1. Introduction

The increasing adoption of digital healthcare solutions is reshaping modern medicine, particularly in precision medicine, which tailors treatment and disease management based on individual variability in genes, environment, and lifestyle. Advances in health data analytics, artificial intelligence (AI), and wearable health devices have driven this transformation, enabling real-time patient monitoring and early disease detection[

1]. Cloud-based solutions, combined with machine learning models, are further improving patient care by streamlining data interoperability and clinical workflows, ultimately enhancing accessibility and reducing healthcare costs [

2]. As the healthcare industry moves toward remote patient monitoring and AI-driven diagnostics, the demand for scalable, cost-effective, and accessible digital health tools continues to rise.

Digital gait analysis has emerged as a powerful tool in biomechanics, rehabilitation, and sports medicine, enabling more objective assessments beyond traditional observational methods. Wearable devices such as inertial measurement units (IMUs) and force-sensitive footwear have improved accessibility but still face barriers in terms of cost, data reliability, and usability in real-world settings [

3]. AI-enhanced gait analysis, such as machine-learning-based event detection, has demonstrated potential benefits, particularly in patients with neurological impairments such as Parkinson’s disease [

4]. Open-source libraries like Scikit Digital Health offer accessible tools for gait, activity, and sleep data [

5], though their implementation often requires technical expertise, which may limit widespread clinical adoption. Furthermore, existing IMU-based systems require proper sensor placement and calibration [

6], making them less feasible for unsupervised, large-scale use. Among commercial solutions smartphone IMU-based movement assessments have been introduced such as OneStep (Celloscope Inc New York) which offer highly portable, feasible, and easy-to-use methods based on valid, reliable, and sensitive spatiotemporal gait parameters [

7].

Vision-based solutions, such as monocular pose estimation, provide contextual data by mapping full-body movement using an avatar representation. However, these methods introduce their own set of challenges. Accurate pose estimation often requires a controlled environment with good lighting and minimal background clutter [

8]. Factors such as loose clothing, which obscures key anatomical landmarks, can also impact tracking accuracy [

9]. Additionally, vision-based systems require sufficient space to keep the subject’s full body within the camera’s field of view, limiting usability in confined settings [

8]. These constraints underscore the trade-offs between sensor-based and vision-based gait analysis technologies.

Traditional methods for measuring human gait patterns, such as optical motion capture (MoCap) systems, force plates, and pressure-sensitive walkways, remain the ‘gold standard’ for gait analysis due to their high precision. However, “the expensive equipment and technical expertise necessary to operate a gait laboratory are inaccessible to most clinicians” [

9]. As a result, clinical gait assessments often rely on observational methods.

This study aims to validate the MoveLab

® sensor-based Gait Spatiotemporal Parameter (STP) analysis capabilities against a ‘gold standard’ optical MoCap system (Qualisys AB, Sweden), building on prior validation for vision-based assessments [

10]. In addition to gait analysis, the study evaluates the accuracy and reliability of MoveLab

® Timed-Up-and-Go (TUG) and Thirty-Second-Sit-to-Stand (STS) assessments, which are widely recognised indicators of balance, functional mobility, and lower limb strength [

11,

12,

13]. The findings of this study will contribute to the ongoing development of scalable, clinically validated digital mobility assessment tools, with potential applications in clinical, laboratory, and remote healthcare environments.

2. Materials and Methods

Twenty-five healthy volunteers (Female n=14, Male n=11, Age = 31.8± 11.6 yrs) with no history of gait impairment participated in this validation study. Following ethical approval from the relevant Research Ethics Committee (REC), all participants were given an Information Sheet and gave their written Informed Consent on the day of data collection. Participants were recruited via word of mouth within Cardiff University, and from the general public. Participants were offered a £25 shopping voucher as compensation for their time. The study was performed in the Musculoskeletal Biomechanics Research Facility (MSKBRF), School of Engineering, Cardiff University with all data collected in the Clinical Laboratory.

The MSKBRF Motion Capture (MoCap) Laboratory equipment comprised twelve Oqus 700+ infrared camera and two Oqus 210c video cameras (Qualisys AB, Sweden) for 2D and 3D data capture, at 100Hz and 24Hz respectively. The cameras were synchronised, using the QTM trigger module via a transistor-transistor logic (TTL) pulse to start and stop recording, with an instrumented walkway comprising six staggered ground reaction force plates (Bertec Inc., Ohio, USA), capturing at 1000 Hz. A standard marker set was implemented and all resulting MoCap data was tracked (Qualisys Track Manager, QTM) and processed through an established, standard 3D Inverse Dynamic Model pipeline (Visual 3D, HAS Motion, Ontario, Canada).

Agile Kinetic developed a browser based React (

https://react.dev/) Data Collection Application (DCA) for the study, using the smartphone’s built-in inertial sensors to measure acceleration and orientation in three dimensions at a sampling rate of at least 50Hz. The application enforced a consistent data labelling convention, allowing activities to be paired with the data recorded by the MoCap system. As shown in

Figure 1 the raw sensor data from each experimental repetition was stored in the device memory and then uploaded to a secure Firebase database (

https://firebase.google.com). A separate Python (Python Software Foundation. Python Language Reference, version 3.10. Available at

https://www.python.org) processing pipeline, running on a laptop, was used to fetch and process the raw sensor data. This pipeline consisted of four stages: data fetch, pre-processing, processing (which was different for each of the three activity types), and post-processing. The processing pipeline produced a .csv file containing predictions for each activity, grouped by participant for subsequent comparison with the MoCap system outputs.

Each participant was assigned a unique identification number (UID). Participant confidentiality was ensured by using the UID instead of the participant’s name when tagging data in the DCA and QTM.

Participants were asked to wear shorts and a loose vest or t-shirt and to perform all activities barefoot as per the generally accepted protocol for clinical gait analysis data collection. Retro-reflective markers were placed on their lower bodies according to a CAST lower body marker set [

14] (

Figure 2), which is a standard marker set used in clinical gait analysis assessments.

