Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

02 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- (i)

- refine, optimise, and introduce novel versions of state-of-the-art algorithms for GSD, IC detection, and SL estimation using wrist-worn IMUs

- (i)

- technically validate and rank these algorithms in real-world settings.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Population

Experimental Protocol

IMU Data

Reference Data

Algorithms Selection and Optimisation

Performance Metrics

GSD

IC

SL

3. Results

3.1. Performance Metrics of Algorithms

3.1.1. GSD

3.1.2. ICD

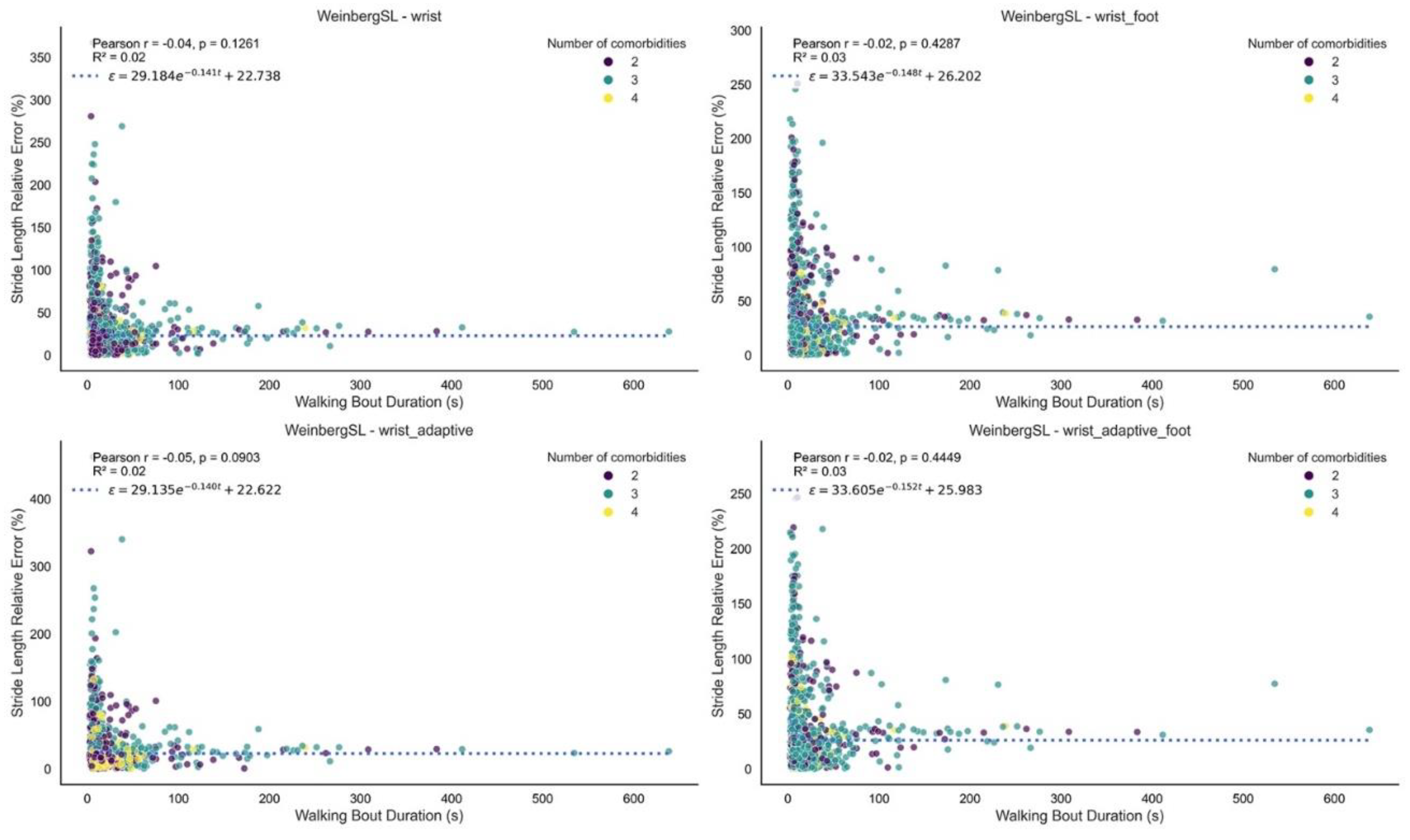

3.1.3. Stride Length

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. GSD

4.3. ICD

4.4. SL estimation

4.5. Algorithm Performance and Gait Pattern Diversity

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DMO | Digital Mobility Outcome |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| TVS | Technical Validation Study |

