1. Introduction

Cotton remains the dominant natural fiber in global textiles, valued for its comfort, breathability, and versatility. In woven fabric production, warp yarn preparation is critical to achieving high weaving efficiency and fabric quality. Sizing—the application of a thin film of natural or synthetic polymers such as starch, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), carboxymethylcellulose (CMC), or acrylic copolymers—enhances yarn strength, smoothness, and abrasion resistance, reducing warp breakage and loom stoppages during high-speed weaving [

1,

2]. By lowering inter-yarn friction and controlling hairiness, sizing improves weavability, fabric uniformity, and production efficiency [

3].

Following weaving, desizing is essential to remove these protective films and restore fiber absorbency, enabling uniform scouring, bleaching, dyeing, and finishing [

4]. Common desizing methods for cotton include enzymatic hydrolysis of starches, oxidative treatments, and alkaline steeping, selected according to the sizing agents used and desired process efficiency [

5,

6]. Effective desizing ensures even dye uptake, prevents residual stiffness, and maintains the desired handle of the finished fabric [

7].

Despite their technical necessity, conventional sizing and desizing are highly water-intensive and contribute significantly to textile effluent loads. Wet-processing operations in cotton mills consume up to 250–350 L of water per kilogram of fabric [

8], with desizing and scouring together responsible for as much as 50 % of the biological oxygen demand (BOD) in wastewater [

9]. Moreover, these stages can account for 50–80 % of the chemical oxygen demand (COD) in textile effluents, largely due to the discharge of non-biodegradable synthetic sizes such as PVA [

10,

11]. The resulting wastewater often contains high levels of suspended solids, residual chemicals, and auxiliaries, posing treatment and compliance challenges for mills [

12].

Yarn sizing, as described by Mondal [

13], remains a crucial preparatory step in textile manufacturing, designed to enhance yarn strength, abrasion resistance, and weaving efficiency. Building on this foundation, Taylor and Brunner [

14] point to the expanding role of green supercritical carbon dioxide (scCO

2) technologies in dyeing and finishing, noting their potential to transform sizing into a water-free, low-impact process. Reverchon [

15] demonstrates how supercritical media can modify polymer systems without leaving residual solvents — a principle that underpins modern scCO

2 textile applications.

Hasan and Dutta [

16] document the high water footprint and chemical load associated with conventional sizing, while Joshi et al. [

17] report substantial reductions in chemical use and energy demand when scCO

2 replaces aqueous finishing baths. Reviews by Abou Elmaaty et al. [

18] and Tadesse and Nierstrasz [

19] consolidate these findings, highlighting waterless coloration methods and dramatic decreases in effluent generation.

Pioneering applied work by Antony et al. [

20] demonstrated scCO

2-based sizing and desizing of cotton and polyester yarns using nonfluorous CO

2-philes, achieving uniform coating without loss of fiber integrity. Extending the concept, Khulbe and Matsuoka [

21] showed that scCO

2 could also be used to functionalize natural fibers. In a broader review, Eren et al. [

22] synthesize advances in scCO

2 dyeing, bleaching, and scouring, while a World Intellectual Property Organization patent [

23] describes an enzyme-assisted desizing route that is both energy-efficient and environmentally benign.

Recent studies have diversified the scope of scCO

2 applications. Yiğit et al. [

24] explore its use in cellulosic fiber production with closed-loop solvent recovery. Hassabo et al. [

25] catalogue functional finishing methods — from antimicrobial to flame-retardant treatments — achievable without water. A series of investigations by Ghanayem and Okubayashi demonstrate its versatility: water-free dewaxing of grey cotton fabrics [

26], electron-beam-assisted wettability enhancement [

27], and coloration of pretreated fabrics [

28]. Complementary work by Schmidt-Przewozna and Rój [

29] employs natural madder extract in scCO

2 dyeing, while Abd-Elaal et al. [

30] use the medium to apply durable, water-resistant finishes.

Sustainability perspectives have widened further. Tayebwa [

31] applies scCO

2 to extract dyes from post-consumer textiles, advancing circular-economy strategies. Kazarian [

32] offers thermodynamic and kinetic models for scCO

2–polymer interactions, and Sawada et al. [

33] demonstrate that scCO

2 surface modification improves polyester dye ability without conventional wet processing. Finally, Eren et al. [

34] outline comprehensive zero-water textile processing protocols under scCO

2, framing a roadmap for industrial adoption.

Despite these promising developments, existing studies offer limited optimization of process parameters and lack direct performance comparisons with conventional starch-based systems. This study addresses that gap by developing a scCO2-based sizing and desizing protocol for cotton yarns using cellulose acetate as the sizing agent and acetone as a co-solvent. We systematically vary pressure, temperature, and co-solvent ratio to achieve target add-on levels, assess uniformity via weight gain distribution and frictional performance, benchmark mechanical properties against industry standards, and quantify solvent recovery to evaluate environmental benefits. Through this comprehensive evaluation, we aim to establish scCO2-based sizing as a sustainable, high-performance alternative to water and organic solvent systems, paving the way for eco-friendly textile manufacturing

2. Experiments

2.1. Materials

Un-sized cotton yarn (20/1) was obtained from IZAWA TOWEL Ltd., Japan. Cellulose acetate, the sizing agent, was procured from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received. Two types of cellulose acetate with different viscosities were provided by Daicel Corporation. The structural formula is shown in

Figure 1, and the details are presented in

Table 1. Acetone, serving as the co-solvent (99.8% purity), was purchased from Nacalai Tesque, Inc., Kyoto, Japan. Liquefied carbon dioxide (99.5% purity) was supplied by Kind Gas Co., Ltd.

