Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

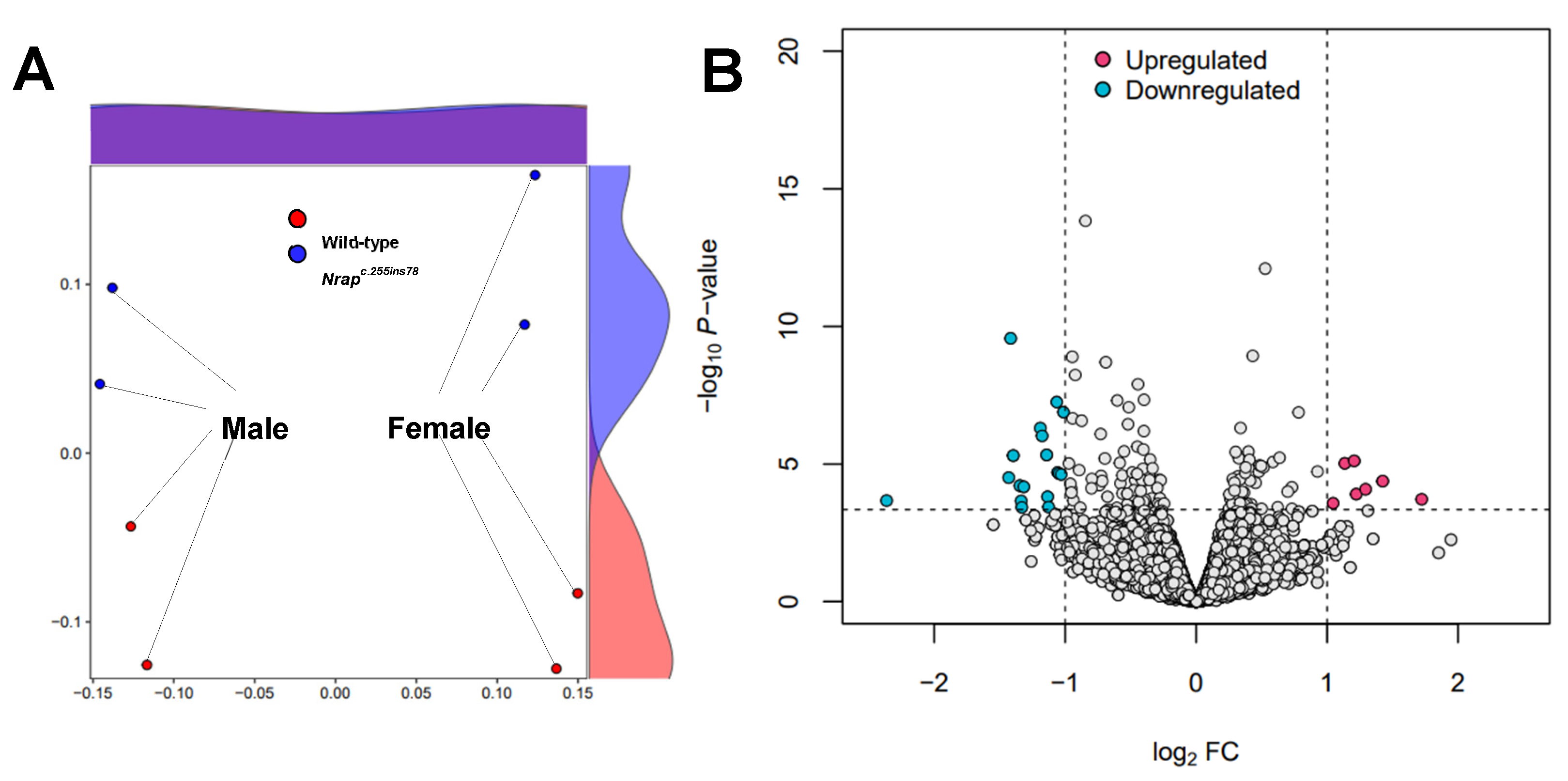

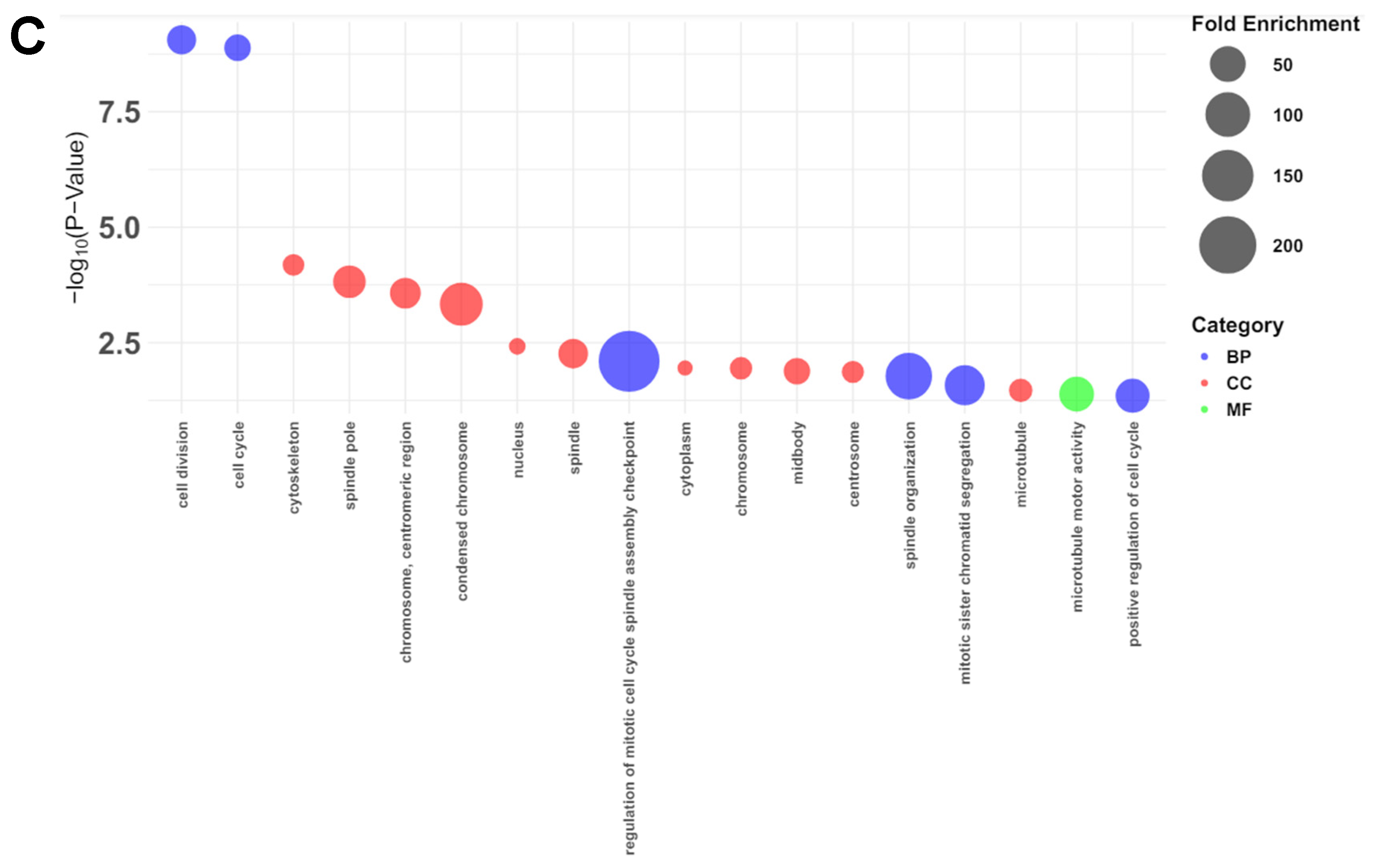

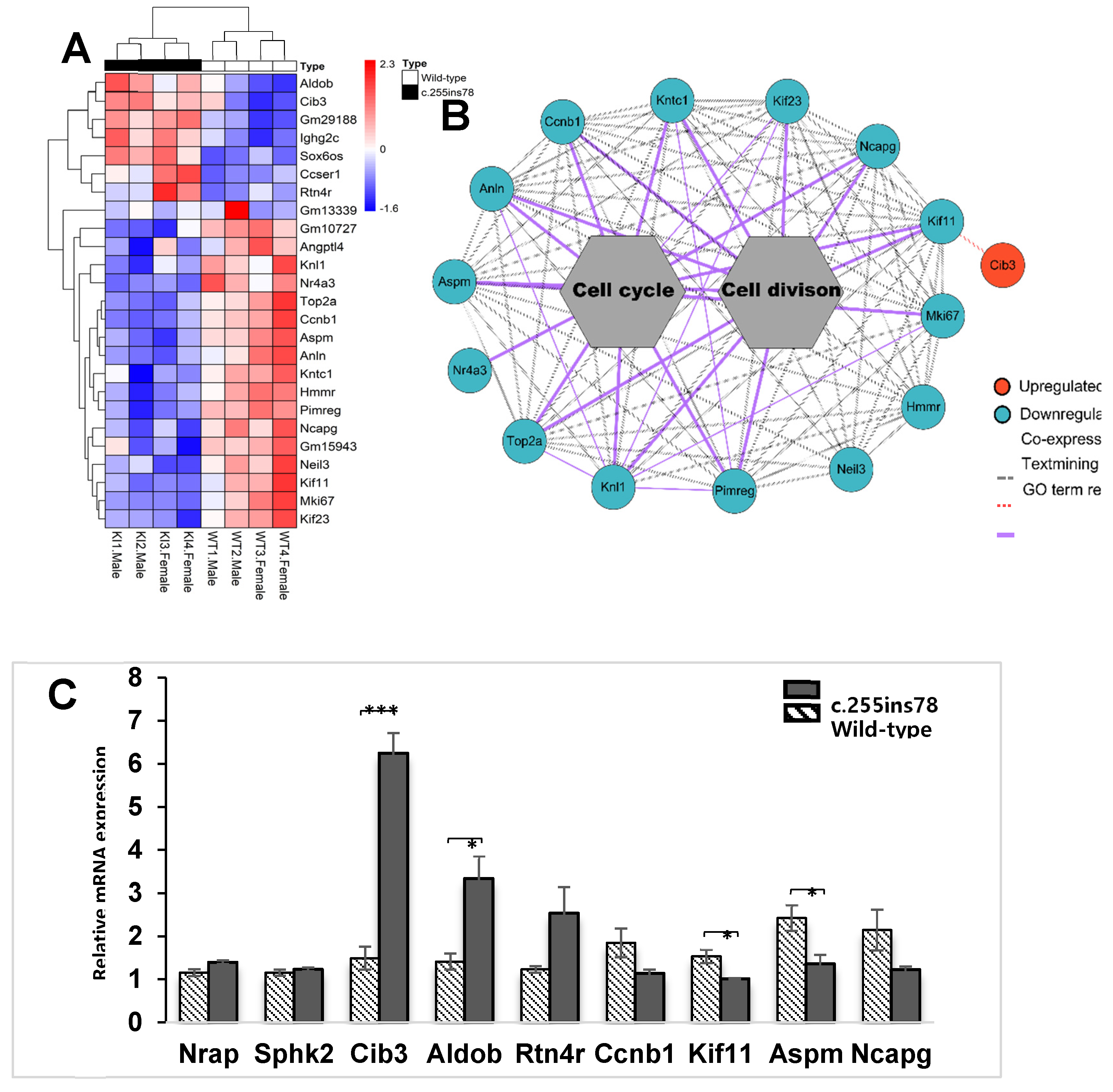

The first camelized mouse model (Nrap c.255ins78) was developed to explore how camels adapt to extreme environments. Previous studies showed that these mice exhibit a cold‐resistant phenotype, with increased expression of inflammatory cytokine‐related genes in the heart under cold stress. This study aims to build on prior research by analyzing the heart transcriptomes of Nrap c.255ins78 mice under non‐stress conditions to investigate the origins of inflammatory cytokine responses in the heart during cold exposure. For this purpose, RNA sequencing was used to analyze the heart transcriptomes of 12‐week‐old male and female Nrap c.255ins78 mice and control wild‐type mice. As a result, we identified 25 differentially expressed genes between wild‐type and Nrap c.255ins78 mice. Twelve of them were associated with the cell cycle and division, all consistently downregulated in Nrapc.255ins78 mice. The Cib3 (calcium and integrin‐binding protein) gene was significantly upregulated (FDR < 0.05; P < 0.001). These DEGs are linked to altered calcium dynamics in cardiomyocytes, maintaining homeostasis, and suggest that inflammatory cytokines during cold exposure may serve as an adaptive response. Our findings provide insights into the genetic mechanisms underlying temperature adaptation in camels and suggest pathways for enhancing stress resistance in other mammals.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

