Submitted:

24 December 2024

Posted:

26 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

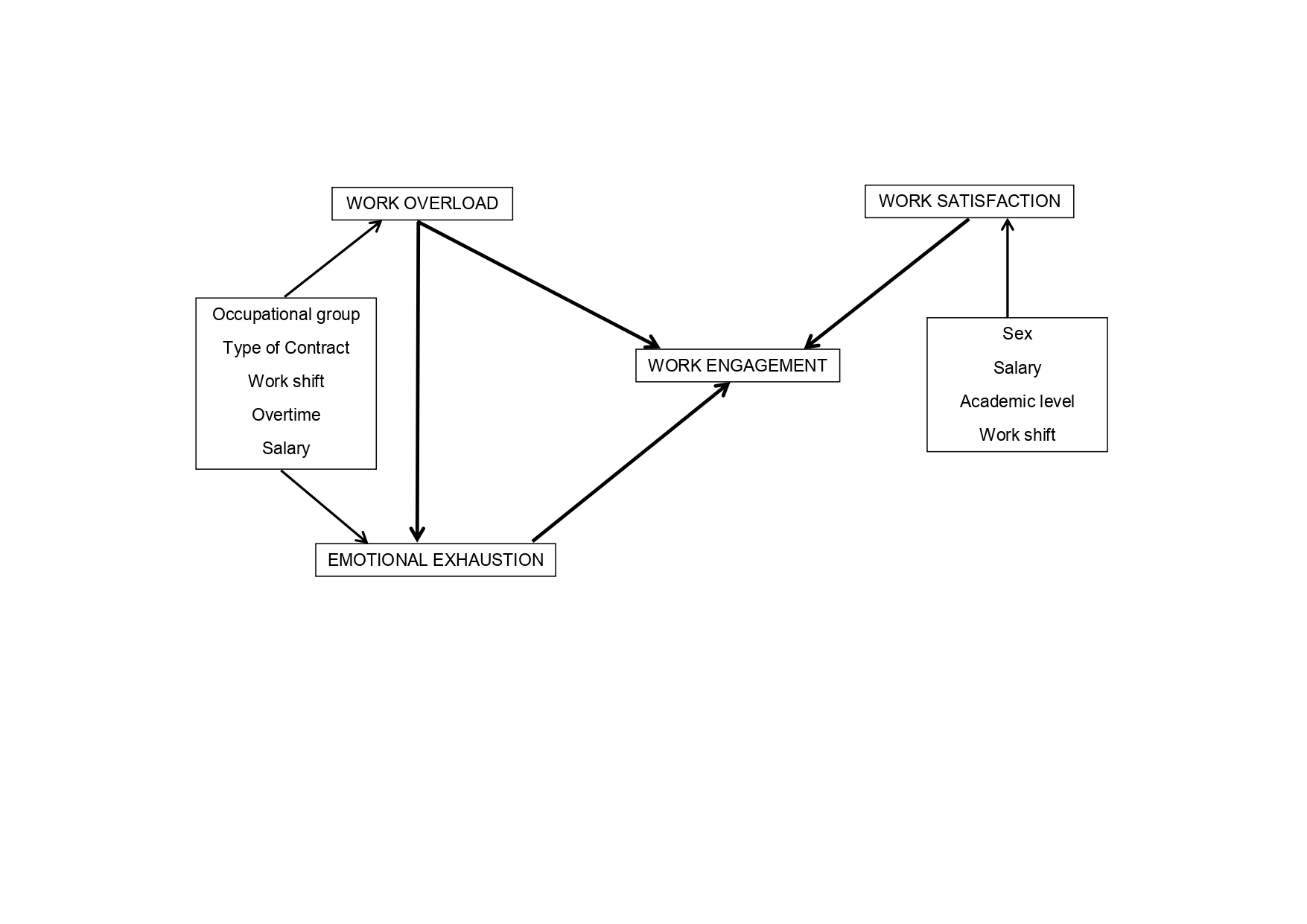

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Sample

2.2. Instruments and Variables

2.3. Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Factors Associated with Work Engagement

3.2. Factors Associated with Work Overload

3.3. Factors Associated with Work Satisfaction

3.4. Factors Associated with Emotional Exhaustion

3.5. Effect of Work Engagement, Work Overload, Work Satisfaction and Emotional Exhaustion on Healthcare Professionals

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UWES-9 | The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale |

| MBI | Maslach Burnout Inventory |

References

- Ni, Y. xia; Xu, Y.; He, L.; Wen, Y.; You, G. ying Relationship between Job Demands, Work Engagement, Emotional Workload and Job Performance among Nurses: A Moderated Mediation Model. Int Nurs Rev 2024. [CrossRef]

