Submitted:

08 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Design, Participants, and Procedure

Measures

Statistical Analysis

Sociodemographic Characteristics

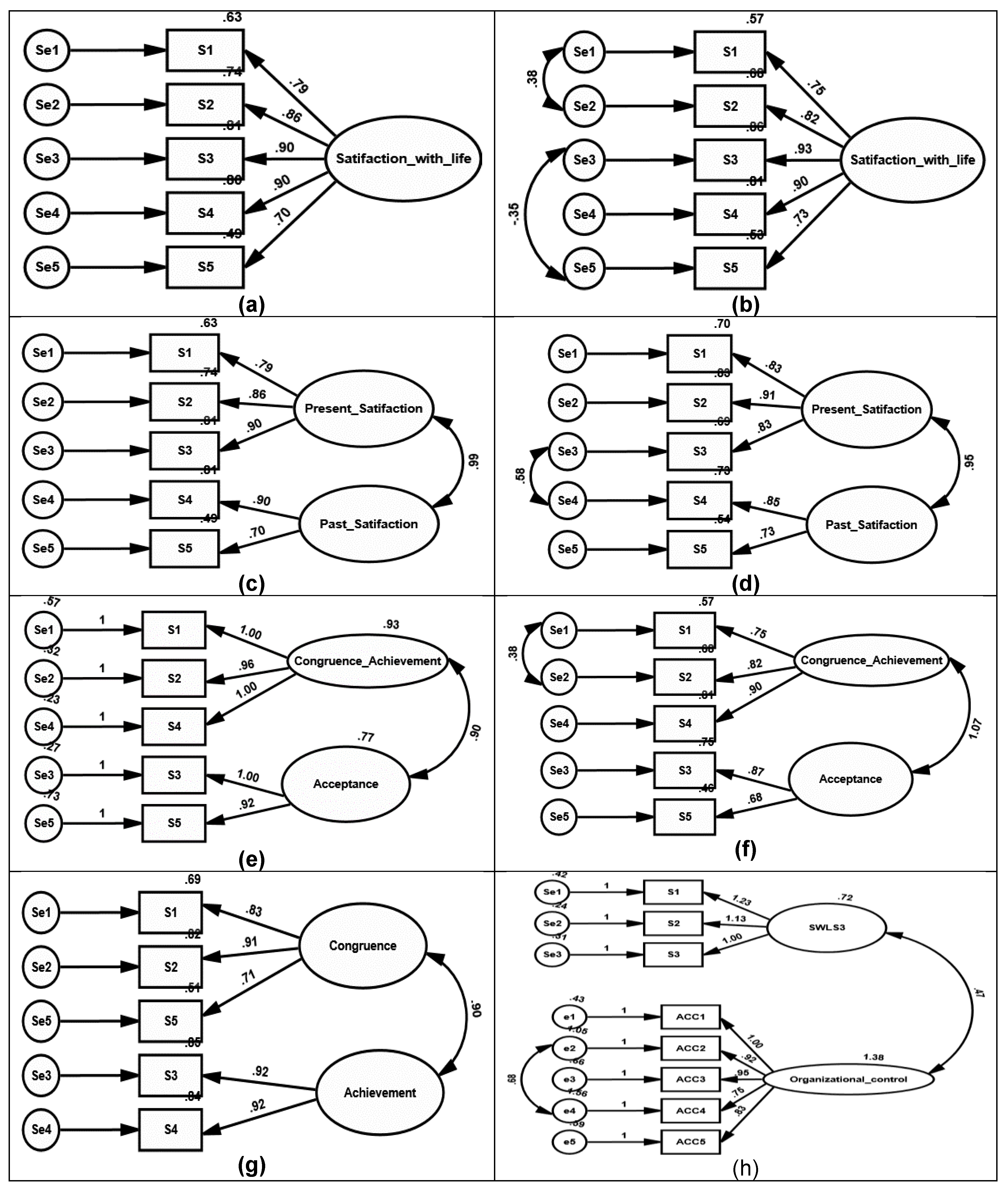

Factor Structure of the SLWS

Measurement Invariance of the SLWS

Convergent and Discriminant Validity of the SLWS

Internal Consistency, Predictive Validity, and Criterion Validity of the SLWS

Discussion

Strength, Implications, and Limitations

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Şimşek, Ö.F. , Happiness Revisited: Ontological Well-Being as a Theory-Based Construct of Subjective Well-Being. Journal of Happiness Studies 2009, 10, 505–522. [Google Scholar]

- Lingán-Huamán, S.K.; et al. , The satisfaction with life scale and the well-being index WHO-5 in young Peruvians: a network analysis. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 2024, 29, 2331586. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhoutte, B. , The Multidimensional Structure of Subjective Well-Being In Later Life. Journal of Population Ageing 2014, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyadjieva, P. and P. Ilieva-Trichkova, IS THERE ANYTHING BEYOND HAPPINESS? A COMPARATIVE EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVE TOWARDS THE MULTI-DIMENSIONAL CHARACTER OF SUBJECTIVE WELL-BEING. Sociological Problems 2022, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Sarriera, J.C. and L.M. Bedin, A Multidimensional Approach to Well-Being, in Psychosocial Well-being of Children and Adolescents in Latin America: Evidence-based Interventions, J.C. Sarriera and L.M. Bedin, Editors. 2017, Springer International Publishing: Cham. 3-26.

- Steckermeier, L.C. The Value of Autonomy for the Good Life. An Empirical Investigation of Autonomy and Life Satisfaction in Europe. Social Indicators Research 2021, 154, 693–723. [Google Scholar]

- Paloma, V.; et al. , Determinants of Life Satisfaction of Economic Migrants Coming from Developing Countries to Countries with Very High Human Development: a Systematic Review. Applied Research in Quality of Life 2021, 16, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárcaba, A. R. Arrondo, and E. González, Does good local governance improve subjective well-being? European Research on Management and Business Economics 2022, 28, 100192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, M. A. Grimes, Sustainability and wellbeing: the dynamic relationship between subjective wellbeing and sustainability indicators. Environment and Development Economics 2021, 27, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrington-Leigh, C.P. , Life satisfaction and sustainability: a policy framework. SN Social Sciences 2021, 1, 176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; et al. , The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J Pers Assess 1985, 49, 71–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swami, V.; et al. , Life satisfaction around the world: Measurement invariance of the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) across 65 nations, 40 languages, gender identities, and age groups. PLoS One 2025, 20, e0313107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oishi, S. , The concept of life satisfaction across cultures: An IRT analysis. Journal of Research in Personality 2006, 40, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Vergara, J.; et al. , New Psychometric Evidence of the Life Satisfaction Scale in Older Adults: An Exploratory Graph Analysis Approach. Geriatrics (Basel) 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emerson, S.D. Guhn, and A.M. Gadermann, Measurement invariance of the Satisfaction with Life Scale: reviewing three decades of research. Quality of Life Research 2017, 26, 2251–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; et al. , Measurement Invariance of the Satisfaction With Life Scale Across 26 Countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 2017, 48, 560–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slocum-Gori, S.L.; et