1. Introduction

Recently, the announcement of President Donald Trump on trade tariff policies, the so-called “reciprocal tariff” based on bilateral negotiations, has pushed markets and commodities beyond equilibrium, and is intended to use tariffs not as weapons in a global context but to restrain competition, and the rising Southeast Asian economies[

1]. This policy has been narrowed to the imports from the region and could have economic and political turbulence for Southeast Asian economies. Its impact may include diversifying trade partners, supply chain reconfiguration, fractured ASEAN unity, and vulnerability of countries like Laos and Myanmar. The closest effect may likely come from the

shifting goalposts of renewable energy transitions of the vulnerable countries, as transitions require structural transformation of the traditional energy to new energy and come with economic cost. The primary tools for mitigating the effects of climate change are energy transitions, which aim to enhance the resilience, sustainability, and productivity of a country's energy system. When estimating energy transition pathways, each country and region has its own unique set of circumstances. Hence, addressing a research topic on the economic growth effects on energy transitions should provide a significant academic debate.

Although Southeast Asian economies do, however, face similar opportunities and difficulties. A misalignment of resources and energy demand also contributes to the region's underdeveloped potential for renewable energy. Since the entire region has abundant renewable energy resources, the development of regional energy connections suggests a significant institutional advantage to further decarbonize the Southeast Asian energy sector beyond the efforts of individual countries. In terms of energy mix, Southeast Asia has achieved some early success in developing renewable energy sources, accompanied by advancements in energy efficiency. Despite its controversies, renewable energy has advanced significantly and continues to grow throughout Southeast Asia. Li et al. [

2] affirmed the advancement of energy transition in Southeast Asia. Derouez, and Ifa [

3] found that countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, Japan, and South Korea, CO2 emissions are mostly driven by GDP and non-renewable energy usage. However, mostly due to historical difficulties, the growth threshold in the energy mix has not been adequately addressed. In this article, the primary objective of the study is to investigate the growth threshold effect on clean energy access and renewable energy transition in Southeast Asia.

The contribution of the study to existing literature is as follows: (1) We delve into the impact of import restrained and respond to the Trump announcement of the so-called reciprocal tariffs on the Southeast Asian countries along the pursuit of renewable energy transitions. (2) We investigate information asymmetry using the known dynamic panel threshold regression. (3) We also utilized the interaction model to explore the moderating effect of economic growth in the nexus between access to clean energy innovation and renewable energy transition in Southeast Asian countries. In light of the relationship between clean energy access and the transition to renewable energy in Southeast Asian economies, it is important to note that the current study differs from earlier studies in terms of viewpoints, perspectives, periodicity, and methodologies. The impact of information asymmetry in the relationship between clean energy access and the transition to renewable energy has not received the thorough scholarly attention it merits and has not been extensively covered in the literature; therefore, the topic is still up for debate. The aim is to examine the asymmetric/threshold effect of growth on the relationship between clean energy access and the transition to renewable energy in Southeast Asian nations.

The paper is organized and is divided into six sections. The theoretical support and presented in

Section 2, the research methodology and data sources are described in

Section 3, the results are shown in

Section 4, our findings are discussed in

Section 5, and the conclusions and policy implications are presented in

Section 6. Next, the theoretical underpinning and the hypothesis development supporting the findings of this article are presented in the forthcoming section.

2. Snippet of the Theoretical Underpinnings and Hypotheses Development

Abdulqadir [

4] uncovered the impact of growth on the nexus between renewable energy consumption and energy intensity in major oil-producing sub-Saharan African SSA countries. Wang et al.[

5] discovered a non-linear correlation between the development of renewable energy and the ODA, suggesting the existence of a threshold effect using the SSA countries' panel data from 2005 to 2015. Further, ODA would encourage the growth of renewable energy when urbanization and carbon dioxide intensity are below the threshold values.

