Endo-Borneol | Soft, woody, balsamic camphor. | Antibacterial, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, relieves pain and fever (Hu et al., 2024) | - | √ | √ | √ |

| (+)-2-Bornanone (camphor) | Sharp, refreshing, minty camphor | Topical analgesic, antiseptic, anti-inflammatory, rubefacient - improves blood circulation (Fazmiya et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2022; Singh & Jawaid, 2012) | - | √ | √ | √ |

| Benzoic acid | It has no distinctive aroma, slightly sweet. | Antimicrobial, antifungal, cosmetic and food preservative (del Olmo et al., 2017; Groza et al., 2024) | √ | - | √ | √ |

| Eugenol | Spicy, warm, clove-like | Antiseptic, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, often used in dentistry (Nisar et al., 2021; Ulanowska & Olas, 2021) | √ | - | √ | - |

| Vanillin | Sweet, creamy, classic vanilla | Antioxidant, antimicrobial, neuroprotective, used in food and cosmetics (Kafali et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024) | √ | √ | √ | - |

| β-Caryophyllene | Woody, spicy, dry | Anti-inflammatory, analgesic, interaction with CB2 (cannabinoid) receptors, anticancer (Francomano et al., 2019; Scandiffio et al., 2020) | - | √ | √ | √ |

| Humulene | earthy, woody, slightly spicy | Anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, potential as an anticancer (Dalavaye et al., 2024; Mendes de Lacerda Leite et al., 2021) | - | √ | - | - |

| Cinnamic acid | Sweet, balsamic, cinnamon-like | Antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, treating cancer, sunscreen and skin lightening product (Freitas et al., 2024; Ruwizhi & Aderibigbe, 2020a, 2020b) | √ | - | √ | √ |

| Caryophyllenyl alcohol | Woody, slightly floral | Antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, sedative effects (Bhatia et al., 2008) | - | √ | - | √ |

| Benzyl benzoate | Slightly floral-balsamic | Antiparasitic (scabies, lice), solvent in perfumes and lotions, anti-inflammatory (Claire Fuller & Sunderkötter, 2024; Lajarin-Reinares et al., 2022) | - | - | √ | √ |

| Caryophyllene oxide | Woody, spicy, fresh | Antifungal, antioxidant, potential anticancer (Fidyt et al., 2016; Gyrdymova & Rubtsova, 2022) | - | √ | - | √ |

| 3,5-Bis(1,1-dimethyl-ethyl) benzoic acid | Not typical, neutral | Antioxidant, protective against oxidative stress (Velika & Kron, 2012) | - | - | √ | √ |

| Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | Slightly waxy or fatty | Anti-inflammatory, emollient, hepatoprotective, UV protective (Elwekeel et al., 2023; Gupta et al., 2023) | - | - | √ | - |

| n-Hexadecanoic acid | fatty, waxy. | Antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, natural emollient (Aparna et al., 2012; Purushothaman et al., 2025) | - | - | √ | √ |

| (Z)-Cinnamyl benzoate | Floral, balsamic, sweet | Mild antimicrobial, used as a fragrance ingredient (Bhatia et al., 2007a) | √ | √ | - | - |

| Methyl cinnamate | Sweet, fruity, like strawberries | Antimicrobial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory (Huang et al., 2009) | √ | √ | √ | - |

| Cinnamyl cinnamate | Warm, balsamic, sweet, spicy | Antioxidant, antimicrobial, fixative in perfume (Bhatia et al., 2007b) | √ | √ | - | - |

| Tree Sampling | Resin collected (gram) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade A | Grade B | Grade C | Total | |

| P1 | ||||

| P2 | ||||

| P3 | ||||

| P4 | ||||

| P5 | ||||

| Material | Resin Weight (g) M1 |

Extraction Time (minutes) |

Oil Weight (g) M2 |

Extraction Rate (%) (M2/M1)*100% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade A | ||||

| A1 | ||||

| A2 | ||||

| A3 | ||||

| A4 | ||||

| A5 | ||||

| Grade B | ||||

| B1 | ||||

| B2 | ||||

| B3 | ||||

| B4 | ||||

| B5 | ||||

| Grade C | ||||

| C1 | ||||

| C2 | ||||

| C3 | ||||

| C4 | ||||

| C5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).