Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

02 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Filtering

2.2. Qualitative and Quantitative Classification

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

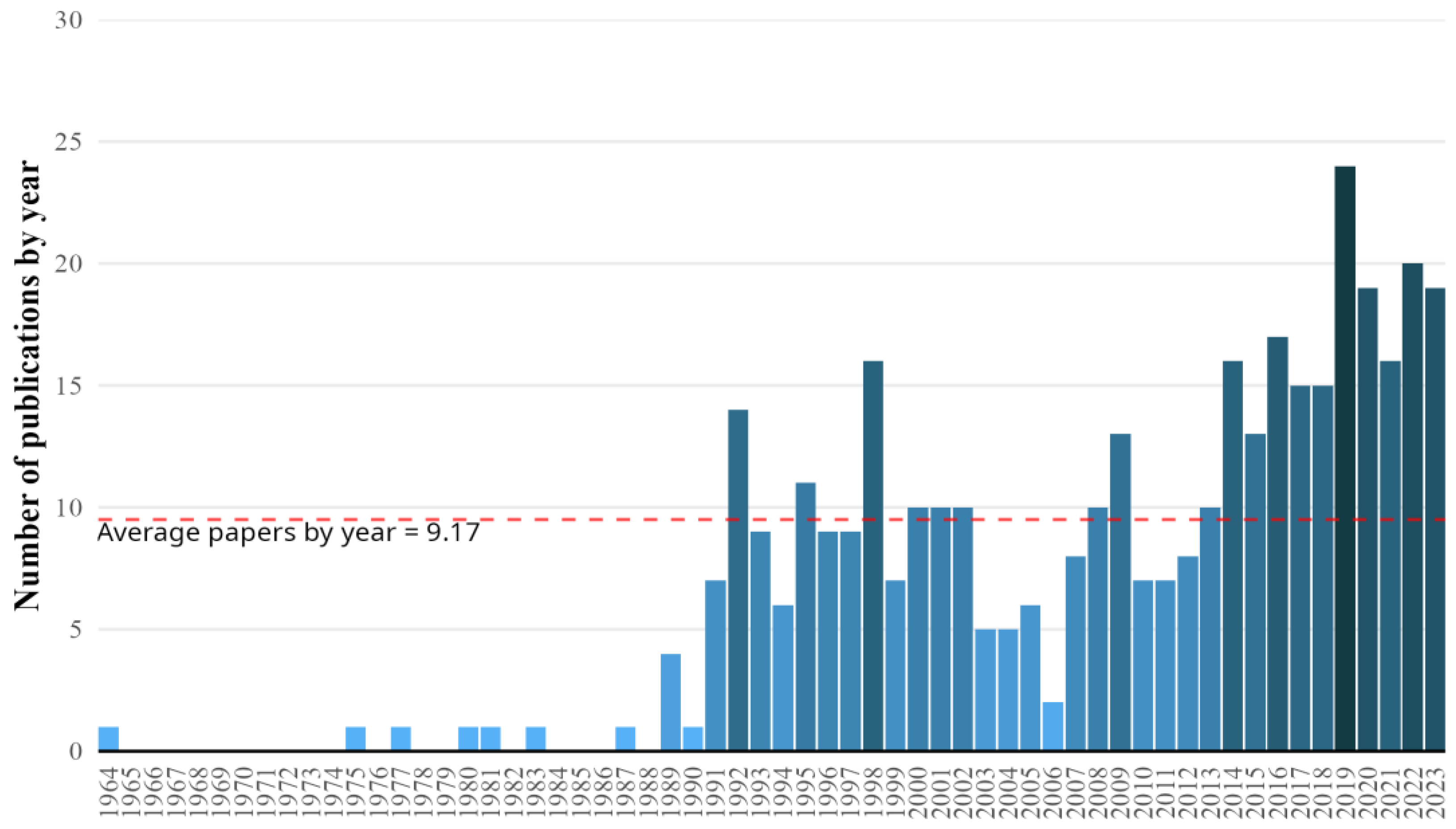

3.1. Temporal Trends

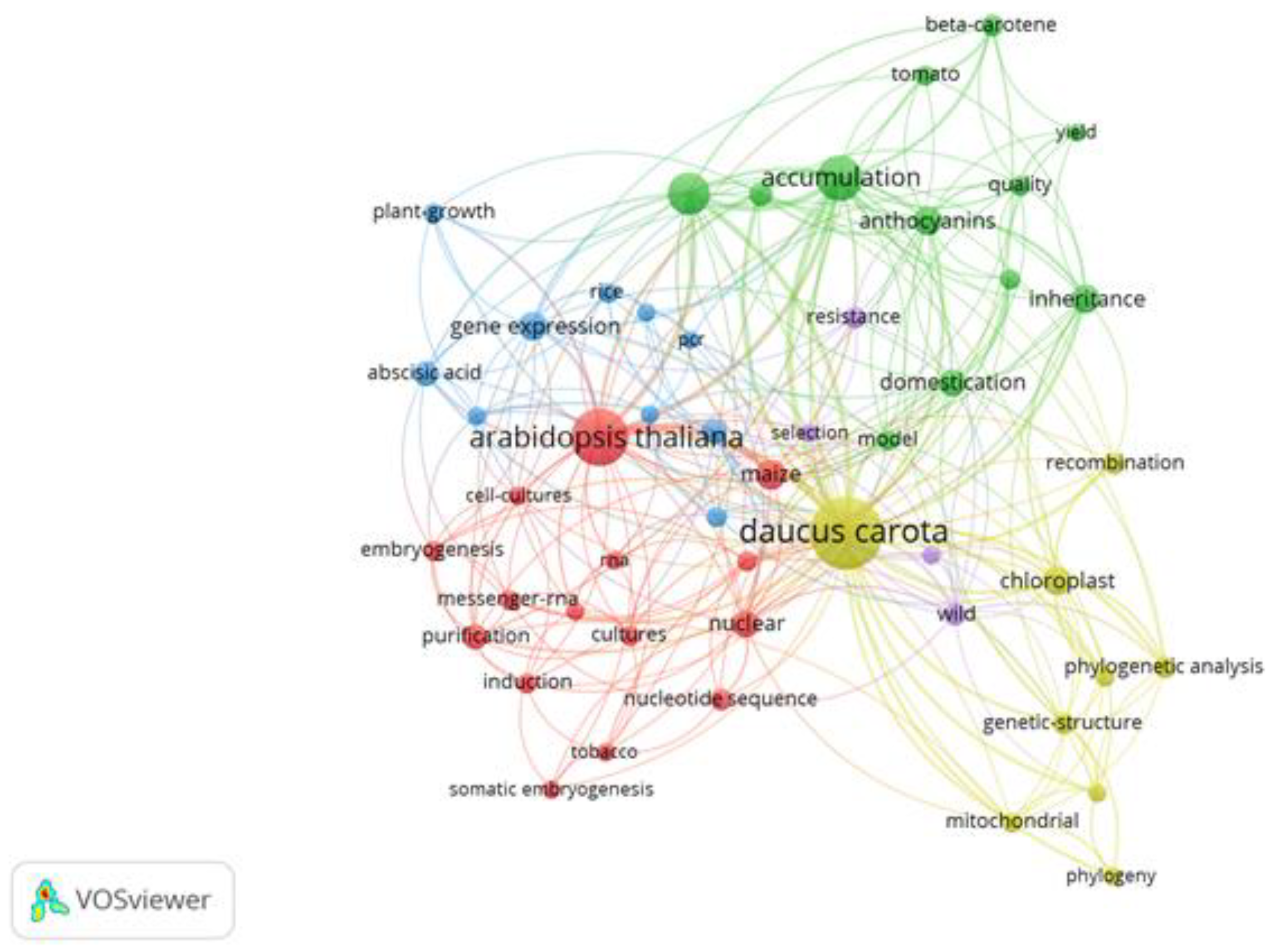

3.2. Keyword Co-Occurrence

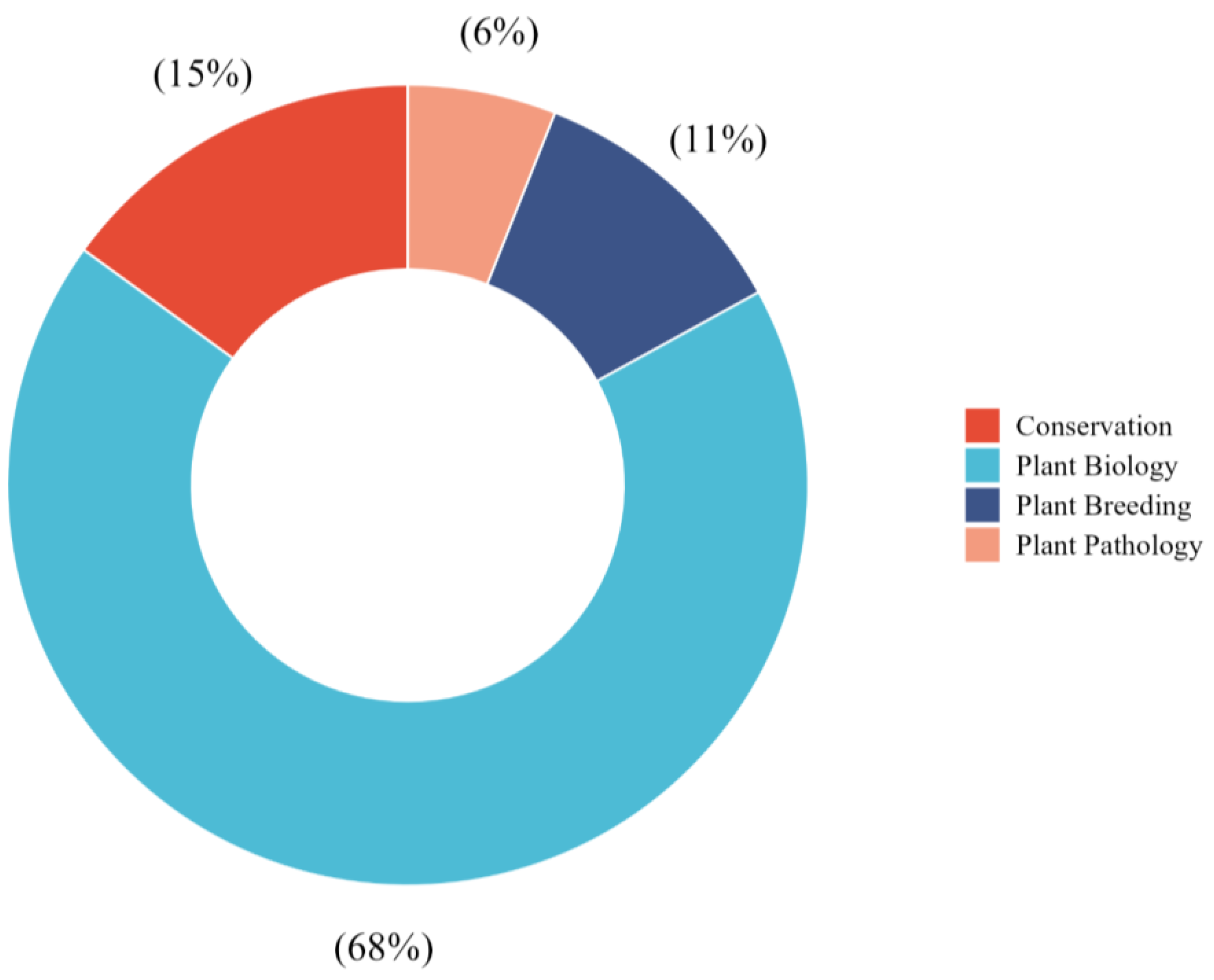

3.3. Thematic Distribution

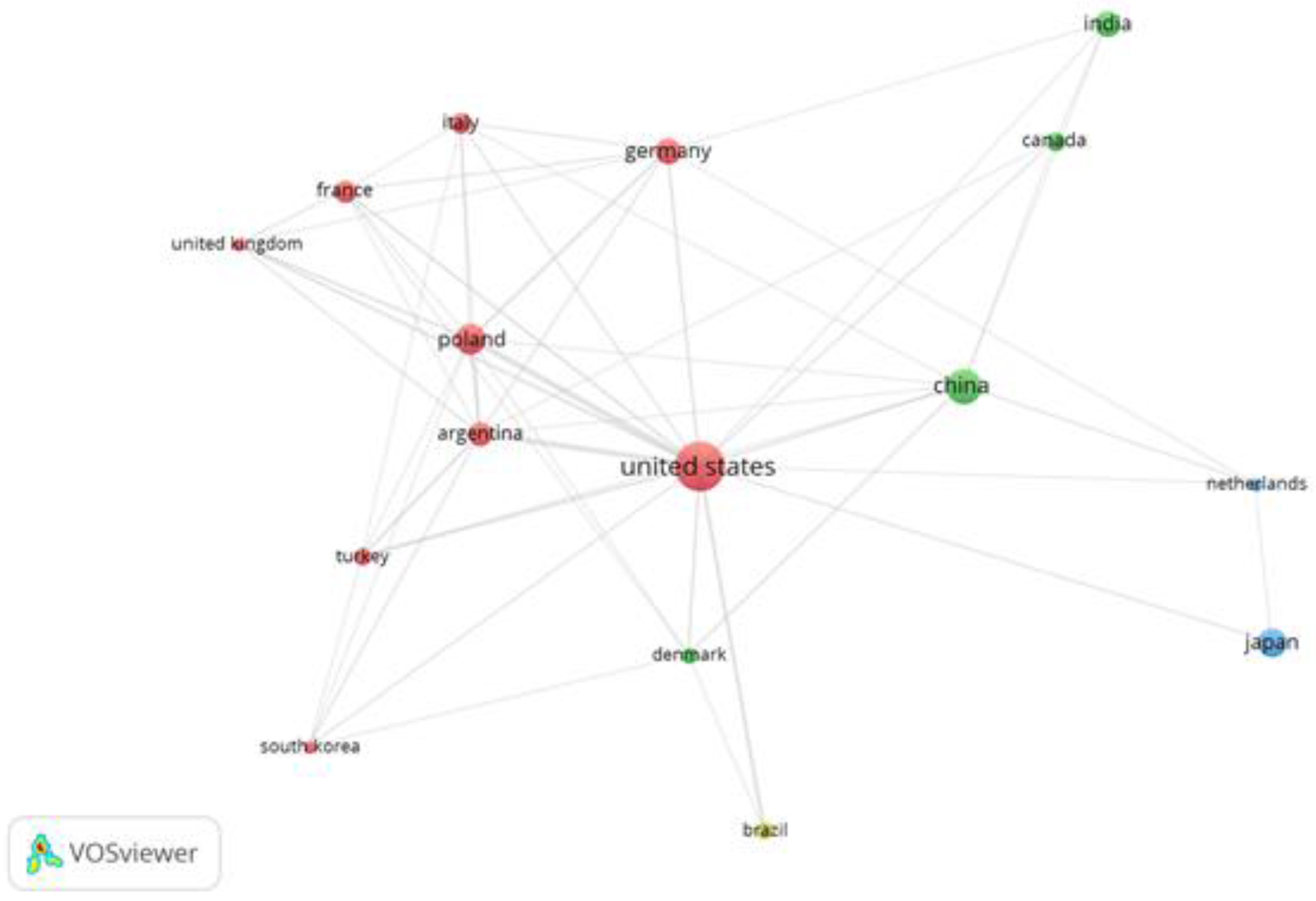

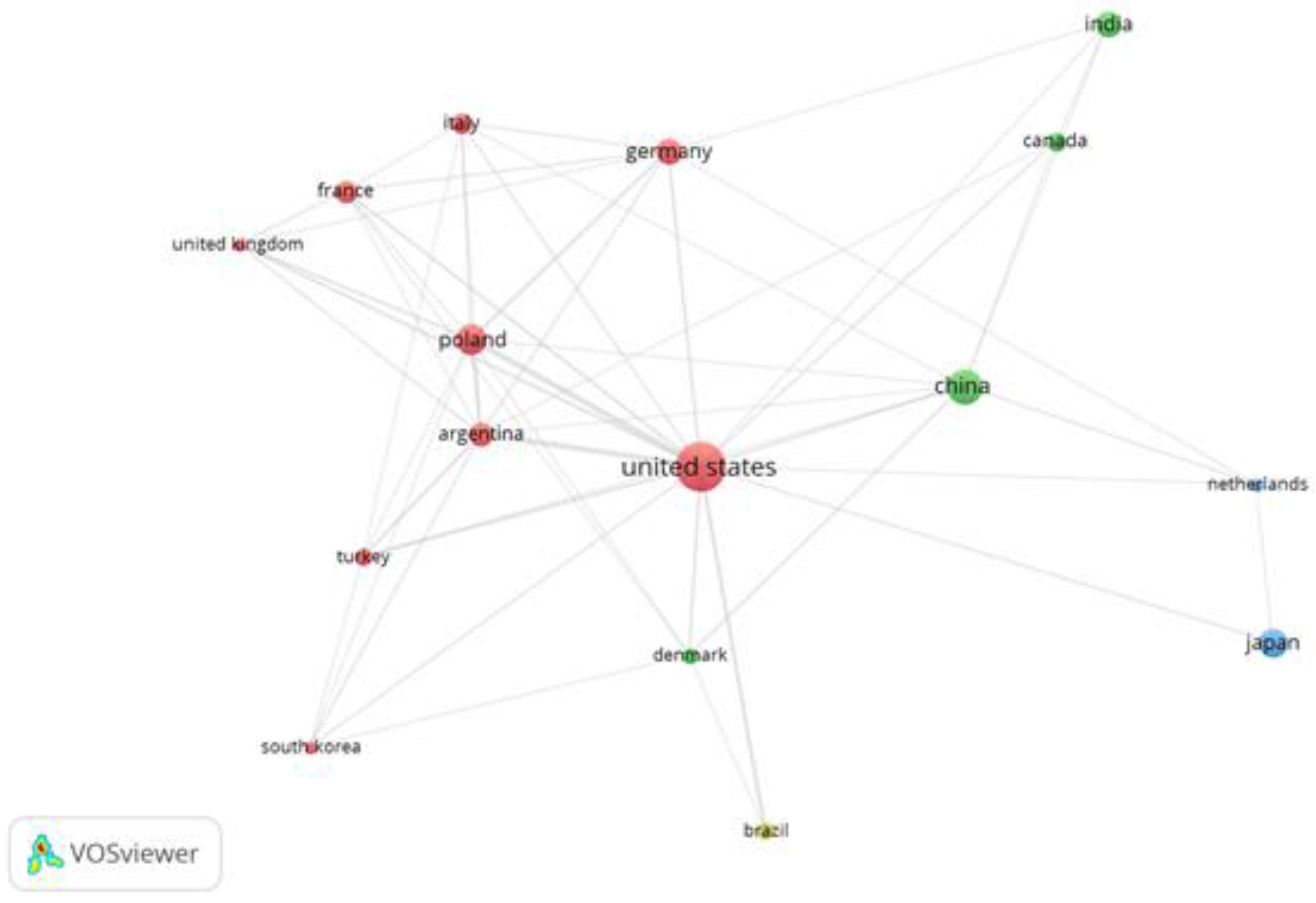

3.4. Organizational, Co-Authorship Network and Journals

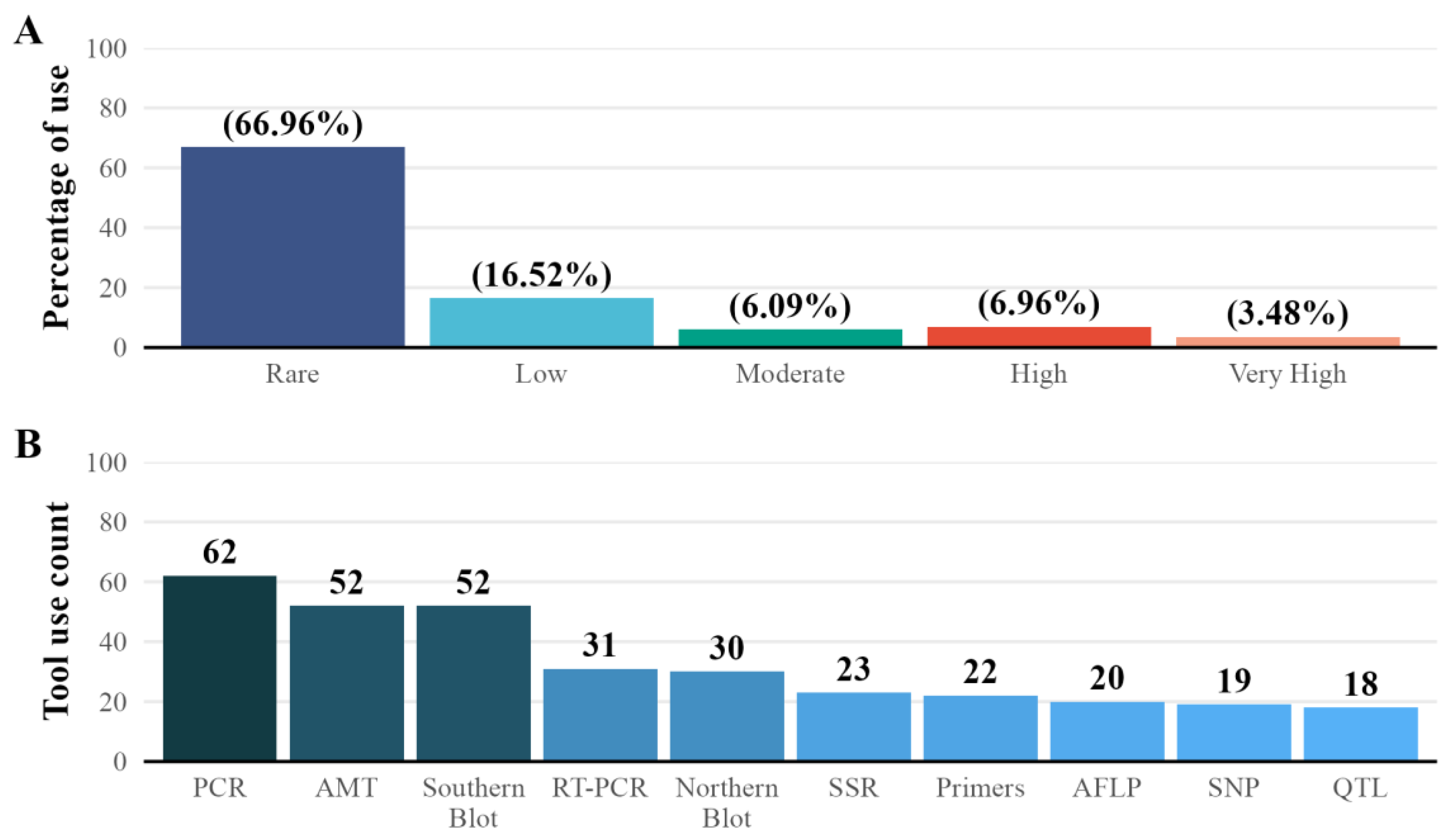

3.5. Frequency of Use Of Tools

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Credit authorship contribution statement

Declaration of competing interest

Funding

