Submitted:

03 July 2024

Posted:

04 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Chilean Water System and Its Particularities

2.1. Chilean Water System

2.1.1. Water Rights

2.1.2. Water User’s Associations

2.2. Institutional Framework

2.4. Relevance of Studying the Chilean Water System

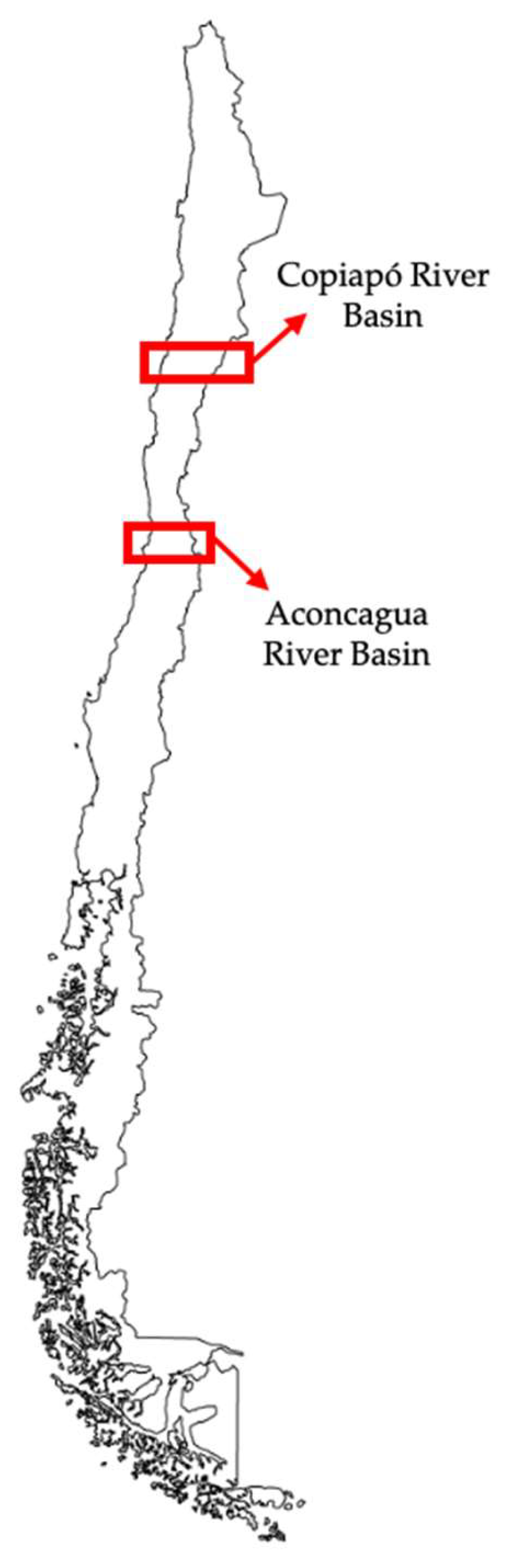

2.5. Case Studies to Analyze

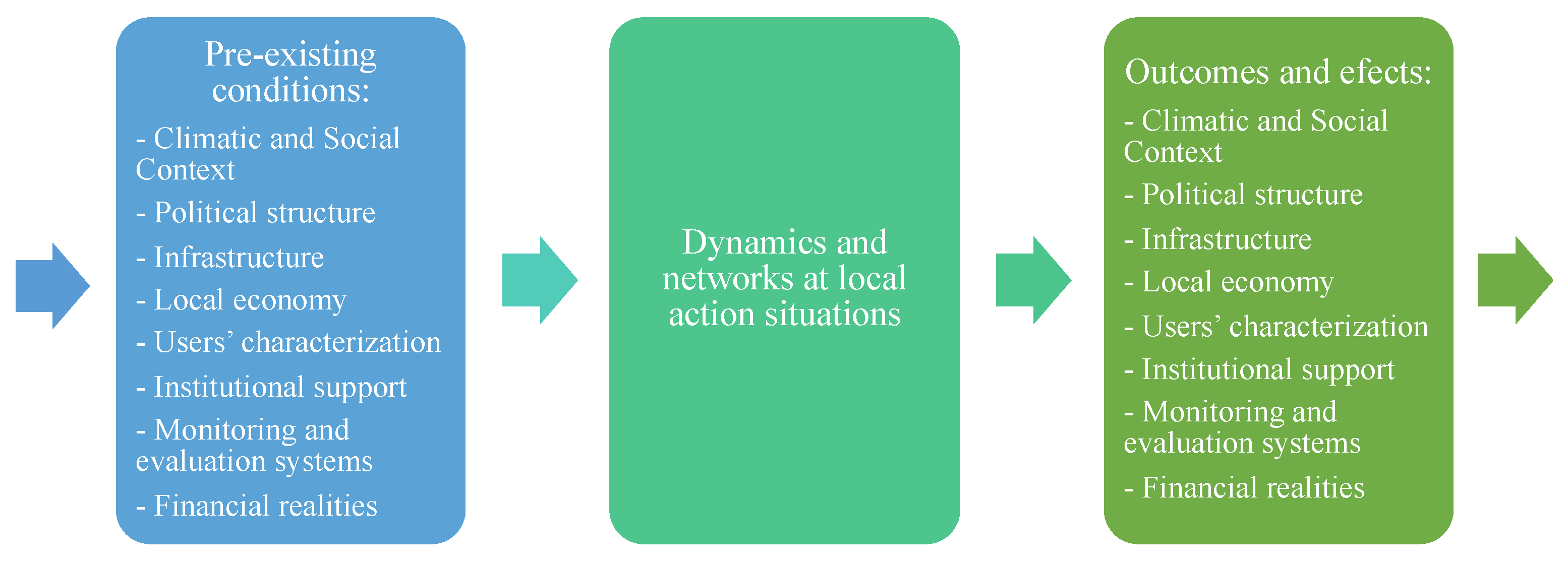

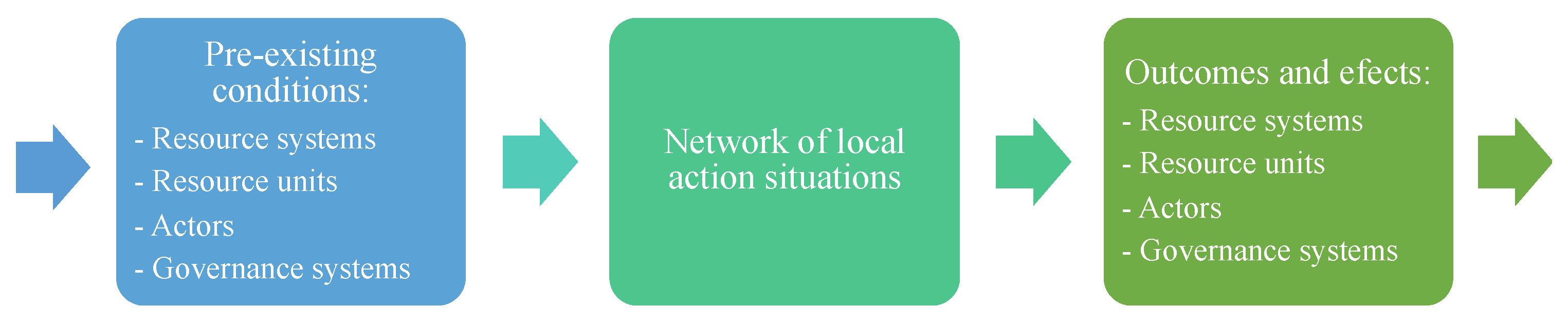

3. Method: The Combined IAD-SES Framework Adapted Towards Water Systems

- Climatic and Social Context (CSC): the unique climatic characteristics of the area, for example, if it has faced long periods of drought or variable precipitation patterns, combined with its social landscape, shapes decision-making within action situations related to water governance. These factors influence how actors perceive water, prioritize decisions, and allocate resources.

- Political structure (PS): How the system has organized, specially at the decision-making level, which affects the action arena and interactions among actors. For example, differentiating from more centralized water management, or if it has promoted a more decentralized system.

- Infrastructure (I): Existing water infrastructure, such as dams, canals, and irrigation systems, along with any limitations or lack of them. These directly affect interactions and outcomes within action situations. For example, limited infrastructure can lead to competition for scarce resources and conflict over access.

- Local Economy (LE): Refers to the economic activities and structures that are directly or indirectly dependent on water resources. The health of the local economy is intricately linked to water availability and management practices. Water scarcity or unsustainable water use can significantly impact economic productivity, livelihoods, and job security.

- Users' Characterization (UC): Local water management may involve several or few groups of water users. These may include farmers, urban residents, industrial users, environmental organizations, among others. Their interests, knowledge, and power dynamics significantly influence decision-making within action situations.