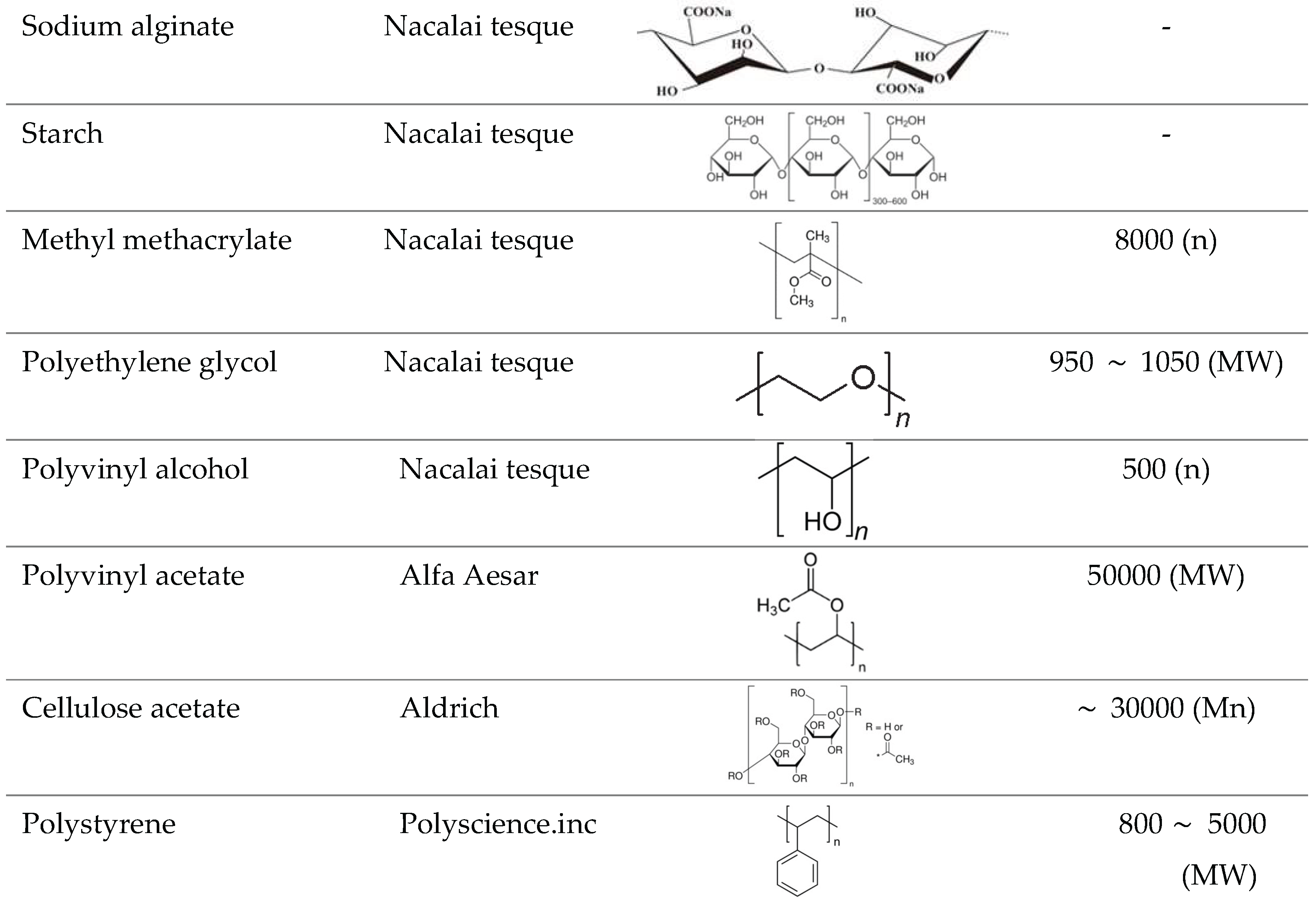

For the solubility test, eight types of polymers were used: sodium alginate, starch, methyl methacrylate, polyethylene glycol, polyvinyl alcohol, polyvinyl acetate, cellulose acetate, and polystyrene. These polymers are hydrophobic and have structures similar to that of conventionally used starch paste. Details of each polymer are provided in

Table 2. The carbon dioxide supply source was a liquefied carbon dioxide cylinder (Kind Gas Co., Ltd., purity 99.5%). A cylindrical glass filter (ADVANTEC 88R) was also employed in the test.

2.2. Equipment

For the solubility test with supercritical carbon dioxide, a high-pressure vessel (JASCO EV-3-50-2/4, capacity 50 ml) was set in a JASCO oven SCF-Sro, and a JASCO PU-2086 intelligent HPLC pump was used as a pump to send carbon dioxide to the supercritical cell. A cooling head was attached to the carbon dioxide pump, and carbon dioxide was kept in liquid phase by passing a refrigerant below -10℃. In addition, a fully automatic pressure regulating valve BP-2080 from JASCO was attached to the pressure release section, and the pressure inside the column and the speed of carbon dioxide release were kept constant

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Solubility test

One gram of polymer was weighed and placed in a cylindrical glass filter. The high-pressure vessel was preheated to 100°C, and the sample was subsequently placed inside the vessel. Pressure was then applied using a liquid delivery pump. The supercritical treatment conditions included a pressure of 20 MPa, a temperature of 100°C, and a duration of 180 minutes in a batch system, with continuous stirring provided by a magnetic stirrer within the column. Upon completion of the supercritical treatment, the valve was opened, and the pressure was released to atmospheric levels. The sample was then removed and reweighed.

