Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Extraction of Volatiles

2.3. Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS) Analysis

2.4. General Information for Chemical Characterization

2.5. Resin Fractionation of Bursera bipinnata

2.6. Isolated Compounds

2.6. In Vitro Anti-Inflammatory Activity

2.6.1. Cell Culture

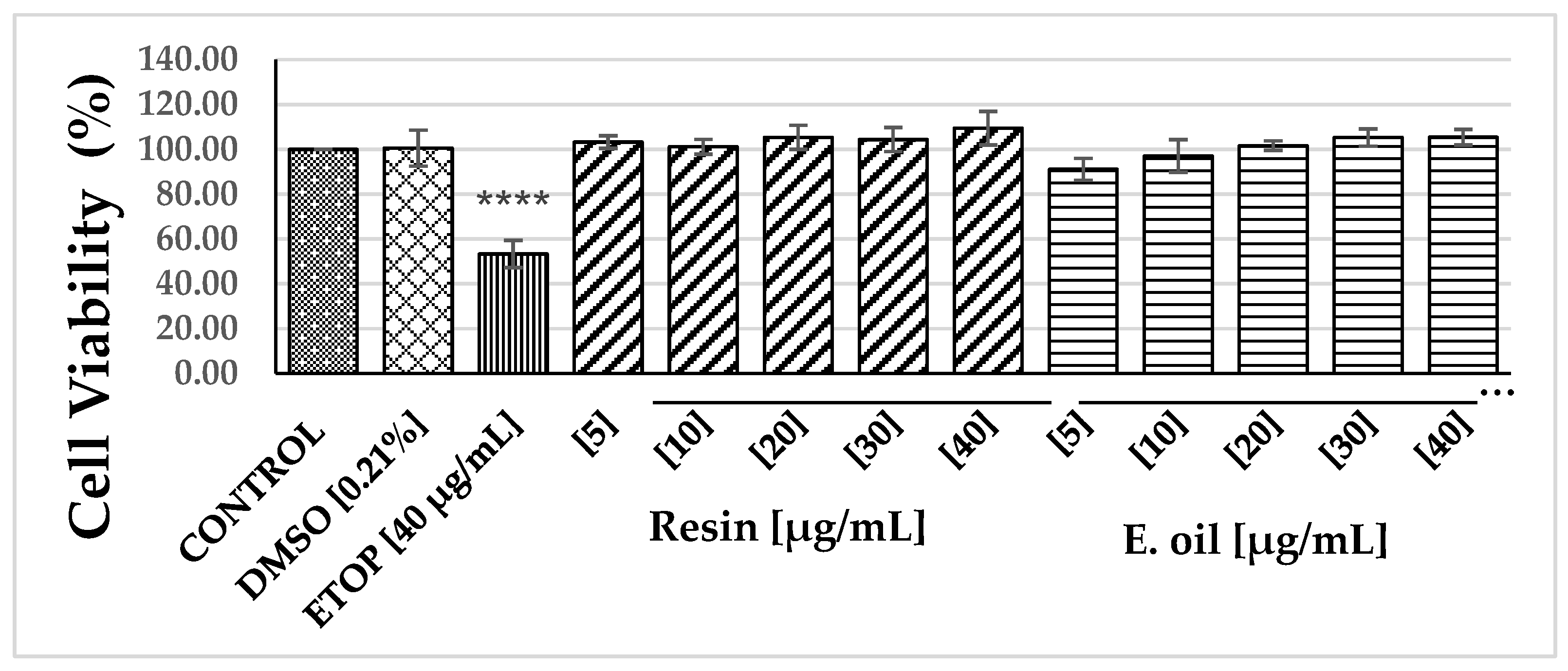

2.6.2. MTS Assay to Determine Cell Viability

2.6.3. Treatment of Macrophages with LPS