| MLTC | Multiple Long-Term Conditions |

| GSD | Gait Sequence Detection |

| IC / ICD | Initial Contact / Initial Contact Detection |

| SL | Stride Length Estimation |

| PFF | Proximal Femur Fracture |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| PD | Parkinson’s Disease |

| MS | Multiple Sclerosis |

| CHF | Chronic Heart Failure |

| RMS | Root Mean Square |

| μ | Mean of the acceleration signal between two consecutive ICs |

| Δt | Time difference between two consecutive ICs |

| TP | True Positive |

| FP | False Positive |

| TN | True Negative |

| FN | False Negative |

| R/L | Right/Left (foot) |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| CWT | Continuous Wavelet Transform |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| AI/ML | Artificial Intelligence / Machine Learning |

References

- Micó-Amigo, M.E., et al., Assessing real-world gait with digital technology? Validation, insights and recommendations from the Mobilise-D consortium. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, 2023. 20(1): p. 78. [CrossRef]

- Megaritis, D., et al., Effects of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions on physical activity outcomes in COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. ERJ Open Research, 2023. 9(5): p. 00409-2023. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ortiz, L., et al., How do people with COPD walk? A European study on digitally measured real-world gait. European Respiratory Journal, 2025: p. 2402303. [CrossRef]

- Mobilise-D. Connecting digital mobility assessment to clinical outcomes for regulatory and clinical endorsement [Accessed 1 Jul 2025].

- Kirk, C., et al., Mobilise-D insights to estimate real-world walking speed in multiple conditions with a wearable device. Scientific Reports, 2024. 14(1): p. 1754. [CrossRef]

- Kingston, A., et al., Projections of multi-morbidity in the older population in England to 2035: estimates from the Population Ageing and Care Simulation (PACSim) model. Age and Ageing, 2018. 47(3): p. 374-380. [CrossRef]

- Kobsar, D., et al., Validity and reliability of wearable inertial sensors in healthy adult walking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, 2020. 17(1): p. 62. [CrossRef]

- Germini, F., et al., Accuracy and Acceptability of Wrist-Wearable Activity-Tracking Devices: Systematic Review of the Literature. J Med Internet Res, 2022. 24(1): p. e30791. [CrossRef]

- Truslow, J., et al., Understanding activity and physiology at scale: The Apple Heart & Movement Study. npj Digital Medicine, 2024. 7(1): p. 242. [CrossRef]

- Brand, Y.E., et al., Gait Detection from a Wrist-Worn Sensor Using Machine Learning Methods: A Daily Living Study in Older Adults and People with Parkinson’s Disease. Sensors (Basel), 2022. 22(18). [CrossRef]

- Kluge, F., et al., Real-World Gait Detection Using a Wrist-Worn Inertial Sensor: Validation Study. JMIR Form Res, 2024. 8: p. e50035.

- Silvia, D.D., Mobilise-D Technical Validation Study (TVS) dataset (V1.0.2) Zenodo, Editor. 2025.

- Mazzà, C., et al., Technical validation of real-world monitoring of gait: a multicentric observational study. BMJ Open, 2021. 11(12): p. e050785. [CrossRef]

- Sinnige, J., et al., The Prevalence of Disease Clusters in Older Adults with Multiple Chronic Diseases – A Systematic Literature Review. PLOS ONE, 2013. 8(11): p. e79641. [CrossRef]

- Salis, F., et al., A multi-sensor wearable system for the assessment of diseased gait in real-world conditions. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 2023. 11. [CrossRef]

- Dimitrios, M., Multimobility_Wrist: Algorithms for Digital Mobility Assessment from Wrist-Worn Sensors. 2025, Zenodo.

