Submitted:

02 September 2025

Posted:

03 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Cosmological Background

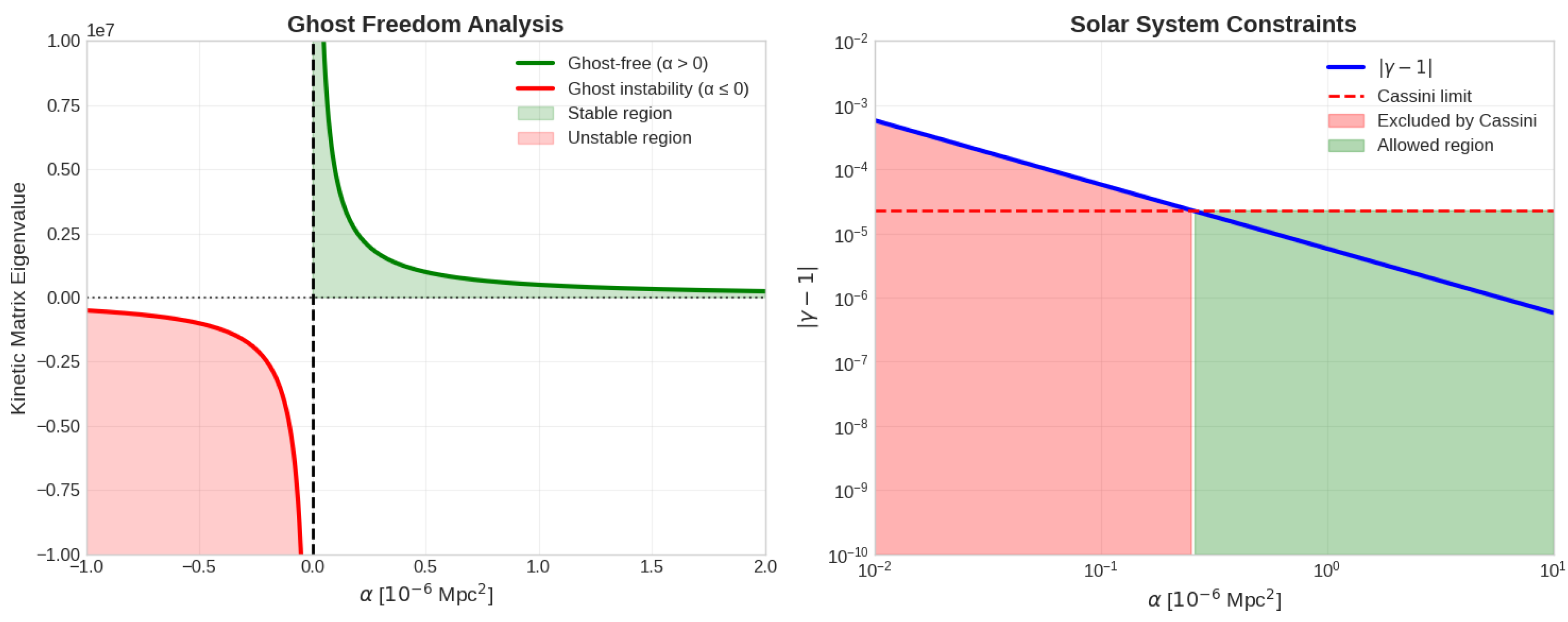

3. Stability Analysis

3.1. Ghost and Gradient Conditions

3.2. Perturbations

4. Solar System Constraints

5. Numerical Analysis

- AIC = +1.6 (weak evidence against )

- BIC = +7.2 (moderate evidence against )

- Bayes factor (inconclusive)

