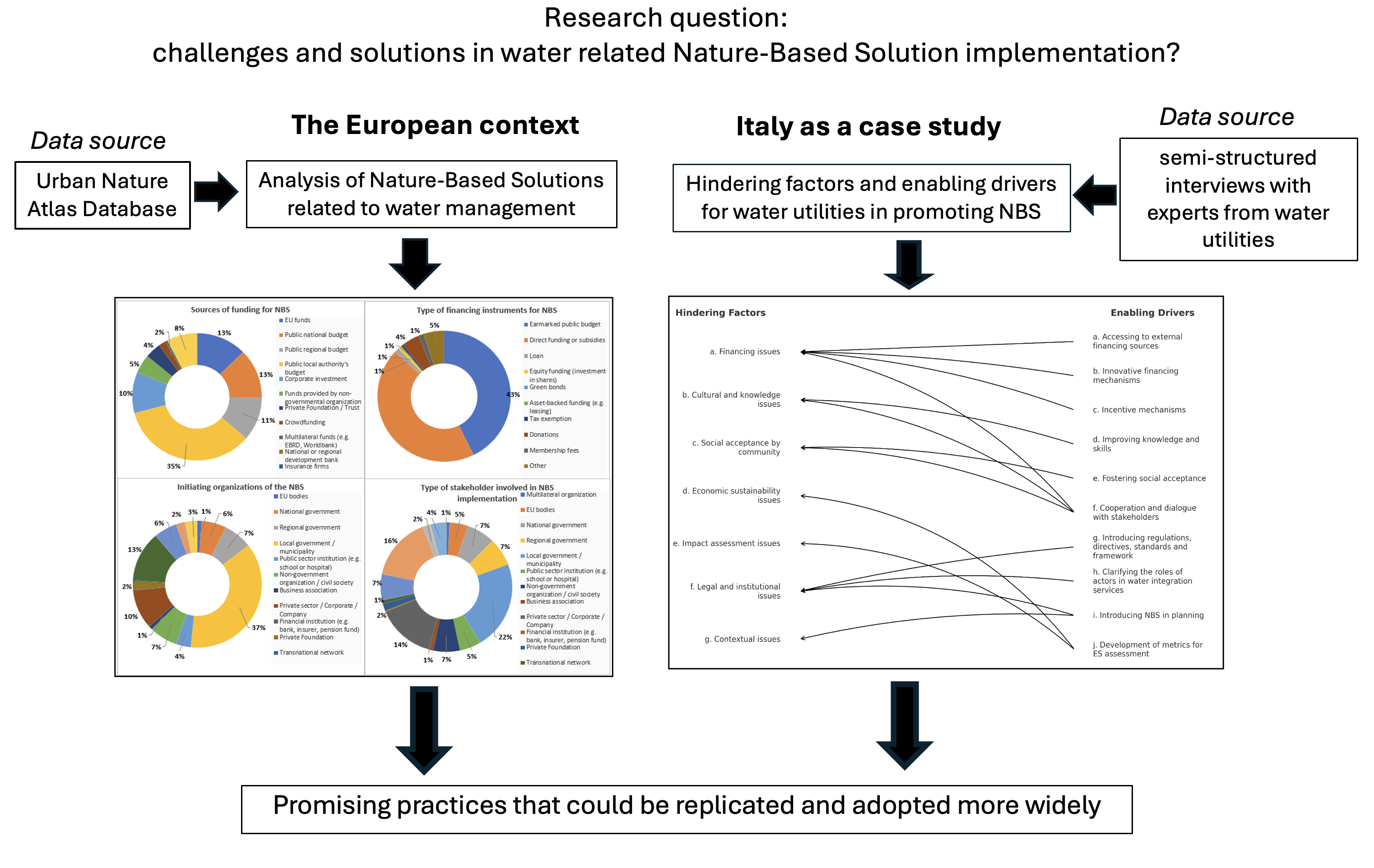

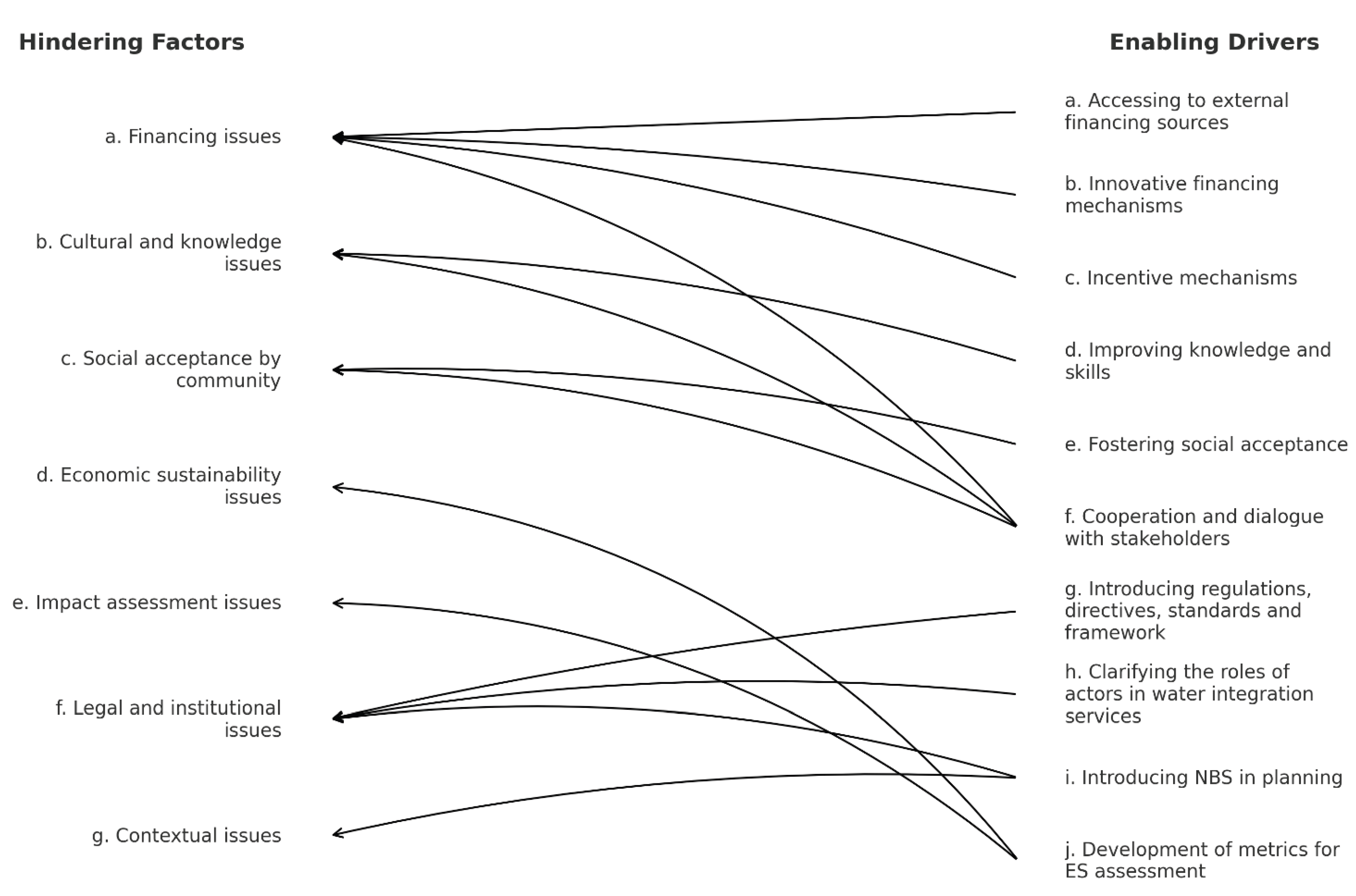

Semi-structured interviews have enabled the identification of factors that hinder the involvement of Italian water utilities in the development of NBS. At the same time, enabling drivers have been identified to encourage greater involvement from water utilities in this area. The results are presented on the following pages and summarised in Figure 1, where the rows represent the potential beneficial impacts of enabling drivers in mitigating the related hindering factors.

3.2.1. Hindering Factors

Seven hindering factors been identified as motivating Water Utilities' policies on the implementation of urban NBS.

a. Financing issues

Issues related to water tariff. Water utilities primarily rely on the water tariff paid by users to fund investments, determined by their strategic plans aligned with intervention priorities. Under regulated regime, tariff proposals are submitted to the Agency for Local Water Management (in Italian:

EGA - Ente di Governo d'Ambito) representing all municipalities insisting in an Optimal Territorial Area (In Italian:

ATO - Ambito Territoriale Ottimale)

[4], for approval, limiting autonomy in financing choices. Tariff-funded projects, legally defined by the Italian Regulatory Authority (in Italian:

ARERA – Autorità di Regolazione per Energia, Reti e Ambiente), with limited water utility flexibility to include others, as well as yearly possible increase in the water tariff (maximum 8% per year).

Respondents highlight the difficulties in covering priority intervention costs, typically focused on existing infrastructures (e.g. by promoting investments to repair/improve pipelines to reduce water losses) rather than NBS. Small operators face greater difficulty due to limited resources and stagnant tariffs (U12

[5]).

