1. Introduction

The model of brain−gut axis

clearly explains the close relationship between the psychological well-being

and gut function and health. Several studies have shown the role of stress in

the pathogenesis of not only functional but also inflammatory bowel disorders

(Farhadi et al., 2005). Furthermore, presence of common psychological disturbances

such as depression and anxiety has long been seen as a key indicator of

psychological problems. However, other psychological conditions including

subjective well-being (SWB) could play a role in overall health and general

well-being, gastrointestinal health in particular (Farhadi et al., 2018). In

fact, SWB has been shown to influence the individual propensity for anxiety and

depression (Farhadi, 2018), as well as to affect physical health (Janson-Bjerklie et al., 1992; Kageyama et al., 2019; Olsson et al.,

2013). This broad influence of SWB has been shown to be

independent of traditional measures of anxiety and depression (Farhadi et al.,

2018). Consequently, in this manuscript, a new model of SWB that is easy to

understand and can thus be used to assess the overall SWB is proposed with the

aim of extending the application of this important psychological indicator

beyond field of positive psychology into the field of medicine.

This effort was motivated by the

fact that, despite well-established links between mind and body, developing

interventions that specifically target SWB is challenging, as this multifaceted

concept is difficult to measure. The issue stems from the lack of universal

definition of happiness, as well as the fact that what truly makes us happy

varies considerably based on personality traits, culture, religion, place of

living, social norms, and individual belief system. As a subjective feeling

that is abstract in nature, happiness can be conceived as a wide range of

positive emotional feelings, as well as contentment with one’s life situation

and satisfaction with status quo, which are collectively denoted as

subjective well-being. Still, there is presently no unified method for

measuring SWB and overall level of contentment with life (Diener, 2000; Hervas

& Vazquez, 2013; Linton et

al., 2016; Ryan & Deci,

2001; Ryff, 1989; Topp et al., 2015). As a result, in extant studies, a variety

of questionnaires have been used to gather the data based on which the most

relevant factors that contribute to the sense of well-being would be

potentially identified. Accordingly, the survey respondents are asked to rate

their life satisfaction, success and sense of financial security, as well as

respond to questions that would determine their personal and psychological

traits such as optimism, confidence, and trust. The obtained findings are used

to complement the assessment of overall well-being at the population level

(Helliwell et al., 2012; Koivumaa-Honkanen et al., 2005; Lyubomirsky, S.,

Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D., 2005); Zautra & Hempel, 1984) or to design behavioral and cognitive interventions aimed at

improving individuals’ overall well-being (Hogan et al., 2016; Keyes & Annas, 2009).

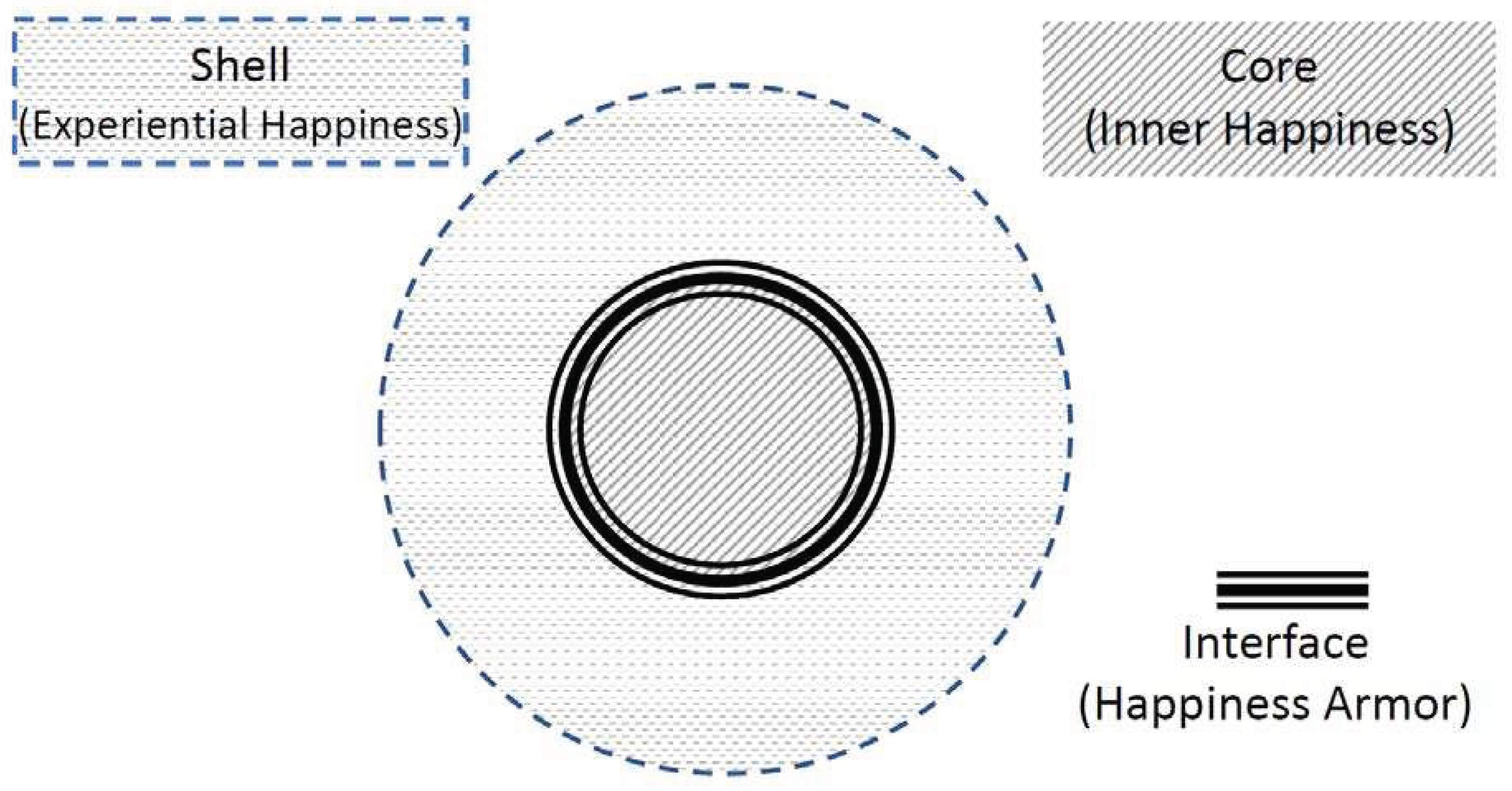

The S&C model of SWB was developed to bridge this gap in extant research. It is a

modular model that serves as framework and placeholder for various forms of

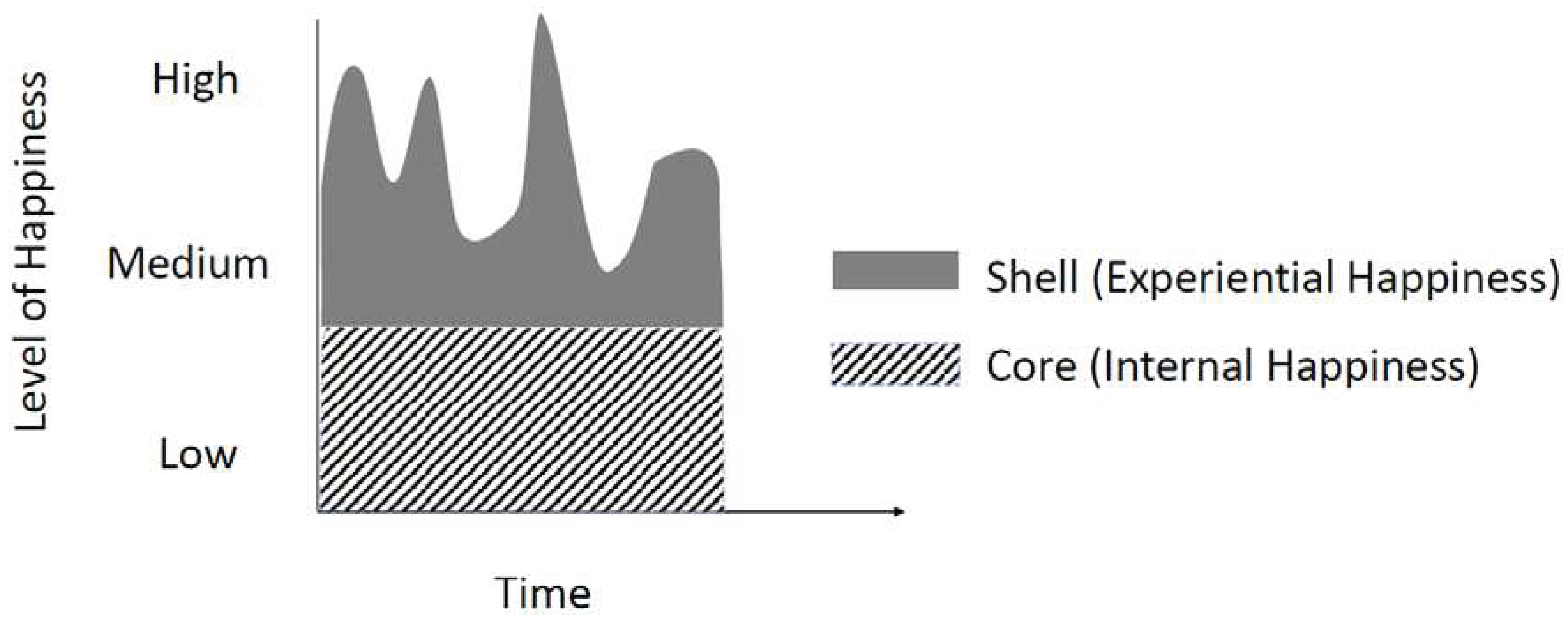

positive emotions and SWB comprising three main components. The shell of

happiness represents experiential happiness, i.e., a positive feeling as a

result of one’s experience with the surrounding environment. The core of

happiness represents inner happiness. The third component is a interface layer

between the shell and core of happiness that consists of a set of coping and

defense mechanisms that protect the core of happiness and is thus denoted as

happiness suit of armor (HSOA). By positioning the

factors that determine SWB within these three layers, the goal is to lay the

groundwork for understanding the reach of happiness beyond traditional

psychology condition of anxiety and depression and amend that beyond field of

positive psychology to clinical medical ailments.

