Submitted:

04 September 2025

Posted:

05 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experiment

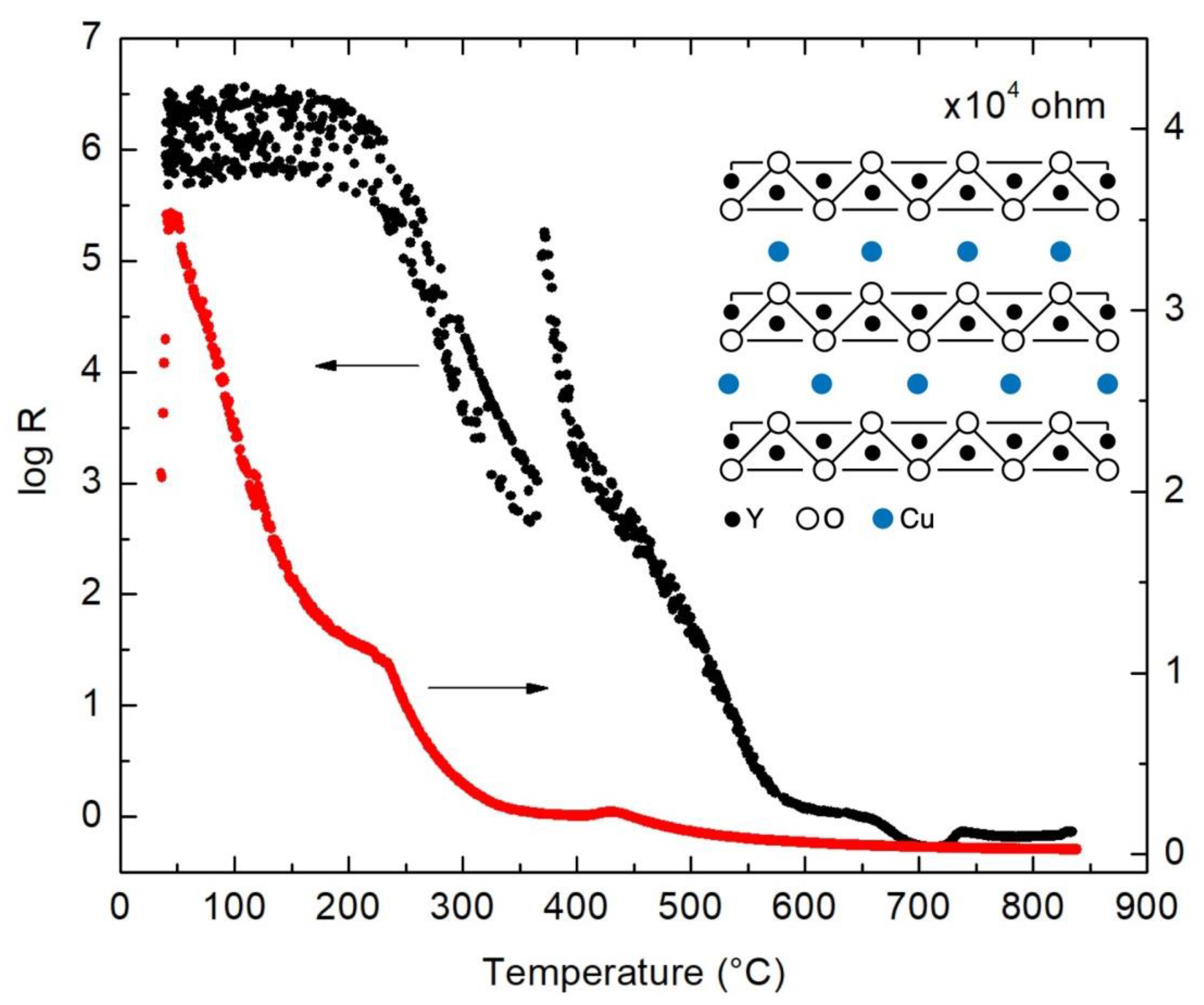

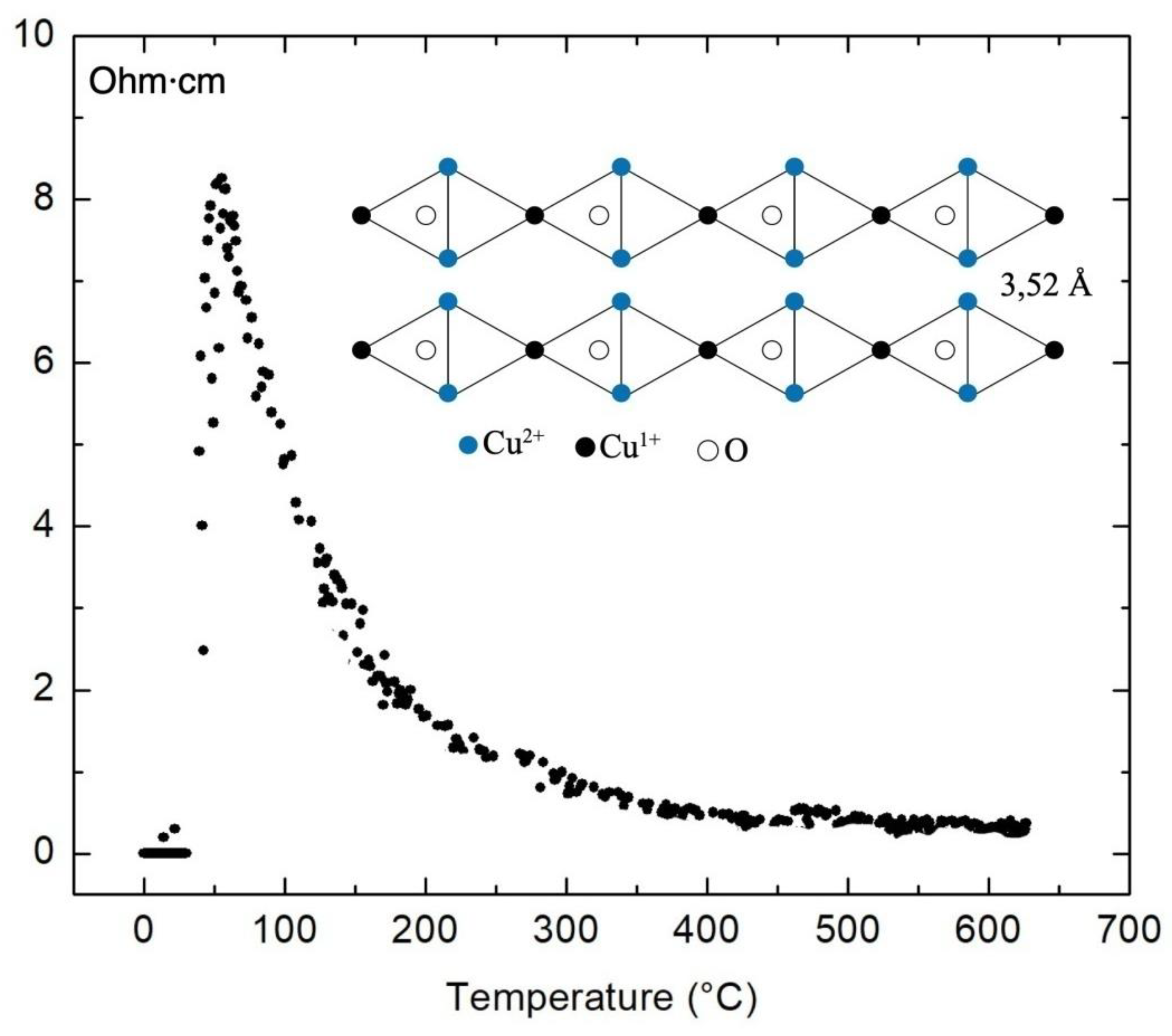

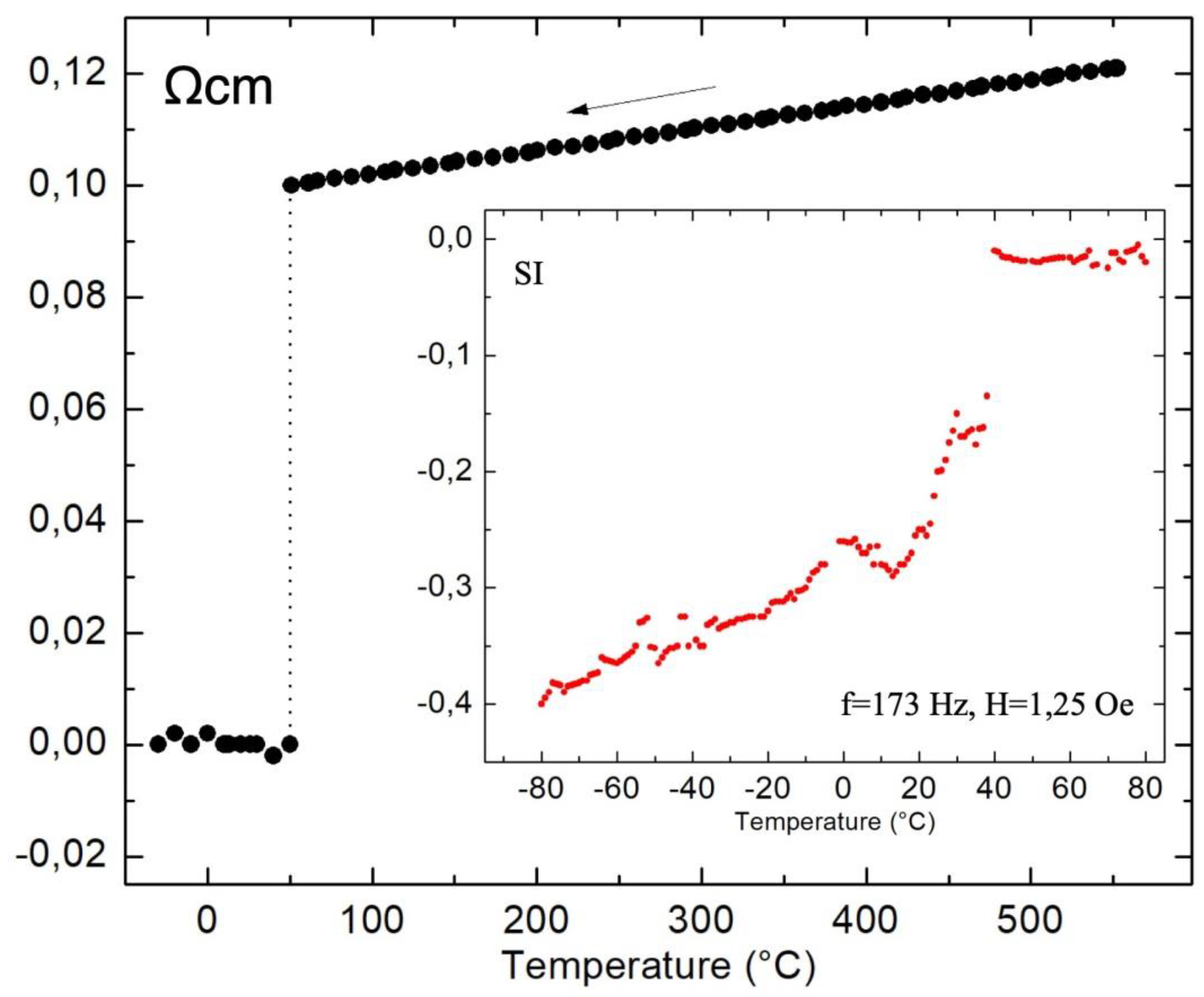

3. Discussion

4. Conclusion

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bednorz, J.G.; Müller, K.A. Possible High Tc Superconductivity in the Ba-La-Cu-O System. Z. Phys. B Condens. Matter. 1986, 64, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Er-Rakho, L.; Michel, C.; Provost, J.; Raveau, B. A. Series of oxygen-defect perovskites containing CuII and CuIII: The oxides La3–xLnxBa3[CuII5–2yCuIII1+2y]O14+y. J. Solid State Chem. 1981, 37, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.K.; Ashburn, J.R.; Torng, C.J.; Hor, P.H.; Meng, R.L.; Gao, L.; Huang, Z.J.; Wang, Y.Q.; Chu, C.W. Superconductivity at 93 K in a New Mixed-Phase Y-Ba-Cu-O Compound System at Ambient Pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1987, 58, 908–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, R.J.; Battlog, B.; van Dover, R.B.; Murphy, D.W.; Sunshine, S.; Siegrist, T.; Remeika, J.P.; Rietman, E.A.; Zahurak, S.; Espinosa, G.P. Bulk Superconductivity at 91 K in Single-Phase Oxygen-Deficient Perovskite Ba2YCu3O9–δ, Phys. Rev. Lett. 1987, 58, 1676–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.V. New York Times, 10. March 1987.