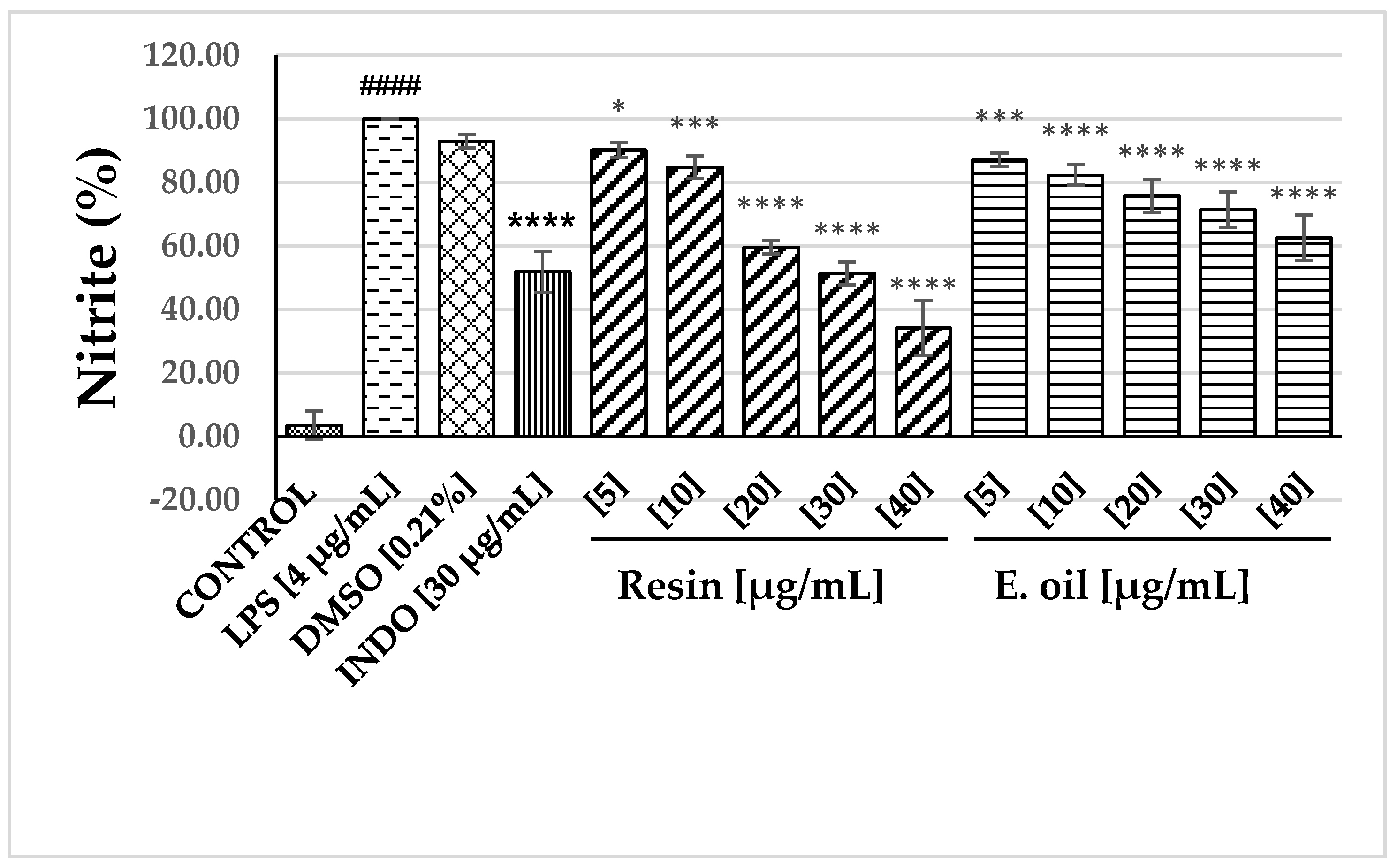

2.6.3. Determination of NO Concentration

3. Results

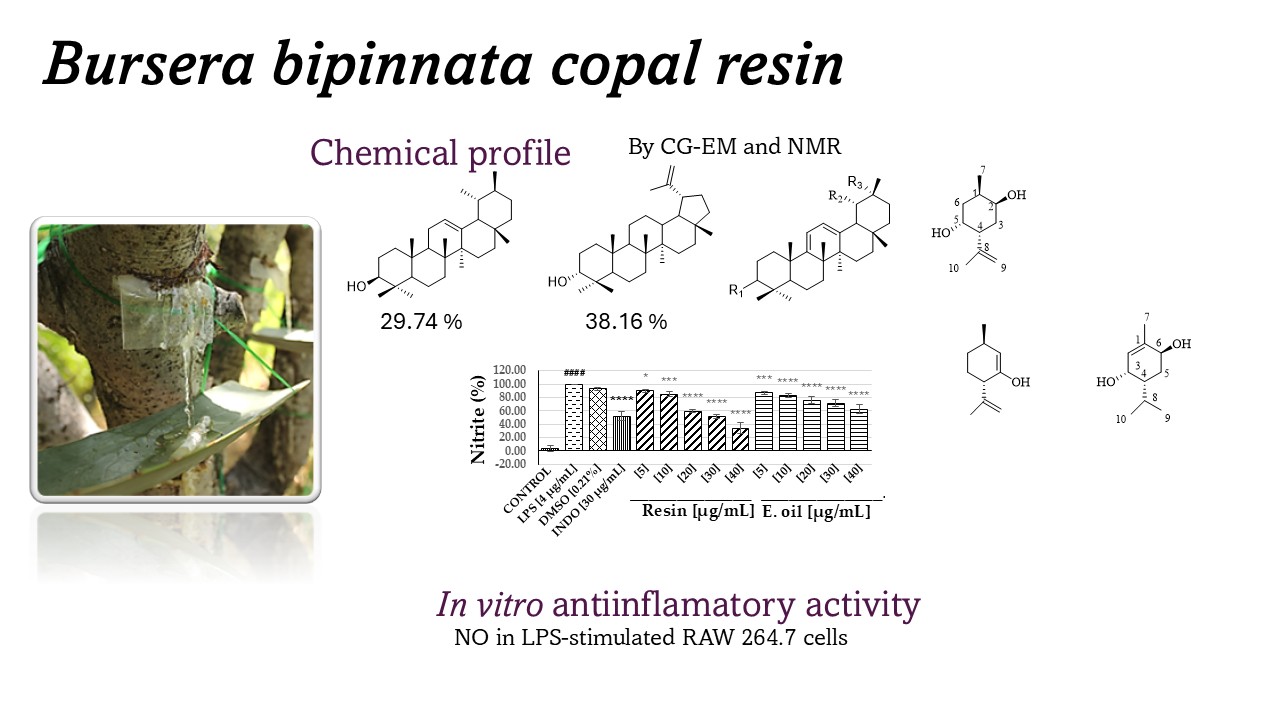

3.1. In Vitro Anti-Inflammatory Activity of the Total Resin and Its Volatile Fraction of Bursera bipinnata

3.2. Chemical Profiles

3.2.1. Volatile Compounds Present in the Resin of B. bipinnata

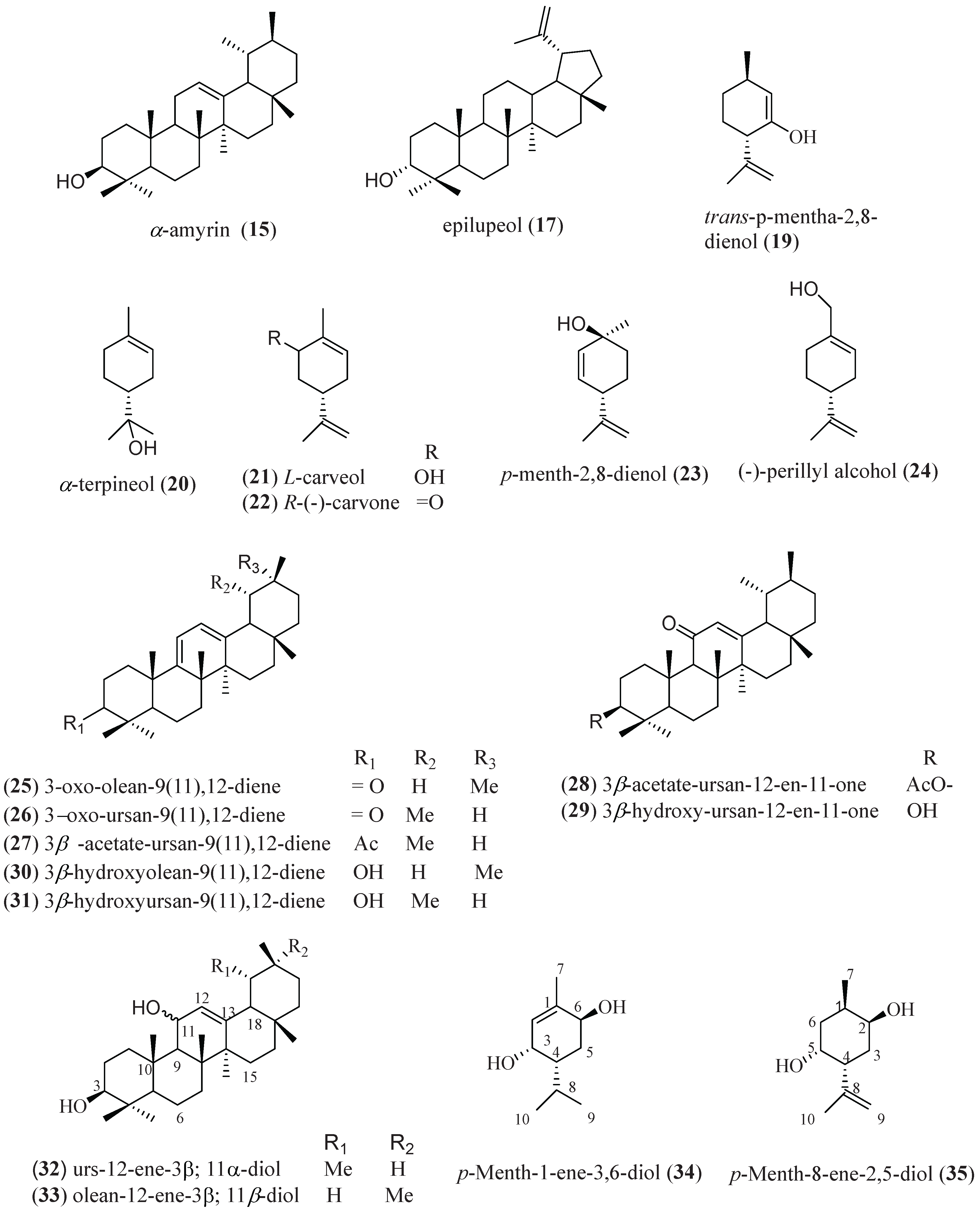

3.2.1. Phytochemical Analysis of B. bipinnata Resin

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Montúfar LA (2016) Copal de Bursera bipinnata. Una resina mesoamericana de uso ritual. Trace 70, cemca 45-77, ISSN: 0185-6286.

- Case RJ, Tucker AO, Maciarello MJ, Wheeler KA (2003) Chemistry and Ethnobotany of Commercial Incense Copals, Copal Blanco, Copal Oro, and Copal Negro, of North America. Econ Bot 57:189–202. [CrossRef]

- Rzedowski J, Medina-Lemos R, Calderón de Rzedowski G (2005) Inventario del conocimiento taxonómico, así como de la diversidad y del endemismo regionales de las especies mexicanas de Bursera (Burseraceae). Acta Botánica Mexicana, 70: 85–111. [CrossRef]

- Purata SEV (2008) Uso y Manejo de Los Copales Aromáticos: Resinas y Aceites. Colección Manejo campesino CONABIO/RAISES México:1-60.

- Argueta A, Cano LM, Rodarte ME (1994) Atlas de las Plantas de la Medicina Tradicional Mexicana. México: Biblioteca Digital de la Medicina Tradicional Mexicana. http://www.medicinatradicionalmexicana.unam.mx/apmtm/termino.php?l=3&t=bursera-bipinnata.

