1. Introduction

In order to optimize the quality of care, it would be recommended to increase the addressability and sustainability of health care services among the population [

1,

2]. Patient’s satisfaction depends on numerous items, such as the quality of primary medical services, the cleanliness of the units, the complacency with the linen change frequency, the quality and quantity of the primary meal, and the administrated medication.

The wellbeing of people insured in Romania is directly dependent on the quality level of medical services delivered by the providers [

3]. At an international policy level, as well as at regional and local levels, direct correlations are foreseen between the health and well-being of the population [

4].

The Governmental Emergency Ordinance no. 48/2010 for the amendment and completion of some normative acts in health sector, with a view to decentralization, represents a legislative act that modifies Law no. 95/2006 - regarding Health reform, therefore opening a new way of innovative management for Romanian state hospitals. As a result, the local authorities, such as the county and local councils, received a lot of attributions and obligations, mainly in relation to human resources departments, but also to the funding approval for all health units. In fact, the central authority relieved itself of certain administrative tasks and gave them to the local authorities [

5,

6].

Law no. 95/2006 - regarding the Healthcare system reform, represent the basic activities of the Romanian health system, being a fairly faithful copy of the operating principles of the French medical system [

7,

8]. Before decentralization in 2010, public hospitals in Romania were subjected to the Ministry of Health. As the main credit authorizing officer, the Ministry of Health concluded a management contract with each health unit manager. The health unit manager was evaluated annually, based on management indicators that are quantified at the end of the year, according to economic, budgetary and human re-sources data, related to the number of outpatient and hospital consultations [

6,

9,

10].

Beyond the decentralization aspects of hospital management, the state budget allocated to health units, before 1999, was distributed and contracted through the County Health Directorates. After the establishment of the Romanian National Health Insurance House (RNHIH), in 1999, the health insurance system was reformed, entirely through the establishment of County Health Insurance Houses (CHIHs), which contracted directly with accredited providers. Therefore, year 1999 can define an important change for hospitals and clinics, as since thereon funding and budgets are being managed by the local councils. However, highlight must be laid over the health insurance companies, that even if they operate at county level, they remain fully subjected to the RNHIH [

11].

Beyond the legislative/ legal aspects that generated functional structure changes in Romania’s hospital management, the joining of the country to the European Union (EU) in 2007 generated a tumult of medical information, regarding the provision of medical services, under the existing conditions in health facilities in the EU. The positive experiences of Romanian patients in Western European hospitals determined the desire to in-crease the quality of medical services, as well as the availability of medicines and medical devices. However, while comparing the access to medical services in the E.U. with the ser-vices available in Romania, a level of deficit was noted, highlighting the low quality and lack of medical services generated by Romania’s providers.

Over the past two decades /Between year 2000 and 2020 /, the centralized and decentralized medical activity was in a dynamic process and a continuous movement. The "National Health System Development Plan" applied in Romania, implicitly in the municipality of Oradea, aimed to increase the number of medical personnel involved in the supply of medical services in hospitals, in accordance with staff regulations, approved by the Ministry of Health [

12]. Although, the official statistics reported locally statistics di-rectorates, central and local medical administrations, the medical staff represented by doctors, psychologists, physiotherapists, physicists, medical registrars, nurses and care-givers, are insufficient and substandard [

13].

A relevant indicator regarding the quality of medical services in Romania is represented by both, the insufficient number of medical personnel in hospitals and the low salary level compared to the EU medical personnel incomes. Consequently, the number of nurses and doctors who migrated to EU countries increased [

14,

15,

16].

The patient's satisfaction level has certain particularities, related to regional area, in-comes, medical/non-medical knowledge, age and the morbidity and mortality of the population. Factors regarding the understanding, development and continuous improvement of the medical services in hospitals are related to the economic level of the local population, religion and culture, as well as the administrative and historical aspects [

17,

18].

Donabedian's (1990), debates about introducing patient's perception/ feedback in the evaluation of medical care quality, highlighting the important value added in improving the quality of care given. Moreover, this will not only place the patient at the center of the care, but it becomes a major component of medical professional mission [

19,

20,

21]. In French (healthcare)hospitals, the evaluation of patient satisfaction has been mandatory since 1996 [

22], whilst in Germany, quality management reports introduced the quantification of patient satisfaction in 2005 [

23,

24,

25]. Patient satisfaction surveys (PSS) is a tool used to control the quality of medical care provided to hospitalized patients [

26,

27].

The objective of this study is to emphasize the degree of patient satisfaction, depending on the specialty of the hospitalization department: surgical, medical, oncological, psychiatry, and to evidence the factors influencing the reliability and accuracy of patients' answers, such as: the patient's health condition upon admission, the duration of the ad-mission, the level of physical pain and the emotional state.

2. Materials and Methods

Methodology

This research was conducted in two public hospitals in the north-west of Romania, independent Legal Entities: Municipal Clinical Hospital of Oradea (MCHO) and County Clinical Emergency Hospital of Oradea (CCEHO), between April and December 2021, aiming on the above’s hospitalized patients. With regards to the medical services provided, CCEHO manages mostly acute cases, while MCHO is predominantly a hospital dedicated to the evaluation and care of chronic patients. From the initial moment of the decentralization initiated in 2010, the two sanitary units in the western area of Romania were developed by “complementarity”.

The completion of the PSS questionnaires was carried out in both public health units, in compliance with the data confidentiality policies, respecting the patient's rights, but also considering the standards of professional ethics. The questionnaires were submitted for evaluation and subsequent approval to the Ethical Council of CCEHO (11908/11.05.2021), as well as to the Ethical Council of MCHO (13413/15.04.2021).

The Patient Satisfaction Survey consists of 24 items: (Supplementary material) items 1-5 (Patient Data), items 6-15 (Quality of Medical Care) and items 16-23 (Quality of Hospital Services). The questionnaire was explained to all patients and they could ask for additional information as many times as they needed. For medical care and hospital environmental conditions the score was between 0-3 points. These indicators contained in the above presented questionnaire and their total score obtained from their quantification will result in the general degree of satisfaction of the patients who were hospitalized in the two hospitals audited from northwestern Romania.

Only the patients who had at least one hospitalization between 2000-2010 or/and between 2010-2020 were asked to completed this questionnaire, and depending on their hospitalization period, the surveys had two answer options: A. the first option was in reference to inpatient hospitalization between 2000-2010; B. the second option was in reference to inpatient hospitalization between 2010-2020.

The PSS parameters were approved by the management of the two hospitals, in accordance with the national national guideline [

25].

Data collection

PSS was distributed in CCEHO and MCHO, and a total of 1125 (4.63%) out of 24,290 dis-charged patients, completed the PSS. At the CCEHO, from the 14,198 discharged patients, only 567 (3.99%) completed the PSS, while at the MCHO, from the 10,092 discharged patients, 558 (5,52%) completed the PSS. The following formula has been applied to calculate the sample size:

N – total population size; z – confidence interval 95% – Z=1.96; n – sample population size; p – probability value (0.1); q=1-p (0.9); E – margin of error (0.05).

