1. Introduction

At the beginning of the 20th century, Dutch agriculture mainly consisted of small-scale mixed farms. The economic crisis of the 1930s and the food shortages during and after World War II were reasons for European governments to intervene extensively in the agricultural sector (Van der Heide et al., 2011). In the Netherlands, Sicco Mansholt became the first post-war minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. Vowing to prevent another famine, Mansholt devised an agricultural policy to boost productivity.

1 This formed the basis for the first Mansholt Plan of 1953, which was instrumental in shaping the European Agricultural Policy. When he was Agricultural Commissioner in Brussels, he saw that farmers' incomes lagged behind those in other sectors, therefore, in 1968, he published his second plan aiming at a rationalisation of European agriculture (Pierhagen, 1996). Post-war policy focused on ensuring a reliable and continuous food supply at fair prices for the consumers and a stable income for the farmers. Modernisation of agriculture became a key concern, with an emphasis on increasing production per farmer and temporarily suppressing farmers wages for reinvestment. Price regulation and various policy instruments were deployed to achieve those goals (De Haas, 2013). Research, extension and education encouraged farmers to produce as much as possible. Through export promotion, the government played a role in unlocking access to international markets. Significantly more acres of land were brought under cultivation (Meester, 2004). In the 1950s, efforts were made to improve the agricultural structure, particularly the land-to-labour ratio. Land consolidation and concentration of production into larger holdings were pursued to enhance land use efficiency. The 1960s marked the beginning of intensive modernisation and intensification of Dutch agriculture, with a shift towards larger, more efficient farms. In academic circles this became known as ‘footloose’ agricultural farms (Van der Heide et al, 2011). Technological advancements, which were stimulated by the agricultural policy of the Dutch government and afterwards by the agricultural policies of the European Community, played a crucial role in increasing productivity. Over the years, the number of farms decreased significantly, but the production value continued to rise. Dutch agriculture became highly productive, with the country achieving the highest livestock densities in Europe (Van der Heide et al, 2011).

The increase in agricultural production had negative impacts on the environment. Intensive farming resulted in widespread nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) pollution, and the release of harmful plant protection products (PPP) into surface and groundwaters (Van Gaalen et al., 2020; Knoben et al., 2021; Slagter et al., 2024). In the decades following World War II, agricultural policies were developed based on a consensus among a tightly knit agricultural network (known as ‘the Green Front’). However, in the 1970s, debates about the limits of growth, triggered by the report ‘Limits to Growth’ by the Club of Rome in 1972 (Meadows and the Club of Rome, 1972), led to a breakdown of this consensus. The focus on production at the expense of landscape, animal welfare, and ecology was criticised (De Haas, 2013). Environmental policies, such as the Dutch Manure and Fertiliser Act (Meststoffenwet, 1986), the European Nitrate Directive (Council of the European Communities, 1991), the Habitat Directive (Council of the European Communities, 1992), and the European Water Framework Directive (European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, 2000) were introduced to address these issues. These were mostly generic policies meant to apply to a large range of situations, and Member States implemented these directives in diverse ways. For instance, the Netherlands chose not to designate nitrate-sensitive areas but declared the Nitrates Directive applicable to its entire territory. This was done because of the significant role of nitrate leaching into groundwater and eutrophication of surface waters including coastal and transitional waters. Additionally, the characteristics of the Dutch water system made it not meaningful and justifiable to differentiate between areas. As a result, the Nitrates Directive applies to all farmers in the country. These general measures were highly effective in reducing nitrogen and phosphorus emissions in the first two decades after the implementation of the Dutch fertiliser act (Meststoffenwet, 1986) and the European Nitrates Directive (Council of the European Communities, 1991) (Fraters et al., 2020). However, despite considerable progress in reducing nutrient emissions and improving water quality, challenges remained, and regional customisation became necessary to achieve water quality objectives.

In 2013, the Dutch Minister of infrastructure and Environment stated in a letter to the regional water managers that, despite improvements in water quality, none of the Dutch Water Framework Directive (WFD) water bodies had simultaneously achieved all WFD objectives. This was largely due to challenges with respect to nutrients and plant protection products. However, the remaining challenges were considered specific and regional/local in nature (Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Milieu, 2013). Therefore, in order to take further steps to improve water quality, regional and local customisation was needed. The Dutch government therefore welcomed private-public projects, such as the Delta Plan for Agricultural Water Management, which aimed to improve water quality at a regional and local levels (Ministerie van Economische Zaken, 2013). These efforts were expected to enhance the quality of ground- and surface water without additional generic measures.

The prevention of additional generic measures was an important reason for the Dutch agricultural stakeholder organisation LTO Netherlands to start the Delta Plan for Agricultural Water Management (DAW), together with the Dutch Water Authorities (In Dutch ‘Unie van Waterschappen’). DAW was embraced in 2013 by the national Water Steering Group, which includes various ministries, the national association of municipalities (VNG), the Dutch Water Authorities (UvW) and the Interprovincial Consultation (IPO). The DAW aims, on the one hand, to help realise national and regional water tasks, but on the other hand, to also ensure an economically strong and sustainable agriculture and horticulture (DAW, 2016). Hence, the DAW establishes a connection between water objectives and agricultural goals and follows a comprehensive programmatic approach, aimed at the intrinsic motivation of agricultural entrepreneurs for water- and soil-oriented management practices and at encouraging them to provide a sustainable solution for the water challenges in the Netherlands and a stronger agricultural sector (DAW, 2016). Furthermore, DAW aims at identifying feasible, innovative measures and makes them concrete to specific areas and farms. This approach allowed for voluntary yet binding contributions from the agricultural sector to inter alia reduce nutrient emissions, partially in an attempt to prevent additional general measures. As agricultural entrepreneurs are also water and soil managers that manage most of the Dutch surface area, the government addresses and supports them in this responsibility through DAW. This is still in line with the most recent Dutch coalition programme in which the government sets the direction, and leaves room to the various actors in society for own initiative and taking advantage of opportunities (Rijksoverheid, 2024).

The purpose of this article is to shed light on ten years of experience with the Delta Plan for Agricultural Water Management, showcasing that a voluntary approach can be an effective approach to reducing environmental problems. Based on information from interviews with key stakeholders, and enriched with experiences from specific relevant projects, insight is provided into the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of DAW. The central questions of this article are: what has ten years’ experience of DAW brought us; what are the main successes and the keys to those successes; and what are the key bottlenecks and challenges for the future?

2. Material & Methods

To get a good picture of the results and the lessons learned from experiences over the past 10 years, eighteen representatives of different organisations that have contributed to projects related to the Delta Plan for DAW have been interviewed. The respondents were representatives from the relevant ministries, provinces, agricultural stakeholder organisations, various regional water authorities, and DAW program management. See

Table 1 for an overview of the organisations represented by the various respondents and their relevance to DAW. Their reflections have been enriched by additional information on the various projects that the respondents have been referring to. That information has been derived from various annual reports and DAW-related project websites.

A SWOT analysis was conducted to categorise the wealth of information that was collected during the interviews in terms of the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats. A SWOT analysis was used since this type of analysis is seen as an effective tool to diagnose problems and opportunities Information is presented in a clear and compact 2x2 matrix, whereby the strengths and weaknesses describe internal factors, and opportunities and threats relate to external factors. Interpretation of the SWOT analysis can help identify possible future actions for all stakeholders.

3. The Results of 10 Years Delta Plan for Agricultural Water Management

3.1. Results on Process and Organisation

DAW offers a platform where representatives from agricultural stakeholder organisations, regional water authorities, provinces and various ministries engage in an open and constructive dialogue on objectives and ambitions but also on challenges faced in realising them and work together to find practical solutions. The fact that such a platform is created, widely accepted, and works, is an important result in itself. At the time DAW started, it was a relatively unique initiative in Europe. This can be illustrated by the fact that in 2017, at a joint meeting of the European water directors and the European agriculture directors, they identified the lack of connection between respective authorities in the agricultural and water sectors as one of the main bottlenecks on agriculture-water governance at Member State level (van der Veeren et al., 2017). More recently, similar initiatives have started in other EU member states, such as the Agricultural Sustainability, Support and Advisory Programme in Ireland

2, or B3W in Flanders

3.