Each participant was also asked to ‘wear’ an android smartphone (Samsung Galaxy A25) provided by Agile Kinetic in a pouch provided and secured around the waist (

Figure 3).

Participants were asked to perform three sets of activities commonly used in clinical physiotherapy and rehabilitation settings to emulate movements characteristic of daily life: a thirty second walk (for gait parameter analysis), a Thirty-Second STS, and a TUG [

11], shown in

Figure 4.

The two methods simultaneously captured each activity and produced values across multiple metrics categorised as either STP, activity repetition count (for STS) or time taken to perform the activity (TUG).

Prior to performing each activity, participants accessed the DCA on the smartphone via a standard web browser. After entering their details and selecting the activity they were about to perform, participants pressed a key to start recording before placing the smartphone into the pouch. At the end of each activity, the smartphone was retrieved from the pouch and a key pressed to stop recording.

For the first activity, participants were asked to walk along the instrumented walkway at their natural pace and then continue walking within the laboratory for thirty seconds, around a marked track. MoCap data was collected when the participant was walking across the instrumented walkway in the calibrated volume, while the MoveLab® processing pipeline required a minimum of 30 seconds of data to generate gait parameters. For every participant, at least six walking trials were obtained (average = 8.72) until there were six clean force plate hits for left and right legs, to ensure collection of valid kinetic data.

For the second activity, participants were asked to perform STS, timed for thirty seconds, starting in a seated position on a stool located on the force plates.

The third TUG activity, also starting from a seated position, involved standing up and walking forward for three metres and back to a seated position with five separate trials recorded. The clinical standard assessment methods for the STS and TUG activities involved manual counting of repetitions, and manual timing with a stopwatch, respectively.

The following STP were produced in Visual3D; Speed (m/s), Stride Length (m), Step Length (m), Step Time (s), Cycle Time (s), Stance Time (s), Swing Time (s), Double Support (s), Initial Double Support (s), Terminal Double Support (s), Cadence (100 steps/min). The STS repetition counts and TUG times were tabulated for the number of trials for each participant.

Recordings were excluded when either the MoCap system failed to capture the activity appropriately to allow processing, or the DCA failed to upload sensor data to Firebase. For the latter case, this was due to the application occasionally failing to establish a stable internet connection.

The MoveLab® DCA processing pipeline established for this study estimated Gait STPs per subject, post-processing them into an accessible form to conduct comparison against the MoCap system. The estimated metrics summarise the trials per subject through a weighted average of all trials resulting in final Gait STPs per subject. As part of the research and development process, nine different methods were adopted, labelled M1 to M9 in the results section, to estimate the gait STPs, STS and TUG. The difference between them lies in the pre-processing algorithms, involving the rotation of inertial data through different planes, using a ratio between height and leg length versus direct leg length measurement, along with different filtering and averaging techniques. Where methods involving the ratio between the height and leg length of the subjects were used, the outputs were considered in stages. Firstly, a blind comparison, estimated gait metrics using a ratio derived in preliminary experiments. Then the ratio was refined to reflect the entire population of the 25 participating subjects.

The MoCap STPs were formatted for statistical analysis using MATLAB (MATLAB 2023. Version R2023a. Natick, Massachusetts: The MathWorks Inc.), and to generate STP mean and standard deviation. To assess agreement between the methods, the normality of the results was tested prior to performing Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) tests (SPSS) with a p-value of 0.05. The interpretation of the results is based on Koo and Li [

15], with an ICC >0.9 considered excellent, 0.75–0.9 good, 0.5–0.75 moderate, and <0.5 poor. Bland-Altman plots were produced (Python Software Foundation. Python Language Reference, version 3.10. Available at

https://www.python.org) to assess agreement between the two approaches by plotting the differences between the outputs from the two methods against their average for each parameter. This allows visualisation of the spread of MoveLab

® data outputs for STP, TUG and STS compared to the clinical ‘gold standard’ for all participants.

It should be noted the data collection protocol for STS dictated that the participant returned to sitting and manually stopped recording on the DCA when the laboratory team advised them that the 30 seconds had ended. For some trials, there was a misalignment between the person timing 30 seconds and the participant stopping the count. Thus, when the timer used by the laboratory stopped in the middle of a repetition, the DCA continued to record the final repetition. This resulted in the STS estimator reporting an extra count for these trials. This was acknowledged as a constraint of the experimental protocol involving the interaction with the DCA.

3. Results

Twenty-five healthy volunteers were recruited for the study with the following characteristic mean ± standard deviation: age = 31.8 ± 11.6 yrs, height= 1.73 ± 0.10m, weight = 67.67 ± 12.70kg, left leg length= 0.90 ± 0.06m.

The ICC between the MoCap and the MoveLab

® STPs is presented in

Table 1.

Table 2 shows the mean differences between the MoveLab

® STP outputs when compared to the means of the MoCap outputs. For all methods (calculated using the range of algorithms tested in the MoveLab

® processing pipeline), the spatial parameters showed greater agreement with the gold standard compared to the temporal parameters. Moderate to good correlations (ICC = 0.5 - 0.9) are shown for eight parameters, including gait speed, stride length, stance time and cadence. Lower agreement, from poor to good, is shown for the temporal outputs: double support time, initial and terminal double support times (ICC= 0.299 – 0.501), across all methods.

Figure 5 presents Bland-Altman plots for the metrics with the highest and lowest correlations; cycle time (mainly moderate/large differences) and terminal double support time (mainly moderate difference). All parameters Bland-Altman plots are provided in the Appendix. The Bland-Altman plots illustrate the spread of the level of agreement between clinical gold standard MoCap and the MoveLab

® STP measurements for each of the participants by plotting the differences between the two methods against their average for each participant.