2.3.2. Sizing

0.175 g of unseized cotton yarn was weighed, then dried at 105°C for 120 minutes, and reweighed. The high-pressure vessel was preheated to 40°C, and cellulose acetate along with acetone as a co-solvent were introduced into the vessel. The cotton yarn was placed inside the high-pressure vessel, isolated by a wire stand to avoid contact with the stirrer. The vessel was then sealed and pressurized by pumping liquid carbon dioxide from an intelligent pump. The supercritical treatment conditions were set at 40°C and 10 MPa, as well as 100°C and 20 MPa, with the treatment time being 30 minutes in a batch system, where stirring was conducted inside the column by a magnetic stirrer. Following the supercritical treatment, the pressure was released to atmospheric pressure at a controlled rate of 0.1 MPa/min. After depressurization, the sample was removed and dried again at 105°C for 120 minutes, then finally weighed.

2.3.3. Desizing

2.3.3.1. Batch Method

The high-pressure vessel was preheated to 40°C before placing the sized cotton yarn inside, isolating it with a wire stand to prevent contact with the stirrer. Subsequently, 10 mol% acetone was added as a co-solvent. The vessel was sealed, and liquid carbon dioxide was introduced at a specified flow rate using an intelligent pump to pressurize the vessel. The supercritical treatment conditions were maintained at 10 MPa pressure, 40°C temperature, for a duration of 60 minutes in a batch system, with stirring achieved by a magnetic stirrer inside the column. After completing the supercritical treatment, the valve was opened to release the pressure to atmospheric levels. The sample was then removed and left to stand for 120 minutes at 105°C, followed by drying at 37°C and weighing. This procedure was repeated five times for the same sample.

2.3.3.2. Continues Method

The high-pressure vessel was preheated, and the sized cotton yarn was placed inside, isolated with a wire stand to prevent contact with the stirrer. The vessel was then sealed, and the automatic control valve was set to the specified pressure. Liquid carbon dioxide was delivered from the intelligent pump at a specified flow rate, with the start of acetone delivery defined as the point when the pressure in the high-pressure column reached the level set by the automatic control valve. Supercritical treatment commenced once the control valve began to release pressure. Following supercritical treatment, the pressure was rapidly released, and the sample was removed. The sample was then left at 105°C to stand, subsequently dried at 37°C, and weighed. The supercritical treatment was performed under the following conditions:

(i) Temperature and Pressure:

Temperature and Pressure: (40°C, 10 MPa), (40°C, 20 MPa), and (100°C, 10 MPa).

The flow rate of CO2 was 1 ml/min, and acetone was 0.2 ml/min.

Treatment duration was 300 minutes.

(ii) Mixing: The wire stand was removed to allow the cotton thread to contact the stirrer. Ten stainless steel metal balls (1/4 inch in size) were placed in the high-pressure vessel to facilitate further stirring and size removal. The treatment conditions were 40°C and 10 MPa, with CO2 flowing at 1 ml/min and acetone at 0.2 ml/min for 300 minutes.

(iii) Flow Velocity: The flow rates and supercritical treatment times were set as follows:

(CO2 5 ml/min, acetone 1 ml/min, 60 min),

(CO2 1 ml/min, acetone 0.2 ml/min, 300 min),

(CO2 0.5 ml/min, acetone 0.1 ml/min, 600 min).

The temperature and pressure conditions were consistently maintained at 40°C and 10 MPa.

2.3.4. Analysis

2.3.4.1. Evaluation of Solubility of Hydrophobic Polymers

The solubility of the polymer was determined by weighing the glass filter containing the sizing agent both before and after the supercritical treatment. The weight of the glass filter was subtracted from the weight of the polymer, and the solubility was calculated using equation (1):

(1)

Where W1 is the weight of the polymer before treatment and W2 is the weight of the polymer after treatment.

2.3.4.2. Adhesion Rate of Sizing Agent

The adhesion rate of the sizing agent was determined by measuring the weight change of the cotton yarn before and after the supercritical treatment. This value was calculated using equation (2):

(2)

Where is the weight of the cotton yarn before sizing treatment and W1 is the weight of the cotton yarn after sizing treatment.

2.3.4.3. Desizing Rate

Where

is the weight of the cotton yarn before sizing treatment,

W1 is the weight of the cotton yarn after sizing treatment, and

W2 is the weight of the cotton yarn after desizing treatment.

2.3.4.4. Tensile Strength

Tensile testing of the sized cotton yarns was conducted using a universal testing machine (AGS-J, Shimadzu Co., Japan) at room temprature. A constant rate of extension of 200 mm/min was applied with a 1 kN load cell, following the Japanese Industrial Standard JIS L 1096:2010, which corresponds to ISO 13934-1:1999. The test specimen length was 200 mm. The tensile behavior of the yarns was evaluated in terms of tenacity (cN/tex), calculated as the ratio of breaking force to linear density using equation (4):

(4)

Where F is the breaking force in (cN), and L is the Linear Density (tex).