- Küderle, A., Tasca, P., Bicer, M., Kirk, C., Megaritis, D., Hinchliffe, C., Stihi, A., Muecke, A., Babar, Z., Kluge, F., Mueller, and M. A., C., Del Din, S., Cereatti, A., Rochester, L., Rooks, D., & Caulfield, B. , MobGap - The Mobilise-D algorithm toolbox.

- Hickey, A., et al., Detecting free-living steps and walking bouts: validating an algorithm for macro gait analysis. Physiol Meas, 2017. 38(1): p. N1-n15.

- Kheirkhahan, M., et al. Adaptive walk detection algorithm using activity counts. in 2017 IEEE EMBS International Conference on Biomedical & Health Informatics (BHI). 2017.

- MacLean, M.K., et al. Walking Bout Detection for People Living in Long Residential Care: A Computationally Efficient Algorithm for a 3-Axis Accelerometer on the Lower Back. Sensors, 2023. 23. [CrossRef]

- Keren, K., et al., Quantification of Daily-Living Gait Quantity and Quality Using a Wrist-Worn Accelerometer in Huntington’s Disease. Front Neurol, 2021. 12: p. 719442. [CrossRef]

- Paraschiv-Ionescu, A., et al., Locomotion and cadence detection using a single trunk-fixed accelerometer: validity for children with cerebral palsy in daily life-like conditions. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, 2019. 16(1): p. 24. [CrossRef]

- Iluz, T., et al., Automated detection of missteps during community ambulation in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a new approach for quantifying fall risk in the community setting. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, 2014. 11(1): p. 48. [CrossRef]

- Ducharme, S.W., et al., A Transparent Method for Step Detection using an Acceleration Threshold. J Meas Phys Behav, 2021. 4(4): p. 311-320. [CrossRef]

- Gu, F., et al., Robust and Accurate Smartphone-Based Step Counting for Indoor Localization. IEEE Sensors Journal, 2017. 17(11): p. 3453-3460.

- Shin, S.H. and C.G. Park, Adaptive step length estimation algorithm using optimal parameters and movement status awareness. Med Eng Phys, 2011. 33(9): p. 1064-71. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H., et al., Computational methods to detect step events for normal and pathological gait evaluation using accelerometer. Electronics Letters, 2010. 46: p. 1185-1187. [CrossRef]

- Zijlstra, W. and A.L. Hof, Assessment of spatio-temporal gait parameters from trunk accelerations during human walking. Gait Posture, 2003. 18(2): p. 1-10.

- Micó-Amigo, M.E., et al., A novel accelerometry-based algorithm for the detection of step durations over short episodes of gait in healthy elderly. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, 2016. 13(1): p. 38.

- McCamley, J., et al., An enhanced estimate of initial contact and final contact instants of time using lower trunk inertial sensor data. Gait Posture, 2012. 36(2): p. 316-8.

- Pham, M.H., et al., Validation of a Step Detection Algorithm during Straight Walking and Turning in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease and Older Adults Using an Inertial Measurement Unit at the Lower Back. Front Neurol, 2017. 8: p. 457.

- Weinberg, H., Using the ADXL202 in Pedometer and Personal Navigation Applications. Analog Devices AN-602 Application Note, 2002. 2: p. 1-6.

- Kim, J., et al., A Step, Stride and Heading Determination for the Pedestrian Navigation System. Journal of Global Positioning Systems, 2004. 3: p. 273-279.

- Bylemans, I., M. Weyn, and M. Klepal. Mobile Phone-Based Displacement Estimation for Opportunistic Localisation Systems. in 2009 Third International Conference on Mobile Ubiquitous Computing, Systems, Services and Technologies. 2009.