The organisation of DAW developed over the years. In the first years, DAW has focused on the organisation of the DAW itself; getting the relevant organisations together around the table with the necessary commitment. This resulted in an organisation, in which LTO Netherlands and the Cadastre

4 (in Dutch: Kadaster) facilitate the DAW process. This includes guiding and supporting DAW projects and regional processes and facilitating discussions between agricultural entrepreneurs and water managers. Since 2015, this core group (‘kern team’) is supported by a so-called ‘DAW Support Team’. This Support Team consists of regional coordinators, sectoral knowledge brokers, national advisors, regional staff, and a DAW programme manager and forms the link between the core group and the ‘people in the field’; the farmers and local water managers. Since 2019, DAW significantly intensified their efforts on raising awareness and knowledge transfer (information dissemination), in order to enhance the implementation of measures that support sustainable and lasting change (for example by means of the enhanced knowledge dissemination programme; see Textbox 1 for a short description of this programme). This also led to a shift from a regional approach to a more sector-oriented and theme-focused approach. Soil has increasingly emerged as a crucial factor to address. The team also disseminates knowledge on best practices, through publications on projects, information meetings for sectors, organising farm visits and the website

https://agrarischwaterbeheer.nl/ (DAW, 2016). For this, the team has appointed inter alia separate knowledge brokers, who are responsible to get the most relevant knowledge at the individual farm, so that farmers can make well informed decisions aimed at clean and sufficient water, healthy soils, while simultaneously keeping an eye on profitability of the business (DAW, 2024). Finally, for the provinces, regional water authorities and other stakeholders, the DAW coordinators form the link with provincial dossiers such as the Rural Development Programme, WFD, Delta Plan Freshwater (aimed at water quantity management), and Agricultural Nature and Landscape Management (DAW, 2016).

Textbox 1. The enhanced knowledge dissemination programme.

In the knowledge programme, farmers and horticulturists are supported and informed about relevant and practical knowledge in various ways. For example, through ‘knowledge brokers’ who make the connection between farmers and horticulturists on the one hand and knowledge institutes, pilot farms, practice networks and knowledge platforms on the other. Among other things, these knowledge brokers have organized organised field demos and excursions to the Farm of the Future, as well as a soil tear-off calendar (DAW, 2022). In 2022 about 24,500 farmers received this calendar, with a daily tip, quiz or mini lecture on the value of healthy soil for 2023. In 2024 this number increased to 30,000 (DAW, 2025). As part of this knowledge programme, farmers and horticulturists can also get free and independent soil advice from 110 soil advisers (each with their own expertise) in 9 regional soil teams. Also, those latter numbers increased: in 2024 there were 10 teams with a total of 153 advisors (DAW, 2025).

3.2. Developments in Number and Type of Projects

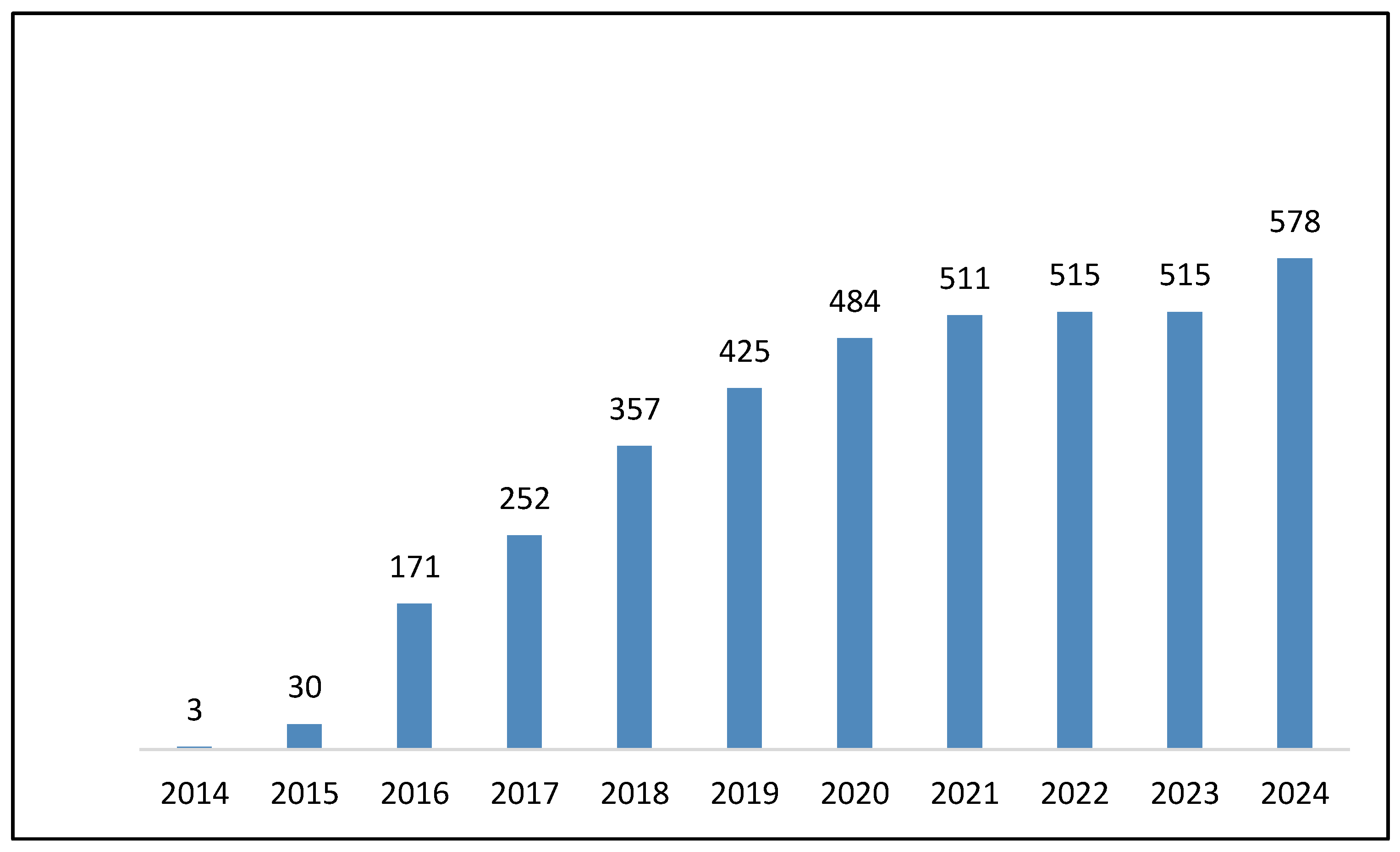

DAW started with three projects. Overall there have been almost six hundred projects (see

Figure 1). At the time of writing, more than 30% of all farmers in the Netherlands participate in one or more of these projects. Projects may vary from knowledge sharing and transfer to support during the implementation of measures.

One of the important aspects of DAW is that it has an umbrella function. It bundles various projects related to agricultural water management, irrespective of whether the project was officially initiated as a DAW project, and facilitates communication and knowledge sharing among farmers in different regions of the Netherlands. In addition, because experiences of projects only really come to life when you see, smell or feel it yourself in the field, DAW takes farmers, horticulturists, and policy advisers on joint field excursions. For this purpose, DAW has its own bus available, ‘the Water Caravan’. In 2022, the Water Caravan was driven fourteen times

5, including four times specially as a Climate Caravan to talk about salinisation, drought and flooding. The target group for each excursion varied and the reactions afterwards were always enthusiastic (DAW, 2023).

