Submitted:

08 September 2023

Posted:

11 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

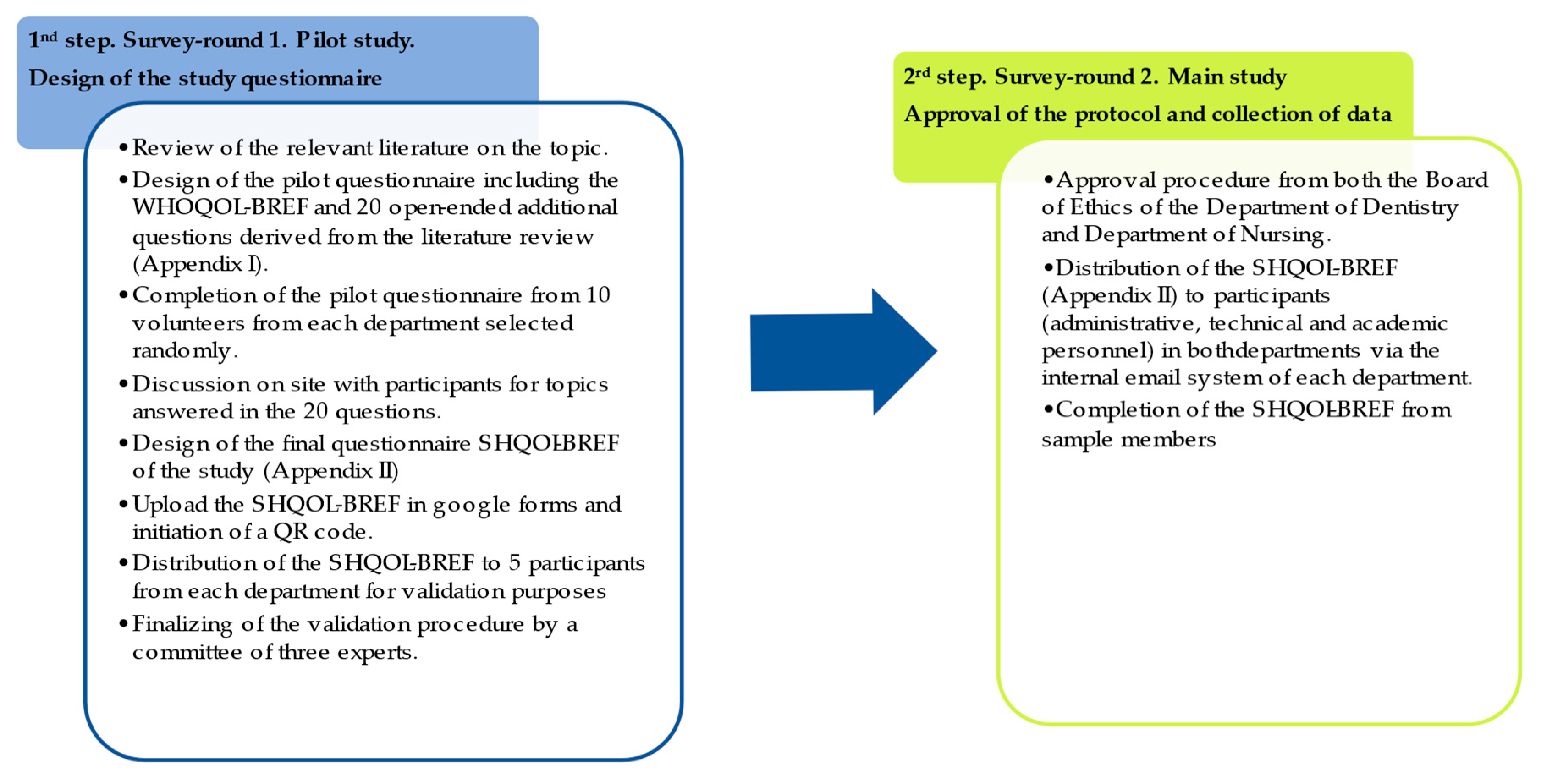

2. Research Methods

2.1. Background of the study

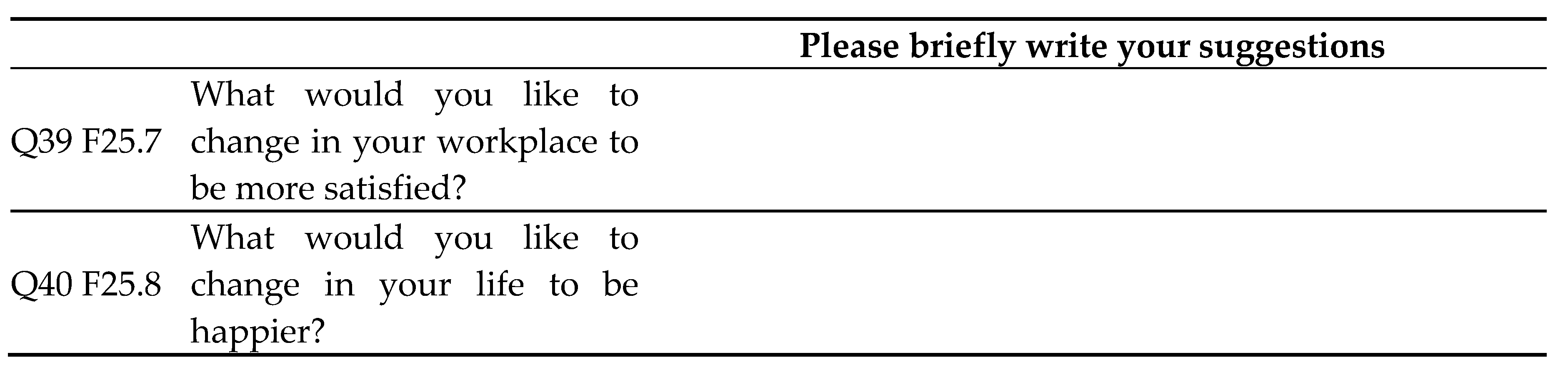

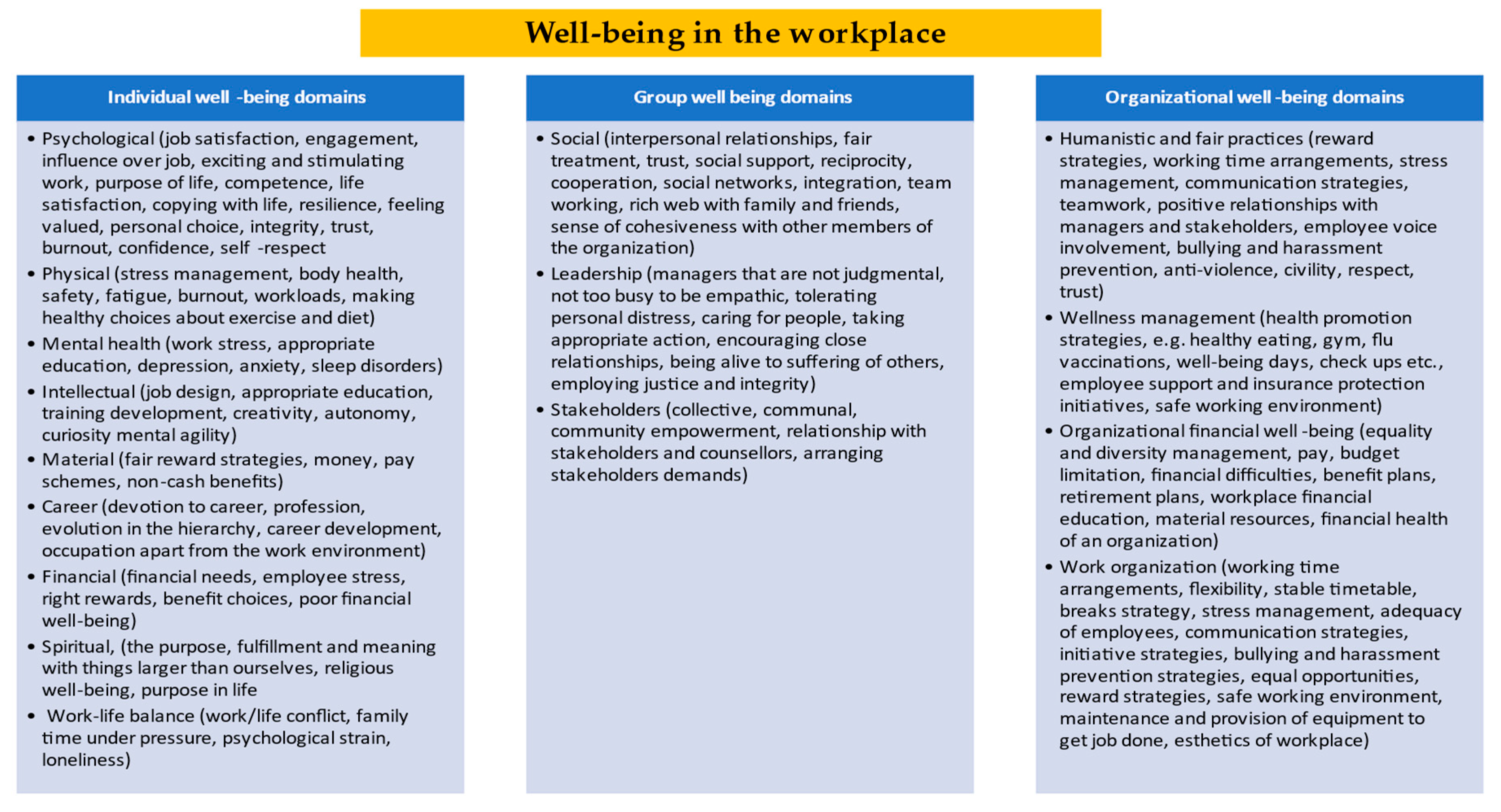

2.2. Identification of Factors Influencing QOL

2.3. Methodology of Designing the Study Questionnaire

2.4. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample

4. Discussion

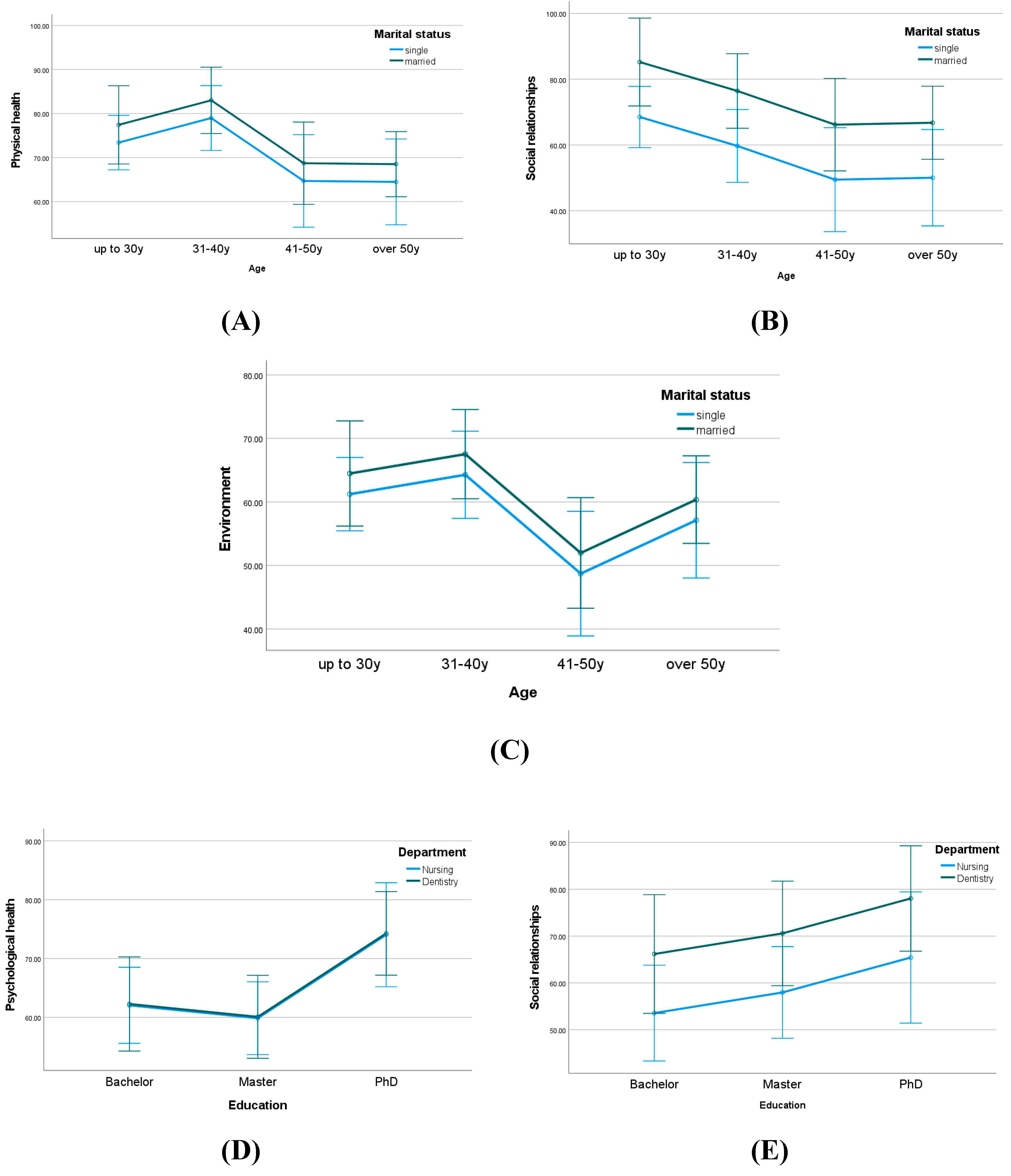

Physical health dimension and QOL

Psychological health dimension and QOL

Environmental dimension and QOL

Social relationships dimension and QOL

Proposals on academic QOL

Limitations of the study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. (pilot study)

- 1)

- In your opinion, what do you understand by the term employee well-being?

- 2)

- What sort of practices had implemented either the administration of the department or that of the university to promote employee wellbeing?

- 3)

- If you have to use words to define your individual well-being at work in the department what would they be? Please explain

- 4)

- Do you have time for breaks at work in the department? Please explain

- 5)

- What are your views about training received within the department the last 12 months? What would you like to suggest for improvement?

- 6)

- How do you feel about having a coach or mentor within the workplace to support you? Please explain

