Submitted:

07 March 2024

Posted:

08 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Participants

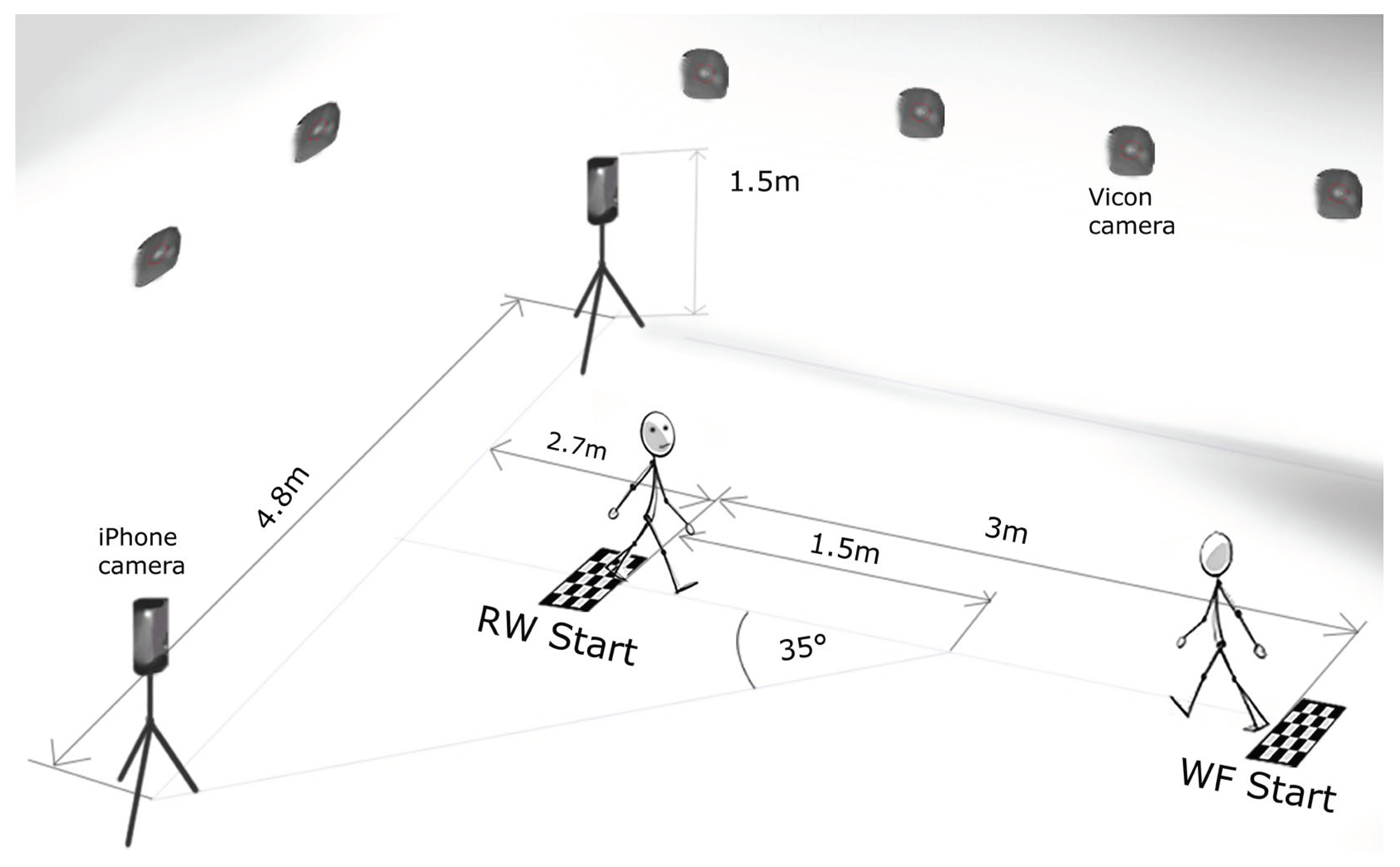

Measurement Setup

Data Analysis

3. Results

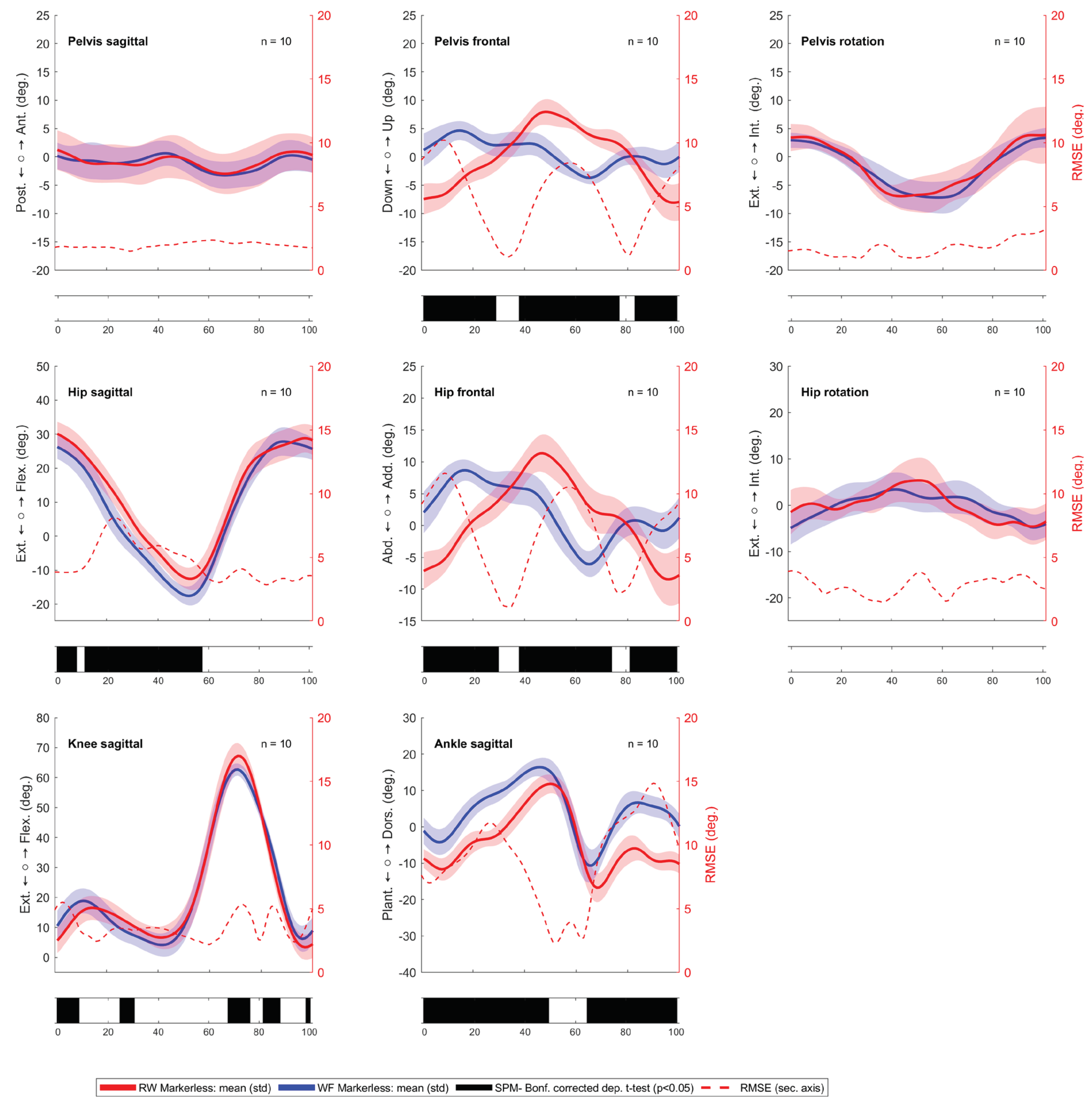

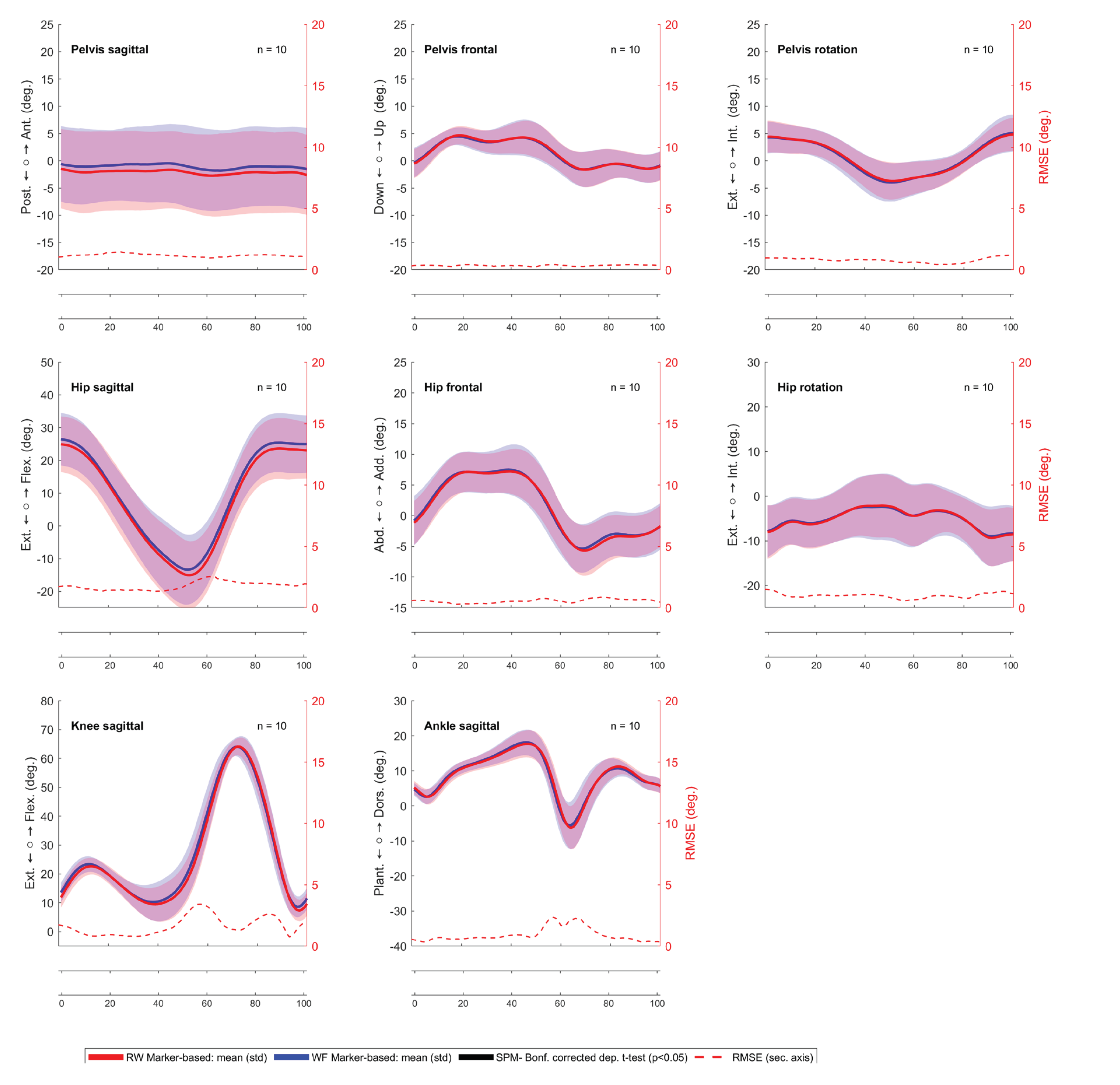

3.1. Comparing Walking Directions in the Markerless System

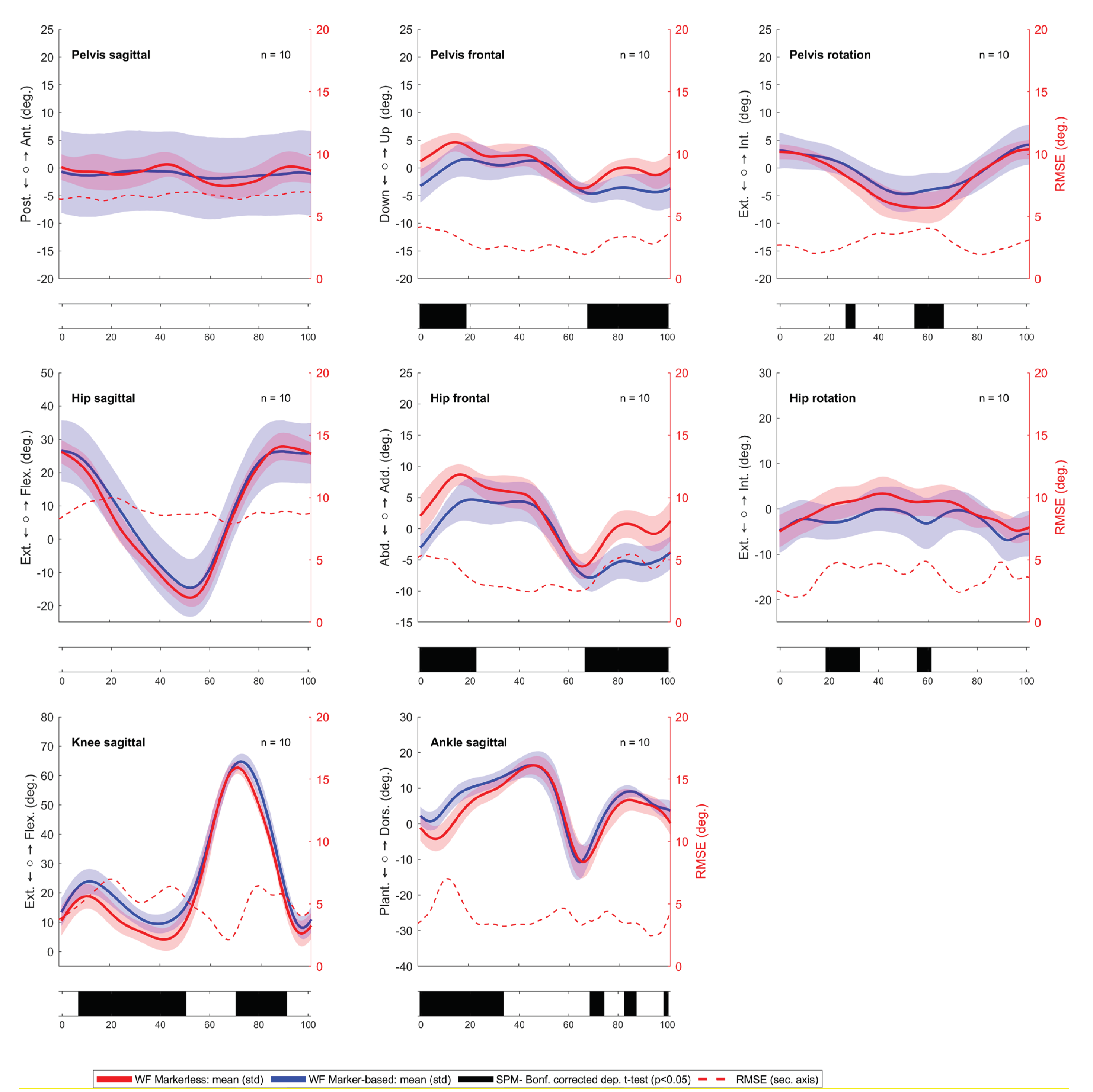

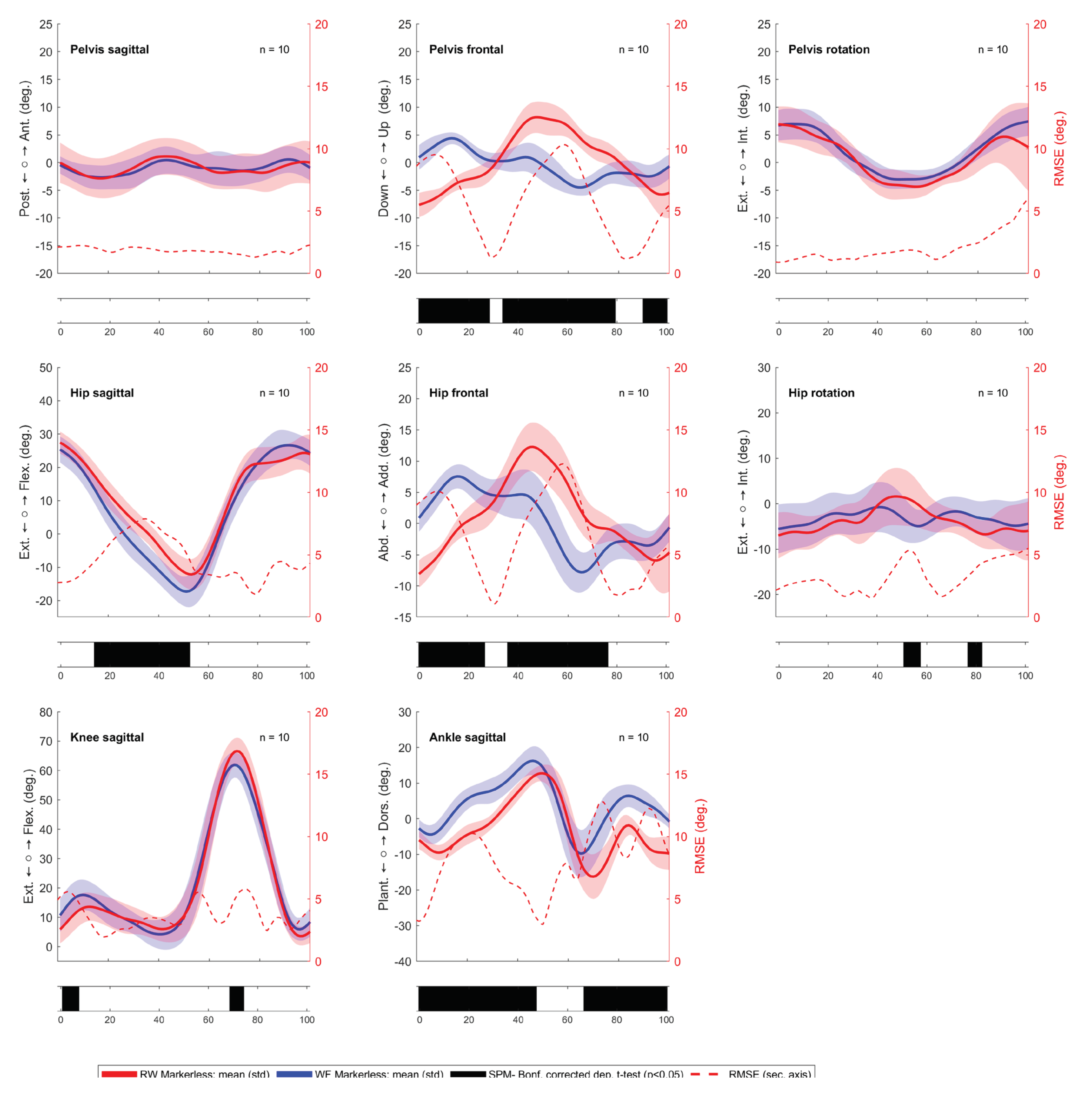

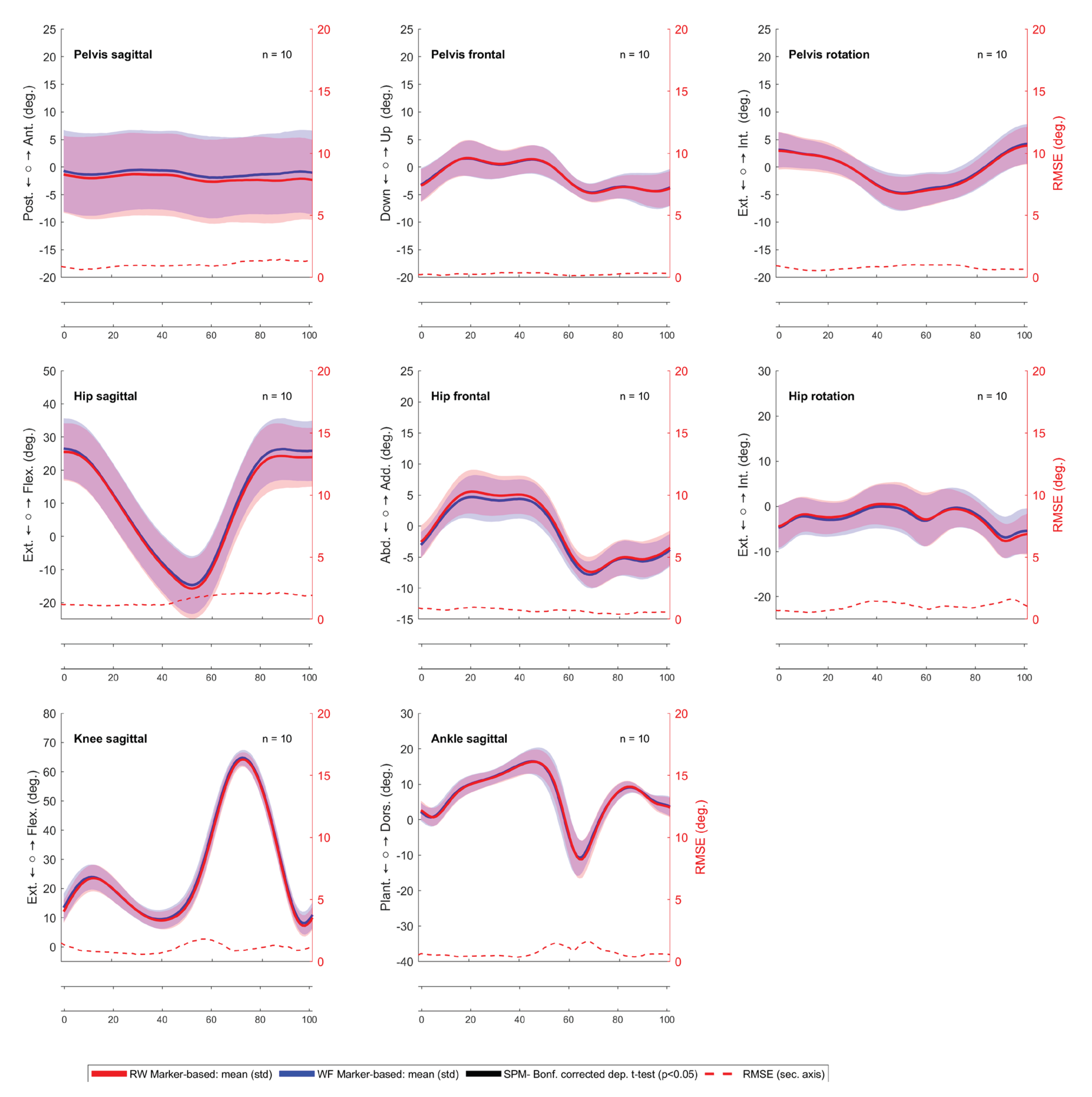

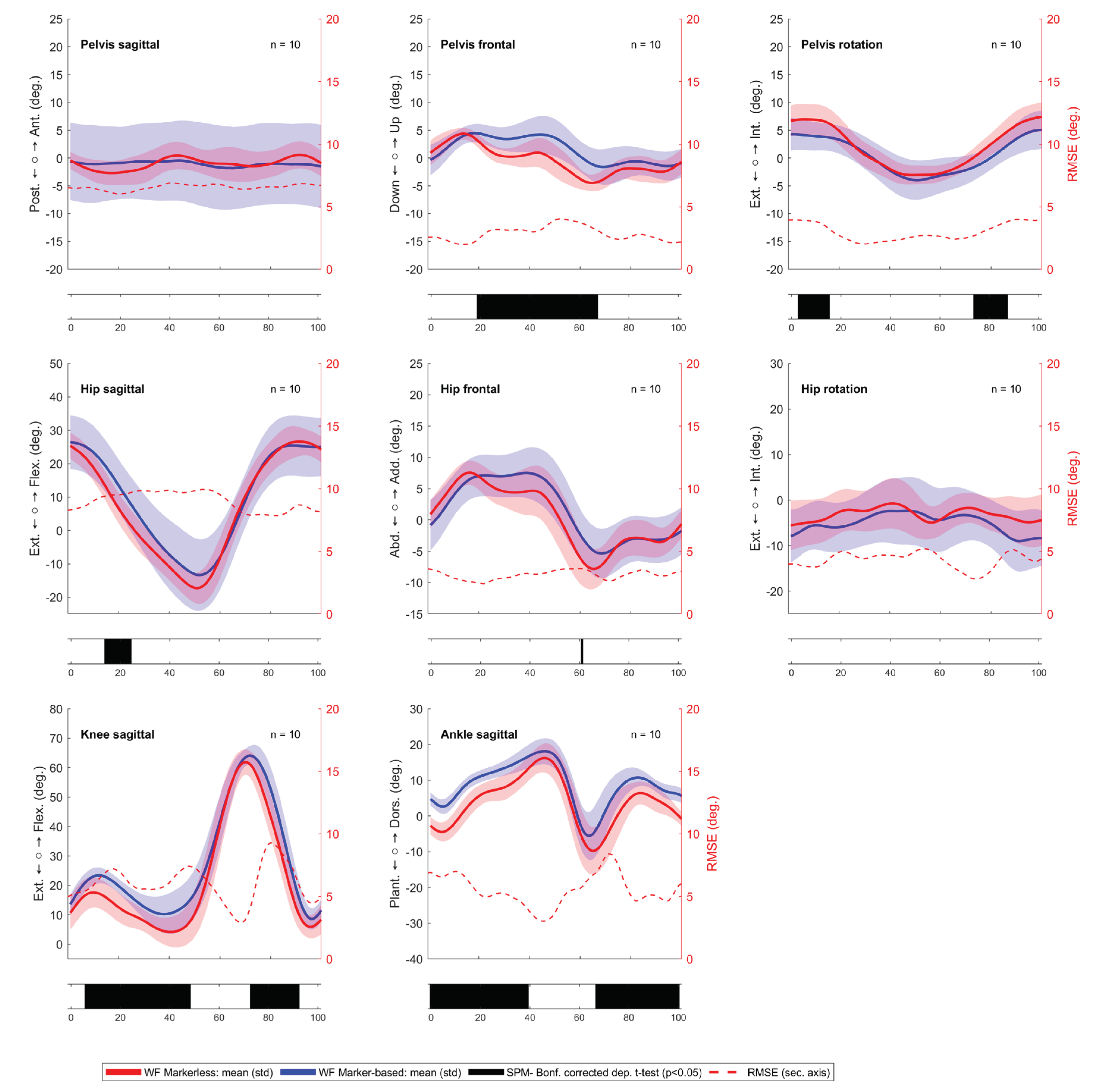

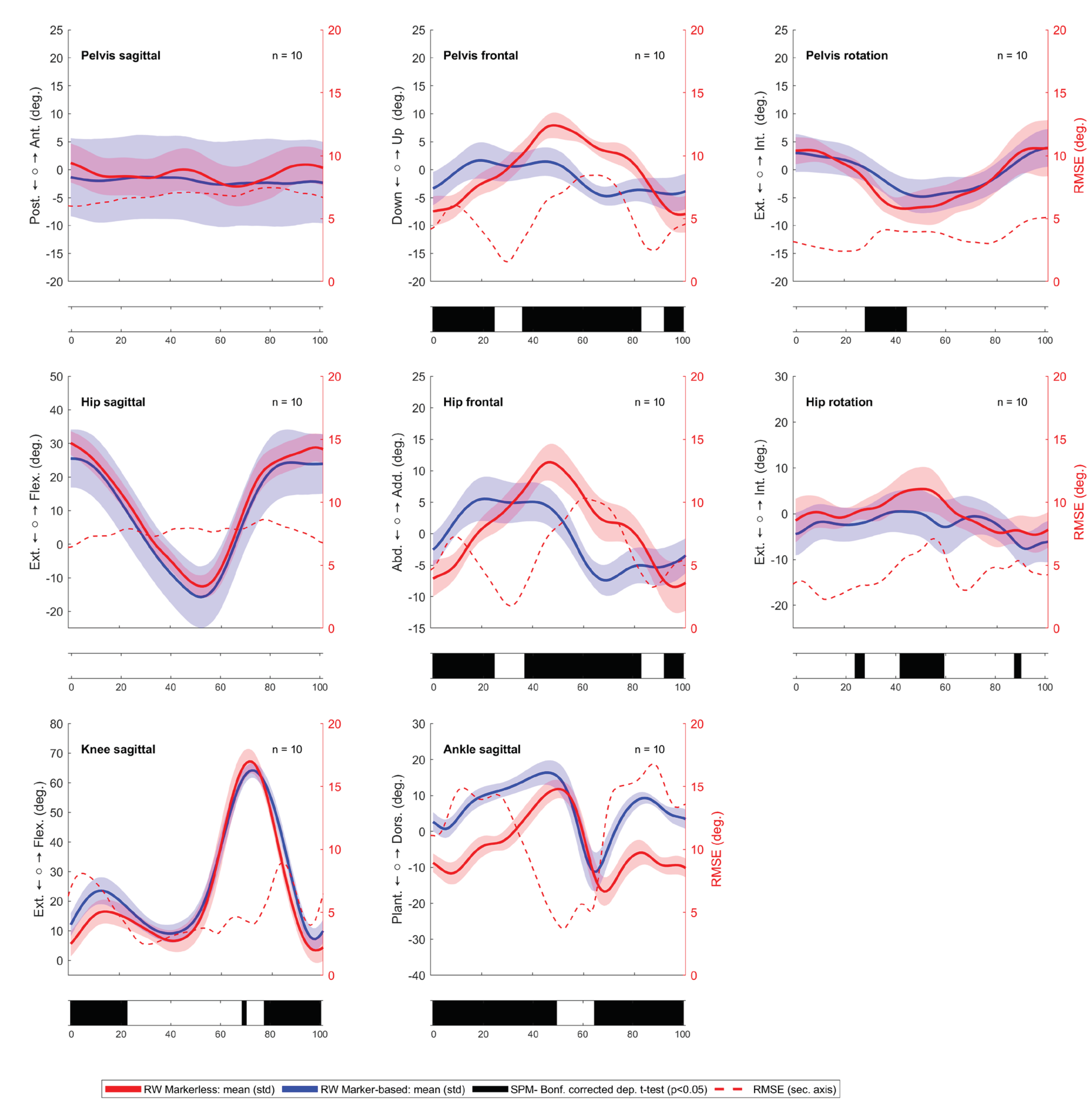

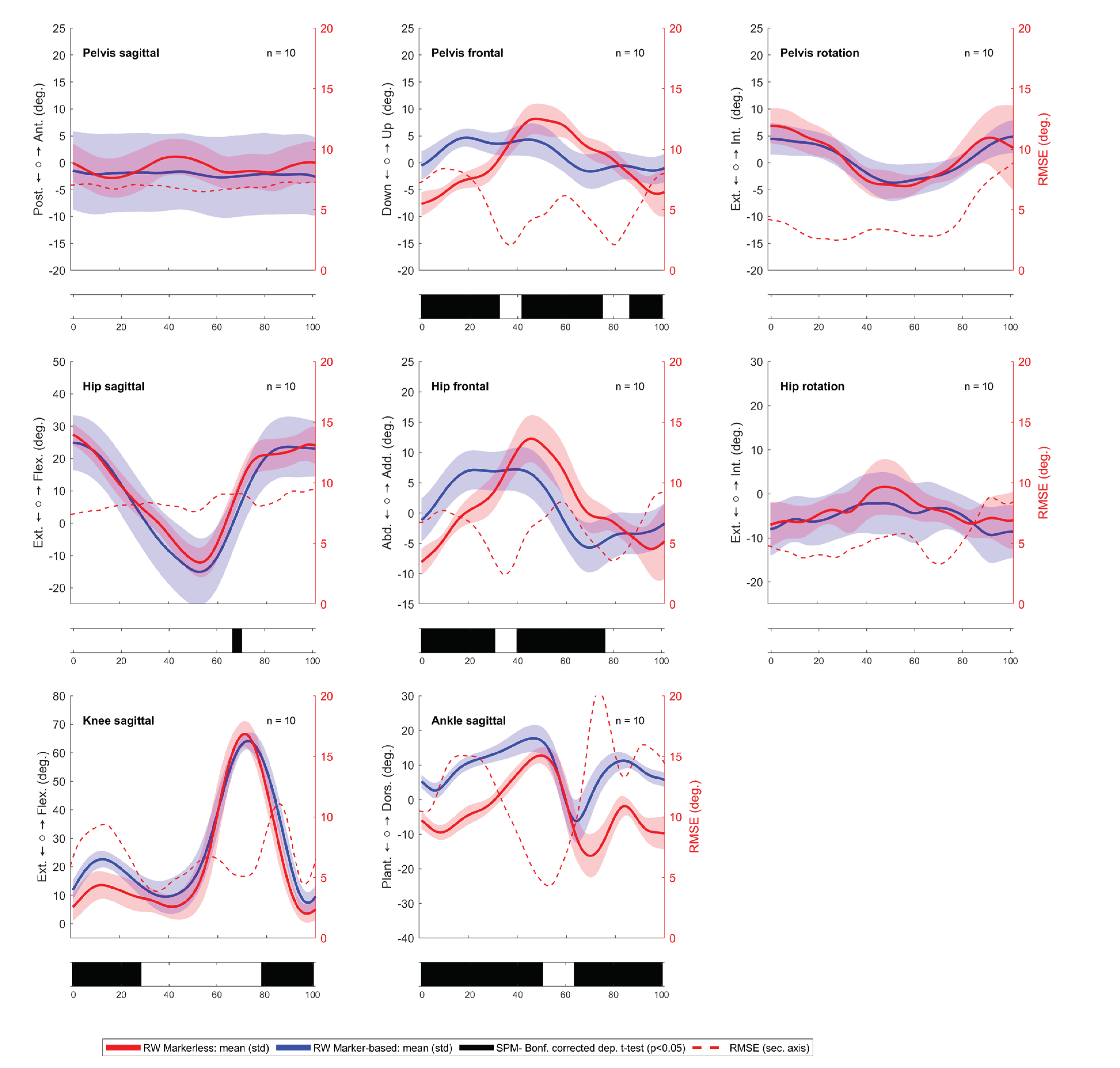

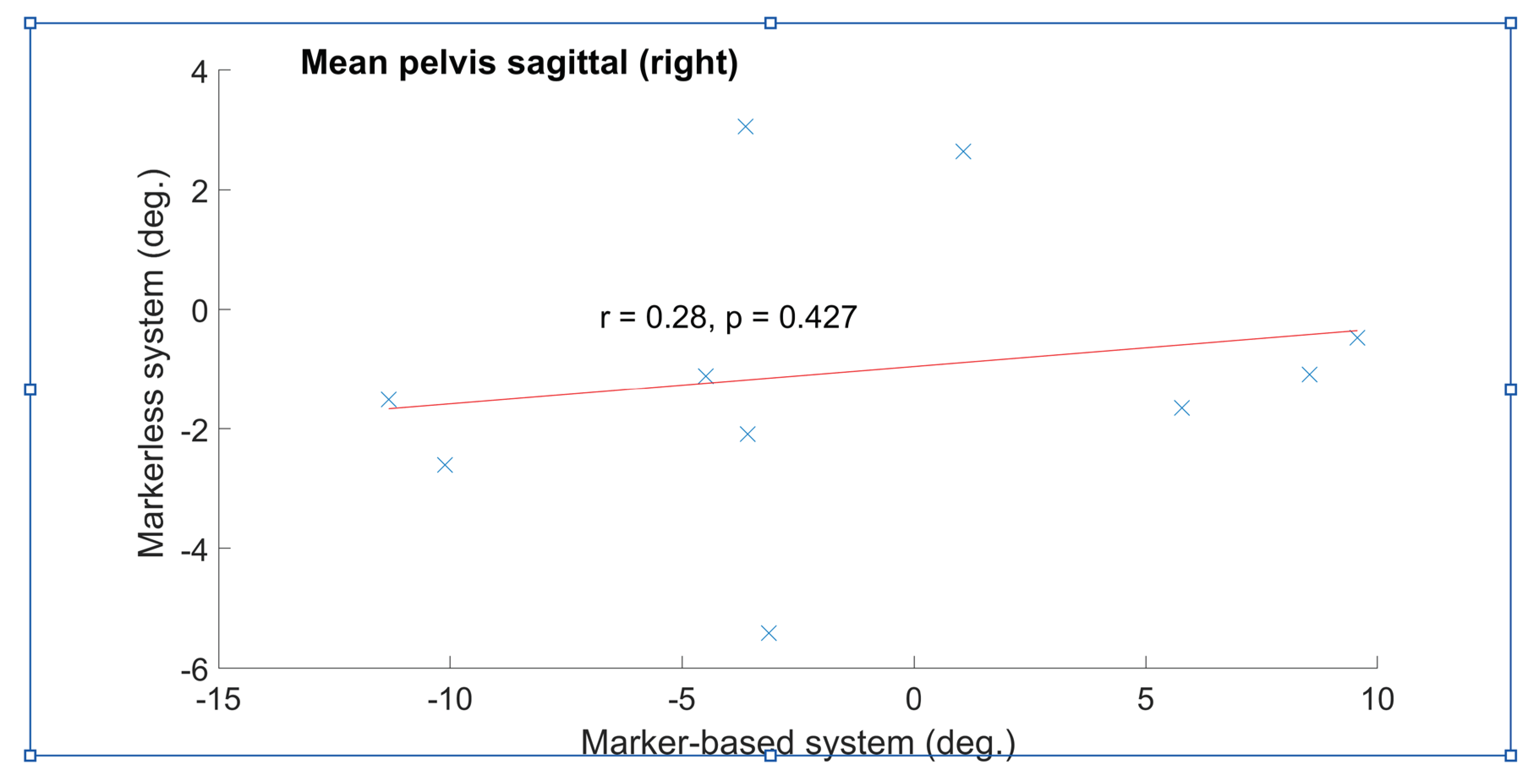

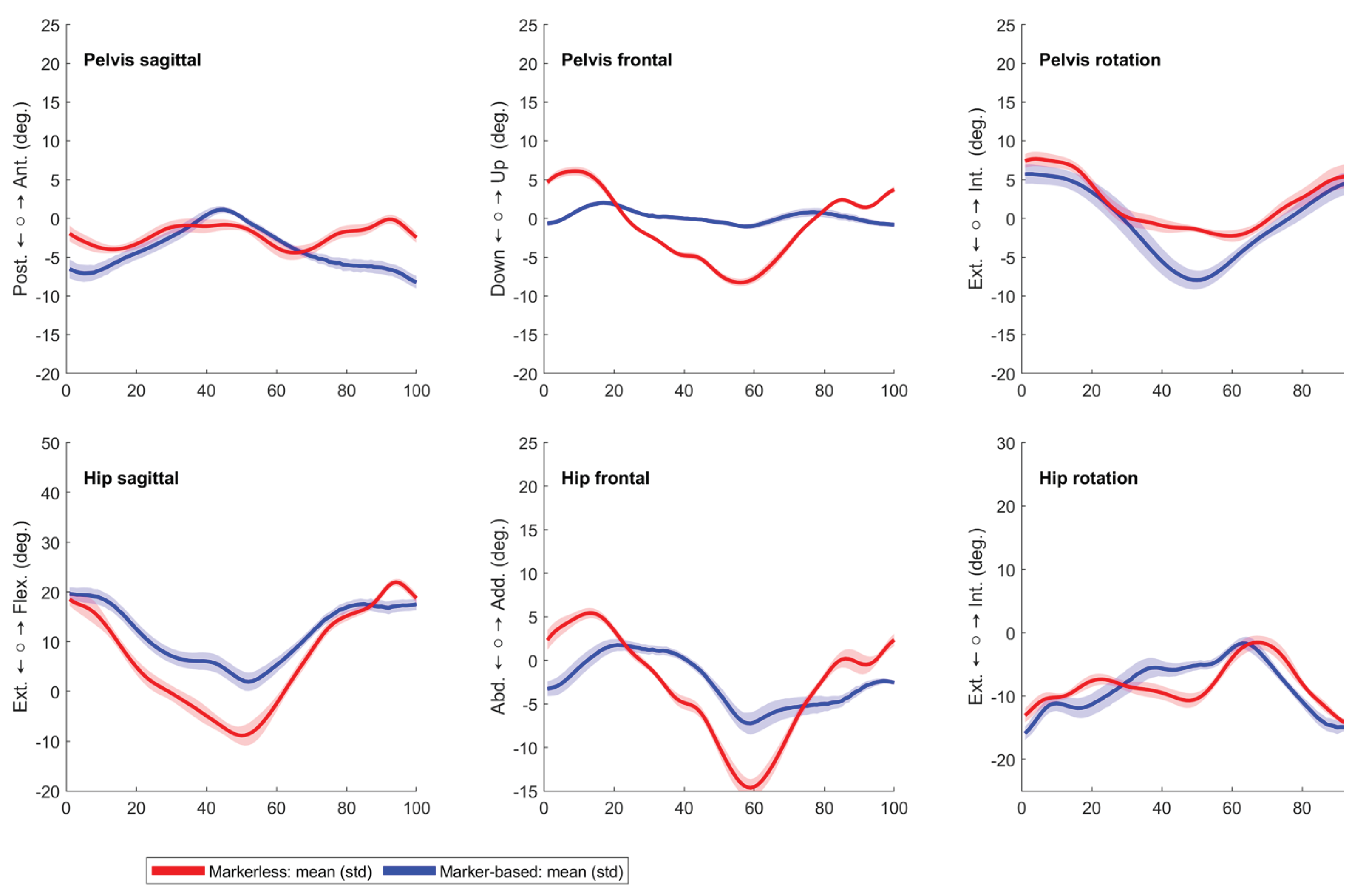

3.2. Comparing the Markerless against the Marker-Based System

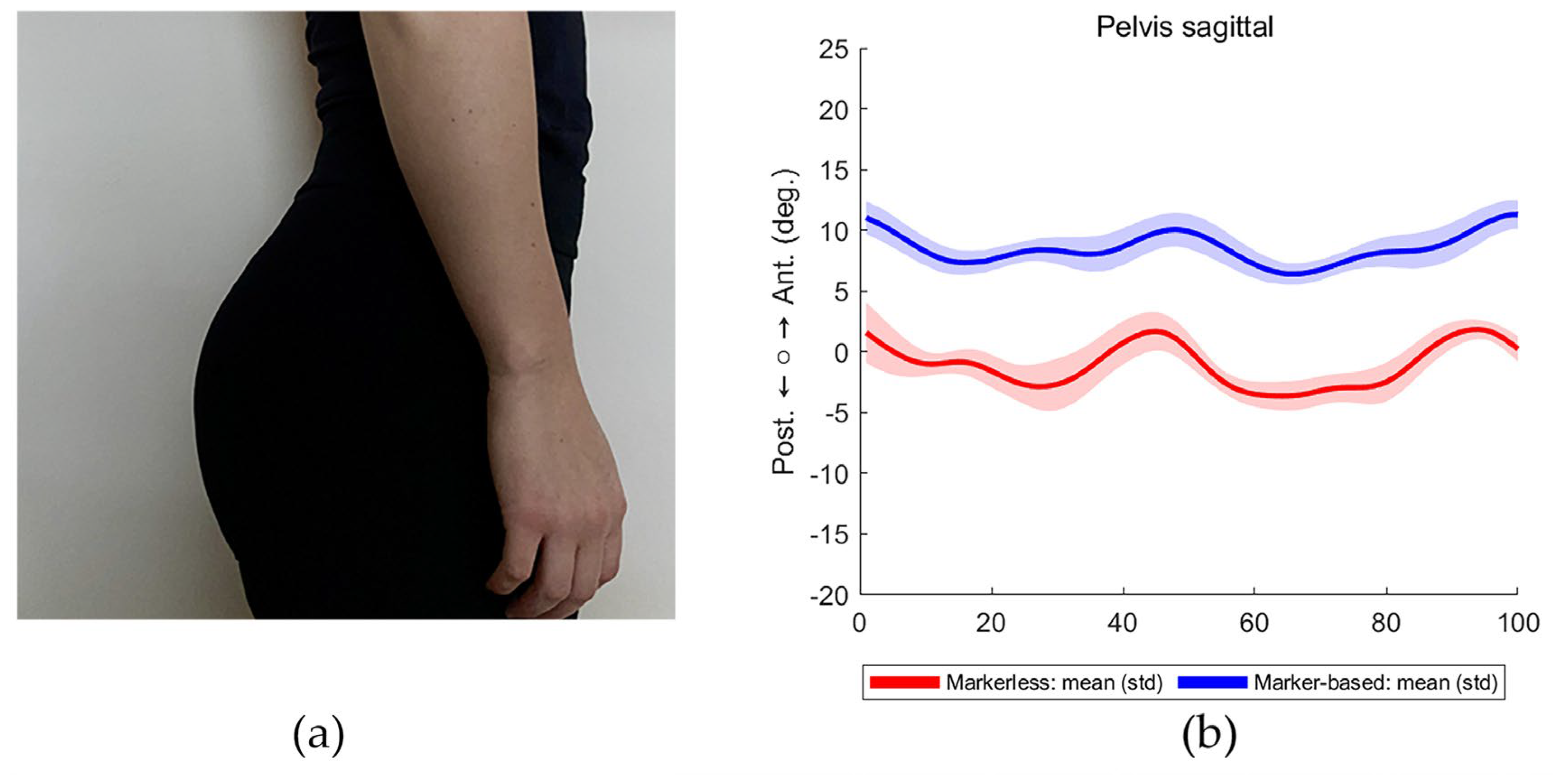

3.3. Case section

3.3.1. Visible Lordosis

3.3.2. Pelvic Movement in a Participant with Hip Osteoarthritis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Declaration of Competing Interest

Appendix A

| Parameter | WF | RW | Difference | Spearman correlation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| right | left | right | left | right | left | Right | left | |

| Mean (std) |

Mean (std) |

Mean (std) |

Mean (std) |