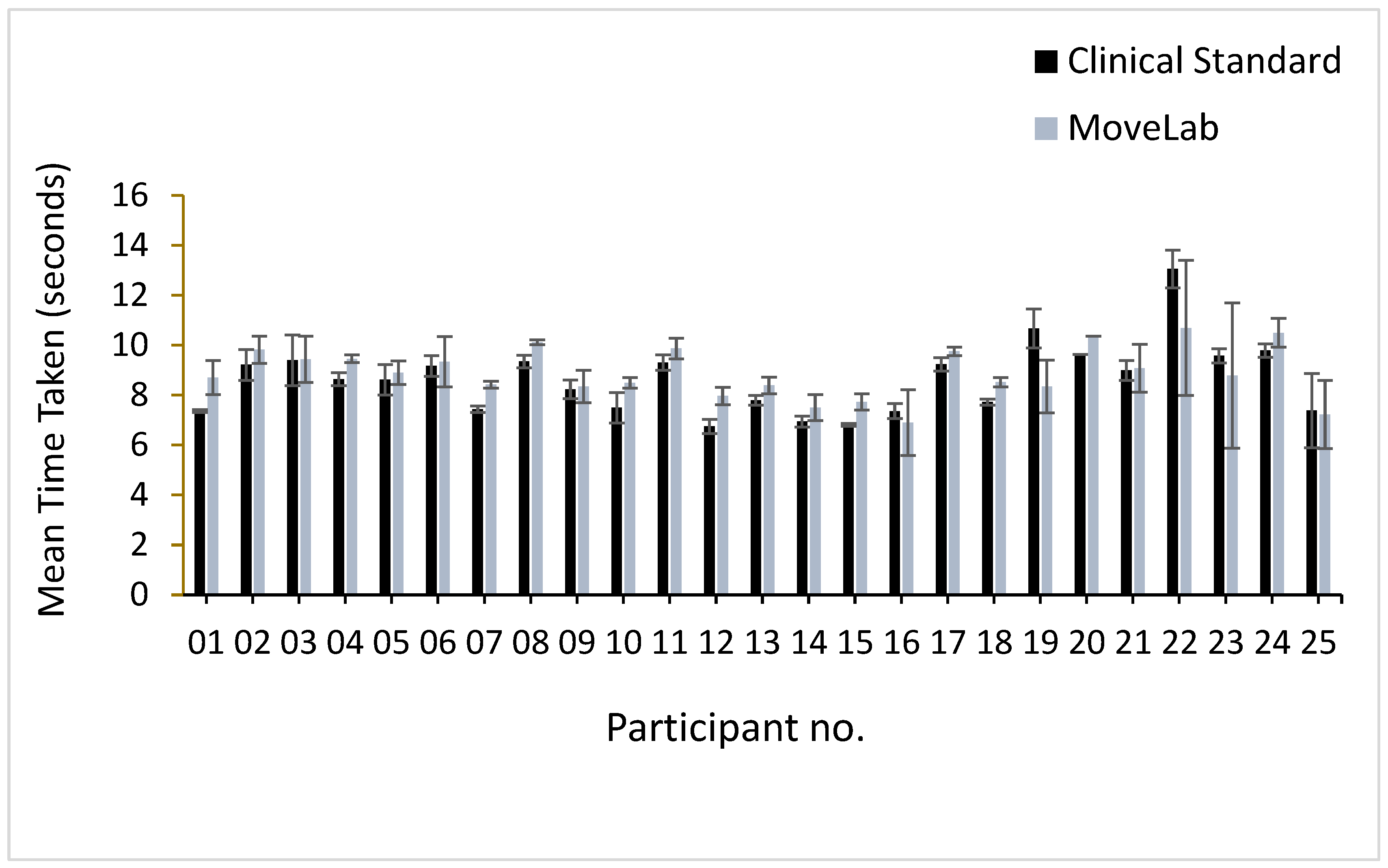

The mean TUG results and standard deviations recorded using both approaches, MoCap (represented as the ‘Clinical Standard’) and MoveLab

®, are presented in

Figure 6.

A similar trend is seen across most participants, with MoveLab

® estimating shorter times compared to the clinical standard results, with exception of participants 19, 22, 23 and 25. Given the variability in the time taken to complete the TUG observed in the comparative bar chart, it reflects the range expected for a healthy cohort [

16] (average age of 31.8 years ), which is < 12 seconds. An ICC of 0.757, across the 25 participants, indicates good agreement presented by MoveLab

® when compared to the ‘clinical standard’.