2.1. Growth and the Global Renewable Energy Transition

Chen et al.[

6] found evidence that if and only if developing or non-OECD nations cross a specific threshold of renewable energy consumption, the impact of renewable energy consumption on economic growth is positive and significant. However, the use of renewable energy has a detrimental impact on economic growth if it falls below a certain threshold in developing nations. However, we also discovered that the use of renewable energy has a favourable and large impact on economic growth in OECD countries, while it has no discernible influence on economic growth in developed nations. Imran et al. [

7] discovered significant evidence of energy transition, resource curse, and economic development in Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS) countries from 1991 to 2022. Triki et al. [

8] used time series analysis from 2002 to 2023 to uncover the link between renewable energy transition and long-term development in the Ha'il region. Raihan et al. [

9] conducted a time series study from 1970 to 2022 to reveal the impact of FDI and globalization on Mexico's renewable transition. Wang et al. [

10] investigated the impact of renewable energy, urbanization, and trade on CO2 emissions and economic growth in a sample of 122 nations from 1998 to 2018.

2.2. Growth and Renewable Energy Transition in Southeast Asia

Cong et al.[

11] discovered how the digital economy and sustainable elements—economic, social, and environmental—affect Southeast Asia's use of renewable energy transition between 2004 and 2021. This is to underline how crucial it is to the creation and transformation of sustainable green energy. Zhong et al. [

12] revealed many avenues through the strategic pursuit of cross-border transmission, carbon capture and sequestration, and renewable energy in ASEAN countries. [

13] discovered that using renewable energy has a favorable impact on economic growth, using China's data from 1990 to 2020. Renewable energy transition can also have an indirect impact on economic growth through trade openness, foreign direct investment, labor force participation, gross capital formation, and R&D spending. Guo and Yan [

14] discovered that heterogeneity analysis reveals the emission reduction effects of industrial upgrading intensify toward downstream regions, with energy transition being crucial for mid-upstream mitigation across YREB provinces from 2005 to 2021. Furthermore, a U-shaped relationship exists between industrial upgrading and both energy intensity and energy structure decarbonization, while it significantly lowers regional emissions.

On the contrary, Asisifa and Pratomo[

15] revealed that the greenhouse gas and renewable energy transition do not have a significant influence on the level of growth in Southeast Asian countries. Li et al. [

2] discovered that, primarily due to legacy difficulties, the dominance of coal in the energy mix has a mismatch between energy demand and available resources; the region's potential for renewable energy transition is similarly underdeveloped. On the other hand, in Southeast Asian nations, the relationship between clean energy access and the shift to renewable energy is impacted by economic growth. Regardless of whether this effect was seen or not, it would not give economists and policymakers the right policy tools until they suggested a turning point in the nexuses under investigation. Using a dynamic threshold regression technique, we have discovered a gap in the literature and substantial evidence of the existence of an inflection point along the nexus between clean energy access and renewable energy transition in Southeast Asian countries. The study offers the following testable hypotheses in support of the main study findings, taking into account the gap in the literature, as follows:

Hypothesis 1: The level of trade plays a moderating role in the nexus between access to clean energy, innovations, and the transition to renewable energy in Southeast Asian economies.

Hypothesis 2: The level of FDI does play a moderating role in the nexus between access to clean energy, innovations, and the transition to renewable energy in Southeast Asian economies.

Hypothesis 3: The level of R&D plays a moderating role in the nexus between access to clean energy, innovations, and the transition to renewable energy in Southeast Asian economies.

Hypothesis 4: The impact of economic growth on clean energy, innovations, and the transition to renewable energy in Southeast Asian economies may shift from positive to negative, or vice versa, when it falls below or above a particular threshold.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data

In this study, panel data from the World Bank Development Indicators (WDI) covering eight Southeast Asian countries (China, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam) for the period 2000-2023 are employed; Laos and Myanmar are excluded from the sample due to data unavailability. All of the variables are described in detail in Appendix Table A1.

3.1.1. Dependent Variable

Renewable energy consumption (transition). The study employs Renewable energy consumption as the share of renewable energy in total final energy consumption as a dependent variable. The choice of this variable was motivated by the literature [

13,

16,

17].

3.1.2. Independent Variable

Access to clean fuels and technologies for cooking (access). The choice of this variable was motivated by a gap in the literature.

3.1.3. Threshold Variable

Economic prosperity (economic growth), the study adopts an annual growth rate of gross domestic product constant 2015 as an indicator of economic growth. This variable is supported by the previous studies. [

18,

19,

20].

3.1.4. Control Variable

The specific control variables include foreign direct investment inflow share of GDP (FDI), trade openness (TOP), R&D expenditure share of GDP, and labor force participation rate. These variables are supported by the previous studies [

6,

13,

21,

22].