Each test was repeated ten times, and the values were reported.

2.3.4.5. FE-SEM Analysis

The surface morphology of the cotton yarn was observed using a field-emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, JSM-7001F, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The fabric surface was pre-coated with 75 Å Au for 1 min using fine coat sputtering (FINE COAT JFC-1100E, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

2.3.4.6. Friction Test

To examine the abrasion resistance of the yarn, the mechanical properties of both sized and un-sized yarns were analyzed prior to and following the abrasion process. The abrasion process involved the use of abrasive paper (Cw-C-P1000) mounted on a roller, which was systematically brought into contact with the yarn fibers. The roller was oscillated in a back-and-forth motion for 100 cycles.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Solubility of Sizing Agent

The solubility results of various sizing agents in supercritical carbon dioxide (scCO

2) are shown in

Table 3. Cellulose acetate demonstrated the highest solubility, reaching 19.5%, while other polymers showed minimal solubility in supercritical carbon dioxide—a nearly non-polar solvent. The reduced solubility of polymers with large molecular weights is likely due to their structural characteristics. However, cellulose acetate, despite its high molecular weight, exhibited significant solubility, which is largely attributed to its acetyl groups in the side chains. In contrast, starch has a similar structure but contains numerous hydroxyl groups in its side chains, making it highly polar. The acetylation of hydroxyl groups in cellulose acetate, resulting in an increased number of acetyl groups and reduced polarity, is believed to enhance its solubility in the non-polar supercritical carbon dioxide.

3.2. Rate of Sizing

3.2.1. Effects of Temperature and Pressure

Table 4 presents the adhesion rate of the sizing agent cellulose acetate when applied using supercritical carbon dioxide (ScCO

2). The adhesion rate was determined using equation (2), providing insight into the solubility and deposition behavior of cellulose acetate under different temperature and pressure conditions.

The adhesion rate of cellulose acetate was measured under two distinct conditions 40°C, 10 MPa and 100°C, 20 MPa. Despite a significant increase in temperature and pressure, the adhesion rate remained constant at 1.2%. The consistency of adhesion suggests that raising temperature and pressure within this range does not significantly improve cellulose acetate’s solubility, since its acetylated structure already achieves optimal interaction with supercritical carbon dioxide (scCO2).

3.2.2. Effect of Acetone as a Co-Solvents on Sizing Paste Solubility

The data shown in

Table 4 demonstrates how the presence and concentration of acetone influence the sizing rate (S%), which reflects adhesion and solubility behavior in the supercritical carbon dioxide.

3.2.3. Influence of Adhesive Quantity on Adhesion Performance

As summarized in

Table 4, the adhesion behavior of cellulose acetate applied to cotton yarn under supercritical carbon dioxide (scCO

2) conditions was significantly affected by the quantity of adhesive.

Application of 1.000 g of cellulose acetate resulted in the highest observed adhesion rate of 62.6%, indicating efficient surface coverage and interaction between the sizing agent and the fiber structure. In contrast, reducing the adhesive quantity to 0.326 g produced a markedly lower adhesion rate of 10.0%, which corresponds to adhesion levels typically achieved with approximately 3% starch paste applied through conventional sizing methods.

Starch paste generally exhibits higher viscosity compared to synthetic alternatives such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and acrylic-based sizing agents. The cellulose acetate used in this study possesses lower viscosity, which enables fine dispersion and controlled deposition under scCO2 conditions.

Further analysis revealed that adjusting the amount of acetone—used here as a co-solvent—had a direct impact on adhesion efficiency. When the acetone concentration was reduced, adhesion rates decreased even at constant cellulose acetate dosage. These findings suggest that an optimal acetone concentration of 10 mol% is necessary to achieve consistent adhesion performance, likely due to its role in promoting solubility and enhancing interfacial interactions during scCO2 processing.

3.2.4. Effect of Polymer Molecular Weight

Table 5 presents the adhesion rates of cellulose acetate with varying viscosities under supercritical carbon dioxide (scCO

2) conditions, using acetone as a co-solvent. The results demonstrate a clear dependence of adhesion performance on the polymer’s molecular weight and co-solvent concentration.

When 10 mol% acetone was added to the low-viscosity cellulose acetate (Daicel L-20, 50 × 10−3 Pa·s), the adhesion rate reached 24.3%. In contrast, the high-viscosity variant (Daicel L-70, 140 × 10−3 Pa·s) exhibited a significantly lower adhesion rate of 4.5% under the same conditions. This disparity is attributed to the enhanced solubility of the lower molecular weight L-20 in scCO2, facilitating better interaction with the cotton substrate.

To further investigate the influence of acetone concentration, the co-solvent level was reduced to 7 mol%. Under these conditions, the adhesion rates decreased markedly across all cellulose acetate samples: Aldrich yielded 6.9%, L-20 yielded 7.2%, and L-70 yielded 4.9%. These findings suggest that 10 mol% acetone is a more effective concentration for promoting adhesion, regardless of polymer viscosity.

