1. Introduction

In the context of growing environmental concerns and material scarcity, the reuse and recycling of wood waste have gained increasing attention in the construction industry. With wood remaining one of the most widely used renewable resources, efforts to repurpose its by-products into high-performance materials contribute directly to sustainable building practices, lifecycle performance, and circular economy goals. Traditional timber, while structurally valuable, is vulnerable to fire hazards and moisture-related degradation, making it less suitable for demanding applications without further modification. Research has recently begun to diverge from the use of composite (resin-bound) panels from recycled wood, utilizing coatings with fire retardant and hydrophobic binders to increase safety and durability. This study follows that trajectory by assessing the composite panels made from granulated recycled wood and intumescent fireproof coatings and epoxy resin according to their composite water absorption, capillary movement of water through the material, and a fire resistance evaluation of burning performance for four species of wood: pine, beech, oak, and olive. Olive wood is considered among the most widespread tree species in Albania, as it occurs abundantly in the local environment and is readily available in nature, often in the form of degraded wood. The integration of these panels into ventilated façade systems is largely influenced by the increasing demand for environmentally sustainable buildings. Their use not only responds to market preferences for ecological construction but also contributes to reducing production costs while remaining adaptable to the specific requirements of the local context.

In particular, wood is one of the most popular construction materials across various industries due to its natural, visual finish and its durability of high structural strength. Its interactions with both water and fire are arguably one of the more prominent phenomena that contributes to structural performance.

Overall, converting industrial waste wood into functional panels is advantageous as it fulfills both the environmental and resource recovery aspects of sustainability. An extensive review by Amarasinghe et al. (2024) has also suggested that adding 10–30 % reclaimed wood into new composite panels will improve the humidity control and dimensional stability of the composite panels, despite the variance in physical properties of recycled wood from its heterogeneous sources. The authors suggest the requisite standards of delivering consistent panel quality, sorting process and means of performing uniformity testing of the new products, inform performance reliability, which are critical points for any recycled wood composite use in façade or insulation applications [

1].

Understanding the water absorption and retention rates of wood species is critical in material selection for construction, furniture and the design industry. Another study examined and compared four of Albania's commonly used wood species; fir, pine, beech, & oak, according to their moisture retention characteristics and water movement properties. By immersing wood samples in water for periods of 12, 24, 36, & 72 hours either partially or fully immersed in the water, the research identified how each of the species acted when wet for an extended period of time. The results indicated that the denser woods from the study (beech & oak) both retained moisture (amount retained) and absorbed more moisture whereas fir and pine, retained less moisture content compared to beech & oak, but had higher capillary activity. All these results provide useful information to architects, engineers and designers who need to make decisions and enforce project design stipulations in difficult / humid environments, where moisture resistance and dimensional stability are important for longevity of products [

2].

In regards to fire resistance, Zhao et al. (2023) created a wood/polyimide composite aerogel that had a well-preserved pore hierarchy and intact strong hydrogen bonds. As a result, this developed aforementioned material had superior flame-retardant properties, possessed low water absorption, and good mechanical performance. Contrarily to traditional wood composites, this aerogel was measured with very high hydrophobicity and a measured good thermal performance, which could be an interesting model when creating recycled wood panels that require fire resistance while maintaining moisture equilibrium [

3].

Recent surveys are starting to investigate waste-enhanced particleboards. For example, Mancel et al. (2022) studied boards with rubber waste at up to 20 % (from shredded tires). Their fire testing showed that they had similar ignition temperatures and burning rates to normal particleboards suggesting that at least for mixed waste, fire parameters could still be maintained. If this process is explored and additives for moisture impermeability are considered, there is the potential to create recycled wood composite panels that can meet the benchmark fire and water parameters [

4].

Conversely, understanding how construction materials may interact with moisture is vital to the longevity of the structure in any climate, but especially in one like Tirana, Albania. In a different study, the water absorption, capillarity action and material composition of five building-envelope materials: silicate brick, red-clay brick, hollow clay brick, concrete block, and EPS fiber–cement composite panels, were assessed. Initial samples were oven dried and then half-submerged in water for 12, 24, and 36 hours respectively. Following each submersion, samples were then air dried indoors in the same length of time according to the individual time interval specific to each sample subsumed under water. The moisture content was assessed at each drying stage and capillary uptake testing was evaluated to better represent water transport through given building material. Results indicated that red-clay and hollow clay brick showed highest levels of water absorption and capillarity action respectively, indicating they would be less acceptable as surface materials essentially exposed outdoors without secondary moisture protection. This was very useful information to architects and engineers who are specifying these materials in similar climates [

5].

Adhikary, Pang, and Staiger (2008) explored long-term moisture uptake and dimensional changes in wood–plastic composites made of recycled plastics and wood waste (sawdust) from Pinus radiata. The authors created test panels using virgin and recycled polyolefins with various compositions of wood fiber and in some cases used malleated polypropylene as a coupling agent. In a long-term water immersion test, it was observed that with moisture absorption and thickness swelling increased over time until reaching an equilibrium state. There was a positive correlation between wood content, moisture uptake, and thickness swelling. However, the impact of the addition of the coupling agent on moisture and thickness was significantly lower as described. The study provides clear information on how coupling agents improve water absorption resistance and dimensional stability for purposes of designing recycled wood composite panels [

6].

In the publication by Zhang et al. (2022), borated wood flour is embedded into a polycarbonate matrix to produce bio composites. The bio composites described, have better fire-retardant ability, longer ignition times, and lower peak heat release rates, that also were noted to have higher levels of water absorption as increased wood content suggested a vital trade-off when combining both fire safety and moisture resistance [

7].

Kouadio and his colleagues, (2020) researched wood-waste composites with expandable polystyrene (EPSs) and mineral fillers to examine mechanical strength and fire behavior. The authors reported better fire behavior and strength with the mineral fillers that provided thermal shielding. Capillarity was not measured directly, but water absorption was significantly decreased, so it was concluded that inclusion of fillers could restrict moisture transfer in recycled wood panels [

8].

Ramesh et al. (2022) provided a synthesis of the latest developments in wood-based polymer composites (WPCs) in a recent and exhaustive review. WPCs have environmental benefits and a variety of applications. WPCs are manufactured with renewable resources; they are produced through blending recycled wood flour with polymers; additional physical properties related to mechanical performance, dimensional stability, and environmental impacts can be achieved with WPCs compared to traditional wood composites. The study looked at processing methods such as extrusion and injection molding, methods for component compatibility using bio-based adhesives (e.g. lignin, tannin) and coupling agents, and how additions of flame retardants and mineral fillers influence performance in WPCs as well as considerations such as thermal behavior and rheology, and life-cycle assessment outcomes to demonstrate performance advantages for WPCs, including for potential uses in sustainable construction, automotive, and marine applications. In conclusion, the authors' evidence supports that optimizing formulations and using green adhesives will provide high-performance, sustainable composites that respect circular-economy principles [

9].

Özdemir and Mengeloğlu (2008) researched the development of composite panels from recycling HDPE (from old pipes) with eucalyptus wood flour and compared the performance of a mixture with a maleic anhydride grafted polyethylene (MAPE) coupling agent with one without under water exposure and wear on the surface. They found that the addition of MAPE substantially improved surface smoothness with significant reductions in water absorption and thickness swelling during immersion tests. Also, coatings of cellulosic varnish or polyurethane lacquer improved adhesive strength, away resistance, scratch resistance, and gloss, particularly the case with polyurethane coatings. Microscopy showed better adhesion at the wood-polymer interface due to the coupling agent, which made the panels more water-resistant and mechanically strong [

10].

In their insightful article, the authors Khan, Mishra, Thakur, and Pappu (2025) provide a futures perspective on sustainable wood–plastic composites (WPCs) by investigating the implications of different thermoplastic matrices such as PP, HDPE, LDPE, PVC, and PS and their interaction with wood flour that will affect material properties. In the article, they also review production processes including extrusion, injection, molding, compression, and additive manufacturing and highlight how processing decisions affect mechanical stiffness, moisture resistance, and biodegradability. The article identifies key innovations like fiber esterification, particle-size optimization, thermal pretreatment, coupling agents, and the use of nano-fillers that boost hydrophobic compatibility, thermal stability, and structural integrity. Ultimately, the authors argue that combining green processing with value-added composites paves the way for WPCs that meet sustainability and performance demands in modern infrastructure, packaging, automotive, and construction markets [

11].