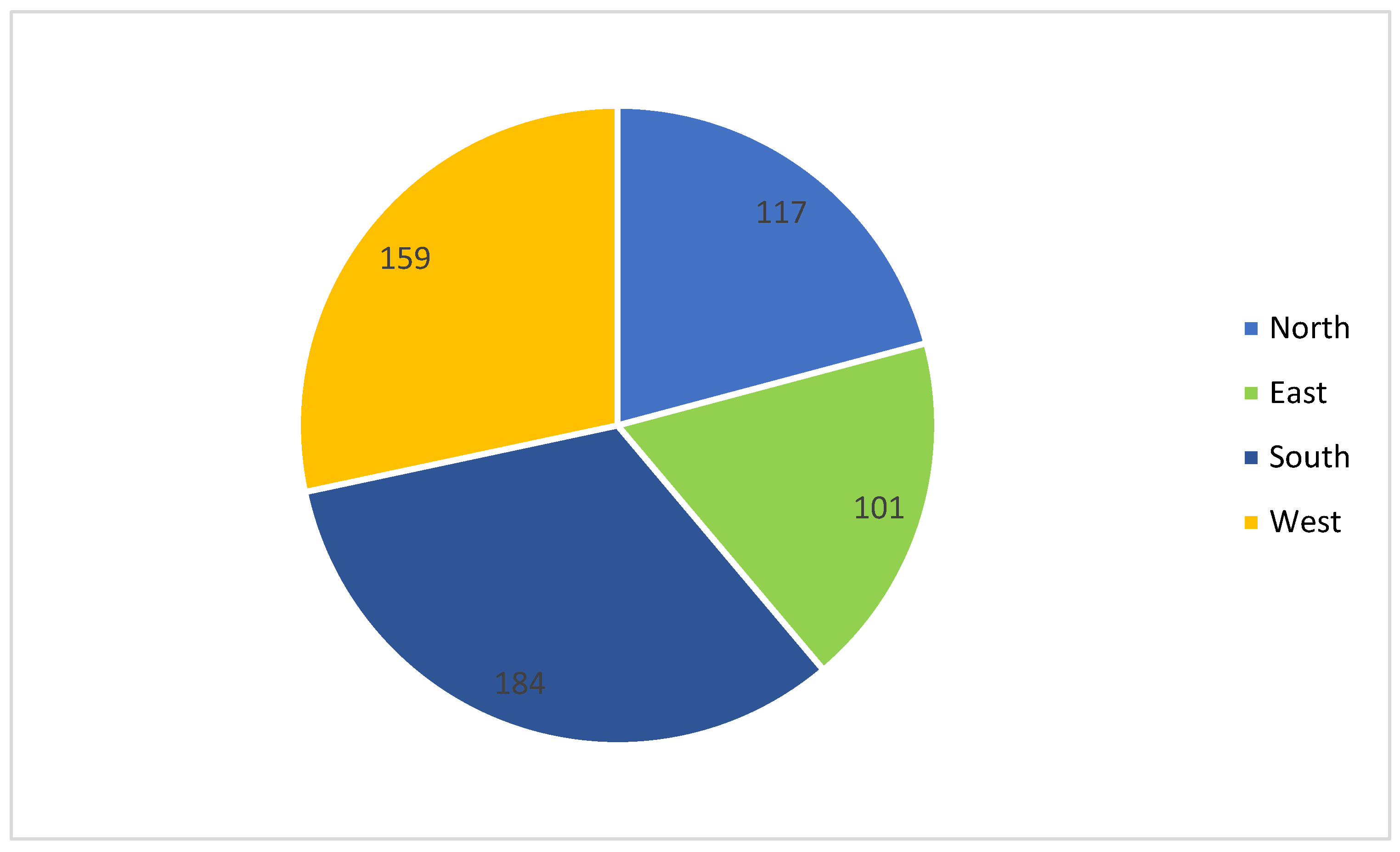

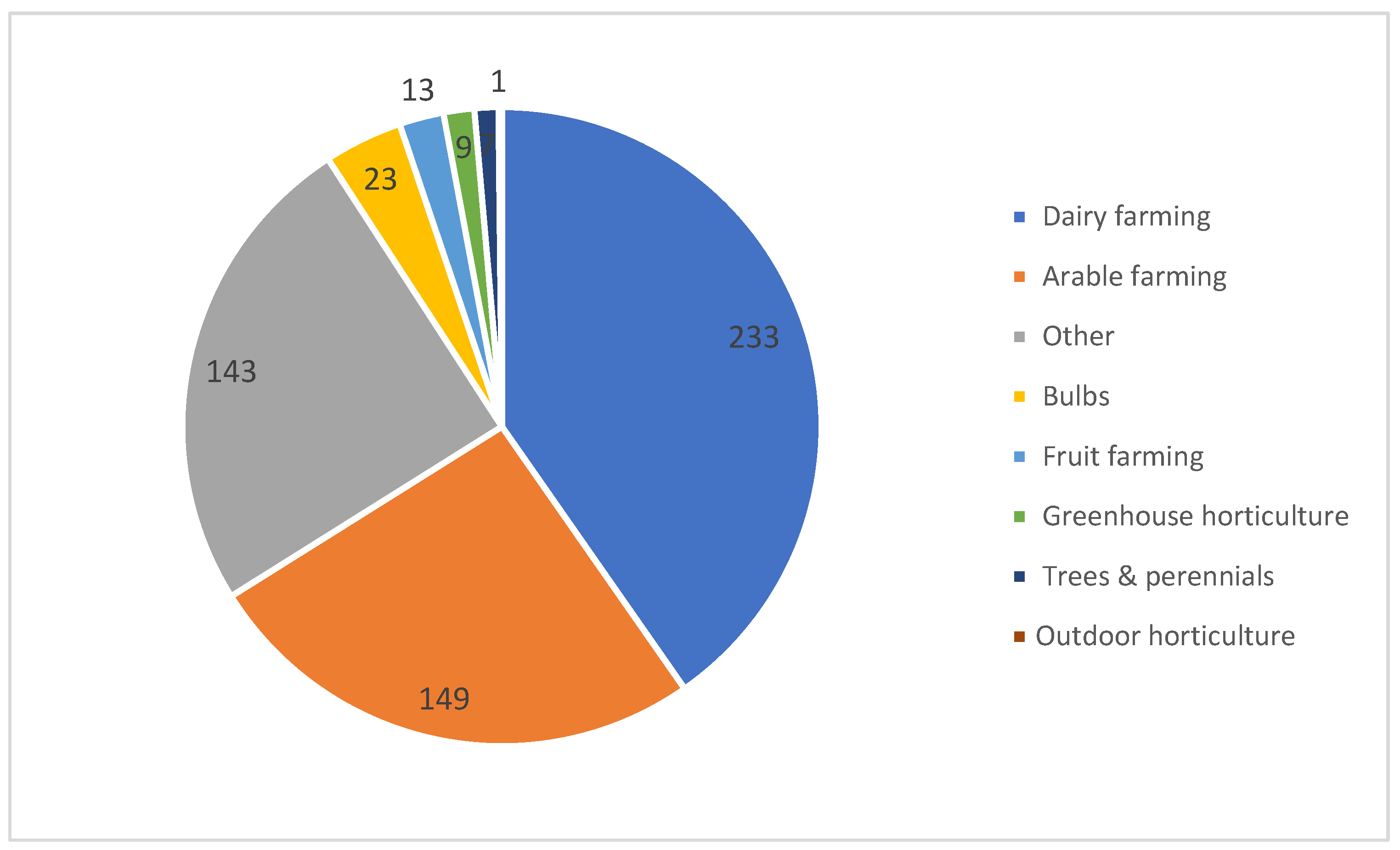

Figure 2 shows that the number of projects is distributed evenly across the Netherlands, with a relatively large number of projects in the south. Furthermore, as

Figure 3 illustrates, DAW is not (yet) relevant for all agricultural sectors. There is a strong focus on projects related to arable farming and dairy farming; the land-based agriculture. For greenhouse horticulture, separate trajectories were already in place. For example, the programme ‘Glastuinbouw Waterproof’, which aims to aims to achieve (virtually) zero emissions of fertilisers and crop protection agents in 2027

6. In addition, greenhouse horticulture has drawn up an overview of measures that can be seen as “good housekeeping” (Platform Duurzame Glastuinbouw, 2024). These are measures that are not currently covered by legislation, but which can be expected of good management and contribute to the prevention of fertiliser and plant protection product emissions. The measures range from limiting the use of chemical crop protection agents to good understanding and control of the water technical installation.