- Institutional Support (IS): Formal institutions, such as government agencies with water management mandates, and informal institutions, such as user associations and customary practices, play a critical role in facilitating or hindering collaboration within action situations. Effective institutions can provide a framework for coordination and conflict resolution, while weak or absent institutions can exacerbate tensions.

- Monitoring and Evaluation Systems (MES): Monitoring and evaluation systems assess water use, environmental impacts, and compliance with regulations. Effective systems within action situations provide data for informed decision-making, promote accountability, and ensure sustainable water management practices. Conversely, weak monitoring and evaluation systems hinder transparency and can lead to resource misuse.

- Financial Realities (FR): Financial resources available for water management, user fees, and cost-sharing mechanisms significantly shape decision-making within action situations. Limited funding can restrict investment in infrastructure improvements and constrain the ability to implement effective water management practices. User fees and cost-sharing mechanisms can incentivize efficient water use and promote collaboration, but their design and implementation can also contribute to inequities.

4. Results

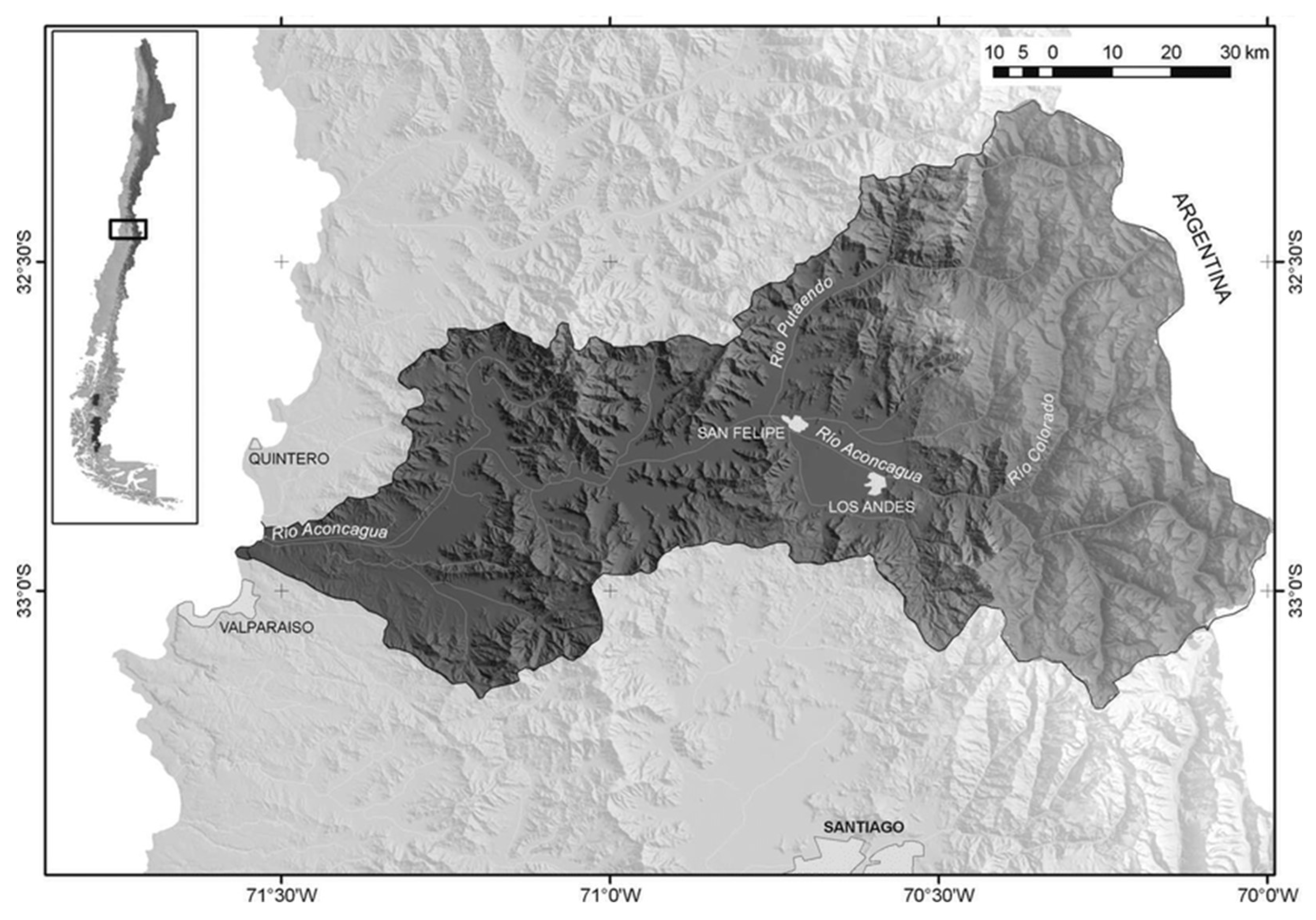

4.1. Surface Vigilance Committee Aliance at the Aconcagua Basin

4.2. Groundwater Communities in the Copiapó Basin

4.3. Lessons Learned towards Local Self Water Resources Management

5. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Ethical review and consent