- Bonci, T., et al. An Objective Methodology for the Selection of a Device for Continuous Mobility Assessment. Sensors, 2020. 20, DOI: 10.3390/s20226509. [CrossRef]

- Zadka, A., et al., A wearable sensor and machine learning estimate step length in older adults and patients with neurological disorders. NPJ Digit Med, 2024. 7(1): p. 142. [CrossRef]

- Brand, Y.E., et al., Continuous Assessment of Daily-Living Gait Using Self-Supervised Learning of Wrist-Worn Accelerometer Data. medRxiv, 2025.

| Algorithm | Description | Adaptations for Wrist-Worn Sensor and Improved/Novel versions | Thresholds per version (in g-unit for simplicity): |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSD | |||

| Hickey [18] | Identifies bouts of walking using window-based calculations of the acceleration signal variability and orientation thresholds. Includes resampling, gravity removal, axis correction, and Butterworth filtering. | Gravity is removed from all axes before computing the acceleration norm. The “thresholdstill” is fine-tuned for the wrist-worn position. The original upright-position threshold, based on vertical acceleration from a lower-back sensor, is replaced by a maximum activity threshold applied to the norm. This threshold corresponds to the 100th percentile of wrist acceleration during walking bouts in the TVS dataset (n=108), excluding high-intensity activities that may meet other walking variability criteria. |

wrist* -thresholdstill = 0.1 -thresholdupright = 9.5 |

| Kheirkhahan [19] | Identifies walking bouts using activity counts from triaxial acceleration. Data are preprocessed, segmented into overlapping windows, and windows meeting criteria are marked as walking. | The optimised wrist version uses the acceleration norm and improved threshold, and window size fine-tuned for the wrist worn position. |

wrist* -threshold = 0.58 -win_size = 9 |

| MacLean [20] | Identifies walking bouts using a threshold-based algorithm. The signal is filtered, centred, and the norm is used. A binary activity signal is generated and smoothed to identify continuous active periods. Short inactive gaps between active segments are merged, and candidate bouts are evaluated against signal intensity and duration criteria. | Since the acceleration norm is used already, the thresholds have been fine-tuned for the wrist-worn position. |

wrist* threshold_binary = 0.11 gap_threshold = 0.4 gap_index = 0.1 walk_threshold = 0.5 walk_index = 0.05 |

| Keren [21] | Identifies walking bouts using a multi-step algorithm applied. The norm of the signal is filtered and detrended. Gait-like windows are detected based on peak presence, signal variability, dominant frequency, and autocorrelation regularity. Conditions are evaluated in overlapping windows, and consecutive valid segments are merged into walking bouts. | The improved version includes fine-tuned thresholds. An adaptive version has been introduced using a dynamic threshold based on a percentile of the acceleration signal, rather than a fixed value. |

improved* threshold = 0.08 threshold_sd = 0.07 adaptive* threshold_percentile = 84 threshold_sd = 0.07 |

| Ionescu [22] | Identifies walking bouts by detecting steps from the low-pass filtered acceleration norm. Peaks above a threshold indicate steps, which are grouped into gait sequences using an adaptive step duration threshold. In addition, an adaptive version sets the step threshold based on a percentile of peak amplitudes in detected active periods. | Since the acceleration norm is used already, the thresholds of both the fixed and adaptive versions have been fine-tuned for the wrist-worn position. |

wrist* active_signal_threshold = 0.31 wrist_adaptive* active_signal_fallback_threshold = 0.4 percentile = 31 |

| Iluz [23] | Identifies walking bouts using a frequency-based approach applied to vertical and anterior–posterior acceleration signals. First, these signals are band-pass filtered. Then, a convolution with a sine wave is performed, and local maxima from this convolution are detected to define gait regions. | To adapt the algorithm for wrist-worn data, gravity removal is applied per axis at the start, activity is detected using the acceleration norm, standing and orientation change checks are removed, and peak detection is performed only once. The |

wrist* std_threshold = 0.06 step_threshold = 0.84 |

| IC | |||

| Ducharme [24] | Detects initial contact events using the tri-axial accelerometer norm. The signal is first detrended by mean subtraction, then resampled to 80 Hz to apply a fourth-order Butterworth bandpass filter (0.25–2.5 Hz). Peaks above a specified threshold are identified as initial contacts using a standard peak detection function. The detected peak indices are then rescaled to the original sampling frequency. | The algorithm was designed for a lower-back sensor but already operates on the norm of tri-axial acceleration. To adapt it for wrist-worn sensor, the detection threshold has been fine-tuned. |

