Submitted:

08 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

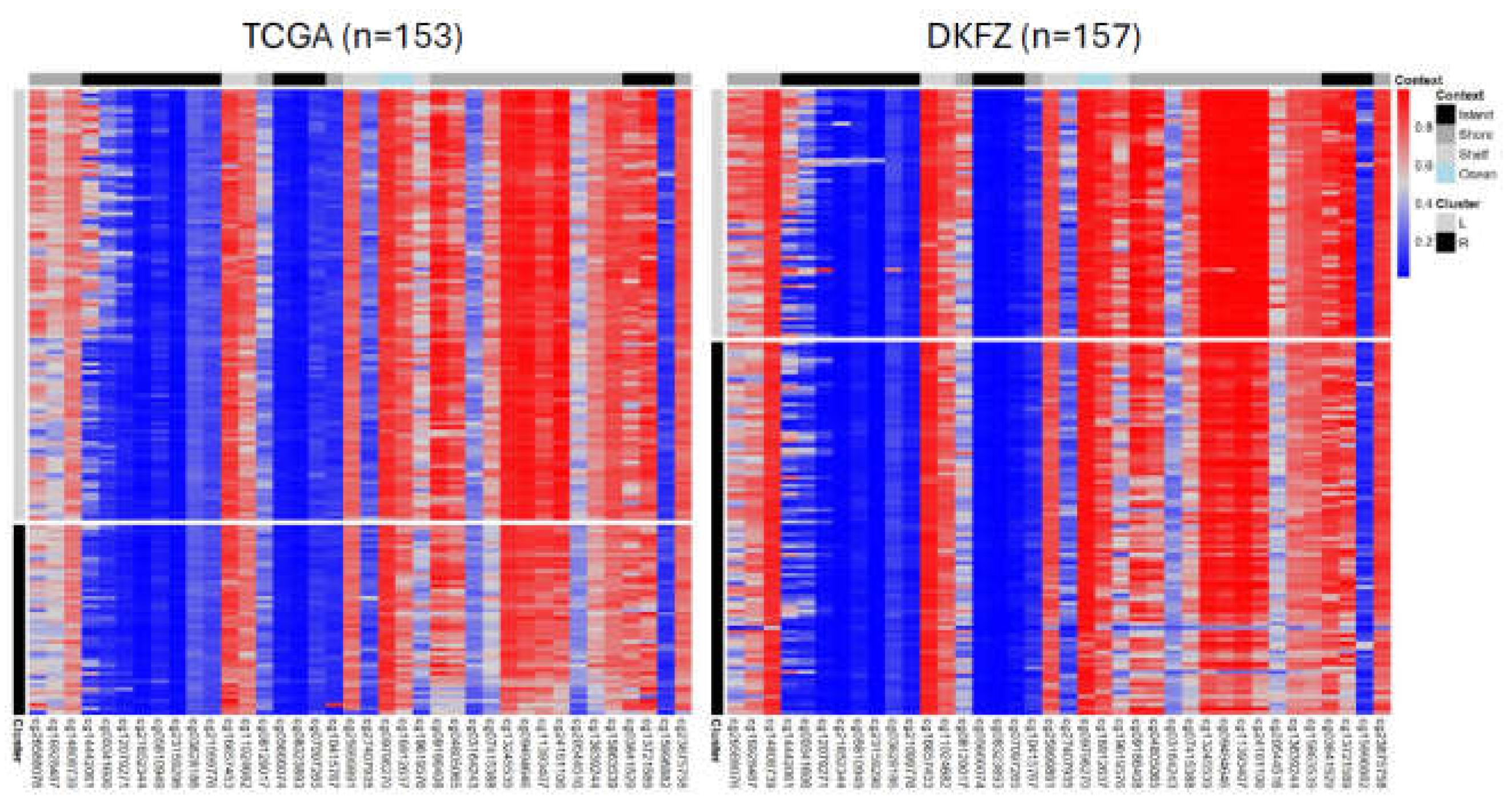

3.1. SREBF1 methylation stratifies GBM tumors