- Gigliarelli G, Becerra JX, Curini M, Marcotullio MC (2015) Chemical Composition and Biological Activities of Fragrant Mexican Copal (Bursera spp.). Molecules 20:22383–22394. [CrossRef]

- Crowley KJ (1964) Some Terpenic Constituents of Bursera graveolens (H. B.K.) Tr. Et Pl.var. villosula Cuatr. Journal of Chemistry Society: 4254-4256. [CrossRef]

- Syamasundar KV, Mallavarapu GR, Krishna EM (1991) Triterpenoids of the Resin of Bursera delpechiana. Phytochemistry 30:362–3. [CrossRef]

- Peraza-Sánchez SR, Salazar-Aguilar NE, Peña Rodríguez LM (1995) A New Triterpene from the Resin of Bursera simaruba. J Nat Prod 58:271–4. [CrossRef]

- Lucero-Gómez P, Mathe C, Vieillescazes C, Bucio L, Belio I, Vega R (2013) Analysis of Mexican reference standards for Bursera spp. resins by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry and application to archaeological objects. J Archaeol Sci 41:679–90. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez AL, Habtemariam S, Parra F (2015) Inhibitory effects of Lupene-derived Pentacyclic Triterpenoids from Bursera simaruba on HSV-1 and HSV-2 in vitro replication. Nat Prod Res 29:2322–2327. [CrossRef]

- Curini M, Di Sano C, Zadra C, Gigliarelli G, Rascón-Valenzuela LA, Robles RE, Marcotullio MC (2015) Diterpenoids and Triterpenoids from the Resin of Bursera microphylla and Their Cytotoxic Activity. J Nat Prod 78:1184–1188. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Estrada A, Maldonado MA, González-Christen J, Marquina S, Garduño-Ramírez ML, Rodríguez-López V, Alvarez L (2016) Anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effects of six pentacyclic triterpenes isolated from the Mexican copal resin of Bursera copallifera. BMC Complement Altern Med 16: 422. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Monroy MB, León-Rivera I, Llanos-Romero R E, García-Bores AM, Guevara-Fefer P (2020) Cytotoxic activity and triterpenes content of nine Mexican species of Bursera. Natural Product Research. [CrossRef]

- Monroy C, Castillo P (2007) Plantas medicinales utilizadas en el estado de Morelos. México: Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas/Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos.

- Dorado O, Maldonado B, Arias D, Sorani V, Ramírez R, Leyva E, Valenzuela D (2005) Programa de Conservación y Manejo Reserva de la Biosfera Sierra de Huautla. Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas SEMARNAT, México. ISBN 968-817-744-X.

- Lucero-Gómez P, Mathe C, Vieillescazes C, Bucio-Galindo L, Belio-Reyes I, Vega-Aviña R (2014) Archaeobotanic: HPLC molecular profiles for the discrimination of copals in Mesoamerica. Application to the study of resin materials from objects of Aztec offerings. Archeosciences 38:119–133. [CrossRef]

- Hernández JD, García L, Hernández A, Alvarez R, Román LU (2002) Glicósidos de luteolina y miricetina de Burseraceae. Rev Soc Quím Méx 46: 295-300.

- Lautié E, Quintero R, Fliniaux MA, Villarreal ML (2008) Selection methodology with scoring system: application to Mexican plants producing podophyllotoxin related lignans. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 120:402–412. [CrossRef]

- Chib R, Kumar M, Rizvi M, Sharma S, Pandey A, Bani S, Andotra SS, Taneja SC, Shah B A (2014). Anti-inflammatory terpenoids from Boswellia ovalifoliolata. RSC Adv 4:8632–8637. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Estrada A, Boto A, González-Christen J, Romero-Estudillo I, Garduño-Ramírez ML, Razo-Hernández RS, Marquina S, Maldonado-Magaña A, Columba-Palomares MC, Sánchez-Carranza JN, Alvarez L (2022). Synthesis, Biological Evaluation, and Molecular Docking Study of 3-Amino and 3-Hydroxy-seco A Derivatives of α-Amyrin and 3-Epilupeol as Inhibitors of COX-2 Activity and NF-kB Activation. J Nat Prod 85: 787-803. [CrossRef]

- Herath HM, Athukoralage PS (1998). Oleanane Triterpenoids from Gordonia ceylanica. Natural Product Sciences 4(4): 253-256.