wrist* threshold = 0.01 |

| Gu [25] | Detects initial contacts using peak detection and multi-stage filtering. It segments the signal, identifies local maxima, and applies thresholds on peak magnitude, periodicity, similarity, and continuity to improve robustness. | The algorithm was designed for use with a wrist-worn sensor. The thresholds have been fine-tuned. In addition, a novel adaptive version has been introduced based on percentiles of the acceleration signal for the magnitude threshold. |

improved* k = 2 period_min = 25 period_max = 120 sim_thres = -0.7 var_thres = 0.0005 mag_thres = 1.1 adaptive* k = 2 period_min = 25 period_max = 110 sim_thres = -0.7 var_thres = 0.005 * (9.81**2) mag_thres = 70 |

| Shin [26] | Detects initial contacts on the norm of the acceleration signals. A sliding window sum reduces noise in the acceleration norm. A differencing step acts as a high-pass filter to remove gravity. Initial contacts are then identified as zero-crossings on the positive slope. | The algorithm was designed for a lower-back sensor but already operates on the norm of tri-axial acceleration, hence, it is used as is. | original* |

| Lee [27] | Detects initial contacts by preprocessing the acceleration norm using low-pass filtering, detrending, Savitzky–Golay smoothing, and Gaussian smoothing, followed by a continuous wavelet transform to enhance step features. Morphological filters are then applied, and initial contact events are detected as maxima between zero-crossings. | The algorithm was designed for a lower-back sensor but already operates on the norm of tri-axial acceleration, hence, it is used as is. | original* |

| Zijlstra [28] | Detects initial contacts by preprocessing the acceleration signal with detrending and low-pass filtering to isolate gait-related components. Initial contacts are then identified either by detecting positive-to-negative zero crossings or by locating peak maxima between zero crossings. | The algorithm was designed for a lower-back sensor and the anteroposterior axis was used, hence, in the wrist version the acceleration norm was used. The peak detection method as well as the cutoff for the Butterworth filter were fine tuned for use in wrist-worn IMUs. |

wrist* cutoff = 2.5 peak detection method=“peak” |

| Micó-Amigo [29] | Detects initial contacts by estimating step periodicity via autocovariance and spectral analysis to define a subject-specific template. A template-matching approach based on dynamic time warping (DTW) identifies high-similarity segments through normalised correlation and variance. Peaks in the resulting similarity signal are selected as initial contacts. | Adapted for wrist-worn sensor by removing the gravity component from the 3-axis acceleration signal using a Butterworth filter, followed by computing the signal norm replacing the original lower-back anteroposterior axis. Two new parameters, peakdistance and peakdistance_coef, have been introduced and fine-tuned for wrist-worn sensor. These control the minimum spacing between peaks in the acceleration and similarity signals, respectively, and were optimized to improve detection accuracy. |

wrist* peakdistance = 1.1 peakdistance_coef = 1.0 shiftfactor = 0.15 factorlimit = 2 event_offset = 5 |

| McCamley [30] | Detects initial contacts by downsampling (50 Hz) and preprocessing the acceleration signal with detrending and a low-pass Butterworth filter (20 Hz), followed by cumulative trapezoidal integration. The integrated signal is smoothed using a continuous wavelet transform (CWT) and upsampled back to the original sampling rate. Initial contacts are identified as local minima. Detected events are then filtered to remove those occurring less than 0.25 seconds apart or isolated beyond 2.25 seconds from neighbouring events. | The algorithm was designed for a lower-back sensor using the vertical (inferosuperior) acceleration axis. For the wrist version, the acceleration norm is used instead. In addition, the wavelet centre frequency is dynamically set using the signal’s dominant frequency to enchase sensitivity to individual gait patterns. |

wrist* cwt_method = “adaptive” |

| Pham [31] | Detects initial contacts by upsampling (128 Hz) and preprocessing the acceleration signal with detrending, low-pass Butterworth filtering (10 Hz), and cumulative trapezoidal integration. The smoothed signal is further processed using a continuous wavelet transform (CWT). The resulting signal is detrended again, and local minima are detected. Peaks are retained only if their magnitude exceeds a specified percentage of the average peak amplitude. | The algorithm was originally designed for a lower-back sensor using the anteroposterior axis. For the wrist version, the acceleration vector norm was used instead. The peak detection threshold percentage was fine-tuned to optimise performance for wrist data. In addition, the wavelet centre frequency is dynamically set using the signal’s dominant frequency to enchase sensitivity to individual gait patterns. |