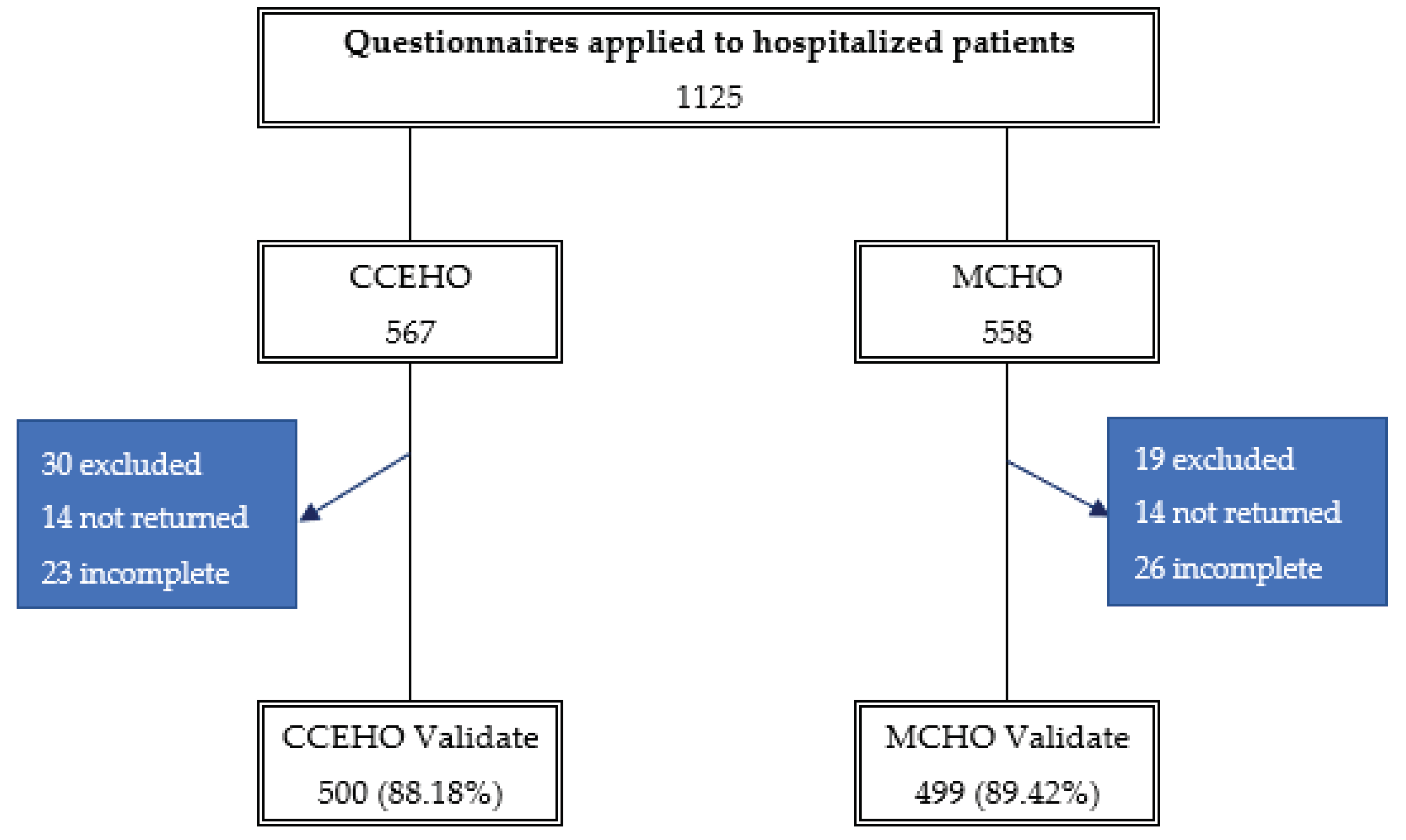

The minimum representative sample size is 129, according to the calculations. A total number of 1125 survey responses have been registered from hospitalized patients between 2010-2021 (CCEHO and MCHO). Of these, 999 answers were validated (500 for CCEHO and 499 for MCHO) (

Figure 1).

Statistical analysis

In the aspect of statistical analysis, SPPS 20 and Microsoft Excel 2019 was used to interpret the data obtained from patients. Frequency ranges, mean parameter values, tests of statistical significance and standard deviations, were calculated by the χ2 method. To compare the mean values, (de ex: the authors have chosen to use the ANOVA tool) the significance of statistical level being 0.05.

3. Results

Patient data

This study shows that women prevailed (53.05%), the women/men ratio being 1.1:1. Over 50% of the subjects were aged between 30-60 years (50.85%), and those aged over 60 years representing 40.94%. Regarding the provenience, 55.16% of patients were from urban areas, the urban/rural ratio being 1.2:1. Over 60% of the subjects were college graduates (68.27%), and those who graduated university representing 20.67% (

Table 1).