- Reyes CP, Jiménez IA, Bazzocchi IL (2017) Pentacyclic Triterpenoids from Maytenus cuzcoina. Natural Product Communications 12:675-678. [CrossRef]

- Ito K, Ito M (2013). The sedative effect of inhaled terpinolene in mice and its structure-activity relationships. Journal of Natural Medicines 67:833–837. [CrossRef]

- Quintans-Junior L, Moreira JC, Pasquali MA, Rabie SM, Pires AS, Schroder R, Rabelo TK, Santos JP, Lima PS, Cavalcanti SC, Araujo AA, Quintans JS, Gelain DP (2013). Antinociceptive activity and redox profile of the monoterpenes (+)-camphene, p-cymene, and geranyl acetate in experimental models. ISRN Toxicology, 2013, 459530. [CrossRef]

- Bechkri S, Magid AA, Voutquenne-Nazabadioko L, Berrehal D, Kabouche A, Lehbili M, Lakhal H, Abedini A, Gangloff SC, Morjani H, Kabouche Z (2019). Triterpenes from Salvia argentea var. aurasiaca and their antibacterial and cytotoxic activities. Fitoterapia 139:104296. [CrossRef]

- Stolow RD, Sachdev K (1965) The p-Menth-1-ene-3,6-diol: Correlation of absolute configuration with optical rotation. Tetrahedron 21:1889-1895. [CrossRef]

- Stolow RD, Sachdev K (1971) Absolute Configurations of the p-Menthane-2,5-diones and p-Menthane-2,5-diols. J Org Chem 36:960-966. [CrossRef]

- Yang G, Lee K, Lee M, Ham I, Choi HY (2012) Inhibition of lipopolysaccharide induced nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2 production by chloroform fraction of Cudrania tricuspidata in RAW 264.7 macrophages. BMC Complement Alter Med 12:250. [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga S, Tanaka R, Akaji M (1988) Triterpenoids from Euphorbia maculata, Phytochemistry 27:535-537. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka R, Matsunaga S (1988) Triterpene dienols and other constituents from the bark of Phyllanthus flexuous, Phytochemistry 27:2273-2277. [CrossRef]

- Yan HY, Wang KW (2017) Triterpenoids from Microtropis fokienensis. Chem Nat Compd 53:784–786. [CrossRef]

- Morikawa T, Oominami H, Matsuda H, Yoshikawa M (2011) New terpenoids, olibanumols D–G, from traditional Egyptian medicine olibanum, the gumresin of Boswellia carterii. J Nat Med 65:129–134. [CrossRef]

- Ikuta A, Morikawa A (1992). Triterpenes from Stauntona hexaphylla callus tissues. Journal of Natural Products 55:1230–1233. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi P, Tripathi P, Kashyap L, Singh V (2007) The role of nitric oxide in infammatory reactions. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 51:443–452. [CrossRef]

- Drehmer D, Mesquita LJP, Speck HCA, Alves-Filho JC, Hussell T, Townsend PA, Moncada S (2022). Nitric oxide favours tumour-promoting inflammation through mitochondria-dependent and -independent actions on macrophages. Redox Biology 54:102350. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi Y (2010) The regulatory role of nitric oxide in proinflammatory cytokine expression during the induction and resolution of inflammation. J Leukoc Biol 88:1157–1162. [CrossRef]

- Noguera B, Díaz E, García MV, San Feliciano A, López-Perez JL, Israel A (2004) Anti-inflammatory activity of leaf extract and fractions of Bursera simaruba (L.) Sarg (Burseraceae). Journal of Ethnopharmacology 92:129–133. [CrossRef]

- Abad MJ, Bermejo P, Carretero E, Martinez-Acitores C, Noguera B, Villar A (1996) Antiinflammatory activity of some medicinal plant extracts from Venezuela. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 55:63- 68. [CrossRef]

- Sosa S, Balick MJ, Arvigo R, Esposito RG, Pizza C, Altinier G, Tubaro A (2002) Screening of the topical anti-inflammatory activity of some Central American plants. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 81:211–215. [CrossRef]