3.3. Rate of Desizing

Table 6 and

Table 7 present the desizing performance of cotton yarn treated with supercritical carbon dioxide (scCO

2) using batch and continuous methods, respectively. The desizing rate was calculated according to Equation (3)

3.3.1. Comparison Between Batch and Continuous Desizing Methods

In the batch method (

Table 6), negligible mass loss was observed after the first treatment. However, subsequent treatments showed a marked increase in desizing efficiency, culminating in a maximum removal rate of 82.4% after the fifth cycle. Despite employing the same conditions as the sizing test described earlier, complete removal of the sizing agent was not achieved. This limitation is likely attributed to the strong intermolecular interactions between cellulose and cellulose acetate within the cotton yarn, which hinder the solubility of cellulose acetate in scCO

2 during initial treatments.

In contrast, the continuous method (

Table 7, No. 2), which replicated the cumulative conditions of the five batch treatments (temperature, pressure, and duration), yielded a lower removal rate of 43.9%. This discrepancy may be due to insufficient mechanical agitation in the continuous setup, resulting in premature CO

2 flow before effective dissolution of cellulose acetate occurred.

3.3.2. Influence of Temperature and Pressure

To evaluate the effects of temperature and pressure on desizing efficiency, experiments were conducted under varied conditions (

Table 7, Nos. 2–4). Increasing the pressure from 10 MPa (No. 2) to 20 MPa (No. 3) did not significantly enhance the removal rate (43.9% vs. 38.3%). However, elevating the temperature to 100 °C (No. 4) drastically reduced the removal rate to 2.24%, indicating minimal solubility of cellulose acetate under these conditions. These results suggest that cellulose acetate exhibits higher solubility in scCO

2 at lower temperatures, while pressure variations within the tested range (10–20 MPa) have limited impact on solubility.

3.3.3. Role of Physical Contact and Mechanical Agitation

The effect of physical contact during desizing was investigated by modifying the experimental setup. In No. 5, the wire stand was removed, allowing direct contact between the cotton yarn and the stirrer. This adjustment significantly increased the removal rate to 72.4%. Further enhancement was achieved in No. 6 by introducing stainless steel balls (1/4 inch diameter) into the high-pressure vessel, resulting in a removal rate of 81.1%. These findings underscore the importance of mechanical agitation and physical impact in promoting the dissolution and removal of cellulose acetate in scCO2.

3.3.4. Effect of Flow Rate and Treatment Duration

The influence of flow dynamics was assessed by varying CO

2 and acetone flow rates and treatment durations (

Table 7, Nos. 1, 2, and 7). A short treatment time (60 min) combined with a high CO

2 flow rate (5 ml/min) in No. 1 yielded a low removal rate of 17.7%. In contrast, extending the treatment time to 300 min and reducing the flow rate to 1 ml/min in No. 2 improved the removal rate to 43.9%. These results indicate that cellulose acetate, being a polymer with slow dissolution kinetics, requires prolonged exposure and reduced flow velocity for effective desizing.

In No. 7, the treatment time was further extended to 600 min, with CO2 and acetone flow rates reduced to 0.5 ml/min and 0.1 ml/min, respectively. Despite these adjustments, the removal rate (75.9%) was slightly lower than that of No. 6 (81.1%), suggesting that while extended duration and slower flow enhance solubility, the mechanical impact from metal balls remains a dominant factor in desizing efficiency.