3. Results

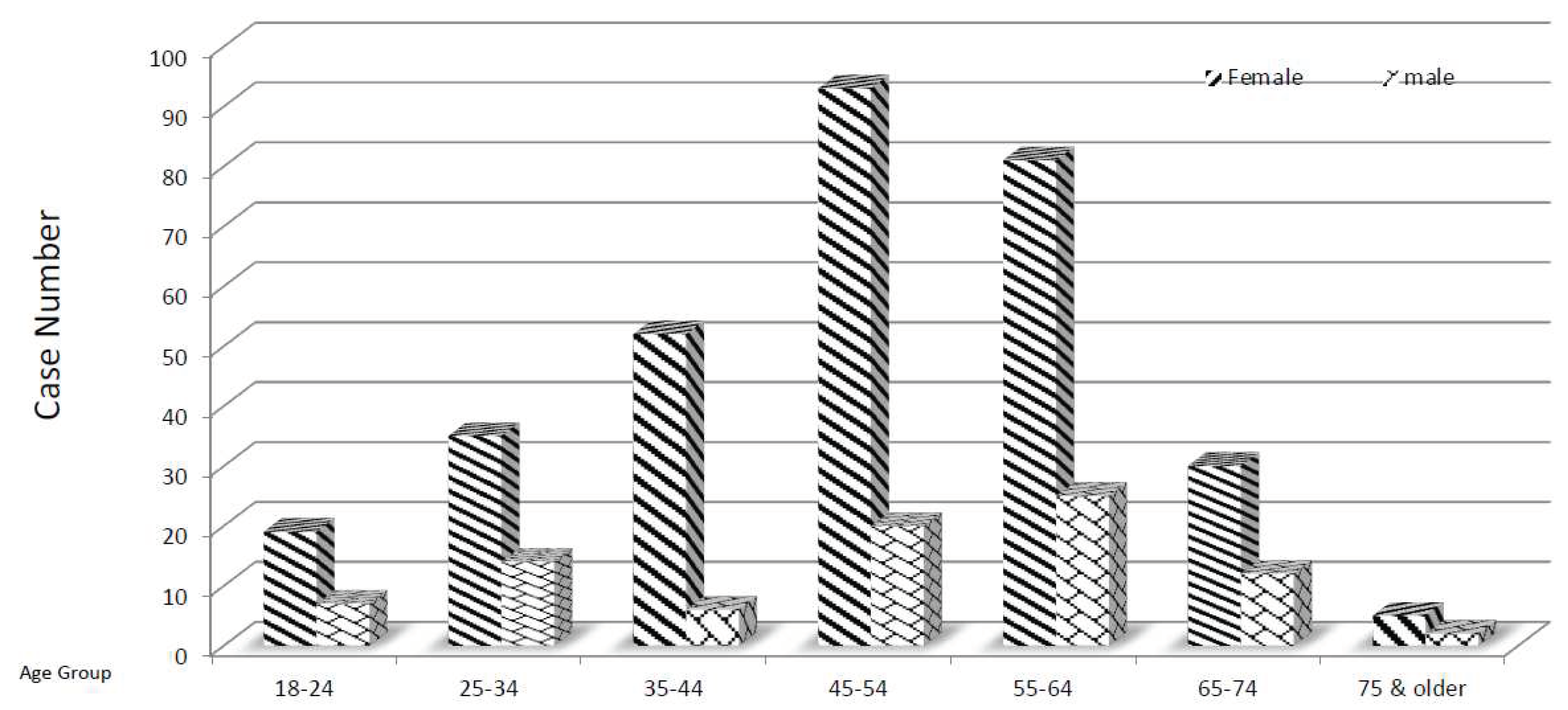

The age and gender distribution of the study sample are shown in

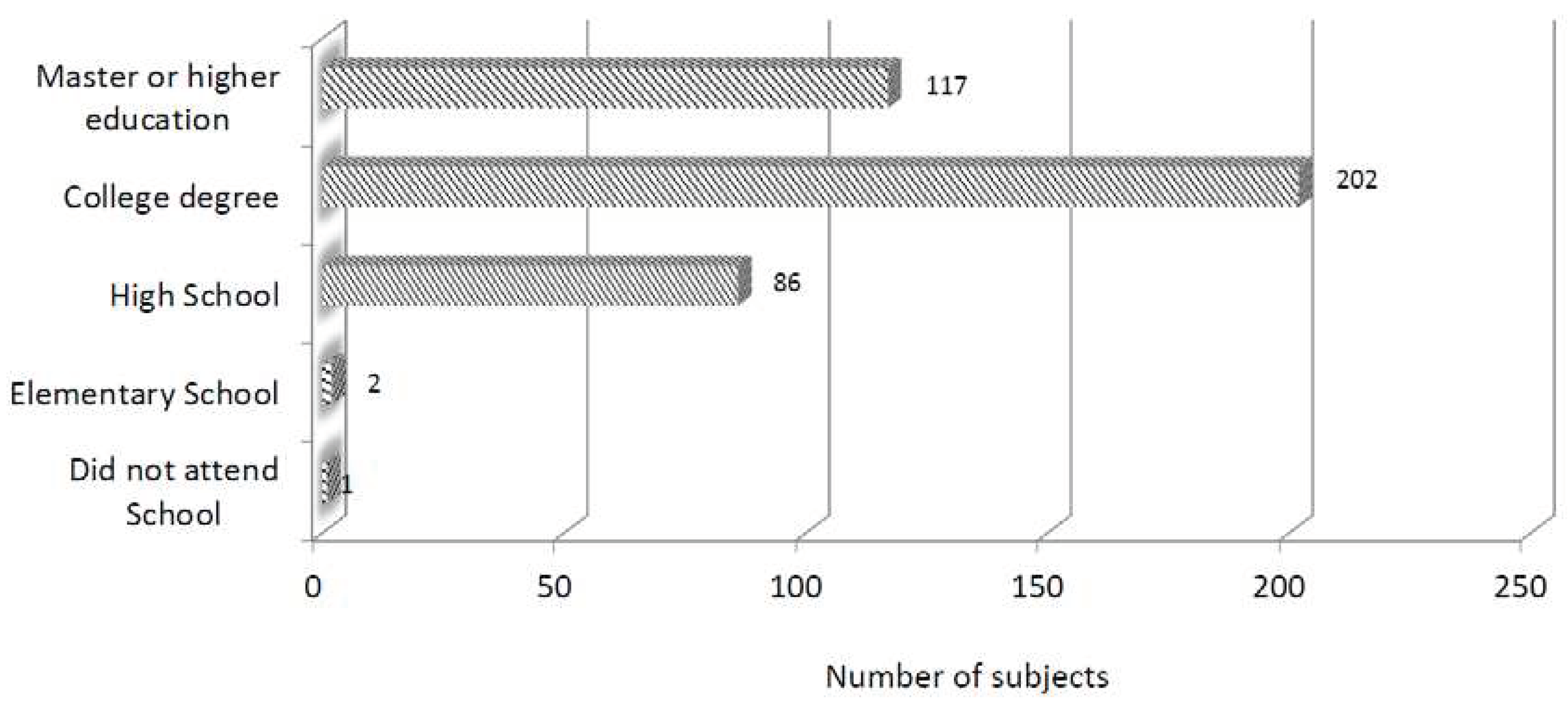

Figure 1. Further analyses of the demographic data revealed that 53% of the participants are married, while 18% are divorced, and 22% never married. Moreover, most of the respondents are educated to the college degree level (

