1. Introduction

High-entropy carbides (HECs) represent an advanced class of ceramics consisting of five or more principal metallic elements in near-equiatomic proportions, forming single-phase solid solutions stabilized by high configurational entropy. These materials exhibit outstanding properties, including high hardness, excellent thermal stability, superior oxidation resistance, and low thermal conductivity, which makes them attractive for applications in extreme environments such as aerospace propulsion, nuclear reactors, and thermal protection systems [

1,

2,

3].

Conventional fabrication techniques, such as hot pressing (HP) and spark plasma sintering (SPS), are predominantly used to consolidate HEC powders into bulk ceramics [

4,

5,

6]. For instance, Feng et al. [

6] synthesized dense (Hf–Zr–Ti–Ta–Nb)C ceramics through a two-step process involving carbothermal reduction at 1600

C, followed by hot pressing at 1900

C. Similarly, Castle et al. [

4] used ball-milled monocarbide powders followed by SPS at temperatures up to 2300

C and pressures of 16–40 MPa. Despite their effectiveness, these methods are constrained by high energy demands and/or milti-step processing routes, thereby motivating exploration of more efficient processing strategies.

Microwave-induced hydrogen plasma (MIHP) reduction of metal-oxide precursors, as demonstrated in our recent studies, has emerged as a promising method for synthesizing advanced materials, including high-entropy borides and alloys [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Resistive heating elements used in conventional furnaces or in sintering equipment, can result in substantial thermal energy loss through chamber walls and large contact surfaces with the sample. In contrast, MIHP confines the majority of energy into a small plasma localized in contact with the sample. Minimal energy is conducted or radiated to chamber walls or other non-essential surfaces. Dielectric heating from microwaves occurs throughout the entire volume of the sample, rather than from the outside in, as is the case for conventional heating methods. The dielectric metal oxide precursor powder is particularly efficient in absorbing the microwave energy for heating. Although the sample rests on a ½-inch diameter molybdenum stage, contact is limited to a single face, and the stage remains otherwise electrically and thermally isolated from the reaction site. This configuration minimizes parasitic thermal dissipation and maximizes energy delivery efficiency.

Beyond spatial confinement and thermal isolation, the efficacy of MIHP also derives from the fundamental interactions between microwave energy and the plasma medium. Microwave energy couples efficiently via electron-impact ionization and dielectric losses, leading to localized heating of the green body while maintaining significantly lower bulk reactor temperatures than conventional furnaces [

11]. Energetic electrons in the plasma dissociate molecular hydrogen (H

2) into atomic hydrogen (H) and other reactive species through electron-impact processes. Atomic hydrogen exhibits significantly greater thermodynamic reduction potential than molecular hydrogen, as evidenced by the following standard Gibbs free energy changes:

The positive

for molecular hydrogen reduction indicates a non-spontaneous reaction under standard conditions, whereas the highly negative value for atomic hydrogen reflects a thermodynamically favorable pathway. This thermodynamic advantage underscores the efficacy of hydrogen plasma in enabling low-temperature, energy-efficient reduction of refractory metal oxides [

12]. Notably, MIHP achieves these critical reactions with an electrical energy consumption from a MW source as low as 600 Watts.

This study investigates the feasibility and reproducibility of MIHP for synthesizing a representative high-entropy carbide composition, MoNbTaVWC. Three independent test experiments were conducted under identical synthesis conditions. Crystalline structure and nanoindentation measurements of hardness and elastic modulus were compared across the three test experiments. SEM/EDX was used to evaluate elemental composition and homogeneity.

