1. Introduction

With the advantages of cleanliness, non-toxicity, high gravimetric energy density, and excellent efficiency in energy conversion, hydrogen is an ideal energy carrier. It has great potential for application in several industrial contexts, including metallurgy, gasoline refining, municipal power supply, and transportation [

1]. Among these applications, hydrogen fuel cells, which convert the chemical energy of hydrogen directly into electrical energy, represent the most efficient technology available for utilizing hydrogen energy. In recent years, there has been rapid development in hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. To improve the volumetric hydrogen storage density and ensure safety, the Hydrogen at Scale and Horizontal Energy Systems (ISO/TC 197/SC 1) has specified that the on-board hydrogen storage tanks can be filled with hydrogen at a maximum of 70 MPa [

2], which imposes stringent requirements on the construction of hydrogen refueling stations and accelerates their development. The Hydrogen compressor, which pressurizes the hydrogen before refueling, represents a key component of these stations. Conventional mechanical hydrogen compressors suffer from low safety, high noise levels, and maintenance costs, which limit their large-scale application and development [

3]. In contrast, metal hydride hydrogen compressors provide several advantages, such as higher safety, lower environmental impact, quieter operation, reduced maintenance costs, higher hydrogen purification efficiency, and the ability to utilize industrial waste heat. As a result, metal hydride hydrogen compressors are considered as a highly promising technology [

4,

5]. The fundamental component of a metal hydride hydrogen compressor is the hydrogen compression material, which must be capable of absorbing and releasing hydrogen at specified temperatures. It is essential for metal hydride hydrogen compressors to produce hydrogen pressure of 85 MPa to meet the requirements of on-board high-pressure hydrogen storage tanks as well as considering the decompression process of hydrogen charging in practical applications. Therefore, it’s crucial to control the hydrogen desorption plateau pressure of hydrogen compression materials to ensure that it exceeds the target output pressure for optimal performance. Single-stage metal hydride hydrogen compression systems have lower compression ratios and require higher temperatures to achieve the target hydrogen output pressure, resulting in increased energy consumption. To enhance the compression ratio of metal hydride hydrogen compression systems, several hydrogen compression materials with matched plateau pressures can be connected in series for multi-stage pressurization. Peng et al. [

2] reported an innovative three-stage hydrogen compression system to meet the pressurization demand of 85 MPa at a water-bath temperature (< 100 °C), and a successful demonstration of the application at a solid-state hydrogen refueling station was completed. The system, which is used to pressurize hydrogen to various pressure levels at a water bath temperature for different applications, consists of a high-density hydrogen compression material and three types of hydrogen compression materials with matched plateau pressures. Specifically, the high-density hydrogen compression material is capable of compressing hydrogen from 3.2 MPa to 8 MPa, the primary hydrogen compression material can achieve pressurization of hydrogen from 8 MPa to 25 MPa, which is suitable for hydrogen refueling applications in long-tube trailers and low-pressure gas cylinders, the second hydrogen compression material compresses hydrogen from 20 MPa to 45 MPa, which fulfills the requirement of hydrogen supply for hydrogen storage tanks of buses, and the final hydrogen compression material can perform compression of hydrogen from 40 MPa to 85 MPa, which can be used for the supply of hydrogen to the storage tanks of passenger cars.

Selecting suitable hydrogen compression material is crucial for efficient hydrogen compression. In general, the material must meet several requirements, including the ability to withstand high pressures at suitable temperatures, high hydrogen storage capacity, rapid kinetic performance, easy activation, and low production costs [

3]. Many types of alloys have been designed for hydrogen compression over the past few decades, including AB-type alloys [

6,

7], AB

5-type alloys [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], AB

2-type alloys [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], and V-based solid solutions [

19]. Among them, AB

2-type alloys are widely used due to their advantages of high hydrogen storage capacity, long cycle life, low production costs, excellent kinetic, and wide hydrogen plateau pressure [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

In a recent study, to achieve hydrogen pressurization from 8 MPa to 20 MPa, Cao et al. [