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Arscott, S.A.; Tanumihardjo, S.A. Carrots of many colors provide basic nutrition and bioavailable phytochemicals acting as a functional food. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2010, 9, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paparella, A.; Kongala, P.R.; Serio, A.; Rossi, C.; Shaltiel-Harpaza, L.; Husaini, A.M.; Ibdah, M. Challenges and Opportunities in the Sustainable Improvement of Carrot Production. Plants 2024, 13, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAOSTAT Database. 2025. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL.

- Kalia, P.; Singh, B.; Shivashankar, B.; Patel, V.; Selvakumar, R. Carrot: Breeding and genomics. Veg. Sci. 2023, 50, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorizzo, M.; Ellison, S.; Senalik, D.; Zeng, P.; Satapoomin, P.; Huang, J.; Bowman, M.; Lovene, M.; Sanseverino, W.; Cavagnaro, P.; Yildiz, M.; Macko-Podgórni, A.; Moranska, E.; Grzebelus, E.; Grzebelus, D.; Asrafi, H.; Zheng, M.Z.; Cheng, S.; Colher, D.; Van Deynze, A.; Simão, F. A high-quality carrot genome assembly provides new insights into carotenoid accumulation and asterid genome evolution. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.D.; Maurizio, P.L.; Valdar, W.; Yandell, B.S.; Simon, P.W. Dissecting the genetic architecture of shoot growth in carrot (Daucus carota L.) using a diallel mating design. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2020, 133, 473–488. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.-H.; Liu, P.-Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, R.-R.; Liang, Y.; Xu, Z.-S.; Li, X.-J.; Luo, Q.; Tan, G.