Mean (std) |

Mean (std) |

Corr (p-value) | Corr (p-value) | |

| Stride length (m) | 1.30 (0.12) | 1.30 (0.12) | 1.30 (0.12) | 1.28 (0.12) | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.98 (<0.001) * | 0.89 (0.001) * |

| Step width (m) | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.12 (0.02) | 0.11 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.83 (0.01) * | 0.85 (0.004) * |

| Step length (m) | 0.65 (0.06) | 0.65 (0.06) | 0.63 (0.07) | 0.64 (0.06) | 0.02 (0.05) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.68 (0.04) * | 0.96 (<0.001) * |

| Gait speed (m/s) | 1.23 (0.13) | 1.24 (0.14) | 1.21 (0.13) | 1.23 (0.14) | -0.02 (0.04) | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.92 (<0.001) * | 0.99 (<0.001) * |

| Pelvis tilt mean (°) | -1.0 (2.4) | -1.0 (2.3) | -0.8 (3.4) | -0.9 (3.3) | 0.18 (2.21) | 0.07 (2.02) | 0.61 (0.066) | 0.66 (0.044) * |

| Pelvis obliquity mean (°) | 0.7 (0.7) | -0.4 (0.6) | -0.0 (0.9) | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.69 (0.80) | 0.68 (0.64) | 0.43 (0.218) | 0.55 (0.104) |

| Pelvis obliquity ROM (°) | 9.6 (2.5) | 10.1 (2.4) | 17.4 (4.1) | 18.3 (3.6) | 7.77 (4.94) | 8.23 (3.65) | 0.14 (0.707) | 0.38 (0.279) |

