1. Introduction

During the past decades, governance of natural resources has emerged as a critical issue, driven by the challenges posed by climate change and urban growth [

1,

2,

3]. With governments often facing limitations in capacity and budget to safeguard resources effectively, the private sector has increasingly participated in shaping policies and initiatives, while civil society advocates for more active involvement in decision-making concerning natural resource conservation and utilization [

4,

5]. Amid this shifting landscape, the development of market-based instruments for managing and valuing of ecosystem services has gained prominence as an alternative or complement to government-led actions, influencing environmental agendas at the state and agency level [

6,

7,

8]. Specifically, payment for ecosystem services (PES) schemes [

9,

10,

11], and their dominant variations such as payments for watershed services (PWS) have experienced rapid proliferation over the past two decades [

12,

13,

14,

15]. These programs aim to tackle water security concerns through voluntary mechanisms, where government or water users invest in nature-based solutions (NbS) within watersheds [

16]. To our best knowledge, as of 2025, the number of such PWS programs worldwide reached 881, with a cumulative transaction value of approximately USD 49 billion [

17]. These numbers show how investment in NbS for water security via PWS and other instrument has doubled over the past decade, if we considered around 387 initiatives as of 2018 with a total investment of USD 24.7 billion [

18].

Latin America has stood out as a global hotspot for PWS [

15,

19] as it has been a pioneer and innovator in developing NbS programs for source water protection, creating enabling policies, institutions, and implementation approaches [

20]. Due to the reliance of its cities on highland and mountain forests for freshwater and energy production, the region is particularly vulnerable to watershed degradation, which poses risks to water resources and other vital goods and services derived from these areas [

21,

22]. Water Funds have emerged as one of the most widely promoted PWS schemes in the region to secure water provision for some of Latin America’s largest cities [

5,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Broadly defined, a Water Fund is a replicable financial and governance model that establishes a link between downstream beneficiaries and upstream land stewards through a sustainable institutional, management and financing mechanism [

27,

28]. Water Funds share three central components: a funding component to collect resources and ensure the mechanism’s financial stability, a governance component responsible for making decisions regarding watershed conservation strategies, and a management component focused on implementing field activities [

28].

Since the establishment of the first Water Fund in the city of Quito in 2000, there has been an intention by different actors to replicate these mechanisms throughout the region. Consequently, the Latin American Water Funds Partnership (LAWFP) emerged in 2011, promoted by The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and other private and public actors, leading to the creation of 26 Water Funds in the region, in particular in Colombia, Ecuador and Brazil. Water Funds, as a subset of PWS have been primarily studied from an economic theory perspective, viewing them as a market solution to the problem of managing water-related ecosystem services as externalities. As a result, several studies have focused on evaluating these schemes based on efficiency, additionality, and conditionality criteria [

15,

29,

30]. However, empirical research on the impacts of Water Funds as institutions that contribute to reshape watershed governance, including actor interactions, roles and responsibilities, and performance of environmental directives, remains limited [

25,

28,

31]. Furthermore, there are few studies comparatively assessing these mechanisms at a national level [

24]. Studying Water Funds from an institutional perspective can provide insights into their impacts on the governance of water ecosystem services, and it can contribute to a deeper understanding of the fundamental challenges related to natural resource management in the region and aid in designing more effective institutions to achieve sustainable development goals [

32].

This study conducts an institutional analysis of Water Funds in Colombia, which are part of the LAWFP. The objective is to understand the key institutional factors enabling and driving the success of Water Funds in Colombia, to grasp their role on development trajectories of Water Funds and understand why some Funds remain active while others dissolve. To achieve this, the study employs Ostrom’s Institutional Analysis and Development Framework (IAD), widely used for examining common-pool resource institutions [

33]. This research argues that the continuity of Water Funds in Colombia depends on the institutional strength of participating stakeholders, the presence of trust among them—often rooted in prior collaboration—and the degree to which environmental authorities perceive the funds as allies rather than competitors. The governance of these funds is weakened when stakeholders lack a consistent agenda, leading to trust erosion and eventual dissolution. The contributions of this paper are twofold: first, we contribute to the literature on water governance by analyzing the factors that influence the continuity of Water Funds as innovative mechanisms for collective action and resource management. Most importantly, we delve into the institutional configuration of specific Water Funds in Colombia, one of the most biodiverse countries in the world, where water ecosystems are vital for sustaining both human populations and the country’s rich biodiversity.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 outlines the methodology employed, encompassing detailed descriptions of the case studies, the research approach based on concepts of institutions and governance, and the analysis of common-pool resource institutions.

Section 3 presents the results derived from the institutional analysis of Water Funds in Colombia. A discussion of the main findings is covered in

Section 4, while the study’s conclusions are placed in

Section 5.

2. Materials and Methods

This section describes the case studies addressed and the methodological approaches adopted for the aims of the research.