Medical care

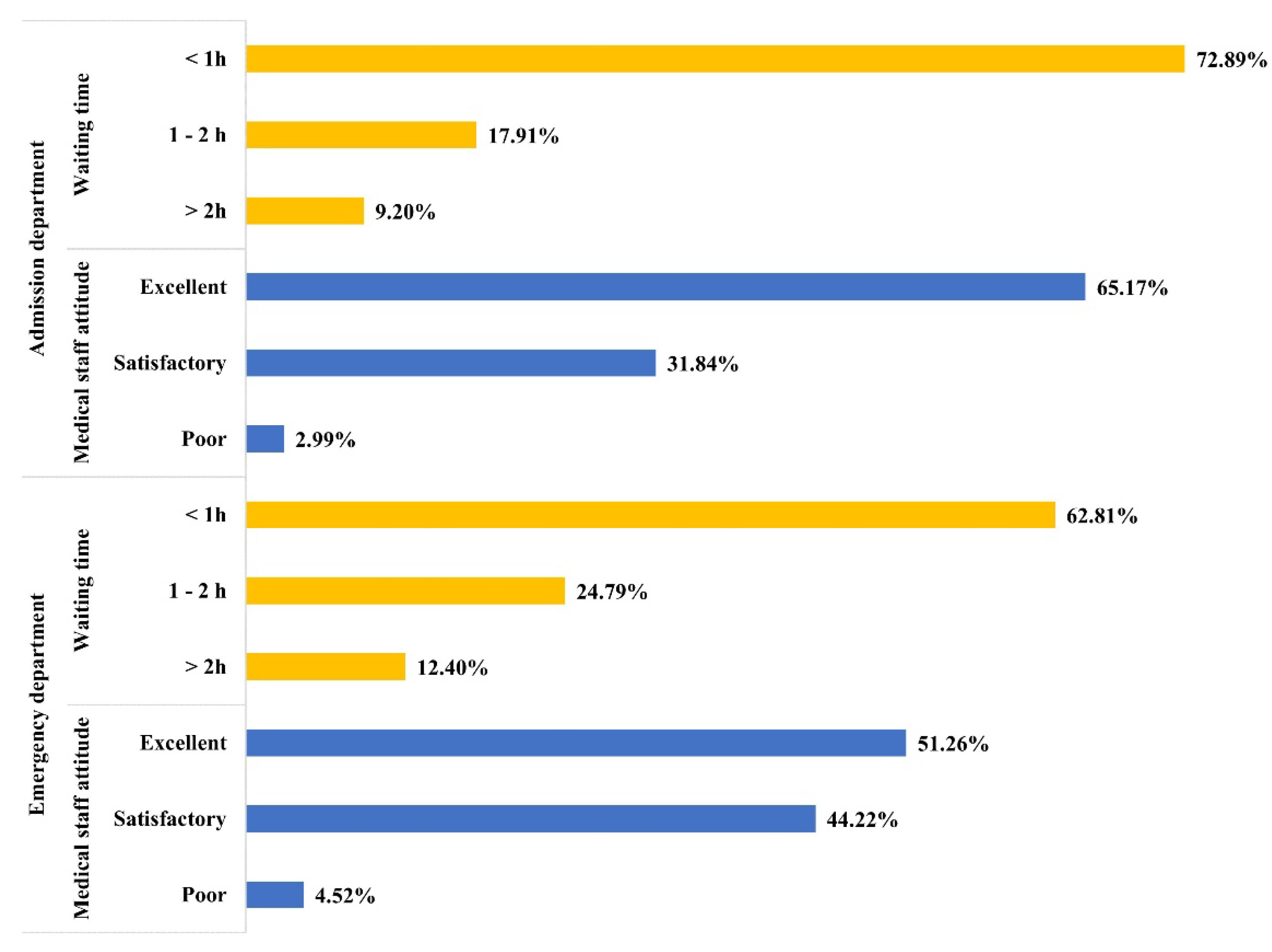

Among the 402 elective inpatients/hospitalized patients, the waiting time of <1 hour was declared for 72.89% of the subjects, and the waiting time of >2 hours was declared to a percentage of 9.20%.

Among the 597 patients admitted in the hospital for emergency situations, the waiting time in the emergency room was under one hour and was declared in 62.81% of the cases, whilst more than 2 hours waiting time happened only in 12.40% of the cases.

Medical personnel was audited for their behavior and attitude towards patients. Moreover, of the two categories of patient admissions, elective and emergency, the feedback displays as excellent in 62.17% of the cases for the elective admission staff. However, the score is slightly reduced when patients came to face the staff in the Emergency department, where only 51.26% of the patients were fully satisfied with personnel’s atitude. 51.26%, and the unsatisfactory attitude by 2.99% and 4.52%, respectively (

Figure 2).

The waiting time as well as staff’s attitude towards patients have highlightted significant differences between the two admitting areas (p<0.001). and are presented in detail in

Figure 2.

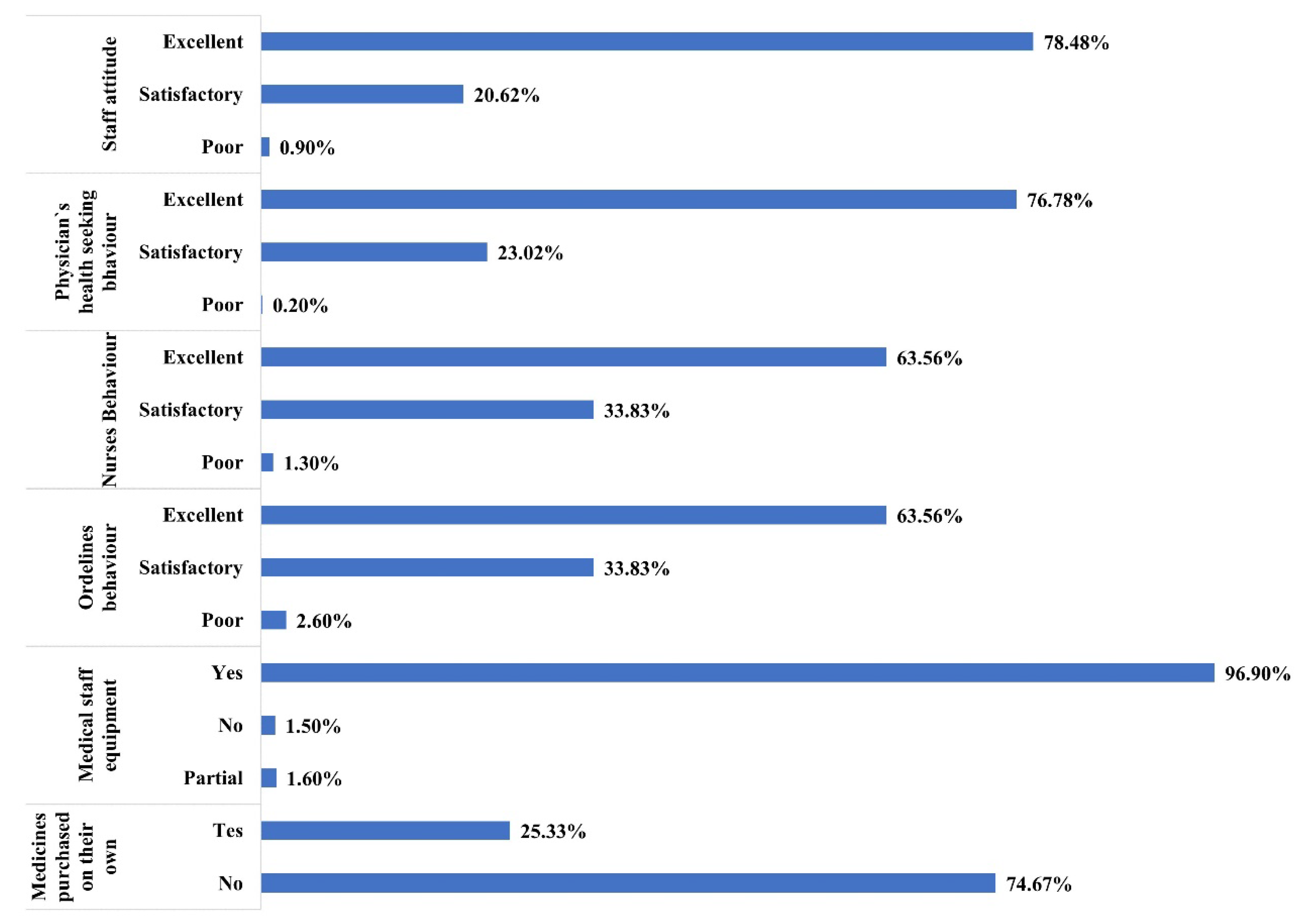

Despite the slightly lower positive feedbacks given during their admission, patients have rated the staff higher during their inpatient stay, for up to 78.48% as excellent, and only 0.90% on the patients were completely unsatisfied with the way they have been treated. Patients were given the opportunity to feedback on all medical personnel during their questionnaire. Following their hospital experience, the subjects evaluated all from admission staff, to nurses, doctors, carers and members of the multidisciplinary team (MDT). Nursing and doctors were scored almost similar with a 77.58% excellent rated for nurses and 76.28% for doctors; both groups were evaluated for the care and expertise provided as well as attitude and competence. The percentage of respondents who rated the quality of doctor medical record as very good was 77.58% in the case of nurses, 76.28% for doctors (p=0.670), however significantly higher than the nurses' medical records (63.56%, p<0.001).