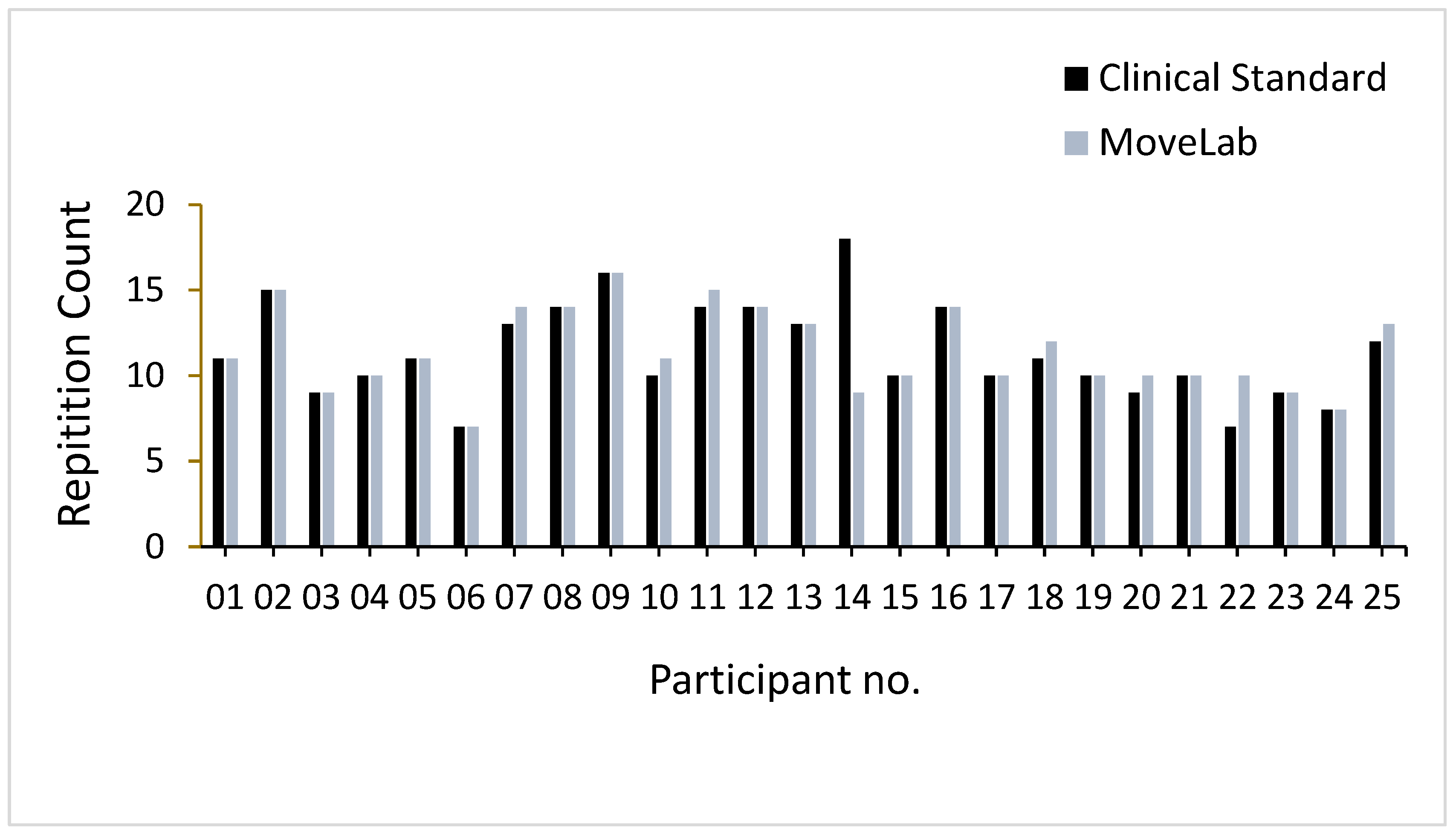

The STS results across all participants recorded using both approaches, MoCap (represented as the ‘Clinical Standard’) and MoveLab

®, (shown in

Figure 7). Excluding participant 14, the results indicate the same or a higher number of repetitions (in seven participants), recorded over the 30 seconds as compared to MoveLab

®. Participant 14 shows almost double the number of repetitions recorded using the ‘clinical standard’ compared to MoveLab

® and thus merits further examination.