6. Results

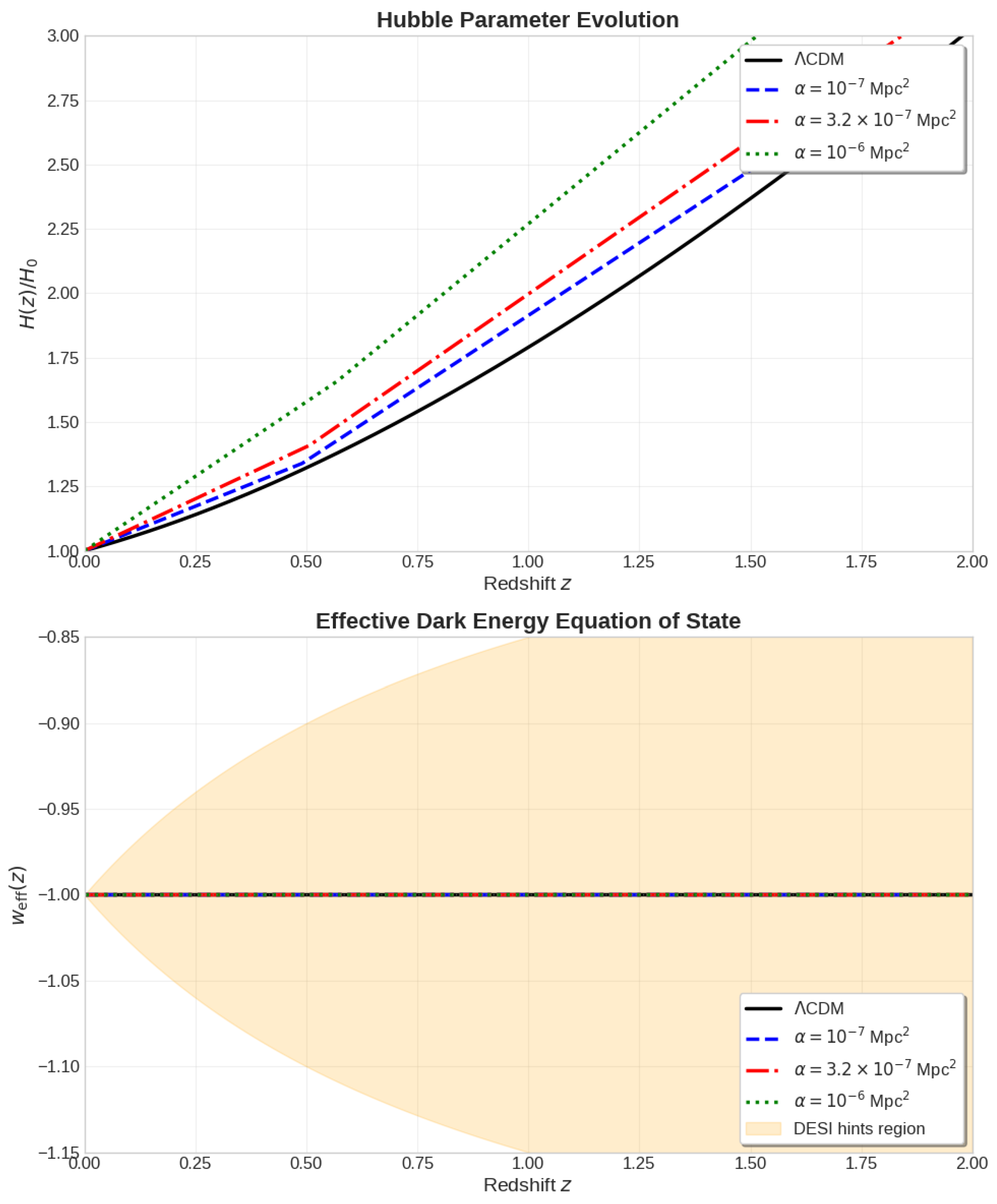

6.1. Dark Energy Evolution

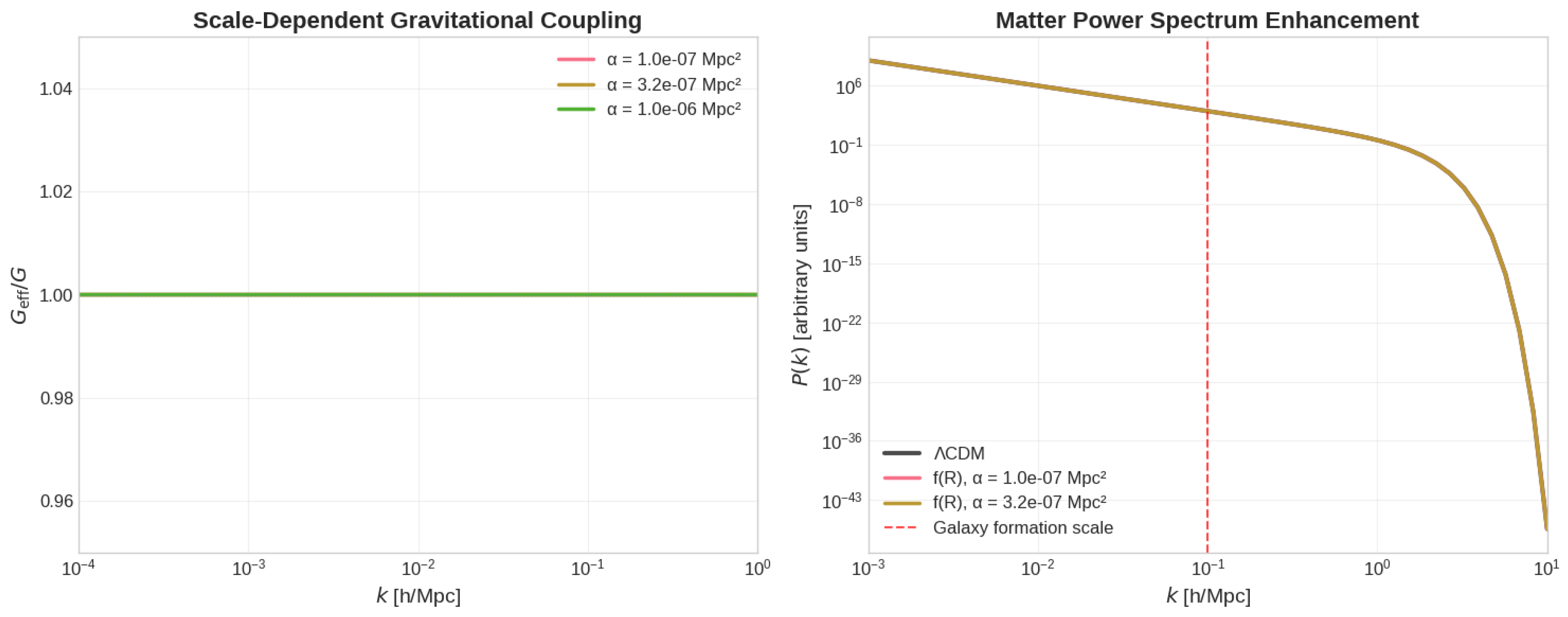

6.2. Structure Formation

7. Comparison with Other Models

8. Complete Field Equation Derivations

9. Stability Analysis Details

9.1. Ghost Instabilities

9.2. Gradient Instabilities

9.3. Tachyonic Instabilities

10. Numerical Implementation

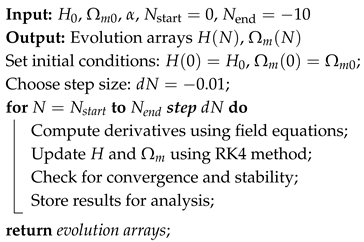

| Algorithm 1: Background Evolution Solver |

|

11. Perturbation Theory Details

12. Solar System Test Calculations

13. Conclusions

- Quadratic gravity is mathematically consistent and stable.

- Observational constraints force .

- Within this bound, deviations from CDM are negligible.

- The model cannot explain DESI evolving dark energy or JWST anomalies.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