17] investigated three series of AB

2-type hydrogen compression materials, Ti

0.92Zr

0.10Cr

1.7-xMn

0.3Fe

x(

x = 0.2-0.4), Ti

0.92Zr

0.10Cr

1.6-yMn

yFe

0.4 (

y = 0.1-0.7) and Ti

0.92+zZr

0.10-zCr

1.3Mn

0.3Fe

0.4 (

z = 0, 0.015, 0.04). The results indicated that increasing the substitution of Cr for Fe increased plateau pressure but reduced hydrogen storage capacity. Remarkably, substituting Mn for Cr significantly enhanced hydrogen capacity, improved plateau characteristics, and minimized hysteresis. In addition, increasing Ti content increased the plateau pressure but decreased hydrogen capacity. These findings highlight the critical role of these elements in optimizing hydrogen compression materials. Among these materials, the Ti

0.92Zr

0.10Cr

1.0Mn

0.6Fe

0.4 alloy is a promising high-performance hydrogen compression material. It can be activated after several hydrogen absorption/desorption cycles at room temperature, with a notable hydrogen capacity of 1.86 wt.% at 10 °C and a desorption pressure of 27.94 MPa at 90 °C. Furthermore, it exhibits satisfactory cycling durability and mere hysteresis.

Based on the above reports, in this work, to achieve the application requirements of hydrogen refueling applications in long-tube trailers and low-pressure gas cylinders, the Ti0.92+xZr0.1-xCr1.0Mn0.6Fe0.4 (x = 0, 0.01, 0.02, 0.03) alloys were prepared by substituting Zr with Ti, which is cheaper and has a smaller atomic radius. The microstructure and hydrogen compression performance of the alloys were investigated systematically to develop the compression materials capable of compressing hydrogen to 25 MPa at water bath temperature.

2. Experimental Details

2.1. Materials

Ti, Cr, and Fe grains (manufactured by China New Matel Materials Technology Co, Ltd.), as well as Zr grains and electrolytic Mn flakes (manufactured by ZhongNuo Advanced Material (Beijing) Technology Co. Ltd), were utilized as ingredients for fabrication of alloy samples, and the purity of the materials was as follows: Ti 99.9%, Cr 99.9%, Fe 99.9%, Zr 99.95%, and Mn 99.8%.

2.2. Preparation of Alloys

Alloy samples of Ti0.92+xZr0.1-xCr1.0Mn0.6Fe0.4 (x = 0, 0.01, 0.02, 0.03) alloys were prepared by vacuum arc melting under an argon atmosphere. Considering the relatively high equilibrium vapor pressure of Mn, there was a risk of weight loss during fabrication. To mitigate this, an additional quantity of Mn was added (5 wt.%). All the alloys were melted five times to ensure compositional homogeneity. To avoid oxidation, the sample ingots were transferred to a glovebox with an argon atmosphere for preservation.

2.3. Chemical Composition and Structural Analysis

The phase composition and structure of the alloys were measured by an X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Rigaku SmartLab, Japan) in the 2θ range of 10˚ to 90˚ with a step size of 0.02˚, and the crystallographic date was further acquired using HighScore Plus software. The reliability of the fitting was assessed using the goodness-of-fit parameter S defined as S = Rwp/Re, where Rwp is a residue of the weighted pattern and Re is the statistically expected residue. The element distribution and morphology alteration of alloy samples were characterized by a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Merlin Compact, Germany) equipped with energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS). The precise chemical composition of the alloys was analyzed using wavelength-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF, ARL Perform’X, USA).

2.4. Performance Evaluation

The hydrogen storage properties of alloys, including the thermodynamic pressure-composition-temperature (P-C-T) curves, kinetic curves, and cyclic stability, were measured by a Sieverts-type apparatus (PCT, GRIMAT-PCT-SD, China). Firstly, the surface of samples was polished to remove the inevitable oxide layer of as-cast alloy ingots. Subsequently, alloy samples were pulverized and sieved by a 200-mesh sieve within a glovebox. About 2 g of the alloy powder was transferred to the stainless steel reactor, which was then connected to the Sieverts-type apparatus. Alloy samples must undergo the activation process before testing. Initially, the reactor containing the alloy powder was evacuated to 0.001 MPa at 300 °C for 1 hour to remove the water vapor and gas impurities from the surface of the alloy. Subsequently, the reactor was rapidly cooled to -10 °C. While the reactor temperature remained constant, 9 MPa of hydrogen was charged into the reactor for 2 h. After about 5 cycles of hydrogen absorption and desorption, the two kinetic curves obtained were closely matched, indicating complete activation. Then the P-C-T curves for absorption and desorption were measured at -20 °C, 0 °C, 10 °C and 20 °C, respectively. Kinetic curves and 10 hydrogenation-dehydrogenation tests of the selected alloy were conducted at 10 °C.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Microstructure Characterization

Figure 1 shows the XRD patterns of the Ti

0.92+xZr

0.1-xCr

1.0Mn

0.6Fe

0.4 (

x = 0, 0.01, 0.02, 0.03) alloys prepared in this work. The crystallographic structures are consistent with the TiCr

1.5Mn

0.5 alloy (JDPDS: 52-0817), exhibiting a C14-Laves phase structure (space group P63/mmc, No.194). No other phase is found in the XRD patterns.