Lower water tariffs in Italy, compared to other European countries, limit resources for additional initiatives after covering priority interventions. Also, a strong reluctance to request even a modest tariff increase from citizens is registered. Moreover, justifying NBS expenses within tariffs is complex, as existing approaches prioritize conventional "end of pipeline" approaches that do not explicitly encompass NBS. Generally, dialogue with regulatory authorities is necessary for NBS inclusion (E19). However, even if these practices are successfully integrated, they often receive minimal economic recognition due to their perceived lower value. Consequently, water utilities are discouraged, as they lack sufficient institutional support and exhibit reluctance to engage in dialogue with authorities out of concern for non-recognition, preferring conventional interventions instead (U6).

Difficulty to access other financial sources. Water utility stakeholders explore public funding sources from regional, national, and European entities for projects, facing challenges in accessing them. For instance, even when public funding is available, it is directed to regions or municipalities, that generally do not have the competence to realize this kind of interventions. In such a context, water utilities need to intervene on behalf of a third party (i.e. regional or municipal public authorities) and this, according to respondents, is not effective for a massive-scale promotion of NBS projects.

Funds are often directed to regions or municipalities lacking the expertise for such projects, necessitating water utilities to intervene on their behalf, hindering large-scale NBS promotion. Capitalization is crucial for transforming assets into tariff-included investments, especially for maintenance and co-financing (U3). Respondents suggest direct funding to ATOs for easier intervention by water utilities and greater flexibility in terms of projects to be funded. On the contrary, when accessing funding calls, the intervention is generally predetermined (U3). This involves primarily political choices, potentially achieved through lobbying (U3).

Despite EU initiatives like LIFE and HORIZON, challenges exist, including accessing and meeting short-term requirements for European funding calls. PNRR funds, although promising for sustainable projects, face obstacles due to complex requirements and tight timelines.

Contrary to attributing the financial constraint to a scarcity of resources, three interviewees emphasise its "political nature" (E23). Allocation decisions by entities like Agency for Local Water Management reflect political will, impacting water utilities as managers and not resources owner. The EU allocates resources for sustainability through initiatives like LIFE, HORIZON, and INTERREG, yet small-scale operators face hurdles accessing funds. However, small-scale operators encounter obstacles in accessing and meeting the short-term requirements of European funding calls (U3). Also, these projects often cover only design costs, excluding implementation expenses, with similar challenges in accessing PNRR resources (National Recovery and Resilience Plan). Limited participation of private actors and banks further complicates funding, exacerbated by a time mismatch between tariff payback periods and debt repayment timelines. Assistance is needed for small-scale actors due to limited capacity, despite institutions like the EIB (European Investment Bank) allocating resources for sustainability objectives (U4; EIB, E21).

Maintenance costs. The interviewees stressed the increased maintenance requirements of NBS compared to grey infrastructures, posing challenges in management despite similar implementation costs. Insufficient recognition and addressing of this aspect exacerbate the issue. However, this aspect is not consistently recognized or sufficiently addressed (U3). A lack of resources and skills to sustain long-term maintenance costs, particularly in public bodies, threatens NBS efficacy.

Municipalities struggle with competing priorities, lack of specialized knowledge, inadequate cooperation, and insufficient funds, leading to project abandonment. As expressed by one respondent, “This aspect is crucial. Today, municipal projects are frequently abandoned due to neglect, stemming from insufficient funds to support ongoing costs, resulting in operational inefficacy" (U2). Some regions consider transferring maintenance responsibilities from municipalities to tariff-operating entities, necessitating tariff increases (U2). A respondent suggested that implementers should also manage the NBS for an initial period, thus incentivising them to pay more attention during the planning phase, for example avoiding inappropriate plant selections solely for aesthetic purposes (U2). Post-implementation, NBS managers must protect and maintain ecosystem services, promoting biodiversity.

Furthermore, it's crucial to consider contextual factors during NBS planning, like urban tree root damage or access challenges in remote or protected areas with specific vehicles (U2). Post-implementation, ecosystem services, such as increasing biodiversity and possible new species need to be valorised and protected (U2, U3). Incorporating investments into the balance sheet is essential for covering operational expenses, but it's challenging for utilities (U3). Typically, they include in the tariff, the costs of interventions on owned assets or those under ATO concession. Developing NBS on municipal land requires costly land purchases, an option rarely used. Alternatively, utilities can obtain concessions by municipalities, but if municipalities demand maintenance, tariff coverage for operational expenses is impossible (E16).

b. Cultural and Knowledge Issues

Lack of internal skills. The respondents emphasized a significant challenge concerning capacity building within water utilities for the development of NBS projects. Generally, smaller operators face a more pronounced "cultural divide" in multidisciplinary skills than larger operators (E23). The lack of NBS projects by water utilities is compounded by the difficulties in finding professionals with the required multidisciplinary and transversal background and skills (encompassing engineering, urban planning, ecology, and natural sciences) (E23; U3). This shortage is also attributed to the current absence of comprehensive courses in Italy, a situation that is expected to improve in the coming years (E18). Furthermore, the challenges of recruiting new colleagues are also exacerbated by the necessity to immerse them in complexities related to innovative technical aspects, administrative responsibilities, and tight deadlines (U12). Water utilities appear to be as key drivers in terms of excellent skills in water management and mentioned the growing interest in NBS solutions. However, this growing interest requires a corresponding growth in knowledge to avoid opportunistic entry into the business just to earn opportunities or greenwashing (E18).