- 7)

- Do you think relationships between administration and staff are harmonious? Please explain

- 8)

- What are your views about team working in the department?

- 9)

- What are your views about recruitment and selection strategies used in the department? Please explain

- 10)

- How satisfied are you with your job? Please explain

- 11)

- What are your views on being able to use your own initiative?

- 12)

- Do you feel that your job is secure? Please explain

- 13)

- What are your views about being adequately compensated for the amount of work and effort that you put into your job?

- 14)

- What are your views about ethical code and reward policy used in the department? Please explain

- 15)

- What are your views on being involved in decision making in the department?

- 16)

- If you were offered more money in another department/university would you think about changing job? Please explain

- 17)

- In terms of work-life balance what are your views on work-life balance practices that should be implemented or enforced within the department?

- 18)

- How has changes within the department affected your well-being? Please explain

- 19)

- How supportive are your colleagues and administration with non-work issues? Please explain

- 20)

- Can you describe what things you would like to see improved in the department to promote your well-being at work?

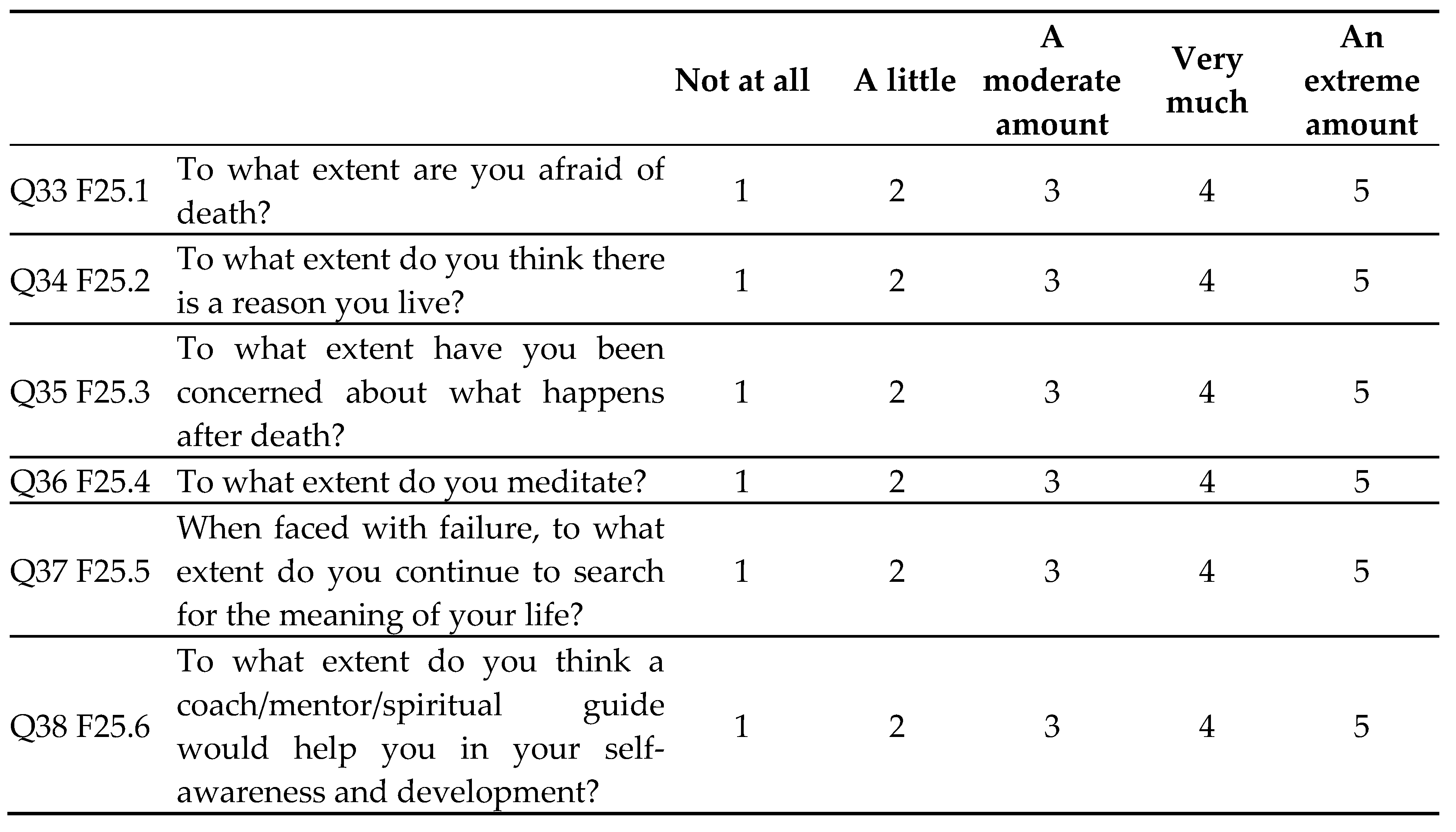

Appendix B. (main study)

