1. Introduction

Job-related quality of life is a key indicator for workers' well-being and the sustainability of work structures [

1]. While employment income contributes to the well-being of workers, the quality of job-related life is also a determining factor [

2]. A low level of working life quality is primarily associated with adverse working conditions. A poor working environment, characterized by discrimination, inequality, excessive workload, low job control, and job insecurity, poses a threat to employees' mental health [

3]. Approximately 45% of employees report experiencing risk factors that can negatively affect their mental health [4-6]. Statistical data from OSHA-EU reflect a grim reality, as they prove that work-related stress, anxiety, and depression are the second most common occupational health challenges in Europe. Therefore, it is well acknowledged that occupational stress is one of the most important occupational health issues affecting employees globally [

7]. Healthcare professionals are particularly vulnerable due to occupational constraints and adverse working conditions, such as excessive workload, long working hours, and understaffing [7-8].

Overtime, negative feelings like anxiety, stress, irritability, and burnout may develop as a consequence of their working conditions. According to WHO, emotions of negativity, cynicism or psychological distancing from one's work, and burnout, can have a major negative impact on an employee's health and well-being and, consequently, on the ineffective operation of hospitals. [

9]. Such emotions are often amplified by the lack of recognition of employees' efforts and dedication, as well as the lack of opportunity for professional development [

10]. This reality compels a significant percentage of workers to reevaluate their professional lives and consider alternative career options. A positive work-life balance can result in better patient care and better health outcomes [

11].

Systematic assessment and continuous monitoring of work-related quality of life (WRQoL) are critical for healthcare professionals, particularly those in high-demanding environments such as hospitals, as employee satisfaction is inextricably linked to the quality of care provided to patients [

12].

Reduced quality of working life, especially when combined with burnout, has been associated with weak patient-staff interaction, higher rates of job rotation requests, early retirement or voluntary resignation, and overall reduction in workplace productivity [13-18]. The consequences are also reflected in patient safety outcomes, including higher infection rates, increased medication errors, reduced patient satisfaction, a deteriorated safety culture, and elevated standardized mortality ratios [19-21]

The primary objective of this study is to assess the working-related quality of life (WRQoL) of employees in Greek public hospitals, with an emphasis on identifying key demographic and job-related factors that affect employee well-being. Specifically, our study examined variables such as age, gender, educational level, professional role, years of experience, staff category, hospital category, employment status (permanent or time limited contract) affect employees' perceptions of their professional life.

Our study aims to contribute to the formulation of effective policies for better workplace management in public healthcare institutions, ensuring that both employees and patients benefit from improved outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was designed to assess the quality of working life among employees in the Greek public hospitals. This study included a large population of health professionals (workers and managers from all specialties) employed in twenty-three hospitals of the largest health region in Greece and aims, among other things, to find the determining factors that shape their working quality of life. Data collection took place from May 2023 to February 2024.

Sampling frame: Our study focused on the total number of staff (n = 23,941) in public hospitals (n = 23) in Attica's 1st Health Region. To ensure a representative sample, cluster sampling was used. First, hospitals were divided into five categories based on their specific purpose and services provided: a) general/main duty hospitals, b) pediatric hospitals, c) special purpose hospitals, d) other/supportive hospitals, and 5) oncology hospitals. Subsequently, the staff of the hospitals were divided into four clusters depending on their specialty: a) medical, b) nursing, c) administrative/technical, and d) other. Out of the total number of employees (23.941), 69% work in general/main duty hospitals, 13% in pediatric hospitals, 7% in special purpose hospitals, 3% in other/supportive hospitals, and 8% in oncology hospitals. Furthermore, 27% are physicians, 40% are nurses, 11% are administrative/technical staff, and 22% fall into other groups. To ensure that the sample (n) of each group is representative, the following parameters have been set: N = 23,941 (total population); Z = standard deviation at 95% confidence level (Z = 1.96), D = tolerable difference (3%). Τhe sample size was calculated using Cochran’s formula, adjusted for finite populations. Given the foregoing, the total sample size (n) equates to 1022 employees. The proportion of staff per hospital type was maintained in the sample, as was the ratio of employees per cluster.

Tools: The WRQoL scale, developed by researchers at the University of Portsmouth in the UK, was used for the purposes of the present study. It comprises six subscales that measure Work Control, General Well-being, Work-Life Balance, Job Satisfaction, Occupational Stress, and Working Conditions [

12,

22] and includes 24 items, each rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The questionnaire has already been translated to Greek and validated for use in Greek-speaking populations [

23].

Statistical analysis:The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 26.0. The normality of the data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. Results indicated that all dimensions deviated from a normal distribution; therefore, non-parametric tests were applied. Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, variance, frequencies, and percentages) were used to describe the sample. Subsequently, all questionnaire dimensions were categorized into three levels (low, average, high) based on the calculated percentiles and were compared across key variables (e.g., age group, gender, hospital type) using the Chi-square test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance. The internal coherence check of the questionnaire was carried out with the Cronbach's alpha indicator.