2. Materials and Methods

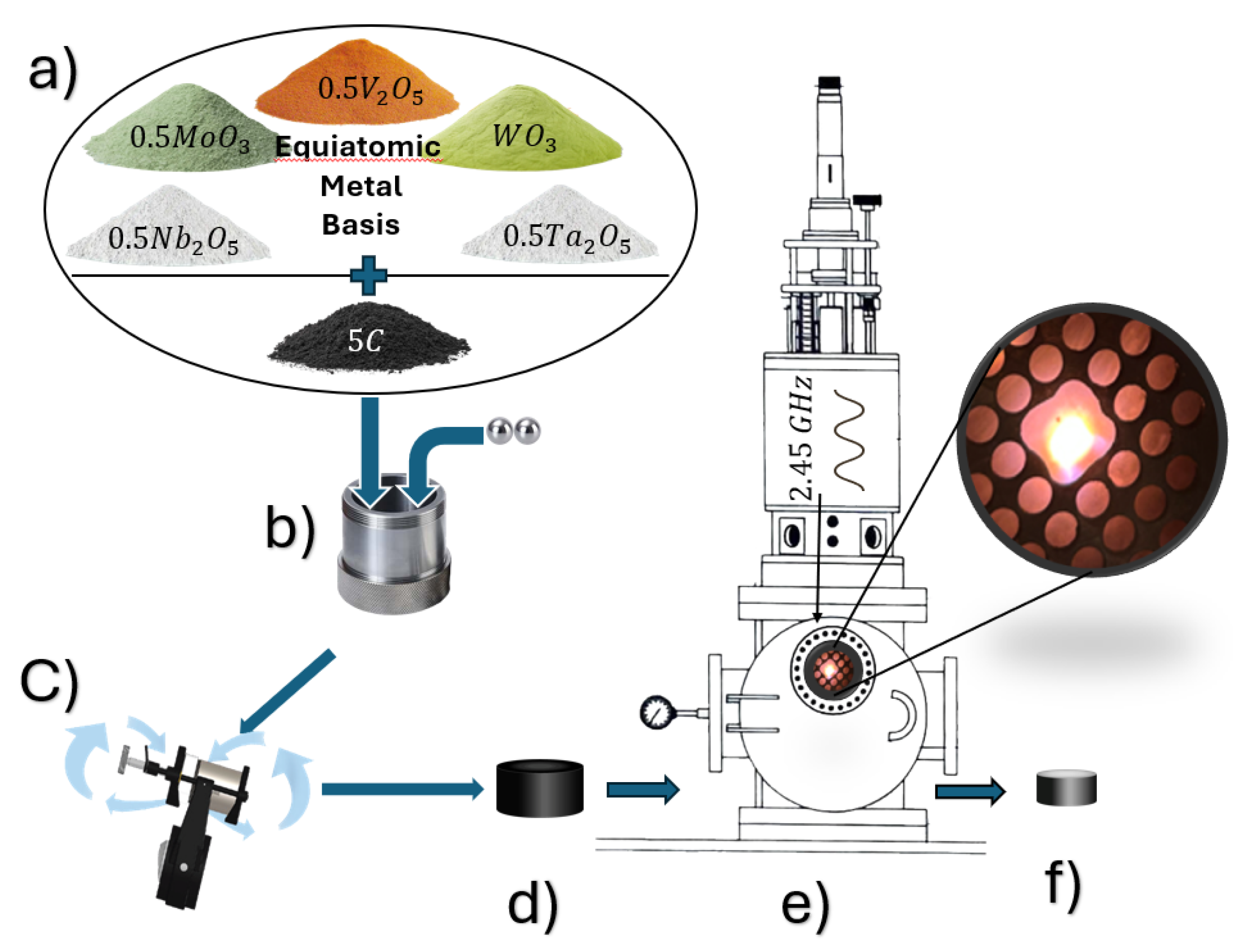

The precursor materials for the synthesis of consisted of high-purity metal oxides—MoO, NbO, TaO, VO, WO and graphite (C). All metal oxides were purchased from Nano Research Elements, with stated purities of 99. 9% and mesh size of 325. Graphite (natural, microcrystalline grade, APS 2–15 µm, 99.9995% metals basis) was sourced from Thermo Fisher Scientific Chemicals.

The precursors were weighed to obtain an equiatomic Mo-Nb-Ta-V-W ratio in the final carbide, based on the global carbothermal reduction reaction scheme shown below.