Path dependency and lack of innovation. The development of innovative NBS in water utilities faces hurdles despite regulatory encouragement, as familiar projects are often favoured over innovative ones (E16). For many respondents the “engineering” background of projects managers in water utilities is identified as a priority issue also compared to financial constraints, with resistance to change being a significant barrier, “Money is not the issue. There is enough money there. The issue is the human brain, the human capacity” (E20) (U10).

Overcoming the lack of innovation requires a shift in skills, which is challenging due to entrenched mindsets and resistance by utilities (E20), but also for municipalities that need to think to a new concept of urban planning and the city (U13). Furthermore, some hesitations, are also dictated by the results not always clearly valuable since the planning stage (U3).

Overcoming this requires a shift in skills and mindset (E20), also from municipalities, municipalities that need to think to a new concept of urban planning and the city (U13). Furthermore, some hesitations, are also dictated by the results not always clearly valuable since the planning stage (U3). Younger employees show more interest in sustainability but face resistance and often technical staff facing challenges in managing existing infrastructures, exhibit limited availability and enthusiasm for overseeing new complex projects (E23). This engineering-centric perspective narrows the focus, overlooking broader considerations related to sustainability, ecosystem services, and potential trade-offs (U4) perpetuating a “path dependency” trend, that hinder the integration of innovative approaches in water utilities (U4). In relation to this a respondent said: “I was trained to build a great infrastructure in old style kind of wastewater treatment, and that's my training. When somebody comes to me and says that what I have been learning 20 years ago is not relevant anymore, it's very difficult to change your mind and competence. Also, engineers are talking to politicians and politicians want to be able to show that they have built something for the community instead of showing that they have recreated a natural wetland” (E20). The lack of innovation also stems from the nature of utilities as former public companies, lacking competitive market pressure to find innovative solutions (E19) (U3).

c. Social acceptance by community

Cultural barriers have emerged as significant impediments hindering the ecological transition. Communities face knowledge gaps and lack awareness regarding the impacts of NBS, leading to resistance and often unfounded prejudices (E22; U6; U7; U8). Citizens often express scepticism about the effectiveness of NBS, considering them a waste of money compared to more conventional approaches (E17). There is a prevailing belief that NBS projects are initiated and subsequently abandoned due to inadequate management, resulting in their ineffectiveness over a short period and fostering reluctance to support potential tariff increases (U11). In addition, citizens express concerns about perceived adverse impacts. Examples include worries about increased mosquito populations in wetlands or bioswales (U3). The “Sponge city“ project, incorporating small-scale interventions (i.e., infiltrating vegetation, SuDS, flowerbeds and a parallel cycle path), faced complaints over perceived reductions in parking spaces, road width, and speed limits, reflecting a NIMBY (not in my backyard) tendency raised by many interviewees. While concerns about permeable pavements in parking lots include fears of vehicle substances percolating into the subsoil, despite advances in vehicle technology and the stormwater treatment provided by permeable surfaces. Finally, several respondents reported instances of "NO" signals displayed on project announcement panels as expressions of disappointment.

d. Economic sustainability issues

The interviewees present varied perspectives on the cost-effectiveness of NBS compared to traditional grey interventions. Engineers generally perceive NBS as more expensive, prioritizing financial aspects. A respondent said: “If we had to look only at the economic side, we wouldn't even make an NBS. I am very transparent, I am an engineer, because the costs of these interventions are much more expensive than a traditional intervention”. However, NBS integration is preferred in environmental enhancement contexts or where landscape constraints exist, such as the mentioned cases of phytopurification near a castle in Brescia and interventions for rural enhancement in Val Canonica (U1; U2).

Trade-offs often arise between environmental and financial priorities. Financially sustainable utilities may prioritise environmental aspects, while the majority prioritise business profitability over environmental considerations, creating a perception of conflicting priorities (U13). Some experts argue against generalizing NBS as more expensive, citing cases where NBS have lower maintenance costs compared to traditional solutions and the cost-effectiveness profile of NBS varies on a case-by-case basis, considering territorial needs and challenges (E15; E16). For instance, while, given the same investment cost, maintenance costs for certain NBS (e.g., constructed wetlands or urban drainage systems) could be higher than those for grey solutions, in some cases this is not true.