2.1. Case Studies

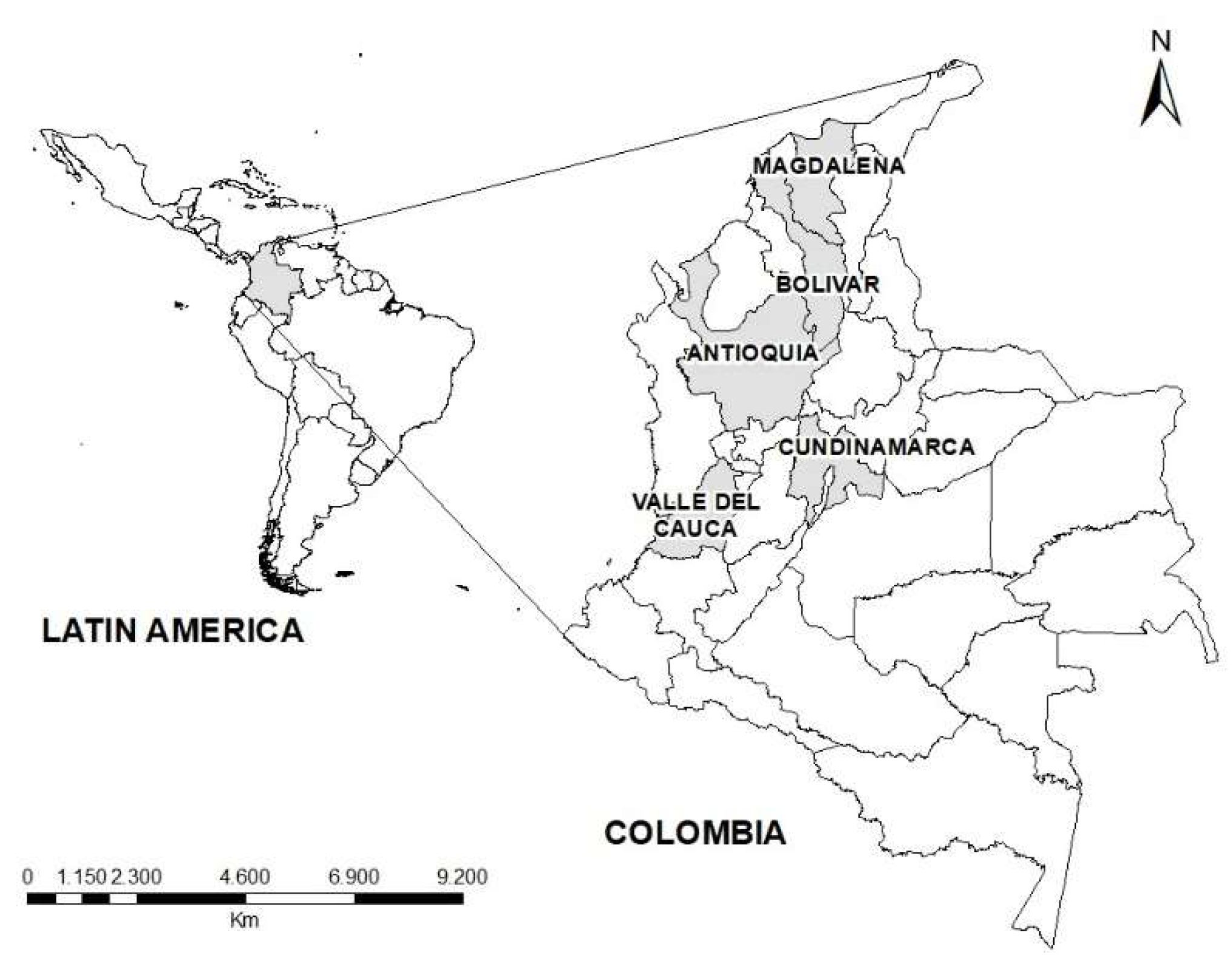

The study focused on the specific case of Colombia, where to date of this study, five Water Funds belonging to the LAWFP have been launched in the departments of Antioquia, Bolivar, Cundinamarca, Magdalena, and Valle del Cauca (

Figure 1).

The first Water Fund established and named as such in Colombia, known as Agua Somos, was introduced in 2009. This fund’s primary objective was to safeguard water quality in Bogotá, the nation’s capital, particularly in the face of climate change and mounting pressures on the natural areas surrounding the city [

34]. As LAWFP grew and witnessed the launch of additional Water Funds across the region, new funds emerged in Colombia, while existing initiatives that align with the Water Fund concept also joined the partnership. Such were the cases of the Fundación Fondo Agua por la Vida y la Sostenibilidad (FAVS) in Valle del Cauca and Cuenca Verde in Antioquia. FAVS, created as an independent organization, has been engaged in watershed protection activities funded by the sugar cane sector and executed by its union, Asocaña, since the early 1990s [

35]. On the other hand, Cuenca Verde originated from joint efforts by TNC and the Medellín water utility (Empresas Públicas de Medellín) with the aim of ensuring the implementation of sustainable land practices in watersheds that supply water to the city of Medellín [

36]. Additionally, two more recent funds, Cartagena and Santa Marta, received funding and technical support from the LAWFP to conduct viability studies before being launched.

Table 1 provides an overview of the Colombian Water Funds analyzed within this research.

2.2. Institutional Framework for the Analysis of Water Funds

To analyze Water Funds from an institutional perspective, we draw upon the IAD proposed by Ostrom [

33], which has been widely employed in research aimed at studying management of common-pool resources including water resources (e.g., [

37]). For the scope of this research, we have integrated the IAD framework with insights from other authors’ work on the institutional analysis of PES schemes [

31,

38,

39,

40]. This complementary work connects the IAD with PWS literature, and operationalizes some of the components of the original IAD framework via guiding questions and analytical variables.