| Pelvis obliquity IC (°) | 1.4 (2.9) | 1.1 (2.2) | -7.4 (2.7) | -7.6 (2.2) | 8.75 (1.81) | 8.72 (1.55) | 0.44 (0.204) | 0.68 (0.035) * |

| Pelvis rotation ROM (°) | 11.8 (2.7) | 11.7 (2.8) | 14.4 (3.5) | 17.4 (4.6) | 2.57 (3.15) | 5.62 (5.07) | 0.47 (0.178) | 0.14 (0.707) |

| Mean pelvis rotation(°) | -1.9 (1.7) | 2.0 (1.7) | -1.5 (2.1) | 0.9 (1.8) | 0.38 (1.34) | 1.09 (1.03) | 0.77 (0.014) * | 0.88 (0.002) * |

| Hip flexion ROM (°) | 46.9 (3.6) | 45.8 (6.7) | 43.9 (3.4) | 41.5 (5.7) | 2.95 (2.51) | 4.37 (3.27) | 0.79 (0.010) * | 0.84 (0.004) * |

| Hip flexion IC (°) | 26.0 (3.5) | 25.1 (3.9) | 29.9 (3.6) | 27.2 (3.3) | 3.85 (1.69) | 2.13 (3.65) | 0.92 (<0.001) * | 0.42 (0.232) |

| Hip sagittal - max extension (°) | -17.9 (2.8) | -18.0 (4.8) | -13.0 (3.0) | -13.0 (3.9) | 4.88 (2.77) | 5.01 (1.49) | 0.52 (0.133) | 0.92 (0.000) * |

| Hip Abduction ROM (°) | 15.7 (3.0) | 16.5 (3.5) | 21.2 (5.5) | 23.7 (4.2) | 5.54 (6.86) | 7.23 (4.74) | -0.02 (0.973) | 0.25 (0.492) |

| Hip Abduction IC (°) | 2.3 (3.2) | 1.2 (2.2) | -7.0 (2.8) | -7.9 (2.2) | 9.31 (2.73) | 9.07 (2.49) | 0.38 (0.279) | 0.12 (0.759) |

| Hip rotation ROM (°) | 11.7 (2.3) | 11.4 (2.3) | 15.2 (4.1) | 16.2 (3.5) | 3.45 (4.94) | 4.78 (3.90) | -0.24 (0.514) | 0.43 (0.218) |