Another study, elaborated by Schirp and colleagues (2021), examined how pre-treating wood particles with phosphorus–nitrogen fire retardants improves both the flame resistance and moisture behavior of WPCs intended for façade applications. They demonstrated that HDPE-based composites containing fire-retardant-treated wood flour achieved UL94 V0 ratings and LOI values above 29 %, levels typically unachievable with untreated wood flour. Their findings further revealed that the treated wood not only enhanced fire performance but also reduced water uptake and swelling, likely due to esterification effects from the phosphorus compounds interacting with wood surface hydroxyls. The research findings show that the combination of wood pre-treatment prior to application of FR additives offers the dual benefit of enhancing moisture barrier properties and burn resistance and is, therefore, very promising for ventilated facades in sustainable building construction [

12].

The emergent needs for protected and sustainable fire prevention in wood applications have engendered significant advances in surface treatment methods. Wang et al. study in 2021 is a simplistic fire-retardant coating utilizing polysilicate, with boric acid, and is still effective with a water formulated coating compared to halogenated systems. This application showed good performance compared to traditional halogenated systems in terms of flammability with limited effect on the aesthetic and mechanical characteristics of the wood. The coating provided ignition delay, char depth, and thermal stability all of which contribute to structural safety and environmental parameters. This research has potential for pursuing environmentally conscious material engineering [

13].

To evaluate the potential of wood-plastics composites (WPC) in enhancing mechanical properties, Divya et al. (2018) investigated wood content and compatibilizers on tensile properties of WPC panels with various amounts of teak wood flour combined with polypropylene (PP) and high-density polyethylene (HDPE) using MAPP as a compatibilizer. Composite panels were formed from the viable combinations of raw materials and WPCs that were produced from both extrusion and injection molded methods. The results indicated a clear compromise of tensile strength. Scanning electron microscopy displays the bonded regions of modified WPC, demonstrating an improved interface and adhesion strength by using a compatibilizer that provides a balance in mechanical properties [

14].

The present research is directly connected to the Strategic Sectoral Priorities contributing to the Circular Economy, as well as, sustainable development, waste management and the more efficient use of natural resources. For the construction sector, we are working to promote recycled and ecological materials, promoting the potential uses of waste, allowing for reduced dependence on new wood, reducing pressures on already threatened mains and secondary forests. The research supports the sectoral priorities for improving urban waste management examples include our work with reintroducing waste from the aforementioned material into sustainable composite materials, which can be produced for construction, such as ventilated facades. This work falls squarely in support of the goals for green transition and innovation in the construction materials sector while maintaining and promoting circular economy sustainability with regards to increased value to the environment and society.

This study aims to contribute to sustainable development and the green transition through the recycling of wood waste and the creation of innovative composite materials, which will be used for ventilated facades. The main goal is to minimize urban waste and reduce environmental impact by transforming wood waste into functional and ecological products. Through detailed experiments on moisture absorption, capillarity, and performance of materials under different conditions, fire resistance, and testing on the durability of materials, the study aims to create reliable and cost-effective solutions for the construction sector. At the same time, it aspires to promote the use of advanced technologies and scientific methodologies to improve the understanding and application of recycled materials in industry, thus supporting the management of natural resources and the conservation of biodiversity.

The project brings important contributions to applied and fundamental sciences by advancing knowledge on the recycling and use of composite materials in construction. In fundamental sciences, it helps to understand the mechanisms of moisture absorption by recycled materials, especially for wood-resin combinations, adding knowledge on their physical and chemical behavior. In applied sciences, the study offers practical solutions for the use of wood waste in the creation of panels for ventilated facades, promoting the development of new technologies in recycling and sustainable construction. This approach directly impacts improving material and environmental efficiency standards, serving as a model for other industrial applications in a global and local context.

On the other hand, in order to guarantee both the sustainability of its built environment and the safety of its residents, the European Union places a high priority on fire safety. Incorporating fire safety within the EU's sustainability policies and metrics would help guarantee that sufficient funds are set aside for fire safety and that the EU can effectively address possible fire-related risks. Ensuring that fire safety is taken into account when developing new infrastructure projects and that existing infrastructure is maintained in good condition may also be achieved by including fire safety into the EU's sustainability policies and indicators [

15].

Recycling of materials, and especially wood waste, is a major issue in sustainable development and urban waste management. Having this waste accumulated in urban areas affects not only the image and cleanliness of cities but also contributes to contamination to the environment and depletion of valuable natural resources. In parallel, construction demand for wood leads to intensified exploitation of forests, which causes further negative impacts on biodiversity and ecosystems. Finding a solution to the problem of disposal by recycling and using composite materials specifically, recycling wood panels as take back and applying to ventilated facades offers a much better solution than just disposing of wood waste. This improves environmental conditions and waste disposal, typically lowers construction costs, encourages the use of ecological materials, contributes to a green transition and helps conserve natural resources.

2. Characterization of Wood Species

The effectiveness of wood composites with regards to water absorption, capillary behavior, and fire resistance is inherently tied to the anatomical and chemical characteristics of the source material. Therefore, this study included a selection of four wood species widely available in the Mediterranean region: pine (Pinus sylvestris), beech (Fagus sylvatica), oak (Quercus robur), and olive (Olea europaea). Pine is a softwood with a lower density than hardwood species, a higher content of resin, and an open cellular structure that grants it rapid capillary movement of fluids, due to longitudinally aligned tracheids filled only sparsely with extractives. The porous nature of pine means that it also absorbs water quickly, along with the increased potential of deforming unless treated. Beech is a hardwood that is quite dense, uniform in texture and very fine in pore structure. It has a considerably more compact fiber structure allowing for some water penetration but retains water once it does get absorbed, in addition, its high density also will provide some moderate fire resistance but the coating must be maintained in order to minimize flammability.

Oak is a hardwood; characterized by a comparatively high amount of tannins, as well as visible medullary rays. Furthermore, it is quite resistant to fungal attack, while also demonstrating moderate moisture uptake. Oak can be helpful in preventing or reducing capillary rise, owing to its relatively tight grain, and effectively lower porosity; hence this species exhibits dimensional stability in humid environments.

Olive is an oily hardwood that is very dense structurally. It is considered a lesser material for construction, due to its rarity, however it is often sought out for its unique grain and its density compared to other woods. Olive's anatomical structure includes very divisible irregular vessels and high extractive contents; extractives may display some degree of natural resistance to fire, while also offering some water repellent properties. However, its density can make it brittle under thermal stress. Olive wood typically contains a higher natural oil content compared to woods like pine, beech, and oak, including natural oils and resins. These compounds contribute to its natural durability, water repellency, and distinct color and grain. Pine contains resinous substances (like turpentine), but the overall oil/extractive content is generally lower than olive wood. On the other hand, beech and oak have lower oil content; oak contains tannins and other extractives that offer durability but not necessarily oils in the same quantity as olive wood. Beech is relatively low in extractives and oil content [

16].

Each species presents a unique balance of advantages and trade-offs for use in composite panel fabrication. Their structural behavior under moisture exposure and fire conditions was a central focus of this study, and their performance characteristics were evaluated both before and after treatment with intumescent paint and epoxy resin.

However, once wood is granulated (i.e., turned into chips, flakes, sawdust, or powder), its natural anatomical structure is disrupted, which leads to the loss or reduction of many of its original mechanical, capillary, and fire-resistance characteristics.

Generally, natural wood absorbs and transports water through structured pathways (vessels, tracheids, fibers). Meanwhile, granulated wood loses this continuous structure. As a result, the capillary action is drastically reduced since there are no longer longitudinal channels. Water absorption becomes more about surface exposure of particles and porosity of the matrix, rather than internal transport, and the composite’s moisture behavior becomes dependent on the binder (e.g., epoxy or resin), particle size, and how well it's compacted. Furthermore, granulated wood has much lower capillarity, but can absorb water more quickly on the surface if not sealed properly [

6].

On the other hand, solid woods like oak or olive offer natural fire resistance due to density, extractives (like tannins or oils), and slower burning rates. Meanwhile, granulated wood, especially in composite form, burns faster if not treated, due to increased surface area and exposure of cellulose, is less fire-resistant unless intumescent agents, fire-retardants, or protective coatings (like intumescent paint or epoxy) are added, and natural fire-resistant traits are diluted once wood is ground and mixed with polymers or binders. As a conclusion, the natural fire resistance is significantly reduced unless you chemically compensate for it in the composite [

4].