For example, the "Castelluccio da Norcia" project reported lower operational costs for the French Reed Bed compared to conventional methods (Rizzo et al., 2018). NBS also offer benefits like land redevelopment and simpler maintenance procedures, potentially offsetting initial costs. Maintenance is easier for exposed NBS compared to buried ones, reducing cleaning frequency. NBS also often introduce simpler maintenance procedures, potentially reducing costs in the long run. Despite potential savings, cost-effectiveness varies depending on factors like land preparation and ecosystem services provision (E16).

e. Impact assessment issues

Linked to the previous barrier, an acknowledged challenge to the adoption of NBS lies in the difficulty in measuring and monetising their impacts, to highlight their potential effectiveness and efficiency, particularly when compared to traditional grey solutions. The inability to integrate these benefits into financial statements limits their appeal to investors and discourages utilities from pursuing NBS. This challenge extends to the evaluation of ecosystem services, where the absence of standardized accounting methodologies hinders comprehensive communication of the benefits of NBS. Interviews reveal that generally, only medium-large projects undergo in-depth environmental impact analyses, to ensure proper environmental and social integration within the context, often outsourced to external professionals (U14). Specific evaluation methodologies for ecosystem services are rarely employed with limitations to the assessments required by regulations, such as the calculation of the indicators required by ARERA. While some European projects, like LIFE Metro ADAPT, deploy specialised methodologies such as the BEST methodology (U6; U7; U8).

f. Legal and institutional issues

Some interviewees noted that utilities are also subject to a legislative and regulatory risk that can introduce uncertainties and hinder autonomy and operational efficiency, complicating short- and long-term planning strategies, also in relation to NBS. Bureaucratic slowness and authorisation hurdles create obstacles. An example of such hurdles mentioned by respondents was the problem in the past with hiring specialised profiles for innovative projects due to the need to use the slow public tender procedure for new assumptions. Generally, this reflects a misalignment between public bodies and private needs, impeding speed and flexibility for innovation strategies (U4). Additionally, respondents highlight the lack of regulatory space and political will for NBS. Finally, changes in municipal administration could also introduce challenges in terms of decision discontinuities.

The fragmentation of stakeholders within integrated water systems poses a significant obstacle, resulting in unclear responsibilities and hindering effective collaboration. While national legislation asserts that the management of rainwater falls under the responsibility of local administrations (i.e., municipalities), the practical implementation of this mandate lacks consistent definition. In certain cases, the management responsibility is transferred to water utilities through formal agreements, while in others, municipalities assume that water service utilities naturally handle this activity. This allocation of responsibility significantly influences the interest of water utilities in developing urban NBS (U11; U12; U3; E16).

g. Contextual Issues

Projects scale. Interviewees highlight challenges in integrating urban NBS due to limited space, high land prices, authorization complexities, and increased maintenance costs. Italian cities' historical structures further complicate integration, requiring careful urban planning and re-evaluation (U13; U14). The Italian urban structure, as a derivative of the Roman Empire, does not always allow an easy introduction of NBS or at least with simple methods of design, compatible with the times and needs of the city (i.e., construction sites that do not interrupt the urban flow, etc.) (U13; U14).

Indeed, well-planned NBS should be aligned with territorial development priorities but rather be aligned with them, taking into account population growth and the evolving needs of the area (Rubini, E22). While some recognise the potential of peripheral and rural regions due to availability of space and lower costs (E20), most acknowledge the potential of both urban and peripheral areas (U3; E16; U11; U12). They stress the importance of assessing each NBS type and its objectives without generalizing to avoid deeming projects unfeasible from the beginning (E16). However, the potential role of water utilities in urban areas will increase if these entities gain more competence in the management of urban rainwater, aligning their responsibilities with integrated services (E15). Finally, the financial dimension is also impacted by the limited size or excessive fragmentation of projects, restricting the development of robust financial instruments and hindering access to funding from institutions, which often require substantial financial commitments (U4).

Timing of the impacts. Another issue mentioned by the respondents is the timing of the impacts, since generally NBSs require long-term to produce benefits (E20). This means that the need to intervene in an emergency or quickly, favouring post-intervention actions over preventive measures, results in a preference for interventions capable of delivering immediate impacts. Moreover, the long-term benefits also create a mismatch in the case of debt repayment, as previously mentioned, with respect to access to external sources of funding.

Size and geographical location of the water utilities. The size of water utility operators emerges as a determinant factor in the implementation and efficient management of NBS. Larger entities exhibit greater investment capacity, ability to attract skilled professionals, and research capabilities, all contributing to more effective NBS implementation (IREN, U9). Interviewees emphasize regional disparities, particularly between the North and South of Italy, in terms of resource distribution, skill levels, spending capacity, and priorities. The South faces challenges such as greater sector fragmentation and lack of planning, focussing on emergency-level interventions over advanced planning, including NBS (E21; U9). The difficulty of the South is also evident in the possibility of accessing financing resources (E21). In this context, according to certain respondents the privatization of water services was deemed an ineffective strategy.