| Hip rotation IC (°) | -4.8 (3.5) | -5.5 (5.4) | -1.3 (4.7) | -6.9 (5.0) | 3.47 (3.72) | 1.40 (3.50) | 0.50 (0.143) | 0.60 (0.073) |

| Mean hip rotation – stand phase (°) | -0.1 (3.3) | -3.1 (4.6) | 0.5 (2.8) | -4.7 (3.9) | 0.59 (2.19) | 1.55 (1.97) | 0.73 (0.021) * | 0.83 (0.006) * |

| Knee flexion ROM (°) | 60.3 (4.4) | 61.2 (4.2) | 65.2 (4.2) | 65.5 (3.7) | 4.93 (4.43) | 4.37 (3.43) | 0.71 (0.028) * | 0.43 (0.218) |

| Knee flexion IC (°) | 11.2 (5.1) | 11.3 (5.7) | 6.1 (4.3) | 6.3 (4.9) | 5.06 (2.67) | 4.94 (3.59) | 0.81 (0.008) * | 0.81 (0.008) * |

| Maximal Knee extension (°) | 4.2 (3.6) | 2.9 (2.4) | 4.6 (3.7) | 4.6 (4.0) | 0.38 (3.12) | 1.67 (3.16) | 0.53 (0.123) | 0.61 (0.066) |

| Maximal knee flexion (°) | 63.4 (2.0) | 63.4 (3.9) | 68.0 (4.2) | 67.8 (4.3) | 4.66 (3.33) | 4.46 (2.42) | 0.53 (0.123) | 0.66 (0.044) * |

| Ankle flexion ROM (°) | 29.3 (3.0) | 28.9 (5.2) | 30.9 (3.4) | 33.1 (4.4) | 1.59 (3.91) | 4.16 (7.65) | 0.22 (0.537) | -0.37 (0.296) |

| Ankle flexion IC (°) | -1.5 (3.7) | -3.0 (2.5) | -9.0 (2.6) | -6.3 (2.5) | 7.46 (1.65) | 3.25 (1.76) | 0.92 (<0.001) * | 0.81 (0.008) * |