- Djurek, D.; Prester, M.; Knezović, S.; Drobac, D.; Milat, O. Low Resistance State up to 210 K in a Mixed Compound Y-Ba-Cu-O. Phys. Lett. 1987, A123, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djurek, D.; Prester, M.; Knezović, S.; Drobac, D.; Milat, O.; Brničević, N.; Furić, K.; Medunić, Z.; Vukelja, T.; Babić, E. TREATMENT OF Y-Ba-Cu-O SUPERCONDUCTORS BY PULSED ELECTFIC FIELDS AND CURRENTS. Physica 1987, 148B, 196–199. [Google Scholar]

- Djurek, D. Search for Novel Phases in Y-Ba-Cu-O Family, Condens. Matter.

- Ishiguro, T.; Ishizawa, N.; Mizutani, N.; Kato, M. A New Delafossite-Type Compound CuYO2. J. Solid State Chem. 1983, 49, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, R.J.; Zandbergen, H.W.; Ramirez, A.P.; Takagi, H.; Chen, C.T.; Krajewski, J.J.; Peck, J.V., Jr.; Waszcak, J.V.; Meigs, G.; Roth, R.S.; Schneemeyer, L.F. LaCuO2,5+x and YCuO2,5+x, Delafossites: Materials with Triangular Cu2+δ Planes. J. Solid State Chem. 1993, 104, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tendeloo, G.; Garlea, O.; Darie, C.; Bougerol-Chaillout, C.; Bordet, P. The Fine Structure of YCuO2+x Delafossite Determined by Synchrotron Powder Diffraction and Electron Microscopy. Journal of Solid State Chemistry 2001, 156, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlea, V.O.; Darie, C.; Isnard, O.; Bordet, P. Synthesis and neutron powder diffraction structural analysis of oxidiezed delafossite YCuO2.5. Sold State Sciences 2006, 8, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PYYKKÖ, P. Relativistic Effects in Structural Chemistry, Chem. Rev. 1988, 88, 563–594. [Google Scholar]

- Kandpal, H.C.; Seshadri, R. First principles electronic structure of the delafossite ABO2 (A = Cu, Ag, Au; B = Al, Ga, Sc, In, Y): evolution of d10–d10 interactions. Solid State Sciences 2002, 4, 1045–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luttinger, J.M. An Exactly Soluble Model of a Many-Fermion System. J. Math.Phys. 1963, 4, 1154–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldane, F.D.M. “Luttinger liquid theory” of one-dimensional quantum fluids:I. Properties of the Luttinger model and their extension to the general 1D interacting spinless Fermi gas. J. Phys C:Solid State Phys. 1981, 14, 2585–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W.A. Little, Possibility of Synthesizing an Organic Superconductor. Phys. Rev. 1964, 134, A1416–A1424. [CrossRef]

- Jérome, D.; Mazaud, A.; Ribault, M.; Bechgaard, K. Superconductivity in a synthetic organic conductor (TMTSF)2PF6. Journal de Physique Lettres 1980, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, J.; Cooper, J.R.; Jérome, D.; Alavi, B.; Brown, S.E.; Bechgaard, K. Hall Effect in the Normal Phase of the Organic Superconductor (TMTSF)2PF6. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 2674–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korin-Hamzić, B.; Tafra, E.; Basletić, M.; Hamzić, A.; Dressel, M. Conduction anisotropy and Hall effect in the organic conductor (TMTTF)2AsF6: Evidence for Luttinger liquid behavior and charge ordering. Phys. Rev. 2006, B73, 115102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, A.; Vallet, P.; Mole, D.; Rosticher, M.; Taniguchi, K.; Watanabe, E.; Bocquillon, G.; Fe`ve, J.M.; Berroir, C.; Volsin, J.; Cayssol, M.O.; Goerbig, J.; Troost, E.; Baudin, E.; Plaçais, B. Mesoscopic Klein-Schwinger effect in graphene. Nature Physics 2023, 19, 830–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, O. Die Reflexion von Elektronen an einem Potentialsprung nach der relativistischen Dynamik von Dirac. Z. Phys. 1929, 53, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scwinger, J.S. On gauge invariance and vacuum polarization. Phys. Rev. 1951, 82, 664–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, J.C.; Chiao, R.Y. Quantum Optics; Oxford University Press, 1974, p. 60.

- Casimir, H.B.G.; Polder, D. The Influence of Retardation on the London-van der Waals Forces. Phys. Rev. 1948, 713, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casimir, H.B.G. On the attraction between two perfectly conducting plates, Communicated at the meeting: Colloque sur la théorie de la liaison chimique,1948, Paris, April, 29.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).