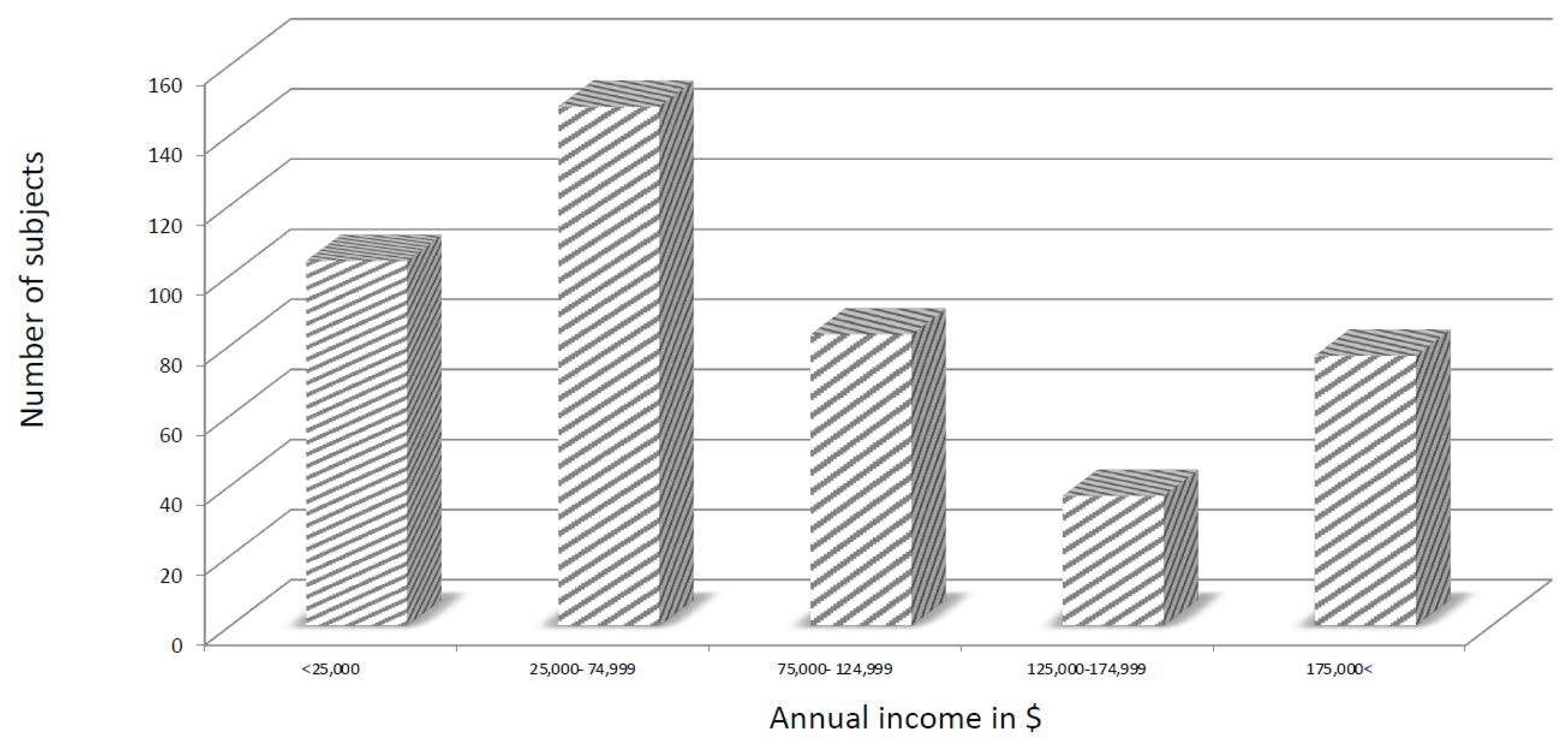

Figure 2) or above and have annual household income in the

$25,000−75,000 range (

Figure 3). In terms of ethnicity, at 68%, white Americans predominated, followed by Asian Americans (15%), Latinos (11%), and African Americans (2%), while the remaining 4% comprised of other races or preferred not to disclose.

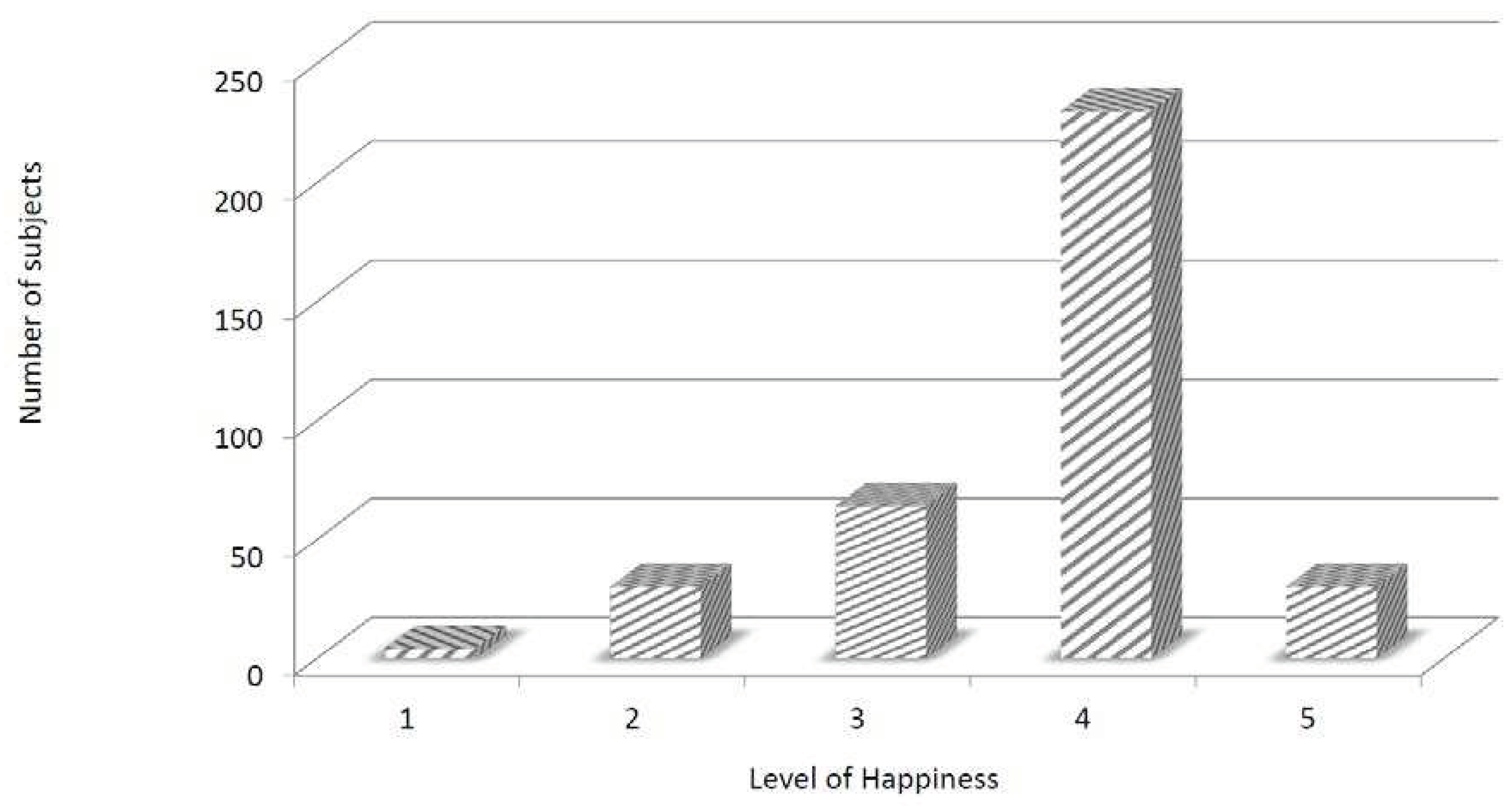

The analyses of survey responses related to the overall happiness indicate that 73% of the sample are generally happy or very happy all the time, while 18% of the participants are neither happy, nor unhappy, and 9% are unhappy or very unhappy (

Figure 4). Yet, as shown in

Table 1, the overall SWB was not dependent on gender or household income, while all but one of the well-being attributes correlate with SWB based on the non-parametric test results (Spearman correlation). Therefore, linear models were developed to identify a subset of well-being attributes that could be used effectively as a proxy for the SWB. The findings indicated that optimism, living in peace, feeling respected, a sense of being successful, and feeling loved were most closely associated with SWB, with an overall accuracy of 68%. However, only a few of these variables retained their significance when incorporated into a univariate model, as shown in

Table 1.

