1. Introduction

Water, energy, food, and ecosystems are the cornerstones of long-term societal and economic stability, as they provide the foundation for public well-being, the welfare state, peace, and security [

1,

2]. Yet, as global population and urbanization continue to surge, so does the demand for these essential resources. The world faces the unprecedented challenges of extreme weather events and shifting climatic conditions, which further threaten the resource security and the integrity of ecosystems [

3,

4].

The Mediterranean area, in particular, is exposed to a multiplicity of stresses, from water scarcity to water pollution, degradation of natural resources, high levels of food loss and waste, and increasing demand for energy and food. Agricultural practices, urban development, water demand, and protection of ecosystems, are areas of specific interest for the decision-makers, who are responsible for defining interventions aimed at enhancing the availability of water for the various competitive water-uses. In this context, it becomes widely clear that addressing challenges related to water, food, and ecosystems in isolation is not appropriate [

5] Rather a holistic, integrated, and cross-cutting approach is required, as embodied by the Water-Ecosystems-Food (WEF) Nexus. The WEF Nexus underscores the interdependence of water, food, and ecosystem security. This approach identifies mutually beneficial responses based on an understanding of the synergies between water, ecosystem, and agricultural policies, while also highlighting potential conflicts and unintended consequences. It offers a transparent framework for assessing trade-offs and synergies that protect the sustainability of ecosystems while aligning with long-term economic, environmental, and social objectives. Therefore, adopting a WEF Nexus is not merely a choice, but emerges as essential to pave the way for a green economy while striving to achieve Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

6].

Nonetheless, the transition from theory to practical application using the WEF Nexus approach is not straightforward and entails multiple difficulties. Implementing this approach requires collaboration among diverse sectors and stakeholders, demanding a coordinated effort [

7]. Stakeholders play an important role in assessing the WEF nexus, as many policy choices affect their possibility of making use of environmental goods and ecosystem services [

8]. The challenge lies in persuading communities, decision-makers, and the private sector that embracing a holistic Nexus approach, rather than pursuing disjointed sectoral actions, brings a wide range of collective benefits [

9]. To overcome this barrier, researchers need to expand their toolkit to provide policymakers with compelling demonstrations of Nexus solutions. For the management of the WEF Nexus, increasing attention is being directed towards the employment of Nature-Based Solutions (NBSs), especially in regions dealing with challenges related to water scarcity and environmental degradation [

3,

10].

NBSs for climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction can be defined as actions that work with and enhance nature to restore and protect ecosystems, to help society adapting to the impacts of climate change, and to slow further warming while providing multiple additional benefits (environmental, social and economic) [

11,

12]. While not an entirely novel concept, the prominence of NBSs gained momentum in the early 2000s. Initially conceptualized as a nature-centric response to climate change challenges, it garnered support from influential entities like the International Union for Conservation of Nature [

13]. Subsequently, the European Commission recognized the imperative of establishing a term that embraces the various existing approaches. NBSs operate as an overarching concept, encompassing a spectrum of terminologies, including ecosystem-based approaches, ecosystem-based adaptation, ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction, green infrastructure (both blue and green), and sustainable management (including ecosystem-based and sustainable forest management) [

14,

15].

NBSs, which protect and restore natural ecosystems and/or utilize diverse native species, can play a key role in ensuring climate change mitigation and adaptation services, while also contributing to cultural ecosystem services such as inspiration and learning from nature [

16].

NBSs play a crucial role in tackling the interconnected challenges within the WEF Nexus. These approaches utilize natural processes to achieve a balanced and sustainable management of water, ecosystems, and food resources. Over the past decade, the term NBSs has surged in popularity, mirroring the amplified acknowledgement of nature's pivotal role in bestowing a diverse array of benefits upon human communities across local, regional, and global scales through sustainable socio-ecological systems [

17]. The essence of NBSs lies in their inherent multifunctionality, serving as solutions that yield manifold environmental, social, and economic advantages. They intricately interlink disaster risk reduction, climate change mitigation and adaptation, and the restoration and safeguarding of biodiversity and ecosystems within sectoral interventions and policies.

Currently, the majority of scientific research on NBSs has been conceptual, offering either principles and frameworks for implementation and/or assessment, or reviews of the origins and use of the concept, with little empirical research [

18,

19,

20,

21]. It is widely recognised that the implementation of NBSs within the framework of the WEF Nexus requires a robust policy and governance framework that can effectively address the complex interactions between natural resources and social systems [

1,

13].

This study presents the results of the comprehensive analysis carried out within the project "LENSES - LEarning and action alliances for NexuS EnvironmentS", funded by the European Union under the "PRIMA Foundation" programme. Activities were implemented in six pilot areas spread over five Mediterranean countries, i.e., Greece, Italy, Jordan, Spain and Turkey. A participatory approach was used to identify and deeply analyze the WEF Nexus challenges affecting the selected pilot areas, following the methodological framework described in Baratella et al. [

22], and to collect information about barriers and opportunities for implementing NBSs to tackle identified challenges. Building a catalogue of NBSs was a process refined through careful consideration of the manifold challenges faced in different geographical areas. This comprehensive assessment facilitated the identification and subsequent selection of the most relevant NBSs, the ones that better than others could help in tackling the specific local challenges. As fundamental added value, after developing an analytical evaluation framework and a comprehensive catalogue of Water-Energy-Food (WEF) Nexus-related Nature-Based Solutions (NBSs), the identified solutions were implemented in 4 pilot areas to assess at the local level the improvement of the sustainability and multifunctionality of managed agro-ecosystems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pilots Areas and Main Challenges

Six pilot areas were selected across five Mediterranean countries (i.e., Greece, Italy, Jordan, Spain and Turkey). In general, the challenges affecting the selected pilot areas mainly relate to competitive water and land uses in agrifood systems aimed at food production, conservation of forests and natural ecosystems, recreational (e.g. tourism), and other activities (industrial production, etc.). All pilot areas represent typical Mediterranean conditions, in terms of e.g. climate conditions and climate change impacts, interaction between surface water and groundwater, competitive uses of the resources, relevance of agricultural activities, types of crops, social context and stakeholders.

Figure 1 shows the pilot locations, while their background and specific challenges are described in

Table 1.

Stakeholders were involved in three main phases during the identification of NBSs through a participatory approach: at the beginning of the activities, a large group of stakeholders identified the WEF challenges of their pilot areas through tailored participatory activities, which included participatory mapping and System Dynamics Modelling [

22,

23]. Then, the actors defined the NBSs adapted to be applied in their study area, and finally, a small group of actors more interested and/or directly involved in NBSs implementation responded to a questionnaire to give their opinion about NBSs effects and define the main barriers and opportunities of the NBSs implementation. In 3 pilot areas (Greece, Jordan and Turkey), some NBSs were implemented at the field level and results were collected.

2.2. The Catalogue on Nature-Based Solution

The participatory process of NBS selection and analysis to support Nexus optimization, is based on a (public) NBSs catalogue, accessible online to a wide range of stakeholders, among which decision-makers. The catalogue includes a list of 54 available NBS along with additional information (Type, Ecosystem services, challenges and SDGs) explained in specific factsheets, that users can explore.

The first step in this process was to critically review existing frameworks for assessing adaptation/resilient WEF Nexus options for rural areas (Step 1). The review aimed to identify commonalities and gaps in existing frameworks for addressing the WEF Nexus, as well as their applicability at different spatial scales. Following the review, a WEF Nexus framework was drafted to assess options for increasing resilience (Step 2). This “WEF Nexus assessment framework” was used to develop the NBSs Tool (Step 3).