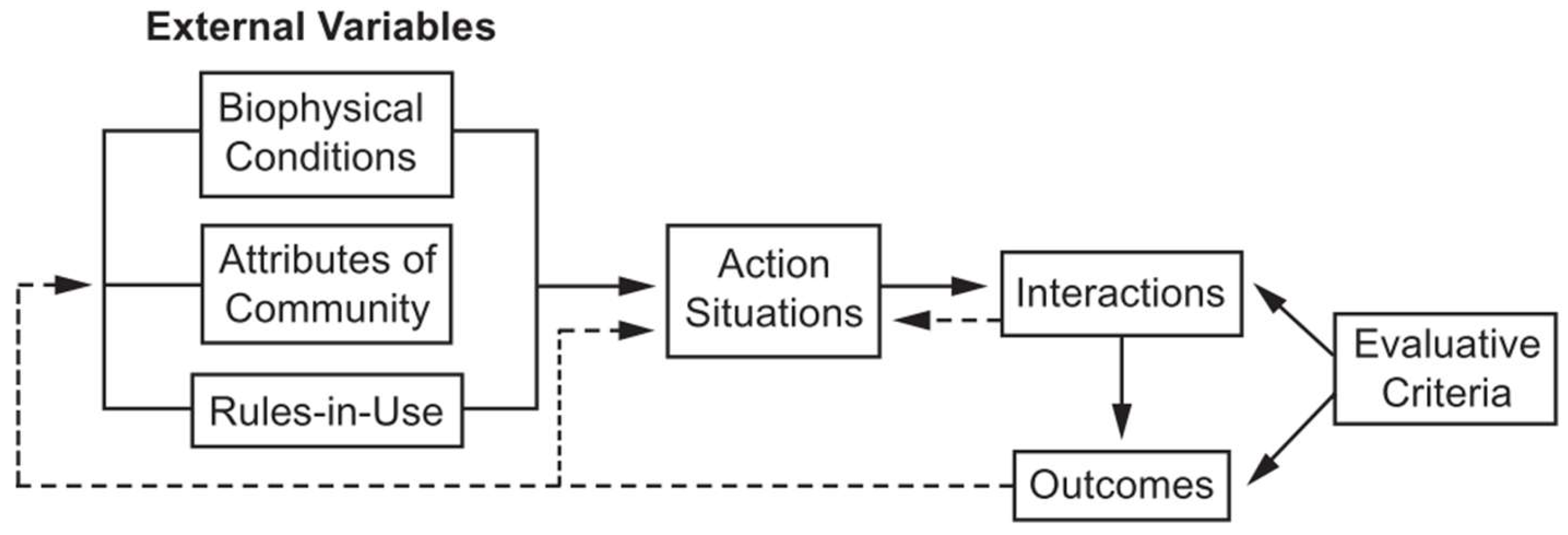

The IAD framework helps highlighting key variables of institutional, technical, and participatory aspects of common-pool resource problems and their resulting effects (

Figure 2). In this sense, the framework should represent the main structural variables that are present to some extent in all institutional arrangements, but whose values differ between institutional arrangements [

33].

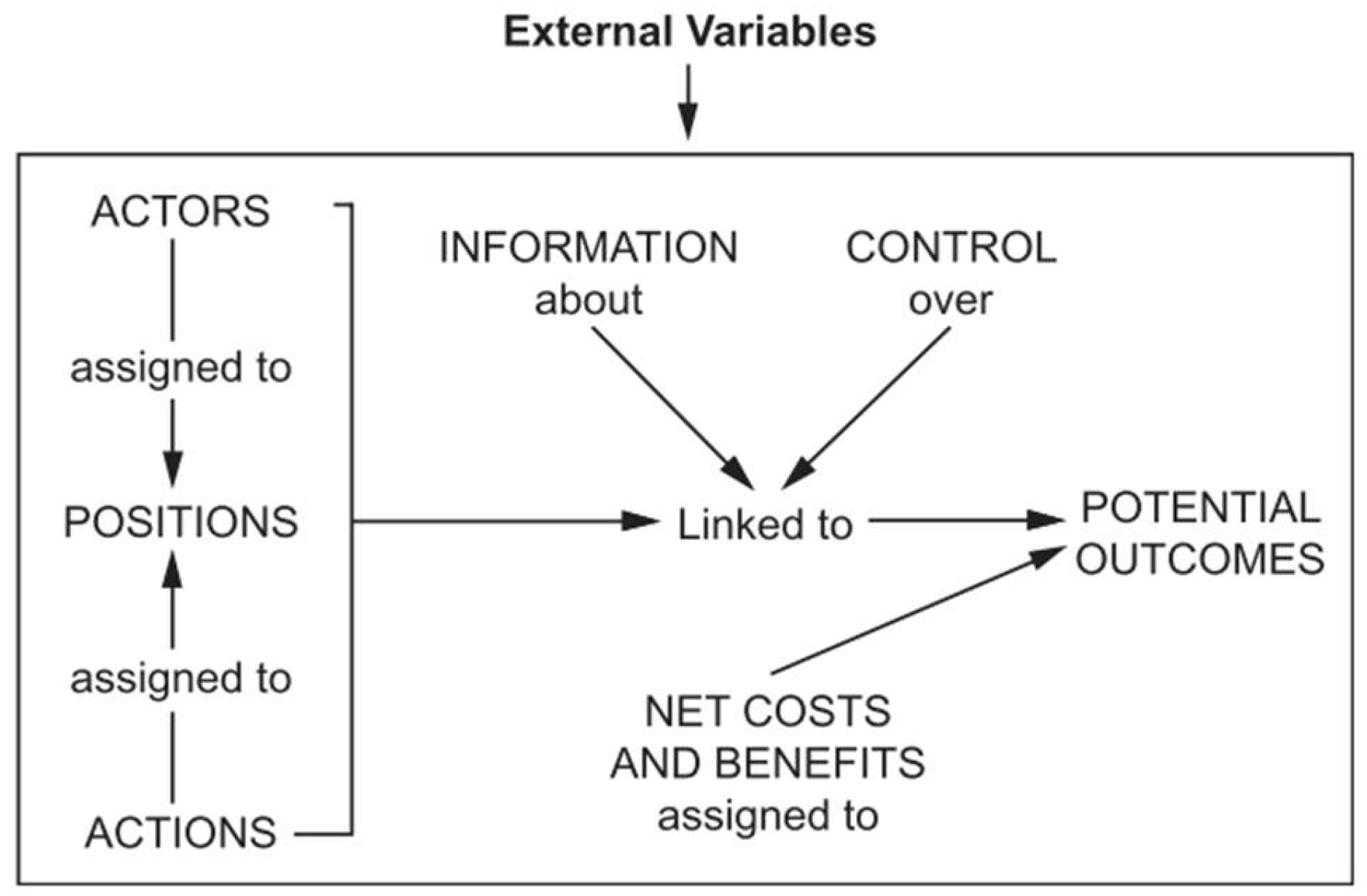

At the heart of the IAD framework there is the concept of action situation, which refers to asocial space of a minimum of two actors, phasing a series of potential actions that produce outcomes [

41]. Actions situations have become a central unit of analysis in social-ecological systems research and are shaped by key variables such as

i) the kind of actors involved in them, which at the same time belong to a community with certain attributes;

ii) the rules that allow specific choices and determines actors participation,

iii) the outcomes from those action situations, which feedback in a loop [

42] (

Figure 3). For this study, our unit of analysis is the rule-making process within a Water Fund (i.e., the action situation of governing a Water Fund), to understand why some Water Funds remained active while others dissolved. Selected categories of the IAD framework and the action situation structure were broken down into guiding questions and analytical variables for data collection purposes (

Table 2).