Ethics: Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of West Attica (No. 37230/05-04-2023) and from all participating hospitals. This research was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

3. Results

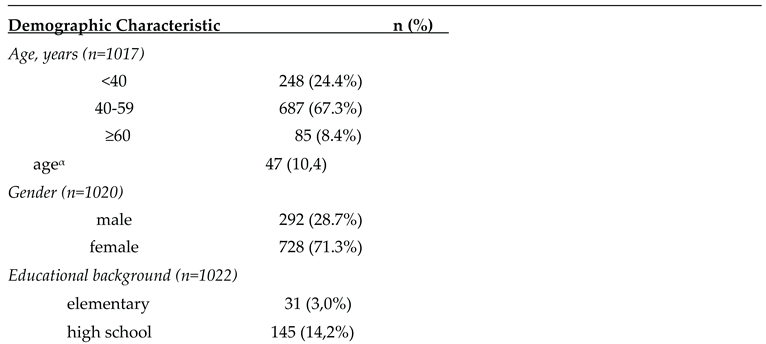

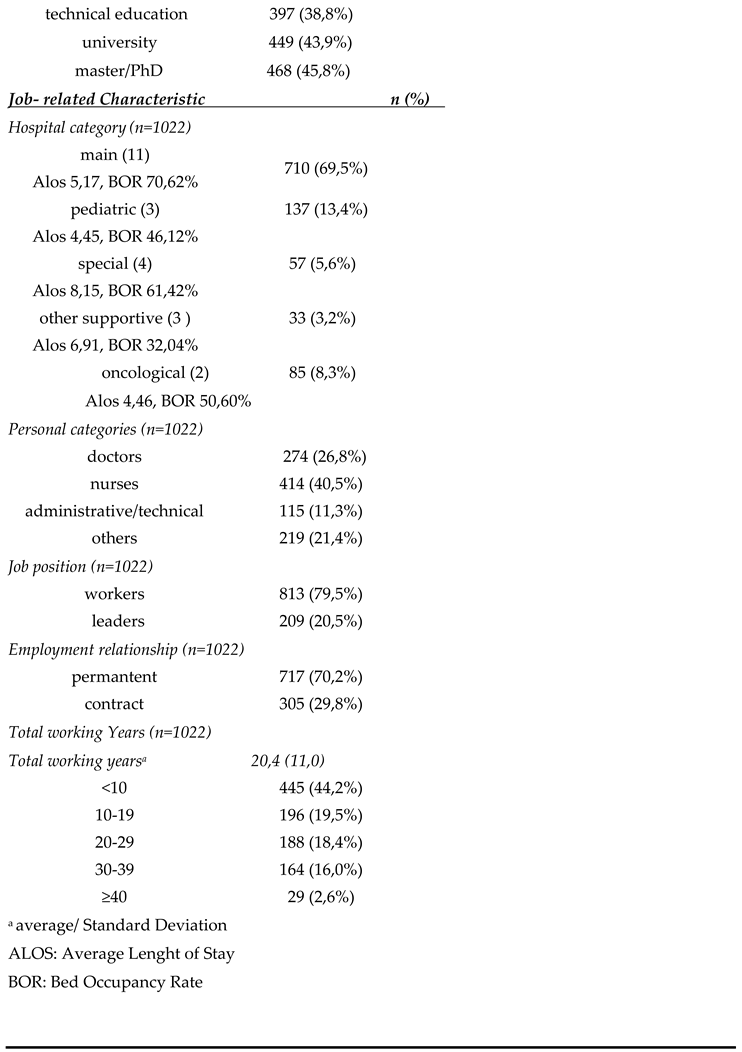

At the end of the survey period, 1022 questionnaires were collected (100% of the required number). The demographic and job-related characteristics of the participants are presented in

Table 1. The mean age of the employees was 47.0 years (standard deviation = 10.4), the median age was 48 years, the youngest participant was 21 years old and the oldest was 72 years old. The majority of employees were women (71.3%). Regarding their professional characteristics, most employees were simple staff (79.5%), while 20.5% were managers. Additionally, 70.2% were permanent employees, while 29.8% were on contract. Most worked in main hospitals. The average total work experience was 20.4 (standard deviation = 11.0), with the lowest value at 0.1 years and the highest value at 50 years. The main hospitals had a higher Bed Occupancy Rate (BOR), and the special ones followed.

Table 2 presents the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the 6 dimensions of the Work-Related Quality of Life (WRQoL) scale. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient ranged from 0.71 to 0.86, indicating excellent reliability of the questionnaire.

3.1. Descriptive Results for the 6 Dimensions of the Work-Related Quality of Life (WRQoL) Scale and Classification Based on WRQoL Component Levels

3.1.1. Descriptive Results

Table 3 shows the mean, standard deviation, and variance for each parameter of quality of life of the sample. All dimensions of the questionnaire are placed at the moderate level of the scale. Therefore, the final score (74) also corresponds to the moderate level.