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN Water; UNESCO Valuing Water. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2021. Facts and Figures; 2022.

- Sullivan, A.; White, D.D.; Hanemann, M. Designing Collaborative Governance: Insights from the Drought Contingency Planning Process for the Lower Colorado River Basin. Environ Sci Policy 2019, 91, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, A.; Saikia, P.; Giné, R.; Avello, P.; Leten, J.; Liss Lymer, B.; Schneider, K.; Ward, R. Unpacking Water Governance: A Framework for Practitioners. Water (Basel) 2020, 12, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Implementing the OECD Principles on Water Governance: Indicator Framework and Evolving Practices; OECD Publishing, Paris, 2018; ISBN 9789264292666.

- OECD Water Governance in OECD Countries: A Multi-Level Approach; OECD Publishing, 2011; ISBN 9789264119284.

- OECD Gobernabilidad Del Agua En América Latina y El Caribe : Un Enfoque Multinivel; Éditions OCDE, 2012.

- Ostrom, E. The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; 1990; ISBN 9780521405997.

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons; Cambridge university press, 2015; ISBN 1107569788.

- Poteete, A.R.; Janssen, M.A.; Ostrom, E. Working Together: Collective Action, the Commons, and Multiple Methods in Practice; 2010; ISBN 9781400835157.

- Martínez-Fernández, J.; Banos-González, I.; Esteve-Selma, M.Á. An Integral Approach to Address Socio-Ecological Systems Sustainability and Their Uncertainties. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 762, 144457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.K.; Singh, V.P. Water Resources Systems Planning and Management, Elsevier, 2023.

- Gain, A.K.; Hossain, S.; Benson, D.; Di Baldassarre, G.; Giupponi, C.; Huq, N. Social-Ecological System Approaches for Water Resources Management. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 2021, 28, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, A.; Melo, O.; Rodríguez, F.; Peñafiel, B.; Jara-Rojas, R. Governing Water Resource Allocation: Water User Association Characteristics and the Role of the State. Water 2021, Vol. 13, Page 2436 2021, 13, 2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilima, J.S.; Blakley, J.; Diaz, H.P.; Bharadwaj, L. Understanding Water Use Conflicts to Advance Collaborative Planning: Lessons Learned from Lake Diefenbaker, Canada. Water (Basel) 2021, 13, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoso, G. Water Policy in Chile, Springer, 2018.

- Ostrom, E.; Hess, C. Private and Common Property Rights. Property Law and Economics 2010, 5, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C. A Conceptual Framework for Analysing Adaptive Capacity and Multi-Level Learning Processes in Resource Governance Regimes. Global Environmental Change 2009, 19, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafton, Q.R.; Horne, J.; Wheeler, S.A. On the Marketisation of Water: Evidence from the Murray-Darling Basin, Australia. Water Resources Management 2016, 30, 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinzen-Dick, R.; Pradhan, R. Legal Pluralism and Dynamic Property Rights, 2002.

- Jara, J.; López, M.A.; Salgado, L.; Melo, Ó. Administration and Management of Irrigation Water in 24 User Organizations in Chile. Chil J Agric Res 2009, 69, 224–234. [Google Scholar]

- Peña, H. Integrated Water Resources Management in Chile: Advances and Challenges. In Water Policy in Chile; Donoso, G., Ed.; Springer, 2018; pp. 197–207.

- Donoso, G.; Lictevout, E.; Rinaudo, J.D. Groundwater Management Lessons from Chile. Sustainable Groundwater Management. Global Issues in Water Policy 2020, 24, 481–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoso, G. Water Markets: Case Study of Chile’s 1981 Water Code. Cienc Investig Agrar 2006, 33, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoso, G. Overall Assessment of Chile’s Water Policy and Its Challenges. In Water Policy in Chile; 2018; pp. 209–219.

- Fuster, R. Diagnóstico Nacional de Organizaciones de Usuarios, 2018.

