1. Introduction

Colibacillosis is a primary systemic pathologic disease caused by Avian Pathogenic

Escherichia Coli (APEC). The pathogen is often associated with several risk factors, including inadequate parental innate immunity, high stocking density, suboptimal ventilation, and poor sanitation. These conditions promote the horizontal transmission of APEC through faecal contamination and vertical transmission via eggs [

1]. After entering the body, APEC spreads hematogenously and causes impairment of the bloodstream by its adhesion virulence factor. Each adhesion secreted by the bacteria is compatible with almost all receptors across chicken organs. After the adhesion process, the bacteria will secrete toxins to colonise the cell membrane and destroy its energy resources, leading to cell death.

The clinical signs typically appear between 3 and 5 weeks of age or progress as the agent infects. The disease often presents initially as respiratory tract and air sac infections (airsacculitis), which can progress to more localised infections and systemic infection [

2]. Systemic infection, is characterised by lethargy, anorexia, and dehydration [

3,

4]. The systemic manifestations are profound, causing significant disturbance in the circulatory system, which leads to oedema changes in specific organs (for example, hepatomegaly and splenomegaly) [

5].

The spleen is the secondary lymphoid organ that plays a vital role in regulating the immune system. Although this organ is not the primary target for bacteria and the damage is less life-threatening than that to the air sac and heart, the effects of APEC warrant highlighting. Damage to the spleen leads to immunosuppression. For this reason, the histopathology structure of the spleen is worth identifying because it can depict the progression of APEC systemic infection. It can be identified microscopically, starting from the damage to the vascular wall, and through the infiltrated lymphoid [

6]. If the lymphoid structures are depleted, it can be an indicator of a higher severity infection in the chicken. Consequently, it increases susceptibility to other infectious diseases [

7].

Since colibacillosis is a highly pathogenic disease, it has caused substantial monetary losses, estimated at 20 trillion rupiah. The significant loss is primarily due to lower carcass quality, reduced carcass yields, and increased culling rates [

8]. To prevent this burden, local farmers commonly use antibiotic drugs because they are relatively affordable and accessible without a prescription, such as tetracyclines, sulfonamides, and aminoglycosides. A study in Sukabumi, Indonesia, reported that the

E. coli isolated from clinical colibacilosis cases were resistant to oxytetracycline, enrofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and tetracycline, with molecular analysis revealing that the resistance genes were highly increased [

9]. Thereby, multi-drug resistance is pursued as an issue in controlling colibacillosis.

In this urgency, rise alternative treatments extracted from herbal plants. Java cardamom (

Amomum compactum Sol. Ex Maton) is a plant originating from the Java Island, Indonesia. The seeds contained an active compound with antibacterial bioactivity and anti-inflammatory properties, specifically 2,4-dihydroxy-1,8-cineol. Another antibacterial compound from herbal plants is curcumin, which can be extracted with ethanol from turmeric (

Curcuma domestica Val). Turmeric also has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. It can protect against damage in spleen cells and promote cell longevity [

5]. The effectiveness of curcumin in combination with other herbal antibiotic compounds for treating colibacillosis has been promising [

10,

11,

12].

Among those herbs, Java cardamom extracts are considered to have a higher anti-bacterial activity than curcumin extracts. It is because the antibiotic activity works differently. For 1,8-cineol, it acts as a bactericidal by disturbing the outer membrane of bacterial cells, thus causing cell lysis and bacterial death [

13]. Conservatively, curcumin may not inhibit

E. coli growth due the characteristics of the bacteria themselves. Gram-negative bacteria are resistant to curcumin due to the high permeability of their cell wall structure [

14]. The cornerstone of the study is to assesses the combination of curcumin and 1,8-cineol with its effect towards immune organ, which may yield better results than a standalone approach.

2. Materials and Methods

While this study emphasized broiler spleen histopathological analysis, two main primary steps had previously been conducted to collect the material for the experiment. First, the collection of herb extracts and bacterial suspension, then it followed by an in vivo experimental study design. The following methods and results will be explained briefly below.

2.1. Herbs Extractions

The Java cardamom and turmeric extraction processed according to previous study [

15]. The Java cardamom seeds were extracted with a steam-distilled process for six hours. The mixture of distilled oil was separated from water using a petroleum ether extraction method. The residual water was removed with anhydrous sodium sulfate until the final process of Javanese cardamom essential oil (JCEO), resulting in a density of approximately 0.98 g/mL.

For the turmeric rhizome, the study used a dried turmeric rhizome that dissolved in 75% ethanol using a 500 mL Erlenmeyer flask at room temperature (22-26°C) [

16]. The turmeric powder and solvent were homogenized twice for five minutes and macerated for 48 hours. The result was evaporated using a rotary vacuum evaporator at 60°C to remove the ethanol. This extraction process obtained 20.17 grams of dried turmeric ethanol extract (DT).

Both extracts were checked for their phytochemical compounds using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and secondary metabolism components. The result was that the highest bioactive compound for JCEO is ethanol, also known as 1,8-cineole. The DT revealed the presence of phenols, tannins, steroid, and triterpenoids [result attached in

Supplementary Figures S4 and S5).

2.2. Bacterial Suspension

The

E. coli O78 bacteria culture was ordered from the Centre of Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory in Bogor, Indonesia. The reasons for using this typical strain of

E. coli were based on the common APEC serotypes found in broiler chickens. A study revealed that one of the most prevalent

E. coli serotypes detected in broilers was O78. At the same time, the bacteria also display notable resistance to penicillin and cefixime, but low resistance to norfloxacin and the quinolone group [

17]. A confirmation test for

E. coli was performed using the Congo red dye agar test to differentiate between invasive and non-invasive

E. coli strains in the experiment. After ensuring the pathogenic

E. coli strains, they were cultured in Nutrient Agar at 37°C for 24 hours.

To create the suspension, the bacterial culture was dissolved in a saline solution (0.9% NaCl) and then diluted in a nutrient broth medium to a final volume of 10mL, resulting in a desired colony count of approximately 1-2 × 10

8 CFU/mL [

18]. Herby, the bacterial suspension was used in an antibacterial test, utilising the minimum inhibitory zone and minimum inhibitory concentration, against antibiotics, herbal mixtures, and individual herb groups.

2.3. Animal Experiment Design

The in vivo experiment involved 72 Cobb-strain day-old broiler chickens (Galus gallus). The chicks weighed 920 - 930 grams and were kept in separate cages based on the experiment group design for five weeks. We set the cage temperature on brooding recruitment for the first week (30 - 31°C), then reduced it by next week until reaching 23 to 25 °C. The LED lamps provided lighting with an intensity of 20-30 lux.