3.1. The Shell & Core Model of SWB – An Overview

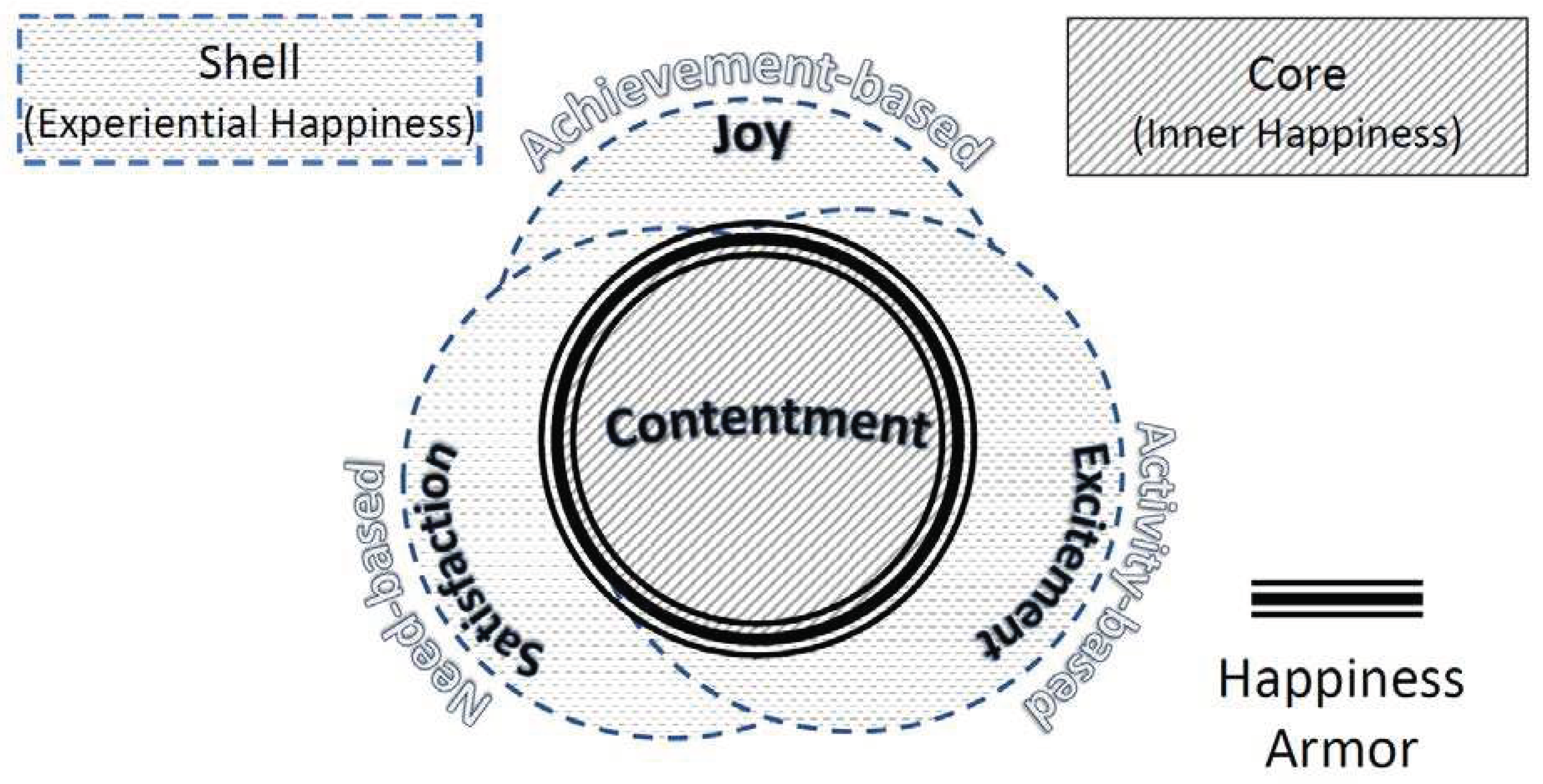

The S&C model of SWB is a comprehensive model based on a combination of eudaimonic and hedonistic perspectives. It considers a wide range of happy feelings affected by external circumstances in the shell of happiness (such as achievements, satisfaction of needs, and engagement in physical and mental activities) as well as core of happiness (supplying inner happiness), and an interface layer linking the shell and core of happiness (named HSOA) involving psychological characteristics pertaining to coping and defense mechanisms (

Figure 5). Such a modular framework allows any possible future expansion or adjustment to the model to ensure that it remains responsive to the changing social reality. Moreover, as the model variables are based on current data obtained from this preliminary research and can be modified and rearranged based on more complementary larger studies and be applied in a variety of clinical settings.

In its development, SWB was conceptualized as a multitude of subjective experiences that can only be expressed through words. Therefore, it was assumed that, based on the theory of linguistic relativity, one’s worldview and overall perception of one’s external environment is influenced by the structure of their primary language. This issue is further compounded by the fact that happiness is difficult to describe precisely, as it is often equated with joy, pleasure, exhilaration, bliss, contentedness, delight, felicity, enjoyment, and satisfaction, even though each of these sensations is a distinct phenomenon. Thus, to avoid any ambiguity, in the S&C model, specific words were assigned to different contexts that may give rise to happy feelings. Even though this assignment could be considered arbitrary, it was necessary for defining different forms of happy feeling related to various physical, mental, social, and spiritual experiences. Moreover, providing a common terminology makes the discussion of various real-life applications of SWB much easier. Therefore, the S&C model not only provides a framework for defining various forms of happy feelings, it also provides insight into the interactions among these factors that give rise to SWB.

3.2. The Shell (Experiential Happiness)

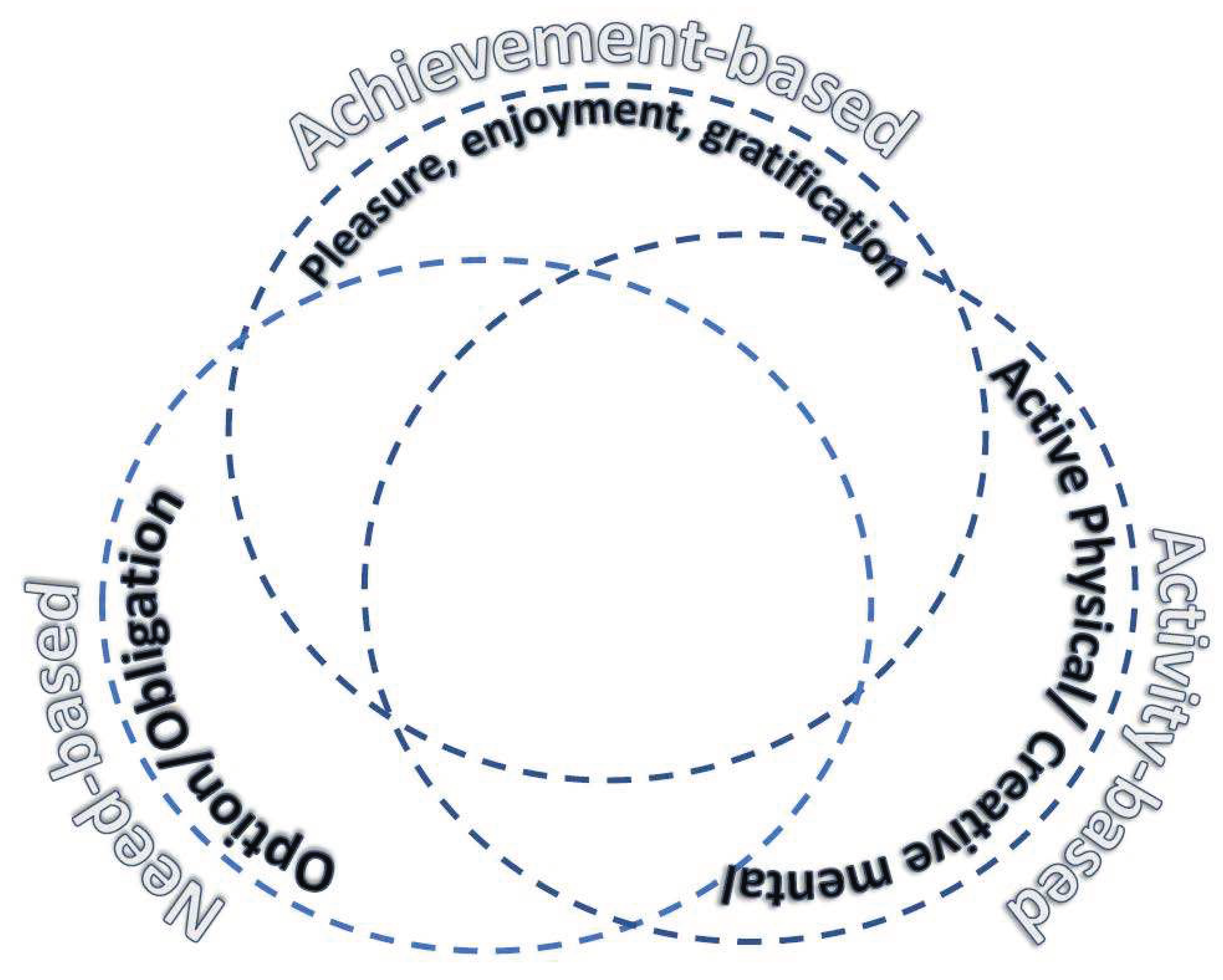

In the S&C model, any form of happy feeling that is a result of experiences with the surrounding world is considered to be situated within the shell of happiness. These experiences are categorized under three main domains, namely achievement-based happiness (

