Submitted:

02 September 2025

Posted:

03 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Transcriptome Data Sources

2.2. Transcriptome Data Processing

2.3. Identification of Tissue-Specific Differentially Expressed Genes

2.4. Machine Learning-Based Identification of Tissue-Specific Genes

2.5. Construction of Innate Immune Gene Co-Expression Networks

2.6. Gene Enrichment Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Transcriptome Data

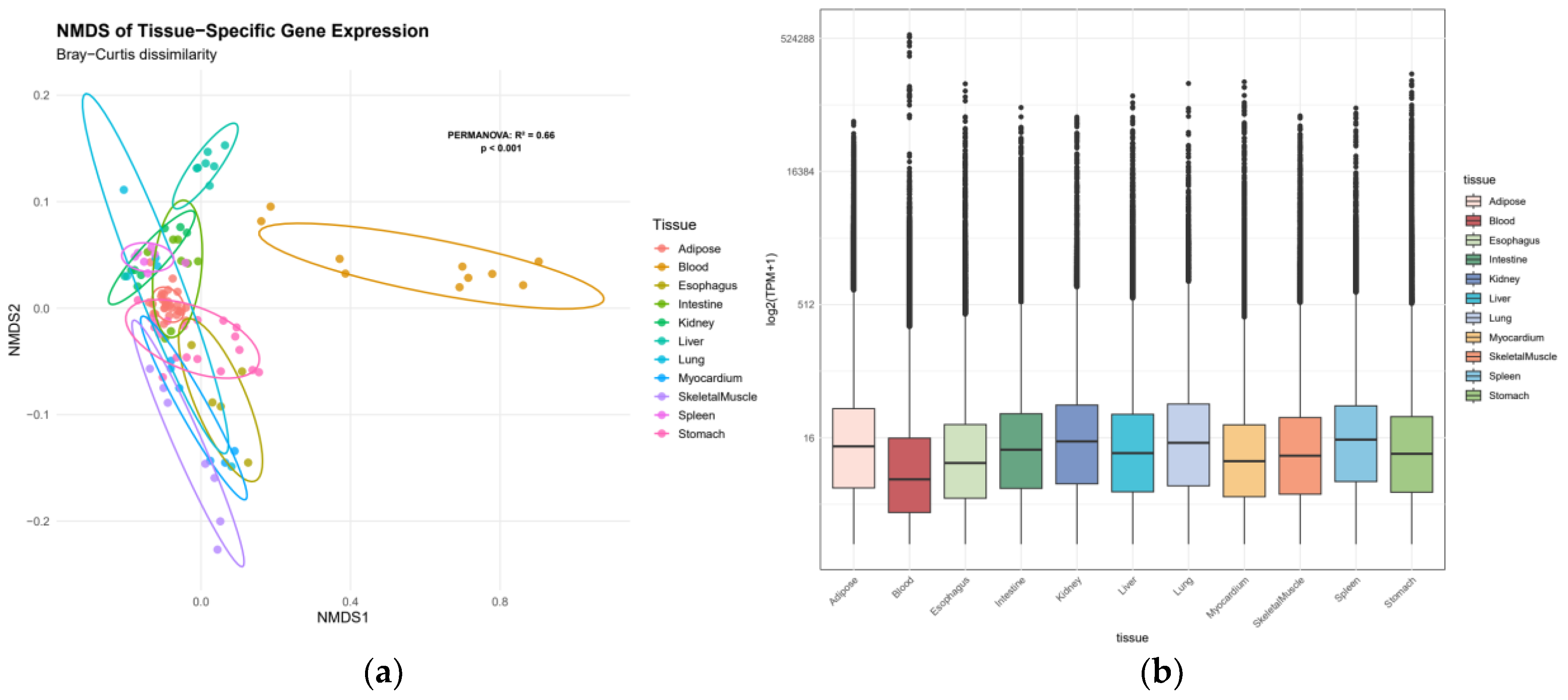

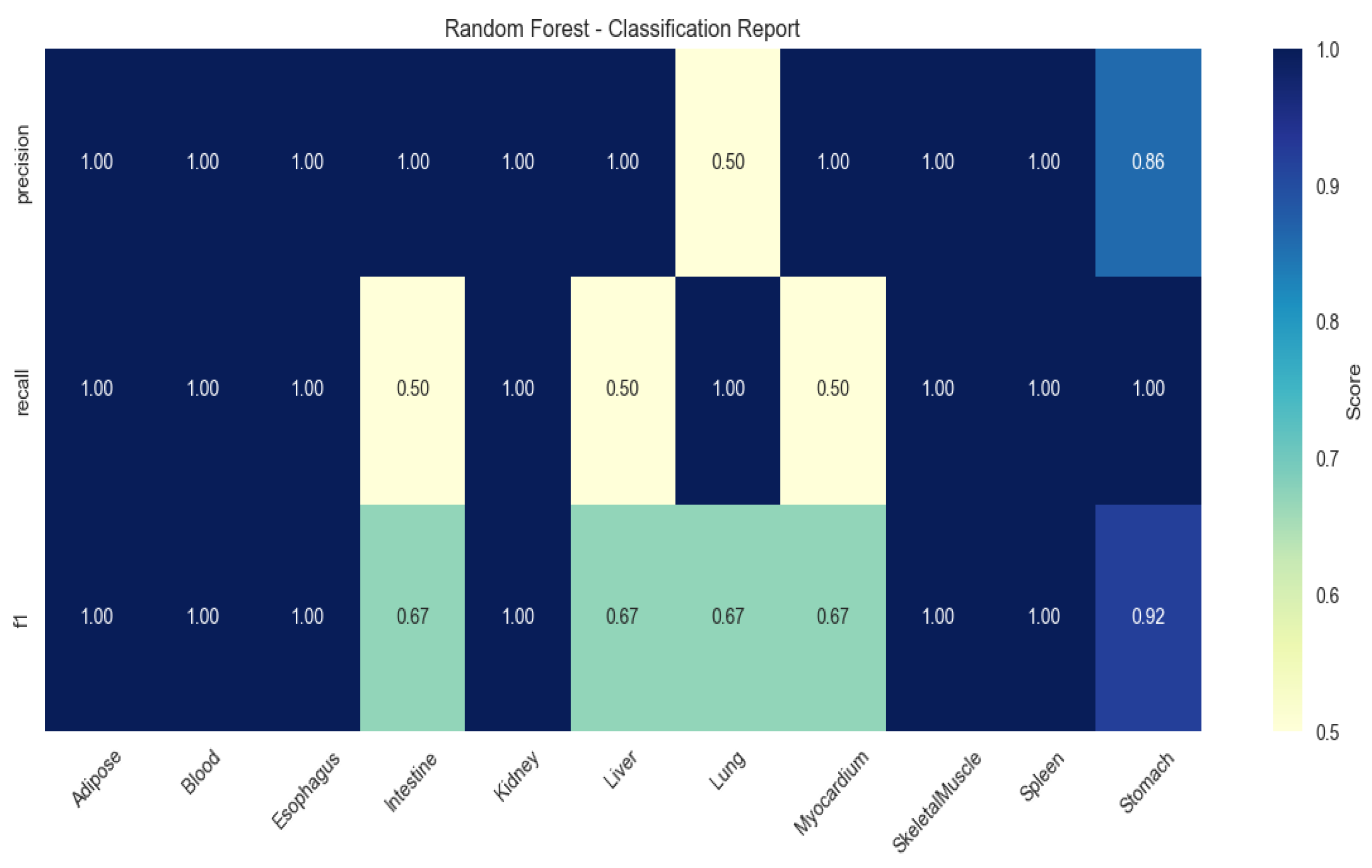

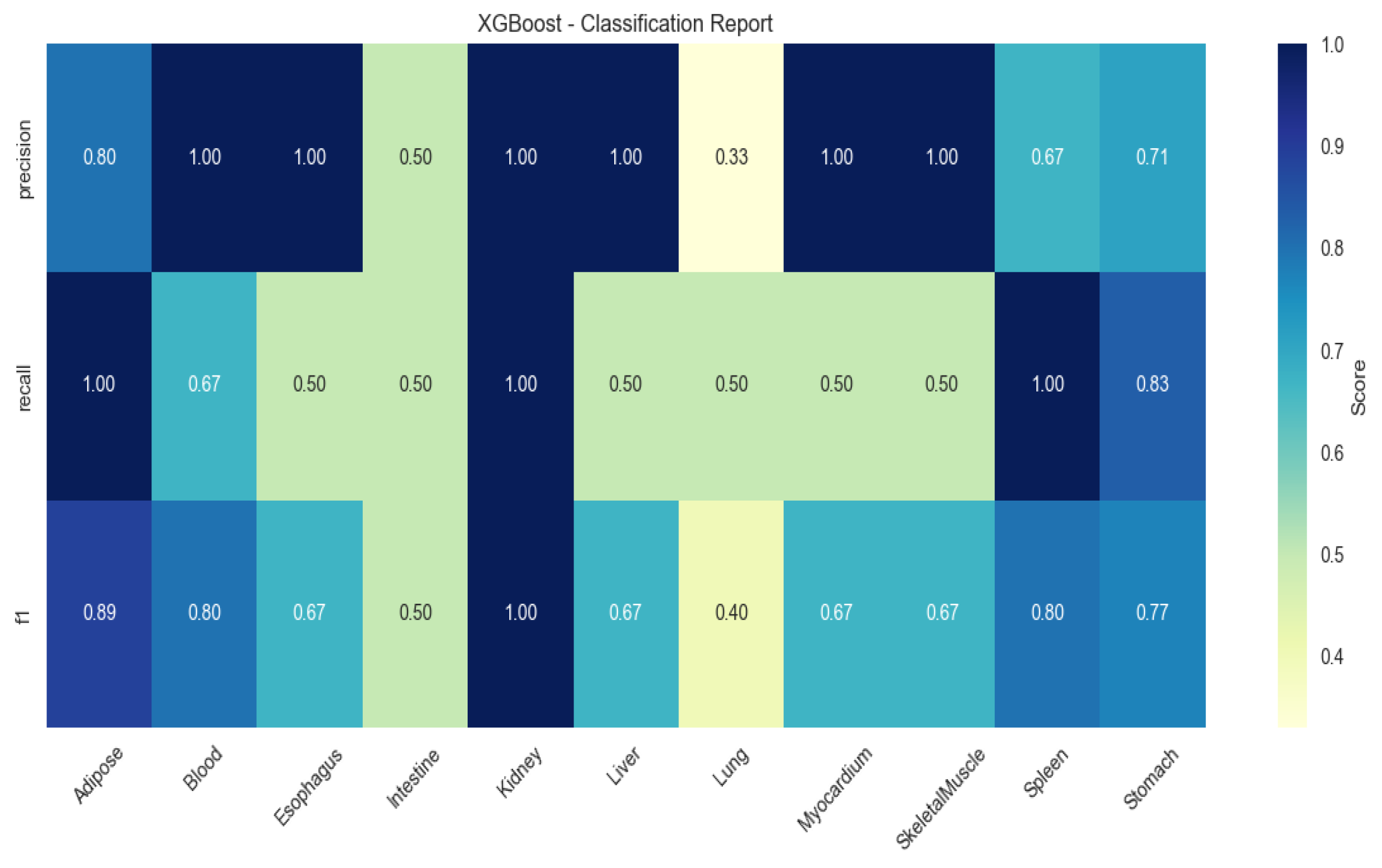

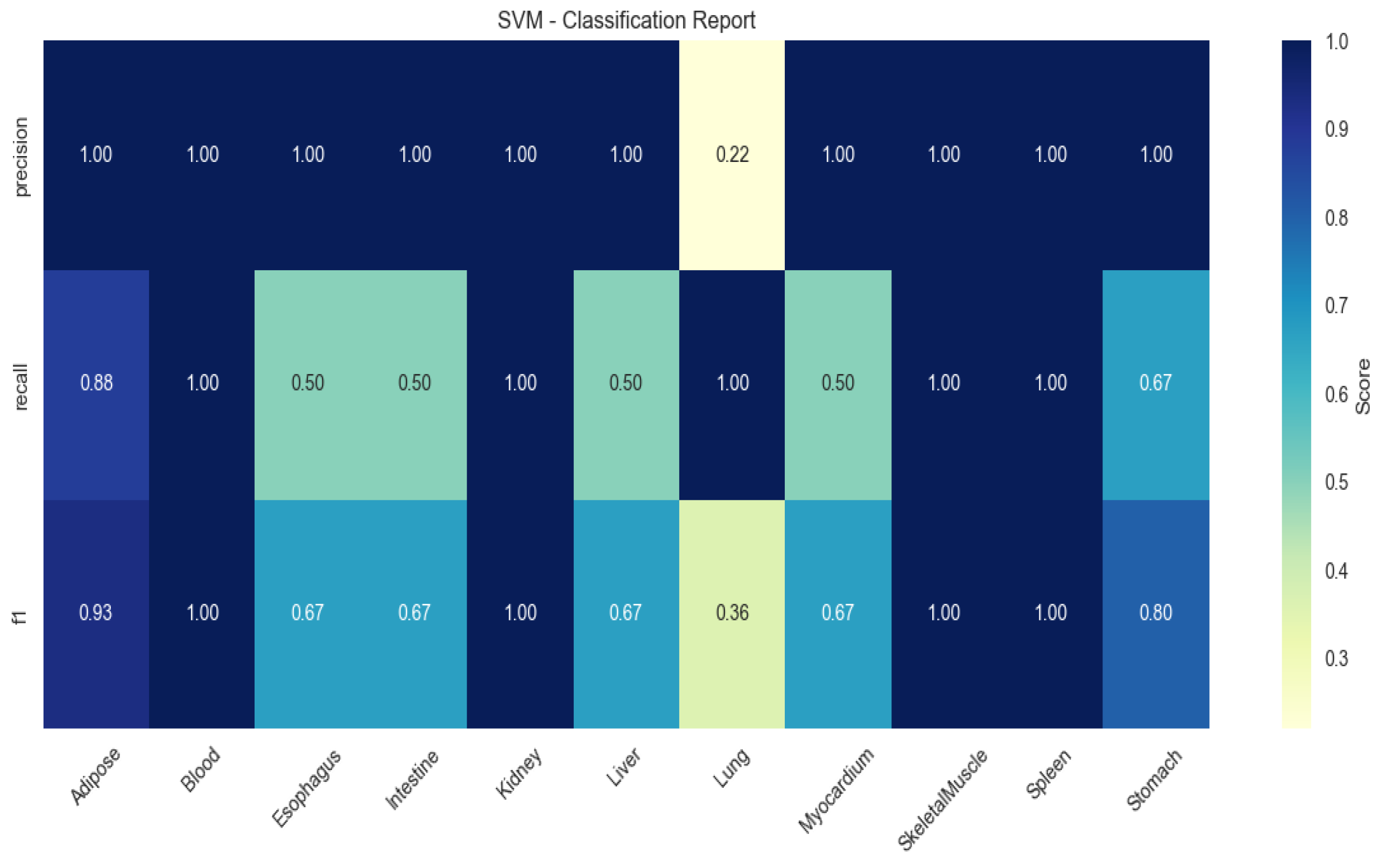

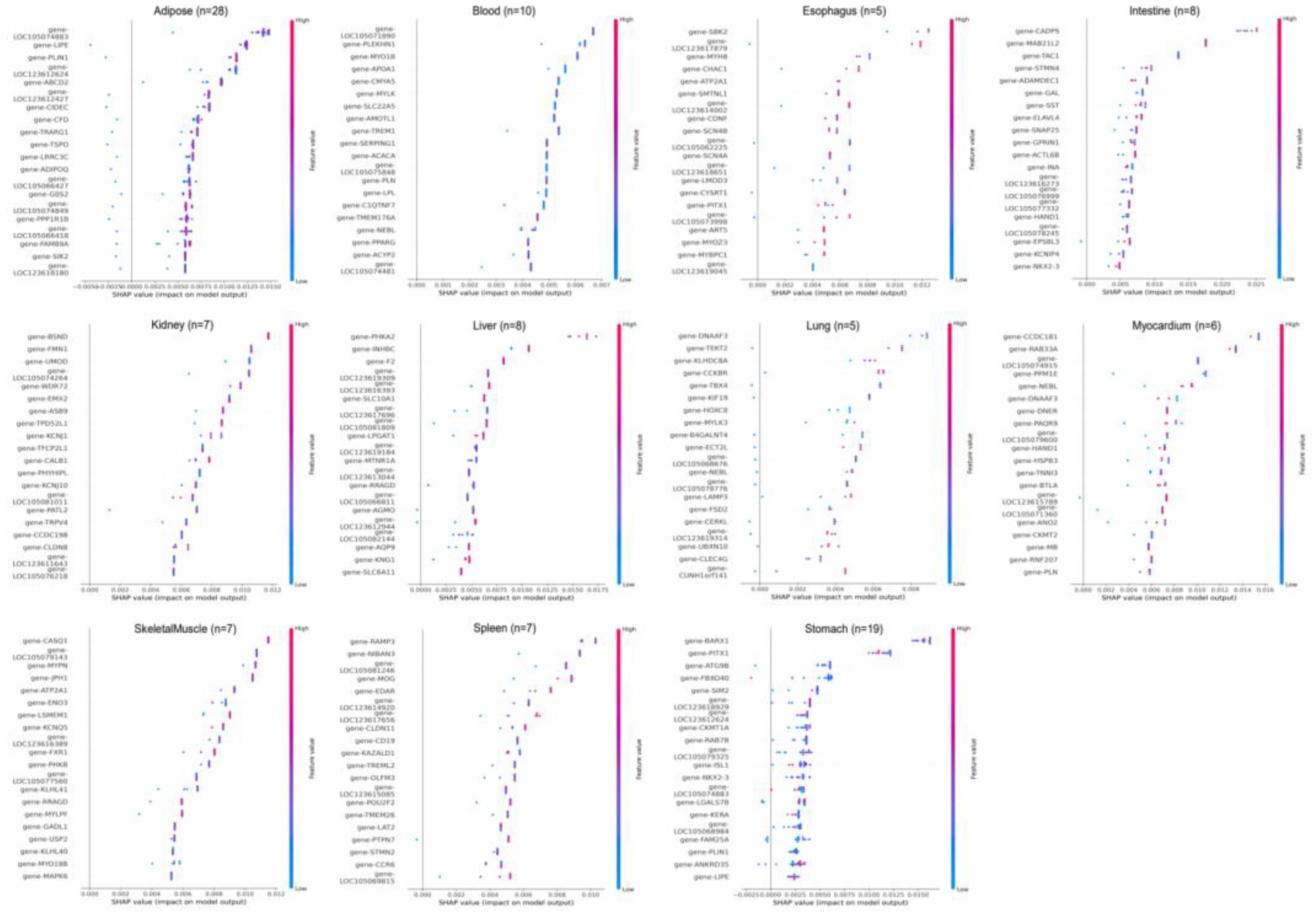

3.2. Tissue-Specific Gene Expression