The crystallographic data of the alloys calculated from XRD patterns are listed in

Table 1. The goodness-of-fit parameter S of all XRD patterns fitted is approximately 2, indicating that the crystallographic data obtained from the fitting calculations are reliable. As the amount of Ti substituting for Zr increases, the lattice constant

a decreases from 4.8774 Å to 4.8724 Å, while

c decreases from 8.0033 Å to 7.9933 Å. Consequently, the unit cell volume decreases from 164.8849 Å

3 to 164.3392 Å

3. This is primarily attributable to the smaller atomic radius of Ti than Zr. The ratios of c/a are observed to be approximately 1.64, indicating that the alloys exhibit isotropic shrinkage of the unit cells after the substitution. The average number of outer electrons (ANOE) for the alloys is 5.788. According to the research by Yartys et al. [

30], the crystallographic structure of the Laves type is closely linked to the average number of outer electrons present in the alloy, with hexagonal C14 type structures forming when the ANOE ranges from 5.3 to 7. Hence, the ANOE for the alloys prepared in this work is 5.788, within the range of 5.3 to 7. The formation of a C14-type structure is consistent with the XRD analysis.

The phase composition and element distribution of the alloys were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS), and X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) analysis. The backscatter electron (SEM) images of Ti

0.92+xZr

0.1-xCr

1.0Mn

0.6Fe

0.4 (

x = 0, 0.01, 0.02, 0.03) alloys are shown in

Figure 2. It is observed that all of the alloys exhibit a multiphase structure rather than the single-phase microstructure that would be expected. This absence of the secondary phase from the XRD patterns could be attributed to fine particles and the low concentration of the secondary in alloys. The different spots and mapping compositions of the alloys are analyzed by EDS as shown in Table S1. The results show that the dark phase exhibits a Ti segregation phenomenon, while the white phase shows Zr segregation. With increasing amounts of Ti substituting for Zr, the area of the dark phase slightly expands, and the composition approaches that of the AB-type alloy. Patel et.al [

31] studied the effect of Zr on the microstructure of TiFe alloys and found that the content of the TiFe main phase decreased from 93% to 89%, while the content of the TiFe

2 secondary phase increased from 7% to 11% with the addition of 2 wt.% Zr. It can be speculated that the TiFe alloy is formed easily with an increased content of Ti in Ti

0.92+xZr

0.1-xCr

1.0Mn

0.6Fe

0.4 (

x = 0, 0.01, 0.02, 0.03) alloys, which would correspond to an increase in the area of the dark phase observed by EDS. As illustrated in Table S1>, there are some deviations in the chemical composition between EDS analysis and theoretical composition. This phenomenon may be due to the inhomogeneous composition of the as-cast alloys.

The elemental mapping image of Ti

0.94Zr

0.08Cr

1.0Mn

0.6Fe

0.4 is shown in

Figure 3, and the results of the other alloys are provided in Figure S1. The enrichment of the Ti and Zr elements can be clearly seen in the graph of the Ti

0.95Zr

0.07Cr

1.0Mn

0.6Fe

0.4 alloy. Zhou et al [

32] reported a similar phenomenon in the study of Ti-Zr-Cr-Mn alloy. The X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) analysis was used to determine the final chemical composition of all samples, and the results are shown in

Table 2. It can be observed that the final chemical compositions of the alloys differ from the theoretical compositions, which may be due to the inhomogeneous composition of the as-cast alloys or potential errors in the testing equipment.