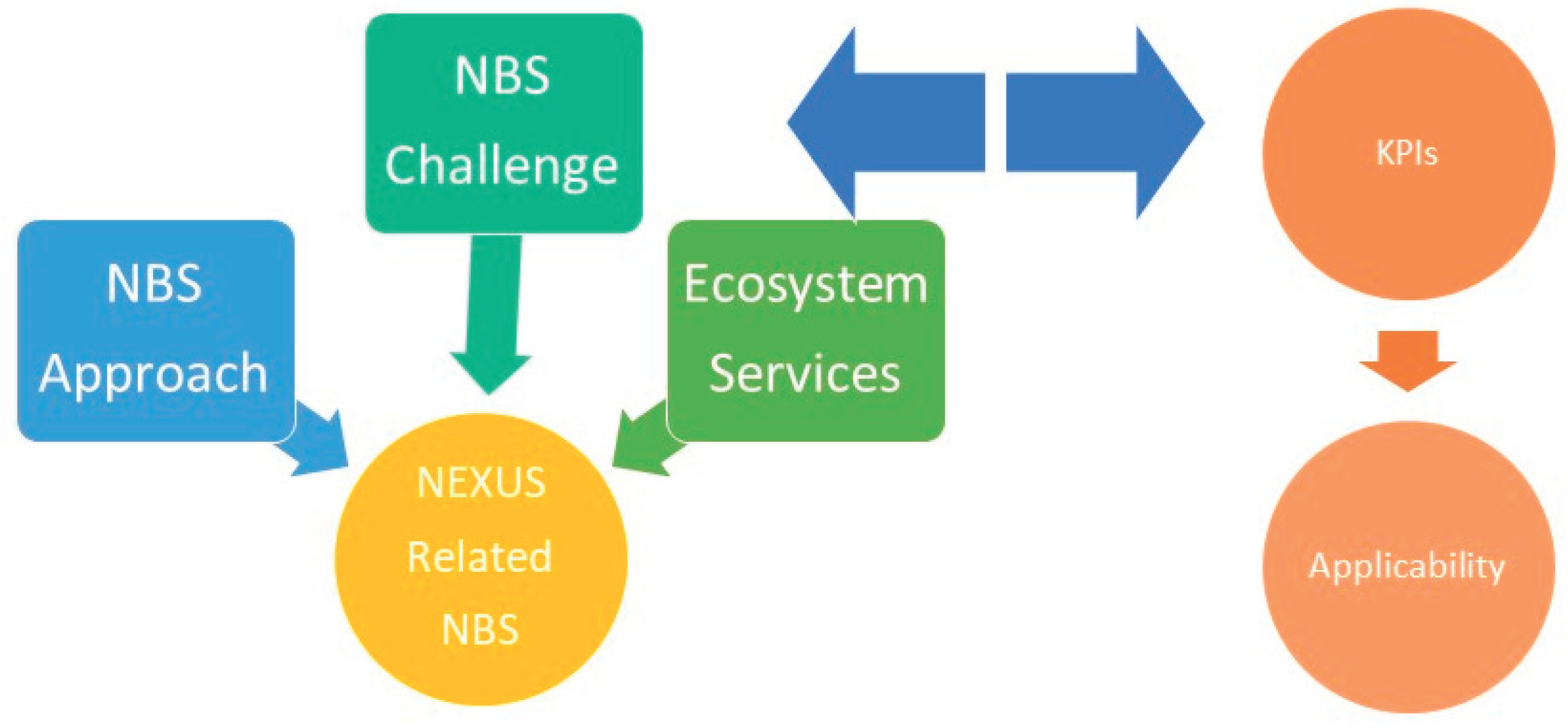

A WEF Nexus-appropriate framework for evaluating options for increasing resilience was developed and Figure 2 presents its conceptual design. The conceptual design of the framework was built upon and adapted to the NBSs classification scheme developed within the Thinknature project [

24]. The NBSs classification scheme was a result of a synthesis conducted from a literature review and stakeholder consultation/discussion on the ThinkNature platform (

https://platform.think-nature.eu/).

Figure 2.

Design of NBSs WEF NEXUS evaluation framework.

Figure 2.

Design of NBSs WEF NEXUS evaluation framework.

In this framework, a stepwise approach was followed, which phases are described below. The first phase of the methodology is the development of a vision for the landscape. This vision drives the project and the potential local stakeholders to achieve consensus and overcome the many barriers that will arise from its implementation. To develop such a vision, it is critical to identify the environmental and ecological problems of the region and define a holistic solution that will add value to the region and enhance its resilience. This vision brings local stakeholders and decision-makers on board to materialize the project [

25].

Once the challenges of the different pilot areas have been identified, a primary list of appropriate NBSs that address the vision for the landscape and the challenges were identified for each pilot area. Applying the WEF Nexus Evaluation Framework, it’s possible to identify the desired ecosystem services to obtain from the landscape as well as the approaches needed to improve ecosystem services.

At the end, related Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for each NBSs selected were identified. A stakeholder consultation (focus groups) was done on the selected WEF-optimized NBSs to revise and finalize the NBSs list in each pilot area.

Finally, a module for decision support on Nexus-related NBSs selection was developed, as well as the methodology that was followed for the implementation of the tool, which is a catalogue holding a list of existing nature-based solutions, making them available to the wider public. Stakeholders should be able to access an evidence-based framework as well as guidance to select the solutions that incorporate nature-based approaches, to increase the resilience of the water-energy-food Nexus. The module for decision support on Nexus-related NBSs selection allows the selection of NBSs and is built on available methodologies and information for selecting an NBSs. At the same time, it provides KPIs to assess their technical effectiveness; effectiveness in improving service under specific conditions, climate resilience of the solution and contribution to adaptation. The KPIs used in the module were adapted from the EU Handbook for practitioners [

26] Furthermore, the user is able through an easy-to-use and user-friendly interface to explore a list of available NBSs, search by keyword to find a specific NBSs, as well as use filters for the attributes of the NBSs to narrow down their results.

NBSs were categorized into 3 groups of type, sub-types and NBSs types. The type groups and sub-types selected by the different stakeholders in the pilot areas are shown in

Table 2.

After the selection of different NBSs types by the researcher and main stakeholders of the several pilot areas, in selected cases (Greece, Turkey and Jordan), some NBSs were implemented. In Spain and Italy, NBSs were not implemented but, recognizing the importance of local knowledge and engagement, a participatory approach was emphasized to ensure that the chosen NBSs align with the needs and aspirations of the pilot community. By involving local stakeholders, such as farmers, landowners, and residents, in the decision-making process, a collaborative environment was fostered, promoting a sense of ownership and shared responsibility for the successful implementation of NBSs.

2.3. Stakeholder Survey on NBSs Implementation

After NBSs implementation and the analyses of the first results in the different areas, a stakeholder survey was done to collect qualitative and quantitative data to assess NBSs performance and the stakeholder's interest and perceptions of the investigated system.

Data were collected through individual online or face-to-face surveys, virtual interviews, and web meetings. A questionnaire was developed to collect data about NBSs implementation. This survey, designed as a tripartite framework, reflects a tailor-made approach that takes into account the different dimensions of the project. This structured questionnaire is distinctly separated into three sections. The initial and final segments remain uniform across all stakeholders, fostering coherence and inclusivity, while the pivotal middle section dynamically adapts to the selected challenge (Water, Food, or Ecosystem). The first section begins with some information on the identification of the stakeholders and their roles within the scope of the project. It lays the groundwork for understanding their engagement with NBSs corresponding to the specific challenge they choose. The user then selected the next section, which was tailored to the chosen WEF challenge. For example, stakeholders choosing the water sector will encounter questions specific to the strategies, experiences and outcomes of water-centred NBSs. Likewise, those engaging with the Food challenge are presented with inquiries probing the efficacy of NBSs in addressing food-related challenges, and similarly for the Ecosystem challenge.

The final section is common to all stakeholders by presenting a set of overarching questions, which also include the selection of which barriers and opportunities are related to the implementation of NBSs in their pilot rural areas. This universal section aims to amalgamate diverse perspectives and experiences, fostering an environment for stakeholders to share their proposals, suggestions, and insights that transcend the confines of specific challenges. This comprehensive tripartite structure not only facilitates domain-specific insights but also affords a panoramic view of stakeholders' collective experiences, enriching the project with multifaceted viewpoints and recommendations.

2.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive analysis was done for the quantitative data collected. Qualitative data were collected using several surveys. The Likert scale was selected because offers several positive aspects: (i) greater sensitivity in measuring participants' opinions or attitudes; (ii) greater flexibility for participants to provide responses that better reflect their opinions or perceptions; (iii) Greater resolution in the data, in fact using a 7-level scale can lead to richer and more detailed data, allowing for more in-depth and informative analyses.