This equation serves solely as a stoichiometric reference to ensure equiatomic metal ratios in the precursor mixture and is not intended to represent the mechanistic complexity of the MIHP process. The plasma environment contains a spectrum of reactive hydrogen and oxygen-based species—ranging from atomic and molecular hydrogen to charged ions, free electrons, and oxidizing radicals—that collectively enable complex reduction dynamics and intermediate-phase formation.

Each metal oxide exhibits a distinct vapor pressure and volatilization behavior, influenced by local temperature and chamber pressure during processing. As temperature increases, transient intermediates—such as suboxides or intermetallics—may form before consolidating into the final high-entropy carbide phase. Similar transitions were observed in our plasma-assisted synthesis of high-entropy borides [

7]. Consequently, Equation

1 cannot predict the full reaction pathway under these highly non-equilibrium conditions. Empirical tracking of structural evolution is therefore necessary to elucidate the actual synthesis mechanism.

The mixed precursor powders were homogenized by ball milling in a SPEX SamplePrep 8000M Mixer/Mill (Metuchen, NJ, USA) using a WC-lined vial with dimensions of 2.25 in. diameter × 2.5 in. length. Dry milling was performed for 2 hours using two WC balls (7/16 in. diameter), followed by wet milling in acetone for 4 hours using two ZrO

balls (1/2 in. diameter). Wet milling in acetone facilitates improved powder dispersion and helps suppress particle agglomeration, thereby promoting more uniform mixing and compositional homogeneity [

13]. A 10ute cooling interval was introduced after each hour of milling to prevent excessive temperature rise. The mill operated along a figure-8 trajectory to promote uniform mixing and particle refinement.

Green compacts were prepared by uniaxial pressing approximately 300 mg of milled powder into disk-shaped pellets ( 3.5mm height, 5mm diameter) under an applied load of approximately 30 MPa. The complete experimental sequence is illustrated schematically in

Figure 1.

MIHP processing was carried out in a 2.45 GHz microwave plasma reactor (Wavemat Inc., Plymouth, MI, USA) operated at 600 W. The green pellet was placed on a molybdenum stage, the chamber was evacuated to 0.167 Torr, and backfilled with 500 sccm argon to establish a stabilized plasma at 5 Torr. Then gas was transitioned to pure hydrogen over the interval of 10 minutes. When the plasma temperature, measured by optical pyrometry, exceeded 1900 °C, a 90 min dwell time was initiated, during which the temperature stabilized at and pressure at 200 Torr.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used to determine crystal structure via a Malvern Panalytical Empyrean diffractometer equipped with Cu K radiation ( Å), operated at 45 kV and 40 mA. Data were collected using a step size of 0.0131 and a counting time of 16.32 s per step.

The polishing of the MIHP-processed samples was performed using a MetPrep grinding and polishing system. The initial grinding was carried out with 320-grit SiC paper until surface flatness was achieved, followed by 600-grit SiC paper for 2 minutes. Subsequent polishing steps employed 6 µm diamond suspension for 2 minutes, 1 µm diamond suspension for 5 minutes, and a final polish with 0.02 µm colloidal silica for 15 minutes.

Microstructural examination and elemental mapping were carried out using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FEI Quanta FEG 650, Hillsboro, OR, USA) equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), operated at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV.

Nanoindentation testing was performed using an Agilent Nano Indenter G200 system (MTS Nano Instruments, Oak Ridge, TN, USA) equipped with a Berkovich diamond indenter and operated in continuous stiffness measurement (CSM) mode. Instrument calibration was conducted using a fused silica reference standard with an accepted Young’s modulus of , both before and after testing the sample. For each sample, an average of seven indents were performed to ensure statistical reliability of the measured mechanical properties. Re-evaluation of the fused silica reference post-indentation confirmed that the tip geometry remained unchanged throughout the experiments and that calibration accuracy was maintained.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Phase Formation and Reproducibility