3.4. Tensile Strength and Friction Characteristics

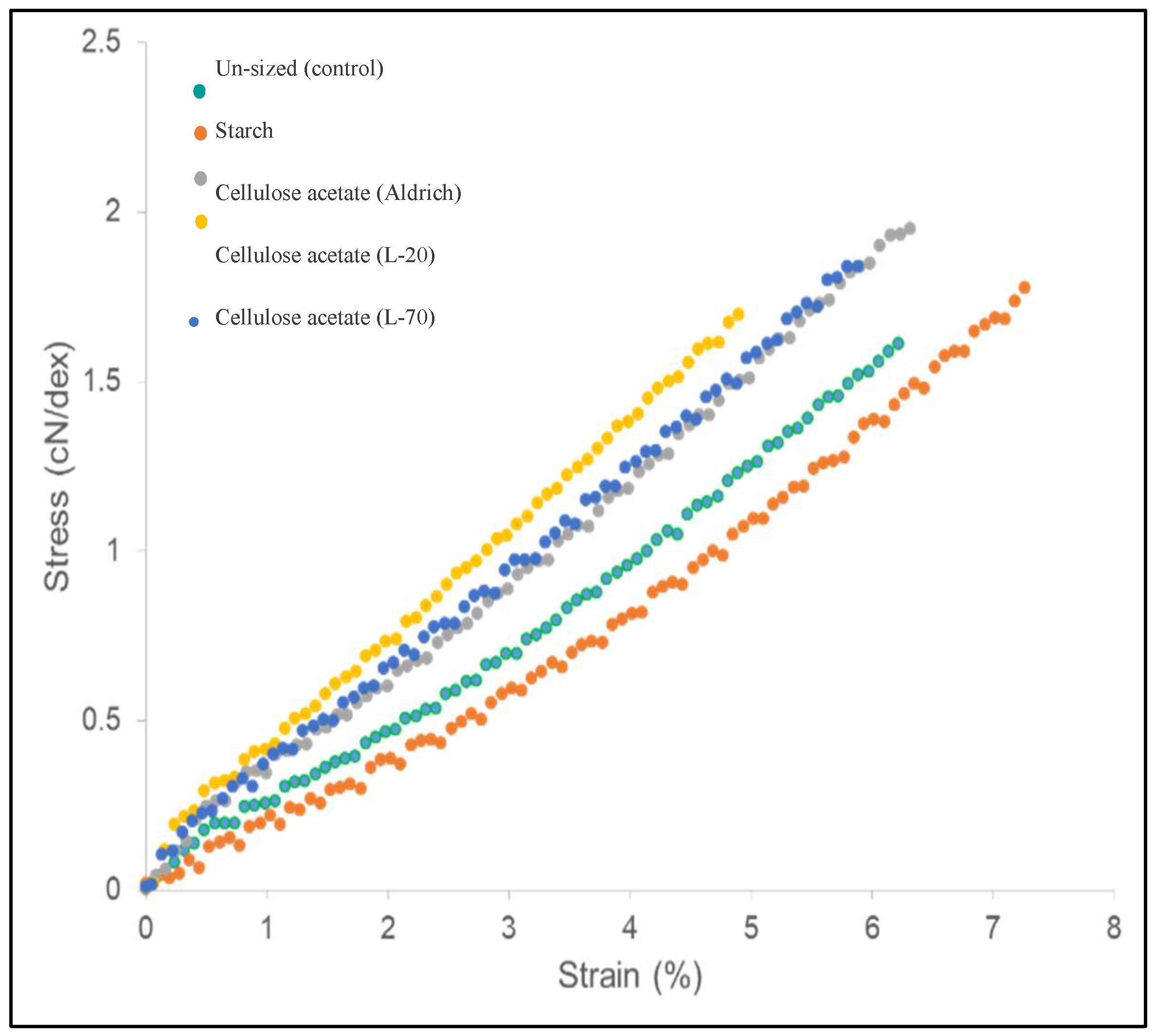

As shown in

Table 8, under standard (no-friction) conditions, all sizing agents improve tensile behavior relative to the un-sized yarn. Un-sized yarn exhibits an average strain of 5.95 % and strength of 1.63 cN/dtex. 3 % starch raises strain to 7.46 % and strength to 1.75 cN/dtex, reflecting better fiber cohesion. Cellulose acetate (CA) grades deliver even higher initial strength—up to 1.94 cN/dtex for Aldrich Cellulose acetate (CA) (17.7 % add-on) and 1.83 cN/dtex for L-70 (17.8 % add-on)—with moderate gains in extensibility (strain ~5–6 %). These trends confirm that higher add-on and film-forming polymers Cellulose acetate (CA) enhance inter-fiber bonding more effectively than a small starch coating.

As reflected in

Figure 2, cellulose acetate (CA) (especially Aldrich and L-70) reaches higher peak stress than starch and control, while starch extends to higher strain before failure. The initial slope (Young’s modulus) is steeper for cellulose acetate (CA) treatments, indicating higher stiffness; starch shows the lowest initial slope, consistent with greater compliance.

After 100 abrasion cycles, the starch-sized yarn’s tensile strength decreased from 1.75 to 0.81 cN/dtex (−53.7 %) and its elongation from 7.46 % to 3.08 % (−58.7 %). The Aldrich cellulose acetate sample showed a smaller decline, with strength dropping from 1.94 to 1.11 cN/dtex (−42.8 %) and elongation from 6.13 % to 3.17 % (−48.3 %). The more pronounced losses in the starch sample indicate the lower abrasion resistance of its film. By contrast, cellulose acetate preserved a greater proportion of its initial strength, reflecting stronger adhesion and greater film durability. Post-abrasion, Aldrich cellulose acetate retained 11.8 % S (a −33.3 % change from the initial 17.7 %), confirming partial coating loss. Elevated standard deviations point to non-uniform film retention and possible localized defects. The starch-sized yarn’s nominal S % remained at 3 %, likely due to the detection limit of the gravimetric method, despite substantial mechanical degradation.

