1. Introduction

On the eve of localization theories in disordered systems Landauer [

1] put forward the systematic calculation of the electric conductivity of metals containing point defects and derived an equation

σ =

e2/

h·[

ΣTi]; summation is extended over scattering obstacles. Equation is widely used in semiconducting nanostructures, and pre-factor is named Landauer quantum conductance entering in various localization theories, quantum Hall effect

, and symbolizes a way toward more universality in the solid state research.

The groundbreaking progress on localization in disordered systems, followed by Anderson [

2] and Mott [

3], triggered a further tremendous search for universality of magnetic and electric properties in solid state physics, optics, etc. The quantum mechanical functions in localized systems are confined in a finite region and they decay exponentially at higher distances. The localization phenomena cover various materials [

4,

5] and optics [6-8]. Experimental data, however, derived from the real objects are scarce and dominantly restricted to the resistive measurements [

9,

10], while accompanied magnetic effects, superposed to resistivity data are rare to trace in the scientific literature.

This paper aims to describe the preparation of the novel copper oxide CuO0.75, indicated by disordered oxygen vacancies, while the X-ray diffraction data stress out maintaining the original structure of the tenorite CuO. In addition to the resistivity, CuO0.75 displays an interesting set of magnetic effects, which start by cooling from T~122 K and are followed by antiferromagnetic transition at T~51 K. In the next step, the experimental data will be discussed in terms of Mott and Anderson theories, as well as, modern scaling models. However, difficulties arise from the fact that theories and models dominantly deal with metals, while CuO0.75 is non-metal indicated by a huge dielectric permittivity ε ~ 1.3·103, evaluated independently in these experiments.

2. Experimental

Oxygen defect form CuO0.75 was produced from the powdered cuprous oxide Cu2O of the particle size 0.5 microns and heated at 388 K in 4 bars oxygen atmosphere. Prior to reaction the powder was heated in vacuum at 423 K in order to remove the traces of gases: like moisture, CO2 and SO2. The slow reaction was monitored during 10 – 12 days by use of the pressure gauge and terminated when oxygen pressure was reduced to the value indicating the necessary stoichiometry CuO0.75. The final product was raw and very hard cluster. Oxygen content was additionally verified by decomposition in 2 bar H2 atmosphere at 673 K.

The powder obtained by subsequent reground of the raw cluster (R-sample) was pressed into pellets of 8 mm in diameter and

d=0.9 mm thickness. In order to measure the four probes electric resistance, the 100 microns gold wires were pressed together with powder. Raw CuO

0.75 is an insulator, but it was observed that conductance may be induced by applied DC current starting with 1 µA and gradually increasing up to 1.5 mA during repeated annealing-cooling cycles (DC-samples) in argon atmosphere. Annealing temperature was 908 K, while the final conductivity of DC samples at room temperature (RT) saturated at 0.08–1.25·10

–2 Ω

–1m

–1. It may be a tedious work to explain this interesting phenomenon in terms conventional chemical and metallurgical methodology. More recent findings [

11,

12] may provide some introductory ideas and hints on possible stimulation of disorder and corresponding increase of the conductivity by use of the conducting currents.

3. Results

Copper oxide CuO is narrow band

p-type semiconductor and crystallographic unit cell belongs to the monoclinic group C2/c with cell dimensions

a = 0.4683 nm,

b = 0.3421 nm

, c = 0.5129 nm;