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

The data for this study was collected from two primary sources. The first source involved a comprehensive three-step literature review on Water Funds in Colombia, encompassing scientific and grey sources (e.g., reports, non-published studies, and press releases). In the initial step, we conducted a general search within the scientific literature on water funds in Latin America using the search string “Water fund* AND Latin America.” The search was conducted on Web of Science, a university library resource (SOEG at The Danish Royal Library), and Google Scholar. Subsequently, we explored the LAWFP website to access grey literature, including summaries, strategic plans, technical documents, press releases, official videos, and other available websites for each Water Fund. Additionally, we consulted relevant sections on the TNC website, namely “Toolbox,” “Regions,” and “Library,” to gather related information on Latin American Water Funds. The final step involved specific searches for scientific and grey literature on each of the five selected Water Funds using Google Scholar and Google, both in English and Spanish. This review encompassed web pages of municipalities, companies, LAWFP partners, other organizations, press releases, and various other documents.

The second data source comprised qualitative interviews with relevant actors associated with each Colombian Water Fund. In total, 15 semi-structured interviews - i.e., three for each Water Fund - were conducted in Spanish via Zoom between May and July 2021. The interview structure and analysis were based on the analytical dimensions and guiding questions presented in

Section 2. The interviews were fully recorded with the consent of the interviewees and subsequently transcribed. The stakeholders interviewed included the director and at least one developer from each Water Fund, as well as additional actors occupying various positions and roles, such as board members, representatives of landowners, and environmental authorities (

Table 3).

The interviews were analyzed from a qualitative perspective to explore the main categories of the IAD framework shaping the action situation of rule-making. To achieve this, an ‘editing approach’ [

43] was adopted, using the five analyzed categories of the framework as guiding themes to conduct a thematic analysis [

44,

45,

46] of the interview data. Following the six-step approach defined by Lincoln & Guba [

47] and revised by Braun & Clarke [

44], we reviewed interviews and deductively identified text segments and patterns/themes for each category, finally making interpretative statements about them [

48]. Throughout the analysis, information collected during the interviews was summarized and organized into matrixes to compare findings across the targeted case studies, finally distilling general considerations and discussing them vis-à-vis existing literature.

3. Results

The status of continuity and dissolution of the Water Funds in Colombia varies across the different schemes. Three out of the five Funds were either in a stand-by or a dissolution phase, namely Agua Somos, Cartagena, and Santa Marta y Ciénaga water funds, while Cuenca Verde and FAVS were currently operational. This section examines the Water Funds rule-making process considering the analytical categories that influence it according to the IAD framework. Results show how institutional strength, stakeholder trust, and collaboration with environmental authorities affects the different actors interactions with implications for the Water Funds continuity.

3.1. Actors and Positions

We identified three recurring types of actors participating from the rule-making processes within the Water Funds, as partners or financiers: i) private sector organizations, ii) non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and iii) public organizations, including city water utilities and environmental authorities (

Table 4). A fourth type of actor, iv) landowners, was found only on the board of directors of FAVS, having limited representation in the Funds’ decision-making bodies across cases. Private sector organizations, such as beverage companies and other large water users, as well as NGOs, primarily contribute to the Water Funds through donations or resources for seed capital or specific conservation projects. Notable examples include TNC and Bavaria’s involvement in supporting Agua Somos and Postobon and Nutresa’s contributions to Cuenca Verde. Public services companies, specifically city water utilities like Medellín’s public service company (EPM) and Bogota Aqueduct and Sewerage Company (EAAB) also play a significant role in financing the Water Funds. Additionally, regional environmental authorities serve as technical supervisors, validators and, in certain cases, as contributors of the Water Funds. For example, FAVS benefits from co-financing conservation projects facilitated by the regional environmental authorities. Across the various Water Funds, the roles and relationships of the different actors can significantly vary. For instance, the interaction between FAVS and the environmental authority of its jurisdiction, Valle del Cauca Regional Autonomous Corporation (CVC), differs from that of Santa Marta y Ciénaga and Cartagena water funds with their respective environmental authorities. In the case of FAVS, CVC is actively engaged as a partner, providing co-financing for conservation initiatives and validating the Water Fund’s presence in the watersheds. On the other hand, Santa Marta y Ciénaga Water Fund did not establish a significant partnership with the local environmental authority (CORPAMAG) beyond signing the agreement for its establishment, with no subsequent financial contributions from the environmental authority. A similar situation can be described regarding city water utilities and Water Funds, where the size and frequency of contributions vary considerably. For instance, EPM’s participation is notable in Cuenca Verde, while EAAB’s support is not prominent nor stable in Agua Somos, across different Water Funds.

3.2. Attributes of Community

Actors’ characteristics vary considerably across Water Funds. In the case of Cuenca Verde, the Fund was created as an initiative of EPM with the support of TNC and some private companies. However, the Fund grounded, especially at the beginning, on the experience of EPM, which had already implemented conservation projects in its area of influence for several years. Similarly for the case of FAVS, the fund is working with organizations existing in the watersheds for more than 20 years, established through processes of acceptance and recognition that are often complex and require time. In the cases of Cartagena and Santa Marta, the Funds were born from the initiative of some members of the LAWFP, who provide the seed capital for the feasibility studies and launching of the Funds, and engaged with private foundations, the water utilities and environmental authorities to constitute these Funds decision-making bodies. For the case of the Santa Marta Water Fun, public institutions and the environmental authority did not provide the resources to finance the fund over time. The municipalities of Santa Marta and Ciénaga and the Magdalena Government, administered by leaders of different political parties, did not show a genuine willingness to invest in the scheme. The investment budgets of these institutions for environmental projects were invested in other activities. In the case of the Cartagena Water Fund, the institutional instability of the city started eroding the communication channels and the relationships of trust between the Fund’s actors, especially between the public and private. Between the five years after the launch of the Water Fund and the time of this study, the city of Cartagena has had four different Mayors. At the same time, Cartagena’s Water Utility has undergone continuous restructuring processes, which has caused an intermittent involvement of these public actors in the funding and operation of the Water Fund. As an ultimate consequence, it has not been possible to define long-term commitments. This situation provoked skepticism within the private actors regarding their potential investments in the Fund, generating a progressive abandonment of the scheme to develop their water conservation activities independently. With regards to Agua Somos, Bogotá’s public administration suffered political instability during the 2013-2017 period, resulting in the mayor being removed from office. After that, the aqueduct and sewerage company also had a series of internal institutional problems, causing the Water Fund not to have a constant interlocutor with these critical partners. Funding and support from these actors were reduced, and the contributions of the private actors were not enough to support the scheme’s operation.