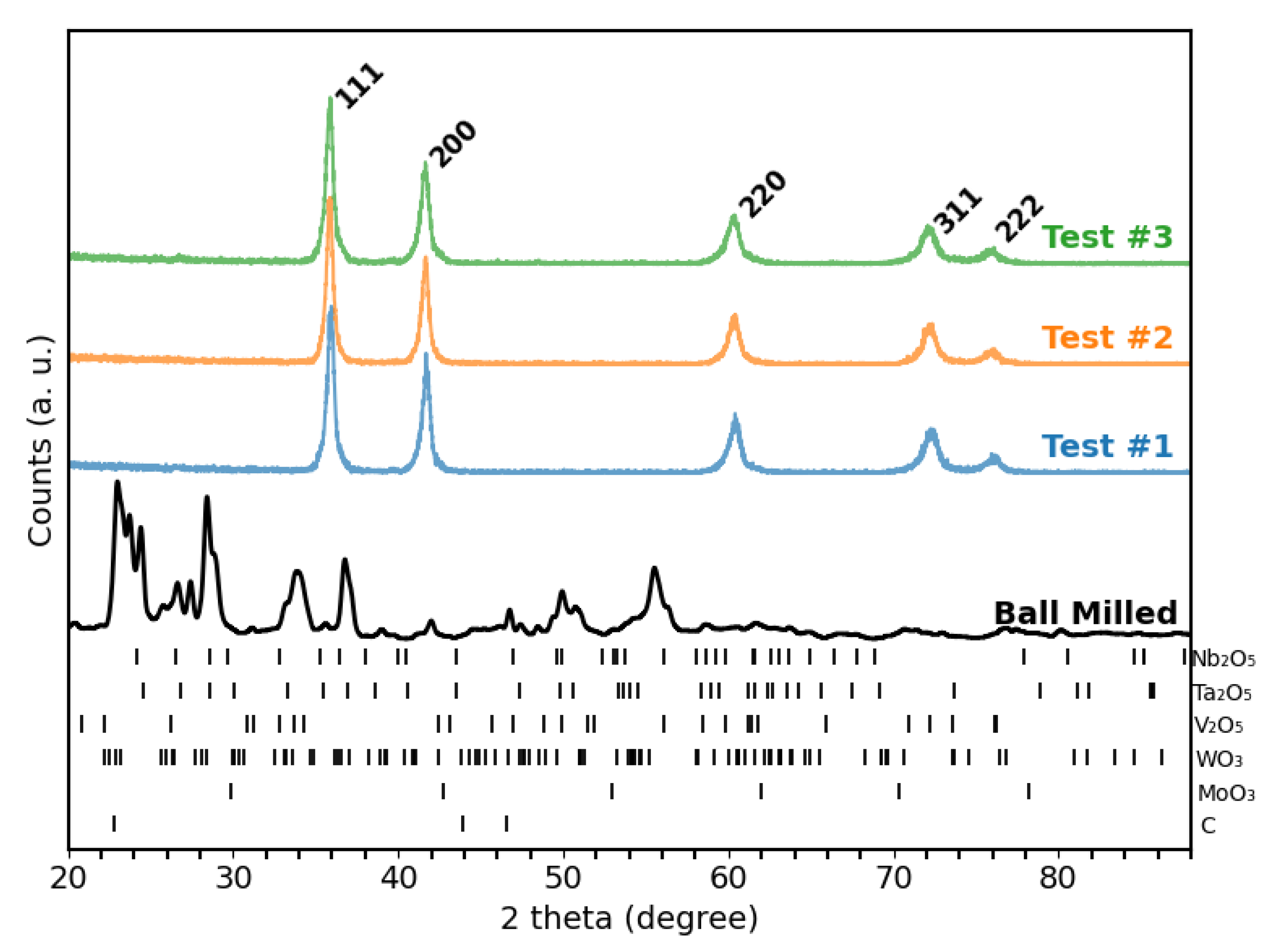

The single-phase FCC structure, expected for the

, was confirmed for each of the three independently synthesized test samples, as shown in

Figure 2. No evidence of residual crystalline oxides or graphite were detected by XRD. The lattice parameters computed for Test#1 through Test#3 were

,

, and

, respectively. These values fall within the reported range of

–

for

[

14,

15,

16].