3. Results

3.1. NBSs Catalogue

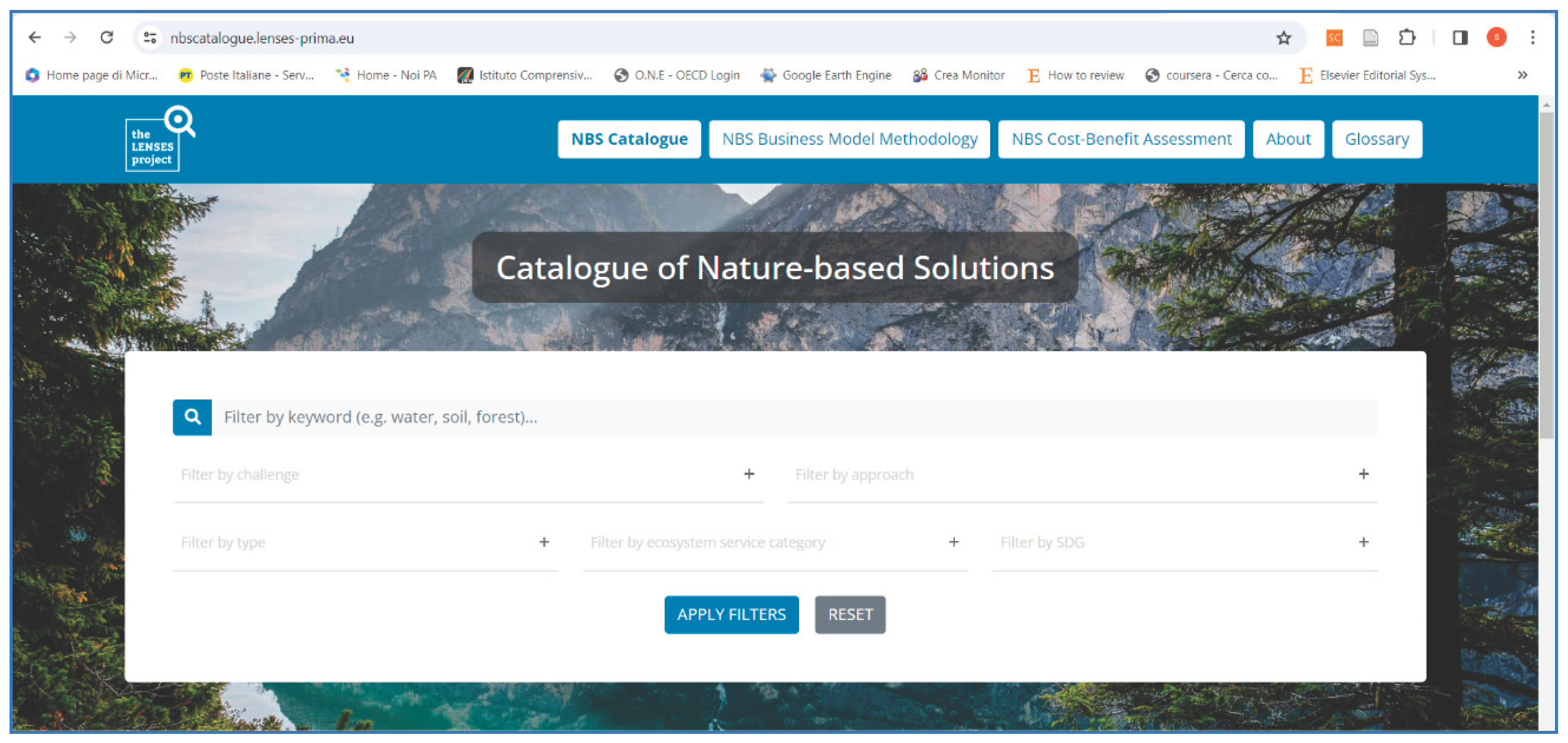

In this study, the Module for decision support on Nexus-related NBSs selection is presented, which is a catalogue holding the list of 54 existing nature-based solutions (NBSs), making them available to the wider public. Stakeholders should be able to access an evidence-based framework as well as guidance to select the solutions that incorporate nature-based approaches, to increase the resilience of the water-energy-food (WEF) Nexus. The module for decision support on Nexus-related NBSs selection allows the selection of NBSs and is built on available methodologies and information for selecting an NBSs. At the same time, it provides key performance indicators (KPIs) to assess their technical effectiveness; effectiveness in improving service under specific conditions, climate resilience of the solution and contribution to adaptation. NBSs selection is also envisaged with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with specific targets and indicators that could be achieved by implementing specific NBSs, as well as real case examples.

The NBSs framework is based on research around innovation actions that highlight the multi-functional role of NBSs and their potential ability to fulfil multiple social, economic and environmental goals. The tool is publicly available on the LENSES project website (

https://www.lenses-prima.eu/) at this link:

https://nbscatalogue.lenses-prima.eu/ (Figure 3).

3.2. Water-Ecosystem-Food Challenges

The stakeholders were selected to guarantee a good balance among the different sectors (i.e. water, food, ecosystems), the role (e.g. policy-makers, public and private decision-makers, citizen organizations, academia, etc) and including all institutional and governance levels that might be relevant to the issues at stake (i.e. national, regional, local). The following Table 3 includes a summary of the stakeholders involved (per sector), and interviewed to define the main challenges of their areas and to select the most suitable NBSs .

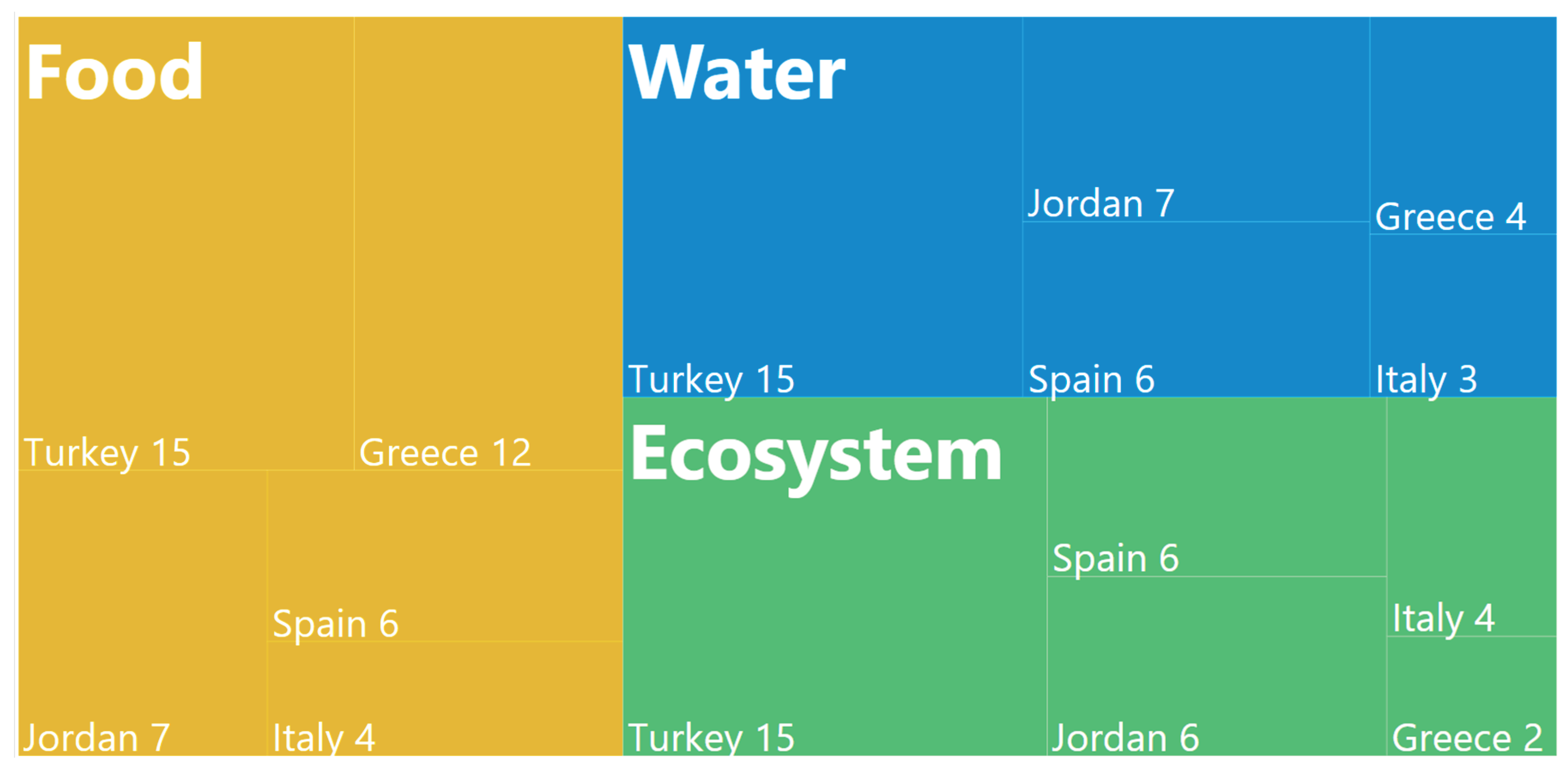

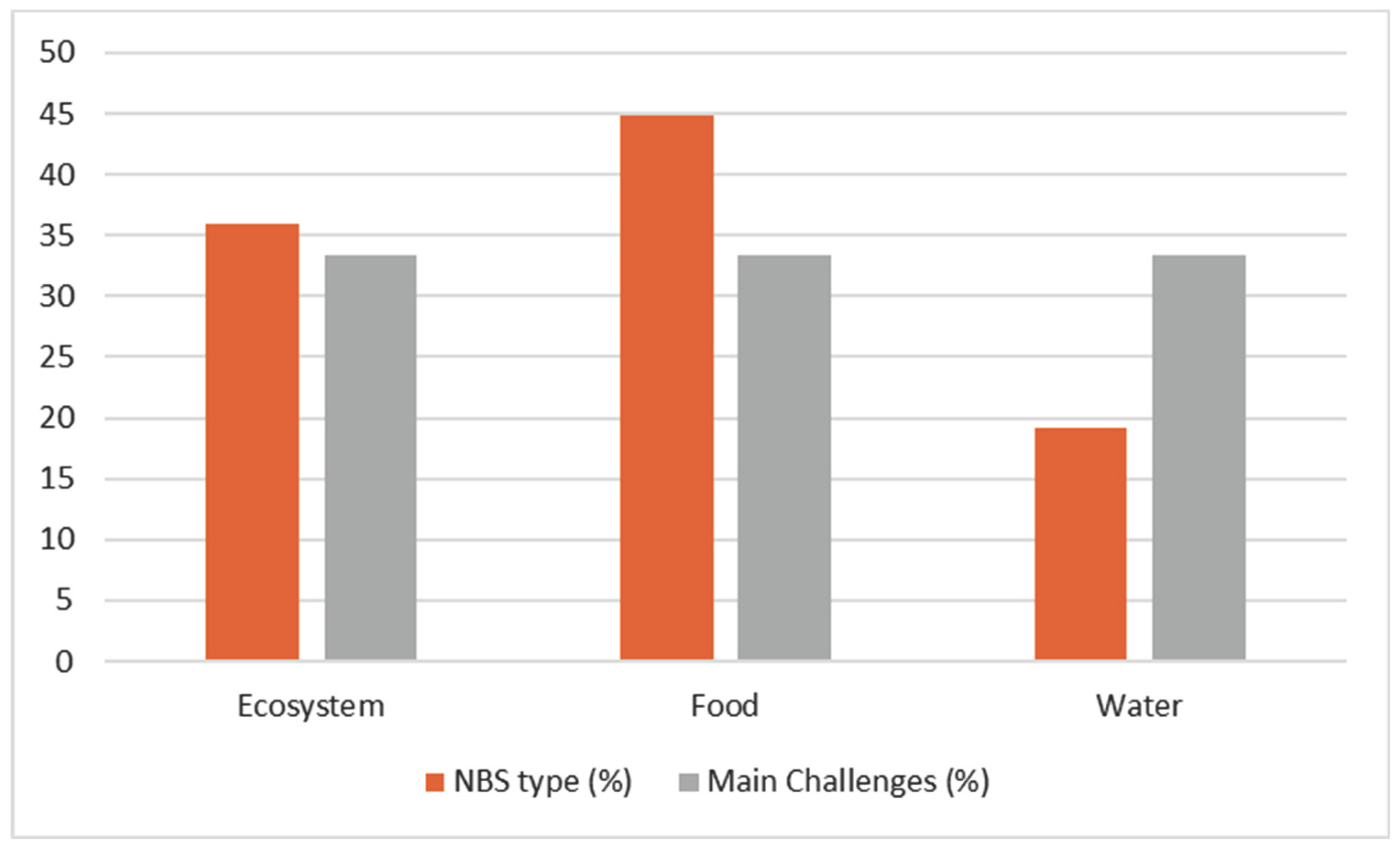

13 main challenges grouped by WEF sectors were selected by the different stakeholders of the pilot area, as shown in

Table 4. The main challenges identified are the need to “improve the water resources management”, “improve the ecosystems services”, and “sustainable agriculture development”, selected respectively by 66.6%, 50% and 50% of the pilot. The pilot issues are evenly distributed between the three different classes (water, ecosystem and food) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Initial group of stakeholders engaged in the Lenses project grouped by Water-Ecosystem-Food sector.