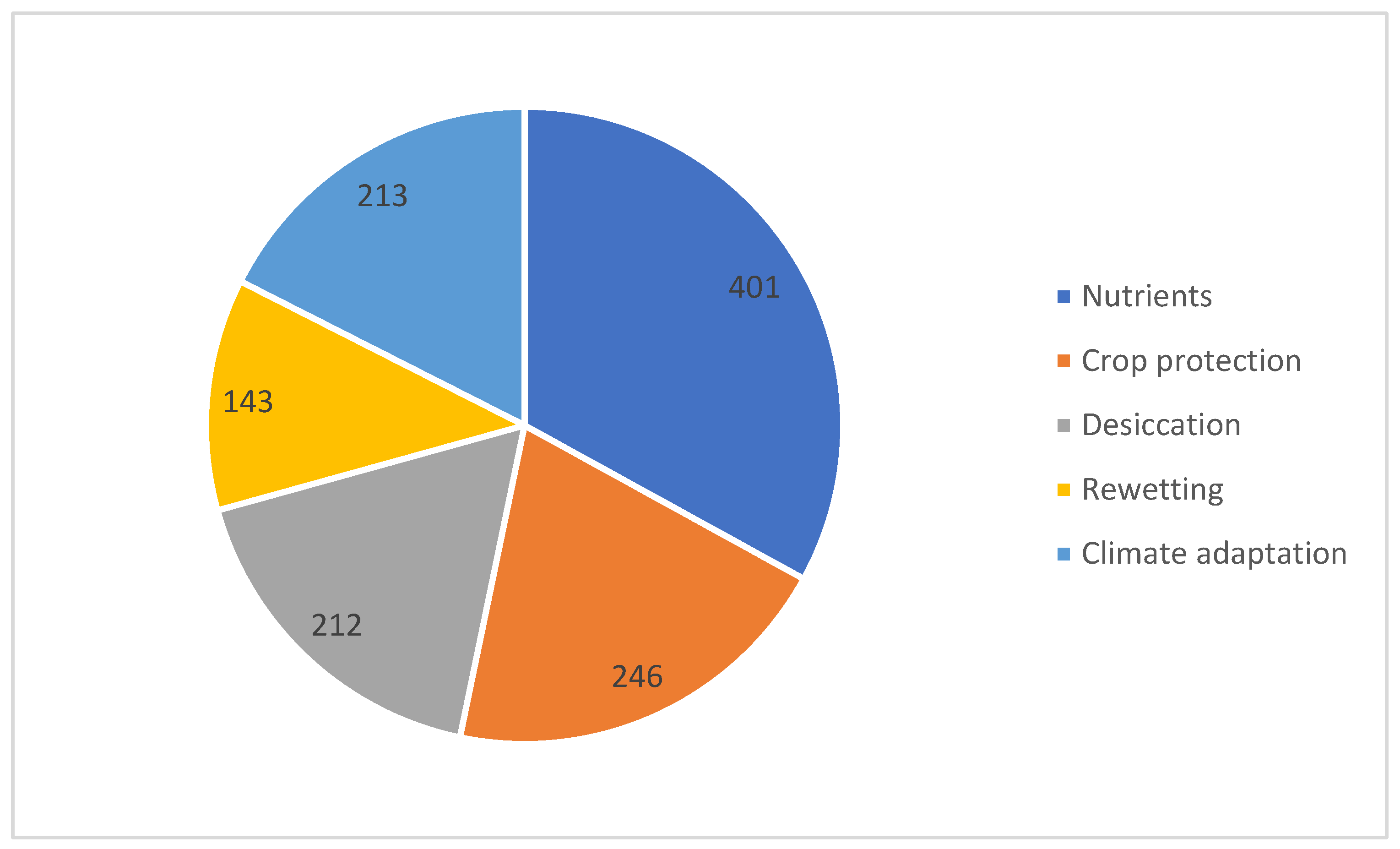

Figure 4 shows that until 2021, DAW projects have primarily been focusing on nutrient efficiency, but also on crop protection, desiccation, and adaptation, and less on rewetting agricultural land (although often measures have multiple impacts).

A broad monitoring exercise among DAW participants was undertaken in 2024 by Voesten, et al. (2024), for which seventy-six interviews were conducted within eight different DAW projects covering the wide range of DAW initiatives. This monitoring shows that DAW projects do facilitate the transition process towards more sustainable agricultural practices (Voesten et al. 2024):

80% of the interviewees see tangible outcomes through their participation in DAW projects,

89% of interviewees started new activities through participation in DAW projects and

84% have concrete plans for the near future.

Most participants (67%) focus on optimising their current operations,

30% report trying to improve existing practices in the process,

37% change towards activities that are better for the environment,

22% focus on a more sustainable long-term goal for their own business, contributing to meeting environmental and nature goals, and finally,

11% have not yet taken any steps as a result of participating in a DAW project.

3.3. Results on Individual Measures: The ‘Farmers for Drinking Water’ Project

With respect to the type of measures, DAW focuses on promoting future-proof farming practices. These measures sometimes go beyond the optimisation of farm management processes, water quantity measures, and optimising mineral utilisation. For most projects monitoring of environmental effects has not taken place, which makes it difficult to present detectable changes in (ground)water quality, though there are examples of projects where monitoring data is available. This section will shortly discuss one of them, the Farmers for Drinking Water project in the Dutch province of Overijssel (Van den Brink et al., 2021).

Due to the combination of soil type and low groundwater levels, in the Netherlands, 34 groundwater protection areas can be considered to be the most leaching-sensitive and therefore the most vulnerable groundwater protection areas. In a large number of these areas, the target of 50 mg nitrate per litre in upper groundwater was not met. Since 2017, measures have been taken in these areas to reduce nitrate leaching from agricultural sources through adjustments in agricultural management. To this end, an administrative agreement that defined an “additional approach to nitrate leaching from agricultural operations in specific groundwater protection areas” (the “Administrative Agreement nitrate”) was signed on December 12, 2017 by the relevant ministries and stakeholder organisations as part of the Sixth Action Programme Nitrate Directive (Rietberg et al., 2022; Tweede Kamer, 2024). The agreement aimed at reaching this target with a voluntary, area specific approach. Under the condition that if targets were not met in time, mandatory measures will be imposed on all farmers in the area. So, the measures are voluntary, but not without obligation. This led to a relatively high participation level of more than 80% in most areas.

One example of this approach is the ‘Farmers for Drinking Water’ project in Overijssel, one of five Dutch provinces containing the thirty-four most vulnerable groundwater protection areas. The project was launched as part of the administrative agreement on nitrates (Van den Brink et al., 2021). The project aimed to address water quality issues related to groundwater, which serves as a source of drinking water. The project began in the recharge areas of five vulnerable drinking water abstractions and later expanded to seven areas. It promoted agricultural management through farm management plans based on the Annual Nutrient Cycle Assessment (ANCA; In Dutch ‘kringloopwijzer’; de Vries et al., 2020) for nitrogen, which included measures to reduce nitrogen surpluses, with targets set at 80–100 kg N/ha/year. The project raised awareness among farmers about reducing nitrate concentrations in groundwater, and many farmers adopted measures to address it. As a result, farm management practices changed significantly over time, with measures related to cattle, feed, soil, and crop management having the highest uptake rates (Van den Brink et al., 2021).

Although the project successfully reduced nitrogen surpluses by 40% over 3-5 years, it did not lead to sufficient improvement in groundwater quality. This in part may be attributed to the before mentioned fact that these regions are very leaching-sensitive and vulnerable, which was the primary reason to choose those regions in the first place. In addition, the choice of monitoring groundwater quality at the groundwater protection area (GWPA) level, rather than the farm level, limited the direct feedback on agricultural management (Van den Brink et al., 2021).

3.4. Results of the SWOT Analysis

As stated in

Section 2, a SWOT analysis was conducted to categorise the wealth of information that was collected. In this section, we will present the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats of DAW, as identified by the stakeholders that were interviewed.