α = 90

°,

β = 90

°,

γ = 99.784

°. Unit cell contains 4 units formulas, and density is

ρ= 5.94 g·cm

–3, while the oxygen defect form CuO

0.75 exhibits

ρ=5.64 g·cm

–3. Due to one oxygen vacancy per unit cell, CuO

0.75 is expected to be a mixed valence oxide with equal number of Cu

2+ and Cu

+ cations. In this respect, CuO

0.75 resembles the copper oxide Cu

4O

3, known as paramelaconite, with the structure indicating CuO

2 chains along

c-axis [

13]. Pinsard-Gaudart and co-workers reported [

14] the antiferromagnetic transition in Cu

4O

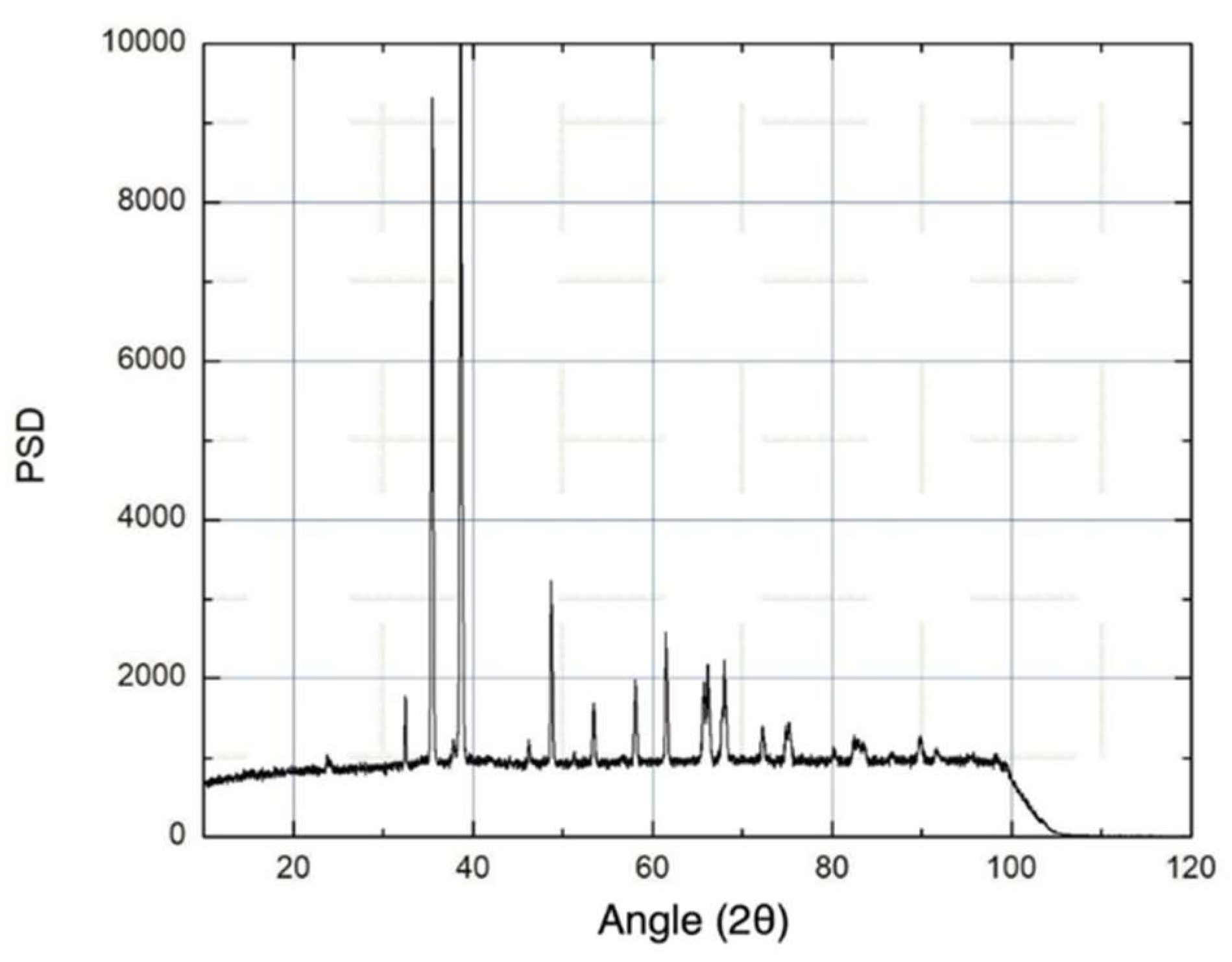

3 at 42 K.XRD data of CuO

0.75 are shown in

Figure 1.