wrist* percentage_thresh = 0.02 cwt_method = “adaptive” |

| SL | |||

| Weinberg [32] | Step length is estimated using an intensity-based method. The acceleration signal is preprocessed by computing the Euclidean norm and applying a low-pass Butterworth filter (2 Hz). Step length is calculated between consecutive initial contacts using the formula:. Values are interpolated to per-second resolution; stride length is twice the step length. | Since the original algorithm was developed within the framework of inertial dead reckoning systems, finely tuned versions are provided in this paper. Additionally, adaptive versions are introduced, which utilise the root mean square (RMS) of acceleration between consecutive initial contacts multiplied by a finely tuned constant threshold (see Equation 1). Furthermore, foot length–augmented variants are introduced, where an additional term based on individual foot length (in cm) is incorporated into the model to personalise stride length estimation. |

wrist* A = 0.62 B = 0 wrist_footlength* A = 0.21 B = foot length (cm) wrist_adaptive* A = 0.60 B = 0 wrist_adaptive_footlength* A = 0.20 B = foot length (cm) |

| Kim [33] | Step length is estimated using an intensity-based method. Step length is calculated between consecutive initial contacts using the Euclidean norm and the formula . Values are interpolated to per-second resolution; stride length is twice the step length. |

Since the original algorithm was developed within the framework of inertial dead reckoning systems, finely tuned versions are provided in this paper. Additionally, adaptive versions are introduced, which utilise the RMS of acceleration between consecutive initial contacts multiplied by a finely tuned constant threshold (see Equation 2). Furthermore, foot length–augmented variants are introduced, where an additional term based on individual foot length (in cm) is incorporated into the model to personalise stride length estimation. |

wrist* A = 0.35 B = 0 wrist_footlength* A = 0.10 B = foot length (cm) wrist_adaptive* A = 0.35 B = 0 wrist_adaptive_footlength* A = 0.10 B = foot length (cm) |

| Bylemans [34] | Step length is estimated using an intensity-based method with signal preprocessing. Acceleration data are high-pass filtered and smoothed using a moving average. Step length is calculated between consecutive initial contacts using the formula: ; stride length is twice the step length. |

Since the original algorithm was developed within the framework of inertial dead reckoning systems, finely tuned versions are provided in this paper. The preprocessing of the signal has been improved in the current implementation by replacing the original custom IIR high-pass filter with a 4 Hz 4th-order Butterworth filter for improved signal fidelity and reproducibility. Additionally, adaptive versions are introduced, which utilise the RMS of acceleration between consecutive initial contacts multiplied by a finely tuned constant threshold (see Equation 3). Furthermore, foot length–augmented variants are introduced, where an additional term based on individual foot length (in cm) is incorporated into the model to personalise stride length estimation. |

wrist* A = 2.30 B = 0 wrist_footlength* A = 0.75 B = foot length (cm) wrist_adaptive* A = 9.15 B = 0 wrist_adaptive_footlength* A = 3.46 B = foot length (cm) |

| Variable | n = 28 |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 70.4 (10.7) |

| Sex, Female n (%) | 12 (43%) |

| Height (cm), mean (SD) | 168.9 (9.2) |

| Weight (Kg), mean (SD) | 77.8 (16.8) |

| BMI (Kg/m2), mean (SD) | 27.4 (6.3) |

| MoCa score, median (Q1-Q3) | 26 (21-28) |

| VAS score,_GeneralPain, median (Q1-Q3) | 6 (3-26) |

| VAS score,_Walking Pain, median (Q1-Q3) | 8 (2-38) |

| LLFDI score, median (Q1-Q3) | 58 (49-67) |

| Fall History, Yes n(%) | 11 (39%) |

| Walking aid use, n(%) | |

| One cane/crutch | 4 (14%) |

| Rollator | 3 (11%) |

| Walker | 1 (4%) |

| Other | 1 (4%) |

| Number of co-occurring long-term conditions, median (range) | 3 (2-4) |

| Cardiovascular Disease | 14 (50%) |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 8 (29%) |