Regarding the mechanical strength and durability, granulation weakens structural integrity, and the fibrous strength of solid wood no longer exists. Strength now depends on binder type and ratio (e.g., epoxy, HDPE), particle size and orientation, and compaction and curing methods. Composite panels can be strong, but not because of the wood alone; rather, due to engineering and chemical enhancements [

7].

Table 1.

Comparison of Natural and Granulated Wood Properties.

Table 1.

Comparison of Natural and Granulated Wood Properties.

Wood Type

|

Original Capillary Action |

Original Fire Resistance |

Granulated Capillarity |

Granulated Fire Resistance |

Notes |

| Pine |

High (due to open tracheids) |

Low |

Low |

Very Low (unless treated) |

Highly porous, fast moisture uptake |

|

Highly porous, fast moisture uptake |

| |

| Highly porous, fast moisture uptake |

| Beech |

Moderate |

|

Moderate |

Moderate |

Very Low |

Low |

Dense wood retains water. |

|

Dense wood retains water. |

| |

| Moderate |

| |

| Dense wood retains water. |

| Oak |

Low |

Moderate to High |

Very Low |

Low to Moderate (if treated) |

Tannin-rich, naturally decay-resistant. |

| Olive |

Very Low |

Moderate (due to oils) |

Minimal |

Moderate (can self-char) |

Oily content affects combustion. |

3. Materials and Methods

This study considers the use of wood panels, applicable to ventilated facades. Initially, the main materials collected, such as degraded natural wood, as seen in

Figure 1 (a), were granulated through a wood granulation device (Polis University Laboratory), as seen in

Figure 2 (a), and the material was left to dry at a controlled room temperature for about 2 weeks. Once the appropriate level of granulation is reached, as seen in

Figure 1(b), the extract was mixed with epoxy-based resins, as seen in

Figure 1(c, d). Each type of granulated wood is mixed with 500ml of epoxy-based resin. Afterwards, “intumescent” fire-resistant paint was applied to the samples after drying in order to measure fire resistance capacities for each of them.

Composite panels were produced as a result of mixing the granulated wood and adding epoxide resin. It is important to note that 4 different types of wood were used, such as pine, beech, oak, and olive. These types of wood are very popular in the Albanian context and in the Mediterranean area. The mixing process was carried out through a specific mixing device (Polis University Laboratory), as seen in

Figure 2 (b). After drying, the samples were coated with intumescent fire-resistant paint for subsequent testing.

Four samples (panels) measuring 25x25x2cm were produced and tested for moisture absorption using a hygrometer, as seen in

Figure 2 (d). The level of capillarity (movement of water through the pores of the material) was tested and measured, as well as their water absorption using the relevant formulas. The experiment also consists of immersing the samples in a container of water for up to 48 hours and then measuring and testing the water intake of the samples using a specific formula. The samples produced were tested as well by being partially immersed in water (up to 3cm), and their moisture content was measured with a specific device (hygrometer) over a period of 12 hours, 24 hours, 36 hours, 72 hours, and 120 hours. The moisture content was measured at the highest height of the water capillarity action. The capillarity action was measured as well. The same experiment was repeated with the same time frame for the drying period by taking the samples out of the water containers and letting them dry in a controlled environment. The fire resistance of the samples in the dry state was also tested. The results are presented in the form of graphs and tables using Microsoft Excel software in the experiment section. The experiment was held in a controlled environment. The mean temperature of the indoor environment during the entire experiment was approximately 28.1°C, and the mean relative humidity of the air was 42.3%.

3.1. Experiment Devices

The devices that were used in the experiment are as follows:

Wood Crushing Grinding Machine for Sawdust as seen in

Figure 2 (a). Raw material log, branch, wood waste. The final size of the particles is 3-5 mm.

Power Agitator with Support as seen in

Figure 2 (b). Mixer Type: Homogenizer Dispersion Blender Mixer. Max. Loading Volume (L)200 L. Application scope: High Viscosity Product. Power (kW)1.8 kW. Range of Spindle Speed (r.p.m) 1 - 1650 r.p.m.

Digital scale EV023 as seen in

Figure 2 (c). Measures in grams up to 15 kg. Margin of error 1 gram.

Inductive Moisture Meter Tester MS310-S for measuring moisture content of concrete, wood, paper, timber, bamboo, carton, and textile as seen in

Figure 2 (d). Measuring range :0-99%. Operating conditions: temperature:0-60°C, and humidity:5%-90%. Accuracy: ± 0.5(main moisture range).

Fire starter, OxiTurbo, OxyLazer as seen in

Figure 2 (e). Direct butane pressure at the rate EN 417, type 200.

Testo 845 Infrared Thermometer as seen in

Figure 2 (f). Operational range -30°C up to 600°C. No measurement errors, thanks to focused optics (5 m distance = 10 cm measurement spot).

3.2. Experiment Materials

The materials that were used in the experiment are as follows:

Degraded wood: Pine, Beech, Oak, and Olive as seen in

Figure 3 (a).

Epoxy-based resin. Cadence Resin Art, transparent as seen in

Figure 3 (b). Artistic resin combined with a catalyst allows the creation of decorative shapes, either transparent or colored, and after processing, provides a smooth, durable surface for turning artistic concepts into real works. It is recommended to mix very well before use.

Renner Wood Coatings FL 0510 as seen in

Figure 3 (c). PU Fire Retardant Basecoat – Clear. Good transparency, excellent coverage, no whitening, good wetting properties. The minimum number of coatings minimum of 2. Recommended quantity: 150g/m2. Interval between coats: 2 hours. It is recommended to mix very well before use. Settlement may compromise anti-fire properties. The catalyst used is FC 1110.

Gas canister Kemper Butane as seen in

Figure 3 (d).