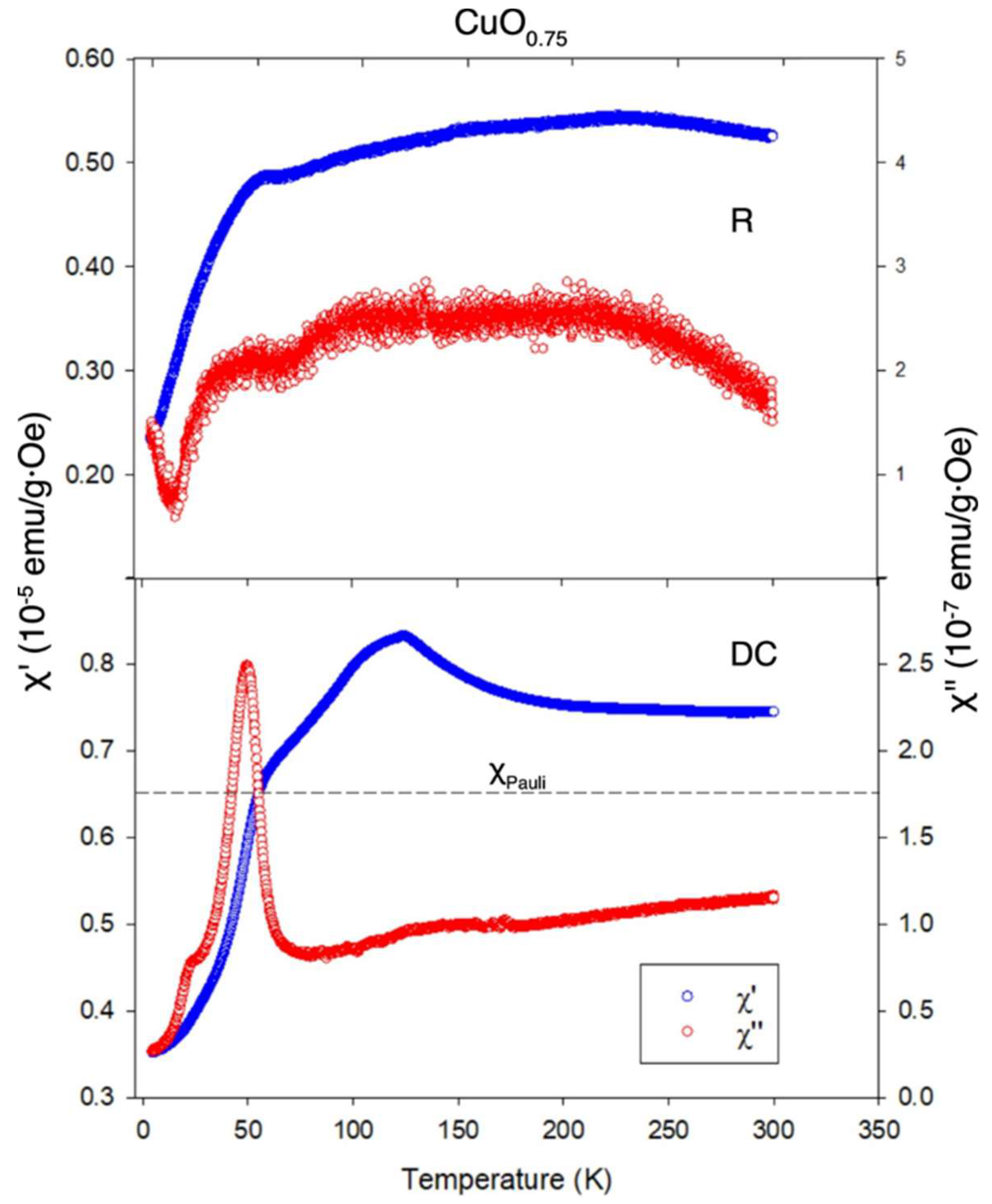

High resolution measurements of AC susceptibility were performed on R- and DC-samples by use of Cryobind susceptometer, and real and imaginary parts are shown in