The study used randomized design methods to determine five treatment groups with four replications. There was a total of eight groups: two control groups (C1 as a negative control group and C2 as the positive control group, which was only infected with

E. coli O78 suspension) and six treatment groups challenged with an

E. coli O78 suspension, with the dose details presented in

Table 1. Bacterial suspension was injected intraperitoneal (IP) with infectious dose in 10

8 CFU/ml/chickens at 28 days old, while the herbal extract was administered orally via drinking water from 7 days old. The chickens were terminated at 35 days old using the Halal Guidance technique.

2.4. Histopathology Preparation

The organ materials collected for the histopathology study included the intestine, lungs, heart, spleen, liver, bursa fabricii, and kidney. We sent the sample to Subang Veterinary Diagnostic Centre for histopathology preparation. First, the organs were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 hours. The preparation was dehydrated with 70% ethanol for 2 hours before washing with toluene. The organs are embedded in paraffin wax, cut into 5-µm-thick sections using a microtome, and placed on glass slides [

19]. They were then stained with a hematoxylin and eosin stain. The stained tissue section was examined under a digital microscope (Zeiss Apotome2), and scoring was performed using the ImageJ application.

2.5. Spleen Organ Scoring System

Five primary histopathological lesions in the spleen were chosen to match the

E. coli systemic pathogenesis explained in

Table 2. These lesions involved the abnormal structure of blood walls and the in-depth lymphoid structure. There will be a total of 20 lesions in each group based on the four repetitions and five lesion assessments. Histophotometric analysis was performed using ImageJ to quantify the percentage of area affected based on the identified lesion. These tools help to avoid observer bias and maintain consistency throughout the observation process. Each treatment group required 10 fields of view per sample to maintain a consistent data between groups [

20]. The area affected (%) was then converted into a scoring range using ordinal scales. Scoring using an ordinal scale is frequently used by researchers for histopathology assessment [

21]. Ordinal scale can indicate the order of progression or change in severity.

Furthermore, severity score will use the following reference [

24]: score 1 for fewer changes (<20% area of affected), score 2 for moderate changes (20 - 40% area of affected), 3 scored as high changes (40 - 60% area affected), 4 for severe changes in up to 60-80% of area affected and 5 for highly extreme changes. The scoring distribution was assessed using the D’Agostino-Pearson normality test. Each group was significantly subjected to an ordinary one-way ANOVA statistic and multiple group comparisons by Tukey’s post hoc test. The results yielded a set of decisions with p < 0.05, considered statistically significant. All data and tables presented were obtained using GraphPad Prism for Windows, version 10.

3. Results

3.1. Data Analyses

Every pathological lesion was calculated from ten views of each individual in the group. The average score of severity grade from the least affected (1) to the most severe (5) is presented in

Table 3.

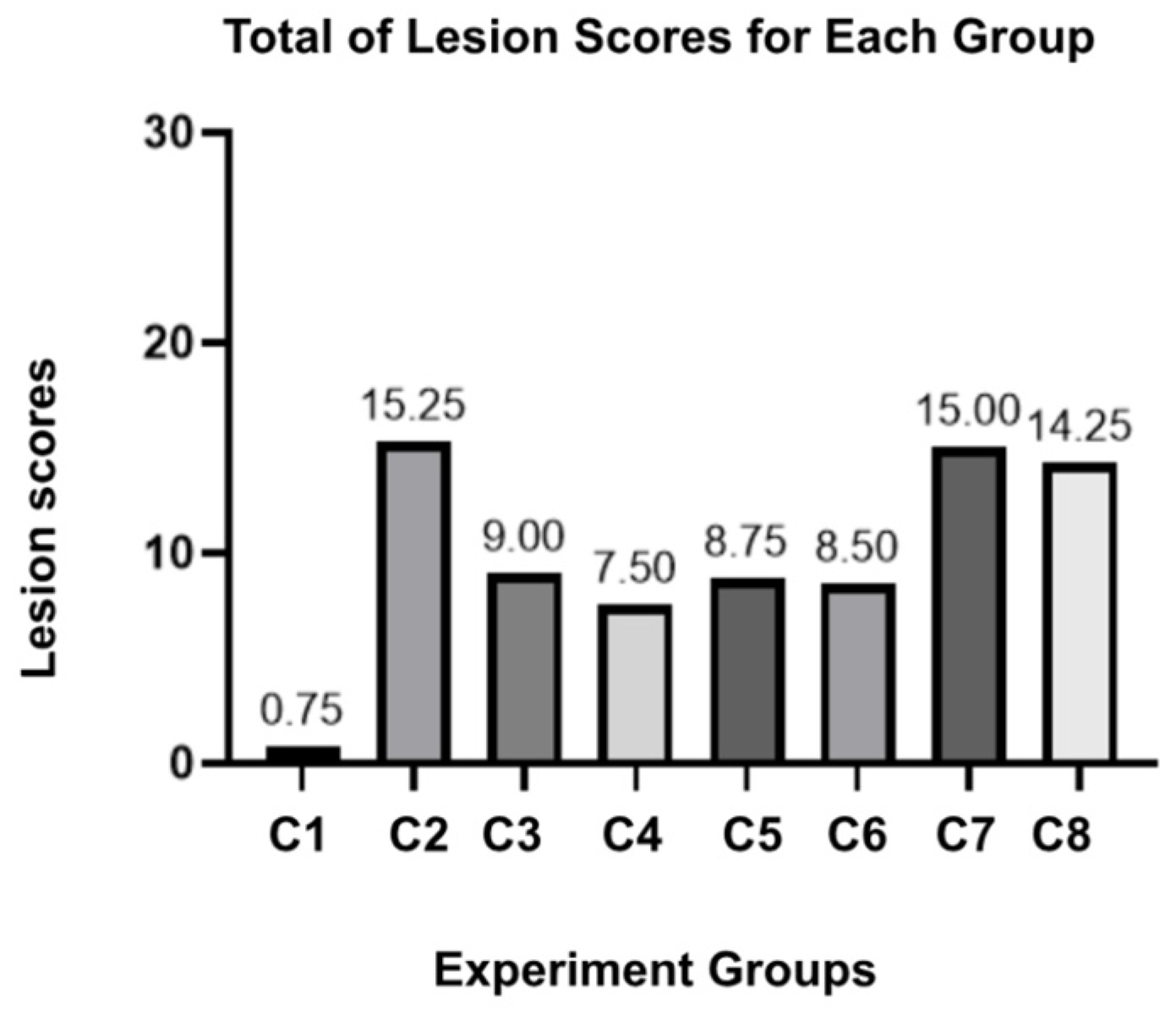

The result stated for group C2 had the highest score across the lesion parameters, indicating a severe and adverse effect of E. coli O78 on the spleen without any intervention. For the herbal combination group, C3 and C4 proposed better scores, especially since the structural damage (necrosis and lymphoid depletion) was considered the lowest among the other groups. The standalone doses of JCEO in C5 and C6 did not show a different pathological score; this result also remains non-significant in the statistical multi-comparison analysis (p-value > 0.999). In contrast, C7, which was preserved as a single dose of DT, yielded a high number of pathological lesions among other herbal groups, but still maintained tolerable scores below the positive control group. Lastly, for the antibiotic group (C8), the score was not greater than the herbal treatment.