Figure 4.

Initial group of stakeholders engaged in the Lenses project grouped by Water-Ecosystem-Food sector.

Figure 4.

NBSs types and main challenges defined by stakeholders in the pilot areas grouped by WEF aspects.

Figure 4.

NBSs types and main challenges defined by stakeholders in the pilot areas grouped by WEF aspects.

3.3. Nature-Based Solutions Selected by Stakeholders in Pilot Areas

In all the pilot, a list of 35 NBSs were selected which have been grouped into sub-types and Group types (

Table 2). 62% of identified NBSs are related to “Type 2- NBSs for sustainability and multifunctionality of managed ecosystems”, 23% to “Type 3 – Design and management of new ecosystems”, and 15% to “Type 1- Better use of protected/natural ecosystems”. As shown in Table 3, all the stakeholders of the several pilot selected NBSs belonging to the sub-type “Agricultural landscape management” (61% of NBSs). The main NBSs selected are the following: (i) Incorporating manure, compost, biosolids, or crop residues to enhance carbon storage (selected by all the pilots), (ii) Agro-ecological practices (iii) Increasing soil water holding capacity and infiltration rates, (iv) Soil improvement and conservation measures, (v) Mulching, (vi) Use soil conservation measures: Cover crops; Deep-rooted plants and minimum or conservation tillage; Agroforestry; Wind breaks.

Table 5.

Numbers of NBSs selected by stakeholders grouped by sub-types, per each pilot area.

Table 5.

Numbers of NBSs selected by stakeholders grouped by sub-types, per each pilot area.

| NBS Sub-types |

ES

Donana

|

GR

Koiliaris

|

GR

Agia/Pinios Delta |

IT

Tarquinia

|

JO

Deir Alla

|

TR

Gediz

|

| Agricultural landscape management |

6 |

6 |

9 |

11 |

6 |

7 |

| Coastal landscape management |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

| Ecological restoration of degraded terrestrial ecosystems |

|

5 |

|

4 |

|

|

| Monitoring |

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

| Protection and conservation strategies in terrestrial, marine, and coastal areas ecosystems |

1 |

|

|

4 |

|

3 |

| Restoration and creation of semi-natural water bodies and hydrographic networks |

4 |

2 |

|

2 |

|

|

| Total |

11 |

13 |

9 |

24 |

6 |

11 |

3.4. NBSs Implemented in the Pilots

In 4 pilot areas, some NBSs were selected and implemented to solve some specific issues of the different territories.

Table 6 shows the NBSs types experimented with in the pilot areas, the challenges individuated, and the benefits of implementing.