-F.; Wang, G.-L.; Xiong, A.-S. Telomere-to-telomere carrot (Daucus carota) genome assembly reveals carotenoid characteristics. Horticulturae Research 2023, 10, uhad103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brainard, S.H.; Ellison, S.L.; Simon, P.W.; Dawson, J.C.; Goldman, I.L. Genetic characterization of carrot root shape and size using genome-wide association analysis and genomic-estimated breeding values. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 605–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolling, W.R.; Ellison, S.; Coe, K.; Iorizzo, M.; Dawson, J.; Senalik, D.; Simon, P.W. Combining genome-wide association and genomic prediction to unravel the genetic architecture of carotenoid accumulation in carrot. Plant Genome 2025, 18, e20560. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Swarup, S.; Cargill, E.J.; Crosby, K.; Flagel, L.; Kniskern, J.; Glenn, K.C. Genetic diversity is indispensable for plant breeding to improve crops. Crop Sci. 2021, 61, 839–852. [Google Scholar]

- Salgotra, R.K.; Chauhan, B.S. Genetic diversity, conservation, and utilization of plant genetic resources. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Concepcion, M.; Stange, C. Biosynthesis of carotenoids in carrot: An underground story comes to light. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2013, 539, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavagnaro, P.F.; Iorizzo, M. Carrot anthocyanins: diversity, genetics and genomics. In: Simon, P.W.; Iorizzo, M.; Grzebelus, D.; Baranski, R. (Eds.). The Carrot Genome. Compendium of Plant Genomes, Vol. 60. Springer, Cham. 2019, pp. 261–277.