4. Experiment

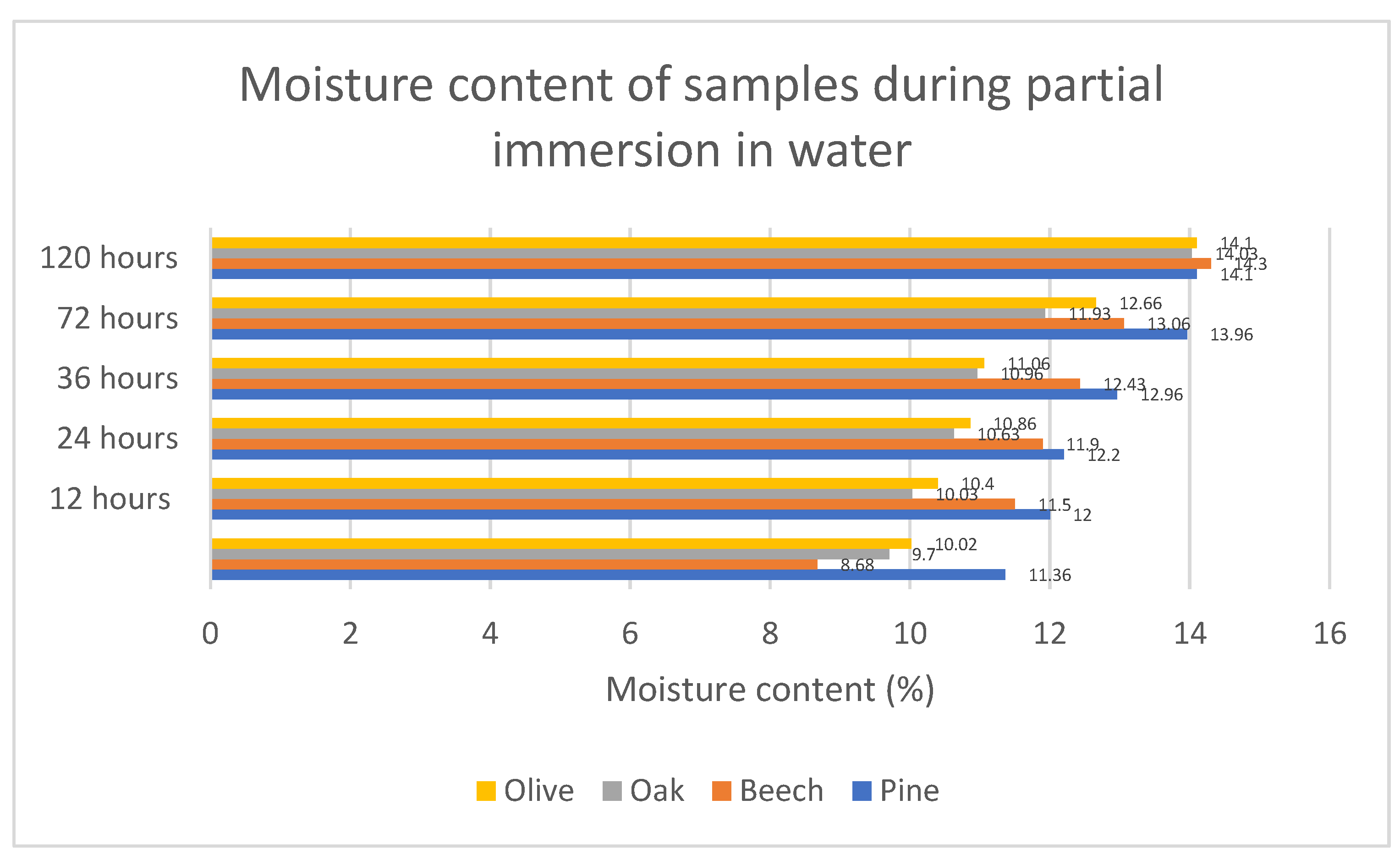

The initial moisture content was measured at five different points of the panel. Four measurements were done at the corners of the panel and one in the middle in order to increase the level of accuracy. The value obtained represents their average. The moisture content after 12, 24, 36, 72, and 120 hours was monitored and measured at three different points at the height level of the capillarity action, respectively, at the ages and in the middle of the sample. The value obtained in

Table 2 and

Figure 4 represents their average.

The moisture content data reveal a more dynamic change across immersion durations. At 12 hours, pine absorbs the highest moisture (11.36%), while olive exhibits the lowest (8.68%), likely due to the hydrophobic influence of natural oils and resins. Pine consistently shows high moisture uptake throughout, reflecting its low resin content and open-cell structure. Oak and beech display intermediate values, suggesting a balance between their anatomical density and moderate resin or extractive content. Granulation plays a role here by increasing surface area and disrupting natural barriers; it enhances water penetration rates over time, with the effect becoming more pronounced in species like olive, where oils initially inhibit but do not permanently prevent moisture absorption.

After 120 hours of exposure, all samples exhibited nearly identical moisture content values, indicating that the absorption process had reached a state of equilibrium. At this stage, the rate of water uptake and release is balanced, and the wood’s cellular structure is fully saturated to the extent allowed by its species-specific hygroscopic properties. The initial differences in absorption rates driven by variations in porosity, resin content, and grain structure become negligible once the fiber saturation point is approached. Consequently, prolonged exposure under constant environmental conditions eliminates the influence of early-stage material characteristics, resulting in converging moisture content values across all tested samples.

The moisture content of all samples remained well below the critical threshold of 15%, indicating excellent resistance to water absorption. This low level of moisture uptake is a positive outcome, as it reduces the risk of dimensional instability, decay, and other moisture-related deterioration. The results suggest that all tested wood types perform effectively in limiting water ingress, making them suitable for applications where durability and stability are essential.

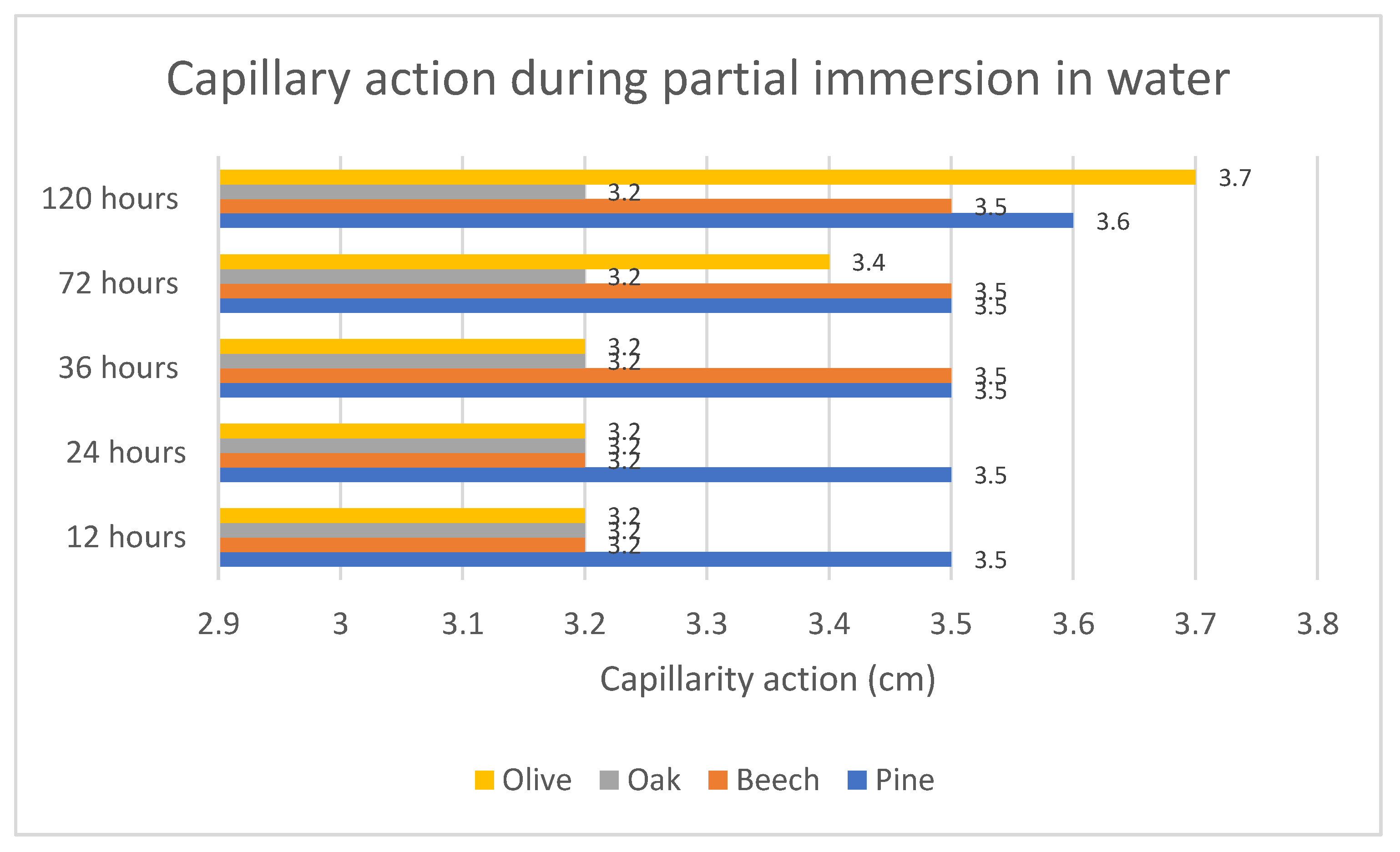

The capillarity action was measured with a tape at three different points along the capillarity line visible in the sample, respectively at the edges and in the middle of the sample. The value obtained in

Table 3 and

Figure 5, represents their average.

The capillarity action results indicate that all wood samples: olive, oak, beech, and pine show relatively stable absorption heights during the initial 12 to 36 hours of immersion, with minimal variation (3.2 -- 3.5 cm). This stability suggests that early-stage water uptake is governed primarily by the inherent pore structures of the species, particularly the vessel and tracheid configurations, rather than resin presence. However, after 72 hours, a divergence becomes evident: pine exhibits slightly higher capillarity (3.6 cm), and olive reaches the highest value (3.7 cm) at 120 hours. The increased values for pine and olive may be linked to their anatomical characteristics. Pine’s open tracheid network facilitates vertical water migration, while olive’s dense grain, when granulated, exposes micro-channels that eventually overcome natural oil barriers. Despite this, the average value of the measurements in the olive sample is balanced. The relatively lower change in oak and beech suggests that their tighter pore arrangements and possible resin content slow further capillary rise after the initial saturation phase.

Figure 6.

Samples during partial immersion in water (a) During 12h; (b) During 120h.

Figure 6.

Samples during partial immersion in water (a) During 12h; (b) During 120h.