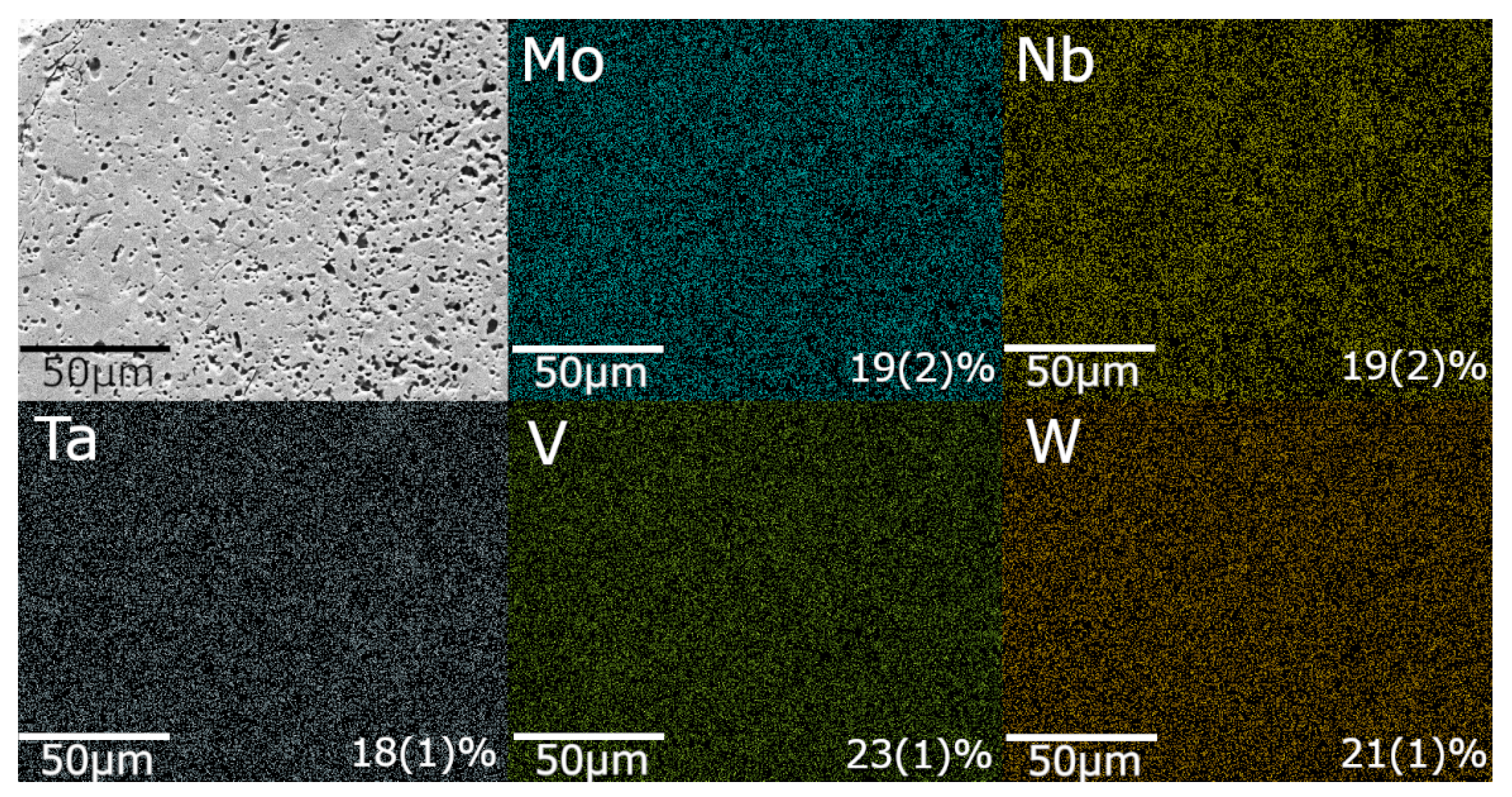

3.2. Elemental Uniformity

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) was employed to evaluate the surface morphology and elemental distribution in the synthesized