- Carretero ME, López-Pérez JL, Tillet S, Abad MJ, Bermejo P, Israel A, Noguera B (2008) Preliminary study of the anti-inflammatory activity of hexane extract and fractions from Bursera simaruba (Linneo) Sarg. (Burseraceae) leaves. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 116:11–15. [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga B, Guevara-Fefer P, Herrera J, Contreras JL, Velasco L, Pérez FJ, Esquivel B (2005) Chemical composition and antiinflammatory activity of the volatile fractions from the bark of eight Mexican Bursera species. Planta Medica 71:825-828. [CrossRef]

- Acevedo M, Nuñez P, Gónzalez-Maya L, Cardoso-Taketa A, Villarreal ML (2015) Cytotoxic and Anti-inflammatory Activities of Bursera species from Mexico. J Clin Toxicol 5:1-8 pages. [CrossRef]

- Columba-Palomares MC, Villarreal ML, Marquina S, Romero-Estrada A, Rodríguez-López V, Zamilpa A, Alvarez L (2018) Antiproliferative and Anti-inflammatory Acyl Glucosyl Flavones from the Leaves of Bursera copallifera. J Mex Chem Soc 62:214-224. [CrossRef]

- Yasukawa K, Yu SY, Yamanouchi S, Takido M, Akihisa T, Tamura T (1995) Some lupane-type triterpenes inhibit tumor promotion by 12-Otetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate in two-stage carcinogenesis in mouse skin. Phytomedicine 4:309–313. [CrossRef]

- Medeiros R, Otuki MF, Avellar MCW, Calixto JB (2007) Mechanisms underlying the inhibitory actions of the pentacyclic triterpene α-amyrin in the mouse skin inflammation induced by phorbol ester 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate. European Journal of Pharmacology 559:227–235. [CrossRef]

- Otuki MF, Vieira-Lima F, Malheiros A, Yunes RA, Calixto JB (2005) Topical antiinflammatory effects of the ether extract from Protium kleinii and Alpha amyrin pentacyclic triterpene. Eur J Pharmacol 507:253–9. [CrossRef]

- Bonesi M, Menichini F, Tundis R, Loizzo MR, Conforti F, Passalacqua NG, Statti GA, Menichini F (2010). Acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activity of Pinus species essential oils and their constituents. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry 25:622–628. [CrossRef]

- Piccinelli AC, Santos JA, Konkiewitz EC, Oesterreich SA, Formagio AS, Croda J, Ziff EB, Kassuya AL (2015). Antihyperalgesic and antidepressive actions of (R)-(+)-limonene, alpha-phellandrene, and essential oil from Schinus terebinthifolius fruits in a neuropathic pain model. Nutritional Neuroscience, 18(5), 217–224. [CrossRef]

- Lin JJ, Lin JH, Hsu SC, Weng SW, Huang YP, Tang NY, Lin JG, Chung JG (2013). Alpha- phellandrene promotes immune responses in normal mice through enhancing macrophage phagocytosis and natural killer cell activities. In Vivo 27(6), 809–814.

- Carson CF, Riley TV (1995). Antimicrobial activity of the major components of the essential oil of Melaleuca alternifolia. The Journal of Applied Bacteriology 78:264–269. [CrossRef]

- Fitsiou E, Anestopoulos I, Chlichlia K, Galanis A, Kourkoutas I, Panayiotidis MI, Pappa A (2016). Antioxidant and antiproliferative properties of the essential oils of Satureja thymbra and Satureja parnassica and their major constituents. Anticancer Research, 36(11), 5757–5763. [CrossRef]

- Govindarajan M, Rajeswary M, Hoti SL, Bhattacharyya A, Benelli G (2016). Eugenol, alpha-pinene and beta-caryophyllene from Plectranthus barbatus essential oil as eco-friendly larvicides against malaria, dengue and Japanese encephalitis mosquito vec-tors. Parasitology Research, 115(2), 807–815. [CrossRef]