The Water Funds in Colombia exhibit varying degrees of integration with other institutions involved in watershed management. For example, FAVS has developed a solid relationship with CVC in the Cauca Valley, reaching roles coordination for different projects in the area. Similarly, Cuenca Verde has engaged with public sector bodies, including the environmental authority CORNARE, achieving varying levels of success in coordination. The Fund acts in compliance with the environmental directives and the authority, in turn, sees the fund as a powerful partner to strengthen watershed governance. On the other hand, Agua Somos and the Santa Marta y Cartagena water fund have not achieved significant engagement with environmental authorities, municipalities, and local public authorities. Their interactions primarily revolve around private organizations.

3.3. Rules-in-Use

One key aspect that varies across the Funds is the institutional arrangement, impacting their constitutive processes and its rule-making (

Table 5). Cuenca Verde was created as an independent corporation, whereas FAVS was established as a foundation with participation from Asocaña, the Water Users Associations, TNC, and other private companies, built upon Asocaña’s previous projects with the Water Users Associations dating back to the 1990s. Agua Somos was initiated as a joint effort of the Bogota Aqueduct and Sewerage Company (EAAB), TNC, Bavaria brewing company, and the foundation Fondo Patrimonio Natural. The Cartagena Water Fund was established through a five-year framework association agreement signed by eight public and private stakeholders including the local water utility, TNC, the district of Cartagena, the regional environmental authority (Cardique), and three private foundations, with the Canal del Dique Foundation (FCD) chosen as the Fund’s operator and resource administrator. Similarly, the Santa Marta y Ciénaga water fund received seed capital from the LAWFP, led by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and TNC. Within a year, several private actors joined the Fund’s development, among which the Prosierra foundation was later designated as the Fund’s operator. The compliance of the agreements on how the Funds would be funded by the actors also varies across cases. Cartagena and Santa Marta included as sources of funding the mandatory investment of 1% of the yearly budget of municipalities and regional government for environmental protection. However, it was not clearly defined how these resources were to be transferred, nor was there an assessment of the political will of public institutions to contribute this money. This brought to difficulties in the proper collection and management of financial resources. A recurring factor in terms of interaction between institutions mentioned in several interviews was the importance of non-formal arrangements. The results of interactions and achievements between two or more institutions are not exclusively the product of the official rules and agreements defined between them but also of informal arrangements (i.e., informal institutions). An example is the process of financing FAVS projects, where the fund provides about 60% of the resources and the CVC the remaining 40%. No agreement states how often the parties are committed to promoting these projects. However, these projects have been done and continue to be done based on the informal agreements and the existing social capital between the two organizations.

3.4. Outcomes

Three out of the five Funds were either dissolved (Cartagena and Santa Marta y Ciénaga) or in a stand-by phase (Agua Somos) during the time of this study, while two were operational (Cuenca Verde and FAVS). Agua Somos was undergoing a redesign process, which included changing the institutional arrangement, planning to shift from being operated by an existing foundation to establishing an independent organization for better functionality. On the other hand, the Cartagena and Santa Marta y Ciénaga funds did not advanced beyond the pilot phase and were in a “latency” stage until the framework agreements end. In contrast, Cuenca Verde and FAVS, were fully operational and implementing various conservation projects and initiatives in their respective impact areas (

Table 5). Opinions among respondents were diverse regarding the cost-efficiency of these mechanisms. Some individuals perceived the Water Funds as having a “light” structure that does not consume many resources in administrative costs and prioritizes the presence of personnel in the field interacting with landowners and the work of lobbying and getting partners. Conversely, other participants regarded the Funds as highly resource-intensive schemes, especially during their initial phases, since they require a diversity of professionals with specific knowledge (e.g., hydrometeorology, ecological restoration, geographic information systems). Regarding stakeholder participation and acceptance of the mechanisms, some respondents raised concerns about certain Water Funds being associated with a predominant actor, which could influence how they are perceived by other stakeholders. For example, Cuenca Verde was seen as closely linked to EPM, FAVS was perceived as primarily driven by sugar mills’ interests, and Agua Somos was identified as a program of Bogotá’s public services company. Some respondents expressed concerns that the Funds could be viewed as mere extensions of these dominant actors, leading to potential skepticism about the allocation and management of resources.

4. Discussion

Water Funds have been largely promoted in Latin America during the last 20 years as promising governance mechanisms. Still, there has been little empirical research on their impacts as institutions that reshape watershed governance. In this paper, we aimed to fill that gap by exploring the institutional factors that explain the continuity and dissolution of Water Funds in Colombia. Through the conducted institutional analysis, we identified key factors that impact the action situation of rule-making, ultimately conditioning outcomes of continuity. These encompass the institutional strength of the Funds’ constituting actors, the trust between actors based on previous relationships, and successful engagement with environmental authorities’ goals. The main contributions of this paper rely on the empirical insights for understanding the institutional conditions required for the success of collaborative governance mechanisms in watershed management and the provision of context-specific insights about how governance mechanisms operate in the Colombian socio-environmental landscape.

4.1. Stakeholder Trust Sourcing from Rules-in-Use and Actors

Our findings indicate that Water Funds structured as independent organizations (e.g., Cuenca Verde and FAVS) exhibit greater stability over time and continue to operate without having undergone significant changes in their structure. One plausible explanation for this trend is that, from an institutional standpoint, establishing the mechanism as an independent organization is preferable to delegating its functions to one of the funding partners. Such an arrangement could help avoid conflicts of interest or “judge and jury” situations when defining strategies, using resources, or managing conflicts. Moreover, the conceptual distancing of Water Funds from traditional PES schemes, as highlighted by [

25] signifies a shift towards a more complex and evolved institutional model. While Water Funds were initially inspired by the PES rationale, they developed into distinct entities with their own unique characteristics and objectives. As such, Water Funds cannot be solely viewed through the lens of a PES scheme without considering the broader political consequences they entail. Their interactions with existing institutions have significant implications, as they can reshape the traditional interplay among actors involved in watershed governance. On the other hand, according to our findings, landowners were consistently underrepresented in their interactions with the Water Funds. Except for FAVS, none of the other schemes incorporated landowners or associations of owners in decision-making mechanisms, such as the boards of directors. These findings are in line with [