al. , A Note on the Dimensionality of Quality of Life Scales: An Illustration with the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS). Social Indicators Research 2009, 92, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; et al. , The Arabic Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) and its three-item version: Factor structure and measurement invariance among university students. Acta Psychologica 2025, 255, 104867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultell, D. and J. Petter Gustavsson, A psychometric evaluation of the Satisfaction with Life Scale in a Swedish nationwide sample of university students. Personality and Individual Differences 2008, 44, 1070–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clench-Aas, J.; et al. , Dimensionality and measurement invariance in the Satisfaction with Life Scale in Norway. Qual Life Res 2011, 20, 1307–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzeszutek, M. Szyszka, and S. Okoń, Personality and Risk-Perception Profiles with Regard to Subjective Wellbeing and Company Management: Corporate Managers during the Covid-19 Pandemic. The Journal of Psychology 2023, 157, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, S.D. J. Rentfrow, and W.B. Swann, A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality 2003, 37, 504–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjell, O.N.E. and E. Diener, Abbreviated Three-Item Versions of the Satisfaction with Life Scale and the Harmony in Life Scale Yield as Strong Psychometric Properties as the Original Scales. J Pers Assess 2021, 103, 183–194. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; et al. , Loneliness among dementia caregivers: evaluation of the psychometric properties and cutoff score of the Three-item UCLA Loneliness Scale. Front Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1526569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; et al. , Psychometric evaluation of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 8 among women with chronic non-cancer pelvic pain. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 20693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; et al. , Effects of Hormonal Replacement Therapy and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction on Climacteric Symptoms Following Risk-Reducing Salpingo-Oophorectomy. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; et al. , The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 8-items expresses robust psychometric properties as an ideal shorter version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21 among healthy respondents from three continents. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13, 799769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; et al. , Cardiometabolic Morbidity (Obesity and Hypertension) in PTSD: A Preliminary Investigation of the Validity of Two Structures of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 6045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabah, A.; et al. , Psychometric characteristics of the Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire (NARQ): Arabic version. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.M.; et al. , Cut-off scores of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-8: Implications for improving the management of chronic pain. J Clin Nurs 2023, 32, 8054–8062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Gazar, H.E.; et al. , Decent work and nurses’ work ability: A cross-sectional study of the mediating effects of perceived insider status and psychological well-being. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances 2025, 8, 100283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; et al. The three-item version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) outperforms various structures of the SWLS: Psychometric investigation among people with and without acquired movement disability. 2025. [CrossRef]