- Cavagnaro, P.F. Genetics and genomics of carrot sugars and polyacetylenes. In: Simon, P.W.; Iorizzo, M.; Grzebelus, D.; Baranski, R. (Eds.). The Carrot Genome. Compendium of Plant Genomes, Vol. 60. Springer, Cham. 2019, pp. 295–315.

- Cavagnaro, P.F.; Dunemann, F.; Selvakumar, R.; Iorizzo, M.; Simon, P.W. Genetics, genomics, and molecular breeding for health-enhancing compounds in carrot. In: Kole, C. (Ed.). Compendium of Crop Genome Designing for Nutraceuticals. Springer Nature, Switzerland. 2023, pp. 1365–1435.

- Que, F.; Hou, X.L.; Wang, G.L.; Xu, Z. -S.; Tan, G.F.; Li, T.; Wang, Y.H.; Khadr, A.; Xiong, A.S. Advances in research on the carrot, an important root vegetable in the Apiaceae family. Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Junaid, M.D.; Öztürk, Z.N.; Gökçe, A.F. Exploitation of tolerance to drought stress in carrot (Daucus carota L.): An overview. Stress Biol. 2023, 3, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cholin, S.S.; Kulkarni, C.C.; Grzebelus, D.; Jakaraddi, R.; Hundekar, A.; Chandan, B.M.; Archana, T.S.; Krishnaja, N.R.; Prabhuling, G.; Ondrasek, G.; Cão, A.; Jakaraddi, R.; Simão, F. Deciphering carotenoid and flowering pathway gene variations in eastern and western carrots (Daucus carota L.). Genes 2024, 15, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Y.; Xu, Z.S.; Huang, Y.; Tian, C.; Wang, F.; Xiong, A.S. Genome-wide analysis of AP2/ERF transcription factors in carrot (Daucus carota L.) reveals evolution and expression profiles under abiotic stress. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2015, 290, 2049–2061. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, J.N.; Wang, Y.H.; Duan, A.Q.; Liu, J.X.; Feng, K.; Xiong, A.S. NAC family transcription factors in carrot: Genomic and transcriptomic analysis and responses to abiotic stresses. DNA Cell Biol. 2020, 39, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Que, F.; Wang, G.L.; Huang, Y.; Xu, Z.S.; Wang, F.; Xiong, A.S. Genomic identification of group A bZIP transcription factors and their responses to abiotic stress in carrot. Genet. Mol. Res. 2015, 14, 13274–13288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, A.Q.; Tan, S.S.; Deng, Y.J.; Xu, Z.S.; Xiong, A.S. Genome-wide identification and evolution analysis of R2R3-MYB gene family reveals S6 subfamily R2R3-MYB transcription factors involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis in carrot. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Zhao, D.; Ou, C.; Zhao, Z.; Zhuang, F.; Liu, X. Transcriptome analysis reveals the molecular mechanisms of carrot adaptation to Alternaria leaf. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranski, R.; Maksylewicz-Kaul, A.; Nothnagel, T.; Cavagnaro, P.F.; Simon, P.W.; Grzebelus, D. Genetic diversity of carrot (Daucus carota L.) cultivars revealed by analysis of SSR loci. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2012, 59, 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Coe, K.; Bostan, H.; Rolling, W.; Turner-Hissong, S.; Macko-Podgórni, A.; Senalik, D.; Liu, S.; Seth, R.; Curuba, J.; Mengist, F.M.; Grzebelus, D.; Van Deynze, A.; Dawson, J.; Ellison, S.; Simon, P. Population genomics identifies genetic signatures of carrot domestication and improvement and uncovers the origin of high-carotenoid orange carrots. Nat. Plants 2023, 9, 1643–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allender, C. Genetic resources for carrot improvement. In: Simon, P.; Iorizzo, M.; Grzebelus, D.; Baranski, R. (Eds.). The Carrot Genome. Compendium of Plant Genomes. Springer, Cham. 2019, pp. 119–136.

- Birkle, C.; Pendlebury, D.A.; Schnell, J.; Adams, J. Web of Science as a data source for research on scientific and scholarly activity. Quant. Sci. Stud. 2020, 1, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2024. https://www.r-project.org/.

- Wickham, H. Tidyverse: Easily install and load the 'Tidyverse'. R package version 1.3.0. 2019.