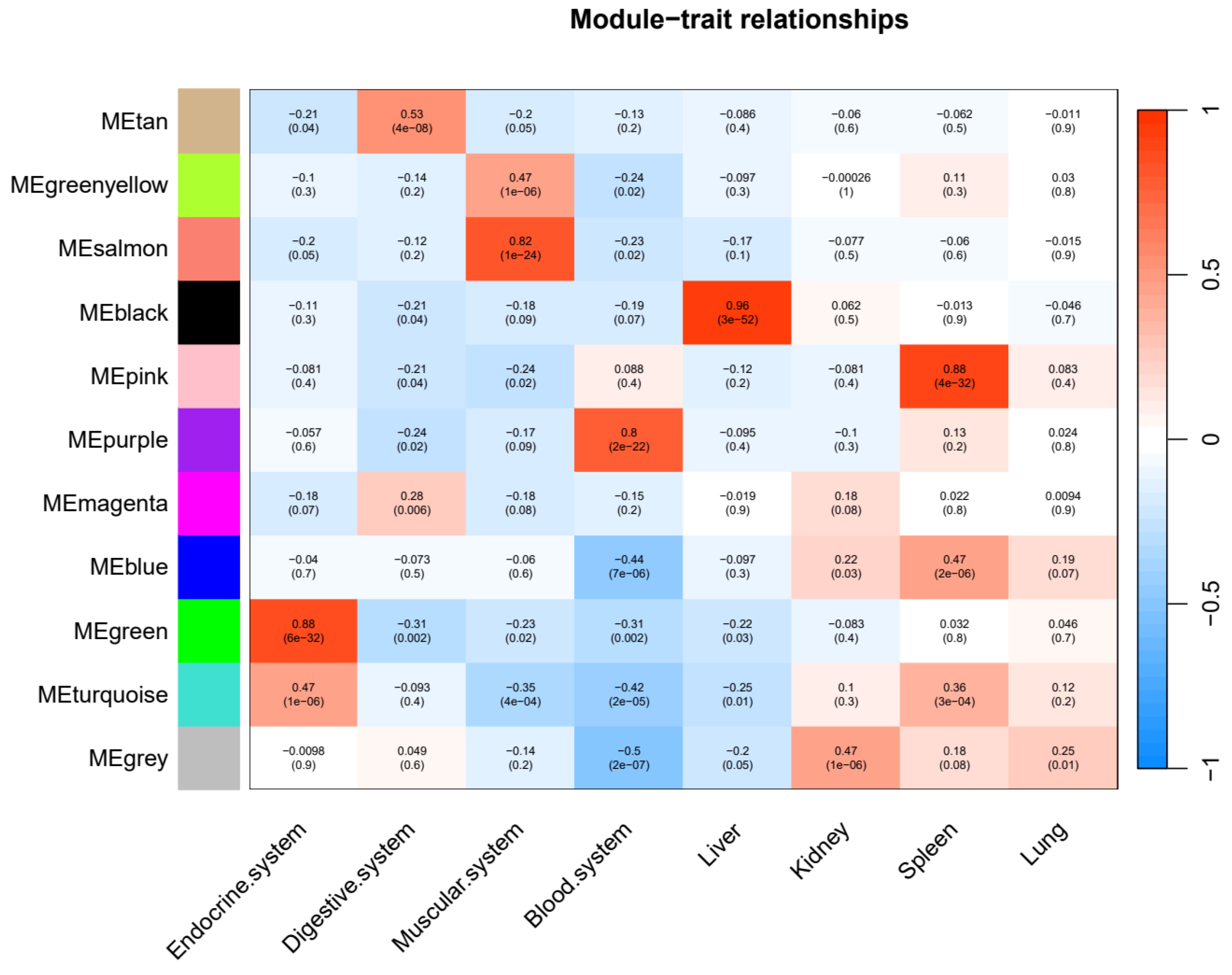

3.3. Co-Expression Network of Innate Immunity Genes Across Tissues

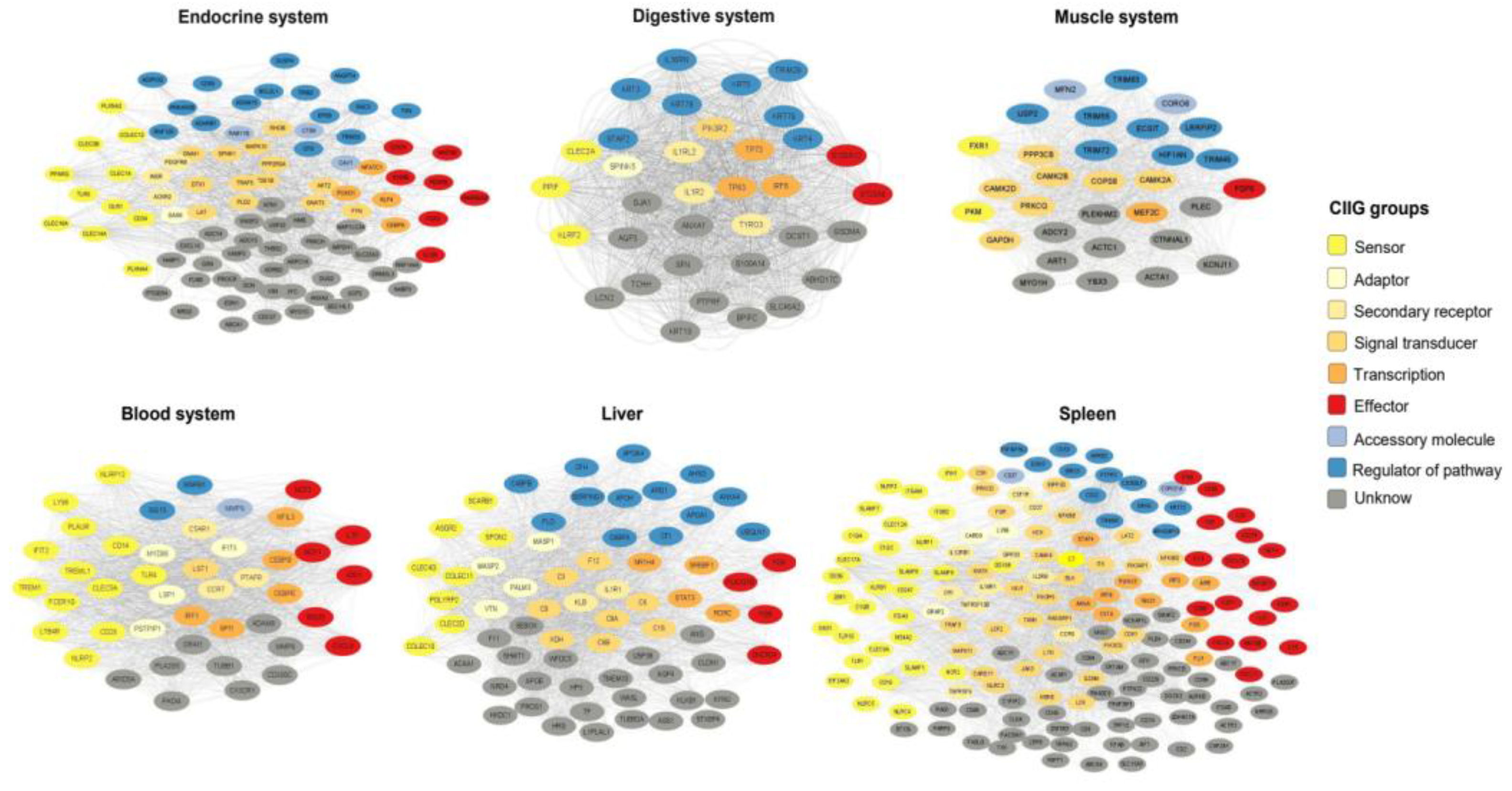

3.4. Tissue-Specific Innate Immunity Networks

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, H.; Guang, X.; Al-Fageeh, M.B.; Cao, J.; Pan, S.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, L.; AbuTarboush, M.H.; Xing, Y.; Xie, Z.; et al. Camelid genomes reveal evolution and adaptation to desert environments. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, J.L.; Godinho, R.; Brito, J.C.; Nielsen, R. Life in Deserts: The Genetic Basis of Mammalian Desert Adaptation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2021, 36, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussen, J.; Schuberth, H.