samples. As shown in

Figure 3, the EDX elemental maps confirm a near-equiatomic distribution of Mo, Nb, Ta, V, and W, consistent with the nominal equimolar design (

at.% each). The measured compositions deviate by no more than

at.% from the nominal value, which is within the expected compositional uncertainty derived from propagated measurement errors during EDX analysis.

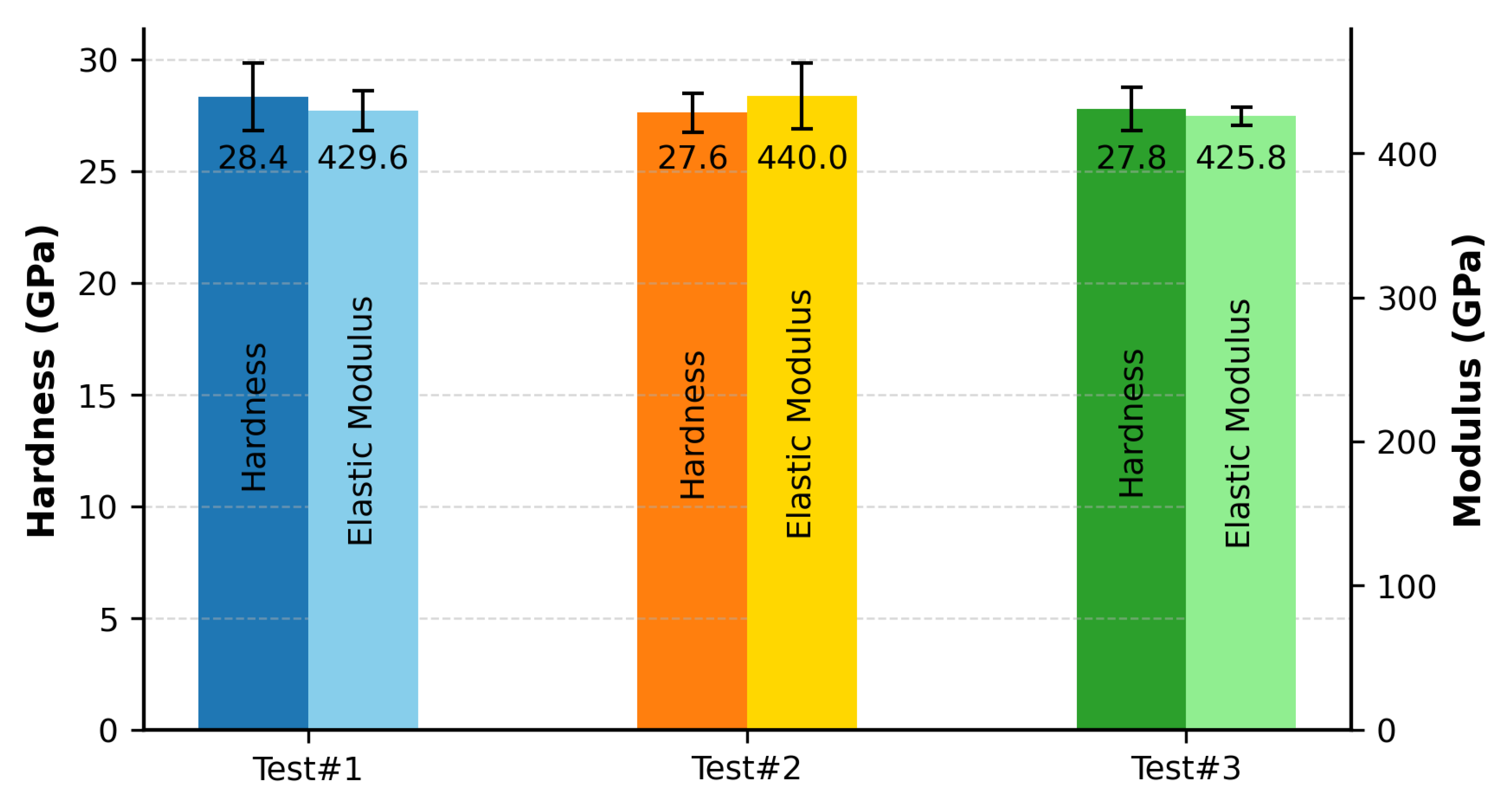

3.3. Mechanical Properties

Nanoindentation measurements were performed using a Berkovich diamond indenter calibrated using a fused silica standard.

Figure 4 presents the averaged hardness and elastic modulus values, determined at an indentation depth of 100 nm.

The nanohardness values measured in this study—

GPa,

GPa, and

GPa for Test#1, Test#2, and Test#3, respectively—fall well within experimentally reported values for this HEC class, ranging from

to

GPa [

14,

16,

17,

18,

19]. While all reported values are categorized as nanohardness, variations in measurement parameters—such as indentation load, tip geometry, and penetration depth—are either unspecified or inconsistent across studies, thereby limiting the scope for strict quantitative comparison.

The corresponding elastic modulus values were determined to be

GPa,

GPa, and

GPa for Test #1, Test #2, and Test #3, respectively. These were compared with the theoretical modulus of 459 GPa predicted by the AFLOW (ROM) computational framework, as reported by Sarker

et al. [

15]. The calculated deviations for the three tests—

,

, and

—all fall within the generally accepted ±10% range, indicating close agreement between experimental results and theoretical predictions.

Furthermore, the elastic modulus values measured in this study fall well within the broader spectrum of experimentally reported values for this HEC class, ranging from

to 551 GPa [

14,

16,

17,

18]. Chen

et al. [