28], who reported a limited representation of upstream landowners in Water Funds at the board level for Latin America, with only the instances of Tungurahua (Ecuador) and FAVS (Colombia) standing as exceptions. The lack of representation of landowners could affect the development of social capital — such as networks, shared norms, values, and understandings — that facilitates cooperation within or among actors, potentially enhancing the legitimacy of these mechanisms at the watershed level. It may also impact distribution effects and dynamics regarding how benefits from the Funds are transferred back to landowners and managers that perform management practices ensuring the provision of the targeted ecosystem services and associated co-benefits (see e.g., [

49]). According to [

33,

50], enduring common-pool resource institutions share certain design principles that underpin their success, despite their diverse contexts. One of such principles refers to collective choice arrangements, which advocates for the inclusion of actors impacted by the institution in the group responsible for modifying its rules. Embracing this principle could enhance the participation of key actors, including landowners, who directly influence watershed services through their activities and choices. Consequently, a more inclusive approach might lead to higher trusts dynamics and achievement of the schemes’ continuity.

4.2. Institutional Strength Influencing Water Funds’ Continuity

The construction of social capital is associated with intricate processes that, depending on the characteristics of the actors, often take time and has a large impact on the characteristics of different communities. Let us get back to the example of FAVS, where the WUA that receive the resources collected by the Fund to implement the projects have existed since the 1990s. This implies that they have been established in the watersheds for more than 20 years through processes of trust, reciprocity and reputation [

51]. These processes have also allowed a progressive concordance of values between different landowners and water users in the watershed, articulated by the WUAs. One of these actors was also the CVC, which is one of the fundamental partners of FAVS. In contrast, cases such as the Cartagena and Santa Marta Water Funds did not have significant processes of previous interactions between actors. The lack of funding and political will from public partners, such as water utilities, municipalities, and environmental authorities who had initially signed the launch agreements, ultimately hindered the progression of these Funds toward a continuous operational phase. In addition to the trust and previous collaborations between institutions, flexibility aspects of a mechanism plays a pivotal role in ensuring its sustainability amidst a constantly changing environment [

52,

53]. In this context, it could be argued that the Funds that have remained over time and engaged with key institutions are those that have adapted to the rules of the game rather than those that have imposed the rules. By being receptive to change, these Funds have facilitated stakeholders to reach actual agreements, charting a clear course of action and methods for implementation. This sheds light on the importance of negotiations and agreement processes in defining the interests of various actors, establishing robust rules of engagement, and formulating effective conflict resolution mechanisms. Finally, the characteristics and interactions of the different actors in the rule-making situation cannot be seen entirely independently of other action situations. For example, the constant changes in political regimes within the public actors that conformed Agua Somos and the Cartagena Water Funds might have had a large impact on the agenda of these institutions, which ultimately repercussed in the Funds’ agendas. The Water Funds governance might weaken without actors with a consistent agenda. This situation could erode trust between actors and may result in the dissolution of the Funds.

4.3. Collaboration with Environmental Authorities as a Prerequisite for Viable Water Funds

The involvement of local water utilities and private companies emerged as a common trend across all five Water Funds. These findings align with [

28], who similarly identified water utilities, private companies, multilateral organizations, and NGOs as the primary actors in Water Funds across Latin America. However, our study highlights a distinctive aspect in the Colombian context, where environmental authorities play a significant role within the Water Funds rule-making. This discrepancy may be attributed to Colombia’s decentralized system of environmental governance [

54], which comprises regional environmental authorities instead of a centralized national body. Consequently, environmental authorities hold considerable influence in watershed-level governance. The level of interaction between a Water Fund and the environmental authority in its operating area may play a pivotal role in determining the Fund’s capacity and overall continuity. The experiences of the Santa Marta y Ciénaga and Cartagena Water Funds, where environmental authorities did not fulfill their initial commitment to contribute economic resources, highlight how these mechanisms can disrupt existing power dynamics and discomfort key actors by challenging the status quo. Contrastingly, the cases of Cuenca Verde and FAVS exemplify how Water Funds can foster synergistic relationships with other institutions, leading to enhanced environmental and watershed governance outcomes. This is in line with findings from previous research stressing the importance of PES design and implementation strategies to ensure both ecological and social goas are achieved (e.g., [

13]). The varying interactions between different Water Funds and other institutional actors can be attributed, in part, to their unique origins and development processes. Cuenca Verde and FAVS were products of social processes at the local level, which facilitated the establishment of agreements and informal institutions through trust-building, [

40,

51].

5. Conclusions

In this research, we analyzed the Water Funds in Colombia within the Latin American Water Funds Partnership from an institutional perspective. By using the Ostrom’s IAD Framework, we analyzed the factors that contribute to explain continuity and dissolution, as outcomes of the rule-making process for Water Funds in Colombia.

The findings revealed how the institutional strength of the actors that compose a Water Fund governing body and partake of their constitutive process largely impact the Fund continuity. This institutional strength might be influenced by the attributes of the community, such as previous collaboration experiences that built social capital and trust between actors, and the impact of adjacent action situations such as the political regime changes, especially in public institutions such as the cities’ water utilities. Such changes might affect the Funds’ agenda and objectives, easily eroding the trust between actors, particularly the private ones.

Stakeholders trust prove to be another influential factor regarding the Fund’s continuity or dissolution. A limited representation of upstream landholders in decision-making, indicating a marginal role for beneficiaries in participation created limited legitimacy of the Funds in the implementation areas. In the same line, not all the Water Funds were backed up by the environmental authorities, which posed critical challenges to some of the Funds’ financing and viability. However, positive examples, such as FAVS and Cuenca Verde, demonstrated the importance of building trust and social capital over time. Including principles of greater involvement for stakeholders could enhance cooperation and legitimacy.

Finally, our study reveals that that Water Funds should not be seen as institutions that replace public entities with similar functions, since, at least in Colombia, there are instruments for watershed planning and public bodies to implement it. Instead, they can complement the role of environmental authorities in environmental conservation to enhance private sector and civil society engagement around watershed governance mechanisms and benefit-cost sharing.