3.5. Stakeholders' Evaluation of NBSs Implementation

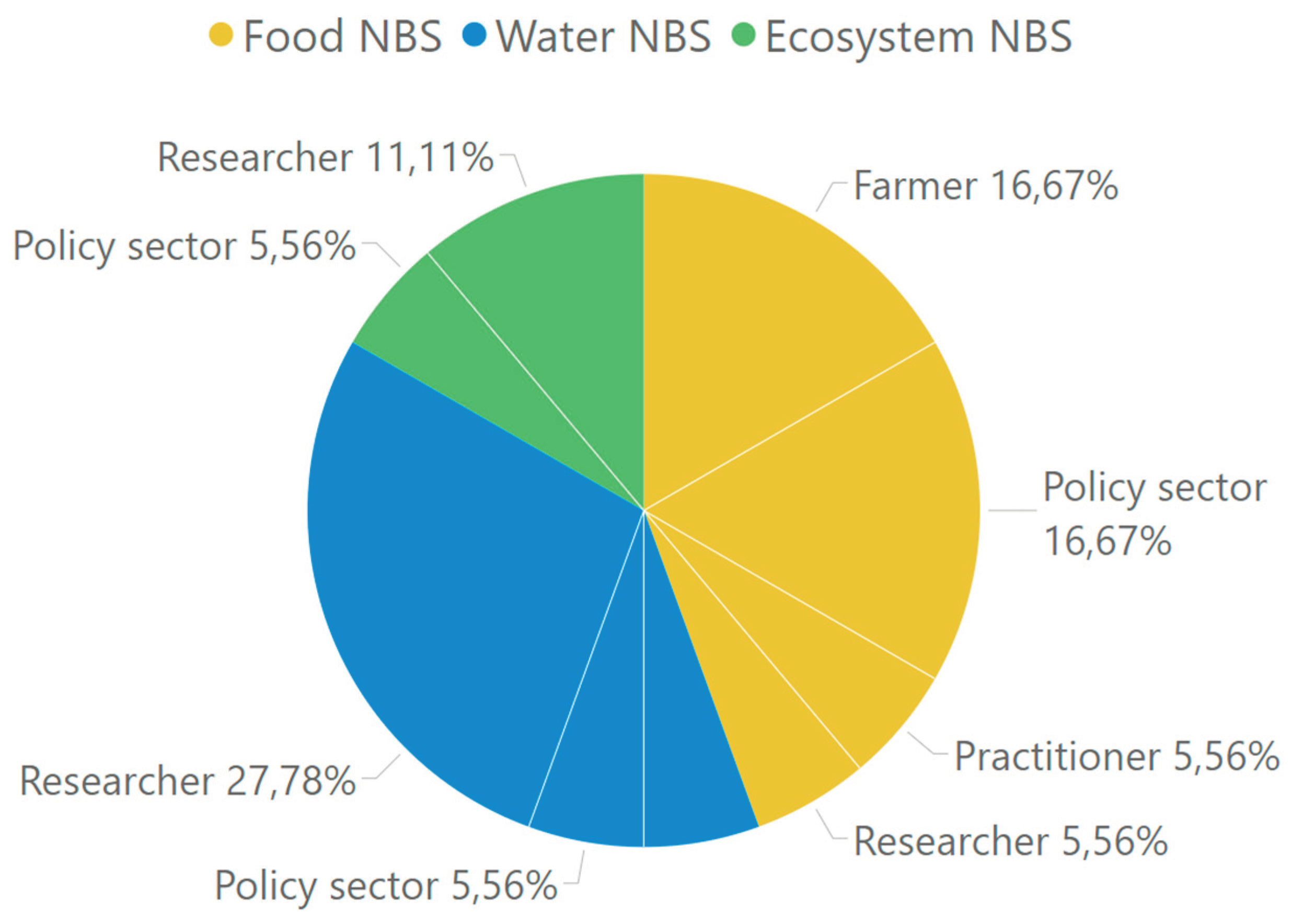

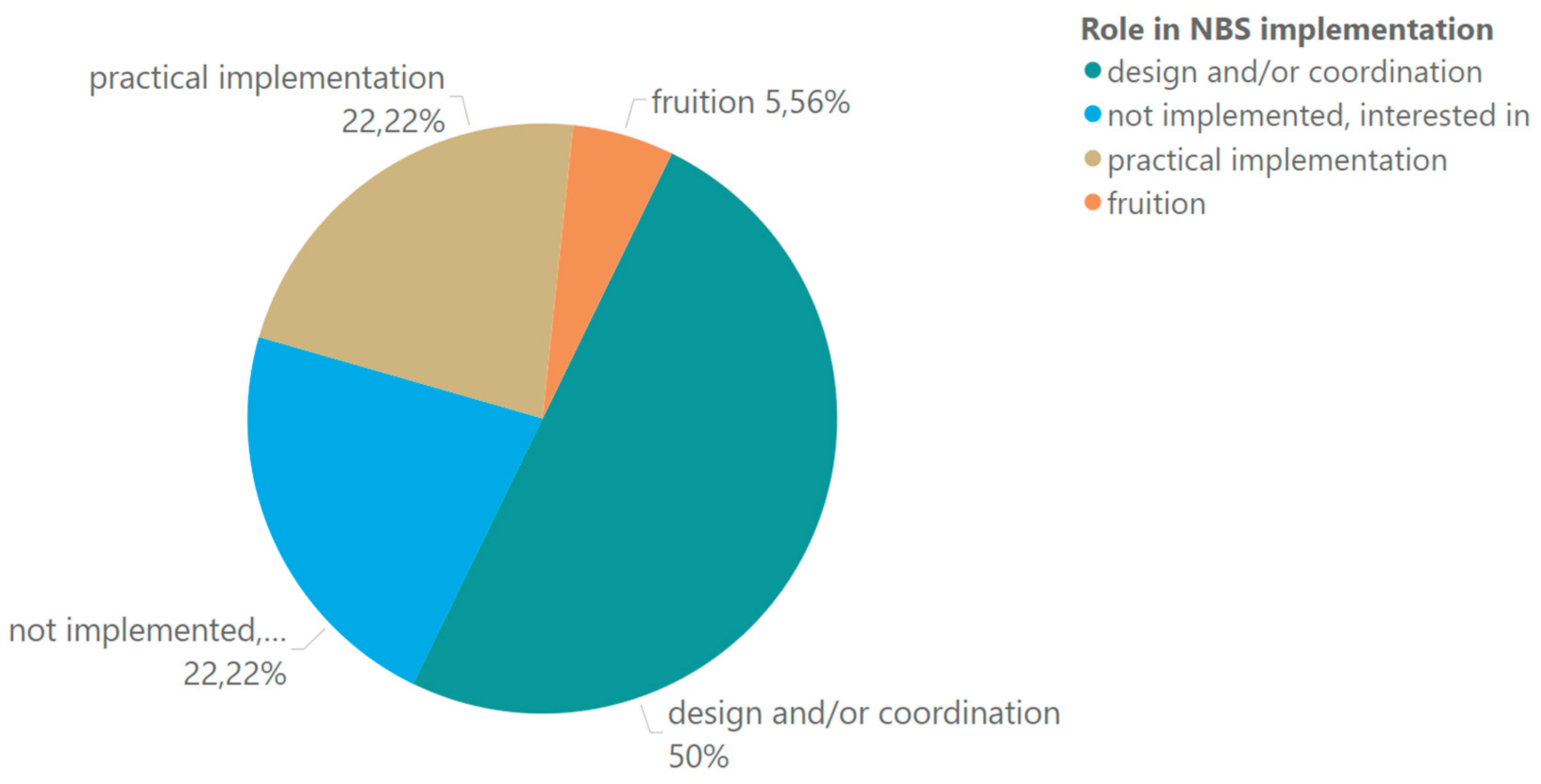

The sample involved in the final survey comprised 18 respondents: they were mainly researchers (44%), policy-makers (28%) and farmers (22%), from Greece (33%), Spain (28%) and Jordan (22%).

Figure 5 shows the different characteristics of stakeholders and their main sector of interest in NBSs.

Their role in the NBSs implementation is shown in

Figure 6: 28% of stakeholders support NBS in conceptual development and coordination in the water sector and 16% in the food sector; 22% of stakeholders didn’t implement NBS but are interested in the food sector, while the 22% of actors that supported to practical NBS implementation are equally distributed in all WEF sectors.

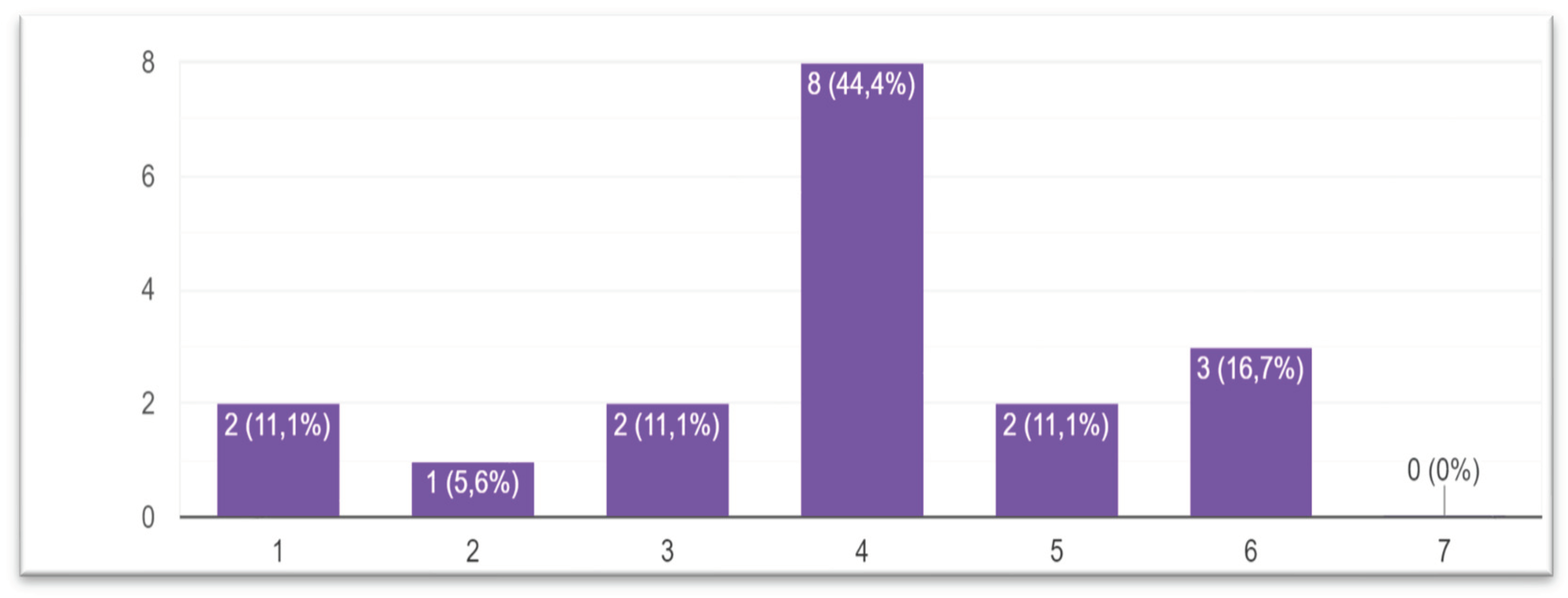

Figure 7 shows the results of the first Likert scale question asked about the level of satisfaction, ranging from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 7 (extremely satisfied), regarding "the level of community involvement in the planning and implementation of NBSs projects". Among the respondents, 44% (the majority) provided a response indicating neutrality (level 4), two respondents were extremely dissatisfied, and no respondents declared the highest level of satisfaction. The average score suggests that, in general, participants do not clearly identify NBS strategies as a valid and relevant approach to address specific environmental problems or issues, but rather remain neutral. In addition, the lack of an extremely high score could indicate that some participants may have reservations or questions about NBS strategies.

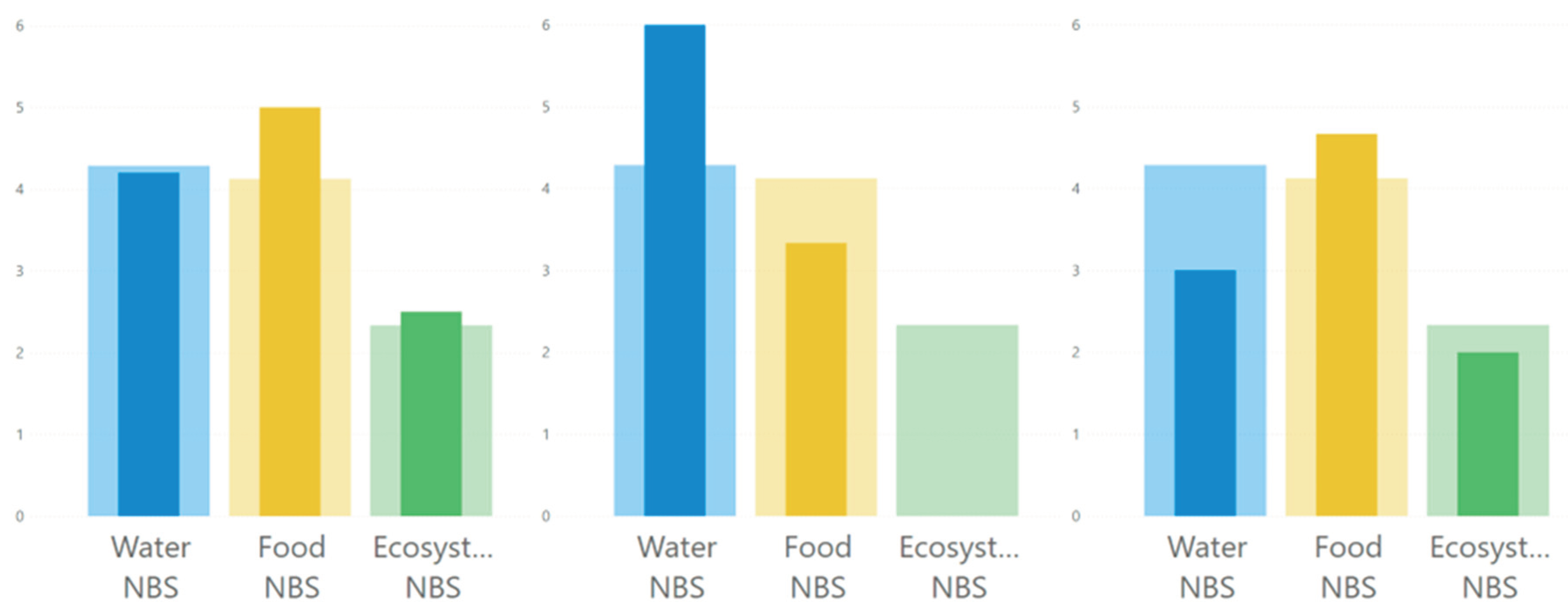

As shown in

Figure 8, researchers are mainly satisfied with the NBS in the food sector, whereas farmers are satisfied with the NBS effect in the water sector.