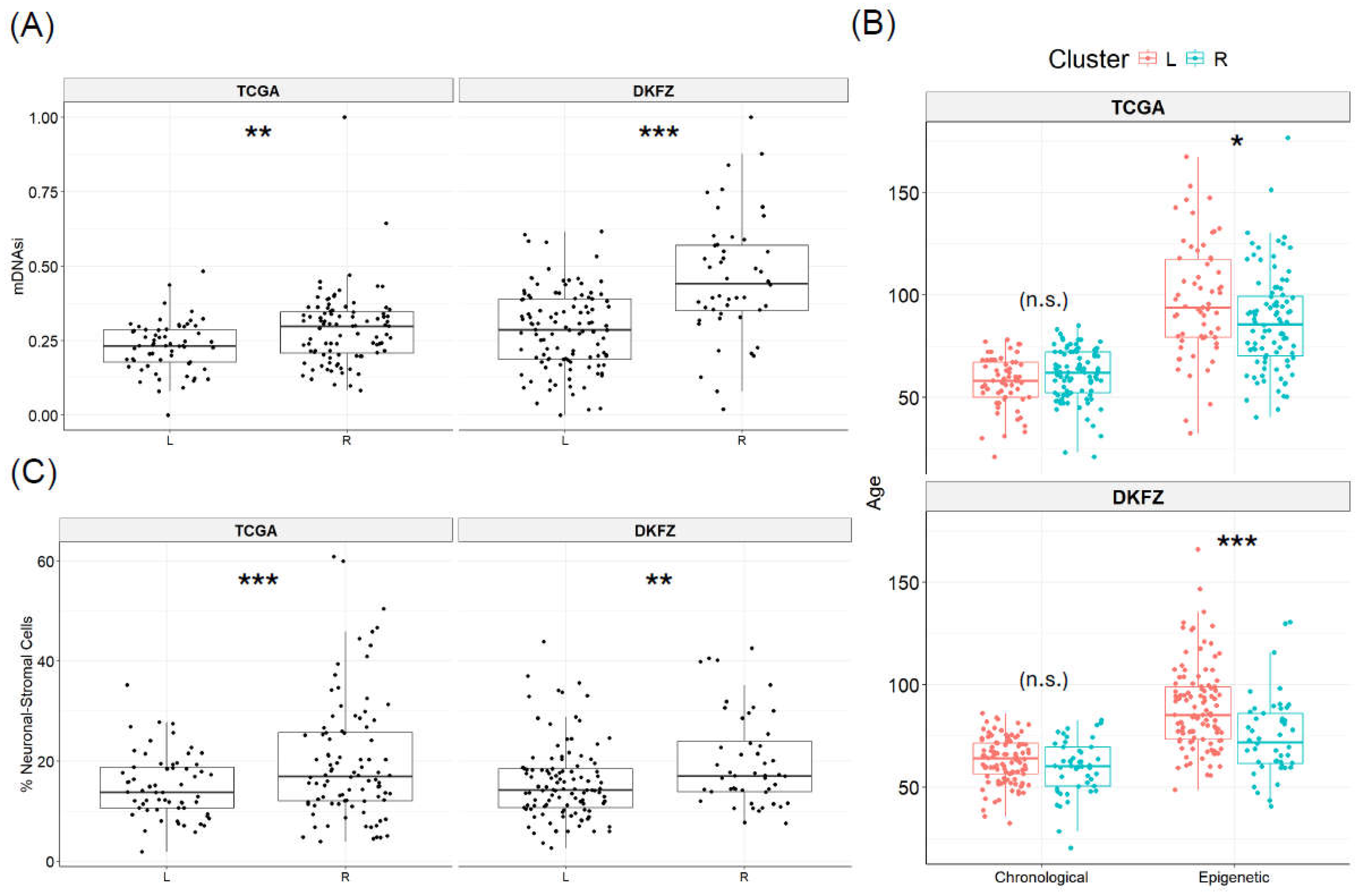

3.2. Cancer stemness delineates SREBF1 methylation clusters

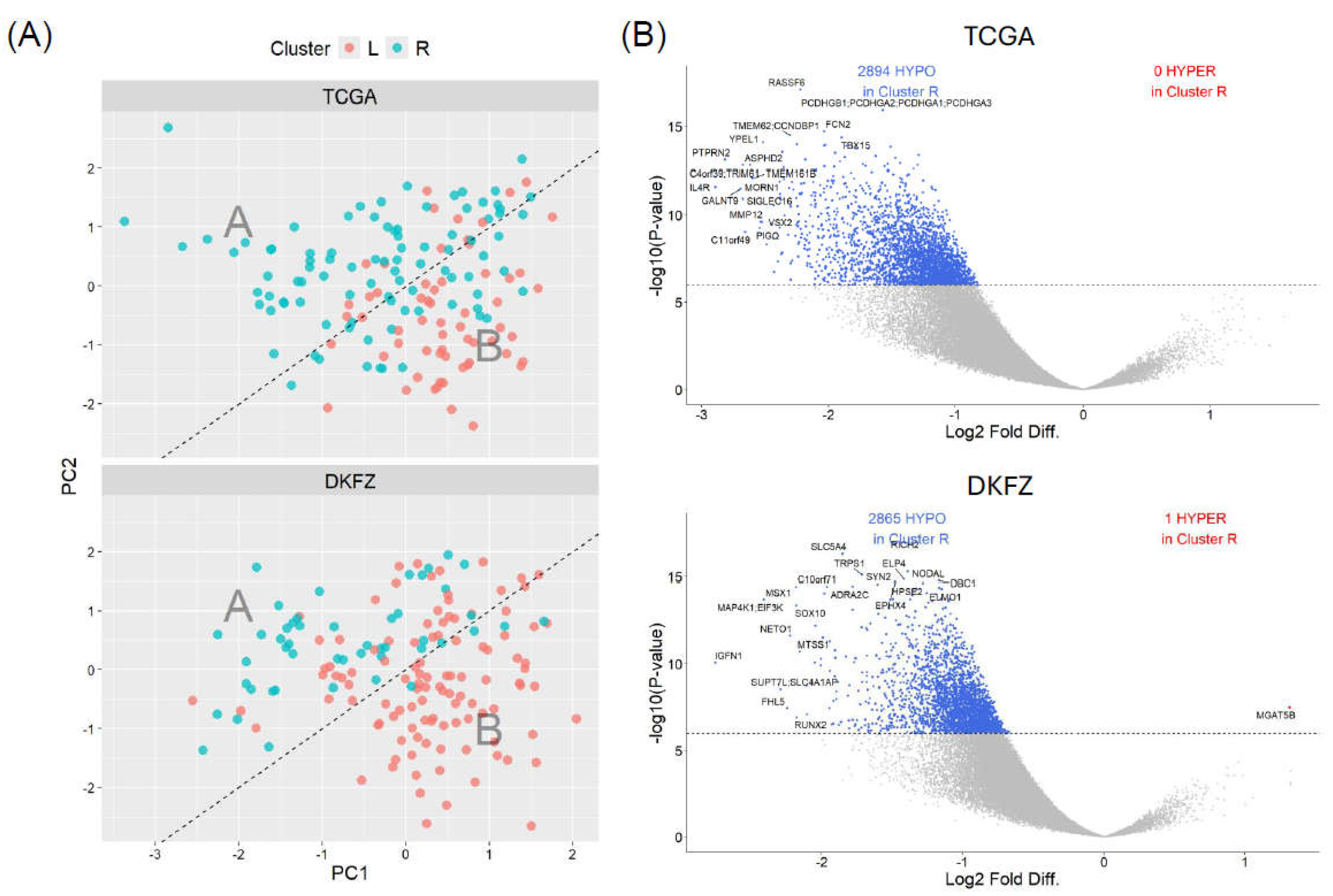

3.3. SREBF1 methylation clusters display distinct genome-wide epigenetic landscapes at the global-summary and single-nucleotide resolution