Over the years, patient’s experience has become the focus point of all healthcare services, being the main indicator for quality and improvement of care. Associated with the perception of care, patient experience could be anything from a clinical conversation with medical professionals, to the choice of menu or performance of the equipment. All these factors can influence the care quality and have a significant impact on patient hospital experience. Clinical effectiveness and patient safety can be obtained through analyzing these experiences, positive or negative, and acting upon them accordingly (

Figure 3).

In this study, the questionnaire offered patients the opportunity to assess not only staff but their appearance and use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) as well. Therefore, studying patients replies, the majority have praised the appropriate use of PPE to a percentage of 96.90% of the respondents.

Inpatient medication treatment remains an issue in Romania as more than 25% of the patients participating in the study have had to provide their own medication from outside the hospital boundaries. The most likely insufficient funding for in-hospital medication has been escalated to local and national responsible authorities to support the improvement of the hospital pharmaceutical facilities and ease patient’s financial discomfort.

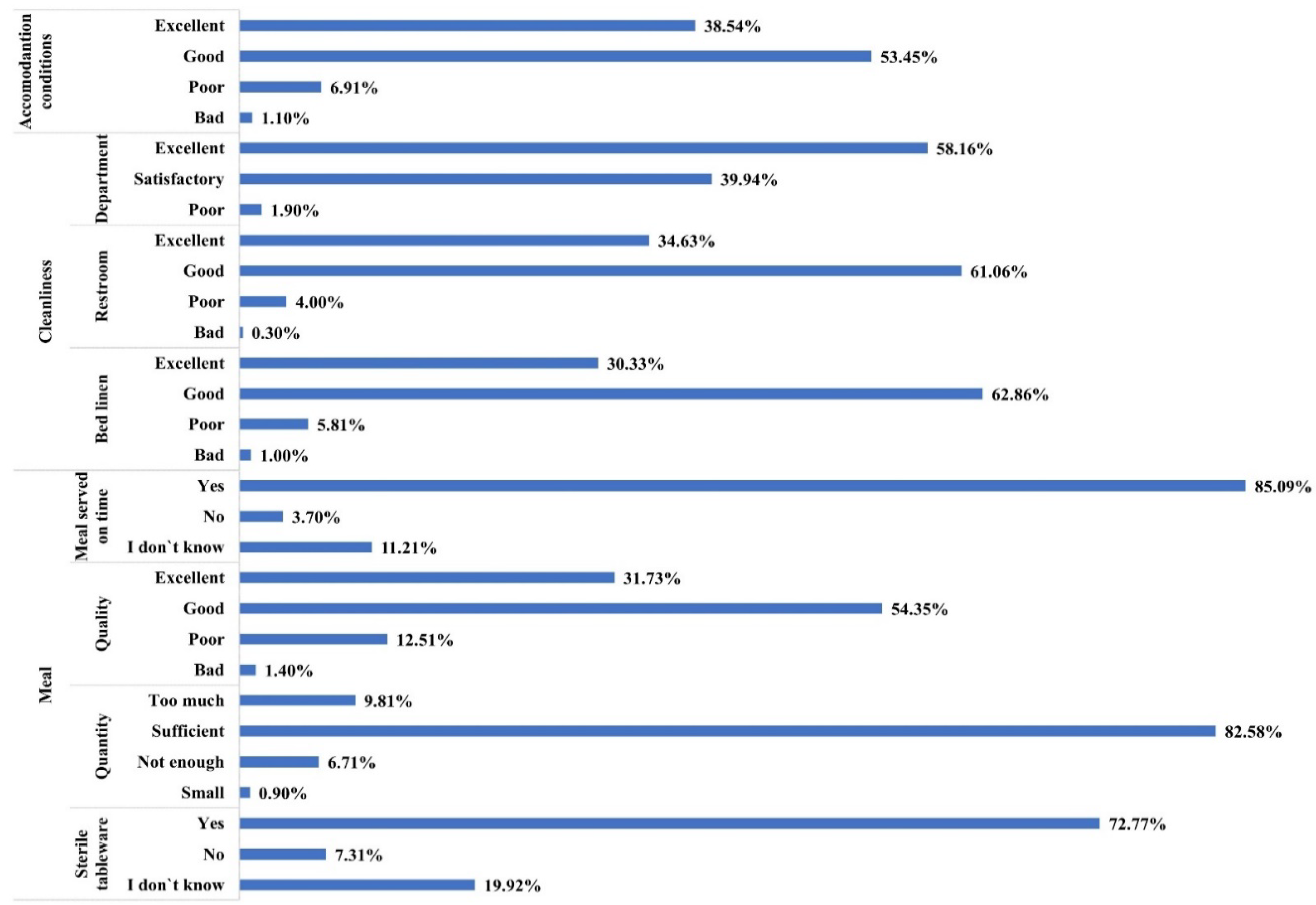

This evaluation point asked patient to score their stay, accommodation conditions and comfort provided. A total of 8% of the evaluators have scored the environment as poor and very poor, whilst the majority have rated their stay as good (53.45%) and very good 38.54%,

Another hospital environmental important aspect is the cleanliness and hygiene, which the majority of the patients have rated as excellent, with a higher percentage for bathrooms 62.6% compared to the ward bays and side rooms 58.16%. Bed linen and its regular change has also received positive feedback in 61.06% of the cases. However, there were patients who considered the cleanliness unsatisfactory. The majority of subjects appreciated the cleanliness of the wards as excellent (58.16%), the cleanliness of bathrooms (61.06%) and a good quality of linen (62.86%) (

Figure 4).

Patient experiences showed that the food was served on time in 85.09%, the quality of the food was good in 54.35%, sufficient (82.58%), and the dishes were hygienic in 72.77 %. The results have since the evaluation been escalated immediately and new policies and regular auditing have been put in place to improve patient safety and experience.