joy), need-based happiness (

satisfaction), and activity-based happiness (

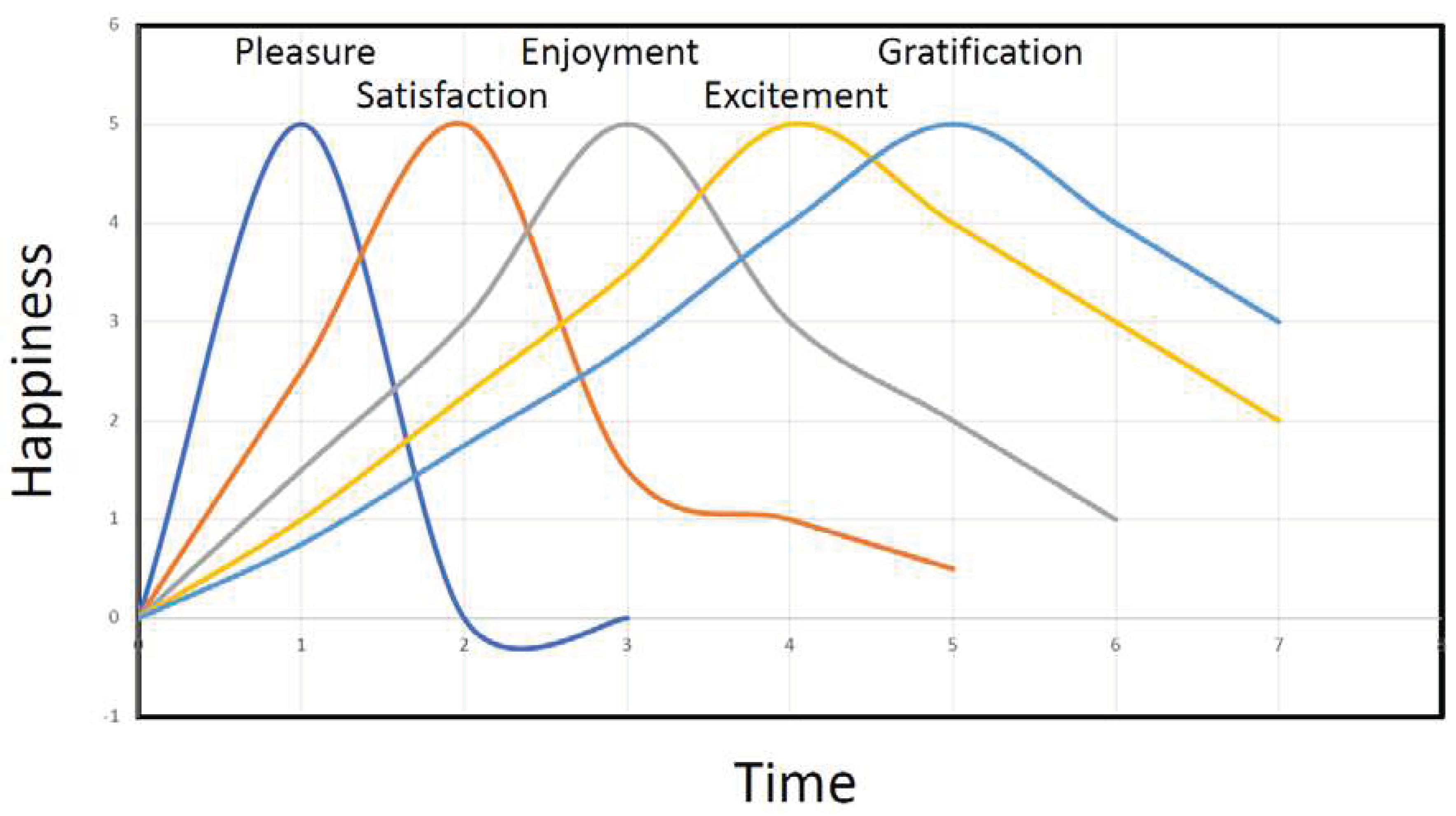

excitement). All forms of experiential happiness are time bound and result in generation of

happy moments. However, the durability of each happy feeling is highly variable depending on the type of experience (

Figure 6).

3.3. The Structure of the Shell

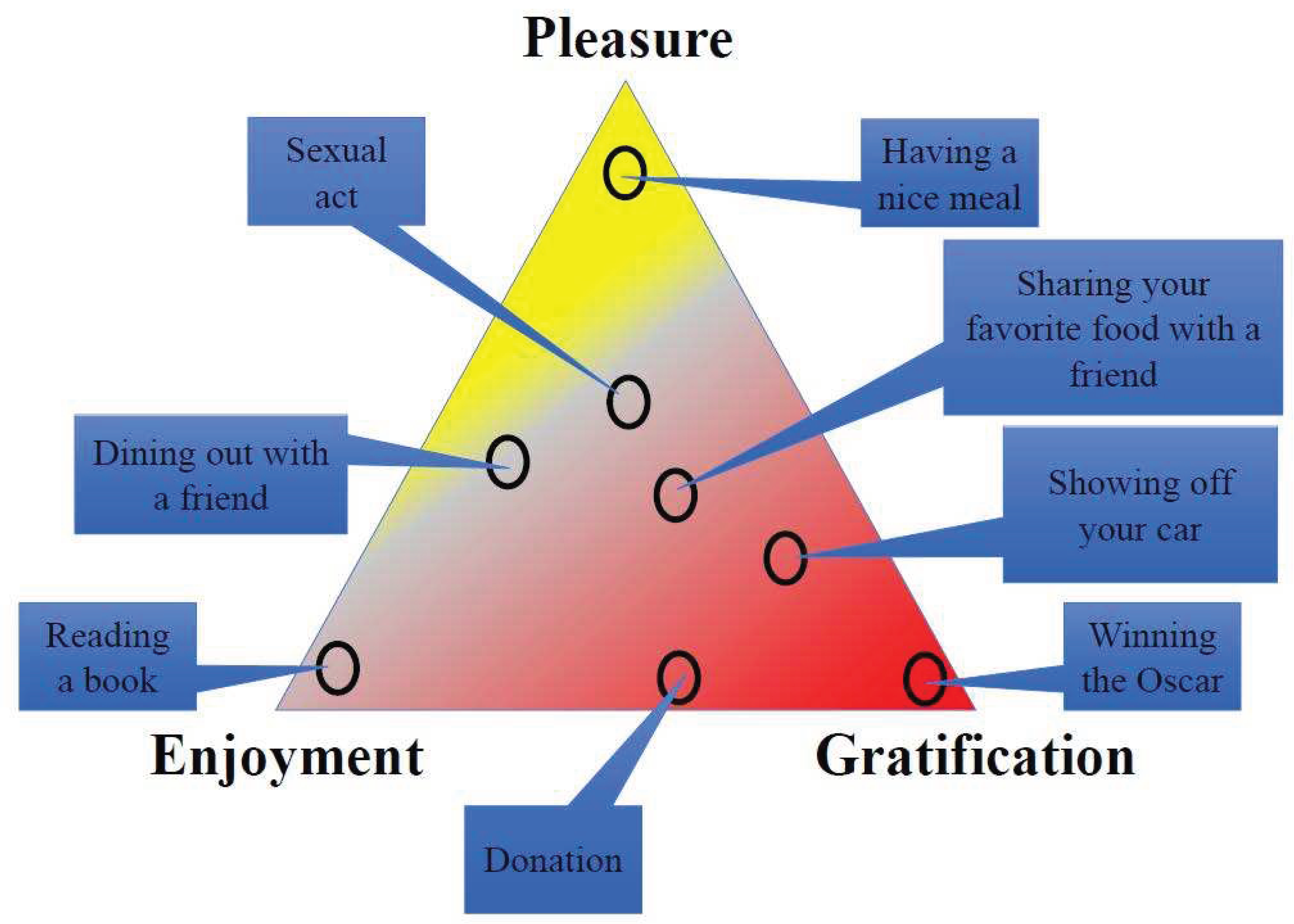

Joy (Achievement-Based Happiness). Achievement-based happiness is the happy feeling associated with “having what one wants when one wants it,” whether it is a simple experience such as a bite of delicious food or a profound life-altering achievement. This form of happy feeling is further subdivided into three main subcategories of pleasure, enjoyment, and gratification.

Pleasure. Pleasure is the most well-known and common type of joy as it arises Pleasure is one of the earliest forms of happy feeling that is inseparable from human being. The happy feeling of pleasure is the result of simple sensory experiences such as taste, smell, vision, hearing, touch, or a complex combination of these sensory inputs, such as eating a meal or a sexual act. Pleasure is the most primitive form of happy feeling and human as well as animal brains are hardwired to receive pleasure since birth. As a result, the desire to repeat the pleasurable activities may lead to habit formation or even addiction.

Enjoyment. Enjoyment is a form of joy that can be experienced only after acquiring intellectual and interpersonal skills and by partaking in social interactions. As it places greater demand on one’s cognition, enjoyment engages thinking and learning, as well as communication skills. Hanging out with a friend, reading a book or a poem, watching a movie, and having a pleasant conversation are all examples of enjoyment. Enjoyment provides a deeper and more meaningful sense of happy feeling in comparison with pleasure which only entails simple engagement of our senses. The happy feeling associated with enjoyment is more durable than pleasure since it strikes the chord harder with one’s true self. Moreover, it does not require external input, as positive emotions can be experienced through meditation. In particular, mindful meditation, which requires an individual to refrain from any physical or mental activities, and to eliminate all social and environmental inputs, gives rise to thought-less moments that can be experienced as pure happiness. This practice is not only one of the best methods to diffuse stress by allowing the mind to reboot itself but also provides the opportunity for the practicing individual to be present in the moment. Even though the happy feeling associated with enjoyment is more amenable to reasoning, people can make a habit of enjoyable activities or fall prey to addiction.

Gratification. Gratification is a form of joy that stems from the approval and appreciation of others, which can range from a simple verbal compliment for a good deed to a widespread recognition for receiving a lifetime achievement or award. This form of experiential happiness is typically sought by those with more extensive social interactions and greater intellectual capabilities who derive their happiness from that of others. These individuals typically engage in activities that benefit their community, work on building a better world, or strive to make a meaningful difference in the life of others. As gratification is the highest level of joy, the happy feeling associated with this form of achievement-based happiness is the most durable. The impact of experiencing a meaningful gratification is usually life-changing due to which this experience is far more memorable than other forms of experiential happiness.