3.1.2. WRQoL Component Levels

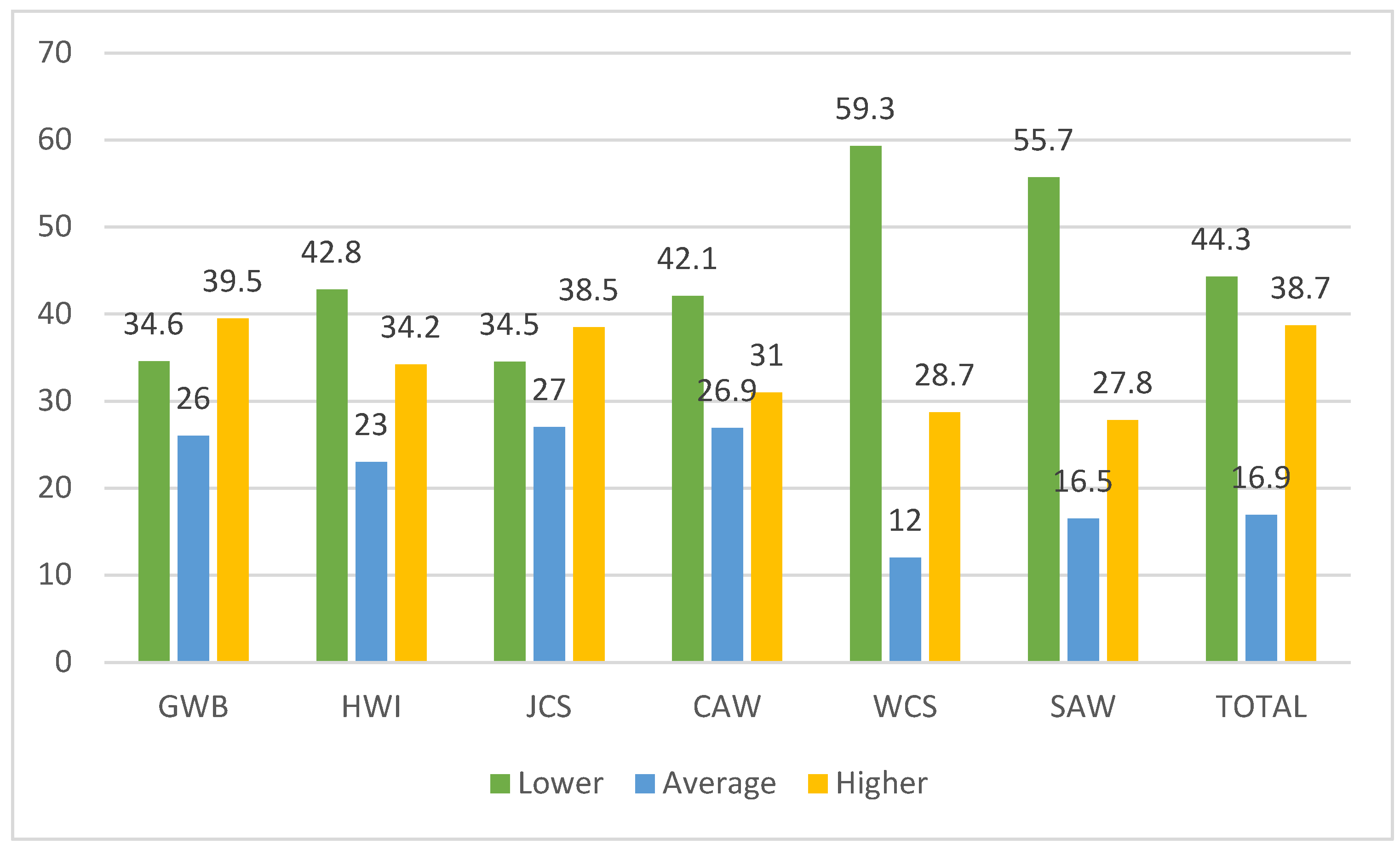

According to the Work-Related Quality of Life (WRQoL) scale, the level of quality of life is categorized as low, medium, and high. The low level of work quality of life based on the total score corresponds to 44.3% of employees, while 38.7% corresponds to a high level and 16.9% to the medium level. Respondents, at a percentage of 39.5% assess their general well-being as good, 65.8% rate their work-home interface as low or moderate, and 34.5% rate their job satisfaction as low. Additionally, 42.1% of respondents rank their ability to control work as low. The majority of employees, at 55.7%, rate working conditions as low. Regarding stress at work, 27.8% report that it is high. The detailed score is reflected in

Table 4 and

Figure 1.

3.2. Impact of Demographic and Job-Related Predictors on Its Six Dimensions (WRQoL)

Results of the impact of demographic and job-related predictors for the 6 dimensions of the questionnaire (WRQoL), per dimension, are presented in

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9 and

Table 10. It is noted that in detail they refer only to cases that are statistically significant.

3.2.1. General Well-Being (GWB)

The age factor yielded the following results: Respondents under 40 years old rated the GWB dimension at a low level of 45.8%. The age group 40-60 years old rated it at a high level of 43.10%, as did the >60 years old at a similar rate of 41.3%. The gender factor differentiated in absolute terms as 100% of men perceive this dimension at a low level, whereas women rate it at a low level of 17%, at a medium level at 36.4%, and at a high level at 55.4%.

Regarding the education factor, employees with elementary education score 38.7% at the low level, high school graduates at 24.1%, technical graduates at 28.3%, and university graduates at 43.4%. At the medium level, the scores are 19.4%, 26.9%, 26.3%, and 25.7 %, respectively. At the high level, the scores range from 41.95% to 49%, 45.55%, and 30.9% at the corresponding levels of education. The results of the work-related predictors and the distribution of scores among the three levels of WRQoL are as follows: In the work position factor, workers perceive the GWB dimension at a rate of 35.5% at a low level, at a rate of 27.8% at a medium level, and 36.7% at a high level. In contrast, 50.2% of leaders highly perceive this element. Regarding the employment relationship, permanent employees score 43.2% at a high level, while contract employees score 30.8%. The majority of contract employees, at 44.6%, correspond to the low level.