- Debets, M.; Scheepers, R.; Silkens, M.; Lombarts, K. Structural Equation Modelling Analysis on Relationships of Job Demands and Resources with Work Engagement, Burnout and Work Ability: An Observational Study among Physicians in Dutch Hospitals. BMJ Open 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohrabizadeh, S.; Sayfouri, N. Antecedents and Consequences of Work Engagement Among Nurses. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2014, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Gan, Y.; Jiang, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, F.; Liu, J.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. Job Satisfaction and Its Associated Factors Among General Practitioners in China. J Am Board Fam Med 2020, 33, 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildiz, B.; Yildiz, T. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analytical Synthesis of the Relationship between Work Engagement and Job Satisfaction in Nurses. Perspect Psychiatr Care 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bogaert, P.; Van Heusden, D.; Timmermans, O.; Franck, E. Nurse Work Engagement Impacts Job Outcome and Nurse-Assessed Quality of Care: Model Testing with Nurse Practice Environment and Nurse Work Characteristics as Predictors. Front Psychol 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rollins, A.L.; Eliacin, J.; Russ-Jara, A.L.; Monroe-Devita, M.; Wasmuth, S.; Flanagan, M.E.; Morse, G.A.; Leiter, M.; Salyers, M.P. Organizational Conditions That Influence Work Engagement and Burnout: A Qualitative Study of Mental Health Workers. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2021, 44, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institut Català de la Salut Gerència Territorial Catalunya Central Memòria 2018; Barcelona, 2018;

- López-Rodríguez, J.A. Declaración de La Iniciativa CHERRIES: Adaptación al Castellano de Directrices Para La Comunicación de Resultados de Cuestionarios y Encuestas Online. Aten Primaria 2019, 51, 586–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Salas, S.; Rodríguez-Domínguez, C.; Arcos-Romero, A.I.; Allande-Cussó, R.; García-Iglesias, J.J.; Gómez-Salgado, J. Psychometric Properties of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9) in a Sample of Active Health Care Professionals in Spain. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2022, 15, 3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribà-Agüir, V.; Más Pons, R.; Flores Reus, E. Validación Del Job Content Questionnaire En Personal de Enfermería Hospitalario. Gac Sanit 2001, 15, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salessi, S.; Omar, A. Satisfacción Laboral Genérica. Propiedades Psicométricas de Una Escala Para Medirla. Alternativas en psicología 2016, 93–108.

- Forné, C.; Yuguero, O. Factor Structure of the Maslach Burnout Inventory Human Services Survey in Spanish Urgency Healthcare Personnel: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Med Educ 2022, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Martínez, M.; Fernández-Cano, M.I.; Feijoo-Cid, M.; Llorens Serrano, C.; Navarro, A. Health Outcomes and Psychosocial Risk Exposures among Healthcare Workers during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Outbreak. Saf Sci 2022, 145, 105499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno Martinez, M.; Feijoo-Cid, M.; Fernandez-Cano, M.I.; Llorens-Serrano, C.; Navarro-Gine, A. Psychosocial Risk in Healthcare Workers after One Year of COVID-19. Occup Med (Chic Ill) 2024, 74, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Atanes, M.; Pijoán-Zubizarreta, J.I.; González-Briceño, J.P.; Leonés-Gil, E.M.; Recio-Barbero, M.; González-Pinto, A.; Segarra, R.; Sáenz-Herrero, M. Gender-Based Analysis of the Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Healthcare Workers in Spain. Front Psychiatry 2021, 12, 692215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, A. La Teoría de Las Demandas y Recursos Laborales: Nuevos Desarrollos En La Última Década. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 2023, 39, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de seguridad y Salud en el trabajo (INSST); O.A.; M.P Encuesta Europea de Condiciones de Trabajo 2021. Datos de España; Madrid, 2023.