Introductory message

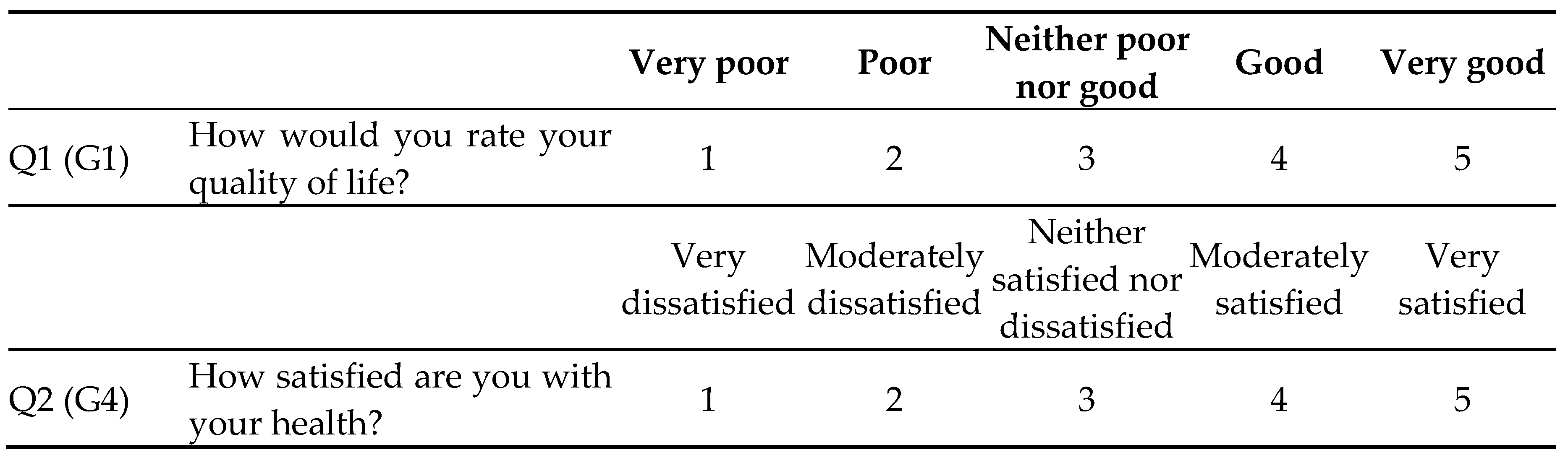

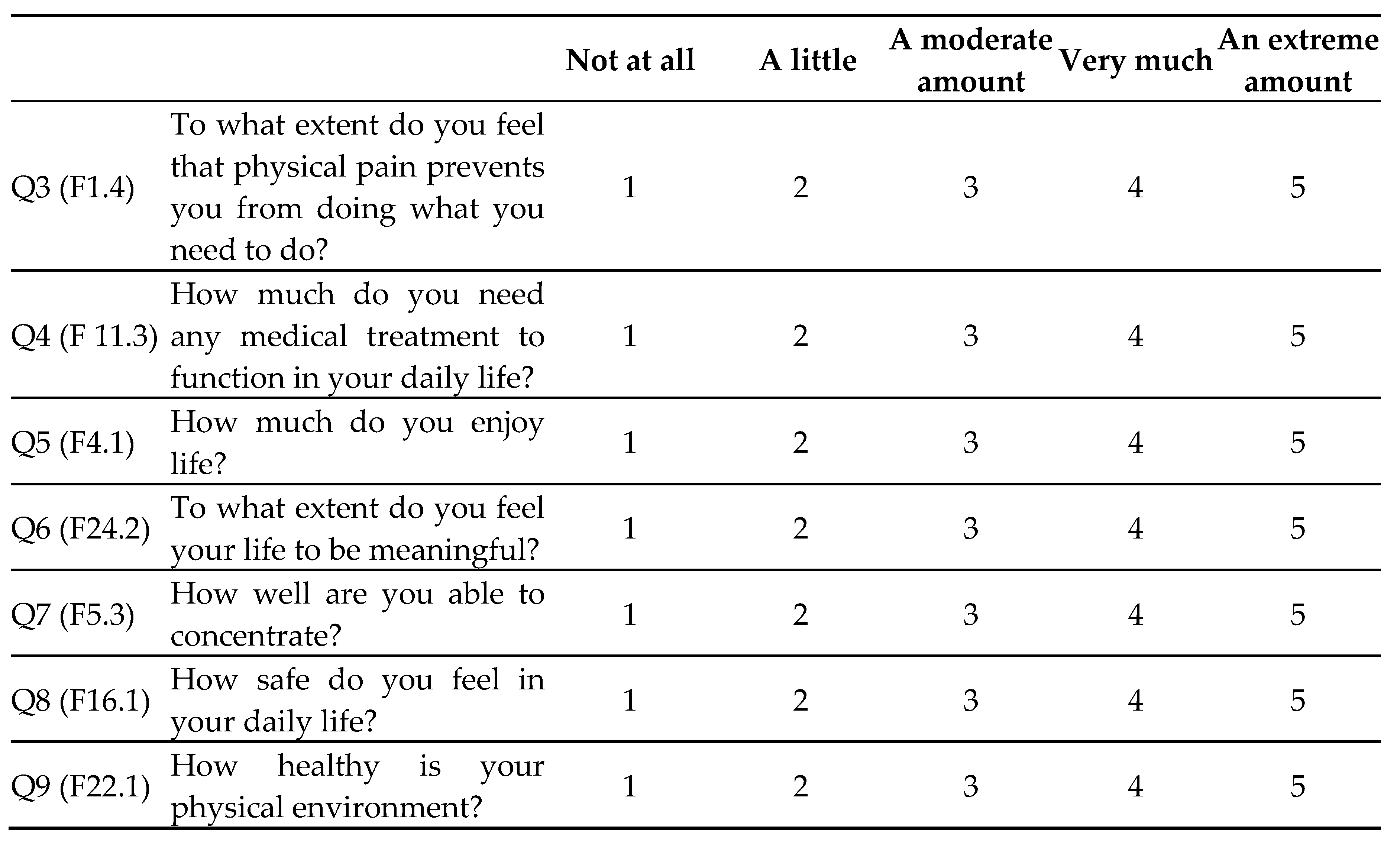

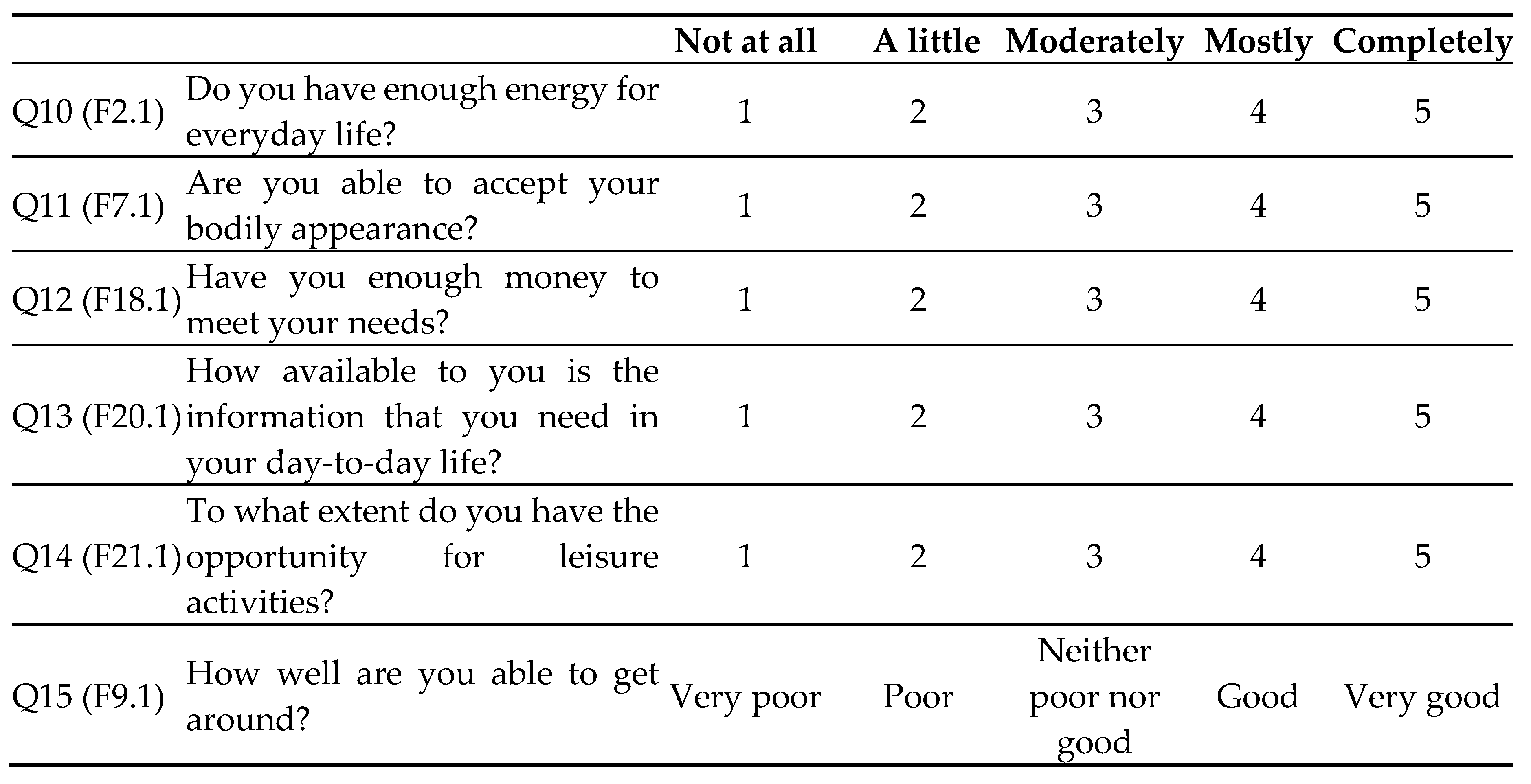

The final version of the questionnaire

DESCRIPTIVE PART

| How well are you able to concentrate? | Not at all 1 |

A little 2 |

A moderate amount 3 |

Very much 4 |

Extremely 5 |

- You should circle the number that best fits how well you are able to concentrate over the last two weeks. So, you would

- circle the number 4 if you were able to concentrate very much. You would circle number 1 if you were not able to

- concentrate at all in the last two weeks.