17] observed that microstructural parameters—particularly grain size and pore population—have impact on mechanical properties, leading to slight reductions in nanohardness and more pronounced, often abrupt, variations in elastic modulus. This correlation explains the relatively narrow dispersion in hardness values and the substantially wider spread in modulus data reported across the literature and corroborated in the present work.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) imaging (

Figure 3) revealed the presence of porosity in the MIHP-processed samples. Although the present study did not investigate the individual contributions of microstructural or thermal factors, the measured mechanical properties are consistent with the empirical trends reported in the HEC literature. Specifically, nanohardness values across this material class tend to exhibit relatively narrow dispersion despite compositional and processing differences, whereas elastic modulus values show broader variability and often differ from theoretical predictions due to intrinsic microstructural or methodological factors.

4. Conclusion

This study establishes Microwave-Induced Hydrogen Plasma (MIHP) as a viable synthesis route for high-entropy carbide ceramics. A representative equiatomic metal composition, , was synthesized from metal oxide precursors under MIHP processing conditions at 200 Torr. X-ray diffraction confirmed the formation of a single-phase rocksalt-type structure, with consistent lattice parameters across three independently synthesized samples as determined via Rietveld refinement. SEM/EDX analysis demonstrated nearly equiatomic elemental distribution, consistent with the targeted equimolar design. Nanoindentation measurements yield hardness and elastic modulus values in close agreement with literature-reported benchmarks for the same compositions. These findings demonstrate both the feasibility and reproducibility of MIHP for high-entropy carbide synthesis, and highlight its potential for further development as an energy-accessible processing alternative to conventional high-temperature/high-pressure processing methods.

Future work will focus on correlating MIHP process parameters with microstructural evolution, densification behavior, and functional property optimization to enable broader adoption of this technique in advanced ceramic manufacturing.