- Dall’Ora, C.; Ball, J.; Recio-Saucedo, A.; Griffiths, P. Characteristics of Shift Work and Their Impact on Employee Performance and Wellbeing: A Literature Review. Int J Nurs Stud 2016, 57, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranjić, N.; Mosorović, N.; Bećirović, S.; Sarajlić-Spahić, S. Association between Shift Work and Extended Working Hours with Burnout and Presenteeism among Health Care Workers from Family Medicine Centres. Med Glas 2023, 20, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall’ora, C.; Ejebu, O.Z.; Ball, J.; Griffiths, P. Shift Work Characteristics and Burnout among Nurses: Cross-Sectional Survey. Occup Med (Lond) 2023, 73, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salas-Nicás, S.; Moncada, S.; Llorens, C.; Navarro, A. Working Conditions and Health in Spain during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Minding the Gap. Saf Sci 2021, 134, 105064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsahoryi, N.A.; Alathamneh, A.; Mahmoud, I.; Hammad, F. Association of Salary and Intention to Stay with the Job Satisfaction of the Dietitians in Jordan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Health Policy Open 2021, 3, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Doshi, M.D.; Schold, J.D.; Preczewski, L.; Klein, C.; Akalin, E.; Leca, N.; Nicoll, K.; Pesavento, T.; Dadhania, D.M.; et al. Survey of Salary and Job Satisfaction of Transplant Nephrologists in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2022, 17, 1372–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Trabajo e Inmigración Encuesta de Calidad de Vida En El Trabajo; Madrid, 2010;

- Snow Andrade, M.; Westover, J.H.; Peterson, J. Job Satisfaction and Gender. Journal of Business Diversity 2019, 19, 22–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, L.; Chen, X.; Peng, S.; Zheng, F.; Tan, X.; Duan, R. Job Burnout and Turnover Intention among Chinese Primary Healthcare Staff: The Mediating Effect of Satisfaction. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, Y.M.; Nielsen, M.B.; Kristensen, P.; Bast-Pettersen, R. Shift Work, Mental Distress and Job Satisfaction among Palestinian Nurses. Occup Med (Lond) 2017, 67, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball, J.; Day, T.; Murrells, T.; Dall’Ora, C.; Rafferty, A.M.; Griffiths, P.; Maben, J. Cross-Sectional Examination of the Association between Shift Length and Hospital Nurses Job Satisfaction and Nurse Reported Quality Measures. BMC Nurs 2017, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Guerra, B.; Guiance-Gómez, L.M.; Méndez-Pérez, C.; Pérez-Aguilera, A.F. Impacto de Los Turnos de Trabajo En La Calidad Del Sueño Del Personal de Enfermería En Dos Hospitales de Tercer Nivel de Canarias. Med Segur Trab (Madr) 2022, 68, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.P.; Chang, Y.P. Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Sleep Quality of Female Shift-Working Nurses: Using Shift Type as Moderator Variable. Ind Health 2019, 57, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, R.R.; Fitzpatrick, J.J.; Boyle, S.M. Closing the RN Engagement Gap: Which Drivers of Engagement Matter? J Nurs Adm 2011, 41, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, L.; Li, L. Work Engagement and Associated Factors among Healthcare Professionals in the Post-Pandemic Era: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front Public Health 2023, 11, 1173117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Li, Y.J.; Cheng, W.J. Gender- and Age-Specific Associations between Psychosocial Work Conditions and Perceived Work Sustainability in the General Working Population in Taiwan. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0293282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez Fernández, J.; Muñoz Leiva, F.; Montoro Ríos, F.J. ¿Cómo Mejorar La Tasa de Respuesta En Encuestas on Line? Revista de Estudios Empresariales. Segunda Época 2009, 45–62.

|

Medical professionals (n=126) |

Nursing professionals (n=195) |

p-value | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 30 (23.8) | 13 (6.7) | .000 |

| Female | 96 (76.2) | 182 (93.3) | |

| Age (x̄±SD) | 46±11 | 45±10 | .294 |

| Dependents in their charge | 57 (45.2) | 105 (53.8) | .132 |

| Academic level | |||

| Degree | 35 (27.8) | 72 (36.9) | .000 |

| University Master’s | 24 (19) | 114 (58.5) | |

| Specialist | 66 (52.4) | 8 (4.1) | |

| Doctorate | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Salary covering basic needs | 119 (94.5) | 134 (68.7) | .000 |