Table 2 summarises the most important results in terms of headline messages. The remaining part of this section will provide more detailed information on the various messages.

3.4.1. Strengths

DAW offers a significant outreach to like-minded farmers who are interested in the same type of measures but may not always have heard about the particular project, e.g., because the original project took place on the other side of the country. An illustrative example is the "Fertile Cycle" project (in Dutch: Vruchtbare Kringloop), which started in the Dutch region of Achterhoek

8, but the successes in this region encouraged the spread of similar projects throughout the country

9. This project uses a mineral accounting system, the Annual Nutrient Cycle Assessment (In Dutch: KringloopWijzer) to provide dairy farmers with suggestions on how they can make more efficient use of the nutrients, get healthier soils, reduce fertiliser inputs, and increase profitability. The use of data and figures played a vital role in the project, allowing farmers to measure and compare their farms with colleagues.

“The D of DAW also stands for ‘Dialogue’, since one of the most important aspects of DAW is that it facilitates the dialogue between farmers and water managers. We cannot underestimate the value of that.”10 The interviews indicate that the strength of the DAW lies mainly in bringing together different actors – farmers, water managers, government parties – and exchanging knowledge and experience with each other in an informal way. This approach provides farmers with concrete perspectives for action at the plot and farm level. In other words: translating European policies/guidelines into 'what can I do?' Farmers are far more receptive to learning from their peers and practical experiences than from government officials or reports. Programmes like "Koeien & Kansen" (‘Cows and Opportunities) serve as excellent examples of how collaborative efforts involving farmers, research institutions, and advisory services can facilitate knowledge exchange and practical implementation.

11 In this project, a group of sixteen dairy farmers together with researchers look for the possibilities of sustainable and socially accepted dairy farming. These participants gained practical experience that can be used for wider practice. As a result, measures can take place more cost-effectively and with less risk.

12

Furthermore, effective cooperation relies on creating a safe environment for farmers to experiment with measures and fostering enthusiasm among individuals within relevant organisations. For example, in the BodemUp project in the province of North Brabant farmers work together to improve soil and water quality and reduce nitrate leaching in groundwater protection areas.

1314 BodemUp started in 2018 with four groundwater protection areas, and has subsequently been rolled out across Brabant (DAW, 2021). The Business Soil Water Plan (In Dutch BedrijfsBodem Water Plan; BBWP) was developed; a tool that gives farmers, advisers, and policymakers insight into more sustainable soil and water management. An evaluation study by Ros et al, (2020) already showed that farmers are positively stimulated by the customisation provided in the BBWP. The scoring system used makes them and the advisors enthusiastic about taking even more measures than originally intended. For them, a BBWP translates the somewhat abstract area specifications into measures that make a positive contribution to the quality of the living environment on their farms. In 2024, 650 farmers participated in this project (Timmermans et al., 2025). Assisted by a soil-coach, they completed the BBWP and implemented measures on their farms. The positive experiences in Brabant stimulated also farmers in other provinces to use the BBWP (see

Table 3 for the number of hectares in various provinces where BBWP is applied)

15.

Ultimately, DAW shows that the most effective approach remains engaging directly with farmers and water managers in the field. Here practical experiences and conversations result in mutual learning and understanding, driving meaningful change, and fostering a shared commitment to sustainable agricultural and environmental practices. This enables bridging the gap between policy and the kitchen table, both in terms of content and process.

"You only gain entry to farmers when you focus on the soil; that's where the shared interest lies. Trying to engage them from the perspective of water quality does not excite them."16 Furthermore, DAW has appeared to be an efficient mechanism for allocating subsidies (such as those in the framework of the Common Agricultural Policy) to the proper destinations. This applies to both the provinces who are responsible for deciding on what measures can be subsidised, and farmers who want to apply for subsidies. In order to guide provinces in implementing the Rural Development Programme (RDP3) between 2010 and 2015 the BOOT

17 list was developed

18. This list specifies which measures that support agricultural water management can be included in subsidy schemes. To determine eligibility for subsidies under RDP3, experts have evaluated inter alia which measures from the BOOT list can be considered "productive". The BOOT list 2022 has been updated to reflect current technology and knowledge and currently contains 85 non-statutory agricultural measures that farmers can take to improve water quality, water quantity, and soil quality. The list provides links to factsheets with additional information and references to scientific literature, which serves as a resource of information for farmers, provinces, and regional water authorities.

19 For individual farmers, it is often difficult to understand what subsidies are available and how they could apply for them, and the administrative requirements for POP3 projects are often too complex to make it attractive to apply for subsidies. Furthermore, the processing time of a grant application often does not align well with farming practice. Therefore, subsidy schemes need to be made much easier on the front end. That is why – as part of DAW – in various regions portals have been built, such as the Landbouwportaal Noord Holland.

20 This portal was initiated by various stakeholders, including LTO Noord, agricultural collectives, the province, and regional water authorities in North Holland. The portal focuses on improving various aspects of farming in North Holland through five main themes: runoff of minerals and nutrients, sustainable soil management, plant protection products, sufficient freshwater, and parcel and river bank design and management.

21 Similar initiatives have been initiated in other regions of the Netherlands following its success in North Holland.

22

Finally, personal contact, with genuine attention to the specific needs and knowledge of practical solutions, is important, as is shown by the project ZON, Zoetwater Oost Nederland.

23 This project focuses on research into current and future drought problems and possible solutions and measures. Factors contributing to success include kitchen table conversations, a human-centric approach, and independent advice at the farm level.

3.4.2. Weaknesses

In the previous section it was already illustrated that, whereas the number of projects is distributed relatively evenly across the various provinces, as can be seen in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, DAW is not (yet) relevant for all agricultural sectors. As Figure 5 shows, DAW is primarily applied in arable farming and dairy farming, and not at all or much less in other agricultural sectors. This bias can also be seen in the BOOT list where more measures related to dairy farming and arable farming are included than measures related to intensive livestock farming and greenhouse horticulture. The same bias can be seen with respect to the type of topics addressed by most projects. They have long been focused primarily on optimising farm management practices, water quantity management, and nutrient efficiency. Only in more recent years, soil quality has emerged as a crucial factor to address, not only to reduce losses of nutrients, but also increase harvest and to make it less sensitive to climate-change related pressures like drought.

DAW works with encouragement (helping to do things differently, future-proof) and not with restrictions. However, up until now, according to some interviewees, the communication has been too much focused on the carrot (voluntary measures with potential for subsidies), and less on the stick. Additional measures will have to be implemented if the objectives of the European Directives are not met. If this had been communicated more strongly, the uptake of voluntary measures might have been significantly higher. In addition, as in many other initiatives, in DAW individual people may be very important to the success of the program. DAW was started by some enthusiastic initiators and promotors, but when they retire or get other jobs, a temporal dip in the drive may rise. And although new people may give new energy and new perspectives, stability is also important.

The voluntary character of the DAW measures can be considered to be a strength, since it allows farmers to decide whether they want to participate or not, depending on their assessment of the suitability and attractiveness of the individual measures for their own situation. This voluntariness applies to whether or not they want to participate, which measures they want to sign up for, and the level to which they want to apply the measure (the entire farm, or just a few hectares). However, this voluntary character of DAW often leads to scattered projects: one farmer participates, then two neighbouring farmers do not, and then another one does. Large numbers of non-participating farms limits not only the effectiveness of measures, but also the opportunity to monitor the effectiveness of measures, and the potential role of social interactions as a kind of peer pressure. The latter can be a subtle but effective way to enhance measure implementation, but it works only if enough neighbours participate. In addition, within a diverse group of participants, the absence or non-compliance of neighbouring farmers — particularly those considered laggards or persistent violators — can damage the reputation of the collective, for example through repeated exceedances of standards for plant protection products. This is obviously extremely frustrating for farmers doing their utmost in DAW. That is why in groundwater protection areas farmers themselves called for enforcement.