References

- Sabat, K.C.; Das, R.K. Reduction of oxide minerals by hydrogen plasma: An overview. Plasma Chemistry and Plasma Processing 2014, 34, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Du, Z.; Liu, X.; Yu, J. Research Progress of High Entropy Carbides. Journal of Wuhan University of Technology-Mater. Sci. Ed. 2024, 39, 1440–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhou, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, B.; Lv, Y.; Yang, W.; Xu, D.; Liu, Y. A review on fundamental of high entropy alloys with promising high–temperature properties. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2018, 760, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castle, E.; Csanádi, T.; Grasso, S.; Dusza, J.; Reece, M. Processing and properties of high-entropy ultra-high temperature carbides. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 8609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, B.; Wen, T.; Nguyen, M.C.; Hao, L.; Wang, C.Z.; Chu, Y. First-principles study, fabrication and characterization of (Zr0. 25Nb0. 25Ti0. 25V0. 25) C high-entropy ceramics. Acta Materialia 2019, 170, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Chen, W.T.; Fahrenholtz, W.G.; Hilmas, G.E. Strength of single-phase high-entropy carbide ceramics up to 2300° C. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 2021, 104, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storr, B.; Catledge, S.A. Synthesis of High Entropy Boride in Reactive MW-Plasma Environments: Enhanced Reducing Capability. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2025, p. 130712.

- Storr, B.; Kodali, D.; Chakrabarty, K.; Baker, P.A.; Rangari, V.; Catledge, S.A. Single-step synthesis process for high-entropy transition metal boride powders using microwave plasma. Ceramics 2021, 4, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storr, B.; Moore, L.; Chakrabarty, K.; Mohammed, Z.; Rangari, V.; Chen, C.C.; Catledge, S.A. Properties of high entropy borides synthesized via microwave-induced plasma. APL Materials 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storr, B.; Catledge, S.A. High entropy alloy MoNbTaVW synthesized by metal-oxide reduction in a microwave plasma. Applied Physics Letters 2024, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabat, K.C. Reduction of oxide minerals by hydrogen plasma: An overview. Plasma Chemistry and Plasma Processing 2014, 34, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sceats, H.J. On the Reduction of Metal Oxides in Non-Equilibrium Hydrogen Plasmas. Ph.d. dissertation, Colorado School of Mines, Arthur Lakes Library, 2018.

- Paksoy, A.; Arabi, S.; Balcı-Çağıran, Ö. Overview of the Dry Milling Versus Wet Milling. In Mechanical Alloying of Ferrous and Non-Ferrous Alloys; Elsevier, 2024; chapter 3. [CrossRef]

- Harrington, T.J.; Gild, J.; Sarker, P.; Toher, C.; Rost, C.M.; Dippo, O.F.; McElfresh, C.; Kaufmann, K.; Marin, E.; Borowski, L.; et al. Phase stability and mechanical properties of novel high entropy transition metal carbides. Acta Materialia 2019, 166, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, P.; Harrington, T.; Toher, C.; Oses, C.; Samiee, M.; Maria, J.P.; Brenner, D.W.; Vecchio, K.S.; Curtarolo, S. High-entropy high-hardness metal carbides discovered by entropy descriptors. Nature communications 2018, 9, 4980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, H.; Zhong, W.; Zhao, H.; Hong, F.; Yue, B. Mechanical properties and high-pressure behavior of high entropy carbide (Mo, Nb, Ta, V, W) C. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials 2024, 121, 106651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wu, Z.; Liu, M.; Hai, W.; Sun, W. Synthesis, microstructure and mechanical properties of high-entropy (VNbTaMoW) C5 ceramics. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2021, 41, 7498–7506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, I.; Kumar, H.; Behera, K.; Makineni, S.; Bakshi, S.; Mandal, A.; Gollapudi, S. Microstructure and indentation of a (MoNbTaVW) C system processed by high energy ball milling followed by spark plasma sintering at 1800° C. Materials Characterization 2025, p. 115124.

- Liu, D.; Zhang, A.; Jia, J.; Meng, J.; Su, B. Phase evolution and properties of (VNbTaMoW)C high entropy carbide prepared by reaction synthesis. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2020, 40, 2746–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).