-J. Recent Advances in Camel Immunology. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seida, A.; Hassan, M.; Abdulkarim, A.; Hassan, E. Recent progress in camel research. Open Veter- J. 2024, 14, 2877–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mass, E.; Nimmerjahn, F.; Kierdorf, K.; Schlitzer, A. Tissue-specific macrophages: how they develop and choreograph tissue biology. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.I.; Farber, D.L. Tissue-Resident Immune Cells in Humans. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 40, 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, C.D.; Xu, C.; Jarvis, L.B.; Rainbow, D.B.; Wells, S.B.; Gomes, T.; Howlett, S.K.; Suchanek, O.; Polanski, K.; King, H.W.; et al. Cross-tissue immune cell analysis reveals tissue-specific features in humans. Science 2022, 376, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Bartleson, J.M.; Butenko, S.; Alonso, V.; Liu, W.F.; Winer, D.A.; Butte, M.J. Tuning immunity through tissue mechanotransduction. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 23, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caputa, G.; Castoldi, A.; Pearce, E.J. Metabolic adaptations of tissue-resident immune cells. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Lai, G.C.; Yao, L.J.; Aung, T.T.; Shental, N.; Rotter-Maskowitz, A.; Shepherdson, E.; Singh, G.S.N.; Pai, R.; Shant, A.; et al. Microbial exposure during early human development primes fetal immune cells. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, M.; Aqil, A.; Saitou, M.; Gokcumen, O.; Masuda, N.; Fu, F. Gene communities in co-expression networks across different tissues. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2023, 19, e1011616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divate, M.; Tyagi, A.; Richard, D.J.; Prasad, P.A.; Gowda, H.; Nagaraj, S.H. Deep Learning-Based Pan-Cancer Classification Model Reveals Tissue-of-Origin Specific Gene Expression Signatures. Cancers 2022, 14, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisen, M.B.; Spellman, P.T.; Brown, P.O.; Botstein, D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 14863–14868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, M.; Johnston, R.L.; Foley, H.; MacDonald, S.; Kondrashova, O.; Tran, K.A.; Nones, K.; Koufariotis, L.T.; Bean, C.; Pearson, J.V.; et al. Verifying explainability of a deep learning tissue classifier trained on RNA-seq data. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, B.; Kumar, N.; Mukhtar, M.S. Network biology to uncover functional and structural properties of the plant immune system. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2021, 62, 102057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Kim, D.; Pertea, G.M.; Leek, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 1650–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. , Handsaker, B., Wysoker, A., Fennell, T., Ruan, J., Homer, N. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, A.; Garcia, S.; Herrera, F.; Chawla, N.V. SMOTE for Learning from Imbalanced Data: Progress and Challenges, Marking the 15-year Anniversary. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2018, 61, 863–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Liu, Z.; Dai, L.; et al. CRISPR-Cas9 Screening and Simulated Infection Transcriptomic Identify Key Drivers of Innate Immunity in Bactrian Camels. BMC genomics. n.d., in press.