Since the start of the programme, DAW has intensively monitored participation degree and the impact of the projects regarding awareness and knowledge sharing. However, as stated before, monitoring and proving effectiveness of individual measures has started only recently and is difficult. That is why insight into the actual environmental effects is quite limited for most projects. If environmental monitoring took place, the measurement and monitoring of effects are conducted differently in each project, tailored to the content and circumstances of that specific project. As a result, there is a lack of evidence regarding the overall effectiveness of measures.

An additional problem when trying to prove effectiveness of measures is the generally slow response of the system to changes in the agricultural management. For example, measures may lead to effects in the upper groundwater within a period of four to at most ten years. For deeper groundwater, residence times range between decades and thousands of years. Therefore, it may take that same amount of time before adverse effects of human activities on groundwater quality are noticeable near drinking water wells. In line with that, remedial measures may take equally long to be effective (vd Brink et al, 2021). As a result, it is not always possible to see any measurable impacts of measures only a couple of years after the measures have been implemented. This means that the success of DAW cannot always be measured directly by water quality monitoring results but may take a long time, while administrators are often impatient. It is important to note that the fact that it takes time before effects will show in monitoring data is independent of whether the measures are taken voluntary in the framework of the DAW or forced by law.

Monitoring is also important to show farmers that measures work, and also may be cost-effective, and to convince funding agencies that measures are meaningful. For example, if farmers do not see the positive effects of projects on agriculture such as flower-rich ditch banks, they might stop the measure after the subsidy ends. It is therefore important to make farmers aware that this measure can actually save money (e.g. on the use of plant protection products), and in this way ensure that the good practices continue beyond the subsidy period. Although the effects of DAW on water quality may only be visible after many years, impacts on business profitability or soil quality may be visible more quickly. Therefore, for a few years now, in one of the projects, a system based on key performance indicators (KPIs) is in place:

24. Using these KPIs may offer opportunities for DAW to gain better insight into the impact of DAW projects.

In addition, more attention could be paid in the project description to the importance of monitoring, where it is crucial to also conduct a proper baseline measurement; otherwise, one still cannot demonstrate the effect of a measure. If project data is available, it is beneficial to share that information. For example, in the BodemUp project, presented in the previous section, a lot of information has been collected at the farm level (to provide farmers with insight into what they can do better). However, farmers do only want to share this information with the government for research purposes at a higher, aggregated level, as they are afraid that information at farm level might ultimately be used as a tool for enforcement.

3.4.3. Opportunities

The concept of ‘voluntary but not without obligations’ has proven to be effective and useful to create mutual understanding between various parties involved and showed the importance of the interlinkages between them. The DAW approach focuses primarily on the bottom-up collaboration between participants and governments. In addition, due to an increasing mutual interest, collaboration between DAW and agricultural nature conservation collectives is increasing. Within the framework of the DAW, several initiatives have been developed that support farmers to take environmental measures.

DAW provides support to farmers who want to take steps forward. Those who have participated have had easier access to knowledge and support in adapting their business operations. This way, they are also better prepared for future policies. As individual farmers across the country participate in activities and projects, and the growing number of soil coaches who can offer support during the transition from DAW and adjacent programmes, the expectation (hope?) is that many more agricultural businesses will benefit from this in the near future.

"After all, it is often the small but valuable steps that inspire others to also look further into their own business operations. By supporting many farmers in taking small steps, we may get further than if only a few companies make big leaps."25 The networks, tools, and platforms established for DAW are well-functioning and could be extended to other policy areas as well (e.g., water quantity management, climate adaptation) and other programmes in the rural area.

"Soil quality is an important connecting theme within DAW. Measures that contribute to soil quality also make business operations less vulnerable to changes arising from various directions, ranging from weather extremes to stricter regulations regarding the use of fertilisers and crop protection products.” 26 Compliance with water quality regulations is seen as the biggest soil and water-related challenge for the coming period, according to a survey by LTO-Noord.

27 Additionally, a perception study conducted by De Lauwere et al. (2024) shows that a significant portion of farmers are not aware that many of the measures imposed by national policy aim to improve water quality. Through DAW's channels, this awareness can be increased, and the link can be made with targets that are more appealing to farmers, such as improving soil quality. If farmers have a better understanding of what the impacts are of the measures they implement and why, this enhances intrinsic motivation, which is a far more powerful drive for them than having to do something because of a legal requirement. Communication is key for successful implementation. If these measures can also contribute to a better business model and lower costs, that is obviously another important consideration for an agricultural entrepreneur.

A good example of knowledge dissemination in which DAW collaborates with other parties (in this case LTO and BO Akkerbouw) is the “emissiereductiesprint”

28: an information campaign in which the initiators have shared knowledge, tips, and experience stories via social media and trade media, in order to activate arable farmers to reduce the emission of crop protection products. The online media campaign focused on sharing practical tips and stories of experience and encouraged arable farmers to get started themselves. Posts from the campaign were seen 150,000 times online and has led to over 25.000 interactions with the targeted audience

29.

The DAW Krimpenerwaard & Schieland project

30 is a long-term collaboration project where measurements are taken, study groups share knowledge, and there is intensive cooperation between governments and farmers. It has eighty participating farmers who together manage 60% of the Krimpenerwaard area. Learning from and with each other, with a mix of different farmers in the study groups turns out to be highly effective, as knowledge from colleagues is more easily accepted. In 10 years time, this project has shown that better nutrient utilisation, good silage management and a clean yard have a beneficial effect on water quality

31.

As the European Environmental Agency showed (EEA, 2024), pressures by the agricultural sector are still one of the main reasons why it is hard to achieve water quality objectives (including those of the WFD) in many countries in Europe. That is why ever more countries are looking for opportunities to stimulate the uptake of environmental measures by agriculture. Not only by implementing more stringent objectives at the general level, but also by using more tailor-made solutions. Being one of the first programmes of this kind in Europe offers opportunities to share lessons and experiences of DAW with other countries who are now thinking about similar projects. At the same time, these initiatives in other countries offer opportunities to learn from them how they have mastered the weaknesses and threats encountered by DAW. In this way DAW can be used to inspire other countries and vice versa.

3.4.4. Threats

DAW was initiated to take major steps to improve regional and local surface water quality, by offering the opportunity for regional and local customisation of measures, as an alternative to being forced to apply generic measures. However, it is important to acknowledge that DAW is a complementary effort and should not replace regulatory measures. In addition, the limited visibility of impacts of many DAW measures is largely due to factors such as slow-moving groundwater and is not related to whether the measure is implemented because of a legal requirement or voluntarily. Moreover, the fact that DAW shows effects only later should not be a reason to impose mandatory measures since the effects of those mandatory measures will also only become visible after many years.

"Seeing visible results from a changing approach takes time. I hope that society will give us that time.”32 Furthermore, there is a need for objective farm advisors who are accepted by farmers as knowledgeable. These advisors, possessing expertise in both environmental issues and agricultural practices, are crucial for bridging the communication gap. However, currently, there is a shortage of independent farm advisors. The integrated knowledge policy of the OVO triad (education, extension and research) had been particularly effective in the post-war decades in improving efficiency, reducing costs and increasing productivity in agriculture (De Haas, 2013). But the dismantling of this triad, especially the dissolution of the Agricultural Extension Service (DLV), has resulted in a lack of independent advisors. Nowadays, advisors come mostly from suppliers of plant protection products or animal feed, while advisors from regional water authorities may lack the knowledge to function as agricultural advisors. In addition, these advisors must also be able to convince farmers. For instance, not fertilising after ploughing is a new insight, and farmers are hesitant to implement this. Convincing farmers to use new techniques not only requires substantive knowledge from advisors, but also specific communication and social skills, as farmers may feel a certain risk in deviating from conventional practices.