The employee’s specialty also presents significant statistical differences. Most doctors perceive this factor at a low level (56.6%), nurses at 23%, administrators at 30.4%, and others at 31.1%. At the high level, the scores, by occupational category, are 30.1% for doctors, 46.2% for nurses, 52.2% for administrators, and 44.3% for others.

The total years of working experience had the following results: A significant proportion of employees with <10 years of experience, 43.4%, are placed at a low level, while those over >40 are at 44.8% at the medium level. Most employees in the 30-39 category had a perception of well-being at a high level of 55.5%, followed by the 20-29 group at the same level at 39.4%.

The type of hospital also presents statistically significant differences, with a lower sense of well-being perceived by employees in main and specialist wards, an average sense by employees in pediatrics, and a higher sense by employees in support wards. The detailed results of the GWB dimension are shown in

Table 5.

3.2.2. Home-Work Interface (HWI)

The results regarding demographic factors in the dimension are as follows: The age factor shows statistical significance across the three age groups. Younger employees (<40 years) predominantly perceive HWI at a low level, with 46.2%. In the 40–60 age group, responses are more evenly distributed, with 36.8% rating it at a medium level and 37.9% at a high level. Employees over 60 show similar percentages across all three levels, with the highest percentage (37.3%) corresponding to the low level. Employees over 60 show similar percentages across all three levels, with the highest percentage (37.3%) corresponding to the low level. In terms of gender, no significant differences were observed. However, educational background reveals statistical significance. Most employees with only elementary education (45.2%) perceive HWI at a high level. Similarly, a majority of high school graduates (40.7%) also correspond to the high level, whereas technical education graduates mainly rate HWI at a medium level (36.3%), and university graduates at a low (36.5%).

Regarding job-related predictors, statistical significance is found across all categories, with profession, hospital type, and total years of working experience being the most significant factors. Doctors predominantly perceive WHI at a low level (39.4%), followed by nurses (33.8%). In contrast, administrative and other employees report high levels of WHI at rates of 44.3% and 40.6%, respectively. Employees with fewer years of experience and those with the most years classify WHI mainly at the low level (36% and 41.4%, respectively). Concerning the type of hospital, employees in pediatric hospitals mostly perceive WHI at a low level (45.3%). The detailed results of the WHI dimension are shown in

Table 6.

3.2.3. Job and Career Satisfaction (JCS)

The results for the JCS dimension, with respect to demographic characteristics, show statistical significance only in the age category. As presented in

Table 7, the majority of employees aged under 40 years (45.8%) perceive their job satisfaction at a low level. In contrast, employees aged over 60 years predominantly classify their job satisfaction at a high level.

Regarding work-related predictive factors, three categories demonstrate strong associations and statistical significance. Specifically, with respect to job position, 38.1% of workers report low levels of job satisfaction, whereas 53.1% of leaders report high levels. Employees with less than 10 years of total work experience predominantly fall within the low level (41.1%), while those with more than 40 years of experience also mainly report low satisfaction (51.7%). Conversely, employees within the 20–29 and 30–39 years age groups report high levels of job satisfaction, at rates of 44.7% and 47.0%, respectively.

Employees working in pediatric hospitals demonstrate a low sense of job satisfaction (43.1%), whereas those employed in special and supportive hospitals report high levels of satisfaction, with rates of 56.1% and 72.7%, respectively.

A detailed presentation of the results is provided in

Table 7.

3.2.4. Control at Work (CAW)

The results regarding control at work, as presented in

Table 8, show statistical significance in demographic characteristics only within the age category. Specifically, employees aged 40–60 years and over 60 years predominantly place this dimension at the middle level, with rates of 40.8% and 40.0%, respectively. Employees under 40 years old mostly rate their control at work at a low level (38.8%), while 23.3% place it at a high level.

Regarding job-related predictors, all categories -except for the type of occupation - demonstrate statistically significant differences and are indeed at a high level. Differences are also observed in the employment relationship category, where 25.1% of permanent employees and 38.4% of contract employees report low levels of perceived control at work. Employees with fewer years of work experience (less than 10 years) report low levels of control at a rate of 40.3%, followed by those with 10–19 years of experience (38.0%). In contrast, the majority of the other groups rate this dimension at the middle level.

Concerning the type of hospital, employees in pediatric hospitals report the highest percentages of low control, followed by those in main hospitals, at rates of 43.8% and 28.8%, respectively. Conversely, employees in supportive and special hospitals report the highest percentages of high levels of perceived control, at 54.5% and 43.9%, respectively. The analytical results are presented in

Table 8.

3.2.5. Working Conditions (WCS)

The demographic characteristics of age and level of education show statistically significant differences in the WCS dimension, as shown in

Table 9. Specifically, within the age group of employees with less than 10 years of experience, 45.5% rate their working conditions at a low level and 20.0% at a high level. The remaining two age groups predominantly place their working conditions at a middle level.

Regarding level of education, employees with elementary and high school education report higher rates of working conditions at a high level, with percentages of 38.7% and 37.2%, respectively.

Four job-related predictors show statistically significant differences. In terms of job position, 38.5% of workers and 23.9% of leaders rate their working conditions at a low level. Regarding occupation, 40.5% of doctors and 37.5% of nurses also report low levels, while administrative staff predominantly places their working conditions at a high level (51.3%).