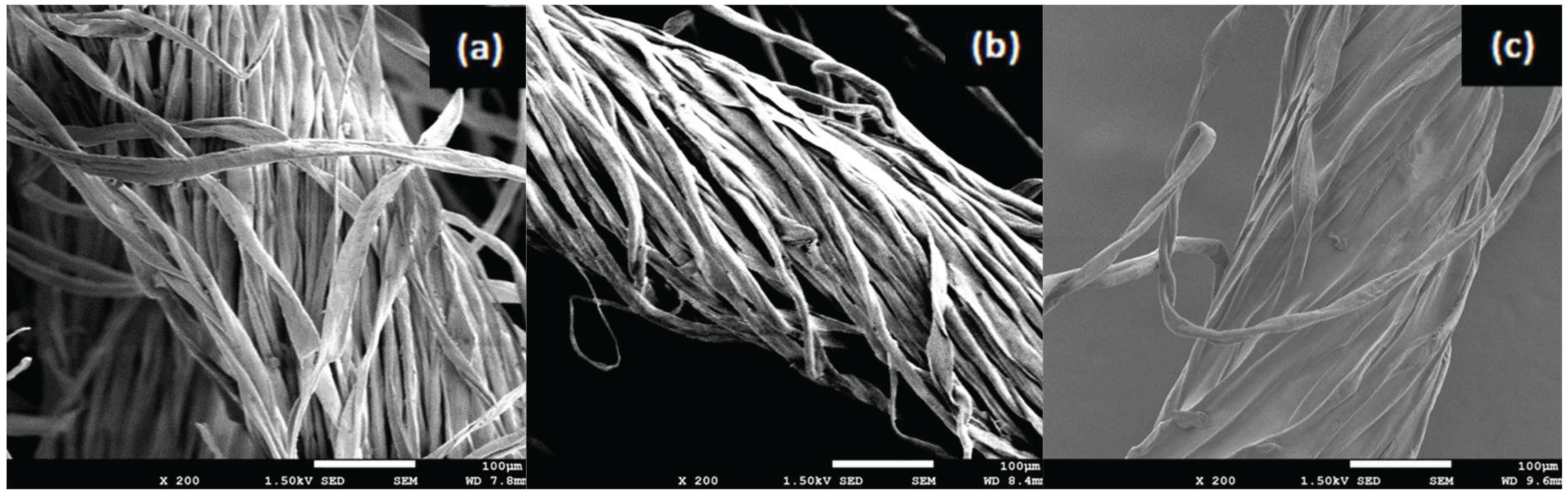

3.5. Yarn Surface Characterization by FE-SEM

Figure 3-a and (3-b) reveal that the un-sized cotton and the conventionally 3 % starch sized cotton yarn exhibit virtually identical fiber morphologies. Individual fibrils remain exposed, inter-fiber voids are clearly visible, and there is no continuous film or agglomeration on the surface. This confirms that at low add-on and in a liquid medium, starch particles largely remain in suspension or loosely in the yarn’s exterior gaps without true adhesion.

In contrast, Figure (3-c) shows cotton yarn treated with 10% cellulose acetate via supercritical CO2, where a uniform, continuous coating is evident not only on the exterior but deep within the fiber bundle. The paste infiltrates lumens and inter-fibrillar spaces, masking the natural fibrillar texture and filling micro voids. Such internal deposition highlights a marked change in surface topology, with smoother regions and fewer open channels compared to the starch-sized sample.

4. Conclusion

In this study, we explored replacing water and organic solvents with supercritical carbon dioxide to provide a sustainable route for cotton yarn sizing and desizing. By screening various polymers, we identified cellulose acetate as highly soluble in scCO2—an outcome attributed to its reduced polarity from acetylation.

Sizing trials with cellulose acetate, aided by acetone as a co-solvent produced a 10 % add-on comparable to that of conventional starch-sized yarns. Lower-molecular-weight grades showed superior solubility and adhesion, and tensile tests confirmed that scCO2-sized threads exceed the strength of starch-treated equivalents.

Desizing experiments demonstrated that batch processing removes more size than continuous flow, though optimizing temperature and introducing metal balls markedly improved continuous-mode removal. These findings highlight the importance of physical agitation and low-temperature solubility in efficient scCO2 desizing.

Overall, this work establishes a practical foundation for eco-friendly yarn processing using supercritical CO2 and cellulose acetate. Future research should explore alternative polymers and scale-up strategies to drive industrial adoption of this water-free sizing and desizing technology.

5. Patent

Title: Method for applying sizing agent to textile products, method for manufacturing sizing-coated textile products, method for removing sizing agent from sizing-coated textile products, and method for manufacturing textile products from sizing-coated textile products.

Publication number: JP2021-121700 (P2021-121700A)

Publication Date: August 26, 2021

Applicants: Izawa Towel Co., Ltd. (Tokyo), National University Corporation Kyoto Institute of Technology (Kyoto)

Inventors: Shoji IZAWA (Tokyo), Satoko OKUBAYASHI (Kyoto)

Issuing Authority: Japan Patent Office (JP)

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Satoko Okubayashi.; methodology, Ito Osamu.; software, Ito Osamu.; validation, Satoko Okubayashi.; formal analysis, Ito Osamu.; investigation, Ito Osamu , Satoko Okubayashi, Masuda Yoshiharu , Heba Mehany Ghanayem.; resources, Satoko Okubayashi , Masuda Yoshiharu.; data curation, Ito Osamu.; writing—original draft preparation, Heba Mehany Ghanayem; writing—review and editing, Ito Osamu , Satoko Okubayashi, Heba Mehany Ghanayem; visualization, Ito Osamu , Satoko Okubayashi.; supervision, Satoko Okubayashi; project administration, Satoko Okubayashi , Masuda Yoshiharu.; funding acquisition, Masuda Yoshiharu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Izawa Towel Co., LTD.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

CA Cellulose Acetate

CMC Carboxymethylcellulose

D% Desizing rate

FE-SEM Field-emission Scanning electron microscope

PVA Polyvinyl alcohol

S% Sizing rate

ScCO2 Supercritical Carbon dioxide

SD Standard deviation

References

- Lord, P. R. , & Mohamed, M. H. (2020). Weaving: Conversion of yarn to fabric. Woodhead Publishing.

- Lewin, M. , & Pearce, E. M. (2019). Handbook of fiber chemistry (3rd ed.). CRC Press.

- Talukder, M. (2014). Sizing of yarns and its impact on weaving efficiency. Textile Research Journal, 84, 34-35. [CrossRef]

- Trotman, E. R. (2020). Dyeing and chemical technology of textile fibres (6th ed.). Wiley.