PART A

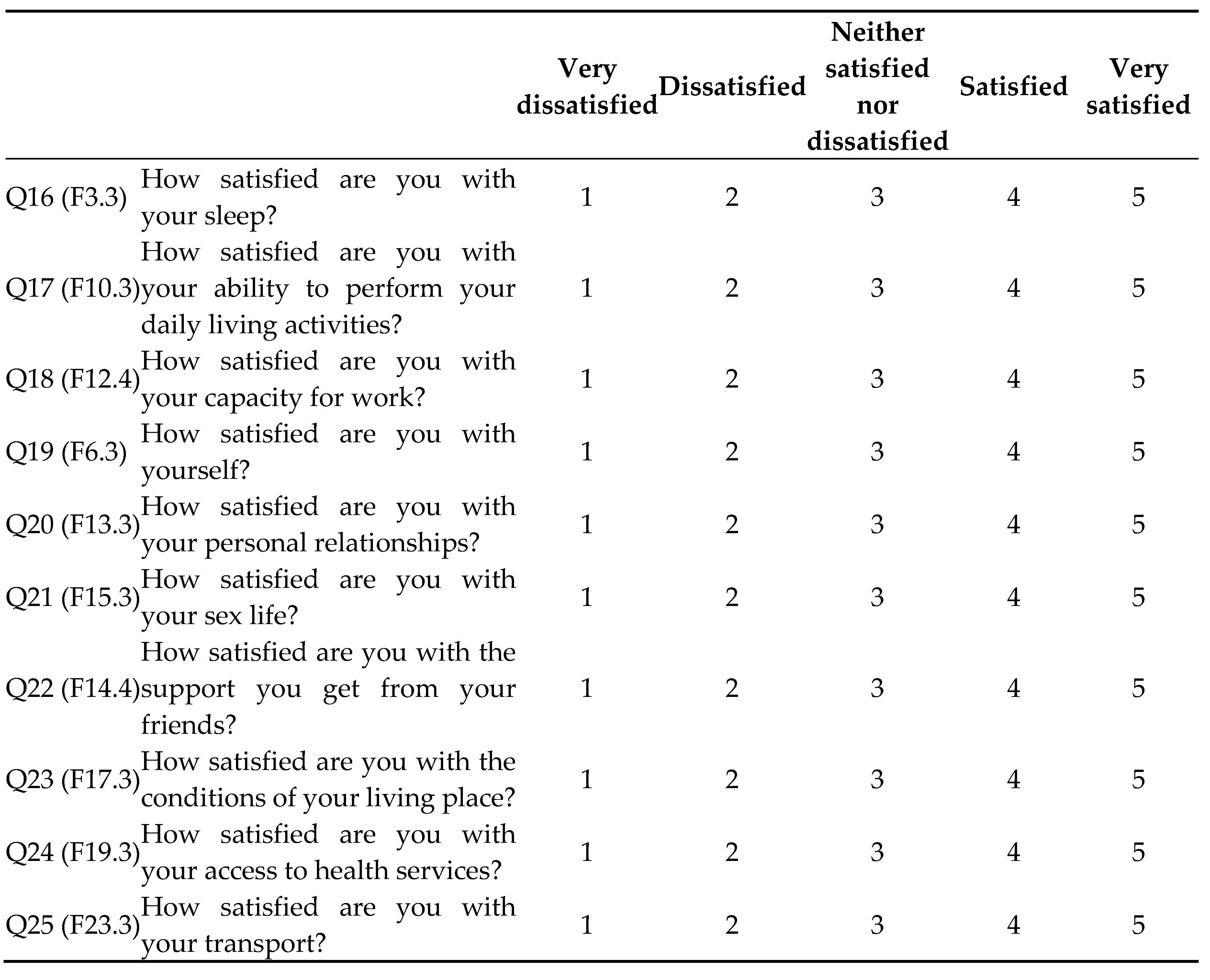

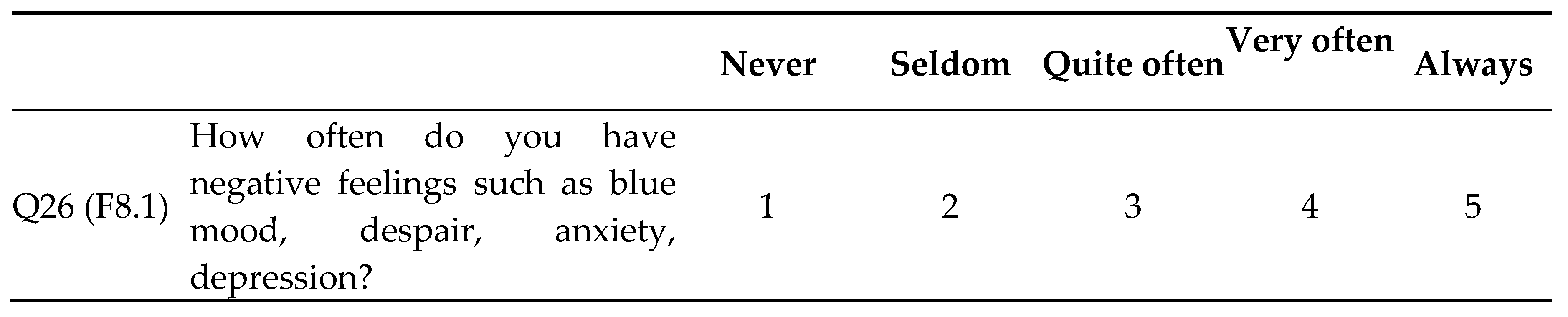

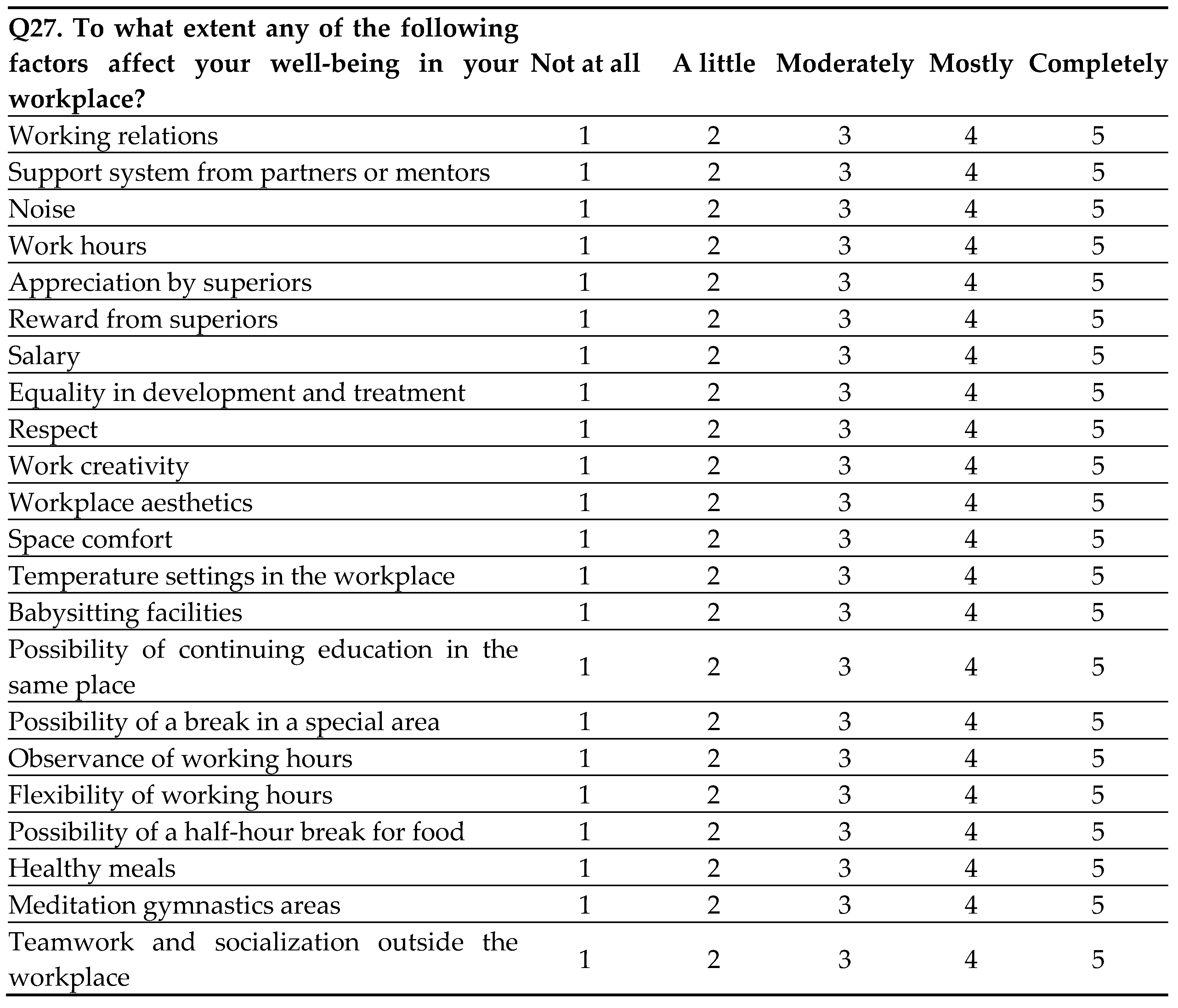

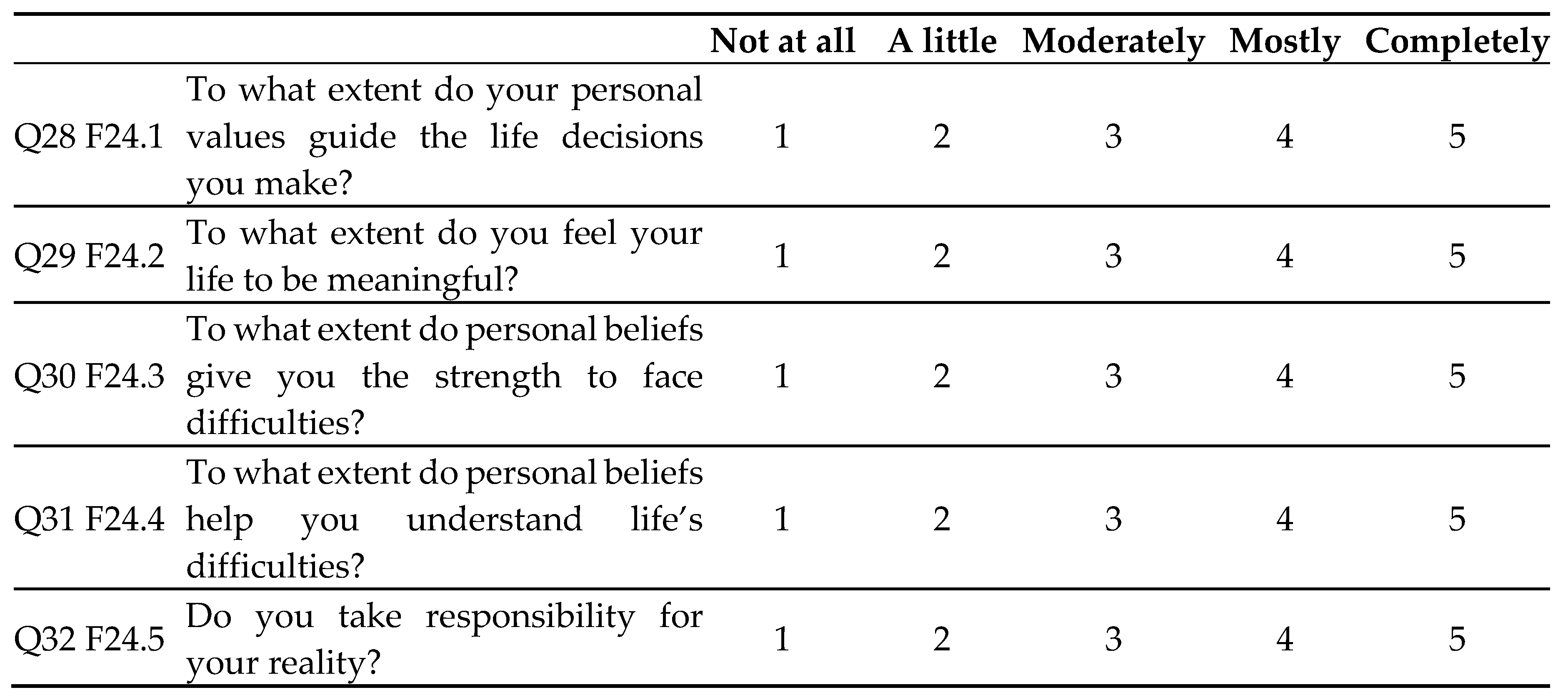

PART B

PART C

PART D

PART E

PART F

PART H

PART G

- -

- How long did it take to fill this form out? ………………………….. minutes

- -

- Did someone help you to fill out this form? YES…………NO…………………

References

- The WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Fernández, M. D.; Ortega-Galán, Á. M.; Fernández-Sola, C.; Hernández-Padilla, J. M.; Granero-Molina, J.; Ramos-Pichardo, J.D. Occupational factors associated with health-related quality of life in nursing professionals: A multi-centre study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coiro, M.J.; Asraf, K.; Tzischinsky, O.; Hadar-Shoval, D.; Tannous-Haddad, L.; Wolfson, A.R. Sleep quality and COVID-19-related stress in relation to mental health symptoms among Israeli and U.S. adults. Sleep Heal. 2021, 7, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korkmaz, S.; Kazgan, A.; Çekiç, S.; Tartar, A.S.; Balci, H.N.; Atmaca, M. The anxiety levels, quality of sleep and life and problem-solving skills in healthcare workers employed in COVID-19 services. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 80, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olagunju, A.T.; Bioku, A.A.; Olagunju, T.O.; Sarimiye, F.O.; Onwuameze, O.E.; Halbreich, U. Psychological distress and sleep problems in healthcare workers in a developing context during COVID-19 pandemic: implications for workplace wellbeing. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 110, 110292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiei, M.; Shirani, S.; Sharifi, T. Study the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral intervention on the quality of life, job satisfaction, and nurses’ organizational performance. J. Clin. Nurs. Midwifery 2018, 4, 3. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Alimoradi, Z.; Brostro, M.A.; Tsang, H.W.H.; Griffiths, M.D.; Haghayegh, S.; Ohayon, M.M.; Lin, C.Y.; Pakpour, A.H. Sleep problems during COVID-19 pandemic and its’ association to psychological distress: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 36, 100916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahrami, H.A.; Alhaj, O.A.; Humood, A.M.; Alenezi, A.F.; Fekih-Romdhane, F.; AlRasheed, M.M.; Saif, Z.Q.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R.; et al. Sleep disturbances during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Sleep Med. Rev. 2022, 62, 101591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.; Khanpara, B.; Mehta, P.; Patel, K.; Marvania, N. Evaluation of perceived social stigma and burnout, among health-care workers working in covid-19 designated hospital of India: A cross-sectional study. Asian J. Soc. Health Behav. 2021, 4, 156–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, Y.; Nagarajan, R.; Saya, G.K.; Menon, V. Prevalence of psychological morbidities among general population, healthcare workers and COVID-19 patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimoradi, Z.; Ohayon, M.M.; Griffiths, M.D.; Lin, C.Y.; Pakpour, A.H. Fear of COVID-19 and its association with mental health-related factors: systematic review and meta-analysis. BJPsych Open 2022, 8, e73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslanidis, V.; Tsolaki, V.; Papadonta, M. E.; Amanatidis, T.; Parisi, K.; Makris, D.; Zakynthinos, E. The Impact of the COVID 19 Pandemic on Mental Health and Quality of Life in COVID 19 Department Healthcare Workers in Central Greece. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dafogianni, C.; Pappa, D.; Koutelekos, I.; Mangoullia, P.; Ferentinou, E.; Margari, N. Stress, anxiety and depression in nurses during COVID-19 pandemic: Evaluation of coping strategies. Int. J. Nurs. 2021, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J. Quality of life and its influence on clinical competence among nurses: A self-reported study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 26, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, A.; Li, P.; Duan, P.; Ding, L.; Xu, S.; Yang, Y.; Guan, X.; Shen, M.; Jiang, Y.; Luo, Y. Professional quality of life in nurses on the frontline against COVID-19. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missouridou, E.; Mangoulia, P.; Pavlou, V.; Kritsotakis, E.; Stefanou, E.; Bibou, P.; Kelesi, M.; Fradelos, E. Wounded healers during the COVID-19 syndemic: Compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction among nursing care providers in Greece. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2022, 58, 1422–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luceño-Moreno, L.; Talavera-Velasco, B.; García-Albuerne, Y.; Martín-García, J. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, depression, levels of resilience and burnout in spanish health personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; Firtko, A.; Edenborough, M. Personal resilience as a strategy for surviving and thriving in the face of workplace adversity: A literature review. J Adv. Nurs. 2007, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarone, K.; McKenney, M.; Elkbuli, A. Preserving mental health and resilience in frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangeneh Soroush, M.; Tahvilian, P.; Koohestani, S.; Maghooli, K.; Jafarnia Dabanloo, N.J.; Sarhangi Kadijani, M.; Jahantigh, S.; Zangeneh Soroush, M.; Saliani, A. Effects of COVID-19-related psychological distress and anxiety on quality of sleep and life in healthcare workers in Iran and three European countries. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 997626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelghani, M.; Mahdy, R.; El-Gohari, H. Health anxiety to COVID-19 virus infection and its relationship to quality of life in a sample of health care workers in Egypt: A cross-sectional study. Arch. Psychiatry Psychother. 2021, 1, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M. Quality of life and satisfaction from career and work-life integration of Greek dentists before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniadou, M. Estimation of factors affecting burnout in Greek dentists before and during the Covid-19 pandemic. Dent J. 2022, 10, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mroczek, B.; Łubkowska, W.; Jarno, W.; Jaraczewska, E.; Mierzecki, A. Occurrence and impact of back pain on the quality of life of healthcare workers. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2020, 27, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woon, L.S.C.; Mansor, N.S.; Mohamad, M.A.; Teoh, S.H.; Leong Bin Abdullah, M.F.I. Quality of life and Its predictive factors among healthcare workers after the end of a movement lockdown: The salient roles of COVID-19 stressors, psychological experience, and social support. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 652326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J. Producing sustainable competitive advantage through effective management of people. Academy Management Exe 2005, 19, b95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowitlawkul, Y.; Yap, S.F; Makabe, S.; Chan, S.; Takagai, J.; Tam, W.W.S. , Nurumal, M.S. Investigating nurses’ quality of life and work-life balance statuses in Singapore. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2019, 66, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M. Application of the humanities and basic principles of coaching in health sciences. www.ekdoseis-tsotras.gr Athens, 2021.