Total years of work experience further differentiate the results: 43.1% of employees with less than 10 years of experience, 38.0% of those with 10–29 years, and 37.0% of those with more than 40 years, all classify their working conditions at a low level. In contrast, employees with 30–39 years of experience predominantly rate their working conditions at a high level (38.8%).

Finally, regarding the type of hospital, employees in pediatric and main hospitals rate their working conditions at a low level, with percentages of 48.9% and 36.2%, respectively. Conversely, employees in supportive and special hospitals report predominantly high levels of working conditions, at rates of 69.7% and 50.9%, respectively.

Detailed results are presented in

Table 9.

3.2.6. Stress at Work (SAW)

The results of the analysis of work-related stress (SAW) factors showed statistically significant differences, mainly between work-related predictors. Of the demographic predictors, only educational background had marginal statistical significance, but there was a high statistical significance among those holding a master's/PhD.

Specifically for the educational background, the highest levels of work stress were reported by employees with primary education at a rate of 48.4%. This trend is reduced among workers with a higher level of education, as university graduates (25.6%) and those with master's or doctoral degrees (22.3%) reported lower levels of stress.

In terms of employment status, permanent employees reported slightly higher levels of low stress (27.8%) compared to contract employees (20.0%), although contract workers showed a higher tendency to experience average levels of stress (50.5%).

In the type of work factor, administrative and technical staff reported higher rates of stress at a high level (40.9%) compared to doctors (24.1%) and nurses (23.7%).

Finally, in relation to the type of hospital, employees in supportive and special hospitals reported the highest rates, with 48.5% and 43.9%, respectively.

Detailed results are presented in

Table 10.

3.3. Summary of the Six Dimensions of the Questionnaire Based on Demographic and Job-Related Predictors affecting the Quality of Work Life of Employees in Greek Public Hospitals.

After presenting the results for each dimension of the questionnaire in detail,

Table 11 provides a concise overview of the examined prognostic predictors and their impact, or lack thereof, on the quality of working life of employees. According to the data in

Table 11 of the demographic characteristics, age was the most influential (in 5 dimensions) followed by the level of education (in 4 dimensions). Gender was differentiated only in the GWB dimension. Work-related characteristics showed high statistics, with the most significant being the hospital category that affects all dimensions of working quality of life. This is followed by the job and the total years of work (5 dimensions) and then the employment relationship and the job (4 dimensions).

4. Discussion

Our study focused on the assessment of working-related quality of life (WRQoL) of employees in the public hospitals of the 1st Health Region of Attica, which includes the busiest and most specialized hospitals in the country, such as pediatric, oncology and specialty hospitals. The study revealed significant challenges highlighting the need for targeted actions to enhance employee work-related quality of life, improve working conditions, and providing better support services in Greek public hospitals.

Demographic and job-related factors influencing the quality of employee work life were determined. Variables of influence, including age, years of total work experience, job position, hospital category and employment status, which were statistically significant in this study, can be used for targeted actions both by hospital administrations and at central Health District level.

The overall WRQoL scores, as well as the subscale scores, were at a moderate range, in agreement with the findings of a cross-sectional study among healthcare professionals in Italy [

24] and doctors in Poland [

25]. Similar results were presented by the study in Greece that evaluated the Greek version of the WRQoL scale in nurses [

23]. The high percentage of employees, who rank at the low level of overall quality of life (44.8%), is an important finding and a worrying message for employers.

Evaluating the subscales further, Job Satisfaction (JCS) and General Well-being (GWB) maintain high scores, but with a significant percentage of employees at a low level (~35%). Work-life balance (HWI) is negatively affected, due to overtime, shifts, time pressure or personal obligations. The most negative findings concern working conditions (WCS) at 59.3% and work stress (SAW), as a high percentage of employees, amounting to 27.8%, is classified on a high scale.

A significant percentage of employees (almost 50%) feel that they do not have sufficient control or autonomy over their work or working conditions. This can mean that employees feel that decisions about their work or how they perform their tasks are largely determined by others. A sense of limited control at work is a major risk factor for work stress and mental health, especially in the healthcare sector [26-29].

In fact, a significant percentage of high-level anxiety was identified by the present study. Many respondents indicated that one of the main issues of their work environment is stress and anxiety. Every day, they encounter a wide range of negative emotions caused by their workplace. These include worry, anxiety, frustration, and despair, which can be attributed to many factors [30-31]. Nurses have expressed discontent with their professional employment, claiming a heavy workload [

33] long working hours and shift work [32-33], low compensation, and little gratitude and credit for their efforts. It is crucial to emphasize that during global health emergencies, medical and nursing professionals must remain resilient and manage the circumstances despite any personal issues and concerns.

The assessment of working conditions at a low level is also identical to the data collected from the same study sample in the survey for the assessment of the safety climate in Greek public hospitals [

34].

Analyzing the findings of our survey based on demographic and job-related characteristics, by dimension of the WRQoL scale, further important findings are identified. The GWB dimension presents important statistics in all the controlled variables of the study. In general, younger workers score higher percentages in this dimension. Possible causes include lower experience and increased adjustment anxiety. Gender varies widely, with men scoring very low, in contrast to a study among health professionals in Poland that showed no significant differences between sexes [

25]. Based on the findings of our research, well-being at work is closely linked to holding senior positions, with permanent jobs, as well as long working experience. General well-being at work is identified with these characteristics in several studies [34-35]. Work-related rewards and development have been positively correlated with employee satisfaction and career advancement has been associated with a lower risk of career change. The quality of services provided by employees also appears to be significantly influenced by alternative future career plans [36-38]. Low levels of work well-being also seem to reflect the experiences of individuals working in main and special hospitals. Compassion fatigue and secondary psychological trauma may affect medical professionals who treat patients and especially children in suffering, because they provide care to victims of abuse or patients with life-threatening illnesses [39-43]. In fact, the lowest scores in this dimension were among doctors.