| Models | χ2 | p | DF | CMIN/DF | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | RMSEA 90% CI | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (SWLS 1F) | Crude | 44.51 | 0.001 | 4 | 8.90 | 0.958 | 0.917 | 0.176 | 0.131 to 0.226 | 0.0314 |

| Error | 6.09 | 0.107 | 3 | 2.03 | 0.997 | 0.989 | 0.064 | 0.000 to 0.137 | 0.0148 | |

| Model 2 (SWLS 2F: Present life, Past life) | Crude | 44.42 | 0.001 | 4 | 11.11 | 0.957 | 0.894 | 0.199 | 0.149 to 0.254 | 0.0314 |

| Error | 1.81 | 0.614 | 3 | 0.60 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 to 0.087 | 0.0052 | |

| Model 3 (SWLS 2F: Achievement/Congruence, Acceptance/fulfilment) | Crude | 36.44 | 0.001 | 4 | 9.11 | 0.966 | 0.915 | 0.179 | 0.128 to 0.234 | 0.0293 |

| Error | 6.09 | 0.107 | 3 | 2.03 | 0.997 | 0.989 | 0.064 | 0.000 to 0.137 | 0.0148 | |

| Model 4 (SWLS 2F: Achievement, Congruence) | Crude | 7.38 | 0.117 | 4 | 1.85 | 0.996 | 0.991 | 0.058 | 0.000 to 0.122 | 0.0136 |

| Model 5 (SWLS3 1F) | Crude | 65.52 | 0.001 | 18 | 3.64 | 0.962 | 0.940 | 0.102 | 0.076 to 0.129 | 0.0472 |

| Groups | Invariance levels | χ2 | DF | P | Δχ2 | ΔDF | p(Δχ2) | CFI | ΔCFI | TLI | ΔTLI | RMSEA | ΔRMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Configural Metric Scalar Strict |