3.2. Hydrogen Compression Properties

The P-C-T curves of Ti

0.92+xZr

0.1-xCr

1.0Mn

0.6Fe

0.4 (

x = 0, 0.01, 0.02, 0.03) alloys are displayed in

Figure 4, and their relevant hydrogen storage characteristics are listed in

Table 3. The results indicate that as the amount of Ti substituting for Zr increased, the hydrogen plateau pressure gradually increased, which can be attributed to the interstitial size effect. Lundin et al. [

33] proposed that the increase in the unit cell volume leads to an increase in the interstitial size and a decrease in the plateau pressure. However, the maximum hydrogen storage capacity did not show a significant decreasing trend with increasing substitution, which contradicts the previous studies [

14,

34,

35]. The result may be due to the inconsequential change in hydrogen storage capacity caused by the minimal substitution, potential errors in the testing equipment, and the interaction of the synergistic effect among multiphase structures [

36] and the interstitial size effect. The hysteresis factor shows a decreasing trend with increasing substitution, the main reason for this is the weaker hydrogen affinity of Ti than Zr, so the hydrogen release is easier and the required hydrogen desorption plateau is higher under the same conditions with a higher hysteresis, which is consistent with the findings reported by Zotov et al [

37].

The compression ratio (R

p), a critical performance parameter for the hydrogen compression process in metal hydride hydrogen compressors, can be expressed by Equation (1) [

2]:

where P

des(T

H) is the hydrogen desorption plateau at high temperature, P

abs(T

L) is the hydrogen absorption plateau at low temperature,

is the enthalpy change of dehydrogenation process of the alloy, R is the ideal gas constant, T is the thermodynamic temperature, and

is the hydrogen plateau hysteresis at low temperature.