- Antoniadou, Μ. Quality management in health services. The dental model of quality_Μateriam superabat opus. www.ekdoseis-tsotras.gr, Athens, 2022.

- Antoniadou, M. Leadership and managerial skills in Dentistry: Characteristics and challenges based on a preliminary case study. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, D.; Upton, P. Quality of Life and Well-Being. In: Psychology of Wounds and Wound Care in Clinical Practice. Springer: Cham, 2015, pp. 85–111. [CrossRef]

- Baptiste, N.R. Fun and well-being: Insights from senior managers in a local authority. 2009 Empl. Relat. 2009, 31, 600–612. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A.; Christianson, M.; Price, R. Happiness, health or relationships? Managerial practices and employee well-being tradeoffs. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2007, 21, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvenkel, N. Well-being in the workplace: governance and sustainability insights to promote workplace health. Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd, 2020.

- Peccei, R. Human resources management and the search for the happy workplace. Erasmus research institute of management, Rotterdam School of management, Rotterdam school of economics, 2004.

- Chen, P.; Cooper, C. Work and well-being: a complete reference guide (vol III), John Wiley & Sons, 2014.

- Tehrani, N.; Humpage, S.; Willmott, B.; Haslam, I. What’s happening with well-being at work? Change agenda. London: Chartered institute of personnel development, 2007.

- Chechak, D.; Csiernik, R. Canadian perspectives on conceptualizing and responding to workplace violence. J. Workplace Behav. Health 2014, 29, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorkvavoos, M. Compassionate leadership: What is it and why do organizations need moreof ot? Research Chapter Roffey Park, 2016. www.roffeypark.com.

- Meechan, F. Compassion at work toolkit. Alliance Manchester Business School, University of Manchester. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322404395_Compassion_aat_Work_Toolkit. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- CIPD. Health and well-being at work. In partnership with Simply Health, April 2019 championing better work and working lives. London: Chartered Institute of personnel and development. 2019. 20 April.

- Azevedo, W.F.; Mathias, L.A.D.S.T. Work addiction and quality of life: a study with physicians. Einstein (Sao Paulo), 2017, 15, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caillault, P.; Bourdon, M.; Hardouin, J.B.; Moret, L. How do doctors perceive and use patient quality of life? Findings from focus group interviews with hospital doctors and general practitioners. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 1895–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesar, F.C.R.; Oliveira, L.M.A.C.; Ribeiro, L.C.M.; Alves, A.G.; Moraes, K.L.; Barbosa, M.A. Quality of life of master's and doctoral students in health. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2021, 74, e20201116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaturvedi, S.K. Professional quality of life, burnout and alexithymia. Radiother Oncol. 2021, 155, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, D. Philosophische Grundlagen der Psychologie. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1998.

- La qualità di vita conta più della quantità della vita [Quality of life counts more than the quantity of life.]. Recenti Prog Med. 2019, 110, 269–270. [CrossRef]

- Williams, M. Generalization in interpretative research. In T. May (Ed.), Qualitative research in action. London, Sage 2002.

- Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol. Med. 1998, 28, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skevington, S.M.; Lotfy, M.; O'Connell, K.A. WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization's WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual. Life Res. 2004, 13, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.C.; Yao, G. Validation of the factor structure of the WHOQOL-BREF using meta-analysis of exploration factor analysis and social network analysis. Psychol. Assess. 2022, 34, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHOQOL BREF version. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/whoqol/whoqol-bref.

- WHOQOL-SRPB. (2012 revision, WHOQOL-SRPB)( https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MSD-MER-Rev-2012-04).

- Oppenheim, A.N. Questionnaire design interviewing and attitudes measurement (New Ed.). Continuum International: London, 2000.

- Bowling, A. Measuring Disease. A Review of Disease-specific Quality of Life Measurement Scales. Open University Press: Buckingham, 2001.

- Moser, C.; Kalton, G. Survey methods in social investigation (2nd ed.). Gower: Hants, 1992.

- Antoniadou, M.; Chrysochoou, G.; Tzanetopoulos, R.; Riza, E. Green Dental Environmentalism among Students and Dentists in Greece. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haworth, J.; Hart, G. Wellbeing: individual, community and social perspectives. Palgrave MacMillan: Basingstoke, 2007.

- Silcox, S. Health work and well-being: rising to the public sector attendance management challenge. ACAS policy discussion paper, 2007, 6.

- Silverman, D. Interpreting qualitative data: methods for analysing talk, text and interaction. Sage: London, 1993.

- O’Donnell, M.; Shields, J. Performance management and the psychological contract in the Australian federal public sector. J. Industrial. Rel. 2002, 44, 435–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noblet, A.J.; Rodwell, J.J. Integrating job stress and social exchange theories to predict employee strain in reformed public sector contexts. J. Public Admin. Res. Theory Adv. Acc. 2009, 19, 555–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, K. (Ed). Employee well-being and working life: towards an evidence based policy agenda. An ESRC/HSE public policy project, report on a public policy seminar held at HSEE, London, 2009.

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. research methods for business students (5th ed.). Pearson Education, Financial Times, Prentice Hall: London, 2009.

- George, D.; Mallery, P. IBM SPSS Statistics 25 Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference (15th ed.). Routledge: New York, 2019.

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics Ed. 5. SAGE Publications, 2017.

- Ghazy, R.M.; Abubakar Fiidow, O.; Abdullah, F.S.A.; Elbarazi, I.; Ismail, I.I.; Alqutub, S.T.; Bouraad, E.; Hammouda, E.A.; Tahoun, M.M.; Mehdad, S.; Ashmawy, R.; Zamzam, A.; Elhassan, O.M.; Al Jahdhami, Q.M.; Bouguerra, H.; Kammoun Rebai, W.; Yasin, L.; Jaradat, E.M.; Elhadi. Y.A.M.; Sallam, M. Quality of life among health care workers in Arab countries 2 years after COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 917128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teles, M.A.B.; Barbosa, M.R.; Vargas, A.M.D.; Gomes, V.E.; Ferreira, E.F.; Martins, A.M.E.; Ferreira, R.C. Psychosocial work conditions and quality of life among primary health care employees: a cross sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2014, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Boer, A.G.; Geuskens, G.A.; Bültmann, U.; Boot, C.R.; Wind, H.; Koppes, L.L.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.W. Employment status transitions in employees with and without chronic disease in the Netherlands. Int. J. Public Health 2018, 63, 713–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangoulia, P. The influence of secondary traumatic stress on the productivity of health professionals focus on ICU and psychiatric nurses. 2011, Doctoral Dissertation. Faculty of Nursing, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10442/hedi/26088 (accessed 6 September 2023).