Despite all our efforts, the present work has some limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, there is uneven information available for the different Water Funds, which may restrict the analysis and the level of detail in describing each mechanism. The low representativeness of landowners with respect to the Funds-related interviewees (e.g., director, developers, board members) might pose some bias in the results and the analysis. Secondly, the use of the institutional analysis approach in analyzing the Water Funds may lead to context-specific reasoning and notions, making it challenging to generalize results or draw broad conclusions about the subject. To address these limitations and expand the understanding of Water Funds, future research could explore comparative exercises at the regional level or in other countries. Additionally, further investigation could encompass other schemes beyond those within the LAWFP that operate as Water Funds

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D.R.; methodology, A.L.; formal analysis, J.D.R.; investigation, J.D.R.; data curation, M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D.R.; writing—review and editing, M.M.; supervision, A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank The Nature Conservancy’s Latin American Water Security team for helping us contact the five Water Funds in Colombia and the interviewees for their collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACUACAR |

Cartagena’s Water Utility |

| CAR |

Regional Autonomous Corporation of Cundinamarca |

| CARDIQUE |

Regional Autonomous Corporation of the Dique Canal |

| CORNARE |

Regional Autonomous Corporation of the Negro and Nare River Basins |

| CORPAMAG |

Magdalena Regional Autonomous Corporation |

| CVC |

Regional Autonomous Corporation of Valle del Cauca |

| EAAB |

Bogotá Aqueduct and Sewerage Company |

| EPM |

Medellín’s public service company |

| FAVS |

Water Fund for Life and Sustainability Foundation |

| FCD |

Canal del Dique Foundation |

| IAD |

Institutional Analysis and Development Framework |

| IDB |

Inter-American Development |

| LAWFP |

Latin American Water Funds Partnership |

| NbS |

Nature-based solutions |

| NGO |

Non-governmental organization |

| PES |

Payment for Ecosystem Services |

| PWS |

Payment for Watershed Services |

| TNC |

The Nature Conservancy |

| WUA |

Water Users Association |

References

- R. Chakraborty and P. Y. Sherpa, “From climate adaptation to climate justice: Critical reflections on the IPCC and Himalayan climate knowledges,” Clim Change, vol. 167, no. 3–4, pp. 1–14, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Deere-Birkbeck, “Global governance in the context of climate change: the challenges of increasingly complex risk parameters,” Int Aff, vol. 85, no. 6, pp. 1173–1194, Nov. 2009. [CrossRef]

- P. Rashidi and K. Lyons, “Democratizing global climate governance? The case of indigenous representation in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC),” https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2021.1979718, 202. [CrossRef]

- D. K. Bardsley and G. P. Rogers, “Prioritizing Engagement for Sustainable Adaptation to Climate Change: An Example from Natural Resource Management in South Australia,”. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920802287163, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 1–17, Jan. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Vogl et al., “Mainstreaming investments in watershed services to enhance water security: Barriers and opportunities,” Environ Sci Policy, vol. 75, pp. 19–27, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- E. Gómez-Baggethun and R. Muradian, “In markets we trust? Setting the boundaries of Market-Based Instruments in ecosystem services governance,” Sep. 01, 2015, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- M. Hrabanski, “Private Sector Involvement in the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment: Using a UN platform to promote market-based instruments for ecosystem services,” Environmental Policy and Governance, vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 605–618, Nov. 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Pirard and R. Lapeyre, “Classifying market-based instruments for ecosystem services: A guide to the literature jungle,” Ecosyst Serv, vol. 9, pp. 106–114, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Derissen and U. Latacz-Lohmann, “What are PES? A review of definitions and an extension,” Ecosyst Serv, vol. 6, pp. 12–15, Dec. 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. Kaiser, D. Haase, and T. Krueger, “Payments for ecosystem services: A review of definitions, the role of spatial scales, and critique,” Ecology and Society, vol. 26, no. 2, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Wunder, “Revisiting the concept of payments for environmental services,” Ecological Economics, vol. 117, pp. 234–243, Sep. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Bellver-Domingo, F. Hernández-Sancho, and M. Molinos-Senante, “A review of Payment for Ecosystem Services for the economic internalization of environmental externalities: A water perspective,” Geoforum, vol. 70, pp. 115–118, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- N. Grima, S. J. Singh, B. Smetschka, and L. Ringhofer, “Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) in Latin America: Analysing the performance of 40 case studies,” Ecosyst Serv, vol. 17, pp. 24–32, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Martin-ortega, E. Ojea, and C. Roux, “Payments for Water Ecosystem Services in Latin America : Evidence from Reported Experience,” 2012. Accessed: Feb. 18, 2021. [Online]. Available: www.bc3research.org.

- H. Wang, S. Meijerink, and E. Van Der Krabben, “Institutional Design and Performance of Markets for Watershed Ecosystem Services: A Systematic Literature Review,” Sustainability, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Kang et al., “Investing in nature-based solutions: Cost profiles of collective-action watershed investment programs,” Ecosyst Serv, vol. 59, p. 101507, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mia Smith et al., “Doubling Down on Nature - State of Investment in Nature-based Solutions for Water Security 2025,” 2025. Accessed: Sep. 16, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.forest-trends.org/publications/doubling-down-on-nature/.

- J. Salzman, G. Bennett, N. Carroll, A. Goldstein, and M. Jenkins, “The global status and trends of Payments for Ecosystem Services,” Nature Sustainability 2018 1:3, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 136–144, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. Sophie, B. Atwell, K. Dominique, N. Matthews, M. Becker, and R. Muñoz, “Funding and financing to scale nature-based solutions for water security,” Nature-Based Solutions and Water Security: An Action Agenda for the 21st Century, pp. 361–398, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Echavarria, J. Cassin, and J. Bento Da Rocha, “Protecting source waters in Latin America,” in Nature-Based Solutions and Water Security: An Action Agenda for the 21st Century, Elsevier, 2021, pp. 215–239. [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Barajas, J. Mahlknecht, J. Kaledin, M. Kjellén, and A. Mejía-Betancourt, Water and cities in Latin America: Challenges for sustainable development. Taylor and Francis Inc., 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Hommes, R. Boelens, S. Bleeker, B. Duarte-Abadía, D. Stoltenborg, and J. Vos, “Water governmentalities: The shaping of hydrosocial territories, water transfers and rural–urban subjects in Latin America,” Environ Plan E Nat Space, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 399–422, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Bremer, G. Gammie, and O. Maldonado, “Participatory Social Impact Assessment of Water Funds: A Case Study from Lima, Peru,” 2016.