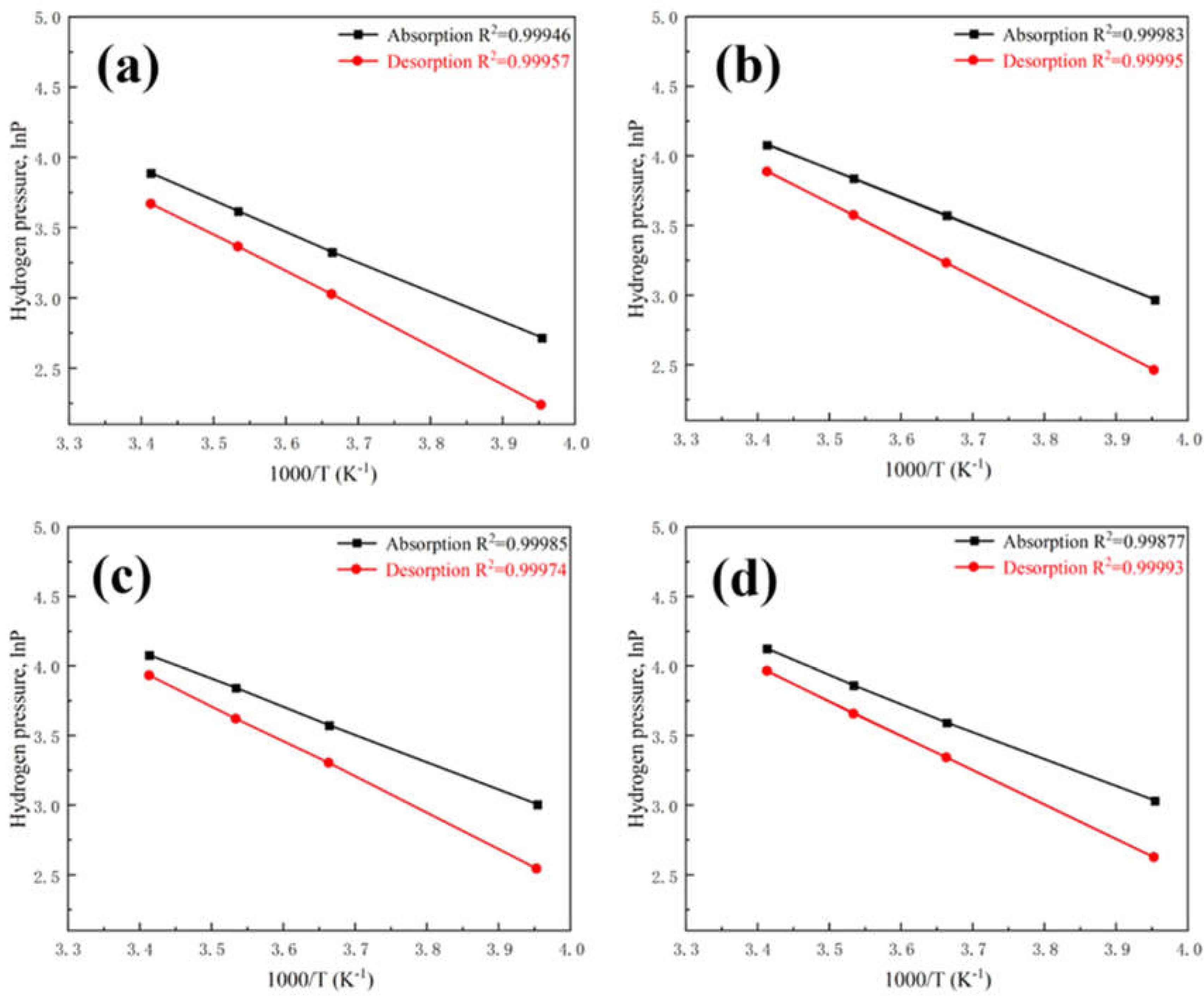

Based on the P-C-T curves of the alloys at different temperatures, the fitting plots of lnP vs 1000/T for hydrogenation and dehydrogenation by van’t Hoff equation are presented in

Figure 5. Satisfactory linear correlations are obtained in all cases with an R

2 value exceeding 0.998, indicating that the evaluated thermodynamic parameters of the alloys are reliable. The enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) of the alloys calculated by van’t Hoff curves, hydrogen absorption plateau at 30 °C, hydrogen desorption plateau at 80 °C, and the corresponding compression ratio are presented in

Table 4. The results indicate that with the increase of substitution, both enthalpy and entropy values showed a decreasing trend. The Ti

0.94Zr

0.08Cr

1.0Mn

0.6Fe

0.4 alloy exhibited the highest compression ratio of 3.08. From equation (1), it can be seen that to obtain a large compression ratio, a large enthalpy change (∆H) and a small hysteresis (

) are required. According to the results in

Table 3, it can be seen that the Ti

0.94Zr

0.08Cr

1.0Mn

0.6Fe

0.4 alloy exhibits the lowest hysteresis factor, thereby demonstrating the largest compression ratio. According to the van’t Hoff curve, the hydrogen absorption plateau at 35.9 °C is 8 MPa, while the hydrogen desorption plateau at 83.9 °C is 25 MPa. The alloy exhibits the ability to absorb hydrogen up to a large amount under 8 MPa at below 35.9 °C and release hydrogen exceeding 25 MPa at above 83.9 °C, with a high compression ratio.

Considering the working conditions of metal hydride hydrogen compressors, the Ti0.94Zr0.08Cr1.0Mn0.6Fe0.4 alloy is recognized as a potentially optimized material.