The HWI dimension assesses work-life balance. According to our findings, age, among demographic characteristics, is the factor that influences this dimension the most, as younger people score lower. It seems that, as age increases, so does the ability to manage work-life balance, due to better demarcation and experience. Education also affects this dimension: as the educational level increases, the work-house interface is reduced. This is consistent with several studies [44-46]. All job-related characteristics examined affect this dimension. A particularly low level was found among doctors, especially younger ones, who clearly have less work experience and particularly those who work in pediatric hospitals. A lack of work-life balance significantly reduces job satisfaction and mental health [47-49].

Control at work (CAW) scores differ significantly when age, job position, employment relationship, years of working experience and category of hospital is examined, while no statistical difference was found in relation to the employees specialty. Younger workers show less control at work, while those over 40 tend to be placed at the middle level. This is in line with the international literature, where older workers often have increased work autonomy due to experience and senior positions [

50].

Job satisfaction (JCS) is also related to age and experience, as younger and significantly less experienced showed with the lowest scores in job satisfaction and work-related quality of life. This finding is consistent with other studies for the less experienced participants [51-53]. On the opposite side, employees in positions of responsibility experience higher satisfaction, which is also consistent with the international literature [54-56]. Employees in pediatric hospitals show the lowest level of satisfaction, followed by those who work in the main ones. Gender does not seem to affect this dimension. Regarding working conditions (WCS), the factors that differentiate the score of respondents are: age – the youngest, the lower–, educational background, job position, category of staff, with doctors, especially young people, with less experience, working in pediatric hospitals, giving the lowest scores.

Findings regarding work-related stress (SAW), show that lower levels of education are associated with higher levels of stress at work, while university graduates and postgraduate degree holders experience lower levels of stress. Many studies have shown opposite results, i.e., higher the level of education, the greater the requirements for efficiency, responsibilities and competitiveness, mismatch between qualifications and rewards [57-58].

Overall, the findings of the present study highlight the complexity and multifactorial nature of work-related quality of life in public hospitals, underlying the need for targeted interventions at organizational and political level.

5. Conclusions

The present study highlights critical challenges to the quality of life of employees in Greek public hospitals. Key demographic and work-related factors have a significant impact on employee experiences, highlighting the urgent need for strategic interventions. Improving working conditions, enhancing workers' autonomy and supporting their career development must be a priority to protect the well-being of healthcare workers and maintain high quality care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.C.; Data curation, L.P.; Investigation, O.C.; Methodology, P.S.; Project administration, V.P.; Supervision, G.D.; Validation, O.C.; Writing—original draft preparation, O.C.; Writing—review and editing, O.C. and M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of West Attica (No. 37230/05-04-2023. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data collected through questionnaires are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions but may be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WRQoL |