- Maurya, N. K. , Tiwari, A. K., Rajput, S., & Singh, S. (2017). Enzymatic desizing of cotton fabrics: A review. Carbohydrate Polymers, 173, 645–660. [CrossRef]

- Shenai, V. A. (1997). Technology of textile processing: Preparatory processes Sevak Publications.

- Gulrajani, M. L. (2017). Preparation of textile materials. New Age International.

- Khatri, A. , & White, M. (2015). Environmental impact of textile wet processing. Journal of Cleaner Production, 87, 50–57. [CrossRef]

- Hasanbeigi, A. , & Price, L. (2012). A technical review of emerging technologies for textile wet processing. Journal of Cleaner Production, 26, 64–74. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. M. , Sultana, S., & Rahman, M. M. (2017). Textile wastewater characterization and treatment: A review. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 5(5), 6264–6281. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R. , Roy, R., & Burton, K. (2010). Impact of polyvinyl alcohol from textile effluent. Water Research,. [CrossRef]

- Correia, V. M. , Stephenson, T., & Judd, S. J. (1994). Characterisation of textile wastewaters. Environmental Technology, 15(10), 917–929. [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M. I. H. (2014). Advances in cotton textile processing. WPI Publishing.

- Taylor, J. , & Brunner, P. (2016). Green supercritical carbon dioxide technologies in textile processing. Journal of Supercritical Fluids, 110, 240–255. [CrossRef]

- Reverchon, E. (1999). Supercritical fluid applications to food processing. Food Science and Technology International, 5(4), 299–312. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M. , & Dutta, H. (2018). Environmental impact of textile sizing: A review. Journal of Textile Engineering, 64(2), 57–66. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M. , Ghosh, S., & Prasad, R. (2015). Energy and chemical savings in textile finishing using supercritical carbon dioxide. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy, 17(5), 1301–1310. [CrossRef]

- Abou Elmaaty, T. M. , Abdelghaffar, R. A., Rehan, M., & Abdelaziz, E. A. (2019). Waterless coloration of textiles using supercritical carbon dioxide. Journal of Cleaner Production, 210, 1433–1445. [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, M. , & Nierstrasz, V. A. (2014). Waterless textile coloration. Coloration Technology, 130(6), 361–373. [CrossRef]

- Antony, M. , Sakthivel, M., Raghavendran, N., Kumar, R., & Subramanian, B. (2018). Sizing and desizing of cotton and polyester yarns using liquid and supercritical carbon dioxide with nonfluorous CO2-philes as size compounds. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 6(3), 3724–3733. [CrossRef]

- Khulbe, K. C. , & Matsuoka, H. (2012). Functionalization of natural fibers using supercritical carbon dioxide. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 125(2), 1234–1242. [CrossRef]

- Eren, H. A. , Yiğit, E., Eren, S., & Avinc, O. (2016). Advances in supercritical carbon dioxide textile processing. Journal of Supercritical Fluids, 107, 140–150. [CrossRef]

- World Intellectual Property Organization. (2017). Enzyme-assisted desizing process in supercritical carbon dioxide, (WO2017135792A1). https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=WO2017135792.

- Yiğit, E. , Akarsu Özenç, D., & Eren, H. A. (2018). Closed-loop solvent recovery in supercritical carbon dioxide processing of cellulosic fibers. Journal of Cleaner Production, 198, 1352–1360. [CrossRef]

- Hassabo, A. G. , El-Sayed, H., Ragheb, A. A., & Mohamed, A. L. (2020). Functional finishing of textiles using supercritical carbon dioxide. Journal of Industrial Textiles, 50(8), 1195–1218. [CrossRef]

- Ghanayem, H. M. , & Okubayashi, S. (2021). Water-free dewaxing of grey cotton fabric using supercritical carbon dioxide. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids, 174, 105264. [CrossRef]

- Ghanayem, H. M. , & Okubayashi, S. 2022). Improvement of water wettability of gray cotton fabric using electron beam irradiation and supercritical carbon dioxide. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids, 181, 105506. [CrossRef]

- Ghanayem, H. M. , & Okubayashi, S. (2023). Coloration of gray cotton fabric pre-treated with electron beam irradiation and supercritical carbon dioxide. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids, 200, 105974.

- Schmidt-Przewozna, K. , & Rój, E. (2014). Dyeing of textiles with natural madder extract in supercritical carbon dioxide. Fibres & Textiles in Eastern Europe, 22(4), 101–106.

- Abd-Elaal, A. A. , Abou-Elmaaty, T. M., Rehan, M., & Abdelaziz, E. A. (2021). Application of durable water-repellent finishes using supercritical carbon dioxide. Journal of Industrial Textiles, 51(10), 1520–1538, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayebwa, J. B. (2020). Extraction of dyes from post-consumer textiles using supercritical carbon dioxide. Waste Management, 102, 391–399. [CrossRef]

- Kazarian, S. G. (2000). Polymer processing with supercritical fluids. Polymer Science Series C, 42(1), 78–101. [CrossRef]

- Sawada, H. & Okubayashi, M. (2017). Improvement of polyester dyeability by surface modification in supercritical carbon dioxide. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 134(12), 44678. [CrossRef]

- Eren, H. A. , Yiğit, E., Eren, S., & Avinc, O. (2019). Zero-water textile processing protocols under supercritical carbon dioxide. Journal of Cleaner Production, 236, 117707. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).