| Maximum stance dorsiflexion (°) | 14.8 (2.7) | 13.8 (4.4) | 6.8 (3.5) | 7.4 (2.9) | 7.97 (3.11) | 6.40 (3.16) | 0.61 (0.066) | 0.61 (0.066) |

| Maximum swing dorsiflexion (°) | 16.8 (2.4) | 16.9 (3.8) | 12.2 (2.4) | 13.4 (2.0) | 4.62 (1.87) | 3.50 (2.86) | 0.72 (0.024) * | 0.67 (0.039) * |

| Maximum plantar flexion (°) | -12.3 (4.0) | -11.9 (6.3) | -18.7 (3.4) | -19.6 (4.8) | 6.41 (4.08) | 7.70 (7.45) | 0.19 (0.608) | -0.02 (0.973) |

| Foot progression angle (°) | 9.4 (3.7) | 10.6 (5.3) | 9.9 (4.8) | 7.5 (5.8) | 0.4 (4.0) | 3.1 (3.2) | 0.59 (0.08) | 0.75 (0.02) * |

| Angle lift off (°) | 60.7 (5.2) | 58.4 (4.2) | 58.6 (6.8) | 57.8 (7.8) | 2.2 (5.8) | 0.6 (8.0) | 0.62 (0.06) | 0.13 (0.73) |

| Angle Landing (°) | 13.7 (2.5) | 14.4 (2.6) | 8.6 (3.3) | 8.4 (4.6) | 5.2 (2.3) | 6.0 (4.8) | 0.65 (0.05) * | 0.02 (0.97) |

| Parameter | WF | RW | Difference | Spearman correlation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| right | left | right | left | right | left | Right | left | |

| Mean (std) |

Mean (std) |

Mean (std) |

Mean (std) |

Mean (std) |

Mean (std) |

Corr (p-value) | Corr (p-value) | |

| Stride length (m) | 1.31 (0.12) | 1.31 (0.13) | 1.30 (0.12) | 1.30 (0.12) | -0.01 (0.04) | -0.01 (0.04) | 0.94 (<0.001) * | 0.94 (<0.001) * |