While this simple subdivision is rooted in empirical evidence, it is not easy to categorize most of the real-life experiences into one of the aforementioned achievement-based types. For example, the experience of going out for dinner with a friend could result in a mixture of pleasure derived from eating a good food, enjoyment of socializing with a friend, and gratification arising from the friend’s appreciation. Indeed, as shown in

Figure 7, most of the daily routine activities can give rise to a mixture of different forms of achievement-based happiness.

Satisfaction (Need-Based Happiness). Satisfaction as a form of happy feeling in response to one’s needs is the other form of experiential happiness that starts at birth. The need-based happiness peaks when the need is met. We experience such satisfaction on a daily basis as the pleasant feeling of satiety after a period of hunger or the sense of relief after going to the bathroom after a long travel. In the S&C model, however, satisfaction also extends to the positive emotions associated with fulfilling an obligation.

Excitement (Activity-Based Happiness). Excitement is yet another form of experiential happiness that is associated with activities, desired physical or mental activities in particular. An extreme form of excitement arises when the individual is fully committed and involved in a creative activity that matches their skills and knowledge, giving rise to the concept of “state of flow” (Csikszentmihalyi, 2013). Many believe that state of flow is the ultimate form of happiness, which can be attained with or without having a set goal. For example, activities such as playing an instrument, playing a game, or doing exercise could all have positive effects on the individual and result in a happy feeling. When engaging in these activities provides thought-less moments away from the surrounding distractions, they can also provide a means for diffusing stress.

3.4. The Core (Inner Happiness)

Contentment. The core of happiness in the S&C model of SWB is the source of inner happiness, i.e., it is not the result of a direct contact and experiences with the surrounding world and does not necessitate achievement, activity, or fulfillment of a need. Accordingly, as shown in

Figure 8, it is denoted as “contentment.” Therefore, the core of happiness serves as the foundation for the shell of happiness, providing a base for the accumulation of happy moments. Therefore, one’s happiness could be considered as a sum of inner happiness provided by the core and experiential happiness offered by the shell (

Figure 9). As several factors influence the inner happiness such as genetics/heredity, upbringing, culture, religion, education, and past experiences, it is also denoted as an endogenous happiness (

Dfarhud et al., 2014).

3.5. The Interface between the Core and the Shell of Happiness

Happiness Suit of Armor (HSOA)

The interface between the shell and core of happiness acts as a layer of coping and defense mechanisms that mitigates the untoward effects of life’s challenges on one’s core of happiness. This interface is composed of a set of psychological traits and is metaphorically called happiness suit of armor (HSOA) as its goal is protecting and maintaining the inner happiness. The HSOA analogy also explains why the integrity of any system in general depends on the strength of its components, given that an armor is only as strong as its weakest piece [Achilles’ heel]. The ten major pieces of HSOA include:

Helmet as a symbol of knowledge & optimism

Chest as a symbol of love

Abdomen as a symbol of management

Back as a symbol of health and fitness

Right hand as a symbol of trust & flexibility

Left hand as a symbol of support for others

Right foot as a symbol of freedom

Left foot as a symbol of peace

Shield as a symbol of confidence

Sword as a symbol of justice & forgiveness

While all HSOA elements are beneficial, their relative importance will vary depending on the individual’s set of values, culture, and beliefs. In addition, some individuals naturally have more strengths toward some of the listed traits and may choose to address the traits that may benefit from fortification.

3.6. The Characteristics of the Shell and Core of Happiness

Experiential Happiness Subtypes Overlapping Each Other. As shown in

Figure 10, a happy feeling that could be categorized as achievement-based happiness could also be interpreted as the activity-based or need-based form of happiness.

Experiential Happiness is Timestamped. Being time-bound is another common feature of various forms of experiential happiness, as the happy feelings typically start around or even before the event, peak during the experience, and gradually diminish over time (

Figure 6). This temporary nature of experiential happiness allows us to create happy moments (Nawijn, 2011).

Experiential Happiness Effect Decreases Over Time. The happy feeling associated with any form of experiential happiness diminishes with repeated experiences as a result of habituation.

Experiential Happiness is Habit Forming. Most forms of experiential happiness (such as pleasure, enjoyment, gratification, or excitement) can lead to habit formation, as preserving the happy momentum or striving to repeatedly induce the same happy feeling is a natural response to positive experiences and a habit can turn into an obsession and/or addiction. In fact, addiction is a result of transforming an achievement- or activity-based happiness into a need-based happiness. This may explain why these activities turn into need and obligation and can take priority over any other forms of joy or excitement (Farhadi, 2019).

Experiential Happiness can be Bought. Money can buy various forms of experiential happiness and provide abundance of happy moments. Money can fulfill the basic needs and thus bring satisfaction, Money can also boost achievement-based happiness, as it can be utilized to provide pleasure, support enjoyment, or even gratification. Money can also be used to induce the state of flow, as it can free one from the everyday mundane routine and allow time to be spent partaking in fully immersive and motivating activities.

Given the above, it is not surprising that following money is seen as synonymous with following the American dream. Yet, in practice, the link between one’s overall happiness and household income is not substantiated by the available evidence (Farhadi et al., 2018; David et al., 2000). Based on the S&C model of SWB, money can contribute positively to the shell of happiness, but it does not influence the overall happiness since it can neither boost internal happiness nor buy contentment.

The Inner Happiness is Stable. In contrast to the experiential happiness, the core of happiness is relatively stable over time. Nonetheless, fluctuations can occur in the inner happiness as a result of interactions with the shell and the HSOA, as explained below.

The Shell and the Core of Happiness are Interconnected. Even though, the shell and the core of happiness are represented as distinct entities in the S&C model of SWB, they interact both directly and through the HSOA. For example, encounters with the external world can influence one’s family dynamics, social environment, and financial status, as well as several aspects of HSOA, thus impacting the inner happiness. Likewise, the core of happiness can influence how an individual interacts with the environment and responds to everyday experiences, thereby causing changes to their shell of happiness.

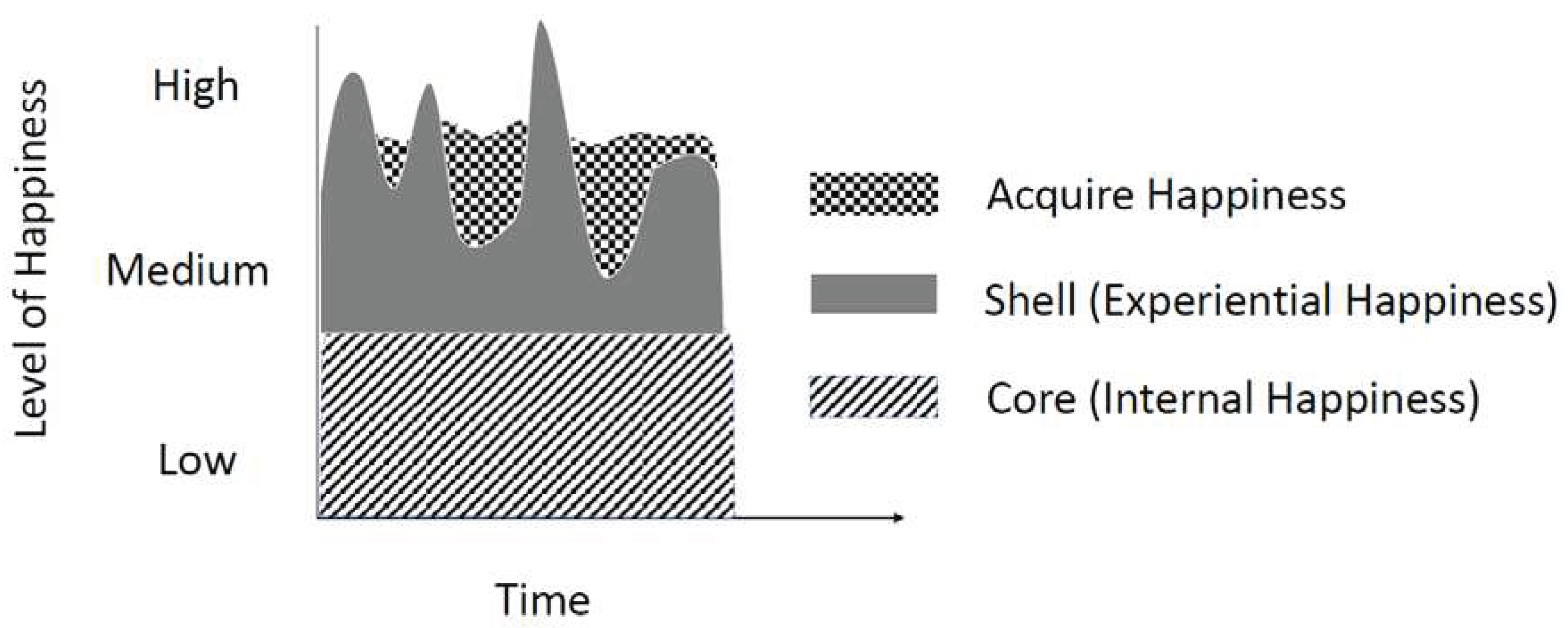

The Core of Happiness Modifies the Shell. One clear example of the modification of the shell of happiness by the core is “acquired happiness” which stands in contrast to achievement-based happiness. As noted previously, achievement-based happiness is the result of getting what one wants when one wants it. However, this is rarely possible in practice, due to which acquired happiness (also known as synthetic, simulated, or virtual happiness) is what most individuals actually experience (Gilbert, 2006). Unlike natural or true happiness, acquired happiness is a coping mechanism akin to acquired taste, which means “Something that a person dislikes at first, but that starts to like after a while.”[i] Thus, in the S&C model of SWB, acquired happiness is defined as a positive feeling associated with wanting what one has, after one has attained it.