- Kua, Z.; Hamzah, F.; Tan, P.T.; Ong, L.J.; Tan, B.; Huang, Z. Physical activity levels and mental health burden of healthcare workers during COVID-19 lockdown. Stress Health 2022, 38, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, C.F.S.; Soares, C.M.; Souza, E.A.; Lisboa, E.S.; Pinto, I.C.M.; Andrade, L.R.; Espiridião, M.A. The health of healthcare professionals coping with the Covid-19 pandemic. Cien. Saude. Colet. 2020, 25, 3465–3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soo, S.Y.; Ang, W.S.; Chong, C.H.; Tew, I.M.; Yahya, N.A. Occupational ergonomics and related musculoskeletal disorders among dentists: A systematic review. Work 2023, 74, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garzaro, G.; Clari, M.; Ciocan, C.; Albanesi, B.; Guidetti, G.; Dimonte, V.; Sottimano, I. Physical Health and Work Ability among Healthcare Workers. A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs. Rep. 2022, 12, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawlader, M.D.H.; Rashid, M.U.; Khan, M.A.S.; Ara, T.; Nabi, M.H.; Haque, M.M.A.; Matin, K.F.; Hossain, M.A.; Rahman, M.A.; Hossian, M.; Saha, S.; Manna, R.M.; Arafat, M.Y.; Barsha, S.Y.; Maliha, R.; Khan, J.Z.; Kha, S.; Hasan, S.M.R.; Hasan, M.; Siddiquea, S.R.; Khan, J.; Islam, A.M.K.; Rashid, R.; Nur, N.; Khalid, O.; Bari, F.; Rahman, M.L. Quality of life of COVID-19 recovered patients in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryavanshi, N.; Kadam, A.; Dhumal, G.; Nimkar, S.; Mave, V.; Gupta, A.; Cox, S.R.; Gupte, N. Mental health and quality of life among healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic in India. Brain Behav. 2020, 10(11), e01837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yan, L.; Long, H.; Yan, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Pu, J.; Liu, L.; Zhong, X.; Jin, X. Occupational Differences in Psychological Distress Between Chinese Dentists and Dental Nurses. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 923626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Tella, M.; Romeo, A.; Benfante, A.; Castelli, L. Mental health of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2020, 26, 1583–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omidi, Z.; Khanjari, S.; Saleji, T.; Haghani, S. Association between burnout and nurses’ quality of life in neonatal intensive care units: During the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2023, 29, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilton, M.F.; Whiteford, H.A.; Sheridan, J.S.; Cleary, C.M.; Chant, D.C.; Wang, P.S. The prevalence of psychological distress in employees and associated occupational risk factors. J. Occ. Environm. Med. 2008, 50, 746–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, F. Organizational behaviour and work: a critical introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Ryff, C.; Singer, B. Psychological well-being: meaning, measurement and implications for psychotherapy research. Psychother. Psychosom. 1996, 65, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veenstra, M.; Gautun, H. Nurses' assessments of staffing adequacy in care services for older patients following hospital discharge. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 805–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, P.; Ball, J.; Drennan, J.; Dall'Ora, C.; Jones, J.; Maruotti, A.; Pope, C.; Recio Saucedo, A.; Simon, M. Nurse staffing and patient outcomes: Strengths and limitations of the evidence to inform policy and practice. A review and discussion paper based on evidence reviewed for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Safe Staffing guideline development. Int. J. Nurs. Studies, 2016, 63, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glette, M. K.; Roise, O.; Kringeland, T.; Churruca, K.; Braithwaite, J.; Wiig, S. Nursing home leaders' and nurses' experiences of resources, staffing and competence levels and the relation to hospital readmissions – A case study. BMC Health Serv. Res., 2018, 18, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belling, R.; Whittock, M.; McLaren, S.; Burns, T.; Catty, J.; Jones, I.; R. ; Rose, D.; Wykes, T. ECHO Group. Achieving continuity of care: Facilitators and barriers in community mental health teams. Implement. Sci., 2011, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, L.; Damen, N.; Wagner, C. Does diverse staff and skill mix of teams impact quality of care in long-term elderly health care? An exploratory case study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, C.A.; Singh, D. From staff-mix to skill-mix and beyond: Towards a systemic approach to health workforce management. Human Resources for Health 2009, 19, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bing-Jonsson, P.C.; Foss, C.; Bjørk, I. T. (2016). The competence gap in community care: Imbalance between expected and actual nursing staff competence. Nord. J. Nurs. Res., 2016, 36, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangoulia, P.; Koukia, E.; Alevizopoulos, G.; Fildissis, G.; Katostaras, T. Prevalence of Secondary Traumatic Stress Among Psychiatric Nurses in Greece. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2015, 29, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.P. , Adair, K.C.; Bae, J.; Rehder, K.J.; Shanafelt, T.D.; Profit, J.; Sexton, J.B. Work-life balance behaviours cluster in work settings and relate to burnout and safety culture: a cross-sectional survey analysis. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2019, 28, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodendieck, E.; Jung, F.U.; Conrad, I.; Riedel-Heller, S.J.; Hussenoeder, F. The work-life balance of general practitioners as a predictor of burnout and motivation to stay in the profession. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulcrano, M.; Evans, S.R.; Sosin, M. Quality of Life and Burnout Rates Across Surgical Specialties: A Systematic Review. JAMA Surg. 2016, 151, 970–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivakumar, K.; Pujar, V. Work Life Balance in the Health Care Sector. Amity J. Healthc. Manag. 2016, 1, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.; Hill, S.; McGovern, P.; Mills, C.; Smeaton, D. High performance management practices, working hours and work-life balance. Br. J. Ind. Relations 2003, 4, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiig S, Fahlbruch B, editors. Exploring resilience: a scientific journey from practice to theory. Springer Open: Cham, 2019.

- Haraldstad, K.; Wahl, A.; Andenæs, R.; Andersen, J.R.; Beisland, E.; Borge, C.R.; Engebretsen, M; Eisemann, L.; Halvorsrud, T.A.; Hanssen, A.; et al. Helseth A systematic review of quality of life research in medicine and health sciences. Qual Life Res. 2019, 28, 2641–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, S.; Aamir, A.; Alom, J.; Rufai, T.A.; Rufai, S.R. British doctors' work-life balance and home-life satisfaction: A cross-sectional study. Postgrad Med. J. 2023, 19, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J.S.; Kotrba, L.M.; Mitchelson, J.K. Antecedents of work-family conflict: a meta-analytic review. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 689–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schell, E.; Theorell, T.; Saraste, H. Workplace aesthetics: Impact of environments upon employee health? Work 2011, 39(3), 203–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinch, W.J.E. Confidentiality: concept analysis and clinical application. Nurs. Forum 2000, 35, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badzek, L.; Gross, L. Confidentiality, and privacy: at the forefront for nurses. Am. J. Nurs. 1999, 99, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkinen, A.; Launis, V.; Wainwright, P.; Leino-Kilpi, H. Privacy and occupational health services. J. Med. Ethics. 2006, 32, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M.; Tziovara, P.; Antoniadou, C. The Effect of Sound in the Dental Office: Practices and Recommendations for Quality Assurance—A Narrative Review. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, C.M.; Luthans, F. Positive organizational behavior in the workplace: The impact of hope, optimism, and resilience. Journal of Management 2007, 33, 774–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Laschinger, H.K.S.; Wong, C. Workplace empowerment, work engagement and organizational commitment of new graduate nurses. Nurs. Leadersh. (Tor Ont), 2006, 19, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, G. Towards a new standard employment relationship in Western Europe. Br. J. Industrial Relations 2004, 42, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldinger, R.; Schulz, M.; Waldinger, R.; Schulz, M. Harvard study of adult development. https://www.adultdevelopmentstudy.

- Puciato, D.; Rozpara, M.; Bugdol, M. Socio-economic correlates of quality of life in single and married urban individuals: a Polish case study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2022, 20, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, C.C.; dos Santos, P.R.; Alves, P.M.; Borges, R.C.M.; Lucchetti, G.; Barbosa, M.A.; Porto, C.C.; Fernandes, M.R. Association between spirituality/ religiousness and quality of life among healthy adults: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.K.; Alzahrani, N.A.; Batwie, A.A.; Abushal, R.A.; Almograti, G.G.; Sattam, M.A.; Hussin, B.K. Quality of life, job satisfaction and their related factors among nurses working in king Abdulaziz University Hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Contemp. Nurse 2016, 52, 486–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmanpek, N.K.; Şahin, A.; Demirel, C.; Kiliç, S.P. The relationship between nurses’ job satisfaction levels and quality of life. Perspect Psychiatr Care 2022, 58, 2310–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.P.; Alquwez, N.; Mesde, J.H.; Almoghairi, A.M.A.; Altukhays, A.I.; Colet, P.C. Spiritual climate in hospitals influences nurses' professional quality of life. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 1589–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, B.; Joseph, M. The health of the healthcare workers. Indian J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 20, 71–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, M.; McEwan, K.; Kanovský, M.; Halamová, J.; Steindl, S.R.; Ferreira, N.; Linharelhos, M.; Rijo, D.; Asano, K.; et al. Fears of compassion magnify the harmful effects of threat of COVID-19 on mental health and social safeness across 21 countries. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2021, 28, 1317–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missouridou, E.; Mangoulia, P.; Pavlou, V.; Kritsotakis, E.; Stefanou, E.; Bibou, P.; Kelesi, M.; Fradelos, E.C. Wounded healers during the COVID-19 syndemic: Compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction among nursing care providers in Greece. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2022, 58, 1421–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penconek, T.; Tate, K.; Bernardes, A.; Lee, S.; Micaroni, S.P.M.; Balsanelli, A.P.; de Moura, A.A.; Cummings, G.G. Determinants of nurse manager job satisfaction: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 118, 103906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benham-Clarke, S.; Ewing, J.; Barlow, A.; Newlove-Delgado, T. Learning how relationships work: a thematic analysis of young people and relationship professionals’ perspectives on relationships and relationship education. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.T.; Park, E.C.; Kim, J.H.; Park, S. Is marital status associated with quality of life? Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2014, 12, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryavanshi, N.; Kadam, A.; Dhumal, G.; Nimkar, S.; Mave, V.; Gupta, A.; Cox, S.R.; Gupte, N. Mental health and quality of life among healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic in India. Brain Behav. 2020, 10, e01837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achangwa, C.; Lee, T.J.; Park, J.; Lee, M.S. Quality of life and associated factors of international students in South Korea: A cross-sectional study using the WHOQOL-BREF instrument. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webometrics Ranking Web of Universities, 2023. Available online: https://www.webometrics.info/en/world. (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Diener, E. Assessing subjective wellbeing. Progress and opportunities. Social Indicators Res. 1994, 31, 103–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ν | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 30 | 25.0% |