Figure 2. Samples exhibit a surprising temperature dependence of the susceptibility, and several effects are included. By heating to RT, the magnetic susceptibility reveals three features. At

T = 51 K, both DC- and R-samples, undergo an antiferromagnetic transition. The next feature appears in DC sample at

T = 101 K, while at

TC = 122 K, DC-sample resembles the paramagnetic transition. Both cited transitions are absent in the raw R-sample. At

T > 122 K DC sample obeys the Stoner expression

χ=

χp / [1 –

U·N(

EF)], while the quantities

χp,

U and

N(

EF) are in the respective order; Pauli susceptibility, Coulomb repulsion energy

U(Joule·m

3) and density of states (DOS) on the Fermi surface. The Pauli susceptibility

χP and DOS were evaluated from the inverse susceptibility 1/

χ plotted versus 1/

T. Horizontal dashed line reflects a contribution of the Pauli susceptibility and foreign ingredients; the latter must be subtracted, after an independent measurement on non-reacted Cu

2O. Dimensionless Pauli susceptibility is

χp=2.9·10

–6, while DOS was calculated [

15] from

χp =

μ0·μ

B2·

N(

EF), giving

N(

EF) = 2.8·10

46 Joule

–1·m

–3. The Fermi energy

EF was separately derived from number of states

n = 1/

V0 = 2.4·10

28 m

–3, and

V0 means the volume of the crystallographic unit cell. Fermi wave number is given as

kF = (3

π2·

n)

1/3, and

EF = 3.3 eV.