- R. L. Goldman-Benner et al., “Water funds and payments for ecosystem services: practice learns from theory and theory can learn from practice,” Oryx, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 55–63, Jan. 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Nelson, L. Bremer, K. Meza Prado, and K. A. Brauman, “The Political Life of Natural Infrastructure: Water Funds and Alternative Histories of Payments for Ecosystem Services in Valle del Cauca, Colombia,” Dev Change, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 26–50, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- The Nature Conservancy, “Water funds: Field guide,” 2018.

- Brauman, R. Benner, S. Benitez, L. Bremer, and K. Vigerstøl, “Water Funds,” in Green Growth That Works, Island Press/Center for Resource Economics, 2019, pp. 118–140. [CrossRef]

- Bremer et al., “One size does not fit all: Natural infrastructure investments within the Latin American Water Funds Partnership,” Ecosyst Serv, vol. 17, pp. 217–236, 2016. [CrossRef]

- N. Kosoy, M. Martínez-Tuna, R. Muradian, and J. Martinez-Alier, “Payments for environmental services in watersheds: Insights from a comparative study of three cases in Central America,” Ecological Economics, vol. 61, no. 2–3, pp. 446–455, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Porras, B. Alyward, and J. Dengel, Monitoring payments for watershed services schemes in developing countries. 2013. Accessed: Feb. 18, 2021. [Online]. Available: http://pubs.iied.org/16525IIED.

- Muñoz Escobar, R. Hollaender, and C. Pineda Weffer, “Institutional durability of payments for watershed ecosystem services: Lessons from two case studies from Colombia and Germany,” Ecosyst Serv, vol. 6, pp. 46–53, Dec. 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. Muradian and J. C. Cardenas, “From market failures to collective action dilemmas: Reframing environmental governance challenges in Latin America and beyond,” Ecological Economics, vol. 120, pp. 358–365, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- E. Ostrom, “Background on the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework,” Policy Studies Journal, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 7–27, 2011. [CrossRef]

- F. Veiga, A. Calvache, S. Benítez, J. León, and A. Ramos, “Water funds as a tool for urban water provision and watershed conservation in Latin America,” in Water and cities in Latin America: Challenges for sustainable development, 2015, ch. 14, p. 235.

- P. H. Moreno Padilla, “Fondo Agua por la Vida y la Sostenibilidad: Manejo Integral de Cuencas hidrográficas en el Valle geográfico alto del Río Cauca,” 2016. Accessed: Mar. 25, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.asocana.org/documentos/2642016-1637CC45-00FF00,000A000,878787,C3C3C3,0F0F0F,B4B4B4,FF00FF,FFFFFF,2D2D2D,A3C4B5,D2D2D2.pdf.

- Santos de Lima, “Effectiveness and Uncertainties of Payments for Watershed Services,” 2017.

- Z. Nigussie et al., “Applying Ostrom’s institutional analysis and development framework to soil and water conservation activities in north-western Ethiopia,” Land use policy, vol. 71, pp. 1–10, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. Corbera, C. G. Soberanis, and K. Brown, “Institutional dimensions of Payments for Ecosystem Services: An analysis of Mexico’s carbon forestry programme,” Ecological Economics, vol. 68, no. 3, pp. 743–761, Jan. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, “Characterizing governance and benefits of payments for watershed services in Europe,” 2015.

- Prokofieva and E. Gorriz, “Institutional analysis of incentives for the provision of forest goods and services: An assessment of incentive schemes in catalonia (north-east spain),” For Policy Econ, vol. 37, pp. 104–114, Dec. 2013. [CrossRef]

- D. McGinnis, “Networks of Adjacent Action Situations in Polycentric Governance,” Policy Studies Journal, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 51–78, Feb. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Kimmich, E. Baldwin, E. Kellner, C. Oberlack, and S. Villamayor-Tomas, “Networks of action situations: a systematic review of empirical research,” Sustain Sci, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 11–26, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. Miller and B. Crabtree, “Clinical research,” in Handbook of qualitative research, 3rd edition., N. Denzin and Y. Lincoln, Eds., Thousand Oaks, California: Sage, 2005, pp. 605–639.

- V. Braun and V. Clarke, “Using thematic analysis in psychology,” Qual Res Psychol, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 77–101, 2006. [CrossRef]

- King, “Using Templates in the Thematic Analysis of Text,” Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research, pp. 256–270, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. S. Nowell, J. M. Norris, D. E. White, and N. J. Moules, “Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria,” Int J Qual Methods, vol. 16, no. 1, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lincoln and E. G. Guba, Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1985.

- DiCicco-Bloom and B. F. Crabtree, “The qualitative research interview,” Med Educ, vol. 40, no. 4, pp. 314–321, Apr. 2006. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Zanella, C. Schleyer, and S. Speelman, “Why do farmers join Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) schemes? An Assessment of PES water scheme participation in Brazil,” Ecological Economics, vol. 105, pp. 166–176, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- E. Ostrom, Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action, Cambridge. 1990.

- E. Ostrom, “A Behavioral Approach to the Rational Choice Theory of Collective Action: Presidential Address, American Political Science Association, 1997,” American Political Science Review, vol. 92, no. 1, pp. 1–22, Mar. 1998. [CrossRef]

- T. Baerlein, U. Kasymov, and D. Zikos, “Self-Governance and Sustainable Common Pool Resource Management in Kyrgyzstan,” Sustainability 2015, Vol. 7, Pages 496-521, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 496–521, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. Nunan, Governing Renewable Natural Resources: Theories and Frameworks - 1st E. 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.routledge.com/Governing-Renewable-Natural-Resources-Theories-and-Frameworks/Nunan/p/book/9780367146702.

- R. R. Hohbein, N. Nibbelink, and R. J. Cooper, “Impacts of Decentralized Environmental Governance on Andean Bear Conservation in Colombia,” Environ Manage, vol. 68, no. 6, pp. 882–899, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).