Financial incentives, including subsidies, play a significant role in driving the adoption of measures. Therefore, subsidy schemes need to be easily accessible and sufficiently high in order to be attractive to farmers. Accessibility not only refers to where and how one can apply for subsidies, but also to the time between the investment by the farmer and the receipt of the subsidies. Farmers are often not able to pre-finance large amounts of money, not knowing whether they will be (partly) reimbursed. Furthermore, farmers are afraid that once the effectiveness of certain measures is established, they may be incorporated into policies, making them obligatory and no longer eligible for subsidies. Their fear is stimulated by the fact that the overarching objective of DAW to tackle water quality issues is not likely to be met on time, which may eventually lead to additional mandatory requirements without financial support. Therefore, there is a need to enhance participation (by using subsidies) and to ensure its voluntary nature, as the voluntary aspect serves as a motivating factor. However, at some point, measures often become part of the forerunners' normal agricultural operations. If measures become widely adopted, for a level playing field and the prevention of unfair competition, there will come a time when legislation and regulations could force laggards to take emission-reducing measures that the frontrunners have already taken.

Finally, it is important that DAW should remain independent and supported by agricultural stakeholder organisations and not perceived (by farmers) as a policy instrument. DAW is recognised and acknowledged by many parties and increasingly used to attach (top-down) funding for various purposes. Yet that is not the DAW approach. In this way, it becomes more of a national funding programme instead of a grassroots agricultural programme. DAW is not a state implementation regulation. It is important to ensure that DAW remains voluntary and maintains its bottom-up approach, as this is precisely the strength of the programme. In the addendum of the 7th NAP (National Action Plan) some DAW measures are made mandatory, making them no longer eligible for subsidies, which may undermine the support for DAW as a whole. Furthermore, as seen in the 34 groundwater protection areas – where farmers have achieved notable results in improving agricultural mineral management

33, reducing nitrogen surpluses, and limiting nitrate leaching – the withdrawal of the derogation was perceived as a punishment for good behaviour.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper explored the key achievements and limitations of DAW over the years and highlights its evolving role in the context of changing environmental and agricultural landscapes. The DAW programme has achieved considerable progress in certain aspects while facing challenges in others.

Since its start in 2013, the Dutch ‘Delta Plan for Agricultural Water Management’ has evolved from a modest initiative into a nationwide platform encompassing over 500 projects across various provinces in the Netherlands. Several projects started small —such as the Fertile Cycle project — and then successfully expanded further. Among DAW’s most significant successes is its role as a robust platform for knowledge distribution and open communication among farmers, agricultural organisations, water managers, and ministries, leading to more mutual understanding. This approach has facilitated trust-building, knowledge exchange, and experience sharing, and has enhanced collaboration among stakeholders (Voesten et al., 2024; DAW, 2024). It has also contributed to improved agricultural management practices, economic benefits for farms, and the implementation of measures that may reduce agricultural impact on ground- and surface water quality. DAW has created a 'laboratory' for testing new measures in a relatively safe environment, offering farmers the opportunity to choose cost-effective, tailor-made solutions to meet environmental goals. This approach has contributed to broader participation and more successful implementation of measures.

However, DAW has also faced several challenges and limitations. Since the focus of DAW is limited to the major agricultural sectors its impact is not covering the full agricultural area. Furthermore, the shortage of independent farm advisors limits the support available for farmers who might be willing to adopt new measures.

On top of that, the voluntary nature of DAW has led to uneven participation among farmers, resulting in a fragmented implementation of measures and complicating the assessment of their overall effectiveness. Although monitoring and evaluation were embedded in the programme from the outset, it remains difficult to isolate and quantify the specific effects of DAW interventions. The fact that most participants are front runners makes it even harder to assess DAW’s impact on the broader farming community. Without adequate enforcement towards laggards and persistent non-compliers, the gains made by early adopters’ risk being offset, and water quality improvements may remain obscured, further complicating evaluation efforts. Some interviewees argue that a stronger emphasis on the ‘stick’ — for instance, by linking DAW more directly to the threat of additional generic policies — might have increased participation and reduced the current mosaic of compliant and non-compliant farmers. However, the more measures become mandatory, the less opportunities there are for an instrument such as DAW that stimulates voluntary measures in addition to existing requirements.

Despite these challenges, DAW has shown that engaging directly with farmers and water managers in the field, where practical experiences and open dialogue drive meaningful change and foster a shared commitment to sustainable agricultural and environmental practices, is a valuable and indispensable complement to national policy. Looking ahead, this type of collaboration is expected to become even more essential in the face of climate change, increasing instances of drought and flooding, persistent water quality issues, and evolving agricultural demands under initiatives such as the EU Green Deal and the Farm to Fork Strategy. As this paper has demonstrated, DAW is well-positioned to continue playing a central role in addressing these complex and dynamic challenges while promoting a more sustainable agricultural future. In recent years, several other countries have developed programmes similar to the Delta Plan for Agricultural Water Management, aimed at supporting farmers in going beyond legal requirements, particularly regarding climate adaptation and water management. Although a comparative analysis of these initiatives was beyond the scope of this article, it presents a promising direction for future research — to better understand common success factors and areas of concern across different countries and contexts.

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

The Cadaster was still part of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management at that time and could be well utilised as an implementing organisation for this purpose. |

| 5 |

The Water Caravan has driven 10 times in 2024 (DAW, 2025). |

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

The total number of projects presented in this graph is 561. In addition there are 17 national projects. These have not been included in this graph. |

| 8 |

|

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

One of the respondents during the interviews (but similar comments were made by others). |

| 11 |

|

| 12 |

Ibid. |

| 13 |

|

| 14 |

|

| 15 |

Provinces with less than 10 participants are not included in this table. |

| 16 |

One of the respondents during the interviews (but similar comments were made by others). |

| 17 |

BOOT is the acronym for Bestuurlijk Overleg Open Teelt en Veehouderij; Dutch for ‘Administrative Consultation on Open Cultivation and Livestock’. |

| 18 |

|

| 19 |

xxxx. |

| 20 |

|

| 21 |

Subsidies are granted for measures that have not yet started and fall outside existing laws and regulations. The regional water authority manages the grant applications, conducts checks on implemented measures and recovers subsidies if necessary ( https://landbouwportaalnoordholland.nl/). Eight months after the launch, more than 600 farmers had already applied for coaching on their own farms, and around 700 farms had already registered for a scheme (DAW, 2019). |

| 22 |

|

| 23 |

|

| 24 |

Samen op weg naar duurzame landbouw - BoerenKPI |

| 25 |

One of the respondents during the interviews (but similar comments were made by others). |

| 26 |

One of the respondents during the interviews (but similar comments were made by others). |

| 27 |

|

| 28 |

|

| 29 |

|

| 30 |

|

| 31 |

Ibid. |

| 32 |

One of the respondents during the interviews (but similar comments were made by others). |

| 33 |

As previously presented in this paper, it was known that, mainly due to the vulnerability of those areas to leaching, these efforts were still not enough yet. |

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Rob van der Veeren, Sandra Plette and Cors van den Brink; Data curation, Servaas Damen and Patrick Goorhuis; Formal analysis, Rob van der Veeren and Sandra Plette; Investigation, Rob van der Veeren; Methodology, Rob van der Veeren; Writing – original draft, Rob van der Veeren; Writing – review & editing, Sandra Plette, Servaas Damen, Xander Keijser, Patrick Goorhuis and Cors van den Brink. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding Information

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We thank the interviewees for their responses during the interviews and their valuable feedback on the preliminary draft of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The views expressed in this document are the personal professional views of the authors and do necessarily represent the views of any other body referred to or that the authors have worked with or for.

References

- Van den Brink, C.; Hoogendoorn, M.; Verloop, K.; de Vries, A.; Leendertse, P. Effectiveness of Voluntary Measures to Reduce Agricultural Impact on Groundwater as a Source for Drinking Water: Lessons Learned from Cases in the Dutch Provinces Overijssel and Noord-Brabant. Water 2021, 13, 3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of the European Communities (1991). Council Directive 91/676/EEC of 12 December 1991 concerning the protection of waters against pollution caused by nitrates from agricultural sources (European Nitrate Directive), Official Journal L 375, 31/12/1991 P. 0001 - 0008. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/1991/676/oj.

- Council of the European Communities (1992). Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora. Official Journal L 206, 22.7.1992, p. 7–50. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/1992/43/oj/eng.