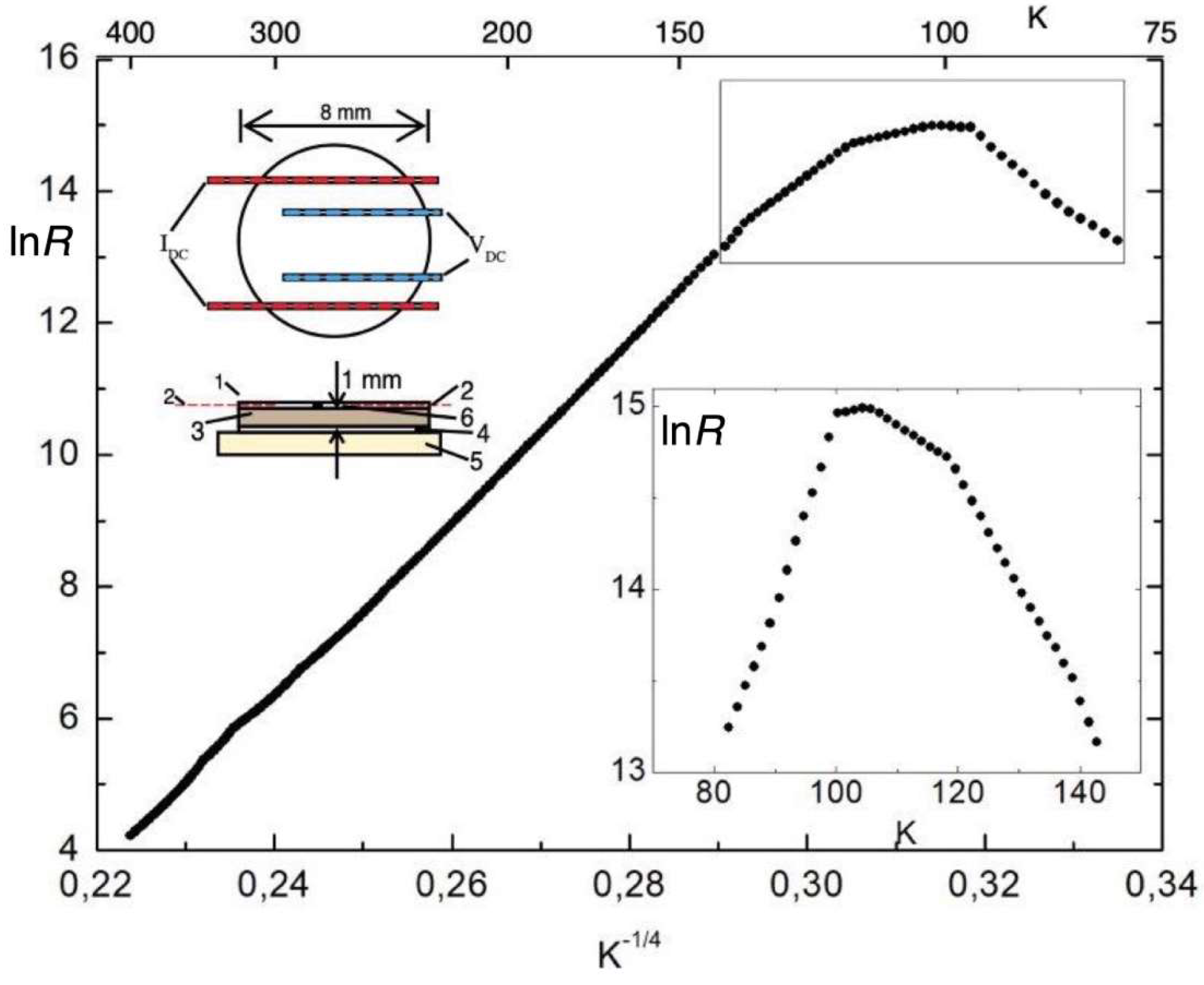

Figure 3 presents the resistance of DC-sample measured by cooling and heating in the range 415 – 80 K. It is evident the linear dependence of ln

R on

T – 1/4 down to

TC = 122 K, when strong linear increase converts in stagnation, which is followed by the sharp downturn at

T =101 K. Linear dependence of ln

R on

T–1/4 is the characteristic behavior of the disordered 3 dimensional (3D) system indicated by localization of the electronic states. Anderson put forward that, in disordered systems, diffusion theories of the conductivity must be replaced by models based upon quantum jumps between the localized states. Continuing upon such a course, Mott developed theory

17 of the variable range hopping, and logarithm of the resistivity was derived as

where 1/α and R are localization length and hopping range respectively. This expression was fitted to the measured dependence ln

R on

T–1/4 in the temperature interval 122 – 415 K when metallic state sets up by further heating. An evaluation of the localization length gives

α–1= 2.1·10

–9 m, while the variable range length at

T =122 K is

R = 2.3·10

–9 m.

R decreases slowly by heating, and Mott expression of the level spacing between two states reads Δ

=α3/

N (

EF)~18.8meV.

Measured electric conductance of CuO0.75 at T= 415 K was G0= 1.5·10–2Ω–1, and evaluated conductivity is σ0 = 0.17 Ω–1·cm–1.When this value should be compared to Mott minimum metallic conductivity σmin= π2·e2/8·z·h·c [ref.16, p.31], it must be encountered the dielectric permittivity of CuO0.75, ε = 1.3·103 in the temperature interval 100 – 415 K. The renormalized value reads σ = ε·σ0 ~ 221 Ω–1cm–1, and it is comparable to the Mott value σmin= 300 Ω–1·cm–1. In further calculations we replace lattice parameter c by α-1 distant localized scatters.