3.2.2. Enabling Drivers

Nine different categories of drivers have been found motivating the policies of Water Utilities in implementing urban NBS.

a. Accessing to external financing sources

Regarding the possibility of involving other financial sources, a couple of smaller operators express difficulties in perceiving current interest from entities other than municipalities: ‘I find it hard to think, at least for our interventions, that a municipality or, in any case, a public body that is not directly involved could finance it, certainly not a private individual, if not for aspects related to sustainability or which could constitute an appeal” (U1). Conversely, the majority of interviewees see potential for the creation of collaboration and synergies by leveraging financial resources and involving stakeholders who stand to benefit from NBS projects. There is a particular focus on potential partnerships with investment funds and real estate, emphasising the increase of property value near NBS sites (U2).

Corporations are seen as having a significant future role in NBS projects (U13), driven by interests in biomonitoring, minimizing impacts, and addressing climate-related risks like flooding that can affect their operational zones and business, such as flooding (U11). Successful dialogues between managers, production companies, and business associations have been observed for example in the ‘working tables’ organised in the APUA project (U11), leading to collaborative solutions for local territories. NBS projects, developed in partnership with water utilities, can find a space on this.

For instance, tools like the Business Improvement District can generate synergies for the redevelopment of business areas, also in collaboration with or relying on water utilities as a technical partner (E23). Additionally, some utilities have contractual agreements with corporations to develop projects aiming to offset emissions through NBS as part of neutrality plans. Moreover, regional funds for urban regeneration are accessible. An illustrative instance is the tender initiated by Regional Agency for Agricultural and Forestry Services (in Italian: ERSAF - Ente Regionale per i Servizi all'Agricoltura e alle Foreste) in the Lombardy Region, facilitating collaboration between municipalities and utilities in urban regeneration endeavours, thereby enabling the recovery of costs linked with retrofitting interventions on car parks (U11; U12).

In addition to providing financial assistance, the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR) funds present opportunities, also to address various constraints, including bureaucratic, technical, administrative, and primarily, political hurdles. These resources have facilitated the development of projects such as the "Sponge City" initiative in the Metropolitan City of Milan, with significant involvement from CAP Holding and MM Spa (see

Table S3 in Supplementary materials for more details).

However, the dynamics, time constraints, eligibility criteria, and terms mentioned above must be taken into account when applying for grants (U11; U12). Furthermore, regarding the engagement of financial institutions, respondents stress the necessity for tailored credit lines dedicated to water management, considering sector-specific characteristics and temporal mismatches between investment payback periods and the timeframes requested by banks (U11; U12; E17).

Interest from national and European banking institutions in the water sector has grown exponentially from 2018 to 2021, leading to the development of tailored financing models. An example is the EIB Italian Small Water Utilities Programme Loan, which provides financing to unlisted industrial operators. Loans have been granted to medium-sized water service operators

[6] (E19; E21). Also, European funds play a crucial role (i.e. LIFE, Horizon Europe, PRISMA, INTERREG calls) (E23; U3). NBS development may also expand the range of potential funds and funding programs to which utilities can apply. Indeed, since NBS may provide a broad range of benefits, extending beyond just water related ones, and if some of them are directly targeted by ad hoc funding opportunities (e.g. biodiversity aspects), this ultimately results in a potentially large set of funding opportunities for utilities (U3; U11).

Also, Public-Private Partnerships are highlighted as effective models for matching public and private resources, facilitating complex projects (E17). Private resources can also be mobilized through crowdfunding, sponsorship, payment for ecosystem services, (see for example the case of LIFE Brenta 2030 in

Table S3) as well as through the establishment of facilities or funds (U7). The project "Bioclima" serve as examples of successful Public-Private Partnership (

Table S3). Water utilities can allocate their own resources, often through corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives, to mitigate negative impacts of operations and demonstrate commitment to environmental and social protection. Hybrid interventions, such as planting to absorb pollution near incinerators, are documented in Sustainability Reports (U6).

b. Innovative financing mechanisms

Water utilities have the potential to influence the development of the sustainable financial market due to their inherent commitment to essential services for sustainable development, benefiting from instruments like green bonds and sustainability bonds (Ref. 2019, n.114). These attract a growing number of diverse investors, including pension funds, infrastructure funds, standard asset management funds, debt funds and offer advantages like subsidized rates and achievement of predefined sustainability indicators, thereby ensuring transparency. However, small operators face challenges due to financial constraints and high transaction costs (E21).