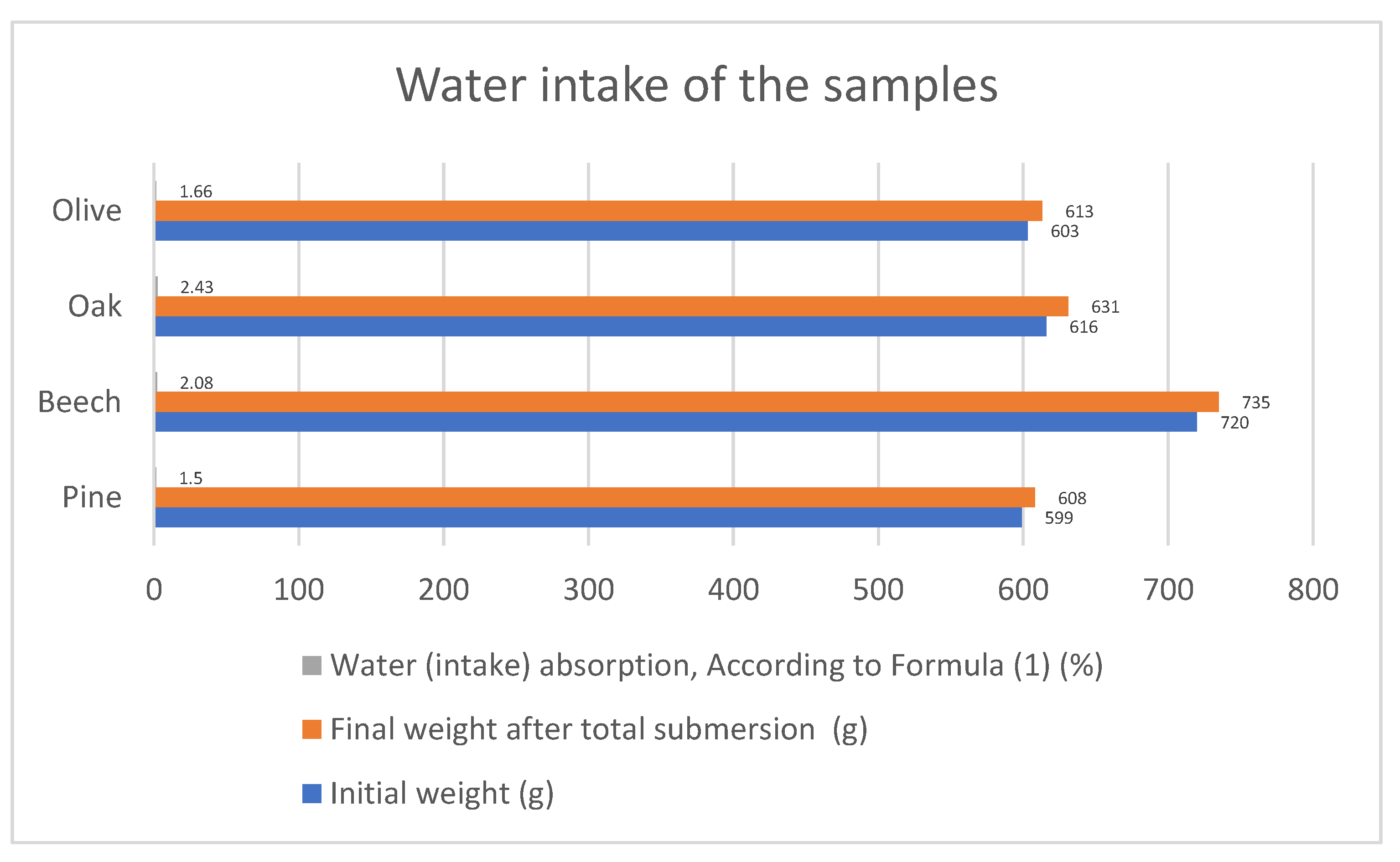

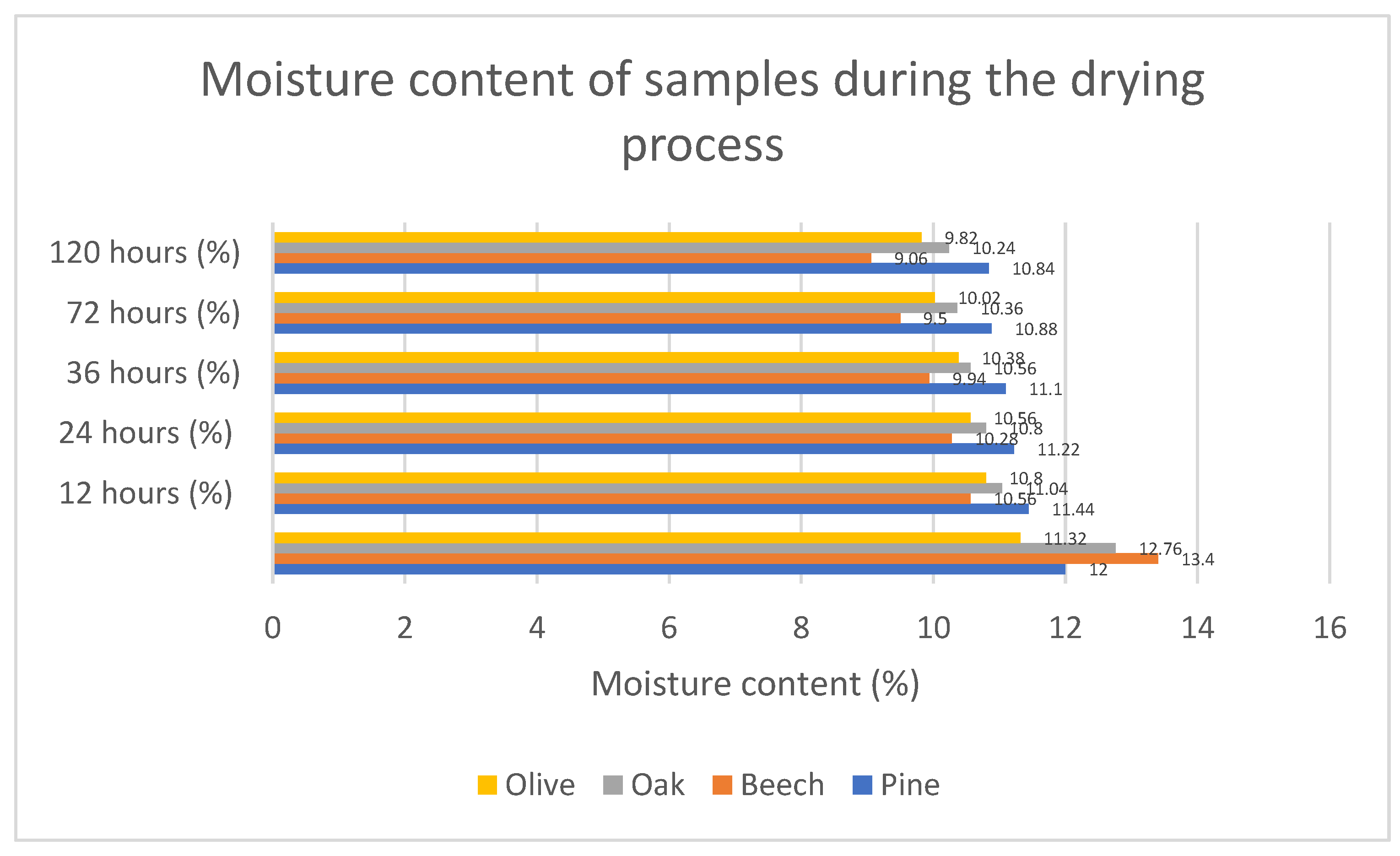

After total submersion in water moisture content was measured at 5 different points for each sample. Four measurements are done at the corners of the panels and one in the middle. The values provided in

Table 4 and

Figure 7 represent the average values for each sample. The samples were first removed from the water and left to dry in a controlled indoor environment for 1 hour. Then the initial moisture content in the material was measured.

The results presented in the graph and

Table 4 illustrate the reduction of moisture content in all four wood species (olive, oak, beech, and pine) during the drying process over a period of 120 hours. At the initial stage of 12 hours, pine showed the highest moisture content (13.4%), followed by beech (12.76%), oak (12.0%), and olive (11.32%). As drying progressed, a gradual decrease was observed across all samples, with values converging after 120 hours. At this stage, moisture levels stabilized between 9.06% for oak and 10.24% for beech, while olive and pine showed intermediate values of 9.82% and 10.84%, respectively. The data indicate that despite initial differences in moisture retention, the samples tend to reach a similar equilibrium point below the critical 15% threshold, which is generally favorable for dimensional stability and resistance against biological degradation. This suggests that all four species, under controlled drying conditions, can achieve suitable moisture performance for construction applications, with oak and olive displaying slightly superior stability compared to pine and beech.

Figure 8.