- Kolberg, L.; Raudvere, U.; Kuzmin, I.; et al. g:Profiler-interoperable web service for functional enrichment analysis and gene identifier mapping. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W207–W212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarta, S.; Scoditti, E.; Carluccio, M.A.; Calabriso, N.; Santarpino, G.; Damiano, F.; Siculella, L.; Wabitsch, M.; Verri, T.; Favari, C.; et al. Coffee Bioactive N-Methylpyridinium Attenuates Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-α-Mediated Insulin Resistance and Inflammation in Human Adipocytes. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Noll, R.R.; Dueñas, B.P.R.; Allgood, S.C.; Barker, K.; Caplan, J.L.; Machner, M.P.; LaBaer, J.; Qiu, J.; Neunuebel, M.R. Legionella effector AnkX interacts with host nuclear protein PLEKHN1. BMC Microbiol. 2018, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohmura, G.; Tsujikawa, T.; Yaguchi, T.; Kawamura, N.; Mikami, S.; Sugiyama, J.; Nakamura, K.; Kobayashi, A.; Iwata, T.; Nakano, H.; et al. Aberrant Myosin 1b Expression Promotes Cell Migration and Lymph Node Metastasis of HNSCC. Mol. Cancer Res. 2015, 13, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisberg, S.P.; Ural, B.B.; Farber, D.L. Tissue-specific immunity for a changing world. Cell 2021, 184, 1517–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racanelli, V.; Rehermann, B. The liver as an immunological organ. Hepatology. 2006, 43, S54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronte, V.; Pittet, M.J. The Spleen in Local and Systemic Regulation of Immunity. Immunity 2013, 39, 806–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, N.; Parker, J.L.; Lugus, J.J.; Walsh, K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidball, J.G. Regulation of muscle growth and regeneration by the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.-F.; Zou, Q.-C.; Chen, L.-Z.; Liu, P.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Pan, H.-W. Identifying patterns of immune related cells and genes in the peripheral blood of acute myocardial infarction patients using a small cohort. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegnér, J.; Nilsson, R.; Bajic, V.B.; et al. Systems biology of innate immunity. Cellular Immunology. 2006, 244, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, K.; Khatoon, F.; Rashid, S.; Ali, N.; AlAsmari, A.F.; Ahmed, M.Z.; Alqahtani, A.S.; Alqahtani, M.S.; Kumar, V. Targeting hub genes and pathways of innate immune response in COVID-19: A network biology perspective. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 163, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, N.; Torabi-Parizi, P.; Gottschalk, R.A.; Germain, R.N.; Dutta, B. Network representations of immune system complexity. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2015, 7, 13–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inouye, M.; Silander, K.; Hamalainen, E.; Salomaa, V.; Harald, K.; Jousilahti, P.; Männistö, S.; Eriksson, J.G.; Saarela, J.; Ripatti, S.; et al. An Immune Response Network Associated with Blood Lipid Levels. PLOS Genet. 2010, 6, e1001113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casals, F.; Sikora, M.; Laayouni, H.; Montanucci, L.; Muntasell, A.; Lazarus, R.; Calafell, F.; Awadalla, P.; Netea, M.G.; Bertranpetit, J. Genetic adaptation of the antibacterial human innate immunity network. BMC Evol. Biol. 2011, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, N.; Walker, J.; Bontrager, A.; Zych, M.; Geisbrecht, E.R. A tissue communication network coordinating innate immune response during muscle stress. J. Cell Sci. 2018, 131, jcs.217943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).