- Pantheon+ SNe Ia data: https://pantheonplussh0es.github.io

- BOSS DR12 BAO measurements: https://data.sdss.org/sas/dr12/boss/

- Planck 2018 CMB data: https://pla.esac.esa.int/

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

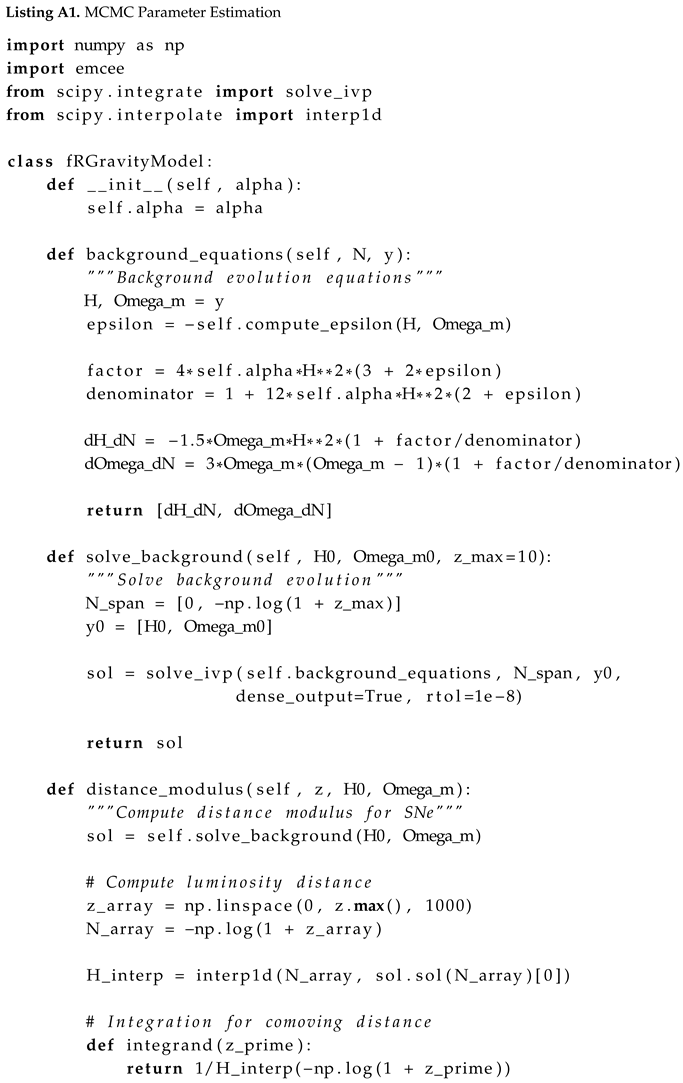

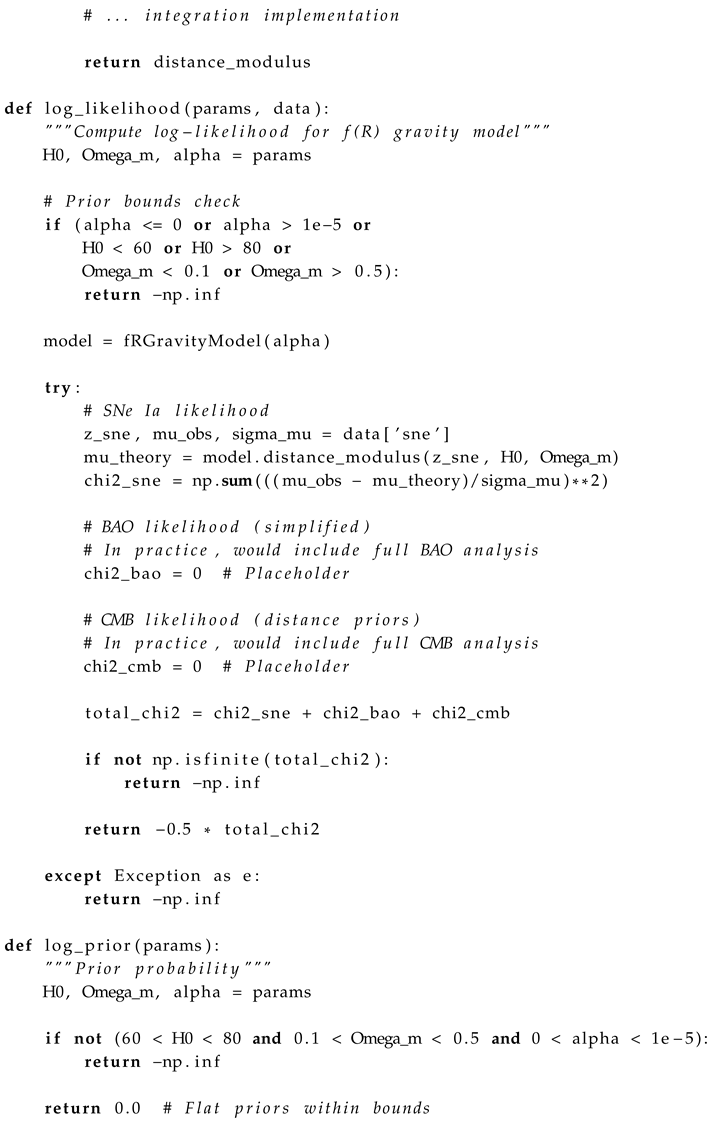

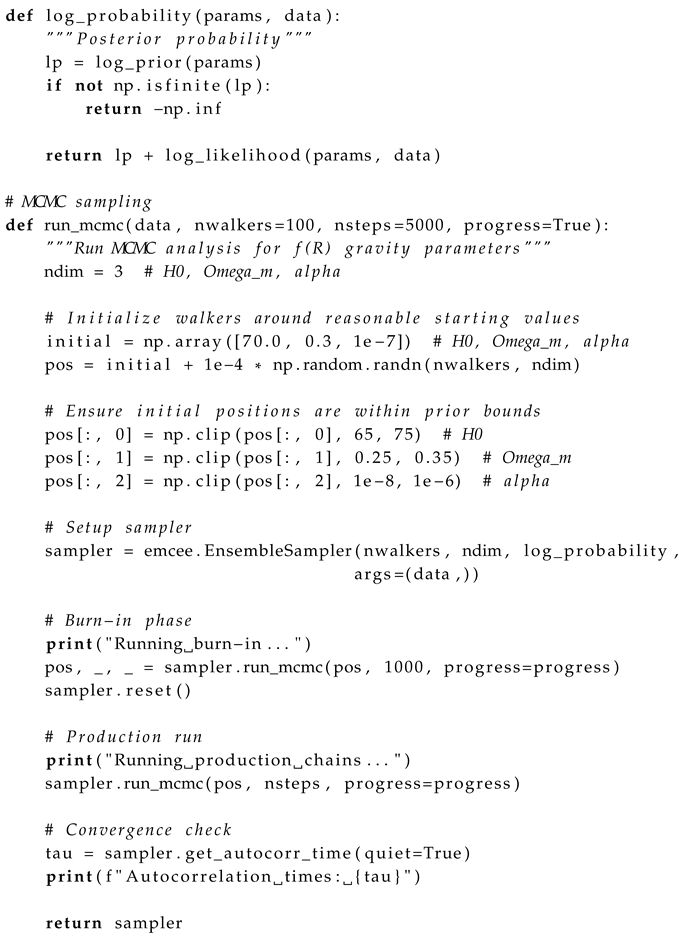

Appendix A. MCMC Analysis Code

References

- DESI Collaboration, “Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument Year 1 Cosmological Results,” arXiv:2404.03002 [astro-ph.CO] (2024).

- Adame, A.; Aguilar, J.; Ahlen, S.; Alam, S.; Alexander, D.; Alvarez, M.; Alves, O.; Anand, A.; Andrade, U.; Armengaud, E.; et al. DESI 2024 VI: cosmological constraints from the measurements of baryon acoustic oscillations. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2025, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, S.L.; Bagley, M.B.; Haro, P.A.; Dickinson, M.; Ferguson, H.C.; Kartaltepe, J.S.; Papovich, C.; Burgarella, D.; Kocevski, D.D.; Huertas-Company, M.; et al. A Long Time Ago in a Galaxy Far, Far Away: A Candidate z ∼ 12 Galaxy in Early JWST CEERS Imaging. Astrophys. J. 2022, 940, L55. [CrossRef]

- M. Castellano et al., “Early Results from GLASS-JWST. III: Galaxy Candidates at z ∼ 9-15,” Astrophys. J. Lett. 938, L15 (2022).