- Kumar, S.; Dhingra, A.; Daniell, H. Plastid-expressed betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase gene in carrot cultured cells, roots, and leaves confers enhanced salt tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2004, 136, 2843–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iorizzo, M.; Senalik, D.A.; Grzebelus, D.; Bowman, M.; Cavagnaro, P.F.; Matvienko, M.; Ashrafi, H.; Van Deynze, A.; Simon, P.W. De novo assembly and characterization of the carrot transcriptome reveals novel genes, new markers, and genetic diversity. BMC Genomics 2011, 12, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorizzo, M.; Senalik, D.A.; Ellison, S.L.; Grzebelus, D.; Cavagnaro, P.F.; Allender, C.; Brunet, J.; Spooner, D.M.; Van Deynze, A.; Simon, P.W. Genetic structure and domestication of carrot (Daucus carota subsp. sativus) (Apiaceae). Am. J. Bot. 2013, 100, 930–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clotault, J.; Peltier, D.; Berruyer, R.; Thomas, M.; Briard, M.; Geoffriau, E. Expression of carotenoid biosynthesis genes during carrot root development. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 3563–3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Feng, B.; Xiao, J.; Xia, Z.; Zhou, X.; Li, P.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Møller, B.L.; Zhang, P.; Luo, M.C.; Xiao, G.; Liu, J.; Yang, J.; Chen, S.; Rabinowicz, P.D.; Chen, X.; Zhang, H.B.; Ceballos, H.; Lou, Q.; Zou, M.; Carvalho, L.J.C.B.; Zeng, C.; Xia, J.; Sun, S.; Fu, Y.; Wang, H.; Lu, C.; Ruan, M.; Zhou, S.; Wu, Z.; Liu, H.; Kannangara, R.M.; Jørgensen, K.; Neale, R.L.; Bonde, M.; Heinz, N.; Zhu, W.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, K.; Wen, M.; Ma, P.A.; Li, Z.; Hu, M.; Liao, W.; Hu, W.; Zhang, S.; Pei, J.; Guo, A.; Guo, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Ye, J.; Ou, W.; Ma, Y.; Liu, X.; Tallon, L.J.; Galens, K.; Ott, S.; Huang, J.; Xue, J.; An, F.; Yao, Q.; Lu, X.; Fregene, M.; López-Lavalle, L.A.B.; Wu, J.; You, F.M.; Chen, M.; Hu, S.; Wu, G.; Zhong, S.; Ling, P.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, G.; Liu, B.; Li, K.; Peng, M. Cassava genome from a wild ancestor to cultivated varieties. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.C.; Brito, G.R.d.; Nascimento, W.F.d.; Vieira, E.A.; Navaes, F.M.; Siqueira, M.V.B.M. Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz): Evolution and Perspectives in Genetic Studies. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just, B.J.; Santos, C.A.; Yandell, B.S.; Simon, P.W. Major QTL for carrot color are positionally associated with carotenoid biosynthetic genes and interact epistatically in a domesticated × wild carrot cross. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2009, 119, 1155–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, S.; Senalik, D.; Bostan, H.; Iorizzo, M.; Simon, P. Fine mapping, transcriptome analysis, and marker development for Y2, the gene that conditions beta-carotene accumulation in carrot (Daucus carota L.). G3 (Bethesda) 2017, 7, 2665–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, S.L.; Luby, C.H.; Corak, K.E.; Coe, K.M.; Senalik, D.; Iorizzo, M.; Goldman, I.L.; Simon, P.W.; Dawson, J.C. Carotenoid presence is associated with the Or gene in domesticated carrot. Genetics 2018, 210, 1497–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, M.; Willis, D.K.; Cavagnaro, P.F.; Iorizzo, M.; Abak, K.; Simon, P.W. Expression and mapping of anthocyanin biosynthesis genes in carrot. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2013, 126, 1689–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavagnaro, P.F.; Iorizzo, M.; Yildiz, M.; Senalik, D.; Parsons, J.; Ellison, S.; Simon, P.W. A gene-derived SNP-based high resolution linkage map of carrot including the location of QTL conditioning root and leaf anthocyanin pigmentation. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorizzo, M.; Cavagnaro, P.F.; Bostan, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yildiz, M.; Simon, P.W. A cluster of MYB transcription factors regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis in carrot (Daucus carota L.) root and leaf. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 9, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannoud, F.; Ellison, S.; Paolinelli, M.; Horejsi, T.; Senalik, D.; Fanzone, M.; Iorizzo, M.; Simon, P.W.; Cavagnaro, P.F. Dissecting the genetic control of root and leaf tissue-specific anthocyanin pigmentation in carrot (Daucus carota L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2019, 132, 2485–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannoud, F.; Carvajal, S.; Ellison, S.; Senalik, D.; Talquenca, S.G.; Iorizzo, M.; Simon, P.W.; Cavagnaro, P.F. Genetic and transcription profile analysis of tissue-specific anthocyanin pigmentation in carrot root phloem. Genes 2021, 12, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.S.; Yang, Q.Q.; Feng, K.; Xiong, A.S. Changing carrot color: Insertions in DcMYB7 alter the regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis and modification. Plant Physiol. 2019, 181, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.S.; Yang, Q.Q.; Feng, K.; Yu, X.; Xiong, A.S. DcMYB113, a root-specific R2R3-MYB, conditions anthocyanin biosynthesis and modification in carrot. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 1585–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curaba, J.; Bostan, H.; Cavagnaro, P.F.; Senalik, D.; Mengist, M.F.; Zhao, Y.; Simon, P.W.; Iorizzo, M. Identification of an SCPL gene controlling anthocyanin acylation in carrot (Daucus carota L.) root. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 10, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renna, M.; Serio, F.; Signore, A.; Santamaria, P. The yellow–purple Polignano carrot (Daucus carota L.): a multicoloured landrace from the Puglia region (Southern Italy) at risk of genetic erosion. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2014, 61, 1611–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbizu, C.; Ruess, H.; Senalik, D.; Simon, P.W.; Spooner, D.M. Phylogenomics of the carrot genus (Daucus, Apiaceae). Am. J. Bot. 2014, 101, 1666–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbizu, C.; Simon, P.; Martínez-Flores, F.; Ruess, H.; Crespo, M.; Spooner, D. Integrated molecular and morphological studies of the Daucus guttatus complex (Apiaceae). Syst. Bot. 41, 479–492. [CrossRef]