The scores for vasculitis, necrosis, and lymphoid depletion were notably significant (p-value < 0.0001), while congestion and degeneration cells showed no significant results across the groups using one-way ANOVA analysis (see

Supplementary Table S2). We also summarized the total lesions observed in

Figure 1. The maximum number of lesions that can be acquired is twenty lesions for each group. C2 expected to be the highest lesion score, followed by the C7 and C8 groups. While the parameters may exhibit different tendencies between groups, the spleen damage can be proved microscopically.

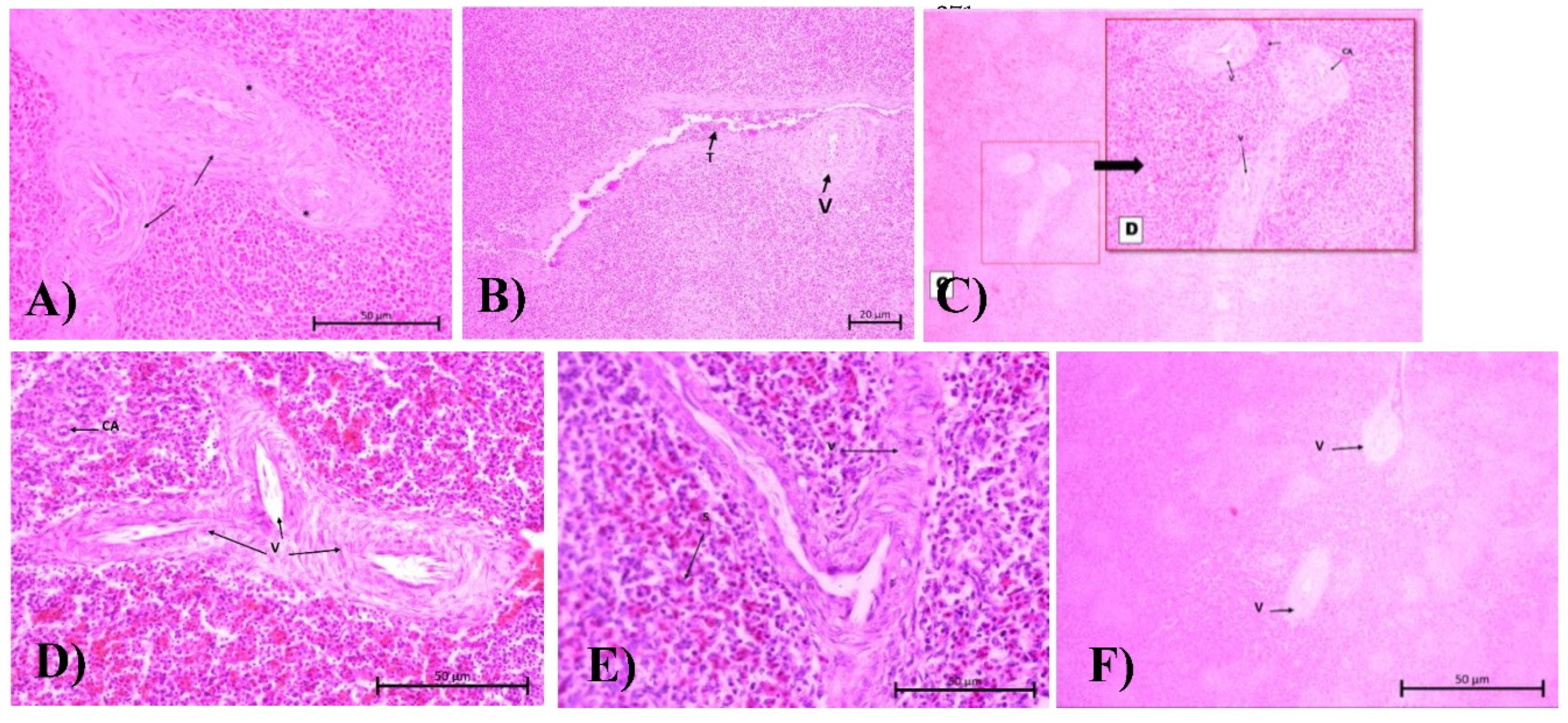

3.2. Histopathology Assessment

A comparison is made between the broiler spleen structures of all groups at low magnification (refer to

Supplementary Figure S1 for detailed images). C1 proceeds as a standard broiler spleen structure, depicting a clear section between the red pulp (RP) and white pulp (WP), with a compact splenic artery (A) vessel wall. The WP is a combination of the central arteriole, splenic follicles, periarterial lymphoid sheath (PALS), and marginal zone. The structure is dense, basophilic, and appears more bleached with H&E stains because it contains active B cells and macrophages.

Meanwhile, the RP is collocated with parenchyme and venous sinuses, which act as an empty vascular space lined by endothelial cells. The sinus venosus functions to filter red blood cells (RBC). The red pulp contains macrophages, granulocytes, plasma cells, mast cells, and RBCs and appears more reddish in the stain. This may be mistaken for a haemorrhage lesion (a bleeding out from the vascular wall) within the RP sinusoid. For a more discerning deduction, the lesion was then removed from the analysis indicator to ensure an unbiased judgment.

The experimental result, as shown in the C2 group (

Figure S1-B), indicates that the WP and RP structures appear coalescent. It is because the cells are undergoing degeneration so they cannot maintain their dense structure. The blood vessel was heavily affected, resulting in a narrowed lumen. The improvement was seen in the C3 and C4 groups. The integrity of the spleen structure is well visualized. In C5 and C6, a single dose of JCEO provides a better structure for WP and RP than the C7. All groups exhibited a moderate vasculitis score. For antibiotic treatment (

Figure S1-H), some features of WP and splenic follicles (F) were visible, and based on the scoring, the severity of vascular damage was less affected than in C7.