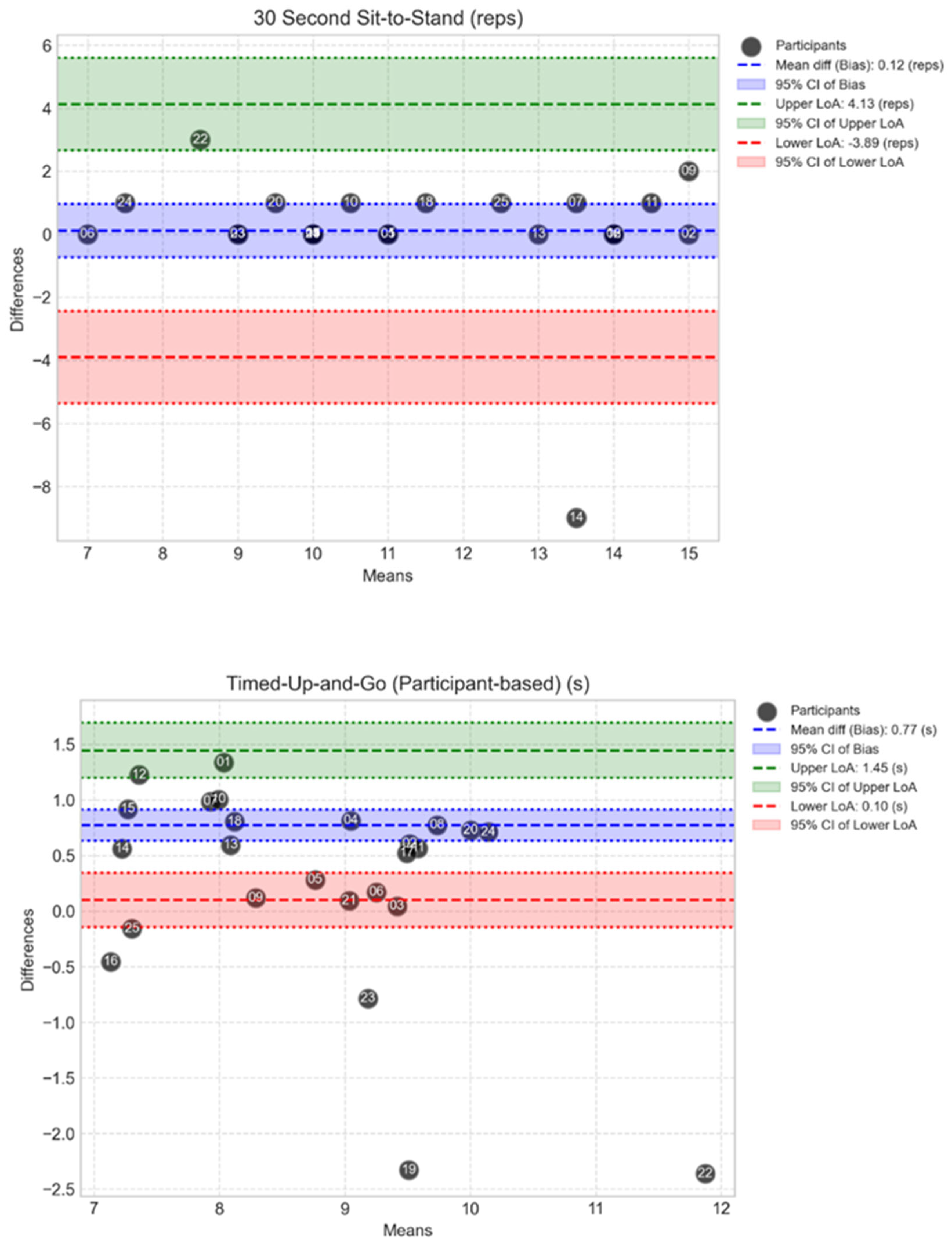

The Bland-Altman plots, shown in

Figure 8, indicate the spread of the difference between MoveLab

® data outputs for TUG and STS against ‘clinical standard’ MoCap for all participants. Moderate differences are seen for STS. Small to moderate differences can be observed for TUG.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess the reliability and validity of the MoveLab® (Agile Kinetic 2024) approach to measure gait spatiotemporal parameters (STPs), STS and TUG using a waist-worn mobile phone, compared to gold standard 3D marker-based motion capture (Qualisys AB, Sweden) and ‘Clinical Standard’ test methods. The MoveLab® DCA processing pipeline established for this study estimated gait STPs per subject and was trialled using nine different methods to estimate the gait STPs, STS and TUG, and then refined to reflect the entire population of the 25 participating subjects.

The ability to accurately measure STPs outside of a laboratory or clinical environment offers significant advantages in accessibility, cost-effectiveness, and efficiency in diagnosing and monitoring treatment outcomes [

2]. The sensor-based gait analysis system developed by MoveLab

®, presents a promising solution for real-world, low cost and unsupervised gait assessments, potentially enabling detection of mobility impairments, and aiding in rehabilitation strategies and monitoring.

In this study, MoveLab

® demonstrated moderate-to-good correlations with gold standard MoCap measurements for nine STP parameters, including gait speed, stride length, stance time, and cadence. These parameters are critical for assessing locomotor impairments in conditions such as cerebral palsy, stroke, and Parkinson’s disease, where subtle gait alterations can serve as early indicators of disease progression [

4]. Accurate, repeatable measurement of these gait characteristics in non-clinical settings, at an appropriate threshold of accuracy compared to clinical gold standard could support continuous patient monitoring and remote rehabilitation, improving accessibility for individuals with mobility disorders.

Although the MoveLab

® DCA processing pipeline established for this study showed strong results for key gait parameters, the algorithms exhibited poor correlations for double support and terminal double support phases, with a moderate correlation (0.501) for initial double support. These discrepancies could be attributed to the individual participants anatomical and functional variations. For example, left-right asymmetry, or differences in step timing detection, which are particularly relevant in pathologies characterised by asymmetric gait patterns, such as hemiplegic stroke and unilateral orthopaedic conditions [

17]. The lower accuracy of the MoveLab

® algorithm in these phases suggests that while MoveLab

® may be effective for general gait assessments, further development of the algorithms is required for its utility in detecting conditions where double support duration is a key diagnostic factor.

The STS and TUG are two of the OARSI [

16] recommended set of performance-based tests of physical function that are best suited for older individuals (> 40 years) diagnosed with hip and/or knee osteoarthritis (OA), including end stage disease or following joint replacement. They are intended for use by both clinicians and researchers as performance outcome measures and are viewed as complementary to established self-report measures such as questionnaires.

The Timed-Up-and-Go (TUG) test - a simple assessment often used to screen for frailty and fall risk in older adults, involves measuring the time it takes to rise from a chair, walk three meters, turn, walk back, and sit down. A longer TUG time, generally > 12-14 seconds, is associated with increased frailty and fall risk. The observed mean TUG results are variable and lie within the range expected for a healthy cohort when recorded using both MoCap and MoveLab® approaches (less than 12). The ICC, across the 25 participants, aligns with the small to moderate differences observed in the Bland-Altman plot, and demonstrates good agreement, indicating that the MoveLab® data processing pipeline is capable of providing a valid approach to measuring TUG.

The 30-second-Sit-to-Stand (STS) test - counting the number of times that a person can repeatedly stand from being seated on a chair and then sitting down again over a 30 second period, is used to assess lower body strength and is part of the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), commonly used for assessment of physical performance in older adults. The MoveLab

® processing pipeline for Thirty-Second STS was validated against the 25 participant trials, i.e., one trial per subject. The impact of data variability across the participant cohort [

16] was evaluated to provide a fair and accurate assessment of the approach to using the MoveLab

® platform with data collected via the waist-worn mobile phone. The output for subject 14 appears to be significantly worse compared with the other 24 subjects, where the system demonstrated comparable performance to gold standard. Upon investigation, the signal-to-noise ratio of this particular trial was found to be considerably lower compared to that for the other participants. This suggests that an external factor may have contributed to the noise for this recording. Due to the difficulty in recalling the subject for a retrial, it was decided to present the analysis including participant 14 data in the comparative variability observations (

Figure 7) but omitting it from the overall ICC calculations. Given the small sample size, the influence of individual trials on the analysis is not trivial. While the system demonstrated robustness in capturing the STS repetitions compared to gold standard, the ability to process outliers impacted by environmental conditions and trial discrepancies appears to be poor as evidenced by participant 14.

The misalignment of repetition counts observed for the STS when using the DCA developed for this study can be mitigated in the future commercial MoveLab® application through a built-in timer that alerts the user when the activity is starting, and a countdown timer which automatically stops after 30 seconds, providing a second alert. It is intended that the commercial application will include a two-stage methodology for handling outliers impacted by environmental conditions and trial discrepancies in STS assessments. If a first stage involving signal filtering does not adequately supress noise, the user will be asked to perform the assessment again. Where internet connectivity issues are present, these will be overcome automatically through a retry mechanism, whereby, if sensor data fails to upload the application will attempt to re-upload.