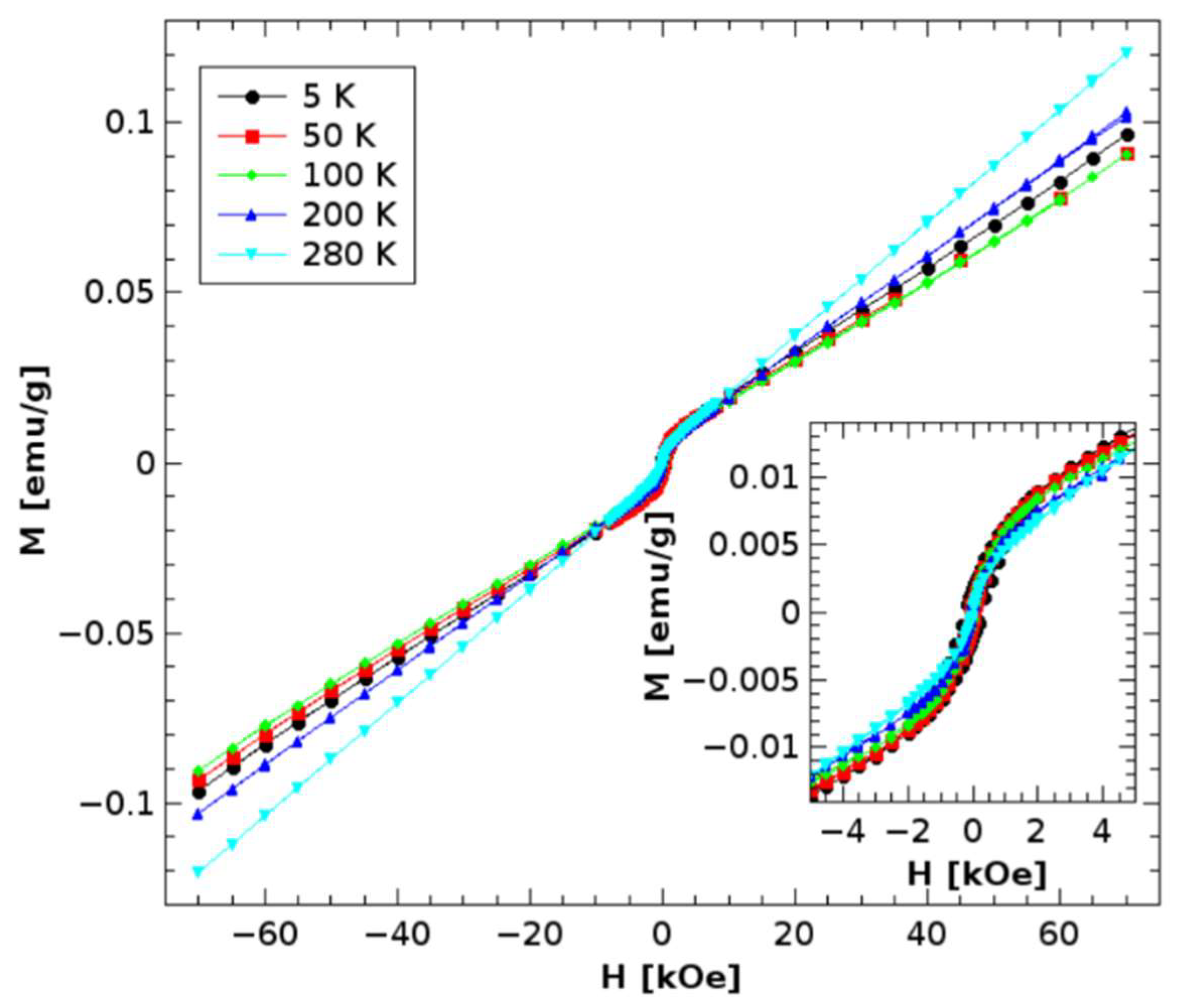

The measurements of hysteresis performed by use of SQUID, are presented in

Figure 4. Measurements of magnetization, dependent on magnetic field at various stable temperatures, sound for antiferromagnetic state below 50 K. Bending of hysteresis around small fields could originate from superparamagnetism of nano-clusters, which may reflect the localized states bound to distinct regions.

4. Discussion

Pinsard-Gaudart and co-workers calculated in paramelaconite Cu

4O

3 the magnetic double-exchange interaction

E = 48,3 K between nearest neighbor Cu

2+ cations Cu

2+–O–Cu

2+ (NN). Such a mechanism may also be certain in CuO

0.75, with oxygen vacancies involved in double-exchange Cu

2+–Vo–Cu

2+ or Cu

2+–Vo–Cu

+. In support, Gao and co-workers [

17] reported a weak ferromagnetism mediated by oxygen vacancies in CuO nanoparticles.