To address this challenges, potential alternatives for small and medium-sized industrial companies include financial pooling, the aggregation of network contracts, or the establishment of ad hoc corporate vehicles that can be secured and placed in financial market capital (U4; E21). Models like "trait enhancement" and "Collaboration Agreement" enable responsibility and risk sharing. A winning example in this sense is the Viveracqua consortium succeeding in issuing Hydrobonds and pooling resources from 14 operators in the Veneto region for innovative projects. Other major operators have also had experience with issuing green bonds, including Hera and Iren. However, the challenge lies in adapting these instruments to include NBS interventions. Furthermore, integrating NBS into water tariffs is seen as a viable strategy by respondents for the potential development of NBS by water utilities (U3), exemplified by initiatives like the LIFE Brenta 2030 project, aiming to finance NBS through the water tariff, aligning with regulations and leveraging customer resources for NBS development.

c. Incentive mechanisms

At the regulatory level, providing incentives for managers to prioritize the development of NBS projects over traditional ones could significantly accelerate the advancement of these solutions. Offering incentives to municipalities is also considered beneficial, allowing water utilities to assist them with technical interventions. The legislative framework for new constructions presents an opportunity for incentives or tax breaks, encouraging citizen involvement (E18). Incorporating NBS into urban planning is highlighted as essential for their effective valorisation. Another noteworthy aspect, acknowledged by some interviewees, involves incentivizing Responsible Project Managers (RUPs) within consulting firms and managing bodies to prioritize NBS projects. The existing bonus structure, often tied to yearly project completion numbers, may discourage the pursuit of complex or innovative projects. Introducing additional rewards or incentives for managers engaged in multi-objective projects offers a pathway to promote NBS adoption, actively involving water utilities in the process (E16; E18).

d. Improving knowledge and skills

Addressing the "cultural divide" and skill gaps that impede the testing and implementation of NBS involves disseminating knowledge through university and professional courses. Creating multidisciplinary teams is suggested to develop successful multi-objective projects since multi-skilled profiles are often challenging to find. However, effective management is crucial to facilitate discussions and reach agreements between experts (E16). In this sense, collaborations are highly effective, also to develop knowledge and ‘standard’ case studies to replicate (E16). Collaborations and the sharing of good practices play an essential role in disseminating expertise from academia to practitioners. The exchange of skills and successful pilot projects among utilities, fostering a network and collaborative approach, promote positive competition and a “nudge” for improvements and the testing of more innovative projects, including participation in European projects (E19; E23; U3). Successful interventions demonstrating the potential of NBS can influence political will, build confidence among the public sector and financiers, and overcome barriers to innovation.

e. Fostering social acceptance

Respondents note often citizens' limited awareness of NBS despite growing sustainability concerns. Most water utilities already promote education programs to highlight NBS benefits targeting citizens and students (E15). However, additional efforts are necessary, calling for systematic national campaigns (E17). Presenting NBS as tangible technological systems, emphasizing protection against vandalism and pollution, proves crucial for efficacy (U11; U12). Achieving citizen acceptance involves transparently presenting project objectives, using explanatory panels, and providing data-supported impact assessments (U10). Effective communication, facilitated by Communication Offices, demands accessible language comprehensible to all (U11, U12).

Participatory mechanisms like stakeholder participation facilitate discussions. For example, initiatives like 'water living laboratories' - territorial structures based on the concept of partnership, involving research, innovation, business, public administration and the environmental aspects – encourage inclusive decision-making, bottom-up approaches aligning solutions with territorial needs for social acceptance (U10; E22). However, fostering acceptance requires cultural shifts and behavioural changes, potentially impacting aspects like parking distance, speeds limits and travel comfort (U11; 12). Consumer guidance, influencing political and business decisions, assigns individuals a central role in societal-level leadership and transformational change (E22).

f. Cooperation and dialogue with stakeholders

Sustaining dialogue with stakeholders in the integrated water cycle, including regulatory bodies, area authorities, institutions, and municipalities, is essential for the up-scaling of NBS projects (U9). Collaborative efforts, especially with municipal support, can initiate pilot initiatives or develop more complex projects, although smaller entities face authority limitations. Partnerships and structured agreements minimize conflicts, combining experiences and resources. Encouraging research, internally and with the scientific community, ensures science-based targets and scalability evaluation.

For example, a respondent indicated that, through collaboration with reclamation consortia, a project initially focused solely on planting interventions was expanded to integrate wetlands (U10). Furthermore, partnerships and structured collaboration agreements can minimize possible conflicts in technical, legal and economic aspects, combining experiences and resources for successful results (U9; U12).

Given the innovative nature of these solutions, encouraging research is fundamental, both internally and by developing partnerships with the scientific community, universities, and research centres to test experimental projects, facilitate a science-based target, and evaluate their potential for scalability and replication (U1). Collaborating with nearby universities seems preferred by respondents, ensuring contextual knowledge crucial for project success. This synergic approach results in economic resources, experience, and growth through participation in multidisciplinary projects (U1).