| Type of contract | |||

| Permanent | 84 (66.7) | 74 (37.9) | .000 |

| Temporary | 42 (33.3) | 121 (62.1) | |

| Rotating or irregular work shift | 55 (43.7) | 89 (45.6) | .726 |

| Position held in the company | |||

| Assistance | 113 (89.7) | 174 (89.2) | .898 |

| Direction, management | 13 (10.3) | 21 (10.8) | |

| Unpaid overtime work | 107 (84.9) | 129 (66.2) | .000 |

| Average weekly hours of unpaid overtime work (x̄±SD) | 5±6 | 3±5 | .000 |

| Years of service in the company (x̄±SD) | 16±11 | 13±10 | .072 |

| Work Engagement | Work Overload | Work Satisfaction | Emotional Exhaustion | |

| Unstandardized coefficient B (95% CI) | ||||

| Work Overload | .501 (.232, .770)*** | |||

| Work Satisfaction | .735 (.600, .869)*** | |||

| Emotional Exhaustion | -.246 (-.310, -.183)*** | |||

| Sex | -.367 (-2.140, 1.406) | .169 (-.656, .994) | 1.726 (.002, 3.450)* | -1.113 (-5.029, 2.803) |

| Age | .028 (-.063, .119) | -.020 (-.062, .023) | .035 (-.053, .124) | -.149 (-.351, .053) |

| Dependents in their charge | .319 (-.862, 1.499) | .211 (-.340, .761) | -.372 (-1.522, .778,) | 2.528 (-.085, 5.140) |

| Academic level | .546 (-.304, 1.397) | .159 (-.237, .554) | -.919 (-1.746, -.092)* | .616 (-1.262, 2.494) |

| Salary covering basic needs | -.576 (-1.246, .095) | -.342 (-.645, -.040)* | 1.541 (.909, 2.173)*** | -2.666 (-4.103, -1.230)*** |

| Occupational group | -.969 (-2.437, .498) | 1.428 (.765, 2.091)*** | .573 (-.813, 1.959) | 3.169 (.021, 6.318)* |

| Type of contract | -.583 (-2.194, 1.027) | .826 (.082, 1.570)* | -.500 (-2.055, 1.055) | 4.783 (1.251, 8.316)** |

| Rotating or irregular work shift | .698 (-.478, 1.873) | .554 (.013, 1.095,)* | -1.835 (-2.965, -.705)** | 3.374 (.806, 5.941)** |

| Position held in the company | .485 (-1.650, 2.621) | .630 (-.364, 1.625) | 1.158 (-.920, 3.237) | -1.270 (-5.992, 3.452) |

| Unpaid overtime work | .843 (-.656, 2.342) | 1.467 (.783, 2.150)*** | -.936 (-2.364, .493) | 3.269 (0.24, 6.514)* |

| Average weekly hours of unpaid overtime work | .061 (-.074, .196) | .007 (-.056, .071) | .015 (-.117, .147) | .078 (-.222, .379) |

| Years of service in the company | -.021 (-.118, .077) | -.036 (-.081, .010) | -.023 (-.118, .072) | .000 (-.216, .215) |

| Medical professionals | p-value | Nursing professionals | p-value | |||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |||

| Work engagement | 26.57 ± 9.35 | 26.16 ± 6.6 | .586 | 22.23 ± 9.58 | 27.32 ±7.40 | .039 |

| Work overload | 17.50 ± 2.84 | 18.2 ± 2.25 | .317 | 16.85 ± 1.57 | 16.31 ±2.74 | .566 |

| Work Satisfaction | 32.83 ± 6.72 | 34.23 ± 5.02 | .420 | 30.77 ± 7.00 | 33.75 ± 5.19 | .131 |

| Emotional exhaustion | 35.90 ± 14.5 | 36.53 ± 11.37 | .911 | 37.15 ± 10.89 | 32.12 ± 12.09 | .111 |

| Male | p-value | Female | p-value | |||

| Medical professionals | Nursing professionals | Medical professionals | Nursing professionals | |||

| Work engagement | 26.57 ± 9.35 | 22.23 ± 9.58 | .159 | 26.16 ± 6.6 | 27.32 ±7.40 | .166 |

| Work overload | 17.50 ± 2.84 | 16.85 ± 1.57 | .222 | 18.2 ± 2.25 | 16.31 ±2.74 | .000 |

| Work Satisfaction | 32.83 ± 6.72 | 30.77 ± 7.00 | .440 | 34.23 ± 5.02 | 33.75 ± 5.19 | .725 |

| Emotional exhaustion | 35.90 ± 14.5 | 37.15 ± 10.89 | .969 | 36.53 ± 11.37 | 32.12 ± 12.09 | .006 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).