The limitations to this study should be considered and can present opportunities for future research to build on the current findings. Firstly, the difference in capture time between the MoveLab® device and the gold standard and clinical standard assessment methods may have contributed to the differences in output agreement, thus impacting the strength of correlations. The capture period for the MoveLab® device included some turns in the walking route and this has already been addressed in the MoveLab® algorithms. However, acceleration and changes in speed and gait pattern could affect the STP outputs.

Secondly, the recognised limitations to 3D gait analysis methods could contribute to errors in the MoCap data, including soft tissue artifact and incorrect or inaccurate marker placement, i.e., some movement of the markers on the skin during the activities due to inertial effects and inaccurate identification of bony landmarks on the skin relative the underlying bone. These can lead to inaccurate tracking of markers and calculation of the biomechanics parameters in the processing pipeline. However, for the STPs output in this study the impact would be expected to be minimal when compared to the joint rotations that are analysed in a full clinical gait analysis. Future comparative studies could involve comparison of MoveLab® with portable gait analysis devices or wearable motion analysis systems however they are not generally considered as gold standard for clinical assessment.

Finally, this study was limited to a cohort of twenty-five volunteers who were recruited as self-reported, healthy participants. To address potential limitations that may arise when with the current algorithms and processing pipeline when applied to cohorts across typical pathologies, e.g., osteoarthritis, stroke, Parkinson’s, it is also recommended to perform further developmental and comparative studies. These should involve altered or compensatory gait styles, for example, with simulated or real gait disorders, and clearly identified clinical patient cohorts (for clinical benchmarking to current markers and assessments). This should also include an assessment of alternative options for mobile phone placement to allow for a range of patient morphologies, abilities and clothing.

In identifying these key limitations, it must be noted that the data collection protocol and processing pipeline was adopted to assess the ability of MoveLab® to recreate a set of reliable and clinically valid outputs when compared to a gold standard and clinical standard assessment. The resulting data has provided the first evidence of validation for several key gait STPs and two clinically accepted performance-based assessments, along with clearly defined opportunities to address the identified limitations.

5. Conclusions

The study provided the first evidence that the MoveLab® data collection and processing pipeline capable producing acceptable to excellent results for STP parameters when compared to gold standard MoCap used for in Clinical Gait Analysis. MoveLab® has also been demonstrated to offer good results when measuring STS and TUG.

Based on the findings and recommendations of this initial comparative study, the DCA and processing pipeline should be considered to provide a route to valid and reliable measurement of spatiotemporal parameters in healthy adults when they are performing activities in a controlled environment. The approach offers opportunities for future practical, fast and large-scale data collection and analysis to clinicians and researchers who are considering analysis of activities of daily living beyond a laboratory or clinical setting

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, ZGL, JW, AA, PB and CH; formal analysis, KP, COF, AA, ZGL, JW, PB and CH; investigation, KP, COF, ZGL, JW, PB, AA and CH; resources, CH, PB; data curation, KP, COF, AA; writing—original draft preparation, JW, ZGL, KP, COF, PB, AA, FH; writing—review and editing, CH; visualization, KP, COF, AA; supervision, CH; project administration, JW; funding acquisition, PB, CH, JW. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research was funded by Innovate UK Advancing Precision Medicine 2023-2025, Award number 10070944. Agile Kinetic and Cardiff University have previously collaborated under research funded by Accelerate Wales, Life Sciences Hub Programme from Welsh Government European Regional Development Fund (PR-0345).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of School of Engineering Review Board, Cardiff University (14.02.24 (Version 7), approved 28.02.24).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Agile Kinetic Limited are a UK registered SME. Peter Bishop is a shareholder in Agile Kinetic Limited.

Appendix A

This provides supplementary graphical information including Bland-Altman plots showing spread of MoveLab

® STP data against gold standard MoCap for all participants (

Figure A1 and A2) and a Boxplot of gait STPs for gold standard MoCap and MoveLab

® demonstrator algorithms for all participants (

Figure A3).

Figure A1.

Bland-Altman plots to show the spread of MoveLab® spatial parameter data outputs against gold standard MoCap for all participants.

Figure A1.

Bland-Altman plots to show the spread of MoveLab® spatial parameter data outputs against gold standard MoCap for all participants.

Figure A2.

Bland-Altman plots to show the spread of MoveLab® temportal data outputs against gold standard MoCap for all participants.

Figure A2.

Bland-Altman plots to show the spread of MoveLab® temportal data outputs against gold standard MoCap for all participants.

Figure A3.

Boxplot of gait STPs from gold standard MoCap and MoveLab® demonstrator algorithms for all participants.

Figure A3.

Boxplot of gait STPs from gold standard MoCap and MoveLab® demonstrator algorithms for all participants.

References

- Chigboh, V. M.; Zouo, S. J. C.; Olamijuwon, J., Health data analytics for precision medicine: A review of current practices and future directions. International Medical Science Research Journal 2024, 4, (11), 973-984.

- Pendyala, V. S.; Kamdar, K.; Mulchandani, K., Automated Research Review Support Using Machine Learning, Large Language Models, and Natural Language Processing. Electronics 2025, 14, (2), 256.

- Hasan, N.; Ahmed, M. F., Wearable Technology for Elderly Care: Integrating Health Monitoring and Emergency Alerts. Journal of Computer Networks and Communications 2024, 2024, (1).

- Nocilli, M.; Scafa, S.; La Porta, N.; Ghislieri, M.; Agostini, V.; Moraud, E. M.; Puiatti, A., G.A.I.T: gait analysis interactive tool a pipeline for automatic detection of gait events across different motor impairments. Signal, Image and Video Processing 2024, 18, (12), 8499-8506.

- Adamowicz, L.; Christakis, Y.; Czech, M. D.; Adamusiak, T., SciKit Digital Health: Python Package for Streamlined Wearable Inertial Sensor Data Processing. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 2022, 10, (4), e36762.