Water intake of the samples.

Figure 8.

Water intake of the samples.

The appropriate moisture content formula is shown in the paragraph below.

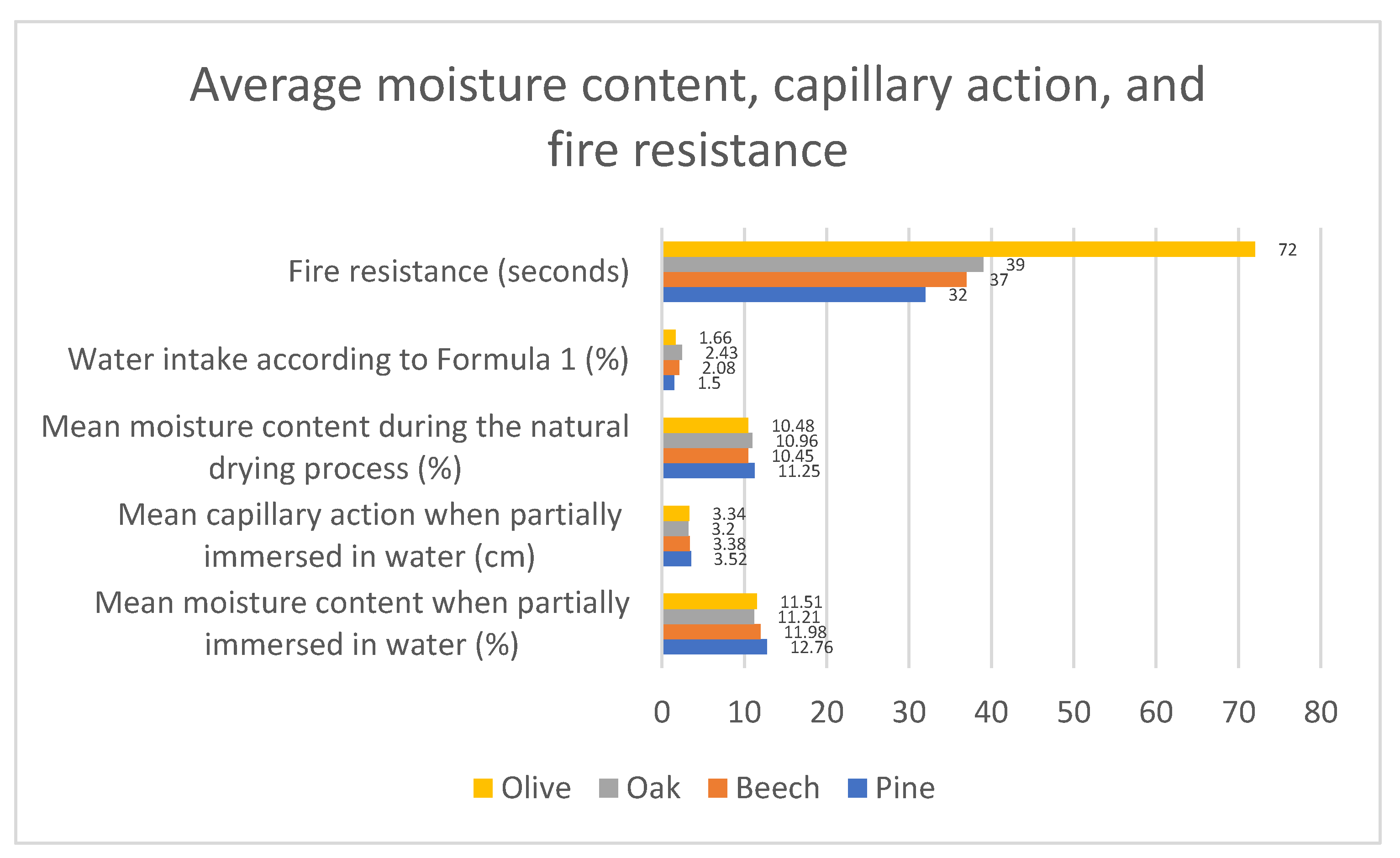

The comparative evaluation of water intake, equilibrium moisture content, and capillarity action reveals distinct performance trends among the four wood species tested, as seen in

Table 5. Beech exhibited the highest final weight after submersion (735 g) and a water absorption of 2.08%, consistent with its dense cellular structure, which allows moderate water uptake while maintaining dimensional stability once equilibrium is reached. Oak recorded the highest absorption rate (2.43%), indicating greater susceptibility to capillary rise despite its good stability over prolonged exposure, making it less favorable than beech in moisture-intensive environments. Olive demonstrated a moderate absorption level (1.66%) but showed higher capillarity in the early stages of immersion compared to oak and beech, likely due to localized vessel orientation, though its naturally oily composition may slow subsequent moisture penetration. Pine displayed the lowest absorption rate (1.50%) and minimal weight gain after submersion, reflecting its low density and limited water retention capacity; however, its higher moisture fluctuations and faster capillary rise suggest lower long-term stability in cyclic humidity conditions. These findings indicate that beech and olive maintain a favorable balance between water resistance and dimensional stability, with beech being particularly suited for ventilated façade applications in variable climates, while oak’s higher capillarity may require additional protective measures.