Downturn of the resistance in CuO

0.75 below 122 K may be explained by Zener model of the magnetic double exchange conductivity. Model was originally applied to the resistance [

18] properties of strontium doped manganite (La

1-xSr

x)MnO

3. An exchange is favored by the polarization of the hopping electrons between aligned cation spins Mn

4+–O–Mn

3+, which, in turn, enhances the electric conductance and the magnetization due to the itinerant electron contribution. Zener evaluated the electric conductance

GZ =x·e2E/

h·kBT. E and

x are exchange energy and fraction of ions involved in the exchange respectively.

GZ may compete the resistance divergence

T–1/4 in CuO

0.75 at

T < 122 K giving rise to a possible two fluid conductance. Calculated Zener conductivity reads

σZ ~ 380 Ω

-1·cm

-1, while relative dielectric permittivity is absent in the evaluation.

Thouless [

19] introduced dimensionless conductance

g=G·h/e2. However, the ratio of the measured and Landauer conductance is impractical for testing the scaling theories by experiment, since measured conductance

G is dependent on the sample thickness

d, as being no uniquely defined parameter. We introduce dimensionless conductivity

g =

ε·α−1·G·h/d·e2, and

g gives Thouless energy

ET =g·Δ. Δ = 18.8 meV is the, above evaluated, level spacing, and from the resistance at

T =415 K, Thouless energy reads

ET = 9.8 meV giving

TC=132 K, which should be compared to transition temperature

T = 122 K. Thouless energy and corresponding temperature mark the melting of the localized to extended states, while, upon heating, the

T–1/4 regime starts at temperature

T= 122 K, and extends up to 415 K.

In the next step, an attempt is presented to compare the resistance data to scaling model put forward by Abrahams and co-workers (AALR) [

20]. The problem arises to define the universal scaling length L based on given experimental data. The choice proposed by AALR is the mean free path

l, although

l is doubtful because of strong dependence on temperature. Following a search for common points of AALR model, Mott theory and our experimental data, we introduce localization decay L

=α–1 as a scaling length, since it is independent of temperature. AALR theory introduces parameter

β=d(ln

g)/d(lnL) indicating

β = 0 at the metal-insulator transition. The comparatively easy calculation, for the case CuO

0.75, starts with an elimination of the temperature in Equation (1), which gives the dimensionless conductivity

g =(

ε·α-1·h·σ0/e

2)·exp–

αR[2 + ¾

π]. This expression matches the AALR result for 3D system, and little more algebra results in

β = ln

g, giving

β= 0 for

g = 1, means that metal-insulator transition may be expected when the renormalized conductivity

ε·αo approaches the Landauer quantum conductivity

e2·

α/

h proceeded between two localized points distant

α-1. In the case CuO

0.75 this happens at

T~ 415 K, when exp(

T0 /

T)

1/4 regime starts by cooling.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, a novel copper oxide CuO

0.75 was prepared. It is indicated by one oxygen vacancy per unit cell and exhibits the crystallographic structure of a tenorite CuO. In the interval 122 – 415 K, electric resistance is temperature dependent according to the Mott law exp[(T

0/T)

1/4]. Anderson theory of localization and Mott theory of variable hopping were successfully applied, and characteristic length of exponential decay of the localized state was evaluated

α–1= 2.1 nm, while variable hopping range is R

=2.3·10

–9 m at

T =122 K. It has been shown that Mott’s concept of minimum conductivity in metals

σmin may be extended to nonmetal CuO

0.75, giving rise to a possible universal physical constant. In addition,

σmin has been evaluated by taking in account a calculated [

21] ratio of critical localization potential and band width

Vcrit/

B = 2, confirming this result as to be correct. Dimensionless Thouless conductivity

g was calculated and corresponding Thouless energy

ET, converted to temperature, gives

T~142 K. In order to apply scaling theory of Abrahams and co-workers (AALR), L =

α–1 is chosen as a scaling length, while

β function reads

β= ln

g. At

T = 122 K magnetic measurements reveal the transition to a double exchange interaction indicated by Zener conductivity, which is comparable to the Mott conductivity

σmin. CuO

0.75 undergoes an antiferromagnetic transition at 51 K.