Work-Related Quality of Life |

| GWB |

General well-being, |

| HWI |

Home-work interface |

| JCS |

Job and career satisfaction, |

| CAW |

Control at work |

| WCS |

Working conditions |

| SAW |

Stress at work |

References

- Thakur, V.; Pathak, G.S. Employee Well-Being and Sustainable Development: Can Occupational Stress Play Spoilsport. PROBL EKOROZW 2023, 18, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, T.K. Work Related Well-Being Is Associated with Individual Subjective Well-Being. Ind Health 2021, 60, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Mental Health at Work. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-at-work (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). Psychosocial Risks and Stress. Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/en/themes/psychosocial-risks-and-stress (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). European Survey of Enterprises on New and Emerging Risks (ESENER). Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/en/facts-and-figures/esener (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). ESENER 3: Summary Overview—3rd European Survey of Enterprises on New and Emerging Risks. Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/en/publications/esener-3-summary-overview-3rd-european-survey-enterprises-new-and-emerging-risks (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Rink, L.C.; Oyesanya, T.O.; Adair, K.C.; Humphreys, J.C.; Silva, S.G.; Sexton, J.B. Stressors Among Healthcare Workers: A Summative Content Analysis. Global Qualitative Nursing Research 2023, 10, 23333936231161127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portoghese, I.; Galletta, M.; Coppola, R.C.; Finco, G.; Campagna, M. Burnout and Workload Among Health Care Workers: The Moderating Role of Job Control. Safety and Health at Work 2014, 5, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Burn-out an Occupational Phenomenon. Available online: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/frequently-asked-questions/burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Brun, J.-P.; Dugas, N. An Analysis of Employee Recognition: Perspectives on Human Resources Practices. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2008, 19, 716–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zhao, Y.; While, A. Job Satisfaction among Hospital Nurses: A Literature Review. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2019, 94, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Laar, D.; Edwards, J.A.; Easton, S. The Work-Related Quality of Life Scale for Healthcare Workers. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2007, 60, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewa, C.S.; Loong, D.; Bonato, S.; Thanh, N.X.; Jacobs, P. How Does Burnout Affect Physician Productivity? A Systematic Literature Review. BMC Health Serv Res 2014, 14, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewa, C.S.; Jacobs, P.; Thanh, N.X.; Loong, D. An Estimate of the Cost of Burnout on Early Retirement and Reduction in Clinical Hours of Practicing Physicians in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res 2014, 14, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Mungo, M.; Schmitgen, J.; Storz, K.A.; Reeves, D.; Hayes, S.N.; Sloan, J.A.; Swensen, S.J.; Buskirk, S.J. Longitudinal Study Evaluating the Association Between Physician Burnout and Changes in Professional Work Effort. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2016, 91, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fibuch, E.; Ahmed, A. PHYSICIAN TURNOVER: A COSTLY PROBLEM. Physician Leadersh J 2015, 2, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koca, M.; Deniz, S.; İnceoğlu, F.; Kılıç, A. The Effects of Workload Excess on Quality of Work Life in Third-Level Healthcare Workers: A Structural Equation Modeling Perspective. Healthcare 2024, 12, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexton, J.B.; Adair, K.C. Forty-Five Good Things: A Prospective Pilot Study of the Three Good Things Well-Being Intervention in the USA for Healthcare Worker Emotional Exhaustion, Depression, Work–Life Balance and Happiness. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e022695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welp, A.; Meier, L.L.; Manser, T. Emotional Exhaustion and Workload Predict Clinician-Rated and Objective Patient Safety. Front. Psychol. 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.H. Hospital Nurse Staffing and Patient Mortality, Nurse Burnout, and Job Dissatisfaction. JAMA 2002, 288, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babapour, A.-R.; Gahassab-Mozaffari, N.; Fathnezhad-Kazemi, A. Nurses’ Job Stress and Its Impact on Quality of Life and Caring Behaviors: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Nurs 2022, 21, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Laar, D.; Edwards, J.A.; Easton, S. The Work-Related Quality of Life (WRQoL) Scale: A Measure of Quality of Working Life; University of Portsmouth: Portsmouth, UK, 2013; Available online: https://www.qowl.co.uk/docs/WRQoL%20individual%20booklet%20Dec2013.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Katsikavali, V.; Galani, P.; Rodoti, E.; Kaitelidoy, D.; Lemonidou, C.; Sourtzi, P. Translation and Validation of the Work-Related Quality of Life Scale (WRQoL) in the Greek Language. Nurs. Care Res. 2022, 64, 267–277. [Google Scholar]

- Ruotolo, I.; Sellitto, G.; Berardi, A.; Panuccio, F.; Simeon, R.; D’Agostino, F.; Galeoto, G. Validation of the Work-Related Quality of Life Scale in Rehabilitation Health Workers: A Cross-Sectional Study. La Medicina del Lavoro 2024, 115, e2024025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakimów, K.; Ciesielka, J.; Bonczek, M.; Rak, J.; Matlakiewicz, M.; Majewska, K.; Gruszczyńska, K.; Winder, M. Work-Related Quality of Life among Physicians in Poland: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochuvilayil, T.; Fernandez, R.S.; Moxham, L.J.; Lord, H.; Alomari, A.; Hunt, L.; Middleton, R.; Halcomb, E.J. COVID-19: Knowledge, Anxiety, Academic Concerns and Preventative Behaviours among Australian and Indian Undergraduate Nursing Students: A Cross-sectional Study. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2021, 30, 882–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiptulon, E.K.; Elmadani, M.; Limungi, G.M.; Simon, K.; Tóth, L.; Horvath, E.; Szőllősi, A.; Galgalo, D.A.; Maté, O.; Siket, A.U. Transforming Nursing Work Environments: The Impact of Organizational Culture on Work-Related Stress among Nurses: A Systematic Review. BMC Health Serv Res 2024, 24, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasin, H.; Johari, Y.C.; Jamil, A.; Nordin, E.; Hussein, W.S. The Harmful Impact of Job Stress on Mental and Physical Health. IJARBSS 2023, 13, Pages 961–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson-Koku, G.; Grime, P. Corrigendum: Emotion Regulation and Burnout in Doctors: A Systematic Review. Occupational Medicine 2019, 69, 304–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, T.; Yip, P. Depression, Anxiety and Symptoms of Stress among Hong Kong Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. IJERPH 2015, 12, 11072–11100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, S.; Hasan, A.A.; Musleh, M. Work Stress, Coping Strategies and Levels of Depression among Nurses Working in Mental Health Hospital in Port-Said City. International Journal of Culture and Mental Health 2018, 11, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, M.; Ferrie, J.E.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Shipley, M.J.; Stansfeld, S.A.; Marmot, M.G.; Ahola, K.; Vahtera, J.; Kivimäki, M. Long Working Hours and Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression: A 5-Year Follow-up of the Whitehall II Study. Psychol. Med. 2011, 41, 2485–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’Ora, C.; Griffiths, P.; Ball, J.; Simon, M.; Aiken, L.H. Association of 12 h Shifts and Nurses’ Job Satisfaction, Burnout and Intention to Leave: Findings from a Cross-Sectional Study of 12 European Countries. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e008331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christofilea, O.; Farantos, G.; Psaridi, L.; Tsaousi, M.; Sartzi, S.; Dounias, G. Assessment of Workplace Safety Climate among Healthcare Workers: A Case Study of the Public Sector Hospitals in Greece. ESJ 2025, 21, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, P.K.; Das, S. Psychological Resilience of Frontline Healthcare Workers in India: A Mixed-Methods Exploratory Study during COVID-19 Pandemic in India. Preventive Medicine: Research & Reviews 2024, 1, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, K.; Shahane, S.; D’Souza, W. Role of Demographic and Job-Related Variables in Determining Work-Related Quality of Life of Hospital Employees. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine 2017, 63, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nantsupawat, A.; Srisuphan, W.; Kunaviktikul, W.; Wichaikhum, O.-A.; Aungsuroch, Y.; Aiken, L.H. Impact of Nurse Work Environment and Staffing on Hospital Nurse and Quality of Care in Thailand: Work Environment and Staffing on Outcomes. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 2011, 43, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krepia V, Kourakos M, Kafkia T. Special Article Job Satisfaction of Nurses: A Literature Review. Int J Caring Sci [Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 18];16:1754. Available from: www.internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org.