3.3. Cyclic Properties

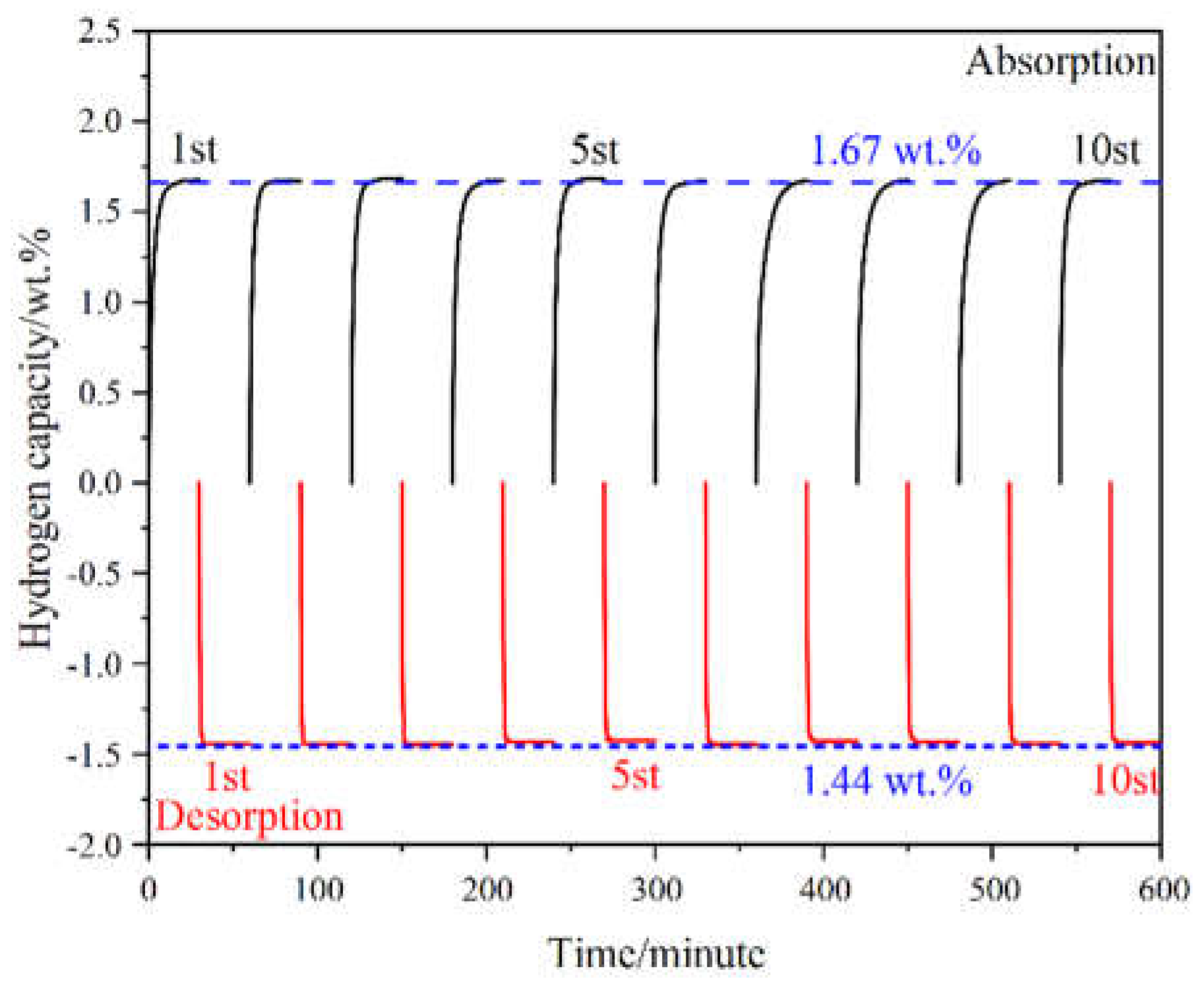

The cyclic properties were crucial for the practical application in metal hydride hydrogen compressors. The cyclic stabilities of the Ti

0.94Zr

0.08Cr

1.0My n

0.6Fe

0.4 alloy were conducted at 10 °C, and the results were shown in

Figure 6. The hydrogen absorption kinetic curves were measured under 8 MPa followed by a desorption measurement for 30 minutes. Within 10 hydrogenation-dehydrogenation tests, the hydrogen storage capacity remained essentially unchanged. The hydrogenation and dehydrogenation capacities remained at around 1.67 wt.% and 1.44 wt.% respectively, exhibiting excellent cyclic stability. It is evident that the quantity of hydrogen released is less than that absorbed. The primary reason for this discrepancy is the inherent limitations of the Sieverts method. Given the limitations of the equipment in terms of volume, it is inevitable that a certain quantity of hydrogen will remain in the reactor at the point of equilibrium, preventing complete dehydrogenation of the alloy. After the dehydrogenation was completed, a residual hydrogen pressure of approximately 0.2 MPa remained in the device, reducing the total amount of hydrogen released. Further, in order to evaluate the practicality of the material future, our next work is to put the material into the device to test the hydrogenation-dehydrogenation in the actual application scenario.