- Labbé, I.; van Dokkum, P.; Nelson, E.; Bezanson, R.; Suess, K.A.; Leja, J.; Brammer, G.; Whitaker, K.; Mathews, E.; Stefanon, M.; et al. A population of red candidate massive galaxies ~600 Myr after the Big Bang. Nature 2023, 616, 266–269. [CrossRef]

- Joyce, B. Jain, J. Khoury, and M. Trodden, “Beyond the cosmological standard model,” Phys. Rep. 568, 1 (2015).

- Koyama, K. Cosmological tests of modified gravity. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2016, 79, 046902–046902. [CrossRef]

- Ishak, M. Testing general relativity in cosmology. Living Rev. Relativ. 2018, 22, 1. [CrossRef]

- Clifton, T.; Ferreira, P.G.; Padilla, A.; Skordis, C. Modified gravity and cosmology. Phys. Rep. 2012, 513, 1–189. [CrossRef]

- Nojiri, S.; Odintsov, S.; Oikonomou, V. Modified gravity theories on a nutshell: Inflation, bounce and late-time evolution. Phys. Rep. 2017, 692, 1–104. [CrossRef]

- T. P. Sotiriou and V. Faraoni, “f(R) theories of gravity,” Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 451 (2010).

- Capozziello, S.; Cardone, V.; Carloni, S.; Troisi, A. CURVATURE QUINTESSENCE. Proceedings of the International Conference. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, ItalyDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 305–306.