- Arbizu, C.I.; Ellison, S.L.; Senalik, D.; Simon, P.W.; Spooner, D.M. Genotyping-by-sequencing provides the discriminating power to investigate the subspecies of Daucus carota (Apiaceae). BMC Evol. Biol. 16, 234. [CrossRef]

- Arbizu, C.I.; Tas, P.M.; Simon, P.W.; Spooner, D.M. Phylogenetic prediction of Alternaria leaf blight resistance in wild and cultivated species of carrots (Daucus, Apiaceae). Crop Sci. 2017, 57, 2645–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macko-Podgórni, A.; Machaj, G.; Stelmach, K.; Senalik, D.; Grzebelus, E.; Iorizzo, M.; Simon, P.W.; Grzebelus, D. Characterization of a genomic region under selection in cultivated carrot (Daucus carota subsp. sativus) reveals a candidate domestication gene. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelmach, K.; Macko-Podgórni, A.; Allender, C.; Grzebelus, D. Genetic diversity structure of western-type carrots. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manisha; Padmini, K.; Veere Gowda, R.; Dhananjaya, M.V. Genetic diversity study in tropical carrot (Daucus carota L.). J. Hortic. Sci. 2022, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spooner, D.M.; Ruess, H.; Simon, P.; Senalik, D. Mitochondrial DNA sequence phylogeny of Daucus. Syst. Bot. 2020, 45, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, J.; Lammers, Y.; Strasburg, J.L.; Schidlo, N.S.; Ariyurek, Y.; de Jong, T.M.; Klinkhamer, P.G.L.; Smulders, M.; Vrieling, K. New insights into domestication of carrot from root transcriptome analyses. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Ahmed, N.; Ranjan, J.K.; Srivatava, K.; Kumar, D.; Yousuf, S. Assessment of genetic variability, character association, heritability and path analysis in European carrot (Daucus carota var. sativa). Indian J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 89, 1140–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlfeiler, J.; Alessandro, M.S.; Cavagnaro, P.F.; Garmarini, C.R. Multiallelic digenic control of vernalization requirement in carrot (Daucus carota L.). Euphytica 2019, 215, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nothnagel, T. Results in the development of alloplasmic carrots (Daucus carota sativus Hoffm). Plant Breed. 2006, 109, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiteux, L.; Belter, J.; Roberts, P.; Simon, P.W. RAPD linkage map of the genomic region encompassing the root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne javanica) resistance locus in carrot. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2000, 100, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boedo, C.; Berruyer, R.; Lecomte, M.; Bersihand, S.; Briard, M.; Le Clerc, V.; Simoneau, P.; Poupard, P. Evaluation of different methods for the characterization of carrot resistance to the alternaria leaf blight pathogen (Alternaria dauci) revealed two qualitatively different resistances. Plant Pathol. 2010, 59, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönegger, D.; Marais, A.; Babalola, B.M.; Faure, C.; Lefebvre, M.; Svanella-Dumas, L.; Brázdová, S.; Candresse, T. Carrot populations in France and Spain host a complex virome rich in previously uncharacterized viruses. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shushan, A.; Luria, N.; Lachman, O.; Sela, N.; Laskar, O.; Belausov, E.; Smith, E.; Dombrovsky, A. Characterization of a novel psyllid-transmitted waikavirus in carrots. Virus Res. 2023, 335, 199192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, B.; Westphal, L.; Wricke, G. Linkage groups of isozymes, RFLP and RAPD markers in carrot (Daucus carota L. sativus). Euphytica 1994, 74, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahyaa, M.; Ibdah, M.; Marzouk, S.; Ibdah, M. Profiling of the terpene metabolome in carrot fruits of wild (Daucus carota L. ssp. carota) accessions and characterization of a geraniol synthase. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 2378–2386. [Google Scholar]

- Caretto, S.; Giardina, M.C.; Nicolodi, C.; Mariotti, D. Chlorsulfuron resistance in Daucus carota cell lines and plants: involvement of gene amplification. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1994, 88, 520–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisaka, H.; Kameya, T. Production of somatic hybrids between Daucus carota L. and Nicotiana tabacum. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1994, 88, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| First author | DOI | Journal | Citations* | Main contribution | Year |

| Iorizzo, Massimo [5] | 10.1038/ng.3565 | Nature Genetics | 381 | High-quality genome assembly and insights into carotenoid accumulation, as well as asterid evolution | 2016 |

| Kumar, S [30] |

10.1104/pp.104.045187 | Plant Physiology | 340 | Overexpression of a betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase improved salt tolerance | 2004 |

| Iorizzo, Massimo [31] |

10.1186/1471-2164-12-389 | BMC Genomics | 179 | A transcriptome assembly of carrot | 2011 |

| Iorizzo, Massimo [32] |

10.3732/ajb.1300055 | American Journal of Botany | 164 | Genetic structure and domestication of carrot | 2013 |

| Clotault, Jeremy [33] |

10.1093/jxb/ern210 | Journal of Experimental Botany | 163 | Transcriptional regulation of carotenoid biosynthesis in carrot root development | 2008 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).