| Lung Disease (other than COPD) | 4 (14%) |

| Hypertension | 20 (71%) |

| Arthritis | 3 (11%) |

| Gouty arthritis | 2 (7%) |

| Depression | 3 (11%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 5 (18%) |

| Multiple Sclerosis | 4 (14%) |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 3 (11%) |

| Parkinson’s Disease | 8 (29%) |

| Proximal Femur Fracture | 6 (21%) |

| Method | Version | Performance Index | Detected Walking Time (s) | Reference Walking Time (s) | Specificity | Accuracy | Recall | Precision | Absolute Relative Duration Error (%) | ICC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kheirkhahan | wrist_improved | 0.76 | 892.53 [681.32, 1103.74] | 1028.44 [809.28, 1247.60] | 0.96 [0.95, 0.98] | 0.92 [0.90, 0.94] | 0.55 [0.45, 0.64] | 0.63 [0.53, 0.73] | 35 [23, 47] | 0.64 [0.36, 0.81] |

| Ionescu | wrist | 0.75 | 925.50 [693.32, 1157.68] | 1028.54 [809.37, 1247.72] | 0.96 [0.95, 0.98] | 0.92 [0.90, 0.94] | 0.55 [0.46, 0.65] | 0.63 [0.52, 0.74] | 41 [27, 55] | 0.60 [0.31, 0.79] |

| wrist_adaptive | 0.73 | 1043.35 [904.00, 1182.69] | 1028.55 [809.37, 1247.74] | 0.95 [0.94, 0.96] | 0.91 [0.89, 0.93] | 0.64 [0.54, 0.73] | 0.59 [0.48, 0.69] | 53 [27, 79] | 0.47 [0.12, 0.71] | |

| Keren | improved | 0.69 | 579.21 [424.14, 734.29] | 1028.94 [809.69, 1248.20] | 0.98 [0.97, 0.98] | 0.91 [0.89, 0.93] | 0.36 [0.28, 0.45] | 0.62 [0.51, 0.73] | 44 [33, 54] | 0.41 [-0.05, 0.71] |

| adaptive | 0.69 | 603.82 [445.95, 761.69] | 1028.93 [809.68, 1248.19] | 0.98 [0.97, 0.98] | 0.91 [0.89, 0.93] | 0.37 [0.28, 0.46] | 0.60 [0.49, 0.70] | 43 [33, 53] | 0.43 [-0.03, 0.72] | |

| Hickey | wrist_improved | 0.65 | 1076.48 [817.62, 1335.34] | 1028.74 [809.54, 1247.95] | 0.92 [0.90, 0.95] | 0.87 [0.84, 0.90] | 0.43 [0.35, 0.50] | 0.44 [0.35, 0.54] | 65 [32, 99] | 0.46 [0.11, 0.71] |

| MacLean | wrist | 0.65 | 819.60 [631.30, 1007.90] | 1028.62 [809.43, 1247.80] | 0.94 [0.93, 0.96] | 0.88 [0.85, 0.90] | 0.31 [0.23, 0.39] | 0.38 [0.29, 0.46] | 31 [20, 42] | 0.43 [0.09, 0.68] |

| Iluz | wrist | 0.60 | 1208.85 [881.06, 1536.65] | 1028.54 [809.36, 1247.72] | 0.90 [0.87, 0.93] | 0.85 [0.82, 0.88] | 0.41 [0.32, 0.51] | 0.38 [0.30, 0.46] | 95 [49, 142] | 0.37 [0.01, 0.65] |

| Method | Version | Performance Index | Recall | Precision | Absolute Timing Error (s) | Relative Timing Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ShinIC | wrist | 0.85 | 0.77 [0.72, 0.82] | 0.82 [0.77, 0.87] | 0.09 [0.08, 0.09] | 12 [11, 13] |

| McCamleyIC | wrist | 0.84 | 0.82 [0.79, 0.86] | 0.77 [0.73, 0.80] | 0.12 [0.11, 0.13] | 16 [15, 18] |

| ZijlstraIC | wrist | 0.83 | 0.78 [0.74, 0.82] | 0.77 [0.73, 0.81] | 0.12 [0.11, 0.13] | 16 [15, 18] |