3.2. Methods

To explore the premise of the testable hypotheses, the study applied an interaction model approach by Brambor et al. [

23], and panel threshold analysis by Hansen [

24], to investigate the growth threshold effect on renewable transition for Southeast Asian countries over the period 2000-2023. The study utilized panel data with a model specified as follows.

where t denotes year;

denotes constant; [

,

] denote estimated coefficients; and

random term.

Introducing the threshold investigation in the pertinent model above, we employ the threshold effect test following the approach in Hansen [

15,

16,

24].

where

denotes constant; [

,

] denote estimated coefficients; and

random term.

Equally, the models (1-2) presented above are utilized as an empirical strategy modeling the nexuses between renewable energy transition in Southeast Asia. The next section will present the results from the above testable empirical models.

4. Results

This section will examine and provide the main conclusions drawn from the hypothesis, taking into account its structure and the models covered in the previous sections. To meet the statistical requirement, we first provide the initial data analysis. We next go on to explore the moderating effect of growth in the nexuses investigated. Third, the results of the threshold estimation and dynamic panel threshold effect test for the benchmark models are shown.

4.1. Preliminary Data Analysis

Table 1 Panel A,

Table 1 Panel A, shows the renewable energy transition and access to clean energy and technology in Southeast Asian countries. The trend presentation was strongly supported by their estimated means and standard deviations [3.241; 2.724] and [1.501; 1.549], respectively. Summarily, other variables also exhibit parallel trends as trade, R&D, labor, and FDI have mean and standard deviations [4.552; 2.878; 4.288, & 0.846] and [0.772; 1.950; 0.073, & 1.296], respectively.

Table 1, Panel B, the pairwise correlation test results revealed a positive and statistically significant correlation with access to clean energy and technology, while a negative and significant correlation between transition, trade, and FDI, respectively.

4.2. Endogeneity Test

In order to thoroughly investigate the potential endogeneity issues that may arise between access and the shift to renewable energy, this study has chosen to use an instrumental variable method. The information in

Table 2 shows that (L.access), the instrumental variable of choice, is appropriate and effective. The expected value of access (accesshat) continues to show a strong positive link with the shift to renewable energy, according to the results of the second stage. According to this research, continued access to clean energy and technology continuously raises the regional level of the renewable energy transition, even after carefully accounting for the intricate endogeneity considerations.

4.2. Moderating Effects Analysis

As presented in

Table 3, column 1, the coefficients of access to clean energy and innovation, and R&D display a significant positive coefficient at a 1% level, suggesting that these variables contribute to advancing the renewable energy transition. However, the coefficient of the interaction term (Growth×FDI) presented in column 2 is [0.152] and positive, statistically significant at the 10% level. This estimate revealed that the level of FDI inflow has a significant moderating effect on access to clean energy and the renewable energy transition, thus validating the correctness of Hypothesis 1.

Similarly, the coefficient of the interaction term (Growth × trade) presented in column 3 is [0.227] and is positive and statistically significant at the 5% level. This finding indicates that trade has a significant moderating effect on access to clean energy and the renewable energy transition, thereby validating Hypothesis 2. Furthermore, the coefficient of the interaction term (Growth × R&D) presented in column 4 is [-0.281] and is statistically significant at 1% level. This showed that the role of R&D plays a significant moderating effect on access to clean energy and the renewable energy transition, validating Hypothesis 3.