- Gasparutto, X.; Bonnefoy-Mazure, A.; Attias, M.; Turcot, K.; Armand, S.; Miozzari, H. H., Comprehensive analysis of total knee arthroplasty kinematics and functional recovery: Exploring full-body gait deviations in patients with knee osteoarthritis. PLoS One 2024, 19, (12), e0314991.

- Shahar, R. T.; Agmon, M., Gait Analysis Using Accelerometry Data from a Single Smartphone: Agreement and Consistency between a Smartphone Application and Gold-Standard Gait Analysis System. Sensors 2021, 21, (22), 7497.

- Yagi, K.; Sugiura, Y.; Hasegawa, K.; Saito, H., Gait Measurement at Home Using A Single RGB Camera. Gait and Posture 2020, 76, 136-140.

- Boswell, M. A.; Kidziński, Ł.; Hicks, J. L.; Uhlrich, S. D.; Falisse, A.; Delp, S. L., Smartphone videos of the sit-to-stand test predict osteoarthritis and health outcomes in a nationwide study. npj Digital Medicine 2023, 6, (1), 32.

- Hamilton, R. I.; Glavcheva-Laleva, Z.; Haque Milon, M. I.; Anil, Y.; Williams, J.; Bishop, P.; Holt, C., Comparison of computational pose estimation models for joint angles with 3D motion capture. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 2024, 40, 315-319.

- Podsiadlo, D.; Richardson, S., The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991, 39, (2), 142-8.

- Duarte Wisnesky, U.; Olson, J.; Paul, P.; Dahlke, S.; Slaughter, S. E.; de Figueiredo Lopes, V., Sit-to-stand activity to improve mobility in older people: A scoping review. Int J Older People Nurs 2020, 15, (3), e12319.

- Coleman, G.; Dobson, F.; Hinman, R. S.; Bennell, K.; White, D. K., Measures of Physical Performance. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2020, 72 Suppl 10, 452-485.

- Cappozzo, A.; Catani, F.; Croce, U. D.; Leardini, A., Position and orientation in space of bones during movement: anatomical frame definition and determination. Clin Biomech (Bristol) 1995, 10, (4), 171-178.

- Koo, T. K.; Li, M. Y., A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J Chiropr Med 2016, 15, (2), 155-63.

- Dobson, F.; Hinman, R. S.; Roos, E. M.; Abbott, J. H.; Stratford, P.; Davis, A. M.; Buchbinder, R.; Snyder-Mackler, L.; Henrotin, Y.; Thumboo, J.; Hansen, P.; Bennell, K. L., OARSI recommended performance-based tests to assess physical function in people diagnosed with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013, 21, (8), 1042-52.

- Vismara, L.; Cimolin, V.; Buffone, F.; Bigoni, M.; Clerici, D.; Cerfoglio, S.; Galli, M.; Mauro, A., Brain Asymmetry and Its Effects on Gait Strategies in Hemiplegic Patients: New Rehabilitative Conceptions. Brain Sciences 2022, 12, (6), 798.

Figure 1.

A diagram showing the flow of raw sensor data through the test harness.

Figure 1.

A diagram showing the flow of raw sensor data through the test harness.

Figure 2.

CAST marker set used during MoCap data collection (Capozzo 1995).

Figure 2.

CAST marker set used during MoCap data collection (Capozzo 1995).

Figure 3.

Static of marker set and pouch placement with phone in-situ a) anterior view b) posterior view.

Figure 3.

Static of marker set and pouch placement with phone in-situ a) anterior view b) posterior view.

Figure 4.

Walking trial (a), TUG (b), STS (c and d).

Figure 4.

Walking trial (a), TUG (b), STS (c and d).

Figure 5.

Bland-Altman plots show the spread of the MoveLab® data outputs for cycle time (s) (top plot) and terminal double support time (s) (bottom plot), against gold standard MoCap for all participants. The plots compare cycle time measurements between two methods across the 25 participants. The x-axis shows the mean cycle time for each participant across both methods, while the y-axis shows the difference between the two methods. The long-dashed blue line represents the mean difference (bias), with dashed blue lines showing the limits of agreement (mean ± 1.96 SD). Coloured bands indicate different levels of agreement: red (small differences), blue (moderate), and green (larger).

Figure 5.

Bland-Altman plots show the spread of the MoveLab® data outputs for cycle time (s) (top plot) and terminal double support time (s) (bottom plot), against gold standard MoCap for all participants. The plots compare cycle time measurements between two methods across the 25 participants. The x-axis shows the mean cycle time for each participant across both methods, while the y-axis shows the difference between the two methods. The long-dashed blue line represents the mean difference (bias), with dashed blue lines showing the limits of agreement (mean ± 1.96 SD). Coloured bands indicate different levels of agreement: red (small differences), blue (moderate), and green (larger).

Figure 6.

Mean TUG results with standard deviations recorded using both approaches, MoCap (represented as the ‘Clinical Standard’) and MoveLab®, across all 25 participants for 5 repetitions.

Figure 6.

Mean TUG results with standard deviations recorded using both approaches, MoCap (represented as the ‘Clinical Standard’) and MoveLab®, across all 25 participants for 5 repetitions.

Figure 7.

STS results recorded using both approaches, MoCap (represented as the ‘Clinical Standard’) and MoveLab®, across all 25 participants.

Figure 7.

STS results recorded using both approaches, MoCap (represented as the ‘Clinical Standard’) and MoveLab®, across all 25 participants.

Figure 8.

Bland-Altman plots show the spread of MoveLab® data outputs for STS (repetition count) (top plot) and TUG (s) (bottom plot), against gold standard MoCap for all participants. The plots compare cycle time measurements between two methods across the 25 participants. The x-axis shows the mean output for each participant across both methods, while the y-axis shows the difference between the two methods. The long-dashed blue line represents the mean difference (bias), with dashed blue lines showing the limits of agreement (mean ± 1.96 SD). Coloured bands indicate different levels of agreement: red (small differences), blue (moderate), and green (larger).