At first glance, acquired happiness may seem to be nothing but a result of flexibility or adaptation to an undesired situation. However, the fundamental distinction between these concepts is that, unlike flexibility and adaptation, where the individual tolerates an unwanted situation while still is fully aware of flaws and weaknesses of the situation, with acquired happiness allows an individual to appreciate the positive aspects of the situation so that even the flaws can be seen as strengths. A further difference stems from the fact that, despite flexibility and adaptation, an individual remains willing to terminate the unfavorable situation if the opportunity arises. Conversely, with maturation of acquired happiness, individual becomes truly happy with the way things are and will not be looking to change the situation. At this stage, the acquired happiness is indistinguishable from achievement-based happiness. Acquired happiness could therefore fill the void of experiential happiness by compensating for life’s imperfections and shortcomings (

Figure 11). This may explain why the most affluent nations are not the happiest ones, and why the level of happiness is not significantly different among individuals despite great differences in their achievements such as the level of education, extent of success, and/or income (Helliwell et al., 2012).

The Shell of Happiness Modifies the Core. As one progresses through life, one’s perspectives changes as a result of one’s experiences. However, the same approach can be adopted to modify negative worldviews or attitudes, as is done as a part of behavioral and cognitive therapy. In the S&C model of SWB, this interaction is represented as an impact of positive experiences on the personality traits comprising the HSOA or even the inner happiness, allowing an individual to cope better with negative experiences. For example, temporary achievement-based happiness such as taking a vacation can have much longer effect on the overall happiness beyond the happy moments it offers (Nawijn, 2011).

The Cumulative Properties of Positive Affect. Ample body of evidence shows that positive affect has a cumulative beneficial influence on the general SWB and success in life (Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). Collective effect of positive emotions is also the basis for broaden-and-build theory of happiness (Fredrickson, 2004). Accordingly, the S&C model of SWB postulates that the core of happiness can be expanded with frequent positive reinforcement of the shell of happiness, helping the individual weather the life experiences associated with negative affect. The model further predicts that the effect of frequently adopting positive attitude also has the capacity to strengthen the HSOA and its buffering action to mitigate the negative effect of negative life experiences.

3.7. The S&C Model of SWB in Comparison with Other Models

Many believe that happiness is the ultimate goal is life (Diener, 2000), even though a recent study did not support this notion (Farhadi et al., 2017). Nonetheless, as happiness is very important to most individuals, numerous attempts have been made to create a unifying model for defining and understanding happiness. These models incorporate a variety of internal and external factors that have been shown to play role in one’s positive emotions and happiness. Among the internal factors, inherited personality attributes, upbringing and childhood experiences, as well as the effect of experiences later in life on the person’s characteristics, are widely recognized as the main drivers of SWB. Some authors go as far as to claim that almost half of an individual’s happiness can be attributed to their genetic background (Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D., 2005). Among the external factors, activities, social engagement, relationships, mindfulness, as well as some personality characteristics such as optimism, are typically cited as modifiers of overall happiness and SWB (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Diener & Seligman, 2002; Green et al., 2006; Seligman et al., 2005; Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2006). These findings suggest that many aspects of happiness/SWB can be modified using cognitive and behavioral interventions (Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D., 2005; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). Accordingly, the S&C model incorporates several factors affecting SWB, and its application could augment our understanding of various aspects of happiness and their interactions. This model could also be used as the basis for psychological interventions to enhance the overall SWB in healthy individuals as well as those suffering from various medical conditions.

To compare S&C model with several currently utilized models of SWB a brief overview of historic and current models of SWB are presented to highlight their similarities and dissimilarities.

3.8. The Historic Foundation of Happiness

The idea of happiness as a reflection of fate and good luck is nearly as old as humanity, and this link is reflected in the origin of the word “happiness” in English, as its stem hap- means happening and good luck. The first documented non-religious, simple but fundamental framework of happiness may be attributed to the father of Western philosophy, Socrates (470 BC). Based on his interpretation, happiness could be attained only if one followed a set of principles such as Courage, Moderation, Justice, and Wisdom that were universally-accepted virtues regardless of culture, religion, or time. In fact, Socrates’ fundamental interpretation of happiness is the framework of happiness in major religions, and in particular the Catholic tradition of Cardinal Virtues. This understanding of happiness was in a sharp contrast with a view of that predominated in the Roman Empire which was based on the pursuit of pleasure. While this hedonistic tradition is not a typical model in a scientific sense, it posits that happiness is a result of increasing pleasure and decreasing pain. This attitude could be considered as the basis for Western lifestyle where the immediate pleasure of life achievement and avoidance of negative affect is seen as a measure of one’s life satisfaction (Argyle et al., 1999).

Eudaimonic tradition, credited to Aristotle, is an alternative to these worldviews, as it defines happiness as having a good life. According to Aristotle, although virtues and their exercise are important in achieving happiness, it cannot be attained without health, wealth, and beauty.

Still, owing to the strong influence of religion, throughout the history, the interpretation of happiness in most societies has evolved around religious beliefs. In particular, in most traditional major religions, submission is promoted as a means of attaining greater happiness, which explains why, in general, religious people tend to be happier (Popova & Otrachshenko, 2015). While the association between happiness and practicing religious rituals such as attending the church has been observed in some studies (Ferriss, 2002) but not in others (Lewis et al., 2000), the sense that one can entrust their destiny to a benevolent higher being tends to bring benefits to religious individuals irrespective of their faith. Accordingly, prayers that are inseparable part of religious practice promote hope, trust, peace, and loyalty.

Even though Buddhism is not considered a true religion, it builds its philosophical worldview on the foundation of happiness. In particular, it is based on the notion of nirvana—a state of everlasting peace and happiness—which can be attained by overcoming all forms of craving. This perspective is in direct contrast to the Greek hedonic and eudaimonic traditions according to which happiness is achieved through worldly experiences and activities. In Buddhism, focusing inward through meditation is the primary means for achieving a happy state, as confirmed by the findings of several recent studies (Shultz & Ryan, 2015).

The S&C model of SWB aligns well with the postulates of both eudaimonic and hedonistic tradition, as it promotes the idea of striving for virtues (the core of happiness) and pursuing worldly pleasures (the shell of happiness) as the path to happiness. The S&C model of SWB also shares many aspects of happiness with Buddhism, such as the separation of experiential happiness and inner happiness. However, in the S&C model, different forms of experiential happiness are recognized, rather than being subsumed under the umbrella of need-based happiness as is the case in Buddhism. Moreover, whereas Buddhism mainly focuses on peace as the mainstay of inner happiness, in the S&C model, peace is only one of the pieces of the HSOA that protect the overall contentment.

3.9. Happiness in the 20th Century

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

According to Maslow’s theory of human motivation, we are driven by five basic categories of needs (Maslow, 1943) with different levels of importance, whereby physiological needs must be satisfied first before we become concerned with our safety, sense of love and belonging, and esteem, culminating in self-actualization. According to this hierarchy of needs, when the needs at the lower level of the pyramid are met, the needs at the next level become the focus of attention, resulting in a constant pursuit of need fulfillment which leads to personal improvement. While it is argued that very few can achieve self-actualization, once they reach their full potential, they are expected to feel true happiness due to having a clear sense of right and wrong (Inglehart et al., 2008).

When examined alongside the Maslow’s model, it is evident that the S&C model of SWB features many of its aspects. In particular, several needs in Maslow’s model overlap with achievement-based happiness while the need for love, safety, and esteem corresponds to several components of the HSOA. Likewise, some aspects of self-actualization resonate with the state of flow characterizing activity-based happiness. However, some disparities are also apparent, as Maslow’s model purports that one must ascend the pyramid across all levels without omitting any of the five stages. This view is widely criticized, as it also implies that individuals at certain levels of hierarchy cannot regress to the lower tiers, while in practice it is conceivable that sudden changes in one’s circumstances would induce such a decline. Moreover, even those rare individuals that manage to achieve self-actualization will likely develop a new set of needs from lover levels, pulling them down from pyramid’s apex.

A further distinction arises from the focus on needs in Maslow’s model, even though humans have other motivations, described by Farhadi (2019) as a blend of obligations and options explained by the “duality of reason.” This practical perspective is embedded in the S&C model of SWB as various aspects of shell of happiness, to reflect the fact that accomplishing a task could result in a mixed feeling of joy and satisfaction.