4.3. Threshold Effect Test and Estimations

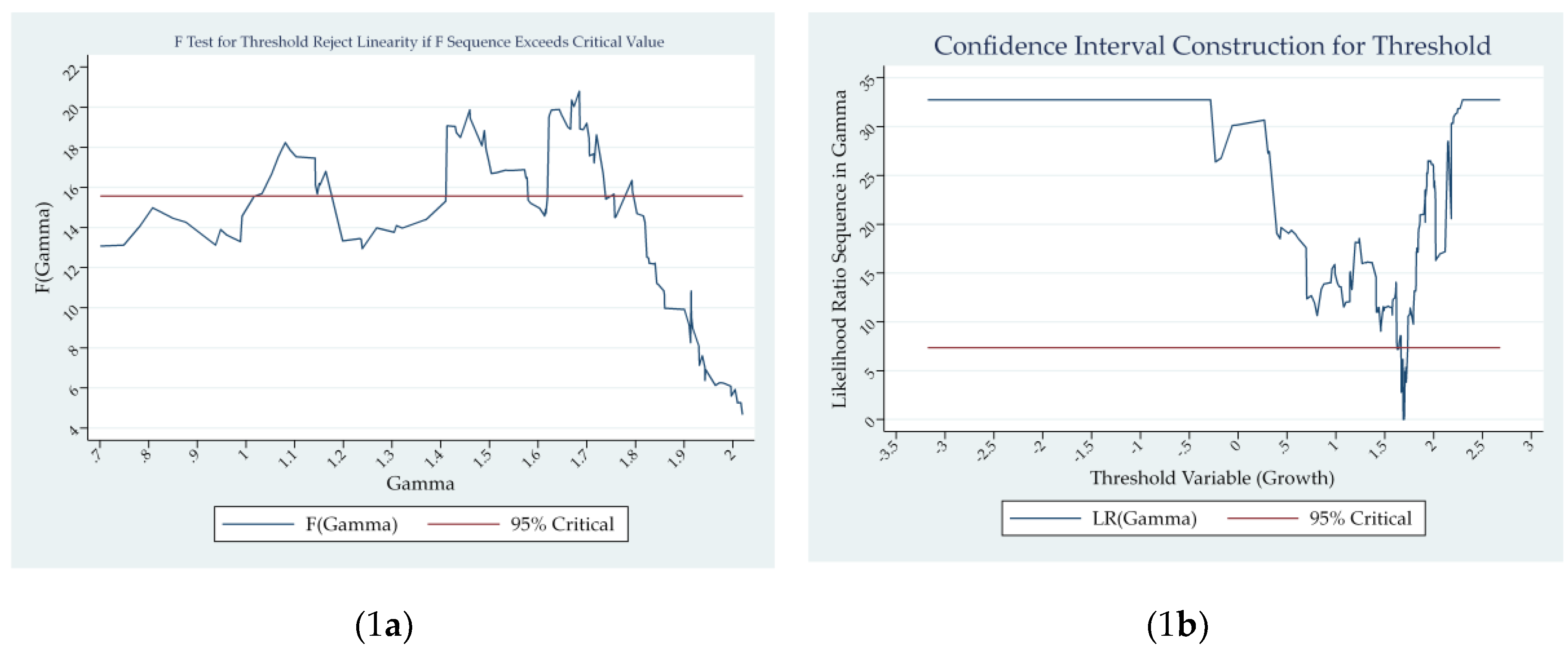

As presented in

Table 4, the results of both the threshold effect test and threshold estimation are disclosed. The threshold effect test for the level of the growth variable is presented. It is observed that there is strong evidence of a significant growth threshold effect [Growth=1.68%] on the nexus between access to clean energy and the renewable energy transition, respectively.

Considering the level of economic growth as a threshold variable, and its impact on the level of access to clean energy can either be negative or positive on the renewable energy transition. The result from the threshold effect test revealed the existence of a significant threshold estimate of [Growth=1.68%].

Table 4 above presents the threshold impact estimations of the variables at regime 1 (Below the threshold) and regime 2 (Above the threshold), respectively. Below the threshold, the impact of growth on access to clean energy and renewable energy transition on Southeast Asian countries is positive 0.548 and statistically significant at 1% level, and the impact further declines to a positive 0.209 above the threshold and statistically significant at 1% level.

Figure 1 presents a diagrammatic portrayal of the asymptotic critical values construction for the estimated threshold. The process is utilized to establish the consistency in the investigation of the true estimates for the best fit.

5. Discussion

In this section, the major findings of this article are discussed. Using the jointly interaction term and dynamic panel threshold regression approach to investigate the nexus between access to clean energy and technology and the transition to renewable energy in Southeast Asian countries. The corroborated findings from the endogeneity test and the significant impact of the moderating effect of growth/FDI (Growth×FDI) on the nexus between access to clean energy and the renewable energy transition in Southeast Asian countries. Consequently, Hypothesis 1 is confirmed.

Second, the finding also revealed the statistically significant impact of the moderating effect of growth/trade (Growth×trade) on the nexus between access to clean energy and the renewable energy transition in Southeast Asian countries, which corroborated the findings from the endogeneity test. Consequently, Hypothesis 2 is confirmed.