Figure 8.

Bland-Altman plots show the spread of MoveLab® data outputs for STS (repetition count) (top plot) and TUG (s) (bottom plot), against gold standard MoCap for all participants. The plots compare cycle time measurements between two methods across the 25 participants. The x-axis shows the mean output for each participant across both methods, while the y-axis shows the difference between the two methods. The long-dashed blue line represents the mean difference (bias), with dashed blue lines showing the limits of agreement (mean ± 1.96 SD). Coloured bands indicate different levels of agreement: red (small differences), blue (moderate), and green (larger).

Table 1.

The Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC), for comparison of the STPs from MoveLab® with MoCap (means), where M represents the utilised algorithm approach.

Table 1.

The Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC), for comparison of the STPs from MoveLab® with MoCap (means), where M represents the utilised algorithm approach.

| STP |

Mean± SD

|

ICC |

| MoCap |

|

M1 |

M2 |

M3 |

M4 |

M5 |

M6 |

M7 |

M8 |

M9 |

| Speed (m/s) |

1.28± 0.11 |

0.742 |

0.716 |

0.691 |

0.687 |

0.745 |

0.761 |

0.709 |

0.705 |

0.758 |

| Stride Length (m) |

1.31± 0.03 |

0.595 |

0.543 |

0.590 |

0.553 |

0.613 |

0.591 |

0.572 |

0.543 |

0.608 |

| Step Length (m) |

0.66± 0.02 |

0.747 |

0.573 |

0.745 |

0.578 |

0.713 |

0.686 |

0.743 |

0.555 |

0.706 |

| Step Time (s) |

0.52± 0.02 |

0.851 |

0.776 |

0.851 |

0.776 |

0.866 |

0.866 |

0.862 |

0.786 |

0.866 |

| Cycle Time (s) |

1.03± 0.02 |

0.887 |

0.853 |

0.887 |

0.853 |

0.893 |

0.893 |

0.894 |

0.86 |

0.893 |

| Stance Time (s) |

0.65± 0.02 |

0.850 |

0.831 |

0.850 |

0.831 |

0.864 |

0.864 |

0.852 |

0.827 |

0.864 |

| Swing Time (s) |

0.38± 0.01 |

0.658 |

0.501 |

0.658 |

0.501 |

0.676 |

0.676 |

0.642 |

0.513 |

0.676 |

| Double Support (s) |

0.27± 0.02 |

0.318 |

0.430 |

0.318 |

0.430 |

0.485 |

0.485 |

0.321 |

0.418 |

0.485 |

| Initial Double Support (s) |

0.14± 0.01 |

0.339 |

0.477 |

0.339 |

0.477 |

0.501 |

0.501 |

0.334 |

0.458 |

0.501 |

| Terminal Double Support (s) |

0.13± 0.01 |

0.299 |

0.341 |

0.299 |

0.341 |

0.43 |

0.43 |

0.306 |

0.339 |

0.43 |

| Cadence (100 steps/min) |

1.17± 0.04 |

0.859 |

0.826 |

0.859 |

0.826 |

0.863 |

0.863 |

0.868 |

0.834 |

0.863 |

Table 2.

The mean differences between the MoveLab® STP outputs when compared to the MoCap means, where M represents the utilised algorithm approach.

Table 2.

The mean differences between the MoveLab® STP outputs when compared to the MoCap means, where M represents the utilised algorithm approach.

| STP |

Mean± SD

|

Mean Difference |

| MoCap |

|

M1 |

M2 |

M3 |

M4 |

M5 |

M6 |

M7 |

M8 |

M9 |

| Speed (m/s) |

1.28± 0.11 |

+0.084 |

-0.033 |

+0.095 |

-0.027 |

+0.048 |

+0.035 |

+0.102 |

-0.020 |

+0.041 |

| Stride Length (m) |

1.31± 0.03 |

-0.019 |

-0.140 |

-0.005 |

-0.140 |

-0.053 |

-0.067 |

+0.005 |

-0.130 |

-0.060 |

| Step Length (m) |

0.66± 0.02 |

-0.003 |

-0.068 |

+0.004 |

-0.064 |

-0.245 |

-0.031 |

+0.007 |

-0.064 |

-0.028 |

| Step Time (s) |

0.52± 0.02 |

-0.050 |

-0.049 |

-0.050 |

-0.049 |

-0.048 |

-0.048 |

-0.049 |

-0.049 |

-0.048 |

| Cycle Time (s) |

1.03± 0.02 |

-0.080 |

-0.078 |

-0.080 |

-0.078 |

-0.077 |

-0.077 |

-0.079 |

-0.077 |

-0.077 |

| Stance Time (s) |

0.65± 0.02 |

-0.046 |

-0.093 |

-0.046 |

-0.093 |

-0.069 |

-0.069 |

-0.046 |

-0.094 |

-0.070 |

| Swing Time (s) |

0.38± 0.01 |

-0.038 |

+0.009 |

-0.038 |

+0.009 |

-0.012 |

-0.012 |

-0.037 |

+0.010 |

-0.012 |

| Double Support (s) |

0.27± 0.02 |

-0.024 |

-0.117 |

-0.024 |

-0.117 |

-0.070 |

-0.070 |

-0.025 |

-0.118 |

-0.071 |

| Initial Double Support (s) |

0.14± 0.01 |

-0.012 |

-0.057 |

-0.012 |

-0.057 |

-0.035 |

-0.035 |

-0.012 |

-0.058 |

-0.035 |

| Terminal Double Support (s) |

0.13± 0.01 |

-0.013 |

-0.059 |

-0.013 |

-0.059 |

-0.026 |

-0.036 |

-0.013 |

-0.058 |

-0.036 |

| Cadence (100 steps/min) |

1.17± 0.04 |

+0.076 |

+0.072 |

+0.076 |

+0.072 |

+0.073 |

+0.073 |

+0.076 |

+0.071 |

+0.073 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).