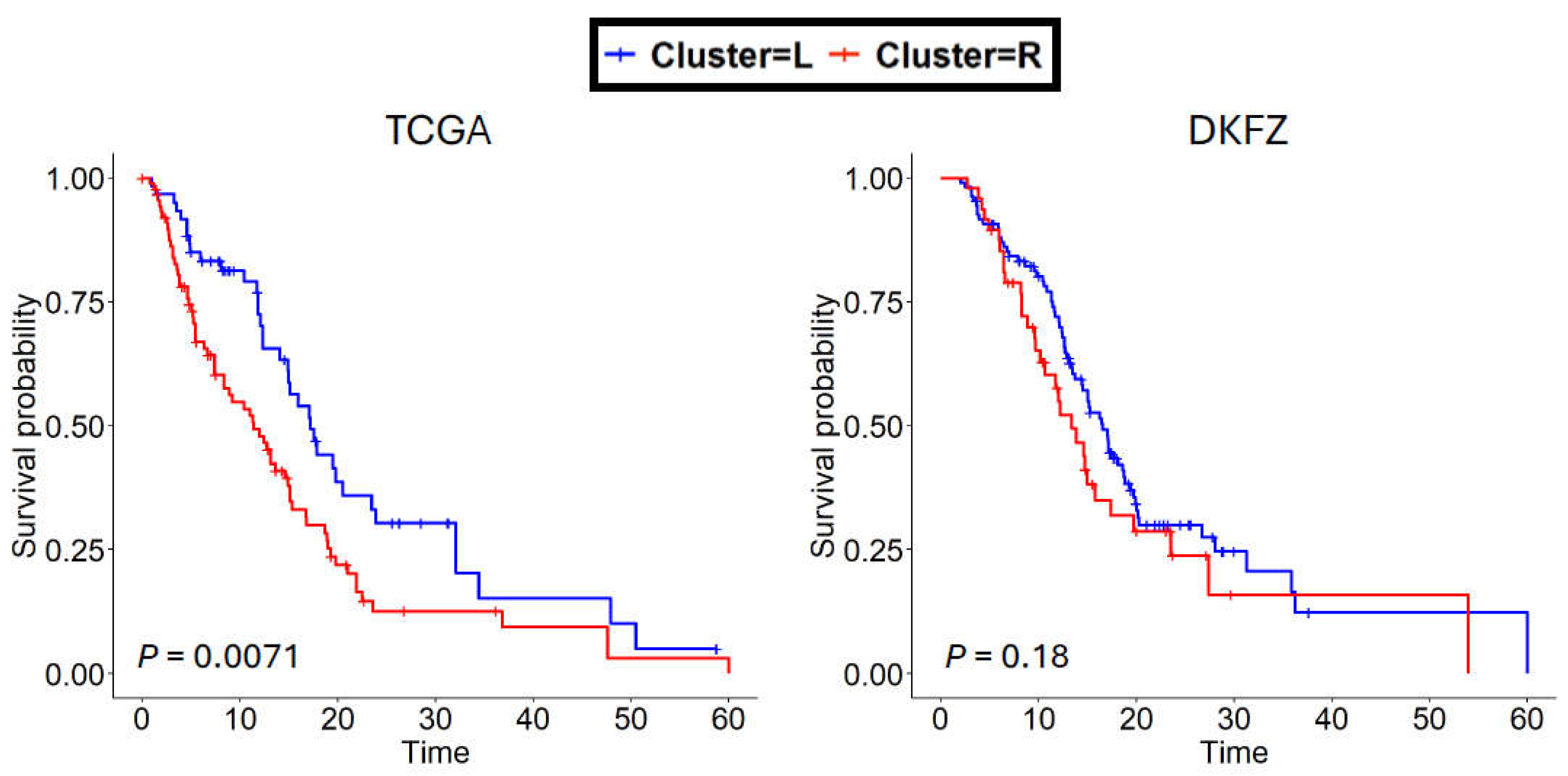

3.4. SREBF1 methylation may be a biomarker for patient survival

4. Discussion

5. Declarations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Miska, J.; Chandel, N.S. Targeting fatty acid metabolism in glioblastoma. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2023, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Y.; Geng, F.; Guo, D. Lipid Metabolism in Glioblastoma: from de novo Synthesis to Storage. Biomedicines. 2022, 10, 1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, C.W.; Verhaak, R.G.W.; McKenna, A.; et al. The Somatic Genomic Landscape of Glioblastoma. Cell. 2013, 155, 462–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lathia, J.D.; Mack, S.C.; Mulkearns-Hubert, E.E.; Valentim, C.L.L.; Rich, J.N. Cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 1203–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickingereder, P.; Neuberger, U.; Bonekamp, D.; et al. Radiomic subtyping improves disease stratification beyond key molecular, clinical, and standard imaging characteristics in patients with glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2018, 20, 848–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, S.; Gromovsky, A.D.; Hale, J.S.; et al. Altered lipid metabolism marks glioblastoma stem and non-stem cells in separate tumor niches. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2021, 9, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malta, T.M.; Sokolov, A.; Gentles, A.J.; et al. Machine Learning Identifies Stemness Features Associated with Oncogenic Dedifferentiation. Cell. 2018, 173, 338–354.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, M.J.; Jaffe, A.E.; Corrada-Bravo, H.; et al. Minfi: A flexible and comprehensive Bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics. 2014, 30, 1363–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pidsley, R.; YWong, C.C.; Volta, M.; Lunnon, K.; Mill, J.; Schalkwyk, L.C. A data-driven approach to preprocessing Illumina 450K methylation array data. BMC Genomics. 2013, 14, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suelves, M.; Carrió, E.; Núñez-Álvarez, Y.; Peinado, M.A. DNA methylation dynamics in cellular commitment and differentiation. Brief Funct Genomics. 2016, 15, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moody, L.; Hernández-Saavedra, D.; Kougias, D.G.; Chen, H.; Juraska, J.M.; Pan, Y.X. Tissue-specific changes in Srebf1 and Srebf2 expression and DNA methylation with perinatal phthalate exposure. Environ Epigenet. 2019, 5, dvz009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, C.; Sievert, H.; Geißler, C.; et al. Critical Evaluation of the DNA-Methylation Markers ABCG1 and SREBF1 for Type 2 Diabetes Stratification. Epigenomics. 2019, 11, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bady, P.; Sciuscio, D.; Diserens, A.C.; et al. MGMT methylation analysis of glioblastoma on the Infinium methylation BeadChip identifies two distinct CpG regions associated with gene silencing and outcome, yielding a prediction model for comparisons across datasets, tumor grades, and CIMP-status. Acta Neuropathol. 2012, 124, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, M.C.; Johnstone, A.; Eccles, D.; et al. An analysis of DNA methylation in human adipose tissue reveals differential modification of obesity genes before and after gastric bypass and weight loss. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houseman, E.A.; Accomando, W.P.; Koestler, D.C.; et al. DNA methylation arrays as surrogate measures of cell mixture distribution. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012, 13, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahsler, M.; Hornik, K.; Buchta, C. Getting Things in Order: An Introduction to the R Package seriation. J Stat Softw 2008, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Salas, L.A.; Marotti, J.D.; et al. Extensive epigenomic dysregulation is a hallmark of homologous recombination deficiency in triple-negative breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2025, 156, 1191–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Armstrong, D.A.; Salas, L.A.; et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling shows a distinct epigenetic signature associated with lung macrophages in cystic fibrosis. Clin Epigenetics. 2018, 10, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.A.; Chen, Y.; Dessaint, J.A.; et al. DNA Methylation Changes in Regional Lung Macrophages Are Associated with Metabolic Differences. Immunohorizons. 2019, 3, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Salas, L.A.; et al. Molecular and epigenetic profiles of BRCA1-like hormone-receptor-positive breast tumors identified with development and application of a copy-number-based classifier. Breast Cancer Res. 2019, 21, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Reproducible and Generalizable Framework for Multi-class Hierarchical Classification Demonstrated by DNA Methylation-based Glioma Subtyping. International Journal for Cross-Disciplinary Subjects in Education. 2024, 15, 4946–4950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 2013, 14, R115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Qian, J.; Ma, C. DNA Methylation-Based Cell Type Deconvolution Reveals the Distinct Cell Composition in Brain Tumor Microenvironment. arXiv (preprint), 22 January 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Transcriptomic profiling of subcutaneous adipose tissue in relation to bariatric surgery: a retrospective, pooled re-analysis. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2023, 32, 98–02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Pooled microarray expression analysis of failing left ventricles reveals extensive cellular-level dysregulation independent of age and sex. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology Plus. 2024, 7, 100060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gene Ontology Consortium. The Gene Ontology Resource: 20 years and still GOing strong. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D330–D338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Tanabe, M.; Sato, Y.; Morishima, K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D353–D361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizarraras, J.M.; Liao, Y.; Shi, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Pico, A.R.; Zhang, B. WebGestalt 2024: faster gene set analysis and new support for metabolomics and multi-omics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W415–W421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. A Cancer Proliferation Gene Signature Supervised by Ki-67 Strata Specific to Luminal A, Estrogen Receptor-Positive, and HER2-Negative Ductal Carcinomas. Med Res Arch 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Transcriptomic signature of CD4-expressing T-cell abundance developed in healthy peripheral blood predicts strong anti-retroviral therapeutic response in HIV-1: A retrospective and proof-of-concept study. INNOSC Theranostics and Pharmacological Sciences. 2024, 7, 2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. GGPLOT2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag; 2016.