4. Discussion

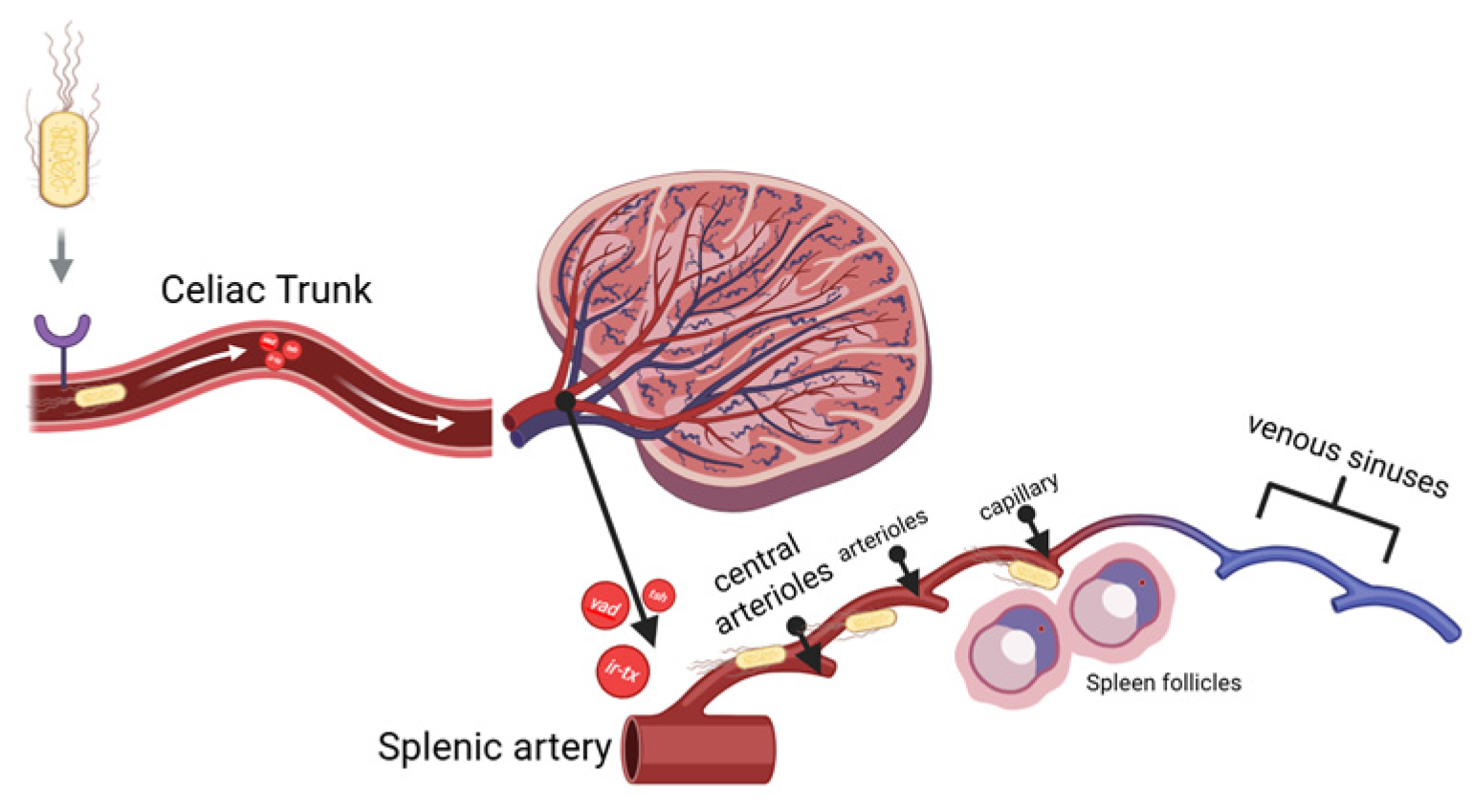

4.1. Systemic Route of APEC Infection to the Spleen and Its Effect Towards Vascularisation

As is stated previously in the introduction section, the spleen anatomical structure favours APEC systemic infection because of its adhesion ability. APEC was injected intraperitoneally and spread through the omental cavity and capillaries. The adhesins, for example,

yad,

ecp, tsh, and the iron-binding toxin, find their receptors in endothelial cells and RBCs. As they attach, they can damage endothelial cells in blood vessels, leading to vacuolization and loss of intercellular adhesion between cells. When the bacteria finally reach through the splenic artery (A), they branch into the central arteriole (CA), which divides into smaller vessels, including central arterioles, sheathed arterioles, and capillaries. These small blood vessels are located entirely within the WP and RP. The septicemia is simplified and visualized in

Figure 2 below.

Tsh toxin is a one of by-product from APEC adhesion. It affects the degradation of the extracellular matrix (ECM), specifically collagen factor IV, resulting in damage to the vascular wall [

25]. An

iron-binding toxin is the endotoxin that binds to haemoglobin causes erythrocyte lysis and allowing bacteria to escape from the bloodstream and spread within the inner structure of the spleen. This process occurs more quickly when the bacterial suspension is injected. These results trigger an immune response towards

E. coli antigens, which is recognised by DAMPs signal transduction to mast cells, macrophages and dendritic cells. The vascular permeability will increase to activate lymphocytes at the infection site. The infiltration of fibrinogen into the tissue causes a thickening of the tunica media and adventitia in blood vessels as an effort to replace the damaged endothelial cells [

26]. Congestion also results from the lysis of blood cells and the infiltration of macrophages. These lesions are well described in C2, C5, and C7 groups (

Figure 3).

The results of the ANOVA test on vasculitis parameters were highly significant (p < 0.0001, refers to S

upplementary Table S1). The C2 score had the highest vasculitis score of 4.250 among all other test groups, as the purpose of mimicking the E. coli pathogenic systemic route was achieved as intended. In

Figure 3B, the vasculitis is depicted by fibrosis and a thickened tunica adventitia wall, causing it to coalesce with other vessels (V). Higher magnification reveals the surrounding fibrin network (indicated by the black arrow), vacuolated endothelial cell (black stars), and narrowed blood vessels lumen. The vasculitis condition was observed to be better in the C3, C4, and C6 groups as indicated by a less thickened wall. There are no significant differences between the herbal groups. However, C7 showed a more pronounced progression of vascular damage.

The issue with C7 is the metabolism process of curcumin, which involves several steps of digestion and the bioactivity attribute itself. First, curcumin's mechanism of action is by disrupting biofilm formation and inducing prolonged bacterial death, whereas 1,8-cineol exhibits a more direct and bactericidal mechanism against bacterial cells. Several studies have found that curcumin's limited antibacterial activity is attributed to its unstable chemical structure, resulting in decreased pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties [

27]

Secondly, the drug formulation determines the metabolism process of curcumin. Curcumin emulsion (oil-in-water) formulations are better absorbed than oil-based formulations and maintain curcumin stability in the body even under neutral and alkaline pH conditions [

27]. Its nature attribute is unstable, degrading into other components such as vanillin which reduces the pharmacodynamic half-life time. In the future, a more effective formulation may be developed to enhance its mechanism efficiently.

The reason for vascular lesions was observed across all groups is because the oral administration of herbs and antibiotic has a long pharmacokinetic window before reaches the target organ. Meanwhile, APEC spreads more rapidly through hematogenous infection following peritoneal injection. Vasculitis parameter result can confirm that APEC infections progress systematically and reach the spleen.

4.2. The Impact of APEC Toxins on the Spleen Inner Structure

We now understand how APEC can easily penetrate the spleen structure. To assess the severity of infection, the spleen’s inner structure must be observed thoroughly. Pathologically, cells can undergo two different states of injury when exposed to antigens. First is a non-lethal injury known as cell degeneration. Cell degeneration is a pathological condition that causes changes in the structure of the cell's cytoplasm. This injury results in an abnormal accumulation of material in the cytoplasm [

26]. The cell might be reversibly improved if the pathological stimulus is reduced or other substances are added that reduce cell damage, such as antioxidants and anti-inflammatory agents.