Questionnaire evaluation by domains

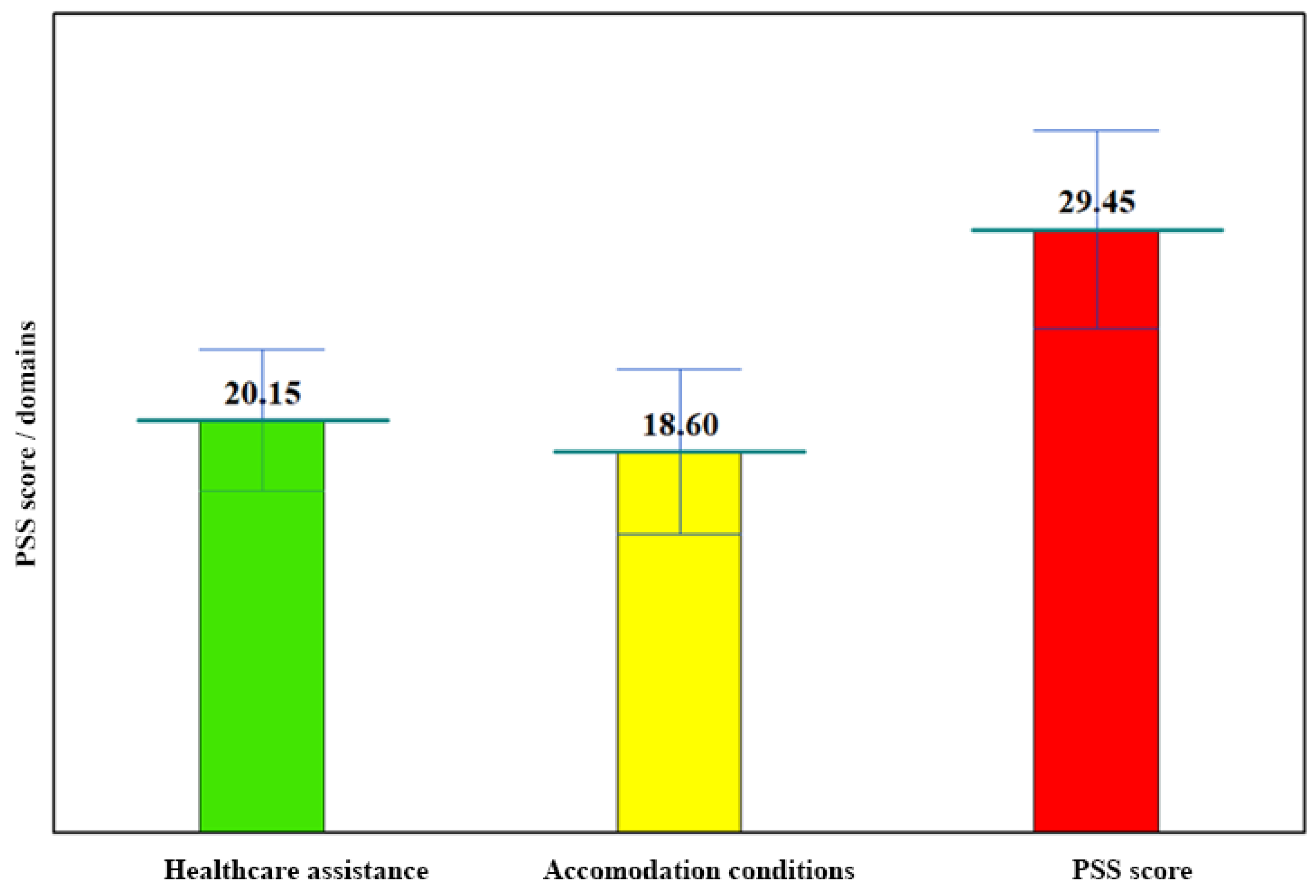

The total value of the PSS score is 29.45, which, referring to the maximum score of36, corresponds to a satisfaction level of 81.81%.

The level of satisfaction per domain is 83.96% for medical activity (score=20.15) and 77.50% for hospital room conditions (score=18.60), the maximum score for each of the two domains being 24 (

Figure 5).

The PSS score on admission was significantly higher for the Elective admissions in comparison with those in the Emergency department (ER) (4.64 vs 4.11, p<0.001), both in terms of waiting time and staff behavior (2.37 vs 2.13, respectively 2.27 vs 1.98, p<0.001). The level of satisfaction is therefore 77.33% in Elective cases and respectively, 68.50% for emergencies.

On evaluation of the waiting time on admission (Reception Office +Emergency Room) the CSP score is 2.23±1.08, with satisfaction level 74.33%, and regarding the staff’s behavior the score is 2.10±1.03 and a satisfaction level of 70.00% (

Figure 6).

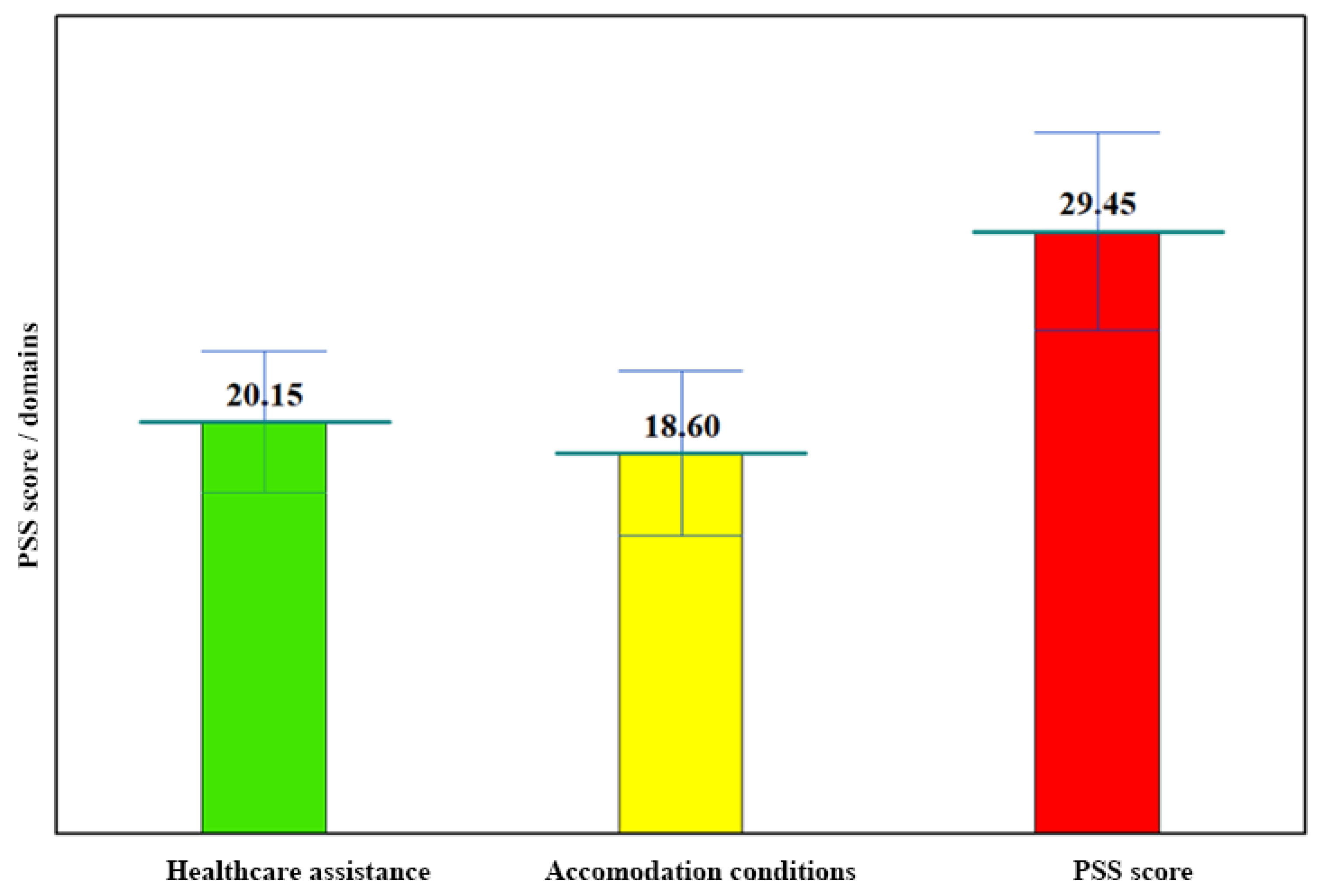

The lowest score was recorded for Hospital Pharmacies, as a significant number of patients were asked to provide their medication from other pharmaceutical sources, outside the hospitals’ premises (2.24). Moreover, patients also scored significantly low staff’s attitude (2.56) and nursing care quality (2.58) (

Figure 7).