- Liu, J.; Lichtenberg, T.; Hoadley, K.A.; et al. An Integrated TCGA Pan-Cancer Clinical Data Resource to Drive High-Quality Survival Outcome Analytics. Cell. 2018, 173, 400–416.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizgolshani, N.; Petersen, C.L.; Chen, Y.; et al. DNA 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in pediatric central nervous system tumors may impact tumor classification and is a positive prognostic marker. Clin Epigenetics. 2021, 13, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| SREBF1 Cluster | |||

| L | R | P-value | |

| TCGA | |||

| n (%) | 61 (39.87) | 92 (60.13) | - |

| Age (mean (s.d.)) | 57.07 (12.48) | 61.01 (12.76) | 0.062 |

| Sex (%) | |||

| Male | 41 (67.2) | 47 (52.2) | 0.096 |

| Female | 20 (32.8) | 43 (47.8) | |

| MGMT subtype (%) | |||

| Unmethylated | 34 (55.7) | 54 (58.7) | 0.85 |

| Methylated | 27 (44.3) | 38 (41.3) | |

| DKFZ | |||

| n (%) | 109 (69.43) | 48 (30.57) | - |

| Age (mean (s.d.)) | 63.06 (10.91) | 59.64 (13.35) | 0.094 |

| Sex (%) | |||

| Male | 64 (58.7) | 20 (41.7) | 0.072 |

| Female | 45 (41.3) | 28 (58.3) | |

| MGMT subtype (%) | |||

| Unmethylated | 50 (45.9) | 29 (60.4) | 0.13 |

| Methylated | 59 (54.1) | 19 (39.6) | |

| Term Identifier | Term Description | Total | Observed | Expected | Enrichment Ratio | Raw P | Bonferroni P |