The other injury is a cell necrosis. Necrosis refers to the changes that occur after cell death or irreversible damage. Necrotic changes in the spleen are characterised by swelling of cell organelles, changes in the nucleus to an accumulation of nuclear debris in the cytoplasm, eosinophilic karyohecticity, and abundant karyolysis. Additionally, the cell may also be accompanied by inflammatory cell infiltration, haemorrhage, and loss of the cytoplasmic membrane [

28].

These types of pathological changes were found to vary in APEC infections. The mechanism of cell degeneration is triggered by the APEC

Stx2 toxin (verotoxin-2), subA-B toxin, and VAT [

23]. SubA has catalytic activity and is responsible for the cytotoxic effect. SubB binds to receptors on the cell membrane surface, facilitating the entry of toxins into the cell. VAT alters the cell cytoskeleton and decreases epithelial permeability. Both toxins induce cell vacuolization. This results in the movement of extracellular matrix into the cell, causing the cell to swell like a cloud and the cytoplasm to appear pale/opaque in H&E staining. Another virulence factor of APEC includes hemolysin, chick-lethal toxin, and CNF. This virulence is responsible for necrotic spleen cells [

23].

Histopathological results illustrate the differentiation between the various groups of spleen structures (see

Supplementary Figure S2). The negative control groups (C1) exhibit the typical structure of the chicken spleen. The WP have a dense condition, characterised by lymphoid follicles containing lymphocyte cells with intact marginal zones. The central arteriole should be inside the PALS, which is surrounded by mature T cells. This is crucial since its function is for lymphocyte cells maturation and the formation of antibodies.

The RP zone needs to be able to identify the two constituent components: the splenic cord of Billroth and the sinus venosus. It is characterised by an empty, flattened cavity, with the tip fused to the other venous sinuses. Damaged RBCs do not pass through the sinusoidal filtration and accumulate, eventually being ingested by macrophages circulating in the spleen.

Statistically, there are no significant differences between the treatment groups and the positive control group in terms of cell degeneration (p-value > 0.05). However, the observation suggests that these cells have changed. In infected groups, the visible alterations include vacuolar degeneration and cytoplasmic degeneration. The cells appear cloud-like due to the influx of ions, plasma fluid, and water into the cytoplasmic matrix, causing the cells to expand and swell, producing a cloudy, central stain known as ghost cells (

Figure S2).

Meanwhile, for necrosis, there is a significant difference in the affected area between each of the treatment groups. The most severe necrosis condition was shown in C7 and C8 with necrosis scores of 3 ± 1.826 and 4 ± 0.816, respectively. The comparison of necrosis conditions between the C8 group and both herbal groups was highly significant (p value = 0.0007). The WP cells, especially the lymphocyte nuclei in C7 and C8, were observed with karyohexis. It can be seen from the loss of the nucleus and also the membrane of the spleen cell wall, causing the cells to appear fused in the cytoplasm, which are colored pale pink (blue stars).

All herbal treatment groups showed insignificant differences in necrosis scores compared to the negative control group. This indicates that the necrosis condition of the spleen organ in the herbal group was relatively close to the normal histology of the broiler spleen. Assessing lymphocyte cell injuries is essential because it interprets the density of the lymphoid follicle in the WP, thereby promoting long-term immune defense in the chicken.

When there are too many lymphocytes cells undergoes degeneration or necrosis, it will leads to the follicle depletion. This is a condition where there is an injuries of lymphocytes cells within the follicle, consequently decreased size of the periarteriolar lymphoid sheath, and the size of the follicle inside the white pulp. It can presence a few or no germinal centers, a complete loss of the marginal zone and irregularity of the follicle shape [

29]. If the severity increases, the zone between WP and RP will be coalescent and indistinguishable.

C1 (see

Figure S2 A-C) represents the references for detailed features in the WP and RP structure. The difference between the C2 group is that the lymphocytes are necrotic within the follicles, as well as in the PALS zone and RP (

Figure S2 D). Cells in the PALS zone and red pulp exhibited morphological changes, with fluid accumulating in the cytoplasm and pushing against organelles within the cells, resulting in swelling. In the herbal group, C3 and C4 show the best follicle condition compared to the other groups, with the scores under <1% area affected. These can be seen by the integrity of the marginal zone, which is well separated into WP and RP.

In contrast, the morphology in C5, C6, and C7 (see

Figure S2 E-G) shows that the marginal line separating the red pulp and white pulp is no longer visible. The follicles are filled with nuclear debris and cell cytoplasm, indicating that the lymphocyte cells are experiencing necrosis and degeneration. The central arteriole in the group exhibits cell wall damage and tunica thickening, even though the difference is considered insignificant. For the antibiotic groups, the results are similar to those of the negative control. The follicle is visible with several necrotic lymphoid cells around it.

The significant differences of lymphoid depletion in herbal groups and antibiotic group suggest that the cell improvement might be from 1,8-cineol and curcumin effects. The substance proactively inhibits the bacterial virulence, at the same time modulating immune cells to be more resistant against injury. Each mechanism is widely known yet the contribution on immune organs is still questionable.

4.3. JCEO and DT Roles and Mechanism in Protecting Spleen Cells

It is proved that the result of bioactive compounds in the JCEO extraction process is 1,8-cineol. Cineol has two mechanisms of antibacterial activity. The first mechanism is by disrupting and altering the structure of

E. coli biofilm formation, which consists of an extracellular polymer matrix [

30]. The initial mechanism by binding to porin (a transmembrane protein) on the outer membrane of the bacterial cell wall. This bond results in damage to the porin, which reduces the permeability of the bacterial cell wall, ultimately leading to bacterial death due to changes in the hydrophobicity of the

E. coli membrane. This is what makes lipopolysaccharides in

E. coli more susceptible to cineole [

5].