2.2. RNA-seq

2.3. Differentially Expressed Gene (DEG) Analyses

2.4. Gene Ontology (GO) Functional Enrichment Analysis

2.5. Interaction Network Construction

2.6. RT-qPCR Validation

2.7. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Data Processing and Transcriptomes

3.2. Functional Annotations

3.3. Expression Pattern and Validation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoter, A.; Rizk, S.; Naim, H.Y. Cellular and molecular adaptation of Arabian camel to heat stress. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandeel, M.; Al-Taher, A.; Venugopala, K.N.; Marzok, M.; Morsy, M.; Nagaraja, S. Camel proteins and enzymes: A growing resource for functional evolution and environmental adaptation. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 911511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Guang, X.; Al-Fageeh, M.B.; Cao, J.; Pan, S.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, L.; Abutarboush, M.H.; Xing, Y.; Xie, Z.; Alshanqeeti, A.S.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, Q.; Al-Shomrani, B.M.; Zhang, D.; Li, J.; Manee, M.M.; Yang, Z.; Yang, L.; Wang, J. Camelid genomes reveal evolution and adaptation to desert environments. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Lee, B.; Lim, B.; Uzzaman, R.; Jang, G.; Kim, K. Exploring the importance of predicted camel NRAP exon 4 for environmental adaptation using a mouse model. Anim. Genet. 2025, 56, e13490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, N.; Velapatiño, B.; Hung, A.; Cok, J. Cytokines expression in alpacas and llamas exposed to cold stress. Small Rumin. Res. 2016, 141, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, J.W.; Brenner, I.K.M.; Rhind, S.G. Cold exposure: human immune responses and intracellular cytokine expression. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002, 34, 2013–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, L.R. Molecular Biology of Thermoregulation Invited Review: Cytokine regulation of fever: studies using gene knockout mice. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 92, 2648–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugue, B.; Leppaänen, E. Adaptation related to cytokines in man: effects of regular swimming in ice-cold water. Clin. Physiol. 2000, 20, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Yan, Z.; Yan, W.; Xia, Q.; Zhang, Y. Cold exposure stimulates lipid metabolism, induces inflammatory response in the adipose tissue of mice and promotes the osteogenic differentiation of BMMSCs via the p38 MAPK pathway in vitro. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 10875–10886. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, D.Y.; Lim, B.; Kim, J.M.; Kil, D.Y. Integrated transcriptome analysis for the hepatic and jejunal mucosa tissues of broiler chickens raised under heat stress conditions. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Yu, X.; Portela Fontoura, A.B.; Javaid, A.; de la Maza-Escolà, V.S.; Salandy, N.S.; Fubini, S.L.; Grilli, E.; McFadden, J.W.; Duan, J.E. Transcriptomic regulations of heat stress response in the liver of lactating dairy cows. BMC Genomics 2023, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, B.; Kim, S.; Lim, K.S.; Jeong, C.G.; Kim, S.C.; Lee, S.M.; Park, C.K.; te Pas, M.F.W.; Gho, H.; Kim, T.H.; et al. Integrated time-serial transcriptome networks reveal common innate and tissue-specific adaptive immune responses to PRRSV infection. Vet. Res. 2020, 51, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, K.; Shi, Y.; Bai, X.; Chen, L.; Sun, W.; Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Jia, X.; Lai, S. Integrated Analysis of Transcriptome, microRNAs, and Chromatin Accessibility Revealed Potential Early B-Cell Factor1-Regulated Transcriptional Networks during the Early Development of Fetal Brown Adipose Tissues in Rabbits. Cells 2022, 11, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.W.; Sherman, B.T.; Lempicki, R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, J. Metabolic shifts during aging and pathology. Compr. Physiol. 2015, 5, 667–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mota-Rojas, D.; Titto, C.G.; Orihuela, A.; Martínez-Burnes, J.; Gómez-Prado, J.; Torres-Bernal, F.; Flores-Padilla, K.; Carvajal-De la Fuente, V.; Wang, D. Physiological and behavioral mechanisms of thermoregulation in mammals. Animals 2021, 11, 61733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torrent-Guasp, F.; Kocica, M.J.; Corno, A.F.; Komeda, M.; Carreras-Costa, F.; Flotats, A.; Cosin-Aguillar, J.; Wen, H. Towards new understanding of the heart structure and function. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2005, 27, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluteau, D.; Gilles, L.; Hilpert, M.; Antony-Debré, I.; James, C.; Debili, N.; Camara-Clayette, V.; Wagner-Ballon, O.; Cordette-Lagarde, V.; Robert, T.; et al. Down-regulation of the RUNX1-target gene NR4A3 contributes to hematopoiesis deregulation in familial platelet disorder/acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood 2011, 118, 6310–6320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costales, J.A.; Daily, J.P.; Burleigh, B.A. Cytokine-dependent and-independent gene expression changes and cell cycle block revealed in Trypanosoma cruzi-infected host cells by comparative mRNA profiling. BMC Genomics 2009, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dal Cortivo, G.; Dell’orco, D. Calcium-and Integrin-Binding Protein 2 (CIB2) in Physiology and Disease: Bright and Dark Sides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 73552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Bogstie, J.N.; Vogel, H.J. Biophysical and structural studies of the human calcium-and integrin-binding protein family: Understanding their functional similarities and differences. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2012, 90, 646–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Song, X.; Du, L.; Wang, C. Molecular characterization of the sheep CIB1 gene. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2009, 36, 1799–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, M.U.; Naik, U.P. Calcium- and integrin-binding protein 1 regulates microtubule organization and centrosome segregation through polo like kinase 3 during cell cycle progression. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2011, 43, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahl, C.R.; Means, A.R. Regulation of Cell Cycle Progression by Calcium/Calmodulin-Dependent Pathways. Endocr. Rev. 2003, 24, 719–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, E.; Samuel, S.M.; Sadiq, Z.; Kubatka, P.; Liskova, A.; Benacka, J.; Pazinka, P.; Kruzliak, P.; Büsselberg, D. Anti-cancer agents in proliferation and cell death: The calcium connection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 12017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamniuk, A. P.; Vogel, H. J. Calcium- and magnesium-dependent interactions between calcium- and integrin-binding protein and the integrin αIIb cytoplasmic domain. Protein Sci. 2005, 14, 1429–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolau, S.; Dasgupta, A.; Dasari, S.; Charlesworth, M. C.; Johnson, K. L.; Pandey, A.; Doles, J. D.; Milone, M. Molecular signatures of inherited and acquired sporadic late onset nemaline myopathies. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2023, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermij, S. H.; Abriel, H.; Van Veen, T. A. B. Refining the molecular organization of the cardiac intercalated disc. Cardiovasc. Res. 2017, 113, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, K.; Strong, P. N.; Dubowitz, V.; Dunn, M. J. Calmodulin-binding profiles for nebulin and dystrophin in human skeletal muscle. FEBS Lett. 1988, 234, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuen, M.; Ottenheijm, C. A. C. Nebulin: big protein with big responsibilities. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2020, 41, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooglugt, A.; van der Stoel, M.M.; Boon, R.A.; Huveneers, S. Endothelial YAP/TAZ Signaling in Angiogenesis and Tumor Vasculature. Front. Oncol. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meinhold, M.; Verbrugge, S.; Shi, A.; Schönfelder, M.; Becker, L.; Jaspers, R. T.; Zammit, P. S.; Wackerhage, H. Yap/Taz activity is associated with increased expression of phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase that supports myoblast proliferation. Cell Tissue Res. 2024, 395, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tóth, M.; Wehling, L.; Thiess, L.; Rose, F.; Schmitt, J.; Weiler, S. M. E.; Sticht, C.; De La Torre, C.; Rausch, M.; Albrecht, T.; Grabe, N.; Duwe, L.; Andersen, J. B.; Köhler, B. C.; Springfeld, C.; Mehrabi, A.; Kulu, Y.; Schirmacher, P.; Roessler, S.; Breuhahn, K. Co-expression of YAP and TAZ associates with chromosomal instability in human cholangiocarcinoma. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W. H.; Chi, J. T. Hippo pathway effectors YAP/TAZ as novel determinants of ferroptosis. Mol. Cell. Oncol. 2020, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Wang, K.C.; Meng, Z. Mechanoregulation of YAP and TAZ in Cellular Homeostasis and Disease Progression. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halder, G.; Dupont, S.; Piccolo, S. Transduction of mechanical and cytoskeletal cues by YAP and TAZ. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).