| GO Biological Processes | |||||||

| GO:0010975 | Regulation of neuron projection development | 313 | 56 | 24.4 | 2.30 | 2.10E-09 | 1.76E-06 |

| GO:0007409 | Axonogenesis | 330 | 52 | 25.7 | 2.02 | 5.81E-07 | 4.88E-04 |

| GO:0031346 | Positive regulation of cell projection organization | 238 | 40 | 18.5 | 2.16 | 2.38E-06 | 2.00E-03 |

| GO:0031345 | Negative regulation of cell projection organization | 127 | 26 | 9.9 | 2.63 | 3.85E-06 | 3.23E-03 |

| GO:0050808 | Synapse organization | 332 | 49 | 25.8 | 1.90 | 8.28E-06 | 6.95E-03 |

| GO:0051960 | Regulation of nervous system development | 324 | 48 | 25.2 | 1.90 | 9.25E-06 | 7.76E-03 |

| GO:0016358 | Dendrite development | 162 | 29 | 12.6 | 2.30 | 1.73E-05 | 1.45E-02 |

| GO:0060560 | Developmental growth involved in morphogenesis | 180 | 31 | 14.0 | 2.21 | 1.99E-05 | 1.67E-02 |

| GO:0106027 | Neuron projection organization | 59 | 15 | 4.6 | 3.27 | 3.13E-05 | 2.63E-02 |

| GO Molecular Functions | |||||||

| GO:0060589 | Nucleoside-triphosphatase regulator activity | 282 | 46 | 22.7 | 2.03 | 2.39E-06 | 6.63E-04 |

| GO:0015631 | Tubulin binding | 215 | 36 | 17.3 | 2.08 | 1.70E-05 | 4.70E-03 |

| GO:0048156 | tau protein binding | 26 | 10 | 2.1 | 4.78 | 1.73E-05 | 4.78E-03 |

| GO Cellular Components | |||||||

| GO:0098984 | Neuron to neuron synapse | 238 | 40 | 20.2 | 1.98 | 1.69E-05 | 3.20E-03 |

| GO:0099572 | Postsynaptic specialization | 223 | 38 | 18.9 | 2.01 | 2.00E-05 | 3.79E-03 |

| GO:0098978 | Glutamatergic synapse | 280 | 44 | 23.8 | 1.85 | 3.60E-05 | 6.81E-03 |

| KEGG Pathways | |||||||

| hsa04919 | Thyroid hormone signaling pathway | 81 | 19 | 6.3 | 3.02 | 9.11E-06 | 3.14E-03 |

| hsa04360 | Axon guidance | 139 | 26 | 10.8 | 2.40 | 1.82E-05 | 6.28E-03 |

| hsa04725 | Cholinergic synapse | 87 | 18 | 6.8 | 2.66 | 9.40E-05 | 0.032 |

| HR | 95% CI, lower | 95% CI, upper | P-value | |

| TCGA | ||||

| Age in years | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.07 | ***4.76e-7 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Female | 0.53 | 0.33 | 0.83 | **5.98e-3 |

| MGMT subtype | ||||

| Unmethylated | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Methylated | 0.86 | 0.56 | 1.30 | 0.46 |

| Cluster | ||||

| L | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| R | 1.69 | 1.11 | 2.57 | *0.015 |

| DKFZ | ||||

| Age in years | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.05 | **1.86e-3 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Female | 1.13 | 0.76 | 1.67 | 0.54 |

| MGMT subtype | ||||

| Unmethylated | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Methylated | 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.72 | ***4.57e-4 |

| Cluster | ||||

| L | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| R | 1.25 | 0.81 | 1.92 | 0.31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).