The second mechanism involves disrupting a quorum-sensing system in

E. coli, specifically the

LuxS protein from the

autoinducer-2 (AI-2) system [

30]. This process results in bacteria that cannot express the

LuxS protein; therefore, they lack adhesion genes, which are considered virulence factors as we discussed before. In addition to its antibacterial activity, some studies have explored the anti-inflammatory properties of cineol. It stated that cineole can reduce inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen radicals (ROS) by inhibiting cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) production (refers to

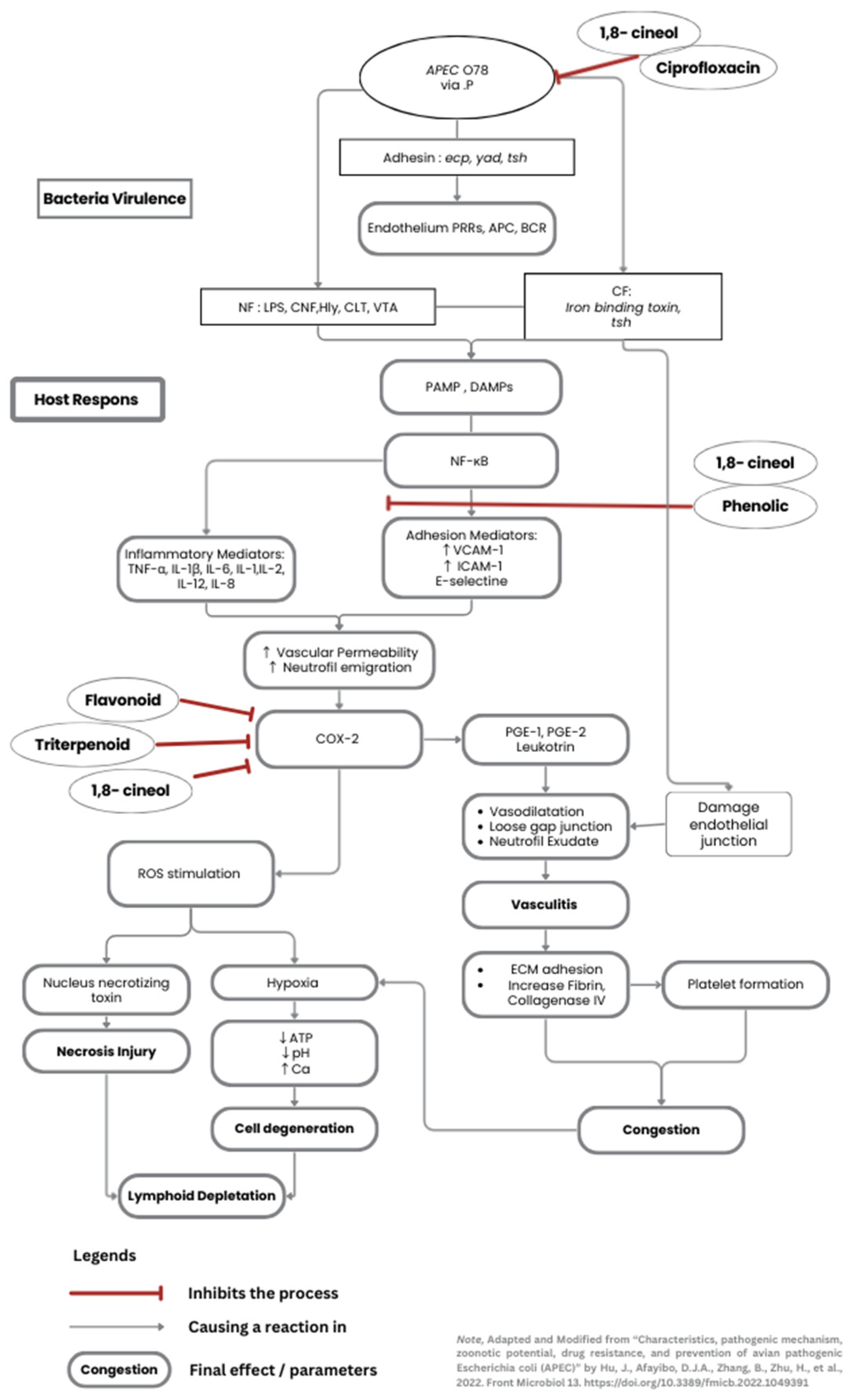

Supplementary Figure S3 A) [

30,

31].

Curcumin has been investigated for its potential to genetically enhance growth in broiler chickens, reduce oxidative stress, and stimulate the formation of immune cells (

Figure S3 B). Studies on high-stock-density chickens have shown that curcumin can significantly increase the synthesis of humoral immune, by escalating the proliferation of B and T lymphocytes produced in lymphoid follicles. Therefore, the spleen can efficiently produce plasma cells, which then secrete antibodies [

32,

33].

Overall, these combination properties work well together. Primarily, JCEO has a potent antibacterial effect, and DT promotes immunomodulation. The 1,8-cineol antibacterial activity is conducted as bacteria lose their integrity, thereby preventing them from penetrating deeper into the splenic structure. Even though some necrotic cells were visible around the blood vessels due to the APEC endotoxin effects, the cineol also had an anti-inflammatory effect to minimises additional cell injuries. Simultaneously, DT enhanced differentiation of lymphocytes and reduce inflammatory cytokines. When it given as a routine supplement, the immune organ has already developed an adequate and mature environment for immune cells to reduce injuries at the moment chicken infected. The author created a diagram flow about pathogenicity of APEC, as well as the mechanisms of cineol and curcumin roles towards spleen cells in

Figure 4.

4.4. The Effect on Other Organs

Two similar studies conducted the same experiment with different organ analyses. The herbal and antibiotic effects were observed in the broiler hearts and lungs challenged with the same APEC suspension [

34,

35]. Vasculitis, thrombus, and granulation tissue were the highlighted pathological findings in the heart. Severity scores in the lungs appear insignificant, but typical pathological lesions were found in all groups (pneumocyte inflammation and abnormality of the parabronchi structure). Overall, the lesions are similar between organs. The damage to the vascular wall and infiltration of granulocytes within the cells indicate the effects of adhesion and endotoxin from APEC.

An interesting discovery regarding dosages was made, specifically the combination of 0.06 ml/kg BW JCEO dose with the 400 mg/kg feed of curcumin showed better improvement in the lungs. In contrast to the heart and spleen, a higher dose of JCEO was more effective in protecting cells. The study states that higher doses of cineol may cause side effects on the digestive tract, resulting in a high feed consumption rate due to intestinal damage [

34].There is insufficient evidence to support this argument, as it does not demonstrate how 0.1 ml/kg BW JCEO resulted in a better outcome in well-vascularized organs.

Both studies reported that antibiotics resulted in a moderate severity score. At this point, the scenario also happened in the spleen, even though the experiment already followed manufacturer standardised antibiotic dosage. Antibiotic efficacy degradation is likely to occur when antibiotics are administered through drinking water. The powdered dosage formulation exhibits slower pharmacodynamic activity than the injectable dosage form, whereas the APEC was administered peritoneally. Furthermore, the chickens received no additional supplements or special care during the rearing period. The chickens' immune systems may have been weakened compared to those in other groups treated with herbal treatments that have immunomodulatory effects. The antibiotic group did not exhibit the additional anti-inflammatory properties. As consequences, the depletion of follicles is irreversible.

5. Conclusions

The discussion concluded based on the histopathological assessment of the spleen organ, despite some limitations of the study. The lowest lesion spleen histopathology scores were observed in the combination group, which consisted of JCEO 0.1 mg/kg BW and DT 400mg/kg feed. The theory of 1,8-cineol antibacterial activity and curcumin anti-inflammatory mechanism can be observed through the spleen's inner structure. Histopathological features reveal a compact density of lymphoid follicles, a slight condition of vasculitis, and a distinguish structure of WP and RP.