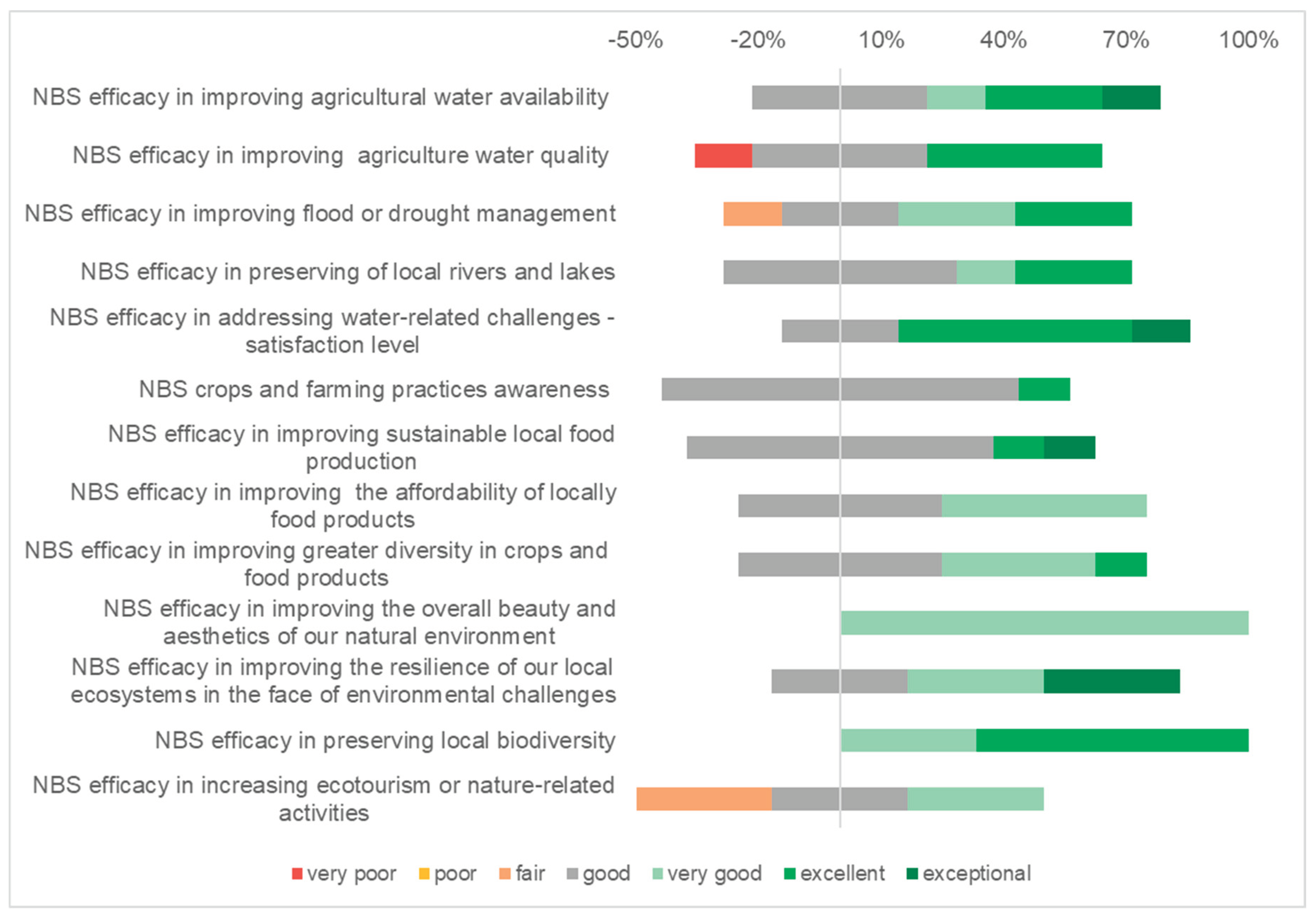

Figure 9 describes the agreement of each participant on the effects of NBSs implementation: the different questions were tailored to the WEF-specific section of NBSs. All respondents who have implemented NBSs in the different WEF sectors provided responses indicating a high level of agreement, ranging from 4 to 7 on the Likert scale.

Some stakeholders didn't see any positive effect of the use of NBSs in improving water quality in their community, 14% reported even a very negative effect, as well as in managing floods or droughts. With regard to the ecosystem sectors, the majority of stakeholders didn't see a very positive effect on the increase of ecotourism or nature-related activities.

3.6. Barriers and Opportunities Affecting NBSs Implementation

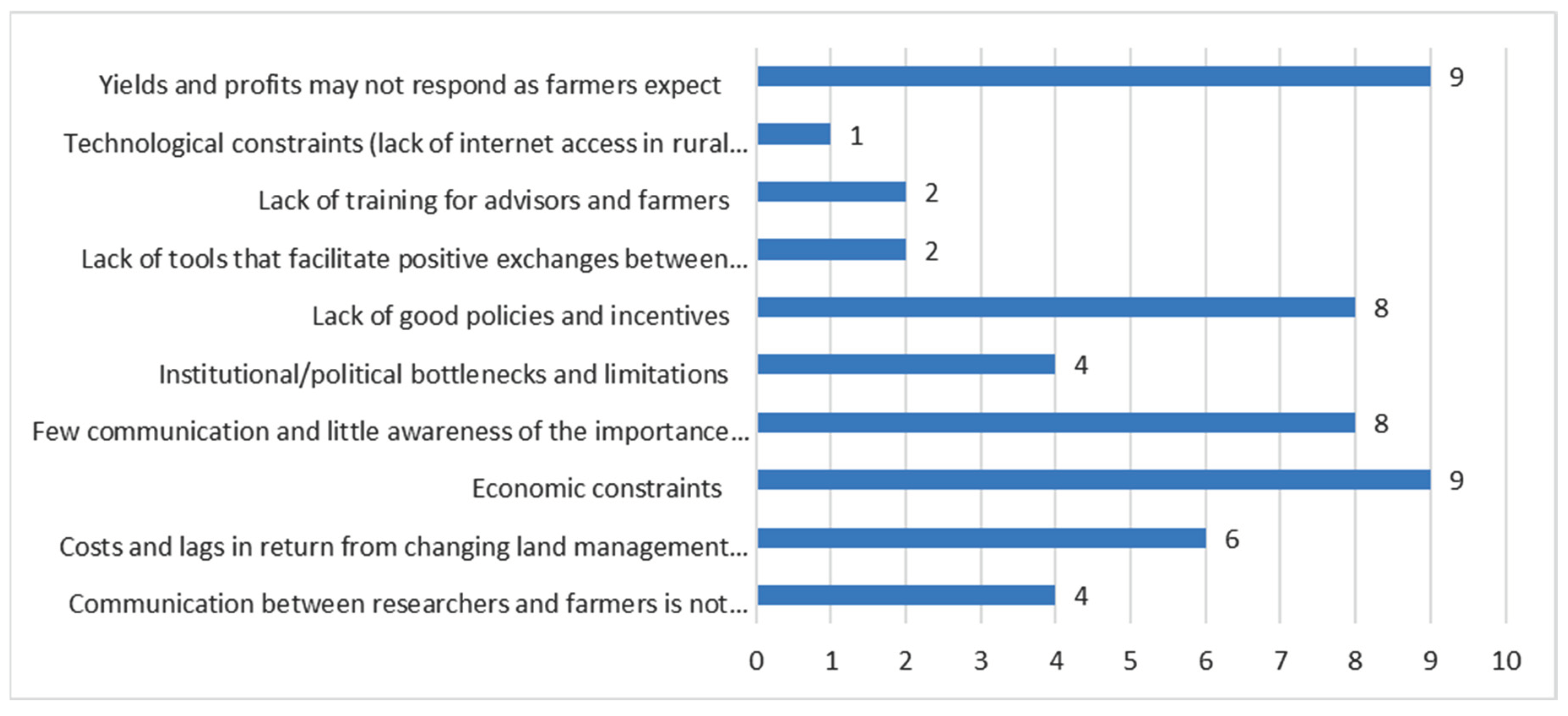

Stakeholders have the option to select a multiple choice from a range of 10 barriers and 10 opportunities to overcome barriers. The first two barriers that hinder the successful implementation of the NBSs, indicated by the respondents, are related to economic aspects: ‘Economic constraints’ and ‘Yield and profits may not respond as farmers expect’ were the most voted, with 50% of preferences. The other two important barriers (44.4% of preferences) are ‘Few communications and little awareness of the importance of NBSs in society’ and ‘Lack of good policies and incentives' (

Figure 8).