| Female | 90 | 75.0% | |

| Age | Up to 30 years old | 41 | 34.2% |

| 31-40 | 29 | 24.2% | |

| 41-50 | 18 | 15.0% | |

| 51-60 | 24 | 20.0% | |

| 61 and above | 8 | 6.7% | |

| Marital status | Single | 54 | 45.0% |

| Living like married | 11 | 9.2% | |

| Married | 49 | 40.8% | |

| Widowed | 1 | 0.8% | |

| Divorced | 5 | 4.2% | |

| Number of children | No children | 75 | 62.5% |

| 1-2 children | 43 | 35.8% | |

| 3-4 children | 2 | 1.7% | |

| Education | Secondary (high school, technical school) | 9 | 7.5% |

| Tertiary (Bachelor) | 35 | 29.2% | |

| Postgraduate (Master) | 48 | 40.0% | |

| Ph.D | 28 | 23.3% | |

| Job position | IDAX administrative staff (administrative) | 8 | 6.7% |

| Administrative staff IDOH (administrative) | 7 | 5.8% | |

| Research Associates (Unpaid) (scientific) | 6 | 5.0% | |

| Research Associates (paid) (scientific) | 2 | 1.7% | |

| Faculty members (scientific) | 25 | 20.8% | |

| Postgraduate students (scientific) | 68 | 56.7% | |

| EIB staff (technical) | 1 | 0.8% | |

| Technical staff IDOH (technical) | 3 | 2.5% | |

| Work experience | 1-10 years | 50 | 42.7% |

| 10-20 years | 34 | 29.1% | |

| 21-30 years | 20 | 17.1% | |

| Over 31 | 13 | 11.1% | |

| Department | Nursing | 67 | 55.8% |

| Dentistry | 53 | 44.2% | |

| Non- academic professional activity | sole proprietorship with more than 2 employees | 6 | 5.0% |

| sole proprietorship | 5 | 4.2% | |

| sole proprietorship with one employee | 11 | 9.2% | |

| I don't know/I don't answer | 17 | 14.2% | |

| I do not maintain a professional activity outside of academic hours | 26 | 21.7% | |

| company (member or director) | 9 | 7.5% | |

| hospital employment | 40 | 33.3% | |

| provision of services without an individual seat | 6 | 5.0% | |

| Annual family income | under 15,000 euros | 47 | 42.0% |

| 15,001-25,000 euros | 30 | 26.8% | |

| 25,001-50,000 euros | 25 | 22.3% | |

| 50,001-100,000 euros | 9 | 8.0% | |

| 100,001 and above euros | 1 | 0.9% | |

| Component | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Working conditions and benefits | Work relationships, rewards, and compensation | Workspace and nature of work | |

| Possibility of a half hour break for food | .867 | ||

| Possibility of a break in a suitable place | .845 | ||

| Possibility of receiving healthy meals | .744 | ||

| Flexibility of working hours | .727 | ||

| Possibility of babysitting | .668 | ||

| Working hours compliance | .616 | ||

| Possibility of continuing education in the same area | .607 | ||

| Ability to socialize with colleagues | .569 | ||

| Spaces for exercise, relaxation, or meditation | .569 | ||

| Appreciation and recognition from superiors | .800 | ||

| Business relations | .798 | ||

| Reward from superiors | .773 | ||

| Support system from colleagues or mentors | .658 | ||

| Equality in development and treatment | .536 | ||

| Noise | .515 | ||

| Salary | .508 | ||

| Workplace aesthetics | .832 | ||

| Work creativity | .805 | ||

| Feeling of giving | .747 | ||

| Space comfort | .701 | ||

| N items | Cronbach’s a | M | SD | Median | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QoL Domain Scores (0-100) | |||||||

| 1. Physical health | 7 | .736 | 72.17 | 15.75 | 75.00 | -0.545 | -0.213 |

| 2. Psychological health | 5 | .741 | 64.58 | 15.31 | 66.67 | -0.616 | 0.221 |

| 3. Social relationships | 3 | .847 | 68.89 | 24.08 | 75.00 | -0.813 | 0.014 |

| 4. Environment | 8 | .756 | 58.72 | 15.54 | 59.38 | -0.359 | -0.176 |

| Overall QoL | 1 | - | 65.63 | 18.64 | 75.00 | -0.501 | 0.713 |

| Satisfaction from health | 1 | - | 72.08 | 22.96 | 75.00 | -0.493 | -0.233 |

| Working conditions and benefits | 9 | .891 | 3.21 | .90 | 3.33 | -0.324 | -0.579 |

| Work relationships, rewards, and compensation | 7 | .840 | 3.42 | .76 | 3.57 | -0.563 | -0.104 |

| Workspace and nature of work | 4 | .869 | 3.64 | .82 | 3.75 | -0.765 | 0.759 |

| Job satisfaction | 4 | .829 | 3.17 | .97 | 3.25 | -0.122 | -0.747 |

| Personal beliefs and values | 4 | .818 | 4.04 | .62 | 4.00 | -0.500 | 0.889 |

| Spirituality | 6 | .621 | 3.01 | .70 | 3.08 | -0.273 | -0.059 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Physical health | -- | |||||||||

| 2. Psychological health | .652** | -- | ||||||||

| 3. Social relationships | .544** | .464** | -- | |||||||

| 4. Environment | .673** | .605** | .511** | -- | ||||||

| 5. Working conditions and benefits | 0.066 | 0.059 | .217* | -0.044 | -- | |||||

| 6. Work relationships, rewards, and compensation | 0.007 | 0.024 | 0.172 | -0.018 | .473** | -- | ||||

| 7. Workspace and nature of work | 0.158 | 0.176 | .293** | 0.134 | .539** | .557** | -- | |||

| 8. Job satisfaction | .377** | 0.17 | .319** | .504** | 0.077 | -0.002 | 0.142 | -- | ||

| 9. Personal beliefs and values | .332** | .595** | .304** | .282** | .234* | 0.145 | .377** | 0.113 | -- | |

| 10. Spirituality | 0.108 | .262** | 0.132 | .223* | .194* | .321** | .324** | .221* | .418** | -- |

| Source | Dependent Variable | Type III SS | Df | MSE | F | p | η2p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected Model | Physical health | 2863.914a | 8 | 357.99 | 1.56 | 0.148 | 0.11 |

| Psychological health | 4547.003b | 8 | 568.38 | 2.74 | 0.009 | 0.18 | |

| Social relationships | 11181.755c | 8 | 1397.72 | 2.68 | 0.010 | 0.18 | |

| Environment | 4036.145d | 8 | 504.52 | 2.52 | 0.016 | 0.17 | |

| Intercept | Physical health | 361283.10 | 1 | 361283.10 | 1570.91 | <.001 | 0.94 |

| Psychological health | 295091.40 | 1 | 295091.40 | 1420.64 | <.001 | 0.94 | |

| Social relationships | 293787.22 | 1 | 293787.22 | 563.79 | <.001 | 0.85 | |

| Environment | 243657.41 | 1 | 243657.41 | 1216.65 | <.001 | 0.93 | |

| Gender | Physical health | 39.61 | 1 | 39.61 | 0.17 | 0.679 | 0.00 |

| Psychological health | 118.42 | 1 | 118.42 | 0.57 | 0.452 | 0.01 | |

| Social relationships | 763.33 | 1 | 763.33 | 1.47 | 0.229 | 0.02 | |

| Environment | 447.38 | 1 | 447.38 | 2.23 | 0.138 | 0.02 | |

| Age | Physical health | 1995.74 | 3 | 665.25 | 2.89 | 0.039 | 0.08 |

| Psychological health | 1187.74 | 3 | 395.91 | 1.91 | 0.134 | 0.06 | |

| Social relationships | 2802.83 | 3 | 934.28 | 1.79 | 0.154 | 0.05 | |

| Environment | 1681.32 | 3 | 560.44 | 2.80 | 0.044 | 0.08 | |

| Marital status | Physical health | 291.79 | 1 | 291.79 | 1.27 | 0.263 | 0.01 |

| Psychological health | 659.86 | 1 | 659.86 | 3.18 | 0.078 | 0.03 | |

| Social relationships | 5032.72 | 1 | 5032.72 | 9.66 | 0.002 | 0.09 | |

| Environment | 190.44 | 1 | 190.44 | 0.95 | 0.332 | 0.01 | |

| Department | Physical health | 139.89 | 1 | 139.89 | 0.61 | 0.437 | 0.01 |

| Psychological health | 0.88 | 1 | 0.88 | 0.00 | 0.948 | 0.00 | |

| Social relationships | 2659.13 | 1 | 2659.13 | 5.10 | 0.026 | 0.05 | |

| Environment | 128.29 | 1 | 128.29 | 0.64 | 0.425 | 0.01 | |

| Education | Physical health | 794.56 | 2 | 397.28 | 1.73 | 0.183 | 0.03 |

| Psychological health | 1553.88 | 2 | 776.94 | 3.74 | 0.027 | 0.07 | |

| Social relationships | 1061.42 | 2 | 530.71 | 1.02 | 0.365 | 0.02 | |

| Environment | 888.58 | 2 | 444.29 | 2.22 | 0.114 | 0.04 | |

| Error | Physical health | 22308.40 | 97 | 229.984 | |||

| Psychological health | 20148.52 | 97 | 207.717 | ||||

| Social relationships | 50545.84 | 97 | 521.091 | ||||

| Environment | 19426.14 | 97 | 200.269 | ||||

| Total | Physical health | 581403.06 | 106 | ||||

| Psychological health | 465746.52 | 106 | |||||

| Social relationships | 549652.77 | 106 | |||||

| Corrected total | Environment | 394560.54 | 106 | ||||

| Physical health | 25172.31 | 105 | |||||

| Psychological health | 24695.52 | 105 | |||||

| Social relationships | 61727.59 | 105 | |||||

| Environment | 23462.28 | 105 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).