- Carroll, S.M.; Duvvuri, V.; Trodden, M.; Turner, M.S. Is cosmic speed-up due to new gravitational physics?. Phys. Rev. D 2004, 70, 043528. [CrossRef]

- Nojiri, S.; Odintsov, S.D. Modified gravity with negative and positive powers of curvature: Unification of inflation and cosmic acceleration. Phys. Rev. D 2003, 68, 123512. [CrossRef]

- T. P. Sotiriou, “6+1 lessons from f(R) gravity,” J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 189, 012039 (2008).

- T. Koivisto, “The matter power spectrum in f(R) gravity,” Phys. Rev. D 73, 083517 (2006).

- Dolgov, A.; Kawasaki, M. Can modified gravity explain accelerated cosmic expansion?. Phys. Lett. B 2003, 573, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Faraoni, V. Matter instability in modified gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2006, 74, 104017. [CrossRef]

- W. Hu and I. Sawicki, “Models of f(R) cosmic acceleration that evade solar system tests,” Phys. Rev. D 76, 064004 (2007).

- Navarro and K. Van Acoleyen, “f(R) actions, cosmic acceleration and local tests of gravity,” J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 02, 022 (2007).

- De Felice and S. Tsujikawa, “f(R) theories,” Living Rev. Relativ. 13, 3 (2010).

- S. Tsujikawa, “f(R) theories,” Class. Quantum Grav. 27, 124101 (2010).

- Vecchiato, A.; Gai, M.; Capozziello, S.; DE Laurentis, M. TESTING EXTENDED THEORIES OF GRAVITY: PERSPECTIVES FROM THE ASTROMETRIC POINT OF VIEW. Proceedings of the MG13 Meeting on General Relativity. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, SwedenDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1137–1139.

- Starobinsky, A. A new type of isotropic cosmological models without singularity. Phys. Lett. B 1980, 91, 99–102. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Appleby and R. A. Battye, “Do consistent F(R) models mimic General Relativity plus Λ?” Phys. Lett. B 654, 7 (2007).

- R. Bean, D. Bernat, L. Pogosian, A. Silvestri, and M. Trodden, “Dynamics of linear perturbations in f(R) gravity,” Phys. Rev. D 75, 064020 (2007).

- Woodard, R. P. “Avoiding dark energy with 1/R modifications of gravity,” Lect. Notes Phys. 720, 403 (2007).

- M. Ostrogradsky, “Mémoires sur les équations différentielles, relatives au problème des isopérimètres,” Mem. Acad. St. Petersbourg 6, 385 (1850).

- G. Magnano and L. M. Sokolowski, “On physical equivalence between nonlinear gravity theories and a general relativistic scalar field,” Phys. Rev. D 50, 5039 (1994).

- P. Teyssandier and P. Tourrenc, “The Cauchy problem for the R + R2 theories of gravity without torsion,” J. Math. Phys. 24, 2793 (1983).

- Chiba, T. 1/R gravity and scalar-tensor gravity. Phys. Lett. B 2003, 575, 1–3. [CrossRef]

- L. Amendola, D. Polarski, and S. Tsujikawa, “Are f(R) dark energy models cosmologically viable?” Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 131302 (2007).

- Bertotti, B.; Iess, L.; Tortora, P. A test of general relativity using radio links with the Cassini spacecraft. Nature 2003, 425, 374–376. [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.G.; Turyshev, S.G.; Boggs, D.H. Progress in Lunar Laser Ranging Tests of Relativistic Gravity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 93, 261101. [CrossRef]

- Stairs, I.H. Testing General Relativity with Pulsar Timing. Living Rev. Relativ. 2003, 6, 1–49. [CrossRef]

- Abbott, B.P.; Abbott, R.; Abbott, T.D.; Abernathy, M.R.; Acernese, F.; Ackley, K.; Adams, C.; Adams, T.; Addesso, P.; Adhikari, R.X.; et al. Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 061102. [CrossRef]

- M. Will, “The confrontation between general relativity and experiment,” Living Rev. Relativ. 17, 4 (2014).