Also, networking among companies, sharing good practices and experiences are frequently emphasised (E15). Furthermore, once the monetary and community value of NBS is recognized, exploring partnerships across unconventional sectors becomes feasible. For example, before COVID, some discussions emerged regarding possible public-private partnerships for energy and water efficiency interventions in buildings. This possibility was emerging, with a first decree of subsidized financing, but changing spending priorities post-COVID have negatively impacted the trajectory of these discussions (E15).

g. Introducing regulations, directives, standards and frameworks

Water utilities, as service managers, are significantly influenced by political directives in advancing NBS. While current resource allocations prioritize traditional issues, political measures such as "command and control" are identified as crucial drivers for NBS adoption (E20). Water protection plans and regional regulatory bodies (ARERA) play crucial roles, but interviewees advocate for a more forward-thinking approach at both the Agency for Local Water Management and ARERA levels. ARERA could enhance its resolutions by explicitly explaining the standard NBS cases included in the tariff. This would remove ambiguity for local authorities and water utilities, encouraging them to explore also non-traditional interventions. However, the lack of clarity also provides flexibility for local bodies to explore NBS without preclusion (E15) (E19).

Finally, regarding the possibility of ARERA adopting incentive mechanisms for such solutions, it must be acknowledged that the regulatory body operates under a system of technological neutrality and cannot prefer one technology over another, even if it is more sustainable, without an upward policy direction (E19). However, ARERA's actions in extending the scope of environmental costs to the extent possible in tariffs, including recognizing costs associated with ecosystem services, indirectly facilitate the implementation of NBS and are considered one of the most significant drivers (E19).

Additionally, the European Taxonomy of investments directs financial resources toward sustainability projects, including NBS (REF, 2021, n.195), aligning with regional and European regulations' facilitation of NBS. The role of the Taxonomy is central, because all these financial solutions would converge towards the schemes of the Taxonomy. If the entire financial world is equipped to evaluate projects according to taxonomic rules, when you are within those rules, you also see your financial support guaranteed (U4). The Taxonomy's standardised approach to project evaluation is expected to guarantee financial support within its rules (U4). Nonetheless, regulations must strike a balance, as strict interpretations often stemming from inaccurate translations of Anglo-Saxon terms of the European directive, may hinder the adoption of sustainable alternatives, exemplified by the rejection of valuable circular solutions due to stringent interpretations European guidelines on the DNSH (Do Not Significant Harm) principle (U11; E19; U12).

h. Clarifying the roles of different actors in water integration services

Legislation should address the lack of clarity in roles and skills within the water cycle. Some managers suggest assigning greater responsibilities, such as rainwater management, to utilities through formal agreements. Water utilities possess valuable knowledge and expertise within their operating territories and can often handle these solutions more efficiently and expediently compared to municipalities, which often face resource and personnel constraints. “Our experience with the region is that there are two regional reference departments, there is the municipality, there are us, there are the consortiums. Therefore, from this point of view, a request for simplification in operational terms would be optimal” remarked a manager.

This shift of responsibilities from municipalities to water utilities is actively pursued in regions like Lombardy, where managers express interest in assuming these services (U1; U2).

i. Introducing NBS in planning

To overcome context and scale challenges associated with the adoption of NBS, NBS should be introduced broadly from project origin, encompassing aspects related to building characteristics, as well as general structure and components, and not limited to spot interventions. Adopting a holistic and globally integrated approach to urban planning is essential for reimagining cities in a more harmonious and sustainable manner.

Also, many smaller NBS scale interventions can be inserted quite easily into the urban environments, such for example on the edges of the streets, in which case it is not a question of using “new” space but of redesigning that existence in a more sustainable way. For example, in Lombardy, significant market growth has been observed following the review of regulations pertaining to rainwater. A similar trend occurred with phytopurification, which gained momentum after its introduction in the water law in 1999. The Italian market experienced a notable surge from around 10 units in the 1990s to approximately 8.000 systems nowadays (E16).

l. Development of metrics for ES assessment

Interviewees underscore the relevance of developing accessible and standardized methodologies and metrics to evaluate and quantify the ecosystem services provided by NBS. This necessity is deemed critical across all sectors involved in NBS development. Standardised metrics play a pivotal role in facilitating effective communication, enhancing the credibility of NBS among stakeholders and expediting their integration into intervention planning with local authorities. Moreover, these metrics serve as vital tools in securing financial support for NBS initiatives. Furthermore, the adoption of effective metrics enables the demonstration of how NBS are inherently more sustainable, resilient, and efficient when compared to traditional "grey" solutions (E15).