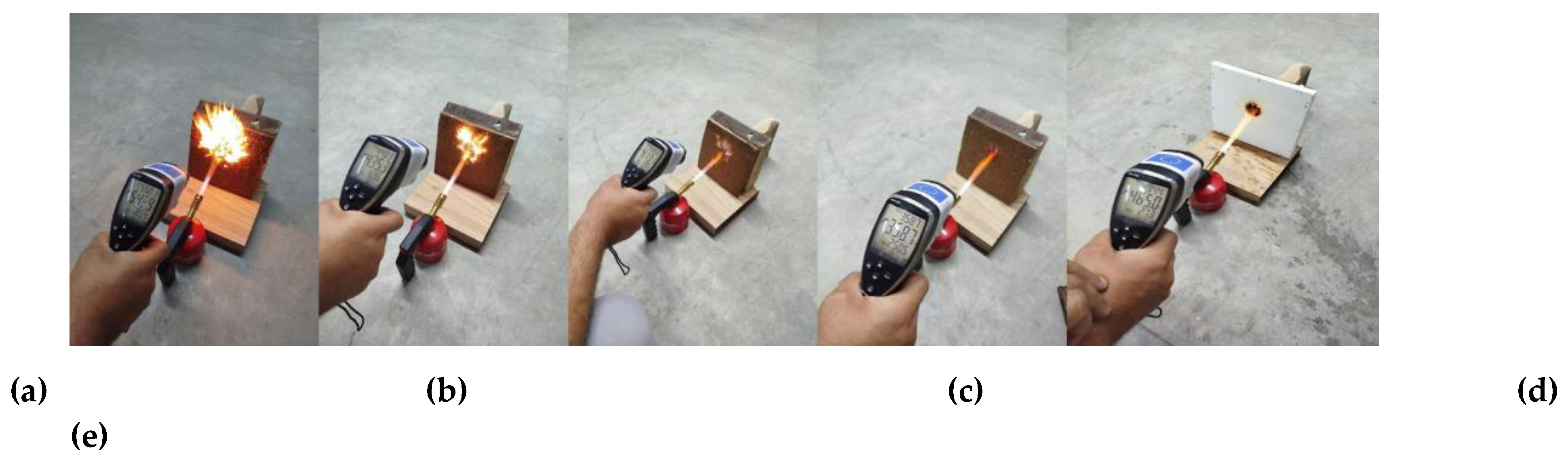

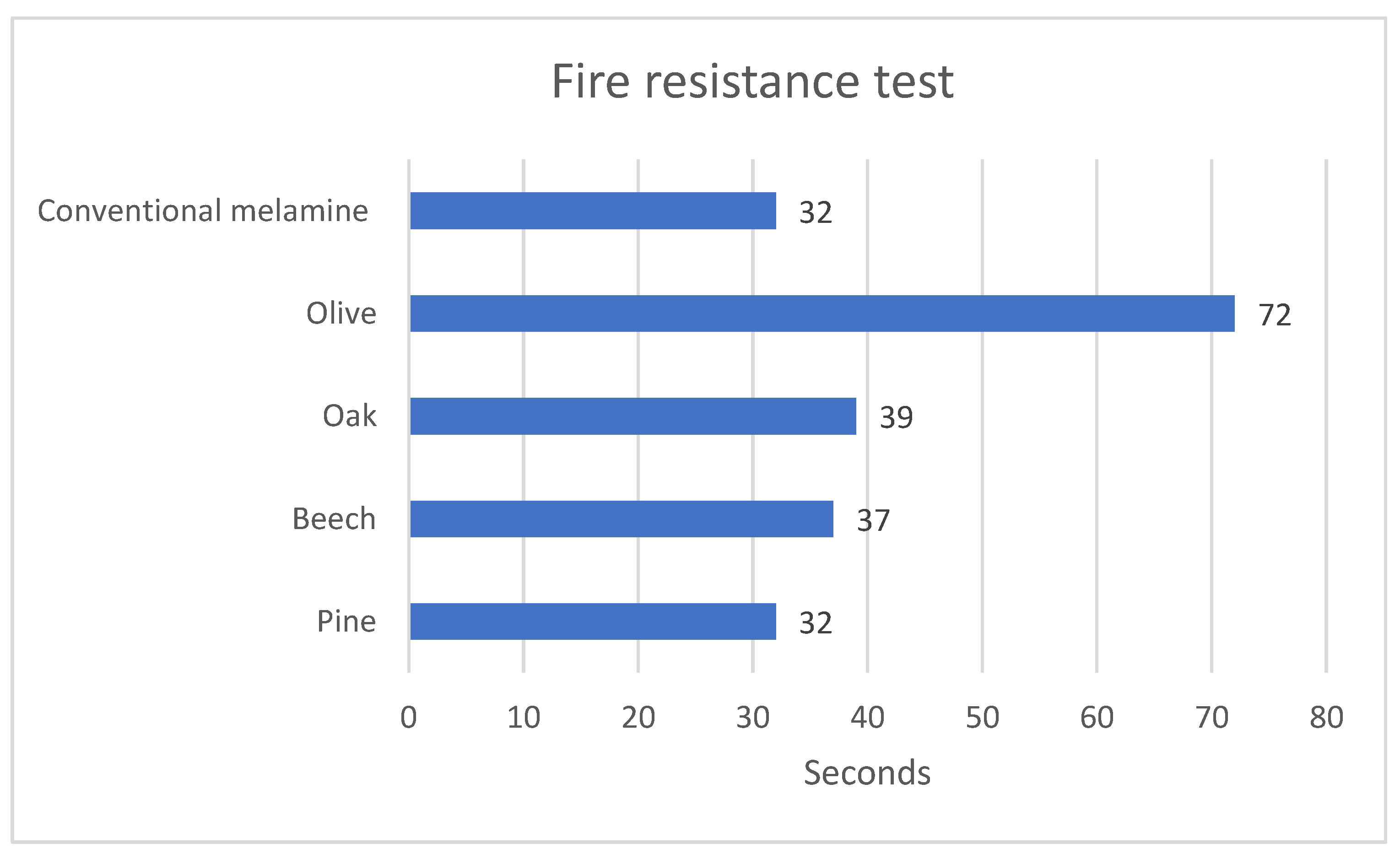

The fire resistance evaluation was conducted on wood panels previously coated with Renner Wood Coatings FL 0510, a fire-retardant basecoat, and allowed to dry for 2 hours before testing. The panels were exposed to a direct flame produced by an OxiTurbo fire starter positioned 23 cm from the surface. At the moment of ignition, the surface temperature of the specimens was 350 °C, gradually rising to 550 °C, which corresponded to the onset of ignition. Surface temperatures during the test were continuously monitored using a Testo 845 infrared thermometer. The results, presented in

Table 6, and

Figure 9, show that olive wood exhibited the highest resistance, with an ignition delay of 72 seconds, nearly double that of oak (39 seconds) and beech (37 seconds), and more than twice that of pine and conventional melamine panels (32 seconds each). These findings highlight the superior performance of olive wood under elevated thermal stress, suggesting its potential suitability in applications where enhanced fire resistance is required.

Figure 10.

Samples during fire resistance test a) Pine sample; (b) Beech sample; (c) Oak sample; (d) Olive sample; (e) Conventional wooden melamine panel.

Figure 10.

Samples during fire resistance test a) Pine sample; (b) Beech sample; (c) Oak sample; (d) Olive sample; (e) Conventional wooden melamine panel.

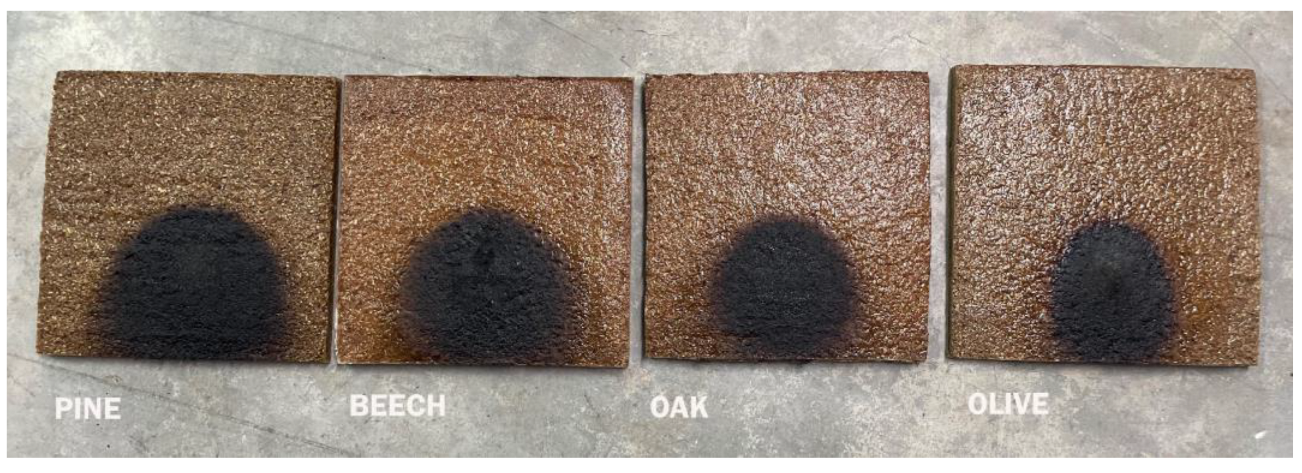

Figure 11.

Samples after the fire resistance test.

Figure 11.

Samples after the fire resistance test.

As seen in

Figure 11, the pine panel exhibited the largest burn area, indicating the lowest resistance to fire exposure among the tested specimens. Beech and oak followed, both showing moderate burn spreads under the same conditions. In contrast, the olive panel developed the smallest burn spot, confirming its superior fire resistance compared to the other materials.

5. Results and Discussions

While solid wood species exhibit distinct capillary behavior, moisture absorption, and fire resistance due to their anatomical and chemical composition, these properties change significantly after granulation. The breakdown of natural vascular structures in the granulation process limits internal water transport, and surface area increases susceptibility to moisture and ignition. Therefore, in this study, these properties are reassessed in the context of composite panels where material behavior is influenced primarily by the binder, treatment method, and structural density of the final product.

The values of

Table 7 and

Figure 12, represent the average values of each component apart from the fire resistance test.

The comparative assessment of pine, beech, oak, and olive wood samples revealed clear differences in their water absorption characteristics, capillarity, and drying performance. Initial water intake measurements indicated that oak absorbed the highest proportion of water according to Formula 1, followed by olive and beech, while pine showed the lowest uptake. However, when analyzing moisture behavior during the natural drying process, oak also retained comparatively higher values, suggesting that although its capillary action is limited, the absorbed water is stored within its vessel structure and released more slowly. In contrast, olive exhibited a balanced performance, combining moderate water intake with a favorable drying rate, which points to better dimensional stability.

Capillarity tests, performed by partially immersing the samples in water, highlighted that pine displayed the greatest upward wicking action, reaching the highest capillary heights, whereas oak and olive showed much more restricted vertical transport. This finding is significant for façade applications, as excessive capillarity increases the risk of moisture migration into higher sections of the panel, potentially accelerating surface degradation. Olive, in particular, exhibited the most favorable balance: its capillary rise was limited, and its moisture content during partial immersion remained below the critical threshold of 15%. Beech showed intermediate behavior, performing moderately well but less consistently than olive.

Overall, the findings indicate that olive wood provides the most dependable performance for ventilated façade applications because of its limited moisture uptake, controlled capillarity, and effective drying. Oak remains a secondary option; although it has low capillarity and good mechanical strength, it is a secondary choice because of its high bulk water absorption and slower drying rate, requiring more protective surface treatment. Beech is a tertiary option, and pine’s high capillarity makes it the least suitable for these applications.