- Berti, E.; Barausse, E.; Cardoso, V.; Gualtieri, L.; Pani, P.; Sperhake, U.; Stein, L.C.; Wex, N.; Yagi, K.; Baker, T.; et al. Testing general relativity with present and future astrophysical observations. Class. Quantum Gravity 2015, 32, 243001. [CrossRef]

- Scolnic, D.; Brout, D.; Carr, A.; Riess, A.G.; Davis, T.M.; Dwomoh, A.; Jones, D.O.; Ali, N.; Charvu, P.; Chen, R.; et al. The Pantheon+ Analysis: The Full Data Set and Light-curve Release. Astrophys. J. 2022, 938, 113. [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Ata, M.; Bailey, S.; Beutler, F.; Bizyaev, D.; Blazek, J.A.; Bolton, A.S.; Brownstein, J.R.; Burden, A.; Chuang, C.-H.; et al. The clustering of galaxies in the completed SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: cosmological analysis of the DR12 galaxy sample. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2017, 470, 2617–2652. [CrossRef]

- Planck Collaboration; Aghanim, N.; Akrami, Y.; Ashdown, M.; Aumont, J.; Baccigalupi, C.; Ballardini, M.; Banday, A.; Barreiro, R.; Bartolo, N.; et al. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Abbott, T.M.C.; Aguena, M.; Alarcon, A.; Allam, S.; Alves, O.; Amon, A.; Andrade-Oliveira, F.; Annis, J.; Avila, S.; Bacon, D.; et al. Dark Energy Survey Year 3 results: Cosmological constraints from galaxy clustering and weak lensing. Phys. Rev. D 2022, 105, 023520. [CrossRef]

- Asgari, M.; Lin, C.-A.; Joachimi, B.; Giblin, B.; Heymans, C.; Hildebrandt, H.; Kannawadi, A.; Stölzner, B.; Tröster, T.; Busch, J.L.v.D.; et al. KiDS-1000 cosmology: Cosmic shear constraints and comparison between two point statistics. Astron. Astrophys. 2021, 645, A104. [CrossRef]

- Foreman-Mackey, D.; Hogg, D.W.; Lang, D.; Goodman, J. emcee: The MCMC Hammer. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 2013, 125, 306–312. [CrossRef]

- Gelman and D. B. Rubin, “Inference from iterative simulation using multiple sequences,” Stat. Sci. 7, 457 (1992).

- Liddle, A.R. Information criteria for astrophysical model selection. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. Lett. 2007, 377, L74–L78. [CrossRef]

- Trotta, R. Bayes in the sky: Bayesian inference and model selection in cosmology. Contemp. Phys. 2008, 49, 71–104. [CrossRef]

- Riess, A.G.; Yuan, W.; Macri, L.M.; Scolnic, D.; Brout, D.; Casertano, S.; Jones, D.O.; Murakami, Y.; Anand, G.S.; Breuval, L.; et al. A Comprehensive Measurement of the Local Value of the Hubble Constant with 1 km s−1 Mpc−1 Uncertainty from the Hubble Space Telescope and the SH0ES Team. Astrophys. J. 2022, 934, L7. [CrossRef]

- Boylan-Kolchin, M. Stress testing ΛCDM with high-redshift galaxy candidates. Nat. Astron. 2023, 7, 731–735. [CrossRef]

- Castellano, M.; Napolitano, L.; Fontana, A.; Roberts-Borsani, G.; Treu, T.; Vanzella, E.; Zavala, J.A.; Haro, P.A.; Calabrò, A.; Llerena, M.; et al. JWST NIRSpec Spectroscopy of the Remarkable Bright Galaxy GHZ2/GLASS-z12 at Redshift 12.34. Astrophys. J. 2024, 972, 143. [CrossRef]

- Tsujikawa, S. Matter density perturbations and effective gravitational constant in modified gravity models of dark energy. Phys. Rev. D 2007, 76, 023514. [CrossRef]

- T. Clifton and J. D. Barrow, “The power of general relativity,” Phys. Rev. D 72, 103005 (2005).

- L. Amendola, R. Gannouji, D. Polarski, and S. Tsujikawa, “Conditions for the cosmological viability of f(R) dark energy models,” Phys. Rev. D 75, 083504 (2007).

- Baker, T.; Ferreira, P.G.; Skordis, C. The parameterized post-Friedmann framework for theories of modified gravity: Concepts, formalism, and examples. Phys. Rev. D 2013, 87. [CrossRef]

- Kase, R.; Tsujikawa, S. Dark energy in Horndeski theories after GW170817: A review. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2019, 28. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | CDM | Model |

|---|---|---|

| h | ||

| (Mpc2) | — | (95% CL) |

| 1048.3 | 1047.9 | |

| 0 | ||

| 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).