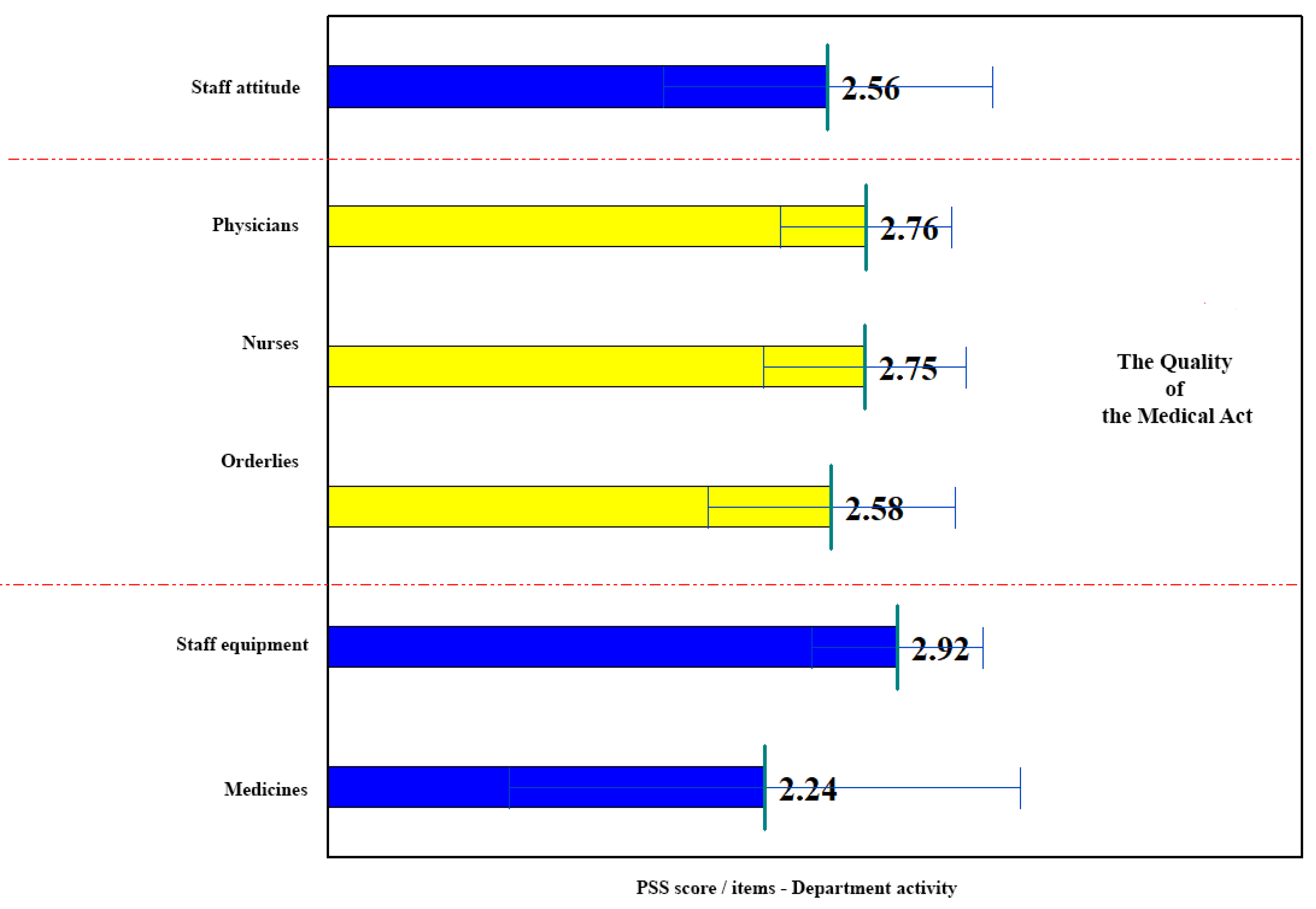

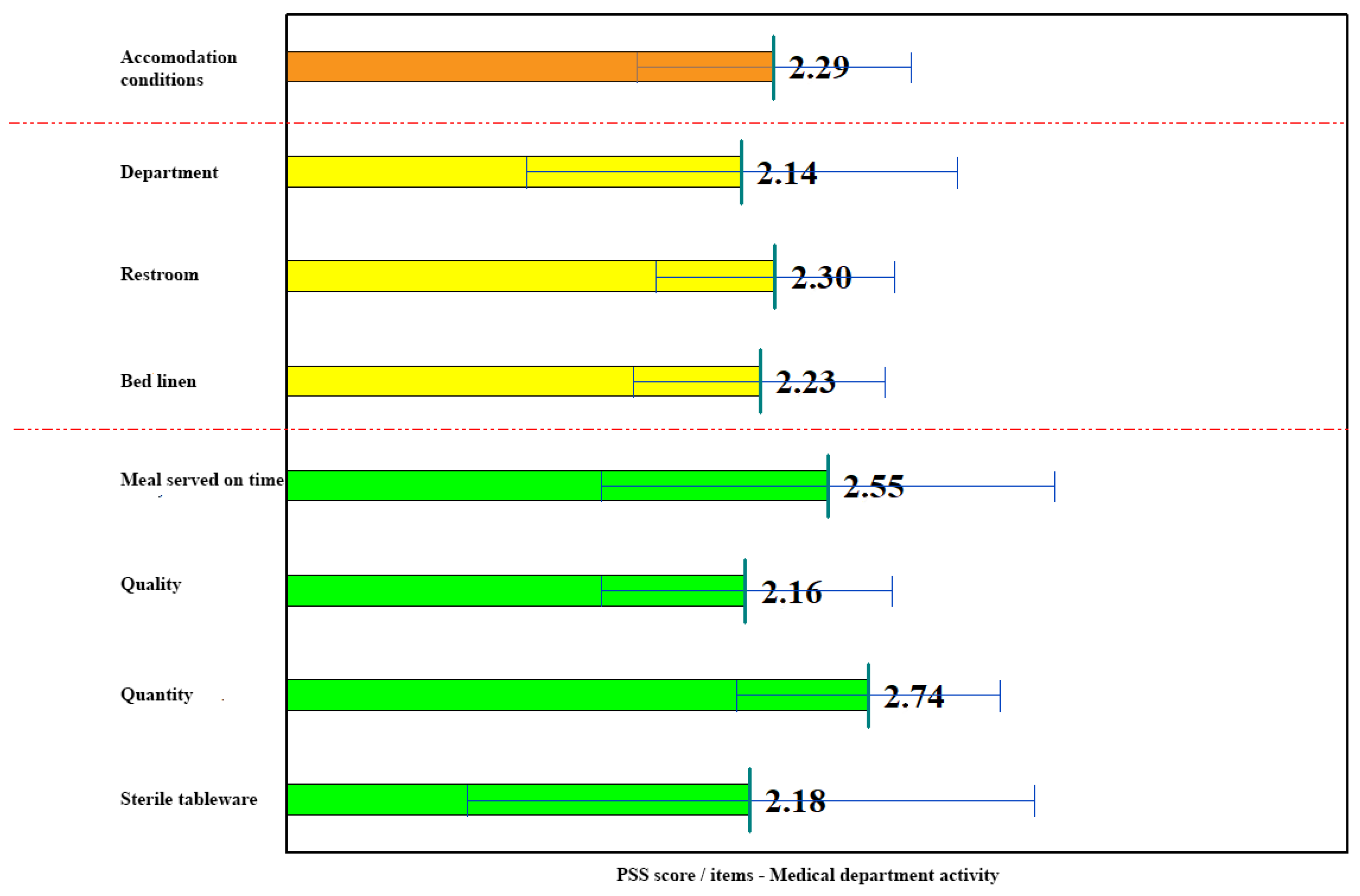

Regarding hospital room accommodation-, the lowest scores were recorded for cleanliness in the wards (2.14) – with a satisfaction level of 71.33% of the cases. The quality of linen scored (2.23), but 74.33% of the patients were satisfied with the services. Hospital meals have also been market low for their quality and nutritional value offered (2.16), whilst 72.00% of the patients have been satisfied. Choice of crockery and cutlery was also limited, outdated and had cleanliness concerns therefore, patients have scored the lowest (2.18) with a72.67%. being satisfied (

Figure 8).

In conclusion, the feedbacks received and the levels of satisfaction highlight the weak points needing improvement. it is vital for these indicators improve significantly and urgently, in order to create better experiences for patients and service users. Furthermore, it is necessary to act on waiting times, but also on the attitude of the personnel in the admission departments (Elective Centre, Emergency Department). Also, measures should be taken to supply hospitals with drugs so that patients do not have to use their own medication taken before the admission in the hospital.

4. Discussion

Romanian Ministry of Health Act no. 443/2019 responsible for the national triage protocol in emergency units, introduces a new triage protocol in the Emergency Reception Units to ensure that the triage is carried out (immediately upon arrival to the Units, with a clerking breach time of 30 minutes). Moreover, to guarantee that the best possible care and expertise is offered, the triage can only be performed by a designated medical professional such as a senior nurse or clinical specialist, responsible for the assessment and prioritization of individual’s care. The guideline’s essential criteria, requires the clinician to have a minimum of 3 years’ experience within the designated area, whether it being the Emergency environment or the Elective Centre. Furthermore, essential and desirable skills are required for all medical personnel that must demonstrate on employment excellent communication and behavioral skills, practical competence and organizational skills. In addition to this, staff must also be able to work flexibly, have the ability to adapt and cope with stressful situations and reveal excellent knowledge and competence to prioritize patients according to the emergency of care [

29,

30].

To summarize the outcomes of this study, it is evidenced that both hospitals have presented concerns for staff’s behavior in particular nursing staff. The attitude of the medical staff, in the two hospitals assessed, had a poor result, mainly when assessed in the Emergency department. Although patients were in a higher number pleased with the services received, staff’s behavior has had a major impact on patients experience. To evaluate the causes of poor attitude towards healthcare users, regular audits and disciplinary measures have been put in place in order to improve patient’s experiences. When staff were audited and questioned for their behavior, the main causes resulted being the high workload and the coping with stressful situations. The majority of them have also complained about the insufficiency of staff, whilst others have mentioned the financial lack of motivation that the profession offered. The education levels seemed to also have had an impact on how staff behaved as during the audits it was highlighted that staff that have undergone master’s degrees, bachelors or doctorate level research degree have received better feedbacks from patients and were described as pleasant, confident and competent [