3.10. From Happiness to Well-being

In the mid-20th century, academic focus shifted from personal and subjective feeling of happiness toward more objective measures of happy feeling and happy living, ironically giving rise to the term subjective well-being (SWB). According to this new perspective, SWB, rather than some abstract notion of happiness, is the main objective in life, and can be attained by acquiring a combination of cognitive and behavioral attributes such as infrequent negative affect, frequent positive affect, and various aspects of physical life satisfaction such as health, relationships, and work (Argyle et al., 1999; Diener, 1984, 1994, 2000; Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D., 2005; Pressman & Cohen, 2005). These views are reflected in numerous scales and measures of happiness and SWB that are in use today. Most of these instruments are devised not as a model of happiness but as a research tool that can be used to measure happiness in surveys or population-based studies. One of the pioneers of this interpretation, Thomas, subdivided happiness into three main domains of pleasure corresponding to hedonistic happiness, satisfaction as the depiction of life welfare, and well-being as the interpretation of overall life quality (Thomas, 1968). This framework was subsequently adopted to develop measures for assessing overall life satisfaction, such as the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) (Benditt, 1974; Diener et al., 1985; Shin & Johnson, 1978) and better life index (Adler & Seligman, 2016).

These and similar scales evaluate individuals’ perspective on a wide range of topics, including economy and prosperity (Diener, 2000). Accordingly, further development of these models allows further distinction of well-being as a result of relieving materialistic needs (satisfaction and convenience) versus psychological needs (contentment) (Diener et al., 2010). Therefore, it is not surprising that some scholars argue that SWB models are actually measuring the happiness that is aligned with eudaimonic perspective (Hone et al., 2014; Keyes, 2006; Ryff, 1989; Seligman, 2011) as well as hedonic perspectives (Huta & Ryan, 2010; Ryff & Boylan, 2016).

The initial framework developed by Thomas and its subsequent modifications align with various aspects of the S&C model of SWB. For example, pleasure and the materialistic aspects of well-being incorporated into SWLS resonate with the shell, while the psychological needs echo several aspects of the core of happiness in the S&C model.

3.11. Newer Models of Happiness

Positive Psychology

Positive psychology is often portrayed as a psychological study of positive mental attributes and strengths (Sheldon & King, 2001) or advancement in understanding of the psychology of happy feeling. However, some of its aspects can be traced to the perspective of happiness presented by Aristotle (Ryan & Deci, 2001) or Buddhist teachings (Lama & Cutler, 2008). It is believed that Maslow first coined the term “positive psychology” but most of the credit should be given to Martin Seligman who defined well-being as feeling good as a result of having purpose in life, meaningful relationships, and significant accomplishments (Seligman, 2004)

The problem with the definition of happiness adopted in positive psychology is the lack of objective measures of happiness, as most of the studies in this domain are based on self-assessment, which is prone to bias. In addition, as life satisfaction is an important factor in one’s sense of happiness (Achor, 2010; Argyle, 2001; David et al., 2013), in more recently developed models, happiness is conceived as a sum of positive emotions and life satisfaction (Pietro et al., 2014).

The broad nature of coverage of variables that are used in describing positive psychology, are key elements of the shell as well as the core of happiness in the S&C model of SWB. However, the comprehensive nature of the variables and clear classification of them in S&C model makes the understanding and approach to SWB easier and allow easier adoption of the model for general medical conditions.

3.12. The Hedonic and Eudaimonic Motives for Activities (HEMA)

The Hedonic and Eudaimonic Motives for Activities (HEMA) model purports that happiness can be attained through hedonic seeking of pleasure and relaxation and eudaimonic pursuit of meaning in life (Asano et al., 2020). Accordingly, the pursuit of happiness is the primary motive for one’s daily activities which could be either purely hedonistic or eudaimonic, or a mixture of the two (Bujacz et al., 2014). These HEMA principles were incorporated by Carrero et al. (2022) into a mathematical model reflecting the dynamics of these two motives, which is also closely related to “The Duality of Reason” model proposed by Farhadi (2019).

At first glance, several aspects of the HEMA model resonate with the S&C model of SWB. In particular, the hedonistic aspects of happiness could be equated to the shell of happiness, while the eudaimonic component could be considered similar to the core of happiness. However, many distinct features of the shell and core of happiness in the S&C model are generally absent from the HEMA framework.

3.13. Subjective Well-being (SWB) Homeostasis Model

This model is one of the few that put emphasis on a set of psychological traits as the defense and coping mechanisms as the dominant component of happiness that can offset the deleterious effect of undesired life experiences and outcomes (Cummins et al., 2002). It purports that a homeostasis of external factors countered with endogenous factors is needed to maintain happiness (Yeom & Yang, 2019)

The main similarity between the SWB Homeostasis Model and the S&C model lies in the HSOA that acts as a buffer system to mitigate any adverse life experiences on inner happiness. However, it only considers external factors a negative component in homeostasis and present the defense mechanism as internal factors that counter the external factor. While in the S&C model many factors of the shell of happiness are positive and inner happiness is distinct from the coping mechanisms that needs to be protected by the HSOA.

3.14. Broaden-and-build Theory

This model is also based on the premise that positive emotions can act as a buffer to dampen negative life experiences and outcomes (Fredrickson, 2004), which resonates with the HSOA in the S&C model of SWB.

3.15. State of Flow

State of flow provides a different perspective of happiness and SWB by defining an optimal experience that is achieved only when an individual is engaged in a meaningful and appropriately challenging activity, as this immersion results in inner peace and harmony, whereby the consciousness aligns with the goals and the psychic energy is focused on achieving those goals. While a person is in a state of flow, life has a meaning, and the quality of life is optimized (Csikszentmihalyi, 2013). In this state, the individual has clarity and knows exactly what is needed from one moment to the next. Many believe that state of flow is the ultimate form of happiness and, as successive goals can always be set, there would be always an opportunity to maintain the desired happiness level. Although the definition of meaningful activity varies across individuals and cultures, it is assumed that state of flow can be achieved in sports (Hills & Argyle, 1998), by taking part in leisure activities (Ateca-Amestoy et al., 2008; Spiers & Walker, 2009), by playing an instrument (Laukka, 2007), and generally by engaging in something that can result in full immersion in the task.

In the S&C model of SWB, the happiness as a result of physical or mental activities is an important part of the shell of happiness, which resonates with the aforementioned arguments. In fact, the deep happiness associated with activities can easily permeate from the shell of happiness into the core of happiness with positive impact on the HSOA properties.

3.16. Problems with Models of Happiness

Besides the elusive nature of the happy feeling, there are several factors that make understanding and measuring happiness challenging. First, most of the currently available measures of happiness and SWB rely on subjective conceptualizations and self-assessments, making it difficult to correlate more objective life circumstances such as financial status with one’s perception of well-being. As a result, researchers have long called for a life satisfaction model that comprises many heterogeneous factors impacting SWB (Diener, 1994).

The second issue stems from the wide span of factors that are involved in SWB, as each model or assessment tool tends to focus on a small set of factors influencing SWB. As a result, the findings reflect different aspects of SWB rather than one’s overall well-being. For example, some models focus on economic aspects (Juster & Stafford, 1985), while others examine level of activities (Csikszentmihalyi, 2013; Lemon et al., 1972), coping mechanisms (Brickman & Campbell, 1971; Michalos, 2014), life achievements/success (Emmons, 1986; Omodei & Wearing, 1990), or life events (Headey & Wearing, 1989).

The assessment of SWB is also rendered difficult by the temporary nature of the happy feeling, which would thus act as a confounder in any assessment. For this reason, when the Bradburn scale was initially introduced in 1969, the assessment inquired about happy feeling stemming from a particular experience within the span of four weeks (Bradburn, 1969). However, more recent evidence indicates that such a long interval between an inducement of happy feeling and data collection can affect the reliability and reproducibility of the gathered information (Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999)

3.17. Shortcomings of the S&C Model of SWB

The S&C model of SWB was proposed in this work as a framework that encompasses several aspects of happiness and presents them in a modular format, allowing any further revisions to be made. Even though this model covers a wide range of the attributes of well-being, it is possible that several other important factors or psychological traits been overlooked and could be added in the future through larger studies.

The study covered over 80questions in the survey related to the respondents’ well-being, coping mechanisms, and psychological characteristics. Fourteen precents of the survey questions remained unanswered and managed as missing data. it is acknowledged that this large number and the method adopted for handling missing data could have inadvertently affected the interpretation of results.

Due to the nature of an online survey, it usually attracts educated individuals that are adept at using modern technology. As a result, the findings reported here cannot be generalized beyond this specific group of individuals and would need to be verified through large-scale studies with much more diverse samples.

Another issue that is typical for psychological research relying on self-reported data is a response bias. Even though the questionnaire was completely anonymous, it is not uncommon for participants to give what they believe as socially acceptable answer rather than a truthful one. While this issue was mitigated by including different questions covering the same topic and the internal consistency of the responses was high, further studies with larger samples are still needed in order to validate the questionnaire used in this work.

It should also be noted that, as this study was exploratory in nature, the abundance of variables considered in model development could have resulted in an inflated type I error. However, based on the magnitude of the correlation among the factors, the chance of type I error is less than 0.001 in the majority of the variables.

Finally, since the S&C model of SWB is envisaged as a comprehensive model that encompasses many SWB components. While being comprehensive is one of the strength of the S&C model, it can also be seen as a drawback or impractical for those aiming to study a particular aspect of SWB. In such cases, already available models that only measure specific factors may be more useful (Boehm et al., 2011; Weytens et al., 2014).