- DAW (2016). Jaarverslag Deltaplan Agrarisch Waterbeheer 2014 – 2015. https://agrarischwaterbeheer.nl/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/jaarverslag_2014-2015_def.pdf.

- DAW (2019). Jaarverslag 2018. https://agrarischwaterbeheer.nl/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/jaarverslag_daw_2018_0.pdf.

- DAW (2021). Jaarverslag 2020. https://agrarischwaterbeheer.nl/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/daw_jaarverslag_2020_1.pdf.

- DAW (2022). Jaarverslag 2021. https://agrarischwaterbeheer.nl/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/daw_jaarverslag2021_web.pdf.

- DAW (2023). Jaaroverzicht 2022. https://agrarischwaterbeheer.nl/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/daw_jaaroverzicht_2022.pdf.

- DAW (2024). Jaaroverzicht 2023. https://agrarischwaterbeheer.nl/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/daw_jaaroverzicht_2023.pdf.

- DAW (2025). Jaaroverzicht 2024. https://agrarischwaterbeheer.nl/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/DAW_Jaaroverzicht2024_digitaal.pdf.

- EEA (2024). European Environment Agency, Europe's state of water 2024 – The need for improved water resilience, Publications Office of the European Union, 2024. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2800/02236.

- European Parliament and the Council of the European Union (2000). Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy (European Water Framework Directive). Official Journal L 327, 22/12/2000 P. 0001 – 0073. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2000/60/oj.

- Fraters, B., A. Hooijboer, A. Vrijhoef, A. Plette, N. van Duijnhoven, J. Rozemeijer, M. Gosseling, C. Daatselaar, J. Roskam, H. Begeman (2020). Agricultural practices and water quality in the Netherlands; status (2016-2019) and trend (1992-2019): The Nitrate rapport 2020 containing the results of monitoring effects of the EU Nitrates Directive action programmes; RIVM, Bilthoven. [CrossRef]

- Haas, M. de (2013). Two centuries of state involvement in the Dutch agro sector: An assessment of policy in a long-term historical perspective. The Hague, November 2013. https://english.wrr.nl/binaries/wrr-eng/documenten/publications/2013/11/04/two-centuries-of-state-involvement-in-the-dutch-agro-sector/Web072e-Two-centuries-state-involvement-Dutch-agro-sector.pdf.

- van der Heide, C.M.; Silvis, H.J.; Heijman, W.J. Agriculture in the Netherlands: Its recent past, current state and perspectives. Applied Studies in Agribusiness and Commerce 2011, 5, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoben, R.; Verhagen, F.; Schoffelen, N.; Rost, J. (2021). Ex Ante Analyse Waterkwaliteit. https://open.overheid.nl/repository/ronl-709bd885-7ea6-441c-b2df-7f65f4fe68e2/1/PDF/ex-ante-analyse-waterkwaliteit.PDF.

- Lauwere, C, de, F. Langers, T. de Boer, J. Beirnaert, and M. Weegels (2024). Resultaten van interviews met sectorvertegenwoordigers, een enquête onder agrarische ondernemers en 7 focusgroepen. Wageningen Economic Research, Wageningen, augustus 2024. https://open.overheid.nl/documenten/a1789e32-274c-474e-a13b-aeffd04ef4f0/file.

- Meadows, D. H., and the Club of Rome (1972). The Limits to growth; a report for the Club of Rome’s project on the predicament of mankind. New York: Universe Books, 1972. https://collections.dartmouth.edu/content/deliver/inline/meadows/pdf/meadows_ltg-001.pdf.

- Meester, G. Naar een nieuw evenwicht tussen markt en overheid. In Landbouwbeleid: waarom eigenlijk? Silvis, H.J., Ed.; Den Haag, LEI, LEI-rapport: 6.04.07; 2004; ISBN 90-5242-905-7. https://edepot.wur.nl/22791.

- Meststoffenwet. Wet van 27 november 1986, houdende regelen inzake het verhandelen van meststoffen en de afvoer van mestoverschotten. Staatsblad 1986, 598. https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0004054/2024-01-01.

- Ministerie van Economische Zaken (2013). Tweede Kamer, vergaderjaar 2012–2013, 33 037, nr. 63. https://www.tweedekamer.nl/downloads/document?id=2013D18745.

- Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Milieu (2013). Brief Minister van IenM aan RBO-vz over Schoon water en KRW planning.

- Pierhagen, E. Research challenges for the Mansholt Institute. In Rural reconstruction in a market economy; Heijman, W., Hetsen, H., Frouws, J., Eds.; Wageningen: Agricultural University. Mansholt Studies, 1996; https://edepot.wur.nl/442564ISSN 1383-6803.

- Platform Duurzame Glastuinbouw (2024). Goed huisvaderschap. Brf 24.037 GM/SvD, april 2024. https://www.glastuinbouwnederland.nl/content/user_upload/Brf_24.037_GM-SvD.pdf.

- Rietberg, P. Rietberg, P., A. van Loon, and E. Hees (2022). Nitraat besturen, hoe dan? Advisering BO Nitraat in grondwaterbeschermingsgebieden. CLM, publicatienummer 1117, juni 2022. 2024. https://www.eerstekamer.nl/overig/20241106/clm_kwr_advisering_bo_nitraat_in/document.

- Rijksoverheid (2024). Regeerprogramma; Uitwerking van het hoofdlijnenakkoord door het kabinet. 13 september 2024. https://open.overheid.nl/documenten/ronl-f525d4046079b0beabc6f897f79045ccf2246e08/pdf.

- Slagter, L., M.H. Roseboom, D. van Wieringen, I.H. Phernambucq, R.L.J. Nieuwkamer, L.C. Oosterom, E.C.M. Ruijgrok, and L.G. Turlings (2024). Koepelrapport tussenevaluatie KRW. 11 december 2024. https://open.overheid.nl/documenten/dpc-7c016640aa2cfd17d6b4259834d61d2acaa90f52/pdf.

- Timmermans, B., T. van der Voort, J. Geurts, A. van Loon, G. Ros, Y. Fuijta, H. Gelderblom, A. Hoek van Dijke, B. Avezaat, R. van de Logt, and T. Bovee (2025). BodemUP 2.0 Monitoring Voortgangsrapportage 2024. 55 p. Publicatienummer: 2025-6402-LbP. https://www.louisbolk.nl/sites/default/files/publication/pdf/bodemup-20-monitoring.pdf.

- Tweede Kamer (2024). Effecten van maatregelen op nitraat in het agrarische deel van grondwaterbeschermingsgebieden. 33.037, TK, 563, 6 november 2024. https://www.eerstekamer.nl/behandeling/20241106/brief_regering_effecten_van/document3/f=/vmite562xfxo.pdf.

- Van der Veeren, R.; van der Molen, D.; Groen, S. How to Stimulate the Water and Agriculture Nexus? Journal of Environmental Science and Engineering B 2017, 6, 362–369. https://www.davidpublisher.com/Public/uploads/Contribute/5a0cf5709b152.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Van Gaalen, F.; Osté, L.; van Boekel, E. Nationale analyse waterkwaliteit; Onderdeel van de Delta-aanpak Waterkwaliteit. Den Haag: Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving. 2020. https://www.pbl.nl/downloads/pbl-2020-nationale-analyse-waterkwaliteit-4002-0pdf.

- Voesten, M.; Laan, M.; Nikkels, M. Brede monitoring DAW-project; Inzichten in succesfactoren, verbeterpunten, impact en bijdrage aan transitie. Rapport, Aequator Groen + Ruimte bv. 86p. 2024. https://agrarischwaterbeheer.nl/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/rapport-brede-monitoring-DIGITALE-VERSIE-met-bijlage.pdf.

- Vries, M. de, van Dijk, W., de Boer, J. A., de Haan, M. H. A., Oenema, J., Verloop, J., & Lagerwerf, L. A. (2020). Calculation rules of the Annual Nutrient Cycling Assessment (ANCA) 2019: background information about farm-specific excretion parameters (update of ANCA report 2018). (Report / Wageningen Livestock Research; No. 1279). Wageningen Livestock Research. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).