- Sabo, B.M. Compassion Fatigue and Nursing Work: Can We Accurately Capture the Consequences of Caring Work? Int J of Nursing Practice 2006, 12, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meadors, P.; Lamson, A. Compassion Fatigue and Secondary Traumatization: Provider Self Care on Intensive Care Units for Children. Journal of Pediatric Health Care 2008, 22, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Li, S.; Mo, B.; Liao, Q.; Luo, W.; Zhu, S.; Sun, L. Compassion Fatigue and It Influencing Factors among Pediatric Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Survey. BMC Psychol 2024, 12, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehene, E.; Asherman, A.; Goldzweig, G.; Simana, H.; Brezner, A. Secondary Traumatic Stress among Pediatric Nurses: Relationship to Peer-Organizational Support and Emotional Labor Strategies. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 2024, 74, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakdaman, N.; Naghavi, A.; Samiee, F.; Kalhor, F. Compassion Fatigue, Compassion Satisfaction and Related Factors in Pediatric Wards: A Narrative Review Study. Global Pediatric Health 2024, 11, 2333794X241299939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Klerk, M.; Mostert, K. Work–Home Interference: Examining Socio-Demographic Predictors in the South African Context. SA j. hum. resour. manag. 2010, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, R.; Xia, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Dinçer, H.; Yüksel, S. Analysis of Environmental Activities for Developing Public Health Investments and Policies: A Comparative Study with Structure Equation and Interval Type 2 Fuzzy Hybrid Models. IJERPH 2020, 17, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigi, M.; Shirmohammadi, M.; Kim, S. Living the Academic Life: A Model for Work-Family Conflict. WOR 2016, 53, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haar, J.M.; Russo, M.; Suñe, A.; Ollier-Malaterre, A. Outcomes of Work–Life Balance on Job Satisfaction, Life Satisfaction and Mental Health: A Study across Seven Cultures. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2014, 85, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Johnson, R.C.; Kiburz, K.M.; Shockley, K.M. Work–Family Conflict and Flexible Work Arrangements: Deconstructing Flexibility. Personnel Psychology 2013, 66, 345–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunau, T.; Bambra, C.; Eikemo, T.A.; Van Der Wel, K.A.; Dragano, N. A Balancing Act? Work–Life Balance, Health and Well-Being in European Welfare States. European Journal of Public Health 2014, 24, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grund, C.; Rubin, M. The Role of Employees’ Age for the Relation Between Job Autonomy and Sickness Absence. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine 2021, 63, 800–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, M.H.; Hussain, L.R.; Williams, K.N.; Grannan, K.J. Work-Related Quality of Life of US General Surgery Residents: Is It Really so Bad? Journal of Surgical Education 2017, 74, e138–e146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanaugh, J.; Duffy, J.A.; Lilly, J. The Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Demographic Variables for Healthcare Professionals. Management Research News 2006, 29, 304–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, H.R.; Akbarfahimi, M.; Ghaffari, A.; Kamali, M.; Rassafiani, M. Relationship between Work-Related Quality of Life and Job Satisfaction in Iranian Occupational Therapists. Occupational Therapy International 2021, 2021, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shintyawati, S.; Suhana, S.; Ali, S.; Indriyaningrum, K. The Role of Leadership, Organizational Culture, and Job Satisfaction in Improving Employee Performance. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference of Multidisciplinary Studies, ICMS 2023, 12 July 2023, Semarang, Indonesia; EAI: Semarang, Indonesia, 2023.

- Syed Ali Raza; Sara Qamar Yousufi Transformational Leadership and Employee’s Career Satisfaction: Role of Psychological Empowerment, Organisational Commitment, and Emotional Exhaustion. AAMJ 2023, 28, 207–238. [CrossRef]

- Gebreheat, G.; Teame, H.; Costa, E.I. The Impact of Transformational Leadership Style on Nurses’ Job Satisfaction: An Integrative Review. SAGE Open Nursing 2023, 9, 23779608231197428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunau, T.; Siegrist, J.; Dragano, N.; Wahrendorf, M. The Association between Education and Work Stress: Does the Policy Context Matter? PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Sánchez, N.; Fernández Puente, A. C. Educational and skill mismatches: differential effects on job satisfaction. A study applied to the Spanish job market. Estudios Econ. 2015, 41, 261–281. Available from: https://rej.uchile.cl/index.php/EDE/article/view/37254.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).