Third, the findings also discovered the statistically significant effect of moderating effect of growth/R&D (Growth×R&D) on the nexus between access to clean energy and the renewable energy transition in Southeast Asian countries, which corroborated the findings from the endogeneity test. Consequently, Hypothesis 3 is confirmed.

When the growth critical threshold is below 1.68% the impact of the estimated coefficient of access to clean energy is 0.548, and the effect on renewable energy transition in Southeast Asia is positive and statistically significant at the 1% level. However, when this critical level of growth threshold exceeds 1.68%, the impact of the estimated coefficient of access to clean energy and transition in Southeast Asian countries declines to 0.209, and is statistically significant at a 1% level. Consequently, Hypothesis 4 is confirmed.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, this article investigates the growth threshold on access to clean energy and renewable energy covering eight Southeast Asian countries, including China, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam for the period 2000-2023. Using panel data and the threshold regression analysis as an empirical strategy, we have found overwhelming evidence to support and respond to the fundamental testable research hypotheses in this article.

To achieve SDG-7 in the pursuit of affordable and access to clean energy in Southeast Asian countries, through transition to renewable energy often results not without certain economic cost implications. Rarely, an enhanced transition to renewable energy may likely result in a negative impact on these economies when some fundamental growth indicators are below a certain threshold, as predicted from the outcome of this article.

The policy implications of accelerated transition to renewable energy, promoting sustained growth, at least below certain thresholds. Considering the findings from this article, we believe that promoting investment in R&D, trade, and FDI would have a positive impact on the region in the long run. In the short run, revisiting some of the existing policies could possibly distort the optimal allocation of resources to achieve its desired SDG-7 trajectory before the deadline, 2030.

Future research direction should focus on other fundamental factors that could likely promote sustained transition to renewable energy transformation. Given considerable concern on exploring the asymmetric impact of economic growth in the nexus between access to clean energy and renewable energy transition in Southeast Asian countries, beyond will be a significant topic for future research. 6. Patents

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.A.A. and M.M.; methodology, I.A.A.; software, I.A.A.; validation, I.A.A. and M.M.; investigation, I.A.A.; resources, M.M.; data curation, I.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, I.A.A.; writing—review and editing, M.M.; visualization, I.A.A.; supervision, M.M.; project administration, I.A.A.; funding acquisition, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the projects of talent recruitment of GDUPT under the Grant no XJ2022000901.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support provided by the projects of talent recruitment of GDUPT under Grant Number XJ2022000901

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASEAN |

Association of Southeast Asian Nations |

| SSA |

Sub-Saharan Africa |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goal |

| R&D |

Research and Development |

| FDI |

Foreign direct investment |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Data definition and source.

Table A1.

Data definition and source.

| Variables |

Symbols |

Definition |

Source |

| Renewable energy |

transitions |

Renewable energy consumption is the share of renewable energy in total final energy consumption. |

WDI |

| Economic growth |

growth |

Annual % growth rate of GDP constant 2015 |

WDI |

| Access to clean energy |

access |

Access to clean fuels and technologies for cooking (% of population) |

WDI |

| Trade openness |

trade |

Trade (% of GDP) |

WDI |

| Foreign direct investment |

fdi |

Net inflows (% of GDP) |

WDI |

| Research and development expenditure |

r&d |

Research and development expenditure (% of GDP) |

WDI |

| Labor force |

labor |

Labor force participation rate, total (% of total population ages 15–64) |

WDI |

References

- S. S. Regilme, “Oligarchic rivalry: US–China tariffs and the global politics of inequality,” 2025.

- B. Li, V. Nian, X. Shi, H. Li, and A. Boey, “Perspectives of energy transitions in East and Southeast Asia,” WIREs Energy Environ., vol. 9, no. 1, p. e364, Jan. 2020.

- F. Derouez and A. Ifa, “Assessing the Sustainability of Southeast Asia’s Energy Transition: A Comparative Analysis,” Energies, vol. 18, no. 2, 2025.

- A. Abdulqadir, “Growth threshold-effect on renewable energy consumption in major oil-producing countries in sub-Saharan Africa: a dynamic panel threshold regression estimation,” Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag., vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 496–522, 2021.

- Q. Wang, J. Q. Wang, J. Guo, and Z. Dong, “The positive impact of official development assistance (ODA) on renewable energy development: Evidence from 34 Sub-Saharan Africa Countries,” Sustain. Prod. Consum., vol. 28, pp. 532–542, 2021.