Changing the H&E staining into more precise stains, such as immunochemistry, may improve the differentiate on specific lymphocyte cells. Masson Trichrome and silver staining can also be used to easily analyse the fibrin matrix structure for vascular damage. If the bacterial debris could be seen within the cells, the evidence would be more convincing. Other vital organs, especially the intestine and bursa fabricii, need to be assessed immediately to make comprehensive evidence.

The broiler spleen scoring system is still lacking standardisation due to a modicum of research in this specific field. This study modified the pathology assessment based on a practical case of spleen injuries caused by the Escherichia coli pathogenic strain [41]. Other exposures to injuries, besides bacteria, may result in different lesions to be assessed.

Therefore, for the fundamental analysis of spleen histopathology, this study recommends using enhanced histopathology of the spleen and the practice guideline for pathology evaluation of the immune system [

36,

37]. By knowing the basic compartment and histology structure of the spleen, any characteristic of a different agent can be observed thoroughly.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: ANOVA Multiple comparisons statistical data on each parameter; Figure S1: An overview of histopathological assessment in the broiler spleen experiment group in low magnification (20×, H&E Stain); Figure S2: Spleen WP and RP architecture damage across the groups in high magnification (400×, H&E Stain); Figure S3: The mechanism of cineol against bacteria (A) and curcumin’s properties (B) towards immune response. Figure S4: Physical properties and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry result of Javanese cardamom essential oil (JCEO); Figure S5: Physical properties, phytochemical test, and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry result of dried turmeric ethanol extract (DT).

Author Contributions

T.H; Conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration. methodology, supervision, resources. M.R.A.A.S; methodology, formal analysis, validation, visualization

A.M.R., and S.K.; Data curation, validation, writing—review and editing. B.B; formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was fully funded through the Directorate of Research and Community Service under the grant number 1491/UN6.3.1/PT.00/2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Padjadjaran (protocol code 871/UN6.KEP/EC/2020)

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Other datasets, such as those for statistical analysis and other histopathological fields, can be requested from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author team extends its gratitude to Meita Kartika, from Laboratorium Sentral Universitas Padjadjaran, Subang Veterinary Centres, and Center of Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratoriesor Balai Besar Veteriner, Bogor (BBVET), for ensuring the experiment ran smoothly. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used Zeiss Zen Lite Application with Zeiss Microscope Apotome 2 for curating and capturing the histopathological slide views. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| A |

artery or splenic artery |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

| APEC |

Avian Pathogenic Escherichia Coli |

| BW |

body weight |

| °C |

Celsius |

| CA |

central arteriole |

| COX-2 |

cyclooxygenase 2 |

| CNF |

cytotoxic necrotising factors |

| CFU |

colony-forming unit |

| DAMPs |

Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns |

| DT |

dried turmeric ethanol extract |

| ecp |

Escherichia common pilli |

| ECM |

extracellular matrix |

| F |

follicle or splenic follicle |

| g |

gram |

| Irb-toxin |

iron-binding toxin |

| IP |

intraperitoneal |

| JCEO |

Javanese cardamom essential oil |

| mL/kg |

mililiter per kilogram |

| mg/kg |

miligram per kilogram |

| NaCl |

natrium chloride |

| PALS |

periarterial lymphoid sheath |

| RBC |

red blood cells |

| ROS |

reactive oxygen species radicals |

| RP |

red pulp |

| tsh |

temperature-sensitive haemagglutinin |

| yad |

Yad fimbriae |

| V |

vasculitis |

| VAT |

vacuolating autotransporter toxin |

| WP |

white pulp |

References

- Lutful Kabir, S.M. Avian colibacillosis and salmonellosis: a closer look at epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, control and public health concerns. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2010, 7, 89–114. [CrossRef]

- Panth, Y. Colibacillosis in poultry: A review. Journal of Agriculture and Natural Resources 2019, 2, 301–311. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.N.; Sharma, N. Avian Pathology: A Colour Handbook; New India Publishing Agency: 2018.

- Brugère-Picoux, J.; Vaillancourt, J.P.; Bouzouaia, M. Manual of Poultry Diseases. AFAS: 2015; pp. 301–316.

- Shah, S.A.; Mir, M.S.; Wani, B.M.; Kamil, S.A.; Goswami, P.; Amin, U.; Shafi, M.; Rather, M.A.; Beigh, A.B. Pathological studies on avian pathogenic Escherichia coli infection in broilers. Pharma Innovation 2019, 8, 68–73.

- Taunde, P.A.; Bianchi, M.V.; Mathai, V.M.; Lorenzo, C.D.; Gaspar, B.D.C.B.; Correia, I.M.S.M.; Laisse, C.J.M.; Driemeier, D. Pathological, microbiological and immunohistochemical characterization of avian colibacillosis in broiler chickens of Mozambique. Pesquisa Veterinária Brasileira 2021, 41. [CrossRef]

- Abalaka, S.; Sani, N.; Idoko, I.; Tenuche, O.; Oyelowo, F.; Ejeh, S.; Enem, S. Pathological changes associated with an outbreak of colibacillosis in a commercial broiler flock. Sokoto Journal of Veterinary Sciences 2017, 15, 95. [CrossRef]

- Wibisono, F.J.; Sumiarto, B.; Kusumastuti, T.A. Economic Losses Estimation of Pathogenic Escherichia coli Infection in Indonesian Poultry Farming. Buletin Peternakan 2018, 42. [CrossRef]

- Kurnia, R.S.; Indrawati, A.; Mayasari, N.; Priadi, A. Molecular detection of genes encoding resistance to tetracycline and determination of plasmid-mediated resistance to quinolones in avian pathogenic Escherichia coli in Sukabumi, Indonesia. Vet World 2018, 11, 1581–1586. [CrossRef]

- Hartady, T.; Balia, R.L.; Syamsunarno, M.R.A.A.; Jasni, S.; Priosoeryanto, B.P. Bioactivity of Amomum Compactum Soland Ex Maton (Java Cardamom) as a Natural Antibacterial. Sys Rev Pharm 2020, 11, 384–387. [CrossRef]

- Galli, G.M.; Griss, L.G.; Boiago, M.M.; Petrolli, T.G.; Glombowsky, P.; Bissacotti, B.F.; Copetti, P.M.; Silva, A.D.d.; Schetinger, M.R.; Sareta, L.; et al. Effects of curcumin and yucca extract addition in feed of broilers on microorganism control (anticoccidial and antibacterial), health, performance and meat quality. Research in Veterinary Science 2020, 132, 156–166. [CrossRef]

- Mutmainah; Susilowati, R.; Rahmawati, N.; Nugroho, A.E. Gastroprotective effects of combination of hot water extracts of turmeric (Curcuma domestica L.), cardamom pods (Ammomum compactum S.) and sembung leaf (Blumea balsamifera DC.) against aspirin–induced gastric ulcer model in rats. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine 2014, 4, S500–S504. [CrossRef]

- Hull Vance, S.; Tucci, M.; Benghuzzi, H. Evaluation of the antimicrobial efficacy of green tea extract (egcg) against streptococcus pyogenes in vitro - biomed 2011. Biomed Sci Instrum 2011, 47, 177–182.