| Step width (m) | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.10 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.02) | -0.00 (0.01) | -0.01 (0.02) | 0.78 (0.01) * | 0.65 (0.05) * |

| Step length (m) | 0.65 (0.06) | 0.67 (0.07) | 0.65 (0.06) | 0.65 (0.06) | -0.01 (0.02) | -0.01 (0.02) | 0.95 (<0.001) * | 0.93 (<0.001) * |

| Gait speed (m/s) | 1.24 (0.15) | 1.25 (0.15) | 1.24 (0.14) | 1.23 (0.13) | -0.00 (0.03) | -0.01 (0.05) | 0.99 (<0.001) * | 0.92 (<0.001) * |

| Pelvis tilt mean (°) | -1.1 (7.2) | -1.0 (7.0) | -2.0 (7.4) | -2.1 (7.3) | 0.9 (0.8) | 1.1 (0.9) | 0.96 (<0.001) * | 0.96 (<0.001) * |

| Pelvis obliquity mean (°) | -1.5 (2.0) | 1.4 (2.0) | -1.5 (2.0) | 1.5 (2.0) | 0.0 (0.1) | 0.0 (0.2) | 1.00 (<0.001) * | 0.99 (<0.001) * |

| Pelvis obliquity ROM (°) | 8.3 (2.8) | 8.3 (2.9) | 8.3 (2.6) | 8.3 (2.6) | 0.0 (0.6) | 0.0 (0.7) | 0.95 (<0.001) * | 0.94 (<0.001) * |

| Pelvis obliquity IC (°) | -3.1 (3.0) | -0.2 (2.7) | -3.2 (3.0) | -0.4 (2.6) | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.3) | 0.99 (<0.001) * | 0.99 (<0.001) * |

| Pelvis rotation ROM (°) | 11.3 (3.9) | 11.4 (3.7) | 11.0 (3.8) | 10.8 (4.0) | 0.2 (1.6) | 0.6 (1.5) | 0.87 (0.003)* | 0.87 (0.003) * |

| Mean pelvis rotation(°) | -0.5 (1.8) | 0.6 (2.0) | -0.7 (1.9) | 0.6 (1.8) | 0.1 (0.7) | 0.0 (0.7) | 0.77 (0.01) * | 0.78 (0.01) * |

| Hip flexion ROM (°) | 43.4 (4.6) | 41.2 (8.8) | 43.3 (5.0) | 41.4 (8.9) | 0.1 (1.7) | 0.1 (1.5) | 0.93 (<0.001) * | 0.94 (<0.001) * |

| Hip flexion IC (°) | 26.5 (9.2) | 26.4 (8.0) | 25.5 (8.6) | 24.9 (8.5) | 1.0 (1.1) | 1.5 (1.3) | 0.98 (<0.001) * | 0.99 (<0.001) * |

| Hip sagittal - max extension (°) | -15.0 (8.8) | -13.9 (10.6) | -16.1 (9.0) | -15.4 (10.3) | 1.0 (1.6) | 1.5 (1.3) | 0.95 (<0.001) * | 0.95 (<0.001) * |

| Hip Abduction ROM (°) | 13.7 (3.0) | 14.6 (4.0) | 14.1 (3.1) | 14.7 (3.9) | 0.4 (0.8) | 0.1 (1.0) | 0.94 (<0.001) * | 0.95 (<0.001) * |

| Hip Abduction IC (°) | -2.8 (2.0) | -0.6 (4.0) | -2.4 (2.6) | -1.0 (3.6) | 0.5 (1.0) | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.96 (<0.001) * | 0.98 (<0.001) * |

| Hip rotation ROM (°) | 11.5 (2.8) | 11.0 (3.4) | 12.7 (2.2) | 11.9 (3.4) | 1.2 (1.3) | 0.8 (0.7) | 0.85 (0.004) * | 0.92 (<0.001) * |

| Hip rotation IC (°) | -4.6 (4.9) | -7.8 (5.8) | -4.4 (4.7) | -8.0 (5.9) | 0.2 (0.8) | 0.2 (1.8) | 0.99 (<0.001) * | 0.95 (<0.001) * |

| Mean hip rotation – stand phase (°) | -2.4 (3.9) | -5.2 (5.6) | -1.9 (3.7) | -5.3 (5.6) | 0.5 (0.7) | 0.1 (1.2) | 0.89 (0.001) * | 0.92 (<0.001) * |

| Knee flexion ROM (°) | 58.5 (3.2) | 58.5 (4.0) | 58.3 (3.0) | 58.9 (3.8) | 0.2 (1.2) | 0.4 (1.0) | 0.87 (0.003) * | 0.95 (<0.001) * |

| Knee flexion IC (°) | 14.2 (4.8) | 14.3 (3.4) | 12.9 (3.9) | 12.6 (3.5) | 1.3 (1.5) | 1.7 (0.7) | 0.99 (<0.001) * | 0.94 (<0.001) * |

| Maximal Knee extension (°) | 8.7 (2.8) | 8.7 (3.8) | 8.6 (2.7) | 7.8 (3.6) | 0.1 (0.6) | 0.9 (1.0) | 0.96 (<0.001) * | 0.92 (<0.001) * |

| Maximal knee flexion (°) | 65.2 (2.6) | 65.3 (3.4) | 64.5 (2.6) | 64.8 (3.2) | 0.6 (0.9) | 0.5 (1.2) | 0.93 (<0.001) * | 0.90 (<0.001) * |

| Ankle flexion ROM (°) | 28.7 (4.0) | 25.9 (4.4) | 28.7 (4.0) | 25.5 (4.1) | 0.0 (1.1) | 0.3 (1.3) | 0.96 (<0.001) * | 0.96 (<0.001) * |

| Ankle flexion IC (°) | 1.9 (2.6) | 4.4 (1.8) | 2.4 (2.6) | 4.9 (1.9) | 0.5 (0.5) | 0.5 (0.4) | 0.90 (<0.001) * | 0.99 (<0.001) * |

| Maximum stance dorsiflexion (°) | 15.4 (3.0) | 16.9 (3.7) | 15.3 (3.1) | 16.3 (3.6) | 0.1 (0.4) | 0.6 (1.0) | 0.89 (0.001) * | 0.93 (<0.001) * |

| Maximum swing dorsiflexion (°) | 16.6 (3.9) | 18.4 (3.5) | 16.6 (3.4) | 18.0 (3.7) | 0.0 (0.9) | 0.4 (0.9) | 0.96 (<0.001) * | 0.95 (<0.001) * |

| Maximum plantar flexion (°) | -11.8 (5.1) | -7.4 (6.0) | -12.0 (5.1) | -7.4 (5.5) | 0.2 (1.3) | 0.0 (2.0) | 1.00 (<0.001) * | 0.93 (<0.001) * |

| Foot progression angle (°) | 10.2 (3.1) | 10.0 (5.3) | 9.4 (3.7) | 10.6 (5.3) | 0.80 (1.8) | 0.6 (1.4) | 0.88 (0.002) * | 0.96 (<0.001) * |

| Angle lift off (°) | 61.2 (5.3) | 60.7 (5.3) | 60.7 (5.2) | 58.4 (4.2) | 0.48 (2.8) | 2.27 (3.5) | 0.77 (0.01) * | 0.67 (0.04) * |

| Angle Landing (°) | 11.9 (3.8) | 12.4 (2.3) | 13.7 (2.5) | 14.4 (2.6) | 1.9 (2.5) | 2.0 (1.7) | 0.81 (0.01) * | 0.54 (0.11) |

| Parameter | Marker-based | Markerless | Difference | Spearman correlation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| right | left | right | left | right | left | Right | left | |

| Mean (std) |

Mean (std) |

Mean (std) |

Mean (std) |

Mean (std) |

Mean (std) |

Corr (p-value) | Corr (p-value) | |

| Stride length (m) | 1.30 (0.12) | 1.30 (0.12) | 1.30 (0.12) | 1.28 (0.12) | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.98 (<0.001) * | 0.89 (0.001) * |

| Step width (m) | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.12 (0.02) | 0.11 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.83 (0.006) * | 0.85 (0.004) * |

| Step length (m) | 0.65 (0.06) | 0.65 (0.06) | 0.64 (0.06) | 0.63 (0.07) | -0.00 (0.01) | -0.02 (0.05) | 0.96 (<0.001) * | 0.68 (0.04) * |

| Gait speed (m/s) | 1.24 (0.14) | 1.23 (0.13) | 1.23 (0.14) | 1.21 (0.13) | -0.01 (0.02) | -0.02 (0.04) | 0.99 (<0.001) * | 0.92 (<0.001) * |

| Pelvis tilt mean (°) | -2.0 (7.4) | -2.1 (7.3) | -0.8 (3.4) | -0.9 (3.3) | 1.14 (7.76) | 1.16 (7.65) | 0.24 (0.514) | 0.14 (0.707) |

| Pelvis obliquity mean (°) | -1.5 (2.0) | 1.5 (2.0) | -0.0 (0.9) | 0.3 (0.6) | 1.48 (1.76) | 1.22 (1.99) | 0.52 (0.133) | 0.37 (0.296) |

| Pelvis obliquity ROM (°) | 8.3 (2.6) | 8.3 (2.6) | 17.4 (4.1) | 18.3 (3.6) | 10.0 (3.5) | 9.99 (3.53) | 0.60 (0.073) | 0.47 (0.178) |

| Pelvis obliquity IC (°) | -3.2 (3.0) | -0.4 (2.6) | -7.4 (2.7) | -7.6 (2.2) | 4.17 (3.19) | 7.20 (2.07) | 0.19 (0.608) | 0.64 (0.054) |

| Pelvis rotation ROM (°) | 11.0 (3.8) | 10.8 (4.0) | 14.4 (3.5) | 17.4 (4.6) | 3.33 (6.24) | 6.55 (5.52) | -0.47 (0.178) | 0.21 (0.560) |

| Mean pelvis rotation(°) | -0.7 (1.9) | 0.6 (1.8) | -1.5 (2.1) | 0.9 (1.8) | 0.80 (2.76) | 0.33 (2.19) | 0.07 (0.865) | 0.26 (0.470) |

| Hip flexion ROM (°) | 43.3 (5.0) | 41.4 (8.9) | 43.9 (3.4) | 41.5 (5.7) | 0.63 (4.80) | 0.11 (6.73) | 0.26 (0.470) | 0.66 (0.044) * |

| Hip flexion IC (°) | 25.5 (8.6) | 24.9 (8.5) | 29.9 (3.6) | 27.2 (3.3) | 4.40 (7.90) | 2.33 (7.59) | 0.42 (0.232) | 0.58 (0.088) |

| Hip sagittal - max extension (°) | -16.1 (9.0) | -15.4 (10.3) | -13.0 (3.0) | -13.0 (3.9) | 3.03 (8.25) | 2.40 (9.37) | 0.28 (0.427) | 0.45 (0.191) |