4. Conclusion

In summary, Ti0.92+xZr0.1-xCr1.0Mn0.6Fe0.4 (x = 0, 0.01, 0.02, 0.03) alloys were successfully prepared and their structures and hydrogen compression properties were systematically studied. Characterization results displayed that the main phase of these alloys exhibits a C14-Laves phase structure. With increasing amounts of Ti substituting for Zr, the unit cell volume of the alloys decreases, the absorption and desorption plateau increases, the area of the Ti segregation phase expands and the composition becomes close to those of the AB-type alloy. Among these alloys, the Ti0.94Zr0.08Cr1.0Mn0.6Fe0.4 alloy is a promising candidate for metal hydride hydrogen compressors. The desorption pressure at 83.9 °C is determined to be 25 MPa by van’t Hoff fitting plots, fulfilling the requirement of producing over 25 MPa hydrogen pressure in water-bath environments with a high compression ratio of 3.08. The alloy can be hydrogenated to saturation under 8 MPa at 10 °C, exhibiting a capacity of 1.67 wt.%. Notably, excellent cyclic stability is achieved simultaneously. Therefore, this study provides valuable insights for the design of hydrogen compression materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L., Y.F. and S.Z.; methodology, J.L., D.Z. and S.Z; software, Z.Y., J.L. and X.W.; validation, D.Z. and J.L.; Formal analysis, S.Z. and Z.Y; investigation, J.L. and D.Z.; resources, X.W., Y.F. and S.Z.; data curation, J.L. and Y.G.; writing-original draft, J.L and Y.G..; writing-review and editing, J.L., Y.F. and S.Z.; visualization, J.L. and Y.G.; supervision, S.Z. and Y.F.; project administration, S.Z. and Y.F.; Funding acquisition, S.Z. and Y.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO.U22A20120, 52301269); the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (NO.242300421184).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Schlapbach, L.; Züttel, A. Hydrogen-storage materials for mobile applications. Nature 2001, 414, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Z.; Li, Q.; Ouyang, L.; Jiang, W.; Chen, K.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhu, M. Overview of hydrogen compression materials based on a three-stage metal hydride hydrogen compressor. J. Alloy. Compd. 2022, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdanghi, G.; Maranzana, G.; Celzard, A.; Fierro, V. Review of the current technologies and performances of hydrogen compression for stationary and automotive applications. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2019, 102, 150–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, B.S.; Muthukumar, P. Development of Double-Stage Metal Hydride–Based Hydrogen Compressor for Heat Transformer Application. J. Energy Eng. 2015, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumar, P.; Maiya, M.P.; Murthy, S. Parametric studies on a metal hydride based single stage hydrogen compressor. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2002, 27, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasilva, E. Industrial prototype of a hydrogen compressor based on metallic hydride technology. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1993, 18, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, R.; Chen, C.; Wang, Q. Hydrogen storage properties of TixFe+ywt.% La and its use in metal hydride hydrogen compressor. J. Alloy. Compd. 2006, 425, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, R.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, Q. Hydrogen storage properties of (La–Ce–Ca)Ni5 alloys and application for hydrogen compression. Mater. Lett. 2007, 61, 1101–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Bei, Y.; Song, X.; Fang, G.; Li, S.; Chen, C.; Wang, Q. Investigation on high-pressure metal hydride hydrogen compressors. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2007, 32, 4011–4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, K.; Ishido, Y.; Ono, S. A novel thermal engine using metal hydride. Energy Convers. 1979, 19, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Cao, Z.; Xiao, X.; Li, R.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhan, L.; Li, Z.; Jiang, L.; Chen, L. Dynamically Staged Phase Transformation Mechanism of Co-Containing Rare Earth-Based Metal Hydrides with Unexpected Hysteresis Amelioration. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 3783–3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Mal, H.H. A LaNi5-Hydride Thermal Absorption Compressor for a Hydrogen Refrigerator. Chem. Ing. Tech. 1973, 45, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurencelle, F.; Dehouche, Z.; Goyette, J.; Bose, T. Integrated electrolyser—metal hydride compression system. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2006, 31, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Zhou, P.; Xiao, X.; Zhan, L.; Jiang, Z.; Piao, M.; Wang, S.; Jiang, L.; Chen, L. Studies on Ti-Zr-Cr-Mn-Fe-V based alloys for hydrogen compression under mild thermal conditions of water bath. J. Alloy. Compd. 2022, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Zhou, P.; Xiao, X.; Zhan, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Chen, L. Investigation on Ti–Zr–Cr–Fe–V based alloys for metal hydride hydrogen compressor at moderate working temperatures. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 21580–21589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayebossadri, S.; Book, D. Development of a high-pressure Ti-Mn based hydrogen storage alloy for hydrogen compression. Renew. Energy 2019, 143, 1010–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Piao, M.; Xiao, X.; Zhan, L.; Zhou, P.