- C. Chen, M. C. Chen, M. Pinar, and T. Stengos, “Renewable energy consumption and economic growth nexus: Evidence from a threshold model,” Energy Policy, vol. 139, no. December 2019, p. 111295, 2020.

- M. Imran, M. S. Alam, Z. Jijian, I. Ozturk, S. Wahab, and M. Doğan, “From resource curse to green growth: Exploring the role of energy utilization and natural resource abundance in economic development,” Nat. Resour. Forum, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 2025–2047, May 2025.

- R. Triki, S. M. Mahmoud, Y. Bahou, and M. M. Boudabous, “Assessing Renewable Energy Adoption to Achieve Sustainable Development Goals in Ha’il Region,” Sustain., vol. 17, no. 13, pp. 1–15, 2025.

- Raihan; et al. , “Dynamic effects of foreign direct investment, globalization, economic growth, and energy consumption on carbon emissions in Mexico: An ARDL approach,” Innov. Green Dev., vol. 4, no. 2, p. 100207, 2025.

- Q. Wang, C. Li, and R. Li, “How does renewable energy consumption and trade openness affect economic growth and carbon emissions? International evidence of 122 countries,” Energy \& Environ., vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 187–211, 2025.

- N. T. Cong, H. T. Truc, N. M. Nhut, and T. T. Ngoc, The Role of the Digital Economy and Sustainable Factors: Economic, Social, Environmental in Renewable Energy Consumption in Southeast Asia, vol. 2. Springer Nature Switzerland, 2025.

- S. Zhong, L. Yang, D. J. Papageorgiou, B. Su, T. S. Ng, and S. Abubakar, “Accelerating ASEAN’s energy transition in the power sector through cross-border transmission and a net-zero 2050 view,” iScience, vol. 28, no. 1, p. 111547, 2025.

- Y. He and P. Huang, “Exploring the Forms of the Economic Effects of Renewable Energy Consumption: Evidence from China,” Sustain., vol. 14, no. 13, pp. 1–16, 2022.

- S. Guo and X. Yan, “Investigation of Industrial Structure Upgrading, Energy Consumption Transition, and Carbon Emissions: Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt in China,” Sustain., vol. 17, no. 10, 2025.

- M. Asisifa and W. A. Pratomo, “Analysis of the Impact of Green Economy on Economic Growth in ASEAN Countries,” in TALENTA Conference Series: Local Wisdom, Social, and Arts, 2025, vol. 8, no. 1.

- S. Han, D. S. Han, D. Peng, Y. Guo, M. U. Aslam, and R. Xu, “Harnessing technological innovation and renewable energy and their impact on environmental pollution in G-20 countries,” Sci. Rep., vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1–16, 2025.

- X. Shi and D. Shi, “Impact of Green Finance on Renewable Energy Technology Innovation: Empirical Evidence from China,” Sustain., vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 1–19, 2025.

- J. Wang, Z. Tan, and Y. Zuo, “Digital inclusive finance and common prosperity: The threshold effect based on rural revitalization,” Int. Rev. Econ. Financ., vol. 100, no. March, pp. 1–9, 2025.

- C. Wen, Y. Xiao, and B. Hu, “Digital financial inclusion, industrial structure and urban–Rural income disparity: Evidence from Zhejiang Province, China,” PLoS One, vol. 19, no. 6 June, pp. 1–24, 2024.

- Y. Zhang, K. Li, Y. Pang, and P. C. Coyte, “The role of digital financial inclusion in China on urban—rural disparities in healthcare expenditures,” Front. Public Heal., vol. 12, no. August, 2024.

- S. Wu et al., “The Effect of Labor Reallocation and Economic Growth in China,” Sustain., vol. 14, no. 7, 2022.

- S. Qi and Y. Li, “Threshold effects of renewable energy consumption on economic growth under energy transformation,” Chinese J. Popul. Resour. Environ., vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 312–321, 2017.

- T. Brambor, W. R. Clark, and M. Golder, “Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses,” Polit. Anal., vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 63–82, 2006.

- B. Hansen, “Sample Splitting and Threshold Estimation,” Econometrica, vol. 68, no. 3, pp. 575–603, 2000.

- A. Abdulqadir, “CO2 emissions policy thresholds for renewable energy consumption on economic growth in OPEC member countries,” Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag., vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 1074–1091, 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).