| Hip Abduction ROM (°) | 14.1 (3.1) | 14.7 (3.9) | 21.2 (5.5) | 23.7 (4.2) | 7.19 (3.60) | 9.01 (4.15) | 0.78 (0.012) * | 0.56 (0.096) |

| Hip Abduction IC (°) | -2.4 (2.6) | -1.0 (3.6) | -7.0 (2.8) | -7.9 (2.2) | 4.66 (3.12) | 6.93 (2.96) | 0.28 (0.427) | 0.50 (0.143) |

| Hip rotation ROM (°) | 12.7 (2.2) | 11.9 (3.4) | 15.2 (4.1) | 16.2 (3.5) | 2.50 (5.26) | 4.31 (4.89) | -0.30 (0.407) | 0.10 (0.785) |

| Hip rotation IC (°) | -4.4 (4.7) | -8.0 (5.9) | -1.3 (4.7) | -6.9 (5.0) | 3.07 (3.43) | 1.06 (5.16) | 0.66 (0.044) * | 0.48 (0.166) |

| Mean hip rotation – stand phase (°) | -1.9 (3.7) | -5.3 (5.6) | 0.5 (2.8) | -4.7 (3.9) | 2.45 (1.98) | 0.62 (4.58) | 0.90 (0.001) * | 0.59 (0.080) |

| Knee flexion ROM (°) | 58.3 (3.0) | 58.9 (3.8) | 65.2 (4.2) | 65.5 (3.7) | 6.91 (4.59) | 6.63 (5.03) | 0.03 (0.946) | 0.30 (0.407) |

| Knee flexion IC (°) | 12.9 (3.9) | 12.6 (3.5) | 6.1 (4.3) | 6.3 (4.9) | 6.75 (3.27) | 6.26 (3.12) | 0.78 (0.012) * | 0.61 (0.066) |

| Maximal Knee extension (°) | 8.6 (2.7) | 7.8 (3.6) | 4.6 (3.7) | 4.6 (4.0) | 4.00 (2.86) | 3.21 (3.16) | 0.73 (0.021) * | 0.36 (0.313) |

| Maximal knee flexion (°) | 64.5 (2.6) | 64.8 (3.2) | 68.0 (4.2) | 67.8 (4.3) | 3.51 (4.67) | 3.01 (5.29) | 0.04 (0.919) | -0.02 (0.973) |

| Ankle flexion ROM (°) | 28.7 (4.0) | 25.5 (4.1) | 30.9 (3.4) | 33.1 (4.4) | 2.26 (3.56) | 7.55 (5.77) | 0.53 (0.123) | 0.02 (0.973) |

| Ankle flexion IC (°) | 2.4 (2.6) | 4.9 (1.9) | -9.0 (2.6) | -6.3 (2.5) | 11.39 (2.29) | 11.22 (3.71) | 0.43 (0.218) | -0.35 (0.331) |

| Maximum stance dorsiflexion (°) | 15.3 (3.1) | 16.3 (3.6) | 6.8 (3.5) | 7.4 (2.9) | 8.51 (4.00) | 8.88 (3.09) | 0.19 (0.608) | 0.31 (0.387) |

| Maximum swing dorsiflexion (°) | 16.6 (3.4) | 18.0 (3.7) | 12.2 (2.4) | 13.4 (2.0) | 4.36 (3.46) | 4.63 (3.33) | 0.33 (0.349) | 0.52 (0.133) |

| Maximum plantar flexion (°) | -12.0 (5.1) | -7.4 (5.5) | -18.7 (3.4) | -19.6 (4.8) | 6.67 (5.20) | 12.23 (6.68) | 0.04 (0.919) | -0.13 (0.733) |

| Foot progression angle (°) | 9.4 (3.7) | 10.6 (5.3) | 9.9 (4.8) | 7.5 (5.8) | 0.4 (4.0) | 3.1 (3.2) | 0.59 (0.08) | 0.75 (0.02) * |

| Angle lift off (°) | 60.7 (5.2) | 58.4 (4.2) | 58.6 (6.8) | 57.8 (7.8) | 2.2 (5.8) | 0.6 (8.0) | 0.62 (0.06) | 0.13 (0.73) |

| Angle Landing (°) | 13.7 (2.5) | 14.4 (2.6) | 8.6 (3.3) | 8.4 (4.6) | 5.2 (2.3) | 6.0 (4.8) | 0.65 (0.05) * | 0.02 (0.97) |

References

- Podsiadlo, D.; Richardson, S. The Timed “Up & Go”: A Test of Basic Functional Mobility for Frail Elderly Persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1991, 39, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathias, S.; Nayak, U.S.; Isaacs, B. Balance in Elderly Patients: The “Get-up and Go” Test. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1986, 67, 387–389. [Google Scholar]

- Graff, K.; Szczerbik, E.; Kalinowska, M.; Kaczmarczyk, K.; Stępień, A.; Syczewska, M. Using the TUG Test for the Functional Assessment of Patients with Selected Disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 4602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komodikis, G.; Gannamani, V.; Neppala, S.; Li, M.; Merli, G.J.; Harrop, J.S. Usefulness of Timed Up and Go (TUG) Test for Prediction of Adverse Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Thoracolumbar Spine Surgery. Neurosurgery 2020, 86, E273–E280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque-Casado, A.; Novo-Ponte, S.; Sánchez-Molina, J.A.; Sevilla-Sánchez, M.; Santos-García, D.; Fernández-del-Olmo, M. Test-Retest Reliability of the Timed Up and Go Test in Subjects with Parkinson’s Disease: Implications for Longitudinal Assessments. J. Park. Dis. 2021, 11, 2047–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kear, B.M.; Guck, T.P.; McGaha, A.L. Timed Up and Go (TUG) Test: Normative Reference Values for Ages 20 to 59 Years and Relationships With Physical and Mental Health Risk Factors. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2017, 8, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Bastidas, P.; Gómez, B.; Aqueveque, P.; Luarte-Martínez, S.; Cano-de-la-Cuerda, R. Instrumented Timed Up and Go Test (iTUG)—More Than Assessing Time to Predict Falls: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponciano, V.; Pires, I.M.; Ribeiro, F.R.; Spinsante, S. Sensors Are Capable to Help in the Measurement of the Results of the Timed-Up and Go Test? A Systematic Review. J. Med. Syst. 2020, 44, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Lach, J.; Lo, B.; Yang, G.-Z. Toward Pervasive Gait Analysis With Wearable Sensors: A Systematic Review. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2016, 20, 1521–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnyaud, C.; Pradon, D.; Vuillerme, N.; Bensmail, D.; Roche, N. Spatiotemporal and Kinematic Parameters Relating to Oriented Gait and Turn Performance in Patients with Chronic Stroke. PloS One 2015, 10, e0129821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnyaud, C.; Pradon, D.; Vaugier, I.; Vuillerme, N.; Bensmail, D.; Roche, N. Timed Up and Go Test: Comparison of Kinematics between Patients with Chronic Stroke and Healthy Subjects. Gait Posture 2016, 49, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollands, K.L.; Hollands, M.A.; Zietz, D.; Wing, A.M.; Wright, C.; van Vliet, P. Kinematics of Turning 180 Degrees during the Timed up and Go in Stroke Survivors with and without Falls History. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2010, 24, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Chen, J.; Hu, C.; Ma, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wan, W.; Huang, Y.; Jia, F.; Gong, C.; Wan, S.; et al. Automatic Timed Up-and-Go Sub-Task Segmentation for Parkinson’s Disease Patients Using Video-Based Activity Classification. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. Publ. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2018, 26, 2189–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salarian, A.; Horak, F.B.; Zampieri, C.; Carlson-Kuhta, P.; Nutt, J.G.; Aminian, K. iTUG, a Sensitive and Reliable Measure of Mobility. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. Publ. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2010, 18, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spina, S.; Facciorusso, S.; D’Ascanio, M.C.; Morone, G.; Baricich, A.; Fiore, P.; Santamato, A. Sensor Based Assessment of Turning during Instrumented Timed Up and Go Test for Quantifying Mobility in Chronic Stroke Patients. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2023, 59, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Uem, J.M.T.; Walgaard, S.; Ainsworth, E.; Hasmann, S.E.; Heger, T.; Nussbaum, S.; Hobert, M.A.; Micó-Amigo, E.M.; Van Lummel, R.C.; Berg, D.; et al. Quantitative Timed-Up-and-Go Parameters in Relation to Cognitive Parameters and Health-Related Quality of Life in Mild-to-Moderate Parkinson’s Disease. PloS One 2016, 11, e0151997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, J.C.; Bell, C.; Campbell, S.; Davis, J. The Timed Get-up-and-Go Test Revisited: Measurement of the Component Tasks. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2000, 37, 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, L.; Needham, L.; McGuigan, P.; Bilzon, J. Applications and Limitations of Current Markerless Motion Capture Methods for Clinical Gait Biomechanics. PeerJ 2022, 10, e12995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlrich, S.D.; Falisse, A.; Kidziński, Ł.; Muccini, J.; Ko, M.; Chaudhari, A.S.; Hicks, J.L.; Delp, S.L. OpenCap: Human Movement Dynamics from Smartphone Videos. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2023, 19, e1011462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsak, B.; Eichmann, A.; Lauer, K.; Prock, K.; Krondorfer, P.; Siragy, T.; Dumphart, B. Concurrent Validity of Smartphone-Based Markerless Motion Capturing to Quantify Lower-Limb Joint Kinematics in Healthy and Pathological Gait. J. Biomech. 2023, 159, 111801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, Y.; Collings, T.; Hall, M.; Bourne, M.; Diamond, L. Assessing Lower-Limb Kinematics via OpenCap during Dynamic Tasks Relevant to Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury: A Validity Study. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2023, 26, S105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodacki, A.L.F.; Buckley, J.G.; Passos de Oliveira, A.C.; Marçal da Silva, R.; Bertoli Nascimento, V. An Experimental Approach to Induce Trips in Lower-Limb Amputees. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenCap - Musculoskeletal Forces from Smartphone Videos. Available online: https://www.opencap.ai/ (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Lai, A.K.M.; Arnold, A.S.; Wakeling, J.M. Why Are Antagonist Muscles Co-Activated in My Simulation? A Musculoskeletal Model for Analysing Human Locomotor Tasks. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 45, 2762–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, A.; Dembia, C.L.; DeMers, M.S.; Delp, D.D.; Hicks, J.L.; Delp, S.L. Full-Body Musculoskeletal Model for Muscle-Driven Simulation of Human Gait. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2016, 63, 2068–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoboda, B.; Kranzl, A. A Study of the Reproducibility of the Marker Application of the Cleveland Clinic Marker Set Including the Plug-In Gait Upper Body Model in Clinical Gait Analysis. Gait Posture 2012, 36, S62–S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delp, S.L.; Anderson, F.C.; Arnold, A.S.; Loan, P.; Habib, A.; John, C.T.; Guendelman, E.; Thelen, D.G. OpenSim: Open-Source Software to Create and Analyze Dynamic Simulations of Movement. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2007, 54, 1940–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataky, T.C. One-Dimensional Statistical Parametric Mapping in Python. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin. 2012, 15, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapczyński, M.; Werner, P.; Handrich, S.; Al-Hamadi, A. A Baseline for Cross-Database 3D Human Pose Estimation. Sensors 2021, 21, 3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, Y.; Uno, K.; Matsui, Y. Types of Anomalies in Two-Dimensional Video-Based Gait Analysis in Uncontrolled Environments. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2023, 19, e1009989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pelvic tilt | Pelvic obliquity | Pelvic rotation | Hip flexion | Hip adduction | Hip rotation | Knee flexion | Ankle flexion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| MEAN RMSE (WF/RW) | GRAND MEAN | |||||||||