- Nikaido, H. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2003, 67, 593–656. [CrossRef]

- Raissa, R.; Amalia, W.C.; Ayurini, M.; Khumaini, K.; Ratri, P.J. The Optimization of Essential Oil Extraction from Java Cardamom. Journal of Tropical Pharmacy and Chemistry 2020, 5. [CrossRef]

- Malahayati, N.; Widowati, T.W.; Febrianti, A. Karakterisasi Ekstrak Kurkumin dari Kunyit Putih (Kaemferia rotunda L.) dan Kunyit Kuning (Curcuma domestica Val.). agriTECH 2021, 41, 134. [CrossRef]

- Younis, G.; Awad, A.; Mohamed, N. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of antimicrobial susceptibility of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from broiler chickens. Veterinary World 2017, 10, 1167–1172. [CrossRef]

- Barry, A.L. Methods for determining bactericidal activity of antimicrobial agents : approved guideline; National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards: United States, 1999; Volume 19, p. 32.

- Slaoui, M.; Bauchet, A.-L.; Fiette, L. Tissue Sampling and Processing for Histopathology Evaluation. In Drug Safety Evaluation: Methods and Protocols, Gautier, J.-C., Ed.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2017; pp. 101–114.

- Schafer, K.A.; Eighmy, J.; Fikes, J.D.; Halpern, W.G.; Hukkanen, R.R.; Long, G.G.; Meseck, E.K.; Patrick, D.J.; Thibodeau, M.S.; Wood, C.E.; et al. Use of Severity Grades to Characterize Histopathologic Changes. Toxicologic Pathology 2018, 46, 256–265. [CrossRef]

- Gibson-Corley, K.N.; Olivier, A.K.; Meyerholz, D.K. Principles for Valid Histopathologic Scoring in Research. Veterinary Pathology 2013, 50, 1007–1015. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Afayibo, D.J.A.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, H.; Yao, L.; Guo, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, D.; Peng, H.; et al. Characteristics, pathogenic mechanism, zoonotic potential, drug resistance, and prevention of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC). Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Jiang, S.; Wang, Q.; Dong, J.; Zhu, H.; Wang, P.; Meng, S.; Zhang, Z.; Chang, L.; Wang, G.; et al. Spleen-based proteogenomics reveals that <i>Escherichia coli</i> infection induces activation of phagosome maturation pathway in chicken. Virulence 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Khairani, S.; Fauziah, N.; Lina Wiraswati, H.; Panigoro, R.; Salleh, A.; Yuni Setyowati, E.; Berbudi, A. Piperine Enhances the Antimalarial Activity of Curcumin in Plasmodium berghei ANKA-Infected Mice: A Novel Approach for Malaria Prophylaxis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2022, 2022, 7897163. [CrossRef]

- Kostakioti, M.; Stathopoulos, C. Functional Analysis of the Tsh Autotransporter from an Avian Pathogenic <i>Escherichia coli</i> Strain. Infection and Immunity 2004, 72, 5548–5554. [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.A.; Zachary, J.F. Chapter 1 - Mechanisms and Morphology of Cellular Injury, Adaptation, and Death11For a glossary of abbreviations and terms used in this chapter see E-Glossary 1-1. In Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease (Sixth Edition), Zachary, J.F., Ed.; Mosby: 2017; pp. 2–43.e19.

- Kharat, M.; Du, Z.; Zhang, G.; McClements, D.J. Physical and Chemical Stability of Curcumin in Aqueous Solutions and Emulsions: Impact of pH, Temperature, and Molecular Environment. J Agric Food Chem 2017, 65, 1525–1532. [CrossRef]

- Shubin, A.V.; Demidyuk, I.V.; Komissarov, A.A.; Rafieva, L.M.; Kostrov, S.V. Cytoplasmic vacuolization in cell death and survival. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 55863–55889. [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.W.; Engle, E.L.; Shirk, E.N.; Queen, S.E.; Gama, L.; Mankowski, J.L.; Zink, M.C.; Clements, J.E. Splenic Damage during SIV Infection. The American Journal of Pathology 2016, 186, 2068–2087. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, X.; Fang, C.; Xing, R.; Liu, L.; Zhao, X.; Zou, Y.; Li, L.; Jia, R.; et al. 1,8-Cineole inhibits biofilm formation and bacterial pathogenicity by suppressing luxS gene expression in Escherichia coli. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.A.; Lee, M.Y.; Shin, I.S.; Seo, C.S.; Ha, H.; Shin, H.K. Anti-inflammatory effects of Amomum compactum on RAW 264.7 cells via induction of heme oxygenase-1. Arch Pharm Res 2012, 35, 739–746. [CrossRef]

- Hafez, M.H.; El-Kazaz, S.E.; Alharthi, B.; Ghamry, H.I.; Alshehri, M.A.; Sayed, S.; Shukry, M.; El-Sayed, Y.S. The Impact of Curcumin on Growth Performance, Growth-Related Gene Expression, Oxidative Stress, and Immunological Biomarkers in Broiler Chickens at Different Stocking Densities. Animals 2022, 12, 958. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Han, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ishfaq, M.; Liu, R.; Wei, G.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X. Effect of Curcumin as Feed Supplement on Immune Response and Pathological Changes of Broilers Exposed to Aflatoxin B1. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1188. [CrossRef]

- Hartady, T.; Ghozali, M.; Parsonodihardjo, C. Histopathological Picture of Lung Organs Towards Combination of Java Cardamom Seed Extract and Turmeric Rhizome as Anti-Colibacillosis in Broiler Chickens. Veterinary Sciences 2025, 12, 726. [CrossRef]

- Hartady, T.; Sugandi, S.D.; Septiyani; Hiroyuki, A.; Goenawan, H. Effects of Javanese Cardamom and Turmeric on the Prevention of Colibacillosis and Its Impact on Broiler Chickens' Hearts. World's Veterinary Journal 2025, 15, 421–433. [CrossRef]

- Elmore, S.A. Enhanced Histopathology of the Spleen. Toxicologic Pathology 2006, 34, 648–655. [CrossRef]

- Haley, P.; Perry, R.; Ennulat, D.; Frame, S.; Johnson, C.; Lapointe, J.M.; Nyska, A.; Snyder, P.; Walker, D.; Walter, G. STP position paper: best practice guideline for the routine pathology evaluation of the immune system. Toxicol Pathol 2005, 33, 404–407; discussion 408. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).