| DucharmeIC | wrist | 0.82 | 0.76 [0.69, 0.83] | 0.77 [0.74, 0.81] | 0.12 [0.11, 0.13] | 16 [15, 18] |

| GuIC | adaptive | 0.82 | 0.69 [0.61, 0.77] | 0.79 [0.76, 0.82] | 0.10 [0.09, 0.10] | 14 [13, 15] |

| HKLeeIC | wrist | 0.82 | 0.77 [0.73, 0.81] | 0.79 [0.76, 0.82] | 0.13 [0.13, 0.14] | 19 [17, 20] |

| GuIC | improved | 0.82 | 0.67 [0.59, 0.74] | 0.82 [0.78, 0.85] | 0.10 [0.10, 0.11] | 14 [13, 15] |

| PhamIC | wrist | 0.82 | 0.77 [0.72, 0.82] | 0.74 [0.70, 0.78] | 0.12 [0.11, 0.13] | 16 [15, 18] |

| Micó-Amigo | wrist | 0.78 | 0.69 [0.64, 0.74] | 0.65 [0.60, 0.70] | 0.11 [0.10, 0.11] | 15 [14, 16] |

| Method | Version | Performance Index | Detected Stride Length (m) | Reference Stride Length (m) | Absolute Error (m) | Relative Error (%) | ICC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WeinbergSL | wrist | 0.72 | 0.78 [0.73, 0.82] | 0.76 [0.69, 0.84] | 0.19 [0.16, 0.21] | 31 [25, 37] | 0.63 [0.34, 0.81] |

| wrist_adaptive | 0.71 | 0.77 [0.73, 0.82] | 0.76 [0.69, 0.84] | 0.19 [0.16, 0.22] | 31 [24, 38] | 0.62 [0.33, 0.81] | |

| BylemansSL | wrist_adaptive_foot | 0.67 | 0.77 [0.73, 0.82] | 0.76 [0.69, 0.84] | 0.20 [0.18, 0.22] | 32 [27, 38] | 0.54 [0.21, 0.76] |

| WeinbergSL | wrist_adaptive_foot | 0.66 | 0.79 [0.76, 0.82] | 0.76 [0.69, 0.84] | 0.20 [0.18, 0.22] | 35 [28, 42] | 0.53 [0.20, 0.75] |

| wrist_foot | 0.66 | 0.79 [0.76, 0.82] | 0.76 [0.69, 0.84] | 0.20 [0.18, 0.22] | 35 [28, 42] | 0.53 [0.20, 0.75] | |

| BylemansSL | wrist_foot | 0.62 | 0.78 [0.75, 0.81] | 0.76 [0.69, 0.84] | 0.20 [0.18, 0.22] | 35 [28, 42] | 0.44 [0.08, 0.70] |

| wrist | 0.61 | 0.76 [0.71, 0.80] | 0.76 [0.69, 0.84] | 0.22 [0.19, 0.24] | 34 [28, 40] | 0.41 [0.05, 0.68] | |

| KimSL | wrist_adaptive_foot | 0.56 | 0.74 [0.72, 0.76] | 0.76 [0.69, 0.84] | 0.22 [0.19, 0.24] | 35 [27, 44] | 0.31 [-0.06, 0.61] |

| wrist_foot | 0.55 | 0.73 [0.71, 0.75] | 0.76 [0.69, 0.84] | 0.22 [0.19, 0.24] | 35 [27, 43] | 0.39 [0.04, 0.65] | |

| BylemansSL | wrist_adaptive | 0.55 | 0.65 [0.56, 0.73] | 0.76 [0.69, 0.84] | 0.33 [0.29, 0.37] | 47 [40, 54] | 0.30 [-0.07, 0.60] |

| KimSL | wrist_adaptive | 0.44 | 0.73 [0.72, 0.74] | 0.76 [0.69, 0.84] | 0.23 [0.20, 0.26] | 37 [28, 46] | 0.06 [-0.32, 0.42] |

| wrist | 0.42 | 0.70 [0.70, 0.71] | 0.76 [0.69, 0.84] | 0.23 [0.20, 0.26] | 37 [28, 45] | 0.01 [-0.33, 0.36] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).