19.80 22.73 35.09 42.84 |

8 11 14 19 |

0.011 0.019 0.001 0.001 |

2.94 12.35 7.75 |

3 3 5 |

0.401 0.006 0.171 |

0.988 0.988 0.978 0.975 |

0.000 0.010 0.003 |

0.969 0.978 0.969 0.974 |

-0.007 0.007 -0.005 |

0.076 0.065 0.077 0.070 |

0.009 -0.012 0.007 |

0.0199 0.0181 0.0299 0.0292 |

| Age | Configural Metric Scalar Strict |

8.99 11.87 57.08 95.65 |

8 11 14 19 |

0.343 0.374 0.001 0.001 |

2.88 45.21 38.58 |

3 3 5 |

0.411 0.001 0.001 |

0.999 0.999 0.951 0.912 |

0.000 0.048 0.039 |

0.997 0.998 0.930 0.908 |

-0.001 0.068 0.022 |

0.022 0.018 0.111 0.128 |

0.002 -0.093 -0.017 |

0.01690.0231 0.0726 0.0290 |

| Relation | Configural Metric Scalar Strict |

27.79 29.87 30.81 38.37 |

8 11 14 19 |

0.001 0.002 0.006 0.005 |

2.08 0.95 6.57 |

3 3 5 |

0.556 0.814 0.182 |

0.979 0.980 0.982 0.980 |

-0.001 -0.002 0.002 |

0.948 0.964 0.975 0.979 |

-0.016 -0.011 -0.004 |

0.099 0.083 0.069 0.064 |

0.016 0.014 0.003 |

0.0701 0.0748 0.0912 0.1181 |

| Models | HTMT | AVE | ω | α | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | F2 | F1 | F2 | F1 | F2 | |||

| Model 1 (SWLS 1F) | Crude | -- | 0.682 | -- | 0.911 | -- | 0.915 | -- |

| Error | -- | 0.675 | -- | 0.903 | -- | 0.915 | -- | |

| Model 2 (SWLS 2F: Present life, Past life) | Crude | 0.984 | 0.716 | 0.640 | 0.872 | 0.779 | 0.890 | 0.773 |

| Error | 0.984 | 0.736 | 0.627 | 0.892 | 0.769 | 0.890 | 0.773 | |

| Model 3■ (SWLS 2F: Achievement/Congruence, Acceptance/fulfilment) | Crude | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.886 | 0.737 |

| Error | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.886 | 0.737 | |

| Model 4 (SWLS 2F: Achievement, Congruence) | Crude | 0.911 | 0.667 | 0.842 | 0.859 | 0.915 | 0. 851 | 0.914 |

| Items | Mean (SD) | 1F SWLS | Congruence | Achievement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITC | Alpha if item deleted | ITC | Alpha if item deleted | ITC | Alpha if item deleted | ||

| My life is close to my ideal | 4.7 (1.2) | 0.767 | 0.901 | 0.764 | 0.856 | -- | -- |

| The conditions of my life are excellent | 4.8 (1.1) | 0.837 | 0.885 | 0.828 | 0.795 | -- | -- |

| I am satisfied with my life | 5.0 (1.0) | 0.826 | 0.889 | -- | -- | 0.589 | -- |

| I have gotten the important things that I want in life | 5.0 (1.0) | 0.827 | 0.887 | 0.750 | 0.862 | -- | -- |

| If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing | 4.7 (1.2) | 0.678 | 0.918 | -- | -- | 0.589 | -- |

| ICC single measures 95% CI | 0.683 (0.636-0.728) | 0.721 (0.670-0.767) | 0.583 (0.496-0.658) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 24.1 (4.8) | 14.4 (3.1) | 9.7 (3.8) | ||||

| Scale correlations with: | |||||||

| SWLS | -- | 0.758** | 0.885** | ||||

| Age | 0.090 | 0.126* | 0.036 | ||||

| COVID-19 distress | -0.158* | -0.149* | -0.101 | ||||

| Openness to experiences | 0.097 | 0.031 | 0.191** | ||||

| General organizational trait | 0.303** | 0.356** | 0.263** | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).