- Bauer, C.J. Water Conflicts and Entrenched Governance Problems in Chile’s Market Model. Water Alternatives 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hearne, R.R.; Donoso, G. Water Institutional Reforms in Chile. Water Policy 2005, 7, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santibáñez, F. El Cambio Climático y Los Recursos Hídricos de Chile, Santiago, 2016.

- DIRECOM Comercio Exterior de Chile Enero-Septiembre 2018; 2018.

- McPhee, J. Hydrological Setting. In Water Policy in Chile; Donoso, G., Ed.; Springler, 2018; pp. 13–23.

- World Bank Diagnóstico de La Gestión de Los Recursos Hídricos. Chile. Departamento del Medio Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoso, G.; Vicuña, S. Pobres de Agua. Radiografía Del Agua Rural de Chile: Visualización de Un Problema Oculto. Santiago, Chile. Fundación Amulén, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- CR2 Informe a La Nación: La Megasequía En Chile La Megasequía 2010-2019: Una Lección Para El Futuro; 2019.

- World Bank El Agua En Chile: Elemento de Desarrollo y Resiliencia ; Washington, DC. 2021.

- Banco Central de Chile Base de Datos Estadísticos (BDE) 2021.

- World Bank Estudio Para El Mejoramiento Del Marco Institucional Para La Gestión Del Agua. Chile. Departamento del Medio Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fuster, R. El Estado de La Gestión Integrada de Los Recursos Hídricos En Chile: Estudio de Casos En La Cuenca Del Río Limarí. Tesis Doctoral, 2013.

- Ugarte, P. Derecho de Aprovechamiento de Aguas: Análisis Histórico, Extensión y Alcance En La Legislación Vigente., Universidad de Chile: Santiago, 2003.

- Budds, J. Water, Power, and the Production of Neoliberalism in Chile, 1973–2005. Environ Plan D 2013, 31, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, M.; Fragkou, M.C.; Calderón, M. Water Policy and Management in Chile. In Encyclopedia of Water; Wiley, 2019; pp. 1–11.

- Donoso, G.; Montero, J.P.; Vicuña, S. Análisis de Los Mercados de Derechos de Aprovechamiento de Agua En Las Cuencas Del Maipo y El Sistema Paloma En Chile: Efectos de La Variabilidad de La Oferta Hídrica y de Los Costos de Transacción. Revista Derecho Administrativo Económico 2001, 6, 367–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoso, G.; Cancino, J.; Melo, Ó.; Rodríguez, C.; Contreras, H. Análisis Del Mercado Del Agua de Riego En Chile: Una Revisión Crítica a Través Del Caso de La Región de Valparaíso 2010.

- Donoso, G. Water Policy in Chile. In Water Policy in Chile; 2018 ISBN 978-3-319-76701-7.

- Alevy, J.E.; Cristi, O.; Melo, O. Right-to-Choose Auctions: A Field Study of Water Markets in the Limari Valley of Chile. Agric Resour Econ Rev 2010, 39, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearne, R.R. Water Markets. In Water Policy in Chile; 2018; pp. 117–127.

- Hearne, R.R.; Donoso, G. Water Markets in Chile: Are They Meeting Needs? In Easter K., Huang Q. (eds) Water Markets for the 21st Century. Global Issues in Water Policy, vol 11. Springer, Dordrecht; 2014.

- Peña, H.; Brown, E.; Ahumada, G.; Berroeta, C.; Carvallo, J.; Contreras, M.; Cristi, O.; Espíldora, B.; Gómez, R.; Muñoz, J.F.; et al. Temas Prioritarios Para Una Política Nacional de Recursos Hídricos. Comisión de Aguas, Instituto de Ingenieros de Chile, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, D. Usos y Derechos Consuetudinarios de Aguas. Su Reconocimiento, Subsistencia y Ajuste. Thompson Reuters, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, D.; Godoy-Faúndez, A.; Lillo, M.; Alvez, A.; Delgado, V.; Gonzalo-Martín, C.; Menasalvas, E.; Costumero, R.; García-Pedrero, Á. Legal Disputes as a Proxy for Regional Conflicts over Water Rights in Chile. J Hydrol (Amst) 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, E.; Donoso, G.; Camus, P. Water Conflicts in Chile: Have We Learned Anything from Colonial Times? Sustainability 2023, 15, 14205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoso, G. Integrated Water Management in Chile. In Integrated Water Resources Management in the 21st Century: Revisiting the paradigm (Ch. 12); 2014.