- Varga ZV, Matyas C, Erdelyi K, Cinar R, Nieri D, Chicca A, Nemeth BT, Paloczi J, Lajtos T, Corey L, Hasko G, Gao B, Kunos G, Gertsch J, Parcher P, (2018). Beta-caryophyllene protects against alcoholic steatohepatitis by attenuating inflammation and metabolic dysregulation in mice. British Journal of Pharmacology 175:320-334. [CrossRef]

| % inhibition | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration | [5 µg/mL] | [10 µg/mL] | [20 µg/mL] | [30 µg/mL] | [40 µg/mL] |

| Resin | 9.86± 2.37 | 15.21±3.57 | 40.42± 2.11 | 48.6± 3.57 | 65.83± 8.53 |

| Volatile fraction | 12.96±2.09 | 17.64±3.23 | 24.23± 5.11 | 28.56± 5.50 | 37.43± 7.13 |

| Indomethacin | - | - | - | 48.16± 6.38 | - |

| Volatile fraction (supercrital CO2 extraction) | Resin (EtOAc) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Compounds | TR (min) | Relative Content (%)1 |

Molecular Formula |

Mass spectra Match (%)2 |

Compounds | TR (min) | Relative Content (%)1 |

Molecular Formula |

Mass spectra Match (%)2 |

| 1 | α-Phellandrene | 7.11 | 24.42 | C10H16 | 136 | α-Phellandrene | 6.873 | 5.38 | C10H16 | 136 |

| 2 | β-Phellandrene | 7.46 | 8.27 | C10H16 | 136 | m-Cymene | 7.189 | 4.37 | C10H14 | 134 |

| 3 | Carene | 7.23 | 0.18 | C10H16 | 136 | ψ-Limonene | 7.254 | 2.19 | C10H16 | 136 |

| 4 | p-Cymene | 7.72 | 6.72 | C10H14 | 134 | 4(10)-Thujen-3-ol | 9.928 | 0.98 | C10H16O | 134 |

| 5 | Terpinolene | 8.35 | 0.38 | C10H16 | 136 | exo-2-Hydroxycineole acetate | 11.623 | 2.36 | C12H20O3 | 126 |

| 6 | Thujone | 9.84 | 0.55 | C10H16O | 152 | p-Menthane | 11.806 | 0.85 | C10H16O2 | 135 |

| 7 | Carvone | 9.62 | 0.48 | C10H16O | 152 | Unnamed | 12.7 | 0.54 | ND | 207 |

| 8 | β-Copaene | 12.57 | 0.54 | C15H24 | 204 | Caryophyllene | 12.91 | 1.78 | C15H24 | 204 |

| 9 | β-Caryophyllene | 13.21 | 6.31 | C15H24 | 204 | p-Menthan-3-one | 13.015 | 0.39 | C10H16O2 | 207 |

| 10 | β-Caryophyllene oxide | 15.45 | 0.44 | C15H24O | 220 | Caryophyllene oxide | 14.973 | 0.55 | C15H24O | 205 |

| 11 | Bicyclosesquiphellandrene | 14.13 | 1.03 | C15H24 | 204 | α-Phellandrene, dimer | 17.272 | 1.12 | C20H32 | 136 |

| 12 | 1-Hydroxy-1,7-dimethyl-4-isopropyl-2,7-cyclodecadiene | 14.44 | 1.33 | C15H26O | 222 |

β-Amyrin |

35.9 |

10.41 |

C30H50O |

426 |

| 13 | Calamenene | 14.49 | 0.63 | C15H22 | 202 | 3-Epilupeol | 36.275 | 38.16 | C30H50O | 426 |

| 14 | Cubenol | 17.60 | 8.05 | C15H26O | 222 | α-Amyrin | 37.109 | 29.74 | C30H50O | 426 |

| 15 | α-Amyrin | 38.53 | 5.08 | C30H50O | 426 | 3-Epilupeol-acetate | 41.786 | 1.17 | C32H52O2 | 468 |

| 16 | β-Amyrin | 36.96 | 6.28 | C30H50O | 426 | |||||

| 17 | 3-Epilupeol | 38.09 | 18.77 | C30H50O | 426 | |||||

| 18 | 3-Epilupeol-acetate | 38.64 | 4.35 | C32H52O2 | 468 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).