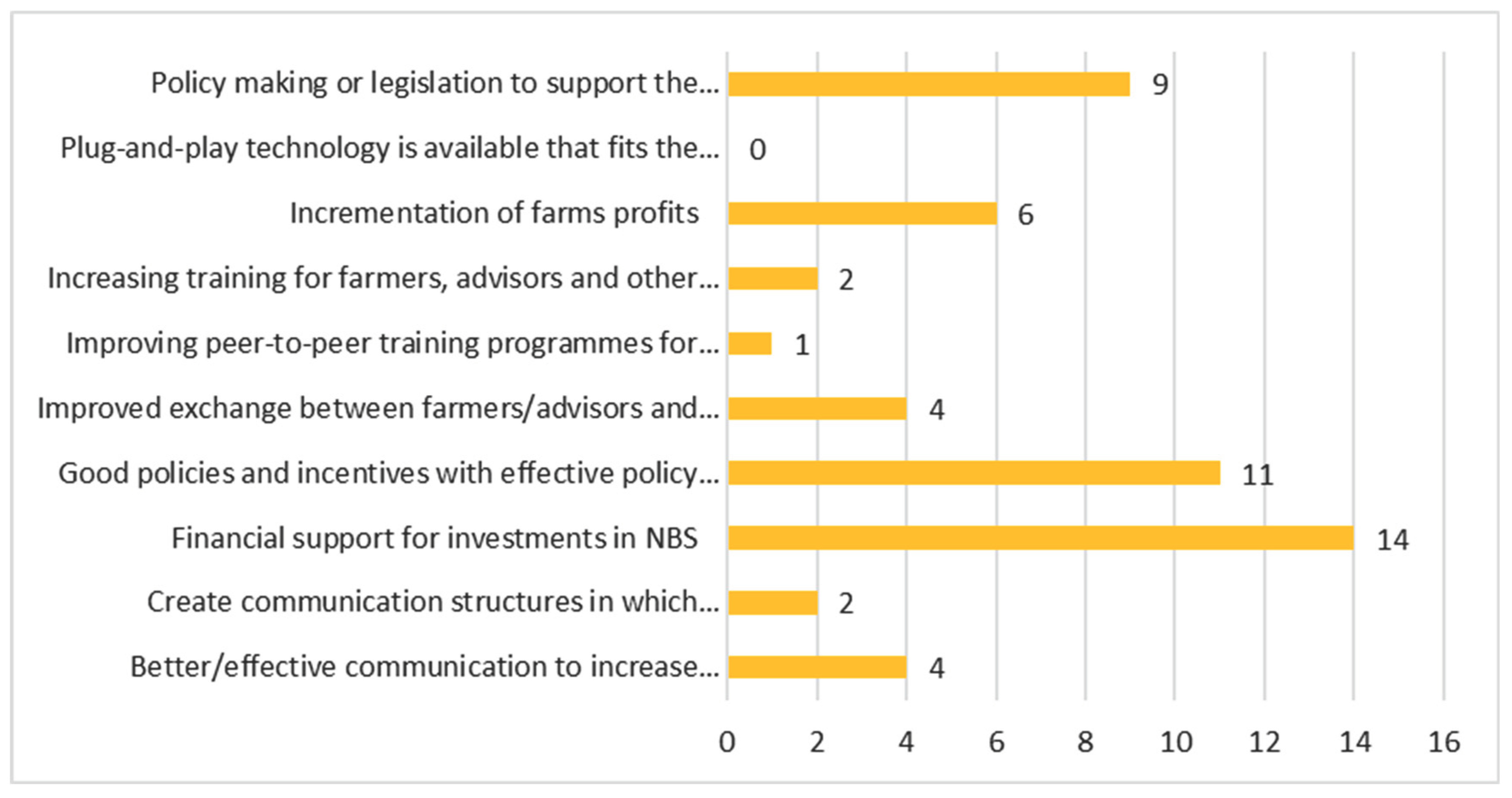

The three main opportunities to overcome the issues of implementing NBSs are ‘Financial support for investments in NBSs’, ‘Good policies and incentives with effective policy measures’ and ‘Policymaking and legislation to support the implementation of NBSs practices’, respectively with 78%, 61% and 50% of preferences (

Figure 9).

Figure 2.

Barriers related to NBSs identified by stakeholders in the 6 countries involved in the consultation campaign (numbers correspond to count of responses).

Figure 2.

Barriers related to NBSs identified by stakeholders in the 6 countries involved in the consultation campaign (numbers correspond to count of responses).

Figure 3.

Opportunities related to NBSs identified by stakeholders in the 6 countries involved in the consultation campaign (numbers correspond to count of responses).

Figure 3.

Opportunities related to NBSs identified by stakeholders in the 6 countries involved in the consultation campaign (numbers correspond to count of responses).

4. Discussion

This study aims to identify the potential role of NBSs in addressing the challenges and opportunities for a resilient Nexus in rural areas, building on the challenges identified within the pilots through a participatory approach and implementing selected NBS that can contribute to climate resilience by improving the adaptability of ecosystems to changing climatic conditions. This study shows the methodology that was followed for the implementation of the catalogue holding a list of existing nature-based solutions (NBSs) specific for rural landscapes, making them available to the wider public. The NBSs catalogue contains a total amount of 54 NBSs along with additional information for each one of them. While there is a growing evidence base on the effectiveness of NBSs approaches [

16] and increasing numbers of tools to support practitioners [

31,

32] and policy-makers in planning and application of NBSs, some important gaps remain, including on matching solutions to specific circumstances and stakeholder needs. This study will address this gap by providing the methodological and practical foundations for the selection of suites of solutions that use NBSs as an underlying principle, to be implemented in Mediterranean pilot areas. The NBSs Catalogue was developed to give decision-makers access to an evidence-based framework and guidance to support the selection of suites of solutions that incorporate nature-based approaches to address challenges in increasing the resilience of the WEF Nexus.

Summarizing the information resulting from the application of the WEF Nexus Evaluation framework, the vision of all pilots is common and threefold: (i) Increasing sustainability and re-naturalization of the landscape; (ii) Focusing on the sustainability of the agricultural sector; and (iii) Promoting the socio-economic development. The optimization of the WEF Nexus is a core issue for the sustainable management of natural resources and agricultural development. NBSs can play a key role in facilitating this optimization.

Agricultural landscape management NBSs types are the more selected from the several stakeholders of the Mediterranean pilot areas to overcome the main WEF challenges of their areas. Also, Morri and Santolini [

33] highlighted that agricultural management practices are key to realizing the benefits associated with ESs and reducing disservices from agricultural activities in an Italian region.

The survey results on the effect of NBSs implementation put in evidence that there is a general positive perception regarding the efficacy of NBSs in WEF sectors within rural communities. Smith et al. [

16] put in evidence the effectiveness of NBSs for addressing climate and natural hazards, and the outcomes for other sustainable development goals.

Stakeholders didn’t find a positive effect of NBSs application in improving water quality in the pilot areas. This is due to the very short-term of NBSs implementation: sustainable NBSs need time to see the effect on the water quality. Several studies [

34,

35] highlighted that NBSs can positively impact surface water quality in the long term, and will remain an effective strategy in the future, even under future climate conditions, while being a justified investment from an economic standpoint.

The stakeholders' consensus regarding the effectiveness of the adopted strategies is a pivotal finding, indicating the success of the NBSs initiatives within their respective communities. It suggests that the strategies have effectively addressed key challenges related to water availability, food security, and ecosystem resilience, contributing to sustainable agricultural practices and environmental conservation efforts.

In addition to defining an NBSs list tailored to specific territorial issues, it is important to establish the barriers that arise in implementing practices to seek useful needed actions. In this context, our study defined the main barriers in Mediterranean regions in the phase of NBSs implementation through a participatory approach. Economic and social barriers are highlighted by stakeholders as a priority. As described by Hallstein and Iseman (2020), any practice that reduces returns, or is perceived to reduce returns, will face high resistance to adoption. In many cases, simply the lack of concrete and specific evidence on yields and subsequent returns will prevent the adoption of new practices. Several studies in the NBSs application indicate that farmers don’t adopt sustainable practices despite having witnessed ecosystem benefits, because of increased initial costs, labour inputs, or customs and preferences [

36,

37,

38]. To maximize NBSs benefits while managing trade-offs, Smith et al. [

16] identified the support for NBSs in government policies; participatory delivery involving all stakeholders; strong and transparent governance; and provision of secure finance and land tenure, in line with international guidelines.

In the same perspective, our study moves in the same direction as the cited literature and provides evidence that financial support, sound policies, and incentives, particularly those aligned to the CAP, are crucial to pose the base for implementing NBSs at the territorial level.

As confirmed by several authors [

39,

40], legislative and financial support for NBSs cross-cuts several policy documents and sectors, and while Member State and EU policy instruments acknowledge NBSs-related concepts, they seldomly contain quantitative and measurable targets relating to NBSs placement and quality. NBSs therefore provide an important opportunity for innovation, research, business development and trade [

11].

Due to project time constraints, this paper shows only the first results of the implementation of NBSs and future studies on the current topic are therefore recommended as the monitoring of NBSs effects on WEF sectors.

5. Conclusions

The present research aimed to find the most appropriate NBSs to implement in WEF sectors in rural areas. An NBSs catalogue has been prepared and is publicly available on the LENSES project website. The stakeholders involved in the project identified the main local WEF challenges and selected a list of NBSs to be evaluated in light of the local context. In some cases, few NBSs were implemented and the first positive results were presented. A final participatory survey was done to put in evidence the main barriers and opportunities of the NBSs implementation.

The results of this investigation show that NBSs have been recognized as a promising and sustainable approach to addressing various environmental challenges, including water and food-related issues, and that economic and social barriers are the main issues in implementing NBSs. The success of NBS in Mediterranean areas would also depend on effective governance, policies, and the integration of traditional knowledge with modern approaches with the effect of improving the perception and attitude of stakeholders. Finally, it's crucial to continually assess and adapt these solutions based on monitoring and evaluation. More broadly, research is also needed to determine the effect of NBSs implementation in a long-term period on the water-ecosystem-food sector, to work in partnership with all stakeholders to tailor NBSs to a specific context, including the geographical, climatic, and socio-economic conditions of a region, and to have an effective dissemination.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing-original draft preparation: Silvia Vanino; Nikolaos P. Nikolaidis, Maria A. Lilli, Alessandro Pagano, Raffaele Giordano: Methodology, Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing; Survey and Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing: Donato Ferrari, Valentina Baratella; Data Collection, Writing - Review & Editing: Ivan Portoghese, Andrea Panagopoulos, Vassilios Pisinaras, Anna Chatzi, Zübeyde Albayram Doğan, Tuncay Topdemir, Estrella López, Luna Al-Hadidi, Nabeel Bani Hani, Sami Awabdeh, Esteban Henao, Anna Osann, Tiziana Pirelli, Fabrizio Pucci, Antonella Di Fonzo; Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing: Dimitris Tassopoulos, Christina Papadaskalopoulou, Efstathia Chatzitheodorou; Project coordination, Writing - Review & Editing: Stefano Fabiani. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was developed in the framework of the project LENSES- “LEarning and action alliances for NexuS EnvironmentS in an uncertain future”, funded by the European Union’s PRIMA Programme, under grant agreement no 2041. The contents here reported are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The Authors wish to thank Dr. Luigi Serafini, deputy major of Tarquinia Municipality, for supporting data collection in Italian pilot area, and Dr. Konstantinos Babakos and Dr. Dimitrios Malamataris (SWRI) for supporting data collection in Greece pilot areas.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- European Commission. Joint Research Centre. Position Paper on Water, Energy, Food and Ecosystems (WEFE) Nexus and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).; Publications Office: LU, 2019.