31].

Studying the statistical data obtained, an urgent need for the implementation of professional training programs and reform of their human resources appeared to be required, primarily unqualified staff (nursing auxiliaries), porters, hostess, housekeeping staff. The low (not always) level of education, the increasing level of activity on the ward/hospital, is no excuse for the disinterested, sometimes even ignoring attitude towards the admitted patient. The change in attitude can only be achieved through a thorough and constant involvement of the management of the two health units in this regard.

Municipality of Oradea’s Hospital decentralization represents a particularly favorable process for significant changes regarding the improvement of medical services quality. Bringing patients closer to the local administration, through a direct involvement of political-administrative decision-makers, represents an increase in efficiency in maintaining a real link between the decision-maker and the patient. The two health units discussed in the study, and the medical services provided, can lead to an enhanced level of satisfaction or inpatients.

5. Conclusions

Evaluating patients' satisfaction is a legitimate indicator for service improvement and strategic goals for all healthcare organizations.

The lowest score of PSS recorded in the two public hospitals studied from north-western of Romania was appointed for the Pharmaceutical availability of patients' medical treatment (2.24), attitude of the staff (2.56) and the quality of nursing care offered (2.58). The hospital management’s focus has been set to improve the communication skills among medical staff, to evidence their compassion, politeness, active listening combined with excellent medical care and to ensure the availability of essential drugs, thus positioning the patient in the center of healthcare and creating positive experiences from the patient's point of view.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.D., L.G.D., C.T, A.C, M.R.., C.F.L., M.T., G.S., N.K., G.A.C, B.A.D., F.V.-M.; methodology, D.D., C.T. and F.V.-M.; software, D.D., C.T. and F.V.-M.; validation, D.D., L.G.D., C.T, A.C, M.R.., C.F.L., M.T., G.S., N.K., G.A.C, B.A.D., F.V.-M.; formal analysis, D.D., C.T. and F.V.-M.; investigation, D.D., C.T. and F.V.-M.; resources, D.D., C.T. and F.V.-M.; data curation, D.D., C.T. and F.V.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.D., L.G.D., C.T, A.C, M.R.., C.F.L., M.T., G.S., N.K., G.A.C, B.A.D., F.V.-M.; writing—review and editing, D.D., C.T. and F.V.-M.; visualization, D.D., L.G.D., C.T, A.C, M.R.., C.F.L., M.T., G.S., N.K., G.A.C, B.A.D., F.V.-M.; supervision, D.D., C.T. and F.V.-M.; project administration, D.D., C.T. and F.V.-M.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Khamis, K.; Njau, B. Patients’ level of satisfaction on quality of health care at Mwananyamala hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC health services research. 2014; 4, 1, 1-8.

- Xesfingi, S.; Vozikis, A. Patient satisfaction with the healthcare system: Assessing the impact of socio-economic and healthcare provision factors. BMC Health Services Research. 2016, 16, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulău, D.; Craiut, L.; Tit, D.M.; Buhas, C.; Tarce, A.G.; Uivarosan, D. Effects of Hospital Decentralization Processes on Patients’ Satisfaction: Evidence from Two Public Romanian Hospitals across Two Decades. Sustainability. 2022, 17;14(8):4818.