From a practical point of view, the findings of this study assist architects and engineers designing ventilated façade systems. Among the wood species studied, olive and oak showed the best performance in terms of moisture exposure variation and would be suitable for high-exposure façades in rain-prone or humid climates with variable weather conditions. Beech provides a balanced blend with reasonable moisture resistance, favorable workability, and appealing aesthetics. This integration of experimental evidence with practical decision-making can support more durable, sustainable, and resilient building envelopes.

The fire resistance results can also be interpreted in relation to the limiting oxygen index (LOI) concept, where higher LOI values correspond to greater resistance to burning. Materials with low LOI values (<21%) ignite and sustain combustion easily under normal atmospheric conditions, whereas higher LOI values indicate stronger resistance. In this context, the differences seen in the tested species relative to the reference panel illustrate different oxygen significances needed to ignite and combust. LOI provides a basic intrinsic measurement of flammability, and UL94 provides a practical evaluation of how long a material burns after being ignited (like a visual performance). Together they frame a clearer idea of how the tested wood species would behave in a real fire based on their relative fire resistance parameters.

The observed fire resistance performances of the tested panels appear to follow generally consistent patterns with LOI and UL94. The olive wood, exhibiting the greatest ignition delay, can be assumed to present a higher, effective LOI, where a higher amount of oxygen is needed to sustain combustion, as opposed to pine and melamine panel that ignited relatively quickly and would suggest a lower LOI, therefore sustain combustion in normal atmospheric conditions. Oak and beech displayed intermediate behavior and reflected some moderate level of fire resistance. The performance results provide corroboration that while LOI measurements are basic indicators of intrinsic flammability, the UL94 based performance results represent a practical assessment of how each material behaves under relatively constant conditions of direct flame exposure.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the water absorption behavior, equilibrium moisture content, capillarity, and fire resistance of pine, beech, oak, and olive wood treated with resin mixtures and fire resistance paint. Among the species, olive showed the highest delay to ignition, confirming superior fire resistance compared to pine, beech, and oak. In terms of moisture performance, oak and olive proved the most stable, with reduced dimensional changes once equilibrium was reached. Beech demonstrated moderate but consistent results, while pine, despite its workability, showed greater moisture fluctuations, limiting its suitability without protective treatments. Overall, olive and oak appear as the most reliable candidates for ventilated façade applications, while beech remains a balanced alternative and pine a cost-effective option when treated.

The study is limited by its laboratory conditions, which do not fully capture long-term exposure to natural climate cycles such as wetting–drying, freezing–thaw, or pro-longed UV radiation. Future work should address these aspects, alongside testing surface coatings and hybrid systems, to better predict real performance and service life.

From a practical perspective, oak is recommended where durability and low maintenance are essential, olive where both aesthetics and technical reliability are required, and beech where a balanced compromise is desired. Pine remains feasible in less demanding conditions or with protective measures.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, Klodjan Xhexhi, and Blerim Nika; methodology, Klodjan Xhexhi, and Blerim Nika.; software, Klodjan Xhexhi, and Blerim Nika; validation, Klodjan Xhexhi, Blerim Nika, Ledian Bregasi, Ilda Rusi, Sonia Jojic and Nikolla Vesho.; formal analysis, Blerim Nika, Ledian Bregasi, Ilda Rusi, Sonia Jojic; investigation, Klodjan Xhexhi, and Nikolla Vesho; resources, Ledian Bregasi, Ilda Rusi, Sonia Jojic, and Nikolla Vesho; data curation, Klodjan Xhexhi, and Blerim Nika; writing—original draft preparation, Klodjan Xhexhi, Blerim Nika; writing—review and editing, Klodjan Xhexhi, Blerim Nika, Ledian Bregasi, Ilda Rusi, Sonia Jojic and Nikolla Vesho; visualization, Klodjan Xhexhi and Blerim Nika; supervision, Klodjan Xhexhi and Blerim Nika; project administration, Klodjan Xhexhi and Blerim Nika; funding acquisition, Klodjan Xhexhi, Blerim Nika, Ledian Bregasi, Ilda Rusi, and Sonia Jojic. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

Please add: This research was funded by “AKKSHI “(National Agency for Scientific Research and Innovation, Albania), Project title: Sustainable Panels; Recycling wood, plastic and glass for ventilated facades, grant number (contract protocol number: “938/1 Prot. Date 26.06.2025”), and “The APC” was funded by AKKSHI.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

This article is supported by AKKSHI (National Agency for Scientific Research and Innovation, Albania).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WPC |

Wood-based polymer composites |

| MAPE |

Maleic anhydride grafted polyethylene |

| HDPE |

High-Density Polyethylene |

| LDPE |

Low-Density Polyethylene |

| PP |

Polypropylene |

| PVC |

Polyvinyl Chloride |

| EPS |

Expanded Polystyrene |

| PS |

Polystyrene |

FR

MAPP |

Flame retardants

Maleic anhydride grafted polypropylene |

| LOI |

Limiting Oxygen Index |

| UL94 |

Underwriters Laboratories (flammability standard) |

| V0 |

Level of flame retardancy of a material |

| AKKSHI |

National Agency for Scientific Research and Innovation, Albania |

| |

|

References

- Amarasinghe, I. T.; Qian, Y.; Gunawardena, T.; Mendis, P.; Belleville, B. Composite Panels from Wood Waste: A Detailed Review of Processes, Standards, and Applications. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xhexhi, K.; Aliaj, B. Water absorption, moisture content, and capillarity action in wood: A comparative analysis of fir, pine, beech, and oak. Adv. Eng. Forum 2025, 55, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Chen, J.; Pan, D.; Hou, Y. Robust, Fire-Retardant, and Water-Resistant Wood/Polyimide Composite Aerogels with a Hierarchical Pore Structure for Thermal Insulation. Gels 2023, 9, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancel, V.; Čabalová, I.; Krilek, J.; Réh, R.; Zachar, M.; Jurczyková, T. Fire Resistance Evaluation of New Wooden Composites Containing Waste Rubber from Automobiles. Polymers 2022, 14, 4465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xhexhi, K.; Aliaj, B. Water absorption, capillarity action, and materials composition of different bricks and panels as part of the external coating of buildings. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 585, 01015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, K. B.; Pang, S. S.; Staiger, M. P. Long-term moisture absorption and thickness swelling behaviour of recycled thermoplastics reinforced with Pinus radiata sawdust. Chem. Eng. J. 2008, 142, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, G.; Wang, Y.; Ma, R. Fire retardancy and water absorption of borated wood flour/polycarbonate biocomposites. Polymers 2022, 14, 2234. [Google Scholar]

- Kouadio, K.C.; Traoré, B.; Kaho, S.P.; Kouakou, C.H.; Emeruwa, E. Influence of mineral filler on fire behaviour and mechanical properties of wood waste composite with EPS binder. Open J. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 834–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, M.; Rajeshkumar, L.; Sasikala, G.; Balaji, D.; Saravanakumar, A.; Bhuvaneswari, V.; Bhoopathi, R. A Critical Review on Wood-Based Polymer Composites: Processing, Properties, and Prospects. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozdemir, T.; Mengeloglu, F. Some Properties of Composite Panels Made from Wood Flour and Recycled Polyethylene. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2008, 9, 2559–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Mishra, A.; Thakur, V. K.; Pappu, A. Towards sustainable wood-plastic composites: polymer type, properties, processing and future prospects. RSC Sustainability. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Schirp, A.; Schwarz, B. Influence of compounding conditions, treatment of wood particles with fire-retardants and artificial weathering on properties of wood-polymer composites for façade applications. Eur. J. Wood & Wood Prod. 2021, 79, 821–840. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Wang, S.; Meng, D.; et al. A facile preparation of environmentally-benign and flame-retardant coating on wood by comprising polysilicate and boric acid. Cellulose 2021, 28, 11551–11566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divya, H. V.; Kavya, H. M.; Saravana Bavan, D.; Yogesha, B. Evaluation of Mechanical Properties of Wood Particles Reinforced Polymer Composites. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2018, 5, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Fire safe Europe. Sustainability. Available online: https://www.firesafeeurope.eu/sustainability (accessed on 02.09.2025).

- Doménech, P.; Duque, A.; Higueras, I.; Fernández, J. L.; Manzanares, P. Analytical Characterization of Water-Soluble Constituents in Olive-Derived By-Products. Foods 2021, 10(6), 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).