- European Commission. Joint Research Centre.; UNESCO.; IWA Publishing. Implementing the Water-Energy-Food-Ecosystems Nexus and Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.; Publications Office: LU, 2021.

- European Environment Agency. Nature-Based Solutions in Europe Policy, Knowledge and Practice for Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Reduction.; Publications Office: LU, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Segovia-Hernández, J.G.; Contreras-Zarazúa, G.; Ramírez-Márquez, C. Sustainable Design of Water–Energy–Food Nexus: A Literature Review. RSC Sustain. 2023, 1, 1332–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Cano, M.E.; Salmoral, G.; Rey, D.; Knox, J.W.; Graves, A.; Melo, O.; Foster, W.; Naranjo, L.; Zegarra, E.; Johnson, C.; et al. A Novel Modelling Toolkit for Unpacking the Water-Energy-Food-Environment (WEFE) Nexus of Agricultural Development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 159, 112182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRIMA Green Mediterranean PRIMA MAGAZINE. 2022.

- Pahl-Wostl, C. Governance of the Water-Energy-Food Security Nexus: A Multi-Level Coordination Challenge. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 92, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Water-Energy-Food Nexus: A New Approach in Support of Food Security and Sustainable Agriculture 2014.

- Hoolohan, C.; Larkin, A.; McLachlan, C.; Falconer, R.; Soutar, I.; Suckling, J.; Varga, L.; Haltas, I.; Druckman, A.; Lumbroso, D.; et al. Engaging Stakeholders in Research to Address Water–Energy–Food (WEF) Nexus Challenges. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1415–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, C.; Schröter, B.; Haase, D.; Brillinger, M.; Henze, J.; Herrmann, S.; Gottwald, S.; Guerrero, P.; Nicolas, C.; Matzdorf, B. Addressing Societal Challenges through Nature-Based Solutions: How Can Landscape Planning and Governance Research Contribute? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 182, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directorate General for Research and Innovation. Nature-Based Solutions: State of the Art in EU Funded Projects.; Publications Office: LU, 2020. [Google Scholar]

-

Nature-Based Solutions to Address Global Societal Challenges; Cohen-Shacham, E., Walters, G., Janzen, C., Maginnis, S., Eds.; IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature, 2016; ISBN 978-2-8317-1812-5.

- IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature IUCN Global Standard for Nature-Based Solutions: A User-Friendly Framework for the Verification, Design and Scaling up of NbS: First Edition; 1st ed.; IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, 2020; ISBN 978-2-8317-2058-6.

- Eisenberg, B; Polcher, V.; Chiesa, C. Nature Based Solutions Technical Handbook, Deliverable 5.1 for the UNaLab H2020 Project 2018.

- Ruangpan, L.; Vojinovic, Z.; Di Sabatino, S.; Leo, L.S.; Capobianco, V.; Oen, A.M.P.; McClain, M.E.; Lopez-Gunn, E. Nature-Based Solutions for Hydro-Meteorological Risk Reduction: A State-of-the-Art Review of the Research Area. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 20, 243–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddon, N.; Chausson, A.; Berry, P.; Girardin, C.A.J.; Smith, A.; Turner, B. Understanding the Value and Limits of Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change and Other Global Challenges. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2020, 375, 20190120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, J.; Miller, J.D.; Carruthers-Jones, J.; Dobel, A.J.; Carver, S.; Garbutt, A.; Hester, A.; Hails, R.; Magreehan, V.; Quinn, M. How Are Nature Based Solutions Contributing to Priority Societal Challenges Surrounding Human Well-Being in the United Kingdom: A Systematic Map Protocol. Environ. Evid. 2019, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melanidis, M.S.; Hagerman, S. Competing Narratives of Nature-Based Solutions: Leveraging the Power of Nature or Dangerous Distraction? Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 132, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coletta, V.R.; Pagano, A.; Pluchinotta, I.; Fratino, U.; Scrieciu, A.; Nanu, F.; Giordano, R. Causal Loop Diagrams for Supporting Nature Based Solutions Participatory Design and Performance Assessment. J. Environ. Manage. 2021, 280, 111668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, A.; Pluchinotta, I.; Pengal, P.; Cokan, B.; Giordano, R. Engaging Stakeholders in the Assessment of NBS Effectiveness in Flood Risk Reduction: A Participatory System Dynamics Model for Benefits and Co-Benefits Evaluation. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 690, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, A.; Gersonius, B.; Sanchez, A.; Vojinovic, Z.; Kapelan, Z. Multi-Criteria Approach for Selection of Green and Grey Infrastructure to Reduce Flood Risk and Increase CO-Benefits. Water Resour. Manag. 2018, 32, 2505–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baratella, V.; Pirelli, T.; Giordano, R.; Pagano, A.; Portoghese, I.; Bea, M.; López-Moya, E.; Di Fonzo, A.; Fabiani, S.; Vanino, S. Stakeholders Analysis and Engagement to Address Water-Ecosystems-Food Nexus Challenges in Mediterranean Environments: A Case Study in Italy: Special Issue "Co-Designing Sustainable Cropping Systems’ with Stakeholders". Ital. J. Agron. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videira, N.; Antunes, P.; Santos, R. Engaging Stakeholders in Environmental and Sustainability Decisions with Participatory System Dynamics Modeling. Environ. Model. Stakehold. Theory Methods Appl. 2017, 241–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somarakis, G.; Stagakis, S.; Chrysoulakis, N. ThinkNature / Nature-Based Solutions Handbook. [CrossRef]

- Lilli, M.A.; Nerantzaki, S.D.; Riziotis, C.; Kotronakis, M.; Efstathiou, D.; Kontakos, D.; Lymberakis, P.; Avramakis, M.; Tsakirakis, A.; Protopapadakis, K.; et al. Vision-Based Decision-Making Methodology for Riparian Forest Restoration and Flood Protection Using Nature-Based Solutions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, A; Wendling, L. Evaluating the Impact of Nature-Based Solutions: A Handbook for Practitioners. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Malamataris, D.; Pisinaras, V.; Babakos, K.; Chatzi, A.; Hatzigiannakis, E.; Kinigopoulou, V.; Hatzispiroglou, I.; Panagopoulos, A. Effects of Weed Removal Practices on Soil Organic Carbon in Apple Orchards Fields. In Proceedings of the ECWS-7 2023; MDPI, March 14 2023; p. 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakmakis, I.; Babakos, K.; Chatzi, A.; Pisinaras, V.; Brogi, C.; Bogena, H.; Dombrowski, O.; Panagopoulos, A. Precision Irrigation Scheduling through High Frequency Data Monitoring. Implementation in Apple Orchard Cultivations - Central Greece.; oral, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Maragkaki, A.; Koukianaki, E.; Lilli, M.A.; Efstathiou, D.; Nikolaidis, N.P. Optimizing the Water-Ecosystem-Food Nexus Using Nature-Based Solutions at the Basin Scale. Front. Water Rev. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Vanino, S.; Ferrari, D. Application of NBS Selection Framework in Pilots. 2023. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directorate General for Research and Innovation. Evaluating the Impact of Nature-Based Solutions: A Handbook for Practitioners.; Publications Office: LU, 2021.

- Donatti, C.I.; Andrade, A.; Cohen-Shacham, E.; Fedele, G.; Hou-Jones, X.; Robyn, B. Ensuring That Nature-Based Solutions for Climate Mitigation Address Multiple Global Challenges. One Earth 2022, 5, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morri, E.; Santolini, R. Ecosystem Services Valuation for the Sustainable Land Use Management by Nature-Based Solution (NbS) in the Common Agricultural Policy Actions: A Case Study on the Foglia River Basin (Marche Region, Italy). Land 2021, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, F.A.; Roebeling, P. Modelling Impacts of Nature-Based Solutions on Surface Water Quality: A Rapid Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Nature-Based Solutions in Agriculture: Sustainable Management and Conservation of Land, Water and Biodiversity; FAO and TNC, 2021; ISBN 978-92-5-133907-7.

- Chapman, A.; Darby, S. Evaluating Sustainable Adaptation Strategies for Vulnerable Mega-Deltas Using System Dynamics Modelling: Rice Agriculture in the Mekong Delta’s An Giang Province, Vietnam. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 559, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McWilliam, W.; Balzarova, M. The Role of Dairy Company Policies in Support of Farm Green Infrastructure in the Absence of Government Stewardship Payments. Land Use Policy 2017, 68, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdà, A.; Rodrigo-Comino, J.; Giménez-Morera, A.; Novara, A.; Pulido, M.; Kapović-Solomun, M.; Keesstra, S.D. Policies Can Help to Apply Successful Strategies to Control Soil and Water Losses. The Case of Chipped Pruned Branches (CPB) in Mediterranean Citrus Plantations. Land Use Policy 2018, 75, 734–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calliari, E.; Castellari, S.; Davis, M.; Linnerooth-Bayer, J.; Martin, J.; Mysiak, J.; Pastor, T.; Ramieri, E.; Scolobig, A.; Sterk, M.; et al. Building Climate Resilience through Nature-Based Solutions in Europe: A Review of Enabling Knowledge, Finance and Governance Frameworks. Clim. Risk Manag. 2022, 37, 100450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.; Abhold, K.; Mederake, L.; Knoblauch, D. Nature-Based Solutions in European and National Policy Frameworks. Deliverable 1.5, NATURVATION. 2018.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).