- Khan, G.; Kagwanja, N.; Whyle, E.; Gilson, L.; Molyneux, S.; Schaay, N.; Tsofa, B.; Barasa, E.; Olivier, J. Health system responsiveness: a systematic evidence mapping review of the global literature. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2021 Dec;20(1):1-24.

- ORDONANŢĂ DE URGENŢĂ, nr. 48 din 2 iunie 2010. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/119434 (accessed on January 14, 2023).

- LEGE nr. 95 din 14 aprilie 2006. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/71139 (accessed on January 17, 2023).

- Vlădescu, C.; Scîntee, S.G.; Olsavszky, V.; Hernández-Quevedo, C.; Sagan, A. Romania: health system review. Health systems in transition. 2016(18/4).

- Chevreul, K.; Brigham, B.; Durand-Zaleski, I.; Hernández-Quevedo, C. France: Health system review. Health systems in transition. 2015(17/3).

- Daina, L.G.; Sabău, M.; Daina, C.M.; Neamțu, C.; Tit, D.M.; Buhaș, C.L.; Bungau, C.; Aleya, L.; Bungau, S. Improving performance of a pharmacy in a Romanian hospital through implementation of an internal management control system. Science of the Total Environment. 2019, 20, 675:51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgovan, C.; Cosma, S.A.; Valeanu, M.; Juncan, A.M.; Rus, L.L.; Gligor, F.G.; Butuca, A.; Tit, D.M.; Bungau, S.; Ghibu, S. An exploratory research of 18 years on the economic burden of diabetes for the Romanian National Health Insurance System. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020 Jun;17(12):4456.

- Baba, C.O.; Brînzaniuc, A.; Chereches, R.M.; Diana, R.U. Assessment of the reform of the Romanian health care system. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences. 2008;4(24):15-25.

- Ordonanţă de Urgenţă nr. 48 din 2 Iunie 2010. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/119434 (accessed on January 17 2023).

- ORDIN pentru modificarea Anexei nr. 1 la Ordinul ministrului sănătății nr. 1384/2010 privind aprobarea modelului-cadru al contractului de management şi a listei indicatorilor de performanţă a activităţii managerului spitalului public. Available online: http://www.ms.ro/2018/04/12/ordin-pentru-modificarea-anexei-nr-1-la-ordinul-ministrului-sanatatii-nr-1384-2010-privind-aprobarea-modelului-cadru-al-contractului-de-management-si-a-listei-indicatorilor-de-performanta-a-activit/ (accessed on January 17, 2023).

- Păunică, M.; Cosmina, I.; Ștefănescu, A. International migration from public health systems. Case of Romania. Amfiteatru Eco-nomic Journal. 2017;19:46:742-56.

- Mekereș, G.M.; Buhaș, C.L.; Tudoran, C.; Csep, A.N.; Tudoran, M.; Manole, F.; Iova, C.S.; Pop, N.O.; Voiţă, I.B.; Domocoș, D.; Voiţă-Mekereş, F. The practical utility of psychometric scales for the assessment of the impact of posttraumatic scars on mental health. Frontiers in Public Health. 2023;11.

- Merçay, C.; Dumont, J.C.; Lafortune, G. Trends and policies affecting the international migration of doctors and nurses to OECD countries. Health Workforce Policies in OECD Countries: Right Jobs, Right Kills, Right Places. 2016:103-24.

- Tudoran, C.; Velimirovici, D.E.; Berceanu-Vaduva, D.M.; Rada, M.; Voiţă-Mekeres, F.; Tudoran, M. Increased Susceptibility for Thromboembolic Events versus High Bleeding Risk Associated with COVID-19. Microorganisms. 2022 Aug 29;10(9):1738.

- Oşvar, F.N.; Raţiu, A.C.; Voiţă-Mekereş, F.; Voiţă, G.F.; Bonţea, M.G.; Racoviţă, M.; Mekereş, G.M.; Bodog, F.D. Cardiac axis evaluation as a screening method for detecting cardiac abnormalities in the first trimester of pregnancy. Romanian Journal of Morphology and Embryology. 2020 Jan;61(1):137.

- Bogdan, I.; Gadela, T.; Bratosin, F.; Dumitru, C.; Popescu, A.; Horhat, F.G.; Negrean, R.A.; Horhat, R.M.; Mot, I.C.; Bota, A.V.; Stoica, C.N. The Assessment of Multiplex PCR in Identifying Bacterial Infections in Patients Hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Systematic Review. Antibiotics. 2023 Feb 24, 12(3):465.

- Dawn, A.G.; Lee, P.P. Patient satisfaction instruments used at academic medical centers: results of a survey. American Journal of Medical Quality. 2003, 18:6:265-9.

- Otani, K.; Herrmann, P.A; Kurz, R.S. Improving patient satisfaction in hospital care settings. Health Services Management Re-search. 2011, 24:4:163-9.

- Boyer, L.; Francois, P.; Doutre, E.; Weil, G.; Labarere, J. Perception and use of the results of patient satisfaction surveys by care providers in a French teaching hospital. International Journal for quality in health care. 2006 Oct 1, 18(5):359-64.

- Schoenfelder, T.; Klewer, J.; Kugler, J. Determinants of patient satisfaction: a study among 39 hospitals in an in-patient setting in Germany. International journal for quality in health care. 2011, 1:23:5:503-9.

- Steyl, T. Satisfaction with quality of healthcare at primary healthcare settings: Perspectives of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. South African Journal of Physiotherapy. 2020 Jan 1;76(1):1-7.

- Al-Abri, R.; Al-Balushi, A. Patient satisfaction survey as a tool towards quality improvement. Oman medical journal. 2014, 29:1:3.

- Tonio, S.; Joerg, K.; Joachim, K. Determinants of patient satisfaction: A study among 39 hospitals in an inpatient setting in Germany. Int J Qual Health Care. 2011;23:503-9.

- Halsey, M.F.; Albanese, S.A.; Thacker, M. Project of the POSNA Practice Management Committee. Patient satisfaction surveys: an evaluation of POSNA members’ knowledge and experience. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics. 2015, 1:35:1:104-7.

- Ahmad, M.A.; Jameel, A.S. Factors affecting on job satisfaction among academic staff. Polytechnic Journal. 2018 May 30, 8(2).

- Available online: https://www.lege-online.ro/lr-ORDIN-443%20-2019-(212310)-(1).html (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- Mekeres, G.M.; Voiţă-Mekereş, F.; Tudoran, C.; Buhaş, C.L.; Tudoran, M.; Racoviţă, M.; Voiţă, N.C.; Pop, N.O.; Marian, M. Predictors for Estimating Scars’ Internalization in Victims with Post-Traumatic Scars versus Patients with Postsurgical Scars. InHealthcare 2022 Mar 16 (Vol. 10, No. 3, p. 550). MDPI.

- Available online: https://www.spital-copii-timisoara.info/legislatie/data_files/legislatie/13/lege-1-13.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).