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Jiang, L.; Xu, F.; Sun, L.; et al. Development of (Ti–Zr)1.02(Cr–Mn–Fe)2-Based Alloys toward Excellent Hydrogen Compression Performance in Water-Bath Environments. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2023, 6, 1913–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Penmathsa, A.; Sun, T.; Gallandat, N.; Li, J.; Park, J.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, P.; Yoon, N.; Jang, J.-H.; et al. Development of Ti-Zr-Mn based AB2 type metal hydrides alloys for an 865 bar two-stage hydrogen compressor. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 72, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, J.J.; Holtz, A.; Wiswall, R.H. A New Laboratory Gas Circulation Pump for Intermediate Pressures. Rev. Sci. Instruments 1971, 42, 1485–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xiao, X.; Chen, L.; Fan, X.; Liu, L.; Li, S.; Ge, H.; Wang, Q. Influence of Ti super-stoichiometry on the hydrogen storage properties of Ti1+xCr1.2Mn0.2Fe0.6 (x=0–0.1) alloys for hybrid hydrogen storage application. J. Alloy. Compd. 2013, 585, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, Y.; Kawai, Y.; Towata, S.-I.; Matsunaga, T.; Shinozawa, T.; Kimbara, M. Development of metal hydride with high dissociation pressure. J. Alloy. Compd. 2006, 419, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobet, J.-L.; Darriet, B. Relationship between hydrogen sorption properties and crystallography for TiMn2 based alloys. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2000, 25, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayanti, I.D.; Denys, R.; Suwarno; Volodin, A. A.; Lototskyy, M.; Guzik, M.N.; Nei, J.; Young, K.; Roven, H.J.; Yartys, V. Hydrides of Laves type Ti–Zr alloys with enhanced H storage capacity as advanced metal hydride battery anodes. J Alloys Compd. 2020, 828, 154354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Cao, Z.; Xiao, X.; Zhan, L.; He, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Yan, M.; Li, Z.; Chen, L. Development of RE-based and Ti-based multicomponent metal hydrides with comprehensive properties comparison for fuel cell hydrogen feeding system. Mater. Today Energy 2023, 33, 101258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barale, J.; Ares, J.R.; Rizzi, P.; Baricco, M.; Rios, J.F.F. High pressure hydrogen compression exploiting Ti1.1(Cr,Mn,V)2 and Ti1.1(Cr,Mn,V,Fe)2 alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 2023, 947, 169497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yan, Y.; Huang, H.; Liu, B.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, B.; Lv, W.; Yuan, J.; Wu, Y. Effects of the different element substitution on hydrogen storage properties of Ti0.8Zr0.2Mn0.9Cr0.6V0.3M0.2 (M = Fe, Ni, Co). J. Alloy. Compd. 2022, 908, 164605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Zhou, C.; Ouyang, L.; Liu, J.; Zhu, M.; Sun, T.; Wang, H. High-pressure hydrogen storage performances of ZrFe2 based alloys with Mn, Ti, and V addition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 9836–9844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, X.; Dong, Z.; Xu, L.; Chen, C. A study on 70MPa metal hydride hydrogen compressor. J. Alloy. Compd. 2010, 502, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, K.; Cheng, H.; Yan, K.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jin, H.; Zheng, Z. New insights into the hydrogen storage performance degradation and Al functioning mechanism of LaNi5-Al alloys. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 24904–24914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yartys, V.A.; Lototskyy, M.V. Laves type intermetallic compounds as hydrogen storage materials: A review. J. Alloy. Compd. 2022, 916, 165219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.K.; Duguay, A.; Tougas, B.; Schade, C.; Sharma, P.; Huot, J. Microstructure and first hydrogenation properties of TiFe alloy with Zr and Mn as additives. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Li, W.; Hu, H.; Zeng, H.; Chen, Q. Ce-Doped TiZrCrMn Alloys for Enhanced Hydrogen Storage. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 3997–4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundin, C.; Lynch, F.; Magee, C. A correlation between the interstitial hole sizes in intermetallic compounds and the thermodynamic properties of the hydrides formed from those compounds. J Less Common Met. 1977, 56, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Cao, Z.; Xiao, X.; Zhan, L.; Li, S.; Li, Z.; Jiang, L.; Chen, L. Development of Ti-Zr-Mn-Cr-V based alloys for high-density hydrogen storage. J. Alloy. Compd. 2021, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wu, E.; Wang, S. Hydrogen storage properties of Laves phase Ti1−xZrx(Mn0.5Cr0.5)2 alloys. Rare Met. 2006, 25, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Faisal, M.; Lee, S.-I.; Jung, J.Y.; Kim, H.-J.; Hong, J.; Lee, Y.-S.; Shim, J.-H.; Cho, Y.W.; Kim, D.H.; et al. Activation of Ti–Fe–Cr alloys containing identical AB2 fractions. J Alloys Compd. 2021, 864, 158876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotov, T.; Sivov, R.; Movlaev, E.; Mitrokhin, S.; Verbetsky, V. IMC hydrides with high hydrogen dissociation pressure. J. Alloy. Compd. 2011, 509, S839–S843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).