| Markerless (°) | 1.9(1.3) | 5.8 (3.2) | 1.9 (2.0) | 4.6(2.9) | 6.6 (3.9) | 3.0(2.4) | 3.6 (2.5) | 8.5 (4.6) | 4.5(2.9) | |

| Marker-based (°) | 1.1(0.9) | 0.31(0.2) | 0.8(0.6) | 1.7(1.4) | 0.6(0.5) | 1.0 (0.7) | 1.3 (1.2) | 0.8 (0.8) | 1.0 (0.8) | |

| Difference (°) | 0.8(0.4) | 5.4(3.0) | 1.1 (1.4) | 2.9 (1.5) | 6.0 (3.4) | 2.0 (1.6) | 2.3 (1.3) | 7.7 (3.8) | 3.5 (2.1) | |

| MEAN RMSE (markerless/ marker-based) | ||||||||||

| RW (°) | 6.9 (3.6) | 5.3 (3.2) | 3.8 (5.3) | 8.0 (5.1) | 6.1 (4.2) | 4.7 (4.8) | 5.8 (4.5) | 11.9(6.4) | 6.6 (4.6) | |

| WF (°) | 6.6 (3.6) | 2.8 (2.1) | 2.9 (2.0) | 8.9 (5.6) | 3.5 (2.5) | 4.0 (3.0) | 5.6 (4.2) | 4.7 (3.4) | 4.9 (3.3) | |

| Difference (°) | 0.3(0.0) | 2.5 (1.1) | 0.9 (3.3) | -0.9(-0.5) | 2.6(1.7) | 0.7 (1.8) | 0.2 (0.3) | 7.2 (3.0) | 1.7 (1.3) | |

|

MAX RMSE (markerless/ marker-based) |

||||||||||

| WR (°) | 10.9 (3.4) |

10.8 (2.3) | 10.1 (12.0) | 14.7 (5.5) | 13.1 (5.2) | 12.2 (8.0) | 13.3 (5.2) | 22.9 (7.2) | 13.5 (6.1) | |

| WF (°) | 9.6 (3.4) | 6.0 (2.2) | 6.1 (1.8) | 14.2 (5.2) | 7.6 (2.4) | 8.5 (2.8) | 10.8 (5.2) | 10.9 (4.0) | 9.2 (3.4) | |

| Difference (°) | 1.3 (0.0) | 4.8 (0.1) | 4.0 (11.2) | 0.5 (0.3) | 5.5 (2.8) | 3.7 (5.2) | 2.8 (0.0) | 12.0(3.2) | 4.3 (2.7) | |

| Parameter | Marker-based | Markerless | Difference | Spearman correlation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right | Left | Right | Left | Right | Left | Right | Left | |

| Mean (STD) |

Mean (STD) |

Mean (STD) |

Mean (STD) |

Mean (STD) |

Mean (STD) |

Corr (P-value) |

Corr (P-value) |

|

| Stride length (m) | 1.31 (0.12) | 1.31 (0.13) | 1.31 (0.12) | 1.31 (0.13) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | 1.00 (<0.001)* | 1.00 (<0.001)* |

| Step width (m) | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.10 (0.02) | 0.10 (0.02) | 0.11 (0.03) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.94 (<0.001)* | 0.95 (<0.001)* |

| Step length (m) | 0.65 (0.06) | 0.67 (0.07) | 0.65 (0.06) | 0.66 (0.07) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.98 (<0.001)* | 0.99 (<0.001)* |

| Gait speed (m/s) | 1.24 (0.15) | 1.25 (0.15) | 1.23 (0.15) | 1.24 (0.15) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | 1.00 (<0.001)* | 0.99 (<0.001)* |

| Pelvis tilt mean (°) | -1.1 (7.2) | -1.0 (7.0) | -1.0 (2.4) | -1.0 (2.3) | 0.1 (7.2) | 0.0 (7.1) | 0.28 (0.43) | 0.20 (0.58) |

| Pelvis obliquity mean (°) | -1.5 (2.0) | 1.4 (2.0) | 0.7 (0.7) | -0.4 (0.6) | 2.1 (2.0) | 1.9 (1.9) | 0.16 (0.66) | 0.39 (0.26) |

| Pelvis obliquity ROM (°) | 8.3 (2.8) | 8.3 (2.9) | 9.6 (2.5) | 10.1 (2.4) | 1.3 (4.7) | 1.7 (4.7) | -0.42 (0.23) | -0.43 (0.22) |

| Pelvis obliquity IC (°) | -3.1 (3.0) | -0.2 (2.7) | 1.4 (2.9) | 1.1 (2.2) | 4.4 (3.4) | 1.3 (2.7) | 0.15 (0.68) | 0.31 (0.39) |

| Pelvis rotation ROM (°) | 11.3 (3.9) | 11.4 (3.7) | 11.8 (2.7) | 11.7 (2.8) | 0.5 (4.3) | 0.3 (4.4) | 0.18 (0.63) | 0.32 (0.37) |

| Mean pelvis rotation(°) | -0.5 (1.8) | 0.6 (2.0) | -1.9 (1.7) | 2.0 (1.7) | 1.3 (2.0) | 1.4 (2.0) | 0.24 (0.51) | 0.22 (0.54) |

| Hip flexion ROM (°) | 43.4 (4.6) | 41.2 (8.8) | 46.9 (3.6) | 45.8 (6.7) | 3.5 (2.9) | 4.6 (4.9) | 0.64 (0.05)* | 0.65 (0.05)* |

| Hip flexion IC (°) | 26.5 (9.2) | 26.4 (8.0) | 26.0 (3.5) | 25.1 (3.9) | 0.4 (8.9) | 1.3 (9.4) | 0.22 (0.54) | -0.21 (0.56) |

| Hip sagittal - max extension (°) | -15.0 (8.8) | -13.9 (10.6) | -17.9 (2.8) | -18.0 (4.8) | 2.9 (9.4) | 4.1 (10.8) | -0.16 (0.66) | 0.03 (0.95) |

| Hip Abduction ROM (°) | 13.7 (3.0) | 14.6 (4.0) | 15.7 (3.0) | 16.5 (3.5) | 2.1 (4.2) | 1.9 (5.2) | 0.02 (0.97) | -0.04 (0.92) |

| Hip Abduction IC (°) | -2.8 (2.0) | -0.6 (4.0) | 2.3 (3.2) | 1.2 (2.2) | 5.1 (3.6) | 1.8 (3.8) | -0.12 (0.76) | 0.25 (0.49) |

| Hip rotation ROM (°) | 11.5 (2.8) | 11.0 (3.4) | 11.7 (2.3) | 11.4 (2.3) | 0.2 (3.2) | 0.4 (3.2) | 0.27 (0.45) | 0.37 (0.30) |

| Hip rotation IC (°) | -4.6 (4.9) | -7.8 (5.8) | -4.8 (3.5) | -5.5 (5.4) | 0.2 (2.7) | 2.3 (4.3) | 0.87 (0.00)* | 0.75 (0.02)* |

| Mean hip rotation – stand phase (°) | -2.4 (3.9) | -5.2 (5.6) | -0.1 (3.3) | -3.1 (4.6) | 2.3 (2.4) | 2.0 (4.4) | 0.67 (0.04)* | 0.54 (0.11) |

| Knee flexion ROM (°) | 58.5 (3.2) | 58.5 (4.0) | 60.3 (4.4) | 61.2 (4.2) | 1.8 (2.8) | 2.7 (3.7) | 0.55 (0.10) | 0.73 (0.02)* |

| Knee flexion IC (°) | 14.2 (4.8) | 14.3 (3.4) | 11.2 (5.1) | 11.3 (5.7) | 3.0 (3.3) | 3.0 (5.3) | 0.79 (0.01)* | 0.37 (0.30) |

| Maximal Knee extension (°) | 8.7 (2.8) | 8.7 (3.8) | 4.2 (3.6) | 2.9 (2.4) | 4.5 (3.3) | 5.8 (4.3) | 0.55 (0.10) | -0.10 (0.79) |

| Maximal knee flexion (°) | 65.2 (2.6) | 65.3 (3.4) | 63.4 (2.0) | 63.4 (3.9) | 1.8 (2.0) | 1.9 (4.3) | 0.33 (0.35) | 0.19 (0.61) |

| Ankle flexion ROM (°) | 28.7 (4.0) | 25.9 (4.4) | 29.3 (3.0) | 28.9 (5.2) | 0.6 (3.9) | 3.1 (4.7) | 0.37 (0.30) | 0.39 (0.26) |

| Ankle flexion IC (°) | 1.9 (2.6) | 4.4 (1.8) | -1.5 (3.7) | -3.0 (2.5) | 3.4 (3.3) | 7.5 (3.0) | 0.43 (0.22) | -0.10 (0.79) |

| Maximum stance dorsiflexion (°) | 15.4 (3.0) | 16.9 (3.7) | 14.8 (2.7) | 13.8 (4.4) | 0.6 (3.7) | 3.1 (3.4) | 0.20 (0.58) | 0.49 (0.15) |

| Maximum swing dorsiflexion (°) | 16.6 (3.9) | 18.4 (3.5) | 16.8 (2.4) | 16.9 (3.8) | 0.2 (3.8) | 1.5 (3.2) | 0.33 (0.35) | 0.44 (0.20) |

| Maximum plantar flexion (°) | -11.8 (5.1) | -7.4 (6.0) | -12.3 (4.0) | -11.9 (6.3) | 0.5 (3.6) | 4.5 (3.9) | 0.62 (0.06) | 0.77 (0.01)* |

| Foot progression angle (°) | 10.2 (3.1) | 10.0 (5.3) | 5.5 (3.4) | 6.1 (6.3) | 4.8 (4.1) | 3.8 (5.6) | 0.26 (0.47) | 0.16 (0.66) |

| Angle lift off (°) | 61.2 (5.3) | 60.7 (5.3) | 59.3 (7.8) | 59.5 (6.2) | 1.9 (7.0) | 1.2 (5.1) | 0.12 (0.76) | 0.73 (0.02) * |

| Angle Landing (°) | 11.9 (3.8) | 12.4 (2.3) | 6.0 (3.4) | 4.8 (3.1) | 5.9 (3.6) | 7.6 (3.4) | 0.42 (0.23) | -0.02 (0.97) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).