- Jaque, S. Reforma Al Código De Aguas Chileno: Nuevas Reglas Sobre Propiedad y Ejercicio de Los Derechos de Aprovechamiento de Aguas. Actualidad Jurídica (1578-956X) 2022, 26. [Google Scholar]

- DGA Atlas Del Agua. 2016.

- Budds, J. Securing the Market: Water Security and the Internal Contradictions of Chile’s Water Code. Geoforum 2020, 113, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bown, F.; Rivera, A.; Acuña, C. Recent Glacier Variations at the Aconcagua Basin, Central Chilean Andes. Ann Glaciol 2008, 48, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaudo, J.D.; Donoso, G. State, Market or Community Failure? Untangling the Determinants of Groundwater Depletion in Copiapó (Chile). Int J Water Resour Dev 2019, 35, 283–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DICTUC Analisis Integrado de Gestion En Cuenca Del Rio Copiapo, Chile, Informe Final Tomo 1. 2010.

- Cole, D.H.; Epstein, G.; McGinnis, M.D. The Utility of Combining the IAD and SES Frameworks. Int J Commons 2019, 13, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, M.D.; Ostrom, E. Social-Ecological System Framework: Initial Changes and Continuing Challenges. Ecology and Society 2014, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE Encuesta Suplementaria de Ingresos (ESI) Síntesis de Resultados 2021 Región de Valparaíso. 2021.

- GORE Economía Región de Valparaíso, Chile; Valparaíso. 2020.

- Aldunce, P.; Araya, D.; Sapiain, R.; Ramos, I.; Lillo, G.; Urquiza, A.; Garreaud, R. Local Perception of Drought Impacts in a Changing Climate: The Mega-Drought in Central Chile. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrain, S.; Poo, P. Conflictos Por El Agua En Chile: Entre Los Derechos Humanos y Las Reglas Del Mercado; Larraín, S., Poo, P., Eds.; Chile Sustentable, 2010; ISBN 9789567889426.

- CNR Diagnóstico Para Desarrollar Plan de Riego En Cuenca de Aconcagua. 2016.

- DGA Plan Estratégico de Gestión Hídrica En La Cuenca Del Aconcagua. 2020.

- Jorquera, L. Gestión Del Agua En La Cuenca Del Aconcagua. Vertiente 2020, 402–447. [Google Scholar]

- DGA (Dirección General de Aguas) Acuerdo de Redistribución de Las Aguas y Medidas Por Declaración de Zona de Escasez Hídrica En La Cuenca Del Río Aconcagua; Dirección General de Aguas, DGA del Ministerio de Obras Públicas de Chile. 2019.

- DGA (Dirección General de Aguas) Actas Del Comité Ejecutivo y Comité Técnico Del Plan Aconcagua. Available online: https://dga.mop.gob.cl/Paginas/plan_aconcagua.aspx (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- PUC Informe Trimestral de Avance N°1, Programa: “Capacitación y Apoyo a Comunidades de Aguas Subterráneas En El Valle de Copiapó, Región de Atacama”; 2012.

- SITAC Levantamiento Catastro de Usuarios de Aguas Del Valle Del Río Copiapó y Sus Afluentes III Región de Atacama. 2008.

- JVRC Lautaro 2.0. Junta de Vigilancia Río Copiapó (JVRC), 2022.

- Blanco, E.; Donoso, G. Drivers for Collective Groundwater Management: The Case of Copiapó, Chile. In Global Water Security Issues (GWSI) 2020 Theme: The role of sound groundwater resources management and governance to achieve water security.; Choi, S.H., Shin, E., Makarigakis, A.K., Sohn, O., Clench, C., Trudeau, M., Eds.; UNESCO, International Centre for Water Security and Sustainable Management, 2021; pp. 59–75 ISBN 978-92-3-100468-1.

- PUC Informe Final Programa: “Capacitación y Apoyo a Comunidades de Aguas Subterráneas En El Valle de Copiapó, Región de Atacama”; 2014.

- Rojas, C. Autogestión y Autorregulación Regulada de Las Aguas: Organizaciones de Usuario de Aguas (OUA) y Juntas de Vigilancia de Ríos. Ius et Praxis 2014, 20, 123–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrigo, G. Propuesta Metodológica Para La Organización y Funcionamiento de Comunidades de Aguas Subterráneas, 2019.

- Vemaps Outline Map of Chile. Available online: https://vemaps.com/chile/cl-01#google_vignette (accessed on 25 June 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).